Weaving As An Analogy For Architectural Design

Diunggah oleh

AndriantoDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Weaving As An Analogy For Architectural Design

Diunggah oleh

AndriantoHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Weaving As An Analogy for Architectural Design

1 of 11

http://faculty.philau.edu/griffenc/weaving_analogy.htm

Click Here For Abstract

Premise

As professionals become increasingly specialized, architects must continue to operate as

generalists. Although more specialized today, their breadth of required knowledge is still

widespread and expanding. It must range in scale from the macro of global environmental

issues to the micro of soil geology. It spreads across disciplines from the subjective realm of

aesthetics to the objective sciences. While an expert in none, an architect must draw from such

diverse disciplines of anthropology, art, business, construction, ecology, engineering, geology,

history, law, physics, psychology, sociology, and so on. But how does an architect retain and

process all this information? To architects these are not separate fields existing on their own.

Rather, I propose, each is a thread in a complex matrix of information from which they must

glean and weave together the strands relevant to each project.

Weaving, as a practiced craft, has been a common cross-cultural phenomenon for

thousands of years. While patterns and techniques differ between cultures, the basic craft of

weaving can be found in most. Because the concept of weaving is so accessible, it is often

used as an analogy to describe various systems in our world. It describes fabrics of different

races, religions, beliefs and values all co-existing. It is used as an analogy for the natural world

to explain the delicate web of climates, plants, animals and organisms that depend on each

other. In terms of sociology we read about the urban fabric with its interweaving of people,

neighborhoods, homes, work places and institutions. It is an apt analogy for how systems

overlap and work together to create a harmonious living environment, as well as the possible

destruction caused by the breaking of a single element or strand in the fabric. The fact that we

exist as individual members of a cohesive team also applies directly to the building industry. A

5/21/2012 1:58 PM

Weaving As An Analogy for Architectural Design

2 of 11

http://faculty.philau.edu/griffenc/weaving_analogy.htm

look at the range of trades composing any building design team will clearly demonstrate this.

Architects, as generalists, have traditionally occupied the role of supervisor for a building

project. They are responsible for coordinating and 'interweaving' the interests of the related

consultants, owners, occupants and contractors to produce a meaningful work of architecture.

By investigating the similarities between weaving and architecture we begin to see

overlapping concepts. Architects and weavers both recognize the need to look beyond surface

appearances in the process of designing. In the same way architects realize that quality design

is more than skin deep, weavers understand the quality of a textile is dependent on the

structure of the weave and not just the visual appearance of its fibers. As Anni Albers, a weaver

from the Bauhaus, revealingly states:

Surface quality of material, that is matire, being mainly a quality of

appearance, is an aesthetic quality and therefore a medium of the artist; while

quality of inner structure is, above all, a matter of function and therefore the

concern of the scientist and engineer. Sometimes material surface together with

material structure are the main components of a work; in textile works for

instance, specifically in weavings or, on another scale, in works of

architecture1.

In their common need to relate a design's physical properties to its aesthetic

implications, weaving and architecture share a trait worthy of further exploration

The history of textile use in architecture is broad. The most visible form of woven

material today is tensile membrane structures. However, rather than concentrating on a single

physical material, I chose to focus on the process of weaving as an instructional analogy in the

design process. For example, in architectural design this analogy can inform the interlacing of

ideas, people, place, space and construction. The comparing of weaving and architectural

design from the analogical/conceptual viewpoint constitutes the basic premise of this paper.

Woven Construction

5/21/2012 1:58 PM

Weaving As An Analogy for Architectural Design

3 of 11

http://faculty.philau.edu/griffenc/weaving_analogy.htm

Before applying the weaving analogy to abstract notions of space or culture, it is helpful to first

understand the history of physical woven construction. In terms of architecture, weaving in its

fabric form has been used in tent structures for thousands of years. However, the history of

planar wall construction also has weaving in its roots as the earliest building walls were likely

woven. In 1851, Gottfried Semper published his well-known theory of the Four Elements of

Architecture. Basing his theory on the form of the primitive hut, he categorized its

construction into four basic elements of Hearth, Roof, Mound and Fence.2 For the last of

these, the Fence, he proposed that the walls of ancient houses were not made of stone but

rather of hanging cloth or woven 'mats', thus suggesting the idea of the wall as a textile hung

off of the supporting structure, similar to the curtain wall today. (Semper further proposed the

knot as the oldest tectonic form of the joint based upon similar German roots of the two

words.3) To construct these walls, branches and grasses of differing sizes were interlaced to

form a supportive structure that in colder climates was covered with a weather resistant shell of

mud and/or leaves. Without this additional protective layer the cold and damp climate would be

allowed to penetrate. This type of construction, generally known as waddle and daub, was

common up to about a hundred years ago with the woven support always hidden. Even our

closest modern relative to the woven wall, plaster on lath, has been generally replaced by

gypsum board construction. The permeable nature of the exterior woven wall is a major reason

why we do not see more buildings utilizing this technique. They are best adapted to tropical

climates where the temperature is relatively constant and airflow is encouraged. However if we

expand the analogy of the woven wall to conceptual level it allows for the inclusion of solid

wall construction. For example, Frank Lloyd Wright developed a system of custom concrete

blocks interwoven within a metal reinforcing mesh into a double-layered wall. In this form the

thin walls could retain the solidity of concrete while providing the flexibility of fabric to be

shaped into any form.4 Even traditional masonry construction when bonded with mortar in

overlapping coursework can be considered a form of weaving.

The advent of new materials and joining methods has shifted the focus of construction

away from what Kenneth Frampton calls wet techniques such as masonry. 5 The current

trend of de-materializing glass walls into separate dry systems of structure, enclosure and

shading/climate control opens up new opportunities to appropriate the woven wall. The desire

to admit an abundance of light without excessive overheating or ultraviolet damage creates one

role for woven screens as shading devices. When combined with a sealed envelope they make

an effective system against the elements in exterior walls. They can also be extremely effective

as vision screens to increase privacy or hide undesirable views. The future of woven wall

construction looks promising in light of the proliferation of curviplanar forms in building

design today. While our current construction systems are not well suited for complex shapes

and stresses, a new material has yet to emerge. However there is research being done on

various solutions. One relevant example can be found in the research of Doug Garafalo who is

investigating the potential of a stainless steel mesh to realize structural curved shapes. "The

mesh behaves like a fabric that can curve in all directions but it does have structure and can act

5/21/2012 1:58 PM

Weaving As An Analogy for Architectural Design

4 of 11

http://faculty.philau.edu/griffenc/weaving_analogy.htm

and react according to the forces applied - it's a weave that can handle torque."6 The way we

approach construction is changing and woven construction could play a major role.

Weaving Analogy as Instructional Device

Literal woven construction is only on example of the overlaps between architecture and

weaving. The weaving analogy can also be used as an instructional technique as I do in my

architecture design studio. The impetus for the technique arose through the prominence of the

textile school in our university. Our college was originally established as a textile school so

we have been trying to find ways to relate architecture to textiles. Previous collaborations with

the school have dealt with the production of fabric structures. However, I wanted to engage its

people and facilities to investigate how the two disciplines also share other ideas about

construction and form, specifically through the process of weaving. Architecture students see

what is involved in the production of woven structures and textile students see the possibilities

of weaving with non-fibrous materials. The studio follows one program throughout the

semester divided into three topics of weaving and architecture that range from the literal to the

theoretical. Though the studio course requires a linear format, the analogy excels as a reminder

that design is a non-linear process that requires constant re-evaluation of site, program and

construction throughout a project. The weaving model, in its capacity to intertwine varying

elements and patterns, demonstrates the need to consider the many possible combinations of

major and minor influences on the design. Following are the descriptions of how each project

employed the weaving analogy.

The Structure of Weaving

As students typically have had little experience with the process of weaving, the first project

introduces them to the basic patterns and techniques involved. In this phase they work directly

with members of the textile school. A general goal of this design studio is to examine how

5/21/2012 1:58 PM

Weaving As An Analogy for Architectural Design

5 of 11

http://faculty.philau.edu/griffenc/weaving_analogy.htm

materials and methods of construction influence and direct the design process. Weaving

provides an excellent example of how materials and patterns of weaving have a critical

influence on the outcome of the fabric. The specific goal of the project is to study the

characteristics of actual weaving through the empirical, hands-on making of an object at

full-size. Weaving a textile by hand reveals much about the tactile qualities of the materials not

evident by sight. In the same way, creating a piece of architectural construction by hand reveals

qualities of the materials not evident in representational drawings. Architects have become

separated from the tactile experience of construction. Our materials come to us already ground

and chipped and crushed and powdered and mixed and sliced, so that only the finale in the

long sequence of operations from matter to product is left to us; we merely toast the bread.7

Both architecture and weaving students need to understand the physical properties of materials

that they normally represent by electronic pixels on a screen. To test this idea, students divide

up into groups which are each assigned a weaving student to act as an advisor. They must then

design and build at full-scale a woven wall structure. To introduce them to the craft of weaving

they tour the textile schools weaving facilities to watch both hand and power looms in action.

They see first hand how the process of production and the structure of the weaving inform the

final appearance; how plain, twill, satin or tri-axial patterns produce varying results.

Professors from the textile school act as consultants and reviewers for the architects as they

design their screens.

Instead of only using typical fibrous materials, they are required to mainly use materials

associated with building construction such as wood, metal and plastic. This places the project

in-between the realms of architecture and textiles (more akin to basket weaving) which means

neither the architect nor the weaver is an expert but both can contribute equally.

5/21/2012 1:58 PM

Weaving As An Analogy for Architectural Design

6 of 11

http://faculty.philau.edu/griffenc/weaving_analogy.htm

While students utilized basic layout drawings to confirm overall dimensions, many of the

design decisions were made during construction by adapting available hardware and materials

to meet their intentions. Properties of the materials dictated many of the decisions. For

example, many materials proved to be too stiff for weaving and had to be replaced. The project

required at least one of the materials to be metal so for most of the students it was their first

hands-on experience with cutting, drilling and welding steel, copper or aluminum. The

empirical knowledge about the properties of metal gained by physically working it can not be

matched by representational means. Through trial and error they learn how an initial concept

can change over time as issues of real construction influence and affect revisions in the design.

They understand how materials used for weaving are critically dependent on the manner in

which they are assembled.

Weaving an Idea; Context, Culture and Construction

This is the first part of the major building design project where students utilize concepts of

weaving to analyze how the site, program and materiality are inextricably intertwined in the

design of architecture. It is generally accepted the orthogonal geometry of American city plans

originally derived from Greek city grids. However, these may have been derived from the

structure of woven cloth. The tightly woven, right-angled patterns of cloth were seen as

harmonious by the Greeks. This pattern may have been applied to the colonial cities as a

5/21/2012 1:58 PM

Weaving As An Analogy for Architectural Design

7 of 11

http://faculty.philau.edu/griffenc/weaving_analogy.htm

way to create a harmonious and recognizable living environment in a foreign and hostile

land. 8 As mentioned previously, there are many diverse influences that shape an urban fabric.

While the physical objects such as buildings and streets are more obvious, invisible

psychological and social factors often have great influence. Students investigate the various

patterns of their urban site to seek out weaving analogies, analyze the contextual factors that

influence a site and thereby determine a site design strategy. The location for the project is

chosen in a prominent area of the city where the urban fabric has become unraveled and lost

its sense of an urban place. The students must investigate its history, analyze the various

factors that remain and propose a way to re-stitch their site to the fabric of the city through

circulation patterns, built-form, and landscape design. Three groups each present an analysis of

either the environmental, social or legal influences on the context. Each presentation is

constructed in a transparent medium and interlaced with the others to present a collective

analysis. Time constraints limit the study of the urban fabric analogy to the immediate

context. However this exercise provides an introduction to the way in which external factors

impending on a site must be balanced and interwoven to recreate a harmonious urban

environment.

The broad range of information derived from analysis of site and program demonstrates the

need for a strategy to integrate all the influences of a design. The weaving analogy is presented

as a unique method to integrate the "Three Cs" of a design: Context, Culture and

Construction. Context, as previously examined, refers to all the climatic, social/cultural, legal

and especially intuitive aspects of a site. Culture refers to the human behavioral aspects of a

project such as the functions of the program as per occupant needs, the history of its people,

and local traditions as a source of regional identity. Construction encompasses the basic

concepts for the materials, structure, assemblies and services of physical building that

influence the direction of initial design ideas. Having just examined the context, students now

concentrate on programmatic aspects to determine not only the relationships of spaces but also,

more importantly, how the building can meet the diverse needs of the people who will use it.

While the Construction aspect will be scrutinized in the next phase, students now develop a

5/21/2012 1:58 PM

Weaving As An Analogy for Architectural Design

8 of 11

http://faculty.philau.edu/griffenc/weaving_analogy.htm

basic tectonic concept from the possible materials and structure allowed by legal code

constraints and spatial requirements of the program. By sorting through these jumbled

threads, they begin to organize priorities en route to developing a design concept. Just as

woven cloth has major and minor threads and patterns, the students will compose a conceptual

textile of ideas to integrate the various influences. The weaving analogy performs as an

instructional vehicle for describing the non-linear design process.

The concept is then expanded into three-dimensional spaces that reveal the interwoven

experience of architectural space and construction. They examine the overlap of light and

shadow, solid and void, all within the aspect of movement in time. As Steven Holl states:

When we move through space with a twist and turn of the head, mysteries of gradually

unfolding fields of overlapping perspectives are changed with a range of light-from the steep

shadows of bright sun to the translucence of dusk. 9 Students need to understand a space is

not static but made up of multiple layers that continually changing as one moves around and

through it, something rarely evident in orthographic drawings. They study complex interior

spatial conditions by first establishing hierarchies between public and private, service and

served space, vertical and horizontal circulation, bearing and non-bearing construction, as well

as how they overlap, parallel and penetrate each other. Space is approached as a threedimensional cloth pulled apart to reveal changing sizes, shapes and rhythms of space and

structure.

Interweaving Construction

This phase centers on the constructive aspects of their design. With the advent of the iron

frame in the mid-nineteenth century, the enclosing walls of buildings began separating into

distinct structural, envelope and service systems. In 1852 Joseph Paxton gave a speech to

explain the structural principle behind his "Crystal Palace." In it he compared the iron

structural frame and the enclosing glass envelope to a "table and tablecloth". By this

description he wanted to represent the glass skin as a tablecloth separate from the structure

(table) that would now allow it to be "greatly varied to suit changing conditions and uses".10

Kenneth Frampton employs R. Gregory Turners study, Construction Economics and Building

Design to further describe the shift away from the monolithic masonry wall toward a division

into his categories of podium, services, framework, and envelope. In terms of percentage of

construction cost, the structure has been reduced while services and envelope now make up the

majority of the expense.11 The simple bearing wall building has become rare. Instead it has

been divided into separate systems providing support, comfort and convenience which, while

allowing greater freedom for design, also create an abundance of information to coordinate.

5/21/2012 1:58 PM

Weaving As An Analogy for Architectural Design

9 of 11

http://faculty.philau.edu/griffenc/weaving_analogy.htm

Students first study the structural system in a manner that also reveals the qualities of the space

inside. Too often models present the external form of a building without revealing the critical

space inside. Therefore, students make a physical model of the structural system with templates

created from current floor plans that can be mounted to board and woven together with

threaded rod columns and basswood bearing walls. By allowing the student to see inside

the building, these "woven" study models reveal spatial and structural issues not always evident

on computer or physical massing models. Threaded rods also allow for quick revisions by

adjusting the nuts up or down and replacing floor plates to create new spatial conditions. As

mentioned earlier, in both textiles and architecture, the inner structure plays an integral role in

the overall form. Thereby through this exercise, students now begin to see the overlaps evident

in the spatial, organizational, and especially the structural systems of a building. To

understand how enclosure systems affect their design, students now study the envelope in

detail. They first complete their structural model by clothing it in an envelope of transparent,

translucent or opaque cladding to convey their design intentions and thus adding another

element to the weave. The skin is detailed by studying a portion of the enclosure critical to the

concept and developing it at a larger scale in partial section, plan and elevation. Typically this

is a wall section that depicts an important relationship between the structure, services, envelope

and shading systems to demonstrate how they must coexist within a thin slice of space. They

develop the wall section by selecting the specific materials and systems required to create

assembly details. While students may desire an unbroken wall of glass, they must first address

the complicated issues of supporting, shading, fire rating and heating it. The goal of this

exercise is to demonstrate how all the physical components concentrated at the perimeter of a

building must be interwoven to allow each to function efficiently while still reinforcing the

design concept.

For a textile to exist as a cohesive work, all the individual yarns and varying patterns must be

bound together in a synergistic and integrated whole. Similarly in architecture, all the

5/21/2012 1:58 PM

Weaving As An Analogy for Architectural Design

10 of 11

http://faculty.philau.edu/griffenc/weaving_analogy.htm

influences on the design must ultimately coalesce into a final product. Therefore for the final

project of the course, a digital, compositional drawing is created that integrates the wall section

with the most critical building design drawings into one interwoven layout similar to an

analytique. Relevant plans, sections, elevations and three-dimensional drawings are interlaced

with construction details in a drawing summarizing the design. Students take advantage of

CADs flexibility to overlay drawings of different scales and views and 'weave' them together

by an appropriate graphic technique. This drawing becomes a comprehensive tapestry of the

entire semester-long project in one technically precise document.

Conclusion

By the end of the semester students have studied the analogy of weaving in architecture from

the hands-on to the virtual. After going through all phases, they can draw associations between

themselves, their work and the larger world. To improve this course, the first objective would

be greater involvement fore the weavers. Although they served well as advisors, the new palette

of materials acted physically opposite of what they expected which deterred them from deeper

involvement. The next step would be to improve the presentation of the figurative analogy.

The students had more success understanding the weaving analogy through the literal projects

such as the woven wall, the threaded rod model and the technical wall section drawings.

Finding better ways for them to understand the abstract notion of weaving an idea or space

could be further developed.

Whether used in this particular studio format or in a general studio, the weaving analogy

has relevant application to architectural design. Students are always searching for a way to

make sense of all the information they acquire in college. Beyond studio, they receive

indoctrination in professional courses on structures, building construction, environmental

5/21/2012 1:58 PM

Weaving As An Analogy for Architectural Design

11 of 11

http://faculty.philau.edu/griffenc/weaving_analogy.htm

systems, history, and professional management that can be applied to their design projects. Yet

they often question the need for their liberal arts courses that reveal little evident application to

their main area of study; design studio. Weaving, as an analogy, is a useful tool for explaining

the benefits, indeed the necessity, of a wide range of knowledge. Architects must continue to

operate as generalists to acquire a multitude of ideas that someday may be retrieved and woven

into another tapestry of architectural design.

Notes

1

Anni Albers , On Weaving (Middletown Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 1965

Wolfgang Herrmann, Gottfried Semper: In Search of Architecture, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1984)

Kenneth Frampton, Studies in Tectonic Culture; The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century

Architecture, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1995)

4

Frampton, 1995

Kenneth Frampton (Editor), Technology, Place and Architecture, The Jerusalem Seminar in Architecture, (New York:

Rizzoli, 1998)

6

Joseph Giovanni, "Building a Better Blob", Architecture, September 2000

7

Albers

Indra Kagis McEwen, Socrates Ancestor, An Essay on Architectural Beginnings, (London :The MIT Press, 1993)

Steven Holl, Intertwining, (Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 1995)

10

Herrmann

11

Frampton, 1998

5/21/2012 1:58 PM

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Imagining Modernity: The Architecture of Valentine GunasekaraDari EverandImagining Modernity: The Architecture of Valentine GunasekaraPenilaian: 1 dari 5 bintang1/5 (1)

- 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art: SanaaDokumen8 halaman21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art: SanaaEduardo Cesar GentileBelum ada peringkat

- BAUHAUS, 217s'14Dokumen217 halamanBAUHAUS, 217s'14Raluca GîlcăBelum ada peringkat

- Zeinstra Houses of The FutureDokumen12 halamanZeinstra Houses of The FutureFrancisco PereiraBelum ada peringkat

- Lefaivre - Everything Is ArchitectureDokumen5 halamanLefaivre - Everything Is ArchitectureBatakoja MeriBelum ada peringkat

- Fresh Kills Park LifescapeDokumen66 halamanFresh Kills Park Lifescapenyc100% (6)

- Remment Lucas KoolhaasDokumen42 halamanRemment Lucas KoolhaasKu Hasna ZuriaBelum ada peringkat

- Louis Kahn's Influence On Two Irish Architects Paul GovernDokumen24 halamanLouis Kahn's Influence On Two Irish Architects Paul Governpaulgovern11100% (1)

- Rem Koolhaas, From Surrealism To The Structuralist ActivityDokumen12 halamanRem Koolhaas, From Surrealism To The Structuralist ActivityEmil BurbeaBelum ada peringkat

- Khadi WeavingDokumen4 halamanKhadi WeavingJennifer McconnellBelum ada peringkat

- Architecture of Regionalism in The Age of Globalization Peaks and Valleys in The Flat World 9780415575782 0415575788Dokumen233 halamanArchitecture of Regionalism in The Age of Globalization Peaks and Valleys in The Flat World 9780415575782 0415575788Frenky AndrianBelum ada peringkat

- BauhausDokumen11 halamanBauhausveekshiBelum ada peringkat

- Hans Kollhoff Review of HousingDokumen30 halamanHans Kollhoff Review of HousingVIgnesh100% (2)

- Re-Scaling The Environment East West Central - Re-Building Europe, 1950-1990Dokumen318 halamanRe-Scaling The Environment East West Central - Re-Building Europe, 1950-1990Hachem YucefBelum ada peringkat

- 6602 REM Koolhaas EXTDokumen16 halaman6602 REM Koolhaas EXTAntony LondlianiBelum ada peringkat

- Kazuhiro KojimaDokumen6 halamanKazuhiro Kojimamo5tarBelum ada peringkat

- Columns - Walls - Floors 2013Dokumen176 halamanColumns - Walls - Floors 2013700spymaster007Belum ada peringkat

- 03 T Avermaete ARCHITECTURE TALKS BACK PDFDokumen12 halaman03 T Avermaete ARCHITECTURE TALKS BACK PDFsamilorBelum ada peringkat

- Energy The Tate Modern and BanksideDokumen84 halamanEnergy The Tate Modern and BanksidePatt LezBelum ada peringkat

- London Metropolitan University Summer Show 08 PDFDokumen43 halamanLondon Metropolitan University Summer Show 08 PDFLoana VulturBelum ada peringkat

- ZAHA HADID - PHAENO - Science Centre WolfburgDokumen9 halamanZAHA HADID - PHAENO - Science Centre WolfburgEmiliano_Di_Pl_3393Belum ada peringkat

- Parallax (Steven Holl)Dokumen368 halamanParallax (Steven Holl)Carvajal MesaBelum ada peringkat

- Colomina - Blurred Visions - X-Ray Architecture PDFDokumen22 halamanColomina - Blurred Visions - X-Ray Architecture PDFSilvia AlviteBelum ada peringkat

- Caruso 2012 Hs Work BookDokumen77 halamanCaruso 2012 Hs Work BookЕрнест ЛукачBelum ada peringkat

- Capability Brown - Landscape PDFDokumen94 halamanCapability Brown - Landscape PDFDushyantBelum ada peringkat

- CHIPERFIELDDokumen5 halamanCHIPERFIELDXtremeevilBelum ada peringkat

- How Has Peter Zumthor Responded To All of The Senses in His Building The Therme Vals 1Dokumen13 halamanHow Has Peter Zumthor Responded To All of The Senses in His Building The Therme Vals 1Hasan Jamal0% (1)

- FS21 Design Studio - Textile, ReaderDokumen92 halamanFS21 Design Studio - Textile, ReaderEdgarBritoBelum ada peringkat

- The Pritzker Architecture Prize - 1998. RENZO PIANO 2Dokumen33 halamanThe Pritzker Architecture Prize - 1998. RENZO PIANO 2wrath100% (1)

- T02 Essay Parasitic ArchitectureDokumen11 halamanT02 Essay Parasitic ArchitectureIoana SuceavaBelum ada peringkat

- Christo and Janne-Claude. Te Abu Dhabi Mastaba.Dokumen2 halamanChristo and Janne-Claude. Te Abu Dhabi Mastaba.spammagazineBelum ada peringkat

- Exodus, or The Voluntary Prisoners of ArchitectureDokumen23 halamanExodus, or The Voluntary Prisoners of ArchitectureMaja Merlic100% (1)

- PALSUN Flat Solid Polycarbonate SheetsDokumen28 halamanPALSUN Flat Solid Polycarbonate SheetsGirish DhawanBelum ada peringkat

- Archive For Exercise - Locomotiva 2Dokumen37 halamanArchive For Exercise - Locomotiva 2Yang Sun100% (1)

- Daylight & Architecture: Magazine by VeluxDokumen57 halamanDaylight & Architecture: Magazine by VeluxKotesh ReddyBelum ada peringkat

- Colin Rowe: Space As Well-Composed IllusionDokumen19 halamanColin Rowe: Space As Well-Composed IllusionMiruna ElisabetaBelum ada peringkat

- 2014 CatalogueDokumen63 halaman2014 CataloguequilpBelum ada peringkat

- Aldo Van Eyck: Team 10 Primer Team 10 PrimerDokumen5 halamanAldo Van Eyck: Team 10 Primer Team 10 PrimerazimkhtrBelum ada peringkat

- Bauhaus and German Movements PPT SBMISNDokumen68 halamanBauhaus and German Movements PPT SBMISNgayathrimr6867% (3)

- Design Theory of Louis I Kahn 2Dokumen10 halamanDesign Theory of Louis I Kahn 2003. M.priyankaBelum ada peringkat

- Candilis Josic Woods Dialectic of ModernityDokumen4 halamanCandilis Josic Woods Dialectic of ModernityRicardo Gahona100% (1)

- 2017 AD YearbookDokumen127 halaman2017 AD Yearbooknatassa100% (2)

- Rudofsky Bernard Architecture Without Architects A Short Introduction To Non-Pedigreed ArchitectureDokumen63 halamanRudofsky Bernard Architecture Without Architects A Short Introduction To Non-Pedigreed Architecturearnav saikiaBelum ada peringkat

- Alto and SizaDokumen14 halamanAlto and Sizashaily068574Belum ada peringkat

- Architectonic Thought On The Loom PDFDokumen26 halamanArchitectonic Thought On The Loom PDFAnton Cu UnjiengBelum ada peringkat

- Anyone Corporation - Any PublicationsDokumen7 halamanAnyone Corporation - Any Publicationsangykju2Belum ada peringkat

- H Hertzberger - Space and The Archi PDFDokumen294 halamanH Hertzberger - Space and The Archi PDFMadalina Burcescu100% (1)

- Oris.53 Atelier - Bow.wow - IntervjuDokumen10 halamanOris.53 Atelier - Bow.wow - IntervjuAlana PachecoBelum ada peringkat

- ZumthorDokumen27 halamanZumthorGiovanna PigaBelum ada peringkat

- Architecture Layout Final PDF PDFDokumen8 halamanArchitecture Layout Final PDF PDFIvaJoBelum ada peringkat

- 03 2 Grafton-CDokumen6 halaman03 2 Grafton-CChristopher VasquezBelum ada peringkat

- ARQ - Early Venturi, Rauch & Scott BrownDokumen10 halamanARQ - Early Venturi, Rauch & Scott BrownJohn JohnsonBelum ada peringkat

- Objekt Series - School PDFDokumen210 halamanObjekt Series - School PDFadhiBelum ada peringkat

- The Solitude of BuildingsDokumen5 halamanThe Solitude of BuildingsMaria Daniela AlcantaraBelum ada peringkat

- Innovative Timber ConstructionDokumen8 halamanInnovative Timber ConstructionRahul RaghavBelum ada peringkat

- Fabric Formwork ThesisDokumen4 halamanFabric Formwork ThesisBestPaperWritingServiceSingapore100% (2)

- Connecting Inside and OutsideDokumen10 halamanConnecting Inside and OutsidetvojmarioBelum ada peringkat

- Filiz KlassenDokumen2 halamanFiliz KlassenjamesnitpBelum ada peringkat

- Dumitrescu A VHDokumen143 halamanDumitrescu A VHAndres EscobedoBelum ada peringkat

- Kraftmaid SelectionGuideDokumen76 halamanKraftmaid SelectionGuideOlivia StrashokBelum ada peringkat

- Ilp P.gudangDokumen8 halamanIlp P.gudangmsanusiBelum ada peringkat

- Total Duration: 2 Hours 30 Minutes Total Marks: 75: IIAD UG Design Aptitude TestDokumen8 halamanTotal Duration: 2 Hours 30 Minutes Total Marks: 75: IIAD UG Design Aptitude TestAnwesha AgrawalBelum ada peringkat

- 2010 2017 Pretech SkillsDokumen137 halaman2010 2017 Pretech SkillsthahiraBelum ada peringkat

- IstructE Question Selection 2015-2020Dokumen74 halamanIstructE Question Selection 2015-2020Vasile BudaBelum ada peringkat

- Alphabet of LinesDokumen25 halamanAlphabet of LinesFana FilliBelum ada peringkat

- Information Sheet 1Dokumen20 halamanInformation Sheet 1princess lyn castromayorBelum ada peringkat

- Architectural Design-I (150101) : ITM UniversityDokumen6 halamanArchitectural Design-I (150101) : ITM Universityanon_891354001Belum ada peringkat

- Pet Portrait Rubric Art 1Dokumen1 halamanPet Portrait Rubric Art 1api-244578825Belum ada peringkat

- Images: How To Draw Human Digestive System Step by ... - YoutubeDokumen1 halamanImages: How To Draw Human Digestive System Step by ... - YoutubePratham KamaniBelum ada peringkat

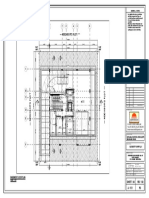

- A-101 Basement Floor PlanDokumen1 halamanA-101 Basement Floor Planjibeesh cmBelum ada peringkat

- The Fundamentals of Design DraftingDokumen21 halamanThe Fundamentals of Design Drafting김면주Belum ada peringkat

- Introduction To AutocadDokumen55 halamanIntroduction To AutocadadityaBelum ada peringkat

- Arts, 6 Quarter 2 WK 3-4 Module 3Dokumen27 halamanArts, 6 Quarter 2 WK 3-4 Module 3Marijoy Gucela100% (1)

- List of Exhibited Works: Paintings and SculpturesDokumen5 halamanList of Exhibited Works: Paintings and SculpturesBellingBelum ada peringkat

- VisualArts Grade9 10 PDFDokumen44 halamanVisualArts Grade9 10 PDFJames Matthew AmbrocioBelum ada peringkat

- Sample Holistic and Analytic RubricDokumen6 halamanSample Holistic and Analytic RubricKerstmis “Scale” NataliaBelum ada peringkat

- Visual Arts GlossaryDokumen16 halamanVisual Arts GlossaryGregory FitzsimmonsBelum ada peringkat

- Forceville (1996) Kress and Van Leeuwențs Reading Images PDFDokumen16 halamanForceville (1996) Kress and Van Leeuwențs Reading Images PDFRăzvanCristianBelum ada peringkat

- Illustration 7Dokumen18 halamanIllustration 7Jeh UbaldoBelum ada peringkat

- Wartegg FinalDokumen28 halamanWartegg FinalMarlene Cabrera SantosBelum ada peringkat

- Foreshortening: 1. What Is An Isometric Drawing?Dokumen3 halamanForeshortening: 1. What Is An Isometric Drawing?jjjjjBelum ada peringkat

- Initial Parent LetterDokumen3 halamanInitial Parent Letterapi-237711646Belum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan Year 8 Term 1 Week 2 Elements of Art 2Dokumen3 halamanLesson Plan Year 8 Term 1 Week 2 Elements of Art 2Najla Ayari/Art TeacherBelum ada peringkat

- Arts AGDokumen103 halamanArts AGRadio UnknownBelum ada peringkat

- Bill Henson Portfolio 2Dokumen19 halamanBill Henson Portfolio 2Romon YangBelum ada peringkat

- 1253 - Crayola DreamMakers ArtDesignDokumen106 halaman1253 - Crayola DreamMakers ArtDesignCikgu SuhaimiBelum ada peringkat

- Hum PaperDokumen8 halamanHum PaperPatricia BautistaBelum ada peringkat

- Cross Hatching TutorialDokumen3 halamanCross Hatching TutorialjordifoBelum ada peringkat

- 1st Computer BookDokumen72 halaman1st Computer BookArpitBelum ada peringkat