Childhood Gynecomastia: A Mini Review

Diunggah oleh

Peertechz Publications Inc.Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Childhood Gynecomastia: A Mini Review

Diunggah oleh

Peertechz Publications Inc.Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

International Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism

Nasir AM Al Jurayyan*

Mini Review

Professor and Senior Consultant Pediatric

Endocrinologist, Endocrine Division, Department

of Pediatrics, College of Medicine and King Khalid

University Hospital, King Saud University, Riyadh,

Saudi Arabia

Childhood Gynecomastia: A Mini

Review

Dates: Received: 16 June, 2016; Accepted: 18

July, 2016; Published: 22 July, 2016

*Corresponding author: Nasir A.M. Al Jurayyan,

Department of Paediatrics (39), College of Medicine

& King Khalid University Hospital, PO Box 2925,

Riyadh 11461, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi

Arabia, Tel: 00966-11-4670807; Fax: 00966-114671506; E-mail:

www.peertechz.com

Abstract

Gynecomastia, referred to enlargement of the males breast tissue is a common finding in boys

during childhood. Although most cases are benign and self-limited, it may be a sign of an underlying

systemic disease or even drug induced. Rarely, it may represent male breast cancer. Understanding

its pathogenesis is crucial to distinguish a normal developmental variant from pathological cases.

This review will highlight the pathophysiology, etiology, diagnosis and various medical and surgical

therapies.

Keywords: Childhood; Diagnosis; Gynecomastia;

Pathogenesis; Therapy

Introduction

Gynecomastia, referred to enlargement of the male breast tissue

(Figure 1), it is a common finding in childhood reported to be between

30 and 60%. Although, most cases are benign and self-limited, it

may be a sign of an underlying systemic disease or drug-induced.

It is usually bilateral but sometimes unilateral, and results from

proliferation of the glandular component of the breast. It is defined

clinically by the presence of a rubbery or firm mass extending concentrically from the nipple. Gynecomastia should be differentiated

from peusogynecomastia (lipomastia), which is characterized by

desposition of fat without, glandular proliferation [1-6].

In this brief review we highlight the pathophysiology, etiology,

diagnosis and discuss the various modalities of therapy (medical and

surgical).

Pathophysiology

The mechanism and pathophysiology of gynecomastia are not

really clear (Figure 2). However, the major cause in believed to be an

altered imbalance between estrogen and androgen effects, absolute

increase in estrogen effects either an increase in estrogen production,

relative decrease in androgen production, or a combination of both.

Estrogen acts as a growth hormone of the breast and, therefore,

excess of estradiol in men leads to breast enlargement by inducing

Figure 2: Pathophysiological mechanisms leading to gynecomastia.

ductal epithelial hyperplasia, dual elongation and branching, and the

proliferation of periductal fibroblasts and vascularity. Local tissue

factors in the breast can also be important, for example, increased

aromatic activity that can cause excessive local production of

estrogen, decreased estrogen degradation and changes in the levels or

activity of estrogen, and androgen receptors.

Although prolactin (PRL) receptors are present in male breast

tissue, hyperprolacticemia may lead to gynecomastia through effects

on the hypothalamia causing central hypogonadism. Activation

of PRL, also, leads to decreased androgens and increased estrogen

and progesterone receptors. The role of PRL, progesterone and

other growth factors such as insulin like growth factors (IGF-1) and

epidermal growth factor (EGF), in the development of gynecomastia

need to be clarified [5-10].

Classification

The spectrum of gynecomastia severity has been categorized into

a grading system [11]:

Figure 1: A 15 year old boy with gynecomastia.

Grade I

Minor enlargement, no skin excess

Grade II

Moderate enlargement, no skin excess

Grade III

Moderate enlargement, skin excess

Grade IV

Marked enlargement, skin excess

Citation: Al Jurayyan NA (2016) Childhood Gynecomastia: A Mini Review. Int J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2(1): 012-015.

012

Al Jurayyan (2016)

Etiology of gynemastia

Table 2: Drug related gynecomastia.

Generally can be subdivided, according to the cause, into; (Table

1) [12-24].

Drug

Physiological: Estrogen levels rise during neonatal and pubertal

period, which leads to an elevated estrogen/testosterone ration and,

hence, gynecomastia the condition usually regress within two years

of onset.

Estrogens, including topical preperations

Aromatisable androgens

hCG

Digitoxin, herbal products

GnRH agonistor antagonist

Leydig cell damage or inhibition

Pathological: Gynecomastia can occur at any age, as a result

of a number of medical conditions such as liver cirhossis primary

hypogonadism and trauma.

Ketoconazole, Metronidazole

Medicational: Medication induced gynecomastia is the most

common cause. Agents associated with gynecomastia are listed in

Table 2.

Flutamide, bicalutamide

Diagnosis of Gynecomastia

Metoclopramide, Verapamil

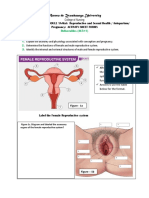

The history and physical examination should direct the laboratory

and radiological imaging studies (Figure 3).

Isoniazid, Amiodarone, Antidepressants

Spironolactone, cancer chemotherapy

Finasteride or dutasteride

Spironolactone, cancer chemotherapy

Cimetidine, Marijuana

Antipsychotic Agents

Human GH, Proton pump inhibitors

Highly active retroviral therapy

Clinical Evaluation: (History and physical examinations)

All boys with gynecomastia should be evaluated thoroughly by an

experienced clinician. A detailed history should include the onset and

duration of the breast enlargement, pain or tenderness, weight loss

or gain, nipple discharge, virilization, medication history, and family

history of gynecomastia which may suggest androgen insensitivity

syndrome, familial aromatase excess or sestoli cell tumours. Physical

examination should differentiate between true gynecomastia and

pseudogynecomastia and should include signs of tomours, liver and

kidney diseases, or hyperthyroidism and should also include genital

examination [5,6,25-31].

Table 1: Gynecomastia related conditions.

Physiological

Neonatal

Pubertal

Involutional

Pathological

Diagnostic testing

In cases without a clear cause, laboratory investigations should

be pursued and must include liver, kidney and thyroid function tests

as well as hormonal tests, estrogen, and free testosterone, luteinizing

hormone (LH) , follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), prolactin,

human chorlonic gonadtrophin (HCG), dehydro epiandrosterone

sulphate (DHEA-SO4) and Feto protein ( FP). If testes are small

the patients Karyotype should be obtained to roll out Klinefelters

Syndrome. Mammography (MMG) is the primary imaging when

there is any suspicion of malignancy. Breast ultrasonography (USG),

scrotal USG and abdominal computerized tomography (CT) of the

abdomen can also be used as well as magnetic resonance imaging of

the pituitary. A percutaneous biopsy should be taken, at times, when

it is difficult to differentiate gynecomastia and breast cancer [5,6,3236].

Treatment of gynecomastia

Androgen insensitivity syndromes

Most cases of gynecomastia regress overtime without treatment.

However, if gynecomastia is caused by an underlying conditions

such hypogonadism, malnutrition or Cirrhosis, that condition may

need treatment. If the patient taking medications that can cause

gynecomastia, the clinician may recommend stopping or substituting

them with other medication. In adolescents with no apparent cause,

gynecomastia often goes away without treatment in less than 2

years. Reassurance and frequent follow up 3-6 months thats what

needed. However, treatment may be necessary if gynecomastia does

not improve on its own or if it causes significant pain tenderness or

embarrassment [1,6,37].

Aromatase excess syndrome

Medical treatment

Stressfull life events

Although no medical treatment cause complete regression of

gynecomastia, they may provide partial regression, or symptomatic

relief. Several agents regulate the hormonal imbalance. The major

medical intervention options are androgens, anti-estrogens and

aromatase inhibitors. Androgen testosterone replacement can be

Cirrhosis/liver disease

Starvation

Male hypogonadism (Primary or secondary)

Testicular neoplasms (germ cell tumours, leydig cell tumours, sex-cord

tumours)

Hyperthyroidism

Renal failure and dialysis

Feminizing adrenocortical tumours

Ectopic HCG production

True hermaphroditism

Type 1 DM

Kennedy's syndrome

Drugs

Idiopathic

Citation: Al Jurayyan NA (2016) Childhood Gynecomastia: A Mini Review. Int J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2(1): 012-015.

013

Al Jurayyan (2016)

Patient Presents with breast enlargement

Is the patient a new born?

Yes

No

Is the patient taking a medication Yes

or substance listed in Table 2)

No

likely transplacental, should

Resolve within four weeks

Discontinue agent and

monitor for resolution

Perform Physical examination

Testicular mass

Breast mass that raises

Suspicion for malignancy

Perform testicular

Ultrasonography

Perform mammography

and breast ultrasonography

With biopsy

Unremarkable

examination

Gynecomastia

Provide reassurance

Pseudogynecomastia

Test hepatic function and

measure creatinine and thyroid

stimulating hormone levels

Evidence of chronic disease? Yes

No

Recommend

weight loss

Treat Underlying disease

Measure serum human chorlonic Gonadotropin,

Dehydro epiandrosterone sulphate, luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating Hormone,

estradiol, testosterone, and prolactin levels

High level of estradiol and low

Level of luteinizing hormone

Perform testicular

Ultrasonography

High level of prolactin

Perform magnetic

resonance imaging

For pituitary adenoma

High level of

human chronic

Gonadotropin

Perform testicular

Ultrasonography

for germ cell tumor

Low levels of

luteinizing hormone

and testosterone

Secondary

hypogonadism

High level of luteinizing

hormone and low level

of testosterone

All hormone

levels normal

Primary hypogonadism

Idiopathic

Gynecomastia

Ultrasonography results normal

Consider exogenous estrogen use, stress, or

Underlying chronic disease as possible cause

Figure 3: Algorithm for the diagnosis of gynecomastia.

used to improve gynecomastia secondary to hypogonadism. Topical

preparations are preferable as they lead to more steady state levels

of testosterone in the body as compared with the injectable forms,

which can worsen breast enlargement by aromatizing to estardiol.

In recent years, anti-estrogens such as tamoxifen and anastrozole

has been shown to be effective. More studies are needed to assess

the effectiveness of aromatose inhibitors such as anastrozle and

testalactone, which are powerful agents that block estrogen [32,3843].

Surgical treatment

Surgical treatment should be individualized to each patient.

Numerous techniques have been described for the correction of

gynecomastia and the surgery is forced with a wide range of excisional

and liposuction procedures. The most frequently encountered

complication was a residual subareolar lump. Although skin excess

remains a challenge, it can be satisfactorily managed without excessive

scarring. A practical approach to the surgical management of

gynecomastia, should take into account breast size, consistency, skin

excess and skin quality. However generally it is not recommended

until the testis has reached adult size, because if surgery is performed

before achieving puberty, breast tissue may regrow [44-47].

If pseudogynecomastia is suspected no work up is needed and

the patient can be reassured that weight loss will lead to resolution of

pseudogynecomastia. If necessary liposuction procedures can reduce

breast enlargement secondary to subareolar fat accumulation.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Ms. Cecile Sael for typing the

manuscript, and extend his thanks and appreciation to Miss Hadeel

N. Al Jurayyan for her help in preparing this manuscript.

References

1. Glenn D, Braunstein MD (2007) Gynecomastia. N Engl J Med 357:12291237.

2. Lazala C, Saenger P (2002) Pubertal Gynecomastia. J Pediatr Endocrinol

Metab 15: 553-560.

3. De Sanctis V, Bernasconi S, Bona G, Bozzola M, Buzi F, et al. (2002) Pubertal

gynecomastia. Minerva Pediatr 54: 357-361.

4. Nordt CA, DiVasta AD (2008) Gynecomastia in adolescents. Curr opin

Pediatr 20: 375-382.

5. Cuhaci N, Polat SB, Evranos B, Ersoy R, Cakir B (2014) Gynecomastia:

Clinical evaluation and management. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 18: 150-158.

6. Dickson G (2012) Gynecomastia. Am Fam Physician 85: 716-722.

7. Barros AC, Sampaio MD (2012) Gynecomastia: pathophysiology, evaluation

and treatment. So Paulo Med J 130: 187-197.

8. Narula HS, Carlson HE (2014) Gynecomastia-pathophysiology, diagnosis

and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol 10: 684-698.

Citation: Al Jurayyan NA (2016) Childhood Gynecomastia: A Mini Review. Int J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2(1): 012-015.

014

Al Jurayyan (2016)

9. Farthing MJ, Green JR, Edwards CR, Dawson AM (1982) Progesterone,

prolactin and gynecomastia in men with liver disease. Gut 23: 276-279.

30. Biro FM, Lucky AW, Huster GA, Morrison JA (1990) Hormonal studies and

physical examination in adolescents gynecomastia. J Pediatr 116: 450-455.

10. Ladizinski B, Lee KC, Nutan FN, Higgins HW, Federman DG (2014)

Gynecomastia; Etiologies, Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis and Management.

South Med J 107: 44-49.

31. Hassan HC, Cullen IM, Casey RG, Rogers E (2008) Gynaecomastia: an

endocrine manifestation of testicular cancer. Andrologia 40: 152-157.

11. Wollina U, Goldman A (2011) Minimally invasive esthetic procedures of the

male breast. J Cosmetic dermatol 10: 150-155.

32. Plourde PV, Kulin HE, Santner SJ (1983) Clomiphene in the treatment of

adolescent gynecomastia, Clinical and endocrine studies. AM J Dis Child

137: 1080-1082.

12. Bhasin S (2008) Testicular disorders. in; Kroneberg HM, Palonsky KS, Larson

PR editors. William textbook of Endocrinology. 11th ed, Philadelpia Saunders

Elsevier.

33. Sansone A, Romanelli F, Sansone M, Lenzi A, Di Luigi L (2016) Gynecomastia

and hormone. Endocrine PMID 27145756.

13. Nuttall FQ (2010) Gynecomastia. Mayo Clin Proc 85: 961-962.

34. La Franchi SH, Parlow AF, Lippe BM, Coyotupa J, Kaplan SA (1975) Pubertal

gynecomastia and transient elevation of serum estradiol level. Am J Dis Child

129: 927-931.

14. Lanfranco F, Kamischke A, Zitzmann M, Nieschlag E (2004) Klinefelters

Syndrome. Lancet 364: 273-283.

15. Handelsman DJ, Dong Q (1993) Hypothalamo-pituitary gonadal axis in

chronic renal failure. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 22: 145-161.

35. Bridenstein M, Bell BK, Rothman MS (2003) Gynecomastia in McDermott

MT,ed Endocrine secrets Am ed Philadelphia, PA elserver sanders Chig 40.

16. Karagiannis A, Harsoulis F (2005) Gonadal dysfunction in systemic diseases.

Eur J Endocrinol 152: 501-513.

36. Munoz CR, Alvarez BM, Munoz GE, Raya PJL, Martinez PM (2010)

Mammography and ultrasound in evaluation of male breast disease. Eur

Radiol 20: 2797-2805.

17. Layman LC (2007) Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Endocrinol Metab Clin

North Am 36: 283-296.

37. Ruth EJ, Cindy AK, M Hassan M (2011) Gynecomastia evaluation and current

treatment options. Ther Clin Risk Manag 7: 145-148.

18. Fentiman IS, Fourquet A, Hortobagyi GN (2006) Male breast cancer. Lancet

367: 595-604.

38. Lapid O, van Wingerden JJ, Perlemuter L (2013) Tamoxifen therapy for

the management of pubertal gynecomastia: a systematic review. J Pediatr

Endocrinol Metab 26: 803-807.

19. Eckman A, Dobs A (2008) Drug-induced gynecomastia. Expert Opin Drug Saf

7: 691-702.

20. Thompson DF, Carter JR

Pharmacotherapy 13: 37-45.

(1993)

Drug

-induced

gynecomastia.

21. Goldman RD (2010) Drug-induced gynecomastia in children and adolescents.

Canadian Family physician 56: 344-345.

22. Deepinder F, Braunstein GD (2012) Drug-Induced Gynecomastia: an

evidence based review. Expert Opin Drug Saf 11: 779-795.

23. Basaria S (2010) Androgen abuse in athletes: detection and consequences.

J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95: 1533-1543.

24. Goh SY, Loh KC (2001) Gynecomastia and the herbal tonic Dong Quai

Singapore Med J 42:115-116.

25. Bembo SA, Carlson HE (2004) Gynecomastia: its features, and when and

how to treat it. Cleve Clin J Med 71: 511-517.

26. Gikas P, Mokbel K (2007) Management of gynecomastia: an update. Int J

Clin Pract 61: 1209-1215.

27. Carlson HE (2011) Approach to the patients with gynecomastia. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab 96: 15-21.

28. Dobs A, Darkes MJ (2005) Incidence and management of gynecomastia in

men treated for prostate cancer. J Urol 174: 1737-1742.

29. Derkacz M, Chmiel-Perzynskal, Nowakoski A (2011) Gynecomasti- a difficult

diagnostic problem. Endokrynol Pol 62: 190-202.

39. Khan HN, Rampaul R, Blamey RW (2004) Management of physiological

gynaecomastia with tamoxifen. Breast 13: 61-65.

40. Lawrence SE, Faught KA, Vethamuthu J, Lawson ML (2004) Beneficial

effects of raloxifene and tamoxifen in the treatment of pubertal gynecomastia.

J Pediatr 145: 71-76.

41. Mauras N, Bishop K, Merinbaum P, Emeribe U, Agbo F, et al. (2009)

Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of anastrozole in prepubertal

boys with recent-onset gynecomastia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94: 29752978.

42. Wit JM, Hero M, Nunez SB (2011) Aromatase inhibitors in Pediatrics . Nat

Rev Endocrinol 8: 135-147.

43. Braustein GD (1999) Aromatase and gynecomastia. Endocr Relat Cancer 6:

315-324.

44. Fruhstorfer BH, Malata CM (2003) A systematic approach to the surgical

treatment of gynecomastia. Br J Plast Surg 56: 237-246.

45. Brown RH, Chang DK, Siy R, Friedman J (2015) Trends in surgical correction

of gynecomastia. Semin Plast Surg 29: 122-130.

46. Handschin AE, Biertry D, Husler R, Banic A, Constaninescu M (2008) Surgical

Management of gynecomastia: a 10 years analysis. World J Surg 32: 38-44.

47. Kasielska A, Antoszewski B (2013) Surgical management of gynecomastia:

an outcomeanalysis. Ann Plast Surg 71: 471-475.

Copyright: 2016 Al Jurayyan NA. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation: Al Jurayyan NA (2016) Childhood Gynecomastia: A Mini Review. Int J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2(1): 012-015.

015

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Clinical Guide to Diagnosing and Treating GynecomastiaDokumen5 halamanA Clinical Guide to Diagnosing and Treating GynecomastiaIbrahim AbdiBelum ada peringkat

- Indirani College of Nursing: Level of Student - B.SC (N) Ii YrsDokumen15 halamanIndirani College of Nursing: Level of Student - B.SC (N) Ii YrsdhanasundariBelum ada peringkat

- Gynecomastia: Submitted byDokumen7 halamanGynecomastia: Submitted byKailash KhatriBelum ada peringkat

- Gynecomastia: Practice EssentialsDokumen9 halamanGynecomastia: Practice EssentialsWahdatBelum ada peringkat

- Gynecomastia in Children and Adolescents - UpToDateDokumen42 halamanGynecomastia in Children and Adolescents - UpToDateMarcos RamosBelum ada peringkat

- Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 2004 Bembo 511 7Dokumen7 halamanCleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 2004 Bembo 511 7DewinsBelum ada peringkat

- Womens HealthDokumen12 halamanWomens HealthPooja ChoudharyBelum ada peringkat

- Abnormal Uterine Bleeding GuideDokumen11 halamanAbnormal Uterine Bleeding GuideKharmell Waters AndradeBelum ada peringkat

- The Ultimate Weapon Against Alpha Chest Catastrophe: SurgeryDokumen18 halamanThe Ultimate Weapon Against Alpha Chest Catastrophe: SurgeryAdamBelum ada peringkat

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome 2016 NEJMDokumen11 halamanPolycystic Ovary Syndrome 2016 NEJMGabrielaBelum ada peringkat

- Polycystic Ovary SyndromeDokumen11 halamanPolycystic Ovary SyndromeViridiana Briseño GarcíaBelum ada peringkat

- Insight Into The Pathogensis of Polycystic OvarianDokumen10 halamanInsight Into The Pathogensis of Polycystic OvarianHAVIZ YUADBelum ada peringkat

- Acog 194Dokumen15 halamanAcog 194Marco DiestraBelum ada peringkat

- Ovario Poliquístico/Polycystic Ovary SyndromeDokumen14 halamanOvario Poliquístico/Polycystic Ovary SyndromeJosé María Lauricella100% (1)

- Jama Huddleston 2022 It 210031 1641843898.23442Dokumen2 halamanJama Huddleston 2022 It 210031 1641843898.23442Davi LeocadioBelum ada peringkat

- Sind Ovario Poliquistico 2016 - NejmDokumen11 halamanSind Ovario Poliquistico 2016 - NejmAntonio MoncadaBelum ada peringkat

- Narula2014 Gynécomastie - Physiopathologie, Diagnostic Et TraitementDokumen15 halamanNarula2014 Gynécomastie - Physiopathologie, Diagnostic Et TraitementIbrahimBelum ada peringkat

- AACE/ACE Disease State Clinical ReviewDokumen10 halamanAACE/ACE Disease State Clinical ReviewSanjay NavaleBelum ada peringkat

- Infertility: SymptomsDokumen9 halamanInfertility: SymptomsVyshak KrishnanBelum ada peringkat

- Pcos - Clinical Case DiscussionDokumen4 halamanPcos - Clinical Case Discussionreham macadatoBelum ada peringkat

- Use of Ethinylestradiol/drospirenone Combination in Patients With The Polycystic Ovary SyndromeDokumen6 halamanUse of Ethinylestradiol/drospirenone Combination in Patients With The Polycystic Ovary SyndromeMonalisa SatpathyBelum ada peringkat

- Teede 2010 PDFDokumen10 halamanTeede 2010 PDFKe XuBelum ada peringkat

- Diagnostic Evaluation of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Adolescents - UpToDateDokumen31 halamanDiagnostic Evaluation of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Adolescents - UpToDateRICO NOVYANTOBelum ada peringkat

- Uterine Fibroids Natural Treatment by CurcuminDokumen6 halamanUterine Fibroids Natural Treatment by CurcuminRay CrashBelum ada peringkat

- Karimzadeh 2010Dokumen5 halamanKarimzadeh 2010Derevie Hendryan MoulinaBelum ada peringkat

- Options For Medical Treatment of Myomas: Beth W. Rackow, MD, Aydin Arici, MDTDokumen14 halamanOptions For Medical Treatment of Myomas: Beth W. Rackow, MD, Aydin Arici, MDTDimas YudhistiraBelum ada peringkat

- MEN1 PPDokumen15 halamanMEN1 PPAaron D. PhoenixBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation and Management of Primary Amenorrhea - UpToDateDokumen14 halamanEvaluation and Management of Primary Amenorrhea - UpToDateCristinaCaprosBelum ada peringkat

- pcosDokumen9 halamanpcosMonomay HalderBelum ada peringkat

- Amenorrhea - An Approach To Diagnosis and Management AFP 2013 PDFDokumen8 halamanAmenorrhea - An Approach To Diagnosis and Management AFP 2013 PDFBabila CarvalhoBelum ada peringkat

- Esmaeilinezhad Et Al 2019Dokumen8 halamanEsmaeilinezhad Et Al 2019ahmad azhar marzuqiBelum ada peringkat

- Gynaecomastia: BMJ Clinical Research September 2016Dokumen10 halamanGynaecomastia: BMJ Clinical Research September 2016kintan utamiBelum ada peringkat

- Uterine Bleeding-A Case StudyDokumen4 halamanUterine Bleeding-A Case StudyRoanne Lagua0% (1)

- CA2018PPt NewDokumen32 halamanCA2018PPt NewAshlene Kate BagsiyaoBelum ada peringkat

- New in JPNDokumen7 halamanNew in JPNHar YudhaBelum ada peringkat

- Leiomyoma Guide: Symptoms, Causes & Treatment OptionsDokumen40 halamanLeiomyoma Guide: Symptoms, Causes & Treatment OptionsgaasheBelum ada peringkat

- Acta 90 405Dokumen6 halamanActa 90 405Eftychia GkikaBelum ada peringkat

- Gynecomastia: Clinical PracticeDokumen9 halamanGynecomastia: Clinical PracticeDewinsBelum ada peringkat

- Guideline On Induction of Ovulation 2011Dokumen20 halamanGuideline On Induction of Ovulation 2011Atik ShaikhBelum ada peringkat

- Induction and Maintenance of Amenorrhea in Transmasculine and Nonbinary AdolescentsDokumen6 halamanInduction and Maintenance of Amenorrhea in Transmasculine and Nonbinary AdolescentsdespalitaBelum ada peringkat

- Polycystic Ovarian SyndromeDokumen17 halamanPolycystic Ovarian SyndromeAhmed ElmohandesBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation and Management of Primary Amenorrhea - UpToDateDokumen11 halamanEvaluation and Management of Primary Amenorrhea - UpToDateNatasya SugiantoBelum ada peringkat

- Anovulatory InfertilityDokumen57 halamanAnovulatory InfertilityUsha AnengaBelum ada peringkat

- Prevalence and Risk Factor of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: Review ArticleDokumen3 halamanPrevalence and Risk Factor of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: Review Articleankit kumarBelum ada peringkat

- Eng Kesper CBLDokumen3 halamanEng Kesper CBLExo LBelum ada peringkat

- NCM 116 Endocrine DisordersDokumen106 halamanNCM 116 Endocrine DisordersAnthony Seth AguilandoBelum ada peringkat

- H Amruth Et AlDokumen6 halamanH Amruth Et AlInternational Journal of Clinical and Biomedical Research (IJCBR)Belum ada peringkat

- Endometrial Thickness Predicts Hyperplasia in PCOS PatientsDokumen28 halamanEndometrial Thickness Predicts Hyperplasia in PCOS PatientsPirthi MannBelum ada peringkat

- 3 - Pcos Tog 2017Dokumen11 halaman3 - Pcos Tog 2017Siti NurfathiniBelum ada peringkat

- Case Report: Pregnancy in An Infertile Woman With Polycystic Ovary SyndromeDokumen4 halamanCase Report: Pregnancy in An Infertile Woman With Polycystic Ovary SyndromeEunice PalloganBelum ada peringkat

- Kri Edt 2018Dokumen5 halamanKri Edt 2018Teguh Imana NugrahaBelum ada peringkat

- Appendix - Drug Use During PregnancyDokumen6 halamanAppendix - Drug Use During PregnancySankar KuttiBelum ada peringkat

- Sign of Hyperandrogenism PDFDokumen6 halamanSign of Hyperandrogenism PDFmisbah_mdBelum ada peringkat

- Polycystic Ovarian SyndromeDokumen19 halamanPolycystic Ovarian SyndromeAndreeaBiancaPuiuBelum ada peringkat

- Polycystic OvaryDokumen25 halamanPolycystic OvaryAli AbdElnaby SalimBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation and Management of Primary AmenorrheaDokumen11 halamanEvaluation and Management of Primary AmenorrheaLisa LestariBelum ada peringkat

- Bpj12 Polycystic Pages 7-13Dokumen0 halamanBpj12 Polycystic Pages 7-13Kimsha ConcepcionBelum ada peringkat

- Endometrial Cancer: A Comprehensive Resource for Patients and FamiliesDari EverandEndometrial Cancer: A Comprehensive Resource for Patients and FamiliesBelum ada peringkat

- Fixing Man Boobs Guide: How to Get Rid of GynecomastiaDari EverandFixing Man Boobs Guide: How to Get Rid of GynecomastiaBelum ada peringkat

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 9: GynecologyDari EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 9: GynecologyBelum ada peringkat

- Study On Improvement of Manpower Performance & Safety in Construction FirmsDokumen5 halamanStudy On Improvement of Manpower Performance & Safety in Construction FirmsPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- Should National Environmental Policy Focus On Developing More Oil Resources or Developing Renewable Energy Sources?Dokumen3 halamanShould National Environmental Policy Focus On Developing More Oil Resources or Developing Renewable Energy Sources?Peertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- A Survey of Solid Waste Management in Chennai (A Case Study of Around Koyambedu Market and Madhavaram Poultry Farms)Dokumen4 halamanA Survey of Solid Waste Management in Chennai (A Case Study of Around Koyambedu Market and Madhavaram Poultry Farms)Peertechz Publications Inc.100% (1)

- Is It Time For The Introduction of Colostomy Free Survival in Rectal Cancer PatientsDokumen4 halamanIs It Time For The Introduction of Colostomy Free Survival in Rectal Cancer PatientsPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- Abrikossoff's Tumour Mimicking A Neoplastic Tumour of The Breast: A Case ReportDokumen3 halamanAbrikossoff's Tumour Mimicking A Neoplastic Tumour of The Breast: A Case ReportPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- Comparative Analysis of Collapse Loads of Slabs Supported On Orthogonal Sided Frames With Beam/column Joint FixedDokumen7 halamanComparative Analysis of Collapse Loads of Slabs Supported On Orthogonal Sided Frames With Beam/column Joint FixedPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- A Perceptive Journey Through PostmodernismDokumen4 halamanA Perceptive Journey Through PostmodernismPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- Primary Spindle Cell Rhabdomyosarcoma of Prostate: A Case Report With Review of LiteratureDokumen3 halamanPrimary Spindle Cell Rhabdomyosarcoma of Prostate: A Case Report With Review of LiteraturePeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- User Response - Based Sustainable Solutions To Traffic Congestion Problem Using Public Transport: The Case of Uttara, DhakaDokumen7 halamanUser Response - Based Sustainable Solutions To Traffic Congestion Problem Using Public Transport: The Case of Uttara, DhakaPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- COMAMMOX - A New Pathway in The Nitrogen Cycle in Wastewater Treatment PlantsDokumen3 halamanCOMAMMOX - A New Pathway in The Nitrogen Cycle in Wastewater Treatment PlantsPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- Modulation of Immune Response in Edible Fish Against Aeromonas HydrophilaDokumen5 halamanModulation of Immune Response in Edible Fish Against Aeromonas HydrophilaPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- Diagnosing HPV-Related Oropharyngeal Cancers: The Need To Speak A Common LanguageDokumen4 halamanDiagnosing HPV-Related Oropharyngeal Cancers: The Need To Speak A Common LanguagePeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- Body Mass Index Impact and Predictability On Preeclamptic ToxemiaDokumen6 halamanBody Mass Index Impact and Predictability On Preeclamptic ToxemiaPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- Angiosarcoma of The Scalp and Face: A Hard To Treat TumorDokumen4 halamanAngiosarcoma of The Scalp and Face: A Hard To Treat TumorPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- The Role of Decavanadate in Anti - Tumour ActivityDokumen3 halamanThe Role of Decavanadate in Anti - Tumour ActivityPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- Echinocandins and Continuous Renal Replacement Therapies: The Role of AdsorptionDokumen3 halamanEchinocandins and Continuous Renal Replacement Therapies: The Role of AdsorptionPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- The Promise of Disease Management in GreeceDokumen8 halamanThe Promise of Disease Management in GreecePeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- MEK Inhibitors in Combination With Immune Checkpoint Inhibition: Should We Be Chasing Colorectal Cancer or The KRAS Mutant CancerDokumen2 halamanMEK Inhibitors in Combination With Immune Checkpoint Inhibition: Should We Be Chasing Colorectal Cancer or The KRAS Mutant CancerPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- The Outcomes of Postoperative Total Hip Arthroplasty Following Western Ontario McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) : A Prospective StudyDokumen6 halamanThe Outcomes of Postoperative Total Hip Arthroplasty Following Western Ontario McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) : A Prospective StudyPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- Video Endoscopic Inguinal Lymphadenectomy: Refi Ning Surgical Technique After Ten Years ExperienceDokumen4 halamanVideo Endoscopic Inguinal Lymphadenectomy: Refi Ning Surgical Technique After Ten Years ExperiencePeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- Bacterial Vaginosis: Risk of Adverse Pregnancy OutcomeDokumen3 halamanBacterial Vaginosis: Risk of Adverse Pregnancy OutcomePeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- Role of Tumor Heterogeneity in Drug ResistanceDokumen2 halamanRole of Tumor Heterogeneity in Drug ResistancePeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- PLGF, sFlt-1 and sFlt-1/PlGF Ratio: Promising Markers For Predicting Pre-EclampsiaDokumen6 halamanPLGF, sFlt-1 and sFlt-1/PlGF Ratio: Promising Markers For Predicting Pre-EclampsiaPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- Steroid Withdrawal Protocols in Renal TransplantationDokumen8 halamanSteroid Withdrawal Protocols in Renal TransplantationPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- Evaluating Mechanical Ventilation in Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress SyndromeDokumen5 halamanEvaluating Mechanical Ventilation in Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress SyndromePeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- An Overview: Laboratory Safety and Work Practices in Infectious Disease ResearchDokumen6 halamanAn Overview: Laboratory Safety and Work Practices in Infectious Disease ResearchPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- The Outcomes of Postoperative Total Hip Arthroplasty Following Western Ontario McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) : A Prospective StudyDokumen6 halamanThe Outcomes of Postoperative Total Hip Arthroplasty Following Western Ontario McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) : A Prospective StudyPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- Exercise-Induced Time-Dependent Changes in Plasma BDNF Levels in People With SchizophreniaDokumen6 halamanExercise-Induced Time-Dependent Changes in Plasma BDNF Levels in People With SchizophreniaPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- An Overview: Laboratory Safety and Work Practices in Infectious Disease ResearchDokumen6 halamanAn Overview: Laboratory Safety and Work Practices in Infectious Disease ResearchPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- Exercise-Induced Time-Dependent Changes in Plasma BDNF Levels in People With SchizophreniaDokumen6 halamanExercise-Induced Time-Dependent Changes in Plasma BDNF Levels in People With SchizophreniaPeertechz Publications Inc.Belum ada peringkat

- True / False QuestionsDokumen23 halamanTrue / False QuestionsShawnetz CoppBelum ada peringkat

- MedSurg D2 by Prof Ferdinand B. ValdezDokumen2 halamanMedSurg D2 by Prof Ferdinand B. ValdezJhonny pingolBelum ada peringkat

- Endocrine System Lesson Explains Glands and HormonesDokumen4 halamanEndocrine System Lesson Explains Glands and HormonesFaye AmbasingBelum ada peringkat

- The Emerging Pillars of Chronic Kidney Disease No Longer A Bystander in Metabolic MedicinDokumen5 halamanThe Emerging Pillars of Chronic Kidney Disease No Longer A Bystander in Metabolic MedicinAlfredo CruzBelum ada peringkat

- AntaraDokumen13 halamanAntaraDeepti KukretiBelum ada peringkat

- High Levels of Free TestosteroneDokumen2 halamanHigh Levels of Free TestosteroneADBelum ada peringkat

- l8 Cc2 Lab Hypothalamus and Pituitary Gland Wala Nahuman PoDokumen15 halamanl8 Cc2 Lab Hypothalamus and Pituitary Gland Wala Nahuman PoAlyanaBelum ada peringkat

- Assignment - Manuscript Review - 09012020Dokumen5 halamanAssignment - Manuscript Review - 09012020Nitya KrishnaBelum ada peringkat

- B. 10 Situation - Care of Client With Problems in Metabolism & Endocrine Functioning.Dokumen7 halamanB. 10 Situation - Care of Client With Problems in Metabolism & Endocrine Functioning.SOLEIL LOUISE LACSON MARBAS100% (1)

- 2018 Sec 4 Science Biology SA2 - KranjiDokumen35 halaman2018 Sec 4 Science Biology SA2 - Kranji19Y1H GAO CHENZHANGBelum ada peringkat

- Non Skilled OSPE - EndocrineDokumen8 halamanNon Skilled OSPE - EndocrineUltra Gamer promaxBelum ada peringkat

- Yale Insulin Infusion ProtocolDokumen2 halamanYale Insulin Infusion ProtocolIffatNaeemBelum ada peringkat

- A Case Discussion of Management of Primary Infertility Due To EndometriosisDokumen35 halamanA Case Discussion of Management of Primary Infertility Due To EndometriosisVarsha GaikwadBelum ada peringkat

- Human Physiology From Cells To Systems Sherwood 9th Edition Test BankDokumen15 halamanHuman Physiology From Cells To Systems Sherwood 9th Edition Test Bankandrewmccoymrpazkcnwi100% (47)

- Cardiovascular System Documents Covering Anatomy, Pathophysiology, Pharmacology & MoreDokumen49 halamanCardiovascular System Documents Covering Anatomy, Pathophysiology, Pharmacology & MoreDinesh Kumar ReddyBelum ada peringkat

- Vasopressin deficiency causes polyuria and polydipsia in womanDokumen67 halamanVasopressin deficiency causes polyuria and polydipsia in womanRaquel BencosmeBelum ada peringkat

- Emulsification LipidsDokumen23 halamanEmulsification LipidsChard RIBelum ada peringkat

- ARES Protocol Os UseDokumen5 halamanARES Protocol Os UseLeia AlbaBelum ada peringkat

- Diabetes or High Blood Sugar - Classifications of Diabetes, Symptoms, Effects, Diabetes Treatment, Type 1 and Type 2 DiabetesDokumen3 halamanDiabetes or High Blood Sugar - Classifications of Diabetes, Symptoms, Effects, Diabetes Treatment, Type 1 and Type 2 DiabetesChandu SubbuBelum ada peringkat

- Uncontrolled Blood Sugar NCPDokumen4 halamanUncontrolled Blood Sugar NCPRawan KhateebBelum ada peringkat

- Menopause Hormone Replacement TherapyDokumen4 halamanMenopause Hormone Replacement Therapybidan22Belum ada peringkat

- Asynchronous Activity Sheet FormsDokumen8 halamanAsynchronous Activity Sheet FormsNur SanaaniBelum ada peringkat

- Drug Levothyroxine SodiumDokumen2 halamanDrug Levothyroxine SodiumSrkocher0% (1)

- Endocrine System GlandsDokumen40 halamanEndocrine System GlandsSolita PorteriaBelum ada peringkat

- DiabetiesDokumen11 halamanDiabetiesAnil ChityalBelum ada peringkat

- Obat antithiroid: New England Medical Journal review of antithyroid drugsDokumen52 halamanObat antithiroid: New England Medical Journal review of antithyroid drugsYeyen MusainiBelum ada peringkat

- Biology Form 5 Reproduction & GrowthDokumen3 halamanBiology Form 5 Reproduction & GrowthM I K R A MBelum ada peringkat

- Bestellfax Elecsys e 411 601 E170Dokumen9 halamanBestellfax Elecsys e 411 601 E170Jurica ErcegBelum ada peringkat

- Lyphochek Immunoassay Plus Control Levels 1, 2 and 3: Fecha de Revisión 2021-04-20 Indica Información RevisadaDokumen25 halamanLyphochek Immunoassay Plus Control Levels 1, 2 and 3: Fecha de Revisión 2021-04-20 Indica Información RevisadaMariam MangaBelum ada peringkat

- Diabetes FlowchartDokumen1 halamanDiabetes Flowcharthhos619Belum ada peringkat