Topic 5 Singaporean Good Governance

Diunggah oleh

RonaldDarmawanvanNistelrooy0%(1)0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (1 suara)

454 tayangan3 halamanthis talks about singapore good governance.. a good read for strategic global business class lee kwan yew

Judul Asli

Topic 5 Singaporean Good Governance(5)

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen Inithis talks about singapore good governance.. a good read for strategic global business class lee kwan yew

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0%(1)0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (1 suara)

454 tayangan3 halamanTopic 5 Singaporean Good Governance

Diunggah oleh

RonaldDarmawanvanNistelrooythis talks about singapore good governance.. a good read for strategic global business class lee kwan yew

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 3

Closing Case

Singaporean good governance, prosperity and future challenges

Introduction

Singapore's success story of rapid economic development

has been examined extensively by admirers from near

and far, as the small island state has risen since the 1960s

to become a global city that attracts skilled professionals

and multinational enterprises (Ghesquiere 2007; Lim

2009). Singapore's success has highlighted the crucial

importance of good public governance, one able to

adapt to new circumstances over time:

After spending forty years engaged in the economic

development of Singapore, I am convinced that

the most important condition for success is good

government. A good government is one led by able,

honest, selfless men and women (Ngiam 2006: 88).

The People's Action Party (PAP) leadership's highly

pragmatic leanings, a reputation for prudent financial

management and an effective anti-corruption stance

has meant that foreign political and enterprise leaders

have found the Singaporean government easy to engage

w ith. Recent efforts throughout the late 1990s and first

decade of the 2000s to attract MNEs at the forefront

of innovation (biotechnology, medicine, advanced

electronics) have come off the back of a 30-year record

of attracting and developing partnerships with MNEs

looking to utilise Singapore at lower-level technical

skills capacities (broad consumer electronics, shipping

maintenance and others).

The Singaporean government's relationship with private

enterprise is clear; it has been willing to participate in

the national economy across many sectors, but has

never sought to protect domestic enterprises at the

expense of foreign MNEs interested in investing in the

national economy. State enterprises, government-linked

corporations (GLCs) and state-encouraged enterprises

were all founded and developed by the government,

largely to enhance trade activity and support MNEs'

operations in the island-state. Singapore Airlines,

Changi Airport, the Port Authority of Singapore (PSA)

and the SGX (Singapore Stock Exchange), to name but

a few, were all established and run by the Singapore

government and are now internationally recognised for

excellence in their respective sectors. As a city-state

with a small market and a large, strategically located

port, the government and commercial elite (often one

and the same) has been a constant champion of global

free trade. Today, Singapore remains active in both

204

bilateral and multilateral trade processes (such as the

Singapore-Australia Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA) and

the multilateral WTO Doha Round of free trade talks).

The Singaporean government argues that even when

multilateral processes such as the Doha Round break

down, free trade agreements (FTAs) remain the pathway

forward for the city-economy (Singapore FTA Network).

Singapore's political and macroeconomic environments,

therefore, are all attuned to the needs and wants of MNEs

seeking a risk-free environment from which to launch

their products and services into greater Asia. Indeed,

there is little risk in stating that Singapore is without peer

in enacting policy prescriptions that are favourable to

MNEs' operations, and in supporting these with an array

of practical infrastructure, legal, human resource and

social initiatives.

The dominance of the People's Action Party and the

economy

Since its independence in 1959, Singapore has been

ruled by one party: the People's Action Party. For

much of the time it was led by Lee Kuan Yew (195990), who took the political position that Singapore

could not accommodate open political contests like

more developed economies such as the United States

and Britain . Lee saw political stability as an essential

requirement for attracting much-needed foreign MNE

capital and enterprise to the island-state, which at the

time suffered from chronic unemployment. To ensure

that MNEs viewed Singapore as a politically stable

environment for all manner of investments, Lee was

more than prepared to utilise the full repressive powers

of the state (a legacy of British rule) against his political

opponents. In this he was very successful, and Singapore

quickly established itself throughout the 1960s and

1970s as the premier location in Southeast Asia for

politically risk-free foreign investment. In election

after election, the PAP took an even firmer grip on the

institutions of the Singapore state, to the point where

the differentiation between the PAP and the Singapore

government became simply academic.

By the early 1990s Lee Kuan Yew was ready to hand

on the prime ministership to a selected successor, Goh

Chong Tong (1990-2004), who proceeded to maintain

and develop further Lee's work so that the 1990s

saw Singapore firmly establish itself as a global city

within MNE planning and operations. Goh came to be

very much admired within the international business

Chapter 7 Political and legal systems in national environments

community as a steady governing hand, leading a

government that clearly understood their business

requirements, and domestically he was seen as politically

less abrasive than his predecessor. In the political realm,

he maintained the PAP's take-no-prisoner approach to

political opposition, which had been firmly established

by Lee, and in the economic realm led Singapore

throughout the 1997 Asian financial crisis and 2001 dotcom downturn. Goh, in turn, managed the transition in

2004 to the current prime minister, Lee Hsien Loong,

with what has come to be seen as typical Singaporean

efficiency. The current prime minister is in fact the son of

Lee Kuan Yew, and came to the position after a decadelong apprenticeship in core financial ministry positions,

including managing Singapore's banking and financial

sector th roughout the 1997 Asian financial crisis. As a

result, Lee Hsien Loong came to the prime ministership

well versed in international finance and MNE operations,

and the international business community knew him to

be a well-credentialled policy operative. Equally so, it

has come as little surprise that Prime Minister Lee has

maintained a firm grip on Singapore's political space.

His actions show clearly that the PAP leadership firmly

believes that Singapore cannot afford even the slightest

hi nt of political risk. The PAP's legitimacy resides in its

ability to govern for Singapore's prosperity through

domestic state-owned enterprises and by retaining the

confidence of the leaders of MNEs, which continue to

deliver significant investment into the city-state across

a wide array of sectors, from finance to integrated

resorts.

The global financial crisis and Singapore's response

Singapore's S$248 billion economy scraped in a 1.1

per cent growth rate for 2008, compared to 7.7 per

cent growth in 2007. It then shrank to -1.3 per cent for

the whole of 2009 (www.singstat.gov.sg/stats). What

shocked most observers was the speed of the decline of

the Singaporean economy. Having grown 6.7 per cent in

t he first quarter of 2008, it then fell off a cliff, plunging to

-0.6 per cent of GOP for the third quarter and to -3.7 per

cent in the fourth quarter (Chong 2009: 291 ; Nicholas

2008). For a nation that had growth rates of over 7 per

cent for the previous year, the dramatic nature of the

economic decline was stark. Multinational and domestic

enterprises immediately began re-engineering and

enacting retrenchment as their export orders evaporated.

Singapore's Creative Technologies Ltd, a large domestic

technology firm, cut its workforce by 2700 in 2008 as

international orders dried up.

Singapore's economic decline in 2008 and 2009

prompted questions regarding the country's economic

policy of ultra-globalisation. Even at the height of its

205

mid-decade boom (2002-07), some were alarmed at the

country's high levels of exposure to global economic

fluctuations:

With a broad lens one can begin to identify the

signs of a maturing capitalist economy. Structural

unemployment, the disappearance of low-skilled

jobs, the economic marginalization of the old and less

educated, and the widening income gap between the

haves and the have nots, all suggest that the neecapitalist processes are deeply embedded in the

national economy and are, consequently, making

the domestic workforce and industries vulnerable to the

capricious forces of globalization. (Chong 2006: 269)

Prior to the global financial crisis policymakers had,

at different times, made their concerns clear~over the

economy's considerable exposure to a US economic

downturn.ln the second half of 2008 Singapore slid into

recession and, with no signs of economic recovery in

early 2009, Prime Minister Lee warned that Singapore

would continue to suffer throughout 2009. He stated:

The recession is a global one, and we must expect

to see exports and growth remain negative for more

months, and perhaps for the whole year. (Asean

Affairs 2009)

Lee responded to the crisis by introducing a S$20.5

billion (US$13.7 billion) stimulus package equivalent

to 8 per cent of Singapore's GOP, within which his

government included S$5.8 billion to spur bank

lending, S$5.1 billion to help save jobs, S$2.6 billion

in ta x measures and grants for business, S$4.4

billion in infrastructure spending and S$2.6 billion

for households. Most notably, S$4.9 billion of the

package came from government reserves, the first

time Singapore's policymakers had ever resorted to

such a measure. It could be argued that the amount

was not significant when compared to Singapore's

massive foreign reserves and Government Investment

Corporation (GIC) managed funds, but the symbolism

was noted widely. The government had made it

known that it would intervene to stem the economy's

decline.

In 2010 the Singapore economy roared back to life, with

globalisation proving that a city inextricably linked into

the process can recover as quickly as it can decline. What

is also clear is that Singapore's position on public debt is

in stark contrast to that of other developed economies,

particularly the European Union and the United States.

Singapore is a net exporter of capital, with savings levels

206

Part 2

The environment of international business

equal to those in other Asian economic powers such as

Japan, Taiwan, South Korea and an emerging China.

This capital position, driven by government-initiated

savings regimes and budgetary strict discipline, can be

expected to provide Singapore with significant future

competitive advantages. Also notable has been the

Singapore government's willingness to use its ample

reserves to invest in providing Singapore with a worldclass infrastructure, from Changi Airport to high-speed

broadband, which pays dividends once the economy

reverts to a high growth trajectory.

Case questions

1. Can Singapore now be defined as a politico-global

state, one in which globalisation, and not one

domestic political party, truly governs t he country?

2. Does Singapore's developmental experience prove

false the old dichotomy of the private sector being

inherently superior to public enterprise?

3. Is Singapore a val id model for other countries, or does

its status as a city-state make it relevant only to other

small city-state entities (Hong Kong and Dubai being

two obvious cases)?

Sources: 'Singapore: Recession May Last Whole of 2009', Asean

Affairs: The Voice of Southeast Asia, 25 January 2009; T. Chong (2006),

'Singapore: Globalizing on its Own Terms', in D. Singh and L. C. Salazar

(2006). Southeast Asian Affairs 2006, Singapore: Institute of Southeast

Asian Studies; H. Ghesquiere (2007), Singapore's Success: Engineering

Economic Growth, Singapore: Thomson; C. Y. Lim (2009), 'Transformation

in the Singapore Economy: Course and Causes', in W. M. Chai and

H. Y. Sng, Singapore and Asia in a Globalized World: Contemporary

Economic Issues and Policies, Singapore: World Scientific, pp. 3-24;

T. D. Ngiam, with introduction and edited by S. S. C. Tay (2006), A

Mandarin and the Making of Public Policy: Reflections by Ngiam Tong

Dow, Singapore: NUS Press; K. Nicholas, 'Asian Tiger Begins to Lose its

Vitality', Australian Financial Review, 22 February 2008; Singapore FTA

Network, www.fta.gov.sg, accessed 2 April 2009; Singapore Statistics,

Government of Singapore, www.singstat.gov.sg/stats.

This case was written by /an Austin, Edith Cowan University, Australia,

2010.

Key terms

country risk, p. 181

extraterritoriality, p. 201

intellectual property, p. 199

legal system, p. 184

political system, p. 183

rule of law, p. 190

transparency, p. 202

Summary

In this chapter, you learned about:

1. What is country risk?

International business is influenced by political

and legal systems. Country risk refers to exposure

to potential loss or to adverse effects on company

operations and profitability caused by developments

in a country's political and legal environments.

2. What are political and legal systems?

A political system is a set of formal institutions

that constitute a government. A legal system is a

system for interpreting and enforcing laws. Adverse

developments in political and legal systems increase

country risk. These can result from events such as a

change in government or the creation of new laws or

regulations.

3. Types of political syst ems

The three existing major political systems are

totalitarianism, socialism and democracy. These

systems are the frameworks within which laws are

established and nations are governed. Most countries

today employ some combination of democracy and

socialism. Democracy is characterised by private

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Thailand: Industrialization and Economic Catch-UpDari EverandThailand: Industrialization and Economic Catch-UpBelum ada peringkat

- Macro Objectives of The Central Provident FundDokumen19 halamanMacro Objectives of The Central Provident FundPianoGuys90Belum ada peringkat

- Digest of the Handbook on Electricity Markets - International Edition: 2022, #9Dari EverandDigest of the Handbook on Electricity Markets - International Edition: 2022, #9Belum ada peringkat

- EC3332 Midterms NotesDokumen8 halamanEC3332 Midterms NotesSebastian LimBelum ada peringkat

- Digest of the Handbook on Electricity Markets - China Edition: 2022, #9Dari EverandDigest of the Handbook on Electricity Markets - China Edition: 2022, #9Belum ada peringkat

- Winning by Process: The State and Neutralization of Ethnic Minorities in MyanmarDari EverandWinning by Process: The State and Neutralization of Ethnic Minorities in MyanmarBelum ada peringkat

- Renewable energy auctions: Southeast AsiaDari EverandRenewable energy auctions: Southeast AsiaBelum ada peringkat

- Handbook of the Economics of EducationDari EverandHandbook of the Economics of EducationPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (2)

- The Economics and Politics of China’s Energy Security TransitionDari EverandThe Economics and Politics of China’s Energy Security TransitionBelum ada peringkat

- Accepting Authoritarianism: State-Society Relations in China's Reform EraDari EverandAccepting Authoritarianism: State-Society Relations in China's Reform EraPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (2)

- Macromodeling Debt and Twin Deficits: Presenting the Instruments to Reduce ThemDari EverandMacromodeling Debt and Twin Deficits: Presenting the Instruments to Reduce ThemBelum ada peringkat

- Community Secondary Schools in Tanzania: Challenges and ProspectsDari EverandCommunity Secondary Schools in Tanzania: Challenges and ProspectsPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1)

- The Powers That Be: Global Energy for the Twenty-first Century and BeyondDari EverandThe Powers That Be: Global Energy for the Twenty-first Century and BeyondPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- Foreign Direct Investment in Brazil: Post-Crisis Economic Development in Emerging MarketsDari EverandForeign Direct Investment in Brazil: Post-Crisis Economic Development in Emerging MarketsPenilaian: 1 dari 5 bintang1/5 (1)

- Tactical Globalization Learning From The Singapore ExperimentDokumen224 halamanTactical Globalization Learning From The Singapore ExperimentmemoBelum ada peringkat

- Haggard - Developmental StatesDokumen96 halamanHaggard - Developmental StatesBrandon ChacónBelum ada peringkat

- The Rise and Fall of The Developmental StateDokumen12 halamanThe Rise and Fall of The Developmental Statematts292003574Belum ada peringkat

- Singapore's CPF Scheme - Wages and JusticeDokumen11 halamanSingapore's CPF Scheme - Wages and JusticeCrystal WongBelum ada peringkat

- Singapore-China Special Economic Relations:: in Search of Business OpportunitiesDokumen26 halamanSingapore-China Special Economic Relations:: in Search of Business OpportunitiesrrponoBelum ada peringkat

- Adequacy of Singapore CPF PayoutDokumen28 halamanAdequacy of Singapore CPF PayoutlinhanlongBelum ada peringkat

- Stockmann - Media Commercialization and Authoritarian Rule in China (2013)Dokumen360 halamanStockmann - Media Commercialization and Authoritarian Rule in China (2013)thierryBelum ada peringkat

- Burma/Myanmar: Outside Interests and Inside Challenges, Outside InterestsDokumen234 halamanBurma/Myanmar: Outside Interests and Inside Challenges, Outside Interestsrohingyablogger100% (1)

- 2021 06 11 Thant Myint U Myanmar Coming Revolution en RedDokumen18 halaman2021 06 11 Thant Myint U Myanmar Coming Revolution en Redakar phyoe100% (1)

- Globalization and StateDokumen5 halamanGlobalization and Stateshereen padchongaBelum ada peringkat

- Ding Soft PowerDokumen269 halamanDing Soft PowerAndreeaBelum ada peringkat

- The Soft Power of Cool: Japanese Foreign Policy in The 21st CenturyDokumen16 halamanThe Soft Power of Cool: Japanese Foreign Policy in The 21st CenturyYusril ZaemonBelum ada peringkat

- Global Cities and Developmental StatesDokumen29 halamanGlobal Cities and Developmental StatesmayaBelum ada peringkat

- Chinese Politics and Foreign Policy Under Xi Jinping The Future Political Trajectory (2021)Dokumen385 halamanChinese Politics and Foreign Policy Under Xi Jinping The Future Political Trajectory (2021)John TheBaptistBelum ada peringkat

- The Role of The Military in Turkish Poli PDFDokumen20 halamanThe Role of The Military in Turkish Poli PDFusman93pk100% (1)

- Impact of China On South Korea's Economy by Cheong Young-RokDokumen21 halamanImpact of China On South Korea's Economy by Cheong Young-RokKorea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Belum ada peringkat

- Globalization of World PoliticsDokumen46 halamanGlobalization of World Politicsmehran_cadet904475% (4)

- RostowDokumen20 halamanRostowFarhad ZulfiqarBelum ada peringkat

- Inequality and Democratic Political EngagementDokumen13 halamanInequality and Democratic Political EngagementBonnie WrightBelum ada peringkat

- Voices of Teachers and Teacher EducatorsDokumen98 halamanVoices of Teachers and Teacher EducatorsअनिलBelum ada peringkat

- 3 Joseph StalinDokumen6 halaman3 Joseph Stalinapi-285512804Belum ada peringkat

- Embedded Autonomy or Crony Capitalism Explaining Corruption in South Korea Relative To Taiwan and The Philippines Focusing On The Role of Land Reform and Industrial PolicyDokumen45 halamanEmbedded Autonomy or Crony Capitalism Explaining Corruption in South Korea Relative To Taiwan and The Philippines Focusing On The Role of Land Reform and Industrial PolicyaalozadaBelum ada peringkat

- WHEELING THE CYCLE UP - FIRMS, OEM, AND CHAlNED NETWORKS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF TAIWAN'S BICYCLE INDUSTRYDokumen14 halamanWHEELING THE CYCLE UP - FIRMS, OEM, AND CHAlNED NETWORKS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF TAIWAN'S BICYCLE INDUSTRYJerry ChengBelum ada peringkat

- Impact of Population Growth On Sustainable DevelopmentDokumen12 halamanImpact of Population Growth On Sustainable DevelopmentOmotosho AlexBelum ada peringkat

- The Foreign Policy of Japan Under The New Abe AdministrationDokumen6 halamanThe Foreign Policy of Japan Under The New Abe AdministrationddufourtBelum ada peringkat

- Yushan Deng - MUN CVDokumen2 halamanYushan Deng - MUN CVYushan DengBelum ada peringkat

- Constructing A Democratic Developmental State in South AfricaDokumen336 halamanConstructing A Democratic Developmental State in South Africadon_h_manzano100% (1)

- Global Constructions of Multicultural EducationDokumen122 halamanGlobal Constructions of Multicultural EducationAbyStanciuBelum ada peringkat

- ITEPE Conference June2014 Libre PDFDokumen3 halamanITEPE Conference June2014 Libre PDFPedro GuilhermeBelum ada peringkat

- Vietnam's Strategic Hedging Vis-A-Vis China - The Roles of The EU and RUDokumen21 halamanVietnam's Strategic Hedging Vis-A-Vis China - The Roles of The EU and RUchristilukBelum ada peringkat

- Critical Approaches To The Study of Higher Education - A Practical IntroductionDokumen342 halamanCritical Approaches To The Study of Higher Education - A Practical IntroductionVishnuBelum ada peringkat

- Geyer - European IntegrationDokumen32 halamanGeyer - European IntegrationChristopher 'Snorlax' Coates-MorrisBelum ada peringkat

- Pol7 - Conflict and PeacebuildingDokumen45 halamanPol7 - Conflict and Peacebuildingrabarber1900Belum ada peringkat

- Position Paper - Compulsory Voting - Voting BehaviourDokumen4 halamanPosition Paper - Compulsory Voting - Voting BehaviourRadu BuneaBelum ada peringkat

- Asian Economic and Political DevelopmentDokumen528 halamanAsian Economic and Political DevelopmentAhmadBelum ada peringkat

- Industrialization and Urbanization Unit PlanDokumen5 halamanIndustrialization and Urbanization Unit PlanOlivia FoorBelum ada peringkat

- Politics EUDokumen340 halamanPolitics EUBaeyarBelum ada peringkat

- China's Political and Economical Reforms: Lessons and LimitationsDokumen24 halamanChina's Political and Economical Reforms: Lessons and LimitationsTavian HunterBelum ada peringkat

- David Shambaugh-Asia in TransitionDokumen7 halamanDavid Shambaugh-Asia in TransitionTimothy YinBelum ada peringkat

- Irish Politics (Po 3630) : Learning OutcomesDokumen18 halamanIrish Politics (Po 3630) : Learning OutcomesJames ConnorBelum ada peringkat

- Service Tax Form-3aDokumen1 halamanService Tax Form-3aRavi AroraBelum ada peringkat

- Can The Developers Move For Specific Performance of The Development Agreement?Dokumen6 halamanCan The Developers Move For Specific Performance of The Development Agreement?Manas Ranjan SamantarayBelum ada peringkat

- Unit 1 Comprehensive ProjectDokumen21 halamanUnit 1 Comprehensive ProjectJanet Rosario13% (8)

- 64 Wonder Book Corporation Vs PBCOMDokumen2 halaman64 Wonder Book Corporation Vs PBCOMNorr MannBelum ada peringkat

- Tax - General Principles CasesDokumen32 halamanTax - General Principles CasesonlineonrandomdaysBelum ada peringkat

- Target 3 Stock and DividendDokumen5 halamanTarget 3 Stock and DividendAjeet YadavBelum ada peringkat

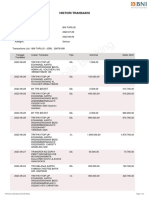

- Histori TransaksiDokumen3 halamanHistori TransaksiIyan SiwuBelum ada peringkat

- Computation 22-23Dokumen2 halamanComputation 22-23Raj DelhiBelum ada peringkat

- 04 - Intermountain Lumber v. CIRDokumen2 halaman04 - Intermountain Lumber v. CIRTrek Alojado100% (1)

- Tree of WealthDokumen121 halamanTree of WealthJoseAliceaBelum ada peringkat

- Qualification of A Finance OfficerDokumen2 halamanQualification of A Finance OfficerWilsonBelum ada peringkat

- Nutter Food and Beverage Term Sheets MaterialsDokumen39 halamanNutter Food and Beverage Term Sheets MaterialsSheila EnglishBelum ada peringkat

- Solved Finning International Inc Had The Following Balances in Its Short TermDokumen1 halamanSolved Finning International Inc Had The Following Balances in Its Short TermAnbu jaromiaBelum ada peringkat

- Junior Lawyer Resume PDF Free Download PDFDokumen3 halamanJunior Lawyer Resume PDF Free Download PDFAnubhav PandeyBelum ada peringkat

- Payoff Schedule Payoff Chart: NIFTY at Expiry Net PayoffDokumen2 halamanPayoff Schedule Payoff Chart: NIFTY at Expiry Net PayoffAKSHAYA AKSHAYABelum ada peringkat

- The Nigerian Tourism Sector and The Impact of Fiscal PolicyDokumen73 halamanThe Nigerian Tourism Sector and The Impact of Fiscal PolicyAttah Andung PeterBelum ada peringkat

- Case Study Finding WACC For A Project BoltaDokumen1 halamanCase Study Finding WACC For A Project BoltaebeBelum ada peringkat

- For MailDokumen2 halamanFor Mailmeenalmathur0100% (1)

- Supplements SLCMDokumen50 halamanSupplements SLCMAkshra MahajanBelum ada peringkat

- Major Assignment - FM303 PDFDokumen5 halamanMajor Assignment - FM303 PDFfrancisBelum ada peringkat

- The 5Ms of ManagementDokumen2 halamanThe 5Ms of Managementhani5275% (8)

- MY OGSE Catalogue 18' v4Dokumen138 halamanMY OGSE Catalogue 18' v4Mohamad HafizBelum ada peringkat

- Memorandum and Articles of A CompanyDokumen15 halamanMemorandum and Articles of A CompanyAllan HenryBelum ada peringkat

- GST Tax Invoice Format For Goods - TeachooDokumen2 halamanGST Tax Invoice Format For Goods - TeachooAshish Kamthania SaxenaBelum ada peringkat

- Bs Is Ratios - Azwan Family - SolutionDokumen3 halamanBs Is Ratios - Azwan Family - SolutionNatasya ShahrulafizalBelum ada peringkat

- Final Case Study 0506Dokumen25 halamanFinal Case Study 0506Namit Nahar67% (3)

- Agriculture Industrial SurveyDokumen52 halamanAgriculture Industrial SurveyanburishiBelum ada peringkat

- Probset #2 - Engineering EconomicsDokumen2 halamanProbset #2 - Engineering EconomicsKshatriya EllaBelum ada peringkat

- FordDokumen97 halamanFordbhaktishah117Belum ada peringkat