Neonatal Onset Epilepsies

Diunggah oleh

Asri RachmawatiHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Neonatal Onset Epilepsies

Diunggah oleh

Asri RachmawatiHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Epilepsies of neonatal

onset: seizure type and

evolution

Kazuyoshi Watanabe* MD PhD, Professor of Pediatrics,

Nagoya University School of Medicine, Nagoya;

Kiyokuni Miura MD PhD, Division of Pediatric Neurology,

Aichi Prefectural Colony, Kasugai;

Jun Natsume MD PhD, Department of Pediatrics, Nagoya

University School of Medicine, Nagoya;

Fumio Hayakawa MD PhD, Department of Pediatrics, AnjoKosei Hospital, Anjo;

Sunao Furune MD PhD, Division of Pediatric Neurology, First

Red Cross Hospital;

Akihisa Okumura MD, Department of Pediatrics, Nagoya

University School of Medicine; Nagoya; Japan.

*Correspondence to first author at Department of

Pediatrics, Nagoya University School of Medicine, 65

Tsurumai-cho, Showa-ku, Nagoya 466-8550, Japan.

E-mail: kwatana@med.nagoya-u.ac.jp

Neonatal seizures are a manifestation of a variety of organic,

metabolic, or functional disorders of the neonatal brain. Most

are caused by perinatal hypoxicischemic encephalopathy

(HIE), intracranial hemorrhage, or infections. Seizures occurring in neonates with HIE or meningitis are not classified as

epilepsy; they should be classified as situation-related or

occasional seizures. These occasional seizures differ from

epilepsy, a chronic seizure disorder, even if they are followed

by symptomatic epilepsy due to an underlying disorder

(Watanabe et al. 1982b, Clancy and Legido 1991). Previous

studies on neonatal seizures have described seizures of all etiologies, including many occasional seizures (Lombroso

1996). The International Classification (Commission on

Classification and Terminology of the International League

Against Epilepsy 1989) classifies neonatal seizures as undetermined epilepsies with both generalized and focal

seizures. Moreover, it is uncommon for neonates to have

simultaneous generalized and focal seizures.

Epileptic syndromes may change with age. The term agedependent epileptic encephalopathy has been used to

describe a disorder which changes from early infantile

epileptic encephalopathy to West syndrome and then to

LennoxGastaut syndrome (Ohtsuka et al. 1986). However,

other changes with age are also present in epilepsies of

neonatal onset.

The aim of this study is to investigate seizure types of true

neonatal epilepsies and their evolution.

Method

PATIENTS

Most neonatal seizures are occasional seizures and not true

epilepsy. This study investigates seizure types of true neonatal

epilepsies and their evolution with development. Seventy-five

children with epilepsies of onset within 1 month of life, who

were examined between 1970 and 1995, and whose seizure

types could be confirmed with ictal EEG recordings, were

studied. The patients were followed up for a minimum of 3

years and the evolution of epileptic syndromes was

investigated. Sixty-three (84%) of 75 patients had partial

seizures, while nine had generalized seizures, and only three

had both generalized and partial seizures. Twenty-three of 24

neonates with benign familial or non-familial neonatal

convulsions presented with partial seizures; these syndromes

should not necessarily be categorized into generalized epilepsy

as they are in the present International Classification. Agedependent changes were a common feature of symptomatic

neonatal epilepsies. Eighteen (41%) of 44 patients with

symptomatic epilepsies of neonatal onset developed West

syndrome in infancy. Fifteen (83%) of these 18 patients

presented with symptomatic localization-related epilepsy in

the neonatal period. In seven of these 15 patients, West

syndrome was followed by localization-related epilepsy.

Symptomatic localization-related epilepsy with transient

West syndrome in infancy is another type of age-dependent

epileptic syndrome.

318

Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 1999, 41: 318322

Seventy-five infants participated in the study. Their gestational ages ranged from 37 to 41 weeks, except one who

was born at 36 weeks; birthweights ranged from 1670 to

4300 g. The exclusion of preterm infants was not intentional but may be due to preterm babies being prone to acute

symptomatic seizures. Also, the absolute number of

preterm babies is fewer than term babies. Seven patients

died before 1 year of age. The other patients were followed

up for a minimum of 3 years and their ages at the last followup ranged from 3 to 19 years.

PROCEDURE

Pediatric neurologists with an expertise in epilepsy and

neonatal electroencephalograms (EEG) collected data from

the neonatal-care units of four hospitals on patients who

had onset of epilepsies within 1 month of life. Information

was obtained retrospectively and was available on patients

examined between 1970 and 1995 in one hospital and

between 1984 and 1995 in the others. The inclusion criterion was the occurrence of repetitive seizures due to causes

other than acute brain insults such as hypoxicischemic

events, intracranial hemorrhage, meningitis, encephalitis,

hypocalcemia and other electrolyte abnormalities, or hypoglycemia. All neonates alleged to have had more than one

seizure and who were admitted to the neonatal-care unit

were monitored with EEG for a maximum of 3 hours. Only

patients with seizures confirmed to be epileptic in nature

with ictal EEGs were included. Thus, neonates having infrequent, self-limited, or equivocal epileptic seizures were

excluded. After the neonatal period, the type of seizure was

usually diagnosed clinically, although frequent daily

seizures were recorded with video and EEG monitoring.

Patients reported in previous studies (Watanabe et al.1976,

Watanabe 1981, Aso et al. 1992, Miura et al. 1993) were eligible for inclusion. The following information was collected

using a standardized protocol: gestational age, birthweight,

family history, pre-, peri- and postnatal histories, the presence or absence of underlying disorders, details of neonatal

seizures, ictal and interictal EEG findings in the neonatal

period, neuroimaging studies including CT and/or MRI,

EEG findings during the clinical course, syndromic classification during the clinical course, details of seizure, and

developmental outcome.

The seizure types and syndromes were determined according to those set out by the Commission on Classification and

Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy

(1981, 1989) with some modifications. The seizure types in

the neonatal period were confirmed with ictal EEG recordings

and classified into partial and/or generalized seizures. But

semiological classification of seizures was not studied for the

following reasons: simultaneous video/EEG recordings were

not performed in all cases, seizure manifestations were protean in neonatal seizures, and the same patient displayed different types of clinical seizures.

Subjects were categorized etiologically throughout followup, because of difficulty in knowing whether a neonate was

neurologically or developmentally normal. Neuroimaging

examinations performed during follow-up were also taken

into consideration. Some disorders or syndromes, such as

Ohtahara syndrome, were easily diagnosed during the neonatal period because they have characteristic features, but others need longer follow-up for accurate diagnosis. Idiopathic

epilepsy is defined as an epilepsy having no underlying cause

other than a possible hereditary predisposition. This was

diagnosed if a subject had no underlying disorders, seizures

were easily controlled, and neurodevelopmental status at follow-up was normal. Symptomatic epilepsies are consequences of a known or suspected disorder of the brain, and

are diagnosed if the subject had an underlying disorder, a

moderate or severe learning disability, or neurological abnor-

malities at follow-up, even if no underlying disorder was

detected. Cryptogenic epilepsy is an epileptic disorder whose

cause is hidden or occult. In this study, it was diagnosed when

a patient had mild developmental delay or seizures that were

refractory for the follow-up period but with no detectable

underlying disorders.

Results

SEIZURE TYPES IN THE NEONATAL PERIOD

Table I shows the type of seizures and epileptic syndromes

occurring in the 75 patients during the neonatal period.

Of the 24 children with idiopathic epilepsies, seven of

eight infants with benign familial neonatal convulsions

(BFNC) presented with partial seizures and one with generalized seizures. The latter displayed generalized tonicclonic

convulsions associated with generalized desynchronization

followed by semirhythmic alpha/theta waves in all regions of

the brain. Of the eight infants with BFNC, the age at onset

was 1 to 6 days in seven and 23 days in one. All of the 16

infants with benign neonatal convulsions (BNC) presented

with partial seizures. The age at onset was 1 to 7 days in 13

neonates and 10 to 22 days in three.

Of the 44 infants with symptomatic epilepsy, five of the

eight infants with early infantile epileptic encephalopathy

(EIEE) with suppressionburst presented with generalized

seizures, namely tonic spasms, and three presented with

tonic spasms and partial seizures. Their age at onset was 1 to

21 days. Two infants with early myoclonic encephalopathy

(EME) had non-ketotic hyperglycinemia and exhibited partial seizures and erratic myoclonia but no generalized

seizures, such as massive myoclonic seizures or tonic

spasms, in the neonatal period. Their age at onset was 1 day

and 25 days, respectively. The EEG of these infants showed

suppressionburst pattern, with bursts lasting from 1 to 5

seconds and suppression lasting from 13 to 60 seconds.

Three of the five infants with holoprosencephaly had semilober type holoprosencephaly and displayed generalized

tonic seizures characterized electroencphalographically by

Table I: Epilepsies of neonatal onset occurring during the neonatal period

Epileptic syndrome

Idiopathic

Benign familial neonatal

convulsions

Benign neonatal convulsions

Symptomatic

Early infantile epileptic

encephalopathy

Early myoclonic encephalopathy

Holoprosencephaly

Tuberous sclerosis

Othera

Cryptogenic

Total

Nr of

patients

Seizure types in the neonatal period

Partial

Generalized

PS+GS

seizures (PS)

seizures (GS)

16

16

2

5

4

25

7

75

2

2

4

25

7

63

0

3

0

0

0

9

0

0

0

0

0

3

aAicardi syndrome, 1; localized cortical dysplasia, 4; microcephaly, 3; 18-trisomy, 2; porencephaly,

1; lissencephaly, 1; congenital cytomegalovirus infection, 1; peroxysomal disease, 1; moderate or

severe learning disability with or without neuroimaging abnormalities, 11.

Epilepsy of Neonatal Onset Kazuyoshi Watanabe et al. 319

desynchronization and recruiting rhythms. Their interictal

EEGs disclosed continuous high-amplitude rhythmic

alpha/theta activity with anteriorposterior amplitude gradient in wakefulness, which became discontinuous and asynchronous during sleep. The other two had alobar

holoprosencephaly and demonstrated rhythmic alpha/theta

activity only in anterior regions. The ictal EEG showed lowvoltage beta waves, followed by rhythmic activity of decreasing frequency and increasing amplitude, and ending with

delta waves in both frontotemporal regions corresponding to

the presence of the forebrain. The clinical seizure consisted

of opening of the eyes, tonic extension of both legs followed

by mouth opening and closing. This might be considered a

variant of a generalized tonic seizure due to the absence of the

posterior brain, although it was provisionally classified as partial seizure by definition. Their age at onset ranged from 0 to

15 days. All four neonates with tuberous sclerosis presented

with partial seizures at 0 to 20 days of age. The other 25

infants with symptomatic epilepsy presented with partial

seizures at 0 to 30 days of age. All seven neonates considered

to have cryptogenic epilepsy presented with partial seizures

at 2 to 14 days of age.

In all, 63 neonates presented with partial seizures, nine

with generalized seizures, and three with both types of

seizures. The neonates with both types of seizures had EIEE.

Partial seizures were observed in both idiopathic and symp-

Table II: Evolution of epileptic syndromes (N=51)

Epileptic syndromes

EIEE and EME

EIEE

WS

EIEE

WS

EIEE

SGE

EIEE

SLRE

EIEE

Seizure free

EIEE

Early death

EME

WS

Holoprosencephaly

SGE

WS

SGE

LRE

SGE

Seizure free

SLRE

SLRE

Tuberous sclerosis

SLRE

SLRE

SLRE

WS

SLRE

WS

Other symptomatic epilepsies

SLRE

WS

SLRE

WS

SLRE

WS

SLRE

WS

SLRE

SLRE

SLRE

Seizure free

Cryptogenic epilepsies

CLRE

CLRE

Nr of patients

SLRE

LGS

1

1

3

1

1

1

2

SLRE

LGS

1

1

1

2

1

1

2

SLRE

SGE/LGS

SGE

SLRE

Death

Seizure free

4

4

1

1

10

5

7

EIEE, early infantile epileptic encephalopathy; EME, early

myoclonic encephalopathy; WS, West syndrome;

LGS: LennoxGastaut syndrome; SLRE, symptomatic localizationrelated epilepsy; SGE, symptomatic generalized epilepsy;

CLRE, cryptogenic localization-related epilepsy.

320

Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 1999, 41: 318322

tomatic cases, whereas generalized seizures usually took a

form of epileptic spasms or tonic seizures, and were present

mainly in EIEE and semilobar holoprosencephaly.

EVOLUTION OF EPILEPTIC SYNDROMES

Two of the eight infants with BFNC had seizures in infancy

and early childhood, which were easily controlled. It is not

known whether later seizures differed from neonatal

seizures. Three of our 16 patients with BNC had a recurrence

of seizures at 1, 3, and 12 months of age, respectively, all of

which could be easily controlled.

Table II illustrates the evolution of epileptic syndromes,

excluding infants with idiopathic epilepsy. Two of the eight

infants with EIEE developed West syndrome, one developed

symptomatic localization-related epilepsy, one developed

LennoxGastaut syndrome, three developed symptomatic

generalized epilepsy, and one developed localization-related

epilepsy. Two infants with EME developed West syndrome

transiently but had a final diagnosis of localization-related

epilepsy with partial seizures and erratic myoclonia. One of

the three infants with holoprosencephaly, presenting with

symptomatic generalized epilepsy in the neonatal period,

developed West syndrome and then LennoxGastaut syndrome; one developed symptomatic localization-related

epilepsy; and one eventually became seizure-free. Two with

localization-related epilepsy continued to have partial

seizures. All four patients with tuberous sclerosis presented

with symptomatic localization-related epilepsy in the neonatal period. One continued to have partial seizures without

evolutionary changes of epileptic syndrome, and three

developed West syndrome, followed by localization-related

epilepsy in one and symptomatic generalized epilepsy or

LennoxGastaut syndrome in two. Ten of the 25 infants who

presented with other symptomatic localization-related

epilepsies in the neonatal period developed West syndrome,

followed by symptomatic generalized epilepsy in four and

localization-related epilepsy in four; 10 continued to have

partial seizures; and five became seizure-free. All patients

with cryptogenic localization-related epilepsy did not

demonstrate any evolution of epileptic syndrome and continued to have partial seizures.

As a whole, 18 (41%) of 44 patients with symptomatic

epilepsies of neonatal onset developed West syndrome in

infancy. Thirteen of these 18 patients presented with symptomatic localization-related epilepsy in the neonatal period.

Two of them had EIEE, two had EME, and one had semilobar

holoprosencephaly. The two patients with EME were diagnosed as having localization-related epilepsy in the neonatal

period. Thus, 15 (83%) of the above 18 patients presented

with symptomatic localization-related epilepsy in the neonatal period, and in seven of these 15 patients, West syndrome

was followed by localization-related epilepsy.

Discussion

Most of the neonates under study displayed partial seizures,

and generalized seizures were infrequent. Epilepsies with both

generalized and focal seizures were rare and the four neonates

with both types of seizures had EIEE. Partial seizures were

observed in subjects with idiopathic and symptomatic epilepsies, whereas generalized seizures were present mainly in

those with EIEE and semilobar holoprosencephaly. Brief tonic

spasms were seen in the former and tonic seizures associated

with recruiting rhythms were observed in the latter. In contrast,

almost all occasional seizures were partial seizures and tonic

spasms were not present (Watanabe 1993).

BFNC is classified as generalized epilepsy in the current

International Classification, but ictal EEGs of their seizures

have been well documented in a few cases (Giroud et al.

1989, Wakai et al.1990, Andrew and Stafstrom 1993, Hirsh et

al. 1993, Mori et al. 1993, Ronen et al. 1993, Bye 1994).

Twelve of 16 neonates, including our subjects (eight infants),

in whom ictal EEGs were recorded, had partial seizures and

four had generalized seizures. Seven of our eight subjects

demonstrated partial seizures and one was considered to

have generalized seizures, even though their ictal EEGs were

not typical of generalized seizures of older children and

adults, because of no paroxysmal discharges of clearly focal

onset. Wakai et al. (1990) described more typical generalized

tonicclonic convulsions in a 4-month-old infant with BFNC

who had recurrences of seizures at 3 and 4 months of age. In

most families with BFNC, linkage to chromosome 20q has

been reported (Malafosse et al. 1992), but there seems to be

genetic heterogeneity (Ryan et al. 1991, Schiffmann et al.

1991) and the existence of a second locus on chromosome

8q (Steinlein et al. 1995) and an as yet unidentified third

locus has been suggested (Lewis et al. 1996). It remains to be

elucidated whether this genetic difference is reflected by the

difference in seizure types.

Benign neonatal convulsions (BNC) are also classified as

generalized epilepsy in the International Classification. But

most of the reported cases in which seizures were recorded

demonstrated localized paroxysmal discharges. All of our 16

subjects with BNC demonstrated partial seizures. Two infants

with BNC recently reported by Alfonso et al. (1997) showed

generalized attenuation of the background activity, followed

by focal onset paroxysmal discharges in association with bilateral tonicclonic seizures. Initial generalized voltage attenuation is also observed in partial epilepsy of older children and

adults. Thus, they may be considered partial seizures,

because the following discharges are clearly focal. This syndrome should be classified as localization-related epilepsy.

Infants with BFNC may have a recurrence of seizures

beyond the neonatal period. Approximately 10% of patients

had subsequent epileptic seizures in infancy, childhood, or

adolescence (Plouin 1992). Two of our eight infants with

BFNC had seizures in infancy and early childhood, which

were easily controlled. In BNC, a recurrence of seizures has

been reported to be low (Miles and Holmes 1990), but three

of our 16 patients with BNC had a recurrence of seizures,

although the type of subsequent epileptic seizures is

unknown. Gonzalez Ipina et al. (1996) observed central temporal rolandic EEG foci in a few patients with BFNC or BNC

and suggested a possibility of common genetic factors with

benign rolandic epilepsy. BNC may be a heterogenous condition and a long-term follow-up study is necessary to confirm

its benignity and its nature.

EIEE is classified into symptomatic generalized epilepsy in

the International Classification (Commission 1989). The

presence of tonic spasms is indispensable for the diagnosis,

although partial motor seizures may occur (Ohtahara et al.

1992). Five of eight patients under study had tonic spasms,

and three had partial seizures in addition to tonic spasms in

the neonatal period. This syndrome often evolves into West

syndrome and then to LennoxGastaut syndrome. This has

led to the concept of age-dependent epileptic encephalopathy, but other evolutionary changes can occur. Two of our

eight infants with EIEE eventually developed localizationrelated epilepsy with or without passing through the period

of West syndrome. Ohtahara et al. (1992) reported that eight

of 15 patients eventually had focal spikes with or without

passing through the period of hypsarrhythmia. We examined

a child with this syndrome in which suppressionburst patterns were replaced by continuous background EEG with

spindles displaying only focal spikes, which then evolved

into multifocal spikes and then to hypsarrhythmia (Watanabe

et al. 1987). This may contradict the notion that EIEE may be

West syndrome with an early onset (Lombroso 1990).

EME is also categorized as symptomatic generalized

epilepsy in the International Classification. It is characterized

by partial or fragmentary erratic myoclonus, massive myoclonia, partial motor seizures, and suppressionburst pattern on

EEG (Aicardi 1992). The infants under study did not demonstrate generalized seizures and showed only partial seizures

in addition to erratic myoclonia during the neonatal period,

and continued to show partial seizures thereafter. This syndrome may not necessarily be placed under the category of

generalized epilepsy, although some patients with this syndrome may develop West syndrome transiently.

Neonatal epilepsy with rhythmic alpha/theta activity is characterized by a peculiar EEG consisting of high-amplitude rhythmic alpha/theta activity, which is continuous during

wakefulness and becomes discontinuous during sleep, tonic

seizures associated with desynchronization, and recruiting

rhythm followed by oral automatism associated with slow

waves (Watanabe et al. 1976). This is typically seen in neonates

with semilober holoprosencephaly. In alobar holoprosencephaly, rhythmic alpha/theta activity is present only in anterior

regions. In such cases, seizure types are difficult to determine

due to the absence of the brain in posterior regions, although

they were provisionally classified into partial seizures by definition. Continuous high-voltage rhythmic alpha/theta/delta activities are also observed in other cortical dysplasia such as type I

lissencephaly, but are not usually observed in the neonatal

period (Dalla Bernardina et al. 1996). Moreover, they do not

show asynchronous discontinuity in sleep and have no anteriorposterior voltage gradient.

The International Classification classifies neonatal

seizures into undetermined epilepsies with both generalized

and focal seizures. But in this study, only three patients with

EIEE had both generalized and partial seizures in the neonatal period. Therefore, epilepsy with both generalized and

focal seizures is rather exceptional in neonatal epilepsies.

In our present study, seven infants were diagnosed as having cryptogenic epilepsy. They had no evidence of underlying disorders and exhibited normal or mildly delayed

psychomotor development, despite the presence of

intractable partial seizures. They seemed to have idiopathic

epilepsy because of the absence of any apparent cerebral

lesions or definite developmental retardation, but the refractoriness of their seizures suggests the presence of latent

minor cerebral lesions that could not be detected by existing

neuroimaging studies. The presence of such cryptogenic

localization-related epilepsy of neonatal onset has been

described by Natsume et al. (1996). Our subjects and those

studied by Natsume continued having partial seizures without evolutionary changes of epileptic syndromes.

Epilepsy of Neonatal Onset Kazuyoshi Watanabe et al. 321

The concept of age-dependent epileptic encephalopathy

has been applied to EIEE, West, and LennoxGastaut syndromes (Yamatogi and Ohtahara 1981). However, such evolutionary changes of epileptic syndromes are not restricted

to these syndromes but are also observed in other syndromes. As shown in this study, newborn infants with symptomatic epilepsy other than EIEE, EME, and semilobar

holoprosencephaly are particularly prone to localizationrelated epilepsy, and are likely to develop West syndrome

transiently in infancy. Thereafter, they may have localizationrelated epilepsy again or develop LennoxGastaut syndrome

depending upon the extent of brain damage. Symptomatic

localization-related epilepsy with transient West syndrome is

another type of age-dependent epileptic syndrome.

Accepted for publication 19th January 1999.

References

Aicardi J. (1992) Early myoclonic encephalopathy (neonatal

myoclonic encephalopathy) In: Roger J, Bureau M, Dravet Ch,

Dreifuss FE, Perret A, Wolf P, editors. Epileptic Syndromes in

Infancy, Childhood and Adolescence. 2nd ed. London: John

Libbey. p 1323.

Alfonso I, Hahn JS, Papazian O, Martinez YL, Reyes MA, Aicardi J.

(1997) Bilateral tonic-clonic epileptic seizures in non-benign

familial neonatal convulsions. Pediatric Neurology 16: 24951.

Andrew PI, Stafstrom CE.(1993) Ictal EEG findings in an infant with

benign familial neonatal convulsions. Journal of Epilepsy 6: 1749.

Aso K, Watanabe K. (1992) Benign familial neonatal convulsions:

generalized epilepsy? Pediatric Neurology 8: 2268.

Bye AM. (1994) Neonate with benign familial neonatal convulsions:

recorded generalized and focal seizures. Pediatric Neurology

10: 1645.

Clancy RR, Legido A. (1991) Postnatal epilepsy after EEG-confirmed

neonatal seizures. Epilepsia 32: 6976.

Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International

League Against Epilepsy. (1981) Proposal for revised clinical and

electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures.

Epilepsia 22: 489501.

Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International

League Against Epilepsy. (1989) Revised classification of

epilepsies, epileptic syndromes and related disorders. Epilepsia

30: 38999.

Dalla Bernardina B, Perez-Jimenez A, Fontana E, Colamaria V, Piardi

F, Avesani E, Santorum E, Grimau-Merino R, Tassinari CA. (1996)

Electroencephalographic findings associated with cortical

dysplasia. In: Guerrini R, Andermann F, Canapicchi R, Roger J,

Zifkin BG, Pfanner P, editors. Dysplasia of Cerebral Cortex and

Epilepsy. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven. p 135245.

Giroud M, Soichot P, Nivelon-Chevalier A, Gouyon JB. (1989) Les

convulsions neonatales familiales. Leur aspects electrocliniques

et genetiques. Neurophysiologie Clinique 19: 4754.

Gonzalez Ipina M, Roche Herrero MC, Lopez Martin V, Hawkins

Carranzo F, Sanchez Purificacion MT, Pascual-Castroviejo I.

(1996) Benign neonatal convulsions. Review of 23 cases (in

Spanish). Neurologia 11: 515.

Hirsch E, Velez A, Malafosse A, Marescaux C. (1993) Electroclinical

symptoms of benign familial neonatal convulsions. Epilepsia 34:

(Suppl.) 1801.

Lewis TB, Shevell MI, Andermann E, Ryan SG, Leach RJ.(1996)

Evidence of a third locus for benign familial convulsions. Journal

of Child Neurology 11: 2114.

Lombroso CT. (1990) Early myoclonic encephalopathy, early

infantile epileptic encephalopathy, and benign and severe

infantile myoclonic epilepsies: a critical review and personal

contributions. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology 7: 380408.

(1996) Neonatal seizures: a clinicians overview. Brain and

Development 18: 128.

Malafosse A, Leboyer M, Dulac O, Navelet Y, Plouin P, Beck C, Laklou

H, Mouchinino G, Grandscene P, Vallee L, et al. (1992)

Confirmation of linkage of benign familial neonatal convulsions

to D20S19 and D20S20. Human Genetics 89: 548.

322

Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 1999, 41: 318322

Miles DK, Holmes GL. (1990) Benign neonatal seizures. Journal of

Clinical Neurophysiology 7: 369379.

Miura K, Watanabe K, Aso K, Hayakawa F, Takeuchi T, Matsumoto A,

Kumagai T, Negoro T, Kaga Y, Kito M, et al. (1993) Epilepsies of

neonatal onset. Japanese Journal of Psychiatry and Neurology

47: 3479.

Mizrahi EM, Kellaway P. (1987) Characterization and classification of

neonatal seizures. Neurology 37: 183744.

Mori K, Yano I, Hashimoto T. (1993) Infantile spasms in one

member of a family with benign familial neonatal convulsions.

Epilepsia 34: 6216.

Natsume J, Watanabe K, Negro T, Aso K, Kasai K, Maeda N, Ohki T,

Horiuchi K. (1996) Cryptogenic localization-related epilepsy of

neonatal onset. Seizure 5: 3179.

Ohtahara S, Ohtsuka Y, Yamatogi Y, Oka E, Inoue H.(1992) Earlyinfantile epileptic encephalopathy with suppression-bursts. In:

Roger J, Bureau M, Dravet CH, Dreifuss FE, Perret A, Wolf P,

editors. Epileptic Syndromes in infancy, Childhood and

Adolescence. 2nd ed. London: John Libbey. p 2534.

Ohtsuka Y, Ogino T, Murakami N, Mimaki N, Kobayashi K, Ohtahara S.

(1986) Developmental aspects of epilepsy with special reference

to age-dependent epileptic encephalopathy. Japanese Journal of

Psychiatry and Neurology 40: 30713.

Plouin P. (1992) Benign idiopathic neonatal convulsions (familial and

non-familial). In: Roger J, Bureau M, Dravet Ch, Dreifuss FE, Perret

A, Wolf P, editors. Epileptic Syndromes in Infancy, Childhood and

Adolescence. 2nd ed. London: John Libbey. p 311.

Ronen GM, Rosales TO, Connolly M, Anderson VE, Leppert M.

(1993) Seizure characteristics in chromosome 20 benign familial

neonatal convulsions. Neurology 43: 135560.

Ryan S, Wiznitzer M, Hollman C, Torres MC, Szekeresova M,

Schneider S.(1991) Benign familial neonatal convulsions:

evidence for clinical and genetic heterogeneity. Annales of

Neurology 29: 46973.

Schiffmann R, Shapira Y, Ryan S. (1991) An autosomal recessive

form of benign familial neonatal seizures. Clinical Genetics

40: 46770.

Steinlein O, Schuster V, Fischer C, Haussler M. (1995) Benign

familial neonatal convulsions: confirmation of genetic

heterogeneity and further evidence for a second locus on

chromosome 8q. Human Genetics 95: 4115.

Wakai S, Tachi N, Ishikawa Y, Okabe M, Minami R, Kibayashi M.

(1990) Benign familial neonatal convulsion: clinical features of

the propositus and comparison with the previously reported

cases (in Japanese). No to Hattatsu 22: 58995.

Watanabe K. (1981) Seizures in the newborn and young infants.

Folia Psychiatrica et Neurologica Japonica 35: 27580.

(1993) Epilepsies in infancy. Japanese Journal of Psychiatry and

Neurology 47: 1657.

Hara K, Iwase K. (1976) The evolution of neurophysiological

features in holoprosencephaly. Neuropadiatrie 7: 1941.

Miyazaki S, Hakamada S. (1982a) Neurophysiological study of

newborns with hypocalcemia. Neuropediatrics 13: 348.

Kuroyanagi M, Hara K, Miyazaki S. (1982b) Neonatal seizures and

subsequent epilepsy. Brain and Development 4: 3416.

Takeuchi T, Hakamada S, Hayakawa F. (1987) Neurophysiological

and neuroradiological features preceding infantile spasms. Brain

and Development 9: 3919.

Yamatogi Y, Ohtahara S. (1981) Age-dependent epileptic

encephalopathy: a longitudinal study. Folia Psychiatrica et

Neurologica Japonica 35: 32131.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Evaluation and Management of The First Seizure in Adults - UpToDate PDFDokumen36 halamanEvaluation and Management of The First Seizure in Adults - UpToDate PDFSarah Camacho PinedaBelum ada peringkat

- Hubungan Antara Dukungan Keluarga Dan Motivasi Melakukan Rom Pada Pasien Pasca Stroke Siti NuryantiDokumen10 halamanHubungan Antara Dukungan Keluarga Dan Motivasi Melakukan Rom Pada Pasien Pasca Stroke Siti NuryantifenyBelum ada peringkat

- Toilet Training: Methods, Parental Expectations and Associated DysfunctionsDokumen9 halamanToilet Training: Methods, Parental Expectations and Associated DysfunctionsAsri RachmawatiBelum ada peringkat

- Helicobacter Pylori: A Review of Diagnosis, Treatment, and Methods To Detect EradicationDokumen13 halamanHelicobacter Pylori: A Review of Diagnosis, Treatment, and Methods To Detect EradicationAsri RachmawatiBelum ada peringkat

- Stool Antigen Tests in The Diagnosis of Infection Before and After Eradication TherapyDokumen5 halamanStool Antigen Tests in The Diagnosis of Infection Before and After Eradication TherapyAsri RachmawatiBelum ada peringkat

- Helicobacter Pylori Stool Antigen TestDokumen4 halamanHelicobacter Pylori Stool Antigen TestAsri RachmawatiBelum ada peringkat

- Oamjms 2015 062Dokumen4 halamanOamjms 2015 062Asri RachmawatiBelum ada peringkat

- Interpreting AV (Heart) Blocks: Breaking Down The Mystery: 2 Contact HoursDokumen29 halamanInterpreting AV (Heart) Blocks: Breaking Down The Mystery: 2 Contact HoursAsri RachmawatiBelum ada peringkat

- Tuberculosis: Challenging The Gold Rifampin Drug Resistance Tests ForDokumen9 halamanTuberculosis: Challenging The Gold Rifampin Drug Resistance Tests ForAsri RachmawatiBelum ada peringkat

- Articles: BackgroundDokumen6 halamanArticles: BackgroundAsri RachmawatiBelum ada peringkat

- 86 FullDokumen8 halaman86 FullAsri RachmawatiBelum ada peringkat

- Sclerema NeonatorumDokumen8 halamanSclerema NeonatorumAsri RachmawatiBelum ada peringkat

- Celulas Madres Cerebro HIDokumen10 halamanCelulas Madres Cerebro HIAsri RachmawatiBelum ada peringkat

- Disruptions Result From Destruction of A NorDokumen6 halamanDisruptions Result From Destruction of A NorAsri RachmawatiBelum ada peringkat

- Efficacy of Single-Dose Intravenous Immunoglobulin Administration For Severe Sepsis and Septic ShockDokumen7 halamanEfficacy of Single-Dose Intravenous Immunoglobulin Administration For Severe Sepsis and Septic ShockAsri RachmawatiBelum ada peringkat

- Febrile Seizures A. Gupta 2016 Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016 22 (1) 51-59Dokumen9 halamanFebrile Seizures A. Gupta 2016 Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016 22 (1) 51-59Jose Fernando DiezBelum ada peringkat

- Febrile Seizure CPGDokumen7 halamanFebrile Seizure CPGLM N/ABelum ada peringkat

- Epilepsy PDFDokumen15 halamanEpilepsy PDFMohamedErrmaliBelum ada peringkat

- Digital IEC Material - Epilepsy BrochureDokumen3 halamanDigital IEC Material - Epilepsy BrochureRheal P EsmailBelum ada peringkat

- Treatment and Prognosis of Febrile Seizures - UpToDateDokumen14 halamanTreatment and Prognosis of Febrile Seizures - UpToDateDinointernosBelum ada peringkat

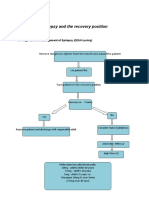

- Epilepsy Recovery Period - Second YrDokumen3 halamanEpilepsy Recovery Period - Second YrBrian MaloneyBelum ada peringkat

- Epilepsia - 2005 - Knudsen - Febrile Seizures Treatment and PrognosisDokumen8 halamanEpilepsia - 2005 - Knudsen - Febrile Seizures Treatment and PrognosisJanina MaligayaBelum ada peringkat

- Central Nervous System (CNS) Pharmacology (PCL 401) Antiepileptic/Anticonvulsants DrugsDokumen33 halamanCentral Nervous System (CNS) Pharmacology (PCL 401) Antiepileptic/Anticonvulsants DrugsJoseph JohnBelum ada peringkat

- Eeg For Pediatric ResidentsDokumen45 halamanEeg For Pediatric ResidentsChindia Bunga100% (1)

- Seizure Disorders in Children 2014 FCM LectureDokumen47 halamanSeizure Disorders in Children 2014 FCM LectureSven OrdanzaBelum ada peringkat

- RoPE Score CalculatorDokumen1 halamanRoPE Score CalculatorEliza PopaBelum ada peringkat

- Clinician Ep Onset eDokumen2 halamanClinician Ep Onset eInga CebotariBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation and Management of Status Epilepticus in ChildrenDokumen13 halamanEvaluation and Management of Status Epilepticus in ChildrenAyan BiswasBelum ada peringkat

- McqepilipsyDokumen3 halamanMcqepilipsyNguyen Anh TuanBelum ada peringkat

- Seizure Disorders in ChildrenDokumen22 halamanSeizure Disorders in ChildrenBheru LalBelum ada peringkat

- Hang Tuah Medical Journal: Research ArtikelDokumen9 halamanHang Tuah Medical Journal: Research ArtikelMaymay DamayBelum ada peringkat

- List Pasien NS Ruangan 2.6.21Dokumen4 halamanList Pasien NS Ruangan 2.6.21DICKY PANDUWINATABelum ada peringkat

- Quero L Pascual 2007Dokumen8 halamanQuero L Pascual 2007Donald CabreraBelum ada peringkat

- Are We Prepared To Detect Subtle and Nonconvulsive Status Epilepticus in Critically Ill Patients?Dokumen7 halamanAre We Prepared To Detect Subtle and Nonconvulsive Status Epilepticus in Critically Ill Patients?succa07Belum ada peringkat

- 47 NiceDokumen8 halaman47 NiceDHIVYABelum ada peringkat

- Absence Seizures Involve BriefDokumen4 halamanAbsence Seizures Involve BriefsakuraleeshaoranBelum ada peringkat

- Todd Paralysis (Wikipedia)Dokumen3 halamanTodd Paralysis (Wikipedia)AudioBhaskara TitalessyBelum ada peringkat

- Seizure: Health Education HFT 201 By: Sophia Kol, MDDokumen12 halamanSeizure: Health Education HFT 201 By: Sophia Kol, MDTith SeavmeyBelum ada peringkat

- DNF 360 Extended Manual FinalDokumen19 halamanDNF 360 Extended Manual FinalmisogenesisBelum ada peringkat

- Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game-Induced Seizures - A Neglected Health Problem in Internet AddictionDokumen6 halamanMassively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game-Induced Seizures - A Neglected Health Problem in Internet AddictionMuhammed AlmuhannaBelum ada peringkat

- Absence Seizure - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDokumen8 halamanAbsence Seizure - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfBlue PoopBelum ada peringkat

- Epilepsy Presentation Jo Wykes 2Dokumen27 halamanEpilepsy Presentation Jo Wykes 2Sana SajidBelum ada peringkat

- Types of SeizuresDokumen3 halamanTypes of SeizuresOliver FullenteBelum ada peringkat