Ghaisal Train Accident 2002

Diunggah oleh

Kanagaraj GanesanHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Ghaisal Train Accident 2002

Diunggah oleh

Kanagaraj GanesanHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

(COL.

)

YOGESH

Indian PRABHAKAR,

J. Anaesth. 2002;

46 (5) :: GHAISAL

409-413 TRAIN ACCIDENT

409

GHAISAL TRAIN ACCIDENT

Col T. Prabhakar,VSM1 Col Yogesh Sharma,VSM2

SUMMARY

With the ever-increasing mechanization, vehicular accidents are steadily increasing in magnitude and frequency. Large sections of

the population use some form of mass transportation like trains, buses and airplanes etc. Any accident involving these means of mass

transportation could have disastrous consequences. In this presentation we would like to share our experience at 158 Base Hospital

regarding the management of victims of a train accident resulting from a head on collision between two fast moving passenger trains.

The sudden deluge of 149 casualties including 46 dead although stretched our medical resources but helped us in fine-tuning our

disaster management plans. Some unusual and interesting patterns of injury were encountered.

Keywords : Disaster management, Railway accident.

Introduction

Trauma, called the neglected child of modern

society is the principal cause of death and disability in the

first three decades of life.1 Although authentic data

regarding mortality and morbidity following trauma is

hard to get, trauma accounted for over 43 lakh victims

which included 7 lakh dead in India in 1994.2

The economic loss to the nation is staggering in

the form of loss of millions of work hours added to the

cost of treatment. Improvements in prehospital trauma

care, establishment of regional trauma care centers, use

of safety devices like seat belts, improved automobile

design and imposition of speed limits have reduced death/

disability rates but a lot still requires to be done. 158

Base Hospital was exposed to an influx of mass casualties

resulting from one such unfortunate train accident. An

effort has been made to outline the profile of injuries and

to share our experience in their management.

Materials and methods

In the early hours of 02 August 1999 the Delhi

bound Avadh Assam Mail collided head-on into the Gauhati

bound Brahmaputra Mail at GHAISAL (Fig 1,2,3). It

was one of the worst train accidents in the country, which

left more than 800 people injured and 256 dead. 103 of

the injured and 46 dead were received at 158 Base Hospital

on 02 and 03 August 99 within a period of about 36

hours. Although a few hours prior information about the

arrival of mass casualties was received the sudden influx

of such a large number of casualties pushed the entire

hospital services to perform beyond themselves in order

to manage this disaster.

1. MD., Senior Advisor

(Anaesthesiology), 158 Base, Hospital; C/O 99 APO

2. MS (Gen Surg), MS (Ortho),

Classified Specialist (Surgery & Ortho),

Command Hospital; Chandigarh

Figure : 1

Figure : 2

Figure : 3

410

All the patients had been given first aid at the site

of accident by the meager local medical resources. In

addition one surgical team of 158 Base Hospital went to

the accident site to organize the evacuation of casualties.

All the cases were received at a special reception center

for first aid and documentation. Each case was seen on arrival

by a surgeon and allotted priority in the usual manner

i.e., P-1 cases requiring immediate resuscitation and urgent

surgery (these included open intraarticular fractures) P-2

cases requiring possible resuscitation and early surgery

including dislocations and open fractures. P-3 for all other

cases. In addition special priorities were allotted for spinal

and eye injuries. Resuscitation was carried out along with

a quick primary survey and continued in the operation

theatre/acute wards as indicated. All cases with open

wounds were given tetanus prophylaxis and antibiotics.

Subsequently the injuries were regionalized. Life

and limb saving surgeries were carried out as per priority

already allotted. Later the complete nature of injuries

were determined and secondary procedures carried out.

Injuries requiring treatment at specialized centers were

identified and evacuated to appropriate centers.

Some of the patients arrived in a shocked state

because of multiple injuries, airway obstruction, massive

bleeding or other trauma requiring urgent resuscitation

and early surgery. Patients were provided uninterrupted

intensive therapy in severe trauma cases following

operations that have suffered critical hypotension or

hypoxia preoperatively or intraoperatively. There were

no delayed operations or premature interferences.

Diagnosis and treatment were occurring simultaneously.

Anaesthesia was administered and maintained

despite poor patient status and staffing, sometimes without

the benefit of supportive laboratory and previous medical

data. There were high incidence of critical events like

often lengthy operating procedures, multiple, serial or

simultaneous diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. Four

patients required ventilatory support and one of them

required ventilation for ten days. All the patients were

successfully weaned off the ventilator.

Results

A total of 149 cases were received in a period of

about 36 hours, these included 46 dead. Out of the injured

there were 99 males (96.1%) and 04 females (03.89%). Of

the 103 injured, 72 cases (70%) were Army personnel, 09

(08.7%) were from Assam Rifles, 06(05.8%) each from

Air force and CRPF. There were 07 civilians and three

cases from other paramilitary forces. All the injured were

traveling in the leading compartments of the two trains.

After triage the distribution of cases were as per Table-1.

A total of 17 units of blood transfusion were given. No

single case required more than 04 units of blood transfusion.

Regional distribution of cases is given in Table-2.

INDIAN JOURNAL OF ANAESTHESIA, OCTOBER 2002

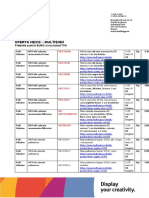

Table 1 : (Triage)

PRIORITY

No of CASES

PERCENTAGE

12

11.66%

31

30.01%

55

53.59%

05

04.95%

Priority-1

Polytruma

Thoracic injuries

Open intra-articular fracture

Priority-2

Acute dislocations

Open fractures

Others

Priority-3

Special priority

Cervical spinal injury

Dorsolumbar injury

Table 2 : Regional distribution of injuries

S. No

1.

REGION

No of Cases

Multiple superficial injuries

68

2.

Lower limb injuries

33

3.

Upper limb injuries

17

4.

Thoracic injuries

14

5.

Dislocations

09

6.

Head, neck & spine injuries

08

7.

Polytrauma

05

8.

Major lacerations

04

A total of 149 active procedures were carried out

during the course of management of the accident victims.

The various interventions are listed in Table-3 (Surgical

procedures/interventions). There were 40 major injuries

to the lower limbs in 33 cases. These included 32 fractures,

07 dislocations and one case of anterior compartment

syndrome in the leg. Description of the lower limb injuries

has been given in Table-4 (lower limb injuries). Details

of upper limb injuries are given in Table-5.

Table 3 : Surgical interventions

S No.

SURGICAL INTERVENTION

No

1.

POP application

43

2.

Suturing of lacerations

38

3.

Closed reductions

20

4.

Wound debridements

17

5.

ORIF (Open reduction internal fixation)

15

6.

Skeletal tractions

10

7.

External fixators

08

8.

Exploratory laparotomies

03

9.

Amputations

02

10.

Ventilatory support

04

11.

Tracheostomy

01

(COL.) PRABHAKAR, YOGESH : GHAISAL TRAIN ACCIDENT

Table 4 : Lower limb injuries (40 injuries in 33 patients)

S No

1.

2.

3.

4.

TYPE OF INJURY

No

Open fractures

Fracture shaft femur

Fracture tibia fibula

Bimalleolar fractures

(02)

(07)

(01)

Closed fractures

Fracture shaft femur

Subtrochanteric fractures

Fracture tibia fibula

Fracture patella

Malleolar & small bone Fractures

(02)

(01)

(05)

(04)

(10)

Dislocations

Anterior dislocation hip

Posterior dislocation hip

Central fracture

Dislocation hip

Compartment syndrome

10(26)

22(55)

07

(01)

(03)

(17.5)

(03)

01(02.5)

Table-5 : Upper limb injuries (24 injuries in 17 patients)

S.No

TYPE OF INJURY

1.

Open fractures

Humerus

Clavicle

Radius & ulna

(04)

(01)

(01)

Closed fractures

Humerus

Clavicle

Radius & ulna

Olecranon

(03)

(03)

(04)

(02)

Dislocations

Shoulder

Elbow

(01)

(01)

2.

3.

4.

Crush injury/Compartment syndrome

Neuropraxia radial, ulnar

and median nerves

Crush injury requiring

amputation

No (%)

06(25)

12(50)

02(08.3)

04(16.7)

(03)

(01)

All the seven cases of open fractures of the tibia

including one case of double segmental tibial fracture

were managed with wound debridement and external

fixators to begin with. All 07 dislocations of the hip were

reduced under general anaesthesia and managed with

skeletal traction after ensuring concentric reduction. Most

of the displaced fractures were managed with open

reduction and internal fixation if closed treatment was not

satisfactory. Fractures of the humerus predominated in

the upper limb injuries. One case had bilateral open

fractures of the humerus with neurological complications

in the right side, however he recovered fully with

411

conservative management after repeated debridements.

There were three cases of closed crush injuries of upper

limbs without fractures. There were 2 cases of flail chest

among the patients with thoracic injuries, one of which

had to be managed on ventilator for 10 days. The 08

cases of head, neck and spinal injuries included 04 (50%)

skull fractures, 02 (25%) fractures of the cervical spine.

All these cases were managed conservatively.

Among the three cases of blunt abdominal trauma,

one had an isolated splenic injury requiring splenectomy,

the other had combined splenic and hepatic lacerations

and the third case had a large retroperitoneal haematoma

along with a mesenteric injury. All these cases required

resuscitation with IV fluids and blood before surgery.

Missed injuries

In this series there were 06 missed injuries (05.8%).

These included one case of fracture olecranon in a case

of splenic rupture. Three cases of fractures of the clavicle

were missed in cases of polytrauma, and malleolar fractures

were missed in 2 cases. All the missed injuries were

discovered after the patients returned for review after

visiting their homes with fresh complaints.

Outcome

Sixty-seven cases were discharged within 15 days

of admission. Six cases were discharged between 15

days and 2 months and 29 cases required hospitalization

beyond 2 months (these were cases of open/complicated

fractures). Two cases of traumatic paraplegia were transferred

to spinal cord injury centers and 2 cases of comminuted

central fracture dislocations were transferred to joint

replacement centers for total hip replacement. Three cases

of grade 3 open tibia fractures required full thickness skin

cover before definitive orthopedic procedures. Two cases

required major amputations (one above knee and one below

elbow). One case of fracture dislocation C4-C5 died within

hours of admission.

Discussion

All the patients had been given some sort of first

aid at the site of accident by the meager medical resources

that could reach the site. The effectiveness of such

treatment was doubtful. In fact it was only delaying

evacuation. This makes us rethink the effectiveness of

pre clinical emergency management, fiction or fact? Study

results obtained in trauma patients indicating that total

pre hospital time, including scene time, is correlated to

patient outcome have led to the conclusion that at the

scene treatment by emergency physicians may be

dispensable. It has, however also been demonstrated that

412

INDIAN JOURNAL OF ANAESTHESIA, OCTOBER 2002

the time required for medical treatment at the scene is

equivalent to 20% of the total scene time, thus

representing only a fraction of the total pre hospital

time. Correlating the total pre hospital time or scene

time to outcome therefore appears absurd. The treatment

principle of aggressive shock in poly trauma needs critical

reevaluation on the basis of results obtained by recent

preclinical studies in patients with penetratrating torso

injuries. Small volume resuscitation could not be

demonstrated to improve outcome in polytrauma patients,

although a slight improvement with brain injury may be

assumed. Endotracheal intubation and early artificial

ventilation are proven therapeutic principles in

polytraumatised patients.7

Ghaisal is a small village and evacuation of

casualties to Siliguri required lot of transport and the

distance is 90 kilometers. In Army we use the McPhersons

formula to deal with such problems.

(a)

To find out the time required : T=1/M x W x t/N

(b)

To find out the amount of transport required to

evacuate in a given time :

Where

M =

1/T x W x t/N

M =

Units of transport required or

available

T =

Time allowed

W =

Number of sick and wounded

Time taken by transport for one

journey and return

N =

Number of patients each unit of

transport carries.

By knowing the variables, you can calculate the

number of ambulances required for transportation of

the casualties. In the usual method of allotment of

priorities (triage) threat to life has been the only basis of

allotment of priority; the morbidity potential has not

been given due weightage. Standard acceptable figures

of P-1,P-2,P-3 accounted for 10%, 20% and 70%

cases respectively. In our series there were 11% cases of

P-1, 30% P-2 and 59% P-3 cases. The difference is due

to the fact that we have included open intra articular

fractures in P-1 cases and open fractures and dislocations

in P-2 cases. This has been done due to the fact that

any delay in treatment of open fractures, dislocations

and open intra-articular fractures can result in

considerable morbidity. Comparison of regional

distribution of injuries in various disasters3 is brought

out in Table-6. The difference between our series and

other series can be explained by the vastly different

mechanism of injury in war wounds which are caused by

blasts and projectiles and those caused by sudden

deceleration as seen in the Ghaisal train accident.

Table 6 : Comparison of regional distribution of injuries (3)

INJURY

KOREAN

WAR (%)

INDO-PAK

CONFLICT (%)

158 BH

EXPERIENCE (%)

Head injury

15

01

07.7

Thoracic injury

19

12

13.6

Abdominal injury

11

13

2.9

Upper limb injury

25

22

16.5

Lower limb injury

27

69

32

Anaesthesia for trauma patients is challenging. The

problems were high workload, physical, high psychological

and emotional stress. The moment-by-moment care by

titrating, so crucial for patients with life threatening injuries

is difficult and it should be done with utmost care and

devotion, unmindful of personal comfort.

Missed injuries

Mass casualties present with confusing and

continuously changing situations. Various reasons such as

haemodynamic instability, polytrauma, altered sensorium

and low index of suspicion can contribute to missed

injuries. Table-7 provides considerable figures for

missed injuries in various studies. Wide variation in the

incidence of missed injuries is perhaps due to the absence

of clear-cut guidelines regarding what constitutes a missed

injury.

Table 7 : Comparative figures of missed injuries

STUDY

TYPE

of TRAUMA

No of CASES

MISSED

INJURIES

Albrektesen SB

Thompson JL (1989) (5)

Blunt

218

75(34%)

Chan RNW, Ainscow D

(1980) (4)

Blunt

327

39(12%)

Enderrson BL, Stevens SL

De Boo JM (1990) (6)

Blunt

399

36(11%)

158 BH Experience

Blunt

103

06(5.08%)

Unusual patterns of injuries observed

The high number of casualties received in a short

period of 36 hours

Extrication problems were acute being a railway

accident and was responsible for some of the unusual

pattern of injuries.

(COL.) PRABHAKAR, YOGESH : GHAISAL TRAIN ACCIDENT

The high incidence of grade 3 open tibial fractures

and the use of external fixators

The unusually high number of dislocations of hip

The three cases of closed crush injuries of upper

limbs (All had complete motor loss in upper limbs

without sensory impairment and their subsequent

spontaneous recovery)

The two cases of ARDS

Burns and penetrating injuries were conspicuous by

their absence

References

1. James R. Macho, MD, Frank R. Lewis, Jr., MD, & William

C. Krupski, MD, Management of the injured patient, In:

Lawrence W Way, Editor, Current surgical diagnosis and

treatment, 10th ed. Appleton and Lange, USA, 1994;

213-225.

413

2. Indrayan A, Epidemiology of Trauma deaths in India in

Principles and practice of trauma care (Ed) Kocher SK, Jaypee

Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd, New Delhi, 1998; 1-12.

3. VK Sinha, Management of ballistic injuries in : Principles

and practice of trauma care (Ed) Kocher SK, Jaypee Brothers

Medical Publishers (P) Ltd, New Delhi, 1998; 32-47.

4. Chan RNW, Ainscow D, Sikoski, JM; Diagnostic failures in

the multipl injured, J Trauma 1980, 20: 684-688.

5. Albrektesen SB, Thomson JL., Detection of injuries in

traumatic death. The significance of medico legal autopsy.

Forces Sci Int 1989;42:135-138.

6. Enderson BL, Stevens SL, DeBoo JM et al ; Occult

pneumothorax in blunt trauma. South Eastern Surgical

Congress Napples 1990.

7. Klinik fur anastheiologie der Johannes Gutenberg Universitat

Mainz. Anaesthesist (Germany) Jan 1996: 45 (1), 75-87.

BOOK REVIEW

Book Title

: 1) Anesthesia and co-existing Disease.

Forth Edition 2002. (Indian Print)

print, the book, I am sure, will attract every anaesthesiology

trainee and the practitioner.

Authors

Robert Stoelting, Stephon F Dierdort.

Publisher

Harcourt India Pvt. Ltd. A Elsevier Science

company

Price

Rs. 1475/-

I, on behalf of IJA, congratulate the publishers Harcourt

India Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, for bringing out such an excellent

tool of education at an affordable price. I recommend this book

for all the learners of anaesthesiology.

The goal of this book as spelt out by the editors is to

provide the readers with Current and Concise descriptions of the

pathophysiology of diseases, and the impact if any on the

management of anaesthesia. More common conditions like

Diabetes, Hypertension, IHD, etc, which every anaesthesiologist

encounters in his day today practice, are described in wider

details whereas the less common ones are discussed, based on

their unique features which have impact on anaesthetic

management.

Optimal use of illustrations, tables, figures, algorithms,

etc make the book easily understandable and more readable.

Each chapter covers the entire aspects of a topic in a concise

manner, right from the introductory information, basic sciences

to recent advances of the topic. The optimally sized and relevant

bibliography is an unique treasure of the book, catalyzing the

reader to approach the original source of information. The language

of the book is simple with consistent theme of narration throughout

the length of the book. This uniform style is quite acceptable for

every reader as every chapter in the book is finally authored by

the editors, though the contributions according to authors have

been sought by many authors.

With the new format, of presentation with newer tables

and illustrations, with distinct economical advantage of Indian

Book Title : 2) Handbook For Anesthesia and

Co-existing Disease Second Edition 2002

(Indian Print).

Authors

Robert K Stoelting and Stephen F Dierdort.

Publisher :

Harcourt India Pvt. Ltd. A Elsevier Science

company

Price

Rs. 275/-

Hand books play a distinct role in providing optimal

anaesthetic patient care. Irrespective of ones seniority or

experience in the field, there is always a need for a reliable

ready reckoner, which in anaesthetic practice is in scarcity.

This hand book, a companion to the widely read, Anesthesia

and Co-existing Disease, provides rapid and accurate information

at the actual site of patient care (i.e. in OTs, ICUs etc.) if

carried in the pocket. The table format of presentation, facilitates

the quick approach to the needed information.

I appreciate and congratulate the efforts of the authors

and the publishers for providing this pocket dictionary of

anaesthesia for a modest price.

- Editor.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Come Back To Your Senses Use Your Body: Psychologyt LsDokumen1 halamanCome Back To Your Senses Use Your Body: Psychologyt LsMarina Moran100% (1)

- MDR Guideline Medical Devices LabelingDokumen7 halamanMDR Guideline Medical Devices Labelingarade43100% (1)

- The Nakshatras and Hindu Moon CyclesDokumen79 halamanThe Nakshatras and Hindu Moon CyclesKanagaraj Ganesan100% (1)

- UHS Adult Major Trauma GuidelinesDokumen241 halamanUHS Adult Major Trauma Guidelinesibeardsell1100% (2)

- Sampling Methods GuideDokumen35 halamanSampling Methods GuideKim RamosBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical Biomechanics in Implant DentistryDokumen36 halamanClinical Biomechanics in Implant DentistryMahadevan Ravichandran100% (4)

- Ghaisal Train Accident: Col T. Prabhakar, Col Yogesh SharmaDokumen5 halamanGhaisal Train Accident: Col T. Prabhakar, Col Yogesh SharmaAmiya LahiriBelum ada peringkat

- Disaster Management During Train AccidentDokumen10 halamanDisaster Management During Train AccidentFauzia Begum100% (1)

- The Chinese National Emergency Medical Rescue Team Response To The Sichuan Lushan EarthquakeDokumen6 halamanThe Chinese National Emergency Medical Rescue Team Response To The Sichuan Lushan EarthquakeCiprian PopoviciBelum ada peringkat

- R R R R R: P P P!PP"P#PP! P$%&'P ( ( (#PP'P# #$# +PP, P' - p-./01pp, PDokumen5 halamanR R R R R: P P P!PP"P#PP! P$%&'P ( ( (#PP'P# #$# +PP, P' - p-./01pp, PDuaa MaqboolBelum ada peringkat

- 28nnadi EtalDokumen4 halaman28nnadi EtaleditorijmrhsBelum ada peringkat

- Journal07 MainDokumen8 halamanJournal07 MainNeyylaBelum ada peringkat

- Nepal Plastic SurgeryDokumen7 halamanNepal Plastic SurgeryAnonymous 8hVpaQdCtrBelum ada peringkat

- Self-Extrication and Selective Spinal Immobilisation in A Polytrauma Patient With Spinal InjuriesDokumen4 halamanSelf-Extrication and Selective Spinal Immobilisation in A Polytrauma Patient With Spinal InjuriesLeandro NogueiraBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal Trauma 4Dokumen6 halamanJurnal Trauma 4futri elisaBelum ada peringkat

- Dco 5 PDFDokumen10 halamanDco 5 PDFGauda GranthanaBelum ada peringkat

- Primary Management of PolytraumaDari EverandPrimary Management of PolytraumaSuk-Kyung HongBelum ada peringkat

- DL TPSFDokumen5 halamanDL TPSFPramod N KBelum ada peringkat

- 2019 Golden Hour and The Management of Polytrauma. The Experience of Salento's Up-And-Coming Trauma Center PDFDokumen5 halaman2019 Golden Hour and The Management of Polytrauma. The Experience of Salento's Up-And-Coming Trauma Center PDFAndresPinedaMBelum ada peringkat

- Aruna Ramesh Emergency...Dokumen25 halamanAruna Ramesh Emergency...Aishu BBelum ada peringkat

- Acute Nursing Care of The Older Adult With Fragility Hip Fracture: An International Perspective (Part 2)Dokumen26 halamanAcute Nursing Care of The Older Adult With Fragility Hip Fracture: An International Perspective (Part 2)spring flowerBelum ada peringkat

- Closed Femur Fracture Case ReportDokumen33 halamanClosed Femur Fracture Case ReportLana AdilaBelum ada peringkat

- Pi Is 1569905605809327Dokumen1 halamanPi Is 1569905605809327Aswad AffandiBelum ada peringkat

- Kragh Ann SurgDokumen7 halamanKragh Ann SurgIntruso2Belum ada peringkat

- 21 Recommendations On Hip FracturesDokumen7 halaman21 Recommendations On Hip FracturesnelsonaardilaBelum ada peringkat

- Case Report Juli 2013Dokumen21 halamanCase Report Juli 2013NahdiaBelum ada peringkat

- Grup 3 - Safety and Accident PreventionDokumen36 halamanGrup 3 - Safety and Accident PreventionArsitaBelum ada peringkat

- Abstracts Estes Congress 2010 WebDokumen238 halamanAbstracts Estes Congress 2010 WebAna Cláudia CarriçoBelum ada peringkat

- Review of Intramedullary Interlocked Nailing in Closed & Grade I Open Tibial FracturesDokumen4 halamanReview of Intramedullary Interlocked Nailing in Closed & Grade I Open Tibial FracturesInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Belum ada peringkat

- Penetratng InjuryDokumen5 halamanPenetratng InjuryAbdulloh AbdurrohmanBelum ada peringkat

- Fraktur FemurDokumen11 halamanFraktur FemurYusuf BrilliantBelum ada peringkat

- OOI Cervical Spine IniuriesDokumen7 halamanOOI Cervical Spine IniurieskeanshengBelum ada peringkat

- Fasciotomy Procedures On Acute Compartment Syndromes of The Upper Extremity Related To BurnsDokumen6 halamanFasciotomy Procedures On Acute Compartment Syndromes of The Upper Extremity Related To BurnsMetta TantraBelum ada peringkat

- Electrical Injuries: A 20-Year ReviewDokumen6 halamanElectrical Injuries: A 20-Year ReviewWesley Faruk ABelum ada peringkat

- Distal Humerus Fracture in Patients Over 70 Years of Age: Results of Open Reduction and Internal FixationDokumen8 halamanDistal Humerus Fracture in Patients Over 70 Years of Age: Results of Open Reduction and Internal FixationSantiago Coba GonzálezBelum ada peringkat

- Sabapathy 2012Dokumen7 halamanSabapathy 2012Le Manh ThuongBelum ada peringkat

- 12 Padmanabha EtalDokumen4 halaman12 Padmanabha EtaleditorijmrhsBelum ada peringkat

- 頸椎損傷患者之呼吸照護經驗Dokumen8 halaman頸椎損傷患者之呼吸照護經驗s0874057物治系Belum ada peringkat

- Conference Paper: Rapid Physical Assessment of The Injured ChildDokumen4 halamanConference Paper: Rapid Physical Assessment of The Injured ChildMaiush JbBelum ada peringkat

- Treatment of AO/OTA 31-A3 Intertrochanteric Femoral Fractures With A Percutaneous Compression PlateDokumen7 halamanTreatment of AO/OTA 31-A3 Intertrochanteric Femoral Fractures With A Percutaneous Compression PlateNurul AiniBelum ada peringkat

- Orthopaedics and TraumatologyDokumen28 halamanOrthopaedics and Traumatologyazureenhalim91Belum ada peringkat

- Complications of Temporomandibular Joint Arthroscopy: A Retrospective Analytic Study of 670 Arthroscopic ProceduresDokumen5 halamanComplications of Temporomandibular Joint Arthroscopy: A Retrospective Analytic Study of 670 Arthroscopic ProceduresAbhishek SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Delayed Diaphragmatic Hernia DiagnosisDokumen3 halamanDelayed Diaphragmatic Hernia DiagnosisNining Rhyanie TampubolonBelum ada peringkat

- Practice: Teaching Case ReportDokumen4 halamanPractice: Teaching Case ReportIntruso2Belum ada peringkat

- Risk Factors For Ischemic Stroke Post Bone FractureDokumen11 halamanRisk Factors For Ischemic Stroke Post Bone FractureFerina Mega SilviaBelum ada peringkat

- Acute Nursing Care of The Older Adult With Fragility Hip Fracture An International Perspective Part 2 PDFDokumen15 halamanAcute Nursing Care of The Older Adult With Fragility Hip Fracture An International Perspective Part 2 PDFOktaBelum ada peringkat

- Post-Earthquake Injuries Treated at A Field Hospital - Haiti, 2010Dokumen48 halamanPost-Earthquake Injuries Treated at A Field Hospital - Haiti, 2010worksheetbookBelum ada peringkat

- Abdominal Trauma in Durban South AfricaFactors Influencing OutcomeDokumen8 halamanAbdominal Trauma in Durban South AfricaFactors Influencing Outcomefatma rekikBelum ada peringkat

- Abdominal Trauma in Durban South AfricaFactors Influencing OutcomeDokumen8 halamanAbdominal Trauma in Durban South AfricaFactors Influencing Outcomefatma rekikBelum ada peringkat

- Cabalag2014 PDFDokumen7 halamanCabalag2014 PDFEko SetiawanBelum ada peringkat

- Complications in Shoulder Arthroplasty: An Analysis of 485 CasesDokumen8 halamanComplications in Shoulder Arthroplasty: An Analysis of 485 CasesMohamed S. GalhoumBelum ada peringkat

- Art 3A10.1186 2Fs13032 015 0027 0 PDFDokumen5 halamanArt 3A10.1186 2Fs13032 015 0027 0 PDFElia HutapeaBelum ada peringkat

- Rapid Physical Assessment of The Injured Child: Robert Steelman, MD, DMDDokumen4 halamanRapid Physical Assessment of The Injured Child: Robert Steelman, MD, DMDkrantiBelum ada peringkat

- Emergency Trauma Care: ATLS: January 2011Dokumen5 halamanEmergency Trauma Care: ATLS: January 2011puaanBelum ada peringkat

- Damage Control Orthopaedics PDFDokumen6 halamanDamage Control Orthopaedics PDFRakesh KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Nasional 3 NIC:KOE Penetrating Cervial Spine Injury ENDokumen6 halamanNasional 3 NIC:KOE Penetrating Cervial Spine Injury ENHeru Sutanto KBelum ada peringkat

- Case Report: A Case of Traumatic Asphyxia Due To Motorcycle AccidentDokumen4 halamanCase Report: A Case of Traumatic Asphyxia Due To Motorcycle AccidentAgus MarkembengBelum ada peringkat

- Orbitozygomatic Fracture Repairs: Are Antibiotics Necessary?Dokumen6 halamanOrbitozygomatic Fracture Repairs: Are Antibiotics Necessary?Sani Widya FirnandaBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation of Crush Syndrome Patients With Extremity Injuries in The 2011 Van Earthquake in TurkeyDokumen7 halamanEvaluation of Crush Syndrome Patients With Extremity Injuries in The 2011 Van Earthquake in Turkeysiti fatimahBelum ada peringkat

- FuckuDokumen7 halamanFuckushark1212Belum ada peringkat

- A Review of Ureteral Injuries After External TraumaDokumen12 halamanA Review of Ureteral Injuries After External TraumaSuelen DanielBelum ada peringkat

- Spinal Board 4Dokumen3 halamanSpinal Board 4Navisatul MutmainahBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical Outcomes of Locked Plating of Distal Femoral Fractures in A Retrospective CohortDokumen9 halamanClinical Outcomes of Locked Plating of Distal Femoral Fractures in A Retrospective Cohortisnida shela arloviBelum ada peringkat

- C2 U5 Williams Et Al Critical Care Clinics 2013Dokumen32 halamanC2 U5 Williams Et Al Critical Care Clinics 2013Diego CrucesBelum ada peringkat

- Surgicalmanagementof Musculoskeletaltrauma: Daniel J. Stinner,, Dafydd EdwardsDokumen13 halamanSurgicalmanagementof Musculoskeletaltrauma: Daniel J. Stinner,, Dafydd EdwardsIthaBelum ada peringkat

- Biological Races in Humans 2014Dokumen22 halamanBiological Races in Humans 2014Kanagaraj GanesanBelum ada peringkat

- Orthotic OverviewDokumen59 halamanOrthotic OverviewKanagaraj GanesanBelum ada peringkat

- Air Permeability of Spun-Laced FabricsDokumen5 halamanAir Permeability of Spun-Laced FabricsKanagaraj GanesanBelum ada peringkat

- Effective Use of Smart Cards 2012 Sweden StudyDokumen36 halamanEffective Use of Smart Cards 2012 Sweden StudyKanagaraj GanesanBelum ada peringkat

- Web-Based Human Advisor Fuzzy Expert Sys 2013 PaperDokumen8 halamanWeb-Based Human Advisor Fuzzy Expert Sys 2013 PaperKanagaraj GanesanBelum ada peringkat

- Ranti: National E-Governance Plan (Negp) 2.0Dokumen105 halamanRanti: National E-Governance Plan (Negp) 2.0Kanagaraj GanesanBelum ada peringkat

- Air Permeability Value of Textile FabricsDokumen10 halamanAir Permeability Value of Textile FabricsgokulBelum ada peringkat

- Application Form-A Registrn As MFR With DGS & DDokumen7 halamanApplication Form-A Registrn As MFR With DGS & DKanagaraj GanesanBelum ada peringkat

- Orthotic OverviewDokumen59 halamanOrthotic OverviewKanagaraj GanesanBelum ada peringkat

- Wrist Wrap China US ITC Rulings & HTS NYN 019242 2007Dokumen2 halamanWrist Wrap China US ITC Rulings & HTS NYN 019242 2007gkanagaraj1963Belum ada peringkat

- NSIC IndiaDokumen12 halamanNSIC IndiaKanagaraj GanesanBelum ada peringkat

- Therapeutic Hosiery Oct 2008 CMEDokumen10 halamanTherapeutic Hosiery Oct 2008 CMEKanagaraj GanesanBelum ada peringkat

- Pediatric Flexible Flatfoot Sep 2008 CMEDokumen10 halamanPediatric Flexible Flatfoot Sep 2008 CMEKanagaraj GanesanBelum ada peringkat

- Dynamic Fall Detection and Pace Measurement in Walking SticksDokumen3 halamanDynamic Fall Detection and Pace Measurement in Walking SticksKanagaraj GanesanBelum ada peringkat

- Ptdial Arm Brand Germany Us Itc Rulings & Hts Ot RR NC n1 105 Ny N 025755 2008Dokumen2 halamanPtdial Arm Brand Germany Us Itc Rulings & Hts Ot RR NC n1 105 Ny N 025755 2008Kanagaraj GanesanBelum ada peringkat

- Oferta Hexis - Multisign: Preturile Sunt in EURO Si Nu Includ TVADokumen9 halamanOferta Hexis - Multisign: Preturile Sunt in EURO Si Nu Includ TVAPoschina CiprianBelum ada peringkat

- AIIMS Bibinagar Recruitment for Faculty PostsDokumen22 halamanAIIMS Bibinagar Recruitment for Faculty PostsavinashBelum ada peringkat

- Intro To Wastewater Collection and PumpingDokumen84 halamanIntro To Wastewater Collection and PumpingMoh'd KhadBelum ada peringkat

- BDS 3rd Year Oral Pathology NotesDokumen35 halamanBDS 3rd Year Oral Pathology NotesDaniyal BasitBelum ada peringkat

- Module 7 Health Insurance Types and ImportanceDokumen10 halamanModule 7 Health Insurance Types and ImportanceKAH' CHISMISSBelum ada peringkat

- Everett Association of School Administrators (EASA) Administrative HandbookDokumen46 halamanEverett Association of School Administrators (EASA) Administrative HandbookJessica OlsonBelum ada peringkat

- Personality Disorders Cluster CDokumen19 halamanPersonality Disorders Cluster CPahw BaluisBelum ada peringkat

- Slaked Lime MSDS Safety SummaryDokumen7 halamanSlaked Lime MSDS Safety SummaryFurqan SiddiquiBelum ada peringkat

- Alex AspDokumen11 halamanAlex AspAceBelum ada peringkat

- Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic PurpuraDokumen3 halamanIdiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpuraproxytia64Belum ada peringkat

- Insert - Elecsys Anti-HAV IgM.07026773500.V5.EnDokumen4 halamanInsert - Elecsys Anti-HAV IgM.07026773500.V5.EnVegha NedyaBelum ada peringkat

- Incident Reports 2017-2019Dokumen8 halamanIncident Reports 2017-2019Buddzilla FranciscoBelum ada peringkat

- Heart Failure Lily ModifiedDokumen57 halamanHeart Failure Lily ModifiedSabila FatimahBelum ada peringkat

- Journal Homepage: - : IntroductionDokumen3 halamanJournal Homepage: - : IntroductionIJAR JOURNALBelum ada peringkat

- Per. Dev. (Bin-Bin)Dokumen21 halamanPer. Dev. (Bin-Bin)Jayric BanagyoBelum ada peringkat

- Informed Consent and Release, Waiver, and Quitclaim: Know All Men by These PresentsDokumen2 halamanInformed Consent and Release, Waiver, and Quitclaim: Know All Men by These PresentsRobee Camille Desabelle-SumatraBelum ada peringkat

- Crodua Prioritization TableDokumen10 halamanCrodua Prioritization TableThea DuoBelum ada peringkat

- Bio-Oil® Product ManualDokumen60 halamanBio-Oil® Product ManualguitarristaclasicosdnBelum ada peringkat

- Methodology Tapping Methodology of WaterlineDokumen15 halamanMethodology Tapping Methodology of WaterlineBryBelum ada peringkat

- Jordan Leavy Carter Criminal ComplaintDokumen10 halamanJordan Leavy Carter Criminal ComplaintFOX 11 NewsBelum ada peringkat

- Zhou 2008Dokumen10 halamanZhou 2008zael18Belum ada peringkat

- UV-VIS Method for Estimating Fat-Soluble Vitamins in MultivitaminsDokumen6 halamanUV-VIS Method for Estimating Fat-Soluble Vitamins in MultivitaminsTisenda TimiselaBelum ada peringkat

- Transport Technology Center (T.T.C)Dokumen19 halamanTransport Technology Center (T.T.C)Abubakar Lawan GogoriBelum ada peringkat

- Tolterodine Tartrate (Detrusitol SR)Dokumen11 halamanTolterodine Tartrate (Detrusitol SR)ddandan_2Belum ada peringkat

- Q1. Read The Passage Given Below and Answer The Questions That FollowDokumen2 halamanQ1. Read The Passage Given Below and Answer The Questions That FollowUdikshaBelum ada peringkat

- 1.2.1 Log 1Dokumen3 halaman1.2.1 Log 1linuspauling101100% (6)