Need To Reduce The Number of Antibiotic Prescriptions

Diunggah oleh

BlessyJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Need To Reduce The Number of Antibiotic Prescriptions

Diunggah oleh

BlessyHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Oral Care repOrt

Need to Reduce the Number

of Antibiotic Prescriptions

T

he development of antibiotics marked

a dramatic advance in the management of

infectious diseases, and one of the most

important advances in modern medicine.

Antibiotics greatly reduced the morbidity and

mortality rates associated with bacterial infections. Nevertheless, over the past 75 years,

the extensive use of antibiotics has resulted

in the emergence of microorganisms that

are resistant to most, if not all, of the major

antibiotics. Further, the development of secondary infections, which represents the overgrowth of other pathogenic microorganisms,

can be life threatening.1

This situation is due in large part to overprescribing of antibiotics in clinical practice

as well as other uses of antibiotics, including

increasing the growth of livestock. A recent

report from the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention indicates that one third of

the antibiotic prescriptions written by medical providers in outpatient settings were

unnecessary.2 While antibiotic usage by physicians is declining, a disturbing trend is an

apparent increase in antibiotic prescriptions

by dentists.3,4 This practice must be evaluated and corrective action taken. Dentists must

have current knowledge on the appropriate

use of antibiotics.5,6

Antibiotic Prescribing by

Dentists

In the United States, antibiotic prescribing in dentistry represents around 10%

of the total prescribed annually,7 10% of

the total in Spain, and 9% of the total in

Scotland.8,9 In the Czech Republic, dentists

were responsible for 8.5% of all antibiotics

prescribed in 2012 compared with 6.5% in

2006.4 Further, in British Columbia the proportion written by dentists represented

11.3% of the total in 2013 versus 6.7% in

1996; a 62.2% increase.3 In contrast, physicians prescriptions in the same period

decreased by 18.2%.3

Of further concern, more broad-spectrum antibiotics are being prescribed by dentistspredominantly the amoxicillin group

and fewer narrow-spectrum drugs (e.g., penicillin V).10-15 Broad-spectrum antibiotics are

well recognized for an increased risk of antimicrobial resistance.5 In a 2009 survey in the

United States (n = 845), amoxicillin was the

first choice for 37.6% of responding dentists

in 2009 (in the absence of an allergy), up from

27.5% in 1999. In the same period, penicillin

was the first choice for 43.3% in 2009, down

from 61.5% in 1999.10 In the Czech Republic,

amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (Augmentin)

accounted for 31.4% of antibiotics prescribed

by dentists in 2012 compared with 23.1% in

2006, and 19% of all antibiotics used in primary care.4 Similar trends are observed in

other countries3,11-16 (see table on next page).

In addition to the increased use of amoxicillin, the number of unnecessary prescriptions written by dentists for clindamycin and

cephalosporins is of concern, given their association with Clostridium difficile-associated disease (i.e., pseudomembranous colitis).1

Inappropriate Prescribing

Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing by

dentists has been reported for dry sockets,

third molar extractions, localized swelling,

and periodontal and endodontic treatment.3,5,17

In one retrospective chart review, 70% of antibiotic prescriptions were inappropriate, the

majority given for acute pulpitis.5 Antibiotics

are not required for most properly managed

endodontic infections.18 Routine use of antibiotics is not required for apical periodontitis

(AP), chronic/acute apical abscesses (CAA/

AAA),18 and clearly not indicated for irreversible pulpitis (IP). Antibiotics should be

prescribed when there is diffuse facial swelling

or systemic involvement (fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy),10,18 and when indicated by a

patients medical status.18

Click here to continue to next page

In This Issue

Need to Reduce the Number of

Antibiotic Prescriptions

CLINICAL PRACTICE - Diagnosis of

Acute Endodontic Lesions

TECHNOLOGY - Fixed Orthodontic

Appliances or Clear

Aligner Treatment

5

DENTISTRY AND HEALTH CARE Obesity and Periodontitis

PREVENTIVE DENTISTRY Dental Management of

Patients with Autism

HEALTHCARE TRENDS Methamphetamine Abuse and the

Role for the Dental Profession

11

Educational Objectives

After reading this issue of the Colgate

Oral Care Report and correctly answering the questions in the Continuing

Education Quiz, you will

1. understand the problems associated

with antibiotic over-prescribing and

see the necessity for practicing good

antibiotic stewardship;

2. learn the latest techniques designed

to assist dental professionals in

determining the diagnosis of pain of

endodontic origin;

3. become familiar with the relative

benefits of clear retainer-like appliances vs. brackets and arch wires

for certain orthodontic treatments;

4. know the latest evidence supporting

obesity as a risk factor for periodontal disease; and

5. recognize the challenges associated

with treating autistic patients and

the suggested means to provide

effective care.

Volume 26, Number 3, 2016

Providing Continuing Education as a Service to Dentistry Worldwide

Oral Care repOrt

2

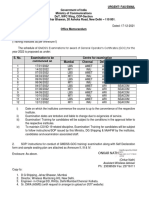

Antibiotic Prescribing by Dentists4,10-15

2004

Belgium

75.1% of prescriptions were amoxicillin or amoxicillin with

clavulanic acid

2009

Spain

1st choice amoxicillin for 44.3%, amoxicillin with clavulanic

acid for 41.8%

2009

USA

1st choice penicillin VK for 43.3%, amoxicillin for 41.2%

2010

Spain

1st choice amoxicillion with clavulanic acid for 61%,

amoxicillin for 34%

2012

Czech Rep.

31.4% prescribed amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (Augmentin)

2013

Jordan

62.9% most often prescribed amoxicillin, 33.4% amoxicillin

combinations (with clavulanic acid and/or metronidazole)

2013

Turkey

61.8% often prescribed amoxicillin with clavulanic acid,

46.5% amoxicillin

2015

Saudi Arabia

45.2% prescribed amoxicillin with clavulanic acid,

33.7% amoxicillin and 15% amoxicillin with metronidazole

In one retrospective chart review,

70% of antibiotic prescriptions

were inappropriate, the majority

given for acute pulpitis.

Nonetheless, prescribing antibiotics for

endodontic conditions is a widespread practice. Inappropriate prescribing is reported

for IP, acute apical periodontitis (AAP), chronic apical periodontitis, AAA, and other conditions.3-5,8,10,11-15 Antibiotic prescribing for AAP

(with no swelling) was reported by 28.3%,

59%, and 71% of clinicians in surveys from

the United States, Saudi Arabia, and Spain,

respectively10,12,15 (see figure).

Percentage of clinicians prescribing

antibiotics for AAP (no swelling)

28%

59%

71%

n United States n Saudi Arabia n Spain

Antibiotics are also prescribed to manage endodontic flare-ups10 and to relieve pain

between treatments,10 yet there is no evidence

to support this practice.3 Furthermore, they

are given in lieu of proper treatment;5,10,14 an

antibiotic prescription without any definitive

treatment was provided to 54% of patients

receiving care in an after-hours dental clinic.19 In other research, differences in the pat-

tern of antibiotic use have resulted in significant differences in the level of antibiotic resistance, with one study finding increased antimicrobial resistance for periodontal pathogens.20

The most important initial

decision is not which antibiotic to

prescribe, but whether to use one

at all.

Other Factors

Additional reasons given for inappropriate prescribing include the need to delay definitive treatment, an uncertain diagnosis, the need

to avoid problems if the patient/clinician will

be on vacation, and lack of resources to pay

for care (no dental insurance).10,11,21 Excessive

antibiotic prescribing may also be associated

with the increase in implant treatment and associated complications, and with routine extraction of third molars.3

Patient expectations are a driver.10,11,21 In separate patient and dentist surveys in the UK, 23%

of patients (n = 156) expected an antibiotic and

8% of dentists reported being influenced by such

expectations.21 In the United States, 19% of clinicians gave antibiotics if patients asked for them,

or out of fear of losing referrals if requested by

the referring dentist.10

Patient expectations are a driver

for over-prescribing of antibiotics

by dentists.

Lack of awareness and knowledge of current guidelines and an unwillingness to change

are additional factors in antibiotic over-prescribing by dental professionals. Furthermore,

differences between past and current guidelines (e.g., regarding antibiotic prophylaxis,

lack of clarity, and minor differences between

sets of guidelines) may result in confusion.18,21

As an example, revised guidelines were provided by the American Dental Association on

antibiotic prophylaxis for patients with prosthetic joints and for prophylaxis against infective endocarditis.22 In contrast to prior recommendations, there are now relatively few

patient subpopulations for whom antibiotic

prophylaxis may be indicated prior to certain

dental procedures.22

Current Guidelines and

Antibiotic Stewardship

Antimicrobial stewardship programs are

intended to optimize the use of antimicrobials through appropriate use, dosing, duration, and selection.23 Guidelines include (1)

prescribing the shortest effective dose; (2)

only prescribing when necessary and providing a delayed prescription that a patient can

fill later if needed; (3) discussing alternatives

with patients and educating them about antibiotic use and risks; (4) avoiding repeat prescriptions whenever possible; and (5) auditing healthcare facilities for antibiotic prescribing patterns.24

Improving Antibiotic

Stewardship

A concerted effort is required to improve

antibiotic prescribing. In a review of interventions with providers, there was moderate evidence supporting communication skill training.23 The evidence for effectiveness of provider

or patient education, guidelines, delayed prescribing, and computer-aided decision making was weak. However, the relative efficacy of

individual interventions was not provided in

most studies where several were used.23 In a

separate review, the most effective outcome

was achieved using a combination of interventions involving providers, patients, and the public.25 Interactive educational meetings were

found to be more effective than didactic ones,

and patient education was also effective. Printed

educational materials or audit/feedback alone

were of limited value.24

Intensive training has proven effective

in changing prescribing behaviors, at least in

Click here to continue to next page

Oral Care repOrt

the short term. In one prospective two-cycle

audit of 60 patients, clinicians and students

received intensive training between the audits,

which were held two months apart. Significant

improvements in prescribing were observed,

with 80% of antibiotic prescriptions meeting

the guidelines versus 30% at the first audit.5

Research-based audit and feedback mechanisms are now being investigated in a clustered, randomized, stratified trial. The control group is the audit group, while each dentist in the intervention group received

individualized feedback regarding his/her

antibiotic prescribing rate for the prior 14

months. Some dentists also received feedback

at 9 months, text-based interventions, and a comparator. This trial will provide further information on interventions and their efficacy.9

Computer-aided clinical decision making also shows promise as a guide for improved

antibiotic prescribing.26 In five of seven randomized or cluster randomized trials, a statistically significant improvement in antibiotic prescribing was observed using this tool;

greater improvements were observed when

computer-aided clinical decision making was

used. More research is required to determine

which aspects of computer-aided clinical decision making would best drive appropriate

antibiotic prescribing.26

3

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

Conclusions

Over-prescribing of antibiotics by dentists is observed globally, including both the

clinical scenario and selection of an inappropriate drug or dose. Recent studies are helping to determine required changes and which

interventions will be most effective. In order

to combat antimicrobial resistance, it is essential that dental professionals understand and

adhere to the guidelines for antibiotic use and

practice good antibiotic stewardship. O

C

10.

References

12.

1.

2.

Beacher N, Sweeney MP, Bagg J. Dentists,

antibiotics and Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Br Dent J 2015;219:275-9.

Fleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ,

Bartoces M, Enns EA, File TM, Jr., Finkelstein

JA, Gerber JS, Hyun DY, Linder JA, Lynfield

R, Margolis DJ, May LS, Merenstein D, Metlay

JP, Newland JG, Piccirillo JF, Roberts RM,

Sanchez GV, Suda KJ, Thomas A, Woo TM,

Zetts RM, Hicks LA. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among US

ambulatory care visits, 2010-2011. J Am Med

Assoc 2016;315:1864-73.

11.

13.

14.

15.

Marra F, George D, Chong M, Sutherland S,

Patrick DM. Antibiotic prescribing by dentists has increased: Why? J Am Dent Assoc

2016;147:320-7.

Pipalova R, Vlcek J, Slezak R. The trends in

antibiotic use by general dental practitioners in the Czech Republic (2006-2012). Int

Dent J 2014;64:138-43.

Chopra R, Merali R, Paolinelis G, Kwok J. An

audit of antimicrobial prescribing in an acute

dental care department. Prim Dent J 2014;

3:24-9.

Johnson TM, Hawkes J. Awareness of antibiotic prescribing and resistance in primary dental care. Prim Dent J 2014;3:44-7.

Cherry WR, Lee JY, Shugars DA, White Jr. RP,

Vann Jr. WF. Antibiotic use for treating dental infections in children: a survey of dentists

prescribing practices. J Am Dent Assoc

2012;143:31-8.

Robles Raya P, de Frutos Echaniz E, Moreno

Milln N, Mas Casals A, Snchez Callejas A,

Morat Agust ML. Im going to the dentist:

antibiotic as a prevention or as a treatment?

Aten Primaria 2013;45:216-21.

Prior M, Elouafkaoui P, Elders A, Young L,

Duncan EM, Newlands R, et al. Evaluating

an audit and feedback intervention for reducing antibiotic prescribing behaviour in general dental practice (the RAPiD trial): a partial factorial cluster randomised trial protocol. Implement Sci 2014;9:50.

Pye K. Antibiotic Use by Members of the

American Association of Endodontics: A

National Survey for 2009. A follow up from

the report in 1999. Available at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu.

Dar-Odeh NS, Al-Abdalla M, Al-Shayyab MH,

Obeidat H, Obeidat L, Abu Kar M, AbuHammad OA. Prescribing antibiotics for pediatric dental patients in Jordan; knowledge

and attitudes of dentists. Int Arabic J Antimicrob

Agents 2013;3(4):1-6.

Iqbal A. The attitudes of dentists towards the

prescription of antibiotics during endodontic treatment in North of Saudi Arabia. J Clin

Diagn Res 2015;9:ZC82-4.

Mainjot A, DHoore W, Vanheusden A, Van

Nieuwenhuysen JP. Antibiotic prescribing in

dental practice in Belgium. Int Endod J

2009;42(12):1112-7.

Kaptan RF, Haznedaroglu F, Basturk FB,

Kayahan MB. Treatment approaches and

antibiotic use for emergency dental treatment

in Turkey. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2013;9:

443-9.

Segura-Egea JJ, Velasco-Ortega E, Torres-

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

Lagares D, Velasco-Ponferrada MC, MonsalveGuil L, Llamas-Carreras JM. Pattern of antibiotic prescription in the management of

endodontic infections amongst Spanish oral

surgeons. Int Endod J 2010;43(4):342-50.

Rodriguez-Nez A, Cisneros-Cabello R,

Velasco-Ortega E, Llamas-Carreras JM, TrresLagares D, Segura-Egea JJ. Antibiotic use by

members of the Spanish Endodontic Society.

J Endod 2009;35(9):1198-203.

Jaunay T, Sambrook P, Goss A. Antibiotic prescribing practices by South Australian general dental practitioners. Aust Dent J

2000;45:(3):179-86.

American Association of Endodontists.

Endodontics: Colleagues for excellence. Use

and abuse of antibiotics. Winter 2012.

Tulip DE, Palmer NO. A retrospective investigation of the clinical management of patients

attending an out of hours dental clinic in

Merseyside under the new NHS dental contract. Br Dent J 2008;205(12):659-64.

Ardila CM, Granada MI, Guzmn IC.

Antibiotic resistance of subgingival species

in chronic periodontitis patients. J Periodontal

Res 2010;45(4):557-63.

Cope AL, Chestnutt IG. Inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics in primary dental care:

reasons and resolutions. Prim Dent J

2014;3(4):33-7.

American Dental Association. Antibiotic

prophylaxis prior to dental procedures.

Available at: http://www.ada.org/en/member-center/oral-health-topics/antibiotic-prophylaxis.

Drekonja DM, Filice GA, Greer N, Olson A,

MacDonald R, Rutks I, Wilt TJ. Antimicrobial

stewardship in outpatient settings: a systematic review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol

2015;36:142-52.

National Center for Biotechnology

Information, U.S. National Library of

Medicine. Guidelines set to tackle over-prescribing of antibiotics. 2015. Available from:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/behindtheheadlines/news/2015-0818-guidelines-set-to-tackle-over-prescribing-ofantibiotics/.

Arnold SR, Straus SE. Interventions to

improve antibiotic prescribing practices in

ambulatory care. Evid Based Child Health

2006;623-690.

Holstiege J, Mathes T, Pieper D. Effects of

computer-aided clinical decision support systems in improving antibiotic prescribing by

primary care providers: a systematic review.

J Am Informatics Assoc 2015;22:236-42.

Oral Care repOrt

CLINICAL PRACTICE

Diagnosis of Acute Endodontic Lesions

One of the most challenging aspects of

clinical dentistry is the accurate diagnosis of

acute pain, often due to endodontic involvement. Typically, the diagnosis of pain of

endodontic origin relies on clinical symptoms,

some simple physical tests, and radiographic

findings. These alone may not; however, accurately provide a diagnosis. Acute apical abscesses (AAA) are usually obvious, however a definitive diagnosis of symptomatic apical periodontitis (SAP) and/or of symptomatic irreversible pulpitis (SIP) for a tooth can be difficult when relying on clinical symptoms, basic

physical tests, and radiography.

New approaches have also been introduced to improve the accuracy of diagnosis

of endodontic lesions. These include ultrasound imaging and color Doppler (USCD),1,2

as well as cone beam computed tomography

(CBCT)3. These too have their limitations,1,4

including the static nature of the information obtained. As acute, emergent situations

are often stressful for both the provider and

patient, a decision tree has been introduced

to help guide the clinician to the proper

endodontic diagnosis.5 Use of the decision

tree is a dynamic approach to diagnosis.

CBCT

CBCT provides images free of distortion

and without the possibility of superimposition that is inherent for PAs.4 In a recent study

(n = 130) comparing the diagnosed prevalence of SAP and asymptomatic AP in 307

paired roots representing 138 teeth,11 AP

lesions were observed in 3.3% and 13.7% of

roots when using PAs and CBCT, respectively (p < 0.05). A greater number of lesions was

observed for SAP vs. asymptomatic AP using

CBCT, and 22 affected roots were identified

that were not detected on PAs.11 In another

study involving 340 paired roots of 161 teeth,

15 previously unidentified affected roots were

found using CBCT.8

In comparing the accuracy of CBCT and

PAs in detecting root anatomy and anomalies

in 250 roots, as referenced to the benchmark

(transverse sections of teeth; TS), significantly more root canals were identified with CBCT

(294 of 295 vs. 230 of 295 with PAs; see Figure

1).4 Additionally, CBCT detected 10 of 16 accessory canals (with no false positives) and 4 of

5 transverse fractures.4 The quality of CBCT

is, however, impacted by metallic restorations,

pins, and root fillings.4

Radiographs

Peri-apical radiographs (PAs) are standard practice when assessing acute dental pain,

and treatment is often based on the observed

findings. Digital radiography permits rapid

acquisition and manipulation of images,

including magnification and digital subtraction applications.6 However, since PAs are twodimensional, not all details are visible. PAs

may not detect early periapical changes associated with SAP, appearing normal or only

showing a thickening of the periodontal ligament.7 In one study, PAs detected periapical radiolucencies in just 15% of roots in teeth

with SAP.8 In addition, PAs usually detect periapical lesions only after the cortical plate has

been perforated.9

PAs may not detect early

periapical changes associated

with SAP, appearing normal or

only showing a thickening of the

periodontal ligament.

USCD

Ultrasound technology allows threedimensional (3D) visualization of structures

deep within the tissues.2 The diagnostic capabilities of ultrasound are enhanced by color

Doppler technology, which detects and measures blood flow in the tissues.10 Studies have

compared the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of USCD and PAs in the differential diagnosis of periapical granulomatous, cystic, and

mixed lesions, and to track post-surgical healing. Results from these studies have been

promising, with one (n = 30) finding 100%

concurrence in a diagnosis of anterior granulomatous lesions (n = 16) with USCD and

the histology gold standard.2

Nonetheless, there is currently a paucity

of USCD data for SAP. In addition, in comparing USCD with PAs and histology samples

from periapical lesions in anterior, bicuspid,

and molar teeth (n = 30),1 USCD was found

to be accurate only when the mean bone thickness was < 1.6 mm (p = 0.03).1 This limits the

potential use of this technique to areas where

cortical bone is thinner, such as the anterior

maxilla.

230

294

295

n PAs n CBCT n Transverse Sections

Figure 1. Number of root canals identified by different

diagnostic techniques.4

Diagnosis Using a

Decision Tree

In a recent study involving patients with

a chief complaint of acute severe dental pain

(n = 221), a decision tree was developed as

an aid to diagnosis.5 The study included 103

patients diagnosed with SAP and 70 diagnosed

with SIP. During development of the decision

tree, the clinical signs and findings and a

checklist with 11 questions on symptoms were

used to identify differentiators for SIP and

SAP. A numeric assessment of the level of pain

in the prior 24 hours (with 0 being no pain

and 10 being the worst pain imaginable) was

included.5

Clinical findings used to differentiate SIP

and SAP included sensitivity to cold using carbon dioxide ice, and the identification of a

widened periodontal ligament on PAs.

However, since PAs may or may not show a

widened periodontal ligament space with SAP,

this is not definitive, and early radiolucencies may also not be apparent.

Of teeth with a pain response to cold,

duration of pain < 1 week and that felt high,

72% were correctly determined to have SAP

(Figure 2). Non-differentiators included the

level, constancy, and reduction of pain spontaneously or upon application of cold,

response to heat, the presence of a sharp or

radiating pain, pain on chewing, and sleep

disturbance. It was determined that the deci69.9%

75.7%

n SIP

45.7%

35.9%

Pain

< 1 Week

Pain

on Cold

n SAP

48.5%

28.6%

Tooth

Felt High

Figure 2. Frequency of a positive response to differentiators

for SIP and SAP.5

sion tree had a positive predictive value of 67%,

though specificity was only 31%.5 This means

that there was a 67% chance that the individual had the condition, but also a high risk of

false negative findings.

Conclusions

The ability to differentiate endodontic

lesions is necessary for an accurate diagnosis

and subsequent treatment. Not only can AAA

develop rapidly, the emergency treatment for

SIP and SAP differ (pulpotomy vs. pulpectomy). Therefore, an accurate definitive diagnosis for SIP and SAP is clinically important.

Currently, there is a paucity of data for

USCD with respect to SIP and SAP. Data on

CBCT is promising, although now limited.

The decision tree described in this article is

an innovation in clinical care. While not a

perfect tool, it provides a logical approach

to arriving at the diagnosis of pain of

endodontic origin. O

C

References

1.

Tikku AP, Bharti R, Sharma N, Chandra A,

Kumar A, Kumar S. Role of ultrasound and

color doppler in diagnosis of periapical lesions

of endodontic origin at varying bone thickness. J Cons Dent 2016;19(2):147-51.

2. Sandhu SS, Singh S, Arora S, Sandhu AK,

Dhingra R. Comparative evaluation of

advanced and conventional diagnostic aids

for endodontic management of periapical

lesions, an in vivo study. J Clin Diagn Res

2015;9(1):ZC01-4.

3. Leonardi Dutra K, Haas L, Porporatti AL,

Flores-Mir C, Nascimento Santos

Mezzomo LA, Correa M, De Luca Canto G.

Diagnostic accuracy of cone-beam computed tomography and conventional radiography on apical periodontitis: a systematic review

and meta-analysis. J Endod 2016;42(3):

356-64.

4. Weber MT, Stratz N, Fleiner J, Schulze D,

Hannig C. Possibilities and limits of imaging

endodontic structures with CBCT. Swiss Dent J

2015;125(3):293-311.

5. Rechenberg DK, Held U, Burgstaller JM,

Bosch G, Attin T. Pain levels and typical symptoms of acute endodontic infections: a

prospective, observational study. BMC Oral

Health 2016;16(1):61.

6. Carvalho FB, Gonalves M, Tanomaro-Filho

M. Evaluation of chronic periapical lesions

by digital subtraction radiography by using

Adobe Photoshop CS: a technical report. J

Endod 2007;33:493-7.

7. Gutmann JL, Baumgartner JC, Gluskin AH,

Hartwell GR, Walton RE. Identify and define

all diagnostic terms for periapical/periradicular health and disease states. J Endod

2009;35(12):1658-74.

8. Abella F, Patel S, Durn-Sindreu F, Mercad

M, Bueno R, Roig M. An evaluation of the

periapical status of teeth with necrotic pulps

using periapical radiography and cone-beam

computed tomography. Int Endod J

2014;47(4):387-96.

9. Bender IB, Seltzer S. Roentgenographic and

direct observation of experimental lesions

in bone. J Am Dent Assoc 1961;62:708.

10. Patel S, Dawood A, Whaites E, Pitt Ford T.

New dimensions in endodontic imaging: Part

1. Conventional and alternative radiographic systems. Int Endod J 2009;42:447-62.

11. Abella F, Patel S, Duran-Sindreu F, Mercad

M, Bueno R, Roig M. Evaluating the periapical status of teeth with irreversible pulpitis

by using cone-beam computed tomography

scanning and periapical radiographs. J Endod

2012;38(12):1588-91.

Oral Care repOrt

TECHNOLOGY

Fixed Orthodontic Appliances or Clear Aligner Treatment

Clear Aligner Treatment (CAT) was

introduced commercially approximately 15

years ago, and represents an alternative to traditional orthodontic tooth movement with a

fixed orthodontic appliance (FOA).1 Utilizing

a series of clear retainer-like appliances that

move the teeth in a sequential fashion, CAT

represents a major change in orthodontic care,

with more than 3 million patients having been

treated across the globe.2 CAT involves the

application of three-dimensional digital technology to dentistry, and represents another

aspect in the evolution of clinical practice.

Many types of malocclusion have now been

treated using CAT, including, but not limited to, maxillary and mandibular incisor crowding, tooth rotations, and class I, II, and III malocclusions.1,3-7 CAT offers some distinct advantages, as well as some limitations.8

Advantages of CAT

The advantages of CAT compared to FOA

include better esthetics during treatment, the

ability to more easily perform oral hygiene

since the aligners are removable, and an

absence of plaque traps (brackets and arch

wires). The result is improved oral health during orthodontic treatment.9-12

Oral Health-Related

Quality of Life (OHRQoL)

OHRQoL is a subjective assessment by

the patient of his/her perceived well-being

related to the oral cavity.13 In a study of 100

patients receiving CAT or FOA for a mean

duration of slightly over one year,9 6% of CAT

and 36% of FOA patients perceived a decline

in well-being. Statistically significant

differences were observed for willingness to

laugh (p = 0.012), impact on eating habits

(p = 0.066), and gingival irritation (p = 0.001).

Just 2% of patients receiving CAT said they

would be unwilling to have the same treatment

again vs. 22% of patients receiving FOA

(p = 0.004; see Figure 1).9

Would have

treatment again

78%

98%

Impact on

eating habits

Gingival

irritation

70%

50%

56%

14%

Reluctant

to laugh

6%

Decline in

well-being

6%

26%

36%

n FOA

n CAT

Figure 1. Subjective assessment of factors affecting OHRQoL.9

In a systematic review of 11 studies, the

first few weeks of wearing an FOA negatively

impacted OHRQoL, which then partially

rebounded. The most significant influence

on OHRQoL was pain.13 Ultimately, OHRQoL

was higher post- than pre-treatment. In one

FOA study, 91% of patients reported pain,

some citing it as a reason for wanting to end

treatment.14

98% of patients receiving CAT

said they would be willing to have

the same treatment again versus

78% of patients receiving FOA.

In a separate study, less intense and shorter duration of pain was experienced by patients

receiving CAT (n = 38) than FOA for edgewise treatment (n = 55), or a combination of

an FOA and then CAT (n = 52). For patients

receiving CAT who complained of pain, it was

usually due to tray deformation.15

Efficacy of FOA and CAT

The objective of orthodontic treatment

is to have esthetically pleasing and functional outcomes, usually with an ideal occlusion.

FOAs are effective in correcting malocclusions, and offer high success rates.16 However,

results vary depending on the malocclusion

and its severity, treatment provided, and

patient compliance.1,5,16 Open bites17 and molar

distalization, with movement of the upper

molars posteriorly to create space,18 present

treatment challenges. Relatively minor treatment differences may also influence outcomes;

for instance, FOA arch wire, sequencing, and

twisting of arch wire within the slots in the

brackets.5,19

Studies have compared actual and predicted tooth movement to measure orthodontic outcomes for CAT and FOA. For lower

anterior crowding, in one study a mean difference of 0.01 mm was observed for actual

and predicted tooth movement with CAT. The

only observed statistically significant difference was for overbite, with a mean difference

of 0.7 mm.20 Buccal expansion along with interproximal reduction (IPR) was determined

to be effective for mandibular crowding of

< 6 mm in a chart review of CAT (n = 61),

although more severe crowding resulted in

proclined and protruded lower incisors.3

Using superimposed digital images, no

statistically significant differences were found

for the same teeth for upper and lower arches in another study comparing actual vs. predicted tooth movements (n=37).21 However,

the accuracy of movements for different teeth

varied, e.g., derotation for canines was significantly less predictable than for lower central

incisors (Figure 2).21

54.2%

54.8%

59.3%

32.2%

Rotation

upper

canines

Rotation

upper

central

incisors

Lingual

Lingual

constriction constriction

lower

lower

laterals

canines

Figure 2. Mean accuracy of actual vs. predicted tooth

movements using CAT.21

There have been a number of small heterogeneous studies that assessed the efficacy

of CAT.1 A systematic review of 11 studies from

2000 to June 2014 has been published.1 CAT

was found to be as effective as FOA for the

control of vertical buccal occlusion and anterior intrusion, and to effectively level and align

arches.1 In addition, CAT was observed to be

predictable for upper molar distalization, with

an overall accuracy of 88% when 1.5 mm

movement was planned. However, results for

buccolingual tipping varied, the accuracy for

extrusion was 30%.1 CAT was not recommended for treatment of an open bite.1

Planned derotations < 15 and rotations with

a planned staging < 1.5/aligner, were significantly more accurate than the outcome for

larger derotations.5

Results and Patient Satisfaction

Predicted and actual tooth movement

and occlusion were compared for 27 cases

for CAT using the American Board of

Orthodontics Objective Grading System

(OGS).22 It was concluded that tooth movement was not accurately predicted for CAT.

Nonetheless, the results were not dissimilar

to those found for FOA therapy. It was also

concluded that the OGS score for patients

treated with CAT would be clinically acceptable.22 Further, no matter how ideal the occlusion and alignment immediately following

treatment with FOA or CAT, settling/relapse

occurred post-retention.23,24

Auxiliary

Components/Attachments

Auxiliary components are now incorporated into CAT, with the goal of achieving better control of intended tooth movement, particularly for rotation and tipping.4 In one case,

severe lower incisor rotations were successfully corrected about 2/aligner, and the crossbite and crowding treated using attachments

with a series of 23 aligners over 12 months.4

In comparing actual vs. predicted tooth movement, an overall mean accuracy of 59% was

found in a split-mouth study (n = 30).5

Oral Care repOrt

6

The difficulty of treating extraction cases

with CAT was demonstrated in a 2006 case.25

A multicenter randomized controlled trial

compared the results of FOA (n = 80) and

CAT with attachments (n = 72) for Class I

crowding extraction cases.7 There were no

differences in the overall OGS scores for CAT

and FOA, although there were significant differences for two of the eight OGS categories

(buccolingual inclination and occlusal contacts; p = 0.002 and p = 0.000, respectively).

It was concluded that CAT and FOA were both

successful in treating Class I crowding extraction cases.7

In the future, additional and large-scale randomized clinical trials of CAT would provide

evidence supporting clinical decision making, treatment planning, and outcomes.

15.

References

1.

2.

3.

Recent Developments

Mini-screws or temporary anchorage

devices (TAD) may be used for supplemental anchorage with FOA, serving to prevent

unwanted tooth movement. For the treatment

of open bites, adjunctive use of TAD or traditional edgewise FOA treatment were both

found to be effective.17 An ideal occlusion was

obtained with both techniques. It was also

found that esthetics might be superior after

using TAD, with changes in facial morphology that resulted in lip competency.17 The

adjunctive use of TAD for CAT, together with

IPR and button attachments, is reported to

improve predictability for complex cases and

to help prevent tipping.26 TAD provided

anchorage and allowed for intended, but not

unintended, tooth movement.26

Photobiomodulation (PBM) using lightemitting diodes (LEDs) promotes bone

remodeling and can accelerate tooth movement. In a proof-of-principle case report, IPR

was performed, attachments were placed after

the patient had used the first and second aligners, and PBM was applied daily for five minutes to each arch. It was thereby possible to

change aligners every three days, and to complete treatment in six months rather than 92

weeks without any reported discomfort.27

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

Conclusions

CAT has increased the demand for orthodontic treatment, especially among adults,

by offering an esthetic solution during treatment. Other advantages include both

improved oral hygiene and OHRQoL. The

accuracy of tooth movements has, however,

been variable with CAT, depending on the

type of tooth movement and the severity of

the malocclusion. However, no one treatment

guarantees a perfect result, and settling/

relapse can occur post-retention; this may also

make minor differences in outcomes less relevant over time. Auxiliary CAT components

can provide additional control of tooth movement, and the adjunctive use of new technologies for FOA and CAT is promising.

Recently, a systematic review was conducted

examining the efficacy and outcomes of CAT.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

Rossini G, Parrini S, Castroflorio T, Deregibus

A, Debernardi CL. Efficacy of clear aligners

in controlling orthodontic tooth movement:

a systematic review. Angle Orthod

2015;85(5):881-9.

Align Technology, Inc. Invisalign. 2016.

Available from: www.aligntech.com/solutions/invisalign. Accessed 18 May 2016.

Duncan LO, Piedade L, Lekic M, Cunha RS,

Wiltshire WA. Changes in mandibular incisor position and arch form resulting from

Invisalign correction of the crowded dentition treated nonextraction. Angle Orthod

2015;86(4):577-83.

Frongia G, Castroflorio T. Correction of severe

tooth rotations using clear aligners: a case

report. Aust Orthod J 2012;28(2):245-9.

Simon M, Keilig L, Schwarze J, Jung BA,

Bourauel C. Treatment outcome and efficacy of an aligner techniqueregarding incisor torque, premolar derotation and molar

distalization. BMC Oral Health 2014;14:68.

Needham R, Waring DT, Malik OH. Invisalign

treatment of Class III malocclusion with lowerincisor extraction. J Clin Orthod 2015;49(7):

429-41.

Li W, Wang S, Zhang Y. The effectiveness of

the Invisalign appliance in extraction cases

using the ABO model grading system: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Int J

Clin Exp Med 2015;8(5):8276-82.

Turpin DL. Clinical trials needed to answer

questions about Invisalign. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 2005;127(2):157-8.

Azaripour A, Weusmann J, Mahmoodi B,

Peppas D, Gerhold-Ay A, Van Noorden CJ,

Willershausen B. Braces versus Invisalign:

gingival parameters and patients satisfaction

during treatment: a cross-sectional study. BMC

Oral Health 2015;15:69.

Hennessy J, Al-Awadhi EA. Clear aligners generations and orthodontic tooth movement.

J Orthod 2016;43(1):68-76.

Karkhanechi M, Chow D, Sipkin J, Sherman

D, Boylan RJ, Norman RG, Craig RG, Cisneros

GJ. Periodontal status of adult patients treated with fixed buccal appliances and removable aligners over one year of active orthodontic

therapy. Angle Orthod 2013;83(1):146-51.

Juliena KC, Buschang PH, Campbell PM.

Prevalence of white spot lesion formation during orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod

2013;83(4):641-7.

Zhou ZY, Wang Y, Wang XY, Volire G, Hu

RD, et al. The impact of orthodontic treatment on the quality of life. a systematic review.

BMC Oral Health 2014;14:66.

Pringle AM, Petrie A, Cunningham SJ,

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

McKnight M. Prospective randomized clinical trial to compare pain levels associated with

2 orthodontic fixed bracket systems. Am J

Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2009;136(2):160-7.

Fujiyama K, Honjo T, Suzuki M, Matsuoka S,

Deguchi T. Analysis of pain level in cases treated with Invisalign aligner: comparison with

fixed edgewise appliance therapy. Prog Orthod

2014;15:64.

Birkeland K, Furevik J, Be OE, Wisth PJ.

Evaluation of treatment and post-treatment

changes by the PAR Index. Eur J Orthod

1997;19(3):279-88.

Deguchi T, Kurosaka H, Oikawa H, Kuroda

S, Takahasi I, Yamashiro Y, Takano-Yamamoto

T. Comparison of orthodontic treatment outcomes in adults with skeletal open bite between

conventional edgewise treatment and implantanchored orthodontics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

Orthop 2011;139(4 Suppl):60-8.

Jambi S, Thiruvenkatachari B, OBrien KD,

Walsh T. Orthodontic treatment for distalising upper first molars in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2013;(10):CD008375.

Flores-Mir C. Little evidence to guide initial

arch wire choice for fixed appliance therapy. Evid Based Dent 2014;15(4):112-3.

Krieger E, Seiferth J, Marinello I, Jung BA,

Wriedt S, Jacobs C, Wehrbein H. Invisalign

treatment in the anterior region: were the

predicted tooth movements achieved? J Orofac

Orthop 2012;73(5):365-76.

Kravitz ND, Kusnoto B, BeGole E, Obrez A,

Agrane B. How well does Invisalign work? A

prospective clinical study evaluating the efficacy of tooth movement with Invisalign. Am

J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2009;135:27-35.

Buschang PH, Ross M, Shaw SG, Crosby D,

Campbell PM. Predicted and actual end-oftreatment occlusion produced with aligner

therapy. Angle Orthod 2015;85:723-7.

Bondemark L, Holmb A-K, Hansenc K,

Axelssond S, Mohline B, Brattstrom V, Pauling

G, Pietila T. Long-term stability of orthodontic treatment and patient satisfaction. A systematic review. Angle Orthod 2007;77(1):

181-91.

Nett BC, Huang GJ. Long-term posttreatment

changes measured by the American Board

of Orthodontics objective grading system.

Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2005;127(4):

444-50.

Giancotti A, Greco M, Mampieri G. Extraction

treatment using Invisalign technique. Prog

Orthod 2006;7(1):32-43.

Lin JC, Tsai SJ, Liou EJ, Bowman SJ. Treatment

of challenging malocclusions with Invisalign

and miniscrew anchorage. J Clin Orthod

2014;48(1):23-36.

Ojima K, Dan C, Kumagai Y, Schupp W.

Invisalign treatment accelerated by photobiomodulation. The Cutting Edge 2016;L5:

309-17.

Oral Care repOrt

DENTISTRY AND HEALTH CARE

Obesity and Periodontitis

The relationship between systemic disease and oral disease has focused primarily on

cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes mellitus (DM), and pregnancy outcomes. One condition that is important in the development

of chronic diseases such as CVD and DM, and

has a role in complications of pregnancy, is

obesity. Recently published studies have examined the relationship of obesity and periodontitis in the general population, patients with

DM, and on birth outcomes in pregnant

women.1-5 A systematic review has also suggested that there is a bi-directional relationship

between obesity and tooth loss,6 a conclusion

based primarily on cross-sectional studies.

Worldwide, an estimated 38% of female

adults and 36.9% of male adults were overweight or obese in 2013.7 In total, 2.1 billion

children and adults were overweight or obese.7

In the United States, an estimated 33.9% of

women and 31.6% of men are obese.7 It is

important for oral healthcare providers

(OHCPs) to understand the health implications of obesity, and the relationship of oral

disease to excess weight gain. OHCPs may be

able to refer patients or assist them with weight

loss management programs, as caloric intake

and dietary choices are part of dental practice. This common risk factor approach can

help improve outcomes of care.8

It is important for oral healthcare

providers to understand the health

implications of obesity, and the

relationship of oral disease to

excess weight gain.

Measures of Obesity

Body mass index (BMI, which is calculated as weight divided by square of the height)

is used most frequently to measure obesity;9,10

other measures used include waist circumference (WC) and waist hip ratio (WHP; see

table).9

Neck circumference (NC) is now being

considered an alternative measure for obesity.11 In the Framingham Heart Study (n =

3,307), a mean BMI of 27.8 kg/m2 was equivalent to a mean NC of 34.2 cm for females

and 40.5 cm for males.12 In a second study,

Definitions Using BMI, WC, and WHP9

Female

Male

BMI: Obese

30 kg/m2

30 kg/m2

BMI: Overweight

25 kg/m2

25 kg/m2

BMI: Normal weight

18.5kg/m2

18.5kg/m2

WC: Obese

> 35 inches (88 cm)

> 40 inches (102 cm)

WHP: Obese

> 0.85

> 0.90

NC correlated more closely than WC with

metabolic parameters and hypertension; an

NC of 35 cm for females and 38 cm for

men was suggested as a clinically relevant obesity benchmark.11

Obesity and Clinical

Attachment Loss

A recent five-year prospective study (n =

582) is supportive of obesity as a risk factor

for progressive clinical attachment loss (CAL)

in females, but not in males.1 All participants

reported no history of DM, had 6 teeth and

a BMI 18.5kg/m2; CAL progression was

defined as proximal CAL 3 mm, in 4 teeth

over the five-year period. Among the subjects,

30% and 19% were overweight and obese,

respectively, and 38% experienced CAL progression.1 After adjusting for other factors (e.g.,

demographics, medical and dental history),

obesity increased the risk of CAL by 64% in

females (p=0.01). No significant increased

risk was observed for overweight females (p

= 0.34) or for overweight or obese males (p

= 0.70 and p = 0.56, respectively).1 This was

hypothesized to be the result of the inability

of BMI measurements to differentiate between

a lean body mass (muscle) and adipose tissue (see Figure 1).1

64%

21%

13%

6%

Overweight

Obese

n Females n Males

*p = 0.01

Figure 1. Increased risk of CAL based on BMI.1

An increased risk of CAL progression

has been observed in other studies. In one

prospective study (n = 3,590), statistically

significant increases in periodontitis risk of

30%, 70%, and 324% were observed, respectively, for obese males (p < 0.001), overweight

females (p < 0.01), and obese females (p <

0.05).2 A statistically significant association

was also observed for obesity and periodontitis (defined as pocket probing depths 4

mm and CAL 3 mm in 4 teeth) in a separate randomized study (n = 340).3 Subjects

defined as obese using the BMI, WC, and

high fat percentage (HFP) were 2.9, 2.1, and

1.8 times more likely, respectively, to have

periodontitis.3

In a systematic review of five studies (n =

42,198), obesity was also found to increase

the likelihood of developing periodontitis.4

Three studies used BMI to measure obesity,

and two used BMI, WC, and WHR. Compared

to normal weight subjects, overweight and

obese subjects were 1.13 and 1.33 times more

likely, respectively, to develop periodontitis.4

Compared to normal weight

subjects, overweight and obese

subjects were 1.13 and 1.33

times more likely, respectively, to

develop periodontitis.

Based on limited data, findings on a relationship between obesity and periodontal treatment outcomes are conflicting. One study

found an increased risk of poor treatment

outcomes in obese patients compared to

normal weight patients (p = 0.012).13 In contrast, conclusions from a systematic review

were that obesity does not negatively affect

Oral Care repOrt

8

the results of periodontal therapy.14 This question requires further investigation.

Obesity and Tooth Loss

Obese subjects were 1.49 times more likely to have tooth loss and 1.25 times more likely to be edentate based on a meta-analysis of

16 studies(p < 0.05).6 Conversely, subjects with

tooth loss and edentulism were 1.41 and 1.60

times more likely to be obese (p < 0.05). While

this might suggest a bi-directional relationship, these were cross-sectional studies, limiting interpretation of the data. In addition,

only 4 studies were included for tooth loss,

with criteria ranging from 1 tooth missing

to 6 teeth missing.6

Maternal Obesity and Adverse

Birth Outcome

Focusing on periodontitis and obesity/excess weight as potentially synergistic risk

factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes, one

study (n = 328) assessed the risk of pre-term

birth (PTB) in women with pre-eclampsia

(PE).5 PE accounts for up to 20% of all PTBs.15

Previous studies reported that periodontitis

may be associated with PTB and PE.16 In the

current study, PTB (< 37 weeks) was 5.56 times

more likely in women with PE if they had periodontitis (p < 0.027), and if they were also

obese/overweight that risk increased almost

three-fold (p < 0.001; see Figure 2).5

A study in the dental setting examining

risk factors for undiagnosed diabetes mellitus included the use of WC in the algorithm.17

One concern that has been raised with regard

to the application of this algorithm is the comfort OHCPs have in measuring WC. However,

a recent report suggests that NC may be a better indicator of metabolic health than WC

for severely obese individuals.11 This provides

OHCPs with a viable approach to assess weight

as a risk factor. In addition, OHCPs frequently see patients who believe they are healthy

and may have undiagnosed DM, which may

first manifest with intraoral signs and symptoms. This provides an opportunity for early

intervention.

1.

5.56*

2.08

3.

*p < 0.027

Periodontitis and

obese/overweight

**p < 0.001

Figure 2. Increased risk level for PE-associated PTB based on

maternal weight.5

4.

Implications for Dental Care

The importance of patient obesity when

providing oral healthcare services can be seen

in many ways. Obesity has been observed to

impact CAL and oral health, and may increase

the risk of PE-associated PTB. Further, obesity is associated with DM, while DM has a bidirectional relationship with periodontitis.

9.

10.

11.

12.

References

2.

Periodontitis

8.

Conclusions

Strong evidence provides support for the

importance of obesity as a risk factor for systemic disease. OHCPs are in a unique position to consider obesity as a common risk factor for oral and systemic disease, and to advise,

counsel, and/or refer patients for lifestyle modifications.8 In doing so, OHCPs have an opportunity to intervene, collaborate with medical

professionals, and to help improve oral and

general health outcomes for patients. O

C

15.94**

Obese/

overweight

7.

5.

6.

Gaio EJ, Haas AN, Rosing CK, Oppermann

RV, Albandar JM, Susin C. Effect of obesity

on periodontal attachment loss progression:

a 5-year population-based prospective study.

J Clin Periodontol 2016;43(7):557-65.

Morita I, Okamoto Y, Yoshii S, Nakagaki H,

Mizuno K, Sheiham A, Sabbah W. Five-year

incidence of periodontal disease is related

to body mass index. J Dent Res 2011;90(2):

199-202.

Khader YS, Bawadi HA, Haroun TF, Alomari

M, Tayyem RF. The association between periodontal disease and obesity among adults in

Jordan. J Clin Periodontol 2009;36(1):18-24.

Nascimento GG, Leite FR, Do LG, Peres KG,

Correa MB, Demarco FF, Peres MA. Is weight

gain associated with the incidence of periodontitis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol 2015;42(6):495-505.

Lee HJ, Ha JE, Bae KH. Synergistic effect of

maternal obesity and periodontitis on preterm

birth in women with preeclampsia: a prospective study. J Clin Periodontol 43(8):646-51.

Nascimento GG, Leite FR, Conceicao DA,

Ferrua CP, Singh A, Demarco FF. Is there a

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

relationship between obesity and tooth loss

and edentulism? A systematic review and metaanalysis. Obes Rev 2016;17(7):587-98.

The GBD 2013 Obesity Collaboration, Ng M,

Fleming T, et al. Global, regional and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in

children and adults 1980-2013: A systematic

analysis. Lancet 2014;384(9945):766-81.

Cullinan M. The role of the dentist in the management of systemic conditions. Ann R

Australas Coll Dent Surg 2012;21:85-7.

World Health Organization. Waist

Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio Report

of a WHO Expert Consultation. Geneva, 811 December, 2008. Available at:

http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/obesity/WHO_report_waistcircumference_and_waisthip_ratio/en/.

Kopelman PG. Obesity as a medical problem.

Nature 2000;404(6778):635-43.

Assyov Y, Gateva A, Tsakova A, Kamenov Z. A

comparison of the clinical usefulness of neck

circumference and waist circumference in

individuals with severe obesity. Endocr Res

2016;6:1-9.

Preis SR, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U,

DAgostino RB Sr, Levy D, Robins SJ, Meigs

JB, Vasan RS, ODonnell CJ, Fox CS. Neck

circumference as a novel measure of cardiometabolic risk: the Framingham Heart

study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95(8):

3701-10.

Suvan J, Petrie A, Moles DR, Nibali L, Patel

K, Darbar U, Donos N, Tonetti M, DAiuto

F. Body mass index as a predictive factor of

periodontal therapy outcomes. J Dent Res

2014;93(1):49-54.

Nascimento GG, Leite FR, Correa MB, Peres

MA, Demarco FF. Does periodontal treatment

have an effect on clinical and immunological parameters of periodontal disease in obese

subjects? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig 2016;20(4):639-47.

Jeyabalan A. Epidemiology of preeclampsia:

impact of obesity. Nutr Rev 2013;71(Suppl

1):S18-25.

Kumar A, Basra M, Begum N, Rani V, Prasad

S, Lamba AK, Verma M, Agarwal S, Sharma

S. Association of maternal periodontal health

with adverse pregnancy outcome. J Obstet

Gynaecol Res 2013;39(1):40-5.

Li S, Williams PL, Douglass CW. Development

of a clinical guideline to predict undiagnosed

diabetes in dental patients. J Am Dent Assoc

2011;142(1):28-37.

Oral Care repOrt

PREVENTIVE DENTISTRY

Dental Management of Patients with Autism

Autism represents a spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders. It is characterized by altered social interaction, affecting

communication and interaction with others,

and repetitive behavior.1,2 The 1994 clinical

diagnostic criteria for autism in the Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th

Edition included five subtypes of autism.1,2

However, since 2013 autism has been defined

as one disorder.1 The prevalence of autism

has been the subject of debate, and has been

reported globally to range from 0.1% to 2%.1,3

In the United States, it appears that the diagnosis is now made more often, but it is unclear

if the prevalence has actually increased or may

be at least partly attributable to more thorough assessments. More males are affected

than females, with a 4.5:1 ratio.1

Caring for Dental Patients

with Autism

Dental care for persons with autism can

be challenging due to a lack of effective communication and, for patients, the unfamiliar

setting and unfamiliar tasks and activities.2

Patients with autism may exhibit unusual and

uncooperative behavior, such as head banging, tantrums, hyperactivity, and agitation.

Signs of self-injurious behavior may be evident; these include biting, grinding, cheek

biting, head banging, and pinching. Self-injurious behavior is reported to occur in up to

70% of children with autism.4

Dental care for persons with

autism can be challenging due to

a lack of effective communication,

the unfamiliar setting, and

unfamiliar tasks and activities.

Due to altered sensory processing,

patients with autism do not interpret sensations in the same manner as patients without

autism, which may also lead to exaggerated

responses to sounds, smells, lights, or touch,

all of which can occur during treatment.5-7 In

one study, more than half of children and adolescents with autism were uncooperative with

dental care, compared with 25.4% of the unaffected group, and just 9.2% exhibited positive behavior (p < 0.0001).8 As a result of the

challenges in providing comprehensive care

to individuals with autism, there is the possibility of long-term neglect of oral health.2

Behavioral management techniques

should be emphasized when providing dental care to persons with autism.3 Prevention is

key, especially when caring for children, but

even simple preventive procedures may not

be easily accomplished. Techniques that teach

skills and improve communication help to

overcome difficulties in treating patients with

autism. Tell-show-do and positive reinforcement may be effective depending on the

patients level of impairment. Brief clear commands are required.6 Another approach,

which does not rely heavily on interpersonal

communication, has been referred to as dental stories.5

autism will see the same dental team members on each visit, as this makes the patient

more comfortable.12

Behavioral Approaches

Suggested behavioral approaches include

applied behavior analysis (ABA).9 This technique requires participation of the dental

provider, and also parents and teachers.9

Patients with autism fail to develop joint attention, and therefore may be unable to share

information and have no curiosity about their

surroundings.9 ABA involves analyzing behavior, then implementing actions that will modify this behavior. Observing, gathering information using questionnaires or interviews with

patients/parent/caregivers, and understanding what the patient achieves with a given

behavior (for example, whether it means the

patient avoids treatment) are important in

determining what is required to modify such

functional behavior.9

A pre-visit session with parents/caregivers

is recommended to determine how they can

help with home preparation prior to the

patients visit to the dental office.10 Parents/caregivers can help prepare the patient at home

by getting him/her familiar with dental instruments such as mirrors, showing pictures of the

dental office and chair, and coaching them

on activities and phrases that will be used (e.g.,

open your mouth or close your mouth).10

In this manner, it is possible to teach the behavior that will be needed for a successful dental

visit.10 Dental treatment and the patients cooperation are a team effort.9

Desensitization is a process by which

the patient is gradually introduced to the

dental setting with progressively longer visits that may start with just a few seconds and

then build up. Distracting the patient with

a video or music, or having the patient hold

on to objects, may also be helpful during

appointments.11 Ideally, the patient with

Figure 1. Picture vocabulary chart for dental visits.

Ideally, the patient with autism

will see the same dental team

members on each visit, as this

makes the patient more

comfortable.

Dental Stories

Dental stories are social stories that use

basic language and images to describe the dental operatory environment to patients with

autism and what will happen during the visit.

Dental stories are read/viewed repeatedly

before the first dental appointment. Both print

and video versions have been utilized to prepare a child with autism for a dental visit.4

Dental stories are also available as comic books,

drawings, and photographs. The choice of

medium depends on language comprehension and preference in the home (p = 0.038

and p = 0.002, respectively).13 Standard dental stories are also available that can be adapted for an individual office.11 More information on dental stories and books about visiting the dentist such as Show Me Your Smile!

A Visit to the Dentist, and Dora the Explorer can

be found on the Autism Speaks website.11

Communicating with

Pictures and Icons

Patients with autism who have difficulty

with language may communicate using pictures, photos, a tablet with images, a simple

word processor, or a formal communication

tool with simple words/images/icons.11

Examples include a picture vocabulary chart

(Figure 1) and the Neo from AlphaSmart

(Figure 2).

Oral Care repOrt

10

For some patients, behavioral issues make

treatment without additional approaches

impossible. In certain cases, protective stabilization may be considered appropriate, however this is controversial.11 Nitrous oxide may

be helpful, provided the patient can inhale

through the nose during treatment. If conscious sedation is being considered, the

patients physician should be consulted and

a physical exam performed. General anesthesia may also be a necessary option, subject to health considerations.11

Figure 2. The Neo from AlphaSmart.

Medication Use

In one study of patients with autism

(n = 187), 47% took medications associated

with their condition, most commonly antipsychotics which reduce irritability, self-injurious behavior, distress, and other disorders.

Of the patients taking medications, almost

half were taking more than one. Forty-one

percent, 20%,16%, and 11% of patients were

receiving antipsychotics, central nervous system stimulants and other drugs, anticonvulsants, and antidepressants, respectively (Figure

3).8 Some of the signs and symptoms associated with these medications include dry

mouth, difficulty swallowing, gingivitis, stomatitis, gingival enlargement, sialadenitis, and

tongue discoloration.8 Nonetheless, children

and adolescents with autism have been found

to experience no more, or less, caries than

unaffected children. In one study, 68% of

patients with autism experienced caries vs.

86% of unaffected subjects (n = 269 and 332,

respectively; p < 0.0001).8

Antidepressants

Anticonvulsants

CNS Stimulants,

Other Drugs

11%

16%

20%

Anti-Psychotics

41%

It is important that a positive

relationship is developed with the

patient and that care is managed

in coordination with parents/

caregivers.

Another real challenge is the lack of exposure to patients with autism and other developmental disorders during dental and dental hygiene school training. The necessity of

including these experiences in the curriculum was underscored by the Commission on

Dental Accreditation, which stated in 2006

that all schools considered for accreditation

must offer such didactic and clinical education to students.16

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

Conclusions

Knowledge concerning autism and an

understanding of its behavioral principles are

essential when treating these patients. Using

ABA procedures can help with the effective

management of problem behaviors when providing dental care. In addition, the involvement of parents/caregivers is an important

part of a successful approach to providing dental care to patients with autism. O

C

References

1.

Figure 2. Percentage of patients with autism using medications.8

Other Considerations

and Implications

It is essential that patients with autism

have a dental home and that they receive regular preventive care to maintain oral health.14

However, barriers to care include the childs

attitude toward dental procedures and limited resources.15 It is, therefore, important that

a positive relationship is developed with the

patient and that care is managed together with

parents/caregivers.

3.

2.

Christensen DL, Baio J, Braun KV, Bilder D,

Charles J, Constantino JN, Daniels J, Durkin

MS, Fitzgerald RT, Kurzius-Spencer M, Lee

L-C, Pettygrove S, Robinson C, Schulz E, Wells

C, Wingate MS, Zahorodny W, Yeargin-Allsopp

M. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism

Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged

8 Years Autism and Developmental

Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites,

United States, 2012. MMWR Surveill Summ

2016;65(No. SS-3)(No. SS-3):123.

Gandhi RP, Klein U. Autism spectrum disorders: an update on oral health management.

J Evid Based Dent Pract 2014;14(Suppl):

115-26.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Autism spectrum disorder. Available

at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/

data.html.

Murshid EZ. Oral health status, dental needs

habits and behavioral attitude towards dental treatment of a group of autistic children

in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent J

2005;17:132-9.

National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial

Research. Practical oral care for people with

autism. Available at: http://www.nidcr.nih.gov/

OralHealth/Topics/DevelopmentalDisabilities

/PracticalOralCarePeopleAutism_mobile.htm.

Gupta M. Oral health status and dental management considerations in autism. Int J

Contemp Dent Med Rev 2014; Article ID

011114:1-6.

Stein LI, Polido JC, Mailloux Z, Coleman GG,

Cermak SA. Oral care and sensory sensitivities in children with autism spectrum disorders. Spec Care Dentist 2011;31:102-10.

Loo CY, Graham RM, Hughes CV. The caries

experience and behavior of dental patients

with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Dent Assoc

2008;139(11):1518-24.

Hernandez P, Ikkanda Z. Applied behavior

analysis: behavior management of children

with autism spectrum disorders in dental environments. J Am Dent Assoc 2011;142(3):

281-7.

Delli K, Reichart PA, Bornstein MM, Livas C.

Management of children with autism spectrum disorder in the dental setting: Concerns,

behavioural approaches and recommendations. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal

2013;18(6):e862-8.

Autism Speaks. Treating children with autism

spectrum disorders. A tool kit for dental professionals. Available at: https://www.autismspeaks.org/docs/sciencedocs/atn/dentaltoolkit.pdf

Marshall J, Sheller B, Manci L, Williams BJ.

Parental attitudes regarding behavior guidance of dental patients with autism. Pediatr

Dent 2008;30(5):400-07.

Marion IW, Nelson TM, Sheller B, McKinney

CM, Scott JM. Dental stories for children with

autism. Spec Care Dentist 2016;36(4):181-6.

Charles JM. Dental care in children with developmental disabilities: attention deficit disorder, intellectual disabilities, and autism. J Dent

Child (Chic) 2010;77(2):84-91.

Lai B, Milano M, Roberts MW, Hooper SR.

Unmet dental needs and barriers to dental

care among children with autism spectrum

disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 2012;42:

1294-303.

Commission on Dental Accreditation 2006.

Oral Care repOrt

11

HEALTHCARE TRENDS

Methamphetamine Abuse and the

Role for the Dental Profession

A

Editor-in-Chief

Ira B. Lamster, DDS, MMSc

Professor of Health Policy &

Management,

Mailman School of Public Health

Dean Emeritus,

Columbia University College of

Dental Medicine

International Editorial Board

P. Mark Bartold, BDS, BScDent

(Hons), PhD, DDSc, FRACDS

(Perio); Australia

John J. Clarkson, BDS, PhD; Ireland

Kevin Roach, BSc, DDS, FACD;

Canada

Prof. Cassiano K. Rsing; Brazil

Mariano Sanz, DDS, MD; Spain

Ann Spolarich, RDH, PhD; USA

Xing Wang, MD, PhD; China

Rebecca S. Wilder, RDH, MS; USA

David T.W. Wong, DMD, DMSc; USA

2016 Colgate-Palmolive Company.

All rights reserved.

The Oral Care Report

(ISSN 1520-0167) is supported by

the Colgate-Palmolive Company for

oral care professionals.

Editorial Quality Control by

Teri S. Siegel.

Layout and graphic design by

Horizons Advertising and Graphic

Design, Morrisville, PA (USA).

Published by Professional Audience

Communications, Inc.,

Charlotte, NC (USA).

E-mail comments and queries to the

Editor, Oral Care Report...

ColgateOralCareReport@gmail.com

recent essay in the ADA News discussed the effects of recreational use of methamphetamine

(meth) on the oral cavity.1 This is a condition that was identified 15 years ago, seen in individuals who

abuse methamphetamine.2,3 Methamphetamine is a stimulant, very addictive, and induces wakefulness

and excessive physical activity. The adverse side effects include elevated blood pressure, cardiac arrhythmias, hallucinations, and bizarre and often violent behavior.

A severe form of oral disease characterized by extensive dental caries, worn teeth, and periodontal disease was first described by two emergency department physicians in 2000.3 Since that

time, there have been a number of published case reports or case series, often appearing in local dental journals,4-6 suggesting a clustering of cases in certain areas of the United States. However meth

mouth, as this has come to be known, is an international problem, reported in Europe,7 Taiwan,8 and

South Africa.9 The oral findings in persons with meth mouth are believed to be due to xerostomia,

excessive tooth clenching, a lack of concern about oral hygiene, and increased consumption of sugarsweetened beverages.

Early reports were limited by the number of cases that were reported, not allowing conclusions

regarding prevalence or distribution by age, sex, or drug use. Shetty and colleagues,3 however, have published the findings of a study of methamphetamine users in the Los Angeles, California, area.

This study used a stratified sampling approach to assess the oral status of a large sample of methamphetamine users. A total of 571 individuals were examined and divided into light, moderate, and heavy

users. The majority were male, and either Hispanic or African-American. Nearly 70% were currently

using cigarettes. The oral findings revealed extensive severe oral disease. Being older and a moderate or

heavy user were associated with more extensive caries, periodontal disease, and tooth loss. Women were

affected to a greater degree than men. Molars were the teeth that demonstrated the greatest extent and

severity of oral disease, and maxillary anterior teeth demonstrated greater caries experience than mandibular anterior teeth. Of all users, 96% had evidence of caries and nearly 60% had untreated caries.

Periodontitis was also common in these individuals, with nearly 60% of moderate/heavy methamphetamine users demonstrating moderate periodontitis and nearly one-third demonstrating severe

periodontitis. Further, a majority of the methamphetamine users reported embarrassment as a result of

their oral condition.

The onset of this relatively new oral syndrome highlights the pressing need for oral healthcare

providers (OHCPs) to take a broader view of their role in patient care. First, patients presenting with the

conditions seen in these reports require more than dental care alone. If seeing a patient with oral findings suggestive of methamphetamine abuse, OHCPs must treat the whole patient, while considering the

need for medical/psychiatric consultation, appropriate management of pain that does not add to the

addictive problems often faced by these patients, and avoidance of drugs used during dental treatment

that may be affected by methamphetamine use (i.e., the cardiac effects of vasoconstrictors such as epinephrine in local anesthetics). This epidemic further emphasizes the importance of interprofessional

practice, and the need for multiple healthcare providers to participate in patient care.

Dental offices can be points of surveillance for newly emerging diseases and

disorders, and also provide opportunities for OHCPs to have a positive impact

on the overall health of persons in their care.

Second, the appearance of meth mouth also stresses that OHCPs must be vigilant for the next new

oral disorder or manifestation of a systemic condition. In recent years bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (BRONJ), as well as peri-implant mucositis and perimplantitis, have been identified. Thirty

years ago it was a variety of newly identified oral manifestations of HIV infection, including hairy leukoplakia and HIV-associated periodontitis.

Dental offices can be points of surveillance for newly emerging diseases and disorders, and also provide opportunities for OHCPs to have a positive impact on the overall health of persons in their care. O

C

References

1.

2.

Earn 3 CE credits

for this issue

of the

Oral Care Report

online at

www.colgateprofessional.com.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

American Dental Association. ADA News. MyView: Meth: the loss of Americas smile. Available from:

http://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/viewpoint/my-view/2016/may/meth-the-loss-of-americas-smile.

Accessed 16 May 2016.

Richards JR, Brofeldt BT. Patterns of tooth wear associated with methamphetamine use. J Periodontol 2000;71(8):

1371-4.

Shetty V, Harrell L, Murphy DA, Vitero S, Gutierrez A, Belin TR, Dye BA, Spolsky VW. Dental disease patterns

in methamphetamine users: Findings in a large urban sample. J Am Dent Assoc 2015;146(12):875-85.

Jones K. Meth mouth: one dentists personal experience. J Mich Dent Assoc 2011;93(2):60-1.

Settle SL. Meth mouth for the general practitioner. J Okla Dent Assoc 2010;101(8):31-42.

Brown RE, Morisky DE, Silverstein SJ. Meth mouth severity in response to drug-use patterns and dental access