Jpids Pis043 Full

Diunggah oleh

Rani Eva DewiJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Jpids Pis043 Full

Diunggah oleh

Rani Eva DewiHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society Advance Access published April 5, 2012

Case Report

Ustilago as a Cause of Fungal Peritonitis: Case Report

and Review of the Literature

J. Chase McNeil and Debra L. Palazzi

Department of Pediatrics, Section of Infectious Diseases, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas

Corresponding Author: J. Chase McNeil, MD, 1102 Bates St, Ste 1150, Houston, TX 77030. E-mail:

Jm140109@bcm.tmc.edu.

Received December 15, 2011; accepted February 17, 2012.

Fungal peritonitis is an uncommon complication of ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in children and

often necessitates catheter removal, prolonged hospitalization and conversion to hemodialysis. The

majority of these infections are due to Candida albicans and related species. We present an uncommon

case of peritonitis due to the unusual plant pathogen Ustilago.

CASE

A 3-year-old Latin American male with a complex

medical history notable for hypertension, end-stage

renal disease secondary to posterior urethral valves

and obstructive uropathy and chronic peritoneal dialysis (PD) presented with abdominal pain, vomiting and

diarrhea. The patient was found to be hypovolemic

and hyperkalemic and was admitted to the nephrology

service for rehydration and correction of electrolyte

derangements with a working diagnosis of viral gastroenteritis. At home his mother was responsible for

performing his PD. The patient did not have a history

of foreign travel. His diet included traditional

Mexican foods, but he denied consumption of unpasteurized dairy products. On hospital day 5, he

uncapped his PD catheter and inserted a yellow

crayon on which he had been chewing. The crayon

was extracted without difculty and did not enter the

peritoneal cavity; the crayon was discarded and not

sent for culture.

The following day, the patient developed fever to

101 F along with worsening abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhea. During dialysis, the peritoneal uid

was noted to be cloudy and was sent for cell count

and culture. Peritoneal uid white blood cell count

was 1530 cells/mm3, with 43% neutrophils, 16% lymphocytes, 39% monocytes and 2% eosinophils. The

patient was given intraperitoneal vancomycin and ceftazidime pending culture results. His past medical

history was signicant for three previous episodes

of documented infectious peritonitis with Candida

parapsilosis (3.5 years prior), Staphylococcus epidermidis (3 years prior) and group A Streptococcus

(1.5 years prior). Due to persistent fever and symptoms, intraperitoneal uconazole was added to the

patients regimen on hospital day 8.

The initial peritoneal uid culture grew a fungus

that contained both hyphae and yeast forms, and peritoneal uid cultures continued to grow fungus for 11

consecutive days. The patient continued to have fever,

abdominal pain and diarrhea despite intraperitoneal

uconazole. Blood aerobic, anaerobic and fungal

cultures did not yield a pathogen. Serum was sent for

the 1,3 -D-glucan assay and was negative.

The infectious diseases service was consulted to

assist with management on hospital day 19 and

recommended liposomal amphotericin B 5 mg/kg/dose

intravenously once daily and PD catheter removal.

The patient underwent removal of the PD catheter on

hospital day 20 and was started on intermittent hemodialysis. An abdominal ultrasound was performed

which revealed no evidence of abscess.

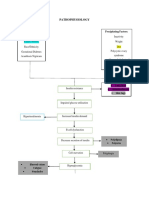

The fungus identied in peritoneal cultures produced very mucoid colonies on Sabouraud dextrose

agar (Figure in supplemental content). It was urease

positive and initially identied by Vitek 2 (Biomriux,

Sweden) as a Cryptococcus species. Based on morphology, however, it was felt that the organism more

Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society pp. 13, 2012

DOI:10.1093/JPIDS/PIS043

The Author 2012. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: journals.permissions@oup.com.

McNeil and Palazzi

closely resembled one of the smut fungi. The fungus

was sent to the Fungal Identication and Susceptibility

Laboratory at the University of Texas Health Science

Center at San Antonio for further identication. DNA

was isolated and subjected to sequencing studies

which revealed the organism belonged to the Ustilago

genus 20 days after the culture was initially obtained.

The isolate was not viable for further studies and

susceptibility testing.

Upon learning of the identication of the fungus,

our consult service recommended stopping amphotericin and starting itraconazole 5 mg/kg/d on hospital

day 27 to complete a 21-day course post-catheter

removal. Of note, the patient had pronounced

improvement in symptomatology following catheter

removal even prior to changing antifungal agents.

He continued on intermittent hemodialysis and was

discharged to home in good condition. He underwent

reinitiation of peritoneal dialysis approximately

1 month later and is currently doing well.

DISCUSSION

Infectious peritonitis is a known complication of ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in children. Fungi accounted

for 2.9% of cases of peritonitis in children in one large

series, with previous episodes of peritonitis being a welldescribed risk factor [1]. Among the 51 episodes of

fungal peritonitis in this series, 79% of cases were

caused by Candida species. A number of other clinically

important fungi have been noted to cause peritonitis in

the setting of peritoneal dialysis, notably Rhodotorula,

Rhizopus, Aspergillus spp., Cryptococcus neoformans

and Histoplasma capsulatum [2, 3]. Ustilago spp. are a

particularly unusual cause of fungal peritonitis, to the

best of our knowledge, being described only once in a

series of 51 patients [1].

Organisms of the genus Ustilago are often referred

to as smut fungi, basidiomycete molds that are

common environmental organisms. The basidiomycete

fungi include the smuts which are well described as

edible mushrooms, as well as pathogens of grain

crops. Notably, this grouping also includes fungi of

importance in human disease; the most clinically

signicant organism in this class is Cryptococcus

neoformans [4]. These organisms are lamentous in

nature, however, they can develop into haploid yeast

forms in culture media; these factors likely contributed

to the initial difculty in identication of the pathogen

in the case presented.

The Ustilaginales are specialized to parasitize a

number of valuable crop species such as corn,

sorghum, wheat and barley. Prominent among this

group is Ustilago maydis (sometimes referred to as

U. zeae), the etiologic agent of corn smut. U. maydis

infection of corn leads to the development of tumorlike growths on the aerial portions of the plant, affecting the growth and viability of the crop [4, 5].

Furthermore, large consumption of contaminated corn

has been associated with an alkaloid-like toxidrome in

cattle, the staggers. Ustilago spp., however, are

often used in Latin American cuisine where it is better

known as huitlacoche [6]; the fungus is frequently

included as an ingredient in tortilla-based dishes.

There is a paucity of literature on the role that

Ustilago spp. may play in human disease. A strong

association has been described between skin hypersensitivity to spores of smut fungi, including U. maydis,

and allergic rhinitis and asthma [4, 7]. Teo reported

the case of a 23-year-old Chinese woman with a dermatitis whose skin scraping fungal cultures grew

Ustilago spp.; the patients pet guinea pig was suffering from a scaly rash on its paws which also grew

Ustilago spp. [8]. There are very few reports of invasive disease due to Ustilago in humans. One of the

earliest cases was reported by Moore et al in 1946 in

an adult farmer who died of chronic leptomeningitis;

at autopsy fungal elements consistent with Ustilago

maydis were found in brain tissue, however no cultures were available [9]. In addition there is a single

case report of a central line associated bloodstream

infection (CLA-BSI) due to U. maydis [10], and a

report of hypersensitivity pneumonitis related to

exposure to U. esculenta [11]. CLA-BSI due to

Pseudozyma aphidis, a related Ustilagomycete, has

been described in a child who consumed large quantities of corn tortilla chips [12]. Furthermore, there are

additional reports of invasive disease in immunocompromised hosts due to other edible basidiomycetes,

such as the mushroom Volvariella volvacea [13].

There are, however, limited data on invasive infections

by organisms of the Ustilago genus in pediatrics. In

terms of pathogenesis in the case presented, the most

logical explanation seems that the childs peritoneal

cavity and catheter became contaminated from insertion of the crayon that may have been colonized with

Ustilagomycetes from the environment and the childs

oral cavity. While our patient denied consumption

of huitlacoche, he did consume other traditional

Mexican foods including homemade corn tortillas

which would be consistent with this mechanism.

Ustilago Fungal Peritonitis

Given the limited data on Ustilago in human disease,

formulating specic recommendations for treatment

are difcult. Based on the few reports of invasive infection due to Ustilago and related organisms, the

minimum inhibitory concentrations tend to be lowest

for itraconazole followed by amphotericin and uconazole [10, 12]. There are no available data on the use of

echinocandins in these infections. Itraconazole has

been used in the few reports of human infection due to

Ustilago spp. and related organisms for which specic

antifungal therapy has been prescribed and this inuenced our decision to change antifungal agents [8, 12].

It is worth noting that our patient had prompt

improvement in symptoms after removal of the peritoneal dialysis catheter, and that device removal may be

necessary in the setting of infection with this organism.

In addition, the reported case of Ustilago CLA-BSI was

treated with catheter removal alone and not systemic

antifungals with success [10].

In summary, we report an unusual case of peritonitis

in a pediatric patient due to Ustilago spp. While traditionally thought of as only a plant pathogen, there

continues to be emerging data that this agent can play

a role in human disease. Moreover, this case highlights

the importance of considering environmental fungi in

clinical practice. Continued research into antifungal

options for these organisms is warranted.

References

1. Warady BA, Bashir M, Donaldson LA. Fungal peritonitis in children receiving peritoneal dialysis: a report

of the NAPRTCS. Kidney Int. 2000; 58:384389.

2. Raaijmakers R, Schroder C, Monnens L,

Cornelissen E, Warris A. Fungal peritonitis in

children on peritoneal dialysis. Pediatr Nephrol.

2007; 22:288293.

3. Bibashi E, Memmos D, Kokolina E, Tsakiris D,

Soanou D, Papadimitriou M. Clin Infect Dis.

2003; 36:927931.

4. Lacazo CdS, Heins-Vaccarri EM, Takahashi de

Melood N, Hernandez-Arriaga GL. Basidiomycosis:

a review of the literature. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao

Paulo. 1996; 38:379390.

5. Brefort T, Doehlemann G, Mendoza-Mendoza A,

Reissmann S, Djamei A, Kahmann R. Ustilago

maydis as a pathogen. Annu Rev Phytopathol.

2009; 47:423445.

6. Valverde ME, Paredes-Lopez O, Pataky JK,

Guevara-Lara F. Huitlacoche (Ustilago maydis) as a

food sourcebiology, composition and production.

Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1995; 35:191229.

7. Santill J, Rockwell WJ, Collins RP. The signicance of the spores of the Basidiomycetes

(mushrooms and their allies) in bronchial

asthma and allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy. 1985;

55:469471.

8. Teo LHY, Tay YK. Ustilago species infection in

humans. Br J Derm. 2006; 154:10961097.

9. Moore M, Russell WO, Sachs E. Chronic leptomeningitis and ependymitis caused by Ustilago,

probably U zeae (corn smut). Am J Pathol. 1946;

22:761777.

10. Patel R, Roberts GD, Kelly DG, Walker RC.

Central venous catheter infection due to Ustilago

species. Clin Infect Dis. 1995; 21:10431044.

11. Yoshida K, Suga M, Yamasaki H, Nakamura K,

Sato T, Kakishima M, et al. Hypersensitivity

pneumonitis due to a smut fungus Ustilago esculenta. Thorax. 1996; 51:650651.

12. Lin SS, Pranikoff T, Smith SF, Brandt ME,

Gilbert K, Palavecino EL, et al. Central venous

catheter infection associated with Pseudozyma

aphidis in a child with short gut syndrome. J Med

Microbiol. 2008; 57:516518.

13. Salit RB, Shea YR, Gea-Banacloche J, Fahle GA,

Abu-Asab M, Sugui JA, et al. Death by edible

mushroom: rst report of Volvariella volvacea as

an etiologic agent of invasive disease in a patient

following double umbilical cord blood transplantation. J Clin Microbiol. 2010; 48:43294332.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- InfluenzaDokumen19 halamanInfluenzapppammBelum ada peringkat

- Mrcem Primary June 2022 Recalls Compiled by DR Sumair HameedDokumen4 halamanMrcem Primary June 2022 Recalls Compiled by DR Sumair HameedSHK100% (1)

- Gram-Negative Rods Related To AnimalDokumen35 halamanGram-Negative Rods Related To AnimalAsa Mutia SBelum ada peringkat

- History of VaccineDokumen17 halamanHistory of VaccineFreekoo NairBelum ada peringkat

- CH 14 Digestive-SystemDokumen179 halamanCH 14 Digestive-SystemAntonio Calleja IIBelum ada peringkat

- Pankaj Das - Aarogyam 1.2 + FBSDokumen10 halamanPankaj Das - Aarogyam 1.2 + FBSplasmadragBelum ada peringkat

- Enteral Nutrition Administration Inconsistent With Needs (NI-2.6)Dokumen2 halamanEnteral Nutrition Administration Inconsistent With Needs (NI-2.6)Hasna KhairunnisaGIZIBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan On PhysiologicalDokumen22 halamanLesson Plan On PhysiologicalruchiBelum ada peringkat

- Aspergillus and Vaginal Colonization-2329-8731.1000e115Dokumen2 halamanAspergillus and Vaginal Colonization-2329-8731.1000e115Hervis Francisco FantiniBelum ada peringkat

- Case Report Pasteurella Multocida Septicemia in A Patient With CirrhosisDokumen4 halamanCase Report Pasteurella Multocida Septicemia in A Patient With CirrhosisSilviyah MujionoBelum ada peringkat

- My SynopsisDokumen45 halamanMy SynopsisSiva RamBelum ada peringkat

- Typhoid DiseaseDokumen28 halamanTyphoid DiseaseSaba Parvin Haque100% (1)

- Bullwho00452 0089Dokumen7 halamanBullwho00452 0089JIRA JINN GONZALESBelum ada peringkat

- 16 3 2010 0350 0351 PDFDokumen2 halaman16 3 2010 0350 0351 PDFSandi ApriadiBelum ada peringkat

- Cryptosporidiosis in Ruminants: Update and Current Therapeutic ApproachesDokumen8 halamanCryptosporidiosis in Ruminants: Update and Current Therapeutic ApproachesDrivailaBelum ada peringkat

- At The Turn of The 20th CenturyDokumen6 halamanAt The Turn of The 20th CenturyStefanosSokratousBelum ada peringkat

- K Pneumoniae-Induced Infections - Case-Series Study in 697 Animals - BJMDokumen10 halamanK Pneumoniae-Induced Infections - Case-Series Study in 697 Animals - BJMANGELA YULEIDY RIVERA VILLARREALBelum ada peringkat

- Parasitic Diseases OMSDokumen13 halamanParasitic Diseases OMSlacmftcBelum ada peringkat

- EBS ProjectDokumen9 halamanEBS Projectdiksha halderBelum ada peringkat

- K-4 PR - Soil Transmitted HelminthiasisDokumen45 halamanK-4 PR - Soil Transmitted HelminthiasissantayohanaBelum ada peringkat

- 4019.NEJM, gastroentDokumen11 halaman4019.NEJM, gastroentbrian.p.lucasBelum ada peringkat

- Diagnosis and Management of Amebiasis: State-Of-The-Art Clinical ArticleDokumen9 halamanDiagnosis and Management of Amebiasis: State-Of-The-Art Clinical ArticleSiscaSelviaBelum ada peringkat

- Providencia InfectionsDokumen2 halamanProvidencia InfectionsEllagEszBelum ada peringkat

- 06 Neurocisticercosis Actualidad y AvancesDokumen7 halaman06 Neurocisticercosis Actualidad y Avancesfeliecheverria11Belum ada peringkat

- UntitledDokumen15 halamanUntitledDagmawi BahiruBelum ada peringkat

- Raccoons ParasitesDokumen2 halamanRaccoons ParasitesEdward McSweegan, PhDBelum ada peringkat

- Typhoid Fever: Disease PrimersDokumen18 halamanTyphoid Fever: Disease PrimersErick HernandezBelum ada peringkat

- MDP 1c Protozoa - Text PDFDokumen13 halamanMDP 1c Protozoa - Text PDFRionaldy TaminBelum ada peringkat

- Enterobius: Anti-Infective AgentsDokumen11 halamanEnterobius: Anti-Infective AgentsIonela VișinescuBelum ada peringkat

- Amebic Colitis: María Carolina Isea, Andrés Escudero-Sepulveda and Alfonso J. Rodriguez-MoralesDokumen20 halamanAmebic Colitis: María Carolina Isea, Andrés Escudero-Sepulveda and Alfonso J. Rodriguez-MoralesNam ChannelBelum ada peringkat

- Enterobacter SakazakiiDokumen7 halamanEnterobacter SakazakiiRadwan AjoBelum ada peringkat

- 1.2 - Bacillus AnthracisDokumen26 halaman1.2 - Bacillus Anthracissajad abasBelum ada peringkat

- Endemicity of Toxoplasma Infection and Its Associated Risk Factors in Cebu, PhilippinesDokumen16 halamanEndemicity of Toxoplasma Infection and Its Associated Risk Factors in Cebu, PhilippinesNamanamanaBelum ada peringkat

- Anuradha NDokumen4 halamanAnuradha NIJAMBelum ada peringkat

- Typhoid Fever PDFDokumen14 halamanTyphoid Fever PDFginstarBelum ada peringkat

- Should All Bacteraemia Be Treated? A Case Report of An Immunocompetent Patient With Campylobacter Upsaliensis BacteraemiaDokumen4 halamanShould All Bacteraemia Be Treated? A Case Report of An Immunocompetent Patient With Campylobacter Upsaliensis Bacteraemiaps piasBelum ada peringkat

- Montes, 2010Dokumen7 halamanMontes, 2010Dianny VacaBelum ada peringkat

- BlastocystisDokumen4 halamanBlastocystisParasito BioudosucBelum ada peringkat

- Hookworm Infection: Causes, Symptoms, TreatmentDokumen6 halamanHookworm Infection: Causes, Symptoms, Treatmentcooky maknaeBelum ada peringkat

- Fish BacteriaDokumen16 halamanFish BacteriaDiego AriasBelum ada peringkat

- Parasitos en ReptilesDokumen13 halamanParasitos en ReptilesEduardo Pella100% (1)

- Course Title: Ruminant and Non-Ruminant Preventive MedicineDokumen32 halamanCourse Title: Ruminant and Non-Ruminant Preventive MedicineFarhan NobelBelum ada peringkat

- Hookworm: Ancylostoma Duodenale and Necator AmericanusDokumen18 halamanHookworm: Ancylostoma Duodenale and Necator AmericanusPutri AmandaBelum ada peringkat

- Resurgence of Diphtheria: Are We Ready To Treat?: Case SeriesDokumen4 halamanResurgence of Diphtheria: Are We Ready To Treat?: Case Seriesisma dewi masithahBelum ada peringkat

- Plagiarism Comparison Scan Report 1698599596Dokumen3 halamanPlagiarism Comparison Scan Report 1698599596ZHENG PANGBelum ada peringkat

- Prevention and Control of Amoebic DysenteryDokumen16 halamanPrevention and Control of Amoebic DysenteryPakSci MissionBelum ada peringkat

- Typhoid Fever: A ReviewDokumen7 halamanTyphoid Fever: A ReviewJesicca SBelum ada peringkat

- PAIR in Vitro Activity of Pandan Pandanus Amaryllifolius Leaves CrudeDokumen23 halamanPAIR in Vitro Activity of Pandan Pandanus Amaryllifolius Leaves CrudeMiftahurrachmahBelum ada peringkat

- Pseudomonas Aeruginosa - Pathogenesis and Pathogenic MechanismsDokumen24 halamanPseudomonas Aeruginosa - Pathogenesis and Pathogenic MechanismsFitryBelum ada peringkat

- Intestinal Coccidian: An Overview Epidemiologic Worldwide and ColombiaDokumen14 halamanIntestinal Coccidian: An Overview Epidemiologic Worldwide and ColombiaMARIA LUCIA PIESCHACÓN CHUZCANOBelum ada peringkat

- Infectious Diseases: GuidelineDokumen34 halamanInfectious Diseases: GuidelineiisisiisBelum ada peringkat

- Nosocomial Infections and Zoonotic Diseases in Veterinary HospitalsDokumen4 halamanNosocomial Infections and Zoonotic Diseases in Veterinary HospitalshansmeetBelum ada peringkat

- Diphtheria: Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Role of Immunization in PreventioDokumen6 halamanDiphtheria: Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Role of Immunization in PreventioNur Rahmat WibowoBelum ada peringkat

- Rudolph PediatricDokumen9 halamanRudolph PediatricMuhammad RezaBelum ada peringkat

- Anthrax of The Gastrointestinal Tract: Thira Sirisanthana and Arthur E. BrownDokumen3 halamanAnthrax of The Gastrointestinal Tract: Thira Sirisanthana and Arthur E. BrownJuli SatriaBelum ada peringkat

- Preventing Campylobacter at The Source: Why Is It So Dif Ficult?Dokumen7 halamanPreventing Campylobacter at The Source: Why Is It So Dif Ficult?Juan Diego Agustin VasquezBelum ada peringkat

- University of Nigeria, Nsukka: Clostridium Difficile From Obscurity To SuperbugDokumen9 halamanUniversity of Nigeria, Nsukka: Clostridium Difficile From Obscurity To SuperbugMabrig KorieBelum ada peringkat

- Bacterial Diarrhea: Clinical PracticeDokumen10 halamanBacterial Diarrhea: Clinical PracticeHugo MarizBelum ada peringkat

- Vervloet Et Al-2007-Brazilian Journal of Infectious DiseasesDokumen8 halamanVervloet Et Al-2007-Brazilian Journal of Infectious DiseasesCynthia GalloBelum ada peringkat

- Sporotrichosis: An Update On Epidemiology, Etiopathogenesis, Laboratory and Clinical TherapeuticsDokumen15 halamanSporotrichosis: An Update On Epidemiology, Etiopathogenesis, Laboratory and Clinical TherapeuticsJuLiethMiRellaLuqueMedinaBelum ada peringkat

- Perbandingan 3 - IndiaDokumen4 halamanPerbandingan 3 - IndiaElva PatabangBelum ada peringkat

- 1 s2.0 S0740002017304409 Main PDFDokumen8 halaman1 s2.0 S0740002017304409 Main PDFDIEGO FERNANDO TULCAN SILVABelum ada peringkat

- Ovarian Abscess Caused by Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhi: A Case ReportDokumen4 halamanOvarian Abscess Caused by Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhi: A Case Reportjuanda raynaldiBelum ada peringkat

- Ajo 01 29Dokumen4 halamanAjo 01 29aulianaBelum ada peringkat

- Cats and Toxoplasma: A Comprehensive Guide to Feline ToxoplasmosisDari EverandCats and Toxoplasma: A Comprehensive Guide to Feline ToxoplasmosisBelum ada peringkat

- Primus 25 Advanced: Innovative PCR-TechnologyDokumen10 halamanPrimus 25 Advanced: Innovative PCR-TechnologyRani Eva DewiBelum ada peringkat

- Lach Etal2010BioInvDokumen11 halamanLach Etal2010BioInvRani Eva DewiBelum ada peringkat

- 87 153 1 SM PDFDokumen12 halaman87 153 1 SM PDFRani Eva DewiBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal KarsinologiDokumen6 halamanJurnal KarsinologiRani Eva DewiBelum ada peringkat

- 793 2320 1 PB PDFDokumen10 halaman793 2320 1 PB PDFRani Eva DewiBelum ada peringkat

- AiM 2016012814355064Dokumen16 halamanAiM 2016012814355064Rani Eva DewiBelum ada peringkat

- SZ Alan Ski 2003Dokumen7 halamanSZ Alan Ski 2003Rani Eva DewiBelum ada peringkat

- The Oligochaeta (Annelida) Fauna of Aksu Stream (Antalya)Dokumen8 halamanThe Oligochaeta (Annelida) Fauna of Aksu Stream (Antalya)Rani Eva DewiBelum ada peringkat

- Bioactivity of Trypsin Inhibitors From Sesame Seeds To Control Plodia Interpunctella Larvae (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae)Dokumen8 halamanBioactivity of Trypsin Inhibitors From Sesame Seeds To Control Plodia Interpunctella Larvae (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae)Rani Eva DewiBelum ada peringkat

- Zoo 29 3 6 0407 1 PDFDokumen8 halamanZoo 29 3 6 0407 1 PDFRani Eva DewiBelum ada peringkat

- Lignocellulolytic - 601Dokumen8 halamanLignocellulolytic - 601Rani Eva DewiBelum ada peringkat

- Gov. Abbott OpenTexas ReportDokumen64 halamanGov. Abbott OpenTexas ReportAnonymous Pb39klJ92% (12)

- Ersoy-Pruritus 5 D Itch ScaleDokumen7 halamanErsoy-Pruritus 5 D Itch ScaleyosefBelum ada peringkat

- PolicyDokumen8 halamanPolicyjoshiaruna539Belum ada peringkat

- Norovirus 201309101051579338Dokumen3 halamanNorovirus 201309101051579338Jeeva maria GeorgeBelum ada peringkat

- Blood ReportDokumen15 halamanBlood ReportSaadBelum ada peringkat

- Template Continued On Page 2: Dose-Dense Ac (Doxorubicin/Cyclophosphamide) CourseDokumen2 halamanTemplate Continued On Page 2: Dose-Dense Ac (Doxorubicin/Cyclophosphamide) CourseJaneBelum ada peringkat

- The Cotton DriverDokumen2 halamanThe Cotton DriverDanny Eduardo RomeroBelum ada peringkat

- Pathophysiology: Predisposing Factors: Precipitating FactorsDokumen2 halamanPathophysiology: Predisposing Factors: Precipitating FactorsJemsMei Comparativo MensuradoBelum ada peringkat

- Central Venous Pressure (CVP) Monitoring Using A Water ManometerDokumen5 halamanCentral Venous Pressure (CVP) Monitoring Using A Water ManometerBsBs A7medBelum ada peringkat

- Kumpulan Refarat Co-Ass Radiologi FK UntarDokumen15 halamanKumpulan Refarat Co-Ass Radiologi FK UntarErwin DiprajaBelum ada peringkat

- HV-400 Electrosurgical Generator Technical Specs and FeaturesDokumen2 halamanHV-400 Electrosurgical Generator Technical Specs and FeaturesJarnoBelum ada peringkat

- Birth StoryDokumen2 halamanBirth Storyapi-549201461Belum ada peringkat

- To Extract Ornot To Extract PDFDokumen2 halamanTo Extract Ornot To Extract PDFmehdi chahrourBelum ada peringkat

- AJEERNA (Indigestion)Dokumen37 halamanAJEERNA (Indigestion)m gouriBelum ada peringkat

- Review of Influenza as a Seasonal and Pandemic DiseaseDokumen12 halamanReview of Influenza as a Seasonal and Pandemic DiseaseFreddy SueroBelum ada peringkat

- ADC Part 1 - TG Keynotes II v1.0 PDFDokumen17 halamanADC Part 1 - TG Keynotes II v1.0 PDFDrSaif Ullah KhanBelum ada peringkat

- R9 R10 R11 - MEMO INVI - Training On VPD and AEFI SurveillanceDokumen2 halamanR9 R10 R11 - MEMO INVI - Training On VPD and AEFI SurveillanceirisbadatBelum ada peringkat

- The Value of Urine Specific Gravity in Detecting Diabetes Insipidus in A Patient With DMDokumen2 halamanThe Value of Urine Specific Gravity in Detecting Diabetes Insipidus in A Patient With DMFaryalBalochBelum ada peringkat

- Vit A DeficiencyDokumen27 halamanVit A DeficiencyNatnaelBelum ada peringkat

- MCQ MedicineDokumen4 halamanMCQ MedicineKasun PereraBelum ada peringkat

- Complete Physical Exam AbbreviationsDokumen4 halamanComplete Physical Exam Abbreviationseal772328Belum ada peringkat

- JNatlComprCancNetw 2015 Nabors 1191 202Dokumen13 halamanJNatlComprCancNetw 2015 Nabors 1191 202Reyhan AristoBelum ada peringkat

- Cancer: Get A Cancer Cover of ' 20 Lakhs at Less Than ' 4 / DayDokumen6 halamanCancer: Get A Cancer Cover of ' 20 Lakhs at Less Than ' 4 / DayUtsav J BhattBelum ada peringkat

- 2023 - ACRM - Diagnositc - CriteriaDokumen13 halaman2023 - ACRM - Diagnositc - CriteriaRobinBelum ada peringkat