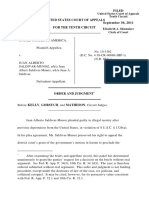

United States v. Hernandez-Villanueva, 4th Cir. (2007)

Diunggah oleh

Scribd Government DocsHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

United States v. Hernandez-Villanueva, 4th Cir. (2007)

Diunggah oleh

Scribd Government DocsHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

PUBLISHED

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

v.

HENRY GEOVANY HERNANDEZVILLANUEVA,

Defendant-Appellant.

No. 06-4211

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the District of Maryland, at Greenbelt.

Deborah K. Chasanow, District Judge.

(8:05-cr-00379-DKC)

Argued: November 30, 2006

Decided: January 10, 2007

Before KING and SHEDD, Circuit Judges, and

HAMILTON, Senior Circuit Judge.

Affirmed by published opinion. Senior Judge Hamilton wrote the

opinion, in which Judge King and Judge Shedd joined.

COUNSEL

ARGUED: Clark U. Fleckinger, II, Rockville, Maryland, for Appellant. Sandra Wilkinson, Assistant United States Attorney, OFFICE

OF THE UNITED STATES ATTORNEY, Greenbelt, Maryland, for

Appellee. ON BRIEF: Rod J. Rosenstein, United States Attorney,

Baltimore, Maryland, for Appellee.

UNITED STATES v. HERNANDEZ-VILLANUEVA

OPINION

HAMILTON, Senior Circuit Judge:

Henry Geovany Hernandez-Villanueva (Villanueva) appeals the

eighteen-month sentence imposed by the district court following his

plea of guilty to the charge of unauthorized reentry into the United

States, 8 U.S.C. 1326(a). We affirm.

I

Villanueva, a native of El Salvador, was deported from the United

States on April 17, 2004. Following his deportation, Villanueva illegally reentered the United States and was arrested at his mothers residence in Silver Spring, Maryland on May 31, 2005. At the time of

his arrest, Villanueva was eighteen years old and was residing at his

girlfriends residence, along with the couples infant daughter.

According to Villanueva, he reentered the United States to live with

and support his family.

Following his arrest, Villanueva was interviewed by law enforcement agents. Villanueva did not receive a Miranda* warning prior to

or during the interview. During the interview, Villanueva made statements concerning "La Mara Salvatrucha" or "MS-13," a violent gang

that operates nationwide through numerous violent local street gangs.

Villanueva also made statements concerning the violent activities of

his local MS-13 gang, "Langley Park Salvatrucha" (MS-13 LPS), and

other local MS-13 gangs operating in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. Villanueva offered to become a confidential informant in

order to provide continuing intelligence on MS-13 activity in the

Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. Following the interview, Bureau

of Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agent Robert Neives prepared a summary of the interview.

On August 15, 2005, Villanueva was charged by a federal grand

jury sitting in the District of Maryland with unauthorized reentry into

the United States, 8 U.S.C. 1326(a). On October 21, 2005, he pled

guilty to the charged offense.

*Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966).

UNITED STATES v. HERNANDEZ-VILLANUEVA

In preparation for sentencing, a Presentence Report (PSR) was prepared. The PSR set Villanuevas offense level at 8, U.S. Sentencing

Guidelines Manual (USSG) 2L1.2(a). After determining that Villanuevas criminal history category was I and that he was entitled to a

two level reduction for acceptance of responsibility, id. 3E1.1(a),

the PSR calculated Villanuevas sentencing range to be 0 to 6

months imprisonment.

At sentencing, the government argued, consistent with its prehearing submission, that a sentence higher than that called for by the Sentencing Guidelines was warranted because Villanueva was, inter alia,

a member of MS-13 LPS. In support of its argument, the government

introduced the testimony of George Norris, a sergeant with the Prince

Georges County Police Department and an expert in the operations

and affairs of MS-13 in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area.

According to Sergeant Norris, MS-13 began in the 1980s in Los

Angeles, California when numerous El Salvadorian immigrants

banded together to form a gang to combat the hostilities leveled

against them by Mexican street gangs. Over time, as the number of

El Salvadorian immigrants in this country grew, so did the size of

MS-13, as MS-13 formed local MS-13 gangs or "cliques" in other

areas of the country, including several in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. In general, each local MS-13 gang holds regular meetings to discuss the business of the local gang and MS-13 in general,

and each MS-13 member is required to pay dues to his local gang.

Some of the money paid in dues is remitted to MS-13; other money

is used by the local gang for a variety of legal and illegal activities.

In a nutshell, like most other street gangs, the basic purpose of MS13 and each of its local gangs is "to control the streets, to be the number one gang." This purpose is achieved "through intimidation, fear,

and violence."

Based on his training and experience, Sergeant Norris opined that

Villanueva was, at the time of his arrest in May 2005, still an active

member of MS-13 LPS. He based this opinion on several factors.

First, Sergeant Norris observed that, during the post-arrest interview,

Villanueva provided detailed, current information concerning MS-13

gang activity in the Washington D.C. metropolitan area, including

descriptions of recent violent criminal activity. Second, Sergeant Nor-

UNITED STATES v. HERNANDEZ-VILLANUEVA

ris observed that Villanueva used the present tense when talking about

his membership in MS-13 LPS and the activities of other members in

his gang and other local MS-13 gangs. Third, Sergeant Norris pointed

to Villanuevas desire to be a confidential informant for law enforcement. According to Sergeant Norris, to be a confidential informant,

Villanueva had to be a member of a local MS-13 gang, because, given

the violent and close-knit nature of a local MS-13 gang, nonmembers

would not be in a position to provide meaningful intelligence. Fourth,

Sergeant Norris testified that, about a week prior to Villanuevas

arrest, he personally observed several MS-13 LPS members visit Villanueva at his (Villanuevas) girlfriends residence. According to Sergeant Norris, if Villanueva was not an active member of MS-13 LPS,

in the sense that he was not attending his local gang meetings and/or

paying dues to MS-13 LPS, other members would kill him, which is

the action taken against an individual that tries to leave MS-13.

Finally, Sergeant Norris relied on photographs taken of Villanueva

both before his April 2004 deportation and after his arrest in May

2005. These photographs demonstrated that Villanueva acquired tattoos in the time frame between his deportation and his later arrest,

several of which specifically related to MS-13. For example, Sergeant

Norris explained that Villanueva had acquired on his abdomen a tattoo of an "M" and a "S." Sergeant Norris also referenced another

recent MS-13 tattoo, which depicted a tombstone memorializing the

death of MS-13 LPS member "Satancio," with the date February 2,

2005.

In response to the governments case at sentencing, Villanueva first

objected to the governments use of the statements he made during

the post-arrest interview. Next, Villanueva argued that a sentence

above the advisory sentencing range was unwarranted because there

was no evidence that he engaged in any criminal activity. Finally, he

argued that it was impermissible for the government to seek a sentence above the advisory sentencing range merely because he chose

to occasionally associate with members of MS-13 LPS.

In sentencing Villanueva, the district court first overruled Villanuevas Miranda objection to the courts consideration of the statements he made during the post-arrest interview. Next, in accordance

with the PSR, the court found that Villanuevas sentencing range was

UNITED STATES v. HERNANDEZ-VILLANUEVA

0 to 6 months imprisonment. Then, the court turned to the factors set

forth in 18 U.S.C. 3553(a) to determine if a variance sentence was

appropriate. In examining the nature and circumstances of Villanuevas offense under 3553(a)(1), the court found that, although he

came back "very soon after deportation primarily because of family"

considerations, he continued to associate, after his reentry, with members of MS-13 LPS, "individuals that he knew were violent criminals." Regarding Villanuevas history and characteristics, the court

noted that, although Villanueva is young and has a family,

[o]n the other hand, he has exhibited by the tattoos and his

association a continued lure of the MS-13 culture, which I

find is violent and dangerous to himself as well as to others

in the community. He has not yet developed or demonstrated a maturity, a backbone, a character to turn things

around.

The court then examined the specific factors set forth in 3553(a)(2)

and concluded that a longer sentence than the sentencing range recommended by the Guidelines was warranted to promote respect for

the law, deter further criminal conduct, and protect the public from

further crimes committed by Villanueva (such as another illegal reentry). Finally, the court discussed its general concerns about Villanuevas gang activity:

It may well be extraordinarily difficult to disassociate ones

self from the MS-13 once one has been a member. This person standing before me has not . . . demonstrated any true

desire to do that. I find that he has accumulated new tattoos

since he was deported. He even acknowledged joining a

clique in El Salvador . . . .

He well understands the structure and had continued to participate in it. It was a gang that is terrorizing the community

and [gang] activity cannot be countenanced. Whether he has

personally participated in any violent activity is really not

the only question. There is certainly no evidence that he

directly has, but he is giving aid and comfort to those who

do, and he risks violence to himself as well. Its simply not

UNITED STATES v. HERNANDEZ-VILLANUEVA

a group to be associated with. Its dangerous for everyone

involved.

After considering the advisory sentencing range and the 3553(a)

factors, the district court concluded that a variance sentence was warranted, and the court sentenced Villanueva to eighteen months

imprisonment, which was twelve months higher than the high end of

Villanuevas sentencing range, but was six months below the statutory maximum sentence of twenty-four months imprisonment. Villanueva noted a timely appeal.

II

Villanueva first challenges the district courts consideration of the

statements he made during the post-arrest interview. These statements

were admitted through the testimony of Sergeant Norris and through

Agent Neives summary of the interview.

A district courts ruling on the admissibility of evidence at sentencing is reviewed for an abuse of discretion. United States v. Hopkins,

310 F.3d 145, 154 (4th Cir. 2002). In applying this standard, we are

mindful that the wide latitude on evidentiary matters enjoyed by trial

courts is even greater for sentencing courts, because the Federal Rules

of Evidence do not apply at sentencing. Id. Indeed, in resolving any

dispute concerning a factor pertinent to the sentencing decision, "the

court may consider relevant information without regard to its admissibility under the rules of evidence applicable at trial, provided that the

information has sufficient indicia of reliability to support its probable

accuracy." USSG 6A1.3(a), p.s. Moreover, in selecting a particular

sentence within the sentencing range (or deciding whether to depart

or vary from that range), a court "may consider, without limitation,

any information concerning the background, character and conduct of

the defendant, unless otherwise prohibited by law." Id. 1B1.4; see

also 18 U.S.C. 3661 ("No limitation shall be placed on the information concerning the background, character, and conduct of a person

convicted of an offense which a court of the United States may

receive and consider for the purpose of imposing an appropriate sentence.").

In this case, Villanueva argues that the district courts consideration of the statements he made during the post-arrest interview vio-

UNITED STATES v. HERNANDEZ-VILLANUEVA

lated his Miranda rights. The district court admitted the statements,

concluding that, even if the statements were obtained in violation of

Miranda, the evidence was reliable, Villanuevas statements were

voluntarily made, and there was no evidence of improper police conduct in eliciting the statements.

Unfortunately for Villanueva, his argument is foreclosed by our

decision earlier this year in United States v. Nichols, 438 F.3d 437

(4th Cir. 2006). In that case, we held that a statement obtained in violation of Miranda is admissible at sentencing unless there is evidence

that the statement was "actually coerced or otherwise involuntary." Id.

at 444.

In our case, it is clear that Villanueva does not meet the weighty

burden demanded by Nichols. In making his statements, Villanueva

was attempting to avoid certain deportation. He spoke willingly and

candidly in hopes of obtaining favorable treatment by the government. The circumstances surrounding the statements simply do not

suggest that Villanueva was coerced into making the statements or

that the statements were otherwise involuntary.

III

Villanueva also argues that the eighteen-month sentence imposed

by the district court is unreasonable. In imposing a sentence after

United States v. Booker, 543 U.S. 220 (2005), a sentencing court must

engage in a multi-step process. First, the court must correctly determine, after making appropriate findings of fact, the applicable sentencing range. United States v. Hughes, 401 F.3d 540, 546 (4th Cir.

2005). Next, the court must "determine whether a sentence within that

range . . . serves the factors set forth in 3553(a) and, if not, select

a sentence [within statutory limits] that does serve those factors."

United States v. Green, 436 F.3d 449, 456 (4th Cir. 2006). The court

must articulate the reasons for the sentence imposed, particularly

explaining any departure or variance from the sentencing range.

Hughes, 401 F.3d at 546 & n.5. The explanation of a variance sentence must be tied to the factors set forth in 3553(a) and must be

accompanied by findings of fact as necessary. Green, 436 F.3d at

455-56.

UNITED STATES v. HERNANDEZ-VILLANUEVA

We review the sentence imposed for reasonableness, considering

"the extent to which the sentence . . . comports with the various, and

sometimes competing, goals of 3553(a)." United States v. Moreland, 437 F.3d 424, 433 (4th Cir. 2006). When we review a sentence

outside the advisory sentencing rangewhether as a product of a

departure or a variancewe consider whether the sentencing court

acted reasonably both with respect to its decision to impose such a

sentence and with respect to the extent of the divergence from the

sentencing range. See id. at 433-34 (variance sentence); United States

v. Hairston, 96 F.3d 102, 106 (4th Cir. 1996) (departure sentence). If

a court provides an inadequate statement of reasons or relies on

improper factors in imposing a sentence outside the properly calculated advisory sentencing range, the sentence will be found unreasonable and vacated. Green, 436 F.3d at 457.

In this case, the district court considered the advisory sentencing

range and considered the relevant statutory sentencing factors under

3553(a). The court then concluded that the sentencing range under

the Guidelines failed to account for the fact that Villanueva was a

member of a violent local MS-13 gang and that Villanueva illegally

reentered the United States and continued his association with this

violent gang. The court also concluded that the sentencing range

failed to sufficiently promote respect for the law, deter further criminal conduct, and protect the public from further crimes committed by

Villanueva. We conclude that all of these considerations support the

decision of the court to impose a sentence above the advisory sentencing range and that any associational rights enjoyed by Villanueva

were not violated. Cf. Dawson v. Delaware, 503 U.S. 159, 165 (1992)

("[T]he Constitution does not erect a per se barrier to the admission

of evidence concerning ones beliefs and associations at sentencing

simply because those beliefs and associations are protected by the

First Amendment.").

We also conclude that the length of the sentence was reasonable.

The advisory sentencing range under the Guidelines was a term of

imprisonment of 0 to 6 months. The district court sentenced Villanueva to eighteen months imprisonment. The court reasonably concluded that a variance sentence of an additional twelve months

imprisonment was necessary to account for the fact that Villanueva

not only illegally reentered the United States but also continued his

UNITED STATES v. HERNANDEZ-VILLANUEVA

association with a violent street gang after his reentry. Violence is a

way of life for the members of local MS-13 gangs, and the court

understandably sought to fashion a reasonable sentence to stymie Villanuevas ability to associate with any local MS-13 gang, with the

hope that further removing him from the violent lures of a local MS13 gang would increase his chances of turning his life around. Moreover, a longer sentence was appropriate to sufficiently promote Villanuevas respect for the law, deter further criminal conduct (i.e., deter

other deported MS-13 members from reentering the United States to

continue in this country their association with the gang), and protect

the public from further crimes committed by Villanueva (e.g., protecting the public from another illegal reentry). In sum, although an

eighteen-month sentence is three times the high end of the 0 to 6

months sentencing range, the sentence, which is only seventy-five

percent of the two-year statutory maximum sentence, unquestionably

serves the 3553(a) factors. Cf. United States v. Davenport, 445 F.3d

366, 372 (4th Cir. 2006) (holding that a sentence more than three

times the top of the advisory sentencing range was unreasonable

where the factors relied upon by the district court did not justify such

a sentence and the court failed to explain how the variance sentence

served the 3553(a) factors).

IV

For the reasons stated herein, the judgment of the district court is

affirmed.

AFFIRMED

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- United States v. Palacios, 677 F.3d 234, 4th Cir. (2012)Dokumen24 halamanUnited States v. Palacios, 677 F.3d 234, 4th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Carlos Mauricio Lovo Torres AffidavitDokumen9 halamanCarlos Mauricio Lovo Torres AffidavitEmily BabayBelum ada peringkat

- Alexander Rivas AffidavitDokumen8 halamanAlexander Rivas AffidavitEmily BabayBelum ada peringkat

- Revised Opinion PublishedDokumen24 halamanRevised Opinion PublishedScribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Cathy Woods Files Lawsuit Against City of Reno, Washoe CountyDokumen34 halamanCathy Woods Files Lawsuit Against City of Reno, Washoe CountyAnonymous q4nRl3SuCnBelum ada peringkat

- Moisés Humberto Rivera LunaDokumen42 halamanMoisés Humberto Rivera LunaLoida MartínezBelum ada peringkat

- United States v. Josette Jacobs, 431 F.3d 99, 3rd Cir. (2005)Dokumen22 halamanUnited States v. Josette Jacobs, 431 F.3d 99, 3rd Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- All Against The Law: The Criminal Activities of the Depression Era Bank Robbers, Mafia, FBI, PolDari EverandAll Against The Law: The Criminal Activities of the Depression Era Bank Robbers, Mafia, FBI, PolBelum ada peringkat

- S-172: Lee Harvey Oswald Links to Intelligence AgenciesDari EverandS-172: Lee Harvey Oswald Links to Intelligence AgenciesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- ms-13 Final PaperDokumen6 halamanms-13 Final Paperapi-546282473Belum ada peringkat

- Wrongful Death SuitDokumen14 halamanWrongful Death SuitErin FuchsBelum ada peringkat

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth Circuit.: Nos. 81-5279 To 81-5282Dokumen8 halamanUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth Circuit.: Nos. 81-5279 To 81-5282Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Lancaster Vs WorldDokumen23 halamanLancaster Vs WorldBrian LancasterBelum ada peringkat

- The Third Terrorist: The Middle East Connection to the Oklahoma City BombingDari EverandThe Third Terrorist: The Middle East Connection to the Oklahoma City BombingBelum ada peringkat

- The Second: Race and Guns in a Fatally Unequal AmericaDari EverandThe Second: Race and Guns in a Fatally Unequal AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (18)

- FBI Black Identity Extremist COINTELPRO LawsuitDokumen4 halamanFBI Black Identity Extremist COINTELPRO LawsuitRyan GallagherBelum ada peringkat

- The Ferguson Report: Department of Justice Investigation of the Ferguson Police DepartmentDari EverandThe Ferguson Report: Department of Justice Investigation of the Ferguson Police DepartmentBelum ada peringkat

- Hayet Naser Gomez v. Alfredo Jose Salvi Fuenmayor, 11th Cir. (2016)Dokumen21 halamanHayet Naser Gomez v. Alfredo Jose Salvi Fuenmayor, 11th Cir. (2016)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Rape Is Rape: How Denial, Distortion, and Victim Blaming Are Fueling a Hidden Acquaintance Rape CrisisDari EverandRape Is Rape: How Denial, Distortion, and Victim Blaming Are Fueling a Hidden Acquaintance Rape CrisisPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (10)

- United States v. Alphonso Eugene Alston, 56 F.3d 62, 4th Cir. (1995)Dokumen5 halamanUnited States v. Alphonso Eugene Alston, 56 F.3d 62, 4th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Cases in ConstiDokumen55 halamanCases in ConstianneasfsdBelum ada peringkat

- UnpublishedDokumen22 halamanUnpublishedScribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Trump Supporter LawsuitDokumen44 halamanTrump Supporter LawsuitLaw&CrimeBelum ada peringkat

- Cathy Woods LawsuitDokumen43 halamanCathy Woods LawsuitshreveporttimesBelum ada peringkat

- Leland Yee AffidavitDokumen137 halamanLeland Yee AffidavitZelenyBelum ada peringkat

- Speech by The US Attorney General - 0706051Dokumen7 halamanSpeech by The US Attorney General - 0706051legalmattersBelum ada peringkat

- 11-11-14 The Limits of Free Speech On The Web - Information Pertaining To Corruption of The US Justice SystemDokumen5 halaman11-11-14 The Limits of Free Speech On The Web - Information Pertaining To Corruption of The US Justice SystemHuman Rights Alert - NGO (RA)Belum ada peringkat

- Custodial InvestigationDokumen74 halamanCustodial Investigationclaire beltran100% (1)

- Court of Injustice: Law Without Recognition in U.S. ImmigrationDari EverandCourt of Injustice: Law Without Recognition in U.S. ImmigrationBelum ada peringkat

- The Golden Door: An African-American & The Criminal Justice SystemDari EverandThe Golden Door: An African-American & The Criminal Justice SystemBelum ada peringkat

- Ludem Semprit v. U.S. Attorney General, 11th Cir. (2010)Dokumen7 halamanLudem Semprit v. U.S. Attorney General, 11th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- United States Court of Appeals: PublishedDokumen59 halamanUnited States Court of Appeals: PublishedScribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Migrant Crossings: Witnessing Human Trafficking in the U.S.Dari EverandMigrant Crossings: Witnessing Human Trafficking in the U.S.Belum ada peringkat

- Attorneys For Plaintiffs: Complaint and Jury DemandDokumen33 halamanAttorneys For Plaintiffs: Complaint and Jury DemandAsbury Park PressBelum ada peringkat

- FBI Special Agent Compaint Against Trans Nazi Dominatrix Planning A Mass ShootingDokumen23 halamanFBI Special Agent Compaint Against Trans Nazi Dominatrix Planning A Mass ShootingRed Voice NewsBelum ada peringkat

- Randy WeaverDokumen8 halamanRandy Weaverzannonymous7Belum ada peringkat

- United States v. Alapizco-Valenzuela, 546 F.3d 1208, 10th Cir. (2008)Dokumen25 halamanUnited States v. Alapizco-Valenzuela, 546 F.3d 1208, 10th Cir. (2008)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- United States v. Alvarez MachainDokumen2 halamanUnited States v. Alvarez MachainAnonymous PYorid9ABelum ada peringkat

- Miranda Doctrine DigestsDokumen28 halamanMiranda Doctrine DigestschikkietingBelum ada peringkat

- 2b22799f-f7c1-4280-9274-8c59176f78b6Dokumen190 halaman2b22799f-f7c1-4280-9274-8c59176f78b6Andrew Martinez100% (1)

- USCOURTS Ca7 16 01589 0Dokumen5 halamanUSCOURTS Ca7 16 01589 0Boe SupersportBelum ada peringkat

- United States Court of Appeals: For The First CircuitDokumen26 halamanUnited States Court of Appeals: For The First CircuitScribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- United States v. Saldivar-Munoz, 10th Cir. (2011)Dokumen13 halamanUnited States v. Saldivar-Munoz, 10th Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- In The United States District Court For The Western District of WisconsinDokumen25 halamanIn The United States District Court For The Western District of Wisconsinanon_884584108Belum ada peringkat

- United States v. William R. Perl, 584 F.2d 1316, 4th Cir. (1978)Dokumen11 halamanUnited States v. William R. Perl, 584 F.2d 1316, 4th Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- 2014 09 22 Federal ComplaintDokumen19 halaman2014 09 22 Federal ComplaintThe Law Offices of L. Clayton BurgessBelum ada peringkat

- In Pursuit: The Hunt for the Beltway SnipersDari EverandIn Pursuit: The Hunt for the Beltway SnipersPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- Cases - National SecurityDokumen191 halamanCases - National SecurityLENNY ANN ESTOPINBelum ada peringkat

- Invasion: How America Still Welcomes Terrorists, Criminals, And Other Foreign Menaces To Our ShoresDari EverandInvasion: How America Still Welcomes Terrorists, Criminals, And Other Foreign Menaces To Our ShoresPenilaian: 2.5 dari 5 bintang2.5/5 (10)

- Summary of Find Me the Votes by Michael Isikoff and Daniel Klaidman: A Hard-Charging Georgia Prosecutor, a Rogue President, and the Plot to Steal an American ElectionDari EverandSummary of Find Me the Votes by Michael Isikoff and Daniel Klaidman: A Hard-Charging Georgia Prosecutor, a Rogue President, and the Plot to Steal an American ElectionBelum ada peringkat

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen21 halamanCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen9 halamanUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen7 halamanCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen8 halamanPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen4 halamanUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen20 halamanUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen100 halamanHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen6 halamanBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen2 halamanGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen15 halamanApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen5 halamanWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen2 halamanUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen22 halamanConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen25 halamanPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen25 halamanUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen50 halamanUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDokumen10 halamanPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen25 halamanUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen5 halamanUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDokumen14 halamanPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen10 halamanNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen15 halamanUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen9 halamanNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDokumen24 halamanPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen18 halamanWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDokumen17 halamanPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen27 halamanUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen5 halamanPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen7 halamanUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokumen4 halamanUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- People of The Phils vs. Antero GamezDokumen6 halamanPeople of The Phils vs. Antero GamezLordreign SiosonBelum ada peringkat

- Budlong vs. ApalisokDokumen2 halamanBudlong vs. ApalisokAthina Maricar Cabase100% (1)

- Sean Airic Pontañeles Bsamt-1 Alpha Mr. Rodan Kent Ganar: Pros of Death PenaltyDokumen2 halamanSean Airic Pontañeles Bsamt-1 Alpha Mr. Rodan Kent Ganar: Pros of Death PenaltyAndréiBelum ada peringkat

- Gandhi - Collected Works Vol 09Dokumen504 halamanGandhi - Collected Works Vol 09Nrusimha ( नृसिंह )100% (1)

- Country Profile United KingdomDokumen5 halamanCountry Profile United KingdomwickeretteBelum ada peringkat

- Decisions Stella v. Italy and Other Applications and Rexhepi v. Italy and Other Applications - Non-Exhaustion of Domestic RemediesDokumen3 halamanDecisions Stella v. Italy and Other Applications and Rexhepi v. Italy and Other Applications - Non-Exhaustion of Domestic RemediesMihai IvaşcuBelum ada peringkat

- A01 - The RisingDokumen182 halamanA01 - The RisingVeronica HansonBelum ada peringkat

- Criminality Among Women RRLDokumen4 halamanCriminality Among Women RRLIt's Me MyraBelum ada peringkat

- Board of Pardons and ParoleDokumen7 halamanBoard of Pardons and ParoleMary An PadayBelum ada peringkat

- PPP Grammar Lesson Table 25.11.19Dokumen2 halamanPPP Grammar Lesson Table 25.11.19hichem100% (2)

- Call of Duty Black Ops WalkthroughDokumen37 halamanCall of Duty Black Ops WalkthroughStefan DraganBelum ada peringkat

- Camp Fermo in EnglishDokumen8 halamanCamp Fermo in EnglishCristian SprljanBelum ada peringkat

- JuvenileDokumen17 halamanJuvenileIbra SaidBelum ada peringkat

- The Billionaire of Bodog - Living The DreamDokumen4 halamanThe Billionaire of Bodog - Living The DreambioenergyBelum ada peringkat

- LEC 2015 Pre-Test in Correctional Ad (CA 101-102) For FBDokumen10 halamanLEC 2015 Pre-Test in Correctional Ad (CA 101-102) For FBcriminologyallianceBelum ada peringkat

- Criminal Law BarVenture 2024Dokumen3 halamanCriminal Law BarVenture 2024Dapstone EnterpriseBelum ada peringkat

- G.R. NoDokumen10 halamanG.R. NoCAGELCO IIBelum ada peringkat

- Why It Pays To Be A Jerk - The AtlanticDokumen24 halamanWhy It Pays To Be A Jerk - The AtlanticsambhagooBelum ada peringkat

- Benjamin F. Washington v. Secretary of Health and Human Services, 718 F.2d 608, 3rd Cir. (1983)Dokumen4 halamanBenjamin F. Washington v. Secretary of Health and Human Services, 718 F.2d 608, 3rd Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Escape Plan WorkshopDokumen6 halamanEscape Plan WorkshopMichael CaseyBelum ada peringkat

- Term PaperDokumen9 halamanTerm Paperapi-418430058Belum ada peringkat

- Crimes in The Jasenovac Camp, Zagreb 1946 (State Commission of Croatia, 2008)Dokumen74 halamanCrimes in The Jasenovac Camp, Zagreb 1946 (State Commission of Croatia, 2008)ayazan2006Belum ada peringkat

- Ankle Monitor ContractDokumen1 halamanAnkle Monitor ContractScott EllisBelum ada peringkat

- Match Fixing - Kevin Carpenter PDFDokumen12 halamanMatch Fixing - Kevin Carpenter PDFAmogh PareekBelum ada peringkat

- Human Rights Law NotesDokumen9 halamanHuman Rights Law NotesMay Angelica TenezaBelum ada peringkat

- Andrusiak I.V. The Use of Articles in EnglishDokumen56 halamanAndrusiak I.V. The Use of Articles in EnglishAndy RadionovBelum ada peringkat

- LVL 27 Prince of UndeathDokumen98 halamanLVL 27 Prince of UndeathArturo Partida92% (13)

- Ra 10707Dokumen3 halamanRa 10707Frances Ann Teves100% (1)

- Prof. (DR.) Nirmal Kanti ChakrabartiDokumen16 halamanProf. (DR.) Nirmal Kanti ChakrabartiPooja sehrawatBelum ada peringkat

- Italics Dash Hyphen BoldDokumen14 halamanItalics Dash Hyphen BoldItzel EstradaBelum ada peringkat