La Cosa Nostra in The United States

Diunggah oleh

vfrpilotJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

La Cosa Nostra in The United States

Diunggah oleh

vfrpilotHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

NIJ - International Center - U.

N Activities - La Cosa Nostra in the US

Participating in the U.N.'s crime prevention program.

LA COSA NOSTRA IN THE UNITED STATES

by

James O. Finckenauer, Ph.D.

International Center

National Institute of Justice

Organizational Structure

La Cosa Nostra or LCN -- also known as the Mafia, the mob, the outfit, the office -- is a collection of ItalianAmerican organized crime families that has been operating in the United States since the 1920s. For

nearly three quarters of a century, beginning during the time of Prohibition and extending into the 1990s, the

LCN was clearly the most prominent criminal organization in the U.S. Indeed, it was synonymous with

organized crime. In recent years, the LCN has been severely crippled by law enforcement, and over the past

decade has been challenged in a number of its criminal markets by other organized crime groups.

Nevertheless, with respect to those criteria that best define the harm capacity of criminal organizations, it is

still pre-eminent. The LCN has greater capacity to gain monopoly control over criminal markets, to use or

threaten violence to maintain that control, and to corrupt law enforcement and the political system than does

any of its competitors. As one eminent scholar has also pointed out, no other criminal organization [in the

United States] has controlled labor unions, organized employer cartels, operated as a rationalizing force in

major industries, and functioned as a bridge between the upperworld and the underworld (Jacobs,

1999:128). It is this capacity that distinguishes the LCN from all other criminal organizations in the U.S.

Each of the so-called families that make up the LCN has roughly the same organizational structure. There is

a boss who controls the family and makes executive decisions. There is an underboss who is second in

command. There is a senior advisor or consigliere. And then there are a number of capos (capo-regimes)

who supervise crews made up of soldiers, who are made members of Cosa Nostra. The capos and those

above them receive shares of the proceeds from crimes committed by the soldiers and associates.

Made members, sometimes called good fellows or wise guys, are all male and all of Italian descent. The

estimated made membership of the LCN is 1100 nationwide, with roughly eighty percent of the members

operating in the New York metropolitan area. There are five crime families that make up the LCN in New

York City: the Bonanno, the Colombo, the Genovese, the Gambino, and the Lucchese families. There is also

LCN operational activity in Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, and the Miami\South Florida area, but much less

so than in New York. In other previous strongholds such as Cleveland, Detroit, Kansas City, Las Vegas, Los

Angeles, New Orleans, and Pittsburgh, the LCN is now weak or non-existent. In addition to the made

members, there are approximately 10,000 associate members who work for the families. Until the recent

demise of much of its leadership, there was a Commission of the bosses of New Yorks five LCN families

that coordinated control of labor unions, construction, trucking and garbage hauling companies, and that

resolved disputes between families.

La Cosa Nostra does not enjoy general social acceptance and support. With the exception of a few ethnic

Italian neighborhoods where certain of the more brazen exploits and some of the community good deeds of

bosses are admired, Italian organized crime reinforces a stigma that most Italian-Americans want to get rid

of. Along with the effectiveness of law enforcement, the absence of support for the LCN means that

recruitment has become difficult. Some families have disappeared, and others are only 50 percent to as little

as 10 percent of their size 30 years ago. At the same time however, as with all organized crime, it is the

communitys desire for illicit goods and services that continues to help fuel the survival of the LCN.

Becoming a made member of LCN requires serving an apprenticeship and then being proposed by a Boss.

This is followed by gaining approval for membership from all the other families. Once approved, there is a

secret, ritualized induction ceremony. Made membership means both honor and increased income. It also,

however, entails responsibilities -- in particular taking an oath of omerta. Omerta demands silence to the

outside world about the criminal affairs of the family, never betraying anyone in the family, and never

file:///E|/Documents%20and%20Settings/kpurcell/My%2...vities%20-%20La%20Cosa%20Nostra%20in%20the%20US.htm (1 of 4)12/6/2007 4:30:43 PM

NIJ - International Center - U.N Activities - La Cosa Nostra in the US

revealing to law enforcement anything that might incriminate anyone in organized crime. The penalty for

violating this oath is death. Any wise guy who takes a plea without authorization by the family runs the risk of

the death penalty. That death is indeed used to enforce internal discipline is evidenced by the execution in

1998 of a capo in the Genovese crime family for pocketing money that should have been passed on to his

superiors. An underworld source said about this missing capo: The people theyre looking to send a

message to is not the general public. Its the mob itself, which totally understands that the guy is gone. At

the same time, the fact that there are over a hundred members in the Federal witness protection program

suggests that omerta is not nearly as effective as it once was.

Violence

La Cosa Nostra, over many years, established its reputation for the ruthless use of violence. This violence

has occurred mostly in the form of beatings and killings. Personal violence, and to a lesser degree violence

against property, e.g., bombings, arson, explosions, is the typical pattern of the systematic use of violence

as a tool of doing business. Violence, and subsequently just the threat of violence, was the means by which

the LCN gained monopoly control over its various criminal enterprises. It discouraged and eliminated

competitors, and it reinforced the reputation and credibility of the LCN. Violence was and is also used for

internal discipline. Law enforcement experts indicate that the threat of violence is at the core of LCN

activities. Murder, or conspiracy to commit murder, has often appeared as one of the predicate offenses in

RICO (Racketeer-Influenced and Corrupt Organizations) prosecutions.

That violence continues to be an LCN tool is evidenced in several cases within the past three years. The first

two incidents were carried out at the behest of the former head of the Gambino crime family in New York,

John Gotti. In a 1997 trial, a member of the Gambino family testified about a torture killing that had been

ordered by Gotti. The victim had apparently fired a shot at Gotti. He was tortured with lighted cigarettes and

a knife, shot in the buttocks,carried in the trunk of a car, and ultimately killed with five shots to the head. In

the second example, the same John Gotti, from his federal prison cell, contracted with two members of the

white supremacist group the Aryan Brotherhood to kill the former consigliere of the Gambino crime family

who had threatened to kill him.

In a 1997 case that demonstrates the approach of the LCN with respect to the use of violence for retribution

and intimidation, there was an LCN plot (not acted upon) to assassinate the federal judge who had presided

over some of New York Citys biggest mob trials. Finally, in 1999, a member of the Lucchese crime family

(also based in New York) and others were charged with conducting a 15-year reign of terror against

competitors in the private sanitation business. The charges included setting fire to trucks and buildings of

rival carters, damaging businesses that dared to hire carters outside the LCN cartel, and killing a salesman

for a rival carting company.

The history of violence and the LCN demonstrates the importance of reputation in this respect. Jacobs and

Gouldin (1999) cite criminologist Peter Reuters point that when there is sufficient credible evidence of the

willingness to use violence, actually violence is rarely necessary. This is especially true when the targets are

not professional criminals. La Cosa Nostra personifies this principle.

Economic Resources

Jacobs (1999) believes that one of the LCNs major assets is its general business acumen. They are best

described, he says, as being entrepreneurial, opportunistic, and adaptable. They find ways to exploit market

vulnerabilities, while at the same time maintaining the necessary stability and predictability that business

requires to be profitable. One of the ways they do this is by taking over only a piece of a legitimate business

-- and providing a service in return -- rather than taking over the whole business. The latter would, of course,

require a management responsibility that they do not want and possibly could not handle, and that would in

addition likely upset the business climate necessary for success.

La Cosa Nostras illegal activities cover a wide range. Gambling and drugs have traditionally been their

biggest money makers. Loan sharking is often linked with the gambling and drugs, and is an area that

exemplifies the role played by the credible use of violence. The same is true of extortion. The other more

traditional crimes also include hijacking, air cargo theft, and of course murder.

Then there a set of crimes that have become specialties of the LCN, and are unique to them in the United

States. Although some of these criminal activities have had national effects, they have been carried out

almost exclusively by the five crime families in New York City since LCN penetration of the legitimate

economy elsewhere in the U.S. is minimal. The specialties of the New York families include labor

racketeering, various kinds of business racketeering, bid-rigging, business frauds, and industry cartels. It is

in these areas that the LCN demonstrates its most aggressive and effective penetration of the legitimate

economy. Labor racketeering involves organized crime control of labor unions. With this control, gained by

file:///E|/Documents%20and%20Settings/kpurcell/My%2...vities%20-%20La%20Cosa%20Nostra%20in%20the%20US.htm (2 of 4)12/6/2007 4:30:43 PM

NIJ - International Center - U.N Activities - La Cosa Nostra in the US

the threat and use of violence, vast sums of money are siphoned from union pension funds, businesses are

extorted in return for labor peace and an absence of strikes, and bribes are solicited for sweetheart

contracts. Another speciality, business racketeering, has occurred in New York City in the construction,

music, and garbage industries. The LCN controls unions, bars, strip joints, restaurants, and trucking firms.

The five families have also controlled at various times the Fulton Fish Market, the Javits Convention Center,

the New York Coliseum, and air cargo operations at JFK International Airport, among other targets. Again

the principal tools of control are extortion and the use of violence.

One of the best examples of an LCN cartel was their monopoly of the waste hauling industry in New York

City for almost 50 years. La Cosa Nostra used its control of local unions to set up a cartel (Jacobs & Hortis,

1998). The cartel monopolized the industry by threatening business disruption, labor problems, and personal

violence. As a result of its monopoly control, the LCN forced participants and consumers to pay inflated

prices for waste hauling -- a practice known as a mob tax. Over the years this mob tax cost the industry

hundreds of millions of dollars.

In part in reaction to effective law enforcement actions in many of the areas mentioned above, La Cosa

Nostra has diversified its activities and extended its penetration in legal markets by switching to white-collar

crimes in recent years (Raab, 1997). They have carried out multimillion dollar frauds in three areas in

particular: health insurance, prepaid telephone cards, and through victimizing small Wall Street brokerage

houses. Professional know-how is demonstrated in each of these scams. In an example of their health

insurance frauds, mobsters set up Tri-Con Associates, a New Jersey company that arranged medical, dental

and optical care for more than one million patients throughout the country. They used non-mob employees

of Tri-Con as managers, and intimidated health insurance administrators into approving excessive payments

to the company. With the prepaid telephone cards, the Gambino family set up a calling card company that

stole more than $50 million from callers and phone companies by means of fraudulent sales. In the case of

the stock market, LCN members and associates offer loans to stockbrokers who are in debt or need capital

to expand their businesses. The mobsters then force the brokers to sell them most of the low-priced shares

in a company before its stock is available to investors through initial public offerings. They then quickly

inflate the value of the shares and sell out with huge profits before the overvalued stocks plunge.

La Cosa Nostras monopoly control over various illegal markets, and its diversification into legal markets,

has so far not been matched by any other criminal organization in the United States. This is so despite its

having been substantially weakened over the last decade.

Political Resources

As has already been indicated, La Cosa Nostra is today much less powerful and pervasive than it was in the

past. A loss of political influence has accompanied its general decline. In its heyday, the LCN exercised its

political influence mostly at the local level, through its connections with the political machines that operated

in certain U.S. cities such as New York, New Orleans, Chicago, Kansas City, and Philadelphia. With the

demise of those machines, and with the advent of political reforms stressing open and ethical government,

many of the avenues for corrupt influence were substantially closed. Today, the LCN exercises political

influence in certain selected areas and with respect to certain selected issues. For example, it has attempted

to influence the passage of legislation regulating legalized gambling in states such as Louisiana.

With respect to police and judicial corruption, again there is much more evidence of this in the past than

there is today. In the past three years, there have been a handful of corruption cases involving law

enforcement and one or two involving judges that are linked to La Cosa Nostra families. In Chicago, for

example, a federal investigation of corruption in the courts (and city government more generally), led to 26

individuals -- including judges, politicians, police officers, and lawyers -- pleading guilty or being convicted at

trial in 1997.

In one of the most notorious cases in recent years, in Boston a former FBI supervisor admitted (under a

grant of immunity) to accepting $7,000 in payoffs from two FBI mob informants. The two mobsters were

major figures in the New England Cosa Nostra. A second FBI agent was subsequently convicted in the case

in 1999. The two FBI agents were charged with alerting the informants to investigations in which they were

targets, and with protecting them from prosecution.

There has never been any evidence that La Cosa Nostra has had direct representation in the Congress of

the United States, nor in the U.S. executive or diplomatic service. Neither is there any evidence that it has

ever been allied with such armed opposition groups as terrorists, guerrillas, or death squads. In this respect,

the LCN exemplifies one of the traditional defining characteristics of organized crime in that its goal is an

economic rather than a political one. Where there has been political involvement, it has been for the

purposes of furthering economic objectives.

file:///E|/Documents%20and%20Settings/kpurcell/My%2...vities%20-%20La%20Cosa%20Nostra%20in%20the%20US.htm (3 of 4)12/6/2007 4:30:43 PM

NIJ - International Center - U.N Activities - La Cosa Nostra in the US

Responses of Law Enforcement Agencies to Organized Crime

Law enforcement, and particularly federal law enforcement, has been tremendously successful in combating

La Cosa Nostra over the past 10 years. Crime families have been infiltrated by informants and undercover

agents, and special investigating grand juries have been employed in state and local jurisdictions. Especially

effective use has been made of investigative and prosecutorial techniques that were designed specifically for

use against organized crime, and in particular against La Cosa Nostra. These latter techniques include

electronic surveillance, the witness protection program, and the Racketeer-Influenced and Corrupt

Organizations Act (RICO). The RICO statute has clearly been the single most powerful tool against the LCN.

There are now state RICO statutes as well as the federal one. RICO enables law enforcement to attack the

organizational structure of organized crime and to levy severe criminal and civil penalties, including

forfeitures. It is the threat of these penalties that has convinced many made members of the LCN to become

informants and/or to seek immunity from prosecution in return for becoming a cooperating witness. They are

then placed in the witness protection program. Civil remedies have included the court-appointment of

monitors and trustees to administer businesses and unions that had been taken over by the LCN, to insure

that these enterprises remain cleansed of corrupt influences.

Two of the latest weapons against La Cosa Nostra penetration of sectors of the legitimate economy are

regulatory initiatives. As such, they are not law enforcement approaches per se, but rather administrative

remedies designed to expand a local governments ability to control public services such as waste hauling

and school construction. The first instance involves the creation of a regulatory commission. New York City,

for example, created the Trade Waste Commission (TWC) that ended the LCN cartel in the waste hauling

industry in that city through a process of licensing, investigation, competitive bidding, rate setting, and

monitoring (Jacobs & Hortis, 1998). Other jurisdictions are now following suit.

The second example is the creation of a private inspector general. These inspector generals are hired in

industries that have historically been controlled by organized crime, and in this case the LCN. An example is

the school construction industry in New York City for which a School Construction Authority had already

been created. This SCA then utilized a private inspector general to monitor its contractors, to establish

corruption controls, and to report back to them on contractor conduct. Jacobs calls this one of the great

contemporary innovations in organized-crime control (Jacobs, 1999).

La Cosa Nostra is a high priority for the FBI and for law enforcement in New York City. Elsewhere, however,

it is a low priority, with attention being characterized by experts as hit and miss because of a belief that

things are under control. The FBI pays the most attention to transnational organized crime, with state/local

law enforcement paying very little attention. Because La Cosa Nostra is mainly a domestic operation, there

is little international cooperation in its investigation and prosecution.

REFERENCES

Jacobs, James B. and Alex Hortis, New York City As Organized Crime Fighter, New York Law School Law

Review, Volume XLII, Numbers 3 & 4, 1998.

Lauryn P. Gouldin, Cosa Nostra: The Final Chapter? Crime and Justice, Volume 25, Chicago: The University of

Chicago, 1999.

Gotham Unbound, New York: New York University Press, 1999.

Raab, Selwyn, Officials Say Mob Is Shifting Crimes To New Industries, The New York Times, February 10, 1997.

file:///E|/Documents%20and%20Settings/kpurcell/My%2...vities%20-%20La%20Cosa%20Nostra%20in%20the%20US.htm (4 of 4)12/6/2007 4:30:43 PM

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

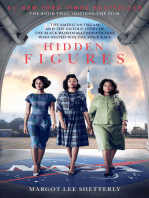

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Reservation of RightsDokumen1 halamanReservation of RightsMike_Huffman_770Belum ada peringkat

- 9 Markers On The US ConstitutionDokumen3 halaman9 Markers On The US ConstitutionLiam HargadonBelum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Rise of Italian FascismDokumen6 halamanRise of Italian FascismDeimante BlikertaiteBelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Estafa, G.R. No. 198932, October 9, 2019 - Set ADokumen2 halamanEstafa, G.R. No. 198932, October 9, 2019 - Set AJan-Nere JapayBelum ada peringkat

- FSI - Italian Familiarization and Short Term Training - Volume 1Dokumen456 halamanFSI - Italian Familiarization and Short Term Training - Volume 1thomasotottidemucho100% (1)

- Eff Ect of Sealing Clearance On Pump PerformanceDokumen4 halamanEff Ect of Sealing Clearance On Pump PerformancevfrpilotBelum ada peringkat

- 423094Dokumen9 halaman423094vfrpilotBelum ada peringkat

- XYZ Ford Escape 2012Dokumen361 halamanXYZ Ford Escape 2012cooljoselo15Belum ada peringkat

- LOCTITE Do It Right Guide v5 ApprovedDokumen44 halamanLOCTITE Do It Right Guide v5 ApprovedvfrpilotBelum ada peringkat

- Usmc Pistol Teamwork BookDokumen158 halamanUsmc Pistol Teamwork Bookvfrpilot100% (1)

- GP Week Issue 224Dokumen37 halamanGP Week Issue 224vfrpilotBelum ada peringkat

- USAS Pistol 2014Dokumen32 halamanUSAS Pistol 2014vfrpilotBelum ada peringkat

- GP Week Issue 223Dokumen37 halamanGP Week Issue 223vfrpilotBelum ada peringkat

- Fixed Income Funds PDFDokumen9 halamanFixed Income Funds PDFvfrpilotBelum ada peringkat

- USAS Shotgun 2014Dokumen68 halamanUSAS Shotgun 2014vfrpilotBelum ada peringkat

- GP0139Dokumen47 halamanGP0139unni1433Belum ada peringkat

- Understanding Vibration Can Help Prevent Pump FailuresDokumen4 halamanUnderstanding Vibration Can Help Prevent Pump FailuresvfrpilotBelum ada peringkat

- Fretting Wear in Lubricated SystemsDokumen7 halamanFretting Wear in Lubricated SystemsvfrpilotBelum ada peringkat

- US Army Pistol Training GuideDokumen94 halamanUS Army Pistol Training Guideelbrujo145Belum ada peringkat

- 2008-2010 National Standard Three-Position Air Rifle RulesDokumen64 halaman2008-2010 National Standard Three-Position Air Rifle RulesvfrpilotBelum ada peringkat

- DOPT Online RTI ApplicationDokumen2 halamanDOPT Online RTI ApplicationShri Gopal SoniBelum ada peringkat

- Constitutional Law Case Digest Matrix Set 6Dokumen6 halamanConstitutional Law Case Digest Matrix Set 6Stef MacapagalBelum ada peringkat

- Bail-439 CRPCDokumen6 halamanBail-439 CRPCRanjitha0% (1)

- Jacek Kaminski, A044 014 301 (BIA May 11, 2017)Dokumen11 halamanJacek Kaminski, A044 014 301 (BIA May 11, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCBelum ada peringkat

- Perfecto vs. EsideraDokumen2 halamanPerfecto vs. EsideraRaymond Diaz100% (1)

- Procedure For Impeachment of President in IndiaDokumen2 halamanProcedure For Impeachment of President in IndiatinkuBelum ada peringkat

- Confirmed ICC Charges Against LRA's OngwenDokumen104 halamanConfirmed ICC Charges Against LRA's OngwenjadwongscribdBelum ada peringkat

- Socorro vs. Van Wilsen G.R. No. 193707Dokumen7 halamanSocorro vs. Van Wilsen G.R. No. 193707vj hernandezBelum ada peringkat

- ANSWERDokumen5 halamanANSWERVj TopacioBelum ada peringkat

- DiMatteo v. Astrazeneca Pharmaceuticals, L.P. Et Al - Document No. 3Dokumen11 halamanDiMatteo v. Astrazeneca Pharmaceuticals, L.P. Et Al - Document No. 3Justia.comBelum ada peringkat

- Forensic PsychiatryDokumen43 halamanForensic PsychiatryJack100% (1)

- Reviewed KYU Examination Regulations of 2013.Dokumen19 halamanReviewed KYU Examination Regulations of 2013.Ssentongo NazilBelum ada peringkat

- 17 Store Owners File Lawsuit in Operation Candy CrushDokumen21 halaman17 Store Owners File Lawsuit in Operation Candy CrushUSA TODAY Network100% (1)

- Rule 39 DigestDokumen41 halamanRule 39 DigestBasri JayBelum ada peringkat

- The Stratagem - The Stratagem and Other StoriesDokumen9 halamanThe Stratagem - The Stratagem and Other StoriesManuel CirauquiBelum ada peringkat

- Complaint Gloria OngDokumen3 halamanComplaint Gloria OngPitongDeAsisBelum ada peringkat

- Harding v. Commercial UnionDokumen1 halamanHarding v. Commercial UnionJoel MilanBelum ada peringkat

- EVIDENCE 2010 Parental Filial Privilege (Lee V Court of Appeals, Et Al.)Dokumen7 halamanEVIDENCE 2010 Parental Filial Privilege (Lee V Court of Appeals, Et Al.)Ronaldo Antonio V. CalayanBelum ada peringkat

- Adoption Full CasesDokumen11 halamanAdoption Full CasesAR ReburianoBelum ada peringkat

- SSGT. Pacoy Vs Hon. CajigalDokumen9 halamanSSGT. Pacoy Vs Hon. CajigalJakie CruzBelum ada peringkat

- People V Damaso 212 SCRA 457Dokumen6 halamanPeople V Damaso 212 SCRA 457John Basil ManuelBelum ada peringkat

- 3rd Year Court DiaryDokumen39 halaman3rd Year Court DiaryJasender SinghBelum ada peringkat

- 2 US v. Pablo, 35 Phil 94 (1916)Dokumen2 halaman2 US v. Pablo, 35 Phil 94 (1916)Princess MarieBelum ada peringkat

- Dennis E. Pryba, Barbara A. Pryba, Educational Books, Inc. and Jennifer G. Williams v. United States, 498 U.S. 924 (1990)Dokumen2 halamanDennis E. Pryba, Barbara A. Pryba, Educational Books, Inc. and Jennifer G. Williams v. United States, 498 U.S. 924 (1990)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Consti Law PP V PomarDokumen1 halamanConsti Law PP V PomarRenz FactuarBelum ada peringkat

- Memo On Motion To Suppress and Dismiss PublicDokumen9 halamanMemo On Motion To Suppress and Dismiss PublicTimothy ZerilloBelum ada peringkat

- Legal Research CasesDokumen218 halamanLegal Research CasesCharmilli PotestasBelum ada peringkat