Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly-2001-Plog-13-24

Diunggah oleh

Dennis Sabillah RamadhanHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly-2001-Plog-13-24

Diunggah oleh

Dennis Sabillah RamadhanHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

TRAVELERS PSYCHOGRAPHICS

CORNELL QUARTERLY CLASSIC

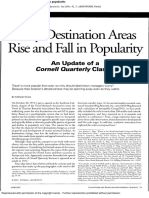

Why Destination Areas

Rise and Fall in Popularity

An Update of a

Cornell Quarterly Classic

Travel is more popular than ever, so why should destination managers worry?

Because their locations attractiveness may be spinning away even as they watch.

BY STANLEY PLOG

On October 10, 1972, I gave a speech to the Southern California chapter of the Travel Research Association (now the

Travel & Tourism Research Association) that examined the

underlying causes for why destinations rise and fall in popularity. Based on a psychographic system that we had developed at my first market-research company (BASICO), the speech

pointed out that destinations appeal to specific types of people

and typically follow a relatively predictable pattern of growth

and decline in popularity over time. The reasons lie in the

fact that the character of most destinations changes as a result

of growth and development of tourist-oriented facilities. As

destinations change, they lose the audience or market segments that made them popular and appeal instead to an evershrinking group of travelers.

Although I had used the concept in our work with travel

clients, this was the first public presentation of the ideas to a

broad audience. Considering the limited nature of the venue,

the response was surprising. Requests for copies of the speech

came from around the United States and from countries in

Europe and Asia. Apparently someone forwarded the speech

to the editors of Cornell Quarterly, because it appeared as an

article in 1974.1

Since that time I have further refined the concept and the

questions that make up the psychographic scale used to dif1

Stanley C. Plog, Why Destination Areas Rise and Fall in Popularity, Cornell

Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, Vol. 14, No. 4 (February 1974),

pp. 5558.

2001, CORNELL UNIVERSITY.

JUNE 2001

ferentiate traveler types. In the second market-research company I founded (Plog Research, Inc., now NFO/Plog Research

and a subsidiary of Interpublic Group/IPG), we have probably included the scale in more than 200 studies and consulting assignments, and have reported on it in journals and

speeches at conferences.2 Thus, a large experience base supports those early observations about destination development

and life-cycle stages. In addition, academic researchers have

explored the scales conceptual base.3

2

See: Stanley C. Plog, Where in the World Are People Going and Why Do

They Want to Go There?, a paper presented to Tiangus Touristico annual conference, Acapulco, Mexico, 1979; Stanley C. Plog, Understanding

Psychographics in Tourism Research, in Travel, Tourism, and Hospitality Research, ed. J.R.B. Ritchie and C.R. Goeldner (New York: John Wiley & Sons,

1987), pp. 203213; Stanley C. Plog, A Carpenters Tools: An Answer to

Stephen L.J. Smiths Review of Psychocentrism/Allocentrism, Journal of Travel

Research, Spring 1990, pp. 43-46; Stanley C. Plog, A Carpenters Tools Revisited: Measuring Allocentrism and Psychocentrism Properly the First Time,

Journal of Travel Research, Spring 1990, p. 50; Stanley C. Plog, Leisure Travel:

Making It a Growth MarketAgain! (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1991);

Stanley C. Plog, Leisure Travel: An Extraordinary Industry Facing Superordinary

Problems, in Global Tourism: The Next Decade, ed. W. Theobold (Oxford,

England: Butterworth-Heineman Ltd., 1994), pp. 4054; and Stanley C. Plog,

Vacation Places Rated (Redondo Beach, CA: Fielding Worldwide, Inc., 1995).

For example, see: D.A. Griffith and P. J. Albanese, An Examination of Plogs

Psychographic Travel Model Within a Student Population, Journal of Travel

Research, Spring 1996, pp. 4751; N.P. Nickerson and G.D. Ellis, Traveler

Types and Activation Theory: A Comparison of Two Models, Journal of Travel

Research, Winter 1991, pp. 2631; and P. Tarlow and M.J. Muehsam, New

Views of the International Visitor: Turning the Theory of the Plog Model Into

Application: Some Initial Thoughts on Attracting the International Tourist, a

paper presented to the Travel & Tourism Research Association, International

Conference, Minneapolis, MN, Spring 1992.

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at University of Indonesia on March 10, 2016

Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 13

CORNELL QUARTERLY CLASSIC

TRAVELERS PSYCHOGRAPHICS

Feature articles on the travel habits of the different travel personalities have appeared in popular magazines (e.g., Cond Nast Traveler, Endless

Vacation, Car & Travel, AAA World, Mature Outlook). Various college tourism texts review the

concept, and I have explained it further in two

travel books I wrote.4

How destinations grow and decline has been

part of the advanced training program offered

for travel agents for more than 20 years by the

Institute of Certified Travel Agents (ICTA), and

all trainees must answer questions about

psychographics and the tourism life cycle before

receiving their Certified Travel Counselor certificate. Other training materials for travel agents

using the basic ideas include those of SemerPurzycki and Starr.5 On-line exposure has occurred with training sites established by Harcourt

Learning Direct and Education Systems LLC

for instance, the Weissmann Travel Corner and

Puerto Ricos tourism web site for a time allowed

consumers to take a shortened version of the test

and read their own profiles.

This article reintroduces the psychographic

scale and updates what has been learned since

my last article appeared in Cornell Quarterly, including how travel has changed and where many

destinations currently fit on the destination-lifecycle chart. To review how destinations rise and

fall in popularity, it is necessary first to provide a

description of the research basis for development

of the concept and the relationship between travel

personalities and destination selection.

Psychographic Study

A group of 16 travel-industry clients supported

the original study, which was initiated in 1967.6

Sponsors included 10 major airlines, the three

commercial airframe manufacturers of the day

(Boeing, Douglass, and Lockheed), and three

large print-media companies (Readers Digest,

Time/Life, and R.H. Donnelly). The genesis of

4

As cited earlier: Stanley C. Plog, Leisure Travel: Making It A

Growth MarketAgain! (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1991);

and Stanley C. Plog, Vacation Places Rated (Redondo Beach,

CA: Fielding Worldwide, Inc., 1995).

J. Semer-Purzycki, The Travel Professional, Study Unit I

(New York: Harcourt Learning Direct, print and on-line, 1999),

J. Semer-Purzycki, Travel Vision: A Practical Guide for the Travel,

Tourism and Hospitality Industry (New York: Prentice Hall,

2000); and N. Starr, Viewpoint: An Introduction to Travel, Tourism & Hospitality, Third Edition (New York: Prentice Hall,

2000).

Stanley C. Plog, New Markets for Air Travel: Executive Summary, Vol. I (Panorama City, CA: Behavior Science Corporation, 1968).

the project was the fact that only 27 percent of

the population had flown in a commercial airplane at that time. With the jet age just beginning, seat capacity was growing at more than 20

percent per year, while passenger growth was just

8 percent. Thus, the airlines had to encourage

more people to fly.

The sponsors basic questions centered on who

does not fly, why they dont fly, and what could

be done to get them to fly. All of this is hard to

believe today, given that over 80 percent of the

population has flown, and about a third take to

the skies every year. What a change in a relatively

short period of time! Travel has become a huge

business, growing from about the twelfth-largest

industry at the time of the original research to

the largest in the United States and the world,

according to the World Tourism Organization

(WTO).

The original study provided several research

luxuries that are not common in todays fastpaced, skinnied-down research environment, and

those factors facilitated the development of new

ideas. We had the freedom to pursue offbeat ideas,

the time and money to be as thorough as we

needed in testing concepts, and the opportunity

to employ several research approaches to ensure

that our conclusions were justified. My associate

at the time (Kenneth B. Holden) and I decided

that we had to understand the psychology of

travelwhy some people travel and others do

notto provide recommendations to our travelindustry sponsors on how to get more people into

the air. Therefore, we conducted an extensive literature review on what was known about why

people dont fly (little, at the time) and investigated a number of psychological theories to determine their applicability to our research needs.

More important, we completed over 60 indepth, two-hour interviews with people who did

not fly but had sufficient income to travel whenever they wished. We explored their life histories

from childhood to the present to determine common patterns or psychological characteristics.

Then our team monitored 200 telephone calls

to airline-reservations centers from nave travelers to learn about the kinds of questions those

novices asked of reservations agents. Some of the

questions from first-time flyers are humorous in

retrospect and showed peoples lack of understanding of the dynamics of air travel. For example, they asked: If I feel sick, can I open the

window?, Are there bathrooms on board?, and

Do I tip the stewardess? We began to develop a

psychological concept from this exploratory re-

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at University of Indonesia on March 10, 2016

14 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly

JUNE 2001

TRAVELERS PSYCHOGRAPHICS

search, along with a psychographic scale that

we tested on a nationwide random sample of

1,600 households through intensive in-home

interviews.

Based on this 1967 study, we concluded that

a constellation of three primary personality characteristics defines the non-flyer personality:

(1) Generalized anxieties. Classic non-fliers feel

a continual low-level feeling of dread that

can consume much of their psychic energy.

These anxieties play out daily to inhibit

these persons from reaching out to explore

the world around them with comfort and

self-confidence. This is not to be confused

with those who suffer from a specific phobia that can be treated through behavioral

therapy. When a person has generalized

anxieties and non-focused self-doubts, the

world seems to be a dangerous place.

(2) Sense of powerlessness. These individuals

usually believe that what happens to them

in daily life is largely out of their control.

The good that comes to them and the

misfortunes encountered result mostly from

chance happenings and events. Individuals

cannot control their own destinies, they

believe.

(3) Territory boundness. Not only do these

persons not travel much as adults, but they

did relatively little traveling as children.

Their lives have been restricted for decades

in a number of ways, and they make no

attempt to expand their horizons.

At the time, we called these nonflyers

Psychocentrics, to reflect the fact that they lavish

so much personal energy on lifes small events.

These people have little time to face up to and

manage the larger problems we all encounter. Ive

since developed a more user-friendly term,

Dependables, since they try to make so much of

their daily lives predictable and dependable.

Through a series of follow-on studies, it was

possible to outline the personality at the opposite end of the spectrum. These individuals reach

out and explore the world in all of its diversity.

Self-confident and intellectually exploring, they

measure low on all measures of personal anxiety.

They make decisions rather quickly and easily,

without worrying greatly whether each choice is

correct (since life involves taking small risks every day). They have varied interests and a strong

intellectual curiosity that leads to a desire to explore the world of ideas and places. Though I

originally called them Allocentrics, I have since

relabeled them as Venturers. A more complete

JUNE 2001

CORNELL QUARTERLY CLASSIC

definition of the personality profile of each is

useful since travel patterns flow directly from

these characteristics.

Personality Profiles

Those labeled as Dependables (originally,

Psychocentrics) have a constellation of personal-

Self-confident and intellectually curious,

Venturers have a strong desire to explore

the world of ideas and places.

ity characteristics in common. Granting that no

person is a perfect examplar of any personality

type, if one could isolate persons with the archetypal Dependable personality, one would find

that typically they:

Are somewhat intellectually restricted, in that

they do not seek out new ideas and experiences on a daily basis. Compared to most

people, they read less, watch TV more, and

restrict the variety of contacts they might

have with the world around them. In brief,

they are less venturesome and less exploring

than most persons.

Are cautious and conservative in their daily

lives, preferring to avoid making important

decisions rather than confront the choices

that face everyone daily.

Are restrictive in spending discretionary income.

Uncertain about the future, they dont want

to overcommit and become financially

stretched. Although frugality is a good habit,

they choose it from a basis of fear, rather than

being motivated by good planning.

Prefer popular, well-known brands of consumer

products because the popularity of such items

makes them safe choices. (That is, everyone

likes these so they must work, or they

wouldnt be so popular.)

Face daily life with little self-confidence and low

activity levels. Some might call them more

lethargic than other people.

Often look to authority figures for guidance and

direction in their lives. Because of uncertainties about their own decision-making abilities, they may follow the advice or imitate the

actions of public personalities. Thus, using

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at University of Indonesia on March 10, 2016

Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 15

CORNELL QUARTERLY CLASSIC

TRAVELERS PSYCHOGRAPHICS

EXHIBIT 1

well-known movie or television stars and

sports figures in advertising and promotional

Psychographic

materials is more likely to influence this audipersonality types

ence than other groups.

Are passive and non-demanding in their daily

lives. They often retreat when encountering

problem situations, rather than aggressively

taking charge to handle the difficulties.

Like structure and routine in their relatively

non-varying lifestyles. As a result, they make

CENTRICCENTRICwonderful, trusted supervisors in many comDEPENDVENTURER

panies because of the predictability and rouABLE

tine nature of the lifestyles they lead. They

DEPENDABLE

NEARNEAR

VENTURER

MID-CENTRIC

serve as the flywheels of society, making cerPSYCHOCENTRIC

VENTURER

DEPENDABLE

(ALLOCENTRIC)

tain that things run according to plan wher(NEAR

(NEAR

ever they work, a good reason to label them

ALLOCENTRIC)

PSYCHOCENTRIC)

as Dependables.

Prefer to be surrounded by friends and family,

DIRECTION OF INFLUENCE

because the warm friendship and support

provided in intimate circles make them feel

comfortable and secure.

Venturers. At the opposite end of the specThe personality scale helps to explain why destitrum are the archetypal Venturers. As their name

nations rise and fall in popularity. In particular, implies, they:

tourists personality characteristics determine Are intellectually curious about and want to

explore the world around them in all of its

their travel patterns and preferences.

diversity. They continually seek new experiences and enjoy activity. They watch TV little

and prefer what is novel and unusual.

Make decisions quickly and easily, since they

recognize that life involves risks, regardless of

the choices made, and you learn to live with

those choices.

Spend discretionary income more readily. They

believe that the future will be better than the

past and they want to enjoy the fruits of their

labors now.

Like to choose new products shortly after introduction into the marketplace, rather than stick

with the most popular brands. The thrill of

discovery overrides disappointments that can

come from a new product that doesnt live up

to its promise.

Face everyday life full of self-confidence and

personal energy. They eagerly venture out to

investigate what might be new and interesting to learn more about the latest technologies, or explore exciting concepts and ideas

with others.

Look to their own judgment, rather than authority figures, for guidance and direction in

their lives. They are relatively inner-directed

and believe they can make the best choices

for themselves, rather than relying on the

opinions of experts.

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at University of Indonesia on March 10, 2016

16 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly

JUNE 2001

TRAVELERS PSYCHOGRAPHICS

Are active and relatively assertive in their daily

lives. If something does not go their way (a

flight is cancelled at an airport, a product

they bought has flaws), they will actively and

forcefully attempt to get the wrong corrected.

Prefer a day filled with varying activities and

challenges, rather than routine tasks. Although

they can have great new ideas in business or

cultural life, they may not be good at implementation since they dont like the tedious

detail work that comes with bringing ideas to

fruition.

Often prefer to be alone and somewhat meditative, even though they may appear to be

friendly and outgoing. Trusting their own

ideas, and often feeling that people around

them are somewhat dull and slow thinking,

they may avoid social situations and parties.

Personality Distribution

As I said, the archetypes of the two personalities

are rare. In national samples, based on the questions developed from the original research, the

dimensions of venturesomeness and dependability distribute on a normal curve, with a slight

skew to venturesomeness (as shown in Exhibit

1). About 2 1/2 percent of the population can be

classified as Dependables and slightly over 4 percent as Venturers. The remainder falls into the

groups in between, such as near-Dependables,

near-Venturers, or the largest group, Centrics, the

extensive middle group comprising people who

have a mixture of personality characteristics that

may lead an individual one way or the other.

The implications of this distribution are considerable. Parametric statistics can be used in most

of the research, and the personality scale helps to

explain why destinations rise and fall in popularity, as will be seen. In particular, these personality characteristics determine travel patterns and

preferences. Examining the two groups at the opposite ends of the normal curve once more allows an easier explanation of the concept. For

Dependables, research over the past three decades

points out that (compared to the average person) they:

Travel less frequently.

Stay for shorter periods of time when they

travel.

Spend less per capita at a destination.

Prefer to go by the family car, camper, or

SUV, rather than by air, because they can

take more things with them, and that makes

the trip seem more homey and less anxiety

producing.

JUNE 2001

CORNELL QUARTERLY CLASSIC

Prefer to stay in their mobile homes, with

friends and relatives, or in the lowest-cost

hotels and motels.

Prefer highly developed touristy spots, on

the logic that the popularity of these sites

means that they must be great places to visit

or else so many people wouldnt go there.

Also, heavy development supports fast-food

restaurants and convenience stores, which

offer the comfort and familiar feeling of what

they experience back home.

Tend to select recreational activities at these

destinations that also are familiarvideo

games for teenagers, and movies and miniature golf for the family.

Rate sun-and-fun spots high as destinations,

because they offer the chance to relax and

soak up the warmth on a beach or around a

pool, consistent with a preference for low

activity levels.

Typically select well-defined, escorted tours

to the best-known places for their infrequent

international trips, rather than make independent travel arrangements.

Purchase plenty of souvenirs, tee-shirts, decals, and other strong visual reminders of

where they have been.

Are likely to return to a destination again and

again once they try it because it was a good

choice.

Having reviewed what pleases the Dependable personality type, picturing the preferences

of their polar opposites is not difficult. Compared

to the people in the mid-point of our scale, the

Venturers:

Travel more frequently because travel is an

important part of exploring the world around

them.

Take relatively long trips.

Spend more each day per capita.

Take to the air more often than do other

groups (although they use all modes of

travel), because they will pay extra for the

convenience of getting there sooner to enjoy

a destination longer.

Strongly prefer unusual, underdeveloped

destinations that have retained their native

charm. More important, they avoid crowded,

touristy places.

Gladly accept inadequate or unconventional

kinds of accommodations because these become an integral part of a unique vacation

experience.

Prefer to participate in local customs and

habits and tend to avoid those events that

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at University of Indonesia on March 10, 2016

Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 17

CORNELL QUARTERLY CLASSIC

TRAVELERS PSYCHOGRAPHICS

seem too common or familiar, or those staged

for tourists.

Prefer to be on their own (FIT travel) on

international trips, even when they dont

speak the language, rather than be part of a

regimented escorted tour. Give them a car,

and theyll get around. Their self-confidence

Most destinations follow a predictable,

but uncontrolled development pattern

from birth to maturity and finally to old

age and decline.

and venturesome character makes them feel

comfortable in a wide variety of situations.

Are active when traveling, spending most of

their waking hours exploring and learning

about the places they visit, rather than soaking up the sun (or tequila).

Purchase mostly authentic local arts and

crafts, rather than souvenirs. They avoid

traditional tourist traps that sell replicas of

local cultural artifacts.

Tend to seek new destinations each year,

rather than return to previously visited places,

to add to their treasure of rich experiences.

Their travel experiences enhance their feelings of self-confidence and self-worth, leading them to take even more unusual trips in

future years.

A Destination Life Cycle

Having seen how personality determines travel

preferences, it is possible to apply those concepts

to the topic of this articlethat is, to explain

why destination areas rise and fall in popularity.

Most destinations follow a predictable, but uncontrolled development pattern from birth to

maturity and finally to old age and decline. At

each stage, the destination appeals to a different

psychographic group of travelers, who determine

the destinations character and success.

As I will explain below, my psychographic

study shows that an ideal age or stage exists for

most destinationsnamely, what might be called

young adulthood, which is an early stage of development appealing to Venturer-types. If a

destinations planners understand the psychographic curve, it is possible for them to control

development or progress along the curve and to

maintain an ideal positioning. Few places do this,

however, because local authorities dont understand the dynamics of what contributes to success and failure. Even if they do, they often lack

the power to enforce desirable changes and prevent undesirable changes. Although I suggest

maintaining a destinations appeal to Venturertype travelers, that positioning is not the only

possibility. Destination planners who understand

the psychographic curve can intentionally position their destination anywhere along the curve

including the Dependable side. As I will also explain below, that strategy can be successful if the

positioning is carefully considered.

The searchers. Just as Venturers are most interested in trying new products and services, they

like to seek out new places to visitthe forgotten, the undiscovered, the passed over, and the

unknown. Requiring few support services (such

as hotels and restaurants, organized sightseeing

activities, or things to do), Venturers would

rather go out on their own and discover what a

place has to offer. Whether the destination is

primitive or refined doesnt matter, because they

are interested in having a new experience of whatever kind.

When the Venturers return home from a trip,

they talk with friends and relatives about the best

new spots that they have discovered. Friends and

co-workers usually are quite curious about the

latest travels of acquaintances who take such interesting vacations. Some of those friends can be

classified as near-Venturers, who soon decide that

they might like to visit the intriguing places that

they have just heard about. Their more venturesome friends also provide tips on how to get there,

what to do while there, and generally how to

make the trip possible, if not easy.

When near-Venturers visit the destination (in

considerably greater numbers than the Venturers), they initiate the destinations development

cycle, because they not only ask for more services than did the Venturers, but they also tell

their friends, relatives, and associates about their

great experiences in this new place. More people

visit the destination, and they are also looking

for more services, because near-Venturers dont

like to rough it in quite the manner that Venturers do. Thus, local people develop hotels, restaurants, shops selling native items, and other

services.

In the middle of this growth-cycle stage, when

near-Venturers constitute the majority of tourist

arrivals, the travel press also will likely discover

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at University of Indonesia on March 10, 2016

18 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly

JUNE 2001

TRAVELERS PSYCHOGRAPHICS

the place. Always searching for new material (in

part because they have difficulty finding new

things to say about back roads in England, in

New England, or in Sedona, for that matter),

these writers visit the places to see for themselves

what they have to offer. Finding the places to be

different, they write ecstatically about their new

finds.

Having been discovered, the destination soon

confronts the pressures arising from rapid growth

and development. Not only has the press started

to put out the good message, but near-Venturers

also talk about their exciting vacations with their

mid-Centric friends who have Venturer leanings.

These people want to visit, too, especially because

the destination now has developed a reasonable

infrastructure. Growth rates can be high during

this period, since there are far more Centrics with

venturer leanings than there are near-Venturers.

Up to this point, everyone seems happy at the

destination. Tourism growth continues unabated,

property values rise as hotels continue to pop up,

more local residents have jobs, tax receipts have

increased, some rundown areas have been cleaned

up, and most residents believe that they have discovered the perfect industry. No ugly, smokebelching factories need to be built; unskilled

workers find good-paying jobs that require little

training in the new hotels and restaurants; and

developers are not asking for tax concessions,

unlike the situation for manufacturing industries.

Local politicians and tourism officials congratulate themselves because they think they are pretty

smart to have attracted or created what appears

to be a neverending, expanding business.

Stealthy erosion. The fly in the ointment is

that this happy growth picture has rested on the

fact that the base of prospective tourists has thus

far been steadily increasing. That is, nearVenturers outnumber Venturers, and Centrics

with Venturer leanings constitute a much larger

group than do the near-Venturers. The growth

in the prospect base continues until the midpoint of the curve. That growth rests on the fact

that the influence direction on Exhibit 1 always

moves from right to left and not the other way.

Whatever their leanings, Centrics seldom sway

the opinions of those who have Venturer blood

in their veins.

During this time, development continues almost unabated. Elected officials, who recognize

the contributions of tourists to their area and their

constituencies, happily proclaim their support of

tourism and all of its benefits for their community. So they approve plans for more hotels that

JUNE 2001

CORNELL QUARTERLY CLASSIC

will add to the tax base, the larger number of

which fall in the mid-price range and a few in

the luxury category. Moreover, politicians quickly

discover that tourists (and even vacation-home

owners) dont vote locally, so they levy taxes and

fees on the lodging, airline, and rental-car industries. Tourist shops, some representing large

chains, sprout up around town. Fast-food chains

make their appearance and help to make the place

seem more like the hometown that the visitors

just left. Moreover, with these familiar restaurants, tourists dont have to guess about what

theyre eating.

To deal with the what-to-do issue for those

who need activities beyond enjoying the destination itself, video arcades, movie theaters, and

other entertainment facilities arise. Gradually the

place takes on a more touristy look. Construction has either sprawled or high-rise hotels begin

to dominate the original architecturebuilt because land values near the center of the destination have risen so much that only high-density

buildings pencil out for developers. Local planning to control the spread of tourist sprawl has

been woefully inadequate because elected officials have seen no need to regulate a business that

they believe is a great benefit to their community. Then, when the realization finally dawns

that regulation is necessary, the officials have no

experience with such land-use planning. They

allow small businesses of all types to spring up

around town in an uncontrolled manner (e.g.,

t-shirt shops, beach or ski shops, pseudo-native

stores, bars). The place begins to look like many

other overdeveloped destinations, losing its distinctive character along the way.

Seeds of decline. Throughout this entire

process, the seeds of the destinations almostinevitable decline are already sown in the midst

of its success. Just when most people at the destination seem happiest about the success of their

efforts to grow the tourism base year after year,

unseen forces have started to move against them

that will spell trouble in the future. At some point,

the type of visitor the destination attracts tilts

toward the Dependable side of the curve. With

continued favorable publicity and increasing

popularity for a destination, Dependables also

become interested in taking a trip to this muchtalked-about place (especially if it has become part

of a package tour). Indeed, the greater its popularity, the more likely Dependables will visit, since

they prefer to make safe choices.

The psychographic curve portends several

unfortunate consequences. The destination can

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at University of Indonesia on March 10, 2016

If a destinations

planners understand the psychographic curve, it

is possible for

them to control

tourism development and to

maintain an ideal

positioning.

Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 19

CORNELL QUARTERLY CLASSIC

TRAVELERS PSYCHOGRAPHICS

EXHIBIT 2

Psychographic positions of destinations (1972)

PSYCHOCENTRIC

(DEPENDABLE)

NEAR

PSYCHO-

MID-CENTRIC

CENTRIC

Coney

Island

NEAR

ALLO-

ALLOCENTRIC

(VENTURER)

CENTRIC

Japan South Africa

and Asia Pacific

Miami

Beach

Most Florida Honolulu Caribbean Central

of

& Oahu

Europe,

U.S.

Great

Britain

Northern Hawaii Outer

Europe

Islands

Central

Mexico

Southern

Europe

draw only from shrinking segments of the population after its psychographic positioning passes

the magical mid-point on the chart. Fewer nearDependables exist than mid-Centrics with Dependable leanings, and there are fewer

Dependables than near-Dependables. Thus, the

base of potential tourists is diminishing, as those

with Venturer leanings desert this now-tawdry

destination for the next new, unspoiled place. Not

only are there fewer people in the base, but

Dependables travel less than their Venturer counterparts, they stay for shorter periods of time, and

they spend less while they are there. Since they

prefer to drive rather than fly, Dependables pay

fewer taxes (e.g., arrival taxes, rental-car taxes).

All of this compounds the misery now felt at the

destination. Nothing has changed, the locals believe, so they cant understand why fewer visitors

come each year and spend less while theyre in

town.

Maintaining Appeal

Based on the above scenario, the ideal psychographic positioning for most destinations lies

somewhere in the middle of the near-Venturer

segment. A destination at this point has the

broadest positioning appeal possible because it

covers the largest portion of the psychographic

curve. The destination usually has a reasonable

level of development, but it hasnt gotten out of

hand. In the early stages of growth at most places,

the area has improved much to everyones de-

light. The first new hotels that appear in a destination generally attempt to capture the charm

of the place (e.g., the former Rockresorts). New

wealth has improved the living conditions for

many people, especially because tourism causes

ancillary businesses to develop that serve tourism workers. Most people feel better off, which

is why most people never suspect at this point

that tourism growth should be planned and

controlled.

Planning and control is, of course, imperative

at this stage. Many unplanned destinations face

a declining future because uncontrolled growth

has discouraged Venturer-type travelers. Discount

travel packages abound to lure budget-minded

Dependable types, and those packages usually

include air and accommodations, possibly meals,

and frequently golf privileges. When 30 percent

or more of a destinations travel bookings come

from reduced-price package vacations, that destination probably will continue to go downhill

over the next couple of decades.7 Confirmation

of problems can come from a simple walk around

town. The greater the number of fast-food restaurants, video-rental stores, bargain-shopping

outlets, and abundant nighttime entertainment,

the greater the probability that those will never

go away and will continue to contribute to the

decline of the area (by discouraging Venturer-type

travelers). Store owners pay taxes and vote for

local politicians, and they have a vested interest

in keeping things the way they are.

Remaining true. Proper positioning rests on

two pillars, namely, (1) the true qualities of a

destination (what it actually offers) and (2) its

perception in the eyes of the traveling public.

Maximum success usually occurs when local

planners recognize that they must protect those

features that attracted people to their community in the first place and continue to emphasize

those aspects and the destinations other qualities in their marketing and promotional programs, and in their planning efforts. Savvy planners wont allow hotels and other buildings to

grow taller than the trees, for instance, and theyll

restrict the kinds of businesses that can come in

and regulate where those are placed. Such destinations protect and preserve open areas and ensure that local residents participate fairly in the

areas financial success. The natives also dont want

to lose what they like about where they were born

7

See, for example: Leo Paul Dana, The Social Cost of

Tourism: A Case Study of Ios, Cornell Hotel and Restaurant

Administration Quarterly, Vol. 40, No. 4 (August 1999),

pp. 6063.

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at University of Indonesia on March 10, 2016

20 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly

JUNE 2001

TRAVELERS PSYCHOGRAPHICS

CORNELL QUARTERLY CLASSIC

EXHIBIT 3

Branson

Atlantic City

Myrtle Beach

Orlando

beach resorts

Indian casinos

Hollywood

Las Vegas

theme parks

Honolulu

Florida

the Dakotas

Ohio

Kansas

Mexico (border)

Caribbean

cruises

escorted tours

(U.S. and Europe)

Alaska cruises

U.S. Parks

Illinois

Washington, D.C.

the Carolinas

Michigan

Chicago

Georgia

Kentucky

Hilton Head

Philadelphia

Los Angeles

Caribbean (most)

Ontario

London

Rome

Israel

Italy

New Mexico

Arizona

New England

Hawaii (outer is.)

Washington State

Oregon

Colorado

Wyoming

Montana

San Francisco

New York City

Quebec

Bermuda

Brazil

Mexico (interior)

Hong Kong

England

(countryside)

Scandinavia

Paris

DEPENDABLE

NEAR-DEPENDABLE

CENTRIC -DEPENDABLE

CENTRIC -VENTURER

Psychographic positions of

destinations (2001)

and grew up.8 Crowds, traffic congestion, pollution, high prices for just about everything, and a

vanishing friendliness among neighbors make the

locals want to return to a simpler life. In such a

situation, tourism and its ill effects on local culture become a controversial topic of discussion,

rather than being viewed as a boon to the area.9

Sea Pines Plantation on Hilton Head Island,

South Carolina, for instance, has maintained its

allure and charm far better than surrounding

communities at Hilton Head. By maintaining

open spaces, strictly adhering to planning guidelines, and placing restrictions on property use,

its planners have retained the resorts strength as

a tourism destination and a second-home area.

Bermuda is another destination that continues

to draw strong tourism crowds, in spite of being

expensive, because of the commitment of local

citizens and politicians to preserving its distinctive beauty and culture. Bermuda was one of the

first ports to limit the number of cruise ships that

8

See, for example, John E. Taylor, Tourism to the Cook

Islands: Retrospective and Prospective, Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, Vol. 42, No. 2 (April 2001),

pp. 7081.

9

For example, see: Susan Gregory and Kathy KoithanLouderback, Marketing a Resort Community: Estes Park at a

Precipice, Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 6 (December 1997), pp. 5259; and Matt A.

Casado, Balancing Urban Growth and Landscape Preservation: The Case of Flagstaff, Arizona, Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, Vol. 40, No. 4 (August 1999),

pp. 6469.

JUNE 2001

Russia

Tahiti

New Zealand

China (big

cities)

Poland

Costa Rica

Egypt

Jordan

Thailand

Australia

Ireland

Scotland

Kenya

Africa

expedition travel

NEAR-VENTURER

Alaskan

wilderness

Guam

Fiji

hard adventure

travel

Vietnam

Antarctica

Amazon

China (interior)

Tibet

Nepal

VENTURER

can visit, and to select upscale lines to ensure that

it gets the kind of crowd that it wants.

A Map of the World

With this in mind, destinations can be placed

on the psychographic curve, based on the types

of people who visit there the most. Exhibit 2 presents the positioning of some destinations as we

analyzed them in 1972, while Exhibit 3 summarizes where various destinations fit today. Placement on the psychographic curve comes from

the American Traveler Survey of Plog Research,

the annual study of travel habits of over 10,000

households. Exhibit 3, obviously, although more

inclusive than the original graph (Exhibit 2),

serves only as a representative list since it is impossible to cover all destinations in this article.

In comparing Exhibits 2 and 3, note how various destinations have relocated from their former

Venturesome spot toward a more Dependable

positioning. For instance, Miami Beach has

moved from a near-Dependable positioning to

the Dependable column. Florida now places in

the near-Dependable portion of the curve, rather

than in the Centric area, and Honolulu has

followed a similar path. Portions of the South

Pacific currently appeal to near-Venturers, rather

than Venturers (a relatively enviable position).

Southern Europe has especially slipped, with

England and parts of central Europe going in the

same direction. The amount of movement typically relates to the degree to which the desti-

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at University of Indonesia on March 10, 2016

Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 21

CORNELL QUARTERLY CLASSIC

TRAVELERS PSYCHOGRAPHICS

nation has become more touristy in character.

Not apparent in Exhibit 3 is the diminished

proportion of destinations today that can be classified as Venturesome in character. That is because the 1972 chart presented only a limited

number of destinations for illustrative purposes

only.

Broadband. Placement for each destination

on the chart is based on its dominant characteristic. An intriguing finding on the present-day

graph, however, is that a few destinations have

managed to create a broad appeal across the

tourist-type spectrum, attracting near-Venturers

to near-Dependables. Such places offer a wide

range of attractions, from adventurous activities

to sitting on a sunny beach; and they have maintained their original character (and popularity)

over a long time. Hawaii, Colorado, Ireland, and

Scotland are examples of this desirable category.

Dependable destination. While an uncontrolled drift across the psychographic spectrum

is not usually desirable, a destination can still

draw huge tourism crowds even though it appeals mostly to people with Dependable characteristics. Branson, Missouri, conforms to that

patternand was, in fact, conceived that way

by state planner William Boyd. Familiar with the

Plog psychographic system, Boyd recognized that

Bransons focus on country music and that its

location as a driving destination positioned it

solidly on the Dependable side of the curve.

Branson does well by being true to itself, even

though it fails to follow my general rule that destinations have the greatest chance of success by

appealing to near-Venturers.

Earthquakes

In a light-hearted (and probably derivative) discussion of the destination life cycle that appeared

in Cornell Quarterly, long-time hotelier Michael

Leven noted that a destination that reaches the

end of the cycle needs an earthquake to revive

its prospects.10 As an example of an earthquake,

he cited Atlantic Citys decision to open a boardwalk full of casinos. Two entire travel segments

have invoked earthquake-style changes since I

began my research more than 30 years ago. Those

industries are the cruise business and escorted

tours.

Cruising becomes cool. At the time of the

concepts original presentation, cruising attracted

10

See: Michael A. Leven, The Hotel Life Cycle, Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 4 (February 1985), pp. 1011.

primarily a Dependable audience. The primary

form of cruising consisted of Atlantic crossings

on ships featuring activities and an ambience that

seemed stuffy, boring, and non-venturesome to

active travelers. Who wants to sit on deck chairs

reading books or playing shuffleboard during the

daytime, only to be followed night after night by

a formal dinner and dance? Those who chose

cruise vacations tended to be Dependable types

who also had wealthan extremely narrow market segment. As a result, cruising declined in

popularity after WW II until the 1960s.

The market for cruising broadened with the

advent of Carnival Cruise Lines. It featured short

(three- or four-day), low-cost cruises to the Caribbean from Florida. Carnivals initial approach,

however, reinforced cruisings Dependable characteristics because the experience it offered was

highly structured (trips to Caribbean sun-andfun spots only, with heavy partying and social

events on board). Carnivals dramatic success in

attracting travelers prompted others to enter the

market. Some operators copied Carnivals basic

formula, but others expanded into other niches.

Contrary to the usual psychographic movement, cruising was able to broaden its appeal

backward across the psychographic spectrum

to appeal to Centrics and those with Venturer

tendencies. Current itineraries take travelers

around the world, from remote Asian ports to

Africa, Latin America, the mid-East, and the Pacific region. Selections can be made from lines

that feature ships with sails (along with scuba

diving and adventure activities when they pull

into isolated coves), small ships (300 to 500

berths) that can enter small harbors of quaint

villages not accessible by large ships, huge vessels

(over 2,500-berth capacity), and true adventure

vessels that cut through ice floes in the Antarctic

or that visit remote regions (e.g., those explored

by Darwin). By changing its character, cruising

has enjoyed strong single-digit growth rates for

most of the past decade. That trend should continue, provided that cruiselines continue to diversify their products even further. The industry

has changed from a restricted, dead-end psychographic positioning to one that works well.

Escorted tours. With extreme regimentation

and fixed schedules, escorted tours have long attracted a Dependable type of traveler. The standard tour was a stereotypical jaunt among European cathedrals and capitals, featuring, say, 8

countries in 11 days. The standard formula

moved people in and out of hotels and onto buses

daily, zipped them through some beautiful coun-

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at University of Indonesia on March 10, 2016

22 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly

JUNE 2001

TRAVELERS PSYCHOGRAPHICS

tryside in a hurry on the way to the next major

city, and provided a quick feeling of the culture

with costumed folk dancers or singers at restaurants with stylized dcor in the evening. Only

novice travelers, however, could like that kind of

an introduction to a country.

For a number of years I worked with tour

operators to show them how they were limiting

their potential markets by using such an inflexible approach. They did not agree with my ideas,

however, because until recently most tour companies were run by first-generation entrepreneurs

who grew their companies quite successfully with

that limited formula. Thats what they knew and

thats what they offered, even in the face of declining numbers of clients each year.

To appeal to travelers with Venturer characteristics, however, I insisted that the tour companies needed to change their products by offering less regimentation in schedules (more free

time on the tours, fewer stops at touristy shops

along the way), a better class of hotels, and itineraries that include less-popular or less-wellknown places. Indeed, some tour companies are

doing that now, albeit gradually.

Tour products now include the back roads of

the United States, forgotten and overlooked

places of Europe, treks through the Himalayas

with Sherpa guides (e.g., Snow Lion Adventures),

bicycling through New England in the fall or

through the wine country of France, and excursions into the Amazon. Some university alumni

associations offer particularly interesting excursions. These feature trips to relatively unknown

places with professors as lecturers or chartered

small ships for adventure travel into places not

reachable by land. Thus, tours now have altered

their image and have a much broader psychographic appeal than in the past. The tour business as a whole started on a growth curve about

1997, after losing market share for a couple of

decades to air-plus-hotel travel packages. As with

cruising, the changes in tour packages should

mean that growth will continue for the next decade or so.

Everyones Doing It

Perhaps the greatest change in the travel industry in the past 30 years is the overall growth in

travel. Leisure travel has changed from being considered an expensive luxury item enjoyed only

infrequently by the masses to being a psychological necessity. People are convinced that the

pressures and strains of todays lifestyle lead to a

need to recover periodically through the therapy

JUNE 2001

CORNELL QUARTERLY CLASSIC

of getting away from it all. That means that

Dependables, following the leadership of their

more venturesome colleagues, travel more today

than did their lookalikes of a number of years

ago. Part of the reason for this is that so many

destinations have been well developed, encouraging Dependables to go to places they wouldnt

previously have considered.

Many unplanned destinations face a

declining future because uncontrolled

growth has discouraged influential

Venturer-type travelers.

Another earthquake. A related complicating

element comes from the fact that Venturers and

near-Venturers also travel more than in the past

no surprise, because they have been leading this

trend for three decades. Venturers still seek unspoiled and unusual locations, but since travel is

now so common the search for new kinds of vacation experiences and places to go has become

more difficult. As a result Venturer-types take

trips that they might not have considered in the

past. One beneficiary of this quest, ironically, is

the gaming industry. An activity preferred most

by Dependable and near-Dependable types, gaming venues now draw visits from those with Venturer leanings. These travelers are not visiting so

much to gamble as to look at the new, spectacular hotels and to take in the latest shows in Las

Vegas. Chances are they will make it a short trip,

owing to their allergy to the touristy elements of

the destination. As I related above, cruising and

tours also have attracted Venturer types to some

degree.

Convergence? If Dependables are traveling

more and Venturers are showing up in typical

Dependable destinations, one might wonder

whether the psychographic segments are somehow converging. I do not find this to be the case.

Two factors still distinguish the two personality

archetypesthe level of travel and the nature of

the travel experience. While todays Dependables

are traveling more than yesterdays Dependables,

they still are no match for todays Venturer types,

who travel even more still. Similarly, although

both Venturers and Dependables may purchase

cruises, the Dependables limit themselves prima-

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at University of Indonesia on March 10, 2016

Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 23

CORNELL QUARTERLY CLASSIC

TRAVELERS PSYCHOGRAPHICS

rily to visiting well-trod destinations, such as the

Caribbean or Alaska. The Venturers are the ones

who are dropping themselves off to dive on the

Dry Tortugas or taking cruises to the Antarctic.

Revised and Refined

The cumulative

impact of tawdry

development may

turn more of the

public away from

the strong emphasis they currently place on

travel in their

lives.

That is not to say that my organization has not

refined the psychographic system that was first

devised over 30 years ago. It continues in use to

position destinations and various travel products,

such as cruise lines, hotel chains, and airlines. It

has formed the basis for helping some of the largest travel-agency conglomerates refocus their

business strategies to concentrate more heavily

on the most important leisure segments. Several

travel publications have also changed the way

they present themselves to their readers and advertisers based on the psychographic research.

This conceptual framework also helps travel

suppliers learn how to target specific segments

with messages that address their psychological

needs, and to select a media mix that will reach

their customers more cost effectively. Finally, as

should be obvious in reading descriptions of the

personality types, these concepts apply to other

businesses. Industries as diverse as automobiles

(BMW, Saab) and beverages (Molson Breweries

of Canada) have used psychographics to reposition their products to capture greater market

share or to introduce new brands.

Genesis. The first and most important use of

the psychographic concept still relates to explaining why destinations rise and fall in popularity.

Using these ideas, destinations around the globe

have repositioned themselves to increase their

tourism prospects, and some have taken steps to

improve the quality of what they offer the traveling public. Among the destinations that have

employed the concepts to change the way they

are perceived by travelers are Australia, various

provinces of Canada, post-handover Hong Kong,

southern Portugal and the Estoril Coast, Switzerland, and Tahiti, as well as such U.S. locations as Beverly Hills, Detroit, and Omaha.

With all of this effort, however, I maintain

that most destinations managers dont understand that they continue to shoot themselves in

the foot by allowing unfocused development to

trample the once-beautiful areas that so delighted

the Venturer-type travelers. Destinations can be

preserved and still enjoy continued, growing

prosperity. The reasons for why this fails to occur are beyond the scope of this article, but I

will write about them in a future Cornell Quarterly article. I want to focus an entire article on

this matter because I am concerned about

the future economic health of an industry I love

as it seems to be choosing a path towards selfdestruction. Slow though the forces might be,

the cumulative impact of tawdry development

in so many places will, I fear, turn more of the

public away from the strong emphasis they currently place on travel in their lives. If travel ceases

to be edifying, people will turn to other outlets

for instance, home entertainment, which continues to grow faster than leisure travel.

The travel product must improve over time,

or an increasingly sophisticated public will decide that taking a trip is too expensive in money

or time for the experience receivedand just isnt

all that much fun when you get there. The experience at the destination must make the effort

and expenditure of time and money worthwhile.

If the golden travel goose dies a slow death, no

travel surgeon will be able to revive it. As travel

receipts decline, local governments wont be able

to afford to tear down overbuilt resorts and replace them with fresh buildings, open spaces, or

the natural scenery that was paved over by sprawling development. That scenario is a sad thought,

but a real possibility. The travel industry carries

responsibility on its shoulders for its success and

its problems. Tourism planners need to look no

further than the mirror to know who must fix

the problems.

Stanley Plog

is founder of NFO/Plog

Research (scplog@aol.com).

2001, Cornell University; an invited paper.

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at University of Indonesia on March 10, 2016

24 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly

JUNE 2001

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Traditional Food Within The Tourism Destination MarketingDokumen31 halamanTraditional Food Within The Tourism Destination MarketingVasilena Barbayaneva100% (1)

- Preview PDFDokumen94 halamanPreview PDFVince Kho DucayBelum ada peringkat

- Human Resource Management in The Hospitality Industry: Ninth EditionDokumen36 halamanHuman Resource Management in The Hospitality Industry: Ninth EditionRadi Adie PermanaBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding of Sustainable Tourism Among Russian Tourism ManagersDokumen6 halamanUnderstanding of Sustainable Tourism Among Russian Tourism ManagersIda Ayu SutariniBelum ada peringkat

- Citizenship and Teacher Education Journal Vol 1 No.2Dokumen109 halamanCitizenship and Teacher Education Journal Vol 1 No.2Bobby PutrawanBelum ada peringkat

- Pre-Training Manual For Photo TraineesDokumen15 halamanPre-Training Manual For Photo TraineesAY RABelum ada peringkat

- Anna Pollock Can Tourism Fulfill Its Regenerative Potential ATMEX 2019Dokumen56 halamanAnna Pollock Can Tourism Fulfill Its Regenerative Potential ATMEX 2019ATMEX100% (1)

- USALI 10th VS 11th EditionDokumen7 halamanUSALI 10th VS 11th EditionvictoregomezBelum ada peringkat

- Hubbart Formula FODokumen4 halamanHubbart Formula FOVivitlasriBelum ada peringkat

- A Conceptual Model of Destination BrandingDokumen9 halamanA Conceptual Model of Destination BrandingRoberta DiuanaBelum ada peringkat

- Applying Value Drivers To Hotel ValuationDokumen20 halamanApplying Value Drivers To Hotel ValuationErsan YildirimBelum ada peringkat

- Carnival Complete AgreementDokumen21 halamanCarnival Complete AgreementSabrina LoloBelum ada peringkat

- Project On Customer RetentionDokumen8 halamanProject On Customer RetentionRavi SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- Conference and Banqueting.Dokumen14 halamanConference and Banqueting.john mwangiBelum ada peringkat

- Educational Institute BooksDokumen1 halamanEducational Institute BooksShane ReinhartBelum ada peringkat

- Marketing - 2: Debasish Nayak PGDM 2 Year Krupajal Business SchoolDokumen14 halamanMarketing - 2: Debasish Nayak PGDM 2 Year Krupajal Business SchoolDebasish NayakBelum ada peringkat

- Property Level Benchmarking With STAR Reports ReviewDokumen83 halamanProperty Level Benchmarking With STAR Reports ReviewmukulBelum ada peringkat

- UNIT 1 The Contemporary Hospitality IndustryDokumen5 halamanUNIT 1 The Contemporary Hospitality Industrychandni0810Belum ada peringkat

- 8 Things You Need To Know About ErgonomicsDokumen4 halaman8 Things You Need To Know About ErgonomicsAini Bin MurniBelum ada peringkat

- 2017 Trends Report - The Uncompromising Customer: Addressing The Paradoxes of The Age of IDokumen33 halaman2017 Trends Report - The Uncompromising Customer: Addressing The Paradoxes of The Age of ITatianaBelum ada peringkat

- Btec Learner Assessment Submission and DeclarationDokumen7 halamanBtec Learner Assessment Submission and DeclarationmohBelum ada peringkat

- Hospitality HRM (Past, Present & Future)Dokumen23 halamanHospitality HRM (Past, Present & Future)anisjjBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 1Dokumen48 halamanChapter 1CharleneKronstedt100% (1)

- 1Dokumen23 halaman1Shivaraj BagewadiBelum ada peringkat

- Hotel and Classification of HotelsDokumen13 halamanHotel and Classification of HotelsVanezita Camavilca FigueroaBelum ada peringkat

- Tourism Supply Chain Conceptual FrameworkDokumen11 halamanTourism Supply Chain Conceptual FrameworkPairach PiboonrungrojBelum ada peringkat

- Tourism Issues in Public DomainDokumen55 halamanTourism Issues in Public DomainEquitable Tourism Options (EQUATIONS)Belum ada peringkat

- USALI ChangesDokumen4 halamanUSALI ChangesYayat MiharyaBelum ada peringkat

- Tourism Services QualityDokumen24 halamanTourism Services QualityArdiansyah MahamelBelum ada peringkat

- Competitiveness in Romania's Hospitality SectorDokumen11 halamanCompetitiveness in Romania's Hospitality Sectorandreyu6000100% (1)

- Strategic Marketing PlanningDokumen21 halamanStrategic Marketing PlanningYasmin YousufBelum ada peringkat

- 55-International Tourism A Global Perspective-LibreDokumen418 halaman55-International Tourism A Global Perspective-LibreEnrique Gonzalez JohansenBelum ada peringkat

- Boutique Hotel Consulting Firm Evaluates Iconic PropertiesDokumen6 halamanBoutique Hotel Consulting Firm Evaluates Iconic PropertiesJane HwangBelum ada peringkat

- Daimler-Benz Restructuring: Refocusing on Core CompetencyDokumen11 halamanDaimler-Benz Restructuring: Refocusing on Core Competencykriti25Belum ada peringkat

- The Impact of Culture On TourismDokumen160 halamanThe Impact of Culture On TourismYulvina Kusuma Putri100% (1)

- Hotel Restaurant TourismDokumen4 halamanHotel Restaurant TourismAyu SetiyokoBelum ada peringkat

- Tourist Statistics 2017 Book20181221073646 PDFDokumen77 halamanTourist Statistics 2017 Book20181221073646 PDFvijukeaswarBelum ada peringkat

- MARCH 2017 L4 Diploma in Hospitality Management Qualification SpecificationDokumen35 halamanMARCH 2017 L4 Diploma in Hospitality Management Qualification SpecificationCothm EmCupBelum ada peringkat

- Laws and Regulations For Setting Up A Business in JapanDokumen60 halamanLaws and Regulations For Setting Up A Business in JapanSantiago CuetoBelum ada peringkat

- Promotion of Tourism Through Rich Folk Culture of West BengalDokumen6 halamanPromotion of Tourism Through Rich Folk Culture of West Bengalwfshams100% (1)

- Question - Contemporary Hospitality IndustryDokumen7 halamanQuestion - Contemporary Hospitality Industrymaddyme08100% (2)

- Bottomline 2010 12 - 01 PDFDokumen32 halamanBottomline 2010 12 - 01 PDFGerson Napoleon Turcios100% (1)

- The Hotel Competitor Analysis Tool (H-CAT) :: A Strategic Tool For ManagersDokumen16 halamanThe Hotel Competitor Analysis Tool (H-CAT) :: A Strategic Tool For ManagersSahil AhammedBelum ada peringkat

- Intellectual Property A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionDari EverandIntellectual Property A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionBelum ada peringkat

- Traditions of Sustainability in Tourism StudiesDokumen20 halamanTraditions of Sustainability in Tourism Studiesalzghoul0% (1)

- Understanding Cultural DiversityDokumen14 halamanUnderstanding Cultural DiversityCarolina Ramirez100% (1)

- Fuzzy Data Warehousing For Performance Measurement - Concept and Implementation (Fasel 2014-03-03)Dokumen252 halamanFuzzy Data Warehousing For Performance Measurement - Concept and Implementation (Fasel 2014-03-03)Guillermo DavidBelum ada peringkat

- Hotel SchoolDokumen44 halamanHotel Schooltrellon_devteamBelum ada peringkat

- Experience, Brand Prestige, Perceived Value (Functional, Hedonic, Social, andDokumen9 halamanExperience, Brand Prestige, Perceived Value (Functional, Hedonic, Social, andzoe_zoeBelum ada peringkat

- Wine Tourist ProfileDokumen11 halamanWine Tourist ProfileJoaoPintoBelum ada peringkat

- Creative Tourism Drives Local DevelopmentDokumen11 halamanCreative Tourism Drives Local DevelopmentMaria TurcuBelum ada peringkat

- Strategic Alliance and Franchising in Hospitality IndustryDokumen3 halamanStrategic Alliance and Franchising in Hospitality IndustryLee BK100% (1)

- Principles of Hotel Management, VP Kainthola (2009)Dokumen381 halamanPrinciples of Hotel Management, VP Kainthola (2009)guest9950% (2)

- Cultural Effects On Consumer Behavior Paper 122610Dokumen25 halamanCultural Effects On Consumer Behavior Paper 122610ushalatasharmaBelum ada peringkat

- Sha566 TurnadotDokumen7 halamanSha566 TurnadotBambang JuliantoBelum ada peringkat

- Tourism in Transitions: Dieter K. Müller Marek Więckowski EditorsDokumen212 halamanTourism in Transitions: Dieter K. Müller Marek Więckowski EditorsraisincookiesBelum ada peringkat

- Hospitality IndustryDokumen44 halamanHospitality IndustrySanjay Karn100% (1)

- Stanley PlogDokumen12 halamanStanley PlogDennis Sabillah RamadhanBelum ada peringkat

- WTO Vol 4Dokumen9 halamanWTO Vol 4Dennis Sabillah RamadhanBelum ada peringkat

- Serial Number AOE 3Dokumen1 halamanSerial Number AOE 3Dennis Sabillah RamadhanBelum ada peringkat

- Serial Number AOE 3Dokumen1 halamanSerial Number AOE 3Dennis Sabillah RamadhanBelum ada peringkat

- Igcse Topic 1 Lesson 1 Water Cycle IgcseDokumen25 halamanIgcse Topic 1 Lesson 1 Water Cycle Igcsedanielphilip68Belum ada peringkat

- Calculus-Solutions 2.4Dokumen5 halamanCalculus-Solutions 2.4MUHAMMAD ALI KhokharBelum ada peringkat

- 10.3 The Nerve ImpulseDokumen20 halaman10.3 The Nerve ImpulseazwelljohnsonBelum ada peringkat

- Teaching Goal Examples: Retrieved From Http://sitemaker - Umich.edu/ginapchaney/teaching - Goals - PhilosophyDokumen1 halamanTeaching Goal Examples: Retrieved From Http://sitemaker - Umich.edu/ginapchaney/teaching - Goals - PhilosophyFang GohBelum ada peringkat

- Final Reflection MemoDokumen4 halamanFinal Reflection Memoapi-277301978Belum ada peringkat

- 125 25 AnalysisDokumen8 halaman125 25 AnalysismahakBelum ada peringkat

- The Pipelined RiSC-16 ComputerDokumen9 halamanThe Pipelined RiSC-16 Computerkb_lu232Belum ada peringkat

- Gen Ed Day 5Dokumen5 halamanGen Ed Day 5Jessica Villanueva100% (1)

- CL ProgrammingDokumen586 halamanCL Programmingks_180664986Belum ada peringkat

- PHYSICS-CHAPTER-1-QUESTIONSDokumen5 halamanPHYSICS-CHAPTER-1-QUESTIONSMohamadBelum ada peringkat

- SRS For VCSDokumen14 halamanSRS For VCSKartikay SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- Cover LetterDokumen7 halamanCover Letterrohan guptaBelum ada peringkat

- Higher Unit 06b Check in Test Linear Graphs Coordinate GeometryDokumen7 halamanHigher Unit 06b Check in Test Linear Graphs Coordinate GeometryPrishaa DharnidharkaBelum ada peringkat

- 4.000in 0.330wall IU CYX105-120 XT39 (4.875 X 2.688 TJ) 12P 15BDokumen3 halaman4.000in 0.330wall IU CYX105-120 XT39 (4.875 X 2.688 TJ) 12P 15BjohangomezruizBelum ada peringkat

- Distributed Flow Routing: Venkatesh Merwade, Center For Research in Water ResourcesDokumen20 halamanDistributed Flow Routing: Venkatesh Merwade, Center For Research in Water Resourceszarakkhan masoodBelum ada peringkat

- Master's Thesis on Social Work Field WorkDokumen18 halamanMaster's Thesis on Social Work Field WorkJona D'john100% (1)

- Dynamic Workload Console Installation GuideDokumen245 halamanDynamic Workload Console Installation GuideGeetha Power100% (1)

- A Post Colonial Critical History of Heart of DarknessDokumen7 halamanA Post Colonial Critical History of Heart of DarknessGuido JablonowskyBelum ada peringkat

- First Order Shear Deformation TheoryDokumen11 halamanFirst Order Shear Deformation TheoryShlokBelum ada peringkat

- Marketing Theory and PracticeDokumen18 halamanMarketing Theory and PracticeRohit SahniBelum ada peringkat

- Costco Cover Letter ExamplesDokumen6 halamanCostco Cover Letter Examplesxwxxoyvhf100% (1)

- Quality Assurance in BacteriologyDokumen28 halamanQuality Assurance in BacteriologyAuguz Francis Acena50% (2)

- EMC ChecklistDokumen5 halamanEMC ChecklistZulkarnain DahalanBelum ada peringkat

- VP Supply Chain in Columbus OH Resume Belinda SalsbureyDokumen2 halamanVP Supply Chain in Columbus OH Resume Belinda SalsbureyBelinda Salsburey100% (1)

- 2.3.4 Design Values of Actions: BS EN 1990: A1.2.2 & NaDokumen3 halaman2.3.4 Design Values of Actions: BS EN 1990: A1.2.2 & NaSrini VasanBelum ada peringkat

- Decision Making in A Crisis What Every Leader Needs To KnowDokumen10 halamanDecision Making in A Crisis What Every Leader Needs To KnowFradegnis DiazBelum ada peringkat

- Economic Problems of Population ChangeDokumen27 halamanEconomic Problems of Population ChangeAner Salčinović100% (1)

- The Bright Side of TravellingDokumen6 halamanThe Bright Side of TravellingFatin Amirah AzizBelum ada peringkat

- Kim Mirasol Resume Updated 15octDokumen1 halamanKim Mirasol Resume Updated 15octKim Alexis MirasolBelum ada peringkat

- Lethe Berner Keep Warm Drawer BHW 70 2 MANDokumen17 halamanLethe Berner Keep Warm Drawer BHW 70 2 MANGolden OdyesseyBelum ada peringkat