Thomas 1995. Orthodontic Camouflage Versus Orthognathic Surgery in The Treatment of Mandibular Deficiency.

Diunggah oleh

Benjamin NgJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Thomas 1995. Orthodontic Camouflage Versus Orthognathic Surgery in The Treatment of Mandibular Deficiency.

Diunggah oleh

Benjamin NgHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

J Oral Maxillofac Surg

53:579-587, 1995

Orthodontic Camouflage Versus

Orthognathic Surgery in the Treatment of

Mandibular DeficiencY

PAUL M. THOMAS, DMD, MS*

The Class I1 relationship is the most prevalent subclassification of malocclusion.1 Recognizing the limitations of this description, epidemiologists have formulated indices and scales for use in public health studies.

The results of these surveys suggest that 15% to 20%

of the teenage population have an overjet of 6 mm or

greater. Although such studies do not directly address

this issue, it is likely that many of these individuals

have an abnormality in jaw size or position as a contributing factor. ~

Motivations for seeking correction of this imbalance

generally include a mixture of functional and psychosocial concerns, including self-image as influenced

by dental and facial esthetics. It has been suggested

that Class II malocclusion may lead to dental attrition

and periodontal trauma as well as problems with

speech and chewing. Despite conflicting and contradictory evidence, some clinicians still consider Class II

malocclusion a contributing factor in temporomandibular disorders. 3'4 In a psychosocial context, research

has shown that malocclusion affects employability,

interpersonal relationships, and, accordingly, selfimage. 5

of favorable growth and dentoalveolar manipulation

can lead to reasonable results in the appropriate patient. 6

There are two treatment options for postpubertal individuals seeking correction; orthodontic camouflage

and surgical advancement of the mandible in conjunction with orthodontics. Camouflage, or orthodontic

compensation of Class II malocclusion, is one of the

more common treatment strategies used in clinical

practice. The maxillary anterior teeth are retracted and

their counterparts in the lower arch proclined in an

attempt to reduce overjet and establish a Class I canine

relationship. The extraction of teeth, typically first premolars, is necessary in one or both arches to eliminate

crowding and provide room for compensation. Surgical

treatment involves preoperative orthodontics to properly position the teeth in the respective jaw and an

operative procedure to correct mandibular position,

followed by finishing orthodontics for occlusal detailing. The focus of this discussion will be on these two

approaches.

Although there would appear to be ample justification for correcting Class II malocclusions; previous

experience suggests that there are flaws in the process

of selecting treatment options. There is generally little

disagreement when considering patients at the extremes of the classification. Mild Class II problems can

be orthodontically corrected and severe discrepancies

require orthognathic surgery. Problems seem to occur

when the patient falls in a "grey zone" and might be

treated by either option. Needless to say, both orthodontic camouflage and surgery have been used inappropriately in the past. A review of patients seen from

1984 to 1987 in the University of North Carolina Dentofacial Program indicated 20% of those seen had previous orthodontic treatment and were dissatisfied with

the outcome. 7 The majority of these patients had undergone camouflage treatment for Class II malocclusions.

Likewise, mandibular advancements performed to correct moderate overjet have sometimes exposed the individual to greater morbidity, while producing negligible facial change. A primary goal of this article is to

identify factors that influence both the decision-making

Treatment Alternatives

Four options exist for those individuals seeking correction of increased overjet. Patient concerns and clinical findings are key factors in narrowing the choice.

Treatment should not be considered if the outcome is

unlikely to meet patient expectations, or if local factors

such as dental or periodontal health indicate a prosthetic alternative. Growth guidance may be suggested

for the prepubertal patient having a favorable growth

pattern. Although there is mounting evidence that the

skeletal impact is negligible clinically, a combination

* In private practice.

Address correspondence to Dr Thomas: 5501 Fortune's Ridge Dr,

Suite H, Durham, NC 27713-9355.

1995 American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons

0278-2391/95/5305-001553.00/0

579

580

ORTHODONTIC CAMOUFLAGE VS ORTHOGNATHIC SURGERY

process and assessment of outcome. Recognition of

these factors should help with the selection of a treatment option that addresses patient concerns while considering a favorable cost (risk) versus benefit ratio.

Because this discussion and the companion article have

been written in the context of point/counterpoint, emphasis will be placed on the efficacy of orthodontic

camouflage.

The Decision-Making Process

DIAGNOSIS AND PLANNING

The treatment planning process is well-known to

most contemporary clinicians and generally follows a

method suggested by Ackerman and Proffit more than

20 years ago. Using a scheme of Venn diagrams to

expand on the traditional Angle classification, they

identified five major characteristics of malocclusion

that were descriptive in three dimensions. 8 They also

adapted Lawrence Weed's problem-oriented medical

diagnosis for use in an orthodontic context. 9 Following

this method, data collection includes patient interview,

clinical examination, radiographic studies, standardized photographs or slides, and dental models. This

information is analyzed to produce a list of findings

that may be prioritized in the context of patient concerns according to severity. Treatment alternatives,

orthodontic camouflage, and surgery in this case are

developed with consideration for the ability of each to

address patient concerns with maximum efficiency and

minimum morbidity. This process may include treatment simulation using computer imaging and model

surgery or orthodontic setup. Accepting the limitations

of such simulation, it remains the best means available

to explore options and communicate potential outcome

to the patient and family.

REVIEWING THE OPTIONS

A key part of the preliminary decision-making process involves an unbiased explanation of the alternatives and the associated cost and risk versus benefit

with each. Intellectual honesty is paramount during

both the initial encounter and the subsequent discussion of alternatives. Because it is natural for clinicians

to seek solutions in the context of training and experience, care must be taken to avoid inappropriate influence on patient perceptions and attitudes. This may be

especially difficult for the orthodontist presented with

a patient who is initially expecting limited orthodontic

treatment only to discover there is a significant underlying skeletal imbalance. If there is some uncertainty

regarding alternatives at the initial visit, diagnostic records should be suggested and definitive answers deferred. A sensitive, carefully structured, global discus-

sion can be used to introduce concepts without

committing to a course of action.

If surgery has been discussed at the initial visit and

is a viable option, it is ideal to have the surgeon present

for the subsequent treatment explanation or to arrange

for a timely follow-up consultation. Because treatment

strategies are significantly different for each option,

the individual contemplating treatment must be given

enough information to make an informed decision before starting clinical care. When appropriate, outcome

probabilities should be discussed based on the scientific literature and personal experience. Questions such

as "what would you do?" should be answered carefully by restating the advantages, disadvantages, and

probable outcome with the option in question. Treatment simulations are valuable communication adjuncts, but should be used carefully to avoid creating

unrealistic expectations.

FINANCIAL CONCERNS

The cost of care is frequently a concern, and must

be fully discussed before treatment. This is especially

true given the escalating hospital costs and diminishing

insurance coverage for orthognathic surgery. Poor

communication may result in the orthodontist unilaterally preparing a patient for surgery only to learn thirdparty coverage has changed or is nonexistent. Because

the goals of orthodontic preparation for surgery are

generally the opposite of camouflage, this may leave

the individual with an orthodontic result that has exaggerated the malocclusion.

Factors Affecting Outcome

The evaluation of treatment outcome can be elusive,

but is typically done using a combination of subjective

and objective criteria. Although there are objective

analyses to scrutinize functional change as well as the

accuracy and stability of the outcome, the assessment

of facial attractiveness and body image tends to be less

structured. In addition to feedback from the clinicians

involved, other psychosocial factors such as self-perception and peer reaction shape patient's attitudes.

It is not unusual to see diversity of opinion. A clinician may determine the morphologic and functional

result to be excellent, only to have it perceived as less

than satisfactory by the patient. Likewise an individual

may be thrilled with a result considered only fair by

the treating orthodontist and surgeon. Differences in

perception between surgeons, orthodontists, and laypeople have been shown to exist, and further complicate the issue. In a study of facial improvement, Dunlevy et alm found that surgeons tended to favor more

prominent chins and larger anterior-posterior change

when compared with panels composed of the laypeople

and orthodontists. This bias may affect individual pa-

PAUL M. THOMAS

tient evaluation and is likely to be an influence in

research involving outcome assessment.

PSYCHOSOCIAL FACTORS AND ESTHETIC CONCERNS

There is considerable research indicating that dental

and facial esthetic concerns are major motivating factors

for those seeking treatment) H2 The type of treatment

selected (surgery or orthodontic camoflage) is related

more to body image or self-perception than morphometric discrepancy. Bell et al ~3 found that patients who opt

for surgery tend to view themselves as being at the

extremes of the profile classification. Paradoxically, objective analysis could not distinguish between their malocclusion and that of patients selecting orthodontic camouflage. These findings were further supported in a

study of facial attractiveness involving females who

have Class II malocclusions. ~4Those selecting a surgical

option tested as having more indicators of global psychologic stress and problems with self-esteem. As in

Bell's study, conventional cephalometric analyses could

not discriminate between patients opting for surgery

versus those selecting orthodontic camouflage. The bottom line would seem to be that the psychosocial factors

of self-perception and body image are of significance

in selecting a course of treatment.

FUNCTIONAL AND MORPHOMETRIC FACTORS

Although morphometric analysis is a poor indicator

of which patient will select surgery versus orthodontic

camouflage, it does provide useful insight into the likelihood of correction with each option. Previous efforts

at establishing numerical guidelines have been directed

primarily at defining the limits for application of a

given treatment option. For example, the "envelope

of discrepany" described by Proffit and Ackerman 15

graphically illustrates their best estimate of the maximum change possible with growth guidance, orthodontic camouflage, and orthognathic surgery. The description is limited to the sagittal and vertical dimension

changes in incisor position, without concern for other

modifying factors. Although this concept is useful to

describe the extremes, it lacks the detail necessary for

decision-making in borderline patients. Additional recommendations have been made for patients with Class

II malocclusions beyond the adolescent growth spurt.

Based on an evaluation of treatment outcome, Proffit

et a116 suggested that orthodontic correction becomes

unlikely in a situation with the following characteristics: an overjet beyond 10 mm; a facial height greater

than 125 nun; a mandibular body length less than 70

ram; and pogonion being located more than 18 mm

behind a nasion perpendicular.

Given these guidelines, a stereotype of the acceptable orthodontic camouflage patient begins to emerge.

The posterior occlusal discrepancy should not be

58"1

greater than the width of a premolar because overjet

correction is usually achieved through retraction of the

upper anterior teeth after premolar extraction. The odds

of successful treatment are further improved if the molar relationship is less than full Class II. This allows for

the loss of some maxillary posterior anchorage without

jeopardizing incisor retraction. A short facial height

with increased overbite is beneficial. Because molar

extrusion is common during mechanotherapy, the accompanying bite opening is less likely to risk loss

of anterior contact and diminish chin projection from

clockwise rotation (Fig 1).

Nonextraction treatment of the lower arch is generally

desirable, when possible. If there is mild to moderate

crowding, with upright incisors and good periodontal

support, the lower arch can be expanded and the incisors

proclined during leveling and alignment. This further reduces the amount of maxillary incisor retraction needed

to correct the overjet. On the other hand, an accentuated

curve of Spee, skeletal asymmetry with midline deviation, pre-existing incisor proclination, and severe crowding all indicate the need for extraction. This increases the

likelihood of lower incisor retraction, which accordingly

reduces the probability of overjet correction.

Facial esthetic outcome is influenced by the proportional relationships of the nose, lips, and chin, as well

as the chin to neck contour. Lip retraction increases

the dominance of the nose and chin as soft tissue facial

features. It follows that the pretreatment facial proportions must be considered in selecting the appropriate

treatment option. The amount of lip support lost with

incisor retraction is a function of tissue tonus, thickness, lip competence, and incisor torque (Figs 2A-2G).

Given the proper soft tissue relationships, incisor

retraction may have a negligible effect on lip support.

If chin prominence is a concern, advancement genioplasty offers a less costly, less risky, alternative to

enhance facial esthetics. Augmentation can be done

under deep sedation on an outpatient basis to further

control expense. The esthetic outcome may be equally

acceptable in the eyes of the patient, while avoiding

the expense and potential morbidity of a more comprehensive operative procedure (Figs 2H and 2I).

To summarize, the desireable camouflage candidate

would meet the following criteria: an end-to-end posterior occlusion; an average or short facial height, with

some increase in overbite; mild to moderate mandibular crowding without excessive curve of Spee or incisor

compensation; periodontal support that will allow

expansion and proclination of the lower anterior teeth

without risk of compromise; and soft tissue relationships that are reasonably proportional and likely to

respond favorably to tooth movement.

Advancing the Case for Camouflage

It has been suggested that the actual choice of treatment in borderline cases may be largely a function

582

ORTHODONTIC CAMOUFLAGE VS ORTHOGNATHIC SURGERY

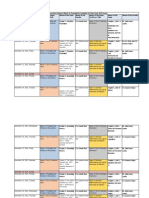

FIGURE 1. A, Normal facial proportions are evident in this frontal view of the patient. The slightly high smile line is a function of the lip

elevating over procumbent incisors during animation. B, In this profile view an acute nasolabial angle suggests that a component of maxillary

protrusion contributes to the Class II malocclusion. C, D, E, The maxillary and mandibular arches are well-formed with no crowding to suggest

the need for extraction. The full Class II malocclusion, with l0 mm of oveljet, will require extraction for camouflage, however, and is at the

limit of orthodontic correction.

o f which specialist the patient happens to contact. 17 Although somewhat tongue-in-cheek, this statement, in reality, m a y be disturbingly accurate. W i l m o t et al analyzed

a series of dentofacial patients' motivations for orthodontic or surgical treatment and examined the association

of these motivations with the severity of the skeletal

malocclusion. Patients in this study, especially those with

Class II relationships, were more motivated for orthodontic treatment than surgery. This is not surprising because

most individuals would prefer the least invasive treatment

that might address their concerns. In keeping with the

findings previously mentioned, there was tittle relationship between the cephalometric variables and motivations

for treatment. These findings, coupled with other research

on psychosocial and morphometric factors, offer some

guidelines that m a y be useful in a clinical setting. Epidemiologic, functional and economic information adds further support for the proposition that camouflage should

be given seriou~ consideration in a majority of postpubertal Class II patients.

PAUL M. THOMAS

583

FIGURE 1 (Cont'd). F, The cephalometric schematic confirms

horizontal maxillary excess and proclined maxillary incisors, in addition to an ample soft tissue chin contour. G, A computer-assisted

treatment simulation suggests that orthodontic camouflage will produce a satisfactory esthetic result. The plan demonstrated involves

extraction of the maxillary first premolars followed by maximum

anchorage retraction of the anterior teeth.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Proffit et al have suggested that successful orthodontic

camouflage becomes much less likely when the oveqet

is greater than 10 mm. Public health surveys of teenage

malocclusion indicate only 1.6% of those examined

would fall into this category.~ If the criteria for increased

facial height are used, some extrapolation from the public

health data is necessary. Increased facial height (vertical

growth pattern) is often accompanied by diminished

overbite or openbite and clockwise rotation of the mandible. Because no cephalometric data are included in the

public health information, overbite statistics must be substituted. Only 5.2% of the youths surveyed had edge to

edge or openbite relationships of the anterior teeth. The

percentage increases to 16.2 in African American teens.

Because the openbite is frequently combined with bialveolar protrusion in these individuals, correction with

extraction and orthodontics is generally successful. Using

the criteria suggested by Proffit et al, epidemiologic studies indicate the group of patients with Class II malocclusions requiring surgery on a morphologic basis is relatively small.

FUNCTIONAL IMPROVEMENT

The desire for functional improvement is often cited

as the justification for seeking surgical correction) 2

Advocates suggest that improved biomechanics and

masticatory efficiency result from surgical correction.

584

ORTHODONTIC CAMOUFLAGE VS ORTHOGNATHIC SURGERY

FIGURE 2. A, This frontal view suggests relatively normal transverse and vertical facial proportions. B, Mandibular deficiency is

evident on the profile view. Maxillary lip support is within normal

limits. C, D, E, The crowding in the lower dental arch suggests that

extraction may be necessary. Expansion is likely to procline the

incisors beyond the limits of good periodontal support. The occlusal

relationships and overjet are actually less severe than seen in the

patient in Figure 1 due to forward drift of the posterior mandibular

teeth. Correction, however, would require extraction in both arches,

with the likelihood of lower incisor retraction and residual overjet.

F, The cephalometric tracing shows components of both maxillary

protrusion and mandibular deficiency. The maxillary incisors are

already slightly upright and further retraction is best avoided.

PAUL M. THOMAS

585

FIGURE 2 (Cont'd). G, Treatment simulation confirms the undesireable profile changes that would result from orthodontic camouflage.

The nasolabial angle is markedly obtuse and there is inadequate chin projection. H, An advancement genioplasty helps with profile appearance

in the orthodontic camouflage simulation, but the lips are still undersupported. This may be an acceptable alternative, depending on the patient's

concerns and motivation for seeking treatment. L This computer-assisted treatment simulation demonstrates the result from extraction of the

lower first premolars, space closure, and surgical advancement of the mandible. The soft tissue relationships have better balance in the noselip-chin region.

586

ORTHODONTIC CAMOUFLAGE VS ORTHOGNATHICSURGERY

Much of the research in this area has involved bite

force measurement because it is relatively easy to record and analyze. ~8 Unfortunately, bite force does not

correlate with chewing efficiency and has little to do

with improved masticatory function) 9 For all the rhetoric regarding function, there is limited research involving changes in masticatory efficiency after orthognathic surgery. The existing studies deal with

prognathic patients and report no significant improvement in postoperative efficiency.2 In fact, in one report, the number of occlusal contacts decreased with

treatment, as did efficiency when compared with pretreatment and untreated prognathic controls. 2~ Although Class II malocclusion is a much more common

finding, this author is unaware of any research reporting changes in masticatory efficiency after treatment. Suggestions of improvement are subjective at

best or anecdotal in nature.

ECONOMIC FACTORS

Given the rhetoric surrounding the issue of healthcare delivery reform, the cost of treatment is a major

concern for both patient and provider alike. In 1987,

Dolan et a122reported the mean hospital cost (exclusive

of anesthesia professional fees) associated with a mandibular sagittal split osteotomy as being $3,086 with

a range from $1,997 to $4,561. These figures are for

a university hospital in central North Carolina and regional costs are likely to vary widely. Because the

study was conducted with data from patients treated

in 1985, inflation also must be considered for these

figures to be useful. The investigators cited the 1985

escalation of healthcare expenditures as about 9%, but

cautioned that this was the lowest annual increment

since 1965. Based on Consummer Price Index data

from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, hospital-related

charges have increased 150.4% in the 11-year period

from 1982 to 1993. 23 Using this 13.6% per year increment, the 1994 hospital charges for the same institution

could be in excess of $10,000 exclusive of all professional fees.

A recent survey indicated that the charges for a mandibular sagittal split osteotomy ranged from $1,500 to

$11,000, with an average fee of about $4,400. 24 The

assistant surgeon's fee also must be considered and is

usually about 20% to 25% of the surgeon's bill. These

figures are consistent with average fees from this author's locale. Orthodontic fees range from $3,000 to

$5,000 and anesthesiologist's fees from $600 to $900. 25

This brings the potential total expense for mandibular

advancement in a hospital setting to ($21,000). Greater

overhead expense is likely to make this figure considerably higher in selected locations. Using the same

sphere of reference, the surgical option is at least three

to four times the cost of orthodontic camouflage. Certainly this underscores the need for careful consider-

ation of the perceived benefit from orthognathic surg e r y versus the cost and risk.

Summary and Conclusions

Clearly, there are postpubertal patients with Class

II malocclusions for whom orthognathic surgery combined with orthodontics is the " b e s t " option, but epidemiologic information suggests they are a relatively

small percentage of the potential patient pool. The majority of patients fall into either an orthodontic treatment group or a borderline category. Many of these can

be treated successfully with orthodontic camouflage.

Research has shown psychosocial factors play a major

role in determining the patient's selection of a treatment option. This emphasizes the need for careful attention to global psychologic factors, with special emphasis on patient concerns regarding body image.

Morphometric criteria have been offered describing

appropriate candidates for orthodontic camouflage.

These are supported by a combination of research and

clinical experience. Patients who do not fit these criteria should not automatically be considered candidates

for surgery. Psychosocial research suggests a percentage of these individuals place less importance on facial

change and are content to improve dental esthetics and

function to the degree possible.

To assist in the decision-making process, patients

should be given the best information available regarding potential outcome. Currently this may involve

treatment simulation using a combination of computer

images and dental models. Caution has been suggested,

given the variability associated with predicting soft

tissue change. 26 There are additional legal concerns

regarding the implied guarantee of treatment outcome. 22'27 Correspondingly, the influence of this technology must be kept in perspective. Recent research

on the decision-making process found computer imaging to be an important factor in only 24% of the

patients studied. 28 However, the value of this technology for communication was underscored when these

same individuals ranked computer simulation as the

best information source when considering all diagnostic records.

The future of orthognathic surgery is uncertain,

given the current climate surrounding health care in

general. Coverage is being specifically excluded as

many patients change to low option policies or managed care plans. For those still having coverage, the

process of gaining prior approval has become increasingly stringent and slow. For those without coverage,

there is a trend toward developing "package deals"

to make care more affordable. It would appear that

although the demand for treatment will continue, the

orthognathic surgery option may become less feasible

and orthodontic camouflage more frequent. It continues to be imperative that we discuss treatment options

PAUL M. THOMAS

with our patients in an honest and forthright manner

to t h e b e s t o f o u r a b i l i t y . T h e i n f o r m a t i o n s h o u l d b e

free from personal bias and should incorporate the advantages and disadvantages of various options, including risk and economic information. Only then will our

patients be able to make a truly informed decision.

References

1. Kelly JE: An assessment of the occlusion of the teeth of youths

12-17 years, United States. Vital and Health Statistics, Data

from the National Health Survey, Series l l-Number 162,

February 1977, p 3

2. Profit WR, Field HW: Malocclusion and dentofacial deformity

in contemporary society, in Contemporary Orthodontics. St

Louis, MO, Mosby, 1993, pp 7-8

3. Witzig TW, Yerkes I: Functional jaw orthopedics; Mastering

more than technique, in Gelb H (ed): Clinical Management

of Head Neck and TMJ Pain and Dysfunction (ed 2) Philadelphia, PA, Saunders, 1985

4. Owen AH: Orthodontic/orthopedic treatment of craniomandibular dysfunction. Part 2. Posterior condylar displacement. J

Craniomandibular Prac 2:344, 1984

5. Kiyak HA, Bell R: Psychosocial considerations in surgery and

orthodontics, in Proffit WR, White RP Jr (eds): Surgical Orthodontic Treatment. St Louis, MO, Mosby, 1991, pp 71-96

6. Nelson C, Harkness M, Herbison P: Mandibular changes during

functional appliance treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthod

104:153, 1993

7. Thomas PM: Unpublished data, University of North Carolina

Dentofacial Program

8. Ackerman JL, Profit WR: The characteristics of malocclusion:

A modern approach to classification and diagnosis. Am J

Orthod 75:282, 1969

9. Weed LL: Medical records, medical education and patient care:

The problem-oriented record as a basic tool. Cleveland, OH,

1969, Case-Western Reserve Press

10. Dunlevy HA, White RP, Profit WR, OH, et al: Professional

and lay judgement of facial esthetic changes following orthognathic surgery. J Adult Orthod Orthognath Surg 2:151, 1987

11. Mayo KH, Dryland-Vig KWL, Vig PS, et al: Attitude variables

of dentofacial deformity patients: Demographic characteristics and associations. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 49:594, 1991

58"/

12. Flanary CM, Barnwell GM, Alexander JM: Patient perceptions

of orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod 88:137, 1985

13. Bell R, Kiyak HA, Joondeph DR, et al: Perceptions of facial

profile and their influence on the decision to undergo orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod 88:232, 1985

14. Griffin TJ: Perception of facial attractiveness and esthetic treatment goal preferences by patients, peer group, and professionals. Master's Thesis, University of North Carolina, 1994

15. Profit WR, Ackerman JL: Diagnosis and treatment planning,

in Graber TM, Vanarsdall RL Jr (eds): Orthodontics: Current

Principals and Treatment. St Louis, MO, Mosby, 1994

16. Profit WR, Phillips C, Tulloch JFC, et al: Surgical versus orthodontic correction of skeletal class II malocclusion in adolescents: Affects and indications. Int J Adult Orthod Orthog

Surg 7:209, 1992

17. Cassidy DW Jr, Herbosa EG, Rotskoff KS, et al: A comparison

of surgery and orthodontics in borderline adults with class

II, division I malocclusions. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop

104:455, 1993

18. Profit WR: Masticatory performance, muscle activity, and occlusal force in preorthognathic surgery patients: Discussion.

J Oral Maxillofac Surg 52:482, 1994

19. Tate GS, Throckmorton GS, Ellis E III, et al: Masticatory performance, muscle activity and occlusal force in preorthognathic

surgery patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 52:476, 1994

20. Shiratsuchi Y, Kouno K, Tashiro H: Evaluation of masticatory

function following orthognathic surgical correction of mandibular prognathism. J Cranio Max Fac Surg 19:299, 1991

21. Kobayashi T, Honma K, Nakajima T, et al: Masticatory function

in patients with mandibular prognathism before and after

orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 51:997, 1993

22. Dolan P, White RP Jr, Tnlloch JFC: An analysis of hospital

charges for orthognathic surgery. Int J Adult Orthod Orthog

Surg 1:9, 1987

23. Williams KR, Bentley JE: Survey findings on dental fees: A

comparison from 1982-93. J Am Dent Assoc 125:1260, 1994

24. Networker feedback: Survey of selected fees. American College

of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons Newsletter, October 1993

25. Personal Communication: Durham Anesthesia Associates, Durham, NC

26. Turpin DL: Computers coming on line for diagnosis and treatment planning. Angle Orthod 60:163, 1990 (editorial)

27. Sarver DM: Video imaging: The pros and cons. Angle Orthod

63:167, 1993

28. Hill B: Influence of video imaging on patients' expectations.

Master's Thesis, University of North Carolina, 1993

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- K Schleich Pharmacotherapy of Osteoporosis 2017 AUDIENCEDokumen32 halamanK Schleich Pharmacotherapy of Osteoporosis 2017 AUDIENCEBenjamin NgBelum ada peringkat

- NCCS Understanding Radiation Therapy (Eng)Dokumen20 halamanNCCS Understanding Radiation Therapy (Eng)Benjamin NgBelum ada peringkat

- Osteoporosis UpdateDokumen57 halamanOsteoporosis UpdatepuskesbinangunBelum ada peringkat

- Osteoporosis UpdateDokumen57 halamanOsteoporosis UpdatepuskesbinangunBelum ada peringkat

- Trauma ATACC Manual 2014 PDFDokumen460 halamanTrauma ATACC Manual 2014 PDFBenjamin Ng100% (1)

- BCA - Home GuidelineDokumen54 halamanBCA - Home GuidelineJan Kristoffer Aguilar UmaliBelum ada peringkat

- 4 Listgarten M. Electron Microscopic Study of The Gingivodental Junction of Man. Am J Anat 1966 119-147 (HWN)Dokumen31 halaman4 Listgarten M. Electron Microscopic Study of The Gingivodental Junction of Man. Am J Anat 1966 119-147 (HWN)Benjamin NgBelum ada peringkat

- Facial Trauma Clinical ExaminationDokumen10 halamanFacial Trauma Clinical ExaminationBenjamin NgBelum ada peringkat

- Travelshield DBSDokumen12 halamanTravelshield DBSBenjamin NgBelum ada peringkat

- Life Expectancy of Patients With Malignant Pleural Effusion Treated With Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Talc PleurodesisDokumen6 halamanLife Expectancy of Patients With Malignant Pleural Effusion Treated With Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Talc PleurodesisBenjamin NgBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Viscosity IA - CHEMDokumen4 halamanViscosity IA - CHEMMatthew Cole50% (2)

- Range of Muscle Work.Dokumen54 halamanRange of Muscle Work.Salman KhanBelum ada peringkat

- Thick Seam Mining Methods and Problems Associated With It: Submitted By: SAURABH SINGHDokumen13 halamanThick Seam Mining Methods and Problems Associated With It: Submitted By: SAURABH SINGHPrabhu PrasadBelum ada peringkat

- Genigraphics Poster Template 36x48aDokumen1 halamanGenigraphics Poster Template 36x48aMenrie Elle ArabosBelum ada peringkat

- Rustia V Cfi BatangasDokumen2 halamanRustia V Cfi BatangasAllen GrajoBelum ada peringkat

- Format For Handout - Comparative Models of EducationDokumen5 halamanFormat For Handout - Comparative Models of EducationAdrian AsiBelum ada peringkat

- Feyzin Oil Refinery DisasterDokumen8 halamanFeyzin Oil Refinery DisasterDavid Alonso Cedano EchevarriaBelum ada peringkat

- Geomatics Lab 6 (GPS)Dokumen24 halamanGeomatics Lab 6 (GPS)nana100% (1)

- Chapter 1-The Indian Contract Act, 1872, Unit 1-Nature of ContractsDokumen10 halamanChapter 1-The Indian Contract Act, 1872, Unit 1-Nature of ContractsALANKRIT TRIPATHIBelum ada peringkat

- CVR College of Engineering: UGC Autonomous InstitutionDokumen2 halamanCVR College of Engineering: UGC Autonomous Institutionshankar1577Belum ada peringkat

- Demo TeachingDokumen22 halamanDemo TeachingCrissy Alison NonBelum ada peringkat

- Volume 4-6Dokumen757 halamanVolume 4-6AKBelum ada peringkat

- New Wordpad DocumentDokumen6 halamanNew Wordpad DocumentJonelle D'melloBelum ada peringkat

- American Literature TimelineDokumen2 halamanAmerican Literature TimelineJoanna Dandasan100% (1)

- Latihan Soal Recount Text HotsDokumen3 halamanLatihan Soal Recount Text HotsDevinta ArdyBelum ada peringkat

- Infineum Ilsa Gf-6 API SP e JasoDokumen28 halamanInfineum Ilsa Gf-6 API SP e JasoDanielBelum ada peringkat

- Single-phase half-bridge inverter modes and componentsDokumen18 halamanSingle-phase half-bridge inverter modes and components03 Anton P JacksonBelum ada peringkat

- Biology 11th Edition Mader Test BankDokumen25 halamanBiology 11th Edition Mader Test BankAnthonyWeaveracey100% (44)

- G10 - Math - Q1 - Module 7 Grade 10Dokumen12 halamanG10 - Math - Q1 - Module 7 Grade 10Shua HongBelum ada peringkat

- Rigor Mortis and Lividity in Estimating Time of DeathDokumen2 halamanRigor Mortis and Lividity in Estimating Time of DeathfunnyrokstarBelum ada peringkat

- HDL Coder™ ReferenceDokumen487 halamanHDL Coder™ ReferenceVictor Colpo NavarreteBelum ada peringkat

- Gender and Other Cross Cutting Issues Mental HealthDokumen6 halamanGender and Other Cross Cutting Issues Mental HealthJamira Inoc SoboBelum ada peringkat

- Inbound 8511313797200267098Dokumen10 halamanInbound 8511313797200267098phan42Belum ada peringkat

- Captive Screws - Cap Head: Hex. SocketDokumen5 halamanCaptive Screws - Cap Head: Hex. SocketvikeshmBelum ada peringkat

- Pyrolysis ProjectDokumen122 halamanPyrolysis ProjectSohel Bangi100% (1)

- EMA Guideline on Calculating Cleaning LimitsDokumen4 halamanEMA Guideline on Calculating Cleaning LimitsshivanagiriBelum ada peringkat

- Participatory Assessment of Ragay Gulf Resources and SocioeconomicsDokumen167 halamanParticipatory Assessment of Ragay Gulf Resources and SocioeconomicsCres Dan Jr. BangoyBelum ada peringkat

- ATM ReportDokumen16 halamanATM Reportsoftware8832100% (1)

- Harajuku: Rebels On The BridgeDokumen31 halamanHarajuku: Rebels On The BridgeChristian Perry100% (41)

- IT Technician CVDokumen3 halamanIT Technician CVRavi KumarBelum ada peringkat