Empathy in The Workplace

Diunggah oleh

sritha_87Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Empathy in The Workplace

Diunggah oleh

sritha_87Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

WHITE PAPER

Empathy in the Workplace

A Tool for Effective Leadership*

By: William A. Gentry, Todd J. Weber, and Golnaz Sadri

*This white paper is based on a poster that was presented at

the Society of Industrial Organizational Psychology Conference,

New York, New York, April 2007.

Contents

Introduction 1

Empathy and Performance: Whats the Connection? 2

The Research 3

The Findings 4

Empathy Can Be Learned 6

Conclusion 9

References 10

About the Authors 11

Introduction

A top priority for many organizations is With such high stakes, talent management

to look beyond traditional strategies for and human resource professionals as well

management development and recruitment as senior executives are pursuing multiple

to create a cadre of leaders capable of strategies for developing more effective

moving the company forward. managers and leaders.

And no wonder. Ineffective managers Managers, too, may be surprised that so

are expensive, costing organizations many of their peers are underperforming.

millions of dollars each year in direct and Its a smart move for individual managers,

indirect costs. Surprisingly, ineffective then, to figure out how they rank and what

managers make up half of the todays skills are needed to improve their chances

organizational management pool, of success.

according to a series of studies (see Gentry,

2010; Gentry & Chappelow, 2009). One of those skills, perhaps unexpectedly,

is empathy.

2016 Center for Creative Leadership. All rights reserved. 1

Empathy and Performance:

Whats the Connection?

Empathy is the ability to experience and relate Empathy is one factor in relationships. For

to the thoughts, emotions, or experience of several years, research and work with leaders

others. Empathy is more than simple sympathy, by the Center for Creative Leadership (CCL)

which is being able to understand and support has shown that the nature of leadership

others with compassion or sensitivity. is shifting, placing a greater emphasis on

building and maintaining relationships.

Empathy is a construct that is fundamental Leaders today need to be more person-

to leadership. Many leadership theories focused and be able to work with those

suggest the ability to have and display not just in the next cubicle, but also with

empathy is an important part of leadership. those in other buildings, or other countries.

Transformational leaders need empathy in For instance, past CCL research such as the

order to show their followers that they care Changing Nature of Leadership or Leadership

for their needs and achievement (Bass, 1985). Gap or Leadership Across Difference show that

Authentic leaders also need to have empathy leaders now need to lead people, collaborate

in order to be aware of others (Walumbwa, with others, be able to cross organizational

Avolio, Gardner, Wernsing, & Peterson, 2008). and cultural boundaries and need to create

Empathy is also a key part of emotional shared direction, alignment, and commitment

intelligence that several researchers believe is between social groups with very different

critical to being an effective leader (Bar-On & histories, perspectives, values, and cultures. It

Parker, 2000; George, 2000; Goleman, 1995; stands to reason that empathy would go a long

Salovey & Mayer, 1990). way toward meeting these people-oriented

managerial and leadership requirements.

To understand if empathy has an influence on

a managers job performance, CCL analyzed

data from 6,731 managers from 38 countries.

Key findings of the study are:

Empathy is positively related to job

performance.

Empathy is more important to job

performance in some cultures than others.

2 2016 Center for Creative Leadership. All rights reserved.

The Research

To better understand how leaders can be effective in their jobs,

CCL conducted a study to address two key issues:

1. Successful Job Performance:

Is empathy needed to be successful in a leaders job?

2. Cross-Cultural Issues:

Does empathy influence success more in some cultures than others?

To answer these questions, we analyzed leaders Questions were measured on a 5-point scale with

empathy based on their behavior. Having empathy 1 = not at all to 5 = to a very great extent.

is not the same thing as demonstrating empathy.

Conveying empathic emotion is defined as the Each manager in the sample also had one boss rate

ability to understand what others are feeling (Duan, them on three items that measured job performance:

2000; Duan & Hill, 1996; Goleman, 2006), the

ability to actively share emotions with others, and How would you rate this persons performance in

passively experiencing the feelings of others (Kellett, his/her present job (1 = among the worst to

Humphrey, & Sleeth, 2006) in order to be effective. 5 = among the best);

Where would you place this person as a leader

We searched CCLs database and identified a sample compared to other leaders inside and outside your

of 6,731 leaders from 38 countries. (See Table 1 on organization (1 = among the worst to 5 = among the

page 11 for the number of managers from each best); and

country and Table 2 on page 12 for demographic

What is the likelihood that this person will derail

information.) These leaders had at least three

(i.e., plateau, be demoted, or fired) in the next five

subordinates rate them on the display of empathic

years as a result of his/her actions or behaviors as a

emotion as measured by CCLs Benchmarks

manager? (1 = not at all likely to 5 = almost certain).

360-degree instrument. Subordinates rated managers

on four items:

Is sensitive to signs of overwork in others.

Shows interest in the needs, hopes, and dreams of

other people.

Is willing to help an employee with personal

problems.

Conveys compassion toward them when other

people disclose a personal loss.

2016 Center for Creative Leadership. All rights reserved. 3

The Findings

Our results reveal that empathy is positively related and agree that power should be stratified and

to job performance. Managers who show more concentrated at higher levels of an organization

empathy toward direct reports are viewed as better or government (House & Javidan, 2004, p. 12).

performers in their job by their bosses. Cultures with high power distance believe that

power should be concentrated at higher levels.

The findings were consistent across the sample:

Such cultures believe that power provides harmony,

empathic emotion as rated from the leaders

social order, and role stability. China, Egypt, Hong

subordinates positively predicts job performance

Kong, Malaysia, New Zealand, Poland, Singapore,

ratings from the leaders boss.

and Taiwan are all considered high power-distance

While empathy is clearly important to the full sample countries (see Table 1 on page 11).

and across all the countries in the study, the research

In high power-distance cultures, paternalism

shows that the relationship between empathy and

characterizes leader-subordinate relationships,

performance is stronger in some cultures more than

where a leader will assume the role of a parent and

others.

feel obligated to provide support and protection

We found that the positive relationship between to subordinates under his or her care (Yan &

empathic emotion and performance is greater for Hunt, 2005). The results of our study suggest that

managers living in high power-distance countries, empathic emotion plays an important role in

making empathy even more critical to performance creating this paternalistic climate of support and

for managers operating in those cultures. protection to promote successful job performance

in these high power-distance cultures.

Power distance is defined as the degree to which

members of an organization or society expect

4 2016 Center for Creative Leadership. All rights reserved.

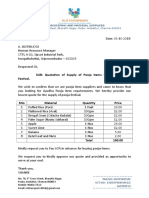

Figure 1

1.17

0.09

Performance

-0.99

-2.08

-3.16

-2.64 -1.68 -0.73 0.22 1.18

Empathic Emotion

Columbia (Low Power-Distance)

New Zealand (High Power-Distance)

Comparing Empathy Across Cultures. As the example below

shows, empathy is more strongly tied to performance in New

Zealand (a high power-distance culture) than it is in Colombia

(a low power-distance culture). This distinction was found to

be consistent when evaluating the importance of empathy in

38 low, mid and high power-distance countries.

2016 Center for Creative Leadership. All rights reserved. 5

Empathy Can Be Learned

To improve their performance and effectiveness, leaders may need to develop the capability to

demonstrate empathy.

Some people naturally exude empathy and have an advantage over their peers who have difficulty

expressing empathy. Most leaders fall in the middle and are sometimes or somewhat empathetic.

Fortunately, empathy is not a fixed trait. It can be learned (Shapiro, 2002). If given enough time and

support, leaders can develop and enhance their empathy skills through coaching, training, or

developmental opportunities and initiatives.

Organizations can encourage a more empathetic workplace and help managers improve their empathy

skills in a number of simple ways:

Talk about empathy. Let managers know that empathy

matters. Though task-oriented skills like monitoring, planning,

controlling and commanding performance or making the

numbers are important, understanding, caring, and developing

others is just as important, if not more important, particularly

in todays workforce. Explain that giving time and attention

to others fosters empathy, which in turn, enhances your

performance and improves your perceived effectiveness.

Specific measures of empathy can be used (such as the

Benchmarks assessment used in this research) to give feedback

about individual and organizational capacity for empathy.

6 2016 Center for Creative Leadership. All rights reserved.

Teach listening skills. To understand others and sense what they are

feeling, managers must be good listeners. Skilled listeners let others know

that they are being heard, and they express understanding of concerns and

problems. When a manager is a good listener, people feel respected and

trust can grow. Specific listening skills include:

Listen to hear the meaning behind what others are saying. Pay particular attention to

nonverbal cues. Emotion expressed nonverbally may be more telling than the words people

speak. Focus on tone of voice, pace of speech, facial expressions, and gestures.

Be an active listener. Active listening is a persons willingness and ability to hear and

understand someone else. Active listeners are able to reflect the feelings expressed and

summarize what they are hearing. There are several key skills all active listeners share:

They pay attention to others.

They hold judgment.

They reflect by paraphrasing information. They may say something like

What I hear you saying is . . .

They clarify if they dont understand what was said, like What are your thoughts on . . .

or I dont quite understand what you are saying, could you repeat that . . .

They summarize, giving a brief restatement on what they just heard.

They share. They are active participants in the dialogue by saying, for example, That

sounds like something I went through.

2016 Center for Creative Leadership. All rights reserved. 7

Encourage genuine perspective taking. Support global managers. The ability to be

Managers consistently should put themselves in the empathetic is especially important for leaders working

other persons place. As Atticus Finch in Harper Lees in global organizations or across cultural boundaries

To Kill a Mockingbird famously said: You can never (Alon & Higgins, 2005) or for leaders getting ready for

understand someone unless you understand their expatriate assignments (Harris & Moran, 1987; Jokinen,

point of view, climb in that persons skin, or stand 2005; Mendez-Russell, 2001). Working across cultures

and walk in that persons shoes. For managers, this requires managers to understand people who

includes taking into account the personal experience or have very different perspectives and experiences.

perspective of their employees. It also can be applied Empathy generates an interest in and appreciation for

to solving problems, managing conflicting, or driving others, paving the way to more productive working

innovation. relationships.

Cultivate compassion. Support managers who Managers would also benefit from knowing if the

care about how someone else feels or consider the power-distance attributes are high, medium, or low

effects that business decisions have on employees, in the countries in which they operate. The higher

customers, and communities. Go beyond the the power-distance needs, the more emphasis and

standard-issue values statement and allow time for attention should be given to teaching (and practicing)

compassionate reflection and response. empathy.

When managers increase their awareness and

understanding of empathy (particularly in their cultural

context), they can identify behaviors they can improve

and situations where showing their empathy could

make a difference. As managers hone their empathy

skills through listening, perspective taking, and

compassion, they are improving their leadership

effectiveness and increasing the chances of success

in the job.

8 2016 Center for Creative Leadership. All rights reserved.

Conclusion

The opportunity costs of keeping a manager who underperforms are often weighed

against the costs of recruiting, hiring, and getting the new manager up to speed. But

with 50% of managers seen as poor performers or failures in their jobs (Gentry,

2010; Gentry and Chappelow, 2009) organizations must recognize the value in

improving the managerial and leadership skills within their existing employee

base. As one of CCLs efforts to better understand the skills and behaviors leaders need

to be effective in various parts of the world, this study examined the role that empathy

plays in effective leadership.

This study found that the ability to understand what others are feeling is a skill that

clearly contributes to effective leadership. In some cultures, the connection between

empathy and performance is particularly striking, placing an even greater value on

empathy as a leadership skill.

The reasons behind the strong correlation of empathy and effectiveness were not

evaluated in this study. We presume, however, that empathetic leaders are assets

to organizations, in part, because they are able to effectively build and maintain

relationshipsa critical part of leading organizations anywhere in the world.

2016 Center for Creative Leadership. All rights reserved. 9

References

Alon, I., & Higgins, J. M. (2005). Global leadership success through emotional and cultural intelligences. Business Horizons, 48,

501512.

Bar-On, R., & Parker, J. D. A. (2000). The handbook of emotional intelligence. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc.

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press.

Carl, D., Gupta, V., & Javidan, M. (2004). Power distance. In R. J. House, P. J. Hanges, M. Javidan, P. W. Dorfman, & V. Gupta (Eds.),

Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies (pp. 513563). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Duan, C. (2000). Being empathic: The role of motivation to empathize and the nature of target emotions. Motivation and

Emotion, 24, 2949.

Duan, C., & Hill, C. E. (1996). The current state of empathy research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43, 261274.

Gentry, W. A. (2010). Managerial derailment: What it is and how leaders can avoid it. In E. Biech (Ed.), ASTD leadership handbook

(pp. 311324). Alexandria, VA: ASTD Press.

Gentry, W. A., & Chappelow, C. T. (2009). Managerial derailment: Weaknesses that can be fixed. In R. B. Kaiser (Ed.), The perils of

accentuating the positives (pp. 97113). Tulsa, OK: HoganPress.

George, J. M. (2000). Emotions and leadership: The role of emotional intelligence. Human Relations, 53, 10271055.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Dell.

Goleman, D. (2006). Working with emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Dell.

Harris, P. R., & Moran, R. T. (1987). Managing cultural differences. Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing Company.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study

of 62 societies, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

House, R. J., & Javidan, M. (2004). Overview of GLOBE. In R. J. House, P. J. Hanges, M. Javidan, P. W. Dorfman, & V. Gupta (Eds.),

Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies (pp. 513563). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Jokinen, T. (2005). Global leadership competencies: A review and discussion. Journal of European Industrial Training, 29, 199218.

Kellett, J. B., Humphrey, R. H., & Sleeth, R. G. (2006). Empathy and the emergence of task and relations leaders. Leadership

Quarterly, 17, 146162.

Mendez-Russell, A. (2001). Diversity leadership. Executive Excellence, 18, 16.

Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9, 185211.

Shaprio, J. (2002). How do physicians teach empathy in the primary care setting? Academic Medicine, 77, 323328.

Walumbwa, F. O., Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Wernsing, T. S., & Peterson, S. J. (2008). Authentic leadership: Development and

validation of a theory-based measure. Journal of Management, 34, 89126.

Yan, J., & Hunt, J. G. (2005). A cross cultural perspective on perceived leadership effectiveness. International Journal of Cross

Cultural Management, 5, 4966.

10 2016 Center for Creative Leadership. All rights reserved.

Table 1

Number of Managers within Each Country for the Present Study

Country n Power Distance

Argentina 53 Low

Australia 378 Medium

Austria 39 Low

Brazil 94 Low

Canada 875 Medium

China 68 High

Columbia 30 Low

Denmark 72 Medium

Egypt 66 High Table 2

Finland 39 Low Demographics of the Managers

France 244 Medium

Germany 274 Medium Variable %

Greece 27 Low Gender

Hong Kong 54 High Male 74.0%

India 235 Medium Female 26.0%

Indonesia 80 Medium

Ireland 144 Medium Age

Italy 66 Low 2634 16.38%

Japan 58 Medium 3544 52.24%

Malaysia 48 High 4554 28.42%

Mexico 229 Medium 5564 2.96%

Netherlands 334 Low

New Zealand 192 High Organization Level

Philippines 85 Medium First Level 1.72%

Poland 52 High Middle Level 19.49%

Portugal 37 low Upper Middle Level 48.31%

Russia 33 Medium Executive Level 26.46%

Singapore 387 Medium Top Level 4.01%

South Korea 75 Medium

Spain 278 Low

Sweden 64 Medium

Switzerland 86 Medium

Taiwan 38 High

Thailand 44 Medium

Turkey 58 Low

United Kingdom 865 Medium

United States 900 Medium

Venezuela 30 Low

Note: Classification of countries as being in High, Medium, and Low power-

distance cultures came from the chapter written by Carl Gupta, and Javidan in the

House et al. book entitled Culture, Leadership and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of

62 Societies. For the purposes of this table, countries in Band A and B in the book

are high (greater power-distance), Band C is medium, and Band D and E are low

(low power-distance).

2016 Center for Creative Leadership. All rights reserved. 11

12 2016 Center for Creative Leadership. All rights reserved.

About the Authors

William A. (Bill) Gentry, PhD, is a senior research Todd J. Weber, PhD, is a postdoctoral research

scientist and coordinator of internships and postdocs associate in the College of Business and

in Research, Innovation, and Product Development Administration at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

at the Center for Creative Leadership (CCL) in A former intern and postdoctoral research fellow at

Greensboro, NC. He also trains the Assessment CCL, Todds research interests are in international

Certification Workshop and Maximizing Your management, leadership, and organizational behavior.

Leadership Potential programs at CCL and has

been an adjunct professor at several colleges Golnaz Sadri, PhD, is a professor of management

and universities. Bill has more than 70 academic at California State University, Fullerton, specializing

presentations, has been featured in more than 50 in organizational behavior. She has expertise in

Internet and newspaper outlets, and has published organization culture, cross-cultural differences in work

more than 40 peer-reviewed articles on leadership and behavior, occupational stress, communication, and

organizational psychology, including the areas of first- motivation. She is an adjunct coach for CCL.

time management, multisource (360) research, survey

development and analysis, leadership and leadership

development across cultures, leader character and

integrity, mentoring, managerial derailment, multilevel

measurement, and in the area of organizational

politics and political skill in the workplace. He also

studies nonverbal behavior and its application to

effective leadership and communication, particularly in

political debates. Bill holds a BA degree in psychology

and political science from Emory University and an MS

and PhD in industrial-organizational psychology from

the University of Georgia. Bill frequently posts written

and video blogs about his research in leadership

(usually connecting it with sports, music, and (pop

culture) on CCLs Leading Effectively blog.

To learn more about this topic or the Center for Creative Leaderships programs and products,

please contact our Client Services team.

+1 800 780 1031 +1 336 545 2810 info@ccl.org

2016 Center for Creative Leadership. All rights reserved. 13

The Center for Creative Leadership (CCL) is a top-ranked,

global provider of leadership development. By leveraging

the power of leadership to drive results that matter most

to clients, CCL transforms individual leaders, teams,

organizations and society. Our array of cutting-edge

solutions is steeped in extensive research and experience

gained from working with hundreds of thousands of

leaders at all levels. Ranked among the worlds Top 5

providers of executive education by the Financial Times

and in the Top 10 by Bloomberg Businessweek, CCL has

offices in Greensboro, NC; Colorado Springs, CO; San

Diego, CA; Brussels, Belgium; Moscow, Russia; Addis

Ababa, Ethiopia; Johannesburg, South Africa; Singapore;

Gurgaon, India; and Shanghai, China.

CCL - Americas CCL - Europe, Middle East, Africa CCL - Asia Pacific

www.ccl.org www.ccl.org/emea www.ccl.org/apac

+1 800 780 1031 (US or Canada)

+1 336 545 2810 (Worldwide) Brussels, Belgium Singapore

info@ccl.org +32 (0) 2 679 09 10 +65 6854 6000

ccl.emea@ccl.org ccl.apac@ccl.org

Greensboro, North Carolina

+1 336 545 2810 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Gurgaon, India

+251 118 957086 +91 124 676 9200

Colorado Springs, Colorado LBB.Africa@ccl.org cclindia@ccl.org

+1 719 633 3891

Johannesburg, South Africa Shanghai, China

San Diego, California +27 (11) 783 4963 +86 21 6881 6683

+1 858 638 8000 southafrica.office@ccl.org ccl.china@ccl.org

Moscow, Russia

+7 495 662 31 39

ccl.cis@ccl.org

Affiliate Locations: Seattle, Washington Seoul, Korea College Park, Maryland Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Ft. Belvoir, Virginia Kettering, Ohio Huntsville, Alabama San Diego, California St. Petersburg, Florida

Peoria, Illinois Omaha, Nebraska Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan Mt. Eliza, Victoria, Australia

Center for Creative Leadership and CCL are registered trademarks owned by the Center for Creative Leadership.

2016 Center for Creative Leadership. All rights reserved.

Issued November 2011/Reprinted February 2016

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Mentor HandbookDokumen5 halamanMentor Handbookapi-519320173Belum ada peringkat

- MBM Competency Frameworks Soft Skills DAS 14-06-16Dokumen16 halamanMBM Competency Frameworks Soft Skills DAS 14-06-16hrhvdyBelum ada peringkat

- Topic 1 Effective Workplace CommunicationDokumen3 halamanTopic 1 Effective Workplace CommunicationCrisnelynBelum ada peringkat

- Module 1-MCDokumen111 halamanModule 1-MCDeep MalaniBelum ada peringkat

- Emotionnal Intelligence NDokumen26 halamanEmotionnal Intelligence Nrabin neupaneBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 1 The Nature and The Process of CommunicationDokumen31 halamanChapter 1 The Nature and The Process of CommunicationMiyamoto MusashiBelum ada peringkat

- List of Organizational and Social SkillsDokumen2 halamanList of Organizational and Social SkillsAndrei KolozsvariBelum ada peringkat

- Intrapersonal CommunicationDokumen37 halamanIntrapersonal Communicationdiannedelacruz1Belum ada peringkat

- Emotional Intelligence at WorkDokumen2 halamanEmotional Intelligence at WorkMohammad Golam Kibria100% (1)

- Peter Drucker - Leadership.strategyDokumen4 halamanPeter Drucker - Leadership.strategy27031293Belum ada peringkat

- Abraham Maslow SlideDokumen25 halamanAbraham Maslow SlideRaz RamliBelum ada peringkat

- Quiz Answer Job 3Dokumen4 halamanQuiz Answer Job 3Imani ImaniBelum ada peringkat

- Measuring Attitudes and ValuesDokumen6 halamanMeasuring Attitudes and ValuesLoreto Capitli MoralesBelum ada peringkat

- Path-Goal and The Situational Leadership TheoriesDokumen9 halamanPath-Goal and The Situational Leadership TheoriesMuhammad JavedBelum ada peringkat

- Training ManualDokumen13 halamanTraining ManualSZABelum ada peringkat

- Psychological Safety Work CultureDokumen24 halamanPsychological Safety Work CultureSagar PatilBelum ada peringkat

- Positive Psychology: Dr. Zafar AhmadDokumen25 halamanPositive Psychology: Dr. Zafar Ahmadtayyaba nazirBelum ada peringkat

- Powerpoint Presentation Lesson1bDokumen12 halamanPowerpoint Presentation Lesson1bSheryn Mae Mantaring Sadicon100% (1)

- Interpersonal Relationships: Increasing Interpersonal Success Through Self-AwarenessDokumen48 halamanInterpersonal Relationships: Increasing Interpersonal Success Through Self-Awarenessk_sriBelum ada peringkat

- Emotional Intelligence - Session 1 PDFDokumen4 halamanEmotional Intelligence - Session 1 PDFAnderson CastroBelum ada peringkat

- Team Mental Models and Team Performance - A Field Study of The Effects of Team Mental Model Similarity and AccuracyDokumen17 halamanTeam Mental Models and Team Performance - A Field Study of The Effects of Team Mental Model Similarity and AccuracyRaf BendenounBelum ada peringkat

- The Ultimate EducatorDokumen14 halamanThe Ultimate EducatorAlexander Antonio Ortega AlvarezBelum ada peringkat

- WPP Aunz Academy Booklet CMPSD2Dokumen45 halamanWPP Aunz Academy Booklet CMPSD2Mohd. ZeeshanBelum ada peringkat

- The Happiness Institute's Signature Strengths ListDokumen2 halamanThe Happiness Institute's Signature Strengths ListCzarPaguio50% (2)

- Final Mentoring ResourcesDokumen6 halamanFinal Mentoring Resourcessamknight2009Belum ada peringkat

- Pros and Cons of CriticismDokumen8 halamanPros and Cons of CriticismVincent Gaspar DomanaisBelum ada peringkat

- White Paper Org Change LeadershipDokumen6 halamanWhite Paper Org Change LeadershipBeshoy Girgis100% (1)

- Conflict Management: Levels of Conflict Views On Conflict Types of Conflict Methods To Manage CONFLICT Decision MakingDokumen29 halamanConflict Management: Levels of Conflict Views On Conflict Types of Conflict Methods To Manage CONFLICT Decision MakingSanjay Sharma100% (1)

- Blaming and Moral DisengagementDokumen12 halamanBlaming and Moral DisengagementV_Freeman100% (1)

- The Five Dysfunctions of A Team - Phil HolmesDokumen8 halamanThe Five Dysfunctions of A Team - Phil HolmesZeeshan Kazmi50% (2)

- Five Tips To Inspire First-Time Leaders (2016) by Lawrence - MAY 2020Dokumen12 halamanFive Tips To Inspire First-Time Leaders (2016) by Lawrence - MAY 2020Yoseph Haziel IsraelBelum ada peringkat

- 3 Emotional Intelligence Exercises 1-11-18 1Dokumen8 halaman3 Emotional Intelligence Exercises 1-11-18 1Buhvtai SuwanBelum ada peringkat

- Presentation On: Communication Skills: Submitted By: Rishabh NandaDokumen17 halamanPresentation On: Communication Skills: Submitted By: Rishabh NandaRishab NandaBelum ada peringkat

- My Leadership PhilosophyDokumen2 halamanMy Leadership PhilosophyCM Finance100% (1)

- Professional Networking Presentation To Cambodia Club 3-4-21Dokumen9 halamanProfessional Networking Presentation To Cambodia Club 3-4-21David PreeceBelum ada peringkat

- Teamwork, Psychological Safety, and Patient SafetyDokumen5 halamanTeamwork, Psychological Safety, and Patient SafetyMutiara100% (1)

- Guide PBLNeurodivergent StudentsDokumen26 halamanGuide PBLNeurodivergent StudentsMithunBelum ada peringkat

- Challenging Conversations and How To Manage ThemDokumen24 halamanChallenging Conversations and How To Manage ThemFlorina C100% (1)

- Module 6 - Trasaction AnalysisDokumen19 halamanModule 6 - Trasaction AnalysisGangadhar100% (1)

- AO E-Book2 OnlineDokumen16 halamanAO E-Book2 OnlineAna MarcelaBelum ada peringkat

- ENTJ - "The Commander": Entj in A NutshellDokumen2 halamanENTJ - "The Commander": Entj in A NutshellHải Nam100% (1)

- Talking About FeelingsDokumen7 halamanTalking About FeelingsJessicaBelum ada peringkat

- UnitVII Chapter14Presentation PDFDokumen15 halamanUnitVII Chapter14Presentation PDFraiedBelum ada peringkat

- How To Stop Worrying About What Other People Think of YouDokumen3 halamanHow To Stop Worrying About What Other People Think of YouBenedictBelum ada peringkat

- Building Trust in Collaborative Partnerships: Worksheet: Network Planning Technical AssistanceDokumen12 halamanBuilding Trust in Collaborative Partnerships: Worksheet: Network Planning Technical AssistanceJose Carlos Vasquez100% (1)

- Leading by DesignDokumen4 halamanLeading by DesignAndry WasesoBelum ada peringkat

- Per DevDokumen23 halamanPer DevNika BautistaBelum ada peringkat

- Body LanguageDokumen15 halamanBody Languagesafi516Belum ada peringkat

- Coaching and Feedback Job Aid For Managers: ObjectiveDokumen4 halamanCoaching and Feedback Job Aid For Managers: Objectiveapi-19967718100% (1)

- Effective Goal SettingDokumen17 halamanEffective Goal Settinglove careBelum ada peringkat

- Leadership, Membership and OrganizationDokumen14 halamanLeadership, Membership and OrganizationRenuka N. KangalBelum ada peringkat

- Interview With John WhitmoreDokumen5 halamanInterview With John WhitmoreOvidiuBelum ada peringkat

- Faculty Profile Erin MeyerDokumen2 halamanFaculty Profile Erin MeyermarianneBelum ada peringkat

- Categories of CommunicationDokumen5 halamanCategories of CommunicationRaj GamiBelum ada peringkat

- Self Efficacy Theory - PresentationDokumen5 halamanSelf Efficacy Theory - PresentationNaveed DaarBelum ada peringkat

- Empathy in The WorkplaceDokumen16 halamanEmpathy in The WorkplaceAli Baig50% (2)

- Chap 12... LeadershipDokumen17 halamanChap 12... LeadershipfariaBelum ada peringkat

- Article Leadership Success FactorsDokumen5 halamanArticle Leadership Success FactorsBartiBelum ada peringkat

- Leadership Module: Critical Thinking Critical Thinking: Authentic LeadershipDokumen6 halamanLeadership Module: Critical Thinking Critical Thinking: Authentic Leadershipsyeda salmaBelum ada peringkat

- Straton Composites (WPC) - CatalogueDokumen31 halamanStraton Composites (WPC) - Cataloguesritha_87100% (1)

- Why Is Digital AdvertisingDokumen4 halamanWhy Is Digital Advertisingsritha_87Belum ada peringkat

- காமாட்சி தாசன் தாத்தாDokumen1 halamanகாமாட்சி தாசன் தாத்தாsritha_87Belum ada peringkat

- Navaratri N Padasalai 2021-UpdateDokumen1 halamanNavaratri N Padasalai 2021-Updatesritha_87Belum ada peringkat

- India - Vaccination Roll Out PlanDokumen27 halamanIndia - Vaccination Roll Out PlanTmailBelum ada peringkat

- DocumentDokumen1 halamanDocumentsritha_87Belum ada peringkat

- Welcome To TANGEDCO Online Application Filing Portal For New Service ConnectionDokumen4 halamanWelcome To TANGEDCO Online Application Filing Portal For New Service Connectionsritha_87Belum ada peringkat

- Yajur Veda Avani Avittam or Upakarma and Gayathri JapamDokumen200 halamanYajur Veda Avani Avittam or Upakarma and Gayathri Japamnjaykumar90% (21)

- Shilpa Huchchannanavar, Et AlDokumen8 halamanShilpa Huchchannanavar, Et Alsritha_87Belum ada peringkat

- Varalakshmi Vratham Procedure PDFDokumen15 halamanVaralakshmi Vratham Procedure PDFLakshmi Rajagopalan100% (3)

- Agnihotra e Book1Dokumen23 halamanAgnihotra e Book1CA Sameir Sameir100% (1)

- Osfnd Gou: Do It Yourself Vaidik HavanDokumen42 halamanOsfnd Gou: Do It Yourself Vaidik Havansritha_87100% (1)

- Namma Toilet PPT PDFDokumen51 halamanNamma Toilet PPT PDFAlamandha Madhan KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Japa YogaDokumen153 halamanJapa YogaKartik VashishtaBelum ada peringkat

- K Legal Firn ProfileDokumen7 halamanK Legal Firn Profilesritha_87Belum ada peringkat

- ScreenerDokumen1 halamanScreenersritha_87Belum ada peringkat

- Peetch by Slidor (Windows)Dokumen45 halamanPeetch by Slidor (Windows)sritha_87Belum ada peringkat

- Rape CasesDokumen1 halamanRape Casessritha_87Belum ada peringkat

- R VDokumen24 halamanR Vsritha_87Belum ada peringkat

- Bala Tripura Sundari Stotram Tamil PDF File12212Dokumen13 halamanBala Tripura Sundari Stotram Tamil PDF File12212sritha_87Belum ada peringkat

- Editorial Guidelines:: Overall StyleDokumen2 halamanEditorial Guidelines:: Overall Stylesritha_87Belum ada peringkat

- Getting Started With OneDrive PDFDokumen9 halamanGetting Started With OneDrive PDFwiwit nurmaya sariBelum ada peringkat

- Rbi ActionDokumen1 halamanRbi Actionsritha_87Belum ada peringkat

- Sri Bala Mantra Siddhi Stavam - Mahakala SamhitaDokumen1 halamanSri Bala Mantra Siddhi Stavam - Mahakala Samhitakaumaaram100% (2)

- Font LogDokumen1 halamanFont Logsritha_87Belum ada peringkat

- Quotation Ayudha PoojaDokumen1 halamanQuotation Ayudha Poojasritha_87Belum ada peringkat

- Bala MediationDokumen80 halamanBala MediationkojoBelum ada peringkat

- Font LogDokumen1 halamanFont Logsritha_87Belum ada peringkat

- Airbnb Pitch DeckDokumen20 halamanAirbnb Pitch Decksritha_87Belum ada peringkat

- Touch Me There My LoveDokumen1 halamanTouch Me There My Lovesritha_87Belum ada peringkat

- Intro To LodgingDokumen63 halamanIntro To LodgingjaevendBelum ada peringkat

- Sjögren's SyndromeDokumen18 halamanSjögren's Syndromezakaria dbanBelum ada peringkat

- Inph 13Dokumen52 halamanInph 13kicaBelum ada peringkat

- Research Article: Old Sagay, Sagay City, Negros Old Sagay, Sagay City, Negros Occidental, PhilippinesDokumen31 halamanResearch Article: Old Sagay, Sagay City, Negros Old Sagay, Sagay City, Negros Occidental, PhilippinesLuhenBelum ada peringkat

- Cpar Q2 ReviewerDokumen2 halamanCpar Q2 ReviewerJaslor LavinaBelum ada peringkat

- PFASDokumen8 halamanPFAS王子瑜Belum ada peringkat

- Campos V BPI (Civil Procedure)Dokumen2 halamanCampos V BPI (Civil Procedure)AngeliBelum ada peringkat

- Grill Restaurant Business Plan TemplateDokumen11 halamanGrill Restaurant Business Plan TemplateSemira SimonBelum ada peringkat

- Strength Exp 2 Brinell Hardness TestDokumen13 halamanStrength Exp 2 Brinell Hardness Testhayder alaliBelum ada peringkat

- High-Performance Cutting and Grinding Technology For CFRP (Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastic)Dokumen7 halamanHigh-Performance Cutting and Grinding Technology For CFRP (Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastic)Dongxi LvBelum ada peringkat

- Assertiveness FinlandDokumen2 halamanAssertiveness FinlandDivyanshi ThakurBelum ada peringkat

- Right To Information: National Law University AND Judicial Academy, AssamDokumen20 halamanRight To Information: National Law University AND Judicial Academy, Assamsonu peterBelum ada peringkat

- Multiple ChoiceDokumen3 halamanMultiple ChoiceEfrelyn CasumpangBelum ada peringkat

- Basic OmDokumen242 halamanBasic OmRAMESH KUMARBelum ada peringkat

- Tiananmen1989(六四事件)Dokumen55 halamanTiananmen1989(六四事件)qianzhonghua100% (3)

- THM07 Module 2 The Tourist Market and SegmentationDokumen14 halamanTHM07 Module 2 The Tourist Market and Segmentationjennifer mirandaBelum ada peringkat

- Jamb Crk-Past QuestionDokumen59 halamanJamb Crk-Past QuestionFadele1981Belum ada peringkat

- 211-05 Steering Column SwitchesDokumen13 halaman211-05 Steering Column SwitchesMiguel AngelBelum ada peringkat

- 17-05-MAR-037-01 凱銳FCC Part15B v1Dokumen43 halaman17-05-MAR-037-01 凱銳FCC Part15B v1Nisar AliBelum ada peringkat

- Unleash Your Inner Millionaire: Achieve Wealth, Success, and Prosperity by Reprogramming Your Subconscious MindDokumen20 halamanUnleash Your Inner Millionaire: Achieve Wealth, Success, and Prosperity by Reprogramming Your Subconscious MindMariana PopaBelum ada peringkat

- Rapidjson Library ManualDokumen79 halamanRapidjson Library ManualSai Kumar KvBelum ada peringkat

- Accaf3junwk3qa PDFDokumen13 halamanAccaf3junwk3qa PDFTiny StarsBelum ada peringkat

- Social Studies 5th Grade Georgia StandardsDokumen6 halamanSocial Studies 5th Grade Georgia Standardsapi-366462849Belum ada peringkat

- Exeter: Durance-Class Tramp Freighter Medium Transport Average, Turn 2 Signal Basic Pulse BlueDokumen3 halamanExeter: Durance-Class Tramp Freighter Medium Transport Average, Turn 2 Signal Basic Pulse BlueMike MitchellBelum ada peringkat

- RMC No. 23-2007-Government Payments WithholdingDokumen7 halamanRMC No. 23-2007-Government Payments WithholdingWizardche_13Belum ada peringkat

- Goldilocks and The Three BearsDokumen2 halamanGoldilocks and The Three Bearsstepanus delpiBelum ada peringkat

- Principles of Cooking MethodsDokumen8 halamanPrinciples of Cooking MethodsAizelle Guerrero Santiago100% (1)

- BIM 360-Training Manual - MEP ConsultantDokumen23 halamanBIM 360-Training Manual - MEP ConsultantAakaara 3DBelum ada peringkat

- Bekic (Ed) - Submerged Heritage 6 Web Final PDFDokumen76 halamanBekic (Ed) - Submerged Heritage 6 Web Final PDFutvrdaBelum ada peringkat

- Rock Type Identification Flow Chart: Sedimentary SedimentaryDokumen8 halamanRock Type Identification Flow Chart: Sedimentary Sedimentarymeletiou stamatiosBelum ada peringkat