Treating Depression in Prison Nursing Home

Diunggah oleh

Andreea NicolaeJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Treating Depression in Prison Nursing Home

Diunggah oleh

Andreea NicolaeHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Clinical

Case Studies

http://ccs.sagepub.com/

Treating Depression in the Prison Nursing Home : Demonstrating

Research-to-Practice Translation

Suzanne Meeks, Robin Sublett, Irene Kostiwa, James R. Rodgers and Donna Haddix

Clinical Case Studies 2008 7: 555 originally published online 25 July 2008

DOI: 10.1177/1534650108321303

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://ccs.sagepub.com/content/7/6/555

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Clinical Case Studies can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://ccs.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://ccs.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://ccs.sagepub.com/content/7/6/555.refs.html

>> Version of Record - Nov 10, 2008

Proof - Jul 25, 2008

What is This?

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Treating Depression in the Prison

Nursing Home

Clinical Case Studies

Volume 7 Number 6

December 2008 555-574

2008 Sage Publications

10.1177/1534650108321303

http://ccs.sagepub.com

hosted at

http://online.sagepub.com

Demonstrating Research-to-Practice

Translation

Suzanne Meeks

University of Louisville

Robin Sublett

Kentucky State Reformatory

Irene Kostiwa

James R. Rodgers

University of Louisville

Donna Haddix

Kentucky State Reformatory

We describe a theoretically grounded and empirically developed intervention for depression with

older men in a state reformatory nursing home. As the number of prisoners aging in place rises,

there is a critical need for research on mental health interventions in prison nursing homes where

inmates may be at high risk for depression and suicide. The participants in this project were four

male residents in the Kentucky state prison system nursing home; all four had diagnoses of major

depressive episodes. BE-ACTIV, a behavioral treatment for depression, is a hybrid approach that

combines one-to-one sessions with the depressed resident and work with staff. One-to-one sessions motivate the resident to engage in new activities, while meetings with nursing home staff

break down barriers to completion of pleasant events. Over the 10-week treatment, depressive

symptoms declined, and global functioning increased an average of 13 points per participant. Two

of the participants showed improved self-reported negative affect. Study results suggest that

BE-ACTIV is feasible in the prison nursing home and has the potential to improve the quality of

life for medically frail prisoners by helping them to identify meaningful or pleasant activities. The

cases illustrate importance of therapeutic relationships in the context of improving depressive

symptoms, and the possibility of building effective relationships in a setting with multiple barriers to effective treatment.

Keywords:

nursing homes; prisoners; depression; treatment

1 Theoretical and Research Basis

In this case study, we describe the application of a theoretically grounded and empirically developed intervention for depression to a specific population of older adults: older

men in a state reformatory nursing home. In recent years, researchers and funding agencies

555

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

556

Clinical Case Studies

have increasingly recognized the importance of translating research findings to clinical

settings as critical to the vitality and utility of any clinical science (e.g., National Institutes

of Health [NIH], 2007; Vernig, 2007). From the perspective of funding agencies, such

translation ensures that investment in scientific research results in advancements in direct

patient care; from the perspective of researchers, working in clinical settings stimulates new

research questions and enables real-world tests of theoretical models. The evidence-based

treatment movement encourages use of empirically tested interventions in practice settings,

but often the process of developing evidence-based treatments does not address the many

barriers to translating those treatments to varied practice settings. Older adults in particular

enter mental health treatment through a variety of settings that ranges from traditional mental health venues and outpatient medical practices to long-term care settings, such as

assisted living and nursing homes. Each of these settings presents novel challenges to treatment delivery that must be tested and overcome if treatments are to be widely available.

This study is part of a larger program of research for developing and testing the BE-ACTIV

intervention specifically designed for nursing home clients. This small demonstration project came about following an inquiry by the second author regarding whether BE-ACTIV

might be applicable to the prison nursing home setting. A demonstration of this nature not

only provides information to meet site-specific clinical needs, but also adds to the foundation of ecological validation for a treatment approach.

Mental Health Needs Among Older Prisoners

Despite the fact that the elderly appear to be a rapidly growing segment of the prison

population in the United States and other countries, there is relatively little work done to

date addressing the mental health issues related to aging in place in prisons. The general

population of prisoners in federal, state, and private facilities grew 28% between 1995 and

2000 (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2003), but although elderly prisoners are still a minority

of the corrections population, the rate of older prisoners is growing at a much higher rate

(Aday, 1994). Little is known about these older prisoners; we found only a 1983 review of

federal data, case reports, and other nonresearch reports compiled by Goetting describing

this population. Her review indicated that the majority of elderly prisoners were men with

multiple incarcerations who were likely to have histories of violence.

Data from the Bureau of Prison Statistics suggest that the rate of mental illness among

prisoners is very high, with approximately half reporting symptoms (James & Glaze,

2006). Most symptoms were related to mood disorders. Prisoners with mental illness were

at higher risk than other prisoners for injury and victimization, as well as for longer prison

stays. Although rates of mental illness diminished with age, the percentage for older adults

remained significantly higher than for elders outside of prison. In one of the few epidemiological studies of psychiatric morbidity in prisons, Fazel, Hope, ODonnell, and Jacoby

(2001) surveyed 203 men over the age of 60 in 15 British prisons with populations of at

least 10 older prisoners. Diagnoses were determined by structured psychiatric interviews.

Approximately one third of the sample had Axis I diagnoses from the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.) (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric

Association, 1994), and nearly all of these had diagnoses of a depressive disorder. Risk for

depressive disorder was related to medical condition, similar to other populations of older

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Meeks et al. / Treating Depression in the Prison Nursing Home

557

adults that have been studied, but because the overall risk was much higher than for community-residing elders, it seems likely that older prisoners in nursing homes are at particular risk for depressive illness. When treatment needs of this same sample were examined,

it appeared that depressive disorders were medically undertreated (Fazel, Hope, ODonnell,

& Jacoby, 2004). Prisoners of all ages with mental illnesses are at risk for suicidal behavior (Senior et al., 2007), and suicide risk is correlated with age. Prisoners who have been in

prison longer are at higher risk for suicide (Konrad et al., 2007). In their comparison of

British prisoners with and without charted suicide risk, Senior and colleagues (2007) found

that those at risk had higher unmet support needs in the areas of safety, psychological

distress, and daily activities.

In their 2005 review of research on mental disorders in prison, Fazel and Lubbe conclude

that although epidemiological work and work on attention to interventions for violent

behaviors constitute a starting point, there is a critical need for research into what interventions can be effectively implemented in prison settings. There is some evidence that

prisoners do receive antidepressant medication (Baillargeon, Black, Contreras, Grady, &

Pulvino, 2002), although approximately 20% of prisoners diagnosed with major depression

did not receive antidepressants in this study, and there were gender, racial, and ethnic disparities in who received antidepressants and what type of antidepressants were prescribed.

Most state prisons, and all federal prisons, offer psychological and psychiatric services

(Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2003). Although some therapists have written about treating

prisoners (e.g., Pollock, Stowell-Smith, & Gpfert, 2006; Saunders, 2001), there is virtually no research on mental health interventions for this population, and the effectiveness of

interventions used with prisoners, particularly older prisoners, is unknown.

The BE-ACTIV Program for Depression in Nursing Homes

The BE-ACTIV program has been described in two previous publications (Meeks,

Looney, Van Haitsma, & Teri, 2008; Meeks, Teri, Van Haitsma, & Looney, 2006), and the

conceptual basis was described in a third article (Meeks & Depp, 2002). Briefly,

BE-ACTIV is a behavioral treatment that derives from the work of Lewinsohn and his colleagues (Lewinsohn, Hoberman, Teri, & Hautzinger, 1985). In this work, the central feature of depression is the combination of reduced positive reinforcement and positive impact

that arise in the context of disrupted routine, loss of control, and stress. The primary goal

of treatment is to interrupt the cycle of high negative affect and low positivity by systematically increasing opportunities for positive reinforcement. Empirical support for an activity-related intervention in nursing homes comes from a body of evidence accumulated by

Lawton and his colleagues (e.g., Lawton, 1997) that links resident activity level, affective

tone of activities, and levels of positive and negative affect to depression. This research

strongly suggests that participation in activities perceived as positive should be an important focus for intervention.

BE-ACTIV was adapted from a manualized treatment for depression in cognitively

impaired elders, developed and tested by Teri and colleagues (Teri, 1994, 1997; Teri,

Logston, & Uomoto, 1991; Teri, Logsdon, Uomoto, & Curry, 1997). Their research demonstrated that a behavioral intervention can be used successfully with impaired elders, and that

caregivers can learn to collaborate in increasing pleasant events and producing successful

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

558

Clinical Case Studies

outcomes for the elders they care for. Our preliminary work adapting this intervention to

the nursing home setting is summarized in two previous articles (Meeks et al., 2006; Meeks

et al., 2008). In place of family caregivers, BE-ACTIV requires that the therapist form a

working relationship with the activities staff of the nursing facility. This hybrid approach

to mental health care involves a combination of one-to-one sessions with the depressed resident and involvement of staff in implementing the plan for increasing pleasant events. Oneto-one sessions serve to motivate the resident to engage in new activities, while meetings

with nursing home staff help to break down barriers to the implementation of pleasant

events. In the pilot work, BE-ACTIV shows promise of improving depressive diagnoses,

increasing positive affect, and increasing activity levels of nursing home residents as compared to residents randomly assigned to treatment as usual (Meeks et al., 2008). Given that

prisoners in a correctional nursing home environment are at high risk for depression and suicide, and the prison environment affords few opportunities for pleasant daily activities, it

seems logical that BE-ACTIV could be a useful intervention for that setting.

2 Case Presentation

The participants in this demonstration project were four male prisoners who were residents in the nursing facility for the Kentucky state prison system. The participants volunteered to participate as part of a research project; the chief psychologist of the nursing

facility identified all residents who were presenting with depressed mood, had diagnoses of

depression, or were being treated with antidepressants. Of the 78 inmates on the unit, the

chief psychologist identified approximately 46 as potentially eligible (meeting criteria for

a depressive disorder and having a Mini-Mental Status Exam [MMSE] score of 14 or

above). Of these, 21 consented to screening, but only 6 were found to meet criteria for the

study after the initial research assessment. One of these men was transferred off the unit

and another died before they could receive the intervention; we completed the intervention

with the other four.

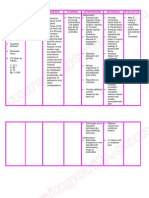

Table 1 shows the ages, race, and diagnostic status of the participants at baseline assessment. The youngest participant was 47,1 the oldest was 81, but they all had considerable

medical morbidity and all but one had some mild cognitive impairment. After baseline

assessment, they received weekly sessions of BE-ACTIV for 10 weeks, with a follow-up

assessment at the end of the 10 weeks. The therapists were two doctoral students in clinical psychology, one male and one female, with prior clinical experience in both inpatient

and nursing home settings, but with no prior experience in forensic settings. The staff member who collaborated in the treatment was a female recreational therapist assigned to the

nursing unit for several hours per week. Prior to her participation, she received a 3-hr

in-service training by the first author about the BE-ACTIV program, depression in general,

and her role in implementing pleasant events (see Meeks & Burton, 2004).

The prison nursing unit is configured more like a nursing home than a prison ward, with

a centrally located nursing station, semiprivate rooms, a mess hall, and a lounge area with

a TV. There is also a fenced, secure, outdoor patio with a small garden. Inmates of the nursing home are generally not allowed to be on the yard with the general prison population.

Recreational activities are usually held in the mess hall. Weekly sessions were held either

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Meeks et al. / Treating Depression in the Prison Nursing Home

559

Table 1

Participant Baseline Characteristics

Age

Race

DSM-IV diagnosis

GAF

GDS

MMSE

COOP

Positive affecta

Negative affecta

Mr. A

Mr. B

61

African

American

MDD recurrent,

in partial

remission

47

African

American

Bipolar disorder,

current episode

MDE, severe,

without psychotic

features

53

21

29

10

14

10

60

18

24

7

5

10

Mr. C

Mr. D

58

White

81

White

MDD recurrent, in

partial remission

MDD, single

episode, severe,

without psychotic

features

53

25

26

8

14

15

45

22

23

13

9

20

Note: COOP, Dartmouth COOP Scales of Functioning; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disordersfourth edition; GAF, global assessment of functioning; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; MDD,

major depressive disorder; MDE, major depressive episode; MMSE, Mini-Mental Status Exam.

a. Positive and negative affect are sums of five items for baseline week.

in the residents room or in available office space on the nursing or psychiatric units. Care

was taken to optimize privacy but at times staff may have been within earshot of the shared

office space, or a roommate may have been present. During the 10 weeks of treatment,

therapists recorded weekly self-reported mood ratings, pleasant events, and the time that

the recreational therapist spent with the residents. The therapists completed diagnostic and

symptom assessments in the week following the tenth session for all except Mr. D, who was

in solitary confinement at the end of the treatment.

3 Presenting Complaints and History

All four participants were experiencing major depressive episodes (MDEs) at baseline,

two severe and two in partial remission (see Table 1). We deliberately did not request

information about the participants criminal background or convictions aside from the

length of time they had been incarcerated, choosing instead to treat depressive symptoms

in the context of the residents current situation. Individual presenting issues and history are

presented in the following paragraphs.

Mr. A

Mr. A was an African American male who had been in and out of the prison system in the

past and was incarcerated for a little more than a year at the time of the study because of a

violation of his parole. Staff reported that he was irritable, quiet, and withdrawn, rarely

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

560

Clinical Case Studies

participating in activities, spending much of his time in his room watching television or sleeping. He admitted that he had been hibernating because of ongoing worries about his health,

parole, and marriage. He also complained of nerves and said that he did not like being in

crowds or around other people, especially his fellow inmates. Mr. A reported having strained

relationships with most of his family members, although his aunt and cousin remained in contact with him. During the initial interview and early sessions, his speech was relatively quiet

and he appeared somewhat guarded in his responses. Mr. A was placed on the nursing unit following the loss of his leg resulting from poorly controlled diabetes mellitus and peripheral vascular disease. He had triple bypass surgery approximately 4 years prior to treatment. He

suffered a heart attack just a year before his incarceration, which he felt marked the beginning

of his current depressive episode. His health status and access to adequate health care were key

concerns for him; he feared dying in prison. Symptoms of depressed mood, weight gain,

insomnia, lack of energy, and difficulty concentrating endorsed at the initial interview contributed to a diagnosis of recurrent major depressive disorder (MDD) in partial remission.

Mr. B

Mr. B was an African American who had been incarcerated for 2 years. He was referred to

the program because staff members reported that he rarely spoke, did not attend activities, and

left his room only to eat or when instructed to do so. He would constantly lie in bed and watch

television even though only one TV channel was available to him. During the initial assessment, Mr. B was reserved and quiet, rarely making eye contact or speaking except to answer

direct questions. He stated that he didnt have much energy and that he felt really down

almost all of the time. His medical record included a diagnosis of schizophrenia, but based on

his endorsements on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID), he met criteria for

a history of mania and reported no psychosis outside of the context of affective episodes; so he

received the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, most recent episode depressed. His current episode

was rated as severe, but there was no evidence of current psychotic features. He agreed to participate in the project in hopes that he would feel better.

Mr. B stated that he felt that he had a normal childhood and had played football in high

school but that he always felt different than other people. He had no immediate family and

was divorced from his only wife. This was his second time in prison and he was determined

that his behavior would be such that he would be assured of parole at the earliest possible

opportunity. He reported that he had been moved to the prison nursing home to monitor and

care for his diabetes. Mr. B had many friends on the yard (in the general prison population),

and the move to the nursing home had isolated him from these friends because visits

between units required a special request sanction by the wardens office. Mr. B noted that

the larger rooms in the nursing facility were nice but that he missed his friends.

Mr. C

Mr. C was a white man who had been incarcerated for approximately 13 years. Staff suggested that he might be a good candidate for the study because of ongoing difficulties with

depressed mood, sleep disruption, and irritability. Despite these symptoms, Mr. C maximized

his daily routine by participating in available activities and remaining engaged with staff and

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Meeks et al. / Treating Depression in the Prison Nursing Home

561

fellow inmates. He embodied the essence of behavioral activation even before his participation

in the study, and often stated I have to stay busy and hinted of a looming deeper depression.

Mr. C related a history of severe depressive episodes and alcohol abuse that began in his late

20s; he had a history of at least one grave suicide attempt. Mr. C was on the nursing unit primarily because of visual impairment combined with other medical problems. During the

initial interview, he complained of visions of bright lights and images of arbitrary floating

objects, which interfered with his concentration during the day and prevented him from

obtaining restorative sleep at night. He said these obtrusive visions began subsequent to a surgical procedure on his eyes. During the initial interview, his symptoms of depressed mood,

weight gain, insomnia, fatigue, thoughts of death, and significant ongoing distress contributed

to a diagnosis of MDD in partial remission. Interpersonally, Mr. C was very pleasant and agreeable but was noted to have a low frustration tolerance. He became visibly irritated when discussing his lack of control in terms of an inability to accomplish certain tasks either because

of his blindness or because of the restrictive environment of the prison.

Mr. D

Mr. D was a white man who had served more than 30 years in the prison system. The

staff noted that Mr. D was not liked by other inmates on the unit and that his problematic

and often oppositional behavior made him difficult to treat. Mr. D showed signs of memory loss and his score on the MMSE was a 23, indicating significant cognitive impairment.

He was often incontinent and resisted attempts by the staff to help him with self-care.

Usually, such resistance was met by calling the prison guard who would order him to bathe

and change clothes on the threat of punishment involving solitary confinement and loss of

privileges. On the SCID, Mr. D met threshold for all major depression items, earning him

a diagnosis of MDE, severe, without psychotic features. He had no recollection of a prior

episode, nor were any documented in his medical record.

Mr. D reported that he was a self-taught engineer and that he designed heating and air conditioning systems. He had worked for many years in a supervisory position in the prison

mechanical shop and had been involved in training other prisoners in skilled trades that could

be useful in and out of the prison system. Mr. D noted that because of his prison jobs, he felt

that his life had been useful. He put a great deal of emphasis on his ability to do real work.

As his memory difficulties progressed he was gradually removed from the teaching positions

and then from the prison shop. Ultimately, (probably because of his cognitive decline) he was

placed in the prison nursing home where he spent his time occasionally watching TV, eating

food from the prison commissary, and sleeping. Because of the sale of his home and belongings following the death of his wife, Mr. D had some money in the bank; he believed that

other prisoners only talked to him so that they could borrow money or share in his food. He

did not have any positive social relationships with other inmates on the unit.

4 Assessment

Diagnoses were determined using a modified version of the SCID (First, Spitzer,

Gibbon, & Williams, 2002). Either the first author or one of the therapists administered the

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

562

Clinical Case Studies

SCID 2 weeks prior to the first therapy session, and then again in the week following session 10. Depressive symptoms were also assessed using the Geriatric Depression Scale

(GDS; Brink et al., 1982), a 30-item, self-report scale designed for use with older adults.

We also administered the MMSE (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) as a screen for cognitive impairment, and the Dartmouth COOP Scales of Functioning (Nelson, Wasson,

Johnson, & Hays, n.d.). The COOP chart method of assessing functional status was developed by the Dartmouth Primary Care Cooperative Information Project (COOP) to provide

researchers and clinicians with a quick but valid means to assess adult and adolescent functioning in primary care (Nelson et al., 1987). COOP charts used included interference with

daily activities, interference with social activities, health changes, and overall self-rated

health, yielding a functional impairment scale ranging from 4 to 25 with higher scores indicating higher impairment. Participants rated their mood weekly using the Philadelphia

Geriatric Center Positive and Negative Affect Rating Scale (PNAR; Lawton, Kleban, Dean,

Rajagopal, & Parmelee, 1992). The PNAR produces positive and negative affect scales

each with a possible range of 5-25. We obtained demographic information, medical diagnoses, and medications from the prison health records. Results of baseline assessments are

shown in Table 1.

During the first session of BE-ACTIV, the therapist completes the initial version of the

Pleasant Events ScheduleNursing Home Version (PES-NH; Meeks, Heuerman, Ramsey,

Welsh, & White, 2005). This instrument helps the therapist and resident identify potentially

pleasant events that could be incorporated into the residents daily routine. An activity staff

member is invited to attend these first sessions. In this project, the recreational therapist

was present at all four first sessions to help the therapists determine what activities were

feasible within the prison nursing home. The follow-up version of the PES-NH was used

weekly during the therapy sessions to determine the number and pleasantness of the mens

activities during the time between sessions.

5 Case Conceptualization

With the exception of Mr. C, each of these men presented with pronounced reduction in

daily activities and a sense of hopelessness about the possibility of engaging in any activities that might be pleasant. As a result of placement on the nursing unit, all the men had

experienced significant losses related to meaningful social contact, including opportunities

to interact with friends and relatives on the yard (A, B, and C), and the opportunity to

engage in meaningful work including teaching others (D). They also reported reduction in

opportunities for leisure activities such as access to a weight room and library, and loss of

control over the availability of supplies or materials such as books, newspapers, art supplies, or television stations. Thus, each was experiencing reduced opportunities for positive

affect, in combination with increasing experiences of negative affect related to increased

health problems and disability, worries about parole (for A and B), and family stressors (A

and C). Figure 1 depicts these circumstances within the context of the conceptual basis of

BE-ACTIV from the work of Lewinsohn and colleagues (Lewinsohn et al., 1985). The

shaded box indicates the primary target of the intervention to increase opportunities for, and

control over, pleasant events so that the participants will experience increased positive

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Meeks et al. / Treating Depression in the Prison Nursing Home

563

Figure 1

Conceptual Model of BE-ACTIV in the Prison Setting

Reduced opportunities for

social interaction and work

Loss of control over daily

activities

Increased negative affect

Antecedents:

Increased physical/cognitive

disability

Move to more restrictive

prison unit

Reduced positive

reinforcement

Reduced positive

affect

Increased negative

self-awareness

(negative cognitions)

Increased depression

(Persistent Dysphoria)

Vulnerabilities

Negative consequences

of Depression: Reduced

activity, negative

interpersonal interactions,

poorer health, more need

for care

affect. Note that although it is unavoidable that there will be some attention to reducing

negative affect and negative events associated therewith, this is not the focus of BE-ACTIV

because many sources of negative affect in nursing homes, and particularly in a prison nursing home, are unavoidable and largely immutable.

6 Course of Treatment and Assessment of Progress

Figure 2 shows increases in pleasant events for all participants over the course of therapy, with slight decreases apparent at therapy termination. Graphs of weekly mood ratings

(Figures 3-6) over the 12 weeks of the study suggest that the participants mood was unstable and highly reactive to environmental events, particularly at the beginning of the treatment period, but that as treatment progressed, around the fifth or sixth session, there was a

stabilization of negative affect for three out of four participants. The participants relationships with the staff recreational therapist showed both greater contact and greater trust over

the 10 weeks of treatment. Participants also reported a feeling of having more control over

their moods and choices of activities. Tables 1 and 2 show characteristics of the participants

at pre- and posttreatment assessments. These data suggest, contrary to our expectations,

that overall self-reported positive affect did not increase much over the course of treatment,

but that at least in the case of two of the participants, negative affect declined. Levels of

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

564

Clinical Case Studies

Table 2

Posttreatment Outcomes

Mr. A

DSM-IV diagnosis

MDD recurrent,

in partial

remission

GAF

GDS

MMSE

COOP

Positive affecta

Negative affecta

70

12

25

7

5

13

Mr. B

BPI, most recent

episode depressed,

in partial

remission

60

18

26

10

16

7

Mr. C

MDD recurrent,

in partial

remission

75

10

26

5

14

10

Mr. D

Unable to

complete

final

SCID

NA

NA

NA

NA

NA

NA

Note: See note to Table 1. NA, not available; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV.

a. Positive and negative affect are sums of the final week of therapy.

physical disability remained stable across the 10 weeks. Depressive symptoms declined for

all participants for whom we were able to assess outcomes, and global functioning

increased an average of 13 points per participant. Specific characteristics of treatment

course for the participants are summarized in the following paragraphs.

Course of Treatment for Mr. A

Gaining a sense of mastery over his daily routine appeared to be a major theme for

Mr. A over the course of therapy, who stated that his mood problems were a matter of control. Control issues might be expected in a prison setting where inmates have few choices,

but Mr. A in particular found great relief and pleasure in the notion that he had some control, even if it was in the smallest facet of his daily routine. At the beginning of therapy, his

attention was largely focused on his upcoming parole hearing. Any excitement or positive

feelings concerning his possible release were undermined by significant worry about

returning to the free world with an amputated leg, that his marriage was deteriorating, and

that his former home and life would no longer be available to him. Thus, during the first

several sessions, Mr. As negative affect increased significantly reflecting his ongoing anxiety about an upcoming parole hearing and intense disappointment and anger on denial of

parole. Despite his past tendency to withdraw and isolate in the face of such negative feelings, Mr. A identified and engaged in activities that he found pleasurable as a part of the

study. Mr. A was highly creative and found pleasure in reading stories, writing, painting,

and listening to music. He described in vivid detail the pleasure that he felt when painting

or taking a hot bath which involved a type of mental escape from the confines of the

prison and an overall sense of well-being. He drew a strong connection between his chosen

activities and these positive feelings, and he often framed this in terms of a renewed sense

of control. As a result, he became highly committed to participating in these activities, independently increased the frequency of his baths, and never missed an opportunity to paint.

When faced with divorce from his wife around the Session 7, rather than follow his past

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Meeks et al. / Treating Depression in the Prison Nursing Home

Figure 2

Change in Pleasant Activities (Frequency Pleasantness)

Over 12 Weeks for Each Prisoner

60.00

50.00

Frequency x pleasantness

40.00

30.00

20.00

10.00

0.00

Session1

Session 2

Session 3

Session 4

Session 5

Mr. A

Session 6

Mr. B

Session 7

Mr. C

Session 8

Session 9 Session 10

Mr. D

Figure 3

Change in Positive and Negative Affect Over 12 Weeks for Mr. A

4.50

4.00

3.50

3.00

2.50

2.00

1.50

1.00

B1

B2

T1

T2

T3

Mr. A Pos Affect

T4

T5

T6

T7

T8

Mr. A Neg Affect

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

T9

T10

565

566

Clinical Case Studies

Figure 4

Change in Positive and Negative Affect Over 12 Weeks for Mr. B

4.50

4.00

3.50

3.00

2.50

2.00

1.50

1.00

B1

B2

T1

T2

T3

T4

T5

Mr. D Pos Affect

T6

T7

T8

T9

T10

Mr. D Neg Affect

Figure 5

Change in Positive and Negative Affect Over 12 Weeks for Mr. C

4.50

4.00

3.50

3.00

2.50

2.00

1.50

1.00

B1

B2

T1

T2

T3

Mr. C Pos Affect

T4

T5

T6

T7

T8

Mr. C Neg Affect

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

T9

T10

Meeks et al. / Treating Depression in the Prison Nursing Home

567

Figure 6

Change in Positive and Negative Affect Over 12 Weeks for Mr. D

4.50

4.00

3.50

3.00

2.50

2.00

1.50

1.00

B1

B2

T1

T2

T3

Mr. B Pos Affect

T4

T5

T6

T7

T8

T9

T10

Mr. B Neg Affect

pattern of withdrawal, he continued to participate in activities and his negative affect

remained low. Nonetheless, as he felt better about himself, Mr. A also engaged in a pleasurable activity that had negative consequences for his health: eating sweets and high fat

snacks. With diabetes and cardiovascular problems, this increased snacking affected his

blood sugar and physical health. As he experienced physical discomfort, his worry about

his health and negative affect increased around Session 9. Despite the physical illness, he

continued to increase the frequency of his baths and also identified additional activities of

interest, such as writing a novel.

Course of Treatment for Mr. B

At baseline, Mr. B rarely participated in any activities or left his room. Figure 4 shows

that Mr. B experienced a relatively small range of both positive and negative affect. As the

intervention progressed, he found interests in numerous events including attending the regular Monday afternoon unit coffee, going to bingo games, taking a second weekly shower,

sitting outside, and listening to nature. Mr. B discovered an avid interest in listening to the

sounds of nature. During the sessions, he would describe in detail the appearance of the birds

that landed in the prison yard and would occasionally attempt to whistle like them. At the

conclusion of these exchanges, a rare smile would appear on his face. Toward the end of the

intervention, Mr. B was beginning to spend a small amount of time each day out on the patio

under a shady overhang attempting to hear whatever sounds were available including the

cows in the pasture beyond the wall, men working in the yard, and the blowing of the wind.

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

568

Clinical Case Studies

The weekly visit from the therapist appeared to become a pleasant event in itself. His

response to the therapist is evident in both activity level (Figure 2) and negative affect

(Figure 4). Mr. B noted that he looked forward to the meeting each week. Early in the

intervention, his compliance with planned activities seemed to be mainly the result of his

stated desire to fulfill the therapists requests, illustrating how the one-to-one relationship

can serve as a motivator to encourage depressed residents to try activities that they otherwise would not. As time progressed, the pleasure Mr. B gained from activity participation

appeared to become the impetus for his continued activity participation, even resulting in

participation in spontaneous activities such as talking to people on the unit, attending movie

night, and going outside more often than requested.

Course of Treatment for Mr. C

From the outset of the therapy, Mr. C emphasized his need to stay busy and engaged

in all available activities, except those that required vision, such as crafts, because of his

visual impairment. Rather than focusing on the enjoyment he received from these activities, however, he attributed his high level of engagement in activities and with others as an

avoidance of being alone in an empty room, where he believed he would inevitably focus

on his problems and become deeply depressed. Over the course of therapy, discussion of

activities as pleasant events and a source of positive affect appeared to help him derive

more satisfaction from the activities in which he already engaged. Identification of additional activities was challenging because he was so highly active, therefore much of the

work at baseline focused on increasing simple interactions with the staff and advocating for

his own needs. Like Mr. A, Mr. C expressed feelings of frustration regarding his lack of

control. For Mr. C this related to his inability to meet his own needs, in part because of his

visual impairment. He reported frustration regarding his unfulfilled requests of staff members. For example, he requested that his tape recorder be fixed so that he could listen to

books on tape, requested visits from his brother who was also an inmate but who resided

in the general population, and he requested that he be baptized. In the past, his requests

were largely passive, wherein he would ask once and then wait for it to be fulfilled. He

became quickly impatient when these things did not happen, and his negative feelings prevented him from further pursuing his needs. Thus, pleasant events identified at the beginning of the therapy involved interacting with staff and checking on the status of his

requests. Mr. C was generally very social in that he enjoyed talking to other inmates and to

staff. He was personable and appreciative of others, therefore the staff responded well to

him, further establishing these interactions as pleasant events. Thus, the activity of checking in with staff members helped him build better relationships and provided reminders to

staff about his needs, both of which gave him a sense of control. He often expressed his

genuine positive regard and respect for the recreational therapist, and in building this relationship, expressed a feeling of being supported, which he previously lacked. As a result of

his activity of checking in with staff regularly, he received a new tape recorder, received

approval for regularly scheduled visitation with his brother, and was baptized. Thus, his

interactions with staff led to further reinforcement via fulfillment of his requests, and in

turn an increase in other events, such as listening to books on tape and visiting with his

brother. A sharp increase in negative affect was noted in sessions 3 and 4, wherein Mr. C

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Meeks et al. / Treating Depression in the Prison Nursing Home

569

discussed frustrations with unfulfilled needs such as not being able to get his laundry done,

not finding a chair to sit in at church, and most importantly his worry about his brothers

legal issues. These setbacks were addressed by focusing Mr. C on those things that were

within his control, such as the activities that he scheduled and in which he engaged.

Course of Treatment for Mr. D

Because of his dementia, although Mr. D could remember the majority of activities in

which he participated he had difficulty remembering the affect associated with those activities. He often lived in the moment and would interpret the past in light of his present mood.

However, there were a few activities about which he would give account in great detail and

which seemed to supersede his mood-specific interpretation. He consistently perceived

social activities such as coffees and bingo as negative events and felt they were unworthy

of his time. The one exception was whenever the activities director would place a cookie in

his mouth during coffee. He would remember this with great pleasure and enjoyed recounting this event. He appeared to enjoy going outside but reported that he was too old to

stand the summer heat. Mr. D attached great importance to events or activities that he considered worth his time. Attending religious services fell into this category, not so much

for the religious content as for the musical content. Mr. D described himself as a former

musician and attending religious service with the accompanying music seemed to restore

the affect associated with his memories of those days. Prior to the intervention, he rarely

associated with other residents in a positive manner and rarely took part in any activities.

Near the end of his time in the study, there was a rare live musical concert and hamburger

cookout that produced a spike of positive affect for Mr. D (see T6 in Figure 6) because it

combined, food, going outside, and his love of music.

As with Mr. B, the weekly therapy meetings appeared to become a pleasant event for

Mr. D. He enjoyed and responded to one-on-one interactions with both the therapist and the

recreational therapist. Along with his determination of activity meaningfulness, this type of

interaction seemed to underlie his compliance with therapy and his willingness to participate in any activity. Despite his bitter skepticism about participating in anything meaningful, Mr. D made an effort seemingly just to please the therapists, and his positive affect

appears to have increased somewhat over the course of treatment. However, Mr. Ds cognitive decline within a prison nursing home setting significantly affected the outcome of his

treatment. As an example, on two occasions, Mr. D initially refused his scheduled sessions

because of incontinence and a lack of clean clothing. Prisoners are issued a uniform and if

the uniform becomes soiled it is sometimes difficult to acquire new clothing. This may be

because clothing is limited and the necessary articles may not be readily available or it

could be because the unit is understaffed and certified nursing assistants (CNAs) have other

more pressing duties. In the first instance, the therapist was able to resolve the issue by finding new clothing for Mr. D, and in the second instance, Mr. D agreed to continue therapy

within the confines of his room. The other issue brought about by Mr. Ds cognitive decline

was his behavioral infractions on the unit and with the staff. These were often combative

and sometimes viewed as vindictive. In a prison population, problematic behaviors may be

dealt with in a punitive fashion and according to accepted prison protocols and standards. In

Mr. Ds case, his behavioral infractions resulted in segregation from the prison population.

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

570

Clinical Case Studies

Segregation takes place in a small cell where the prisoner is kept for 23 hr per day, with little contact with others and only few possessions (Bender, 2005). Mr. D was in segregation

during the final week of treatment and was unable to have his final assessment or meeting

with his therapist, as it was expected that he would be there for some time.

7 Complicating Factors

Clearly, prison nursing homes have characteristics that pose unique barriers to successful treatment of and recovery from depressive disorders. Some of the barriers we encountered are shared with other nursing homes. For example, the recreational therapist had very

little access to or budget for supplies that might enhance activities such as art projects, reading, and movies. Frequently this lack of an activities budget is found in nursing homes in

the private sector as well, although not surprisingly we found the lack of supplies to be

more extreme in the correctional setting. The limited amount of time the recreational therapist could be on the unit was also a problem, and staff shortages are frequently found in

private sector nursing homes as well. Lack of a private place to hold therapy sessions is a

problem that frequently occurs in all nursing homes, but this is significantly more of an

issue in the prison because of security considerations. Such lack of privacy may, especially

in prisons, impede open communication between the therapist and the client, and therefore

limit the power of the therapy relationship to effect change through motivating the client.

Nevertheless, all four of these men appear to have developed good working relationships

with their therapists, and all commented on the importance of the visits to them and for

motivating them to try new activities.

As nursing home patients are typically medically at risk and struggle with multiple

chronic health problems, the threat of illness events may have an impact on fluctuations in

mood, therapy compliance, and outcomes. We saw this in the prison setting as well. Mr. A,

B, and C were younger than the average nursing home resident, but all three suffered from

multiple chronic illnesses and disabilities and were significantly impaired in their ability to

navigate in their environments. Mr. A was particularly sensitive to changes in his health and

worried extensively about dying in prison. All four perceived, and complained of, poorer

medical care than they believed they would have received outside of prison. Although

Mr. B and C had relatively stable health over the time we worked with them, both Mr. A

and especially Mr. D showed medical instability that affected their mood and activity participation. Mr. Ds declining cognitive capacity was especially problematic because it

resulted in behavioral symptoms that within the prison context were interpreted and dealt

with as disciplinary infractions. This more punitive response was probably exacerbated by

both Mr. Ds premorbid personality and the type of crime for which he had been convicted;

simply put, he was not an easy person to like. His case, however, illustrates the effectiveness of individual therapy sessions for building a positive relationship that can lead to positive change against this backdrop of unstable or declining health.

Other life stressors also complicated the course of treatment for these men. Perhaps the

most powerful of these was the worry about parole hearings; in the case of Mr. A, denial of

parole constituted a major challenge to his improving mood, but he was able to use the

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Meeks et al. / Treating Depression in the Prison Nursing Home

571

treatment process to work through his disappointment and manage his mood following the

denial. Additionally, Mr. A and C reported multiple family stressors, including legal problems of other family members, family illness, and the limited access to see or talk to family members. The presence of ongoing life stressors of this nature potentially not only

impedes the progress of therapy, but also provides opportunities to test the capacity of the

resident to use skills taught in the treatment to improve mood.

A final complication that we encountered in this project was the low participation by

inmates identified as potentially eligible. The refusal rate for this project was not noticeably different than refusal rates we have encountered for depressed residents in nursing

homes outside of prison. However, despite the fact that the mental health staff at the facility used their own knowledge of the inmates to nominate them for participation, the

majority of inmates who consented to be screened did not meet criteria for major or

minor depressive episodes when interviewed with the SCID. This led us to wonder

whether there was a reluctance among the residents to admit to depression, particularly

to strangers. It is possible that, had the screenings been conducted with staff members

with whom inmates had already developed some form of relationship, we would have

identified more depression.

8 Follow-Up

Participants continued to be monitored by the prisons chief psychologist, with the following outcomes approximately 6 months after termination of therapy.

Mr. A

Unfortunately, Mr. As worries about dying in prison were borne out. Approximately 1

month after the completion of the program, Mr. A died as a result of complications following a fall. Mr. A had been medically unstable for some time. However, prior to his death,

Mr. As mood improved noticeably, he was happier, and he shared more. In addition, he

continued to participate in arts and crafts as well as bingo.

Mr. B

At the beginning of the program Mr. B only rarely left his room. Though he has not

regressed to that level, Mr. B continues to spend an excessive amount of time in his room

sleeping and staring at the television. His participation in group activities has declined but

he does attend bingo. Another previously identified pleasurable activity that he has maintained is taking regular showers. His church attendance and writing have declined though

not to preprogram levels. His affect remains primarily flat though he does occasionally

smile and his eye contact has improved from what it was at the beginning of the study. A

particular pleasurable activity for Mr. B was to go outside and observe nature.

Unfortunately, he has not been able to engage in this for some time because of a prolonged

period of inclement weather.

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

572

Clinical Case Studies

Mr. C

Mr. C continues to come to bingo and enjoys his books on tape. He has had some visits from

his brother which is another identified pleasurable event. He has maintained his previous level

of high activity and has added a job of wiping down the hand rails in the nursing care unit.

He has a roommate with whom he gets along and he continues to be social, visiting with other

inmates on a regular basis. Mr. C appears upbeat and describes his mood as good.

Mr. D

Mr. D has significantly decreased in cognitive functioning since the end of the program.

In addition, his health has declined. He spends most of his time in his room sleeping. He

now requires a wheel chair for ambulation. He continues to be disliked by staff and other

inmates and is now serving segregation time for displaying threatening behavior toward his

roommate. Despite this, Mr. D can respond pleasantly when treated with compassion.

9 Treatment Implications of the Cases

These four cases suggest that, once cases are identified, BE-ACTIV is feasible in the prison

nursing home and has the potential to improve the quality of life for medically frail prisoners

by helping them to identify meaningful or pleasant activities. The cases illustrate how the relationship with the therapist is an important aspect of the intervention, despite its behavioral

emphasis. In addition, BE-ACTIV encourages the development of a productive and positive

relationship with recreational staff members, giving them explicit tasks that can help structure

their work with prisoners and allowing prisoners to have an ally within the prison system. The

cases show how relatively few resources can be brought to make a difference in the activity

levels and satisfaction of inmates, and that increases in activity levels can lead to improvements

in negative affect, depressive symptoms, and psychiatric functioning. The intervention uses relatively few resources that are already available in most prison settings, and therefore, to the

extent that treatment for depression may reduce morbidity, activities of daily life (ADL) dependency, and excess mortality, such a treatment may be seen as a cost-effective means of preventing other problems that might arise for depressed inmates. The cases studies presented

here, therefore, suggest that it may be appropriate to further evaluate BE-ACTIV in the prison

setting in a larger, controlled research study.

10 Recommendations to Clinicians and Students

Clinicians working in prison settings face numerous barriers that have been explored in

recently published books (Pollock et al., 2006; Saunders, 2001). Despite these barriers, our

cases illustrate that a useful therapistinmate relationship can be established relatively quickly

in the context of a structured, manualized, behavioral treatment. We found that it was not necessary to explore the prisoners past experiences or criminal activity to treat their depression

effectively. A working partnership with nonmental health staff in the prison unit is a critical

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Meeks et al. / Treating Depression in the Prison Nursing Home

573

part of BE-ACTIV and serves two purposes: (a) to ensure that pleasant events are implemented and (b) to provide the inmate with an ally whose function extends beyond mental

health care to enjoyment of day-to-day life. Furthermore, the alliance with a recreational therapist helps increase the likelihood that activities will be maintained once active mental health

treatment is ended, although we did not test this assumption in the present project.

Note

1. To protect the anonymity of the participants, inmates actual ages are not given in the case descriptions.

References

Aday, R. (1994). Golden years behind bars: Special programs and facilities for elderly inmates [Electronic version]. Federal Probation, 58(2), 47.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.).

Washington, DC: Author.

Baillargeon, J., Black, S. A., Contreras, S., Grady, J., & Pulvino, J. (2002). Anti-depressant prescribing patterns

among prison inmates with depressive disorders. U.S. Department of Justice Document #194054. Retrieved

January 16, 2008, from the National Criminal Justice Reference Service Web site: http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/194054.pdf

Bender, E. (2005). Prison punishment exacerbates inmates psychiatric illness. Psychiatric News, 40, 15-16.

Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2003). Census of state and federal correctional facilities, 2000. Revised 2003.

Retrieved January 16, 2008, from http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/csfcf00.pdf

Brink, T. L., Yesavage, J. A., Owen, L., Heersema, P., Aey, M., & Rose, T. L. (1982). Screening tests for geriatric depression. Clinical Gerontologist, 1, 37-43.

Fazel, S., Hope, T., ODonnell, I., & Jacoby, R. (2001). Hidden psychiatric morbidity in elderly prisoners

[Electronic version]. British Journal of Psychiatry, 179, 535-539.

Fazel, S., Hope, T., ODonnell, I., & Jacoby, R. (2004). Unmet treatment needs of older prisoners: A primary

care survey. Age and Ageing, 33, 396-398.

Fazel, S., & Lubbe, S. (2005). Prevalence and characteristics of mental disorders in jails and prisons. Current

Opinion in Psychiatry, 18, 550-554.

First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M., & Williams, J. B. W. (2002, November). Structured Clinical Interview

for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P). New York: Biometrics

Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading

the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatry Research, 12, 189-198.

Goetting, A. (1983). The elderly in prison. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 20, 291-309.

James, D. J., & Glaze, L. E. (2006). Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. U. S. Department of

Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ 213600, September. Retrieved January 16, 2008, from

http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/mhppji.pdf

Konrad, N., Daigle, M. S., Daniel, A. E., Dear, G. E., Frottier. P., Hayes, L. M., et al. (2007). Preventing suicide in prisons, Part I. Recommendations from the International Association for Suicide Prevention Task

Force on Suicide in Prisons. Crisis, 28, 113-131.

Lawton, M. P. (1997). Positive and negative affective states among older people in long-term care. In R. L.

Rubinstein & M. P. Lawton (Eds.), Depression in long-term and residential care (pp. 29-54). New York:

Springer.

Lawton, M. P., Kleban, M. H., Dean, J., Rajagopal, D., & Parmelee, P. A. (1992). The factorial generality of

brief positive and negative affect measures. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 47, 228-237.

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

574

Clinical Case Studies

Lewinsohn, P. M., Hoberman, H., Teri, L., & Hautzinger, M. (1985). An integrative theory of depression. In S. Reiss

& R. R. Bootzin (Eds.), Theoretical issues in behavior therapy (pp. 331-359). New York: Academic Press.

Meeks, S., & Burton, E. G. (2004). Nursing home staff characteristics and knowledge gain from a didactic

workshop on depression and behavior management. Gerontology and Geriatrics Education, 25, 57-66.

Meeks, S., & Depp, C. A. (2002). Pleasant-events based behavioral intervention for depression in nursing home

residents: A conceptual and empirical foundation. Clinical Gerontologist, 25, 125-148.

Meeks, S., Heuerman, A., Ramsey, S., Welsh, D., & White, K. (2005, November). The Pleasant Events

ScaleNursing Home Version: Development and validation. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the

Gerontological Society of America, Orlando, FL.

Meeks, S., Looney, S. W., Van Haitsma, K., & Teri, L. (2008). BE-ACTIV: A staff-assisted, behavioral intervention for depression in nursing homes. The Gerontologist, 48, 105-114.

Meeks, S., Teri, L., Van Haitsma, K., & Looney, S.W. (2006). Increasing pleasant events in the nursing home:

Collaborative behavioral treatment for depression. Clinical Case Studies, 5, 287-304.

Nelson, E. C., Wasson, J., Johnson, D. J., & Hays, R. D. (n.d.). Dartmouth COOP functional health assessment

charts: Brief measures for clinical practice. Retrieved June 16, 2005, from the Dartmouth University COOP

Project Web site: http://www.dartmouth.edu/~coopproj/more_charts.html

Nelson, E. C., Wasson, J., Kirk, J., Keller, A., Clark, D., Dietrich, A., et al. (1987). Assessment of function in

routine clinical practice: Description of the COOP chart method and preliminary findings. Journal of

Chronic Diseases, 40, 55S-63S.

National Institutes of Health. (2007). Re-engineering the clinical research enterprise. Retrieved January 9,

2008, from http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/clinicalresearch/overview-translational.asp

Pollock, P. H., Stowell-Smith, M., & Gpfert, M. (Eds.). (2006). Cognitive analytic therapy for offenders.

London: Routledge.

Saunders, J. W. (Ed.). (2001). Life within hidden worlds. Psychotherapy in prisons. London: Karnac Books.

Senior, J., Hayes, A. J., Pratt, D., Thomas, S. D., Fahy, T., Leese, M., et al. (2007). The identification and management of suicide risk in local prisons. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 18, 368-380.

Teri, L. (1994). Behavioral treatment of depression in patients with dementia. Alzheimers Disease and

Associated Disorders, 8, 66-74.

Teri, L. (1997). The relation between research on depression and a treatment program: One model. In R. L. Rubinstein

& M. P. Lawton (Eds.), Depression in long-term and residential care (pp. 129-153). New York: Springer.

Teri, L., Logsdon, R., & Uomoto, J. (1991). Treatment of depression in patients with Alzheimers disease.

Therapist Manual. Seattle: University of Washington School of Medicine.

Teri, L., Logsdon, R. G., Uomoto, J., & McCurry, S. M. (1997). Behavioral treatment of depression in dementia patients: A controlled clinical trial. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 52B, P159-P166.

Vernig, P. M. (2007). From science to practice: Bridging the gap with translational research. APS Observer, 20(2).

Retrieved January 19, 2008, from http://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/getArticle.cfm? id=2133

Suzanne Meeks, PhD, is a professor of clinical psychology in the Department of Psychological and Brain

Sciences at the University of Louisville. She has been involved in clinical work and research in nursing homes

for more than 20 years as part of her broader research focus on mental illness in late life.

Robin Sublett, PhD, is the chief psychologist at the Kentucky State Reformatory. She currently provides clinical services in the Nursing Care Facility as well as supervises the General Psychological Services.

Irene Kostiwa, MA, is a doctoral student in clinical psychology at the University of Louisville. Her research

interests include sleep and mood problems among long-term care residents.

James R. Rodgers, MA, is a doctoral student in clinical psychology at the University of Louisville, completing his internship at the Southwest Texas Veterans Health Center during the 2008-2009 academic year. His

research and clinical interests focus on end-of-life care.

Donna Haddix is a recreation leader at the Kentucky State Reformatory. She supervises recreation services in

the Correctional Psychiatric Unit as well as the Nursing Care Facility.

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- HNR 3700 - Community Perceptions of Prison Health Care Final ProposalDokumen18 halamanHNR 3700 - Community Perceptions of Prison Health Care Final Proposalapi-582630906Belum ada peringkat

- Running Head: Annotated Bibliography Tomkins 1Dokumen9 halamanRunning Head: Annotated Bibliography Tomkins 1api-303232478Belum ada peringkat

- 13 PGDokumen13 halaman13 PGSamson MbuguaBelum ada peringkat

- KFP Part 4Dokumen14 halamanKFP Part 4api-726694735Belum ada peringkat

- Mental Health and Palliative Care Literature ReviewDokumen4 halamanMental Health and Palliative Care Literature ReviewafdtbwkhbBelum ada peringkat

- Running Head: Confinement and Mental Illness in U.S Prisoners 1Dokumen19 halamanRunning Head: Confinement and Mental Illness in U.S Prisoners 1Tonnie KiamaBelum ada peringkat

- Inpatient Geriatric Psychiatry: Optimum Care, Emerging Limitations, and Realistic GoalsDari EverandInpatient Geriatric Psychiatry: Optimum Care, Emerging Limitations, and Realistic GoalsHoward H. FennBelum ada peringkat

- 140.editedDokumen19 halaman140.editedTonnie KiamaBelum ada peringkat

- Example Review and Critique of A Qualitative StudyDokumen6 halamanExample Review and Critique of A Qualitative StudyWinnifer KongBelum ada peringkat

- Centre For Policy On Ageing Information Service Selected ReadingsDokumen62 halamanCentre For Policy On Ageing Information Service Selected ReadingsC Hendra WijayaBelum ada peringkat

- 2017, Family Intervention in A Prison Environment A Systematic Literature ReviewDokumen17 halaman2017, Family Intervention in A Prison Environment A Systematic Literature ReviewEduardo RamirezBelum ada peringkat

- Scholarly PaperDokumen6 halamanScholarly Paperapi-430368919Belum ada peringkat

- RecommendedDokumen9 halamanRecommendedMaya Putri Haryanti100% (1)

- Mental Health FacilitiesDokumen11 halamanMental Health FacilitiesMiKayla PenningsBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing Annotated BibliographyDokumen7 halamanNursing Annotated BibliographyAssignment Help Australia100% (1)

- 675-Article Text-2218-2-10-20130830Dokumen22 halaman675-Article Text-2218-2-10-20130830Marijana PsihoBelum ada peringkat

- Running Head: Health Care Setting Impact On Patients With Neurodegenerative DiseasesDokumen14 halamanRunning Head: Health Care Setting Impact On Patients With Neurodegenerative DiseasesJackie WilsonBelum ada peringkat

- Ageing Prisoners: An Introduction To Geriatric Health-Care Challenges in Correctional FacilitiesDokumen24 halamanAgeing Prisoners: An Introduction To Geriatric Health-Care Challenges in Correctional FacilitiesepraetorianBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation of A Comedy Intervention To Improve Coping and Help-Seeking For Mental Health Problems in A Women ' S PrisonDokumen8 halamanEvaluation of A Comedy Intervention To Improve Coping and Help-Seeking For Mental Health Problems in A Women ' S PrisonGINA ZEINBelum ada peringkat

- Policy BriefDokumen10 halamanPolicy Briefapi-607761527Belum ada peringkat

- Negative Impacts That Prison Has On Mentally Ill PeopleDokumen15 halamanNegative Impacts That Prison Has On Mentally Ill PeopleIAN100% (1)

- The Role of Family Empowerment and Family Resilience On Recovery From PsychosisDokumen12 halamanThe Role of Family Empowerment and Family Resilience On Recovery From PsychosisSyahwira ramadhanBelum ada peringkat

- Peer Victimization PaperDokumen21 halamanPeer Victimization Paperapi-249176612Belum ada peringkat

- 8.2.1 Rosenhan (1973) On Being Sane in Insane Places.: Studies Clinical PsychologyDokumen3 halaman8.2.1 Rosenhan (1973) On Being Sane in Insane Places.: Studies Clinical PsychologySara AbrahamBelum ada peringkat

- Walker 2020Dokumen22 halamanWalker 2020Stella GašparušBelum ada peringkat

- Major mental disorders linked to higher criminality and violence ratesDokumen20 halamanMajor mental disorders linked to higher criminality and violence ratesAndrés Rojas OrtegaBelum ada peringkat

- A Literature Review Psychiatric BoardingDokumen13 halamanA Literature Review Psychiatric Boardingn0nijitynum3100% (1)

- 15stefaan de Smet PDFDokumen9 halaman15stefaan de Smet PDFJorge PlanoBelum ada peringkat

- Three Propositions For An Evidence-Based Medical AnthropologyDokumen16 halamanThree Propositions For An Evidence-Based Medical AnthropologypatriciamadariagaBelum ada peringkat

- Gender Differences Among Prisoners in Drug TreatmentDokumen22 halamanGender Differences Among Prisoners in Drug TreatmentlosangelesBelum ada peringkat

- An Anatomy of LonelinessDokumen4 halamanAn Anatomy of LonelinessTheodore LiwonganBelum ada peringkat

- Archives of Psychiatric Nursing: Krystyna de Jacq, Allison Andreno Norful, Elaine LarsonDokumen9 halamanArchives of Psychiatric Nursing: Krystyna de Jacq, Allison Andreno Norful, Elaine LarsonleticiaBelum ada peringkat

- Coleman Et Al. - JPRDokumen7 halamanColeman Et Al. - JPRWitrisyahPutriBelum ada peringkat

- Senior FinalDokumen23 halamanSenior Finalapi-350348558Belum ada peringkat

- Research PaperDokumen12 halamanResearch Paperapi-451581488Belum ada peringkat

- Behaviour Research and Therapy: Alan E. KazdinDokumen12 halamanBehaviour Research and Therapy: Alan E. KazdinDroguBelum ada peringkat

- Literature Review Suicide in PrisonDokumen4 halamanLiterature Review Suicide in Prisonafmzrvaxhdzxjs100% (1)

- Tiro IdesDokumen12 halamanTiro IdesArturo MelgarBelum ada peringkat

- St. Denis - Forensic Psych in ChileDokumen8 halamanSt. Denis - Forensic Psych in ChileKendall RunyanBelum ada peringkat

- Pt. B. D. Sharma University of Health Sciences, RohtakDokumen30 halamanPt. B. D. Sharma University of Health Sciences, RohtaknikhilBelum ada peringkat

- Psychology Assessment - I - M1Dokumen42 halamanPsychology Assessment - I - M1Brinda ChughBelum ada peringkat

- Literature Review DeliriumDokumen7 halamanLiterature Review Deliriumafmzadevfeeeat100% (1)

- Literature ReviewDokumen11 halamanLiterature Reviewapi-582875150Belum ada peringkat

- Running Head: Effects of Follow-Up Psychiatric Care 1Dokumen20 halamanRunning Head: Effects of Follow-Up Psychiatric Care 1api-409577818Belum ada peringkat

- 22 Depression Alliance Abstracts, July 09Dokumen6 halaman22 Depression Alliance Abstracts, July 09sunkissedchiffonBelum ada peringkat

- Sosial Capital's Link to Depression, Pain & SymptomsDokumen9 halamanSosial Capital's Link to Depression, Pain & SymptomsSiti Anisa FatmawatiBelum ada peringkat

- Neurobehavioural and cognitive function linked to childhood trauma in homeless adultsDokumen13 halamanNeurobehavioural and cognitive function linked to childhood trauma in homeless adultsReal NoloseBelum ada peringkat

- A Time-Series Study of The Treatment of Panic DisorderDokumen21 halamanA Time-Series Study of The Treatment of Panic Disordermetramor8745Belum ada peringkat

- Cognitive-Behavioral Interventions With Older AdulDokumen38 halamanCognitive-Behavioral Interventions With Older AdulMARIELA LIZETH VALENTE CORTEZBelum ada peringkat

- Long Term Effects of Anabolic SteroidsDokumen3 halamanLong Term Effects of Anabolic SteroidsMadelaine EvangelioBelum ada peringkat

- Module 5 PaperDokumen8 halamanModule 5 PaperWinterBelum ada peringkat

- Racial Differences in Self-Reports of Sleep Duration in A Population-Based StudyDokumen8 halamanRacial Differences in Self-Reports of Sleep Duration in A Population-Based StudyRivhan FauzanBelum ada peringkat

- 5 Western Models For Mental Health BentallDokumen4 halaman5 Western Models For Mental Health BentallimanuelcBelum ada peringkat

- Intelligence and Personality As PredictorsDokumen96 halamanIntelligence and Personality As PredictorsTrifan DamianBelum ada peringkat

- Psych 3Dokumen17 halamanPsych 3austinviernes99Belum ada peringkat

- A CritiqueDokumen9 halamanA Critiquewangarichristine12Belum ada peringkat

- Exploring The - Near-Suicide - Phenomenon Using Mindsponge TheoryDokumen3 halamanExploring The - Near-Suicide - Phenomenon Using Mindsponge TheoryLuyện TrầnBelum ada peringkat

- Sa Psy150-28Dokumen2 halamanSa Psy150-28api-438183736Belum ada peringkat

- Eugenics as a Factor in the Prevention of Mental DiseaseDari EverandEugenics as a Factor in the Prevention of Mental DiseaseBelum ada peringkat

- Addiction Recovery Management: Theory, Research and PracticeDari EverandAddiction Recovery Management: Theory, Research and PracticeBelum ada peringkat

- Animalele - Material Terapie ABADokumen17 halamanAnimalele - Material Terapie ABAAndreea NicolaeBelum ada peringkat

- David Gordon - Phoenix - Therapeutic Patterns of Milton H. EricksonDokumen203 halamanDavid Gordon - Phoenix - Therapeutic Patterns of Milton H. EricksonNora Grigoruta100% (9)

- Time Limited Psychotherapy PDFDokumen52 halamanTime Limited Psychotherapy PDFlara_2772Belum ada peringkat

- 3 Full PDFDokumen21 halaman3 Full PDFAndreea NicolaeBelum ada peringkat

- Behavioral Therapy For Anxiety DisordersDokumen18 halamanBehavioral Therapy For Anxiety DisordersAndreea NicolaeBelum ada peringkat

- 555 Full PDFDokumen21 halaman555 Full PDFAndreea NicolaeBelum ada peringkat

- An Investigation of Health Anxiety in FamiliesDokumen12 halamanAn Investigation of Health Anxiety in FamiliesAndreea NicolaeBelum ada peringkat

- 382 Full PDFDokumen22 halaman382 Full PDFAndreea NicolaeBelum ada peringkat

- Behavioral Therapy For Anxiety DisordersDokumen18 halamanBehavioral Therapy For Anxiety DisordersAndreea NicolaeBelum ada peringkat

- A Time-Series Study of The Treatment of Panic DisorderDokumen21 halamanA Time-Series Study of The Treatment of Panic Disordermetramor8745Belum ada peringkat

- Oppositional Defiant DisorderDokumen13 halamanOppositional Defiant DisorderAndreea NicolaeBelum ada peringkat

- Behavioral Therapy For Anxiety DisordersDokumen18 halamanBehavioral Therapy For Anxiety DisordersAndreea NicolaeBelum ada peringkat

- Cognitive InterventionDokumen13 halamanCognitive InterventionAndreea NicolaeBelum ada peringkat

- Behavioral Activation in Breast Cancer PatientsDokumen14 halamanBehavioral Activation in Breast Cancer PatientsAndreea NicolaeBelum ada peringkat

- Don't Kick Me OutDokumen14 halamanDon't Kick Me OutAndreea NicolaeBelum ada peringkat

- RADDokumen25 halamanRADAndreea NicolaeBelum ada peringkat

- Relation ASD - ADHDDokumen16 halamanRelation ASD - ADHDAndreea NicolaeBelum ada peringkat

- The Role of Attention - ASDDokumen13 halamanThe Role of Attention - ASDAndreea NicolaeBelum ada peringkat

- Behavioral Activation As An Intervention For Coexistent Depressive and Anxiety SymptomsDokumen13 halamanBehavioral Activation As An Intervention For Coexistent Depressive and Anxiety SymptomsAndreea NicolaeBelum ada peringkat

- Assessment and Behavioral Treatment of Selective MutismDokumen22 halamanAssessment and Behavioral Treatment of Selective MutismAndreea NicolaeBelum ada peringkat

- 9 Feeding Therapy in A Child With Autistic DisorderDokumen12 halaman9 Feeding Therapy in A Child With Autistic DisorderArden AriandaBelum ada peringkat

- The Five Therapeutic RelationshipsDokumen16 halamanThe Five Therapeutic RelationshipsAndreea Nicolae100% (2)

- The Use of Homework Success For A Child With Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder, Predominantly Inattentive TypeDokumen14 halamanThe Use of Homework Success For A Child With Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder, Predominantly Inattentive TypeAndreea NicolaeBelum ada peringkat

- Internet-Related Psychopathology Clinical Phenotypes and PerspectivesDokumen138 halamanInternet-Related Psychopathology Clinical Phenotypes and PerspectivesAndreea NicolaeBelum ada peringkat