Change Management or Variation Management

Diunggah oleh

naveed566Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Change Management or Variation Management

Diunggah oleh

naveed566Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

40

Information Management

Variations in government contract

in Malaysia

&#'()*(+,"-./0,1(20(3(4#KT40@*65010#D:045#G:.:250:L

&# 567+, 8-8,97))-.,#KT40@*65010#D:045#G:.:250:L

&#Abdelnaser Omran#KT40@*65010#D:045#G:.:250:L

!"#$ %#&# ()*# +!,-.*/012# !3# +!45167+10!4# 8!695# ,*:45# 1):1# 01# 05# ):6;.2# -!550<.*# 1!# +!,-.*1*#

:#-6!=*+1#801)!71#+):4>*5#1!#1)*#-.:45#!6#1)*#+!45167+10!4#-6!+*55#015*.3"#()*6*#+:4#!4.2#<*#:#,04!6012#!3#

+!416:+15#!3#:42#50?*#04#8)0+)#1)*#57<=*+1#,:11*6#8)*4#+!,-.*1*;#05#0;*410+:.#04#*@*62#6*5-*+1#801)#8):1#

8:5#+!41*,-.:1*;#:1#1)*#!715*1"#A5#57+)B#@:60:10!45#:6*#04*@01:<.*#04#*@*4#1)*#<*51C-.:44*;#+!416:+15"#()05#

517;2#05#:11*,-1*;#1!#*/:,04*#1)*#8:25#:#@:60:10!4#8:5#3!6,*;#04#.:8#:4;#-6!=*+1B#04#304;04>#!71#8)*1)*6#

1)*#D1:4;:6;#E!6,#!3#F!416:+1#75*;#04#G:.:250:#-:610+7.:6.2#1)*#>!@*64,*41#H7<.0+#I!695#J*-:61,*41#

KHIJL#3!6,#):5#<**4#710.0?*;#1!#1)*#<*51#.*@*.#04#@:60:10!4#+:5*5"#A;;010!4:..2B#1)05#517;2#*/:,04*;#1)*#

<*4*3015#!3#@:60:10!45#1!#-:610*5#04#+!416:+1#:4;#:.5!#-6!@0;*5#57>>*510!45#:4;#:557,-10!45#04#:4#*33!61#1!#

+!4160<71*#5!.710!45#1!#0557*5#:4;#-6!<.*,#;*1*+1*;"#()*#6*5*:6+)#,*1)!;!.!>2#75*;#04#1)05#517;2#8:5#:4#

*/1*450@*#6*@0*8#!3#6*.*@:41#.01*6:176*B#+:5*#517;2B#*,-060+:.#M7*510!44:06*5#:4;#5167+176*;#041*6@0*85#:4;#

>*4*6:.#!<5*6@:10!45#<:5*;#!4#*/-*60*4+*#:4;#5766!74;04>5"#()*#:+:;*,0+#517;2#:--6!:+)#04+!6-!6:1*;#

51:>*5#57+)#:5#04010:.#74;*651:4;04>B#;:1:#:4;#043!6,:10!4#>:1)*604>B#:4:.2505#!3#;:1:B#304;04>5#:4;#+!4C

+.750!4#:4;#>*4*6:.#57>>*510!45#04#1)*#517;2"#()*#,:=!6#304;04>5#!3#1)05#517;2B#:,!4>#!1)*65B#6*@*:.*;#1):1#

1)*#*/051*4+*5#!3#@:60:10!45#:6*#+!,,!4#04#-6!=*+15"#()*#,:04#+:75*#!3#@:60:10!45#8:5#;7*#1!#+.0*41#6*M7*51#

<*+:75*#!3#04:;*M7:1*#-6!=*+1#!<=*+10@*5#3!6#1)*#;*50>4*6#1!#;*@*.!-#+!,-6*)*450@*#;*50>4"#N*50;*5B#1)*#:4:.C

2505#-!041*;#!71#1):1#1)*#>!@*64,*41#3!6,#!3#+!416:+1#1)*#H7<.0+#I!695#J*-:61,*41#KHIJL#%'OP%'OA#+:4#

)*.-#04#!@*6+!,04>#-6!=*+15#801)#@:60:10!4#<*+:75*#!3#1)*#+.*:6#;*304*;#-6!+*;76*"#()05#517;2#:.5!#3!74;#

1):1#-6!-*6#-.:4404>#:4;#+!!6;04:10!4#:1#1*4;*6#51:>*#+:4#,040,0?*#1)*#6059#!3#Q748:41*;R#@:60:10!45"#S4#

+!4+.750!4B#1)05#517;2#6*+!,,*4;*;#1):1#37176*#6*5*:6+)#5)!7.;#<*#;!4*#04#;*50>4#:4;#<70.;#<:5*;#+!416:+1#

:5#57+)#4*8#043!6,:10!4#5):604>#+:4#.*:;#1!#:4#*/-:450!4#1!#1)*#<!;2#!3#94!8.*;>*#!3#1)*#+!45167+10!4#04C

;75162#04#G:.:250:"#

Keywords: Variation, government contract, variation order, Penang, Malaysia.

!"#$%#&#%'$'

Information Management

1. Introduction

Use of the word variations in building contracts usually refers to a change in the

works instructed by the architect, contract administrator or the employer as the case maybe. Most standard forms of contract include a

clause under which the employer or his representative is able to issue an instruction to

the contractor to vary the works which are

described in the contract. A change in shape

of the scheme, the introduction of different

materials, revised timing and sequence are

all usually provided for by the variations

clause. It will also usually include a mechanism for evaluating the financial effect of the

variation and there is normally provision for

adjusting the completion date. In the absence

of such a clause the employer could be in a

difficulty should a variation to the works

be required and the contractor could not be

compelled to vary the works and he could insist upon completing precisely the work and

supplying precisely the material for which he

has contracted. No power to order variations

would be implied in such situation.

The complexity of construction works

means that it is hardly possible to complete

a project without changes to the plans or

the construction process itself. Construction

plans exists in form of designs, drawings,

quantities and specifications earmarked for

a specific construction site. Changes to the

plans are effected by means of a variation

order initiated by a consultant on behalf of

the client or as raised by the contractor. Legal

precedents, illustrate that variations date

back to time in memorial. While their occurrence is no longer an inconceivable issue, it

is their effect and subsequent management

41

that continues to challenge stakeholders of

projects to this day. This happens against a

background that over years, experience has

been gained to handle variations in form of

contract clauses and procedures, which define what constitutes a variation and how to

manage them. They continue to cause undue uneasiness to the stakeholders because

of their effect on the successful delivery of

projects in terms of cost, time, quality and

utility. Disputes and misunderstandings are

still encountered when variations arise, often

causing disruptions to the smooth running of

projects. This study is attempted to examine

the ways a variation was formed in law and

project, in finding out whether the Standard

Form of Contract used in Malaysia particularly the government PWD form has been

utilized to the best level in variation cases.

Additionally, this study examined the benefits of variations to parties in contract and

also provides suggestions and assumptions

in an effort to contribute solutions to issues

and problem detected.

2. Variation in Government Contract

There is no single definition of what

constitutes a variation. In general, the ever

famous guru of construction industry Prof.

Vincent Powell-Smith ascribes the followings

meaning to the term variation:

A42#+):4>*#1!#1)*#8!695#:5#;*1:0.*;#!6#;*C

5+60<*;#04#1)*#+!416:+1#;!+7,*415U"

On a broad-brush approach, following the above mentioned definition, there is,

prima facie, a variation every time there is

a departure from the work stipulated in the

!"#$%#&#%'$'

42

Information Management

contract. Whether such a variation is in law

strictly a variation with its attendant legal

consequences has to be established in relation

to the particular contract involved. Usually,

each standard forms of building contract will

contain a definition of a variation in terms of

specific actions and activities. As for the PWD

203/203A (Rev. 2007) Condition of Contract,

Clause 24.2 defines and stipulates that:

%V"%# ()*# 1*6,# QW:60:10!4R# ,*:45# :# +):4>*#

04#1)*#F!416:+1#J!+7,*41#8)0+)#4*+*5501:1*5#1)*#

:.1*6:10!4# !6# ,!;030+:10!4# !3# 1)*# ;*50>4B# M7:.012#

!6# M7:41012# !3# 1)*# I!695# :5# ;*5+60<*;# <2# !6# 6*C

ferred to therein and affects the Contract Sum,

04+.7;04>X

:L# 1)*#:;;010!4B#!,0550!4#!6#57<5101710!4#!3#

any work;

<L#1)*# :.1*6:10!4# !3# 1)*# 904;# !6# 51:4;:6;#

!3# :42# !3# 1)*# ,:1*60:.5B# >!!;5# 1!# <*# 75*;# 04# 1)*#

Works; or

+L# 1)*#6*,!@:.#36!,#1)*#D01*#!3#:42#8!69#*/C

*+71*;# !6# ,:1*60:.5#!6# >!!;5# <6!7>)1# 1)*6*!4# <2#

the Contractor for the purposes of the Works other

1):4#8!69B#,:1*60:.5#!6#>!!;5#8)0+)#:6*#4!1#04#:+C

cordance with this Contract.

Fong (2004) defines Clause 24.2 by explaining that the meaning of variation for

the purpose of the Contract as the alteration

or modification of the design, quality and

quantity of Works shown upon the Contract

Drawings, Bills of Quantities and/or the

Specification. It also includes the addition,

omission or substitution of any work, alteration of the kind or standard or any of the materials or goods to be used for the Works and

the removal off the Site of any work, material

or goods executed or brought to the site expect if the work, material or goods are not in

accordance with the Contract.

3. Variations and variation orders

Any deviation from an agreed welldefined scope and schedule can be called as

variations. Stated in a different way, this is

a change in any modification to the contractual guidance provided to the contractor by

the owner or owners representative. This includes changes to plans, specifications or any

other contract documents. A variation order

is the formal document that is used to modify the original contractual agreement and

becomes part of projects documents (Fisk,

1997; OBrien, 1998). Furthermore, a variation order is written order issued to the contractor after execution of the contract by the

owner, which authorize a change in the work

or an adjustment in the contract sum or even

the contract time (Clough and Sears, 1994).

For a variation to be tenable at law, it must be

valid in the first place. Unless such a change

meets the validity test, the contractual consequences ensuing thereof cannot arise and accordingly cannot be enforced. Therefore, the

contractor cannot be compelled to comply

with any variation order issued and he on his

part may not be able to recover his contractual entitlements as to additional costs and/

or time, for instance. It is hence apparent that

the central issue of validity forms the essence

of a contractually tenable and therefore enforceable variation; a matter that continues

to generate disputes in many a contract in

the engineering and construction industry.

According to Harbans Singh (2002), when

one classifies a variation as valid, the fundamental reference is in terms of posing the

question: whether the change has been carried out in compliance with a valid variation

order or not? The term variation order in turn

has no magical meaning but its precise ambit

!"#$%#&#%'$'

Information Management

must be appreciated to ensure that the elements of validity are not compromised. Prof

Vincent Powell-Smith in relation to engineering contracts which holds a variation order

to be:

A4# 045167+10!4# !3# 1)*# *4>04**6# 1!# *33*+1# :#

+):4>*# 1!# 1)*# 8!695# :5# ;*304*;# 04# 1)*# +!416:+1##

documents, it is commonplace for a variation simC

-.2#1!#<*#0557*;#:5#:4#*4>04**6R5#045167+10!4Y#01#<*C

04>#*@0;*41#36!,#1)*#+!41*41#1):1#01#05#:#@:60:10!4"#

Alternatively, variations are issued separately on

variation orders.

The principal elements of a valid variation order outlined by Harbans Singh (2002)

are, a variation must be in the form of an instruction in the formal/contractual sense.

Secondly, the person issuing the instruction

must be the contract administrator or the person empowered under the contract to issue

such instruction. Third principle is the instruction must effect a change to the works

and forth is the works being changed or varied must be spelt out or defined in the contract documents. Fong (2000) in Law and

Practice of Construction Contract Claims

identifies two main factors determining the

validity of a variation order. First, the legal nature of the proposed change, i.e. contract conditions governing variations and

the common law rules governing the scope

of change. Second the formalities governing

the change, e.g. issue of the variation order

by the designated person and the applicable

procedural requirements. Fong (2000) explains further that under contract conditions

governing variations, it is settled law that a

contractually valid variation order can only

be issued if there is a term in the contract permitting the same and strictly in accordance

43

with this term. Should there be no such term

or that the provisions of an existing term be

not complied with, any variation order thereupon issued may, for all intents and purposes, be invalid and therefore unenforceable.

To cater for the eventuality of permitting

such variations to be effected, most if not, all

the standard forms of conditions of contract

have incorporated express stipulations in the

conditions of contract. In the rare situation of

the absence of such an express stipulation in

the contractor it being rendered invalid/unenforceable, the parties have only a number

of alternatives available to them; one of these

being to enter into a supplementary agreement to enable the varied work as envisaged

to be carried out. To preclude such a situation from arising and to obviate its attendant

complications, it is necessary for the parties

to ensure that not only the relevant express

provisions are included in their contract from

the very outset but these are religiously adhered to in the implementation stage. Under

the second factor of determining validity of

a variation order, Fong (2000) explains, for a

variation order to be upheld as contractually

valid, one of the main requirements is that

it must be issued by the person empowered

under the contract to effect the same. Such a

body or person might be:

a) The employer himself; or

b) The contract administrator; or

c) Any other body or person designated

in the contract or authorized expressly under

the contract.

The body or person so designated can

be either named in the contract or empowered through a formal letter of delegation of

power issued after award of the contract during the currency of the contract. The above

requirement is neatly summed up in the following words by Robinson and Lavers:

!"#$%#&#%'$'

44

Information Management

()*#*,-.!2*6B#74;*6#:..#51:4;:6;#3!6,5B#05#

6*M706*;#1!#*/*6+05*#)05#60>)1#1!#+):4>*##1)*#+!4C

16:+1!6R5# !<.0>:10!45B# 1)6!7>)# 1)*# :>*4+2# !3# 1)*#

:6+)01*+1# K!6# *4>04**6# !6# 57-*6@050!4# # !330+*6L"#

()*# +!416:+1!6# 05# >*4*6:..2# 74;*6# 4!# !<.0>:10!4#

to accept instructions direct from the employer

*/+*-1# 74;*6# 5!,*# >!@*64,*41:.# 3!6,5# 8)*6*#

57+)#:#60>)1#!3#;06*+1#+!,,740+:10!4#05#6*1:04*;#

3!6# 6*:5!45# !3# 4:10!4:.# 5*+76012"# ()*# 75*# !3# 1)*#

:6+)01*+1#:5#:>*41#04#1)05#+!41*/1#05#4*+*55:62#!3#

+!765*#1!#*4576*#+!!6;04:10!4#!3#1)*#;*50>4B#1!#*4C

576*#51:4;:6;0?*;#:;,040516:10@*#-6!+*;76*5#:4;#

<*+:75*B#04#,!51#+:5*5B#1)*#04010:1!6#!3#1)*#+):4>*5#

05#1)*#:6+)01*+1#)0,5*.3#:5#)05#;*1:0.*;#;*50>4#8!69#

-6!>6*55*5"

As can be distilled from the above extract, in most contracts, this power is delegated to the contract administrator, i.e. the

Architect in the PAM Forms, Engineer in

the IEM Forms, Employers Representatives

in the Putrajaya Forms, etc. It is pertinent to

note that once the contract designates a specific person as the official who is empowered

to vary the works or a specific person is delegated this duty, a variation order issued by

any other person will not be contractually

valid. Furthermore according to Robinson &

Lavers (1988), in exercising this power, the

contract administrator must ensure that the

said power meets the following criteria:

It covers the nature of the variation or

change ordered;

Covers the extent of the variation or

change envisaged; and

It meets any express time limit prescribed for exercising such powers, e.g.

whether the contract permits variation orders to be issued after practical completion of

work, etc.

The following characteristics and/or

features of the power of the contract administrator to vary works should also be considered according to Harbans Singh (2002). The

characteristic are, the employer may (either

in the contract or the letter of delegation of

powers) subject the exercise of the said power to certain procedural and/or financial limitations, e.g. in Public Works Contracts, the

prior consent of the employer may be a prerequisite to the contract administrators issuing any variation orders. Where the contract

administrator is empowered under the contract to vary the works, his use of such power

as the employers agent is for the purpose of

the contract purely discretionary:# *!;!/#Z1;#

@#()*#N!6!7>)#!3#D8041!4#[#H*4;.*<762" Second

characteristics will be a person who is designated as the party empowered to issue variation orders is not obliged to exercise the said

power fairly as the said power is normally

only for the benefit of the employer and the

person exercising such power is acting as the

latters agent: J:@2# \335)!6*# @# ],*6:.;# E0*.;#

F!416:+104>. As an overview, the contract administrator must be mindful not to exceed his

real or ostensible authority or act beyond the

powers vested in him under the contract or in

his professional services agreement. Should

such an eventuality occasion, he may be culpable of acting ultra vires with such possible

consequences of rendering any variation order issued invalid and/or exposing himself to

claims of breach of contract or negligence by

the employer. According to Fish (1997), there

are two basic types of variations: directed and

constructive changes, which are discussed in

detail below:

:;,<-4=23=6,%0(./=),

Directed changes are easy to identify. A

directed change occurs when the client directs

!"#$%#&#%'$'

Information Management

the contractor to perform works that are different from the specified in the contract or

an addition to the original scope of work. A

directed change can also be deductive in nature, that is, it may reduce the scope of work

called for in the contract. Disagreements tend

to center on questions of financial compensation and the effect of the change on the construction schedule for directed changes.

::;,%>.)34723-?=,%0(./=),

A constructive change is an informal act

authorizing or directing a modification to the

contract caused by an act or failure to act. In

contrast to the mutually recognized need for

change, certain acts or failure to act by the client that increases the contractors cost and/or

time of performance may also be considered

grounds for a variation order. This is termed

as a constructive change and must be claimed

in writing by the contractor within the time

specified in the contract documents in order

to be considered.

@;A?(+7(3-./, 30=, .==6, >B, ?(4-(3->.,

orders

The usage of a variation order is to effect a change in the contract. As mentioned

previously, such changes should always be

in writing to avoid unnecessary disputes

among the owners and the contractors. The

following are some of the purpose served by

variation orders (Fisk, 1997):

1. To change contract plans or to specify the method and amount of payment and

changes in contract time there from.

2. To change contract specifications,

including changes in payment and contract

time that may result from such changes.

3. To effect agreements concerning the

order of the work, including any payment or

changes in contract that may result.

45

4. For administrative purpose, to establish the method of extra work payment

and funds for work already stipulates in the

contract.

5. For administrative purposes, to authorize an increase in extra work funds necessary to complete previously authorized

change.

6. To cover adjustments to contract unit

prices for overruns and under runs, when required by the specifications.

7. To effect cost reduction incentive proposal (value engineering proposals).

8. To effect payment after settlement of

claims.

A variation order is used in most instances when a written agreement by both

parties to the contract is either necessary or

desirable. Such use further serves the purpose of notifying a contractor of its right to

file a protest if it fails to execute a variation

order (Fisk, 1997). The absence of a variations clause undoubtedly makes it difficult

to vary the terms of the contract but it is at

least possible that the courts would imply a

term allowing minor variations to be made.

In any event, it would of course be most unusual for a contractor to attempt to refuse to

carry out small changes and even less likely

that the contractor would go to court over an

attempt to impose them. By inserting a clause

which allows for changes to be made to the

works as they are being built, the employer,

through the contract administrator, can alter the works as and when necessary. The

purpose of the variation clauses is to allow

such changes to be made, and also to permit any consequential changes to be made

to the contract sum. Furthermore according

to Murdoch & Hughes (1996), it is always

!"#$%#&#%'$'

46

Information Management

possible for a contract to include a clause that

fixes express limits on the amount of variations. In any event, it must be borne in mind

that the existence of a variation clause does

not entitle the employer to make large scale

and significant changes to the nature of the

works, as these are defined in the recitals to

the contract. In particular, variations which

go to the root of the contract are not permissible. If the recitals state that 8 dwelling houses

are to be built, then a variation altering this to

12 would possibly be constructed as going to

the root of the contract. However, if the recitals state that the contract is for 1008 houses,

then a variation changing this to 1012 would

not go to the root of the contract, because it

would be a minor change in quantity. If the

quantity of work is not indicated in the recital, then the question does not arise in the

same way. What is probably more important

is that if the contract is for the erection of a

swimming pool, a variation which attempts

to change it to a house would clearly be beyond the scope of the contract. There are two

classic cases to explain the above statement.

The first case is in Blue Circle Industries Plc

v Holland Dredging Company (UK) Ltd the

parties entered into a contract under which

the defendants were to dredge a channel

which served the plaintiffs dicks in Lough

Larne, Eire. The dredged material was to be

deposited in areas of Lough Larne to be notified by the local authority. When the plaintiffs instructed the defendants instead to use

the dredged material so as to construct an

artificial island, it was held that this could

not be regarded as a variation. It was beyond

the scope of the original contract altogether,

and thus had to form a separate contract. In

McAlpine Humberoak Ltd v Mc Dermott

International Inc, on the other hand, the

plaintiffs entered into a sub-contract for the

construction of part of the weather deck of a

North Sea drilling platform. The documents

on which the plaintiffs tendered include 22

engineers drawings. However, when work

began, a stream of design changes transformed the contract into one based on 161

drawings. The trial judge ruled that these

changes were so significant as to amount to

a new contract, but the Court of Appeal held

that they could all be accommodated within

the contractual variation clause.

5.0 Potential Effects of Variation

Orders

Research on the effects of variation orders were done by many researchers (Clough

and Sears, 1994; Thomas and Napolitan,

1995; Fisk, 1997; Ibbs, 1997; Veenendaal,

1998; Reichard and Norwood, 2001; Arain

and Low, 2005; Moselhi et al., 2005). Changes

that occur during construction will affect any

project (Reichard and Norwood, 2001). Lewis

(1991) indicated that change orders have its

ripple effects as a contractor does not work

in a vacuum; rather must properly allocate

his limited resources within projects and between actual and potential projects. Thus,

whenever a change occurs, a contractor must

make adjustments to work under the contract

and reallocate time, material and labour resources. Arain and Low (2005) identified 16

potential effects of variation orders on institutional building from the research they did

in Singapore. The effects that were determined are discussed further below.

C;D, E4>/4=)), -), BB=23=6, 573, F-30>73,

any Delay

Project progress and quality may be affected by variations (Arain and Low, 2005).

During construction, time is of the essence.

!"#$%#&#%'$'

Information Management

However, according to Arain and Low

(2005), only major variations during the project may affect the project completion time

because the contractor would usually try

to accommodate the variations by utilizing

the free floats in the construction schedules.

Therefore, variations will affect the project

progress but without any delay in the project

completion date.

5.2 Increases in Project Cost

During the construction phase, the most

common effect of variations is the increase

in project cost (CII, 1990). The increase in the

project cost is caused by any major additions

or modifications to the design (Clough and

Sears, 1994). Therefore, contingency sum will

usually be allocated in every construction

project to cater for any possible variations in

the project, while keeping the overall project

cost intact.

5.3 Hiring New Professionals

CII (1995), variations often occur in

complex technologies projects, this may be

caused by something was overlooked by

the architect/engineer during the design

stage. Complex technologies projects need

specialists to get the job done (Fisk, 1997).

Depending on the nature, occasionally, new

professional need to be hired or the entire

project team is replaced to execute the variations (Arain and Low, 2005). Hiring the new

professionals takes time and thus affecting

the project progress.

C;@,:.24=()=),-.,G?=40=(6,AH*=.)=,

Variations need to go through a few

stages of processing procedures as mentioned earlier and require to be evaluated before they can even be implemented (OBrien,

47

1998). Because of this, the overhead expense

for all the parties involved will increase as

there is a lot of work and paperwork need to

be done. However, normally these overhead

charges are provided for from the contingency fund allocated for the construction projects (Arain and Low, 2005).

5.5 Delays in Payment

Delay in payment occurred frequently due to variations in construction project

(CII, 1990). CII (1995), variations may hinder the project progress as mentioned before

thus leading to delays in the construction

works done which will eventually affecting payments to the contractors. If the main

contractor does not have enough funds to

pay the subcontractors then this may cause

severe problem to both the main contractor and the subcontractor as well. This can

happen because some main contractor depends on the payment from client to pay the

subcontractors.

5.6 Quality Degradation

Frequent variations may affect the quality of work adversely (Fisk, 1997). This maybe because of frequent variations may cause

the contractors to compensate their losses by

cutting corners.

5.7 Productivity Degradation

Variation orders often associated with

interruption, delays and modification of

work do have a negative impact on labor

productivity. Hester et al., (1991) feel that the

productivity of workers was expected to be

seriously affected in cases where they were

required to work overtime for prolonged

periods to compensate for schedule delays.

Thomas and Napolitan (1995) concluded

!"#$%#&#%'$'

48

Information Management

from their research that variations normally led to disruptions and these disruptions

were reasonable for labor productivity degradation and on average, there is a 30 percent

loss of efficiency when changes are being performed. Thomas and Napolitan (1995) also

feel that the most significant types of disruptions were due to the shortage of materials

and lack of information as well as the work

out of sequence and these disruptions result

in daily loss of efficiency in the range of 25

to 50 percent. Reichard and Norwood (2001)

found out from their research that if variations reach 10 to 15 percent of the originally

planned labor hours, productivity of the remaining unchanged work will decreased due

to the extra labor hours spent on executing

the variations. According to Moselhi et al.,

(2005) the few factors that were found to influence the impact of variation orders on labor productivity are as follows:

,I;J,$=)=(420,K=30>6>+>/L

Systematic research method is important to get good research result. Research system that is reliable has to be used so that the

objectives that were lineout above will bare

result.

6.1 Data Collection

Data collection was carried out through

primary and secondary sources. As for primary data, the data shall be acquired through

case study, questioners, observation, structured interviews (both contractor and clients).

The scope of case study and questioners distribution shall be confined to Penang. The secondary data shall be acquired from library,

resource center, Government Departments,

lectures, Internet and other sources. As an illustration, secondary data shall be obtained

from references books, newspaper, journals

and other printed materials. This is important since appropriate and relevant data and

information related to the study is necessary

prior to a detailed analysis. For the purpose

of this study, the researcher developed a

structured interview-based questionnaire.

The purpose of such method was primarily

to gather data relating to the research objectives in this study. Among the relevant questions asked include the cause of variations in

a project, the forms of contract involved and

procedures or steps undertaken when there

is a variation.

6.2 Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire in this study consisted of two segments; basically Segment A

and Segment B. Segment A consisted of information related to the demographic data

of the respondents. Among the variables in

this section include, age, gender, years of experience and profession of the respondent.

In Segment B, questions posed were related

to the research paper, and included items on

awareness in construction contract variation,

the frequency of such variations, the cause of

variations in a project and the procedures taken when there is a variation in a project. The

questionnaire items, particularly related to

the area of study, were formulated based on

an extensive literature review and frequent

discussions with the supervisor of the study.

After some review and amendments, a final

copy of the questionnaire was produced.

6.3 Questionnaire Distribution

A total of 50 questionnaire forms were

distributed to selected respondents in the

construction industry mainly operating in

the northern state of Malaysia, Penang. The

!"#$%#&#%'$'

Information Management

method used by the researcher in the distribution was on a personal contract-basis. In

this method, the researcher himself went to

meet the respondents and provided them

with a copy of the questionnaire. The technique used in data collection was a drop

and pick-up technique. In this technique,

respondents were given the questionnaire

and told that the completed questionnaire

shall be picked up the next day. The questionnaires in this study were distributed on

28th December 2009 to 28th January 2010. 15

of the respondents returned the completed

questionnaire on the same day. There were a

few cases when the researcher was informed

that the completed questionnaire shall be returned the next day. However, this did not

happen. Although the initial plan, as stated earlier, was to collect the questionnaires

from the respondents the next day; however

it was different in practice. Some 10 respondents took more than one day to send in

their responses and another 5 respondents

took 14 days to reply. Although the respondents were reminded via a telephone call

and through personal contact, the researcher

did not receive the completed questionnaire.

Thus, most probably, either the respondent

would had misplaced the questionnaire, or

changed his (her) mind about participating

in the study.

7. Results Analysis

In analyzing the detailed information

based on questionnaire in this study, it further reinforces the existences of variation as

a common occurrence in a typical project.

When the respondents in this study were

asked if variation were common in projects

thru their working experience, 97% of the

49

responders answered yes. This study confirms that the reasons of variation offered by

respondents were in lined and seems to fit the

literature review. From the many reasons or

causes of variation the single most frequent

cause of variation was client request (21%).

Results from the questionnaire study seem to

support the case study findings in the sense

that the second highest contributor of variation for Balai Bomba Kepala Batas, Penang

was due to client request. Example of variation due to client request is change of plan

or scope of project, inadequate project objectives and many more. Under the case study

of this research the reason of variation is due

to inadequate project objectives that result in

the designer unable to develop a comprehensive design which leads to numerous variations during the project construction phase.

With reference to the procedures be taken

when there is a variation in a project, it was

observed among the procedures followed

were checking with the relevant contract and

drawings to establish and valid variation and

then gather information to produce an estimate and brief clients on the financial impact

of the variation, issue SO instruction to contractor for changes, verify estimated cost and

whether cost is treated as variation (addition/

omission) and finally owners approval for

variation to be carried out. Basically, the procedures taken when there is a variation are

relatively same in process. These procedures

are affirmed in the researcher literature review by Harbans Singh (2002) explaining

that most of the standard forms of construction contract provide some basis procedures

or rule for variation works. The rules are

often similar in principle. Either its private

sector of government sector standard form

!"#$%#&#%'$'

50

Information Management

of contract the producers on how to identify a variation, measurement of variation,

valuation and also payment of varied work

are outlined in detail in these forms.

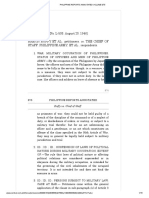

Figure 1: What are causes of variations in a project?

35%

30%

29%

25%

20%

15%

10%

21%

15%

14%

9%

7%

5%

er

s

O

th

ho

rit

ie

s

si

te

D

is

co

cr

ns

ep

tra

an

in

ci

ts

es

&

am

bi

gu

iti

In

es

co

m

U

pl

nf

et

or

e

&

es

ee

in

n

ad

eq

ua

te

de

si

gn

A

dj

us

tm

en

td

ue

to

lie

A

ut

nt

re

q

ue

st

5%

0%

With reference to the second objective

of this study, majority (87%) of respondents

agreed that PWD standard form of contract

can help them in overcoming a project that

has variations. Some of the reasons outlined

by respondents on how the standard form of

contract helps in variation were, the variation clause clearly defines what variation

is. Some respondents agreed that the PWD

form provides a framework and spells out

the necessary steps/ procedures needed for

both parties (client and contractor) in terms

of responsibilities, scope, obligations of the

parties concerned. On the other hand, some

respondents (13%) did not agree that PWD

form of contract could help them in overcoming a project with variations. Among reasons

given were, conditions are vague, incomplete

and difficult to implement effectively. Some

even argued that it does not overcome projects with variation but only provides good

procedures and fair to both parties. Referring

to the case study, the form of contract used for

the project was PWD 203A. Based on the researcher findings, the form of contract helped

and gave an explicit guide to the contract administrator in deciding, valuating, issuing

and even in rejecting some variation claimed

by the project contractor. Undoubtedly PWD

form of contract and it clauses has the clarity

in dealing with variation procedures and this

is an integral part of effective management

of variation. The procedures in this form are

clear to all parties and would help in reducing

variations. Furthermore the comprehensive

and balanced variation clauses in PWD form

would help in improving coordination and

reduce conflicts that can result in problems

and misinterpretation. Generally, supported

with the outcome and result of the study and

observation by the researcher it can be concluded that PWD form can and does help in

overcoming projects with variations. In discussing the ways towards, minimizing the

!"#$%#&#%'$'

Information Management

risk of unwanted variations, the soundest

proposal in this study is to have proper planning and coordination at tender stage. It is

in tandem with the Japanese policy that 80%

of effort and time should be in the planning

stage and the other 20% in implementation

stage. As contract documents and drawings

51

are the main source of reference and information, good coordination and involvement of

all professional parties and even the client is

important in developing creative and practical ideas that minimize discrepancies and resulting in reduced variation.

Figure 2: !"#"$"%& '(& )"*+ ,- ./#01#'&23 415"1'",#*6

Firm project brief

15%

18%

Planning & coordination

at tender stage

Others

67%

The involvement of the owner in the

design phase would assist in clarifying the

project objectives and in identifying the

noncompliance with their requirements at

an early stage. The controls for the errors

and omissions in design, design discrepancies and frequent change in design, would

be through detailing of design. Thorough

detailing of design was perceived as one of

the most effective controls for variation. This

process would assist in identifying the errors

and ambiguities in design and help in elevating variations. Involvement of professionals

at initial stage can assist in developing better

and practical designs. Another suggestion in

minimizing the risk of unwanted variation

is to have clear and complete project brief. It

helps in controlling variations as it helps in

clarifying the project objectives to all parties.

In my own view, variations must be kept to a

minimum so that it is possible for all works to

be completed by the original stipulated completion date. The study recorded a mixture

of responses whether organization benefited

or not from variation. With 37% respondents

agreeing it benefited them, where else 47%

disagree variations can benefit and the balance 16% both agree and disagree depending

on situation. In my observation, the question

of benefit or not depends on what type of

scenario does a variation incurred. Most contractors and consultants response was if it is

an additional variation than it benefited them

in terms of increase in contract sum and higher profits (for contractor) and higher percentage of fees for consultants but not beneficial

if a variation resulted in an omission. In the

researchers own point of view, variation is an

instrument to facilitate change in a contract

and it is not for any parties to misuse or make

profits or even lose profits from it. Some of

the views or comments expressed by respondents among others were, there is no such

thing as a variation free contract and any attempt towards this phenomena is an exercise

in complete futility. We all know variations

are the necessary evil in the construction industry that cannot be avoided but should be

!"#$%#&#%'$'

52

Information Management

managed or maybe minimized thus there is

no such thing as a complete and perfect contract. Analysis of detailed information in the

case study revealed that there were variation

with additional cost and some variation with

omission (reduction in cost). It was observed

that variation is a normal and common scenario in any typical construction project as

supported by literature review. The primary

reason for such a case study is to provide a

practical and workable scenario closely related to variation. It can be concluded that

the case study is in tandem and supports the

literature review and questionnaire analysis

done in this study.

Figure 3: Do you think your organization Get some benefits from variations?

16%

37%

Yes

No

Both

47%

8. Conclusions

As a conclusion, considering the fact

that variations are common in all types of

construction project, it is hoped that this

research can be used as a guide by professionals to reduce and control variations in

projects. Although variations are frequently

unavoidable in the construction industry,

unwanted or negative variations are undesirable in projects as these would have an adverse impact on time, cost and quality. The

study also suggests that the management of

variation must begin from the planning stage

and continue through the end of the project.

Finally, the overall objectives of this study,

as set out in above have been successfully

achieved. It is most important to research

findings and information generated shared

among professionals in the construction industry. Undoubtedly, such information sharing leads to an expansion to the body of

knowledge in dealing with both theoretical

and practical, the legal aspects and related

areas of variation.

REFERENCES:

!"Arian, F.M. and Low, S.P. (2005). !"#!$%&'()#*#%$)$*!(+,(-#"&#!&+*(+".$"/(,+"(&*/!&!0!&+*#1(20&1.&*%/3(4$-$"#%5

&*%(+*(&*,+")#!&+*(!$'6*+1+%7. Project Management Institute. 36 (4), 27-41.

!"CII. (1990). 86$(&)9#'!(+,('6#*%$/(+*('+*/!"0'!&+*('+/!(#*.(/'6$.01$, Construction Industry Institute, University of Texas, Austin, USA.

#!" !"#$%&'()*) and Sears, G.A. (1994). :+*/!"0'!&+*('+*!"#'!&*%;(<=!6($.&!&+*>, New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

$!"Fisk, E.R. (1997). :+*/!"0'!&+*(?"+@$'!(A.)&*&/!"#!&+*;(<B!6($.&!&+*>, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

%!"Fong, C.K. (2000). 4#C(D(?"#'!&'$(+,(:+*/!"0'!&+*(:+*!"#'!(:1#&)/. Singapore: Longman.

&!"Fong, L.C. (2004). 86$(E#1#7/&#*(?FG(H+")(+,(:+*/!"0'!&+*(:+*!"#'!. Malaysia: Sweet & Maxwell Asia.

!"#$%#&#%'$'

Information Management

53

'!"*+,-+./'01.$%&'2)0) (2002). O*%&*$$"&*%(D(:+*/!"0'!&+*(:+*!"#'!/(E#*#%$)$*!(P(?+/!(:+))$*'$)$*!(?"#'5

tice. Malaysia: Lexis Nexis Asia.

(!"*3/43,&'5)&'2#6,3.+/&'7)8. and %+.$&'9) . (1991). :+*/!"0'!&+*('6#*%$/(#*.('6#*%$(+".$"/3(86$&"()#%*&5

tude and impact, University of California, Berkeley, CA.

)!":--/&' )5) (1997).(Q0#*!&!#!&-$(&)9#'!/(+,(9"+@$'!('6#*%$3(/&R$(&//0$/J Journal of Construction Management

and Engineering, 123, (3), 308-311.

*+!";"/3!%1&'<)&'8//3=&':. and El-Rayes, K. (2005). :6#*%$/(+".$"/(&)9#'!(+*(1#2+0"(9"+.0'!&-&!7J Journal of

Construction Engineering and Management, ACSE, 131, (3), 354-359.

**!";#,>"?%&'7. & *#$%3/&'5) (1996). :+*/!"0'!&+*(:+*!"#'!/(<4#C(D(E#*#%$)$*!>(L*.(O.&!&+*J London:

E & FN Spon.

* !"OBrien, J.J. (1998). :+*/!"0'!&+*('6#*%$(+".$"/J New York: McGraw- Hill.

*#!"Public Works Department (2007). PWD 203A/203 Standard Form of Contract.

*$!"Rajoo, S. (1999). 86$(E#1#7/&#*( !#*.#".(H+")(+,(S0&1.&*%(:+*!"#'!(<86$(?AE(KTTU(H+")>(L*.(O.&!&+*J(Malaysia: Lexis Nexis.

*%!"(31?%+,>&' @)@)' and Norwood, C.L. (2001). A*#17R&*%( !6$( '0)01#!&-$( &)9#'!( +,( '6#*%$/J( AACE International Transactions.

*&!"Robinson, N. M., & Lavers, A.P. (1988). :+*/!"0'!&+*(1#C(&*( &*%#9+"$(D(E#1#7/&#J (Butterworth-1991).

Pg. 46-56, pg.86-102.

*'!"T%"=+/&'*)()&'and Napolitan, :J4J(Q0#*!&!#!&-$($,,$'!/(+,('+*/!"0'!&+*('6#*%$/(+*(1#2+0"(9"+.0'!&-&!7J(Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 121, (3), 290-296, 1995.

*(!"Veenendaal, J.A. (1998). A*#17R&*%(!6$(&)9#'!(+,('6#*%$(+".$"/(+*(#(/'6$.01$J(Journal of Cost Engineering,

40, (9), 33-39.

I+J(KL(M(LNKN

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Fire Safety in The Design, Management and Use of Buildings - Code of PracticeDokumen23 halamanFire Safety in The Design, Management and Use of Buildings - Code of Practicevikaspisal64% (11)

- Construction Claims and ResponsesDokumen6 halamanConstruction Claims and Responsesnaveed56667% (6)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- FSED 54F Affidavit of Undertaking (For Extension of Period of Compliance) Rev00Dokumen2 halamanFSED 54F Affidavit of Undertaking (For Extension of Period of Compliance) Rev00Talaingod Firestation100% (2)

- PVL2601 Study NotesDokumen24 halamanPVL2601 Study Notesmmeiring1234100% (5)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Bank of America Credit Committee CharterDokumen1 halamanBank of America Credit Committee CharterSebastian PaulBelum ada peringkat

- Class Writing Complete 1st TermDokumen13 halamanClass Writing Complete 1st Termnaveed566Belum ada peringkat

- SMP Template As of 24 March - 1Dokumen33 halamanSMP Template As of 24 March - 1naveed566Belum ada peringkat

- I I I I I: Key Experience and BackgroundDokumen4 halamanI I I I I: Key Experience and Backgroundnaveed566Belum ada peringkat

- 5A&B Dalvi LS Final Presentation Nov-2014Dokumen21 halaman5A&B Dalvi LS Final Presentation Nov-2014naveed566Belum ada peringkat

- Finance Interest Rates For BusinessDokumen22 halamanFinance Interest Rates For Businessnaveed566Belum ada peringkat

- Dummy Certificate - Sample DocumentDokumen1 halamanDummy Certificate - Sample Documentnaveed566Belum ada peringkat

- F107ECODokumen3 halamanF107ECOnaveed566Belum ada peringkat

- HSE Monthly Statisctical Report February 2016Dokumen2 halamanHSE Monthly Statisctical Report February 2016naveed566100% (2)

- Sabah Al-Salem University City - Kuwait UniversityDokumen1 halamanSabah Al-Salem University City - Kuwait Universitynaveed566Belum ada peringkat

- Affidavit of Loss - Bir.or - Car.1.2020Dokumen1 halamanAffidavit of Loss - Bir.or - Car.1.2020black stalkerBelum ada peringkat

- Vishwesha Kumara.1FF Player Voice - Part-Time - Contractor Employment Agreement - 1FFDokumen12 halamanVishwesha Kumara.1FF Player Voice - Part-Time - Contractor Employment Agreement - 1FFdcfl k sesaBelum ada peringkat

- Criminology - Topic 1: Crime StatisticsDokumen12 halamanCriminology - Topic 1: Crime StatisticsravkoonerBelum ada peringkat

- March 1, 2010, Watertown City Council Agenda PackageDokumen104 halamanMarch 1, 2010, Watertown City Council Agenda PackageNewzjunkyBelum ada peringkat

- Obligations and ContractsDokumen38 halamanObligations and ContractsDonn Henry D. PlacidoBelum ada peringkat

- For Volume Discounts Call 1-888-282-0447Dokumen6 halamanFor Volume Discounts Call 1-888-282-0447anon-573186Belum ada peringkat

- Unified Audit StrategyDokumen8 halamanUnified Audit StrategyvangieBelum ada peringkat

- Philippine Airlines, Inc. vs. Jaime M. Ramos, Nilda RamosDokumen10 halamanPhilippine Airlines, Inc. vs. Jaime M. Ramos, Nilda RamosAngelReaBelum ada peringkat

- Group 4 - System of Government in The American Period PDFDokumen11 halamanGroup 4 - System of Government in The American Period PDFDominique BacolodBelum ada peringkat

- Cs Ins 05 2021Dokumen2 halamanCs Ins 05 2021Sri CharanBelum ada peringkat

- National Housing Authority v. Grace Baptist ChurchDokumen4 halamanNational Housing Authority v. Grace Baptist ChurchMarchini Sandro Cañizares KongBelum ada peringkat

- Msds UMBDokumen9 halamanMsds UMBDwi April YantoBelum ada peringkat

- DPC ProjectDokumen15 halamanDPC ProjectAdityaSharmaBelum ada peringkat

- 4Th Nuals Maritime Law Moot Court Competition, 2017: in The Permanent Court of ArbitrationDokumen27 halaman4Th Nuals Maritime Law Moot Court Competition, 2017: in The Permanent Court of ArbitrationAarif Mohammad BilgramiBelum ada peringkat

- Rockland Construction v. Mid-Pasig Land, G.R. No. 164587, February 4, 2008Dokumen4 halamanRockland Construction v. Mid-Pasig Land, G.R. No. 164587, February 4, 2008Charmila Siplon100% (1)

- Principal of Severability PDFDokumen1 halamanPrincipal of Severability PDFShashank YadauvanshiBelum ada peringkat

- Abci V Cir DigestDokumen9 halamanAbci V Cir DigestSheilaBelum ada peringkat

- Ruffy vs. Chief of Staff, 75 Phil 875Dokumen15 halamanRuffy vs. Chief of Staff, 75 Phil 875April Janshen MatoBelum ada peringkat

- Petron CaseDokumen3 halamanPetron CaseKara Aglibo100% (1)

- Roxas Vs GMADokumen2 halamanRoxas Vs GMALou StellarBelum ada peringkat

- Esmalin vs. NLRC DIGESTDokumen2 halamanEsmalin vs. NLRC DIGESTStephanie Reyes GoBelum ada peringkat

- Admin Law Syllabus PDF SelectaDokumen11 halamanAdmin Law Syllabus PDF SelectaMichael C� Argabioso100% (1)

- C. Contemporar Y Construction: Group 3Dokumen18 halamanC. Contemporar Y Construction: Group 3Kurt Ryan JesuraBelum ada peringkat

- Business Law Text and Exercises 8th Edition Miller Test BankDokumen21 halamanBusiness Law Text and Exercises 8th Edition Miller Test Bankrubigoglumalooim4100% (27)

- Assessment Task I - Australian International Destinations v2 2018Dokumen38 halamanAssessment Task I - Australian International Destinations v2 2018Diana Maria Ramirez DiazBelum ada peringkat

- United States Court of Appeals Third CircuitDokumen20 halamanUnited States Court of Appeals Third CircuitScribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat