Workers Perceptions of Workplace Safety and Job Satisfaction

Diunggah oleh

Norazela HamadanHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Workers Perceptions of Workplace Safety and Job Satisfaction

Diunggah oleh

Norazela HamadanHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

International Journal of Occupational Safety and

Ergonomics

ISSN: 1080-3548 (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tose20

Workers Perceptions of Workplace Safety and Job

Satisfaction

Seth Ayim Gyekye

To cite this article: Seth Ayim Gyekye (2005) Workers Perceptions of Workplace Safety and Job

Satisfaction, International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 11:3, 291-302, DOI:

10.1080/10803548.2005.11076650

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2005.11076650

Published online: 08 Jan 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 1768

View related articles

Citing articles: 2 View citing articles

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tose20

Download by: [64.62.219.84]

Date: 14 May 2016, At: 02:28

International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics (JOSE) 2005, Vol. 11, No. 3, 291302

Workers Perceptions of Workplace Safety

and Job Satisfaction

Seth Ayim Gyekye

Downloaded by [64.62.219.84] at 02:28 14 May 2016

Department of Social Psychology, University of Helsinki, Finland

A lot of attention has been focused on workers perceptions of workplace safety but relatively little or no research

has been done on the impact of job satisfaction on safety climate. This study investigated this relationship. It also

examined the relationships between job satisfaction and workers compliance with safety management policies

and accident frequency. A positive association was found between job satisfaction and safety climate. Workers

who expressed more satisfaction at their posts had positive perceptions of safety climate. Correspondingly,

they were more committed to safety management policies and consequently registered a lower rate of accident

involvement. The results were thus consistent with the notion that workers positive perceptions of organisational

climate influence their perceptions of safety at the workplace. The findings, which have implications in the work

environment, are discussed.

perception

organisational safety climate job satisfaction

safety perception accident frequency

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Organisational Climate

In the literature organisational climate refers to the

shared perceptions about organisational values,

norms, beliefs, practices and procedures [1, 2,

3, 4, 5]. It denotes the social and organisational

circumstances in which workers perform their

assignments. The climate of an organisation has

been known to be an important antecedent of

workplace performance as workers perceptions of

the state of affairs and structures in place in their

organisations have affected their perceptions of

safety [4, 5] and work behaviour [6]. According

to research reports, perceptions of organisational

climate tend to influence interactions among

workers [7, 8], shape their affective responses to

the work environment [Hart, Wearing, Griffin, as

cited in 4, 9], affect their levels of motivation [10]

and their skill training activities [Morrison, Upton,

Cordery, as cited in 11]. Regarding the relationship

safety management

between safety climate and safety perception, safety

experts, e.g., Neal et al. [4] and Silva et al. [5], who

have investigated this relationship have confirmed

that organisational climate predicts safety climate,

which in turn is related to safety performance

(p. 206) [5]. Essentially, what these studies have

revealed is that the general organisational climate

in a work environment imparts significant influence

on safety climate, which in turn affects workers

safety behaviour, and subsequently, their accident

involvement.

1.2. Safety Climate

The safety literature defines safety climate as a

coherent set of perceptions and expectations that

workers have regarding safety in their organisation

[4, 8, 12, 13]. It is considered as a subset of

organisational climate [8]. Workers perceptions

of safety climate have been regarded as a principal

guide to safety performance, which provides a

potent proactive management tool. Consistent

with this observation, researchers have noted that

Correspondence and requests for offprints should be sent to Seth Ayim Gyekye, Department of Social Psychology, University of

Helsinki, Unioninkatu 37, 00014 Helsinki, Finland. E-mail: <gyekye@mappi.helsinki.fi>.

Downloaded by [64.62.219.84] at 02:28 14 May 2016

292 S.A. GYEKYE

workers with a negative perception of safety

climate (e.g., a high workload, work pressure)

tend to engage in unsafe acts, which in turn

increase their susceptibility to accidents [14, 15].

Similarly, workers who perceive job insecurity,

anxiety and stress have exhibited a drop in safety

motivation and compliance [16, 17] and recorded

a higher accident rate [18, 19, 20]. On the other

hand, workers with a positive perception of their

workplace safety have registered fewer accidents

[14, 21, Smith, Kruger, Silverman, Haff, Hayes,

Silverman, et al., as cited in 22]. One aspect

of organisational behaviour which is likely to

affect workers perceptions of organisational

safety climate, and in turn influence safe work

behaviours, and accident frequency is the extent

to which workers perceive their organisations as

being supportive, concerned and caring about

their general well-being and satisfaction. In the

literature this has been technically referred to as

job satisfaction.

1.3. Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction is defined as the degree to which

a worker experiences positive affection towards

his or her job [23]. Locke [24] in his well-cited

definition considers job satisfaction to be a

pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting

from the appraisal of ones job or job experiences

and as a function of the perceived relationship

between what one wants from ones job and what

one perceives it as offering (p. 1300). Though

recent theorising on job satisfaction describes it

as a multifaceted construct, and a function of two

major factors, dispositional (worker personality

traits) and situational (workplace factors) [25,

26, 27], the general indication, however, is that

job satisfaction is more of an affective reaction to

ones job, an evaluative measure and consequently

an indicator of working conditions [Hart et al., as

cited in 4, 23]. Occupational injuries and industrial

accidents are therefore likely to be mediated by

organisational climate and job satisfaction.

The explanation for the proposed link between

job satisfaction and organisational safety climate

relates to the fact that the degree of an employees

job satisfaction derives from meaningful

organisational and social organisational values,

JOSE 2005, Vol. 11, No. 3

norms, beliefs, practices and procedures operational

at the workplace. In effect, the perceived level of

support provided by an organisation will turn out

to be closely associated with safety climate and

other organisational and social factors which are

important for safety. If workers perceive that their

organisations are supportive and are satisfied with

the organisational structures in place, they are

more likely to recognise that the organisations

value their safety and general well-being as well.

This assessment in turn reflects positively on

their perceptions of the prevailing safety climate

and influences organisational behaviour. Thus,

it is on record that when workers basic needs

are met consistently and the workers express

job satisfaction, they display greater emotional

attachment, involvement and express stronger

feelings of allegiance and loyalty to their

organisations [28, 29]. In line with this, a number

of studies have consistently found strong and

positive relationships between job satisfaction

and productive organisational behaviours such

as perceived organisational support [28, 30],

organisational citizenship behaviours [31, 32, 33]

and fairness perception [28, 34]. Additionally,

research reports on the job satisfaction-safety

link have indicated that satisfied workers, more

than their dissatisfied counterparts, are motivated

into safe work behaviours [17, 35] and register

relatively lower accident rates [17, 36, 37].

The central theories used in explaining the

motivational basis behind job satisfaction and

these positive organisational behaviours are the

Social Exchange Theory [38] and Reciprocity

Theory [39]. Basically, according to these theories,

expressions of positive affect and concern for

others create a feeling of indebtedness and a

corresponding sense of obligation to respond

positively in return. Workers who perceive a high

level of organisational concern and support, and are

satisfied with workplace conditions, feel a sense of

indebtedness and a need to reciprocate in terms that

will benefit their organisations/management [40,

41]. Complementary research findings along this

line of argument in both social psychology [42, 43]

and the organisational literature [41] have confirmed

that one type of prosocial behaviour facilitates other

types of prosocial behaviours due to the personal

JOB SATISFACTION & WORKPLACE SAFETY PERCEPTION

values acquired through the socialisation process.

Organisational researchers have therefore found

satisfied workers to be more actively engaged

in activities that are considered as facilitative to

organisational goals than their dissatisfied work

colleagues [44]. Thus relative to their dissatisfied

colleagues, satisfied workers are more likely to

comply with safety-related practices.

Downloaded by [64.62.219.84] at 02:28 14 May 2016

1.4. The Current Study

The current study is part of a larger explorative

study that examined safety perceptions among

Ghanaian industrial workers. Even though job

satisfaction has been extensively researched,

and its relationship with accident frequency well

documented, surprisingly, no systematic attempt

has been made to explore the empirical relations

between job satisfaction and workers perceptions

of workplace safety. This study was designed to

address this oversight. Specifically, it compares

the degree of workers job satisfaction with their

perceptions of safety on Hayes et al.s [45] Work

Safety Scale (WSS). Follow-up analyses compare

satisfied and dissatisfied workers on compliance

with safe work, and finally, on their accident

involvement rate.

Two major instruments are used here. The first

is Hayes et al.s [45] WSS. This scale effectively

captures all the dimensions identified by safety

experts to influence workers perceptions of

workplace safety. These are management values,

management and organisational practices,

communication, workers involvement in workplace

health and safety, workers concern or indifference

about safety, and the level of safety precautions

in the company. The other major instrument is

Porter and Lawlers [46] one-item global measure

of job satisfaction: an instrument that has been

extensively used in measuring job satisfaction in

the organisational literature [47, 48].

1.5. Hypotheses

Based on the current organisational safety

literature, and the literature review in section 1,

the following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 1. I anticipate a positive relationship

between job satisfaction and safety climate.

293

Workers with a high degree of job satisfaction

will correspondingly have positive perceptions

regarding safety climate and vice versa.

Hypothesis 2. It is anticipated that workers who

express job satisfaction will be more committed

to safe work policies than their dissatisfied

counterparts.

Hypothesis 3. It is anticipated that workers who

express job satisfaction will register relatively fewer

accidents than their dissatisfied counterparts.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Selection and Description of

Participants

The participants320 Ghanaian industrial

workershad the following characteristics: 65%

were male and 35% female. Subordinate workers

comprised of 75% and supervisors, 25%. Forty

percent were single and 60% were married. In

terms of educational levels, 23% of the respondents

reported having only basic education, 36%

reported secondary or technical education, 38%

reported having some professional or commercial

education and 3% university education. Regarding

tenure, 13% of the respondents had been at the

workplace for less than a year, 22% between

1 and 4 years, 21% between 5 and 10 years, 25%

between 11 and 14 years and 19% over 15 years.

The interviews were administered during

lunch breaks. Their duration varied from 15 to

20 min, depending on the context in which they

were conducted and on the participants level of

education. The questionnaire was presented in

English. Where participants were illiterates or

semi-illiterates and had problems understanding

the English language, the services of an interpreter

were sought and the local dialect was used. The

supervisors were educationally sound and filled

in the questionnaire on their own. To ensure

accuracy of responses, particularly regarding

issues that related to noncompliant job behaviours

and worker counterproductive behaviours, it was

emphasised that the study was part of an academic

study and that no person affiliated with the

JOSE 2005, Vol. 11, No. 3

294 S.A. GYEKYE

workers organisation was involved in any way.

Participants were also assured that all responses

were completely confidential and that their

organisations/management would have no access

to any information provided.

Downloaded by [64.62.219.84] at 02:28 14 May 2016

2.2. Measures, Questionnaire Scoring and

Reliability

2.2.1. Perceptions of safety climate were measured

with the 50-item WSS [45]. This instrument

assesses employees perceptions of work safety

and measures five factorially distinct constructs:

(a) job safety, (b) co-worker safety, (c) supervisor

safety, (d) managements commitment to safety

and (e) satisfaction with safety programme.

Past research has shown this scale to have good

psychometric properties [49]. Sample items were

Safety programmes are effective, Supervisors

enforce safety rules, Management provides

safe work conditions. The authors reported

a coefficient alpha of .91 for job safety; .91 for

co-worker safety; .95 for supervisors safety;

.95 for management safety practices; and .93 for

satisfaction with safety programme. Responses

to this scale in the current study produced

satisfactory reliability of .96 for job safety; .80

for co-worker safety, .97 for supervisors safety;

.94 for management safety practices; and .86 for

satisfaction with safety programme. The total

coefficient alpha score was .87. Participants

responded on a 5-point scale ranging from 1not

at all to 5very much.

2.2.2. Job satisfaction was measured with Porter

and Lawlers [46] one-item global measure of job

satisfaction. This scale was chosen because singleitem measures of overall job satisfaction have been

considered to be more robust than scale measures

[50]. Besides, it has been used extensively in the

organisational behaviour literature [47, 48]. The

measure has five response categories ranging

from extremely dissatisfied to extremely satisfied,

corresponding to the 5-point response format

1not at all to 5very much. Thus, the scores

were coded so that higher scores (4quite much

and 5very much) reflected higher levels of job

satisfaction, and lower scores (1not at all and

JOSE 2005, Vol. 11, No. 3

2very little), lower levels of job satisfaction or

job dissatisfaction.

2.2.3. Items for compliance with safety behaviour

were pooled from the extant literature. They

comprised of four questions and assessed workers

compliance with safety behaviour. Sample items

were Keep my workplace clean, Follow

safety procedures regardless of the situation.

Participants responded on a 5-point scale ranging

from 1not at all to 5very much.

2.2.4. Accident frequency was measured by

participants responses to the question that asked

them to indicate the number of times they had been

involved in accidents in the past 12 months. All

cases studied were accidents classified as serious

by the safety inspection authorities.

2.3. Data Analyses

Statistical analyses of the data were done with SAS

v. 8-2001. Using job satisfaction as an independent

variable, differences among the perceptions were

identified by a one-tailed ANOVA analysis. This

provided an item-by-item score for the workers

on all 50 items of the safety perception scale.

To examine further the relationship between the

categories of satisfied and dissatisfied workers, the

sum variables of the subsets scales were calculated

and subjected to further ANOVA analyses.

This provided the statistical differences on the

workers perceptions. Participants responses on

compliance with safety behaviours and accident

involvement were subjected to a similar procedure.

Items that were not completed by the respondents

were coded as missing values and excluded from

the analyses.

3. RESULTS

The

means,

standard

deviations

and

intercorrelations for the five subsets of workplace

safety perception and job satisfaction are

reported in Table 1.

Examination of the correlation pattern in Table 1

reveals interesting insights. The subsets on the

safety scale were all highly significantly correlated

with each other. The correlation between work

295

JOB SATISFACTION & WORKPLACE SAFETY PERCEPTION

TABLE 1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Between Job Satisfaction, Accident Frequency and

Work Safety Scale (WSS)

Variable

1. Job satisfaction

2. Accident frequency

3. WSSA

4. WSSB

5. WSSC

6. WSSD

7. WSSE

M

3.29

1.84

25.09

30.38

32.88

27.71

29.49

SD

1.42

1.09

10.62

6.24

11.56

9.78

10.66

.65***

.63***

.61***

.69***

.56***

.69***

.81***

.71***

.84***

.70***

.84***

.69***

.80***

.66***

.81***

.77***

.61***

.76***

.82***

.90***

.80***

Downloaded by [64.62.219.84] at 02:28 14 May 2016

Notes. WSSAwork safety, WSSBco-worker safety, WSSCsupervisor safety, WSSDmanagement

practices, WSSEsafety programmes; N = 244306; ***p < .001.

safety and all except accident involvement was

negative. The lower the accident frequency, the

higher the perceptions were of co-worker safety,

supervisor safety, management practices and

safety programmes. The correlations for the

four other subsets with job satisfaction were

positive. The strongest correlation on the matrix

was between supervisor safety and safety

programmes, and the weakest was between

management practices and job satisfaction.

The findings supported the hypotheses. A

distinctive pattern of perception associated

with the level of job satisfaction was noted. As

anticipated, dissatisfied workers had a rather

pessimistic and unconstructive view of the safety

climate in their workplaces. Meanwhile their

counterparts, who expressed job satisfaction, had

a noticeably positive and constructive perception.

Results on the five subscales are presented first.

They are then followed by item-by-item analyses

within their domain.

3.1. Hypothesis 1

The ANOVA scores indicated differences of highly

statistical significance on all five constructs of the

WSSA scale: Regarding workers perceptions

of job safety, workers with no job satisfaction

at all were the least enthusiastic with the safety

level in their work assignments (f(4, 300) = 56.76,

p < .0001). They significantly perceived their job

assignments to be dangerous (f(4, 303) = 136.38,

p < .0001), hazardous (f(4, 302) = 35.23,

p < .0001), risky (f(4, 302) = 36.83, p < .0001),

unhealthy (f(4, 302) = 37.41, p < .0001), unsafe

(f(4, 302) = 47.76, p < .0001) and scary (f(4, 300)

= 51.96, p < .0001). Not surprisingly, they felt they

could get hurt (f(4, 302) = 44.22, p < .0001), and

gave thought to chance of death (f(4, 302) = 40.24,

p < .0001) and fear of death (f(4, 302) = 35.35,

p < .0001). Interestingly, workers who expressed

very much job satisfaction highly significantly

considered their job assignments to be safe

(f(4, 303) = 139.29, p < .0001), which happened

to be the only positive item on that subscale.

On the co-worker safety subscale, workers

with very much job satisfaction highly significantly

perceived their co-workers contribution to safety

as constructive and valuable (f(4, 290) = 44.18,

p < .0001). They noted that their co-workers

pay attention to safety rules (f(4, 300) = 14.55,

p < .0001), follow safety rules (f(4, 300) = 43.47,

p < .0001), look out for others safety (f(4, 299)

= 67.61, p < .0001), encourage others to behave

safely (f(4, 297) = 52.56, p < .0001), keep workplace

clean (f(4, 296) = 34.23, p < .0001) and tend to

be safety oriented (f(4, 297) = 51.24, p < .0001).

On the other hand, dissatisfied workers (with no

job satisfaction at all) had a different perspective.

They significantly perceived their co-workers to

ignore safety rules (f(4, 301) = 19.62, p < .0001),

take chances with safety (f(4, 296) = 13.84,

p < .0001) and not to care about safety (f(4, 300)

= 40.29, p < .0001). Differences on do not

pay attention were not statistically significant

(f(4, 293) = 0.91, ns).

Regarding supervisor safety, satisfied

workers (especially those with very much job

satisfaction) significantly perceived supervisors

roles and support as crucial to their work safety

(f(4, 302) = 78.37, p < .0001). They noted how their

supervisors praise safe work (f(4, 303) = 41.67,

p < .0001), encourage safe behaviours (f(4, 303)

= 54.12, p < .0001), keep workers informed of

JOSE 2005, Vol. 11, No. 3

296 S.A. GYEKYE

TABLE 2. Means and Standard Deviations of Job Satisfaction and Work Safety Scale (WSS)

Downloaded by [64.62.219.84] at 02:28 14 May 2016

WSS

A. Work safety

1. Dangerous

2. Safe

3. Hazardous

4. Risky

5. Unhealthy

6. Could get hurt

7. Unsafe

8. Fear for health

9. Chance of death

10. Scary

B. Co-worker safety

1. Ignore safety rules

2. Dont care about others safety

3. Pay attention to safety rules

4. Follow safety rules

5. Look out for others safety

6. Encourage others to behave

safely

7. Take chances with safety

8. Keep work area clean

9. Safety-oriented

10. Dont pay attention

C. Supervisor safety

1. Praises safe work behaviours

2. Encourages safe behaviours

3. Keep workers informed of safety

rules

4. Rewards safe behaviours

5. Involves workers in setting

safety goals

6. Discusses safety issues

7. Updates safety rules

8. Trains workers to be safe

9. Enforces safety rules

10. Acts on safety suggestions

D. Management safety practices

1. Provides enough safety

programmes

2. Conducts frequent safety

inspections

3. Investigates safety problems

4. Rewards safe workers

5. Provides safe equipment

6. Provides safe working conditions

7. Responds quickly to safety

concerns

8. Helps maintain clean area

JOSE 2005, Vol. 11, No. 3

Dissatisfied Workers

Satisfied Workers

Not at All Very Little

Neutral Quite Much Very Much ANOVA

SD

SD

p

M

M SD

M

M

SD

M SD

F(4, 300) = 56.76, p < .0001

4.65 0.81 3.84 1.09 3.15 0.88 1.62 0.94 1.48 1.02

***

1.24 0.66 1.81 1.02 2.31 0.78 4.00 0.92 4.31 1.23

***

3.68 1.50 3.62 1.53 2.68 0.82 1.61 0.93 1.82 1.48

***

3.63 1.53 3.46 1.26 2.56 0.91 1.78 0.96 1.72 1.20

***

3.66 1.44 3.51 1.30 2.65 1.00 1.84 1.05 1.67 1.09

***

3.84 1.33 3.78 1.25 2.63 1.07 1.73 1.03 1.71 1.24

***

1.45

1.23

1.14

0.96

3.84

3.46

3.03

1.87

1.73 1.12

***

3.74 1.57 3.46 1.39 2.81 1.14 1.79 0.97 1.82 1.26

***

3.51 1.54 3.58 1.18 2.78 1.15 1.57 0.92 1.65 1.29

***

3.68 1.27 3.10 1.13 2.84 1.03 1.62 0.91 1.64 1.12

***

3.28

3.66

2.57

2.27

2.14

2.14

1.38

1.32

1.33

1.29

1.36

1.13

3.27

2.59

2.43

2.38

2.35

2.37

F(4, 290) = 44.18, p < .0001

1.24 2.68 0.89 2.13 0.90

1.17 2.63 0.83 1.87 0.90

1.11 3.09 1.15 3.41 0.98

1.11 3.28 1.05 4.02 0.97

0.92 3.25 0.88 4.27 0.81

1.11 2.72 0.92 3.76 0.68

3.25

2.12

2.10

2.33

1.33

1.23

1.34

1.08

2.44

2.37

2.24

2.34

1.02

1.98

1.01

0.99

2.75

3.12

3.00

2.38

0.98

0.94

0.95

0.66

3.24

3.67

4.13

2.25

1.14

0.88

0.89

1.17

1.83

1.65

3.93

4.31

4.47

4.09

1.16

1.12

1.16

1.03

0.96

1.08

***

***

***

***

***

***

2.01

3.82

4.14

2.66

1.07

1.13

1.24

1.28

***

***

***

ns

2.65 0.88

2.29 1.07

2.21 1.13

F(4,302 ) = 78.37, p < .0001

2.51 0.80 3.16 0.76 3.69 0.66

2.08 0.72 3.21 0.97 3.75 0.86

2.14 0.75 3.03 1.06 3.69 0.88

4.78 0.88

4.21 1.10

4.11 1.17

***

***

***

1.81 1.23

2.00 1.21

1.83 0.87

1.86 0.82

3.96 1.00

3.96 1.16

***

***

4.03

4.11

4.18

4.22

4.43

1.11

1.14

1.39

1.24

1.09

***

***

***

***

***

2.15

2.24

2.19

2.26

2.28

1.13

1.25

1.28

1.21

1.33

1.76

2.05

1.95

1.91

2.21

0.95

0.78

0.99

0.95

1.13

2.78 0.97

2.68 0.99

2.87

3.18

3.00

3.16

3.22

1.03

1.23

1.16

0.80

0.83

3.44 1.00

3.70 1.00

3.90

3.87

4.01

4.12

4.25

0.89

0.97

0.82

0.96

0.96

2.28 1.16

F(4, 302) = 44.86, p < .0001

2.29 0.97 2.65 0.87 3.31 0.97

3.36 0.95

***

1.82 0.83

1.81 0.70

2.67 1.12

***

2.53

2.49

3.03

3.41

3.35

1.00

0.96

1.05

0.98

1.18

***

***

***

***

***

3.42 1.31

***

1.84

1.93

1.86

1.86

2.00

0.87

0.97

0.97

0.95

1.11

2.00 1.06

1.64

1.83

1.70

1.70

2.00

0.79

0.83

0.74

0.70

0.70

1.78 0.88

2.47 1.14

2.62

2.44

2.78

2.81

2.88

0.91

0.98

0.91

0.99

1.13

2.69 1.20

2.87 1.13

2.87

2.63

3.26

3.32

3.41

1.09

1.18

0.99

0.98

1.11

3.61 1.11

JOB SATISFACTION & WORKPLACE SAFETY PERCEPTION

297

TABLE 2. (continued)

Downloaded by [64.62.219.84] at 02:28 14 May 2016

WSS

9. Provides safety information

10. Keep workers informed of

hazards

E. Safety programmes (policies)

1. Worthwhile

2. Helps prevent accidents

3. Useful

4. Good

5. First-rate

6. Unclear

7. Important

8. Effective in reducing injuries

9. Do not apply to my workplace

10. Do not work

Dissatisfied Workers

Satisfied Workers

Not at All Very Little

Neutral Quite Much Very Much ANOVA

SD

SD

p

M

M SD

M

M

SD

M SD

2.00 1.21 2.08 0.89 3.00 0.98 3.84 1.11 3.58 1.29

***

2.00 1.11 1.95 0.94 2.81 1.12 3.88 1.08 3.59 1.38

***

2.21

2.09

1.84

1.84

1.89

2.32

1.95

2.03

2.06

2.44

1.17

1.15

1.26

1.32

1.29

1.19

1.21

1.28

1.26

1.12

2.08

1.78

1.67

1.54

1.70

3.21

1.76

1.56

1.82

2.20

F(4, 255) = 73.38, p < .0001

0.86 3.16 0.81 4.08 0.88

0.82 3.09 0.92 3.89 1.00

0.91 2.91 0.99 4.08 1.04

0.93 2.93 1.16 4.10 1.13

0.93 2.68 1.06 3.76 1.04

1.29 2.50 0.84 2.96 1.20

0.79 2.96 1.03 3.74 1.10

0.69 2.84 1.22 3.88 1.06

1.02 2.41 1.05 2.64 1.33

1.07 2.00 0.81 2.63 1.35

4.21

4.09

4.23

4.18

4.17

2.27

3.90

4.07

2.84

2.67

1.09

1.16

1.19

1.15

1.00

1.21

1.15

1.02

1.37

1.37

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

ns

ns

Notes. ***p < .001.

safety rules (f(4, 303) = 44.35, p < .0001), reward

safe behaviours (f(4, 303) = 50.40, p < .0001),

involve workers in setting safety goals (f(4, 302)

= 48.75, p < .0001), discuss safety issues with

others (f(4, 303) = 59.32, p < .0001), update

safety rules (f(4, 303) = 43.43, p < .0001), train

workers to be safe (f(4, 303) = 56.98, p < .0001),

enforce safety rules (f(4, 303) = 57.41, p < .0001)

and act on safety suggestions (f(4, 303) = 57.48,

p < .0001).

Regarding management safety practices,

satisfied workers (particularly those who expressed

quite much satisfaction), significantly perceived

managements role and contributions as imperative

to work safety (f(4, 300) = 44.86, p < .0001). They

had taken note of how management frequently

conducts safety inspections (f(4, 302) = 14.22,

p < .0001), investigates safety problems (f(4, 302)

= 17.30, p < .0001), rewards safe work (f(4, 300)

= 6.90, p < .0001), provides safe equipment

(f(4, 301) = 31.65, p < .0001), helps maintain clean

area (f(4, 301) = 32.42, p < .0001), provides safety

information (f(4, 301) = 35.37, p < .0001) and

keeps workers informed on safety issues (f(4, 301)

= 38.81, p < .0001). Similarly, their colleagues

who expressed very much job satisfaction had

observed how management provides enough safety

programmes (f(4, 302) = 17.69, p < .0001), safe

working conditions (f(4, 301) = 41.37, p < .00001)

and responds quickly to safety concerns (f(4, 301)

= 24.96, p < .0001).

Regarding perceptions on the safety

programmes subscale, again, it was the satisfied

workers who had a positive and upbeat view.

Satisfied workers (particularly those with very

much job satisfaction) were significantly satisfied

with the safety policies in place at the worksite

(f(4, 255) = 73.88, p < .0001). They perceived the

safety programmes to be worthwhile (f(4, 301)

= 62.82, p < .0001), useful (f(4, 300) = 71.49,

p < .0001), good (f(4, 300) = 72.03, p < .0001),

first rate (f(4, 300) = 61.27, p < .0001), important

(f(4, 299) = 47.71, p < .0001), help prevent

accidents (f(4, 300) = 56.96, p < .0001) and,

accordingly, effective in reducing accidents

(f(4, 297) = 59.64, p < .0001). Not surprisingly,

their dissatisfied counterparts (those with very

little satisfaction) significantly found the safety

programmes to be unclear (f(4, 294) = 6.80,

p < .0001). There were no differences in statistical

significance on do not apply to my workplace

(f(4, 273) = 5.11, ns) and do not work (f(4, 267)

= 2.22, ns).

Interesting observations concerning workers

compliance with safety management policies and

accident frequency were made.

JOSE 2005, Vol. 11, No. 3

298 S.A. GYEKYE

4. DISCUSSION

3.2. Hypothesis 2

Downloaded by [64.62.219.84] at 02:28 14 May 2016

Differences regarding compliance with safety

management policies were of statistical

significance (f(4, 296) = 60.00, p < .0001).

Satisfied workers (workers who indicated very

much and closely followed by quite much) were

more committed to safe work behaviours than their

dissatisfied counterparts. As reflected in Table 3,

dissatisfied workers were the least committed to

safe work practices. Workers with no satisfaction

at all were the worse culprits, closely followed

by their colleagues who had indicated very

little job satisfaction. This observation had been

anticipated.

The major focus of this study was an analysis

of a link between job satisfaction and safety

perception. It was hypothesised that job satisfaction

would affect workers perception of safety with

subsequent implications for their work behaviours

and accident involvement. The major finding

was an association between job satisfaction and

safety perception. As predicted, workers who

expressed higher levels of job satisfaction also

had positive perspectives on safety climate.

In contrast, dissatisfied workers had negative

perspectives. In effect, workers perceptions of

workplace safety seem to reflect the extent to

which they perceive their organisations as being

supportive and committed to their well-being and

TABLE 3. Descriptive Statistics on Safe Work Behaviour, Accident Involvement Rate and Job

Satisfaction

Variable

Safe work

behaviours

Accident

involvement rate

Dissatisfied Workers

Not at All

Very Little

M

SD

M

SD

11.16 5.33

2.94

1.04

Neutral

M

SD

12.13 4.25

15.47 4.07

2.86 0.76

1.94 0.76

Satisfied Workers

Quite Much

Very Much ANOVA

M

SD

M

SD

p

19.13 3.29

1.24

0.60

20.65 4.31

***

1.29 0.89

***

Notes. ***p < .001.

3.3. Hypothesis 3

A difference of high statistical significance in

favour of satisfied workers was again indicated on

accident frequency (f(4, 295) = 64.83, p < .0001).

As anticipated, satisfied workers (quite much

followed by very much) recorded lower accident

rates. In contrast, dissatisfied workers (those

without any job satisfaction at all followed by

those with very little satisfaction) recorded higher

accident rates. All in all, workers who expressed

job satisfaction had a positive perception of

safety climate, they were more committed to safe

work practices and consequently had a relatively

lower rate of accident involvement. In contrast,

their dissatisfied work colleagues, who had

negative perspectives regarding safety climate,

were less committed to the organisations, safety

procedures and registered a higher rate of accident

involvement.

JOSE 2005, Vol. 11, No. 3

satisfaction. This observation reinforces previous

findings on job satisfaction as a context-related

phenomenon influenced by a variety of contextual

factors [Hart et al., as cited in 4, 9, 23], in this case

safety climate, which is a subset of organisational

climate. Apparently, job satisfaction does not

happen in a vacuum: workers who are satisfied or

dissatisfied in their workplaces are either motivated

or discouraged by the prevailing organisational

climate.

As anticipated and consistent with previous

findings, satisfied workers were more

compliant with safety management policies and

subsequently registered relatively lower rates of

accident involvement than their dissatisfied work

counterparts [16, 36, 37, 51]. This observation

is consistent with suggestions that employees

perceptions of safety influence their compliance

with safety-related practices [44, 52]. Ostensibly,

this was an avenue for satisfied workers to

JOB SATISFACTION & WORKPLACE SAFETY PERCEPTION

reciprocate the implied obligation resulting from

their positive perceptions of managements concern

for their well-being. The current observation thus

further reinforces the social exchange theory and

the norms of reciprocity as bases of workers

safety-related behaviours [40, 53].

Downloaded by [64.62.219.84] at 02:28 14 May 2016

4.1 Implication of the Findings in the Work

Environment

A significant practical implication of the

current study for workplace safety personnel

and management is that interventions aimed

at demonstrating organisational support and

concern for workers well-being and satisfaction

will not only add to organisational efficiency

and productivity, but will also decrease accident

frequency and thereby reduce the high human and

social costs associated with industrial accidents.

The organisational literature on job satisfaction

is full of organisational structures that positively

impact on workers degree of job satisfaction:

providing support and showing commitment

to workers beyond what is formally stated in

contractual agreements [44, 54], implementing

fairness perception measures [34], instituting job

enrichment programmes [36, 37] and providing

the means for workers to acquire safety skills [35,

55, 56].

no member of their organisations was involved in

the study in any way.

Self-reported measures have been commonly

and successfully used in safety analyses [4, 20],

and organisational behaviour studies [57, 58].

While epidemiologic reports have been found to

be faulty, biased and deficient because of poor

documentation [59, 60], research reports have

found self-reported accident rates to be closely

related to documented accident rates [Smith et al.,

as cited in 23]. Even though emphasis in this study

was laid on the role of situational (workplace)

factors in job satisfaction, it must also be stated

that dispositional factors and workers affect still

play a part in determining the level of workers

job satisfaction [61, 62].

REFERENCES

1.

2.

3.

4.

4.2 Limitations

The need for the participants to recall industrial

mishaps was the major limitation of this research.

Retrospective accident analysis always entails the

risk of memory error. However, as the studied

accidents had occurred less than a year before the

interview, it is assumed that recall distortion was

minimised. Prospective examinations of accident

processes could be viable alternatives to such

retrospective studies. The use of self-reported

measures was another limitation. Responses are

likely to be affected by intentional distortions

and misinformation, particularly regarding

those on noncompliant job behaviours and

counterproductive behaviours. To counter this

threat, participants were promised anonymity and

condentiality. Besides, they were guaranteed that

299

5.

6.

7.

8.

Guldenmund FW. The nature of safety

culture: a review of theory and research.

Saf Sci 2000;34:21557.

James L, McIntyre D. Perceptions of

organizational climate: In: Murphy K,

editor. Individual differences and behaviour

in organisations. San Francisco, CA, USA:

Jossey-Bass; 1996. p. 4084.

Flin R, Mearns K, OConnor P, Bryden, R.

Measuring safety climate: identifying the

common features. Saf Sci 2000;34:17792.

Neal A, Griffin MA, Hart P. The impact of

organisational climate on safety climate and

individual behaviour. Saf Sci 2000;34:99

109.

Silva S, Lima LM, Baptista C. OSCI: an

organisational and safety climate inventory.

Saf Sci 2004;42:20520.

Cooper MD, Phillips RA. Exploratory

analysis of the safety climate and safety

behaviour. J Saf Res 2003;35:497512.

Griffin M, Mathieu J. Modelling

organisational process across hierarchical

levels: climate, leadership, and group process

in work groups. J Organ Beh 1997;18:731

44.

Griffin M, Neal A. Perceptions of safety

at work: a framework for linking safety

climate to safety performance, knowledge,

and motivation. J Occup Health Psychol

2000;5:34758.

JOSE 2005, Vol. 11, No. 3

300 S.A. GYEKYE

9.

Michela J, Lukazewski M, Allegrante P.

Organizational climate and work stress: a

general framework applied to inner-city

schoolteachers. In: Sauter S, Murphy S,

editors. Organisational risk factors for job

stress. Washington, DC, USA: American

Psychological Association; 1995. p. 6180.

Downloaded by [64.62.219.84] at 02:28 14 May 2016

10. Brown SP, Leigh TW. A new look at

psychological climate and its relationship to

job involvement, effort, and performance. J

Appl Psychol 1996;81:35868.

11. Morrison DL, Upton DM, Cordery J.

Trust and skill utilisation as mediators

of job characteristics: a three year case

study. In Koubek R, Karwowski W,

edtiors. Manufacturing agility and hybrid

automation. Santa Monica CA, USA: IEA

Press; 1998. p. 170176.

12. Zohar D. Safety climate in industrial

organization: theoretical and applied

implications. J Appl Psychol 1980;65:96

102.

13. Zohar D. A group-level model of safety

climate: testing the effect of group climate

on micro accidents in manufacturing jobs. J

Appl Psychol 2000;85(4):58759.

14. Hofmann D, Stetzer A. A cross-level

investigation of factors influencing unsafe

behaviours and accidents. Pers Psychol

1996;49:30739.

15. Salminen S. Does pressure from the

work community increase risk taking?

Psychol Rep 1995;77:124750.

16. Probst T. Layoffs and tradeoffs: production,

quality, and safety demands under the

threat of a job loss. J Occup Health Psychol

2002;7:21120.

17. Probst T, Brubaker T. The effects of job

insecurity on employee safety outcomes:

cross-sectional and longitudinal explorations.

J Occup Health Psychol 2001;6:39159.

18. Guastello S, Gershon R, Murphy L.

Catastrophe model for the exposure of

blood-borne pathogens and other accidents

in health care settings. Acc Ana Pre

1999;31:73950.

19. Murray M, Fitzpatrick D, OConnell C.

Fishermens blue: factors related to accidents

and safety among Newfoundland fishermen.

Wk Str 1997;11:2927.

JOSE 2005, Vol. 11, No. 3

20. Siu Oi-ling, Phillips D, Leuhg T. Safety

climate and safety performance among

construction workers in Hong Kong: the

role of psychological strains as mediators.

Accid Ana Prev 2004;36(3);35966.

21. Harrell WA. Perceived risk of occupational

injury: control over pace of work and blue

collar work. Percp Mot Skills 1990;70:1351

8.

22. Smith CS, Silverman, GS, Heckert TM,

Brodke M, Hayes B, Silverman MK, et al.

A comprehensive method for the assessment

of industrial injury events. Journal of

Prevention & Intervention in the Community

2001;22(1):520.

23. Locke E. What is job satisfaction? Organ

Beh Hum Perf 1969;3:30936.

24. Locke E. The nature and causes of job

satisfaction. In: Dunnette MD, editor.

Handbook of industrial and organisational

psychology. Chicago, IL, USA: Rand

McNally; 1976. p. 1297349.

25. Brief A, Weiss H. Organizational behaviour:

affect in the workplace. Ann Rev Psychol

2002;53:279307.

26. Dormann C, Zapf D. Job satisfaction: a

meta-analysis of stabilities. J Organ Beh

2001;22:483504.

27. Judge T, Bono J, Locke E. Personality and

job satisfaction: the mediating role of job

characteristics. J Appl Psychol 2000;85:17

34.

28. Rhoades L, Eisenberger R. Perceived

organisational support. A review of the

literature. J Appl Psychol 2002;87:698

714.

29. Shore L, Shore T. Perceived organisational

support and organisational justice. In:

Cropanzano R, Kacmar K, editors.

Organisational politics, justice, and support.

Westport, CT, USA: Quorum Books; 1995.

p. 14964.

30. Setton RP, Bennett N, Liden RC. Social

exchange in organisations: perceived

organisational support, leader-member

exchange and employee reciprocity. J Appl

Psychol 1996;81:21927.

31. Moorman RH. Relationship between

organisational justice and organisational

citizenship behaviours: do fairness

perceptions influence employee citizenship

JOB SATISFACTION & WORKPLACE SAFETY PERCEPTION

32.

33.

Downloaded by [64.62.219.84] at 02:28 14 May 2016

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

behaviours? J Appl Psychol 1991;76:845

55.

Podsakoff P, Mackenzie SB, Paine J,

Bachrach D. OCB: a critical review of the

theoretical and empirical literature and

suggestions for future research. J Manag

2000;26(3):51363.

Williams L, Anderson S. Job satisfaction and

organisational commitment as predictors

of organisational citizenship and in-role

behaviours. J Manag 1991;17:60117.

Simons T, Robertson Q. Why managers

should care about fairness: the effect

of aggregate justice perception on

organisational outcomes. J Appl Psychol

2003;88(3);43243.

Baring J, Kelloway KE, Iverson R.

High quality work, job satisfaction, and

occupational injuries. J Appl Psychol

2003;88(2):27683.

Berg P. The effects of high performance

work practices on job satisfaction in the

United States steel industry. Ind Relat

1999;54:11134.

Godard J. High performance and the

transformation of work: the implications of

alternative work practices for the future of

Canadian IR research. Ind Relat 2001;56:3

33.

Blau P. Exchange and power in social life.

New York, NY, USA: Wiley; 1964.

Gouldner AW. The norm of reciprocity. Am

Socio Rev 1960;25:16178.

Hofmann DA, Morgeson FP, Gerras SJ.

Climate as a moderator of the relationship

between leader-member exchange and

content

specific

citizenship:

safety

climate as an exemplar. J Appl Psychol

2003;88(1):1708.

Kelley SW, Hoffman KD. An investigation

of positive affect, prosocial behaviours and

service quality. J Retal 1997;73(3);40727.

Grusec JE The socialization of altruism.

In: Clark MS, editor. Prosocial behaviour.

Newbury Park: CA, USA: Sage; 1991.

p. 933.

Van Maanen M, Schein EH. Towards a

theory of organizational socialization. In:

Staw BM, editor. Research in organizational

behaviour. Greenwich, CT, USA: JAI Press;

1979, p. 20964.

301

44. Aryee S, Budhwar P, Chen Z. Trust as

a mediator of the relationship between

organizational justice and work outcomes:

test of a social exchange model. J Organ

Beh 2002;23:26785.

45. Hayes B, Perander J, Smecko T, Trask J.

Measuring perceptions of workplace safety:

development and validation of the work

safety scale. J Saf Res 1998;29(3):14561.

46. Porter L, Lawler E III. Managerial attitudes

and performance. Homewood, IL, USA:

Irwin-Dorsey; 1968.

47. Baba V, Jamal M. Routinization of job

context and job content as related to

employees quality of working life: a

study of Canadian nurses. J Organ Beh

1991;12:37986.

48. Harter J, Hayes T, Schmidt F. Businessunit level relationship between employee

satisfaction, employee engagement, and

business outcomes. A meta-analysis. J Appl

Psychol 2002;87:26879.

49. Milczarek M, Najmiec A. The relationship

between workers safety culture and

accidents, near accidents and health problem.

International Journal of Occupational Safety

and Ergonomics (JOSE) 2004;10(1):2533.

50. Wanous P, Reichers A, Hody M. Overall

job satisfaction. How good are single-item

measures? J Appl Psychol 1997;82:147

252.

51. OToole M. The relationship between

employees perception of safety and

organisational culture. J Saf Res 2002;

33(2):23143.

52. Bailey C. Managerial factors related to

safety program effectiveness: an update on

the Minnesota perception study. Prof Saf

1997;8:335.

53. Hofmann D, Morgeson F. Safety-related

behaviour as a social exchange: the role

of perceived organizational support and

leader-member exchange. J Appl Psychol

1999;84(2):28696.

54 Eisenberger R, Armeli S, Rexwinkel B,

Lynch P, Rhodes L. Reciprocation of

perceived organisational support. J Appl

Psychol 2001;86:4251.

55. Biridi K, Allan C, Warr P. Correlates

and perceived outcomes of four types of

JOSE 2005, Vol. 11, No. 3

302 S.A. GYEKYE

Downloaded by [64.62.219.84] at 02:28 14 May 2016

employee development activity. J Appl

Psychol 1997;82:84557.

56. Trevor C. Interactions among ease-ofmovement determinants and job satisfaction

in the prediction of voluntary turnover. Acad

Manag J 2001;44:62138.

57. Bell SJ, Menguc B. The employeeorganization relationship, organizational

citizenship behaviours and superior service

quality. J Ret 2002;78(2):13146.

58. Turnipseed DL. Are good soldiers good?

Exploring the link between organization

citizenship behaviour and personal ethics. J

Bus Res 2002;55(1):115.

JOSE 2005, Vol. 11, No. 3

59. Parker D, Carl W, French L, Martin F.

Characteristics of adolescent work injuries

reported in Minnesota Department of

Labour and Industry. Am J Pub Health

1994;84:60611.

60. Veazie K, Landen D, Bender T, Amandus H.

Epidemiological research on the etiology

of injuries at work. Ann Rev Pub Health

1994;15:20321.

61. George M, Brief P. Feeling good, doing

good: a conceptual analysis of mood at work

organisational spontaneity relationship.

Psychol Bull 1994;112:31029.

62. Watson D. Mood and temperament. New

York, NY, USA: Guilford Press; 2000.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Occupational Stress, Job Satisfaction, Mental Health, Adolescents, Depression and the Professionalisation of Social WorkDari EverandOccupational Stress, Job Satisfaction, Mental Health, Adolescents, Depression and the Professionalisation of Social WorkBelum ada peringkat

- Engaging: Employees EmployeesDokumen9 halamanEngaging: Employees EmployeesLarín AntonioBelum ada peringkat

- SOCIAL WORK ISSUES: STRESS, THE TEA PARTY ROE VERSUS WADE AND EMPOWERMENTDari EverandSOCIAL WORK ISSUES: STRESS, THE TEA PARTY ROE VERSUS WADE AND EMPOWERMENTBelum ada peringkat

- Effect of Quality of Work Life On Organizational Commitment by SEMDokumen10 halamanEffect of Quality of Work Life On Organizational Commitment by SEMLiss MbBelum ada peringkat

- International Journal of Occupational Safety and ErgonomicsDokumen13 halamanInternational Journal of Occupational Safety and ErgonomicsCosmonautBelum ada peringkat

- Azimah PDFDokumen19 halamanAzimah PDFmatt_nazriBelum ada peringkat

- I 387483Dokumen10 halamanI 387483aijbmBelum ada peringkat

- Indicators of Quality of Work LifeDokumen6 halamanIndicators of Quality of Work LifeNadduli Julius100% (1)

- Does Organizational Environment Influence Employees' Satisfaction: A Case of Public and Private Organizations OF Pakistan?Dokumen12 halamanDoes Organizational Environment Influence Employees' Satisfaction: A Case of Public and Private Organizations OF Pakistan?Allen AlfredBelum ada peringkat

- Analysis of The Influence of Psychological Contract On Employee Safety Behaviors Against COVID-19Dokumen14 halamanAnalysis of The Influence of Psychological Contract On Employee Safety Behaviors Against COVID-19Ranjana BandaraBelum ada peringkat

- Safety Climate, Leadership & Risk PerceptionDokumen7 halamanSafety Climate, Leadership & Risk PerceptionZuraquellaxo CastaranoditaBelum ada peringkat

- Exploration of The Impact of Organisational Context On A Workplace Safety and Health InterventionDokumen20 halamanExploration of The Impact of Organisational Context On A Workplace Safety and Health InterventionHasnainBelum ada peringkat

- Employees' perceptions of work-life quality and job satisfactionDokumen12 halamanEmployees' perceptions of work-life quality and job satisfactionvidyaiiitm1Belum ada peringkat

- A Study On Factors Affecting Effort CommDokumen16 halamanA Study On Factors Affecting Effort CommDoyoGnaressaBelum ada peringkat

- Dinesh PDFDokumen33 halamanDinesh PDFDinesh PantBelum ada peringkat

- Effect of Work Environment On Job SatisfactionDokumen10 halamanEffect of Work Environment On Job SatisfactionSuraj BanBelum ada peringkat

- HRD ClimateDokumen8 halamanHRD ClimatePothireddy MarreddyBelum ada peringkat

- Stress and Motivation Relationship PDFDokumen12 halamanStress and Motivation Relationship PDFAnto GrnBelum ada peringkat

- Ergonomics Climate AssessmentDokumen10 halamanErgonomics Climate AssessmentGonzalo Sebastian Bravo RojasBelum ada peringkat

- Factors Affecting Job Satisfaction in Banking Sector - IndiaDokumen4 halamanFactors Affecting Job Satisfaction in Banking Sector - IndiajasonlawkarsengBelum ada peringkat

- Woznyj Climate and Organizational Performance in Long-Term Care Facilities - The Role of Affective CommitmentDokumen23 halamanWoznyj Climate and Organizational Performance in Long-Term Care Facilities - The Role of Affective CommitmentzooopsBelum ada peringkat

- SYNOPSIS On HRDokumen5 halamanSYNOPSIS On HRROSHAN N HBelum ada peringkat

- According To Authors TooDokumen3 halamanAccording To Authors TooLady Lyanna of House MormontBelum ada peringkat

- 1Dokumen16 halaman1gustavoBelum ada peringkat

- Job Satisfaction's Protective Effect on Health, Happiness, Well-Being & Self-EsteemDokumen22 halamanJob Satisfaction's Protective Effect on Health, Happiness, Well-Being & Self-EsteemashBelum ada peringkat

- Standardized Management Systems in The Context of Active Employee Participation in Occupational Health and SafetyDokumen16 halamanStandardized Management Systems in The Context of Active Employee Participation in Occupational Health and SafetydetxyzBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction of Study: (CITATION Kha11 /L 1033)Dokumen8 halamanIntroduction of Study: (CITATION Kha11 /L 1033)JawadBelum ada peringkat

- Perceived Safety Climate, Organizational Trust and Organizational Commitment: The Mediator Role of Job SatisfactionDokumen29 halamanPerceived Safety Climate, Organizational Trust and Organizational Commitment: The Mediator Role of Job Satisfactionkhushboo altafBelum ada peringkat

- What Is Job Satisfaction ?Dokumen6 halamanWhat Is Job Satisfaction ?viaraBelum ada peringkat

- IWBDokumen16 halamanIWBMuhammad SarfrazBelum ada peringkat

- China Based StudyDokumen11 halamanChina Based StudyVisruth K AnanadBelum ada peringkat

- Perceived Job Insecurity and Sustainable Wellbeing: Do Coping Strategies Help?Dokumen18 halamanPerceived Job Insecurity and Sustainable Wellbeing: Do Coping Strategies Help?Guemeta TsayemBelum ada peringkat

- Review of LiteratureDokumen6 halamanReview of LiteratureSylve SterBelum ada peringkat

- N L U, O: Ational AW Niversity DishaDokumen15 halamanN L U, O: Ational AW Niversity Dishajitmanyu satpatiBelum ada peringkat

- Gender and Well-Being: How it Affects EmployeesDokumen12 halamanGender and Well-Being: How it Affects EmployeesKhushi PandeyBelum ada peringkat

- Safety and Health at Work: Matteo Ronchetti, Simone Russo, Cristina Di Tecco, Sergio IavicoliDokumen7 halamanSafety and Health at Work: Matteo Ronchetti, Simone Russo, Cristina Di Tecco, Sergio IavicoliGean Pablo MendozaBelum ada peringkat

- Communication Climate, Work Locus of Control and Organizational Commitment Full Paper For ReviewDokumen8 halamanCommunication Climate, Work Locus of Control and Organizational Commitment Full Paper For ReviewVirgil GheorgheBelum ada peringkat

- Impact of Work Environment On Job Satisfaction: 1.1 General BackgroundDokumen127 halamanImpact of Work Environment On Job Satisfaction: 1.1 General BackgroundMahendra PaudelBelum ada peringkat

- Paper 08 PDFDokumen10 halamanPaper 08 PDFShoaib KhanBelum ada peringkat

- Employee Satisfaction Factors & ImpactDokumen9 halamanEmployee Satisfaction Factors & ImpactBhaskar bhaskarBelum ada peringkat

- Employee Mental Fatigue and Perceptions of Job InsecurityDokumen23 halamanEmployee Mental Fatigue and Perceptions of Job InsecurityOzan DinçerBelum ada peringkat

- Referat 1 LB EnglezaDokumen4 halamanReferat 1 LB Englezacristodor georgianaBelum ada peringkat

- An Exploratory Study of CC WLOC OC PublishDokumen10 halamanAn Exploratory Study of CC WLOC OC PublishVirgil GheorgheBelum ada peringkat

- Safety and Health at Work: Basak Yanar, Morgan Lay, Peter M. SmithDokumen8 halamanSafety and Health at Work: Basak Yanar, Morgan Lay, Peter M. SmithDaniela CumbalazaBelum ada peringkat

- 1 s2.0 S2093791117301038 MainDokumen6 halaman1 s2.0 S2093791117301038 MainRobert Zapata PatronBelum ada peringkat

- Organizational Climate, Job Motivation and Organizational Citizenship BehaviorDokumen14 halamanOrganizational Climate, Job Motivation and Organizational Citizenship BehaviorRudine Pak MulBelum ada peringkat

- Quality of Working Life and Related Concepts:, andDokumen10 halamanQuality of Working Life and Related Concepts:, andshmpa20Belum ada peringkat

- Relationship Between Management Style and Organizational Performance: A Case Study From PakistanDokumen4 halamanRelationship Between Management Style and Organizational Performance: A Case Study From PakistanSamiuddin KhanBelum ada peringkat

- Correlation Between Employee Performance Well-BeinDokumen14 halamanCorrelation Between Employee Performance Well-BeinLawal CafeBelum ada peringkat

- Stress Management and Employee Engagement - A Study Case-Chance For Change Conference 19.9Dokumen10 halamanStress Management and Employee Engagement - A Study Case-Chance For Change Conference 19.9natalie_c_postruznik100% (1)

- 2010 Safety Citizenship Behaviour A Proactive Approach To Risk Management PDFDokumen10 halaman2010 Safety Citizenship Behaviour A Proactive Approach To Risk Management PDFNASIR KHANBelum ada peringkat

- The Role of Organizational Climate and Its Impact On Industrial TurnoverDokumen12 halamanThe Role of Organizational Climate and Its Impact On Industrial TurnoverRanjana BandaraBelum ada peringkat

- Determinants of Organizational Commitment in Banking Sector: I J A RDokumen7 halamanDeterminants of Organizational Commitment in Banking Sector: I J A RjionBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 2 Business ResearchDokumen21 halamanChapter 2 Business Researchwolfey cloudBelum ada peringkat

- Abhinav: Volume III, January'14 ISSN - 2320-0073Dokumen9 halamanAbhinav: Volume III, January'14 ISSN - 2320-0073Ionut-Marius DutanBelum ada peringkat

- International Journal of Business and Management Studies Vol 4, No 2, 2012 ISSN: 1309-8047 (Online)Dokumen12 halamanInternational Journal of Business and Management Studies Vol 4, No 2, 2012 ISSN: 1309-8047 (Online)Onyeka1234Belum ada peringkat

- Job Satisfaction and Work Locus of Control An Empirical Study Among Employees of Automotive Industries in IndiaDokumen8 halamanJob Satisfaction and Work Locus of Control An Empirical Study Among Employees of Automotive Industries in IndiaIAEME PublicationBelum ada peringkat

- Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction of JobDokumen8 halamanSatisfaction and Dissatisfaction of Jobhanif khanBelum ada peringkat

- Challenges and Needs For Support in Managing Occupational Health and Safety From Managers' ViewpointsDokumen21 halamanChallenges and Needs For Support in Managing Occupational Health and Safety From Managers' ViewpointsMohd Yazid Mohamad YunusBelum ada peringkat

- Tailoring Psychosocial Risk Assessment in The Oil and Gas - 2018 - Safety and HDokumen8 halamanTailoring Psychosocial Risk Assessment in The Oil and Gas - 2018 - Safety and HNaol TesfayeBelum ada peringkat

- Block FDokumen1 halamanBlock FNorazela HamadanBelum ada peringkat

- OUM Business School Semester Research Methods AssignmentDokumen24 halamanOUM Business School Semester Research Methods AssignmentNorazela HamadanBelum ada peringkat

- D - Main SignageDokumen1 halamanD - Main SignageNorazela HamadanBelum ada peringkat

- Building Alphabet LabellingDokumen1 halamanBuilding Alphabet LabellingNorazela HamadanBelum ada peringkat

- Assignment Bmst5103 Strategic Management 1Dokumen22 halamanAssignment Bmst5103 Strategic Management 1Norazela Hamadan100% (3)

- Ikea HRMDokumen10 halamanIkea HRMNorazela HamadanBelum ada peringkat

- Causes and Effects of Delays in Malaysian Construction IndustryDokumen10 halamanCauses and Effects of Delays in Malaysian Construction IndustryRenuka MuthalvanBelum ada peringkat

- Defining International Human Resource DevelopmentDokumen8 halamanDefining International Human Resource DevelopmentNorazela HamadanBelum ada peringkat

- Human Resource Management Bmhr5103Dokumen14 halamanHuman Resource Management Bmhr5103Norazela HamadanBelum ada peringkat

- Assignment Bmod5103 Odc 1Dokumen23 halamanAssignment Bmod5103 Odc 1Norazela HamadanBelum ada peringkat

- Ikea HRMDokumen10 halamanIkea HRMNorazela HamadanBelum ada peringkat

- Meis PDFDokumen98 halamanMeis PDFNorazela HamadanBelum ada peringkat

- Assignment Submission and AssessmentDokumen4 halamanAssignment Submission and AssessmentNorazela HamadanBelum ada peringkat

- Strategic Execution and PeopleDokumen9 halamanStrategic Execution and PeopleNorazela HamadanBelum ada peringkat

- Stategic Execution and Leadership at GoogleDokumen10 halamanStategic Execution and Leadership at GoogleNorazela HamadanBelum ada peringkat

- Marketing Plan Template for Mobile Phone or Airline Company (BMMK5103Dokumen4 halamanMarketing Plan Template for Mobile Phone or Airline Company (BMMK5103Norazela HamadanBelum ada peringkat

- Assignment Question - Business AcountingDokumen6 halamanAssignment Question - Business AcountingNorazela HamadanBelum ada peringkat

- Spain Final BriefDokumen2 halamanSpain Final BriefNorazela HamadanBelum ada peringkat

- Acute k9 Pain ScaleDokumen1 halamanAcute k9 Pain Scaleapi-367949035Belum ada peringkat

- BSc Medical Sociology Syllabus DetailsDokumen24 halamanBSc Medical Sociology Syllabus Detailsmchakra72100% (2)

- Sop Cleaning Rev 06 - 2018 Rev Baru (Repaired)Dokumen20 halamanSop Cleaning Rev 06 - 2018 Rev Baru (Repaired)FajarRachmadiBelum ada peringkat

- Complications of Caesarean Section: ReviewDokumen8 halamanComplications of Caesarean Section: ReviewDesi Purnamasari YanwarBelum ada peringkat

- ASHRAE Std 62.1 Ventilation StandardDokumen38 halamanASHRAE Std 62.1 Ventilation Standardcoolth2Belum ada peringkat

- Turn Around Time of Lab: Consultant Hospital ManagementDokumen22 halamanTurn Around Time of Lab: Consultant Hospital ManagementAshok KhandelwalBelum ada peringkat

- Hortatory Exposition Humaira AssahdaDokumen4 halamanHortatory Exposition Humaira Assahdaaleeka auroraBelum ada peringkat

- EnvironHealthLinkDokumen18 halamanEnvironHealthLinkKarthik BaluBelum ada peringkat

- Corn SpecDokumen4 halamanCorn SpecJohanna MullerBelum ada peringkat

- Ulrich Merzenich2007Dokumen13 halamanUlrich Merzenich2007oka samiranaBelum ada peringkat

- Project WorkPlan Budget Matrix ENROLMENT RATE SAMPLEDokumen3 halamanProject WorkPlan Budget Matrix ENROLMENT RATE SAMPLEJon Graniada60% (5)

- State Act ListDokumen3 halamanState Act Listalkca_lawyer100% (1)

- Building An ArgumentDokumen9 halamanBuilding An ArgumentunutulmazBelum ada peringkat

- Chronic Bacterial Prostatitis: Causes, Symptoms, and TreatmentDokumen9 halamanChronic Bacterial Prostatitis: Causes, Symptoms, and TreatmentAnonymous gMLTpER9IUBelum ada peringkat

- Improving Healthcare Quality in IndonesiaDokumen34 halamanImproving Healthcare Quality in IndonesiaJuanaBelum ada peringkat

- DMDFDokumen22 halamanDMDFsujal177402100% (1)

- EpididymitisDokumen8 halamanEpididymitisShafira WidiaBelum ada peringkat

- Dr. LakshmayyaDokumen5 halamanDr. LakshmayyanikhilbBelum ada peringkat

- Certification of Psychology Specialists Application Form: Cover PageDokumen3 halamanCertification of Psychology Specialists Application Form: Cover PageJona Mae MetroBelum ada peringkat

- Reactive Orange 16Dokumen3 halamanReactive Orange 16Chern YuanBelum ada peringkat

- Civil Tender Volume-1Dokumen85 halamanCivil Tender Volume-1Aditya RaghavBelum ada peringkat

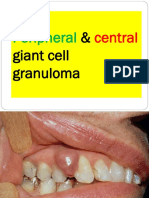

- Peripheral Central Giant Cell Granuloma NXPowerLiteDokumen18 halamanPeripheral Central Giant Cell Granuloma NXPowerLiteAFREEN SADAF100% (1)

- Working Heights Fall Arrest Systems PDFDokumen4 halamanWorking Heights Fall Arrest Systems PDFPraful E. PawarBelum ada peringkat

- Agile Project Management: Course 4. Agile Leadership Principles and Practices Module 3 of 4Dokumen32 halamanAgile Project Management: Course 4. Agile Leadership Principles and Practices Module 3 of 4John BenderBelum ada peringkat

- Testing Antibiotics with Disk Diffusion AssayDokumen3 halamanTesting Antibiotics with Disk Diffusion AssayNguyễn Trung KiênBelum ada peringkat

- Rostering Process FlowchartDokumen1 halamanRostering Process FlowchartByte MeBelum ada peringkat

- Manage WHS Operations - Assessment 2 - v8.2Dokumen5 halamanManage WHS Operations - Assessment 2 - v8.2Daniela SanchezBelum ada peringkat

- NOAA Sedimento 122 Squirt CardsDokumen12 halamanNOAA Sedimento 122 Squirt CardshensilBelum ada peringkat

- Mixed Connective Tissue DZ (SLE + Scleroderma)Dokumen7 halamanMixed Connective Tissue DZ (SLE + Scleroderma)AshbirZammeriBelum ada peringkat

- Ontario Works Service Delivery Model CritiqueDokumen14 halamanOntario Works Service Delivery Model CritiquewcfieldsBelum ada peringkat

- How to Talk to Anyone at Work: 72 Little Tricks for Big Success Communicating on the JobDari EverandHow to Talk to Anyone at Work: 72 Little Tricks for Big Success Communicating on the JobPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (36)

- Summary: Choose Your Enemies Wisely: Business Planning for the Audacious Few: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisDari EverandSummary: Choose Your Enemies Wisely: Business Planning for the Audacious Few: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (3)

- The Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverDari EverandThe Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (186)

- The Power of People Skills: How to Eliminate 90% of Your HR Problems and Dramatically Increase Team and Company Morale and PerformanceDari EverandThe Power of People Skills: How to Eliminate 90% of Your HR Problems and Dramatically Increase Team and Company Morale and PerformancePenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (22)

- The Introverted Leader: Building on Your Quiet StrengthDari EverandThe Introverted Leader: Building on Your Quiet StrengthPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (35)

- Spark: How to Lead Yourself and Others to Greater SuccessDari EverandSpark: How to Lead Yourself and Others to Greater SuccessPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (130)

- The First Minute: How to start conversations that get resultsDari EverandThe First Minute: How to start conversations that get resultsPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (55)

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective PeopleDari EverandThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective PeoplePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (2564)

- Work Stronger: Habits for More Energy, Less Stress, and Higher Performance at WorkDari EverandWork Stronger: Habits for More Energy, Less Stress, and Higher Performance at WorkPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (12)

- Billion Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn from the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last Twenty-five YearsDari EverandBillion Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn from the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last Twenty-five YearsPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (52)

- The 12 Week Year: Get More Done in 12 Weeks than Others Do in 12 MonthsDari EverandThe 12 Week Year: Get More Done in 12 Weeks than Others Do in 12 MonthsPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (410)

- Transformed: Moving to the Product Operating ModelDari EverandTransformed: Moving to the Product Operating ModelPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- 7 Principles of Transformational Leadership: Create a Mindset of Passion, Innovation, and GrowthDari Everand7 Principles of Transformational Leadership: Create a Mindset of Passion, Innovation, and GrowthPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (51)

- Leadership Skills that Inspire Incredible ResultsDari EverandLeadership Skills that Inspire Incredible ResultsPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (11)

- The ONE Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary Results: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedDari EverandThe ONE Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary Results: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (124)

- Management Mess to Leadership Success: 30 Challenges to Become the Leader You Would FollowDari EverandManagement Mess to Leadership Success: 30 Challenges to Become the Leader You Would FollowPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (27)

- Scaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't, Rockefeller Habits 2.0Dari EverandScaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't, Rockefeller Habits 2.0Belum ada peringkat

- The 4 Disciplines of Execution: Revised and Updated: Achieving Your Wildly Important GoalsDari EverandThe 4 Disciplines of Execution: Revised and Updated: Achieving Your Wildly Important GoalsPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (47)

- The Emotionally Intelligent LeaderDari EverandThe Emotionally Intelligent LeaderPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (203)

- How to Lead: Wisdom from the World's Greatest CEOs, Founders, and Game ChangersDari EverandHow to Lead: Wisdom from the World's Greatest CEOs, Founders, and Game ChangersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (94)

- Transformed: Moving to the Product Operating ModelDari EverandTransformed: Moving to the Product Operating ModelPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- The 12 Week Year: Get More Done in 12 Weeks than Others Do in 12 MonthsDari EverandThe 12 Week Year: Get More Done in 12 Weeks than Others Do in 12 MonthsPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (90)

- Systems Thinking For Social Change: A Practical Guide to Solving Complex Problems, Avoiding Unintended Consequences, and Achieving Lasting ResultsDari EverandSystems Thinking For Social Change: A Practical Guide to Solving Complex Problems, Avoiding Unintended Consequences, and Achieving Lasting ResultsPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (38)

- Unlocking Potential: 7 Coaching Skills That Transform Individuals, Teams, & OrganizationsDari EverandUnlocking Potential: 7 Coaching Skills That Transform Individuals, Teams, & OrganizationsPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (27)

- Good to Great by Jim Collins - Book Summary: Why Some Companies Make the Leap...And Others Don'tDari EverandGood to Great by Jim Collins - Book Summary: Why Some Companies Make the Leap...And Others Don'tPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (63)