Schools of Linguistics

Diunggah oleh

Raedmemphis0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

144 tayangan2 halamanIt talks about the schools of linguistics

Judul Asli

schools of linguistics

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniIt talks about the schools of linguistics

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

144 tayangan2 halamanSchools of Linguistics

Diunggah oleh

RaedmemphisIt talks about the schools of linguistics

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 2

Book Reviews

apologetics and linearity: arguments from the past

are far too often selectively cited to serve in presentday controversies; and far too often, too, the men of

the past are judged by the answer to the question:

what did they know or fail to know that we now hold

to be true. There is always the peril of missing inconspicuous but centrally important shifts in terminology and of imputing irrelevant preconceptions to

our predecessors. The continuity of our discipline is

indeed a fact, but an exceedingly subtle one.

The somewhat overwhelming truth is still that in

order to understand the history of a field of learning

one must understand the subject matter as well as

the wider intellectual history of the time. One of the

many necessary approaches to this difficult goal is

neglected at the moment: intellectual biography of

the type that steers clear of anecdote and human

interest in the journalistic sense but instead goes

into matters of outlook and training and also, insofar

as possible, into the matter of personality in a more

sophisticated sense. For this reason the two handsome volumes under review are a perfect godsend.

Seventy-four scholars of the past, from Jones (d.

1794) to Edgerton (d. 1963) are represented, some

with more than one piece. Many selections are

obituaries written under the fresh impact of the

subjects death. Others are more properly historical

in their claim to detachment, written as they are

from a later vantage point, if usually also in a commemorative context.

Though imbued with the flavor of the graveyard (I, p. xii), the obituaries written by contemporaries are the more valuable. Many of the authors

are indeed distinguished men. Their judgments can

be most interesting, especially when the essay departs from the merely laudatory. [It may be apropos

to note that nine names appear both as subjects and

as authors. Another bit of idle statistics: in about the

same space, the first volume accommodates 36 essays, the second, 54.Obituaries have become shorter

and perhaps also less informative.] Mostly, however,

one reads them for academic-biographic information: to learn (or be reminded) who attended the

university with whom, who sided against whom in

controversies too ephemeral to survive in print or

sufficiently unpleasant to be repressed or distorted in

self-testimony, but remembered and offered as background for some part of the record by a sensitive and

usually sympathetic comrade-in-arms. Next to correspondence (of which there is, unfortunately, no

overabundance) these sketches are our best source of

information. Johannes Schmidts biographical paper

on August Schleicher (I, pp. 37439.5)illustrates the

value of such information as an antidote to the inescapable deceptiveness of autobiography, especially in the case of a highly creative personality like

Schleichers. The strong influence on Schleicher of

the classicist Ritschl continued beyond his student

years. How plausible it is, therefore, to see in some of

Schleichers ideas the reflex of early training in

423

formal manuscript work. Schleichers interpretation

of his own thinking was quite different, and he did

himself the most formidable injustice by insisting,

for all posterity as it were, on the importance of his

quasi-Darwinistic outlook. For reasons of this kind

the reader feels a little pang of disappointment a t not

finding Hermann G. Grassmann, the mathematician,

Sanskritist, and linguist, among the subjects, although a biographical appendix of sorts is published

in his collected works. This is not to say, however,

that it would be anything but foolish to find fault

with Sebeoks selection, which is a masterpiece of

both service and good taste.

Anthropologists will be particularly interested in

the items on Humboldt (two, by very eminent men,

Alfred Dove and Heymann Steinthal), Bohtlingk

(by Berthold Delbrtick), Reguly (by Josef PApay,

rescued from a rather hard to get publication),

Meinhof (one by Clement M. Doke, and another by

Doke and G r a r d Paul Estrade), Boas (one by

Murray B. Emeneau and one by Roman Jakobson),

Uhlenbeck (by J. P. B. de Josselin de Jong), Finck

(by Ernst Lewy), P. Wilhelm Schmidt (by Arnold

Burgmann), Kroeber (by Dell Hymes), Sapir (by

Carl F. Voegelin), and Whorf (by John B. Carroll).

The printing is accurate and beautiful to the point

of lavishness. The works usefulness, as proclaimed

in the subtitle, a biographical source book for the

history of western linguistics, 1746-1963, is as great

as its attractiveness, even where we do not admire

the necrologists judgment unreservedly. It is a very

bright feather, indeed, in the cap of the editor, the

editorial committee of the Studies, and the Indiana

Press.

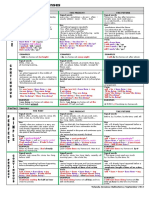

The Linguistic School of Prague: An Introduction to

its Theory and Practice. JOSEF VACHEK.

(Indiana

University Studies in the History and Theory of

Linguistics.) Bloomington & London: Indiana

University Press, 1966. 184 pp., 3 appendices,

selected bibliography, index of names, index of

subjects, notes. $6.00, 38s.

Reviewed by E D WSTANKIEWICZ

~

University of Chicago

The book under review is the third in a series of

works written by Professor Vachek intended to present to a wider public the achievements of the

Prague School of linguistics. The Sturm und Drang

period of that school fell within the years 1926-1939,

and its most important contributions are contained

in the eight volumes of the Trauaux du Cerde LinguistiquedcPrague(1929-1939). As these volumes are

not easily accessible and many of its articles were

written in Slavic languages, the fame of that school

has often rested more on secondhand information

than on an intimate knowledge of its tenets and of its

formulations of linguistic problems. Professor

Vacheks former works, the Dictionnaire de 1 h ~

guistique de 1Ecolc de Prague (1960)and the Prague

424

American Anlhropologisl

School Reader in Lingziisfics (1964), have made

available to the Western reader the terminology and

the main body of Prague linguistic writings; this

book is an attempt a t a synthesis and a critical

evaluation.

The book contains eight chapters, three appendices, a bibliography of the pertinent literature, and

an index of names and subjects. The eight chapters

present the various aspects of Prague linguistic

theory that have determined the particular brand of

structuralism that sets it apart from other structuralist schools, such as American descriptivism and

Copenhagen glossematics. The longest and best

chapter of the book is, predictably, the one devoted

to phonology, which constituted the main contribution of the Prague School to modern linguistics. The

other chapters include historical background, problems of morphonology and morphology, syntax, the

Standard language and orthography, esthetics, and

future prospectives.

Professor Vachek traces the development of the

concept of the phoneme from its early stage, when it

was interpreted as a psychological entity, until the

late 1930s when it was redefined by Jakobson as a

bundle of distinctive features. He also shows how

the many-sided study of phonology has led to an

exploration of the various functions and styles of

language. He particularly emphasizes the great

contribution of Prague linguistics to questions of

diachronic processes, which were misunderstood and

largely neglected by Western structuralists (beginning with de Saussure). Vacheks comments on the

whence and whither of historical change recapitulate the older Prague views, with the addition

of some sociological interpretations of recent Prague

vintage. On the whole, the discussion leaves some

major issues unsolved. An excellent supplement to it

is the reprinted article by B. Trnka (Appendix 111),

one of the finest thinkers of the Prague Circle.

Trnkas article contributes also to our better understanding of the intellectual climate that gave rise to

the new developments in linguistics. The chapters on

morphology and syntax are more modest in scope,

reflecting in part the lesser interest of the Circle in

the semantic levels of language. The narrowing of

outlook is, however, also due in part to the authors

lack of discrimination between the more important

and seminal works, and the works that tried mechanically to transplant the notions of phonology to

that of the higher, more complex levels. Thus there is

no doubt that the morphological studies of Karcevski (on derivation and on the adverb) and of

Jakobson (on the Russian verb and case-system),

which are mentioned in passing, have contributed

far more to a broadening of the structuralist horizon

than the studies on semes and morphemes that the

author discusses in detail. There can likewise he

little doubt that the work of the Prague School on

poetics and versilication was of greater import than

its contributions to questions of Standard language

and orthography, though the elaboration of the

[70,19681

latter testifies, as well, to the scope and breadth of

the linguistic interests of the Circle.

What is most disappointing about Professor

Vacheks book, however, is the tacit assumption

that the so-called Prague

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (894)

- Pronunciation of Chants PDFDokumen3 halamanPronunciation of Chants PDFtomasiskoBelum ada peringkat

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- LIN60904 - KR 1 - Notes - 2Dokumen5 halamanLIN60904 - KR 1 - Notes - 2wicelineBelum ada peringkat

- 1087494table of English Tenses 130929193446 Phpapp02Dokumen1 halaman1087494table of English Tenses 130929193446 Phpapp02zulBelum ada peringkat

- (Oxford Studies in Theoretical Linguistics) Laura J. Downing-Canonical Forms in Prosodic Morphology - Oxford University Press, USA (2006) PDFDokumen296 halaman(Oxford Studies in Theoretical Linguistics) Laura J. Downing-Canonical Forms in Prosodic Morphology - Oxford University Press, USA (2006) PDFCarlos WagnerBelum ada peringkat

- William O'Grady's LanguageDokumen15 halamanWilliam O'Grady's LanguageAmera Sherif100% (1)

- COURSE OUTLINE English Phonetics and PhonollgyDokumen5 halamanCOURSE OUTLINE English Phonetics and PhonollgyHafid MahmudiBelum ada peringkat

- Main Issues in Translation StudiesDokumen50 halamanMain Issues in Translation StudiesRaedmemphis100% (4)

- The Morpheme - A Theoretical Introduction 2015Dokumen263 halamanThe Morpheme - A Theoretical Introduction 2015BakshiBelum ada peringkat

- Translationtheory 140422125604 Phpapp02 2Dokumen39 halamanTranslationtheory 140422125604 Phpapp02 2RaedmemphisBelum ada peringkat

- Text Analysis 2Dokumen1 halamanText Analysis 2RaedmemphisBelum ada peringkat

- Priorities For Research in Sociolinguistics in AfricaDokumen8 halamanPriorities For Research in Sociolinguistics in AfricaRaedmemphisBelum ada peringkat

- Commercial Terminologies PDFDokumen42 halamanCommercial Terminologies PDFCheikh AbdelkaderBelum ada peringkat

- 616 1899 1 PBDokumen10 halaman616 1899 1 PBRaedmemphisBelum ada peringkat

- PhD Translation Studies ApplicationDokumen3 halamanPhD Translation Studies ApplicationRaedmemphisBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction Research Work 2010 CCCDokumen42 halamanIntroduction Research Work 2010 CCCAmmar Mustafa Mahadi AlzeinBelum ada peringkat

- Nida, EugeneDokumen8 halamanNida, EugeneRaedmemphisBelum ada peringkat

- Errors in English Translations of Euphemism in the Holy QuranDokumen8 halamanErrors in English Translations of Euphemism in the Holy QuranRaedmemphisBelum ada peringkat

- GlossaryDokumen11 halamanGlossaryMilan JuríkBelum ada peringkat

- Glossary of Grammar and Punctuation Terms - Nettleham Junior 2015Dokumen12 halamanGlossary of Grammar and Punctuation Terms - Nettleham Junior 2015RaedmemphisBelum ada peringkat

- English Grammar Terms and ExamplesDokumen25 halamanEnglish Grammar Terms and ExamplesRaedmemphisBelum ada peringkat

- Writing Process PDFDokumen3 halamanWriting Process PDFRaedmemphisBelum ada peringkat

- MorphologyDokumen11 halamanMorphologyAhmed ElsamahyBelum ada peringkat

- Powerful English SpeakingDokumen14 halamanPowerful English Speakinghussein1789100% (8)

- Key Works in English by Eugene A. Nida: Elected IbliographyDokumen4 halamanKey Works in English by Eugene A. Nida: Elected IbliographyRaedmemphisBelum ada peringkat

- Character-Based Pivot Translation For Under-Resourced Languages and DomainsDokumen11 halamanCharacter-Based Pivot Translation For Under-Resourced Languages and DomainsRaedmemphisBelum ada peringkat

- Call For Applications 2017 20181701191427Dokumen16 halamanCall For Applications 2017 20181701191427RaedmemphisBelum ada peringkat

- Steiner, George PDFDokumen6 halamanSteiner, George PDFdouifi98100% (1)

- GJ JHK HDokumen36 halamanGJ JHK HRaedmemphisBelum ada peringkat

- Communicative Activity Hi-BegIntermediate-Transitive and Intransitive VerbsDokumen2 halamanCommunicative Activity Hi-BegIntermediate-Transitive and Intransitive VerbsRaedmemphisBelum ada peringkat

- Meeting New PeopleDokumen3 halamanMeeting New PeopleRaedmemphisBelum ada peringkat

- Language The Social Fact PDFDokumen19 halamanLanguage The Social Fact PDFRaedmemphisBelum ada peringkat

- Disney Language GenderDokumen44 halamanDisney Language Genderrosdan1808996Belum ada peringkat

- Myths4 GefnderDokumen40 halamanMyths4 Gefnderrepolho1234Belum ada peringkat

- 3 - Smoking Bio & LabDokumen3 halaman3 - Smoking Bio & LabRaedmemphisBelum ada peringkat

- 1 - Cell Bio & Lab PDFDokumen2 halaman1 - Cell Bio & Lab PDFRaedmemphisBelum ada peringkat

- Unit 8 English Phonological System Ii: Consonants. Phonetic Symbols. Comparison With The Official Language of The Corresponding Autonomous CommunityDokumen15 halamanUnit 8 English Phonological System Ii: Consonants. Phonetic Symbols. Comparison With The Official Language of The Corresponding Autonomous CommunitydianaBelum ada peringkat

- Speech Sounds Phonetics: Is The Study of Speech SoundsDokumen9 halamanSpeech Sounds Phonetics: Is The Study of Speech SoundsIvete MedranoBelum ada peringkat

- Communicative EnglishDokumen64 halamanCommunicative Englishkarthika4aBelum ada peringkat

- MCA Lab ManualDokumen5 halamanMCA Lab ManualV SATYA KISHOREBelum ada peringkat

- JQS TransliterationDokumen1 halamanJQS TransliterationAlBelum ada peringkat

- EnglishDokumen139 halamanEnglishCalvin AugestoBelum ada peringkat

- Workshop On Tone, TypologyDokumen15 halamanWorkshop On Tone, TypologyNaing KhengBelum ada peringkat

- Akmajian Demers Farmer Harnish Linguistics An Introduction To Language and CommunicationDokumen309 halamanAkmajian Demers Farmer Harnish Linguistics An Introduction To Language and CommunicationJase HarrisonBelum ada peringkat

- AUTHORS: Bieswanger, Markus Becker, Annette TITLE: IntroductionDokumen7 halamanAUTHORS: Bieswanger, Markus Becker, Annette TITLE: IntroductionDinha GorgisBelum ada peringkat

- Suprasegmental FeaturesDokumen11 halamanSuprasegmental FeaturesHilya NabilaBelum ada peringkat

- Phonetics & Phonology - Notes by Azmi SirDokumen9 halamanPhonetics & Phonology - Notes by Azmi SirArni TasfiaBelum ada peringkat

- Commonly Confused Suffixes: -able vs -ibleDokumen8 halamanCommonly Confused Suffixes: -able vs -ibleOana DinuBelum ada peringkat

- Fonfon Knjiga PDFDokumen185 halamanFonfon Knjiga PDFkomary komarassBelum ada peringkat

- Comparativre and Superlative 5 OdgovoriDokumen2 halamanComparativre and Superlative 5 OdgovoriТомо ТомескиBelum ada peringkat

- Connected Speech: Communication.... Chat... Talk... Sing..Dokumen16 halamanConnected Speech: Communication.... Chat... Talk... Sing..Dilrabo KoshevaBelum ada peringkat

- Spelling - 4th Grade - Entire YearDokumen13 halamanSpelling - 4th Grade - Entire Yearapi-296950398Belum ada peringkat

- Chapter Overview of Language Teaching MethodsDokumen17 halamanChapter Overview of Language Teaching MethodsMilton Acevedo SaireBelum ada peringkat

- Thracian Language and Greek and Thracian EpigraphyDokumen30 halamanThracian Language and Greek and Thracian EpigraphymilosmouBelum ada peringkat

- Midterm TQ 2011EDokumen10 halamanMidterm TQ 2011EAisyah KarinaBelum ada peringkat

- Etymological Dictionary of Greek and Pre-GreekDokumen34 halamanEtymological Dictionary of Greek and Pre-GreekPhilip AndrewsBelum ada peringkat

- English OrthographyDokumen22 halamanEnglish OrthographyTrajano1234100% (1)

- Singing Exam RubricDokumen1 halamanSinging Exam RubrichannaBelum ada peringkat

- Sounds of EnglishDokumen103 halamanSounds of EnglishSequeTon EnloBelum ada peringkat

- Opos 7Dokumen8 halamanOpos 7ESTHER AVELLABelum ada peringkat