Approach Considerations, Pharmacologic Therapy, Inpatient Care

Diunggah oleh

Zenit DjajaHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Approach Considerations, Pharmacologic Therapy, Inpatient Care

Diunggah oleh

Zenit DjajaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Malaria Treatment & Management: Approach Considerations, Pharmac...

1 of 5

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/221134-treatment#showall

Malaria Treatment & Management

Author: Thomas E Herchline, MD; Chief Editor: Michael Stuart Bronze, MD more...

Updated: Oct 27, 2015

Approach Considerations

Failure to consider malaria in the differential diagnosis of a febrile illness in a patient

who has traveled to an area where malaria is endemic can result in significant

morbidity or mortality, especially in children and in pregnant or immunocompromised

patients.

Mixed infections involving more than 1 species of Plasmodium may occur in areas of

high endemicity and multiple circulating malarial species. In these cases, clinical

differentiation and decision making will be important; however, the clinician should

have a low threshold for including the possible presence of P falciparum in the

treatment considerations.

Occasionally, morphologic features do not permit distinction between P falciparum

and other Plasmodium species. In such cases, patients from a P falciparum

endemic area should be presumed to have P falciparum infection and should be

treated accordingly.

In patients from Southeast Asia, consider the possibility of P knowlesi infection. This

species frequently causes hyperparasitemia and the infection tends to be more

severe than infections with other non P falciparum plasmodia. It should be treated

as P falciparum infection.

P falciparum is resistant to chloroquine treatment except in Haiti, the Dominican

Republic, parts of Central America, and parts of the Middle East. Resistance is rare in

P vivax infection, and P ovale and P malariae remain sensitive to chloroquine.

Primaquine is required in the treatment of P ovale and P vivax infection in order to

eliminate the hypnozoites (liver phase).

In the United States, patients with P falciparum infection are often treated on an

inpatient basis in order to observe for complications attributable to either the illness or

its treatment.

Pregnancy

Pregnant women, especially primigravid women, are up to 10 times more likely to

contract malaria than nongravid women. Gravid women who contract malaria also have

a greater tendency to develop severe malaria. Unlike malarial infection in nongravid

individuals, pregnant women with P vivax are at high risk for severe malaria, and

those with P falciparum have a greatly increased predisposition for severe malaria as

well.

For these reasons, it is especially important that nonimmune pregnant women in

endemic areas use the proper pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic prophylaxis.

If a pregnant woman becomes infected, she should know that many of the antimalarial

and antiprotozoal drugs used to treat malaria are safe for use during pregnancy for

the mother and the fetus. Therefore, the medications should be used, since the

benefits of these drugs greatly outweigh the risks associated with leaving the infection

untreated.

Pediatrics

In children, malaria has a shorter course, often rapidly progressing to severe malaria.

Children are more likely to present with hypoglycemia, seizures, severe anemia, and

sudden death, but they are much less likely to develop renal failure, pulmonary

edema, or jaundice.

Cerebral malaria results in neurologic sequelae in 9-26% of children, but of these

sequelae, approximately one half completely resolve with time.

Most antimalarial drugs are very effective and safe in children, provided that the

proper dosage is administered. Children commonly recover from malaria, even

severe malaria, much faster than adults.

Diet and activity

Patients with malaria should continue intake and activity as tolerated.

Monitoring

Patients with non P falciparum malaria who are well can usually be treated on an

outpatient basis. Obtain blood smears every day to demonstrate response to

treatment. The sexual stage of the protozoan, the gametocyte, does not respond to

most standard medications (eg, chloroquine, quinine), but gametocytes eventually die

and do not pose a threat to the individual's health.

Pharmacologic Therapy

IV preparations of antimalarials are available for the treatment of severe complicated

malaria, including artesunate and quinidine gluconate, which is used as a substitute for

23/05/2016 22:59

Malaria Treatment & Management: Approach Considerations, Pharmac...

2 of 5

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/221134-treatment#showall

the IV quinine available in countries outside of the United States.

In a 2010 randomized study done in 11 African centers, children (age < 15 years) with

severe P falciparum malaria had reduced mortality after treatment with IV artesunate,

as compared with IV quinine. Development of coma, seizures, and posttreatment

hypoglycemia were each less common in patients treated with artesunate.[18]

Evidence from a meta-analysis including 7429 subjects from 8 trials shows a

decreased risk of death using parenteral artesunate compared to quinine for the

treatment of severe malaria in adults and children.[19]

P falciparum drug resistance is common in endemic areas, such as Africa. Standard

antimalarials, such as chloroquine and antifolates (sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine), are

ineffective in many areas. Because of this increasing prevalence of drug resistance

and a high likelihood of resistance development to new agents, combination therapy

is now becoming the standard of care for treatment of P falciparum infection

worldwide. In April 2009, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the

use of artemisinins, a new class of antimalarial agent.[20]

Despite the activity of artemisinin and its derivatives, monotherapy with these agents

has been associated with high rates of relapse. This may be due to the temporary

arrest of the growth of ring-stage parasites (dormancy) after exposure to artemisinin

drugs. For this reason, monotherapy with artemisinin drugs is not recommended.[21]

Rectal artesunate has been used for pretreatment of children in resource-limited

settings as a bridge therapy until the patient can access health care facilities for

definitive IV or oral therapy.[22]

Despite their being a fairly new antimalarial class, resistance to artemisinins has been

reported in some parts of southeast Asia (Cambodia).[23]

In the United States, artemether and lumefantrine tablets (Coartem) can be used to

treat acute uncomplicated malaria. Artesunate, a form of artemisinin that can be used

intravenously, is available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC). Other combinations, such as atovaquone and proguanil HCL (Malarone) or

quinine in combination with doxycycline or clindamycin, remain highly efficacious.

Malaria vaccine production and distribution continues to be in the research and

development stage.[24, 25, 26] In 2015, European Union (EU) regulators approved the

world's first malaria vaccine for use outside the EU among children aged 6 weeks to

17 months. The new vaccine (Mosquirix, GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals), which includes

a vaccine for hepatitis B, is awaiting review by the World Health Organization (WHO).

The earliest any malaria-endemic country could license the product is 2017,

according to WHO. Mosquirix targets P falciparum. It limits the parasite's ability to

infect, mature, and multiply in the liver.[27]

When making treatment decisions, it is essential to consider the possibility of

coinfection with more than 1 species. Reports of P knowlesi infection suggest that

coinfection is common.[4] It has also been demonstrated that up to 39% of patients

infected with this species may develop severe malaria. In cases of severe P

knowlesi malaria, IV therapy with quinine or artesunate is recommended.[5]

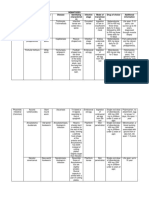

The following is a summary of general recommendations for the treatment of malaria:

P falciparum malaria - Quinine-based therapy is with quinine (or quinidine)

sulfate plus doxycycline or clindamycin or pyrimethamine-sulfadoxine;

alternative therapies are artemether-lumefantrine, atovaquone-proguanil, or

mefloquine

P falciparum malaria with known chloroquine susceptibility (only a few areas in

Central America and the Middle East) - Chloroquine

P vivax, P ovale malaria - Chloroquine plus primaquine; however, a 2012

study of Indonesian soldiers demonstrated that primaquine combined with

newer nonchloroquine antimalarials killed dormant P vivax parasites and

prevented malaria relapse; [28, 29] the combination of dihydroartemisininpiperaquine with primaquine had 98% efficacy against relapse, suggesting that

this regimen could become a useful alternative to primaquine plus chloroquine,

the clinical utility of which is being threatened by worsening chloroquine

resistance

P malariae malaria - Chloroquine

P knowlesi malaria Recommendations same as those for P falciparum

malaria.

In July 2013, the FDA updated its warning about mefloquine hydrochloride to include

neurologic side effects, along with the already known risk of adverse psychiatric

events such as anxiety, confusion, paranoia, and depression. The information, which

is included in the patient medication guide and in a new boxed warning on the label,

cautions that vestibular symptoms, which include dizziness, loss of balance, vertigo,

and tinnitus, can occur.[30, 31]

The FDA also warns that vestibular side effects can persist long after treatment has

ended and may become permanent. In addition, clinicians are warned against

prophylactic mefloquine use in patients with major psychiatric disorders and are

further cautioned that if psychiatric or neurologic symptoms arise while the drug is

being used prophylactically, it should be replaced with another medication.

Pharmacologic treatment in pregnancy

Medications that can be used for the treatment of malaria in pregnancy include

chloroquine, quinine, atovaquone-proguanil, clindamycin, mefloquine (avoid in first

trimester), sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (avoid in first trimester) and the artemisinins

(see below). Briand et al compared the efficacy and safety of sulfadoxinepyrimethamine to mefloquine for intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy.

In their study, 1601 women of all gravidities received either sulfadoxinepyrimethamine (1500 mg of sulfadoxine and 75 mg of pyrimethamine) or mefloquine

(15 mg/kg) in a single dose twice during pregnancy. There was a small advantage for

mefloquine in terms of efficacy, although the incidence of side effects was higher with

23/05/2016 22:59

Malaria Treatment & Management: Approach Considerations, Pharmac...

3 of 5

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/221134-treatment#showall

mefloquine than with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine.[32, 33]

In addition to mefloquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, other medications have

been used in the treatment of the pregnant patient with malaria. In a recent study in

African patients, artemether-lumefantrine was as efficacious and as well tolerated as

oral quinine in treating uncomplicated falciparum malaria during the second and third

trimesters of pregnancy.[1]

Artesunate and other antimalarials also appear to be effective and safe in the first

trimester of pregnancy, when development of malaria carries a high risk of

miscarriage.[2]

Inpatient Care

Patients with elevated parasitemia (>5% of RBCs infected), CNS infection, or

otherwise severe symptoms and those with P falciparum infection should be

considered for inpatient treatment to ensure that medicines are tolerated.

Obtain blood smears every day to demonstrate a response to treatment. The sexual

stage of the protozoan, the gametocyte, does not respond to most standard

medications (eg, chloroquine, quinine), but gametocytes eventually die and do not

pose a threat to the individual's health or cause any symptoms.

Deterrence and Prevention

Avoid mosquitoes by limiting exposure during times of typical blood meals (ie, dawn,

dusk). Wearing long-sleeved clothing and using insect repellants may also prevent

infection. Avoid wearing perfumes and colognes.

Adult-dose 95% DEET lasts up to 10-12 hours, and 35% DEET lasts 4-6 hours. In

children, use concentrations of less than 35% DEET. Use sparingly and only on

exposed skin. Remove DEET when the skin is no longer exposed to potential

mosquito bite. Consider using bed nets that are treated with permethrin. While this is

an effective method for prevention of malaria transmission in endemic areas, an

increasing incidence of pyretrhoid resistance in Anopheles spp has been

reported.[34] Seek out medical attention immediately upon contracting any tropical

fever or flulike illness.

Consider chemoprophylaxis with antimalarials in patients traveling to endemic areas.

Chemoprophylaxis is available in many different forms. The drug of choice is

determined by the destination of the traveler and any medical conditions the traveler

may have that contraindicate the use of a specific drug.

Before traveling, people should consult their physician and the Malaria and Traveler's

Web site of the CDC to determine the most appropriate chemoprophylaxis.[35] Travel

Medicine clinics are also a useful source of information and advice.

Investigational malaria vaccine

Malaria vaccine production and distribution continues to be in the research and

development stage.[24, 25, 26] In 2015, European Union (EU) regulators approved the

world's first malaria vaccine for use outside the EU among children aged 6 weeks to

17 months. The new vaccine (Mosquirix, GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals), which includes

a vaccine for hepatitis B, is awaiting review by the World Health Organization (WHO).

The earliest any malaria-endemic country could license the product is 2017,

according to WHO. Mosquirix targets P falciparum. It limits the parasite's ability to

infect, mature, and multiply in the liver.[27]

Interim phase 3 trial results were reported in 2011 for the malaria vaccine

RTS,S/AS01. The results included 6000 African children aged 5-17 months who

received the malaria vaccine or a comparator vaccine and were followed for 12

months. The incidence of malaria was 0.44 case per person-year in the RTS,S/AS01

group, compared with 0.83 case per person-year in the comparator vaccine group.

The vaccine efficacy rate was calculated to be 55.8%.[36, 37]

Consultations

Consider consulting an infectious disease specialist for assistance with malaria

diagnosis, treatment, and disease management. The CDC is an excellent resource if

no local resources are available. To obtain the latest recommendations for malaria

prophylaxis and treatment from the CDC, call the CDC Malaria Hotline at (770)

488-7788 or (855) 856-4713 (M-F, 9 am-5 pm, Eastern time). For emergency

consultation after hours, call (770) 488-7100 and ask to talk with a CDC Malaria

Branch clinician.[38]

Pregnant patients with malaria are at increased risk of morbidity and mortality.[39] In

addition, nonimmune mothers and immune primigravidas may be at an increased risk

of low birth weight, fetal loss, and prematurity. Consult an expert in malaria to

determine the safest and most effective prophylaxis or treatment in a pregnant

woman.

Medication

Contributor Information and Disclosures

Author

Thomas E Herchline, MD Professor of Medicine, Wright State University, Boonshoft School of Medicine; Medical

Director, Public Health, Dayton and Montgomery County, Ohio

Thomas E Herchline, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, Infectious Diseases

Society of Ohio, Infectious Diseases Society of America

23/05/2016 22:59

Malaria Treatment & Management: Approach Considerations, Pharmac...

4 of 5

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/221134-treatment#showall

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chief Editor

Michael Stuart Bronze, MD David Ross Boyd Professor and Chairman, Department of Medicine, Stewart G Wolf

Endowed Chair in Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Oklahoma Health Science Center;

Master of the American College of Physicians; Fellow, Infectious Diseases Society of America

Michael Stuart Bronze, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American Medical

Association, Oklahoma State Medical Association, Southern Society for Clinical Investigation, Association of

Professors of Medicine, American College of Physicians, Infectious Diseases Society of America

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Additional Contributors

Emilio V Perez-Jorge, MD, FACP Staff Physician, Division of Infectious Diseases, Lexington Medical Center

Emilio V Perez-Jorge, MD, FACP is a member of the following medical societies: American College of PhysiciansAmerican Society of Internal Medicine, Infectious Diseases Society of America, Society for Healthcare

Epidemiology of America, South Carolina Infectious Diseases Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Michael Stuart Bronze, MD Professor, Stewart G Wolf Chair in Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine,

University of Oklahoma Health Science Center

Michael Stuart Bronze, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American College

of Physicians, American Medical Association, Association of Professors of Medicine, Infectious Diseases Society

of America, Oklahoma State Medical Association, and Southern Society for Clinical Investigation

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Joseph Richard Masci, MD Professor of Medicine, Professor of Preventive Medicine, Mount Sinai School of

Medicine; Director of Medicine, Elmhurst Hospital Center

Joseph Richard Masci, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American College

of Physicians, Association of Professors of Medicine, and Royal Society of Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College

of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Medscape Salary Employment

References

1. Piola P, Nabasumba C, Turyakira E, et al. Efficacy and safety of artemether-lumefantrine compared with

quinine in pregnant women with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria: an open-label, randomised,

non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010 Nov. 10(11):762-9. [Medline].

2. McGready R, Lee SJ, Wiladphaingern J, et al. Adverse effects of falciparum and vivax malaria and the safety

of antimalarial treatment in early pregnancy: a population-based study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012 May. 12

(5):388-96. [Medline].

3. Cox-Singh J, Davis TM, Lee KS, et al. Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in humans is widely distributed and

potentially life threatening. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Jan 15. 46(2):165-71. [Medline]. [Full Text].

4. Marchand RP, Culleton R, Maeno Y, Quang NT, Nakazawa S. Co-infections of Plasmodium knowlesi, P.

falciparum, and P. vivax among Humans and Anopheles dirus Mosquitoes, Southern Vietnam. Emerg Infect

Dis. 2011 Jul. 17(7):1232-9. [Medline].

5. William T, Menon J, Rajahram G, et al. Severe Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in a tertiary care hospital, Sabah,

Malaysia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011 Jul. 17(7):1248-55. [Medline].

6. Malaria Surveillance United States, 2010. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at

http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss6102a1.htm?s_cid=ss6102a1_e. Accessed: March 1, 2012.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Malaria. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/malaria. Accessed: Sep

15, 2011.

8. Taylor SM, Parobek CM, Fairhurst RM. Haemoglobinopathies and the clinical epidemiology of malaria: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012 Jun. 12 (6):457-68. [Medline].

9. [Guideline] Bailey JW, Williams J, Bain BJ, Parker-Williams J, Chiodini P. General Haematology Task Force.

Guideline for laboratory diagnosis of malaria. London (UK): British Committee for Standards in Haematology.

2007;19. [Full Text].

10. Bailey JW, Williams J, Bain BJ, et al. Guideline: the laboratory diagnosis of malaria. General Haematology

Task Force of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Br J Haematol. 2013 Dec. 163

(5):573-80. [Medline].

11. Rapid diagnostic tests for malaria ---Haiti, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010 Oct 29.

59(42):1372-3. [Medline].

12. Wongsrichanalai C, Barcus MJ, Muth S, Sutamihardja A, Wernsdorfer WH. A review of malaria diagnostic

tools: microscopy and rapid diagnostic test (RDT). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007 Dec. 77(6 Suppl):119-27.

[Medline].

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notice to Readers: Malaria Rapid Diagnostic Test. Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5627a4.htm.

Accessed: September 30, 2011.

14. de Oliveira AM, Skarbinski J, Ouma PO, et al. Performance of malaria rapid diagnostic tests as part of routine

malaria case management in Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009 Mar. 80(3):470-4. [Medline].

15. Polley SD, Gonzalez IJ, Mohamed D, et al. Clinical evaluation of a loop-mediated amplification kit for

diagnosis of imported malaria. J Infect Dis. 2013 Aug. 208(4):637-44. [Medline]. [Full Text].

23/05/2016 22:59

Malaria Treatment & Management: Approach Considerations, Pharmac...

5 of 5

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/221134-treatment#showall

16. d'Acremont V, Malila A, Swai N, et al. Withholding antimalarials in febrile children who have a negative result

for a rapid diagnostic test. Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Sep 1. 51(5):506-11. [Medline].

17. Mens P, Spieker N, Omar S, Heijnen M, Schallig H, Kager PA. Is molecular biology the best alternative for

diagnosis of malaria to microscopy? A comparison between microscopy, antigen detection and molecular

tests in rural Kenya and urban Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health. 2007 Feb. 12(2):238-44. [Medline].

18. Dondorp AM, Fanello CI, Hendriksen IC, et al. Artesunate versus quinine in the treatment of severe

falciparum malaria in African children (AQUAMAT): an open-label, randomised trial. Lancet. 2010 Nov 13.

376(9753):1647-57. [Medline]. [Full Text].

19. Sinclair D, Donegan S, Isba R, Lalloo DG. Artesunate versus quinine for treating severe malaria. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev. 2012 Jun 13. 6:CD005967. [Medline].

20. US Food and Drug Administration FDA Approves Coartem Tablets to Treat Malaria. FDA. Available at

http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm149559.htm. Accessed: April 8, 2009.

21. Teuscher F, Gatton ML, Chen N, Peters J, Kyle DE, Cheng Q. Artemisinin-induced dormancy in plasmodium

falciparum: duration, recovery rates, and implications in treatment failure. J Infect Dis. 2010 Nov 1.

202(9):1362-8. [Medline]. [Full Text].

22. Tozan Y, Klein EY, Darley S, Panicker R, Laxminarayan R, Breman JG. Prereferral rectal artesunate for

treatment of severe childhood malaria: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet. 2010 Dec 4.

376(9756):1910-5. [Medline].

23. Amaratunga C, Sreng S, Suon S, et al. Artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in Pursat province,

western Cambodia: a parasite clearance rate study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012 Nov. 12(11):851-8. [Medline].

24. Othoro C, Johnston D, Lee R, Soverow J, Bystryn JC, Nardin E. Enhanced immunogenicity of Plasmodium

falciparum peptide vaccines using a topical adjuvant containing a potent synthetic Toll-like receptor 7 agonist,

imiquimod. Infect Immun. 2009 Feb. 77(2):739-48. [Medline]. [Full Text].

25. Richards JS, Stanisic DI, Fowkes FJ, et al. Association between naturally acquired antibodies to erythrocytebinding antigens of Plasmodium falciparum and protection from malaria and high-density parasitemia. Clin

Infect Dis. 2010 Oct 15. 51(8):e50-60. [Medline].

26. Olotu A, Lusingu J, Leach A, et al. Efficacy of RTS,S/AS01E malaria vaccine and exploratory analysis on

anti-circumsporozoite antibody titres and protection in children aged 5-17 months in Kenya and Tanzania: a

randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011 Feb. 11(2):102-9. [Medline].

27. First Malaria Vaccine Approved by EU Regulators. Medscape Medical News. Available at

http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/848608. July 24, 2015;

28. Janeczko LL. Primaquine protects against P. vivax malaria relapse. Medscape Medical News. Jan 3, 2013.

Available at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/777109. Accessed: Jan 16, 2013.

29. Sutanto I, Tjahjono B, Basri H, et al. Randomized, open-label trial of primaquine against vivax malaria relapse

in Indonesia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013 Mar. 57 (3):1128-35. [Medline].

30. Lowes R. FDA Strengthens Warning on Mefloquine Risks. Medscape Medical News. Jul 29 2013. [Full

Text].

31. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA approves label changes for

antimalarial drug mefloquine hydrochloride due to risk of serious psychiatric and nerve side effects. FDA.

Available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/UCM362232.pdf. Accessed: Aug 6 2013.

32. Briand V, Bottero J, Noel H, et al. Intermittent treatment for the prevention of malaria during pregnancy in

Benin: a randomized, open-label equivalence trial comparing sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine with mefloquine. J

Infect Dis. 2009 Sep 15. 200(6):991-1001. [Medline].

33. Briand V, Cottrell G, Massougbodji A, Cot M. Intermittent preventive treatment for the prevention of malaria

during pregnancy in high transmission areas. Malar J. 2007 Dec 4. 6:160. [Medline]. [Full Text].

34. Trape JF, Tall A, Diagne N, et al. Malaria morbidity and pyrethroid resistance after the introduction of

insecticide-treated bednets and artemisinin-based combination therapies: a longitudinal study. Lancet Infect

Dis. 2011 Dec. 11(12):925-32. [Medline].

35. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA: DHHS; 2009. Malaria and Travelers. Available at

http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/travelers/index.html. Accessed: Sep 15, 2011.

36. The RTS,S Clinical Trials Partnership. First results of phase 3 trial of RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine in African

children. N Engl J Med. 2011/Oct. 365:[Full Text].

37. White NJ. A vaccine for malaria (editorial). N Engl J Med. 2011/Oct. 365:[Full Text].

38. [Guideline] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Malaria Diagnosis and Treatment in the United

States. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/diagnosis_treatment/index.html. Accessed: Sep 15, 2011.

39. Poespoprodjo JR, Fobia W, Kenangalem E, et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes in an area where multidrugresistant plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum infections are endemic. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 May 1.

46(9):1374-81. [Medline]. [Full Text].

Medscape Reference 2011 WebMD, LLC

23/05/2016 22:59

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Diagnostic Effectiveness of All Test Hbsag Rapid Test Kit Compared With Elisa SerologyDokumen3 halamanDiagnostic Effectiveness of All Test Hbsag Rapid Test Kit Compared With Elisa SerologyHas SimBelum ada peringkat

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Gangguan Elminasi Pada Ibu HamilDokumen10 halamanGangguan Elminasi Pada Ibu HamilRismawatiBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- ViroDokumen139 halamanViroXyprus Darina VeloriaBelum ada peringkat

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Introduction: What Is Hiv and Aids?Dokumen6 halamanIntroduction: What Is Hiv and Aids?Hasib AhmedBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- CHN Ii ... Aparna Roll No. 12Dokumen17 halamanCHN Ii ... Aparna Roll No. 12Aparna PandeyBelum ada peringkat

- Typhoid Fever: By, Arathy DarvinDokumen35 halamanTyphoid Fever: By, Arathy DarvinJaina JoseBelum ada peringkat

- SparganosisDokumen21 halamanSparganosisJose Ho100% (1)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Auburn University BIOL 5200 Final ReviewDokumen18 halamanAuburn University BIOL 5200 Final ReviewClaudia Ann RutlandBelum ada peringkat

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- D.sexual Worker's Occupation Sanitation ProgramDokumen6 halamanD.sexual Worker's Occupation Sanitation ProgramJoms MinaBelum ada peringkat

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Communicable Disease PresentationDokumen67 halamanCommunicable Disease PresentationMonaBelum ada peringkat

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Bacterial GastroenteritisDokumen4 halamanBacterial GastroenteritisMarra Camille Celestial RNBelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Case Study 2011Dokumen11 halamanCase Study 2011geetishaBelum ada peringkat

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Daftar Pustaka: Dermatology, 2Dokumen3 halamanDaftar Pustaka: Dermatology, 2Kusmantoro HidayatBelum ada peringkat

- Blood Typing LabDokumen5 halamanBlood Typing LabRoderick Malinao50% (2)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Meningitis MedscapeDokumen73 halamanMeningitis MedscapeBujangBelum ada peringkat

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Dengue AwarenessDokumen25 halamanDengue AwarenessAsorihm MhirosaBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- Lecture PP17&18 ClostridiumDokumen61 halamanLecture PP17&18 Clostridiumvn_ny84bio021666100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- ID4013 - SPW103 - Assessment - 2 - Response Template - 230321 2Dokumen20 halamanID4013 - SPW103 - Assessment - 2 - Response Template - 230321 2SUCHETA DASBelum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- List of OIE DiseasesDokumen5 halamanList of OIE DiseasesShiva KhanalBelum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Staphylococci 18 StudentDokumen42 halamanStaphylococci 18 StudentJulia MartinezBelum ada peringkat

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Quiz (4 Mei - 7 Mei)Dokumen3 halamanQuiz (4 Mei - 7 Mei)NdyBelum ada peringkat

- Vibrio CholeraeDokumen12 halamanVibrio Choleraedorothy kageniBelum ada peringkat

- UNCC300 Assesment TAsk 2Dokumen2 halamanUNCC300 Assesment TAsk 2Spandan DahalBelum ada peringkat

- Pathogenesis of InfectionDokumen8 halamanPathogenesis of InfectionCardion Rayon Bali UIN MalangBelum ada peringkat

- MRSA What To KnowDokumen3 halamanMRSA What To KnowFara LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Essay Article On Consumer Awareness Towards Food SafetyDokumen4 halamanEssay Article On Consumer Awareness Towards Food SafetyMohd Faizal Bin AyobBelum ada peringkat

- Nematode TableDokumen16 halamanNematode TableJackie Lind TalosigBelum ada peringkat

- Dna VirusesDokumen9 halamanDna VirusesdokutahBelum ada peringkat

- Genital WartsDokumen3 halamanGenital WartsNathalia MahabirBelum ada peringkat

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Lepto Clinical Management GLEAN 2019 - M GasemDokumen42 halamanLepto Clinical Management GLEAN 2019 - M GasemSelfie C RijalBelum ada peringkat

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)