232 570 2 PB

Diunggah oleh

lisa chanJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

232 570 2 PB

Diunggah oleh

lisa chanHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Received: 5 Nov.

2015

Accepted: 7 Mar. 2016

The prevalence and risk factors of gingivitis in a population of

6-year-old children in Iran

Fatemeh Jahanimoghadam DDS, MSc1, Hoda Shamsaddin DDS, MSc1

Original Article

Abstract

Gingivitis is a reversible inflammation of gingival tissue. The prevalence of gingivitis is

different in various communities. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of gingivitis among 6-year-old

( 3 months) children of Rayen, Kerman, Iran.

BACKGROUND AND AIM:

In this cross sectional study, 279 children (129 boys and 150 girls) from all Rayens nursery schools and

primary schools were selected. Data collected through clinical examination with the consent of parents and teachers.

Gingival Bleeding Index (GBI) was measured by using light and dental probe pressure.

METHODS:

The prevalence of gingivitis was 37.8. There was statistically significant association between gender and

gingivitis. Mouth breathing and toothbrush frequency were factors associated with gingivitis.

RESULTS:

This study showed relatively similar prevalence of gingivitis compared to other studies. The prevalence

of gingivitis was more in boys than girls. Health educators and parents should have a more active role in childrens oral

health education.

CONCLUSION:

KEYWORDS:

Gingivitis; Prevalence; Mouth Breathing; Children; Gender

Citation: Jahanimoghadam F, Shamsaddin H. The prevalence and risk factors of gingivitis in a

population of 6-year-old children in Iran. J Oral Health Oral Epidemiol 2016; 5(3): 129-33.

ingivitis is a reversible inflammation

of gingival tissue characterized by

swelling, bleeding, change in normal

colour, and often sensitivity and

tenderness.1 Histologically it is characterized by

the presence of an inflammatory exudate and

edema, some destruction of collagenous

gingival fibers, ulceration and proliferation of

the epithelium facing the tooth.2 The most

common form of periodontal disease in

children is plaque induced gingivitis.3

Cariogenic bacteria, food impaction, mouth

breathing and improper tooth position are the

predisposing factors reasonable for this type of

gingival disease.4 The inflammation of tooth

surrounding tissues can spread to bone and

results in loss of connective tissues and bone.5

The role of poor oral hygiene and dental plaque

in gingivitis formation has been well

established.1 Gingival health can be maintained

with good oral hygiene. The prevalence of

gingivitis is different in various communities.

Most studies have reported it up to 50%-100%.6.

In developed countries, the prevalence and

severity of gingivitis are widely investigated at

different ages. The prevalence of gingivitis in

children has mentioned from 61.5% in the USA

to 85% in Australia, 70% in Mexico, and 95% in

India.7 In contrast to many developed

countries, high prevalence of gingivitis has

been reported in Iranian children.1

Jalaleddin and Ramezani showed that the

gingivitis prevalence is 97% in 6- to 7-year-old

children in Qazvin, Iran.8 Ketabi reported the

prevalence of gingivitis was 73% among 6- to

11-year-old children in Isfahan.7 Four indices

1- Assistant Professor, Oral and Dental Diseases Research Center AND Kerman Social Determinants on Oral Health Research Center

AND Department of Pediatric Dentistry, School of Dentistry, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran

Correspondence to: Fatemeh Jahanimoghadam DDS, MSc

Email: fatemehjahani4@gmail.com

J Oral Health Oral Epidemiol/ Summer 2016; Vol. 5, No. 3

http://johoe.kmu.ac.ir,

5 June

129

The prevalence and risk factors of gingivitis

commonly used to evaluate gingival

inflammation in children and young adults in

recent studies are: Gingival Index (GI) (Loe

and Silness,1963), Gingivitis Index (Suomi and

Barbano ,1968), Papillary Bleeding Index (PBI)

(Saxer and Muhlemann, 1975), and Gingival

Bleeding Index (GBI) (Ainamo and Bay, 1976).

The index described by Ainamo and Bay,

considers presence or absence of bleeding on

gentle probing of the gingival tissue. GBI has

proved to be useful in a number of

epidemiological and clinical trials. The

diagnostic criteria (bleeding or no bleeding)

are assumed to be relatively easy to interpret.

Thus, this index is assumed to be relatively

insensitive

to

examiner

differences.9

Furthermore,

researchers

suggest

that

bleeding upon gentle probing of the gingival

sulcus may occur before change in the colour,

texture, or form.10 So GBI was used to assess

the bleeding in this study.

Considering the high prevalence in this age

group, the present study tends to evaluate

prevalence and risk factors of gingivitis

among 6-year-old children. It seems that

factors such as family income and

socioeconomic status would influence on

prevalence.11 It was considered necessary to

develop a research study that would describe

the prevalence of gingivitis in a preschool age

population for a better screening in the design

of intervention programs to limit the

healthcare

problem

represented

by

periodontal disease. We assume that in

deprived area such as some rustic regions the

level of parents awareness about childrens

oral health practice is low and lead to higher

level of dental caries and gingivitis. The aim of

this study was to evaluate the prevalence of

gingivitis in nursery schools and primary

schools of Rayen and increase level of parents

awareness about childrens oral health.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was carried out

among 6-year-old ( 3 months) children in

Rayen, one of the cities of Kerman, Iran.

130

Jahanimoghadam and Shamsaddin

Kerman Province is the largest Province in

Iran and is located in the south east of the

country and Rayen is located in the south east

of Kerman with a population of over 50000.

The racial structure of the population in this

city is heterogeneous. All 279 children aged 6

years ( 3 months) in all nursery schools and

primary schools of Rayen were selected

through census method. After getting the

consent of the schools authorities for

participation in our survey, informed consent

was obtained from the parents to include their

children in the study. The ethical code

(IR.KMU.REC.1394.245) was allocated to this

study by ethics committee of Kerman

University of medical sciences.

A

checklist

on

the

demographic

characteristics, gingival bleeding index (GBI),

habits, and systemic conditions were

completed by a trained examiner for 279

children. Full mouth examination was done

under natural light in a schools room and

using disposable mouth mirror and

periodontal probe (Williamscoded-Hufriedy,

USA). Participants who had systemic diseases

were not included. GBI was measured by

using light and dental probe pressure. In this

index, bleeding of marginal gingival cervices

in all teeth or selected teeth are measured.12 In

this study, GBI was measured in selected teeth

(51, 55, 65, 71, 75, 85). Zero score indicated the

absence of gingival bleeding within 10

seconds. Score 1 indicated that there was

bleeding in gingival margin of teeth. Total GBI

was calculated by dividing the number of sites

with hemorrhage on total number of tooth

sites and multiplying the result to hundred to

gain the percentage of gingival bleeding

index.12 Mobile teeth, teeth with gross caries

(more than 3 surfaces were lost) and teeth

during active phase of eruption were

excluded. Factors such as gender, mouth

breathing, and tooth brushing frequency were

evaluated. Lip seal or incompetency was used

for measuring mouth breathing index. Tooth

brushing frequency was asked from

participants. Lip seal or incompetency was

J Oral Health Oral Epidemiol / Summer 2016; Vol. 5, No. 3

http://johoe.kmu.ac.ir,

5 June

The prevalence and risk factors of gingivitis

Jahanimoghadam and Shamsaddin

used for measuring mouth breathing index.

Furthermore, parents were asked if their

children open their mouth when they sleep.

Tooth brushing frequency was asked from

participants and their parents.

Data was analyzed by analysis of variance

(ANOVA), post-hoc (Tukey test) and Students

t-test in SPSS (version 20.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago,

IL, USA). P-values of less than 0.05 was

considered to be statistically significant.

Results

In this study, the prevalence of gingivitis and

its related risk factors were determined in 279

children aged 6 years ( 3 months). The

prevalence of gingivitis was 37.8.

GBI was measured in boys and girls

(Table 1). Statistically significant difference in

GBI was seen between boys and girls. The

prevalence of gingivitis was more in boys

than girls, and this difference was statistically

significant (P = 0.005).

Children were divided in four different

groups based on toothbrush frequency:

1. Children who never used toothbrush or

any material to clean their teeth (G1).

2. Children who were sometimes using

toothbrush during a week (G2).

3. Children who were brushing their teeth

daily (G3).

4. Children who were brushing their teeth

twice or more a day (G4).

Statistically significant difference was seen

between G1 and G2, G3, G4 (P = 0.001). Tukey

test showed GBI difference was statistically

significant between G2 and G3 (P = 0.030) as

well as G2 and G4 (P = 0.009), but not for G3

and G4 (P = 0.950). Table 1 shows the

comparison of GBI mean according toothbrush

frequency. More than half (55.2%) of children

examined did not brush their teeth whereas

only 16.5% of them brushed twice or more a

day. GBI among mouth breather children was

significantly higher in comparison with nonmouth breathing group (P = 0.001).

Discussion

There is a lack of epidemiological studies about

periodontal status and gingival disease at

6-year-old age in Iran. Our results showed that

the prevalence of gingivitis was 37.8 among

6-year-old children. In other studies, this

prevalence was recorded 16.41% in Sarvabad, a

city in Kurdistan Province, Iran13 and 97% in

6- to 7-year-old children in Qazvin, Iran.8

Pourhashemi et al. found 95.7% of 6- to 10year-old children in Tehran, Iran, were affected

by gingivitis.14 It could be resulted from

different community and the age of subjects.

Gingivitis was more common in boys

which is in line with Taani,15 Ketabi et al.7, and

Rezaeian et al.13 studies. It may be due to more

precise oral hygiene cares in girls and less

motivation of oral hygiene practices in boys.15

Table 1. The comparison of GBI mean according to gender, mouth breathing and

toothbrush frequency

Variables

Gender

Mouth breathing

Toothbrush frequency

Groups

Number (%)

GBI mean (SD)

Boys

129 (46.23)

42.45 (35.29)

0.005

Girls

150 (53.76)

33.07 (37.46)

Yes

55 (19.71)

75.44 (18.09)

No

224 (80.28)

28.12 (34.07)

G1

154 (55.19)

64.15 (25.75)

G2

28 (10.03)

16.05 (24.28)

G3

51 (18.27)

0.81 (4.12)

G4

46 (16.48)

0 (0)

0.001

0.001

GBI: Gingival Bleeding Index; G1: Never; G2: Sometimes; G3: Daily; G4: Twice or more a day

J Oral Health Oral Epidemiol/ Summer 2016; Vol. 5, No. 3

http://johoe.kmu.ac.ir,

5 June

131

The prevalence and risk factors of gingivitis

We found that mouth breathing habit had

positive effect on gingival health. This result

is in agreement of Wagaiyu and Ashley16 and

Jacobson17 studies. An explanation of this

finding is dehydration of exposed surface of

gingiva during mouth breathing.18 The

various factors such as enlarged glandular

tissue, asthma and allergies can lead to

mouth breathing habit.19

It was estimated that there is an inverse

relation between the incidence of gingivitis

and oral hygiene practice frequency. Jessri

and coworkers showed children who

brushed their teeth once a week had almost 4

times the likelihood of experiencing dental

caries and gingivitis compared to those who

brushed their teeth 2 times a day.1

More than half of examined children (55.2%)

in our study did not use any material to clean

their teeth and they had the most prevalence of

gingival bleeding index. This result has been

stated by a number of researchers.20,21 With

regard to this fact that the poor oral hygiene is

the most important factor in prevalence of

gingivitis13 and the significant relation between

tooth brush frequency and gingivitis, it is

recommended to train children about

importance and proper use of toothbrush. The

most important association with gingivitis was

dental plaque. Numerous studies indicated that

gingival disease may be passed from parents to

children.22 Based on these findings, the

American Academy of Periodontology (AAP)

recommends that treatment of gingival disease

may involve entire families and that if one

family member has periodontal disease, all

family members should visit a dentist for

periodontal disease screening.23

This study had some limitations. For

example, factors like family income and level of

parents education that have direct effect on

childs oral health practice were not assessed in

Jahanimoghadam and Shamsaddin

this study. High prevalence of gingivitis in this

study necessitates the implementation of

immediate therapeutic and preventive policies.

This study suggests that parents in Rayen

should receive information about importance

of gingivitis and its causes. The researchers

designed a pamphlet containing information

about oral health practice in children which

was given to parents. Dental health programs

and dental camps at school level are necessary

in this region and they should be performed at

regular intervals, because children in this area

do not have accessed to standard dental care.

Asking health educators to have a more active

role in childrens oral health education and also

educating parents about their childrens oral

health could be a first step towards oral health

promotion. Parents and caregivers should be

educated on the need for effective plaque

control to prevent this condition. Furthermore,

we suggest evaluating the etiology of mouth

breathing among pre-school children and

curing it as soon as possible.

Conclusion

According to this study, the prevalence of

gingivitis among 6-year-old children in Rayen

is higher in boys.

The highest prevalence of gingivitis was seen

among children who did not use toothbrush.

With increasing toothbrush frequency, gingival

bleeding index was decreased.

Gingivitis is more common in children with

mouth breathing.

Conflict of Interests

Authors have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all children

and their parents, as well as authorities of

schools who participated in this study.

References

1. Jessri M, Jessri M, Rashidkhani B, Kimiagar SM. Oral health behaviours in relation to caries and gingivitis in primaryschool children in Tehran, 2008. East Mediterr Health J 2013; 19(6): 527-34.

2. McDonald RE, Avery DR, Dean JA. Dentistry for the child and adolescent. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2004.

132

J Oral Health Oral Epidemiol / Summer 2016; Vol. 5, No. 3

http://johoe.kmu.ac.ir,

5 June

The prevalence and risk factors of gingivitis

Jahanimoghadam and Shamsaddin

3. Hiremath V, Mishra N, Patil AG, Sheetal A, Kumar S. Prevalence of gingivitis among children living in Bhopal. J Oral

Health Comm Dent 2012; 6(3): 118-20.

4. Genco RJ. Current view of risk factors for periodontal diseases. J Periodontol 1996; 67(10 Suppl): 1041-9.

5. Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet 2005; 366(9499): 1809-20.

6. Peretz B, Machtei EE, Bimstein E. Changes in periodontal status of children and young adolescents: a one year

longitudinal study. J Clin Pediatr Dent 1993; 18(1): 3-6.

7. Ketabi M, Tazhibi M, Mohebrasool S. The Prevalance and Risk Factors of Gingivitis Among the Children Referred to

Isfahan Islamic Azad University (Khorasgan Branch) Dental School, In Iran. Dent Res J 2006; 3(1): 1-4.

8. Jalaleddin H, Ramezani GH. Prevalence of gingivitis among school attendees in Qazvin, Iran. East Afr J Public Health

2009; 6(2): 171-4.

9. Poulsen S. Epidemiology and indices of gingival and periodontal disease. Pediatric Dentistry 1981; 3(Special Issue): 82-8.

10. Hemadneh S, Ayesh D. Prevalence of gingivitis in 6-7 years old Jordanian children. Pak Oral Dental J 2011; 31(1): 166-8.

11. Addy M, Griffiths G, Dummer P, Kingdom A, Shaw WC. The distribution of plaque and gingivitis and the influence of

toothbrushing hand in a group of South Wales 11-12 year-old children. J Clin Periodontol 1987; 14(10): 564-72.

12. Wei SH, Lang KP. Periodontal epidemiological indices for children and adolescents: I. Gingival and periodontal health

assessments. Pediatr Dent 1981; 3(4): 353-60.

13. Rezaeian S, Ahmadzadeh J, Esmailnasab N, Veisani Y, Shayan M, Moradi N. Assessment of health and nutritional

status in children based on school screening programs. Health Scope 2014; 3(1): e14462-e14466.

14. Pourhashemi SJ, Ghandehari Motlagh M, Jahed Khaniki GR. Prevalence and intensity of gingivitis among 6-10 years

old elementary school children in Tehran, Iran. J Med Sci 2007; 7(5): 830-4.

15. Taani DS. Oral health in Jordan. Int Dent J 2004; 54(6 Suppl 1): 395-400.

16. Wagaiyu EG, Ashley FP. Mouthbreathing, lip seal and upper lip coverage and their relationship with gingival

inflammation in 11-14 year-old schoolchildren. J Clin Periodontol 1991; 18(9): 698-702.

17. Jacobson L. Mouthbreathing and gingivitis. 1. Gingival conditions in children with epipharyngeal adenoids. J

Periodontal Res 1973; 8(5): 269-77.

18. Stensson M, Wendt LK, Koch G, Oldaeus G, Ramberg P, Birkhed D. Oral health in young adults with long-term,

controlled asthma. Acta Odontol Scand 2011; 69(3): 158-64.

19. Stokes N, Della Mattia D. A student research review of the mouthbreathing habit: discussing measurement methods,

manifestations and treatment of the mouthbreathing habit. Probe 1996; 30(6): 212-4.

20. d'Almeida HB, Kagami N, Maki Y, Takaesu Y. Self-reported oral hygiene habits, health knowledge, and sources of

oral health information in a group of Japanese junior high school students. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll 1997; 38(2): 123-31.

21. Chiapinotto FA, Vargas-Ferreira F, Demarco FF, Correa FO, Masotti AS. Risk factors for gingivitis in a group of

Brazilian school children. J Public Health Dent 2013; 73(1): 9-17.

22. Asikainen S, Chen C, Slots J. Likelihood of transmitting Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas

gingivalis in families with periodontitis. Oral Microbiol Immunol 1996; 11(6): 387-94.

23. Geerts SO, Legrand V, Charpentier J, Albert A, Rompen EH. Further evidence of the association between periodontal

conditions and coronary artery disease. J Periodontol 2004; 75(9): 1274-80.

J Oral Health Oral Epidemiol/ Summer 2016; Vol. 5, No. 3

http://johoe.kmu.ac.ir,

5 June

133

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- 234 585 1 PBDokumen7 halaman234 585 1 PBlisa chanBelum ada peringkat

- Hachiko StuteDokumen6 halamanHachiko Stutelisa chanBelum ada peringkat

- Analysis of General and Oral Quality of Life and Satisfaction With Treatment Among Anticoagulated PatientsDokumen4 halamanAnalysis of General and Oral Quality of Life and Satisfaction With Treatment Among Anticoagulated Patientslisa chanBelum ada peringkat

- Rashid IchsanDokumen4 halamanRashid Ichsanlisa chanBelum ada peringkat

- Hachiko StuteDokumen6 halamanHachiko Stutelisa chanBelum ada peringkat

- Bleaching ReviewDokumen14 halamanBleaching ReviewAbhisek DasBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 11 The Dental Surveyor and Its UsesDokumen4 halamanChapter 11 The Dental Surveyor and Its UsesSantosh AgarwalBelum ada peringkat

- 2 4 15-20Dokumen6 halaman2 4 15-20lisa chanBelum ada peringkat

- Reling Rebasing 1Dokumen45 halamanReling Rebasing 1lisa chanBelum ada peringkat

- Hachiko StuteDokumen6 halamanHachiko Stutelisa chanBelum ada peringkat

- Prosthodontic DiagnosisDokumen15 halamanProsthodontic DiagnosisYashpreetsingh Bhatia100% (1)

- Ikgd Blokv: Jadwal Perkuliahan TutorialDokumen1 halamanIkgd Blokv: Jadwal Perkuliahan Tutoriallisa chanBelum ada peringkat

- Hachiko StuteDokumen6 halamanHachiko Stutelisa chanBelum ada peringkat

- Hachiko StuteDokumen6 halamanHachiko Stutelisa chanBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal PH PDFDokumen15 halamanJurnal PH PDFason10Belum ada peringkat

- Jadwal Kuliah-Lembar 3Dokumen1 halamanJadwal Kuliah-Lembar 3lisa chanBelum ada peringkat

- Hachiko StuteDokumen5 halamanHachiko Stutelisa chanBelum ada peringkat

- Tugas Bahasa Inggris Nama: Lidya Kelas: XDDokumen6 halamanTugas Bahasa Inggris Nama: Lidya Kelas: XDlisa chanBelum ada peringkat

- Dentinogenesis: Dr. Asmat Jameel Assistant Professor B.D.S, F.C.P.S Head Department of Oral BiologyDokumen17 halamanDentinogenesis: Dr. Asmat Jameel Assistant Professor B.D.S, F.C.P.S Head Department of Oral Biologylisa chanBelum ada peringkat

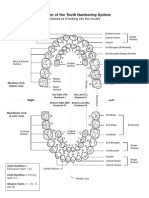

- Diagram of The Tooth Numbering SystemDokumen1 halamanDiagram of The Tooth Numbering Systemsaleh900Belum ada peringkat

- Hachiko StuteDokumen6 halamanHachiko Stutelisa chanBelum ada peringkat

- Excel (Laporan Praktikum 4)Dokumen16 halamanExcel (Laporan Praktikum 4)lisa chanBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Eb4069135 F enDokumen13 halamanEb4069135 F enkalvino314Belum ada peringkat

- Chefs at HomeDokumen4 halamanChefs at Homezbdv2kyzv7Belum ada peringkat

- Ben Wilkins PRISON MADNESS and LOVE LETTERS: THE LOST ARTDokumen5 halamanBen Wilkins PRISON MADNESS and LOVE LETTERS: THE LOST ARTBarbara BergmannBelum ada peringkat

- SPECIFIC GRAVITY - DENSITY OF HYDRAULIC CEMENT (IS - 4031-Part 11-1988)Dokumen6 halamanSPECIFIC GRAVITY - DENSITY OF HYDRAULIC CEMENT (IS - 4031-Part 11-1988)Pritha DasBelum ada peringkat

- AWWA M28 Rehabilitation of Water Mains 3rd Ed 2014Dokumen133 halamanAWWA M28 Rehabilitation of Water Mains 3rd Ed 2014millini67% (3)

- Etabloc Technical DataDokumen108 halamanEtabloc Technical Dataedward ksbBelum ada peringkat

- Anhydrous Ammonia Unloading Station & Storage/Vaporizer SystemDokumen2 halamanAnhydrous Ammonia Unloading Station & Storage/Vaporizer SystemWalter Rigamonti100% (1)

- Evolis User ManualDokumen28 halamanEvolis User ManualIonmadalin1000Belum ada peringkat

- Fossil Fuel and The Environment PPT Project FinalDokumen14 halamanFossil Fuel and The Environment PPT Project Finalapi-298052133Belum ada peringkat

- Sharp LC 50le440u ProspectoDokumen2 halamanSharp LC 50le440u ProspectovwcxlBelum ada peringkat

- 2021 Vallourec Universal Registration DocumentDokumen368 halaman2021 Vallourec Universal Registration DocumentRolando Jara YoungBelum ada peringkat

- Verbal ReasoningDokumen8 halamanVerbal ReasoningyasirBelum ada peringkat

- BR A Consumables Catalog ElecDokumen31 halamanBR A Consumables Catalog Elecdweil1552Belum ada peringkat

- Final Project Proposal Digital Stopwatch-1Dokumen6 halamanFinal Project Proposal Digital Stopwatch-1Shahid AbbasBelum ada peringkat

- LP Pressure TestingDokumen34 halamanLP Pressure TestinglisaBelum ada peringkat

- 2206 - Stamina Monograph - 0 PDFDokumen3 halaman2206 - Stamina Monograph - 0 PDFMhuez Iz Brave'sBelum ada peringkat

- Caterpillar 360 KWDokumen6 halamanCaterpillar 360 KWAde WawanBelum ada peringkat

- Development of The FaceDokumen76 halamanDevelopment of The Facedr parveen bathla100% (1)

- Moisture ManagementDokumen5 halamanMoisture ManagementSombis2011Belum ada peringkat

- Traxonecue Catalogue 2011 Revise 2 Low Res Eng (4!5!2011)Dokumen62 halamanTraxonecue Catalogue 2011 Revise 2 Low Res Eng (4!5!2011)Wilson ChimBelum ada peringkat

- Unit-2 Final KshitijDokumen108 halamanUnit-2 Final KshitijShubham JainBelum ada peringkat

- Railway Electrification Projects Budget 2019-20Dokumen9 halamanRailway Electrification Projects Budget 2019-20Muhammad Meraj AlamBelum ada peringkat

- October 14, 2011 Strathmore TimesDokumen28 halamanOctober 14, 2011 Strathmore TimesStrathmore TimesBelum ada peringkat

- WPS Ernicu 7 R1 3 6 PDFDokumen4 halamanWPS Ernicu 7 R1 3 6 PDFandresBelum ada peringkat

- Hypnotherapy GuideDokumen48 halamanHypnotherapy Guides_e_bell100% (2)

- RESISTANCEDokumen9 halamanRESISTANCERohit SahuBelum ada peringkat

- Vedic Astrology OverviewDokumen1 halamanVedic Astrology Overviewhuman999100% (8)

- Management of Septic Shock in An Intermediate Care UnitDokumen20 halamanManagement of Septic Shock in An Intermediate Care UnitJHBelum ada peringkat

- Radiesse Pálpebras Gox-8-E2633Dokumen7 halamanRadiesse Pálpebras Gox-8-E2633Camila CrosaraBelum ada peringkat

- 43-101 Technical Report Quimsacocha, February 2009Dokumen187 halaman43-101 Technical Report Quimsacocha, February 2009Marco Vinicio SotoBelum ada peringkat