Criminal Procedure - Indictment - Bill of Particulars

Diunggah oleh

NecandiHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Criminal Procedure - Indictment - Bill of Particulars

Diunggah oleh

NecandiHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

http://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?

article=2284&context=lalrev

Louisiana Law Review

Volume 15 | Number 4

June 1955

Criminal Procedure - Indictment - Bill of Particulars

Maynard E. Cush

Repository Citation

Maynard E. Cush, Criminal Procedure - Indictment - Bill of Particulars, 15 La. L. Rev. (1955)

Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol15/iss4/19

This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at DigitalCommons @ LSU Law Center. It has been accepted for

inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons @ LSU Law Center. For more information, please contact

sarah.buras@law.lsu.edu.

LOUISIANA LAW REVIEW

(VOL. XV

CRnIINAL PROCEDURE-INDICTMENT-BILL OF PARTICULARS

Defendant was charged with having committed "aggravated

burglary of the inhabited dwelling [of certain named persons]

with intent to commit a theft and forcible felony therein, while

armed with a dangerous weapon, to-wit: a sharp instrument."

The indictment also charged, in the same count, that, while in

the dwelling, defendant "did commit an aggravated battery with

said sharp instrument [upon a named woman] and did commit

a battery [upon the same woman] with a personal part of his

body."' Defendant requested a bill of particulars concerning the

forcible felony which he allegedly intended to commit when he

entered the building. The trial court sustained the state's refusal

to furnish this information. On appeal, held, affirmed. The defendant was adequately informed of the nature of the forcible

felony which he allegedly intended to commit by the statement

in the bill of information that he had committed an aggravated

battery while in the building. State v. O'Brien, 77 So.2d 402 (La.

1955).

Article 235 of the Louisiana Code of Criminal Procedure

provides that the following form of indictment 2 is sufficient to

charge the crime of aggravated burglary: "A.B. committed aggravated burglary of the dwelling of C.D." The article permits

the addition of a more particularized statement of the offense to

this short form. Since the defendant is entitled to know the

nature of the charge against him, 3 the article provides that the

judge may require the state to grant the defendant a bill of particulars setting forth more specifically the nature of the crime

charged. Although the Supreme Court has stated that this provision should be interpreted "liberally," 4 the granting or refusing

of a bill of particulars rests largely in the discretion of the trial

judge and few convictions have been reversed because the bill

of particulars supplementing a short form indictment was refused

or, if granted, was inadequate. 5 A bill of particulars may also be

1.

2.

15:216

3.

4.

State v. O'Brien, 77 So.2d 402, 403 (La. 1955).

The term "indictment" includes bills of information. See LA. R.S.

(1950).

This right is guaranteed the defendant by LA. CONST. art. I, 10.

State v. Brooks, 173 La. 9, 136 So. 71 (1931).

5. Only one reversal was found: State v. Holmes, 223 La. 397, 65 So.2d

890 (1953),

1955]

NOTES

obtained by the accused when the indictment against him is in

the more detailed long form."

Defendant in the instant case first contended that the bill of

information was defective, in that it charged him with the commission of several offenses in one count, presumably aggravated

burglary and two batteries. The court disposed of this contention

by referring to article 222 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.

That article permits the conjunctive cumulation in one count of

several offenses "disjunctively enumerated in the same law or in

the same section of a criminal statute . . .when it appears that

they are connected with the same transaction and constitute but

one act." The court concluded that the bill of information satisfied these requirements. 7 The court could also have found authority for treating the charges that defendant committed two batteries after entering the building as mere attempts to show the

intent with which he entered.8 This would have been similar to

the approach taken by the court in disposing of the principal

question in the case, concerning defendant's right to a bill of

particulars describing the forcible felony which the information

charged he intended to commit upon entering. The court in this

connection held that the charge in the information that defendant

committed an aggravated battery while in the dwelling "described in detail in just so many words"9 the nature of the forcible felony which defendant entered with the intention to

commit.

The court's holding that defendant knew he was charged

with intending to commit aggravated battery before entering the

building, simply because he was charged with having committed

that crime after entering, seems questionable. As a matter of

fact, the information also charged that, after entering the building, he committed a second battery, upon a woman, "with a

personal part of his body." This allegation could as well be said

to describe "in detail in just so many words" an intent upon

entering to commit rape. It is doubtful that an accused's right to

6. State v. De Arman, 153 La. 345, 95 So. 803 (1923); State v.

La. 513, 53 So. 737 (1910); State v. Clark, 124 La. 965, 50 So. 811

also Comment, 12 LouISIANA LAW REVIEW 457, 458 (1952).

7. Article 60 of the Criminal Code, which defines the crime of

burglary, lists disjunctively the commission of a battery while in

Selsor, 127

(1909). See

aggravated

a dwelling

as one form of an essential element of the crime. The court stated that the

offenses charged were connected with the same transaction and constituted

but one act.

8. State v. Desselles, 150 La. 494, 90 So. 773 (1922).

9. State v. O'Brien, 77 So.2d 402, 404 (La. 1955).

832

LOUISIANA LAW REVIEW

[VOL. XV

be informed of the nature of the charges against him should be

satisfied by such subtle implications in an indictment. Little

more justification for the state's refusal to grant defendant a bill

of particulars as to the intended forcible felony can be found in

the court's suggestion that this portion of the information could

be disregarded as surplusage, since the charge that he intended

to commit theft was sufficient. The accused was charged and

tried under an information charging dual intents and was refused

particulars as to one of them. If the fact that an information is

valid means that the defendant's right to a bill of particulars

has been satisfied, then the bill of particulars serves no useful

purpose in Louisiana criminal procedure.

Maynard E. Cush

FEDERAL PRACTICE-JURISDICTION-LOUISIANA

STATUTE,

WATERCRAFT

LA. R.S. 13:3479 (1950)

Plaintiff, widow of a Louisiana resident killed while working

as a ship repairman on a British steamer docked in New Orleans,

brought suit in federal district court 1 under article 2315 of the

Louisiana Civil Code 2 to recover damages for his alleged wrongful death. Service of process was made pursuant to the Louisiana Watercraft Statute, La. R.S. 13:3479, providing, in substance,

for service of process on the Secretary of State in actions against

nonresidents growing out of any accident arising from the nonresident's operation, navigation, or maintenance of watercraft in

1. The modes of service of process in federal courts are provided in the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Following is the pertinent provision of

Rule 4:

"(d) Summons: Personal Service. The summons and complaint shall be

served together. The plaintiff shall furnish the person making the service

with such copies as are necessary. Service shall be made as follows:

"(7) Upon a defendant of any class referred to in paragraph (1) or (3)

of this subdivision of this rule, it is also sufficient if the summons and complaint are served in the manner prescribed by any statute of the United

States or in the manner prescribed by the law of the state in which the

service is made for the service of summons or other like process upon any

such defendant in an action brought in the courts of general jurisdiction of

that State." (Emphasis added.) FED. R. Civ. P. 4(d)(7).

2. It is not within the limited scope of this note to consider the constitutionality of LA. R.S. 13:3479 (1950) as applied to a case arising under the

Jones Act, 38 STAT. 1185 (1915), as amended, 46 U.S.C. 688 (1952), instead of

Art. 2315, LA. CIVIL CODE of 1870.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Berger A. Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law.Dokumen479 halamanBerger A. Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law.shliman100% (4)

- Alan Gilpin - Dictionary of Environmental Law-Edward Elgar Publishing (2001) PDFDokumen392 halamanAlan Gilpin - Dictionary of Environmental Law-Edward Elgar Publishing (2001) PDFNaomy ChristianiBelum ada peringkat

- 4RogerWilliamsULRev678 PDFDokumen38 halaman4RogerWilliamsULRev678 PDFNecandiBelum ada peringkat

- Treatise On The Law Governing Indictments With Forms PDFDokumen67 halamanTreatise On The Law Governing Indictments With Forms PDFNecandiBelum ada peringkat

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDokumen15 halaman6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDokumen15 halaman6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Anabolic Pharmacology SethRoberts 2009Dokumen428 halamanAnabolic Pharmacology SethRoberts 2009PoopBelum ada peringkat

- Bobbio, Norberto. A Era Dos Direitos.Dokumen7 halamanBobbio, Norberto. A Era Dos Direitos.NecandiBelum ada peringkat

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDokumen15 halaman6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Anabolic Pharmacology SethRoberts 2009Dokumen428 halamanAnabolic Pharmacology SethRoberts 2009PoopBelum ada peringkat

- Unintelligible Indictment: People of The State of Illinois, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. William J. West, Defendant-AppellantDokumen3 halamanUnintelligible Indictment: People of The State of Illinois, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. William J. West, Defendant-AppellantNecandiBelum ada peringkat

- Aba Standards For Criminal JusticeDokumen296 halamanAba Standards For Criminal JusticeNecandi100% (1)

- Logic and LawDokumen9 halamanLogic and LawNecandiBelum ada peringkat

- The Bill of Rights As A Code of Criminal Procedure PDFDokumen29 halamanThe Bill of Rights As A Code of Criminal Procedure PDFNecandiBelum ada peringkat

- Anabolic Pharmacology SethRoberts 2009Dokumen428 halamanAnabolic Pharmacology SethRoberts 2009PoopBelum ada peringkat

- Four Models of The Criminal ProcessDokumen47 halamanFour Models of The Criminal ProcesssemarangBelum ada peringkat

- Additional Research To Assess The Impact of Potentially Changing The Scope (Art. 3) of The Regulation On Information Accompanying Transfers of FundsDokumen25 halamanAdditional Research To Assess The Impact of Potentially Changing The Scope (Art. 3) of The Regulation On Information Accompanying Transfers of FundsNecandiBelum ada peringkat

- Yaroshefsky, Ellen. New Perspectives On Brady and Other Disclosure Obligations - What Really Works.Dokumen93 halamanYaroshefsky, Ellen. New Perspectives On Brady and Other Disclosure Obligations - What Really Works.NecandiBelum ada peringkat

- MILLAR, Robert Wyness. Premises of The Judgment As Res Judicata in Continental and Anglo-American Law. MICHIGAN LAW REVIEW. v. 39. Fasc. 1. Nov - 1940. Pp. 1-36.Dokumen37 halamanMILLAR, Robert Wyness. Premises of The Judgment As Res Judicata in Continental and Anglo-American Law. MICHIGAN LAW REVIEW. v. 39. Fasc. 1. Nov - 1940. Pp. 1-36.Necandi100% (1)

- GRIFFITHS, John. Ideology in Criminal Procedure or A Third Model of The Criminal Process. YALE LAW JOURNAL. v. 79. Fas. 3. Jan - 1970. Pp. 359-417..Dokumen60 halamanGRIFFITHS, John. Ideology in Criminal Procedure or A Third Model of The Criminal Process. YALE LAW JOURNAL. v. 79. Fas. 3. Jan - 1970. Pp. 359-417..NecandiBelum ada peringkat

- Yaroshefsky, Ellen. New Perspectives On Brady and Other Disclosure Obligations - What Really Works.Dokumen93 halamanYaroshefsky, Ellen. New Perspectives On Brady and Other Disclosure Obligations - What Really Works.NecandiBelum ada peringkat

- AMODIO, Ennio SELVAGGI, Eugenio. Accusatorial System in A Civil Law Country - The 1988 Italian Code of Criminal Procedure. TEMPLE LAW REVIEW. v. 62. 1989. P. 1211 PDFDokumen15 halamanAMODIO, Ennio SELVAGGI, Eugenio. Accusatorial System in A Civil Law Country - The 1988 Italian Code of Criminal Procedure. TEMPLE LAW REVIEW. v. 62. 1989. P. 1211 PDFNecandiBelum ada peringkat

- Best Practices Paper On Special Recommendation IIIDokumen14 halamanBest Practices Paper On Special Recommendation IIINecandiBelum ada peringkat

- Eletronic Discovery and EvidenceDokumen7 halamanEletronic Discovery and EvidenceNecandiBelum ada peringkat

- GOLDSTEIN, Abraham S. Reflections On Two Models - Inquisitorial Themes in American Criminal Procedure. STANFORD LAW REVIEW. N. 26, P. 1009, Maio - 194.Dokumen19 halamanGOLDSTEIN, Abraham S. Reflections On Two Models - Inquisitorial Themes in American Criminal Procedure. STANFORD LAW REVIEW. N. 26, P. 1009, Maio - 194.NecandiBelum ada peringkat

- An Introduction To The FATF and Its WorkDokumen6 halamanAn Introduction To The FATF and Its WorkShashikant PrajapatiBelum ada peringkat

- Yaroshefsky, Ellen. Prosecutorial Disclosure Obligations.Dokumen29 halamanYaroshefsky, Ellen. Prosecutorial Disclosure Obligations.NecandiBelum ada peringkat

- YEE, Ellen Liang. Forfeiture of The Confrontation Right in Giles - Justice Scalia's Faint-Hearted Fidelity To The Common Law. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology PDFDokumen45 halamanYEE, Ellen Liang. Forfeiture of The Confrontation Right in Giles - Justice Scalia's Faint-Hearted Fidelity To The Common Law. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology PDFNecandiBelum ada peringkat

- Deutsche Bank Group - Anti Money Laundering PolicyDokumen7 halamanDeutsche Bank Group - Anti Money Laundering PolicycheejustinBelum ada peringkat

- Wigmore, John Henry. The Principles of Judicial Proof.Dokumen1.228 halamanWigmore, John Henry. The Principles of Judicial Proof.Necandi100% (2)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- 3 Crime and CriminalsDokumen5 halaman3 Crime and CriminalsegvrgvBelum ada peringkat

- People vs. Domasian Case BriefDokumen2 halamanPeople vs. Domasian Case BriefBrian Balio100% (3)

- Reyes vs. AlejandroDokumen1 halamanReyes vs. AlejandrosikarlBelum ada peringkat

- Philippine School Business Admin. v. CADokumen1 halamanPhilippine School Business Admin. v. CAPia Janine ContrerasBelum ada peringkat

- 2020/21 LMT in Legal EthicsDokumen5 halaman2020/21 LMT in Legal EthicsKiko OralloBelum ada peringkat

- Impartial Decisions on Challenges to ArbitratorsDokumen4 halamanImpartial Decisions on Challenges to ArbitratorsVIKASH KUMAR BAIRAGI100% (1)

- Micro Distribution Agreement (Dist. and MD Entrep)Dokumen6 halamanMicro Distribution Agreement (Dist. and MD Entrep)joeBelum ada peringkat

- C4C Upload of The U.S. EEOC Management Directive 110Dokumen358 halamanC4C Upload of The U.S. EEOC Management Directive 110C4CBelum ada peringkat

- Perez V MadronaDokumen8 halamanPerez V MadronaaiceljoyBelum ada peringkat

- Recusal Disqualification of Judges and LawyersDokumen41 halamanRecusal Disqualification of Judges and Lawyersjbdage100% (2)

- Manila International Airport Authority vs. Avia Filipinas International, IncDokumen2 halamanManila International Airport Authority vs. Avia Filipinas International, IncRachel Anne Baroja100% (1)

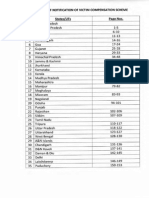

- Victim Compensation Scheme of States UTs in India.Dokumen154 halamanVictim Compensation Scheme of States UTs in India.Latest Laws TeamBelum ada peringkat

- Zaiger Motion For Attorney Fees Denied - Monsarrat V Zaiger/Encyclopedia DramaticaDokumen2 halamanZaiger Motion For Attorney Fees Denied - Monsarrat V Zaiger/Encyclopedia DramaticaSusanBaskoBelum ada peringkat

- Franchise FraudDokumen3 halamanFranchise FraudSumeet KPBelum ada peringkat

- Abercrombie & Fitch v. Hunting World trademark caseDokumen2 halamanAbercrombie & Fitch v. Hunting World trademark caseGenevieve Kristine ManalacBelum ada peringkat

- Nick Rhoades Vs State of IowaDokumen60 halamanNick Rhoades Vs State of IowaSergio Nahuel CandidoBelum ada peringkat

- Mercantile Law ReviewerDokumen226 halamanMercantile Law ReviewerMelody BangsaludBelum ada peringkat

- Buslaw 1: de La Salle University Comlaw DepartmentDokumen33 halamanBuslaw 1: de La Salle University Comlaw DepartmentGasper BrookBelum ada peringkat

- V. Thrival - Complaint (Sans Exhibits)Dokumen45 halamanV. Thrival - Complaint (Sans Exhibits)Sarah BursteinBelum ada peringkat

- Form No 33, Surety Letter, Consent Letter, Letter of IndemnityDokumen7 halamanForm No 33, Surety Letter, Consent Letter, Letter of IndemnitySankar Nath ChakrabortyBelum ada peringkat

- Export Contract - FinalDokumen4 halamanExport Contract - FinalAnonymous GAulxiI100% (1)

- Case 17 Nik Mahmud V BimbDokumen14 halamanCase 17 Nik Mahmud V BimbFirdaus DarkozzBelum ada peringkat

- Nicolas vs. Romulo: FactsDokumen9 halamanNicolas vs. Romulo: FactsJf ManejaBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding Actionable Claims Under The Transfer Of Property ActDokumen3 halamanUnderstanding Actionable Claims Under The Transfer Of Property ActAniket SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Ramones vs. Spouses GuimocDokumen10 halamanRamones vs. Spouses GuimocEmir MendozaBelum ada peringkat

- Criminal Law 2 LECTURENOTES 2 - WPS OfficeDokumen21 halamanCriminal Law 2 LECTURENOTES 2 - WPS OfficeZephaniah BoocBelum ada peringkat

- Crim Pro CasesDokumen48 halamanCrim Pro CasesFaith Imee Roble100% (1)

- De Los Reyes vs. Municipality of Kalibo FactsDokumen4 halamanDe Los Reyes vs. Municipality of Kalibo FactsVan John MagallanesBelum ada peringkat

- Criminal Law Essay On Consent For StuDocUDokumen4 halamanCriminal Law Essay On Consent For StuDocUCarolin BrowneBelum ada peringkat

- Latin Legal MaximsDokumen4 halamanLatin Legal MaximsJoaquin Javier BalceBelum ada peringkat