Nejm 1

Diunggah oleh

Tri Anna FitrianiJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Nejm 1

Diunggah oleh

Tri Anna FitrianiHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

new england

journal of medicine

The

established in 1812

october 2, 2014

vol. 371 no. 14

Withdrawal of Inhaled Glucocorticoids and Exacerbations of COPD

Helgo Magnussen, M.D., Bernd Disse, M.D., Ph.D., Roberto Rodriguez-Roisin, M.D., Anne Kirsten, M.D.,

Henrik Watz, M.D., Kay Tetzlaff, M.D., Lesley Towse, B.Sc., Helen Finnigan, M.Sc., Ronald Dahl, M.D.,

Marc Decramer, M.D., Ph.D., Pascal Chanez, M.D., Ph.D., Emiel F.M. Wouters, M.D., Ph.D.,

and Peter M.A. Calverley, M.D., for the WISDOM Investigators*

A bs t r ac t

Background

Treatment with inhaled glucocorticoids in combination with long-acting bronchodilators is recommended in patients with frequent exacerbations of severe chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). However, the benefit of inhaled glucocorticoids in addition to two long-acting bronchodilators has not been fully explored.

Methods

In this 12-month, double-blind, parallel-group study, 2485 patients with a history of

exacerbation of COPD received triple therapy consisting of tiotropium (at a dose of

18 g once daily), salmeterol (50 g twice daily), and the inhaled glucocorticoid

fluticasone propionate (500 g twice daily) during a 6-week run-in period. Patients

were then randomly assigned to continued triple therapy or withdrawal of fluticasone in three steps over a 12-week period. The primary end point was the time to

the first moderate or severe COPD exacerbation. Spirometric findings, health status,

and dyspnea were also monitored.

Results

The authors affiliations are listed in the

Appendix. Address reprint requests to

Dr. Magnussen at the Pulmonary Research

Institute at Lung Clinic Grosshansdorf,

Woehrendamm 80, D-22927 Grosshans

dorf, Germany, or at magnussen@

pulmoresearch.de.

*Investigators in the Withdrawal of Inhaled

Steroids during Optimized Bronchodilator Management (WISDOM) study are

listed in the Supplementary Appendix,

available at NEJM.org.

This article was published on September 8,

2014, and updated on October 2, 2014, at

NEJM.org.

N Engl J Med 2014;371:1285-94.

DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407154

Copyright 2014 Massachusetts Medical Society.

As compared with continued glucocorticoid use, glucocorticoid withdrawal met the

prespecified noninferiority criterion of 1.20 for the upper limit of the 95% confidence

interval (CI) with respect to the first moderate or severe COPD exacerbation (hazard

ratio, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.94 to 1.19). At week 18, when glucocorticoid withdrawal was

complete, the adjusted mean reduction from baseline in the trough forced expiratory volume in 1 second was 38 ml greater in the glucocorticoid-withdrawal group

than in the glucocorticoid-continuation group (P<0.001); a similar between-group

difference (43 ml) was seen at week 52 (P=0.001). No change in dyspnea and minor

changes in health status occurred in the glucocorticoid-withdrawal group.

Conclusions

In patients with severe COPD receiving tiotropium plus salmeterol, the risk of moderate or severe exacerbations was similar among those who discontinued inhaled

glucocorticoids and those who continued glucocorticoid therapy. However, there

was a greater decrease in lung function during the final step of glucocorticoid

withdrawal. (Funded by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma; WISDOM ClinicalTrials.gov

number, NCT00975195.)

n engl j med 371;14nejm.orgoctober 2, 2014

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on May 24, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2014 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

1285

The

n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l

xacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are symptomatically defined, acute events that lead

to a change in treatment1,2 and are associated

with an accelerated decline in lung function and

health status.3 Treatment with inhaled glucocorticoids reduces the exacerbation rate, especially

when the drugs are used in combination with a

long-acting -agonist (LABA).4,5 Consequently,

combination therapy with an inhaled glucocorticoid and a LABA is recommended in patients

with severe COPD or a history of frequent exacerbations.2 Long-acting muscarinic antagonists

(LAMAs) have also been shown to prevent exacerbations.6-8 However, in patients with severe or

very severe COPD and a history of exacerbations,

the benefit of inhaled glucocorticoids in a regimen that includes these two classes of long-acting bronchodilators has not yet been determined

in an adequately powered study.

We hypothesized that with a controlled, stepwise withdrawal of inhaled glucocorticoids, the

risk of exacerbation would be similar to that with

continued use of inhaled glucocorticoids in patients with severe or very severe COPD who were

receiving a combination of a LAMA (tiotropium)

and a LABA (salmeterol). To test this hypothesis,

we conducted the Withdrawal of Inhaled Steroids

during Optimized Bronchodilator Management

(WISDOM) trial, which was designed to determine whether patients with COPD who were receiving both LAMA and LABA therapy with inhaled glucocorticoids would have similar outcomes

regardless of whether the glucocorticoids were

withdrawn or continued.

Me thods

Study Design

From February 2009 through July 2013, we performed this multinational, randomized, doubleblind, parallel-group, active-control study. All patients entered a 6-week run-in period during which

they received 18 g of tiotropium once daily (delivered by a HandiHaler), 50 g of salmeterol xina

foate twice daily (two actuations of 25 g; a dose

of 21 g is designated on the U.S. product label),

and 500 g of fluticasone propionate (an inhaled

glucocorticoid) twice daily (two actuations of 250

g [U.S. designated dose, 230 g] delivered by a

metered-dose inhaler). In this study, we refer to

the European Union designation of doses for

consistency.

1286

of

m e dic i n e

During the double-blind phase of the trial,

patients underwent randomization in a 1:1 ratio

to the two study groups. The first group continued to receive tiotropium, salmeterol, and flut ic

asone at the same doses as those used during

the run-in period for the duration of the 52-week

study period. The second group continued to receive tiotropium and salmeterol over the 52-week

period but with a stepwise reduction in the flutic

asone dose every 6 weeks, from a total daily dose

of 1000 g to 500 g, then to 200 g, and finally

to 0 g (placebo)9 (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary

Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org). Patients who prematurely discontinued therapy were followed for vital status

from the time of discontinuation until the completion of the trial at 52 weeks.

Patients

We recruited patients who were at least 40 years

of age and who were either current smokers (10

pack-years) or former smokers and had received a

diagnosis of severe or very severe COPD, which

was defined as a forced expiratory volume in

1second (FEV1) that was less than 50% of the

predicted volume and less than 70% of the forced

vital capacity after bronchodilation and a history

of at least one documented exacerbation in the

12 months before screening. Full inclusion and

exclusion criteria have been reported previously9

and are provided in the trial protocol, which is

available at NEJM.org. All patients provided written informed consent.

The use of xanthines and mucolytic agents, but

not maintenance oral glucocorticoid treatment,

was allowed throughout the trial. All patients

were provided with open-label salbutamol (also

known as albuterol) for use as needed. At the

investigators discretion, randomized treatment

could be discontinued and open-label fluticasone

could be initiated for the remainder of the trial.

Any exacerbations that were reported after the

discontinuation of randomized treatment were not

included in the primary end point. Included in a

prespecified sensitivity analysis were exacerbations

that were reported in patients who were receiving

open-label fluticasone therapy and in those who

had discontinued treatment.

End Points and Assessments

The primary end point was the time to the first

moderate or severe COPD exacerbation during

the 12-month study period. We used a standard-

n engl j med 371;14nejm.orgoctober 2, 2014

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on May 24, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2014 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Glucocorticoid Withdr awal and COPD Exacerbations

ized, structured questionnaire to collect data regarding exacerbations, with documentation at

each study visit. In addition, we provided patients

with a simple diary, to be completed on a daily

basis, for noting changes in symptoms and the

use of medications between visits. A moderate

exacerbation was defined as an increase in lower

respiratory tract symptoms related to COPD or

the new onset of two or more such symptoms,

with at least one symptom lasting 3 or more days

and for which the treating physician prescribed

antibiotics, systemic glucocorticoids, or both. A

severe exacerbation was defined as an exacerbation requiring hospitalization in an urgent care

unit. The start date of an exacerbation was defined as the onset date of the first recorded COPD

symptom.

Secondary end points included the time to the

first severe COPD exacerbation, the number of

moderate or severe COPD exacerbations, the

change from baseline in lung function (including

the trough FEV1, forced vital capacity, and peak

expiratory flow rate), health status, and dyspnea.

To assess health status, we used the total score

on the St. Georges Respiratory Questionnaire

(SGRQ), on a scale of 0 to 100, with higher scores

indicating worse function and a minimum clinically important difference of 4 points.10 To assess dyspnea, we used the modified Medical

Research Council (mMRC) scale of 0 to 4, with

higher scores indicating more severe dyspnea; the

absence of breathlessness was given a score of 1.

No minimum clinically important difference has

been identified.11 All secondary end points were

assessed over the 12-month study period.

We performed all spirometric measurements

according to the recommendations of the American

Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory

Society12 at baseline and at weeks 6, 12, 18, and

52. We used values after bronchodilation in qualifying tests of pulmonary function. Before performing spirometric testing, we obtained scores

on the SGRQ at baseline and at weeks 27 and 52

and obtained scores on the mMRC scale at baseline and at weeks 18 and 52. (Additional details

regarding the end points are provided in the

protocol and in Table S1 in the Supplementary

Appendix.)

18, and 52. Chest radiography was requested when

pneumonia was suspected during the trial. Adverse events and serious adverse events, regardless of causality, were recorded throughout the

study, and results are reported descriptively. If patients did not spontaneously report adverse events,

they were asked open-ended questions, such as

How have you felt since the last visit?

Study Oversight

The study protocol was approved by the ethics

review board at each institution. The first draft

of the manuscript and subsequent revisions were

written by the academic authors, and all the authors worked collaboratively to prepare the final

content; all the authors made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Editorial assistance was provided by a medical writer employed

by a company that was paid by the study sponsor,

Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma. Statistical analyses

were performed by the sponsor. All study drugs

were supplied by the sponsor. All the authors

vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the

data and the fidelity of the study to the protocol.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated that 2456 patients would need to

undergo randomization at the 200 study centers

to ensure a minimum of 2234 patients who could

be evaluated in order to provide the study with a

power of 90% to determine the noninferiority of

the hazard ratio for exacerbation among patients

in the glucocorticoid-withdrawal group, as compared with the glucocorticoid-continuation group,

with a one-sided alpha level of 0.025 and an expected dropout rate of 15% per year. The assumed median time to the first primary event was

9 months. The prespecified noninferiority margin

of 1.20 was defined as the upper limit of the 95%

confidence interval for the hazard ratio for the

first moderate or severe exacerbation in the glucocorticoid-withdrawal group, as compared with

the glucocorticoid-continuation group. Both efficacy and safety were evaluated in the modified

intention-to-treat population, which was defined

as all patients who received at least one dose of a

study drug.

We used a Cox proportional-hazards regression

model with adjustment for the baseline FEV1 in

Safety

the primary analysis, in the prespecified sensiWe performed physical examinations at the time tivity analysis, and in the analysis of the time to

of screening and at week 52 and measured and the first severe COPD exacerbation. In the sensirecorded vital signs at baseline and at weeks 6, 12, tivity analysis, we included exacerbations in pan engl j med 371;14nejm.orgoctober 2, 2014

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on May 24, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2014 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

1287

The

n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l

of

m e dic i n e

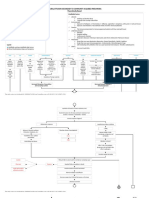

3426 Patients were enrolled

938 Were excluded

72 (7.7%) Had adverse event

679 (72.4%) Did not meet inclusion criteria

or met exclusion criteria

13 (1.4%) Were lost to follow-up

117 (12.5%) Withdrew consent

57 (6.1%) Had other reason

2488 Underwent randomization

1244 Were assigned to glucocorticoid

continuation

1244 Were assigned to glucocorticoid

withdrawal

1243 Were treated

1242 Were treated

231 Discontinued study

101 Had adverse event

6 Had lack of efficacy

23 Did not adhere to study

regimen

7 Were lost to follow-up

61 Declined study

medication

33 Had other reason

227 Discontinued study

108 Had adverse event

6 Had lack of efficacy

27 Did not adhere to study

regimen

9 Were lost to follow-up

48 Declined study

medication

29 Had other reason

1016 (81.7%) Completed study

1011 (81.4%) Completed study

Figure 1. Enrollment and Outcomes.

the patients were men; the mean age was 63.8

years, and the mean FEV1 after bronchodilation

was 0.93 liters, which was 32.8% of the predicted

value. Of the 2485 patients, 2027 completed the

52-week study, including those who received openlabel fluticasone.

Characteristics of the patients at baseline and

dropout rates were similar in the two study groups

(Fig. 1 and Table 1, and Table S2 in the Supple

mentary Appendix). According to the Global Initi

ative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)

criteria, 61.2% of the patients had an FEV1 that

was 30 to 49% of the predicted value (GOLD 3),

and 38.1% of the patients had an FEV1 that was

less

than 30% of the predicted value (GOLD 4).

R e sult s

The percentages of patients receiving inhaled gluPatients

cocorticoids, LABAs, or LAMAs at baseline were

A total of 2485 patients underwent randomization 69.9%, 64.6%, and 46.9%, respectively, with 39.0%

at 200 centers in 23 countries. A total of 82.5% of receiving the three treatments in combination.

tients who were switched to open-label fluticasone. In a post hoc sensitivity analysis of the

primary end point, we removed the covariate from

the model in order to include treated patients

with missing data regarding the baseline FEV1.

In addition, we used the KaplanMeier method

to estimate the probability of a moderate or severe COPD exacerbation. This procedure was repeated for determining the probability of a severe

COPD exacerbation. Additional details regarding the statistical analysis are provided in the

protocol and in Section 4 in the Supplementary

Appendix.

1288

n engl j med 371;14nejm.orgoctober 2, 2014

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on May 24, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2014 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Glucocorticoid Withdr awal and COPD Exacerbations

Table 1. Characteristics of the Patients at Baseline.*

Characteristic

Male sex no. (%)

Glucocorticoid

Continuation

(N=1243)

Glucocorticoid

Withdrawal

(N=1242)

All Patients

(N=2485)

1013 (81.5)

1036 (83.4)

2049 (82.5)

Age yr

63.68.6

64.08.4

Former smoker no. (%)

811 (65.2)

843 (67.9)

1654 (66.6)

63.88.5

Duration of COPD yr

7.755.99

8.006.47

7.876.23

3049%: GOLD 3

760 (61.1)

761 (61.3)

1521 (61.2)

<30%: GOLD 4

473 (38.1)

474 (38.2)

947 (38.1)

Other category

10 (0.8)

7 (0.6)

17 (0.7)

1223

1218

2441

Percentage of predicted FEV1 after

bronchodilation no. (%)

Baseline lung function

Patients with available data no.

FEV1

Value liters

0.970.36

0.980.36

0.980.36

Percentage of predicted value

34.211.2

34.310.8

34.211.0

1238

1237

2475

1.80.9

1.90.9

1.80.9

1136

1126

2262

46.3517.89

45.9118.19

46.1318.04

Score on mMRC scale

Patients with available data no.

Mean score

SGRQ score

Patients with available data no.

Mean score

Medication use no. (%)

LAMA

588 (47.3)

578 (46.5)

1166 (46.9)

LABA

807 (64.9)

798 (64.3)

1605 (64.6)

Inhaled glucocorticoid

876 (70.5)

862 (69.4)

1738 (69.9)

Triple therapy with LAMA, LABA, and inhaled

glucocorticoid, with or without other

pulmonary medication no. (%)**

479 (38.5)

491 (39.5)

970 (39.0)

* Plusminus values are means SD. There were no significant differences between the two groups at baseline on the

basis of t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests or Fishers exact test, as appropriate, for categorical variables.

COPD denotes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 second, GOLD Global Initiative

for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, LABA long-acting -agonist, and LAMA long-acting muscarinic antagonist.

All patients in the study were either current smokers (10 pack-years) or former smokers.

Of the 17 patients in this category, 3 had mild COPD (FEV1, 80% of predicted value, or GOLD 1), 9 had moderate

COPD (FEV1, 50 to 79% of predicted value, or GOLD 2), and 5 had missing values.

Patients for whom baseline lung-function data were available were evaluated after receiving triple therapy during the

run-in period. Usable data regarding lung function were missing for 44 patients at baseline.

Scores on the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating more

severe dyspnea; the absence of breathlessness was given a score of 1. No minimum clinically important difference

has been identified.

Scores on St. Georges Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating worse

function and a minimum clinically important difference of 4 points.

** Other respiratory medications included oral -agonists, oral glucocorticoids, leukotriene-receptor antagonists, mucolytic agents, oxygen, and xanthines.

Overall, 28.2% of patients had cardiac disorders at Primary End Point

baseline, and 45.8% had vascular disorders (Table The hazard ratio for a first moderate or severe

COPD exacerbation was 1.06 (95% confidence inS3 in the Supplementary Appendix).

n engl j med 371;14nejm.orgoctober 2, 2014

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on May 24, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2014 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

1289

The

n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l

A Moderate or Severe COPD Exacerbation

1.0

of

m e dic i n e

B Primary End Point and Sensitivity Analyses

Hazard ratio, 1.06 (95% CI, 0.941.19)

P=0.35 by Walds chi-square test

0.9

Hazard Ratio (95% CI)

Estimated Probability

0.8

Primary end point

0.7

0.94

1.06

1.19

0.95

1.06

1.19

0.6

0.5

IGC withdrawal

IGC

continuation

0.4

0.3

Noninferiority

margin

Primary end point

excluding baseline

FEV1 covariate

0.2

0.1

0.0

Primary end point

including exacerbations

on open-label therapy

12

18

24

30

36

42

48

54

0.8

Weeks to Event

No. at Risk

IGC continuation 1243 1059 927 827 763 694 646 615 581

IGC withdrawal 1242 1090 965 825 740 688 646 607 570

1.0

1.0

1.18

1.1

1.2

1.3

1.4

1.5

IGC Continuation

Better

D Change from Baseline in Trough FEV1

Daily Fluticasone Dose in Withdrawal Group

Hazard ratio, 1.20 (95% CI, 0.981.48)

P=0.08 by Walds chi-square test

0.9

0.9

1.05

IGC

Withdrawal

Better

14

19

C Severe COPD Exacerbation

0.93

Reduced to

500 g

Reduced to

200 g

Reduced to

0 g (placebo)

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

IGC withdrawal

0.1

0.0

IGC continuation

0

12

18

24

30

36

42

48

Adjusted Mean Change

in FEV1 (ml)

Estimated Probability

0.8

20

40

IGC withdrawal

60

80

54

IGC

continuation

P<0.001

P=0.001

0

Weeks to Event

12

18

52

1077

1058

970

935

Week

No. at Risk

No. at Risk

IGC continuation 1243 1180 1117 1066 1026 993 957 928 895

IGC withdrawal 1242 1189 1119 1044 986 941 918 889 863

20

25

IGC continuation 1223

IGC withdrawal 1218

1135

1135

1114

1092

Figure 2. COPD Exacerbations and Lung Function.

Panel A shows KaplanMeier curves for the estimated probability of moderate or severe exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease (COPD) during the study, with no significant difference between the group assigned to withdrawal of inhaled glucocorticoids

(IGC) and the group assigned to continued IGC treatment. Panel B shows a forest plot of hazard ratios for the first COPD exacerbation

(the primary end point), the primary end point including exacerbations during open-label therapy (sensitivity analysis), and the primary

end point excluding the covariate of the baseline forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (sensitivity analysis). All three categories

fall within the prespecified noninferiority margin of 1.20 (the upper limit of the 95% confidence interval for the hazard ratio in the glucocorticoid-withdrawal group as compared with the glucocorticoid-continuation group). Horizontal dashed lines indicate 95% confidence

intervals. Panel C shows KaplanMeier curves for the estimated probability of severe COPD exacerbations, with no significant betweengroup difference. Panel D shows the adjusted mean change from baseline in the FEV1, as measured during clinic visits. In the glucocorticoidwithdrawal group, there was a significant decline in lung function at weeks 18 and 52, as compared with the change from baseline in the

glucocorticoid-continuation group. I bars indicate standard errors. In Panels A and C, the study period ends at 54 weeks because some

visits could not be scheduled at 52 weeks.

terval [CI], 0.94 to 1.19) with glucocorticoid withdrawal as compared with glucocorticoid continuation, which indicated noninferiority, since the

upper limit of the confidence interval was below

1290

the predefined noninferiority margin of 1.20

(Fig. 2A and 2B). The results were similar in a

sensitivity analysis that included exacerbations

occurring after patients had discontinued random-

n engl j med 371;14nejm.orgoctober 2, 2014

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on May 24, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2014 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Glucocorticoid Withdr awal and COPD Exacerbations

ized treatment and in a post hoc analysis that

excluded the FEV1 from the model (Fig. 2B, and

Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). The time

by which 25% of patients had a first moderate or

severe exacerbation (first quartile) was 110 days

in the glucocorticoid-withdrawal group and 107

days in the glucocorticoid-continuation group.

Secondary End Points

The adjusted event rate for moderate or severe

exacerbations was 0.95 per patient-year (95% CI,

0.87 to 1.04) in the glucocorticoid-withdrawal

group and 0.91 per patient-year (95% CI, 0.83 to

0.99) in the glucocorticoid-continuation group.

Analysis of the time to the first severe COPD exacerbation showed a hazard ratio of 1.20 (95% CI,

0.98 to 1.48) for glucocorticoid withdrawal as compared with glucocorticoid continuation (Fig. 2C).

The majority of patients with one or more exacerbations had one or two moderate or severe exacerbations during the study (Fig. S3 and S4 in the

Supplementary Appendix). There were no significant between-group differences in hazard ratios

in any of the subgroup analyses (Fig. 3).

FEV1

At week 18, when glucocorticoid withdrawal was

complete, the adjusted mean reduction from baseline in the trough FEV1 was 38 ml greater in the

glucocorticoid-withdrawal group than in the glucocorticoid-continuation group (P<0.001). A similar between-group difference (43 ml) was seen at

week 52 (Fig. 2D). No significant between-group

differences were observed at weeks 6 and 12.

Health Status

The change from baseline in the mMRC score

did not differ significantly between the glucocorticoid-withdrawal group and the glucocorticoidcontinuation group at week 18 (0.001 and 0.030

points, respectively; P=0.36) or at week 52 (0.035

and 0.028 points, respectively; P=0.06). The

changes from baseline in the total SGRQ scores

were an increase of 0.55 points in the glucocorticoid-withdrawal group and a reduction of 0.42

points in the glucocorticoid-continuation group

at week 27 (P=0.08) and an increase of 1.15 and

a decrease of 0.07, respectively, at week 52

(P=0.047).

Safety

The overall proportion of patients who had one

or more adverse events while receiving the study

treatment was 71.2%, and the proportions were

similar in the two groups (Table 2, and Table S4

in the Supplementary Appendix). Serious adverse

events were reported in 24.2% of the patients in

the glucocorticoid-withdrawal group and 23.5%

of the patients in the glucocorticoid-continuation

group. Rates of fatal adverse events were 3.2% in

the glucocorticoid-withdrawal group and 2.7% in

the glucocorticoid-continuation group.

The incidence of pneumonia was 5.5% in the

glucocorticoid-withdrawal group and 5.8% in

the glucocorticoid-continuation group. The incidence of cardiac adverse events of interest was

similarly balanced between the groups, with major

adverse cardiac events reported in 2.2% of the

patients in the glucocorticoid-withdrawal group

and 2.0% of patients in the glucocorticoid-continuation group. Major adverse cardiac events that

were fatal were reported in 1.5% and 1.1% of the

patients, respectively, and stroke was reported

in 0.5% and 0.7% of the patients, respectively

(Table 2).

Discussion

In our study, in which patients with severe or very

severe COPD received triple therapy with a LAMA,

a LABA, and an inhaled glucocorticoid during a

run-in period, followed by withdrawal of the inhaled glucocorticoid over a 3-month period or

continued triple therapy, the upper limit of the

95% confidence interval for an increase in the

risk of a moderate or severe acute exacerbation

was below the prespecified noninferiority margin

of 1.20 in the glucocorticoid-withdrawal group.

Differences in FEV1 and health status emerged in

the 18-week analysis after inhaled glucocorticoid

treatment was completely withdrawn. We did not

identify any subgroup of patients that had an increased likelihood of an exacerbation after glucocorticoid withdrawal. Since a history of exacerbation and substantial impairment in lung function

were entry criteria, our study population was representative of patients for whom inhaled glucocorticoids are recommended on the basis of

GOLD guidance.1

Most clinical trials involving patients with

COPD have established the benefit of treatment

by comparing a new therapy with placebo or a

relevant active control. Few trials have considered

the question of whether such therapy should be

continued after clinical stability has been achieved,

an approach that is commonly adopted for pa-

n engl j med 371;14nejm.orgoctober 2, 2014

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on May 24, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2014 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

1291

The

Subgroup

n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l

No. of Patients

All patients

Age

<55 yr

55 to <65 yr

65 to <75 yr

75 yr

Sex

Male

Female

Smoking status

Former smoker

Current smoker

Body-mass index

<20

20 to <25

25 to <30

30

IGC at screening

Yes

No

Xanthines at screening

Yes

No

Chronic bronchitis

Yes

No

GOLD stage at screening

3

4

GOLD assessment category at baseline

C

D

Prior antibiotics or systemic glucocorticoids

<2

2

Beta-blockers at screening

Yes

No

of

m e dic i n e

Hazard Ratio (95% CI)

2441

1.06

345

945

883

268

1.04

0.95

1.19

1.06

2010

431

1.08

1.02

1630

811

1.10

0.99

368

912

771

390

0.94

1.17

1.05

0.96

1724

717

1.08

1.00

567

1874

1.15

1.03

1548

891

1.11

0.95

1491

934

1.12

1.00

819

1612

1.15

1.01

1537

903

1.03

1.11

188

2253

0.89

1.07

0.5

1.0

IGC Withdrawal Better

2.0

IGC Continuation Better

Figure 3. Subgroup Analyses of the First Moderate or Severe COPD Exacerbation in All Study Patients.

All categories were evaluated in post hoc analyses except for age, sex, smoking status, and baseline body-mass index. Data with respect to chronic bronchitis were obtained from electronic case-report forms. The size of the diamonds is proportional to the number of patients in the subgroup. The horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence

intervals. Usable data regarding lung function were missing for 44 patients at baseline. GOLD denotes Global

Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.

tients with asthma.13 Initial studies showed that

abrupt withdrawal of inhaled glucocorticoids in

patients with a range of COPD severities led to

more exacerbations and some worsening of lung

function, at least when patients used short-acting

bronchodilators as maintenance treatment.14-17

In our study, we used dual bronchodilation with

salmeterol and tiotropium, which has proved to

1292

be more effective than salmeterol alone in the

prevention of exacerbations.6 Moreover, we withdrew glucocorticoid treatment gradually from a

common baseline of maximized therapy.

In our study, we saw no significant betweengroup difference in the rate of dropout, which

typically occurs more frequently in the placebo

groups in clinical trials.18,19 There was a tran-

n engl j med 371;14nejm.orgoctober 2, 2014

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on May 24, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2014 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Glucocorticoid Withdr awal and COPD Exacerbations

sient increase in the number of severe exacerbations soon after the complete withdrawal of

glucocorticoids, but this increase was not significant and was not sustained during the study

period. We considered a number of subgroups in

which a greater degree of dependence on glucocorticoids might be expected, but we did not find

notable differences in outcomes between inhaled

glucocorticoid withdrawal and continued triple

therapy in any of these subgroups.

After complete withdrawal of glucocorticoids,

we observed a small but significant and persistent between-group difference in the FEV1, with

a larger reduction from the baseline value in the

glucocorticoid-withdrawal group. This change

was similar to that observed in previous trials of

glucocorticoid withdrawal14-17 and in a study of

roflumilast, an oral nonglucocorticoid antiinflammatory drug, in a patient population that was

similar to the one in our study.20 The change in

the FEV1 may represent the spirometric signal

associated with antiinflammatory therapy but

does not seem to be associated with exacerbations, as reported in recent studies of combination therapy with once-daily inhaled glucocorticoids plus LABAs.21In our study, the between-group

difference in FEV1 became apparent only after the

final step of inhaled glucocorticoid withdrawal

(from 200 g to 0 g of fluticasone per day).

We saw no significant effect of glucocorticoid

withdrawal on the mMRC score, but there was a

difference in the total SGRQ score that was

noted during the study period and that favored

continued glucocorticoid therapy. However, the

importance of this finding is unclear, since the

between-group difference was smaller than the

frequently used minimum clinically important

difference22 and was not related to differences in

the number of exacerbations. We saw no significant between-group difference in the safety

profile, including the number of cases of pneumonia. In contrast, other studies have shown an

increase in cases of pneumonia among patients

with COPD who received fluticasone.5,8,21 On the

basis of our study data, we cannot determine

whether our findings with respect to pneumonia

reflect differences in our patient population or a

sustained effect on pneumonia risk in our glucocorticoid-withdrawal group, since patients in

that group received inhaled glucocorticoids for

4 months (including the run-in period); this

question merits future study.

Our study has both strengths and limitations.

Table 2. Adverse Events.*

Variable

Glucocorticoid

Continuation

(N=1243)

Glucocorticoid

Withdrawal

(N=1242)

no. of patients (%)

Adverse events

Any

880 (70.8)

890 (71.7)

Leading to discontinuation

of study drug

115 (9.3)

127 (10.2)

292 (23.5)

300 (24.2)

During study period

34 (2.7)

40 (3.2)

Including vital-status follow-up

38 (3.1)

43 (3.5)

273 (22.0)

271 (21.8)

72 (5.8)

68 (5.5)

Any

25 (2.0)

27 (2.2)

Fatal

14 (1.1)

19 (1.5)

9 (0.7)

6 (0.5)

Serious adverse events

Any

Death

Requiring hospitalization

Adverse events of special interest

Pneumonia

Major adverse cardiac event

Stroke

* A more detailed list of adverse events is provided in Table S4 in the Supple

mentary Appendix.

The preferred terms in the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities

(MedDRA) that were included in the category of pneumonia were bronchopneumonia, lobar pneumonia, pneumonia, pneumonia klebsiella, pneumonia

pneumococcal, and pneumonia streptococcal; the system organ classes that

were included in the category of major adverse cardiac events were cardiac disorders (fatal) and vascular disorders (fatal); the preferred terms were sudden

death, cardiac death, and sudden cardiac death; the Standardized MedDRA

query (SMQ) was ischemic heart disease, and the sub-SMQs were myocardial

infarction (broad) and myocardial infarction (fatal); and those that were included in the category of stroke were cerebellar infarction, cerebral infarction,

cerebrovascular accident, embolic cerebral infarction, ischemic cerebral infarction, ischemic stroke, and transient ischemic attack.

We enrolled substantially more patients than were

enrolled in all previous trials of glucocorticoid

withdrawal combined, which allowed for further

examination of the response in various subgroups.

We had 9 months of observation of patients who

were not receiving glucocorticoids, with no suggestion that exacerbations were occurring more

frequently. It is unlikely that a longer follow-up

period would have changed this conclusion. Our

study population consisted mainly of white men;

we believe that the proportionally smaller enrollment of women was the result of a combination of

disease prevalence in the study countries and the

severity of disease within our population. However,

we observed no significant difference in outcome

on the basis of sex (Fig. 3).

n engl j med 371;14nejm.orgoctober 2, 2014

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on May 24, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2014 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

1293

Glucocorticoid Withdr awal and COPD Exacerbations

In conclusion, we found that in patients with needs to be considered when making decisions

severe but stable COPD who were receiving com- regarding maintenance therapy in patients with

bination therapy with tiotropium, salmeterol, severe but stable COPD.

and glucocorticoids, the stepwise withdrawal of

glucocorticoids was noninferior to the continuaSupported by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with

tion of such therapy, with respect to the risk of

the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

moderate or severe exacerbations. The effect of

We thank Caitlin Watson, Ph.D., of Complete HealthVizion

withdrawal on symptoms and lung function also for medical-writing support.

Appendix

The authors affiliations are as follows: the Pulmonary Research Institute at Lung Clinic Grosshansdorf, Airway Research Center North,

German Center for Lung Research, Grosshansdorf (H.M., A.K., H.W.), Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma, Ingelheim (B.D., K.T.), and the

Department of Sports Medicine, University of Tbingen, Tbingen (K.T.) all in Germany; Servei de Pneumologia, Hospital Clnic

Institut dInvestigacions Biomdiques August Pi i SunyerCIBERES, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona (R.R.-R.); the Departments of

Clinical Research UK (L.T.) and Biometry and Data Management (H.F.), Boehringer Ingelheim, Bracknell, and the Institute of Ageing

and Chronic Disease, University Hospital Aintree, Liverpool (P.M.A.C.) both in the United Kingdom; Odense University Hospital,

Odense, Denmark (R.D.); the Department of Respiratory Diseases, University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium (M.D.); UMR INSERM Unit

1067 CNRS 7733, Aix-Marseille Universit, Department of Respiratory Diseases and CIC Nord, Assistance PubliqueHpitaux de Marseille Hpital Nord, Marseille, France (P.C.); and the Department of Respiratory Medicine, Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, the Netherlands (E.F.M.W.).

References

1. Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, et al.

Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2007;176:532-55.

2. Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agust AG, et al.

Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2013;187:347-65.

3. Wedzicha JA, Brill SE, Allinson JP,

Donaldson GC. Mechanisms and impact

of the frequent exacerbator phenotype in

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

BMC Med 2013;11:181.

4. Burge PS, Calverley PMA, Jones PW,

Spencer S, Anderson JA, Maslen TK. Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled

study of fluticasone propionate in patients

with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the ISOLDE trial.

BMJ 2000;320:1297-303.

5. Calverley PMA, Anderson JA, Celli B,

et al. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2007;

356:775-89.

6. Vogelmeier C, Hederer B, Glaab T, et al.

Tiotropium versus salmeterol for the prevention of exacerbations of COPD. N Engl

J Med 2011;364:1093-103.

7. Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, et al.

A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med

2008;359:1543-54.

8. Wedzicha JA, Calverley PMA, Seemungal TA, Hagan G, Ansari Z, Stockley RA.

The prevention of chronic obstructive pul-

1294

monary disease exacerbations by salmeterol/fluticasone propionate or tiotropium bromide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2008;177:19-26.

9. Magnussen H, Watz H, Kirsten A, et al.

Stepwise withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD patients receiving dual

bronchodilation: WISDOM study design

and rationale. Respir Med 2014;108:593-9.

10. Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM,

Littlejohns P. A self-complete measure of

health status for chronic airflow limitation: the St. Georges Respiratory Questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;145:

1321-7.

11. de Torres JP, Pinto-Plata V, Ingenito E,

et al. Power of outcome measurements to

detect clinically significant changes in

pulmonary rehabilitation of patients with

COPD. Chest 2002;121:1092-8.

12. Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V,

et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur

Respir J 2005;26:319-38.

13. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global

strategy for asthma management and

prevention, revised 2014 (http://www

.ginasthma.org/local/uploads/files/

GINA_Report_2014_Jun11.pdf).

14. Jarad NA, Wedzicha JA, Burge PS, Calverley PMA. An observational study of inhaled corticosteroid withdrawal in stable

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Respir Med 1999;93:161-6.

15. van der Valk P, Monninkhof E, van der

Palen J, Zielhuis G, van Herwaarden C. Effect of discontinuation of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the COPE study.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:135863.

16. Choudhury AB, Dawson CM, Kilving-

ton HE, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in people with COPD in primary care: a randomised controlled trial.

Respir Res 2007;8:93.

17. Wouters EFM, Postma DS, Fokkens B,

et al. Withdrawal of fluticasone propionate from combined salmeterol/fluticasone treatment in patients with COPD

causes immediate and sustained disease

deterioration: a randomised controlled

trial. Thorax 2005;60:480-7.

18. Vestbo J, Anderson JA, Calverley PM,

et al. Bias due to withdrawal in long-term

randomised trials in COPD: evidence

from the TORCH study. Clin Respir J

2011;5:44-9.

19. Calverley PMA, Spencer S, Willits L,

Burge PS, Jones PW. Withdrawal from

treatment as an outcome in the ISOLDE

study of COPD. Chest 2003;124:1350-6.

20. Calverley PMA, Rabe KF, Goehring

U-M, Kristiansen S, Fabbri LM, Martinez FJ.

Roflumilast in symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: two randomised clinical trials. Lancet 2009;374:68594. [Erratum, Lancet 2010;376:1146.]

21. Dransfield MT, Bourbeau J, Jones PW,

et al. Once-daily inhaled fluticasone furoate and vilanterol versus vilanterol only

for prevention of exacerbations of COPD:

two replicate double-blind, parallelgroup, randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med 2013;1:210-23.

22. Jones PW. Estimation and application

of the minimum clinically important difference in COPD. Lancet Respir Med

2014;2:167-9.

Copyright 2014 Massachusetts Medical Society.

n engl j med 371;14nejm.orgoctober 2, 2014

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on May 24, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2014 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- UWorld NCLEX-RN QBank 2018 PDFDokumen103 halamanUWorld NCLEX-RN QBank 2018 PDFIlluminatis99% (90)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Part IIDokumen64 halamanPart IIhussainBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- SOAP NoteDokumen3 halamanSOAP NoteAuliya J'ga BontzBelum ada peringkat

- Obstructive JaundiceDokumen18 halamanObstructive JaundiceBellinda PaterasariBelum ada peringkat

- Key signs and symptoms of respiratory diseasesDokumen35 halamanKey signs and symptoms of respiratory diseasesEmereole FrancesBelum ada peringkat

- Human Respiratory SystemDokumen32 halamanHuman Respiratory SystemOyrik Mukhopadhyay100% (1)

- Berman Ch29 CrsDokumen24 halamanBerman Ch29 CrsKwena100% (1)

- Energy Medicine and DiabetesDokumen66 halamanEnergy Medicine and DiabetesSatinder Bhalla83% (6)

- 12 MRCP PACES Station 5 CasesDokumen23 halaman12 MRCP PACES Station 5 CasesTahir Ali100% (1)

- HAAD ExamDokumen17 halamanHAAD ExamDaniel Alvarez95% (22)

- Krok 2 2012-2019Dokumen59 halamanKrok 2 2012-2019Donya GholamiBelum ada peringkat

- 2Dokumen3 halaman2Tri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- Mata 1Dokumen9 halamanMata 1Tri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- NepalDokumen4 halamanNepalTri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- QwertyDokumen1 halamanQwertyTri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- Tension PneumothoraxDokumen18 halamanTension PneumothoraxTri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- Nejmn 5Dokumen13 halamanNejmn 5Tri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- A Case of Infant Accidental Hanging Caused by A Toy Strap: Ase ReportDokumen3 halamanA Case of Infant Accidental Hanging Caused by A Toy Strap: Ase ReportTri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- Tension PneumothoraxDokumen18 halamanTension PneumothoraxTri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- QwertyDokumen1 halamanQwertyTri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- JP2012 630519 PDFDokumen10 halamanJP2012 630519 PDFFitriatun NisaBelum ada peringkat

- Nejm 4Dokumen19 halamanNejm 4Tri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- Artikel Tri Anna Fitriani - H1a012060Dokumen8 halamanArtikel Tri Anna Fitriani - H1a012060Tri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- Table 2 Preoperative Characteristics and Treatment of Patients Presenting With Complex Anal FistulaDokumen4 halamanTable 2 Preoperative Characteristics and Treatment of Patients Presenting With Complex Anal FistulaTri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- Anthocyanins Induce Cholesterol Efflux From Mouse Peritoneal MacrophagesDokumen10 halamanAnthocyanins Induce Cholesterol Efflux From Mouse Peritoneal MacrophagesTri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- 4Dokumen4 halaman4Tri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- Anal Fistula: Results of Surgical Treatment in A Consecutive Series of PatientsDokumen5 halamanAnal Fistula: Results of Surgical Treatment in A Consecutive Series of PatientsTri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal 1 PDFDokumen7 halamanJurnal 1 PDFTri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- Anthocyanin Prevents CD40-Activated Proinflammatory Signaling in Endothelial Cells by Regulating Cholesterol DistributionDokumen15 halamanAnthocyanin Prevents CD40-Activated Proinflammatory Signaling in Endothelial Cells by Regulating Cholesterol DistributionTri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- Anthocyanin Prevents CD40-Activated Proinflammatory Signaling in Endothelial Cells by Regulating Cholesterol DistributionDokumen15 halamanAnthocyanin Prevents CD40-Activated Proinflammatory Signaling in Endothelial Cells by Regulating Cholesterol DistributionTri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical Study: Nitroglycerin For Management of Retained Placenta: A Multicenter StudyDokumen7 halamanClinical Study: Nitroglycerin For Management of Retained Placenta: A Multicenter StudyTri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- JurnalDokumen7 halamanJurnalTri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- Burkitt's Lymphoma: Causing Obstructive Jaundice in An AdultDokumen3 halamanBurkitt's Lymphoma: Causing Obstructive Jaundice in An AdultTri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- What Are The Markers of Aggressiveness in Prolactinomas? Changes in Cell Biology, Extracellular Matrix Components, Angiogenesis and GeneticsDokumen11 halamanWhat Are The Markers of Aggressiveness in Prolactinomas? Changes in Cell Biology, Extracellular Matrix Components, Angiogenesis and GeneticsTri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- AnggurDokumen8 halamanAnggurTri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- Gastrointestinal Motility Disorders: An Update: Brian E. Lacy Kirsten WeiserDokumen15 halamanGastrointestinal Motility Disorders: An Update: Brian E. Lacy Kirsten WeiserTri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- TyrDokumen7 halamanTyrTri Anna FitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- 3 MAIN B February 23Dokumen13 halaman3 MAIN B February 23Student Access SLMC-IMBelum ada peringkat

- 06章(224 271)Dokumen48 halaman06章(224 271)zhangpengBelum ada peringkat

- Medicine All DIagnosis by AVI SeriesDokumen8 halamanMedicine All DIagnosis by AVI SeriesMuhammad Awais Hassan AwaanBelum ada peringkat

- Medical Terminology For Health Professions 7th Edition Ehrlich Test BankDokumen10 halamanMedical Terminology For Health Professions 7th Edition Ehrlich Test Bankphoebedavid2hqjgm100% (32)

- Pediarespi QuizDokumen1 halamanPediarespi QuizAlessa Mikkah BaltazarBelum ada peringkat

- Ards Case StudyDokumen1 halamanArds Case StudyLyons MacBelum ada peringkat

- Sir ClanDokumen109 halamanSir ClanJames AbendanBelum ada peringkat

- Cardiovascular Examination 1Dokumen43 halamanCardiovascular Examination 1ערין גבאריןBelum ada peringkat

- COPD Guide for GPsDokumen28 halamanCOPD Guide for GPseimearBelum ada peringkat

- Pleural Effusion Secondary To Community Acquired Pneumonia PathophysiologyDokumen5 halamanPleural Effusion Secondary To Community Acquired Pneumonia PathophysiologySteffiBelum ada peringkat

- AEBA QUESTIONS-WPS OfficeDokumen2 halamanAEBA QUESTIONS-WPS OfficeMarj Castor LisondraBelum ada peringkat

- Atypical Manifestations of Acute Coronary Syndrome - Throat Discomfort: A Multi-Center Observational StudyDokumen8 halamanAtypical Manifestations of Acute Coronary Syndrome - Throat Discomfort: A Multi-Center Observational StudyYo MeBelum ada peringkat

- Postoperative Care: Nursing ManagementDokumen25 halamanPostoperative Care: Nursing ManagementHarjotBrarBelum ada peringkat

- Abnormal Breathing PatternsDokumen5 halamanAbnormal Breathing PatternsJonalyn EtongBelum ada peringkat

- CCJM Symptom Management An Important Part of Cancer CareDokumen10 halamanCCJM Symptom Management An Important Part of Cancer CareBrian HarrisBelum ada peringkat

- COPD AsthmaDokumen16 halamanCOPD Asthma09172216507Belum ada peringkat

- BloatDokumen57 halamanBloatHari Krishnaa AthotaBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing Assessment of Patient with Acute Heart FailureDokumen5 halamanNursing Assessment of Patient with Acute Heart FailureShereen AlobinayBelum ada peringkat

- Acute Respiratory FailureDokumen28 halamanAcute Respiratory FailureMohamed Na3eemBelum ada peringkat

- Snakebite Severity Score Flowsheet Algorithm PDFDokumen2 halamanSnakebite Severity Score Flowsheet Algorithm PDFUmbu WindiBelum ada peringkat