EPaper Non Verbal Communication Fact-Fiction-Misunderstanding Yaffe

Diunggah oleh

Richie KuruvillaJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

EPaper Non Verbal Communication Fact-Fiction-Misunderstanding Yaffe

Diunggah oleh

Richie KuruvillaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Ubiquity, an ACM publication

October, 2011

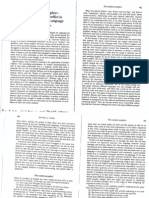

The 7% Rule: Fact, Fiction, or Misunderstanding

by Philip Yaffe

Editors Introduction

In 1971, Albert Mehrabian published a book Silent Messages, in which he discussed his research

on non-verbal communication. He concluded that prospects based their assessments of

credibility on factors other than the words the salesperson spokethe prospects studied assigned

55 percent of their weight to the speakers body language and another 38 percent to the tone and

music of their voice. They assigned only 7 percent of their credibility assessment to the

salespersons actual words. Over the years, this limited experiment evolved to a belief that

movement and voice coaches would be more valuable to teaching successful communication than

speechwriters. In fact, in 2007 Allen Weiner published So Smart But discussing how to put

this principle to work in organizations.

Phil Yaffe thinks that the 7 percent rule is a pernicious myth. He debunks the notion that in an

oral presentation, what you say is considerably less important than how you say it. He rejects the

claim that content accounts for only 7 percent of the success of the presentation, while 93

percent of success is attributable to non-verbal factors, i.e. body language and vocal variety. The

myth arises from a gross misinterpretation of a scientific experiment. It needs to be put to rest

both for the benefit of presenters and the sake of scientific integrity.

Peter J. Denning

Editor

http://ubiquity.acm.org

2011 Association for Computing Machinery

Ubiquity, an ACM publication

October, 2011

The 7% Rule: Fact, Fiction, or Misunderstanding

by Philip Yaffe

Have you ever heard the adage that communication is only 7 percent verbal and 93 percent

non-verbal, i.e. body language and vocal variety? You probably have, and if you have any sense

at all, you have ignored it.

There are certain "truths" that are prima face false. And this is one of them. Asserting that what

you say is the least important part of a speech insults not only the intelligence of your audience,

but your own intelligence as well.

The whole objective of most speeches is to convey information, or to promote or defend a

point of view. Certainly, proper vocal variety and body language can aid the process. But by

their very nature, these ancillary activities can convey only emphasis or emotion.

The proof? Although today we presumably live in a visual world, most information is still

promulgated in written form, where vocal variety and body language play no role. Even the

"interactive" Internet is still mainly writing. The vast majority of people who surf the Internet do

so looking for texts, with which they may interact via hyperlinks, but it is still essentially text.

Likewise with a speech. If your words are incapable of getting your message across, then no

amount of gestures and tonal variations will do it for you. You are still obliged to carefully

structure your information and look for "le mot juste" (the best words or phrases) to express

what you want to say.

So just what does this "7% Rule" really mean?

The origin of this inimical adage is a misinterpretation, like the adage "the exception that

proves the rule." This is something else people say without examining it. If you believe that this

is actually true, I will demonstrate at the end of this article that it isn't. But first things first.

In the 1960s Professor Albert Mehrabian and colleagues at the University of California, Los

Angles (UCLA), conducted studies into human communication patterns. When their results

were published in professional journals in 1967, they were widely circulated across mass media

in abbreviated form. Because the figures were so easy to remember, most people forgot about

what they really meant. Hence, the myth that communication is only 7 percent verbal and 93

http://ubiquity.acm.org

2011 Association for Computing Machinery

Ubiquity, an ACM publication

October, 2011

percent non-verbal was born. And we have been suffering from it ever since.

The fact is Professor Mehrabian's research had nothing to do with giving speeches, because it

was based on the information that could be conveyed in a single word.

Subjects were asked to listen to a recording of a woman's voice saying the word maybe three

different ways to convey liking, neutrality, and disliking. They were also shown photos of the

woman's face conveying the same three emotions. They were then asked to guess the

emotions heard in the recorded voice, seen in the photos, and both together. The result? The

subjects correctly identified the emotions 50 percent more often from the photos than from

the voice.

In the second study, subjects were asked to listen to nine recorded words, three meant to

convey liking (honey, dear, thanks), three to convey neutrality (maybe, really, oh), and three to

convey disliking (dont, brute, terrible). Each word was pronounced three different ways. When

asked to guess the emotions being conveyed, it turned out that the subjects were more

influenced by the tone of voice than by the words themselves.

Professor Mehrabian combined the statistical results of the two studies and came up with the

now famousand famously misusedrule that communication is only 7 percent verbal and 93

percent non-verbal. The non-verbal component was made up of body language (55 percent)

and tone of voice (38 percent).

Actually, it is incorrect to call this a "rule," being the result of only two studies. Scientists usually

insist on many more corroborating studies before calling anything a rule.

More to the point, Professor Mehrabian's conclusion was that for inconsistent or contradictory

communications, body language and tonality may be more accurate indicators of meaning and

emotions than the words themselves. However, he never intended the results to apply to

normal conversation. And certainly not to speeches, which should never be inconsistent or

contradictory!

So what can we learn from this research to help us become better speakers?

Basically, nothing. We must still rely on what good orators have always known. A speech that is

confused and disorganized is a poor speech, no matter how well it is delivered. The essence of a

http://ubiquity.acm.org

2011 Association for Computing Machinery

Ubiquity, an ACM publication

October, 2011

good speech is what it says. This can be enhanced by vocal variety and appropriate gestures.

But these are auxiliary, not primary.

Toastmasters International, a worldwide club dedicated to improving public speaking, devotes

the first four chapters of its beginners manual to organizing the speech itself, including a

chapter specifically on the importance of words in conveying meaning and feeling. Only in

Chapter 5 and Chapter 6 does it concern itself with body language and vocal variety.

I don't know how to quantify the relative importance of verbal to non-verbal in delivering

speeches. But I have no doubt that the verbal (what you actually say) must dominate by a wide

margin.

One of the most famous speeches of all time is Abraham Lincolns Gettysburg Address. Its

272 words continue to inspire 150 years after they were spoken. No one has the slightest idea

of Lincolns movements or voice tones.

Now, what about that other oft-quoted misconception "the exception that proves the rule?

If you reflect for a moment, you will realize that an exception can never prove a rule; it can only

disprove it. For example, what happens when someone is decapitated? He dies, right? And we

know that this rule holds, because at least once in history when someone's head was chopped

off, he didn't die!

The problem is not with the adage, but with the language. In old English the term "prove"

meant to test, not to confirm as it does today. So the adage really means: "It is the exception

that tests the rule." If there is an exception, then there is no rule, or at least the rule is not total.

Native English speakers are not alone in continuing to mouth this nonsense; in some other

languages it is even worse. For example, the French actually say "the exception that confirms

the rule" (l'exception qui confirme la rgle), probably because it was mistranslated from English.

This is quite unequivocal, leaving no room for doubt. But it is still wrong.

http://ubiquity.acm.org

2011 Association for Computing Machinery

Ubiquity, an ACM publication

October, 2011

About the Author

Philip Yaffe was born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1942 and grew up in Los Angeles, where he

graduated from the University of California with a degree in mathematics and physics. In his

senior year, he was also editor-in-chief of the Daily Bruin, UCLAs daily student newspaper. He

has more than 40 years of experience in journalism and international marketing

communication. At various points in his career, he has been a teacher of journalism, a

reporter/feature writer with The Wall Street Journal, an account executive with a major

international press relations agency, European marketing communication director with two

major international companies, and a founding partner of a specialized marketing

communication agency in Brussels, Belgium, where he has lived since 1974. Among Yaffes

recent books are The Gettysburg Approach to Writing & Speaking like a Professional and

Science for the Concerned Citizen (available from Amazon Kindle).

DOI: 10.1145/2043155.2043156

http://ubiquity.acm.org

2011 Association for Computing Machinery

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Black PearlDokumen264 halamanBlack Pearlapi-26421590100% (3)

- Forms of Talk (PDFDrive)Dokumen342 halamanForms of Talk (PDFDrive)Yechezkel Madanes100% (1)

- Discourse CommunityDokumen3 halamanDiscourse Communityapi-271986381Belum ada peringkat

- PRELIM MODULE - Purposive CommunicationDokumen5 halamanPRELIM MODULE - Purposive CommunicationTimoteo Ponce Mejorada Jr.Belum ada peringkat

- After Mehrabian: Nonverbal Communication ResearchDokumen7 halamanAfter Mehrabian: Nonverbal Communication ResearchljiljanasimicderuBelum ada peringkat

- Communication in An OrganizationDokumen9 halamanCommunication in An Organizationwaleed latifBelum ada peringkat

- Communication: Messages. But The Three V's Don't Always Line Up. Think AboutDokumen2 halamanCommunication: Messages. But The Three V's Don't Always Line Up. Think AboutsyafiqBelum ada peringkat

- Importance of Body LanguageDokumen1 halamanImportance of Body Languagebalu4indians100% (3)

- BODY TALK The Body Language Skills To Decode The Opposite Sex, Detect Lies, and Read Anyone Like A Book by Patrick King PDFDokumen92 halamanBODY TALK The Body Language Skills To Decode The Opposite Sex, Detect Lies, and Read Anyone Like A Book by Patrick King PDFdisspel 90Belum ada peringkat

- The Structure of ConversationDokumen7 halamanThe Structure of ConversationMario Reztu Prayogi100% (1)

- The Secret Life of PronounsDokumen4 halamanThe Secret Life of PronounsARFANBelum ada peringkat

- Using APpropriate LanguageDokumen25 halamanUsing APpropriate LanguageVerna Dell CorpuzBelum ada peringkat

- The Analysis of Metaphor in Steve Jobs SpeechDokumen18 halamanThe Analysis of Metaphor in Steve Jobs SpeechI Gede Perdana Putra NarayanaBelum ada peringkat

- Oral PresentationDokumen18 halamanOral Presentationbabal18304Belum ada peringkat

- Body Language: Read People Like a Book and Detect Their Thoughts (volume 1)Dari EverandBody Language: Read People Like a Book and Detect Their Thoughts (volume 1)Belum ada peringkat

- Language and Gender Instructor: DR - Fatima Baig Topic: Group 5: Zuria Gul 5, Asifa 13, Maryam 17, ShewanaDokumen15 halamanLanguage and Gender Instructor: DR - Fatima Baig Topic: Group 5: Zuria Gul 5, Asifa 13, Maryam 17, ShewanaKainat JameelBelum ada peringkat

- Reading Responses PG 147-176 English102Dokumen4 halamanReading Responses PG 147-176 English102api-254422428Belum ada peringkat

- Toward A Philosophy of CommunicationDokumen4 halamanToward A Philosophy of CommunicationEtranger15Belum ada peringkat

- Language & Power 3Dokumen3 halamanLanguage & Power 3Albert EnglisherBelum ada peringkat

- "Tang Ina Mo! To Tang Ina": Degradation of Curses To Speech DisfluenciesDokumen6 halaman"Tang Ina Mo! To Tang Ina": Degradation of Curses To Speech DisfluenciesCharmaine berBelum ada peringkat

- Research Paper Topics On Body LanguageDokumen5 halamanResearch Paper Topics On Body Languagecajzsqp2100% (1)

- Reflective Essay On English ClassDokumen8 halamanReflective Essay On English Classfz6etcq7100% (2)

- (Analysis) FaircloughDokumen5 halaman(Analysis) FaircloughAinosalam SeradBelum ada peringkat

- Feby Rahmayanti - Week 15Dokumen4 halamanFeby Rahmayanti - Week 15Maulida fitriahBelum ada peringkat

- Body Language: Avoid Miscommunication, Improve Personal Relationships, and Learn to Read People (Volume 1,2, and 3)Dari EverandBody Language: Avoid Miscommunication, Improve Personal Relationships, and Learn to Read People (Volume 1,2, and 3)Belum ada peringkat

- All in SourceDokumen115 halamanAll in SourceJohn Ryan YumulBelum ada peringkat

- Ucspngbuhaymo PDFDokumen281 halamanUcspngbuhaymo PDFFrancis EsperanzaBelum ada peringkat

- Secsem Theater l5-l6Dokumen23 halamanSecsem Theater l5-l6SpearBBelum ada peringkat

- Jennifer Mather Saul - Lying, Misleading, and What Is Said - An Exploration in Philosophy of Language and in Ethics-Oxford University Press (2012)Dokumen161 halamanJennifer Mather Saul - Lying, Misleading, and What Is Said - An Exploration in Philosophy of Language and in Ethics-Oxford University Press (2012)Carlos Augusto AfonsoBelum ada peringkat

- EthnomethodologyDokumen2 halamanEthnomethodologycollit718Belum ada peringkat

- All in Source Grade 11 For All 1Dokumen109 halamanAll in Source Grade 11 For All 1Sheila Mae OrapaBelum ada peringkat

- UCSP Grade 11 Week 1-10Dokumen286 halamanUCSP Grade 11 Week 1-10Squad SquidBelum ada peringkat

- A Complete Guide To SI Vol 69Dokumen18 halamanA Complete Guide To SI Vol 69Rivaldi Yusdian SyahBelum ada peringkat

- Culture and Nonverbal Communication Learning Objectives:: LanguageDokumen12 halamanCulture and Nonverbal Communication Learning Objectives:: LanguageVee StringzBelum ada peringkat

- Steve Jobs 2005 Stanford Commencement AddressDokumen14 halamanSteve Jobs 2005 Stanford Commencement Addressapi-608912995Belum ada peringkat

- Day 5 Nonverbal Reading 1Dokumen13 halamanDay 5 Nonverbal Reading 1Abhash JhaBelum ada peringkat

- Five Paragraph Expository Essay ModelDokumen8 halamanFive Paragraph Expository Essay Modelafabjgbtk100% (2)

- Reddy Conduit MetaphorDokumen21 halamanReddy Conduit MetaphorKara WentworthBelum ada peringkat

- Parsons (1982) - Are There Nonexistent ObjectsDokumen8 halamanParsons (1982) - Are There Nonexistent ObjectsTomas CastagninoBelum ada peringkat

- Theories: Chomsky's Universal GrammarDokumen4 halamanTheories: Chomsky's Universal Grammarmoin khanBelum ada peringkat

- Floods in Pakistan EssayDokumen5 halamanFloods in Pakistan Essayuwuxovwhd100% (2)

- Artículo Nonverbal CommunicationDokumen4 halamanArtículo Nonverbal CommunicationMolinetasBelum ada peringkat

- THESISDokumen4 halamanTHESISMeache-Ann AticoBelum ada peringkat

- The Mehrabian Myth and The Real Secret To Effective Communication, Part 1Dokumen4 halamanThe Mehrabian Myth and The Real Secret To Effective Communication, Part 1Deepak VindalBelum ada peringkat

- Non-Verbal CommunicationDokumen17 halamanNon-Verbal CommunicationJosh Ann Marie Yerro-Aguilar100% (2)

- Non-Verbal CommunicationDokumen21 halamanNon-Verbal Communicationilona yevtushenkoBelum ada peringkat

- Tugas 1 (Reading Ii)Dokumen3 halamanTugas 1 (Reading Ii)Michelle100% (1)

- Chapter 1 Gec 5Dokumen17 halamanChapter 1 Gec 5Mabini BernadaBelum ada peringkat

- Non Verbal CommunicationDokumen8 halamanNon Verbal CommunicationHammad HanifBelum ada peringkat

- Ucsp Week 1 10Dokumen287 halamanUcsp Week 1 10Andrea NombreBelum ada peringkat

- (AMALEAKS - BLOGSPOT.COM) UCSP Week 1-10Dokumen281 halaman(AMALEAKS - BLOGSPOT.COM) UCSP Week 1-10Luna MaeBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding Body Language: Physical ExpressionDokumen9 halamanUnderstanding Body Language: Physical ExpressionRohit GroverBelum ada peringkat

- Яроха Я. В Seminar 2 (23-34)Dokumen3 halamanЯроха Я. В Seminar 2 (23-34)Яна ЯрохаBelum ada peringkat

- Eapp 12Dokumen285 halamanEapp 12Jayson Lim II100% (3)

- The Body Language of CultureDokumen9 halamanThe Body Language of CultureMin PuBelum ada peringkat

- Body Language Research Paper TopicsDokumen5 halamanBody Language Research Paper Topicsaflbsybmc100% (1)

- An Experiment in Judging Intelligence by The VoiceDokumen8 halamanAn Experiment in Judging Intelligence by The VoiceMonta TupčijenkoBelum ada peringkat

- Od - ModesDokumen23 halamanOd - ModesRichie KuruvillaBelum ada peringkat

- Livelihood Inclusion of Rickshaw Pullers: Prosperity at The Bottom of The PyramidDokumen14 halamanLivelihood Inclusion of Rickshaw Pullers: Prosperity at The Bottom of The PyramidRichie KuruvillaBelum ada peringkat

- Student Pass Application Format PDFDokumen1 halamanStudent Pass Application Format PDFWasim AkramBelum ada peringkat

- EArticle - Metaverbal Messages in Personal InteractionsDokumen5 halamanEArticle - Metaverbal Messages in Personal InteractionsRichie KuruvillaBelum ada peringkat

- Intervention of Organisational DevelopmentDokumen10 halamanIntervention of Organisational DevelopmentRichie KuruvillaBelum ada peringkat

- Textile Industry: Ravikumar Richie Kuruvilla Ritu Pareek Sabir Babu Sachin BinoDokumen16 halamanTextile Industry: Ravikumar Richie Kuruvilla Ritu Pareek Sabir Babu Sachin BinoRichie KuruvillaBelum ada peringkat

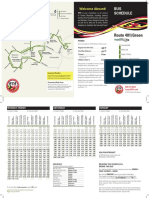

- CMD LFT Route-401 GreenfinalprintDokumen2 halamanCMD LFT Route-401 GreenfinalprintRichie KuruvillaBelum ada peringkat

- Textile Industry: Ravikumar Richie Kuruvilla Ritu Pareek Sabir Babu Sachin BinoDokumen16 halamanTextile Industry: Ravikumar Richie Kuruvilla Ritu Pareek Sabir Babu Sachin BinoRichie KuruvillaBelum ada peringkat

- Learning Dart - Second Edition - Sample ChapterDokumen30 halamanLearning Dart - Second Edition - Sample ChapterPackt Publishing100% (2)

- Ingles IIDokumen9 halamanIngles IIyayaBelum ada peringkat

- I. ObjectivesDokumen9 halamanI. ObjectivesCharity Anne Camille PenalozaBelum ada peringkat

- The Role of English in Intercultural CommunicationDokumen11 halamanThe Role of English in Intercultural CommunicationRizqa MahdynaBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson-Plan-Lesson 3Dokumen3 halamanLesson-Plan-Lesson 3api-311158073Belum ada peringkat

- Lab Report #2Dokumen9 halamanLab Report #2Tj ContrerasBelum ada peringkat

- DB2Dokumen332 halamanDB2api-26564177100% (1)

- Introduction To Microprocessor 8085Dokumen23 halamanIntroduction To Microprocessor 8085GousAttarBelum ada peringkat

- Project Proposal of Grade 2Dokumen2 halamanProject Proposal of Grade 2Phoem RayosBelum ada peringkat

- If Clause As Imperative and SuggestionDokumen9 halamanIf Clause As Imperative and SuggestionPutri100% (1)

- Ari ResumeDokumen3 halamanAri Resumeapi-3712982Belum ada peringkat

- About//around/in/to/towards Beside/towards/to/along: He Ran The Field. He Is Walking The DoorDokumen39 halamanAbout//around/in/to/towards Beside/towards/to/along: He Ran The Field. He Is Walking The DoorAnimalBelum ada peringkat

- What Is Entropic PoetryDokumen9 halamanWhat Is Entropic PoetryÖzcan TürkmenBelum ada peringkat

- Toleransi Islam Menurut Pandangan Al Quran As Sunnah PDFDokumen27 halamanToleransi Islam Menurut Pandangan Al Quran As Sunnah PDFHelmon ChanBelum ada peringkat

- Subject Verb AgreementDokumen35 halamanSubject Verb AgreementDANNYBelum ada peringkat

- Implicit and Explicit InformationDokumen3 halamanImplicit and Explicit InformationAbbas GholamiBelum ada peringkat

- Cambridge Common Mistakes at Cae - English Time SchoolDokumen33 halamanCambridge Common Mistakes at Cae - English Time Schoolmanchiraju raj kumarBelum ada peringkat

- Pmake - A Tutorial: Adam de BoorDokumen42 halamanPmake - A Tutorial: Adam de Boorbookaccount0Belum ada peringkat

- SF1 - 2020 - Grade 7 (Year I) - THALESDokumen3 halamanSF1 - 2020 - Grade 7 (Year I) - THALESRinalyn JintalanBelum ada peringkat

- MySQL BasicDokumen27 halamanMySQL BasicdharmendardBelum ada peringkat

- BS en 15643-3-2012Dokumen32 halamanBS en 15643-3-2012h5f686pcvpBelum ada peringkat

- WorksheetsDokumen13 halamanWorksheetsMIRZAYANTIE BINTI MOHD NOH MoeBelum ada peringkat

- Python Casting: Specify A Variable TypeDokumen5 halamanPython Casting: Specify A Variable TypehimanshuBelum ada peringkat

- Students Can Practice Using EnglishDokumen3 halamanStudents Can Practice Using EnglishGillian BienvinutoBelum ada peringkat

- MS4 Level Reporting Event (File Six) Present PerfectDokumen4 halamanMS4 Level Reporting Event (File Six) Present PerfectMr Samir Bounab100% (4)

- Setting, Scene and AtmosphereDokumen55 halamanSetting, Scene and AtmosphereJrick EscobarBelum ada peringkat

- 149 Grammar Unit 1 3starDokumen1 halaman149 Grammar Unit 1 3starLourdes Rubio CallejónBelum ada peringkat

- Republic of The Philippines Province of AuroraDokumen4 halamanRepublic of The Philippines Province of Aurorakevin ray sabadoBelum ada peringkat

- Customs Manners and Etiquette in MalaysiaDokumen24 halamanCustoms Manners and Etiquette in Malaysiaeidelwaiz tiaraniBelum ada peringkat