2006 - Zarrillo and Kooyman - Evidence For Berry and Maize Processing

Diunggah oleh

Ann Oates LaffeyJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

2006 - Zarrillo and Kooyman - Evidence For Berry and Maize Processing

Diunggah oleh

Ann Oates LaffeyHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

See

discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271812819

Evidence for Berry and Maize Processing on the

Canadian Plains from Starch Grain Analysis

Article in American Antiquity July 2006

Impact Factor: 1.51 DOI: 10.2307/40035361

CITATIONS READS

37 54

2 authors, including:

Sonia Zarrillo

The University of Calgary

10 PUBLICATIONS 278 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Available from: Sonia Zarrillo

Retrieved on: 15 May 2016

Society for American Archaeology

Evidence for Berry and Maize Processing on the Canadian Plains from Starch Grain Analysis

Author(s): Sonia Zarrillo and Brian Kooyman

Source: American Antiquity, Vol. 71, No. 3 (Jul., 2006), pp. 473-499

Published by: Society for American Archaeology

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40035361 .

Accessed: 04/02/2015 19:47

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Society for American Archaeology is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

American Antiquity.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

EVIDENCE FOR BERRY AND MAIZE PROCESSING

ON THE CANADIAN PLAINS FROM STARCH GRAIN ANALYSIS

Sonia Zarrilloand Brian Kooyman

The ethnographicand ethnohistoricrecordsfrom the Northernand CanadianPlains indicate that a variety of plants were

utilizedbypast peoples. Theseaccountsprovide two importantinsights intoplant use in this regionwherevery little archae-

ological evidence existsfor plant utilization. First, plant processing tools are most likely to be unmodifiedlithic tools that

may escape our recognition.Second, a variety of plants, which can be identifiedvia starch grain analysis, were processed

with these tools. Thisproject analyzed the residuesfrom two unmodifiedlithic grinding tools, identifiedas possible plant

processing tools, for starch grains. Our results indicate that not only were a nuinberof wild plant species, such as choke

cherry(Prunusvirginianaj,saskatoonberry(Amelanchieralnifoliaj and likelyprairie turnipfPsoraleaesculenta),processed

with these implements,but so too was maize (Zea mays). These results not only provide importantinsight with respect to

identifyinga tool class, plant use, and trade within our study area, but also provide an exceptional window into the use of

wild plant species, an aspect of human history that is poorly understoodin many regions of the world in addition to the

NorthernPlains.

Los registrosetnogrdficosy etnohistoricosde las Planicies del norte, en Canaday los Estados Unidos, indicanque una gran

variedadde plantasfueron utilizadasen el pasado por los antiguospobladores. Estos registrosproveen dosfuentes impor-

tantesde informacionsobre la utilizacionde plantas en dicha region,en donde la evidenciaarqueoldgicadisponiblesobre la

antigua utilizacionde plantas es aun limitada.En primer lugar, las herramientaspara procesamientode plantas aparentan

ser herramientasliticas sin modificacionculturalque pueden escapar a nuestroreconocimiento.En segundo lugar,una var-

iedad de plantasfueron procesadaspor impactomecdnico, ofriccidn y presidn fmoliendajcon estas herramientas.En este

proyectose analizaronlos residuosde almidonlocalizadosen dos supuestasherramientasde molienda- sin modificacioncul-

tural- con el objetivode determinarsi los posibles restos de almidonindicabanque las herramientashabian sido utilizadas

para el procesamientode plantas. Nuestrosresultadosindicanque no unicamenteestos implementosse usaronpara procesar

un importantenumerode especies de plantas silvestres, tales como el "chokecherry" (Primusvirginiana),el "saskatoon"

(Amelanchieralnifoliajy el "prairieturnip"(Psoraleaesculenta),sino tambienplantas como el maiz (Zea.mays). La identi-

ficacidn de las especies de plantas silvestresno es sorprendentesi se considerala informacionque se localiza en los registros

etnogrdficosy etnohistoricosde la region, los cuales documentanque las herramientasliticas sin modificacionesculturales

fueron usadaspara procesar moras y tuberculosde tales especies. La presencia de maiz tampocoes sorprendentey su hal-

lazgo se ha interpretadocomo el resultadodel intercambioo comercio en la region,ya que esta planta no se cultivd en la

epoca previa al contacto europeo.El registroarqueoldgicomuestraque el comerciointerregionalde tipos liticos exoticos se

remontaa miles de anos e indicapatrones de interaccidnculturalde larga duracidn.En elperiodo del contacto Europeose

ha documentadoampliamenteque el maizfueproducto de intercambiopor carne de bisonte entre las aldeas de horticultores

de la regionmeridionalde Missouriy las tribusndmadasde las Planicies, unpatron de intercambioque aparentementepudo

haber existidoantes del contactoEuropeo.El andlisis de residuosde granos de almidonfue instrumentalya que identifiedla

funcidn de estas herramientasliticas sin modificacioncultural.Estos resultadosno solo proveen importanteinformacioncon

respectoa la identificacidnde diferentesclases de herramientas.El uso de diferentesplantas y el patron de intercambioen

nuestraarea de estudio,sino que ademdspueden considerarseun recursoexcepcionalpara inspeccionarel uso de plantas sil-

vestres,un aspecto de la historia humanaque esta deficientementeestudiadaen muchasregionesdel mundo,no unicamente

en las Planicies del Norte.

collection and processingof plantsfor the image of the bison is consideredsynonymous

food, medicine,items of materialculture, withthePlainsculturalregion.Plantswerealsocrit-

and spiritualpurposesis often overshad- ical in the lives of the past CanadianPlainspeo-

owed in CanadianPlainsliteratureby referenceto ples, yet littleresearchhas been conductedhereto

thebisonas thechief sourceof subsistence.Indeed, recoverdirectevidenceof plantuse fromitems of

Sonia Zarrillo and Brian Kooyman Departmentof Archaeology,Universityof Calgary,Calgary,AB CanadaT2N 1N4

(szarrillo@gmail.comand bkooyman@ucalgary.ca)

AmericanAntiquity,71(3), 2006, pp. 473-499

Copyright2006 by the Society for AmericanArchaeology

473

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

474 AMERICAN ANTIQUITY [Vol. 71 , No. 3, 2006

Figure 1. Locations of sites mentioned in the text (1) EgPn-612, (2) Tuscany, (3) Boss Hill, (4) Cluny, (5) Morkin, (6)

Oldman Dam sites, (7) Gowan, (8) Lockport East, (9) Hagen, (10) Barton Gulch, (11) Leigh Cave.

materialcultureused in the processing of plant 1994:25). The present study was undertakento

matter,suchas grindingslabsandgrindingpebbles. examine the potential for identifying plant pro-

This is due in partto the fact thatformalgrinding cessing implementson the AlbertaPlains.

stonesarealmostunknownon the CanadianPlains Duringthe ethnohistoricperiodon the North-

(Dyck 1983:129;DyckandMorlan2001:118, 130; ernPlainsgrindingstoneswere employedin a rel-

Forbis 1992:31; Frison 1991:114; Johnson and ativelyrestrictedrangeof activities.For the most

Johnson1998:218,222, 224;WormingtonandFor- parttheywereusedforpoundingratherthan"grind-

bis 1965:192;Wright1999:797,799, 806), with a ing"in thesensewe usuallyemploytheterm.Many

conspicuousexceptionin the case of the Lockport accountsfromthisperiodmentiontheuse of stones

East site, EaLf-1 (Figure 1), in Manitoba(Bryan to pounddriedmeat in preparationof pemmican

1991:153-154;Flynnand Syms 1996:7-8; Walde (e.g., Denig 1961:12;Wissler 1986:22-23). Simi-

et al. 1995:40).This is particularlytruein ourspe- larly,therearea numberof recordsof using stones

cific study area,Alberta,where true well-shaped to pound berries or dried berries (e.g., Lowie

metatesand manos are absentexcept for a single 1922:214), these pounded berries then dried as

example from a privatecollection (Wormington cakes (e.g., Wissler 1986:21) or incorporatedin

and Forbis 1965:129).Even less formalgrinding pemmican(e.g., Denig 1961:12;Wissler1986:21).

stones are rare,apparentlyknown only from the Dried, poundedroots were sometimes added to

Cluny (EePf-1) and Morkin (DlPk-2) sites in soupsor stews,in partas thickeningagentsbutalso

Alberta(Forbis1977:60-63,74;Vickers1986:106; clearlyfortheirfood value(e.g., Wissler1986:22).

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Zarillo and Kooyman] EVIDENCE FOR BERRY AND MAIZEPROCESSING 475

Figure 2. T'suu Tina woman, Mrs. Old Man Spotted, pounding choke cherries with unmodified lithic tools (Glenbow

Archives NA-667-486).

Finally,a numberof medicinalplants,again par- bow photograph(Figure 2) dating to the 1930s

ticularly dried roots, were powdered by stone shows a different T'suu Tina woman pounding

implementswith the powder administeredas an choke cherries with unmodified stones. Lowie

infusion(e.g., Peacock 1993:126). (1922:214) notes thatfor pounding"cherries"the

Poundingstones can have fewer requirements Crowused an unmodifiedflat slab for the base, or

in termsof overallformcomparedwithstonesused sometimesa mortar,anda pestle-shapedhammer-

to grindgrainsor maize to produceflour.Wissler stone. Well-formedconical pestles, used with a

(1986:22-23) describes dried meat as being largeflatstonebasewitha small,deep,close-fitting

poundedforpemmicanusinga "flatrock"as a base mortar-likedepressionworkedin the centreof the

and poundingwith a grooved maul (sometimes basal slab, are known from the Plateau area of

recycled from older settlements) encased in BritishColumbia(Figure3). Conversely,to pound

shrunkenrawhideor a "pestle."He notes "wild driedmeatforpemmicantheKutenai(Turney-High

cherries"as being pounded(fruitand pits) "on a 1974:38)used a flatrockcoveredwith a soft piece

stone" with the same grooved maul (1986:21). of tannedhide and a stone maulin a mannersim-

Morerecently,one of Peacock's(1993:58) Black- ilarto theBlackfootas describedby Wissler.Over-

foot informantsalso noted choke cherries were all, then, the indications for the Northern and

pounded, pits and fruit together, using totally CanadianPlains are that grinding or pounding

unmodifiedimplements:"a flat rock and then a implementsarelikelyto be unmodifiedstones,par-

smallerrock."A Glenbow Archives photograph ticularlyin southernAlberta.This conformsto the

(NA-667-71)showsjust such a use of unmodified patternseenarchaeologically. Itis verypossiblethat

lithic pieces to pounddriedmeat, in this instance thereasontherearefew of thesegrindingorpound-

by a T'suu Tina woman in the 1920s. Dempsey ing implementsin CanadianPlainssites is thatwe

(2001:630)showsa similarview wherechokecher- havefailedto recognizethem.Theyareessentially

ries are being addedto the meat.1AnotherGlen- unmodified. If culturally modified implements

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

476 AMERICAN ANTIQUITY [Vol. 71 , No. 3, 2006

Figure 3. Interior British Columbia lithic mortar and pestle style cherry pounding implements (Glenbow Archive NA-

2244-27).

mationon only a few of theplantspeciesused,and

were used in the past,the most probablemodified

implementwouldhavebeen a groovedstonemaul on evenfewerthatwereprocessedwithlithictools.

Oursurveyis focusedon Blackfootplantuse as the

for the hand stone. These are, in fact, well docu-

mented in Canadian Plains' sites (e.g., Dyck regionally most relevant source (e.g., Peacock

1983:97;Wormingtonand Forbis 1965:108) and 1993). Regardless,this informationcan only pro-

therearea few conicalpestlesknownfromprivate vide a generalbasisforassessmentandotherplants

will be assessed in futurework. Binomial names

surfacecollections (e.g., Wormingtonand Forbis

of plantspecies follow Moss (1994) andare spec-

1965:108, 129).To advancestudiesin this areawe

ifiedwiththecommonnamesin thetextwhenthey

requireanindependentmethodof identifyinglithic

firstappear,with commonnamesused thereafter.

plantprocessingtools thatareunmodifiedor that,

like grooved mauls, might be assumed to have Themostcommonplantprocessingusinglithic

served other functions. Microbotanicalresiduetools in thisareawas forpoundingberriesandsim-

ilar fruitsto add to pemmicanor to dry as cakes.

analysishas excellentpotentialto fill this role. In

Thesefruitsarecommonlyreferredto as "cherries"

thispaperwe examinethe potentialof starchgrain

(Lowie 1922:214),whichprobablyincludedchoke

analysisas anindependentmethodto identifylithic

plantprocessingtools. cherries(Prunusvirginiana)(Denig 1961:11-12;

Hoebel 1960:60, Mandelbaum1979:75; Wissler

Ethnohistoric Plant Use 1986:20-22) andsaskatoons{Amelanchieralnifo-

on the Alberta Plains lia) (Dempsey 2001:607, Peacock 1993:130) or

serviceberries{Amelanchierspp.)butperhapsalso

Regionalethnographies and ethnobotanical

stud- pin cherries{Prunuspensylvanica).There are a

ies were examined to provide a frameworkfor numberof examples where the poundingimple-

understanding which plants might have been ments are not specificallystatedto be lithic (e.g.,

processedusinggrindingorpoundinglithicimple- Dempsey 2001:607;DeMallie 2001:804, both for

ments.Most ethnographicsketchesprovideinfor- choke cherries) and others where the pounding

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Zarillo and Kooyman] EVIDENCE FOR BERRY AND MAIZEPROCESSING 477

implementmaterialis not specifiedand the fruits use among the Cheyenne and Denig (1961:11)

are simply termed "berries"without any further notes grindingof this root for food. Mandelbaum

identification(e.g., FowlerandFlannery2001:680; (1979:74) notes thatthe Plains Cree placed dried

Voget 2001:696). Kidd (1986:114) statesthatthe prairieturniproots in rawhideand poundedthem

Blackfoot also treatedrose hips (Rosa spp.) by with a stone maul. Peacock notes thatthe Black-

crushingthem,mixing themwith fat androasting foot groundbalsamroot(Balsamorhizasagittata)

them,althoughhe does not stateif lithictools were roots and sometimescamas (Camassiaquamash)

used in the crushing.Peacockalso cites one of her bulbsin preparationas food (1993:144, 148-149).

informantsas indicatingthatrosehipswerecrushed Voget remarksthat one of the items the Crow

andmadeintocakeslikechokecherries(1993:225). obtainedin tradefrom more westernpeoples was

These plants all belong to the rose family "root flour"(2001:696) and Turney-Highnotes

(Rosaceae). specificallythatthe Kutenai,unlike some of their

In additionto the aboveberries,Peacocknotes neighbors,did not grindbitter-root(Lewisiaspp.)

thatbearberries (Arctostaphylosuva-ursi)mayhave intoflourto consumeit ( 1974:33). Cattailrhizomes

been crushedwith a grindingstone and addedto (Typhalatifolia) were dried and groundto make

pemmicanby the Blackfoot(1993:137). She also flourby someCreegroups(Marieset al. 2000:297).

notes that other groups mashed black mountain Manymedicinalplants,particularlyroots,were

huckleberry (tall bilberry; Vaccinium mem- groundin preparation foruse.Thespecificsof such

branaceum)to form cakes for storage, and the preparation rarelynotedoutsidededicatedeth-

are

Blackfootmay have as well since they also col- nobotanicalstudies(e.g., Marieset al. 2000; Pea-

lectedit (1993:241).Mandelbaum(1979:75)seems cock 1993; Siegfried1995), and even in these the

to indicatethata largenumberof berriesweredried details are often omittedsince this knowledgeis

and then crushedfor storageby the Plains Cree. notusuallyconsideredappropriate forgeneralaudi-

The wording is unclear, but this might include ences. Forthe presentstudywe havereliedon two

saskatoons,raspberries(Rubusspp.), strawberries recent ethnobotanical studies (Peacock 1993;

(Fragaria spp.), black currents(Ribes hudsoni- Siegfried1995) undertakenin Alberta,one specif-

anum), red osier dogwood berries (Cornus ically on the Blackfootandso most appropriateas

stolonifera),gooseberries(Ribesspp.),pincherries, a model in the presentinstance.Both have drawn

high bush (Viburnumopulus)and low bush (Vac- on otherliteraturewhere it is appropriateand so

cinium vitis-idaea) cranberries, mooseberries provide more inclusive coverage. Preparationof

{Viburnumedule), blueberries(Vacciniumspp.), these plants was probablya much less common

snowberries (Symphoricarpos albus), and eventthanwas the case for berriesandrootsused

mountain-ash berries (Sorbus americana). as food; hence the likelihoodof findingevidence

Siegfriednoted, for WoodlandCree people, that of theiruse is small.Basedon Peacock'sBlackfoot

blueberries,saskatoons, bearberries,and choke informants(1993:73), medicinalplant pounding

cherriesmightbe mashedor poundedin process- orgrindingwas normallyundertakenusinga cylin-

ing (theimplementsused arenot specified),in the dricalor elongaterivercobble as the hand stone.

case of the bearberriesand choke cherriesthese Peacocknotes the Blackfootas preparingthe fol-

being mixed with fish eggs (1995:113, 230, 233, lowingmedicinalplantrootsby grindingorpound-

287). She also noted that Canadabuffaloberries ing in some manner:baneberry(Actaea rubra),

(Shepherdiacanadensis)mightbe crushedbefore angelica(Angelicadawsonii),and/orsweet cicely

being whippedinto "Indianice-cream,"although (Osmorhizaoccidentalis)(thereis some confusion

again the means for accomplishingthis was not in the literature)(1993:126, 134, 200); greenmilk-

specified(1995:302-303). weed (Asclepiasviridflora)(1993:141);horsetails

Grindingof plantrootsforfood is less well doc- (Equisetumspp.) (1993:162);old man'swhiskers

umentedin the literature.Wissler(1986:22) notes (Geumtriflorum)(1993:167); wild licorice (Gly-

thatprairieturnip(Indianbreadroot,Psoraleaescu- cyrrhizalepidota)(1993:168);alumroot(Heuchera

lenta) was driedand then groundfinely and used spp.),specificallywitha grindingstoneanda piece

as a soup thickening by the Blackfoot. Hoebel of canvas(1993:173);skeletonweed (Lygodesmea

(1960:59-60) documentsexactlythis processand juncea) roots and stems (1993:191); double

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

478 AMERICANANTIQUITY [Vol. 71 , No. 3, 2006

bladder-pod(Physariadidymocarpa)(1993:206); existence of Plains trade from very early times.

valeriana,again with a stone and piece of canvas Thistradeextendedto theeastcoastof NorthAmer-

orhide{Valerianaspp.)(1993:243);andeitherbear ica andwest intotheRockyMountains(Boszhardt

grass (Xerophyllumtenax) or Spanish bayonet 1998;Gregg1994:76;StoltmanandHughes2004;

{Yucca glauca) (1993:246-248). Siegfried Winham and Calabrese 1998:296-297). These

(1995:226)statessweet flag {Acorusamericanus) lines of evidence suggest it is possible that the

was "shredded" whenusedformedicinalpurposes. grindingstonesconsideredin this papermay have

Siegfried also statedthatthe barkof redosierdog- beenusedto processtradedmaize.Itis useful,then,

wood was sometimespulverizedand mixed with to examinewhatthe probabilityis of maize being

tobaccoto smoke (1995:246). tradedthis far west andnorth.

Consideringthe varioussourcesof information A well-establishedtradingframeworkexisted

andthefrequencywithwhichparticularspeciesare on the Plains and furtherwest priorto European

represented,particularlywith regards to those contact.The tradingnetworkhad a numberof pri-

plants also specifically used traditionallyby the mary and secondarycenters stretchingfrom the

Blackfoot,the two most likely plantsto be repre- westcoastto theeasternmarginof thePlains(Wood

sented in archaeologicalcontexts in Alberta are 1980:101). One of the majorcenters was in the

chokecherriesandprairieturnips.Saskatoons,rose MiddleMissouri,in the Hidatsaand Mandanvil-

hips,andbearberries arethenextmostlikely.Again, lages, and it is the one relevantin the presentdis-

however,these are only the most likely and cer- cussion. The trade system persisted until about

tainlyotherspeciescannotbe eliminatedfromcon- 1850 whenit was disruptedby the furtrade(Wood

sideration. 1980:100).It is well documentedby theLewis and

Clarkexpedition(1804-1806) and the role of the

HidatsaandMandanvillagesis documentedby La

Assessing the Potential

for the Presence of Maize Verendryeas earlyas 1733whenhe mentionedthe

Cree andAssiniboineleavingfor the Mandanvil-

Throughoutthe Americasthe most common and lagesto tradeformaize(Milloy1988:43).TheMid-

widespreaduse of grindingstoneswasundoubtedly dle Missouritradewas between the horticultural

for preparationof maize by grindingor milling tribesof the MiddleMissouri- Hidatsa,Mandan,

(Gremillion2004:221) to producemeal, grits, or Arikara- and the nomadic tribes, with these

flour.Maize horticulturewas not practicedin the nomadicpeoplecomingto the semi-sedentaryvil-

westernportionof the CanadianPlains, although lages on the Missourito trade.

thereis archaeologicalevidence, some of it very A varietyof goods wereexchangedin theMan-

limited,for it in Manitoba(Buchner1988; Carter dan and Hidatsavillages in both individualand

1990:38-39; Gregg 1994:91; Nicholson 1990; larger group ceremonial exchanges (Milloy

Waldeet al. 1995:40).Thereare some recordsof 1988:48-51;Wood1980:100).Themostimportant

horticulture;perhapsthe resultof influencefrom exchangeswereof fooditems(Blakesee1978:140).

Europeansor First Nations groupsfrom Ontario For the nomadicbison huntinggroupsmaize was

(Carter1990:39-41;MoodieandKaye 1969),dur- particularlyimportant,probablyboth before and

ing the 1800sbutthe only Europeanrecordindica- afterthe arrivalof Europeans:"Cornwas an ideal,

tive of pre-Europeanhorticultureon the more portablefood supply for winter huntingexpedi-

western CanadianPlains is Matthew Cocking's tions andfor the long-distancetravelthatCreeand

1772mentionof a fieldof plantedtobaccoin west- Assiniboin middlemenwere involved in. It, like

ern Saskatchewan(Carter1990:39).A numberof pemmican,was an importanttool in the prosecu-

studieshave documenteda well-developedPlains tionof thenativefurtrade"(Milloy 1988:43).Trade

tradingnetworkbefore and duringthe European becamesufficientlyimportantto boththe horticul-

contactperiod(Blakeslee1978;Ewers1954, 1955, turaland nomadicgroupsthateach intensifiedits

1968; Hanson 1987; Jablow 1950; Milloy 1988; productionand became more specialized in the

Wood 1980;WoodandThiessen 1985). Nonlocal food items produced.The nomadicgroupsinten-

lithicandshellpieces in Plainsarchaeologicalcon- sified bison productionefforts(mainlymeat) and

texts from Paleoindiantimes onwardattestto the the horticulturalgroups intensifiedhorticultural

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Zarillo and Kooyman] EVIDENCE FOR BERRY AND MAIZEPROCESSING 479

productionandincreasinglyspentless timein hunt- inhabitantswere likely Hidatsa,Crow,or a related

ing (Hanson 1987:39). The tradingsystem also people (1977:73). Kooyman(1996:18) favoreda

likely functionedto overcometimes of scarcityin MountainCrow or Hidatsaaffiliationfor Cluny

one of the two mainPlainssubsistenceresources, based on a varietyof lines of evidence (the Crow

bisonandhorticulture,by encouragingproduction areclosely relatedto the Hidatsabasedon linguis-

of a surplusof one set of resourcesbeyond local tics and oral tradition [Ahler and Swenson

needs that could be "shared"should the other 1993:122-123;Bowers 1965:10-25]).

resourcesufferlow productivityin a particularyear Although these lines of evidence are meager

(Blakesee 1978:140-141; Hanson 1987:19-20, and the degreeto which they can be extrapolated

39-40; Wood 1980:103). into earlierperiodsis not clear,thereis reasonable

Althoughmanynomadicgroupstradeddirectly evidencethatduringthe periodof Europeancon-

with the HidatsaandMandanvillages, the Black- tactandperhapssomewhatbeforethatbothAssini-

foot werenot amongthemin the Europeancontact boine andCrowpeoplemayhavebeenin southern

period(Milloy 1988:43,48-49; Wood 1980:100). Albertaandmighthavebroughttradedmaizethere.

Anytradegoodsthatwouldhavereachedthewest- Maize may havebeen tradedinto the areaas well,

ernportionof the NorthernPlainsprobablydid so withoutthe directincursionof Crow,Assiniboine,

via the Cree,Assiniboine,or Crow.These groups orCreepeople.Widespreadandmoreancienttrade

tradeddirectlyin the villages andwere amongthe specificallywith the MiddleMissouriareais seen

main nomadic group traders(Hanson 1987:38). in the presenceof Knife River Flint from North

Fromat least 1754 boththe Cree andAssiniboine Dakota west into Saskatchewan, Alberta, and

utilizedwhatwaslikelyBlackfootterritory between Wyomingas early as Cody Complextimes (e.g.,

Edmonton and Red Deer based on Henday's Dyck 1983:115;Frison1991:66;Gruhn1969:142;

account(Russell1991:142-146, 179-181) andthe Tolman2003:107;Walde2003:54-57; andWright

Assiniboine and Cree also occupied portionsof 1995:299, 1999:789,824).

southernSaskatchewan(1991:136-138, 184).The Maize was probablytradedas dried kernels,

Blackfoot tradedwith the Assiniboine and Cree since that is how it was generally stored on the

about 1730, perhapsearlier(Milloy 1988:24-25; Missouri(Wilson 1977:90-92). That said, maize

Smyth1992:344).Milloy(1988:24-25)claimsthat as hominy,meal, or meal cakes was preparedfor

the Blackfootwere allies of the Cree andAssini- use in long-distance voyaging, as for example

boine at this time, which would have facilitated amongtheIroquoisandOsage(Blake2001:55-56).

trade, but Smyth (1992:344-347) refutes this In historicrecordstradedmaize is referredto as

notion.Regardless,by theearly1800sanyalliance "grain"oras a numberof "bushels,"butnotas flour

hadfalteredandtheBlackfoothadbecomeenemies or meal, andto at least a limitedextentas kernels

of the CreeandAssiniboine(Milloy 1988:31-36). driedon thecob (Hanson1987:26;Milloy 1988:48,

Walde (2003; Walde and Meyer 2003:144-148; 53; Wilson 1977:58; Wood and Thiessen

Waldeet al. 1995:9-50) has assembledevidence 1985:153).Tradingmaize as driedkernelsis logi-

suggestiveof anearlypresenceof Assiniboinepeo- cal since obviouslyit is lighterandless bulkythan

ple west intoAlbertaandthe modernStoneypeo- cob maizeandmilledmaizeis moredifficultto pro-

ple of Alberta are very closely related to the tect fromspoilageandloss, bothsignificantissues

Assiniboine(e.g. the Stoneylanguageis anAssini- for nomadicpeople.

boinedialect).Movementof MiddleMissouripeo-

ple northwest toward southern Alberta and Archaeological Data for Plant Use

Saskatchewanis seen archaeologicallyin the for-

tified sites at Hagen (24DW2) in northeastMon- There is relativelylittle archaeologicalevidence

tana(Mulloy 1976) andClunyin southernAlberta fromtheCanadianPlainsforplantuse.Earlymate-

(Forbis 1977). Forbis (1977:11) cited a tradition rial is controversial but includes goosefoot

recountedby One Gun indicatingthat the Cluny (Chenopodium)seedsattheGowansite (FaNq-25)

site was one of severalshortoccupationsites of a in centralSaskatchewanand choke cherryseeds

groupof people who were relatedto the Crowbut from Boss Hill (FdPe-4)in centralAlberta.Boss

that were not Crow. It was his opinion that the Hill alsohadtwopiecesof sandstonethatmayhave

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

480 AMERICANANTIQUITY [Vol. 71 , No. 3, 2006

beengrindingstones(DyckandMorlan2001:118). Smith (1988:145) examineda numberof sites

A preliminaryreporton flotationof 31 sediment in southwestWyomingand found that goosefoot

samplesfrom eight archaeologicalsites from the seeds (Chenopodiumand Monolepsisspp.) were

Oldman Dam (DjPm-116, DjPm-36, DjPm-80, clearlymost abundant.Also commonwere choke

DjPm-100,DjPm-115,DjPm-122,DjPl-11,DjPl- cherry,saltbush(Atriplexspp.), and species from

13) projectin southwestAlbertarecoveredmainly the mustard family (Cruciferae), but grasses,

goosefoot (Chenopodium spp.) seeds as well sedges,anda varietyof otherplantsincludingsun-

(Vance 1992). Goosefoot was also the most fre- flower and rose were also present. Frison

quentseedrecoveredin floatationsamplesfromthe (2001:138, 1991:338-339)listsprobablefoodplant

LockportEastsite (EaLf-1) in Manitoba,buta vari- remains from Leigh Cave (48WA304) in the

ety of other local wild plants, such as hazelnut foothillsof the BighornMountainsin Wyomingas

(Corylusamericana),wild cherry(Prunusspp.), including wild onion (Allium spp.), silver buf-

raspberry,strawberry, andwild rose werealso pre- faloberry(Shepherdiaargentea),pricklypearcac-

sent.The only cultigenrecoveredat LockportEast tus,chokecherry,juniper,limberpine,yucca,wild

was Zea mays in the form of charredkernelsand rose, andgrass.

cupules,identifiedas NorthernFlintmaize.Maize Not all of thesearchaeologicalplantremainsare

wasrecoveredfromtwohearths,a basin-shapedpit, of species likely to be processedwith grindingor

two bell-shapedpits,andanorganiclayerandnon- poundingstones,butmanymightbe basedon evi-

featuresamplesdatingto betweenA.D. 1200 and dence from easternNorthAmericaand from the

1500 (Deck and Shay 1992:38). ethnobotanicalliteraturealreadycited:goosefoot,

At the Tuscany site (EgPn-377) in Calgary chokecherry,buffaloberry, rose,juniper,sunflower,

Siegfried found significant numbers of juniper limber pine, bearberry,and perhapsbuckbrush,

seeds (Juniperusspp.),bearberryseeds, goosefoot baneberry,andgrasses.

seeds,roseseeds,andspruce(Picea spp.)seedsand Basedon theethnobotanical,ethnohistoric,and

cone scales (2003:148-163). Uncommon seed archaeologicalevidence discussedabove the fol-

speciesincludedbuckbrush(Symphoricarpos occi- lowingplantspecieswerechosento investigatevia

dentalis),Canadabuffaloberry,and westernwild starchgrainresearch:choke cherry,prairieturnip,

bergamot(Monardafistulosa) (2003:165-168). saskatoon,rose hip, bearberry,and maize. Addi-

Siegfriedalsotentativelyidentifiedshrubbycinque- tional species were also investigatedbecause of

foil (Potentillafruiticosa),

northernbedstraw(Gal- theirclose relationshipto these species in orderto

ium boreale),Indianpaintbrush(Castillejaspp.), determineif starchgrainform was distinctiveof

and baneberry(2003:169-171). These seeds are thetargetspecies,andto morebroadlydefinestarch

all derived from the general site sediments and grainformin this areaof NorthAmericawhereno

hence it is not certainwhetherthey representcul- priorworkhas been undertaken.

turaluse or the site vegetationbefore or afterthe

site was occupied. Nature of the Study Sample

TheBartonGulchsite (24MA171)in southwest

Montanais theearliestNorthwestPlainssite (9410 Duringa heritageresourceimpactassessmentcon-

60 B.P. [Frison 1991:27]) with good paleob- ductedat the locationof a futureresidentialdevel-

otanical evidence. Results mainly from roasting opment,two cairnswerediscovered,one of which

pits were dominated by slimleaf goosefoot resultedin the recoveryof two possible grinding

(Chenopodium leptophyllum)andpricklypearcac- tools- a siltstonegrindingpebble and a siltstone

tus (Opuntia polyacantha) seeds (Armstrong grindingslab(Figure4). Theseidentificationswere

1993:13). Sedges (Carex spp.), scarlet mallow based on macroscopicallyvisible striationsand

(Sphaeralceacoccinea), and a numberof grass thusthese artifactsprovidedan excellentopportu-

species (Gramineae)were also present.Interest- nity to test whetherresidueanalysiscould help to

ingly,rarebutalso representedwereredosierdog- determineif thesetoolshada plantprocessingfunc-

wood, sunflower(Helianthusspp.), limber pine tion,informationthatwouldotherwisenotbe forth-

(Pinusflexis), choke cherry,wild rose, raspberry, coming by conventionalanalysisalone.

andblueberry. The site (EgPn-612)is located withinthe city

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Zarillo and Kooyman] EVIDENCE FOR BERRY AND MAIZEPROCESSING 481

Figure 4. Unmodified grinding slab and grinding pebble from EgPn-612.

of Calgary,Albertaon a terracewith a southeast and all indicationsare thatthey areboth contem-

exposureoverlookingnaturaldrainagechannelsof poraneous and associated. No buried soil was

the Elbow River,which is locatedthreekm to the encounteredbeneaththe cairnrocks (Ramsayand

south(RamsayandRamsay2001:3).Theparcelof Ramsay 2001:14), thereforesuggesting the cul-

land where the site is situated has never been turalmaterialmay have been placed in a pit fea-

plowed and the currentvegetationincludesmany tureand subsequentlycoveredby the cairnrocks.

plantswithedibleandusefulberriessuchas choke A 5-10 cm soil A horizon(Ramsayand Ramsay

cherry,saskatoon,redraspberry, gooseberry,black 2001:15) developedandsubsequentlycoveredthe

currant,and wild rose. Native fescue is found on basalportionof bothcairns,indicatinga periodof

the slopesof theterracewhile thetop of the terrace perhapsa few hundredyearshadelapsedsince the

is predominantlyundisturbedaspen and shrubs cairns were abandoned.The grindingtools were

(RamsayandRamsay2001:3).Althoughno diag- recovered from below the A horizon and cairn

nosticprojectilepointswererecoveredas a means rocks.Further,lichencoveredtheexposedsurfaces

to datethetools,theyarethoughtto dateto thepre- of the rocksof bothpartiallyburiedcairnsindicat-

Europeancontactperiodas no Europeanartifacts ing thatthe rockshadbeen lying in thosepositions

such as tradebeads were found. The absence of for some time (Ramsayand Ramsay2001:11). A

Europeantradegoods is not certainevidence of a flakestonetool thatshowedno evidenceof usewear

pre-European ageforthesite,particularlyinAlberta was recoveredfrom the same depthas the grind-

whereEuropeangoods areuncommonin sites that ing tools underan adjacentcairn,also supporting

predate the establishment of fur trade posts in a pre-European contactdate.Inadditionto themar-

Alberta(Pyszczysk 1997). ginally retouched flaked stone tool mentioned

However,evidencefor a pre-Europeanage for above,the only otherartifactsrecoveredfromthe

the site does exist. The tools were recoveredfrom cairnsconsistedof quartzitecoresanddebitage.Six

undisturbedcontextsin the same excavationunit cores and 30 pieces of debitagewere recoveredin

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

482 AMERICAN ANTIQUITY [Vol. 71 , No. 3, 2006

Figure 5. Close-up of usewear striations on EgPn-612 grinding slab.

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Zarillo and Kooyman] EVIDENCE FOR BERRY AND MAIZEPROCESSING 483

Figure 6. EgPn-612 grinding pebble showing pitting on flat end of pebble.

totalfrombothcairns.While some lithicreduction stonesor otherfruitscontainingwoody seeds. Ini-

occurredat the site it was clearly not the prime tially two plantspecies were tentativelyidentified

activity. from the numerousstarchgrains in the residues

Usewearanalysiswas originallyperformedon extractedfromthese tools- chokecherry(Prunus

thesetoolsby theconsultantarchaeologistsrespon- virginiana)andsaskatoonberry{Amelanchier alni-

sible for the heritageresourceimpactassessment folia). Furtheranalysiswas then conductedin an

(Ramsayand Ramsay2001) and by Zarrillosub- attemptto confirmthese findingsand to identify

sequent to conductingthe residue analysis. The moreof the starchgrainsrecoveredin the residues

resultsof the usewearanalyseson the tools were by expandingthe starchgraincomparativecollec-

indicativeof plant processing.Both the grinding tion to includemore species.

pebbleandgrindingslabshowlinearstriationspar-

allel to the long axis of the tools (Figure5), con- Starch Grain Analysis

sistentwith long grindingand rubbingactions as

would be expected with the grinding of seeds, Starchgrainanalysishas been used by numerous

berries,andevenmaize.Inparticular, pitting/peck- researchersto study diet, plant processing,plant

ing observedon the flat end of the grindingpeb- domestication and cultivation, tool use, and in

ble, as shownin Figure6, may be consistentwith ceramicresidue analysis (e.g., Babot and Apella

crackingopenandcrushing/pounding chokecherry 2003; Bartonet al. 1998;FullagerandField 1997;

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

484 AMERICANANTIQUITY [Vol. 71 , No. 3, 2006

Fullageret al. 1998; Horrockset al. 2004; Iriarte landscapesuitablefor trappingstarchgrains.

et al. 2004; Loy et al. 1992; Parr2002; Pearsall

StarchGrainRecoveryand Analysis Methods

2003; Pearsallet al. 2004; Perry2001, 2002, 2004;

Piperno and Hoist 1998; Piperno et al. 2000; The tools testedhad been washedpriorto testing

Piperno et al. 2004; Simons 2001; Ugent et al. as partof the basic cataloguingprocedure.While

1984; Zarrillo2004a). It has also been employed ideallyunwashedartifactsarepreferredforresidue

in environmentalreconstruction,landuse studies, analysis,washingdoes notprecludethe successful

andin the identificationof site activityareas(e.g., recoveryof starchgrainsfrom stone tool residues

Balme andBeck 2002; Lentferet al. 2002; Therm (Loy 1994:96; Piperno and Hoist 1998:772). It

et al. 1999). Storagestarchgrains,formedin amy- shouldalso be notedthatpowderedgloves (which

loplasts,are the chief long-termstoragepolysac- containcornstarch)werenotused at anytimedur-

charideof higherplantsandarefoundin specialized ing thehandlingof the tools. Residueswererecov-

plant storage areas such as undergroundstems, ered from the surfacesof the grindingstone tools

roots,fruits,andthe endospermandcotyledonsof by a multiple-stepmethodthatinvolvedsoakingthe

seeds (Banks and Greenwood 1975:1; Haslam utilized tool surfacesto loosen residues,using a

2004:1716; James et al. 1985:162). In contrast, centrifugeto concentratethe residues, and then

transitorystarchis located in the chloroplastsof transferringthe residuesto microscopeslides with

leaves andgreenstems andacts as a readilyavail- Pasteurpipetteswhere they were allowed to dry

able energy source for plants (Banks and Green- priorto mountingundercoverslips.2Residueswere

wood 1975:1; Haslam 2004:1716; James et al. mountedin a 50:50 solutionof glycerine-waterto

1985:162). Distinctivefeaturesof storage starch enablerotationof the starchgrainsduringmicro-

grainsare geneticallycontrolledand, when care- scopic analysis, as recommended by other

fully observed,can be used to identifyplanttaxa researchers (MacMasters 1964:234; Perry

(Banks and Greenwood 1975:242; Cortella and 2001:105).

Pochettino 1994:172; Guilbot and Mercier Residuesobtainedby surfaceextractionfroma

1985:240;Loy 1994:87-91;MacMaster1964:233; tool, as well as residueextractionfrom adhering

Reichert1913:165;TesterandKarkalas2001:513). sediment,are usually employedto assess if non-

Starchgrainsarecomposedof two differenttypes use contaminationmay be an issue. Since these

of polysaccharides,amyloseandamylopectin.It is tools had alreadybeen washed, this was not an

the orientation of these two organic polymers optionin thepresentanalysis.Instead,theflaketool,

within the granule that impartssemi-crystalline foundat the samedepthandsubjectedto the same

(birefringent)propertiesto starchgrains,produc- sedimentandgroundcoverconditionsas thegrind-

ing a visible anddistinctiveextinctioncross when ing stonetools, was processedin the samemanner.

starchgrains are viewed microscopicallyunder Analysisof theresiduesfromtheflaketool resulted

cross-polarized light (Banks and Greenwood in the recoveryof no starchgrains.This indicates

1975:247;Calvert1997:338;CortelloandPochet- that the abundantstarchgrains recoveredin the

tino 1994:177;GuilbotandMercier1985:241;Loy grindingtools' residueswere probablya resultof

1994:89; Moss 1976:5; Radley 1976:118). The specifictooluse andwerenota resultof starchgrain

presenceof the extinctioncross thatrotatesallows presencein the sediments,even from the time of

for the positiveidentificationof starchin residues initialdeposition.Sedimentsamplesobtainedfrom

obtainedfrom archaeologicalcontexts (Cortello the same depthsas the tools were also processed

and Pochettino1994:177;Loy 1994:89-90). It is andthese samplesdid not containstarchgrains.

thoughtthatstarchgrainsthathavebecome incor- Recently,Haslam(2004) has provideda thor-

poratedinto cracksand crevices on tool surfaces oughreviewof starchgraindecompositionin soils.

during processing activities are protected from Haslam (2004:1717), and previously Perry

degradationandcanthusendureforextremelylong (2001:98, 186),rightlysuggestthatthe absenceof

time periods (Loy 1994:110-111; Pearsallet al. starchgrainsin the surroundingmatrixof starch

2004:437; Perry 2001:186; Piperno and Hoist grain-bearing artifactsshouldnotbe consideredan

1998:768,772). The usewearstriationson the tool assurancethata transferof starchgrainsfromsed-

surfacesas well as the lithic type itself provideda imentsdid not occurwithina shortperiodof time

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Zarillo and Kooyman] EVIDENCE FOR BERRY AND MAIZEPROCESSING 485

afterdeposition.Starchgrainsfrom the sediment from the tools. These slides containedno starch

could be presenton the surfacesof an artifactdue grains,indicatinglabproceduresandreagentswere

to thedifferentialpreservationconditionsprovided not a sourceof starchgraincontamination.There-

by the artifactsurface.As the tools tested in this fore, all lines of evidence, includingthe usewear

studycontainstarchgrainsof wildplantspeciesthat analysis, strongly suggest that the starchgrains

areabundantin the local area,two sedimentsam- recoveredfrom the surfacesof the grindingtools

ples were analyzed from directly below thick representresiduefromtool use, andnot fromsed-

patchesof saskatoonand choke cherryplants in imenttransferor lab contamination.

orderto assess thepotentialfor starchgrainsbeing Althoughtransitorystarchgrainshavenotbeen

presentnaturallyin the sediments.If starchgrains employed in archaeological residue analysis,

did survivein the sedimentsbeneaththesemodern Haslam(2004:1754)has recommendedthatthese

plants,the starchgrainsadheringto thetools might starchgrains should receive more attentionwith

representnaturalcontamination fromthesediment. respectto differentiating betweentransitorystarch

Inaddition,a naturallyfracturedstonewasobtained grainsand small storagestarchgrainsin archaeo-

fromthe soil beneaththe thicketof saskatoonand logical studies.With respectto this study distin-

choke cherrybushesto test whetherstarchgrains guishing between transitory starch grains and

fromtheseberriescouldadhereto andpreserveon storagestarchgrainsis pertinentdue to the small

a lithic fragmentas a resultof sedimenttransfer. size of the Rosaceaefamily storagestarchgrains

Thesedimentsampleswereobtained3-5 cm below (see descriptionsbelow). The structureand shape

the surfaceafterremovalof the leaf litter,directly of transitorystarchgrainshas notbeenextensively

below a saskatoonbush and a choke cherrybush. studied,but the literaturethus far indicates that

The sedimentsamples were processedfor starch transitorystarchgrainsshould "generallybe dis-

grain extraction3by modifying the methods of coid in shape,haveirregularmargins,andtypically

Therin(Lentferet al. 2002:Table2) andPearsallet be less than4-5 urnin diameter,with some grains

al. (2004:428),a techniquethathadbeenused suc- up to 7 jam"(Haslam2004:1723).As the descrip-

cessfullyto extractstarchgrainsfromotherarchae- tions and photographsof the Rosaceae storage

ological sediments(Zarrillo2004b). Despite the starchgrainsand the archaeologicalstarchgrains

visible presence of saskatoonberriesand choke recoveredfromthetoolsindicate,thesestarchesare

cherriesin variousstages of decompositionin the sphericalin shapewhen viewed from all orienta-

sample sediments,only one starchgrain,consis- tionswithgenerallyregularmargins.Althoughtran-

tentwiththeGramineaefamily,was observed.This sitory starch grains from these species or other

indicatesthatstarchgrainsof thesespeciesrapidly regional species have not been examined and

decompose in the sediments of this region or describedas yet, with the exceptionof sunflower

decomposewithin the berriesbefore they can be {Helianthus annuus) (whose transitory starch

releasedinto the soil. The naturallithic fragment grainsare generallydiscoid and rangefrom .2 to

was processedin the samemanneras the archaeo- 5.5 |nmin diameter,with 70-80 percentbetween

logical tools and also tested negative for starch 1.5 and2.5 urn[RadwanandStocking1957:682]),

grains.This is a limited test of the likelihoodof it seems safe to assumeat this time thatthe small-

starchgraintransferencefrom sedimentsto lithic sized starchgrainsrecoveredfromthe residuesof

tools andfurtherworkneeds to be done to under- the tools in this studyarestoragestarchgrainsand

stand the mechanisms involved in starch grain not transitorystarchgrains.

preservationin archaeologicalcontexts.However, Slides were viewed with a transmittedlight

theindicationis that,atleastwithsaskatoonberries microscopeequippedwith polarizingfilters.The

and choke cherries,starchgrainsdo not preserve slides were scanned in their entirety under

in naturalsoils in this regionlong enoughto cont- 400-630X magnification.As stated previously,

aminateandpreserveon lithictools, andtheymay saskatoonandchokecherrystarchgrainswereten-

not preserveat all in such sediments. tativelyidentifiedinitiallyin the residuesbasedon

Controlslideswerealso preparedfollowingthe a limitednumberof comparativestarchgrainsam-

sameproceduresto test for lab contaminationas a ples fromplantsknownby ethnographicaccounts

potential source for the starch grains recovered to have been utilized by Plains peoples. Subse-

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

486 AMERICANANTIQUITY [Vol. 71 , No. 3, 2006

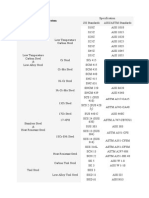

Table 1. ModernPlant Species Testedfor StarchGrains.

Family Genus Species Common Name

Caprifoliaceae Viburnum opulus high-bushcranberry

Chenopodiaceae Chenopodium berlandieri goosefoot

Compositae Balsamorhiza sagittata balsamroot(arrow-leaved)

Cornaceae Cornus stolinifera red osier dogwood

Cupressaceae Juniperus horizontalis creepingjuniper

Elaeagnaceae Elaeagnus commutata silverberry,wolf willow

Elaeagnaceae Shepherdia canadensis Canadianbuffalo-berry

Ericaceae Arctostaphylos uva-ursi common bearberry,kinnikinnick

Ericaceae Vaccinium myrtilloides blueberry

Gramineae Agropyron trachycaulum slenderwheat grass

Gramineae Bouteloua gracilis blue gramagrass

Gramineae Elymus canadensis Canadawild rye

Gramineae Stipa comata needle-and-thread,speargrass

Gramineae Stipa viridula green needle grass

Gramineae Zea mays NorthernFlint maize

Gramineae Zea mays MandanSweet maize

Gramineae Zea mays MandanRed Flour maize

Gramineae Zea mays NorthAmericanDent maize

Grossulariaceae Ribes hudsonianum wild black currant

Grossulariaceae Ribes oxycanthoides wild gooseberry

Leguminosae Psoralea esculenta Indianbreadroot,prairieturnip

Liliaceae Camassia quamash blue camas

Liliaceae Disporum trachycarpum fairybells

Rosaceae Amelanchier alnifolia saskatoon

Rosaceae Prunus pensylvanica pin cherry

Rosaceae Prunus virginiana choke cherry

Rosaceae Rosa acicularis prickly rose

Rosaceae Rubus idaeus wild red raspberry

Rosaceae Sorbus scopulina westernmountain-ash

Typhaceae Typha latifolia common cattail

Umbelliferae Heracleum lanatum cow parsnip

Note: Taxonomicclassificationfollows Moss (1994).

quentlythe numberof nativeplant species tested maize.Fivegrasses(Gramineae)as well as Camas-

for starchgrainswas expandedto include 14 fam- sia quamash(bluecamas),Juniperushorizontalis

ilies, 24 genera, and 28 species, with particular (creepingjuniper),Balsamorhizasagittata (bal-

focus on species of the Rosaceae(rose) family in samroot),and Psoralea esculenta(prairieturnip)

anattemptto confirmtheidentificationof thesaska- were testedfor starchgrainsfromplantsin Kooy-

toon berryand choke cherrystarchgrains.Where man'sherbariumcollection.Table1 lists the plant

possible, severalberry and tuber samples of the species includedin this study.

same species were collected from differentloca- Comparativestarchgrainslides were prepared

tions,includingthe site locale, to accountfor envi- in the followingmanner.Roots, seeds, andberries

ronmentaland intra-speciesvariationsthatmight werewashedandallowedto dryto removeanycon-

be evident in starchgrain morphologyand size taminantspriorto processing.Withrootsandtubers

(Loy 1994:95;PipernoandHolst1998:766;Radley a portionof the cortex was groundwith a clean

1976:3). Berries and roots from several species metalprobein a solutionof 50:50 glycerine-water,

were also collectedin differentstagesof maturity. andthemetalprobewas usedto transferthe starch-

Fourvarietiesof Zeamays(maize)knownfromthe bearing solution onto a microscope slide. More

NortheasternPlainsandNorthAmericawere pre- 50:50 glycerine-waterwas addedif necessaryand

paredfor starchgraincomparison.Theseincluded a cover slip mountedandthe edges sealed.Where

NorthAmericanDent maize as well as Mandan possible with seeds, the endospermor cotyledons

Sweet, Mandan Red Flour, and NorthernFlint wereremovedandpreparedin the samemanneras

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Zarillo and Kooyman] EVIDENCE FOR BERRY AND MAIZEPROCESSING 487

Figure 7. Rose family comparative starch grains: (a) Prunus virginiana; (b) Amelanchieralnifolia; (c) Sorbus scopulina;

(d) Prunuspensylvanica; (e) Rosa acicukuis; (f) Rubus idaeus. Cross-polarizedimages for each species on right Original

magnifications630X, scale bars approximately: (a) 8.5um; (b), (c), (f) 7 urn; (d), (e) 6.5 urn.

the roots. In some cases the seeds were so small Comparative Starch Grain Morphologies

that entire seeds with the seed coats intact were and Confirmation of Starch Grain Species

ground.Slides were preparedin the same manner. Identifications

As stated,wheresamplesallowed,severalslides

were preparedfor each species to assess variation The Rosaceae family comparative starches

in starchgrainmorphologyandsize. Despitethese includedthe following species:Prunusvirginiana

precautionsno discernabledifferencewas noted (choke cherry),Amelanchieralnifolia (saskatoon

between the samplesotherthan size variation.A berry),Sorbusscopulina(westernmountain-ash),

taxonomickey of starchgrainmorphologicaltraits Prunuspensylvanica(pincherry),Rosa acicularis

was developedfor Rosaceaethatfocusedon starch (pricklyrose), and Rubusidaeus (wild red rasp-

grainswith the most distinguishingtraits.Within berry).Mountain-ashis extremelyrarein the study

the six species of Rosaceae analyzed the starch areaand is unlikelyto be representedin archaeo-

grainswerefoundto be verysimilaroverall.How- logical sites. The starchgrainsobtainedfrom the

ever, species-specific starchgrain morphologies fruits of all species in the Rosaceae family were

were definedby comparingmultiplecharacteris- simple spherical grains (with the exception of

tics suchas size range;starchgrainshapeandsur- pricklyrose thatalso has compoundgrains)with a

face features;presence or absence of lamellae; centrallylocatedhilum,regardlessof the viewing

shape,size, visibilityandlocationof thehilum;fis- orientation,and no observablelamellaeor facets.

sures;facets; and patternof the extinctioncross Figure7 shows the diagnosticstarchgrainsrepre-

undercross-polarization. sentativeof each of these species. Characteristics

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

488 AMERICANANTIQUITY [Vol. 71 , No. 3, 2006

of diagnosticstarchgrainsfor each species are as to 5.6 um(mean2.72 um),andtherearefew starch

follows: grains. Some compoundgrains are presentcon-

Prunus virginiana:size range is 2.8-8.4 um sisting of two parts.A centralhilum exists based

(mean44.47 fjm)andstarchgrainsareabundant.A on the intersectionof the arms of the extinction

centralhilum,occasionallyvisible as smallreddot cross, but the hilum is not visible. The cross-

andoccasionallyvisible with cross-polarization is polarizationfigurehas a strongcrossin an"X"pat-

present. The red colorationobserved at the hilum tern. No fissures were observed. A generally

of this species, andwherepresentin the following smoothsurfacetextureis present.

species,remainspresentandobservabledespitethe As stated previously, starch grains of these

use of a color-balancefilterand is not thoughtto speciescanbe distinguishedby observingandcom-

be an artifactof the microscopelight source.The paringmultiplecharacteristics.For instance,if a

cross-polarization figurehas a strongcross with a starchgrainis 8 umin size, has a roughsurfacetex-

shortbar across the hilum. Several fissures (2+, ture,centralhilumnot visible with cross polariza-

andcommonly4+) radiatefromthe hilum.Grains tion, extinctioncross in an "X"pattern,and two

possess a generallyroughsurfacetexture. fissures radiatingfrom the hilum, then western

Amelanchieralnifolia:size rangeis 2.8-8.4 urn mountain-ash,pricklyrose, and raspberrycan be

(mean3.5 um) and starchgrainsare abundant.A eliminatedon the basis of size alone. Saskatoon

centralhilum,usuallyopen and visible as a small berrycan most likely be eliminatedon the basisof

reddot andusuallyvisible with cross-polarization the combinationof fissuresandroughsurfacetex-

is present.Thecross-polarization figurepresentsas ture, leaving the possibility that the starchgrain

a strongcrossin an "X"pattern.Fissuresarerarely would be eitherpin cherryor choke cherry.The

present.The surfacetextureof the grainsis gener- largersize of the starchgrainwould make choke

ally smooth. cherrya more likely possibility,and if the extinc-

Prunuspensylvanica:size rangeis 2.8-8.4 um tioncrosshada barbetweenthe armsthenit would

(mean2.74 um) andstarchgrainsareabundant.A makethis identificationvery probable.

centralhilum,usuallyopenandvisible as a reddot Twospeciesof theGrossulariceae (currant)fam-

andoftenvisiblewithcross-polarization is present. ily, Ribes oxycanthoides(wild gooseberry) and

The cross-polarization figurehas a strongcross in Ribeshudsonianum(wildblackcurrant),hadstarch

an "X"pattern.Therearefissures(usually2) radi- grainsin theirberryseeds similarto those of the

atingfromhilum.The surfacetextureis generally Rosaceae family starches. However, the starch

rough. grainsproduced,with a maximumsize of 3 um,

Sorbus scopulina: size range is 2.8-7.0 um were too small to be a sourceof the starchgrains

(mean 3.21 um) and starchgrains are abundant. observed in the residues from the ground stone

While the shapesof the grainsare spherical,they tools and these species producevery few starch

often have irregularmarginsand appearas some- grains.None of the otherplantspeciesfromthe 12

whatpolygonal.A centralhilum,usuallyopenand otherfamiliesof plantsin the comparativecollec-

visibleas a largerreddotin comparisonto theover- tion possessed starchgrains similarto Rosaceae

all grain size, is presentand usually visible with family starchgrains.

cross-polarization.The cross-polarizationfigure Figure 8 shows a starchgrainrecoveredfrom

has a strongcrossin an "X"pattern.Thereareusu- the grindingpebbleresiduesthatis representative

ally severalfissures(2+) radiatingfromthe hilum. of the choke cherrystarchgrainsrecoveredfrom

A generallyroughsurfacetextureis present. the residues of both tools. The cross-polarized

Rubusidaeus:size rangeis 1.4-4.2 um (mean image shows the characteristicchoke cherrypat-

2.56 um)andtherearefew starchgrains.A central ternof the extinctioncross wherebya shortbaris

hilumoften visible as a reddot andusuallyvisible presentacross the hilum joining the arms of the

with cross-polarization is present. The cross- extinctioncross.The size of thisstarchgrainalone,

polarizationfigurehasa strongcrossin an"X"pat- at 8 um,is beyondthemaximumsize rangeof west-

tern.No fissuresarepresent.The grainsgenerally ernmountain-ash, pricklyrose,andraspberry, mak-

have a smoothsurfacetexture. ing it unlikelythatthis starchgrainis one of those

Rosa acicularis:size is 2.0 um, very rarelyup species. In addition,the roughsurfacetextureand

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Zarillo and Kooyman] EVIDENCE FOR BERRY AND MAIZEPROCESSING 489

Figure 8. Starch grains recovered from EgPn-612 grinding tool residues identified as: (a) choke cherry (Prunus virgini-

ana); (b) saskatoon (Amelanchieralnifolia). Cross-polarizedimages to right Original magnifications:(a) 400X, scale bar

approximately 10 um; (b) 500X, scale bar approximately 8 um.

fissures radiatingfrom the hilum also make it were recoveredfromthe grindingslab.

unlikely that this starchgrain is from saskatoon Theidentificationof chokecherryandsaskatoon

berry.The largeroverallsize, patternof the extinc- starchgrainsin the residuesfrom the two ground

tioncrossandlackof visiblehilum,with andwith- stonetools is moresecurethanwiththeinitialiden-

out cross-polarization,makeit less likely thatthis tification in that several other Rosaceae family

starchgrainis frompin cherryandmorelikely that starchgrainshavebeen eliminatedas possibilities.

it is chokecherry.Indeed,thisstarchgrainpossesses These species were chosen as they are known to

all of the distinguishingcharacteristicsidentified growin thisregionof Albertaandarealso reported

for choke cherrystarchgrainsas describedabove to havebeen widely utilizedby pastPlainspeople.

andas shownin Figure7. As it has been shown thatthe starchgrainsfound

Figure 8 also shows a starchgrain recovered in the residueson these tools are most probablya

fromthe grindingpebbleresiduethatis identified productof use andnot due to sedimentor lab con-

as most probablysaskatoonberrydue to the fol- tamination,andthatgrindingstoneswereverycom-

lowingcharacteristics. The size of the starchgrain monlyusedto processchokecherriesandsaskatoon

(8 um) eliminateswesternmountain-ash,prickly berries, these identificationsseem quite secure.

roseandraspberryas possibilities.Thesmoothsur- However,until the starchgrain comparativecol-

face texture,open and visible hila with and with- lectionis furtherexpandedto includestarchesfrom

out cross-polarization,and lack of fissures also all AlbertaRosaceae species, these species-level

eliminatesthe possibilityof pin cherryand choke identificationscannotbe viewed as absolutelycer-

cherry.The starchgrain shows all of the distin- tain.

guishing characteristicsidentified for saskatoon As discussedpreviously,bearberryand maize

berrystarchgrains,and comparablestarchgrains havethepotentialto be representedas theyaredoc-

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

490 AMERICANANTIQUITY [Vol. 71 , No. 3, 2006

umented to have been processed with grinding or Blake 2001 :1 1). Maize is present in sites of the Ini-

pounding stones. Common bearberry (Arc- tial Variant of the Middle Missouri Tradition

tostaphylos uva-ursi) fruits collected and processed (IMMV) that date to A.D. 1000-1300 (Schneider

for comparative starchgrain examination contained 2002:45). EasternEight Row, which is early matur-

seeds that produce very few starch grains. In addi- ing and resistant to cold, drought, rot and insects,

tion, the starch grains were extremely small in size is often flint, but may also be flour or sweet, with

and difficult to isolate; further work is required flint being the most resistant to rot and insects mak-

with this species. ing it the most suitable for transport. As a result,

Maize starch grains have been extensively stud- flint maize was used extensively during the Fur

ied in other regions, in particular the Neotropics, Trade era (Blake 2001:54-56). While the genetic

due to the importance of this domesticate in the mechanisms for hybridization were not known,

Americas prior to the arrival of Europeans (e.g., Native Americans were well aware of the need to

Pearsall 2003; Pearsall et al. 2004; Perry 2001, maintain pure strains of the maize varieties (flint,

2004; Piperno and Hoist 1998; Piperno et al. 2000). flour, or sweet) by separating fields of the different

Zea mays, a giant domesticate of the Gramineae types during planting, as described by Maxi'diwiac

family, is monoeicious, naturally cross-pollinates (Buffalo Bird Woman) of the Hidatsa (Wilson

and hybridizes freely (Hancock 2004:176-177; 1977:59-60).

Langer and Hill 1991 :1 19-122; Purseglove 1972). In addition to the archaeological literaturewhere

At the time of European arrivalin the New World, maize variety starch grains have been studied and

hundreds of varieties of maize were being grown described (Pearsall 2003; Pearsall et al. 2004; Perry

as a crop from Argentina to Canada (Hancock 2001 ; Piperno and Hoist 1998; Piperno et al. 2000),

2004: 180). Maize varieties can be grouped into cat- several other sources were consulted to establish

egories according to grain (kernel) structure, usu- whether our own comparative sample starch grains

ally dependent upon one of a few genes, and were consistent with the published descriptions and

include: popcorn (everta), possessing an extremely photomicrographs(Moss 1976; Reichert 1913; Sei-

hard endosperm and a small amount of soft starch demann 1966). Although Mandan sweet maize was

in the center that explodes upon heating; flint prepared for comparison, sweet maize was not a

(indurata), in which the grains mainly consist of a trade commodity and was not an important crop to

hard endosperm with some soft starch in the cen- Native North Americans (Cutler and Blake 2001;

ter;flour (amylacea), in which the endosperm is soft Will and Hyde 1968; Wilson 1977). Similarly, dent

and floury; dent (indentata), where the sides and maize was not grown in the Middle Missouri where

bottom of the grain possess hard starch, while soft trade into the Canadian Plains would have origi-

starch is above the hard starch and extends to the nated. However, both of these varieties were

top of the grain that, upon drying, shrinks to pro- included in our comparative specimens. In general,

duce the "dent";and sweet (saccharata), where the although maize variety starch grains are quite sim-

endosperm contains a glossy, sugary (sweet) ilar, flint and flour maize can be distinguished with

endosperm and the grains are translucent when some certainty if diagnostic forms are observed,

immature (Hancock 2004:180; Langer and Hill especially when based on a population of starch

1991:122-123; Reichert 1913:343-344). Of the grains (Pearsall et al. 2004; Perry2001 ; Piperno and

varieties of maize grown in the Americas, flint, Hoist 1998; Piperno et al. 2000). Our comparative

flour, and sweet maize varieties were grown by the starch grains for Northern Flint and Mandan Red

Plains Village horticulturalists; dent corn was not Flour maize were consistent with the following

grown (Lowie 1954:22) but was included in this published descriptions.

study to assess its starch grain morphology with The diagnostic features of flint maize starch

respect to published descriptions and in compari- grains include: simple (single) grain in a blocky

son to the other varieties tested. polygon shape (due to pressure facets) with slightly

Northern Flint maize, also known as Maize de smoothed edges; hemispherical and "vase" shapes

Ocho and Eastern Eight Row, was the dominant are also possible; a distinct double border; a cen-

variety of maize grown east of the Rockies, includ- tral or slightly eccentric hilum, often open and with

ing the Middle Missouri (Blake 2001 :54; Cutlerand a single fissure or fissures (commonly three in the

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Zarlllo and Kooyman] EVIDENCE FOR BERRY AND MAIZEPROCESSING 491

Figure 9. Zea mays starch grains recovered from EgPn-612 grinding tool residues: (a) grinding pebble Flint maize; (b)

grinding slab Flint maize; (c) maize starch grain showing damage consistent with mining, cross-polarized to right

Original magnifications400X, scale bars approximately 20 urn.

shapeof a "Y");no lamellae;a rough,crateredor distinctivefeaturesof flintmaizeincludingblocky

groovedsurface;when the polarizeris rotated,the polygonal shapewith roundededges, centralhila

armsof the extinctioncross seem to bend andfol- with the characteristic"Y" fissures, and double

low the edges of the polygon in threedimensions; borders.Theflintmaizestarchgrainsshownin Fig-

size range4-24 |jm (Moss 1976:13; Pearsallet al. ure 9 from the grindingpebble and grindingslab,

2004:430-432;Perry2001:136;PipernoandHoist withmaximumwidthsof 20 urnand 18 urnrespec-

1998:775; Piperno et al. 2000:897; Reichert tively,aretypicalof theassemblageof maizestarch

1913:346-348). grainsobservedin the residues.Starchgrainscon-

Flourmaize starchgrainsaredescribedas sim- sistentwith maize were abundanton the tools and

ple (single) grain with a smooth surface and represented34 percentof all starchgrains(n = 106)

roundedshape;a distinctdoubleborder;no lamel- in the grindingslab residuesand 61 percentof all

lae;a centralorslightlyeccentrichilumthatappears starch grains (n = 51) in the grinding pebble

"fuzzy" and "fades from white to grey" (Perry residuespreparedforeachtool.Vase-shapedmaize

2001:136) as the fine focus on the microscopeis starchgrainswere also observedin boththe grind-

adjusted;size rangeis A- 24 urn(Moss 1976:13; ing slabandgrindingpebbleresidues.Starchgrains

Pearsall et al. 2004:430-432; Perry 2001:136; completelydiagnosticof flint maize represent56

Piperno and Hoist 1998:775; Piperno et al. percentof the 36 maize starchgrainsin the grind-

2000:897). ing slab residuesand 68 percentof the 31 maize

Figure9 showsstarchgrainsrecoveredfromthe starchgrainsin the grindingpebbleresidues.Only

surfaceof thegrindingpebbleandgrindingslabthat a couple of starchgrainsin the residuesfromeach

are consistentin size, shape,and othercharacter- of the tools were diagnosticof flourmaize, andas

istics with flintmaize.Both starchgrainsshow the flintmaize kernelscontainsome soft starchthis is

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

492 AMERICANANTIQUITY [Vol. 71 , No. 3, 2006

to be expected.Thesedataindicatethatflintmaize residues,but considerablymore Gramineaeseeds

wasthevarietyof maizegroundwiththetools used need to be obtainedand preparedfor starchcom-

in this study.Withrespectto othernativegrasses parisonto confirmthis identificationas well. The

in the region that might be confused for maize starchgrainsof atleastthreeotherunknownspecies

starchgrains,the most common C4 plant is blue were consistentlyobservedin the residuesof both

gramagrass(Boutelouagracilis).Thestarchgrains the grindingslab andgrindingpebble.The variety

of the comparativespecimen of blue grama are of starch grain morphologies present in these

polygonalin shapebut with sharpedges. In addi- residuesindicatesthatthe tools wereusedtogether

tion, the maximumsize is 8 urn,which is far too to processa numberof differentplantspecies,either

small to accountfor the starchgrainsin the tool in one episodeor in successiveepisodes.

residuesidentifiedas maize. The starchgrainsof

the other four comparativegrass species were Discussion

unlikemaizein thattheyaresphericalin shapeand

moresimilarin appearance to wheat(Triticumspp.) The purposeof this study was to assess whether

starchgrains. Numerous damagedmaize starch starchgrainanalysiscouldfacilitatethe identifica-

grains,as shown in Figure9, were also observed tion of plantprocessingon unmodifiedlithictools

in theresiduesof bothtools.Thesedamagedstarch andin thisregardourresultsshowthatthisis indeed

grainsshow changescharacteristicof drymilling, the case. The ethnographicandethnohistoricliter-

such as fissureson the edges of the starchgrains aturereviewedhereindicatesthata wide varietyof

thatarenot of naturalorigin,fracturedandincom- plant species were utilized on the Northernand

pletegrains,andchangesto theshapeof theextinc- CanadianPlains, many of which were processed

tioncross(Babot2003:76).As notedearlier,thesite by grindingandpounding,andthatfact is evident

hasneverbeenundermoderncultivationandmaize in the varietyof starchgrainspresenton the tools

was not knownto be grownin this regionin pre- usedfor this analysis.Of theplantspeciestargeted

contacttimes.Itis thereforeunlikelythatthemaize for starchgrainanalysischoke cherry,saskatoon,

starchgrainspresenton the tools are the resultof and maize are most assuredlyrepresentedon the

anythingotherthanmaize kernelsbeing brought toolsusedin thisstudybasedon comparisonto cur-

ortradedintotheregionandmilledwiththe grind- rent reference material. The identifications of

ing stones. prairieturnipand slenderwheatgrassrequirefur-

Withrespectto theidentificationof otherstarch therconfirmation,and at this time it appearsthat

grainsin theresiduesof thegrindingtools,thiswork bearberryis not likely to be identifiableby starch

is continuingandit is hopedthatfurtheridentifica- grainanalysisdue to the small numbersof starch

tions may be madein the future.However,several grainsthatthis speciesproduces,althoughthistoo

commentsmightbe madeatthistimeregardingthe requiresadditionalwork.Givenourextremelypoor

varietyof starchgrainspresentintheresidues.Based understandingof pre-Europeancontactplantuse

on overallstarchgrainmorphologyit appearsthat on the NorthernPlains,theseresultsareextremely

a varietyof plantspecieswereprocessedwiththese important.Whatis equallynoteworthyis thatthese

tools.Starchgrainsconsistentwiththecomparative resultshave providedan exceptionalwindowinto

specimens of Psoralea esculenta (prairie the use of wild plantspecies, an aspectof human

turnip/Indianbreadroot)are present in both the historythatis poorlyunderstoodin manyregions

grindingpebbleandgrindingslabresidues.As only of the worldin additionto the NorthernPlains.

twosamplesof prairieturnipwereavailableas com- Numerouslinesof evidencedemonstrate thatthe

parativespecimens,and, more importantly,other starchgrainsrecoveredfrom the tool residuesare

nativeLeguminosaefamilyplantstarcheshavenot a resultof tool use andnot from any formof con-

been collected as yet, this identificationremains tamination.This conclusionis also supportedby

tentative until the comparative collection is therecoveryof thesameassortmentof starchgrains

expanded.Numerousstarchgrainswithmorpholo- on bothtoolsandby thefactthatthetoolsalso show

gies consistentwith the grassfamily (Gramineae), usewearconsistentwithpoundingandgrinding.In

in particularAgropyrontrachycaulum(slender particular,it is unlikelythattransferenceof choke

wheatgrass)basedon size, are also presentin the cherryand saskatoonstarchgrainsoccurredfrom

This content downloaded from 136.159.235.223 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 19:47:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Zarillo and Kooyman] EVIDENCE FOR BERRY AND MAIZEPROCESSING 493

the sedimentsto the tools, as ourtestsindicatethat InAlbertastonecairnsareusuallyfoundin asso-

thestarchgrainsfromthesespeciesdidnotpreserve ciationwithtipiringsorin isolationon hilltopsand

in these soils. The reasonsfor this lack of preser- benches(Reeveset al. 2001:46),as is the case with

vation,while not surprising,requirefurtherstudy the cairnsat EgPn-612.Cairnswere used as trail

but undoubtedly involve the complex inter- markers,as boundaryanddirectionalmarkers,for

relationshipsbetweenthe enzymes presentin the primaryand secondaryburials,and for religious

soil, the alkalinityof these soils, the soil moisture purposessuch as vision questmarkersor as offer-

content,andthe yearlyfreeze-thawcycle (Haslam ing places to commemorate or mark a

2004:1718-1722). The presenceof maize should special/sacredplace (Reeves et al. 2001:46). The

be consideredexotic to the regionin the sameway archaeologicalsurveyand test excavationsin the

that obsidian would be to the lithic analyst.As immediateareanearthe cairnsdid not revealany

maizecouldnot be partof the backgroundvegeta- otherassociatedsites suchas kill sitesorcampsites

tion,eitheratthetimethetoolswereutilizedorlater, andthe excavationof the cairnsproducedonly the

and thereforecould not have naturallycontami- grindingtools, some cores and debitage,and an

natedthe tools, its presencelends furthersupport unusedflaketool (RamsayandRamsay2001). The

to ourcontentionthatthestarchgrainsfromthetool site may be connected with one or more of the

residuesarea directresultof tool use. campandkill sitespresentwithina few kilometers

The evidence for tradeof maize into western of the site, butnone areparticularlyclose to it. On

Canadais significantbutcomesas no surprisegiven the otherhand,the immediatesite areahas a rich

the extensiveindicationsof tradein the ethnohis- diversityof plants and so it is quite possible that

toricliteratureand from lithic materialin archae- thesitewas specificallylocated,andreturnedto sea-

ologicalsites.Thetradeof maizeis unlikelyto date sonally,to undertakespecializedplantprocessing

earlierthatA.D. 1000-1300 (Adair1996:110-111; activities.Wissler(1986:21) notedthatduringthe

Hartet al. 2003), althoughmaizeis presentjusteast berry season Blackfoot camps were specifically

of the Plainsby about2,000 yearsago (Bellwood located to procurethese resources and Peacock

2005:155;Riley et al. 1994), andis morelikely to (1993:49) has drawnattentionto the fact thatthe

dateto themorerecentendof thattimerange,once importanceof berriesis seen in monthnamesfor

horticulture wasbetterestablished.Clearlya larger JulyandAugustreferringto saskatoonsandchoke

samplesize is requiredfromother,dated,contexts cherries,respectively,ripening.The cairns were

to morefully appreciateourresults,butatthistime likely used to markwhere the tools were buried,

it seems importantto stressthatboththe resultsof the locationitself (thecairnswouldhavebeen vis-