ARV Adverse

Diunggah oleh

natinlalaHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

ARV Adverse

Diunggah oleh

natinlalaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

CLINICAL PRACTICE

Behavioral Aspects of HIV Prevention and Care in Indonesia:

A Plea for a Multi-disciplinary, Theory- and Evidencebased Approach

Elmira N Sumintardja*, Lucas WJ Pinxten**, Juke R.L. Siregar*, Harry Suherman***,

Rudy Wisaksana****, Shelly Iskandar*****, Irma A Tasya***, Zahrotur Hinduan*,

Harm J. Hospers**

* Faculty of Psychology, Padjadjaran University. Jl. Pasirkaliki no. 190, Bandung 40151, Indonesia.

** Department of Work and Social Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Neuroscience, Maastricht University,

Maastricht, The Netherlands. *** Health Research Unit, Faculty of Medicine, Padjadjaran University/Hasan Sadikin

Hospital, Bandung, Indonesia. **** Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Padjadjaran University/

Hasan Sadikin Hospital, Bandung, Indonesia. ***** Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine,

Padjajaran University/Hasan Sadikin Hospital, Bandung, Indonesia.

Correspondence mail to: lpinxten@yahoo.com.

ABSTRACT

Projections estimate 1,000,000 HIV infected by 2015 in

Indonesia. Key behaviors to HIV prevention and care are

determined by a complex set of individual/ environmental

factors. This paper presents empirical data, local evidence

and theoretical concepts to determine the role of social

sciences in HIV prevention/care.

Injecting Drug Use (IDU) is a social and very risky

activity: 95% injected in the presence of peers and 49%

reported needles sharing. 82% of IDUs do not use condoms

consistently. Poor adherence to ARV treatment is related to

a complex set of, mostly behavioral, factors beyond effective

influence by standard professional skills of medical staff.

Meta-analysis indicated that about 1/3 of the variance

in behaviour can be explained by the combined effect of

intention and perceived behavioral control, the two

cornerstones of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). It is

advisable to adapt TPB in the light of the Indonesian

context.

Current theories of behavior and behavior change give

professionals of all disciplines, working in HIV prevention

and care, effective tools to change behavior and to improve

HIV prevention and access & quality of HIV care.

Key words: VCT, ARV adherence, injecting drug use, AIDS/

HIV, theory of planned behavior, intervention mapping.

INTRODUCTION

According to UNAIDS and WHO estimates, in Asia

around 5 million people are living with HIV (range: 3.7

million6.7 million). Some Asian countries (Thailand and

Cambodia) managed to halt the HIV epidemic resulting

in an overall declining trend of new infections: from

450,000 in 2001 to 440,000 in 2007.1 Injecting drug use

(IDU) has been identified as a major cause of the

current expansion of the HIV epidemic in Asia.2,3

During the first two decades of the HIV pandemic,

Indonesia was relatively unaffected by the virus.4,5 It

was not until 1999 when a sharp rise in HIV infection in

several subpopulations was recorded. The groups most

affected were intravenous drug users (IDUs) and Sex

Workers (SW) and their clients. An anonymous sentinel

surveillance in Indonesia revealed that in 1999 16% of

IDUs were HIV-infected. This figure rose to 41% in

2000 and to 48% in 2001. In urban areas, HIV-transmission through needle sharing showed an eightfold increase

from 1997 to 2003.6

Current estimates of total HIV infections in

Indonesia range between 190,000 to 400,000 in a nation

of 220 million inhabitants, while prevalence rates of HIV

among different IDU subpopulations in Jakarta range

from 18% to over 90% 7-10 and unsafe injecting

practices are estimated to account for over 75% of all

new HIV infections.9,11 Around the year 2000, approximately one quarter of IDUs in Bandung, Jakarta and

Bali were reported to have engaged in unprotected sex

79

Elmira

with commercially sex workers (SW) in the previous

year.3,10,13 After Jakarta and Papua province (where the

HIV epidemic is primarily heterosexually driven), West

Java is the third worst affected province having an

estimated 22,000 IDUs of which up to 52% are HIVpositive and 21% incarcerated.14,15

Unlike other countries, Indonesia has a quite unique

HIV epidemic: HIV patients mostly (ex-) IDUs and

their spouses are young: 40% of nationally reported

AIDS cases were between 15 and 24 years16 and were

rather well educated: in Jakarta 73% of the IDUs17 had

higher education (high school or beyond) while in

Bandung about 70% had finished senior high school, and

14% of the IDUs had a university degree.18 In the

Bandung RSHS methadone clinic, about 42% of the

patients have a senior high school degree and 31% of

the patients have an academic degree.19

According to the Indonesian National Narcotics

Board, approximately 1% of Indonesias total population

use intravenous drugs, resulting in a concurrent HIV and

IDU epidemic, fuelling through sexual contact between

injectors and non-injectors the Indonesian HIV

epidemic.9,12,20 Unless effective harm reduction targeted

at the most at-risk groups is put in place including clean

needle distribution and adequate condom distribution

scenario studies project at least 1 million HIV infections

by the year 2015.21

On the biomedical front, also in Indonesia, much has

changed in the last decade: multi-drug antiviral (ARV)

regimens have become available, more convenient, less

toxic and, due to generic and off-patent production with

pharmaceutical subsidies and government distribution to

148 designated ARV treatment hospitals, less expensive.

In Bandung, this development is paying off: compared to

the current national mortality figure of 20%22, the

Bandung mortality rate now is 7% one year after

starting ARV.19

Despite this progress, huge challenges still remain in

the field of behavioral aspects of HIV prevention and

care in Indonesia. It is not who a person is but what he

or she does that determines whether one exposes

oneself and/or others to HIV.(after Fishbein, 2000)

Behaviors considered key to HIV prevention and

care are determined by a complex set of individual and

environmental factors. For practical reasons and in

order to gain a better understanding of these individual

and environmental factors, behavioral sciences use

theoretical concepts to model, determine and explain

cognitions, barriers and environmental conditions that

affect behavior of (ex-) IDUs, and other groups at risk,

and their access to and use of services. The

development of HIV prevention and care should be a

80

Acta Med Indones-Indones J Intern Med

well planned evidence and theory-based activity in

order to be effective. 23-25 Especially the use of

behavioral models facilitates all professionals working

in the HIV field to critical analysis of the situation of the

individual, group or the environment in order to develop,

implement and evaluate appropriate and effective

prevention and care interventions.

This paper presents empirical data and theoretical

concepts to determine the role of behavioral sciences in

HIV prevention and care in Indonesia and covers the

following chapters: 1. analysis of the situation/problem;

2. analysis of the behavior at individual and environmental

level (e.g. risky injecting behavior, condom use),

3. analysis of the determinants of the behavior (e.g. group/

peer pressure, self-efficacy), 4. development and pilot

testing of the intervention (e.g. school-based prevention

curriculum, counseling), and 5. implementation of the

intervention (e.g. at schools or at ARV clinics). We will

follow the steps of the Intervention Mapping25 method

to discuss empirical data and theoretical concepts

related to behavioral aspects of HIV prevention and

care, such as: knowledge, attitudes, social norms, risk

perception regarding HIV-related risk behaviors, and

perceived skills related to risk reduction behaviors and

ARV treatment (safer sex; safe injecting, adherence to

ARV treatment).

EVIDENCE ON BEHAVIORAL ASPECTS OF SEXUAL

AND DRUG RELATED RISK BEHAVIORS SUCH AS VCT,

ARV UPTAKE AND ARV ADHERENCE

Next, we will present data of sexual and drugs related risk behaviors among IDUs, leading to health hazards like HIV or HCV infections, as well as local behavioral evidence related to the uptake of VCT, ARV

treatment and adherence.

Sex-related Risk Behavior Among IDU

A 2006 in-depth study of 321 active IDUs in Bandung

revealed that about 15% had a steady partner, that 47%

bought sex in the last year, and that 89% ever had

casual sex partners. Of all respondents, 37% never used

a condom in any sexual contact, 51% did not use a

condom during the last sexual intercourse, 45% reported

to have had unprotected sex with SW the yera before.

Of the 321 surveyed IDUs only 10% of this group had

been tested for HIV.26 According to the 2007 national

bio-behavioral survey, 82% of the Bandung IDUs did

not use condoms consistently and 45% do not use a

condom when having sex with a sex worker.27

Drug-related Risk Behavior Among IDU

The above mentioned 2006 Bandung survey further

showed that the average age of this specific survey

Vol 41 Supplement 1 July 2009

sample was 19 years. The mean age of first illicit drug

use (including alcohol, mushrooms, inhalants, codeine,

ecstasy, marihuana, tranquilizers, cocaine and

amphetamines but excluding tobacco smoking and

injecting drug use) was 16 years and first injection drug

use was at 19 years. Individual risk behavior often is

influenced others: 95% of the IDUs injected in the

presence of peers in 95% of cases and high risk

injecting behavior was common: 49% of IDUs reported

needle sharing in the previous month.18,26,28

Given the high HIV-prevalence and the high

prevalence of risk behaviors among IDU, there is

consensus that this IDU-driven HIV epidemic will

gradually spread to other non-injecting populations, like

partners of IDUs and sex workers.29,30 For example,

we see a steady increase of women in the Bandung

patient group attending the HIV clinic of Rumah Sakit

Hasan Sadikin, most of whom are (ex) spouses of IDU),

who became infected through sexual intercourse.31

Uptake of VCT

Voluntary Counselling and Testing (VCT) is a method

whereby clients or patients with risk behavior (like IDUs

and Sex Workers) are informed about the risks of being

HIV-infected and stimulated to take an HIV test. VCT

is a well proven and cost effective way to increase

knowledge of HIV transmission, to promote behavioral

change, and to stimulate the uptake of health care

services like ARV treatment.32-34 Despite the increase

of VCT testing sites in Indonesia it is estimated that as

many as 70% of the most at risk populations have not

yet found their way to a VCT site.3 Also in Bandung,

VCT is the entry point to HIV services. Ideally VCT

should be accessed before people develop opportunistic

infections or other signs of a diminished immunological

status, but the year before most patients in the Bandung

RSHS decided to go for a VCT test only after being

diagnosed with advanced stage of HIV infection

(median CD4 cell count=193mm2/cell and majority

being advised by health care workers to go for VCT in

the hospital.35

Difficulties with VCT utilization have also been

reported in other countries. Ugandan researchers

evaluating home-based VCT (health workers going door

to door) stated that besides inconvenience of the testing

site, fear of stigmatization and emotional vulnerability and

lack of confidentiality: receiving results in a public

facility (hospital/health centre) were the most common

explanations for the relative popularity of home-based

VCT. 36 Dutch research points out that the main

reason for not taking an HIV test among Men who have

Sex with Men (MSM) was fear of a positive test result

Behavioral Aspects of HIV-prevention and Care in Indonesia

and the perceived psychosocial consequences of this test

result.37 Recent Bandung research points out that IDUs

do not go for VCT because of perceived lack of confidentiality offered at the VCT sites, the costs related to

testing (travel and additional service costs) and perceived

lack of benefits of VCT.38

Access and Adherence to ARV Treatment

As a result, the well education IDUs have a rather

good knowledge on HIV/AIDS.27 But barriers like drug

addiction and/or lack of knowledge about opioid

substitution or ARV treatment probably prevent about

75% of current and former Bandung IDUs having tested

HIV+, to accessed addiction- ARV treatment.39

Access to the Bandung ARV clinic requires, like in

all Indonesian ARV treatment sites, that drug users stop

injecting, abstain from drugs or join a substitution

service. In addition, adherence to ARV treatment is

expected. In the case of ARV for HIV-infection

adherence should be very high (i.e. at least 95% of the

doses taken, and on prescribed times). High adherence

is essential for optimal suppression of the virus load.40,41

Lower adherence is considered as medication failure

which may result in virological failure and ARV drugs

resistance. More recent, research however, indicates that

lower adherence levels (lower than 95%) may achieve

durable viral suppression.42 Poor adherence is common

in short-term treatment regimens like antibiotic courses.43

Reaching and maintaining appropriate adherence levels

to ARV treatment is quite a challenge because ARV

treatment is meant to be life-long. Poor adherence to

ARV treatment is related to a complex set of factors:

regimen related factors like the fit of a complex

regimen to the day to day routines, psychological and

physical adverse/side effects, of the treatment itself44,

socio-economic factors like lack of social support from

family and friends45, patient related factors like: low

self-efficacy and lack of self-control of the requirements

of the ARV treatment, psychological distress,

depression, inadequate confidence in treatment and

providers, knowledge, perceived norms (patients

perception of what others expect him to do) perceived

benefits of treatment related to health outcomes and other

values (being a good parent/partner), forgetfulness,

alcohol and drug use, stigma and fear of discrimination,

poor literacy and cognitive impairment,44,46,47 health

system related factors like lack of clear instruction, inadequate knowledge about relation between adherence

and resistance and poor follow-up and feedback,44 and

condition-related factors like low viral load and

symptoms of HIV like wasting and opportunistic

infections.

81

Elmira

Acta Med Indones-Indones J Intern Med

International research indicates that patients with an

IDU history on ARV treatment, have a lower treatment

adherence level and resulting in poor response rate.48,49

However, ongoing research in Bandung cannot confirm

this: ex-IDU patients on both methadone substitution and

ARV are doing at least as good (in terms of self

reported adherence, and viral/immunological response)

as patients without an IDU history that are on ARV

treatment only.29 It would be worth while relating the

self-reported adherence to a gold standard like electronic

pill registration devices in order to validate the self

reported adherence.

THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOR: A PRACTICAL

MODEL TO ANALYZE COMPLEX BEHAVIOR

There is a general recognition that behavioral

sciences, theory and research can play an important role

in protecting and maintaining public health.51 However,

a recent review indicated that most of the many

behavioral interventions developed in the HIV field,

neither use an evidence-based approach nor draw

explicitly on theories of health behavior. The review

further showed that the Theory of Planned Behavior

(TPB) had its limitations but was one of the most used

and useful theoretical models to determine factors and

mechanisms influencing various HIV related

behaviors.52 A meta-analysis indicated that about 1/3 of

the variance in behaviour can be explained by the

combined effect of intention and perceived behavioral

control, the two cornerstones of the TPB.53

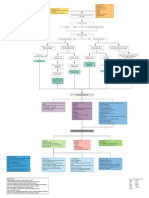

The core of TPB, as illustrated in Figure 1, is the

concept that attitude, subjective (social) norms and

perceived behavioral control (which is similar to

Banduras self-efficacy concept) are the determinants

of motivation, which is usually assessed as the intention

to perform a specific risk or health behavior.54 As an

illustration: the attitude toward learning ones HIV

status is primarily a function of the beliefs about positive

and negative consequences of knowing ones HIV

status. Despite some people knowing about VCT and

the availability of free and easy accessible VCT

centres, they still have certain beliefs (mostly influenced

by others) that influence the balance of perceived

positive and negative consequences of a possible HIV+/

HIV- result of the test. Herewith, the TPB recognizes

that individuals are embedded within interpersonal

relationships, organizations, community and society, and

addresses socio-cultural aspects and incorporates

factors outside the individuals control (like peer

pressure or the opinion of an other important) that may

influence the intention and the actual behavior. As a

result, individuals HIV preventive behaviors, such as

taking up VCT services (in order to know their HIV

status), is a function of individuals cognitions and of the

environment they live in.(24) In Bandung, most people

going for a VCT in RSHS only went for VCT after a

physician or other health care worker told them to check

their status, which suggests negative attitudes towards

testing.35

Subjective or social norms refer to the perceptions

of approval or disapproval of learning of ones HIV

status from significant others (peers, partner, parents).

Ongoing research in Bandung indicates that perceived

lack of confidentiality at the VCT site (individual factor)

and the travel expenses to reach the VCT site

(environmental factor) and perceived fear for

discrimination (individual factor), are the major barriers

to VCT uptake for people at risk. Other Bandung-based

research explains well the distinction between individual

and environmental factor from the research; cost could

Figure 1. Theory of planned behavior (TPB) (Ajzen 1991)

82

Vol 41 Supplement 1 July 2009

be perceived as expensive or cheap to the subjects while

they compare it to the most or less benefit offered by

the services (individual factor) and not by the real

evidence of far or near distance (environmental factor)

they could reach VCT clinic from their residence.38

Self-efficacy/PBC refers to the conviction to be able to

perform the behavior required (coping with bad news or

changing ones life-style or dealing with discrimination)

in learning ones HIV status, whether HIV+ or HIV-.

DEFINING THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF AN EVIDENCE

AND THEORY BASED INTERVENTION: ADHERENCE

TO ARV AS EXAMPLE

Behavioral interventions aiming at changing complex

behavior like sexual risk taking or improving ARV

adherence, are likely to be more effective when based

on evidence of former research and focus on causal

determinants of that specific behavior and when based

on a theoretical concept of behavior and behavior

change. Evidence- and -theory-based interventions also

facilitate evaluation and understanding of the effect of

behavioral interventions, which in their turn feed in the

process of further development of the theoretical

foundations of behavioral interventions. TPB is the most

used and strongest founded theoretical model to predict

a range of behaviors.55,56 Godin and Kok57, reported in

their meta-analysis of 87 TBP studies applied to health

behavior that TPB accounted for 41% of the variance in

behavioral intentions and 34% of the variance in

behavior for a broad range of behaviors. However, TPB

mostly is used as background to understand and explain

the behavior and what to change within the behavior.

However, other theories are mostly used to explain the

Behavioral Aspects of HIV-prevention and Care in Indonesia

behavior change and how to design behavioral

intervention.58

Adherence to ARV, often, (also in Bandung)

measured through self-report is, when linked to more

objective measures like viral load, sub-optimal in about

half of the patients.50,59,60 Very few rigorous evaluations

of interventions to improve ARV adherence are

available.52,61 From a recent Cochrane review we learn

that interventions aiming at improving and strengthening

medication management skills tend to be the most

effective approach to adherence improvement.62 As

discussed before, adherence is embedded, supported,

facilitated and often frustrated by complex behaviors.63

In defining the determinants of this adherence behavior

TPB can, despite its limitations, be very helpful.52 In

order to develop an intervention to improve adherence

to ARV, De Bruin & Hospers et al adapted the TPB

model into concise behavioral components for a

medication adherence model.63

Based on TPB, De Bruin & Hospers propose the

intention of the patient to adhere as the key

determinant. As illustrated in the above model: intention

is determined by 3 factors: subjective norm: what do

specific others like the nurse, physician or partner

expect the patient to do, attitude: the patients belief, in

terms of perceived costs and benefits outcome his/her

adherence behavior, and the perceived behavioral

control (PBC) consisting of self efficacy: perceived ease

(yes I can!) to perform a certain adherence behavior

and the controllability, how much grip the patient has

on the desired and optimal adherence behavior in

different day to day settings.

Figure 2. Behavioral model for medication adherence (De Bruin & Hospers 2005)

83

Elmira

Ideally, an intervention to optimize adherence, uses

all three factors as building blocks to design a tailor-made

intervention in order to influence the intention and actual

adherence behavior: use peers, partner, or professional

to influence the patients norm, change the attitude of

the patient through effective and/or persuasive

communication. In order to influence PBC and self

efficacy (the last building block) it is advisable to

breakdown desired outcome behavior in sub goals,

facilitate this behavior (using adherence organizers like

pill boxes, electronic reminders), plan together with the

patient the execution of the desired adherence behavior

(fitting ARV treatment into the patients daily life) and

introduce self-monitoring and feedback mechanisms to

improve the awareness, reinforce desired behavior and

develop routine in ARV medication. De Bruin & Hospers

developed a 9 step intervention protocol using all above

mentioned behavioral determinants: knowledge improvement, definition of desired behavioral outcome and HIV

status, joined planning and reinforcement of desired

adherence behavior introducing adherence data and self

monitoring as feedback mechanism, defining causes of

(non-) adherence. This multi-disciplinary intervention

implemented in the Amsterdam Academic Medical

Centre outpatient clinic, resulted in an increase of mean

adherence from 82% to 93%. The Bandung ARV clinic

currently is developing a protocol, based on TPB, to study

and subsequently to design an intervention to improve

adherence to ARV.

According to the medication adherence model,

demographic and social/cultural aspects are minor

variables and are supposed to play an indirect role in

influencing behavior. However, current Bandung research

on access to VCT indicates that HIV patients only seek

VCT only after receiving the advice from a physician to

go for HIV testing.35 This observation confirms Conner

and Armitage64 advise to extend the TPB towards

inclusion of two new variables: self-identity: the way a

person relates his/her behavior to societal goals and moral

norms: the persons feeling to perform or not to perform

a particular behavior. In Indonesia social, cultural,

societal goals and societal influenced (group) norms

strongly determine behavior and it would be advisable to

adapt TPB and redefine these variables in the light of

the Indonesian context. When applied appropriatly and

used in the perspective of the targeted population, TPB

can be cultural specific.

DISCUSSION

Also in Indonesia, professionals face challenges to

change behaviors that are relevant in the field of HIV.

84

Acta Med Indones-Indones J Intern Med

Behaviors considered key to HIV prevention and care

are determined by a complex set of individual and

environmental factors. As pointed out, a well planned,

multi-disciplinary, evidence- and theory based approach

to influencing behavior can contribute a lot to improve

HIV prevention and access and quality of HIV care. In

order to identify determinants of specific risk- or health

behavior, current theories of behavior and behavior

change give all professionals working in prevention and

care effective tools to change behavior. TPB stands out

as particular useful for the HIV field but for practical

and theoretical reasons it needs more and appropriate

conceptualization, definition and explanation. For instance:

Bandungbased research, based on the TPB indicates

that IDUs intention (behavioral intention) is more

affected by the significant others (i.e, parent, peers) when

they ask them to do so (subjective norms) instead of

taking VCT as self-awareness (perceived behavioral

control), despite they have enough relevant knowledge

about the VCT services.38 This result illustrated nicely

that in decision making on what to do or not to do

(behavior intention) Indonesians are strongly influenced

by the value of collective culture, (based on what others

say) to a specific issue. This cultural specific

information,is very important input in the design process

of behavior (change) interventions that work in

Indonesia. As explained before, adherence to ARV as

another example, while description by TPB model is

embedded, supported, and facilitated by complex

behaviors, which can be explained and described through

the intercorrelation of each components in TPB model.

Anyhow, more evidences needed further explaination of

how variance of socio-demographic characteristics and

personality traits, correlated with behavior intention;

which sometimes means as limitation of TPB

explanation or application, so in practice need further

study and research to the approach itself to empower

the utility of the concept. It is advisable to adapt TPB in

the light of the Indonesian context.

CONCLUSION

As mentioned above, high risk behaviors to HIV/

AID (i.e. sharing needles, and sex-related behavior) can

not only be explained by a merely medical conceptual

approach. It needs also explanation based on behavioral

science concepts, as well as medical, and even cultural

concepts to describe the behavior intention, attitude,

perceived belief, or subjective norms, to gain a clear

picture and understanding of the behavior and to make

plan and conduct intervention for behavioral change in

further action. For this purpose researchers can use the

Vol 41 Supplement 1 July 2009

advantages of TPB as a useful overall model to describe

the relation and link of many important components as

reflected by the theory. Therefore, researchers, medical

-and behavioral sciences practitioners and interventionists are challenged to better understand and correctly

utilize existing empirically supported behavioral theories

like TPB, in the process of developing and evaluating

effective behavioral interventions in HIV prevention and

care.

REFERENCES

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

UNAIDS. Redefining AIDS in Asia: crafting an effective

response. Report of the Commission on AIDS in Asia. Bangkok:

UNAIDS; 2008.

UNAIDS. Epidemiological fact sheets on HIV/AIDS and

sexually transmitted infections-Indonesia- 2006. Geneva:

UNAIDS; 2006.

UNAIDS. AIDS epidemic update-2007. Geneva: UNAIDS;

2007.

NAC. HIV/AIDS in Indonesia: challenges and opportunities

for action. Jakarta: National AIDS Control Commission; 2001.

Republic of Indonesia, MOH tables contained in January 1997.

World Bank report no. 32572. Project performance assessment

report, Indonesia. HIV/AIDS and STDs prevention and

management project (LOAN NO. 3981). Jakarta: Ministry of

Health; 2005.

Pisani E, Garnett GP, Brown T, Stover J, Grassly NC, Hankins

C. et al. Back to basics in HIV-prevention: focus on exposure.

BMJ. 2003;326:1384-7.

UNAIDS. Epidemiological fact sheets on HIV and AIDS,

epidemiological core data on epidemiology and response.

Indonesia-Update 2008. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2008.

Indonesia Review: evidence to action. Available from: URL:

h t t p : / / w w w. a i d s d a t a h u b . o r g / f i l e s / d o c u m e n t s /

Indonesia_review_(FINAL_revision_2_08).pdf. Cited: April

04 2009.

Family Health International. AIDS in Asia; face the facts.

Bangkok: FHI; 2004.

Pisani E, Dadun, Sucahya PK, Kamil O, Jazan S. Sexual

behavior among injecting drug users in 3 Indonesian cities

carries a high potential for HIV spread to non-injectors. J Acquir

Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;34(4):403-6.

Pisani E, Lazzari S, Walker N, Schwartlander B. HIV

surveillance: a global perspective. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr.

2003;32(Suppl.1):S3-11.

Saidel TJ, Des Jarlais DC, Peerapatanapokin W, Dorabjee J,

Sing S, Brown T. Potential impact of HIV among IDU on

heterosexual transmission in Asian settings: scenarios from the

Asian Epidemic Mode. Intern J Drug Policy. 2003;14:63-74.

Setiawan M, Patten J, Triadi A, Yulianto S, Adnyana T, Arif

M. Report on injecting drug use in Bali (Denpasar and Kuta):

results of an interview survey. Intern J Drug Policy. 1999;

10:109-16.

NAC. Country report on the following up to the declaration of

commitment on HIV/AIDS. UNGASS reporting period 20062007. Jakarta: National Aids Committee; 2008.

UNAIDS. Epidemiological fact sheets on HIV/AIDS and

sexually transmitted infections. Jakarta: UNAIDS; 2006.

Behavioral Aspects of HIV-prevention and Care in Indonesia

16. Anasrul SR, Fonny S. HIV/Young people among injecting drug

users cited from WHO/Searo fact sheet. Available from: URL:

http://www.searo.who.int/LinkFiles/Fact_Sheets_IndonesiaAHD-07.pdf, cited on April 16, 2009.

17. Kort de GL, Batra S, Nassirimanesh B, Pasaribu R, Ul-Hassan

S. Through the eye of the needle. International Conference on

AIDS. 15th ed. Bangkok, Thailand: 2004.

18. Boom J, Ven van der A , Iskander S, Hidayat T, Basar D, Zain T,

Crevel van R, Jong de C, Pinxten WJL. Needle exchange and

injection related risk behavior among intravenous drug users in

Bandung/ West Java. Poster presentation for the 2007 Open

Science Meeting Bali, November 15-18.

19. Unpublished data from routine reporting of Project IMPACT

and Dr. Hasan Sadikin Hospital. Bandung: Indonesia; 2009.

20. Indonesian office of the coordinating minister for peoples health/

national AIDS commission. National HIV/AIDS strategy.

Jakarta: National Aids Commission; 2007.

21. Impacts of HIV/AIDS 2005-2025 in Papua New Guinea,

Indonesia and East Timor. Final report of HIV epidemiological

modeling and impact study. Government of Australia: AUSAID,

Canberra: February 2006.

22. Ministry of Health Indonesia. Results ART in Indonesia:

Treatment situation until December 2008 (report in Indonesian language). Jakarta: Sub-Directorate HIV/AIDS/Ministry

of Health Indonesia; 2008.

23. Bartholomew KL, Parcel GS, Kok G. Intervention mapping: a

process for designing theory- and evidence-based health

education programs. Hlth Educ Behav. 1998;25:545-63.

24. Kok G. Targeted prevention for people with HIV/AIDS:

Feasible and desirable? Patient Education and Counseling. 1999;

36:239-46.

25. Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH. Planning

health promotion programs: an intervention mapping approach.

2nd ed. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 2006.

26. Pinxten WJL, Boom J, Basar D, Iskander S, Hidayat T, Kamil

V, Zain T, Ven van der A, Hospers HJ. Sexual risk behavior and

low condom use among intravenous drug users in Bandung/

West Java. Poster presentation for the 2007 Open Science

Meeting Bali, November 15-18.

27. Ministry of Health, Statistics Indonesia, and National AIDS

Commission, Integrated biological-behavioral surveillance among

most-at-risk-groups (MARG) in Indonesia 2007. Surveillance

highlights: injecting drug users. 2008: Jakarta.

28. Santoso RR. The overt aggression pathway of male

adolescence in Bandung: The influence of personality trait,

parents discipline styles, and peers. Unpublished dissertation, Post Graduate Program University of Padjadjaran,

Bandung, 2009, 231-233, 262-267, 271

29. Monitoring the AIDS Pandemic (MAP) Network. Available

from: URL: http:// www.mapnetwork.org/reports.shtml. Cited

5 march 2009.

30. Jones GW, et al. Prostitution in Indonesia. In: Lim LL, editor.

The sex sector: the economic and social bases of prostitution in

South-east Asia. Geneva: ILO; 1998. p. 52-7.

31. Wisaksana R, Indrati A, Rogayah E, Sudjana P, Djajakusumah

TS, Ven van der A, Crevel van R. Response to highly active

antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected patients with and

without a history of injecting drug use in Indonesia. Bandung:

IMPACT unpublished publication; 2009.

32. Bateganya MH, Abdulwadud OA, Kiene SM. Home-based HIV

voluntary counseling and testing in developing countries.

Cochrane Database. 2007;4:CD006493.

85

Elmira

33. Sweat M, Gregorich S, Sangiwa G, Furlonge C, Balmer D,

Kamenga C, Grinstead O, Coates T. Cost-effectiveness of

voluntary HIV-1 counseling and testing in reducing sexual

transmission of HIV-1 in Kenya and Tanzania. The Lancet.

2000;356(9224):113-21.

34. De Zoysa I, Phillips KA, Kamenga MC, OReilly KR, Sweat

MD, White RA, Grinstead OA, Coates TJ. Role of HIV

counseling and testing in changing risk behavior in developing

countries. AIDS. 1995;9(Suppl A):S95-101.

35. Hinduan ZR, Kesumah N, Crevel van R, Hospers HJ. Factors

associated with up taking voluntary counseling and testing

(VCT): a review of literature and empirical evidence from Dr.

Hasan Sadikin Hopital in Bandung, West Java, Indonesia.

Bandung: IMPACT unpublished publication; 2009.

36. Wolff B, Nyanzi B, Katongole G, Ssesanga D, Ruberantwari A,

Whitworth J. Evaluation of a home-based voluntary counseling

and testing intervention in rural Uganda. Health Policy Plan.

2005;20(2):109-16.

37. Mikolajczak J, Hospers HJ, Kok G. Reasons for not taking a

HIV-test among untested men who have sex with men: an

internet study. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;4(10):431-5.

38. Suherman H, Sodjakusumah TI, Fitriana E, Puspitasari TS,

Sumintardja EN, Pinxten WJL, Tasya IA, Hospers HJ.

Perceived barriers of taking HIV test (VCT) among IDUs in

Bandung. Bandung: IMPACT unpublished publication; 2009.

39. Iskander S, Basar D, Hidayat T, Siregar IM, Pinxten WJL,

Crevel van R, Ven van der A, Jong de C. The risk behavior

among current and former Injection Drug Users (IDUs) in

Bandung, West Java, Indonesia. Bandung: IMPACT

unpublished publication; 2009.

40. Paterson DL, Swidells S, Mohr J, Bresters M, Vergis EN, Squier

C, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitors, HIV-1 viral load, and

outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med.

2000;133:21-30.

41. McNabb J, Ross JW, Abriola K, Turley C, Nightingale CH,

Nicolau DP. Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy

predicts virological outcome at an inner-city human immunodeficiency virus clinic. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;133:700-5.

42. Bangsberg DR, Weiser S, Guzman D, Riley E. 95% Adherence

is not necessary for viral suppression to less than 400 copies/

ml in the majority of individuals on NNRTI regimens. Twelfth

Conference on retroviruses and opportunistic infections. 2005;

poster 616.

43. Hawkins NJ, Butler CC, Wood F. Antibiotics in the

community: a typology of user behaviors. Patient Educ Couns.

2008;73(1):146-52.

44. Ammassari A, Trotta MP, Murri R, Castelli, F, Narciso P,

Noto P, et al. Correlates and predictors of adherence to highly

active antiretroviral therapy: overview of published research.

J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31(Suppl. 3):S123-S7.

45. World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapy:

evidence for action. Geneva: WHO; 2003.

46. Pence BW, Thielman NM, Whetten K, Ostermann J, Kumar V,

Mugavero MJ. Coping strategies and patterns of alcohol and

drug use among HIV-infected patients in the United StatesSoutheast. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;11:869-77.

47. Talam NC, Gatongi P, Rotich J, Kimaiyo S. Factors affecting

antiretroviral drug adherence among HIV/AIDS adult patients

attending HIV/AIDS clinic at Moi teaching and referral

hospital, Eldoret, Kenya. East Afr J Public Health. 2008;5(2):

74-8.

86

Acta Med Indones-Indones J Intern Med

48. Waldrop-Valverde D, Jones DL, Weiss S, Kumar M, Metsch L.

The effects of low literacy and cognitive impairment on

medication adherence in HIV-positive injecting drug users. AIDS

Care. 2008;20(10):1202-10.

49. Braitsten P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, Schechter M, Boulle A,

Moitti P, et al. Mortality of HIV-1 infected patients in the first

year of antiviral therapy; comparison between low-income and

high-income countries. Lancet. 2006;356(6513):817-24.

50. Nieuwkerk PT, Oort FJ. Self-reported adherence to

antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infection and virological

treatment response; a meta analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic

Syndr. 2001;38(4):445-8.

51. Fishbein M. The role of theory in HIV prevention. AIDS Care.

2000;12(3):273-8.

52. Munro S, Lewin L, Swart T, Volmink J. A review of health

behavior theories: how useful are these for developing

interventions to promote long term medication adherence for

TB and HIV/AIDS? BMC Public Health. 2007;7:104.

Available from:URL: http://www.biomedcentral.com/14712458/7/104. cited January 26, 2009.

53. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM. Health behavior and health

education. In: Theory Research and Practice. 3rd ed. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. p. 74-81.

54. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational

Behavior and Human Decision Process. 1991;50:179-211.

55. Armitage CJ, Conner M. Social cognition models and health

behavior: a structured review. Psychology and Health. 2000;

15:173-89.

56. Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned

behavior: a meta-analytic view. British J Soc Psychol. 2001;

40:471-99.

57. Godin G, Kok G. The theory of planned behavior: a review of

its applications to health-related behaviors. American J Health

Promotion.1996;1:87-98.

58. Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles M.

From theory to intervention: mapping theoretical derived

behavioral determinants to behavior change techniques.

Applied Psychology: an international review. 2008;574:66080.

59. Shah B, Walshe L, Saple DG, Mehta,S, Ramnani JP, Kharkar

RC, Gupta B, Gupta A. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy

and virological suppression among HIV-infected persons

receiving care in private clinics in Mumbai, India. Clin

Infect Dis. 2007;44:1235-44.

60. Guarinieri M. Highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence:

the patients point of view. JAIDS. 2002;31:167-9.

61. Simoni JM, Frick PA, Pantalone DW, Turner BJ. Antiretroviral

adherence interventions: a review of current literature and

ongoing studies. Top HIV Med. 2003;11:185-98.

62. Rueda S, Park-Wyllie LY, Bayoumi A, Tynan AM, Antoniou,

Rourke S, Glazier R. Patient support and education for

promoting adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Cochrane collaboration 2009: http://www.thecochranelibrary.

com cited on January 26, 2009.

63. De Bruin M, Hospers HJ, Borne van de HW, Kok G, Prins JM.

Theory and evidence-based intervention to improve adherence

to antiretroviral theory in The Netherlands: a pilot study. AIDS

Patient Care and STDs. 2005;19(6):384-94.

64. Conner M, Armitage CJ. Extending the theory of planned

behavior: a review and avenues for further research. J Applied

Soc Psychol. 1998;28:146-9.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Roles of MicroRNAs On Tuberculosis InfectionDokumen23 halamanThe Roles of MicroRNAs On Tuberculosis InfectionnatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- MicroRNA-17 Untuk BCGDokumen12 halamanMicroRNA-17 Untuk BCGnatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- microRNA 146aDokumen11 halamanmicroRNA 146anatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Host-Directed Therapy of Tuberculosis - What Is in It For MicroRNADokumen4 halamanHost-Directed Therapy of Tuberculosis - What Is in It For MicroRNAnatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Mir 155Dokumen7 halamanMir 155natinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Mirna - MDR MTBDokumen7 halamanMirna - MDR MTBnatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- Tinjauan miRNA PDFDokumen11 halamanTinjauan miRNA PDFnatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Perseption HivDokumen6 halamanPerseption HivnatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- microRNA 146aDokumen11 halamanmicroRNA 146anatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Mirna - MDR MTBDokumen7 halamanMirna - MDR MTBnatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Hiv/aids ..Dokumen22 halamanHiv/aids ..natinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Boateng2013 PDFDokumen8 halamanBoateng2013 PDFnatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- Amfoterisin B - HPLCDokumen6 halamanAmfoterisin B - HPLCnatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Formulasi Tablet VaginalDokumen9 halamanFormulasi Tablet VaginalnatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Amfoterisin BDokumen4 halamanAmfoterisin BnatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- Sativa: Blood Glucose Lowering Effect of Nigella in Alloxan Induced Diabetic RatsDokumen4 halamanSativa: Blood Glucose Lowering Effect of Nigella in Alloxan Induced Diabetic RatsnatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- What Is Conjunctivitis and Pink Eye?Dokumen2 halamanWhat Is Conjunctivitis and Pink Eye?natinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- AntimikrobaaDokumen6 halamanAntimikrobaanatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- PWDT YeeeyDokumen5 halamanPWDT YeeeynatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Polimorfisme TransporterDokumen7 halamanPolimorfisme TransporternatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Sativa: Blood Glucose Lowering Effect of Nigella in Alloxan Induced Diabetic RatsDokumen4 halamanSativa: Blood Glucose Lowering Effect of Nigella in Alloxan Induced Diabetic RatsnatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- FarmakogenomiikDokumen5 halamanFarmakogenomiiknatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- Susceptibility - of - Common - Bacterial Respiratory Pathogens To Antimicrobial Agents in Outpatients From South Backa DistrictDokumen7 halamanSusceptibility - of - Common - Bacterial Respiratory Pathogens To Antimicrobial Agents in Outpatients From South Backa DistrictnatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- Goossens tcm18-198315Dokumen83 halamanGoossens tcm18-198315Just MahasiswaBelum ada peringkat

- On Being The Right Size - The Impact of Population Size and Stochastic Effects On The Evolution of Drug Resistance in Hospitals and The Community PDFDokumen11 halamanOn Being The Right Size - The Impact of Population Size and Stochastic Effects On The Evolution of Drug Resistance in Hospitals and The Community PDFnatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- Antimicrobial Use and Indication-Based Prescribing Among General Practitioners in Eastern Croatia - Comparison With Data From The European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption ProjectDokumen10 halamanAntimicrobial Use and Indication-Based Prescribing Among General Practitioners in Eastern Croatia - Comparison With Data From The European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption ProjectnatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- Impact of First-Line Antifungal Agents On The Outcomes and Costs of CandidemiaDokumen7 halamanImpact of First-Line Antifungal Agents On The Outcomes and Costs of CandidemianatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (120)

- Hypoglycemic and Hepatoprotective Effects of Processed Aloe Vera Gel 2155 6156.1000303Dokumen6 halamanHypoglycemic and Hepatoprotective Effects of Processed Aloe Vera Gel 2155 6156.1000303Eric GibsonBelum ada peringkat

- 56 e F 05 PDFDokumen5 halaman56 e F 05 PDFnatinlalaBelum ada peringkat

- Standard of Care in DentistryDokumen8 halamanStandard of Care in DentistryKavitha P. DasBelum ada peringkat

- Child Health Problems GlobalDokumen86 halamanChild Health Problems GlobalBagus P Agen SuplierBelum ada peringkat

- Design NICUDokumen74 halamanDesign NICUMonica SurduBelum ada peringkat

- Final Exam of Dental Material: by Samir AlbahranyDokumen72 halamanFinal Exam of Dental Material: by Samir AlbahranyMustafa H. KadhimBelum ada peringkat

- Cleansing and Moist Greg Goodman 2009Dokumen1 halamanCleansing and Moist Greg Goodman 2009Prajnamita Manindhya El FarahBelum ada peringkat

- NP1 Nursing Board Exam June 2008 Answer KeyDokumen15 halamanNP1 Nursing Board Exam June 2008 Answer KeyBettina SanchezBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction To PainDokumen21 halamanIntroduction To Painayanle Abdi AliBelum ada peringkat

- HIQA Residential Care Standards 2008Dokumen86 halamanHIQA Residential Care Standards 2008Debora Tolentino Grossi0% (1)

- 9 1 EndosDokumen6 halaman9 1 EndosmghBelum ada peringkat

- PASSMED MRCP MCQs-INFECTIOUS DISEASES CompleteDokumen131 halamanPASSMED MRCP MCQs-INFECTIOUS DISEASES CompleteStarlight100% (1)

- Chemicals, Pharmaceuticals, Oil, Dairy, Food, Beverages, Paint & Others Industry DetailsDokumen12 halamanChemicals, Pharmaceuticals, Oil, Dairy, Food, Beverages, Paint & Others Industry DetailsSuzikline Engineering100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- How Can The Game End You?Dokumen1 halamanHow Can The Game End You?leikastarry NightBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluasi Penatalaksanaan Prolanis Di Puskesmas Kota BengkuluDokumen11 halamanEvaluasi Penatalaksanaan Prolanis Di Puskesmas Kota Bengkulunanasila02Belum ada peringkat

- 2021.10.27 Letter To NIHDokumen14 halaman2021.10.27 Letter To NIHZerohedge Janitor100% (1)

- Alginate ImpressionDokumen60 halamanAlginate ImpressionNugraha AnggaBelum ada peringkat

- Myocardial Infarction With CABG Concept MapDokumen1 halamanMyocardial Infarction With CABG Concept MapMaria Therese100% (1)

- Psychiatrist in Pune - Dr. Niket KasarDokumen8 halamanPsychiatrist in Pune - Dr. Niket KasarDr. Niket KasarBelum ada peringkat

- Patients ' Views of Wearable Devices and Ai in Healthcare: Findings From The Compare E-CohortDokumen8 halamanPatients ' Views of Wearable Devices and Ai in Healthcare: Findings From The Compare E-CohortPratush RajpurohitBelum ada peringkat

- Otago 1 PDFDokumen3 halamanOtago 1 PDFAde Maghvira PutriBelum ada peringkat

- Reflex Anal Dilatation An Observational Study On Non-Abused ChildrenDokumen5 halamanReflex Anal Dilatation An Observational Study On Non-Abused Childrenaniendyawijaya0% (1)

- Pathophysiology (Cervical Cancer) Case StudyDokumen7 halamanPathophysiology (Cervical Cancer) Case StudyRosalie Valdez Espiritu100% (2)

- Vehling Annika ResumeDokumen1 halamanVehling Annika Resumeapi-733364471Belum ada peringkat

- Burning Mouth SyndromeDokumen40 halamanBurning Mouth SyndromeSuci Sylvana HrpBelum ada peringkat

- Case Study 2Dokumen3 halamanCase Study 2XilcaBelum ada peringkat

- CystoclysisDokumen29 halamanCystoclysisKate PedzBelum ada peringkat

- Unit 11 FormatDokumen15 halamanUnit 11 Formatapi-26148150Belum ada peringkat

- Gambaran Kebutuhan Keluarga Pasien Diruang Intensif: Literature Review Nurhidayatul Nadya Gamya Tri Utami, Riri NovayelindaDokumen10 halamanGambaran Kebutuhan Keluarga Pasien Diruang Intensif: Literature Review Nurhidayatul Nadya Gamya Tri Utami, Riri Novayelindagamma kurnia mahananiBelum ada peringkat

- Palmer - Final CoachingDokumen9 halamanPalmer - Final CoachingDonald SebidanBelum ada peringkat

- Depression and Heart Disease - Johns Hopkins Women's Cardiovascular Health CenterDokumen3 halamanDepression and Heart Disease - Johns Hopkins Women's Cardiovascular Health CenterSanjay KumarBelum ada peringkat

- PrediabetesDokumen8 halamanPrediabetesVimal NishadBelum ada peringkat

- Healing Your Aloneness: Finding Love and Wholeness Through Your Inner ChildDari EverandHealing Your Aloneness: Finding Love and Wholeness Through Your Inner ChildPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (9)

- Breaking Addiction: A 7-Step Handbook for Ending Any AddictionDari EverandBreaking Addiction: A 7-Step Handbook for Ending Any AddictionPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (2)

- Save Me from Myself: How I Found God, Quit Korn, Kicked Drugs, and Lived to Tell My StoryDari EverandSave Me from Myself: How I Found God, Quit Korn, Kicked Drugs, and Lived to Tell My StoryBelum ada peringkat

- Allen Carr's Easy Way to Quit Vaping: Get Free from JUUL, IQOS, Disposables, Tanks or any other Nicotine ProductDari EverandAllen Carr's Easy Way to Quit Vaping: Get Free from JUUL, IQOS, Disposables, Tanks or any other Nicotine ProductPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (31)

- Allen Carr's Easy Way to Quit Smoking Without Willpower: The best-selling quit smoking method updated for the 21st centuryDari EverandAllen Carr's Easy Way to Quit Smoking Without Willpower: The best-selling quit smoking method updated for the 21st centuryPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (47)

- Stop Drinking Now: The original Easyway methodDari EverandStop Drinking Now: The original Easyway methodPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (28)