Res QB13

Diunggah oleh

Prerit SethiJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Res QB13

Diunggah oleh

Prerit SethiHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Quarterly Briefing

NSE Centre for Excellence in

Corporate Governance

April 2016 | No. 13

The Long and Short of Insider

Trading Regulation in India

Chief Contributor: Umakanth Varottil 1

Executive Summary

Regulation of insider trading has a significant role in preserving market integrity and ensuring fairness to

all shareholders.

The insider trading regulations in India have evolved over a period of time and have been considerably

strengthened;

Despite tightening, the enforcement of the regulations have witnessed a mixed track record;

The regulations have been subjected to a recent review, with the new version having taken effect in 2015;

As per the current regulations, the mere possession of inside information at the time of trading is sufficient

for a violation. The insider then carries the burden to prove to the contrary.

Such a rigorous approach is tempered by the availability of various defencesparticularly noteworthy

among them is the trading plan.

The current regulations as well as rulings by the Securities Appellate Tribunal (SAT) and various courts

have highlighted the need for companies to take a serious note of insider trading concerns.

Companies, insiders and other parties dealing with companies need to ensure compliance with the

regulations as well as codes of conduct to be established by companies and market intermediaries.

1

Associate Professor, National University of Singapore

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NSE. NSE does not guarantee the accuracy of the

information included in this document.

NSE Centre for Excellence in Corporate Governance

April 2016 | No. 13

I. Rationale for Insider Trading regulations

It is well known that high standards of corporate governance and transparency are essential to the development of capital

markets. The disclosure of information regarding a company enables investors to take decisions regarding investments

in securities of such a company. For prices of securities to accurately reflect relevant information about a company - an

essential precondition for efficient functioning of capital markets - such information should be equally available to all

market participants at the same time. Naturally, distortions occur in the market if company insiders possess superior in-

formation that they use to trade in the securities of their company, which is unavailable to the counterparties with whom

they trade or to the market generally. Hence, countries generally tend to enact laws that prohibit insider trading.

Aside from preserving capital market efficiency, there are other justifications too for regulating insider trading. Insider

trading causes unfairness to investors who possess inferior information, it undermines investor confidence and integrity

of the securities markets, and it is also regarded as theft or misappropriation of information. Yet, opponents of regulat-

ing insider trading wax eloquent about its virtues, including the fact that it may result in greater market efficiency and

operate as a form of compensating employees, thereby motivating them to generate greater corporate performance that

benefit all shareholders.

Despite some voices continuing to support insider trading, most countries prohibit insider trading in some form or the

other. The fairness objective seems to have trumped any perceived arguments in favour of insider trading. In fact, em-

pirical evidence suggests that "more stringent insider trading laws are generally associated with more dispersed equity

ownership, greater stock price accuracy and greater stock market liquidity".2 These would in turn facilitate better cor-

porate governance.

II. Evolution of Insider Trading regulations in India

From a practical perspective, insider trading is a significant concern particularly for public listed companies in several

situations. Selective information may be available to insiders within a company (such as its board of directors and sen-

ior officers as well as to external advisers). This could relate to negotiation of material contracts, information regarding

board meetings, financial results, dividend declaration and the like as well as significant corporate transactions such as

mergers and acquisitions, rights offerings and private placement of securities.

Over the years the regulations relating to insider trading and their enforcement have been substantially strengthened.

Soon after the establishment of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) in 1992, the SEBI (Prohibition of

Insider Trading) Regulations, 1992 were issued. Although the initial years did not witness much prosecution, SEBI did

initiate a high profile action against Hindustan Lever and a few of its directors for insider trading in connection with

the merger of Brooke Bond. SEBIs case was that Hindustan Lever had acquired shares of Brooke Bond prior to the

announcement of the merger, an act that amounted to insider trading. However, the appellate authority did not uphold

the charges, including on the ground that information regarding the possible merger was already in the public domain

at the time.

This and other difficulties encountered in the initial years caused SEBI to periodically expand the substantive provi-

sions for regulating insider trading through amendments to the 1992 regulations. Yet, there continued to be a shortfall

in terms of both design of the regulations and their enforcement. This was reflected in inconsistency in the interpretation

of various regulations by SEBI, the Securities Appellate Tribunal (SAT) and the various courts. Moreover, institutional

constraints such as the lack of a robust surveillance and investigative machinery meant that SEBI was successful in sus-

taining charges in only a few insider trading cases.

For these and other reasons, SEBI appointed a high level committee (HLC) for an overhaul of insider trading regulations,

and this committee issued its report in December 2013. Based on the HLC report, SEBI issued the SEBI (Prohibition of

Insider Trading) Regulations, 2015, which are currently in force. These regulations are intended to modernize the regime

for regulating insider trading and also address some of the implementation issues encountered in the two preceding dec-

ades. Some of the key definitions pertaining to Insider trading regulations are set out in Box 1.

2

Laura Nyantung Beny, Insider Trading Laws and Stock Markets Around the World: An Empirical Contribution to

the Theoretical Law and Economics Debate, (2007) Journal of Corporation Law 237, available at http://ssrn.com/

abstract=193070.

NSE Centre for Excellence in Corporate Governance 1

April 2016 | No. 13

Box 1: Key definitions pertaining to insider trading

Insider: a "connected person" or a person possessing or having access to unpublished price sensitive

information;

Connected person: one who has been associated with the company in any capacity such as a director,

officer or employee or in a contractual or fiduciary relationship with the company; and includes a list

of "deemed connected persons";

Unpublished price sensitive information (UPSI): any information relating to securities of a company

that is not generally available and, upon being available, is likely to materially affect the price of

the company's securities. It includes matters such as financial results, dividends, changes in capital

structure, significant corporate transactions and changes in key managerial personal.

Source: SEBI (Prohibition of Insider Trading) Regulations, 2015.

III. SEBI's Insider Trading Regulations

III.1 Offences under Insider Trading regime

The insider trading regime creates two types of offences:

One is a "trading" offence whereby an insider would be liable for trading while in possession of UPSI.

The other is a "communication" offence whereby an insider would be liable for disclosing UPSI to another

pe son, except if required "in furtherance of legitimate purposes, performance of duties or discharge of legal

obligations".3

The first offence merits some discussion. Through SEBI's regulations, India has adopted a strict stance towards insider

trading based on the "parity of information" approach. Under this approach, what matters is that the person trading is

in possession of inside information. It does not matter how that person obtained the information, i.e. deliberately or by

accident. This is very different from the approach taken in the United States (US) where insider trading becomes illegal

only if it accompanied by the breach of a fiduciary duty owed to the company, its shareholders or the source of the

information.

India's current policy regime is also sharply in contrast to what prevailed earlier. For instance, although the 1992

regulations required that an insider ought to have traded "on the basis of inside information" in order to be liable for a

violation, the regulations were subsequently amended to suggest that mere possession of inside information at the time

of trading was sufficient for a violation. The SAT interpreted the regulations such that a person in possession of inside

information is presumed to have traded "on the basis of", or to have "used", the information.4 The insider then carries

the burden to prove to the contrary. Such a rigorous approach is tempered by the availability of various defences, which

are discussed below.

III.2 Potential defences available under Insider trading regulations

Given the strict nature of insider trading regulation in India, the regime sets forth certain defences that enable parties to

carry on genuine transactions without necessarily being treated illegal (See box 2).

3

SEBI (Prohibition of Insider Trading) Regulations, 2015, reg. 3(1).

4

Chandrakala v. Adjudicating Officer, Securities and Exchange Board of India, Securities Appellate Tribunal (31 Janu-

ary 2012).

NSE Centre for Excellence in Corporate Governance 2

April 2016 | No. 13

Box 2: Potential defences available under Insider trading regulations in India

The following are defences available under the current regime for trading offences; in other words, the regime

provides immunity if the trades are of the following types:

Off-market inter se transfer between promoters who were in possession of the same UPSI;

In organisations, individuals who were in possession of UPSI were different from those making trad-

ing dec sions and where appropriate arrangements are in place to prevent communication of UPSI to

individuals making trading decisions (Chinese walls);

Trades that are pursuant to a trading plan.

Source: SEBI (Prohibition of Insider Trading) Regulations, 2015.

The defence relating to 'trading plans' allows insiders (particularly employees holding shares) to buy and sell the

companys shares, subject to certain conditions. Such a trading plan has been found to be necessary to facilitate, on a

regular basis, trading and monetizing of securities by insiders who may otherwise be unable to trade in securities of the

company. The logic appears to be that once a trading plan has been established by an insider without being in possession

of UPSI, then it does not matter if such insider subsequently comes into possession of UPSI because the decision to

trade has already been taken prior to that. The company is entitled to set up a trading plan pursuant to which insiders

may buy and sell shares. There is a cooling-off period of six months between the establishment of a trading plan and

commencement of trading under it. Moreover, trading is not allowed in the vicinity of the announcement of financial

results.

The concept of a trading plan would bring some certainty to insiders who may wish to trade. This is particularly so

because in several cases under the previous set of regulations, parties had adopted the argument before SEBI or SAT that

trades were carried out as part of their regular investment / divestment plans, not just in the company concerned but more

generally in respect of their other investments. This has often operated persuasively to suggest that the insiders were

not trading on the basis of UPSI. The trading plan mechanism has now formalized such an arrangement by imposing

more objective conditions. It remains to be seen, however, whether the trading plan will be utilised effectively, and

more importantly, not be subject to abuses. An apprehension, however, persists that the strict conditions laid down for

invoking the trading plan defence may arguably operate as a dampener.

Another defence that pertains to the communication offence applies whereby an insider is allowed to communicate UPSI

if it "is in furtherance of legitimate purposes, performance of duties or discharge of legal obligations".5 The scope of

a similar phrase has been interpreted in other jurisdictions such as the European Union; in India, it would however be

necessary to examine in detail what situations would legitimize a selective disclosure of information. Given that Indian

companies are generally substantially owned by promoters, issues could arise as to whether or when a disclosure of

information to a promoter or parent company would be "legitimate". One way to deal with some of these issues is for

corporate groups to devise policies to deal with intra-group disclosures of UPSI relating to listed companies.

III.3 Safe harbour provisions for due diligence - a significant issue

One issue that has exercised the minds of corporates and the regulators relates to whether a due diligence exercised can

be permitted when an acquirer takes up shares in a listed company. During the due diligence process, the acquirer may

come into possession of UPSI that has been disclosed by the company. This creates some incongruence because while

due diligence is an essential process to enable acquisition transactions that may be beneficial to shareholders, it results

in a potential violation of the insider trading regime. Hence, in the 2015 regulations, SEBI has introduced specific safe

harbour provisions that permit due diligence under controlled circumstances. The regime is bifurcated into two parts,

one where the acquisition results in a takeover offer for the company, and the other where there is no such offer.

5

SEBI (Prohibition of Insider Trading) Regulations, 2015, reg. 3(1).

NSE Centre for Excellence in Corporate Governance 3

April 2016 | No. 13

In case of a takeover offer, the acquirer is entitled to have access to UPSI to carry out due diligence. The justification for

this exception is that the acquirer makes an offer to buy shares from all shareholders who are entitled to equal treatment

in terms of price. Although there is no specific requirement that UPSI needs to be made public before the acquirer

acquires shares in the offer, necessary information needs to be disclosed to the shareholders as part of the offer in order

to enable them to make a decision on whether they should divest or retain their shareholdings.

In cases not involving a takeover offer, any UPSI disclosed by the company to an acquirer must be made generally

available at least two trading days prior to the proposed transaction. In either case, the transaction must be subject to the

fact that the acquirer shall keep the UPSI in confidence and shall not trade in the securities of the company prior to the

disclosure, and also that the board of directors of the company ought to come to a conclusion that the transaction is in the

interests of the company. This structure set forth in the insider trading regime reconciles the interests of acquirers (who

may wish to conduct due diligence) with those of other shareholders, as the acquirer must relinquish any informational

advantage (through a public disclosure) before it trades in the shares.

III.4 Aspects relating to evidence

The evidentiary aspects of insider trading are crucial, as they can determine the effectiveness of substantive regulation.

Often, there is no direct evidence in insider trading cases, and regulators are compelled to rely extensively on circumstantial

evidence. This makes the task of the regulators highly onerous. In India, given that insider trading is a serious offence,

the SAT has laid down a fairly significant burden on the regulator before an insider trading charge can be sustained.

Given this background, the explicit treatment by the 2015 regulations regarding the relative burdens of the regulators

and the insider is welcome.

The regulations provide that the burden on the regulator is to show that a person is an insider and that he or she was in

possession of UPSI at the time of trading. The burden then shifts to the person to show either that he or she is not an

insider or that any of the defences (See Box 2) is available. However, the regulations have refrained from specifying

greater details regarding the evidentiary burden as that is left to the facts of each individual case. While this approach

is helpful, a lot would depend on the manner in which the proposed regulations are implemented by SEBI and SAT. As

SAT considers insider trading to be a serious charge in the securities markets, the regulator's burden is quite heavy and

similar to one that is involved in a civil charge of fraud. 6

Moreover, since SAT's position has been somewhat ambivalent on the acceptability of only circumstantial evidence to

sustain an insider trading charge, the ability of SEBI to exercise its investigative powers for the collection of evidence

becomes important. In order to address these concerns, the Parliment in 2014 conferred additional powers on SEBI,

including the power to call for information and records in connection with any investigation or enquiry.

IV. Enforcement by SEBI

One of the ways to measure the robustness of enforcement of insider trading regulations is to analyse the data on cases

initiated and concluded by SEBI.

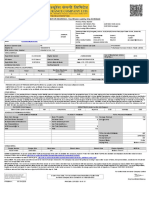

Table 1: Insider Trading Investigations by SEBI

2010-11 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 2014-15

Investigations Taken Up 28 24 11 13 10

Investigations Completed 15 21 14 13 15

Sources: SEBI, Handbook of Statistics on the Securities Market 2014; SEBI Annual Report 2014-15.

6

From a legal perspective, such a charge would be based on a higher degree of preponderance of probabilities.

NSE Centre for Excellence in Corporate Governance 4

April 2016 | No. 13

An analysis of the data in Table 1 shows that the number of investigations taken up is arguably small given the size of

India's capital markets and their liquidity. Moreover, the data relating to 'investigations completed' may not truly reflect

SEBI's track record of success as several of the actions initiated by SEBI over the years, including a few high profile

ones, were overturned on appeal.

V. Summary and conclusion

As we have seen, the substantive law relating to insider trading has been considerably strengthened over the years. SEBI

has also acquired greater enforcement powers, which it is likely to exercise given that insider trading can potentially

cause a serious dent on market integrity. Regulations issued by SEBI, their enforcement by SEBI as well as rulings by

SAT and various courts have highlighted the need for companies to take serious note of insider trading concerns. In any

event, companies and insiders would be well-advised to take precautions to not fall afoul of the legal regime.

Box 3: Some good practices to deal with Insider Trading

Adopt a code of conduct for disclosure of UPSI; ensure transparency generally by limiting selective

disclosures;

Adopt a code of conduct for trading by employees and other insiders;

Set up trading windows and approval mechanisms for designated trades;

Designate a compliance officer for administering the insider trading code of conduct;

Educate employees about the importance of insider trading regulation;

Limit the flow of information during sensitive periods such as a board meeting for consideration of financial

information or during negotiations for significant corporate transactions and the like;

Prepare for a situation involving leakage of sensitive information;

Establish defensive mechanisms, where applicable, such as Chinese walls and trading plans;

NSE Centre for Excellence in Corporate Governance 5

April 2016 | No. 13

References

SEBI (Prohibition of Insider Trading) Regulations, 2015;

SEBI, Report of the High Level Committee to Review the SEBI (Prohibition of Insider Trading Regulations, 1992 Under

the Chairmanship of N.K. Sodhi (7 December 2013);

Sandeep Parekh, Fraud, Manipulation and Insider Trading in the Indian Securities Markets (2014);

Suchismita Bose, Securities Market Regulations: Lessons from US and Indian Experience (http://ssrn.com/

abstract=1140107).

About NSE CECG

Recognizing the important role that stock exchanges play in enhancing corporate governance (CG) standards, NSE

has continually endeavoured to organize new initiatives relating to CG. To encourage best standards of CG among the

Indian corporates and to keep them abreast of the emerging and existing issues, NSE has set up a Centre for Excellence

in Corporate Governance (NSE CECG), which is an independent expert advisory body comprising eminent domain

experts, academics and practitioners. The Quarterly Briefing which offers an analysis of emerging CG issues, is brought

out by the NSE CECG as a tool for dissemination, particularly among the Directors of the listed companies.

NSE Centre for Excellence in Corporate Governance 6

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Abu Hamza Al Masri Wolf Notice of Compliance With SAMs AffirmationDokumen27 halamanAbu Hamza Al Masri Wolf Notice of Compliance With SAMs AffirmationPaulWolfBelum ada peringkat

- Perkins 20 Kva (404D-22G)Dokumen2 halamanPerkins 20 Kva (404D-22G)RavaelBelum ada peringkat

- Marine Lifting and Lashing HandbookDokumen96 halamanMarine Lifting and Lashing HandbookAmrit Raja100% (1)

- Methodical Pointing For Work of Students On Practical EmploymentDokumen32 halamanMethodical Pointing For Work of Students On Practical EmploymentVidhu YadavBelum ada peringkat

- Supergrowth PDFDokumen9 halamanSupergrowth PDFXavier Alexen AseronBelum ada peringkat

- The Rise of Populism and The Crisis of Globalization: Brexit, Trump and BeyondDokumen11 halamanThe Rise of Populism and The Crisis of Globalization: Brexit, Trump and Beyondalpha fiveBelum ada peringkat

- Loading N Unloading of Tanker PDFDokumen36 halamanLoading N Unloading of Tanker PDFKirtishbose ChowdhuryBelum ada peringkat

- Hayashi Q Econometica 82Dokumen16 halamanHayashi Q Econometica 82Franco VenesiaBelum ada peringkat

- MDOF (Multi Degre of FreedomDokumen173 halamanMDOF (Multi Degre of FreedomRicky Ariyanto100% (1)

- The Electricity Act - 2003Dokumen84 halamanThe Electricity Act - 2003Anshul PandeyBelum ada peringkat

- Labstan 1Dokumen2 halamanLabstan 1Samuel WalshBelum ada peringkat

- IdM11gR2 Sizing WP LatestDokumen31 halamanIdM11gR2 Sizing WP Latesttranhieu5959Belum ada peringkat

- GR L-38338Dokumen3 halamanGR L-38338James PerezBelum ada peringkat

- Hager Pricelist May 2014Dokumen64 halamanHager Pricelist May 2014rajinipre-1Belum ada peringkat

- Online Learning Interactions During The Level I Covid-19 Pandemic Community Activity Restriction: What Are The Important Determinants and Complaints?Dokumen16 halamanOnline Learning Interactions During The Level I Covid-19 Pandemic Community Activity Restriction: What Are The Important Determinants and Complaints?Maulana Adhi Setyo NugrohoBelum ada peringkat

- Course Specifications: Fire Investigation and Failure Analysis (E901313)Dokumen2 halamanCourse Specifications: Fire Investigation and Failure Analysis (E901313)danateoBelum ada peringkat

- Ludwig Van Beethoven: Für EliseDokumen4 halamanLudwig Van Beethoven: Für Eliseelio torrezBelum ada peringkat

- Environmental Auditing For Building Construction: Energy and Air Pollution Indices For Building MaterialsDokumen8 halamanEnvironmental Auditing For Building Construction: Energy and Air Pollution Indices For Building MaterialsAhmad Zubair Hj YahayaBelum ada peringkat

- 7 TariffDokumen22 halaman7 TariffParvathy SureshBelum ada peringkat

- A. The Machine's Final Recorded Value Was P1,558,000Dokumen7 halamanA. The Machine's Final Recorded Value Was P1,558,000Tawan VihokratanaBelum ada peringkat

- 199437-Unit 4Dokumen36 halaman199437-Unit 4Yeswanth rajaBelum ada peringkat

- Guide To Growing MangoDokumen8 halamanGuide To Growing MangoRhenn Las100% (2)

- Unit Process 009Dokumen15 halamanUnit Process 009Talha ImtiazBelum ada peringkat

- Dry Canyon Artillery RangeDokumen133 halamanDry Canyon Artillery RangeCAP History LibraryBelum ada peringkat

- Oracle FND User APIsDokumen4 halamanOracle FND User APIsBick KyyBelum ada peringkat

- Health Insurance in Switzerland ETHDokumen57 halamanHealth Insurance in Switzerland ETHguzman87Belum ada peringkat

- Production - The Heart of Organization - TBDDokumen14 halamanProduction - The Heart of Organization - TBDSakshi G AwasthiBelum ada peringkat

- Manual 40ku6092Dokumen228 halamanManual 40ku6092Marius Stefan BerindeBelum ada peringkat

- PeopleSoft Application Engine Program PDFDokumen17 halamanPeopleSoft Application Engine Program PDFSaurabh MehtaBelum ada peringkat

- MOTOR INSURANCE - Two Wheeler Liability Only SCHEDULEDokumen1 halamanMOTOR INSURANCE - Two Wheeler Liability Only SCHEDULESuhail V VBelum ada peringkat