After Action Review AJEM

Diunggah oleh

eftychidisHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

After Action Review AJEM

Diunggah oleh

eftychidisHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

American Journal of Emergency Medicine 31 (2013) 798802

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

American Journal of Emergency Medicine

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ajem

Original Contribution

An after-action review tool for EDs: learning from mass casualty incidents,,

Greenberg Tami M.EM a, Adini Bruria PhD a, b,, Eden Fabiana M.EM a, Chen Tami M.EM a,

Ankri Tali M.EM a, Aharonson-Daniel Limor PhD a, b

a

Department of Emergency Medicine, The Leon and Mathilda Recanati School for Community Health Professions, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev,

Beer-Sheva, Israel

b

PREPARED Research Center, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 19 January 2013

Accepted 23 January 2013

a b s t r a c t

Background: Conducting a thorough after-action review (AAR) process is an important component in

improving preparedness for mass casualty incidents (MCIs).

Purposes: The study aimed to develop a structured AAR tool for use by medical teams in emergency

departments after an MCI and to identify the best possible procedure for its conduct.

Basic procedures: On the basis of knowledge acquired from an extensive literature review, a structured tool for

conducting an AAR in the emergency department was developed. A modied Delphi process was conducted

to achieve content validity of the tool, involving 48 medical professionals from all 6 level I trauma centers in

Israel. The AAR tool was tested during a simulated MCI drill.

Main ndings: All experts support the conduct of an AAR in the ED after an MCI to build and maintain capacity

for an adequate emergency response. More than 80% agreement was achieved regarding 14 components that

were implemented in the proposed AAR tool. Ninety-four percent perceived that AARs should be conducted

within 24 hours from the event using both written reports and face-to-face discussions. Both physicians and

nurses should participate. The incident manager should lead the AAR, limiting the time allocated for each

speaker and for the AAR in whole.

Principle conclusions: Conducting a structured AAR in all emergency departments after an MCI facilitates both

learning lessons regarding the function of the medical staff and ventilation of feelings, thus mitigating

anxieties and expediting a speedy return to normalcy.

2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Background

Emergency management of mass casualty incidents (MCIs) is

characterized by a need to respond swiftly to unexpected complex

situations [1]. Often, MCIs necessitate admitting and treating multiple

injuries in casualties of varying types and severities, requiring the

deployment of multidisciplinary medical teams at receiving hospitals

[1]. Decision-making processes used during a response for MCIs

Authors contributions: Joint rst authorship: T.G. and B.A. jointly participated in

writing the manuscript. G.T., E.D., C.T., and A.T. conceived the study and designed the

modied Delphi and exercise. A.B. and A.D.L. supervised the conduct of the study and

data collection. A.B. and A.D.L. provided advice on study design and analysis of the data.

G.T. and A.B. drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its

revision. A.B. takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

There are no conicts of interests and no nancial support.

The manuscript was presented in the International Preparedness and Response for

Emergencies and Disasters 2012 conference.

Corresponding author. Department of Emergency Medicine, The Leon and

Mathilda Recanati School for Community Health Professions, Ben-Gurion University

of the Negev, POB 653, Beer-Sheva 84105, Israel. Tel.: +972 54 804 5700; fax: +972 77

910 1882.

E-mail address: adini@netvision.net.il (A. Bruria).

0735-6757/$ see front matter 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2013.01.025

differ from routine protocols; therefore, lessons learned and

experiences gathered from various MCIs should be studied,

integrated into the organizational knowledge base, and implemented

in future situations [2].

Emergency departments (EDs) are a central component of the

response model for MCIs because they admit, triage, and provide

lifesaving medical care to a large number of casualties [3]. The need to

expand capacity to meet the surge created by the MCI, as well as

additional activities and pressures exerted on the medical teams,

varies signicantly from the routine function of the ED staff [4].

Frequently, as a result of the complex medical condition of the

casualties that are admitted and the external personnel that are

deployed to reinforce the routine workforce to better manage the MCI,

gaps in communication and coordination are created in the ED,

resulting in a less-than-optimal response to the situation [2,5,6].

As mentioned earlier, an important component in improving

preparedness for MCIs is learning lessons from both exercises and

real-life events. The most common method for reviewing what

happened and identifying ways to improve future performance is

through an after-action review (AAR) [5,7,8]. An AAR seeks to present

answers to questions such as What was supposed to happen? What

799

G. Tami et al. / American Journal of Emergency Medicine 31 (2013) 798802

actually happened? Why were there differences? What gaps

materialized between planning and execution? What can we learn

from this experience? [2,9]. After-action reviews are designed to

facilitate learning from errors and from successes, to identify

strengths that should be maintained and weaknesses that should be

rectied, and to reveal misses and near-misses [2,5,7,9]. After-action

reviews have the potential to enhance organizational sensitivity and

resilience and provide opportunities to acknowledge individual and

institutional expertise [7]. It has been recommended that AAR be

conducted soon after the MCI has concluded, regardless of whether

negative results have occurred [7,9].

1.1. Importance

After-action reviews are used constantly in military settings based

on advanced tools that have been created to facilitate this process

[10,11]. Implementation of AARs after an MCI is highly encouraged in

civilian settings too, but structured tools that can be used for this

purpose are lacking [6,12]. To date, there is no validated, widely

accepted AAR tool that can be used by medical institutions to guide

and improve their preparedness and response for emergencies; more

so, the few performance-based tools that were developed have not

been fully tested for reliability and validity [13].

Effective management of the AAR must be used in order for the

framework to facilitate understanding and insights to the lessons to

be learned, as well as awareness and agreement on actions that should

be taken to improve emergency response to future events [9]. Topics

for discussion, expectations of the AAR process, and methodology for

its conduct must be professionally prepared to assure effectiveness

[9,14]. In light of the importance of learning lessons after an MCI and

the need to use an effective mechanism for optimizing the process in

the ED, the current study was designed.

1.2. Goals of this investigation

The study aimed to use a scientic approach for developing a

structured AAR tool for the use of medical teams in the ED after

an MCI. The study further sought the best possible procedure for

its conduct.

2. Methods

An extensive literature review of components relevant to response

of EDs to MCIs and tools that are in place in military and civilian

settings was conducted. Based on the knowledge acquired, a

structured tool for conducting an AAR in the ED was developed.

To estimate the content validity of the tool, a modied Delphi

process was conducted involving medical teams from all 6 level I

trauma centers in Israel. The AAR tool was disseminated to 48 staff

(physicians and nurses), requesting their opinions regarding the

following issues: their perception of the need for review of ED

performance after an MCI, relevance of the various components of the

AAR tool with regard to the goal of learning lessons following an MCI,

preferred format for evaluating those elements, and recommendations regarding modications that are needed in the proposed tool or

the procedure through which it should be conducted. The recommendations were evaluated, and the level of consensus between the

various content experts was compared. The required level of

agreement between experts was predened as 80% or higher. On

the basis of these recommendations, revisions were made to the

preliminary AAR tool, which was then tested during a drill simulating

an MCI scenario. Subsequently, the revised tool was reviewed by

medical staff of a hospital that participated in the previously

mentioned drill, both before and immediately after the drill. The

process of the study is described in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Process for developing and validating the AAR tool.

3. Results

3.1. Tool structure

The tool consisted of 3 main sections:

1. Closed questions regarding the function of the ED's medical

teams during the emergency response (such as use of

equipment, personal safety, registration, etc)

2. Closed questions pertaining to ED managers (such as control

and command, manpower operation, and patient evacuation)

3. Open-ended questions focusing on ventilating emotions and

reections of the medical staff during and after the event (such

as effectiveness of support teams, feeling of security, and

personal lessons learnt).

3.2. Results of the modied Delphi process regarding the development of

the AAR tool

Of 48 content experts from the EDs of the 6 level I trauma centers,

39 responded to the modied Delphi (81% response rate). Thirtythree (85%) of them were involved in 3 or more MCIs, within the

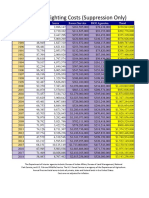

Table 1

Characteristics of the respondents to the modied Delphi cycle

Topic

Characteristic

% of content

experts (n = 39)

Professional experience

1-5 y

6-10 y

11-15 y

N15 y

Experienced in the last year

Experienced in the last 3 y

Experienced in the last 4 y

No previous experience

No experience

Experienced one MCI

Experienced 3-5 MCIs

Experienced N5 MCIs

13

18

10

59

62

23

7.5

7.5

7.5

7.5

15

70

Time frames of previous

experience in MCIs

Extent of previous

experience in MCIs

800

G. Tami et al. / American Journal of Emergency Medicine 31 (2013) 798802

Table 2

Levels of agreement among content experts regarding relevance of the different

components that should be incorporated in the AAR tool

Level of agreement (n = 39) (%)

No. of parameters

% of parameters

100

90-99

80-89

60-79

30-59

b30

Total

4

8

2

0

1

3

18

22

44

11

0

6

17

100

previous 3 years. The characteristics of the respondents are summarized in Table 1.

All experts (n = 39) expressed the view that an AAR must be

conducted in the ED after an MCI and that this action is an important

component of building and maintaining capacity for an emergency

response. An agreement of more than 80% was achieved regarding 14 of

18 components that were identied in the literature review and

implemented in the proposed AAR tool. The levels of agreement among

content experts regarding the relevance of the different components

that should be incorporated in the tool are presented in Table 2. The 4

components that did not achieve the targeted level of agreement

between content experts (annotated by gray background in the table)

included the following: (1) Do you have recurrent disturbing visions

(thoughts) regarding the MCI? (33% supported inclusion in the AAR).

(2) Describe pictures from the MCI that you remember well (18%

supported inclusion in the AAR). (3) Do you suffer from sleep

deprivation as a result of the MCI? (10% supported inclusion in the

AAR). (4) Who do you conde in regarding the complex elements that

you have experienced? (13% supported inclusion in the AAR).

Almost all (94%) experts believe that AARs should be conducted

within a short time span from the event, ranging from immediately

(86%) to no longer than within 24 hours (8%). Only 2 content experts

(6%) think that the AAR can be conducted within 3 days or longer from

the occurrence of the MCI. The format of the AAR should consist of a

combination of techniques, using both written reports and face-toface discussions (n = 35; 89%). Finally, an agreement of 80% and

above was reached between experts regarding the preferred format

for conducting the AARs, including who should manage the

procedure, which professions should be included, and overall time

that should be allotted for the AAR and for each individual speaker.

The positions of the content experts regarding the preferred format

for conducting the AARs are presented in Fig. 2.

3.3. Results of the modied Delphi process regarding the pilot study

Six (75%) of 8 content experts from the hospital that participated

in the MCI drill responded to the questionnaire before and after the

drill. Their answers were identical before and after the drill. The

additional 2 professional who did not respond in writing stated orally

to the researchers of this study that their position regarding all aspects

of the questionnaire had not changed and their initial responses to the

rst Delphi cycle were equally valid for the second cycle. The AAR tool

was modied according to the Delphi ndings, and the pilot study and

is presented in Annex 1.

4. Limitations

The study was conducted among content experts from the 6 level I

trauma centers in Israel and did not encompass all 28 acute care

hospitals in the country. Nevertheless, the assumption is that these

sophisticated trauma centers are the most experienced and best

prepared for MCIs; therefore, their leading ED staff are best equipped

to review the proposed AAR tool.

Another limitation that should be considered is the absence of

structured AAR tools for EDs designated for use after a mass casualty

event. Therefore, it was not possible to compare the proposed tool to

similar tools, being used at various hospitals.

5. Discussion

Effective management of MCIs requires development and use of

structured management tools including AARs [1,2,5,11]. After-action

reviews must be conducted in a nonjudgmental manner, focusing on

learning and constructive criticism aimed at improving readiness for

future emergency events [6]. A structured format is required for

managing AARs, to understand expectations and perspectives of

personnel involved in the MCI, generate insight to strengths and

weaknesses, change behaviors, and achieve agreement concerning

needed actions [9]. On the basis on the opinion of content experts who

participated in this study, it can be inferred that a structured AAR tool

Fig. 2. Views of content experts regarding preferred format for conducting the AAR.

801

G. Tami et al. / American Journal of Emergency Medicine 31 (2013) 798802

would facilitate the opportunity of ED medical personnel to learn

lessons and express emotions after MCIs, thus improving performance

in the next emergency event.

The literature describes various tools for conducting AARs in

military settings and recommends their implementation in civilian

medical facilities [6,9-12]. It has often been stated that implementation of AARs after MCIs is important to promote an effective learning

opportunity, encourage ongoing improvement, and guide action to

enhance patient safety and care [2,7,9,15]. However, although the ED

is a dominant actor in responding to MCIs, the existing tools are not

well suited for conducting AARs in this department [16].

As part of the current study, a tailor-made AAR tool was developed

specically targeted at the ED. The tool enables physicians and nurses

to systematically examine their performance during an MCI, learn

lessons and share their thoughts, conclusions, and feelings, in a

friendly nonjudgmental atmosphere. The tool was applied before and

after an MCI drill at a hospital's ED. The high consensus levels that

were achieved in response to the newly developed AAR tool and its

endorsement by the participating medical teams, both before and

after the drill, seem to indicate that the staff recognizes the

importance and benet of performing AARs of MCIs.

The developed AAR tool can be instrumental for both routine

medical teams that are used in EDs and reinforcing personnel that are

deployed to this department upon occurrence of an MCI [2,15]. As was

found in other studies, the AAR tool may enable staff involved in an

MCI to share their emotions and receive support from their colleagues,

prevent anxieties, and facilitate a speedy return to readiness [2,7,14].

Existing literature has brought to light the fact that a mass casualty

event is, at times, also a multicaregiver event. For this reason, friction

often exists between different sectors [4] and must be discussed as part

of any AAR. The ndings of the current study recognize and support the

need for joint operation of the 2 professions. Therefore, it is

recommended that the AAR be conducted with the participation of

both physicians and nurses under the leadership of the ofcial who

functioned as the facility's incident manager during the MCI.

6. Conclusions

To enhance preparedness for MCIs, a structured AAR should be

conducted in EDs, immediately or within a short time frame, after an

MCI. Contents of such an AAR and its format for implementation have

been proposed in the present study. The AAR should incorporate

written reports and face-to-face discussions, with joint participation

of both physicians and nurses. The incident manager should lead the

AAR where the time allocated for the AAR and for each speaker should

be limited. The process of AAR will not only facilitate learning lessons

regarding the function of the medical staff but also enable ventilation

of feelings, thus mitigating anxieties and facilitating a speedy return to

normalcy. It is highly recommended that such an AAR tool and

procedure be implemented in all hospitals' EDs.

The results of the current study suggest that use of a customized

AAR tool could prove to be productive for other hospital's units

involved in the response to MCIs, as well as rst responders such as

ambulance crews, police, and reghters.

Annex 1. AAR tool

Yes

No

Clarify:

No

Clarify:

3. Did you act according to the security and safety precautions

procedure?

Yes

No

Clarify:

4. Is there a unidirectional track for all casualties (separate

entrances and exits)?

Yes

No

Clarify:

5. Were the registration and documentation of every identied and

anonymous casualty carefully and effectively monitored?

Yes

No

Clarify:

6. Was there a need to reinforce the ED with external emergency

equipment? If so, was the reinforcement performed effectively?

Yes

No

Clarify:

7. Was there sufcient support of reinforcing teams in the MCI, such

as stretcher-bearers, security personnel, social workers, etc?

Yes

No

Clarify:

Specic questions for ED medical and nursing managers

8. How secure and competent did you feel in operating reinforcing

medical and nursing teams, as well as additional team members?

Yes

No

Clarify:

9. Do you think the crew was allocated within the admitting sites

according to their skills, capabilities, and expertise?

Yes

General questions for all participating staff (physicians and nurses)

1. In your opinion, was the ED sufciently staffed during the MCI with

nursing and medical staff to care for all patients and casualties?

Yes

2. Were the necessary equipment and supplies accessible?

No

Clarify:

10. Did you feel that you were in control of the event (condence

in your functional skills and professional knowledge)?

Yes

No

Clarify:

802

G. Tami et al. / American Journal of Emergency Medicine 31 (2013) 798802

11. Were the evacuation and discharge of patients performed in a

structured process at a dened discharge location?

Yes

No

Clarify:

Open-ended questions

12. What emotions arose in you during and after the event?

13. Did you feel condent in your function and performance

throughout the MCI?

14. What personal lessons have you learned from the event? What

elements will you maintain? What elements will you improve?

References

[1] Halpern P, Tsai MC, Arnold JL, Stok E, Ersoy G. Mass-casualty, terrorist bombings:

implications for emergency department and hospital emergency response (part

II). Prehosp Disaster Med 2003;18(3):23541.

[2] Schindler M, Eppler MJ. Harvesting project knowledge: a review of project

learning methods and success factors. International J Project Management

2003;21:21928.

[3] Administration USF. The After-Action Critique: Training Through Lessons Learned.

Department of Homeland Security, 2008 April 2008. Report No:USFA-TR-159.

[4] Juffermans J, Bierens JJ. Recurrent medical response problems during ve recent

disasters in the Netherlands. Prehosp Disaster Med 2010;25(2):12736.

[5] Baily C. Application of the After-Action Review Paradigm to Fire Department

Operation. tinhelmetcom.

[6] Fishbane M, Kist A, Schiever RA. Use of the emergency incident command system

for school-located mass inuenza vaccination clinics. Pediatrics 2012;129(supplement 2):S1016.

[7] Allen JA, Baran BE, Scott CW. After-action reviews: a venue for the promotion of

safety climate. Accid Anal Prev 2010;42:7507.

[8] Fontaine M, Martin GA, Daly J, Thurston C. Technological and usability-based

aspects of distributed after action review in a game-based training setting. In:

Harris D, editor. Engin. Psychol. And Cog. Ergonomics. Springer-Verlag Berlin

Heidenlberg; 2011. p. 5229.

[9] Cronin G, Andrews S. After action reviews: a new model for learning. Emerg Nurse

2009;17(3):325.

[10] Bliss JP, Minnis SA, Wilkinson J, Mastaglio T, Barnett JS. Establishing an intellectual

and theoretical foundation for the after action review processa literature review.

US Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, Arlington,

Virginia. 2011.

[11] Mastaglio T, Wilkinson J, Jones PN, Bliss JP, Barnett JS. Current practice and

theoretical foundations of the after action review. Portsmouth, VA: NYMIC; 2011.

[12] Ramachandran S, Jensen R, Bascara O, Carpenter T, Denning T, Sucillon S. After

action review tools for team training with chat communications. The

interservice/industry training, simulation & education conference (I/ITSEC)

volume 2009.

[13] McCarthy ML, Brewster P, Hsu EB, Macintyre AG, Kelen GD. Consensus and tools

needed to measure health care emergency management capabilities. Disaster Med

Public Health Preparedness 2009;3(Suppl 1):S4551.

[14] Fidler DP. H1N1 after action review: learning from the unexpected, the success

and the fear. Future Mictobiol 2009;4(7):7679.

[15] Wilson K, Brownstein JS, Fidler DP. Strengthening the international health

regulations: lessons from the H1N1 pandemic. Health Policy Plan 2010;25:5059.

[16] Riba S, Reches H. When terror is routine: how Israeli nurses cope with multicasualty terror. Online J Issues Nurs 2002;7(3):6.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Data Management Plan Template He enDokumen6 halamanData Management Plan Template He eneftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- GeorgeDimitriu ClausewitzandthepoliticsofwarJSSDokumen43 halamanGeorgeDimitriu ClausewitzandthepoliticsofwarJSSeftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- Explained Risk AppetiteDokumen30 halamanExplained Risk Appetiteeftychidis100% (3)

- Project Info SheetDokumen2 halamanProject Info SheeteftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- Wildfires, Complexity, and Highly Optimized ToleranceDokumen6 halamanWildfires, Complexity, and Highly Optimized ToleranceeftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- RIMS Exploring Risk Appetite Risk Tolerance 0412Dokumen13 halamanRIMS Exploring Risk Appetite Risk Tolerance 0412Ștefan Dănilă Dacusorul100% (1)

- Coronavirus Case QuestionnaireDokumen7 halamanCoronavirus Case QuestionnaireeftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- Firehub Project Task 5 Interview ProtocolDokumen2 halamanFirehub Project Task 5 Interview ProtocoleftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- Rna VirusesDokumen27 halamanRna ViruseseftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- 2019 Ncov Factsheet PDFDokumen1 halaman2019 Ncov Factsheet PDFHarryBelum ada peringkat

- Swot Analysis StrategyDokumen24 halamanSwot Analysis StrategyeftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- Efi Policy Brief 4 enDokumen17 halamanEfi Policy Brief 4 eneftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- Medea BrochureDokumen8 halamanMedea BrochureeftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- Implications of Changing Climate For Global Wildland FireDokumen25 halamanImplications of Changing Climate For Global Wildland FireeftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- The Human Dimension of Fire Regimeson EarthDokumen14 halamanThe Human Dimension of Fire Regimeson EartheftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- UAS ServicesDokumen151 halamanUAS ServiceseftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- FIRE FIGHTING US SuppCostsDokumen1 halamanFIRE FIGHTING US SuppCostseftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- Thesis AndreasBachmann 2001Dokumen143 halamanThesis AndreasBachmann 2001eftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- Geyer - 3 Mar BriefingDokumen6 halamanGeyer - 3 Mar BriefingeftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- Eu 2015 444Dokumen36 halamanEu 2015 444juanBelum ada peringkat

- GFMC Greece Daily Beast 24 October 2018Dokumen4 halamanGFMC Greece Daily Beast 24 October 2018eftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- JRC Strategy 2030: From Data to Knowledge, from Knowledge to Policy/TITLEDokumen26 halamanJRC Strategy 2030: From Data to Knowledge, from Knowledge to Policy/TITLEeftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- Presentation CIP Forum 2018Dokumen16 halamanPresentation CIP Forum 2018eftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- Uavs and Ucavs in Eu - Wezeman PDFDokumen28 halamanUavs and Ucavs in Eu - Wezeman PDFeftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- Qualitative Evaluation-Chp 7Dokumen10 halamanQualitative Evaluation-Chp 7eftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- Alexander and Cruz 2014 FMTDokumen5 halamanAlexander and Cruz 2014 FMTeftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- Creating Performance Measures PDFDokumen160 halamanCreating Performance Measures PDFeftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- Resilience Profiles - One Approach Does Not Fit AllDokumen11 halamanResilience Profiles - One Approach Does Not Fit AlleftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- The Usage of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Their Prospects in Archaeology DNDokumen44 halamanThe Usage of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Their Prospects in Archaeology DNDomingo José Puerto PérezBelum ada peringkat

- Critical Infrastructures Risk ManagerDokumen14 halamanCritical Infrastructures Risk ManagereftychidisBelum ada peringkat

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Coronavirus Panic The Infectious MYTHDokumen25 halamanCoronavirus Panic The Infectious MYTHLouisa LivingstoneBelum ada peringkat

- Moral and Ethical IssuesDokumen16 halamanMoral and Ethical IssuesZunaira ArshadBelum ada peringkat

- Reflective StatementDokumen1 halamanReflective StatementTeodora M CalinBelum ada peringkat

- SCOPE and STANDARDSDokumen20 halamanSCOPE and STANDARDSCreciabullecerBelum ada peringkat

- Abnormal Psychology TestDokumen7 halamanAbnormal Psychology TestCamae Snyder GangcuangcoBelum ada peringkat

- Tuberculosis - A Re-Emerging DiseaseDokumen14 halamanTuberculosis - A Re-Emerging DiseaseTheop AyodeleBelum ada peringkat

- Job Responsibilities of Medical Officer and Other StaffDokumen18 halamanJob Responsibilities of Medical Officer and Other StaffAlpit Gandhi100% (4)

- Challanage Case in Autoimmune DiseaeDokumen349 halamanChallanage Case in Autoimmune DiseaeheshamBelum ada peringkat

- NBS for Haemoglobinopathies in Najran RegionDokumen17 halamanNBS for Haemoglobinopathies in Najran RegionSaifeldein ElimamBelum ada peringkat

- Textbook of Medical Parasitology Provides Comprehensive CoverageDokumen2 halamanTextbook of Medical Parasitology Provides Comprehensive CoverageAnge OuedraogoBelum ada peringkat

- 14 - DR. S.K Haldar MAHC 3Dokumen70 halaman14 - DR. S.K Haldar MAHC 3Ashan SanBelum ada peringkat

- IFIC BookDokumen392 halamanIFIC Bookzenagit123456Belum ada peringkat

- First Aid Basics Study Guide (AutoRecovered)Dokumen4 halamanFirst Aid Basics Study Guide (AutoRecovered)Reuben VarnerBelum ada peringkat

- Forensic Radiography White PaperfinDokumen38 halamanForensic Radiography White PaperfinMohy AbonohBelum ada peringkat

- Ultrasound TechnicianDokumen2 halamanUltrasound Technicianapi-76827299Belum ada peringkat

- Spectrum of Renal Parenchymal Diseases An Eleven YDokumen5 halamanSpectrum of Renal Parenchymal Diseases An Eleven YPir Mudassar Ali ShahBelum ada peringkat

- K 29 Sirkulasi Koroner - CVS K29Dokumen16 halamanK 29 Sirkulasi Koroner - CVS K29Jane Andrea Christiano DjianzonieBelum ada peringkat

- Agitated Behaviour Scale Form Modified-3Dokumen3 halamanAgitated Behaviour Scale Form Modified-3Gina PaolaBelum ada peringkat

- Cardiovascular HealthDokumen20 halamanCardiovascular HealthChrrieBelum ada peringkat

- On Cardio Respiratory ExerciseDokumen9 halamanOn Cardio Respiratory ExercisegomBelum ada peringkat

- TQM's Effect on Pharmacy AreasDokumen2 halamanTQM's Effect on Pharmacy AreasCrisamor Clarisa100% (1)

- An Interprofessional Web Based Teaching Module To.9Dokumen4 halamanAn Interprofessional Web Based Teaching Module To.9Em Wahyu ArBelum ada peringkat

- Mortality Toolkit PDFDokumen41 halamanMortality Toolkit PDFAhmedBelum ada peringkat

- SNB QuestionsDokumen7 halamanSNB Questionshardie himerBelum ada peringkat

- Counselling Course 2011Dokumen1 halamanCounselling Course 2011malaysianhospicecouncil6240Belum ada peringkat

- Quality of life and insomnia treatmentDokumen14 halamanQuality of life and insomnia treatmentAkhmad VauwazBelum ada peringkat

- Skizo JurnalDokumen7 halamanSkizo JurnalCikgu ZahranBelum ada peringkat

- Hemophilia: Factor IX (Hemophilia B)Dokumen38 halamanHemophilia: Factor IX (Hemophilia B)Jhvhjgj JhhgtyBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical Parasitology: 1. Direct Fecal Smear (DFS)Dokumen3 halamanClinical Parasitology: 1. Direct Fecal Smear (DFS)Monique Eloise GualizaBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing Home Lesson PlanDokumen3 halamanNursing Home Lesson Planapi-353697276100% (2)