Brand Social Power

Diunggah oleh

Batica MitrovicDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Brand Social Power

Diunggah oleh

Batica MitrovicHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Does Brand Social Power

Mean Market Might?

Exploring the Influence of

Brand Social Power on

Brand Evaluations

Jody L. Crosno

West Virginia University

Traci H. Freling

University of Texas–Arlington

Steven J. Skinner

University of Kentucky

ABSTRACT

The importance of brand equity has been recognized in the market-

ing literature for years. Although researchers generally agree there

is a social component to brand equity, empirical work in this area

stops short of exploring the brand’s ability to exert a social influence

on consumers and their choices. The present manuscript attempts to

address this deficit and extend the brand equity literature by pro-

posing a new construct—brand social power. Drawing from research

on social influence and perceived power, five bases of brand social

power are identified and a conceptual attempt is made to integrate

brand social power with existing brand equity frameworks. The

impact of brand social power is also examined empirically at the

level of individual power bases, for overall brand social power, and

in terms of brand equity. © 2009 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 26(2): 91–121 (February 2009)

Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com)

© 2009 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. DOI: 10.1002/mar.20263

91

INTRODUCTION

Perceived power has frequently been examined as a central construct for under-

standing human nature in general (Bierstedt, 1950; French, 1956; French &

Raven, 1959) and buyer behavior in particular (Busch, 1980; Gaski, 1984a;

MacKenzie & Zaichkowsky, 1981). Research in social psychology suggests power,

“the ability to evoke change in another’s behavior . . .” (Gaski, 1984a, p.10), is a

multidimensional construct that may be acquired through legitimacy, rewards,

coercion, reference, or expertise (French & Raven, 1959). Power is thought to influ-

ence satisfaction (Bachman, 1968; Bachman, Smith, & Slesinger, 1966), attrac-

tion (Raven & French, 1958), conformity (Warren, 1968, 1969), social influence

(Lippitt, Polansky, & Rosen, 1952), conflict (Raven & Kruglanski, 1970), and

productivity (Hill & French, 1967; Student, 1968).

In marketing, researchers have documented power as a determinant of sat-

isfaction in franchise dealings (Gaski, 1984a; Hunt & Nevin, 1974), an antecedent

to conflict among channel members (Gaski, 1984b; Lusch, 1976), a distinguish-

ing factor in relationships between sales managers and personnel (Busch, 1980;

Busch & Wilson, 1976; Skinner, Dubinsky, & Donnelly, 1984), and an important

creative element in advertising (MacKenzie & Zaichkowsky, 1981; Sullivan &

O’Connor, 1985). These studies in channels, sales, and advertising constitute

meaningful empirical explorations of the effects of power in marketing; how-

ever, the role of power as it relates to branding remains uncharted territory.

Interestingly, the “power of the brand” has been extolled in numerous marketing

publications (Aaker, 1991; Campbell, 2002; Davis, 2002; Davis, 2000; Fournier,

1998; Keller, 1999), and there is limited behavioral evidence suggesting brands

exert power by influencing purchasing decisions (Aaker, 1991; Campbell, 2002;

Wah, 1998) and consumers’ willingness to pay a price premium (Aaker, 1991). Is

it possible that brands possess the power to influence these and other aspects of

consumer behavior? Perhaps not in a literal sense but rather in an attributional

manner, as when individuals ascribe power—among other characteristics and

associations—to brands based on their consumer–brand relationships.1 Might

brands derive power from different bases that they exercise over consumers, just

as individuals influence others by drawing upon different sources of power? Could

these bases of power be leveraged as points of differentiation in brand position-

ing strategies? The current research attempts to replace speculation about these

issues with theory and data, fusing the branding literature with social influence

theory to define brand social power and formulating a typology of brand social

power. Further, key indicators of each brand social power dimension are identi-

fied and empirically examined, and the relationships of individual bases of brand

social power to overall brand social power are tested. The manuscript also explores,

both conceptually and empirically, how brand social power relates to brand equity

and affects attitudinal responses.

This paper begins with a selective review of research in the areas of power

and branding to unite these heretofore disparate streams of literature. Brand

1

In this article, brand social power is not conceptualized as being an absolute resource but is

instead treated as an attribution (Brill 1992). The authors do not contend that brands possess

brains that allow them to accumulate knowledge and expertise, as do humans. Rather, consis-

tent with the power as an attribution perspective, the authors suggest that people attribute

power and the corresponding associations (e.g., knowledge and expertise) to brands based on

their consumer–brand relationships.

92 CROSNO, FRELING, AND SKINNER

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

social power and its constituent dimensions are then defined, and hypotheses

are offered about each and about associations between individual brand social

power dimensions and overall brand social power, as well as overall brand

social power and brand equity. A study is conducted to test these expectations,

and a discussion of the theoretical and practical implications emanating from

findings regarding brand social power follows.

CONCEPTUAL DEVELOPMENT & RESEARCH HYPOTHESES

Theory of Social Influence and Power

Researchers generally conceptualize power as either a resource or an attribu-

tion (Brill, 1992). When viewed as a resource, power is defined in terms of inher-

ent characteristics of the individual trying to exert influence (Brill, 1992). Here,

power is seen as absolute—either an individual does or does not possess power.

When viewed as an attribution, power is defined in terms of perceived charac-

teristics of the individual trying to exert influence (Brill, 1992). According to

this perspective, the power one individual holds over another person may be

perceived and not necessarily absolute. That is, power is not something one pos-

sesses, but rather a quality an individual is bestowed through “the perceptions

of the interpersonal dynamics experienced in relationships” (Brill, 1992, p. 836).

Although there is no consensus regarding whether power is innate or perceived

(Gaski, 1984a), both perspectives coalesce around a definition of the construct

as “the ability to evoke change in another’s behavior, or cause someone to do

something that he/she would not have done otherwise” (Gaski, 1984a, p. 10).

An individual may access any number of power sources to influence the behav-

ior of others. French and Raven’s (1959) power typology—arguably the received

wisdom in social influence research—proposes five bases from which one may

derive power. Legitimate power is based on the perception of an individual that

another person has the legitimate right to influence him or her, and that he or

she is obligated to accept the influence. Reward power is based on the percep-

tion of an individual that another person has the ability to reward him or her.

Coercive power is based on the perception of an individual that another person

has the ability to punish him or her. Expert power is based on the perception of

an individual that another person has some specialized knowledge or expertise.

Referent power is based on an individual’s identification with, and desire to be

similar to, another person.

Power in Marketing

The concept of power in general, and French and Raven’s (1959) typology more

specifically, has been utilized in various disciplines, including marketing. The

most pervasive marketing application of French and Raven’s research has been

in channels of distribution (Butaney & Wortzel, 1988; El-Ansary & Stern, 1972;

Frazier & Summers, 1984; Frazier & Summers, 1986; Gaski, 1984a; Hunt &

Nevin, 1974; John, 1984; Lusch, 1976; Wilkinson, 1973). Research in this area

focuses on the relationships between channel members, with emphasis on power,

conflict, and satisfaction (Gaski, 1984a). More specifically, this research indi-

cates that the sources of power possessed by channel members may affect the

DOES BRAND SOCIAL POWER MEAN MARKET MIGHT? 93

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

level of conflict in the channel, as well as the level of satisfaction experienced

by channel members (Gaski, 1984a). For example, Hunt and Nevin (1974) assert

that franchisor power is a function of the sources of power available and that

the use of coercive (versus noncoercive) sources of power in the marketing chan-

nel results in less satisfaction. Similarly, Lusch (1976) suggests that using

noncoercive sources of power tends to result in less intrachannel conflict, whereas

coercive sources of power are likely to increase conflict.

Power also figures prominently in sales research (Busch, 1980; Busch &

Wilson, 1976; Skinner, Dubinsky, & Donnelly, 1984), especially in regard to the rela-

tionship between sales managers and sales personnel, and how the bases of power

affect roles, conflict, and satisfaction of sales personnel. For instance, Busch (1980)

contends that the bases of power employed by sales managers impact salesper-

sons’ satisfaction with supervision, role clarity, and propensity to leave. Skinner,

Dubinsky, and Donnelly (1984) also investigated the relationship between the

bases of power utilized by retail sales managers and sales personnel job satisfac-

tion; however, they extended the sales literature to include role conflict and role

ambiguity. An essential implication of this research is that the use of noncoercive

(vs. coercive) sources of power engender salespeople with higher job satisfaction,

less role conflict, and less role ambiguity (Skinner, Dubinsky, & Donnelly, 1984).

Research in advertising also incorporates the concept of power (MacKenzie &

Zaichowsky, 1981; Sullivan & O’Connor, 1985). Content analysis has been employed

to determine the differential use of the various bases of power in print advertis-

ing. For example, MacKenzie and Zaichowsky (1981) investigated the content of

alcohol advertising, using French and Raven’s (1959) typology. A key finding is that

wine advertisements utilize informational and expert power more than other

sources of power, whereas liquor and beer ads rely primarily upon reward power.

Brand Social Power

Just as power influences the effectiveness of relationships and strategies in

marketing channels, sales, and advertising, it may play a pivotal role in the con-

text of branding. Extending the general definition of power to a branding

context, brand social power is defined as “the ability of a brand to influence the

behavior of consumers and to cause a consumer to do something he or she would

not have done otherwise.” To be clear, brand social power is viewed from the

“power as an attribution” standpoint, wherein the power of a brand is based on

consumers’ perceptions of the brand’s power (and not absolute power). So,

although a brand does not possess actual power, consumers who know and use

a brand may attribute authority, control, influence, and other characteristics to

it based on their consumer–brand relationship and past usage experiences.2

Brand Social Power and Brand Equity. Brand social power is distin-

guished from (customer-based) brand equity, which Aaker (1991) defines as

“a set of brand assets and liabilities linked to a brand, its name and symbol,

that add to or subtract from the value provided by a product or service to a firm

and/or to that firm’s customers” (p. 15). Here, brand social power is treated as

a component of customer-based brand equity, regardless of whether the con-

struct is treated as cognitive or relational in nature (Gurhan-Canli & Ahluwalia,

2

See Footnote 1.

94 CROSNO, FRELING, AND SKINNER

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

1999). The cognitive perspective of brand equity draws upon the memory liter-

ature and learning theory to explain brand equity and how to build strong

brands (Aaker, 1996b; Keller, 2000; Keller, 1999; Keller, 1993). Aaker (1991)

offers a commonly accepted (primarily cognitive) model, which includes five

bases of brand equity: (1) brand associations, (2) brand awareness, (3) perceived

quality, (4) brand loyalty, and (5) other proprietary assets. In this framework, each

of these bases constitutes an asset that creates brand equity in a variety of dif-

ferent ways. Brand social power—a perceptual concept that resides in the minds

of a brand’s consumers—may be characterized as a brand association, defined

by Aaker (1991) as “anything ‘linked’ in memory to a brand” (p. 109). Aaker

(1996a) asserts that brand equity is supported in large part by the associations

consumers make with a brand, which may include perceptions regarding the

brand social power that brand wields. As such, it is possible that brand social

power—like any other brand association—may help consumers to retrieve and

process branding information, differentiate a brand, generate reasons for con-

sumers to buy a brand, create positive attitudes and feelings toward a brand,

and provide a basis for brand extensions (Aaker, 1991).

The relational perspective of brand equity emphasizes the consumer–brand

relationship and depicts brand equity as a function of the personal value or

meaning a brand holds for the consumer (Blackston, 1992; Chang & Chieng,

2006; Fournier, 1998; Gurhan-Canli & Ahluwalia, 1999; Ji, 2002; McCracken,

1993; Woodside, 2004). Representative of work in this vein is Fournier’s (1998)

brand relationship quality construct, which assesses the strength and durabil-

ity of a consumer–brand relationship in terms of three dimensions: (1) affective

and socioemotive attachments (consisting of love/passion and self-connection);

(2) behavioral ties (which include commitment and interdependence); and (3) sup-

portive cognitive beliefs (comprised of intimacy and brand partner quality).

Viewing brand social power through a relational lens, one might perceive brand

social power as a component of the brand behaviors that nourish the

consumer–brand relationship. For example, brand behaviors that wield referent

brand social power may influence a consumer’s self-connection with a brand. Like-

wise, commitment may be cultivated through reward brand social power or com-

pelled through coercive brand social power. And legitimate brand social power

may improve a consumer’s perceptions of brand partner quality.

Brand Social Power and Attitudes. In addition to demarcating brand

social power as a driver of brand equity, it is also important to reconcile brand

social power with extant attitude theory. Briefly, an attitude is defined as “a psy-

chological tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some

degree of favor or disfavor,” (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993, p.1), whereas a brand atti-

tude is the general evaluation (favorable or unfavorable) of a particular brand.

Social scientists (Katz & Stotland, 1959; Krech & Crutchfield, 1948; McGuire, 1969;

McGuire, 1985; Rosenberg & Hovland, 1960; Smith, 1947; Triandis, 1971) have

long acknowledged that attitudes may elicit three types of evaluative responses:

affective responses comprised of the feelings or emotions an individual has

in relation to an attitude object; cognitive responses consisting of the thoughts an

individual has about the attitude object; and conative responses composed of

an individual’s actions with respect to the attitude object. However, empirical

tests of the tripartite model of attitudinal responding have produced equivocal

results (Bagozzi, 1978; Breckler, 1984; Kothandapani, 1971; Ostrom, 1969) for

this conceptual trinity, and the evidence supporting a discriminant behavioral

DOES BRAND SOCIAL POWER MEAN MARKET MIGHT? 95

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

component is particularly tenuous (Bagozzi & Burnkrant, 1979; Bagozzi &

Burnkrant, 1985; Dillon & Kumar, 1985).

The current research focuses primarily on evaluative responses that are cona-

tive in nature—specifically, the ability of a brand to wield social power over, and

induce certain behaviors among, their consumers. So, aside from the prescrip-

tive utility that a better understanding of brand social power may provide to

brand managers charged with developing positioning strategies for their brands,

results generated here may add another voice to the debate regarding whether

the division of evaluative attitudinal responses is one worth preserving in cur-

rent attitude theory and whether consumers do, in fact, respond to attitude

objects such as brands in a behavioral manner.

The Bases of Brand Social Power

Given this conceptualization of brand social power in relation to brand equity

and attitude theory, attention is now turned to further expanding the internal

structure of the construct. Adapting French and Raven’s (1959) typology of social

influence, five bases of brand social power are developed that correspond to

their original bases of power, including legitimate brand social power, reward

brand social power, coercive brand social power, expert brand social power, and

referent brand social power. Different factors that are likely to underpin each

source of brand social power are also identified, and hypotheses are offered

regarding the relationship(s) between these factors and the strength of corre-

sponding brand social power bases.

Legitimate Brand Social Power. Legitimate brand social power is the abil-

ity of a brand to influence a consumer’s behavior via its perceived position in the

industry, its reputation, and/or its duration in the industry. A brand’s position

within its respective industry may be gauged by its perceived market share. The

theory of double jeopardy may inform theorizing on how a brand’s industry posi-

tion may influence its legitimate brand social power. According to this theory,

brands with large market share have more consumers who purchase more fre-

quently than brands with small market share (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001). Fur-

ther, the theory of double jeopardy suggests that consumers prefer high market

share brands over low market share brands (Chaudhuri, 2002), presumably

because of consumers’ perceptions that they “ought to” purchase the high mar-

ket share brand due to some internalized value(s). In addition to having more reg-

ular consumers, brands with greater market share should also have stronger

legitimate brand social power than brands with smaller market share.

H1a: Legitimate brand social power is stronger when the perceived position

of a company’s brand is high.

Another indicator of legitimate brand social power is the brand’s reputation.

Vergin and Qoronfleh’s (1998) analysis of corporate reputation and stock perform-

ance indicate that a company’s stock performance is directly and positively related

to its reputation. One reason that corporate reputation results in better market

performance is customers’ willingness “to purchase the firm’s existing products and

services and accept new offerings from it” (Vergin & Qoronfleh, 1998, p. 39). Similarly,

Chaudhuri (2002) found a significant relationship between brand reputation and

96 CROSNO, FRELING, AND SKINNER

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

brand sales, market share, and relative price. This study suggests that the rela-

tionship between brand reputation and brand performance is a function of the con-

sumer’s perception that he or she should purchase brands with strong reputations

because of some internalized value(s). Along with instilling receptiveness among

consumers to purchase current and future offerings, brands with a strong reputa-

tion should also have stronger legitimate brand social power. It is important to note

that brand reputations may vary in strength and valence. Brands with strong rep-

utations should be more powerful than brands with weak reputations, and brands

with bad reputations will likely detract from the brand’s legitimate power.

H1b: Legitimate brand social power is stronger when the perceived reputation

of a company’s brand is strong and favorable.

A brand’s duration in the industry may also influence its legitimate brand

social power. Bogart and Lehman (1973) found heightened brand awareness

with more extensive brand history. When researchers offered respondents a

nickel for every brand name they could recall within a four-minute time frame,

not one out of 1860 brand names mentioned was introduced within the preced-

ing five years of the study, and 89% of the brands recalled were 25 years or older

(Bogart & Lehman, 1973). These results provide compelling evidence that con-

sumers are more familiar with established brands. Moreover, research demon-

strates that consumers often adopt a decision rule to purchase only “familiar,

well-established brands” (cf. Keller, 1993, p. 3). Therefore, brands with a longer

industry presence should have stronger legitimate brand social power.

H1c: Legitimate brand social power is stronger when the industry duration

of a company’s brand is long.

Reward Brand Social Power. Reward brand social power is the ability of

the brand to influence a consumer’s behavior through perceptions that the brand

can mediate positive outcomes (i.e., rewards) for the individual. Positive out-

comes in this case refer to intrinsic rewards that the brand can offer consumers,

such as satisfaction, a sense of achievement, a sense of acceptance, a positive

image, and higher perceived social status.

The strength of reward brand social power is contingent upon the brand’s

ability to mediate rewards, as well as the value the consumer places on those

rewards. This assertion is consistent with expectancy theory, which has been

used as an indicator of job behavior and motivation (Vroom, 1964). According

to expectancy theory, the level of effort an individual expends is a product of

the expectancy of an outcome and the valence of that outcome (Behling & Starke,

1973). If an individual expects no outcome or regards the associated outcome as

undesirable, the result will be zero motivation and thus no effort expended

(Behling & Starke, 1973).

When the expectation of being rewarded by a brand is low, the brand should

not have strong reward brand social power. However, when the expectation of

being rewarded by the brand is high, the valence associated with that reward

should determine the brand’s reward power. (A high valence would likely be

attached to a sense of achievement, a sense of acceptance, a positive image,

higher social status, and/or satisfaction.) When expectancy is high and the

DOES BRAND SOCIAL POWER MEAN MARKET MIGHT? 97

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

consumer places a low value on the associated reward, the brand reward power

should be low. When expectancy is high and the consumer places a high value

on the associated reward, s/he will be more susceptible to reward brand social

power of the brand. Thus, high expectancy of a desirable reward should result

in strong reward brand social power. In contrast, low expectancy and/or low

valence should result in weak reward brand social power, meaning the brand will

be less likely to influence the consumer’s behavior.

H2a: Reward brand social power is stronger when consumers associate favor-

able outcomes with using a company’s brand.

H2b: Reward brand social power is stronger when consumers value rewards

associated with using a company’s brand.

Coercive Brand Social Power. Coercive brand social power is the ability

of the brand to influence a consumer’s behavior through the perception that the

brand can mediate negative outcomes (i.e., punishments) for the individual.

Negative outcomes in this case may include dissatisfaction, a sense of failure,

a sense of rejection or disapproval, a negative image, and lower perceived social

status. The strength of a brand’s coercive brand social power depends on the

ability of the brand to mediate punishment(s) and the consumer’s perception

of the severity of the punishment. According to reinforcement theory, human

behavior is determined by environmental consequences (Schermerhorn, 2002).

More specifically, this theory states that behavior followed by pleasant (unpleas-

ant) consequences or outcomes will (will not) be repeated (Skinner, 1953). If a

brand does not have the ability to create negative outcomes for the consumer

(i.e., it can not dispense punishment), the brand is unlikely to influence the

behavior of consumers and thus will have relatively weaker coercive brand

social power.

When the brand does have the ability to administer punishment, the strength

of its coercive brand social power (and effectiveness in influencing consumer

behavior) will hinge upon perceived severity of the punishment (French & Raven,

1959). Perceptual studies of deterrence have indicated that severe punishment has

“a significant deterrent effect” (Grasmick & Bryjak, 1980). Perceived severity is

high when consumers have a strong desire to avoid failure, rejection or disap-

proval, a negative image, low social status, and/or dissatisfaction. If the consumer

perceives that not using the brand will result in one of these outcomes, the brand’s

coercive brand social power will be strong and he or she will be more likely to

purchase and use the brand. On the other hand, when the perceived severity of

punishment is low, the consumer will not be as amenable to the brand’s influence

and thus the brand’s coercive brand social power should be considerably weaker.

H3a: Coercive brand social power is stronger when consumers associate neg-

ative outcomes with not using a company’s brand.

H3b: Coercive brand social power is stronger when consumers have strong

desire to avoid punishments associated with not using a company’s brand.

Expert Brand Social Power. Expert brand social power is the ability of

the brand to influence a consumer’s behavior through perceptions that the brand

98 CROSNO, FRELING, AND SKINNER

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

has specialized knowledge and/or expertise.3 Specialized knowledge and/or

expertise in this case refer to the innovativeness, quality, consistency of supe-

rior performance, and/or superior knowledge associated with the brand.

One dimension of a brand’s expert brand social power is consumers’ percep-

tion of its specialized knowledge and/or expertise within the product category

(French & Raven, 1959). Mowen, Wiener, and Joag (1987) found that as per-

ceived expertise of a source increases, its level of persuasion also increases.

Similarly, Walker, Langmeyer, and Langmeyer (1992) found perceived expertise—

among a host of other source characteristics—to be the only factor to signifi-

cantly influence the purchase intentions of consumers. The influence of expert-

ise on behavior has also been documented (Busch & Wilson, 1976; Crisci &

Kassinove, 1973; Liu & Leach, 2001; Taylor & Woodside, 1982; Woodside &

Davenport, 1974; Woodside & Pitts, 1975). Crisci and Kassinove (1973) found that

compliance with a source’s recommendations varies with the perceived level of

expertise. Woodson and Davenport (1974) established that an expert salesper-

son induces a significantly higher number of customers to purchase a product

than a nonexpert salesperson. Busch and Wilson (1976) demonstrated that a

salesman with greater expertise is more effective than a salesman with lesser

expertise in influencing the behaviors of potential consumers. Liu and Leach

(2001) found that the perceived level of salesperson expertise is positively related

to customer satisfaction, which in turn is positively related to behavioral loyalty.

Given the demonstrated effectiveness of expertise in influencing consumer

behavior in a selling context, a brand’s expert brand social power is expected to

elicit similar behavioral responses among consumers.

H4a: Expert brand social power is stronger when consumers associate indus-

try knowledge and/or expertise with a company’s brand.

A consumer’s knowledge or skills in a particular domain may also affect the

strength of a brand’s expert brand social power. French and Raven (1959) con-

tend that an influencee (i.e., the consumer) not only evaluates the expertise of the

influencer (i.e., the brand) against an absolute standard, but also in relation to

his or her own knowledge. Yagil (2002) confirmed this contention, demonstrat-

ing that expert power is moderated by the subordinate’s expertise. When the

consumer is not very knowledgeable in a given area, the expert brand social

power should be stronger. However, when the consumer is knowledgeable, the

brand’s ability to influence the consumer with its perceived knowledge and expert-

ise diminishes, and the brand’s expert brand social power should be weaker.

H4b: Expert brand social power is stronger when consumers’ industry knowl-

edge is relatively low.

Referent Brand Social Power. Referent brand social power is the ability

of the brand to influence a consumer’s behavior by fostering attraction to the

brand and/or identification with the brand. When a brand possesses referent brand

social power, consumers pursue a feeling of oneness with the brand and seek to

become closely associated with it.

The strength of referent brand social power depends on the consumer’s attrac-

tion to, and identification with, the brand. French and Raven (1959) contend that

the greater the attractiveness of an individual, the greater the identification and

3

See Footnote 1.

DOES BRAND SOCIAL POWER MEAN MARKET MIGHT? 99

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

referent power of that individual. As an individual becomes more attractive, the

desire for identification with that individual increases. An increased sense of iden-

tification, in turn, strengthens the individual’s referent power. Following this logic,

as a brand’s attractiveness increases, so should its referent brand social power.

But what heightens attraction? Research in social psychology suggests that

a key source of interpersonal attraction is perceived similarity (Blass & Schwarcz,

1982). Given consumers’ personification of brands (Aaker, 1997; Haigood, 1999;

Lau & Phau, 2007; Sweeney & Brandon, 2006) and relationships with brands

(Fournier, 1998), it is proposed that this source of attractiveness will extend to

the consumer–brand relationship and that consumers who perceive similari-

ties with the brand will also be more strongly attracted to it.

Raven and Kruglanski (1970) indicate that the perception of similarity leads

an individual to accept the influence and change behavior accordingly, a con-

tention that finds support in the marketing literature. Research on self-

congruency verifies the link between perceived consumer–brand similarity and

consumer behavior. More specifically, Sirgy (1982) asserts that perceived simi-

larities of the characteristics of the consumer’s actual or ideal self to those of the

brand’s image lead to greater preference for the brand, more favorable purchase

intentions, increased product usage, increased ownership, and greater brand

loyalty, indicating a strong association between perceived similarity and behav-

ioral influence. Perceived similarity should also lead to greater identification,

resulting in stronger referent brand social power. However, if the consumer does

not perceive similarities and/or does not identify with (or does not want to be iden-

tified with) the brand, the referent brand social power should be weaker.

H5: Referent brand social power is stronger when consumers perceive them-

selves as similar to a company’s brand.

Multidimensional Brand Social Power. Naturally, brands vary in terms

of the number and strength of bases from which they derive power, and the col-

lective power they wield. Harley Davidson is a brand with referent power; how-

ever, it might also be perceived as having expert power due to its high quality;

legitimate power due to its position in the industry and reputation; reward

power due to the sense of affiliation, acceptance, and satisfaction that accompany

ownership of a Harley Davidson motorcycle; and coercive power due to the sense

of rejection from certain motorcycle aficionados that one might experience if

he or she does not own a Harley.

Given the various bases of brand social power available to Harley Davidson,

it can determine which base of brand social power or combination of bases will

be most effective in influencing consumer behavior (Raven & Kruglanski, 1970).

An increase in the number and strength of power bases should be associated with

an increase in overall brand social power and may enable the brand to exert

power in an array of contexts. Different power bases might be situationally

more effective in influencing various instances of consumer behavior. Thus, the more

bases of power a brand has to access, the greater its ability to influence con-

sumer behavior should be. As the number of strong bases of brand social power

increases, the strength of the brand’s overall power is expected to increase.

H6: Having strong brand social power on more than one dimension leads to

relatively greater overall brand power.

100 CROSNO, FRELING, AND SKINNER

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

The Relationship of Brand Social Power to Brand Equity. As pre-

viously discussed, brand social power may be conceptually incorporated into

existing brand equity frameworks, both cognitive and relational. Cognitively

speaking, perceptions of a brand’s social power affect its brand image, the “set of

associations, usually organized in some meaningful way” (Aaker, 1991, p. 109).

Given that strong, favorable brand associations are believed to enhance brand

equity (Keller, 1993)—a central cognitive tenet—when consumers regard a brand as

more (less) powerful, that brand should also possess relatively greater (lesser)

brand equity. Similarly, brand behaviors which intimate power have the poten-

tial to affect the consumer–brand relationship in terms of brand loyalty and rela-

tionship stability—fundamental variables in the relational tradition. Hence,

whether viewing brand equity cognitively or from the relational perspective,

greater brand social power is expected to be associated with greater brand equity.

H7: Greater overall brand power is associated with greater brand equity.

METHODOLOGY

Subjects and Design

This study involved a one-way between-subjects factorial design consisting of two

sets of five different brands with varying levels of perceived brand social power

(more vs. less). A total of 201 students enrolled in an undergraduate marketing

course at a large southeastern University participated in the study. For partic-

ipation each student received extra credit points toward his or her final grade

in the course.

Stimuli Selection

A multistage content validity assessment guided the selection of a comprehensive

and representative set of brands for inclusion in the study (Bearden, Netemeyer, &

Teel, 1989). In the interest of ecological validity, an effort was made to identify

an array of well-known national brands in a range of product categories that rep-

resented a spectrum of power types and levels. First, following exposure to the def-

initions of each base of brand social power, a convenience sample of 22 adult

consumers were asked to provide a list of brand names that were reflective of

each dimension. Added to this list were brands from the represented product cat-

egories that were thought to be relatively less powerful. Seven marketing faculty

members were then asked to rate how well each of the comprehensive list of brand

names reflected the different bases of brand social power, using the following

scale: 1 ⫽ clearly representative, 2 ⫽ somewhat representative, and 3 ⫽ not rep-

resentative at all (Zaichkowsky, 1985). For each individual base of power, one rel-

atively powerful brand name that five of seven panel members evaluated as

“clearly representative” was retained. One brand evaluated as “somewhat repre-

sentative” or “not representative” of each dimension of brand social power was also

selected to include as a correspondingly less powerful brand for each category.

Ultimately, two sets of brands with more (less) brand social power in the following

five product categories were developed: automotive tires, sport utility vehicles,

sports cars, computer software, and carbonated cola beverages.

DOES BRAND SOCIAL POWER MEAN MARKET MIGHT? 101

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

Procedure

The study took place in a classroom research setting, wherein subjects were ran-

domly assigned to one of the two treatment conditions so that each cell contained

approximately 100 subjects. Upon entering the room, an experimenter greeted

subjects and handed them a booklet containing a description of the study’s purpose,

basic instructions, the stimulus material, and related measures. To control for

demand effects, the cover page informed subjects that the experimenters had no

association with the manufacturer or the advertising agency for the featured

products, and simply desired honest answers. The experimenter specifically

instructed subjects not to communicate with or observe the work of others. Fur-

ther, subjects were spatially separated while completing the questionnaire and

did not know that other subjects received different information based on their cell

assignment. The experimenter also instructed subjects not to page ahead in the

stimulus booklet or go back and change responses. The putative purpose of

the study was to assess consumers’ perceptions of a variety of brands.

On the next page subjects saw a list of brands for their assigned cell, includ-

ing five brands possessing more (less) of at least one dimension of brand social

power. Directions on this page instructed subjects to take their time reading a

series of questions relating to individual dimensions of brand social power for

each of the five brands. Among these items was a manipulation check asking sub-

jects to indicate the nature of each brand’s power by choosing one of six categorical

responses relating to legitimate, reward, coercive, expert, referent, or no brand

social power. Also included were 35 items that enabled investigators to further

gauge the effectiveness of the manipulation and to assess the relationship of

various indicators to individual power bases, overall brand social power, and

brand equity. These items were developed by modifying Swasy’s (1979) Social

Power Scales for use with products.4 Subjects were advised to think of each

brand in comparison to other brands in its product category—and not other

brands appearing in the stimulus packet—and to indicate the extent of their

agreement with each statement using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from

1 ⫽ strongly disagree to 7 ⫽ strongly agree. (These items appear in the Appen-

dix, along with all other measures taken in the study.)

Next, subjects answered several questions that would enable investigators to

gauge their attitudes toward the brand and purchase intentions, along with

overall brand equity for each brand. Attitude toward the brand was assessed by

asking subjects to complete the statement, “I feel (this brand) is . . .” using four

7-point semantic differential items (anchored by favorable/unfavorable,

good/bad, likable/unlikable, and pleasant/unpleasant). An average of the scale

items was used to form a composite brand attitude measure. This measure is con-

sistent with those reported in the marketing literature (Edell & Staelin, 1983;

Keller, 1991; MacKenzie, Lutz, & Belch, 1986).

4

Swasy’s (1979) Social Power Scales evaluate the construct of human social power conceptualized

by French and Raven (1959), whereas the current research explores brand social power. The

phrasing of many individual items comprising Swasy’s (1979) scale required modification because

they specifically directed subjects to think of another human being (not a brand) when respond-

ing. Where necessary, the authors adapted these individual items so that subjects would evalu-

ate their relationship with a brand, and not another human being. For example, Swasy’s (1979)

scale included the following item for assessing the reward social power of a particular human:

The reason for doing as A suggests is to obtain good things in return. The corresponding item for

assessing the reward social power of a particular brand is: The reason for purchasing this brand

is to obtain good things in return.

102 CROSNO, FRELING, AND SKINNER

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

Subjects were also asked to indicate the likelihood that they would purchase

each brand when the next purchase occasion in the respective product category

arose, using four 7-point semantic differential items (anchored by very likely/not

at all likely, very probable/not at all probable, very possible/not at all possible,

and very certain/not at all certain). An average of the scale items was used to

form a composite purchase intention measure. This measure of purchase inten-

tion parallels those used in previous marketing studies (Bennett & Harrell, 1975;

Dover & Olson, 1977; Smith & Swinyard, 1983; MacKenzie, 1986; Marks &

Kamins, 1988).

Using Ha’s (1996) Brand Equity scale subjects’ impressions of each brand’s

equity was gauged based on its name and image. Subjects indicated their agree-

ment (disagreement) with 11 seven-point Likert-type statements, which were

then averaged to form a composite brand equity measure.

Because extant research suggests that product familiarity can influence the

manner in which subjects process information about brands (Johnson & Russo,

1984; Marks & Olson, 1981; Wright, 1975), subjects’ familiarity with the prod-

uct category of each stimulus product was also assessed. Utilizing Machleit,

Allen, and Madden’s (1993) Brand Familiarity scale, subjects rated their famil-

iarity, experience, and knowledge level with each product category using three

7-point semantic differential items. Responses to each of these items were aver-

aged to form a composite familiarity measure for each product category.

Finally, each subject was asked to provide detailed demographic information

and was probed on the purpose of the study. Demographic profiles of the sub-

jects were similar, and no evidence of response bias was found. Further, exam-

ination of open-ended remarks regarding the experimental guise suggested that

no subjects guessed the true objective of the research.

RESULTS

Manipulation Checks

Although brand social power was manipulated through stimulus product selec-

tion and not the experimental procedure, it was also necessary to ascertain that

each relatively powerful brand chosen for inclusion in the study was indeed an

exemplar of the intended brand social power dimension and provided the expected

contrast to the comparably less powerful brand in the same product category.

Assessing the former required a series of chi-square analyses on participants’

perceptions regarding the nature of each brand’s power across product categories.

In order to gauge the latter, ANOVAs were conducted on the perceived differ-

ences in brand social power for strong vs. weak brands within product categories.

Consistent with pretesting results and expectations, a significant majority of

participants perceive (1) the more powerful carbonated cola beverage (92.31%) to

be most reflective of legitimacy (2(5) ⫽ 81.61, p ⬍ 0.05); (2) the more powerful

sports car (96.27%) as embodying reward brand social power (2(5) ⫽ 157.03,

p ⬍ 0.05); (3) the more powerful automotive tire (89.74%) as exemplifying a brand

with coercive brand social power (2(5) ⫽ 199.82, p ⬍ 0.05); (4) the more powerful

computer software brand (90.16%) as most representative of expertise

(x2(5) ⫽ 164.93, p ⬍ 0.05); and (5) the more powerful SUV (93.68%) as clearly

exhibiting referent brand social power (x2(5) ⫽ 140.71, p ⬍ 0.05). (Results for

manipulation checks appear in Table 1.) Aside from establishing that the chosen

DOES BRAND SOCIAL POWER MEAN MARKET MIGHT? 103

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

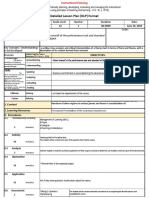

Table 1. Results of Manipulation Checks.

Nature of Brand Social Power

Proportions by Brand Social Power Dimension

Legitimate Reward Coercive Expert Referent None 2

Automotive tires 2.13% 1.48% 89.74% 3.76% 0.69% 2.20% 199.82

(p ⬍ 0.05)

Carbonated 92.31% 3.21% 0.13% 0.82% 2.45% 1.08% 81.61

cola beverages (p ⬍ 0.05)

Computer 3.89% 1.08% 2.63% 90.16% 0.32% 1.92% 164.93

software (p ⬍ 0.05)

Sports cars 0.88% 96.27% 0.07% 0.93% 1.73% 0.12% 157.03

(p ⬍ 0.05)

SUVs 1.57% 3.09% 0.16% 0.92% 93.68% 0.58% 140.71

(p ⬍ 0.05)

Strength of Brand Social Power

Means by Condition

Source of High Low Observed

Variation Power Power Approx. F Sign. of F h2 Power

Legitimacy 5.28 2.33 446.18 p ⬍ 0.01 0.69 1.00

Reward 5.32 3.01 276.85 p ⬍ 0.01 0.58 1.00

Coercion 5.11 1.04 143.61 p ⬍ 0.01 0.42 0.99

Expert 5.65 4.00 453.29 p ⬍ 0.01 0.70 1.00

Referent 4.94 3.00 162.74 p ⬍ 0.01 0.45 0.99

brands were most representative of the intended brand social power dimensions,

this analysis also reveals that, in each comparison set, the more powerful brand is

perceived as possessing traces of additional brand social power dimensions. The

weaker brand in each comparison set is classified as a brand that “does not pos-

sess any special power” by a majority of participants.

It was also important to demonstrate that, within each product category, sub-

jects perceived the exemplar as possessing significantly more of the intended

dimension of brand social power than the relatively weaker brand. ANOVAs com-

paring brands within product categories indicate the strength of brand social

power was effectively manipulated on each dimension as well. Within the car-

bonated cola beverage category, subjects regard the more powerful brand

(M ⫽ 5.28) as possessing significantly more legitimate brand social power

(F(1,199) ⫽ 446.18, p ⬍ 0.001, h2 ⫽ 0.69) than the less powerful brand (M ⫽ 2.33).

Subjects view the more powerful automotive tire (M ⫽ 5.11) as significantly more

coercive (F(1,199) ⫽ 143.61, p ⬍ 0.001, h2 ⫽ 0.42) than the less powerful brand in

this product category (M ⫽ 1.04). The more powerful sports car (M ⫽ 5.32) exhibits

significantly more reward brand social power (F(1,199) ⫽ 276.85, p ⬍ 0.001,

h2 ⫽ 0.58) than the less powerful brand (M ⫽ 3.01). Subjects perceive the more

powerful computer software brand (M ⫽ 5.65) as possessing significantly

more expert brand social power (F(1,199) ⫽ 453.29, p ⬍ 0.001, h2 ⫽ 0.70) than the

less powerful brand (M ⫽ 4.00). Perceptions of referent brand social power are

significantly higher (F(1,199) ⫽ 162.74, p ⬍ 0.001, h2 ⫽ 0.45) for the more power-

ful SUV (M ⫽ 4.94) as compared to the less powerful brand (M ⫽ 3.00).

104 CROSNO, FRELING, AND SKINNER

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

Covariate Analyses

Familiarity appeared to be an appropriate covariate, based on homogeneity

tests. However, correlation analyses performed with overall brand social power

and the three brand equity measures indicated that familiarity did not have a

significant impact on evaluations for any of the stimulus products. Familiarity

had a low correlation ( p’s ⬎ 0.05) with overall brand social power, brand atti-

tudes, purchase intentions, and brand equity for each of the five product cate-

gories featured in the study. Further, separate one-way ANOVAs conducted to

assess the relative impact of this potential covariate on individual product cat-

egories indicated that familiarity had a statistically non-significant influence on

key measures for each product category (see Table 2). Given the failure of famil-

iarity to impact the dependent variables, it was excluded from further analyses.

Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis 1. Support for Hypothesis 1 required the demonstration of signifi-

cantly stronger legitimate brand social power when subjects perceive a brand as

having a stronger industry position (1a), better reputation (1b), and longer dura-

tion in the industry (1c). Consistent with these expectations, significant main

effects are present for industry position (F(1,199) ⫽ 486.34, p ⬍ 0.001, h2 ⫽ 0.84);

Table 2. Impact of Familiarity on Dependent Measures by Product Category.

Dependent Measures Approx. F Sign. of F h2 Observed Power

Familiarity with automotive tires

Overall brand social power 0.96 p ⬎ 0.05 0.18 0.72

Brand attitudes 1.67 p ⬎ 0.05 0.28 0.44

Purchase intentions 1.36 p ⬎ 0.05 0.26 0.82

Brand equity 0.55 p ⬎ 0.05 0.11 0.35

Familiarity with carbonated cola beverages

Overall brand social power 1.17 p ⬎ 0.05 0.19 0.85

Brand attitudes 0.39 p ⬎ 0.05 0.04 0.20

Purchase intentions 1.04 p ⬎ 0.05 0.12 0.58

Brand equity 0.53 p ⬎ 0.05 0.06 0.27

Familiarity with computer software

Overall brand social power 1.09 p ⬎ 0.05 0.11 0.54

Brand attitudes 0.93 p ⬎ 0.05 0.09 0.46

Purchase intentions 0.12 p ⬎ 0.05 0.01 0.61

Brand equity 0.89 p ⬎ 0.05 0.06 0.37

Familiarity with sports cars

Overall brand social power 1.28 p ⬎ 0.05 0.21 0.77

Brand attitudes 1.04 p ⬎ 0.05 0.17 0.73

Purchase intentions 0.89 p ⬎ 0.05 0.16 0.57

Brand equity 1.21 p ⬎ 0.05 0.20 0.74

Familiarity with SUVs

Overall brand social power 1.04 p ⬎ 0.05 0.18 0.67

Brand attitudes 1.21 p ⬎ 0.05 0.21 0.75

Purchase intentions 1.02 p ⬎ 0.05 0.21 0.64

Brand equity 1.56 p ⬎ 0.05 0.26 0.90

DOES BRAND SOCIAL POWER MEAN MARKET MIGHT? 105

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

reputation (F(1,199) ⫽ 697.01, p ⬍ 0.001, h2 ⫽ .88); and industry duration

(F(1,199) ⫽ 338.05, p ⬍ 0.001, h2 ⫽ 0.63) in the carbonated cola beverage product cat-

egory. Brands are perceived as having significantly greater legitimate brand social

power when subjects perceive them as being superior to the competition (M ⫽ 5.74

vs. M ⫽ 2.39), having a strong, favorable reputation (M ⫽ 5.86 vs. M ⫽ 2.40), and

being well established in their respective industries (M ⫽ 5.87 vs. M ⫽ 3.50).

(Results for all hypothesis testing are presented in Table 3.)

Table 3. Summary of Hypothesis Testing.

Source of Variation Approx. F Sign. of F h2 Observed Power

H1: Legitimate brand social power

Industry position 486.34 p ⬍ 0.001 0.84 1.00

Reputation 697.01 p ⬍ 0.001 0.88 1.00

Industry duration 338.05 p ⬍ 0.01 0.63 1.00

H2: Reward brand social power

Ability to reward 117.16 p ⬍ 0.001 0.37 1.00

Value of reward 186.52 p ⬍ 0.001 0.48 1.00

H3: Coercive brand social power

Ability to punish 71.98 p ⬍ 0.001 0.27 0.99

Desire to avoid punishment 79.89 P ⬍ 0.001 0.29 0.99

H4: Expert brand social power

Brand experience/expertise 150.71 p ⬍ 0.001 0.43 1.00

Consumer knowledge 68.49 p ⬍ 0.001 0.26 0.99

H5: Referent brand social power

Similarity 145.01 p ⬍ 0.001 0.42 1.00

Source of variation Approx. F Sign. of F R2

H6: Overall brand social power

Legitimate brand social power 446.18 p ⬍ 0.001 0.69

Reward brand social power 276.85 p ⬍ 0.001 0.58

Coercive brand social power 143.61 p ⬍ 0.001 0.42

Expert brand social power 453.29 p ⬍ 0.001 0.69

Referent brand social power 162.75 p ⬍ 0.001 0.45

Overall brand social power 132.58 p ⬍ 0.001 0.43

H7: Brand equity

Legitimate brand social power (brand attitudes) 543.83 p ⬍ 0.001 0.73

Legitimate brand social power (purchase intentions) 1.12 p ⬎ 0.05 0.01

Legitimate brand social power (brand equity) 1198.29 p ⬍ 0.001 0.86

Reward brand social power (brand attitudes) 558.51 p ⬍ 0.001 0.74

Reward brand social power (purchase intentions) 16.57 p ⬍ 0.001 0.08

Reward brand social power (brand equity) 1412.32 p ⬍ 0.001 0.88

Coercive brand social power (brand attitudes) 522.37 p ⬍ 0.001 0.72

Coercive brand social power (purchase intentions) 18.56 p ⬍ 0.001 0.09

Coercive brand social power (brand equity) 1368.69 p ⬍ 0.001 0.87

Expert brand social power (brand attitudes) 405.01 p ⬍ 0.001 0.68

Expert brand social power (purchase intentions) 17.09 p ⬍ 0.001 0.08

Expert brand social power (brand equity) 1059.94 p ⬍ 0.001 0.84

Referent brand social power (brand attitudes) 526.95 p ⬍ 0.001 0.73

Referent brand social power (purchase intentions) 3.98 p ⬍ 0.05 0.02

Referent brand social power (brand equity) 1435.42 p ⬍ 0.001 0.88

106 CROSNO, FRELING, AND SKINNER

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

Hypothesis 2. Testing Hypothesis 2 entailed analyzing the impact of subjects’

perceptions regarding (a) a brand’s ability to influence rewards (F(1,199) ⫽ 117.16,

p ⬍ 0.001, h2 ⫽ 0.37) and (b) the value of those rewards (F(1,199) ⫽ 186.52,

p ⬍ 0.001, h2 ⫽ 0.48) on reward brand social power for brands in the sports car

product category. Results suggest that when subjects believe a brand can deliver

rewards (M ⫽ 5.23 vs. M ⫽ 3.50) and value is placed on those rewards (M ⫽ 6.02 vs.

M ⫽ 4.01), they regard the brand as possessing significantly greater reward

brand social power.

Hypothesis 3. As predicted by Hypothesis 3, significant main effects are pres-

ent for subjects’ perceptions regarding (a) a brand’s ability to mediate punish-

ments (F(1,199) ⫽ 71.98, p ⬍ 0.001, h2 ⫽ 0.27) and (b) subjects’ desire to avoid

punishments (F(1,199) ⫽ 79.89, p ⬍ 0.001, h2 ⫽ 0.29) in the automotive tire prod-

uct category. When subjects believe a brand can bring about undesired conse-

quences (M ⫽ 2.15 vs. M ⫽ 1.01) and they wish to avoid being punished by the

brand (M ⫽ 3.53 vs. M ⫽ 1.50), they regard the brand as possessing signifi-

cantly greater coercive brand social power.

Hypothesis 4. For insight into Hypothesis 4, which suggests significantly

stronger expert brand social power when subjects perceive a brand as possessing

knowledge and/or expertise in a given industry (4a) and as more knowledge-

able than the subjects (4b), the impact of these two factors on expert brand social

power was analyzed. Significant main effects for brand experience/knowledge

(F(1,199) ⫽ 150.71, p ⬍ 0.001, h2 ⫽ 0.43) and for subject knowledge (F(1,199) ⫽ 68.49,

p ⬍ 0.001, h2 ⫽ 0.26) in the computer software product category were found.

Brands are perceived as having significantly greater expert brand social power

when subjects regard them as possessing more industry knowledge and expe-

rience (M ⫽ 5.70 vs. M ⫽ 3.02). Further, subjects perceive expert brand social

power to be significantly greater when they possess relatively less knowledge

in the area (M ⫽ 4.74 vs. M ⫽ 2.99).

Hypothesis 5. Support for Hypothesis 5 was found by analyzing the impact

of perceived consumer–brand similarity on referent brand social power

(F(1,199) ⫽ 145.01, p ⬍ 0.001, h2 ⫽ 0.42) in the SUV product category. This analysis

showed that referent brand social power is significantly greater when subjects

perceive themselves to be similar to the brand (M ⫽ 3.98 vs. M ⫽ 2.41).

Hypothesis 6. Hypothesis 6 proposes that brands that draw on more than one

source of brand social power will possess significantly greater overall brand

social power. Testing this assertion required the evaluation of differences in

subjects’ perceptions regarding each brand social power dimension and overall

brand social power across product categories. Because previous hypothesis test-

ing implies that weaker brands in the comparison set are unlikely to possess a

distinct source of brand social power—let alone multiple power bases to exploit—

these analyses included only data for the relatively more powerful brands in

each product category (N ⫽ 101). Results from a series of regressions bore out

these predictions, revealing significant differences in ratings for each brand social

power dimension and overall brand social power: legitimate brand social

power (F(4, 96) ⫽ 446.18, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.69); reward brand social power

(F(4,96) ⫽ 276.85, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.58); coercive brand social power (F(4,96) ⫽ 143.61,

DOES BRAND SOCIAL POWER MEAN MARKET MIGHT? 107

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

Table 4. Mean Brand Social Power Dimension Ratings by Product Category.

Carbonated Sport

Automotive Cola Computer Sports Utility

Tires Beverages Software Cars Vehicles

Legitimacy 3.97 5.82 6.06 4.09 4.57

Reward 3.94 3.87 4.99 5.62 4.09

Coercion 2.84 2.01 3.36 2.04 2.15

Expertise 4.49 3.96 5.22 4.09 4.07

Reference 3.45 3.98 5.12 3.53 3.98

Overall 3.63 3.89 5.15 3.76 3.65

p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.42); expert brand social power (F(4,96) ⫽ 453.29, p ⬍ 0.001,

R2 ⫽ 0.69); referent brand social power (F(4,96) ⫽ 162.75, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.45);

and overall brand social power (F(4,96) ⫽ 132.58, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.43). Mean

brand social power ratings (see Table 4) suggest subjects perceive the computer

software brand as most powerful across product categories on four of five brand

social power dimensions, which in turn appears to confer greater overall brand

social power on this brand.

Hypothesis 7. Hypothesis 7 suggests that brands possessing greater overall

brand social power will also exhibit stronger brand equity. To test this premise,

a series of regression analyses was conducted for each set of brands evaluated

by participants. Brand attitudes, purchase intentions, and the overall brand

equity measure served as dependent variables for these analyses.

The overall brand social power of stimulus products in the carbonated cola

beverage category had a significant main effect on two of the three brand equity

indicators: brand attitudes (F(1,199) ⫽ 548.83, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.73); purchase inten-

tions (F(1,199) ⫽ 1.12, p ⬎ 0.05, R2 ⫽ 0.01); and brand equity (F(1,199) ⫽ 1198.29,

p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.86). When participants perceive a brand as possessing greater

brand social power, they also hold significantly more favorable brand attitudes

(M ⫽ 5.69 vs. M ⫽ 3.54) and regard the brand as having significantly higher

brand equity (M ⫽ 4.60 vs. M ⫽ 2.70). The same pattern of results holds true for

purchase intentions (M ⫽ 2.41 vs. M ⫽ 1.23), although differences on this meas-

ure fail to achieve significance for the carbonated cola beverage category.

The overall brand social power of stimulus products in the automotive tire cat-

egory had a significant main effect on all three brand equity measures: brand

attitudes (F(1,199) ⫽ 522.37, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.72); purchase intentions

(F(1,199) ⫽ 18.56, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.09); and brand equity (F(1,199) ⫽ 1368.69,

p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.87). Perceptions of greater brand social power for automotive

tires corresponds to significantly more favorable brand attitudes (M ⫽ 5.42 vs.

M ⫽ 3.25), purchase intentions (M ⫽ 3.18 vs. M ⫽ 1.45), and brand equity

(M ⫽ 4.38 vs. M ⫽ 2.30).

The overall brand social power of stimulus products in the sports car category

had a significant main effect on all three brand equity measures: brand atti-

tudes (F(1,199) ⫽ 558.51, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.74); purchase intentions (F(1,199) ⫽ 16.57,

p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.08); and brand equity (F(1,199) ⫽ 1412.32, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.88).

When subjects perceive a sports car as being a powerful brand, the brand atti-

tudes (M ⫽ 6.07 vs. M ⫽ 4.05), purchase intentions (M ⫽ 3.61 vs. M ⫽ 1.80),

and brand equity (M ⫽ 4.95 vs. M ⫽ 2.30) it elicits are also significantly higher.

108 CROSNO, FRELING, AND SKINNER

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

The overall brand social power of stimulus products in the sport utility vehi-

cle category had a significant main effect on all three brand equity measures:

brand attitudes (F(1,199) ⫽ 526.95, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.73); purchase intentions

(F(1,199) ⫽ 3.98, p ⬍ 0.05, R2 ⫽ 0.02); and brand equity (F(1,199) ⫽ 1435.42, p ⬍ 0.001,

R2 ⫽ 0.88). Perceptions of greater brand social power for SUVs are related to sig-

nificantly more favorable brand attitudes (M ⫽ 5.05 vs. M ⫽ 3.03), purchase inten-

tions (M ⫽ 3.97 vs. M ⫽ 1.81), and brand equity (M ⫽ 4.17 vs. M ⫽ 2.18).

The overall brand social power of stimulus products in the computer soft-

ware category had a significant main effect on all three brand equity measures:

brand attitudes (F(1,199) ⫽ 405.01, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.68); purchase intentions

(F(1,199) ⫽ 17.09, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.08); and brand equity (F(1,199) ⫽ 1059.94,

p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.84). When subjects perceive computer software as possessing

greater brand social power, they also hold significantly higher brand attitudes

(M ⫽ 5.89 vs. M ⫽ 3.81), purchase intentions (M ⫽ 1.67 vs. M ⫽ 0.70), and brand

equity (M ⫽ 5.52 vs. M ⫽ 3.31) for the brand.

Ancillary Analyses

No predictions were offered regarding the differential impact of individual power

bases on consumers’ corresponding brand attitudes. However, given the dis-

parate nature of the five dimensions of brand social power, it was interesting to

explore how, if at all, brand attitudes varied for brands drawing power from dif-

ferent sources. To explore these nuances of brand social power, consumers’ rat-

ings for each brand’s five brand social power dimensions were regressed on their

attitudes toward the brand. (Results for these ancillary analyses appear in

Table 5.) Interestingly, coercive brand social power is the only dimension that

fails to produce significantly more favorable brand attitudes for a majority of

brands studied. The only exception to this pattern of results obtains for the

automotive tire product category, which contained a brand purposely selected

for inclusion in the study because it reflected coercive brand social power.

For the carbonated cola beverage category, greater perceived legitimate brand

social power (F(1,99) ⫽ 128.90, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.56); reward brand social power

(F(1,99) ⫽ 70.66, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.42); expert brand social power (F(1,99) ⫽ 162.61,

p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.62); and referent brand social power (F(1,99) ⫽ 123.15, p ⬍ 0.001,

R2 ⫽ 0.55) lead to significantly greater brand attitudes. However, greater per-

ceived coercive brand social power (F(1,99) ⫽ 1.84, p ⬎ 0.05, R2 ⫽ 0.07) is not sig-

nificantly related to brand attitudes.

When participants perceive computer software as possessing greater legiti-

mate brand social power (F(1,99) ⫽ 34.28, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.26); reward brand

social power (F(1,99) ⫽ 15.88, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.14); expert brand social power

(F(1,99) ⫽ 111.76, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.53); or referent brand social power

(F(1,99) ⫽ 62.20, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.39), they also hold significantly more favor-

able attitudes toward the brand. However, the relationship between coercive

brand social power (F(1,99) ⫽ 2.14, p ⬎ 0.05, R2 ⫽ 0.02) and brand attitudes fails

to achieve significance.

For sports cars, perceptions of greater legitimate brand social power

(F(1,99) ⫽ 47.04, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.32); reward brand social power (F(1,99) ⫽ 26.67,

p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.21); expert brand social power (F(1,99) ⫽ 32.26, p ⬍ 0.001,

R2 ⫽ 0.25); and referent brand social power (F(1,99) ⫽ 50.69, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.34)

correspond to significantly more favorable brand attitudes. However, greater

DOES BRAND SOCIAL POWER MEAN MARKET MIGHT? 109

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

Table 5. Impact of Brand Social Power Dimensions on Brand Attitudes by

Product Category

Source of Variation Approx. F Sign. of F R2

Automotive tires

Legitimate brand social power 65.35 p ⬍ 0.001 0.40

Reward brand social power 26.43 p ⬍ 0.01 0.21

Coercive brand social power 5.96 p ⬍ 0.05 0.06

Expert brand social power 49.73 p ⬍ 0.001 0.33

Referent brand social power 63.35 p ⬍ 0.001 0.39

Carbonated cola beverages

Legitimate brand social power 128.90 p ⬍ 0.001 0.56

Reward brand social power 70.66 p ⬍ 0.001 0.42

Coercive brand social power 1.84 p ⬎ 0.05 0.07

Expert brand social power 162.61 p ⬍ 0.001 0.62

Referent brand social power 123.15 p ⬍ 0.001 0.55

Computer software

Legitimate brand social power 34.28 p ⬍ 0.001 0.26

Reward brand social power 15.88 p ⬍ 0.001 0.14

Coercive brand social power 2.14 p ⬎ 0.05 0.02

Expert brand social power 111.76 p ⬍ 0.001 0.53

Referent brand social power 62.20 p ⬍ 0.001 0.39

Sports cars

Legitimate brand social power 47.04 p ⬍ 0.001 0.32

Reward brand social power 26.67 p ⬍ 0.001 0.21

Coercive brand social power 1.83 p ⬎ 0.05 0.03

Expert brand social power 32.26 p ⬍ 0.001 0.25

Referent brand social power 50.69 p ⬍ 0.001 0.34

SUVs

Legitimate brand social power 139.09 p ⬍ 0.001 0.58

Reward brand social power 76.35 p ⬍ 0.001 0.44

Coercive brand social power 1.69 p ⬎ 0.05 0.04

Expert brand social power 124.71 p ⬍ 0.001 0.56

Referent brand social power 153.88 p ⬍ 0.001 0.61

perceived coercive brand social power (F(1,99) ⫽ 1.83, p ⬎ 0.05, R2 ⫽ 0.03) is not

significantly related to brand attitudes.

When subjects perceive an SUV as being a powerful brand in terms of legit-

imacy (F(1,99) ⫽ 139.09, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.58); reward (F(1,99) ⫽ 76.35, p ⬍ 0.001,

R2 ⫽ 0.44); expertise (F(1,99) ⫽ 124.71, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.56); or referent brand

social power (F(1,99) ⫽ 153.88, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.61), the brand attitudes it elic-

its are also significantly higher. However, perceptions of greater coercive brand

social power for an SUV (F(1,99) ⫽ 1.69, p ⬎ 0.05, R2 ⫽ 0.04) are not related to sig-

nificantly more favorable brand attitudes.

For the automotive tire category, greater perceived legitimate brand social

power (F(1,99) ⫽ 128.90, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.56); reward brand social power

(F(1,99) ⫽ 70.66, p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.42); expert brand social power (F(1,99) ⫽ 162.61,

p ⬍ 0.001, R2 ⫽ 0.62); referent brand social power (F(1,99) ⫽ 123.15, p ⬍ 0.001,

R2 ⫽ 0.55); and coercive brand social power (F(1,99) ⫽ 5.96, p ⬍ 0.05, R2 ⫽ 0.06)

lead to significantly greater brand attitudes.

110 CROSNO, FRELING, AND SKINNER

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

DISCUSSION

The objective of this research was to develop a preliminary framework of brand

social power that would enable investigators to delineate the dimensions of the

construct, assess how these individual power bases influence overall brand social

power, and examine the relationship between overall brand social power and

brand equity (including brand attitudes). Drawing on seminal work in the area

of social power and influence theory, brand social power was defined as the ability

of a brand to influence the behavior of consumers and conceptualized as pos-

sessing five dimensions analogous to French and Raven’s (1959) original bases

of social power. Legitimate brand social power, reward brand social power, coer-

cive brand social power, expert brand social power, and referent brand social

power were theoretically dissected, and indicators of each power base were iden-

tified. In a study featuring brands from an assortment of product categories with

varying levels and types of brand social power, each dimension was empirically

examined, and results demonstrate that (1) a brand wielding any one brand

social power dimension will have greater overall brand social power than a com-

parable (but less powerful) brand in the same product category; (2) brands pos-

sessing more than one brand social power dimension will have greater overall

brand social power than other brands (within and across product categories) that

possess one or no bases of brand social power; and (3) brands emitting greater

overall brand social power will also possess greater brand equity.

This analysis reveals strong empirical support for theoretical assertions put

forth here regarding the constituent elements of brand social power’s construct.

Consumers view a brand as possessing legitimate brand social power when it

has high market share, a strong, favorable reputation, and a well-established

industry presence. Reward brand social power is stronger when consumers believe

a brand can reward them and those rewards are considered to be valuable. Coer-

cive brand social power is thought to exist when consumers believe the brand can

punish them and they wish to avoid the brand’s punishment. When a brand is

associated with greater knowledge and/or expertise in a given industry than

competitors or consumers, it is regarded as having expert brand social power. A

final dimension, referent brand social power, is present in brands which con-

sumers believe they are similar to in some way. These findings contribute to a bet-

ter conceptual understanding of the individual dimensions of brand social power.

Interestingly, subjects in this study perceived many stimulus products as

possessing not one, but multiple dimensions of brand social power—even when

a single, distinct base of brand social power was manipulated. For instance, a

majority of subjects evaluating products in the SUV category regarded the more

powerful brand as possessing predominantly referent brand social power, with

traces of reward brand social power. This observation implies an unforeseen

complexity of the brand social power construct, and suggests that—given brand

social power’s capacity to influence consumer reactions to a given brand—

marketers must be mindful of the potential for consumers to derive unintended

conclusions about the nature of a brand’s power from marketing communications

and through product usage experience.

This research also sheds light on the collective influence that individual brand

social power dimensions may exert on a brand’s overall power and equity. Results

reported here suggest that overall brand social power is greater when a brand

has multiple bases of power from which to draw. For example, Microsoft (which

DOES BRAND SOCIAL POWER MEAN MARKET MIGHT? 111

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

was included because pretest results indicated consumers regard it as reflective

of a brand with expert brand social power) received significantly higher ratings

than all other brands across product categories on expert brand social power, ref-

erent brand social power, legitimate brand social power, and coercive brand

social power. As a result, subjects also perceive Microsoft as possessing greater

overall brand social power.

Further, greater brand equity accrues to brands possessing stronger overall

brand social power. More specifically, brands consumers regard as more power-

ful also elicit more favorable brand attitudes and possess greater overall brand

equity. However, contrary to predictions, in some cases consumers’ purchase

intentions are not necessarily stronger for more powerful brands. For carbon-

ated cola beverages, there are no significant differences in purchase intentions

for more vs. less powerful brands. It is useful to reflect on this deviation from expec-

tations, because it appears to contradict the very essence of brand social power—

the ability to influence consumer behavior. One explanation for this surprising

result may hinge upon the decision to examine brands in this particular product

category (i.e., carbonated cola beverages), which is admittedly characterized by

strong, resolute brand preferences. This product category was included because

extensive pretesting suggested subjects were sufficiently familiar with its mul-

tiple competitors and purportedly perceived substantial intra-categorical variance

in legitimate brand social power. However, it is conceivable that an enthusiastic

Pepsi drinker may acknowledge Coca-Cola as relatively more powerful than a third

brand, hold more relatively favorable brand attitudes toward Coke, and even

rate it relatively higher on overall brand equity—but still have no intention of

purchasing Coke due to his or her steadfast commitment to Pepsi-Cola. This

interpretation may explicate the significant results for purchase intentions in

other product categories (automotive tires, sports cars, SUVs, and computer

software), which operate in less concentrated industries comprised of more numer-

ous and comparable competitors that seemingly inspire less loyalty among

consumers.

Implications

Although predictions offered here regarding the relationship between brand social

power and purchase intentions fail to receive unanimous support, it is worth not-

ing that for a majority of product categories examined—computer software, sports

cars, SUVs, and automotive tires—perceptions of strong brand social power on the

manipulated dimension were associated with greater purchase intentions for

the target brand. This finding validates the assertion that brands have the capac-

ity to influence consumer behavior, substantiating the existence of brand social

power and justifying the application of French and Raven’s (1959) power typology

in a branding context. And in a broader sense, the association between brand social

power and purchase intentions documented here constitutes unambiguous, albeit

limited, evidence that individuals (consumers) develop attitudes toward objects

(brands) that elicit evaluative responses, which are behavioral in nature. Although

this finding will not likely resolve differing opinions regarding the validity of tri-

partite attitude models, it does suggest that conation—arguably the most empiri-

cally problematic of the three components—is a legitimate attitudinal response.

Aside from this theoretical contribution to modern attitude theory, findings

described here also have several practical implications for branding strategy. Most

112 CROSNO, FRELING, AND SKINNER

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

notably, knowledge of brand social power can be used to segment markets and to

differentiate one brand from its competitors. Given that brands have the poten-

tial to satisfy different social needs of consumers (e.g., the desire to achieve rewards,