GombrichErnstHansJosef - How To Read A Painting (Revised) PDF

Diunggah oleh

Μέμνων Μπερδεμένος100%(2)100% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (2 suara)

760 tayangan4 halamanJudul Asli

GombrichErnstHansJosef - How to Read a Painting (revised).pdf

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

100%(2)100% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (2 suara)

760 tayangan4 halamanGombrichErnstHansJosef - How To Read A Painting (Revised) PDF

Diunggah oleh

Μέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςHak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 4

How ADVENTURES

of the MIND

to Read a

Painting

By visual paradoxes the artist shocks the viewer into the

realization that there is more

By E. H. GOMBRICH

to art than meets the eye.

one of Molire's immortal witticisms is surer to get a

N laugh from a modern audience than the surprise of

his Bourgeois Gentilhomme when he is told that he

has been talking prose all his life. But was poor M. Jourdain

all that silly? What he had discovered in his frantic efforts to

climb into the class of noblemen was, of course, not prose, but

verse. The notion of prose as a special kind of speech could

never have been thought of without the poets truly surprising

ways with language, so well described by the author of Alice

in Wonderland:

For first you write a sentence,

And then you chop it small;

Then mix the bits, and sort them out Just as

they chance to fall:

The order of the phrases makes No

difference at all.

Ernst Hans Gombrich director of the Warburg Institute of the University of The corresponding ways with images practiced by twentieth-century

London and professor of the classical tradition there, was born in Vienna, which artists have turned us all into M. Jourdains. They have shocked us into a

he left in 1936 under the shadow of the Nazi terror. Professor Gombrich has

fresh awareness of the prose of pictorial representation.

written extensively on the history and theory of art. His latest book, published in

this country by Pantheon Books, Inc., is Art and Illusion, which he originally If we had told an art lover of former days that a picture needed

delivered as the A. W. Mellon Lecturer in Fine Arts at the National Gallery in deciphering, he would have thought of symbols and emblems with some

Washington in 1956. Professor Gombrich who has taught also at Oxford Harvard

cryptic hieroglyphic' content. Take the

and Oberlin, gave the 1961 Spencer Trask Lectures at Princeton University.

21

those tactile values we need for recognition and participation in his

world? If so, where should he stop? It is not only touch that gives us

information. It is movement, looking at objects from several sides.

Without such movement we would never learn to sort out the impressions

received by our eyes.

So the debate went on, and representation became self-conscious. The

cubist revolution some fifty years ago established the painters right to

present his own commentaries to the conundrum of vision. Instead of

tracing the image of a camera obscura, the artist superimposes and

telescopes fragments of representations which follow a mysterious order

of

Fig. 1. Still Life.

Jan Simonsz Torrentius, seventeenth century.

still life by the Dutch seventeenth-century painter Torrentius (Fig. l). It

seems clear enough as a representation, and for good reasons: We know

that the artist used an optical device, the camera obscura, to project the

image of the motifs onto the canvas where he traced it as one might trace

a projected photograph. What wonder that it seemed just as easy to

recognize the objects in the picture as it would be to recognize them on

the table. If deciphering came in at all, it applied to a second level of

meaning, as it wereto the question of what these objects might signify.

To the learned Gentilhomme they would suggest more than a jug, a glass

and a yoke, for he would recognize in this curious assemblage the

emblems or attributes of the personification of Temperance, a lady with

the laudable habit of pouring water into her wine and a corresponding

disposition meekly to accept the bridle and the yoke.

It was only when learned allusions of this kind went out of fashion,

and when everybody could reproduce the image of objects by means of

his own photographic camera, that artists began to question the simple

Fig. 2. Still Life. Pablo Picasso, 1931.

assumptions underlying the still- life painters craft. No sooner had they

done so than the public questioned their competence. What impudence of

the impressionists to demand of us to decipher their blots and splashes! their own (Fig. 2). No longer will a simple trick suffice to recover the

But this is easy, retorted the painter's champions. Just step back and half- object on the table. Like the ghost of Hamlets father, It is here, it is

close your eyes, and the blots will fall into place. The magic worked, and there, it is gone.

the outcry subsided. What remained was the conviction that the artist There were and still are critics who claim that this tantalizing method

knew more about seeing than the layman. Surprising as it may sound, the represents some higher order of reality than does the photographic

blots must be all we really see of a motif on the table. If we recognize picture. It may well be that Picasso and Braque, who invented the style,

things more easily in life than on impressionist pictures, it is because we were inspired by echoes of similar mystic beliefs. But the continent they

can touch and handle objects and thus acquire knowledge of properties found on their voyage of discovery was not the never-never land of the

which we have no right to ask the artist to paint. fourth dimension, but the fascinating reality of visual ambiguity. We are

No right? Why not? Should we not demand of the artist precisely for in danger of missing this fascination through sheer familiarity with cubist

this reason that he must somehow include in his pictures that methods which have long since penetrated into commercial art. The shock

indispensable information gained from touch, has worn off, and we no longer attempt to decipher the images that play

hide-and-seek among the facets of ambiguous patterns. And thus we are

apt to miss the real problem posed by the first of the modern styles that

broke resolutely with the photo- graphic rendering of

reality How should each individual form be read?

How are the shapes related to each other? Where is

the key to the code?

For first you paint an object.

And then you chop it small;

Then mix the bits, and sort them out Just as

they chance to fall;

The order of the aspects makes No difference at all

This strange and fascinating way of jumbling

the elements of representation is perhaps a novel

kind of verse that makes us aware of the existence

of prose, For how are the elements ordered in

naturalistic pictures, that we should find it so easy,

by contrast, to read into them images of tangible

things? The formulation may cause some shaking of

heads. Surely we do not read the shape of a jug and

a glass into the Dutch still life; we simply recognize

it. Of course we do. But where exactly is the

borderline here between reading into and reading?

We are all familiar with the clouds, rocks or ink

Fig. 4. Royalist print from

blots into which the fanciful can read pictures of

monsters or masks. Some vague similarity to a face the French Revolution.

or body engages our attention, and we proceed to

project the remainder into the welter of forms propagandists to catch us off our guard. Figure 4

searching for features that fit in with the first idea. looks for all the world like the representation of a

Psychologists and psychiatrists have become classic urn set amidst willows. It was circulated

interested in this game of the imagination, and ink- during the French Revolution as a clandestine Fig. 6. Solid and Hollow. Lithograph. M. C. Escher, 1955.

blot-reading tests, such as the Rorschach, are tribute to the royal family. For if we don't focus on

supposed to tell them much of the working of a per- the urn. But on the background, we discover the But Escher has more tricks in his bag to have to begin all over again, only to discover that

son's mind. They are interested, in other words, in profiles, facing each other, of Louis XVI and Marie undermine our confidence in the simplicity of here too we are ted into perplexity.

the different interpretations that are given of the Antoinette and, guided by these cues, two further representation. His print Solid and Hollow (Fig. 6) But even this probing of the mechanisms of

same blot. It is these differences we have in mind heads, presumably of the Dauphin and some other makes use of other forms of ambiguity which had image reading is not the most disconcerting of

when we speak of "reading in. Where all normal victim, made by the outline of branches and twigs. been known to artists and psychologists for a Escher's exercises. The Belvedere (Fig, 7).

people see the same image, we call it reading, We The principle here exploited by a humble longtime, but had never been explored and Completed in 1958, may not be very pleasing as a

all read the jug correctly because it looks like a draftsman has played a great role in the discussions exploited with such single-mindedness. print, but as a demonstration piece it trumps the

jug. But this simple formulation begs a good many of twentieth-century psychologistsit is the Here I is not the relationship between figure and others. For what looks at first like a rather crude

questions which hide the mystery of reading from relation between figure" and "ground." As long as ground that is reversed on the other side, but the historical illustration is, in fact, a brain leaser of

us. we regard the urn as the figure we are not aware of very shape and direction of any part of the no mean ingenuity. It would make an excellent

We come a little closer to its core with some of the shape of the ground. Here, therefore, is (he architecture. Start on the left with the black woman test of the powers of observation to time the

the trick pictures in which sur- realist artists simplest case of all where our reading depends on walking over a curved bridge toward some stairs. moment when it dawns on the beholder that he is

conjured up the ambiguities of dreams. our initial interpretation. We tend to regard the As long as you stay on her side of the picture you confronted with a self-contradictory structure.

Tchelitchew, for instance, turns a tree into the enclosed and articulated shape as the figure and to are presented with a weird but plausible view of an Look at the ladder and try to locate it in space.

image of a hand growing out of a foot (Fig. 31. He ignore the background against which it stands. But old town. Start with the man climbing a ladder on You will find that it leads from a first-floor

guides our projection by assimilating the shape this interpretation itself is based on an assumption the opposite side and you will read the shapes as terrace to a second at right angles to it. The man

which the artist may choose to knock away. It is equally coherent forms representing an unfinished with the plumed hat on the lower terrace looks out

then that we discover that there really is a phase courtyard with a bridge vaulting over it. But once into the landscape behind, the woman under the

prior to the identification of the jug or the urnthe again either reading is contradicted when you read corresponding arch of the floor above looks

decision on our part which to regard as figure and on toward the central axis, for what looks like a sideways. Small wonder, for the arcades of the

which as ground pavilion seen from the outside, if you approach it lower terrace are not composed or columns

This is the moment to introduce a con- from the side of the black woman on the bridge, is carrying the vault above them: they are interlaced,

temporary artist whose prints are meditations on switched into a vaulted corner when seen from the as it were, shifting from back to front as we trace

image reading. His name is M. C. Escher, and he other side. The switch is all the more puzzling as their course.

lives in his native Holland, keeping more contact the identical shape nearby must surely be read as a Who can blame the poor imprisoned man in the

with mathematicians than with artists and critics. It solid pavilion. But soon we discover the same cellar who looks with amazement at the designer

is indeed doubtful how much the critics would punning with inside and outside all over the print. on the bench, for the object he holds in bis hands

approve of his ingenious exercises in applied The floor on which a boy has fallen asleep is a is as unrealizable as the building itself; a cube

geometry and psychology. But to the explorer of ceiling nearby from which a lamp dangles. with interweaving sides.

the prose of representation, his nightmarish conun- Everywhere corresponding shapes must be read as Whatever we may think of Escher's artistic

drums are invaluable. His double image of Day and hollow in one context and solid in another and, taste, his prints are worth a whole course in the

Night (Fig. 5) demands an imperceptible switch every time, the meeting of both readings creates a psychology of perception and its relation to art.

from figure to ground: The white birds flying stalemate. The assumption with which we have Their complexity is far from whimsical. It reveals

across the dark toward the black fiver come from started breaks down, and we the hidden complexity of all picture reading.

another side of the world where there is still

daylight and where black birds go the other way.

And as we search for the dividing line between the

two halves, we notice that there is none. It is the

interstices between the white birds the ground

(hat gradually assume the shape of the black birds,

and these checkered patterns merge downward into

the fields of the countryside. Easy as it is to

discover this transformation, it is impossible to

keep both readings stable in one's mind.

The day reading drives out the night from the

middle of the sheet, the night reading turns the

black, birds of the same area into neutral ground.

Which forms we isolate for identification depends

on where we arrive from, Reading becomes

alternative "reading into"; representation merges

with guided projection.

Fig. 3. Tire into Hand and Fool. Pavel

Tchelitchew, 1939.

of the tree to other recognizable forms. But such

visual punning is still comparatively simple. For

here (not in his other pictures) the artist has taken

care that we should know where to look for the

meaning. We cannot always take this for granted

Indeed, our tendency to jump to conclusions here

has been used by the devisers of puzzle pictures

and even by

Fig. 5. Day and Night. Woodcut. M. C. Escher, 1938.

65

ing ahead for cues to confirm our expectations into awareness of an old truth we had lazily taken on the paper are sorted out by the mind into a

When we look at a normal representation, there

and filling in the remainder more or less from for granted. The problems of vision in rapid flight consistent and coherent message Once this

is nothing to prevent us from forming a

experience. The reading of pictures must follow a or even in motoring rendered the old idea of static consistency is perceived and an interpretation

hypothesis about the figure- ground relationship

or about the way the shapes add up to pictures of similar pattern. But once we set ourselves to read vision obsolete. Moreover, our engineers had emerges, it takes a great effort to dislodge it. Easy

objects. We therefore believe that we take in the the "score, the need to revise our expectations meanwhile learned to simulate the function of though it is to know intellectually that our poor

picture more or less at one glance and recognize makes us aware of the part which assumptions sense organs with the uncanny gadgets of homing stable- boy's head lies objectively in the same

the motif. Our experience with Eschers play in the reading of images. devices, used in the deadly game of missile plane as do his feet, we still do not quite see it that

contradictions shows that this view is mistaken. What, more precisely, are these assumptions? development Cybernetics has taught us to look way.

We do read a picture, as we read a printed line, Take any isolated part of Escher's print, the even at the senses not as passive registration It is here, at last, that these investigations of the

by picking up letters or cues and fitting them outside terrace, for instance, with its checkerboard devices but rather as receptors geared to the prose of representation lead back to the problems

together till we feel that we look across the signs floor and the low walls surrounding it. This is receipt of a flow of information, which the nervous of artistic poetry. For it is the strength of the

on the page at the meaning behind them. And just quite a nor- mal realistic representation of an system is somehow programed to compare with forces of illusion that alone accounts for the

as in reading the eye does not travel along at an architectural feature and docs not differ much expectations. Some psychologists think that the violent reactions against these forces in twentieth-

even pace gathering up the meaning letter by from a photograph or picture post card of such a simplicity hypothesis, the idea that the floor is cenlury art. At all times, of course, the aesthetics

letter and word by word, so our glance sweeps motif. How is it that we take in such a situation probably level, may be built into our receptor of picturemaking had more to do with composition

across a picture scanning it for information. with such speed and ease? Surely because we are organ. But whether they are inborn or acquired, it than with illusion. Artists have always been poets,

Critics like to tell us how the artist leads the in no doubt on how to supplement the information is now clear that every message sets up a set of striving to achieve a fine balance of shapes and

eye" along the main lines of his composition. But with which the picture supplies us. We assume that expectations with which the incoming flow can be colors and to devise a beautiful pattern to fill the

our roving eyes will not be thus led. The critic's matched to confirm correct assessments or to painting surface in a pleasing way. But these

a pavement will most probably be level and a wall

phrase should have become obsolete when eye modify and knock out false guesses. efforts could easily be destroyed by the reading

upright, that the slabs of the floor will be square

movements could be filmed and fixation points In looking at a picture we are deprived of this mind that rearranged these shapes in an imaginary

and the seat of the bench rectangular. If the shapes

representing these objects are tapering and dynamic aid for the weeding out of false depth.

unequal in size, this will obviously be due to interpretations. All we have is a consistency test

foreshortening and perspective. that compares the messages from various parts of

Assumptions of this kind are so ingrained in us the picture for compatibility. Having done so, our

that it needs quite a jolt to prevent our mind makes ready for further tests through

interpretation from running along these convenient movement, but here it is frustrated. This

grooves. Yet, after all, there could be such things frustration has a curious side effect that can

as sloping floors with irregularly sized slabs, paradoxically increase the illusion and will never

tapering walls or rhomboid benches. Such odd cease to tease our reason. It is the illusion that

shapes might serve a very good purpose in the objects pointing toward us from paintings will

theater, near the back of an illusionist stage to follow us as we shift our position.

give the impression of greater depth. Once we The most bored and footsore tourist will spring

admit this possibility, our assurance in reading the to attention when the guide demonstrates the

image collapses. We discover the hidden ancestral portrait that follows him with its eyes or

ambiguity in all representations of solid objects in the pointed gun that always aims at him wherever

the flat. If the reader enjoys a whirling head he he stands in the hall. It is easy to dismiss this

can now return to a fresh scrutiny of all the three surprise as naive, but less easy to exhaust the

Escher prints (Figs. 5-7) to discover that these implications of this little mystery. One thing is

leasing images are "ambiguous" only on the sure: The mystery does not rest in any particular

assumption that floors or ceilings are horizontal, skill on the part of the painter. The effect is quite

columns upright or the water of rivers reasonably frequent and indeed inevitable. The only reason

level so that the bridge across it cannot lead why we need the guides patter to enlist our

uphill. Drop this hypothesis of simplicity, and the attention is that we are but rarely interested in

neat ambiguity of a mere double meaning sinks what happens to the appearance of a painting while

into chaos. we shift our position in this way. If we were, we

We return from this giddy switchback ride with would see that the principal condition for the

one tormenting question in mind. If the prose of effect is a sense of depth combined with an

ordinary representations hides such unsuspected unforeshortened portion of an object that appears

ambiguities, what about the reliability of our eyes to lie quite close to the frontal plane

to tell us about the real world? We need not worry The woodcut by the German Renaissance artist

too much, for here the answer is more reassuring. Hans Baldung Grien (Fig. 8), for instance, fulfills

To pull the matter briefly, pictures are infinitely these conditions admirably. It is known under the

Fig. 7. Belvedere. Lithograph. M. C. ambiguous because they present a flat two- title "The Bewitched Stableboy" and it shows the

Escher, 1958. dimensional geometrical projection of a three- victim of some evil spell lying on his back, the

dimensional reality. To say of such a projection soles of his feet turned toward us. Critics have

Fig. 8. The Bewitched Stableboy. Woodcut Hans

that it looks like reality" begs the question. It wondered what the picture signifies, but surely it

plotted on pictures. These records confirm what

is meant to lease us with this magic trick. When Baldung Grien, 1544.

Escher made us suspect: Reading a picture is a may, but it also looks like an infinite number of

unreal configurations. But this type of ambiguity we have it in front of us, it works like any

piecemeal affair that starts with random shots and

will rarely trouble us in real life. After all, we ordinary perspective. The strong foreshortening is

gradually adjusts to the coherence of the work. Critics wrote and still write as if we could see

experience the real world by moving about it, and "read" as depth, and we feel the three-dimensional

The first truth, which Eschers visual both the surface and the representation, but artists

our eyes are eminently suited to guide us. character of the representation as a compelling

paradoxes illuminate is this piece- meal character knew better. Their rebellion against illusion came

The eyes alone can quickly resolve the question illusion. It is consistent with this reading that we

of picture reading. There is a clear limit to the into the open more than fifty years ago in those

of the real shape of a terrace, for we have a built- should look straight at the soles of the man's shoes

visual information we can process through any conundrums of cubism which lead our eye a

in predictor that tells us how any given shape will and that they should hide from us his feet and

given glance. This fits in well with the results of frustrating chase after guitars and bottles, teasing

change when seen from different angles. If one ankles which we imagine to be there. But the more

scientists who have studied this limit in the us with false clues only to entrap us in

moves straight toward a door, its shape will firmly we project the image of the whole figure

severely practical context of how many pointers a contradictions. It was by exploring these paradoxes

remain constant, but its size will increase at a into these marks on the paper, the more will we

pilot can read al a glance on an instrument panel. that artists wanted to discover new modes of

predictable rate. The object near the fringe of our instinctively expect it to respond to our usual

His capacity will, of course, vary according to organization.

vision, on the other hand, will be trans- formed in reality tests. A real figure would present different

training and experience, but the basic fact It is not only Escher who shows us their success.

shape in a regular and predict- able sequence that aspects to us if we moved sideways. But since

remains that the eye can take in much less at one Even abstract art owes some of its most interesting

we can study if we move a film camera in the same what we have in front of us is not a three-dimen-

glance than the layman imagines. But what about possibilities to the fascination of unresolved

direction. It is this melody of transformation that sional figure but only a flat piece of paper, the

the musician who can read an orchestral score ambiguities (Fig. 9). By presenting us with these

would be entirely different if we moved toward a expected melody of transformation fails to

with surprising ease and at amazing speed? Does scrambled codes the artist shocks us into realizing

flat or shallow perspective stage materialize.

he not have to take in information at an uncanny how much more there is in pictures than meets the

The decisive part that movement must play in What makes this experience remark- able in our

rate? Certainly the feat is admirable, but it is eye. THE END

our visual orientation has only recently been fully context is the confirmation it provides for our

only possible because the notes of the score,

brought out by psychologists, notably by James J. argument that the picture becomes a picture only if

unlike the pointer readings, are not random signs.

Gibson Here, too, a fresh alternative shocked us the marks

Music is an art that follows certain laws or rules

and enables the musician to scan the score with Fig. 9. Drawing. Josef Albers, 1958.

certain expectations. Though he cannot know

what to expect in the next bar, he knows at least

that many possibilities arc ruled out. Indeed, if

any of those occurred he would probably

disregard them as a misprint.

In reading a familiar language, of course, we

proceed in a similar way, look-

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Arrows of the Chace - a collection of scattered n the daily newspapers 1840-1880 IDari EverandArrows of the Chace - a collection of scattered n the daily newspapers 1840-1880 IBelum ada peringkat

- Modern Art and the Remaking of Human DispositionDari EverandModern Art and the Remaking of Human DispositionBelum ada peringkat

- Structure, Image, Ornament: Architectural Sculpture in the Greek WorldDari EverandStructure, Image, Ornament: Architectural Sculpture in the Greek WorldBelum ada peringkat

- Form as Revolt: Carl Einstein and the Ground of Modern ArtDari EverandForm as Revolt: Carl Einstein and the Ground of Modern ArtBelum ada peringkat

- Time’s Visible Surface: Alois Riegl and the Discourse on History and Temporality in Fin-de-Siècle ViennaDari EverandTime’s Visible Surface: Alois Riegl and the Discourse on History and Temporality in Fin-de-Siècle ViennaPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1)

- A History of Arcadia in Art and Literature: Volume I: Earlier RenaissanceDari EverandA History of Arcadia in Art and Literature: Volume I: Earlier RenaissanceBelum ada peringkat

- Wonder and Science: Imagining Worlds in Early Modern EuropeDari EverandWonder and Science: Imagining Worlds in Early Modern EuropePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (2)

- Claes Oldenburg: Soft Bathtub (Model) - Ghost Version by Claes OldenburgDokumen2 halamanClaes Oldenburg: Soft Bathtub (Model) - Ghost Version by Claes OldenburgjovanaspikBelum ada peringkat

- Ten Reasons Why E. H. Gombrich Remains Central To Art HistoryDokumen11 halamanTen Reasons Why E. H. Gombrich Remains Central To Art HistoryvladijanBelum ada peringkat

- Magdalena AbakanowiczDokumen1 halamanMagdalena AbakanowiczadinaBelum ada peringkat

- Balla and Depero The Futurist Reconstruction of The UniverseDokumen3 halamanBalla and Depero The Futurist Reconstruction of The UniverseRoberto ScafidiBelum ada peringkat

- Solid Objects: Modernism and the Test of ProductionDari EverandSolid Objects: Modernism and the Test of ProductionPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (3)

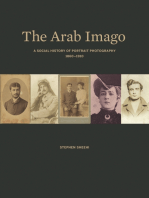

- The Arab Imago: A Social History of Portrait Photography, 1860–1910Dari EverandThe Arab Imago: A Social History of Portrait Photography, 1860–1910Belum ada peringkat

- Greek Sculpture: A Collection of 16 Pictures of Greek Marbles (Illustrated)Dari EverandGreek Sculpture: A Collection of 16 Pictures of Greek Marbles (Illustrated)Belum ada peringkat

- E.H. Gombrich - The Wit of Saul Steinberg PDFDokumen5 halamanE.H. Gombrich - The Wit of Saul Steinberg PDFRicardo HenriqueBelum ada peringkat

- Edward Hopper and American Solitude - The New YorkerDokumen8 halamanEdward Hopper and American Solitude - The New YorkerCosimo Dell'OrtoBelum ada peringkat

- Branden-W-Joseph-RAUSCHENBERG White-on-White PDFDokumen33 halamanBranden-W-Joseph-RAUSCHENBERG White-on-White PDFjpperBelum ada peringkat

- Becoming Henry Moore Leaflet PDFDokumen8 halamanBecoming Henry Moore Leaflet PDFYoshitomo MoriokaBelum ada peringkat

- Thomas Demand Image VoleeDokumen1 halamanThomas Demand Image VoleeArtdata100% (1)

- Art For Truth SakeDokumen16 halamanArt For Truth Sakehasnat basir100% (1)

- W. J. T. Mitchell: What Do Pictures WantDokumen7 halamanW. J. T. Mitchell: What Do Pictures WantDamla TamerBelum ada peringkat

- W. J. T. MitchellDokumen4 halamanW. J. T. MitchellFernando Maia da CunhaBelum ada peringkat

- Eskenazi School Faculty Staff Halaby StatementDokumen2 halamanEskenazi School Faculty Staff Halaby StatementIndiana Public Media NewsBelum ada peringkat

- Chance ImagesDokumen11 halamanChance ImagesRomolo Giovanni CapuanoBelum ada peringkat

- Walter Benjamin ArtDokumen436 halamanWalter Benjamin ArtEmelie KatesonBelum ada peringkat

- Frederick Sommer - An Exhibition of PhotographsDokumen32 halamanFrederick Sommer - An Exhibition of PhotographsStuart OringBelum ada peringkat

- Aesthetic AtheismDokumen5 halamanAesthetic AtheismDCSAWBelum ada peringkat

- Kenneth Clark PDFDokumen12 halamanKenneth Clark PDFsuryanandiniBelum ada peringkat

- Otto PachtDokumen18 halamanOtto PachtLorena AreizaBelum ada peringkat

- D'Alleva, Look: The Fundamentals of Art HistoryDokumen13 halamanD'Alleva, Look: The Fundamentals of Art HistoryEm100% (1)

- Szarkowski IntroductionToThePhotographersEyeDokumen7 halamanSzarkowski IntroductionToThePhotographersEyeBecky BivensBelum ada peringkat

- Buchholz Gallery NYC - The Blue Four - Feininger, Jawlensky, Kandinsky, Paul KleeDokumen12 halamanBuchholz Gallery NYC - The Blue Four - Feininger, Jawlensky, Kandinsky, Paul KleeshaktimargaBelum ada peringkat

- Photography Matters The Helsinki SchoolDokumen49 halamanPhotography Matters The Helsinki SchoolDavid Jaramillo KlinkertBelum ada peringkat

- Reflection On The Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and SculptureDokumen8 halamanReflection On The Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and SculptureMassimiliano FaillaBelum ada peringkat

- Katalog Konkrete Fotografie - PEBDokumen37 halamanKatalog Konkrete Fotografie - PEB̶N̶i̶i̶k̶u̶r̶a̶ K̶a̶o̶r̶u̶Belum ada peringkat

- Critics at Large - Excerpt From Ballerina - Sex, Scandal, and Suffering Behind The Symbol of Perfection by Deirdre Kelly PDFDokumen7 halamanCritics at Large - Excerpt From Ballerina - Sex, Scandal, and Suffering Behind The Symbol of Perfection by Deirdre Kelly PDFlord GABRIEL af ROSENSVERDBelum ada peringkat

- E. H. Gombrich - Art and Illusion (1984, Princeton Univ PR) - Libgen - lc-4 PDFDokumen15 halamanE. H. Gombrich - Art and Illusion (1984, Princeton Univ PR) - Libgen - lc-4 PDFYes Romo Quispe100% (1)

- Nude Kenneth Clark - PaperDokumen3 halamanNude Kenneth Clark - PaperCata Badawy YutronichBelum ada peringkat

- Symbolisme and IconologyDokumen5 halamanSymbolisme and IconologyWiLynn Ong50% (2)

- Art and GlobalizationDokumen306 halamanArt and GlobalizationAsad ShahzadBelum ada peringkat

- 20under40 LiebermanGuntherDokumen20 halaman20under40 LiebermanGunthergrinichBelum ada peringkat

- O'Keeffe Museum v. Fisk Univ Opinion, CT of Appeals 07.15.09Dokumen19 halamanO'Keeffe Museum v. Fisk Univ Opinion, CT of Appeals 07.15.09lawandarts100% (2)

- Year 2 - Final Piece EssayDokumen9 halamanYear 2 - Final Piece Essayapi-538905113Belum ada peringkat

- Tjclark Social History of Art PDFDokumen10 halamanTjclark Social History of Art PDFNicole BrooksBelum ada peringkat

- Victorian PhotographyDokumen28 halamanVictorian Photographyeisra100% (1)

- Rudolf Schindler, Dr. T.P. MArtin HouseDokumen21 halamanRudolf Schindler, Dr. T.P. MArtin HousebsakhaeifarBelum ada peringkat

- When Is Noise Speech? A Survey in Sonic Ambiguity: Freya Bailes and Roger T. DeanDokumen11 halamanWhen Is Noise Speech? A Survey in Sonic Ambiguity: Freya Bailes and Roger T. DeanΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- A Genetic Rule-Based Model of Expressive Performance For Jazz SaxophoneDokumen13 halamanA Genetic Rule-Based Model of Expressive Performance For Jazz SaxophoneΜέμνων Μπερδεμένος100% (1)

- The Laptop Orchestra As Classroom: Ge Wang, Dan Trueman, Scott Smallwood, and Perry R. CookDokumen12 halamanThe Laptop Orchestra As Classroom: Ge Wang, Dan Trueman, Scott Smallwood, and Perry R. CookΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- A Genetic Rule-Based Model of Expressive Performance For Jazz SaxophoneDokumen13 halamanA Genetic Rule-Based Model of Expressive Performance For Jazz SaxophoneΜέμνων Μπερδεμένος100% (1)

- A Classifi Er-Based Approach To Score - Guided Source Separation of Musical AudioDokumen9 halamanA Classifi Er-Based Approach To Score - Guided Source Separation of Musical AudioΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- Feature Set Patterns in Music: Darrell Conklin and Mathieu BergeronDokumen11 halamanFeature Set Patterns in Music: Darrell Conklin and Mathieu BergeronΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 32 3 RyynanenDokumen15 halaman32 3 RyynanenΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 32 1zhuDokumen17 halaman32 1zhuΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- When Is Noise Speech? A Survey in Sonic Ambiguity: Freya Bailes and Roger T. DeanDokumen11 halamanWhen Is Noise Speech? A Survey in Sonic Ambiguity: Freya Bailes and Roger T. DeanΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 33 1 Article02Dokumen11 halaman33 1 Article02Μέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 33 1 MirandaDokumen10 halaman33 1 MirandaΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- When Is Noise Speech? A Survey in Sonic Ambiguity: Freya Bailes and Roger T. DeanDokumen11 halamanWhen Is Noise Speech? A Survey in Sonic Ambiguity: Freya Bailes and Roger T. DeanΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 33 1 LaursonDokumen13 halaman33 1 LaursonΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 30 2dubnovDokumen21 halaman30 2dubnovΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 31 4stefikDokumen14 halaman31 4stefikΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 30 2valimakiDokumen13 halaman30 2valimakiΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- A Percussive Sound Synthesizer Based On Physical and Perceptual AttributesDokumen10 halamanA Percussive Sound Synthesizer Based On Physical and Perceptual AttributesΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 31.4products of InterestDokumen14 halaman31.4products of InterestΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 32 2 LehtonenDokumen14 halaman32 2 LehtonenΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 30 2collinsDokumen11 halaman30 2collinsΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 31 4nauertDokumen12 halaman31 4nauertΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 31 4hillDokumen12 halaman31 4hillΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 31 4stefikDokumen14 halaman31 4stefikΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 32 2 YehDokumen20 halaman32 2 YehΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 32 2 RobelDokumen12 halaman32 2 RobelΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 30 3aloupisDokumen10 halaman30 3aloupisΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 32 2 ZivanovicDokumen11 halaman32 2 ZivanovicΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 32 2 Article01Dokumen17 halaman32 2 Article01Μέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- An Interpretation of The Land of Cockaigne PDFDokumen2 halamanAn Interpretation of The Land of Cockaigne PDFΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- 30 3mountainDokumen12 halaman30 3mountainΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςBelum ada peringkat

- VT300 User ManualDokumen21 halamanVT300 User ManualLuvBelum ada peringkat

- WEEK 1, Grade 10Dokumen2 halamanWEEK 1, Grade 10Sheela BatterywalaBelum ada peringkat

- Aluminum: DR 900 Analytical ProcedureDokumen4 halamanAluminum: DR 900 Analytical Procedurewulalan wulanBelum ada peringkat

- University of Cambridge International Examinations General Certificate of Education Advanced LevelDokumen4 halamanUniversity of Cambridge International Examinations General Certificate of Education Advanced LevelHubbak KhanBelum ada peringkat

- Acuvim II Profibus Modules Users Manual v1.10Dokumen36 halamanAcuvim II Profibus Modules Users Manual v1.10kamran719Belum ada peringkat

- Business Process MappingDokumen14 halamanBusiness Process MappinghanxinBelum ada peringkat

- Learning MenuDokumen8 halamanLearning Menuapi-464525668Belum ada peringkat

- KVS - Regional Office, JAIPUR - Session 2021-22Dokumen24 halamanKVS - Regional Office, JAIPUR - Session 2021-22ABDUL RAHMAN 11BBelum ada peringkat

- K20 Engine Control Module X3 (Lt4) Document ID# 4739106Dokumen3 halamanK20 Engine Control Module X3 (Lt4) Document ID# 4739106Data TécnicaBelum ada peringkat

- 307-01 Automatic Transmission 10 Speed - Description and Operation - DescriptionDokumen12 halaman307-01 Automatic Transmission 10 Speed - Description and Operation - DescriptionCARLOS LIMADABelum ada peringkat

- Periodic Table and AtomsDokumen5 halamanPeriodic Table and AtomsShoroff AliBelum ada peringkat

- Type 85 Di Box DatasheetDokumen2 halamanType 85 Di Box DatasheetmegadeBelum ada peringkat

- ADO NET Tutorial - 16Dokumen18 halamanADO NET Tutorial - 16Fenil Desai100% (1)

- ProjectDokumen6 halamanProjecthazimsyakir69Belum ada peringkat

- GTG - TFA Belt DrivenDokumen2 halamanGTG - TFA Belt Drivensuan170Belum ada peringkat

- Thermal Breakthrough Calculations To Optimize Design of Amultiple-Stage EGS 2015-10Dokumen11 halamanThermal Breakthrough Calculations To Optimize Design of Amultiple-Stage EGS 2015-10orso brunoBelum ada peringkat

- PRD Doc Pro 3201-00001 Sen Ain V31Dokumen10 halamanPRD Doc Pro 3201-00001 Sen Ain V31rudybestyjBelum ada peringkat

- PassivityDokumen15 halamanPassivitySmarties AcademyBelum ada peringkat

- EC 201 Network TheoryDokumen2 halamanEC 201 Network TheoryJoseph JohnBelum ada peringkat

- Projector Spec 8040Dokumen1 halamanProjector Spec 8040Radient MushfikBelum ada peringkat

- T0000598REFTRGiDX 33RevG01052017 PDFDokumen286 halamanT0000598REFTRGiDX 33RevG01052017 PDFThanhBelum ada peringkat

- Optimization of Decarbonization On Steel IndustryDokumen28 halamanOptimization of Decarbonization On Steel Industrymsantosu000Belum ada peringkat

- Solenoid ValveDokumen76 halamanSolenoid ValveazlanBelum ada peringkat

- Implant TrainingDokumen5 halamanImplant Trainingrsrinath91Belum ada peringkat

- Attention Gated Encoder-Decoder For Ultrasonic Signal DenoisingDokumen9 halamanAttention Gated Encoder-Decoder For Ultrasonic Signal DenoisingIAES IJAIBelum ada peringkat

- Illiquidity and Stock Returns - Cross-Section and Time-Series Effects - Yakov AmihudDokumen50 halamanIlliquidity and Stock Returns - Cross-Section and Time-Series Effects - Yakov AmihudKim PhượngBelum ada peringkat

- Product Specifications: Handheld Termination AidDokumen1 halamanProduct Specifications: Handheld Termination AidnormBelum ada peringkat

- RomerDokumen20 halamanRomerAkistaaBelum ada peringkat

- Nomad Pro Operator ManualDokumen36 halamanNomad Pro Operator Manualdavid_stephens_29Belum ada peringkat

- HydrocarbonsDokumen5 halamanHydrocarbonsClaire Danes Tabamo DagalaBelum ada peringkat