Pediatric Contrast Upper GI PDF

Diunggah oleh

Mark M. AlipioJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Pediatric Contrast Upper GI PDF

Diunggah oleh

Mark M. AlipioHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

The American College of Radiology, with more than 30,000 members, is the principal organization of radiologists, radiation oncologists,

and clinical

medical physicists in the United States. The College is a nonprofit professional society whose primary purposes are to advance the science of radiology,

improve radiologic services to the patient, study the socioeconomic aspects of the practice of radiology, and encourage continuing education for

radiologists, radiation oncologists, medical physicists, and persons practicing in allied professional fields.

The American College of Radiology will periodically define new practice parameters and technical standards for radiologic practice to help advance the

science of radiology and to improve the quality of service to patients throughout the United States. Existing practice parameters and technical standards

will be reviewed for revision or renewal, as appropriate, on their fifth anniversary or sooner, if indicated.

Each practice parameter and technical standard, representing a policy statement by the College, has undergone a thorough consensus process in which it has

been subjected to extensive review and approval. The practice parameters and technical standards recognize that the safe and effective use of diagnostic

and therapeutic radiology requires specific training, skills, and techniques, as described in each document. Reproduction or modification of the published

practice parameter and technical standard by those entities not providing these services is not authorized.

Revised 2015 (Resolution 36)*

ACRSPR PRACTICE PARAMETER FOR THE PERFORMANCE OF

CONTRAST ESOPHAGRAMS AND UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL

EXAMINATIONS IN INFANTS AND CHILDREN

PREAMBLE

This document is an educational tool designed to assist practitioners in providing appropriate radiologic care for

patients. Practice Parameters and Technical Standards are not inflexible rules or requirements of practice and are

not intended, nor should they be used, to establish a legal standard of care1. For these reasons and those set forth

below, the American College of Radiology and our collaborating medical specialty societies caution against the

use of these documents in litigation in which the clinical decisions of a practitioner are called into question.

The ultimate judgment regarding the propriety of any specific procedure or course of action must be made by the

practitioner in light of all the circumstances presented. Thus, an approach that differs from the guidance in this

document, standing alone, does not necessarily imply that the approach was below the standard of care. To the

contrary, a conscientious practitioner may responsibly adopt a course of action different from that set forth in this

document when, in the reasonable judgment of the practitioner, such course of action is indicated by the condition

of the patient, limitations of available resources, or advances in knowledge or technology subsequent to

publication of this document. However, a practitioner who employs an approach substantially different from the

guidance in this document is advised to document in the patient record information sufficient to explain the

approach taken.

The practice of medicine involves not only the science, but also the art of dealing with the prevention, diagnosis,

alleviation, and treatment of disease. The variety and complexity of human conditions make it impossible to

always reach the most appropriate diagnosis or to predict with certainty a particular response to treatment.

Therefore, it should be recognized that adherence to the guidance in this document will not assure an accurate

diagnosis or a successful outcome. All that should be expected is that the practitioner will follow a reasonable

1 Iowa Medical Society and Iowa Society of Anesthesiologists v. Iowa Board of Nursing, ___ N.W.2d ___ (Iowa 2013) Iowa Supreme Court refuses to find

that the ACR Technical Standard for Management of the Use of Radiation in Fluoroscopic Procedures (Revised 2008) sets a national standard for who may

perform fluoroscopic procedures in light of the standards stated purpose that ACR standards are educational tools and not intended to establish a legal

standard of care. See also, Stanley v. McCarver, 63 P.3d 1076 (Ariz. App. 2003) where in a concurring opinion the Court stated that published standards or

guidelines of specialty medical organizations are useful in determining the duty owed or the standard of care applicable in a given situation even though

ACR standards themselves do not establish the standard of care.

PRACTICE PARAMETER Esophagrams Upper GI in Infants and Children / 1

course of action based on current knowledge, available resources, and the needs of the patient to deliver effective

and safe medical care. The sole purpose of this document is to assist practitioners in achieving this objective.

I. INTRODUCTION

This practice parameter was revised collaboratively by the American College of Radiology (ACR) and the Society

for Pediatric Radiology (SPR).

Examinations of the esophagus and the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract by single-contrast or double-contrast

technique are proven and useful procedures for evaluation of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. The goal of

radiologic examination is to establish the presence or absence, nature, and extent of disease with a diagnostic-

quality study using the minimum radiation dose necessary. The following standards are for performance of single-

contrast and double-contrast (biphasic) esophagrams and single-contrast and double-contrast (biphasic) upper GI

examinations in infants and children. Typically, single-contrast studies are used in infants and children, but

occasionally double-contrast studies are indicated.

II. INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

A. Indications for Esophagram

1. Pertinent history and symptoms serving as indications for an esophagram include, but are not limited to,

the following:

a. Dysphagia

b. Odynophagia

c. Noncardiac chest pain

d. Recurrent pneumonia or chronic tracheobronchial inflammation

2. The esophagram is helpful in the diagnosis and evaluation of many conditions, including, but not limited

to, the following:

a. Great-vessel anomalies

b. Tracheoesophageal fistula

c. Extrinsic compression

d. Postsurgical evaluation

e. Esophageal obstruction

f. Strictures

g. Suspected or known motility disorders

h. Esophagitis

i. Foreign bodies

j. Unexplained pneumomediastinum or suspected esophageal perforation

k. Neoplasm

l. Varices

B. Indications for Upper GI Examinations

1. Pertinent history and symptoms serving as indications for an upper GI examination include, but are not

limited to, the following:

a. Abdominal pain

b. Epigastric distress or discomfort

c. Weight loss or failure to thrive

d. Congenital syndromes or anomalies associated with intestinal malrotation

e. Chronic or recurrent respiratory disease, including cough

2 / Esophagrams Upper GI in Infants and Children PRACTICE PARAMETER

NOT FOR PUBLICATION, QUOTATION, OR CITATION

f. Acute life-threatening event. The term ALTE infers a respiratory arrest or near arrest that has a

differential diagnosis (apnea, child abuse, aspiration, etc).

g. Preoperative evaluation

h. Postoperative evaluation

i. Abdominal masses

k. Vomiting

l. Signs and/or symptoms of upper GI bleeding

2. The upper GI examination is helpful in diagnosing and evaluating many conditions including but not

limited to, the following:

a. Intestinal malrotation anomalies

b. Hiatal hernia

c. Suspected or known gastritis or duodenitis

d. Pyloric stenosis when ultrasound is not available

e. Gastric outlet or upper intestinal obstruction

f. Peptic ulcer disease

g. Duodenal laceration or intramural hematoma

h. Additional hernias (diaphragmatic, paraesophageal), including recurrent diaphragmatic hernia

i. Neoplasms

In reviewing indications for a contrast study of the stomach and duodenum, alternative imaging and nonimaging

methods of examining these structures should be considered as might be relevant to the individual case.

For the pregnant or potentially pregnant patient, see the ACRSPR Practice Parameter for Imaging Pregnant or

Potentially Pregnant Adolescents and Women with Ionizing Radiation [1].

III. QUALIFICATIONS OF PERSONNEL

For qualifications of physicians, medical physicists, radiologist assistants, and radiologic technologists, see the

ACRSPR Practice Parameter for General Radiography [2].

Additionally, physicians performing this procedure should have documented formal training in the performance

and interpretation of GI fluoroscopy as part of an accredited residency training program.

Qualifications of technologists performing GI radiography should be in accordance with the current ACR policy

statement on fluoroscopy2 and with operating procedures or manuals at the imaging facility. Fluoroscopy

technologists assisting in esophagrams or upper GI examinations should be thoroughly trained in GI radiography.

IV. SPECIFICATIONS OF THE EXAMINATION

The written or electronic request for a pediatric contrast esophagram or upper gastrointestinal examination should

provide sufficient information to demonstrate the medical necessity of the examination and allow for its proper

performance and interpretation.

2The American College of Radiology approves of the practice of certified and/or licensed radiologic technologists performing fluoroscopy in a facility or

department as a positioning or localizing procedure only, and then only if monitored by a supervising physician who is personally and immediately

available*. There must be a written policy or process for the positioning or localizing procedure that is approved by the medical director of the facility or

department/service and that includes written authority or policies and processes for designating radiologic technologists who may perform such procedures.

(ACR Resolution 26, 1987 revised in 2007, Resolution 12-m)

*For the purposes of this guideline, personally and immediately available is defined in manner of the personal supervision provision of CMSa

physician must be in attendance in the room during the performance of the procedure. Program Memorandum Carriers, DHHS, HCFA, Transmittal B-01-28,

April 19, 2001.

PRACTICE PARAMETER Esophagrams Upper GI in Infants and Children / 3

Documentation that satisfies medical necessity includes 1) signs and symptoms and/or 2) relevant history

(including known diagnoses). Additional information regarding the specific reason for the examination or a

provisional diagnosis would be helpful and may at times be needed to allow for the proper performance and

interpretation of the examination.

The request for the examination must be originated by a physician or other appropriately licensed health care

provider. The accompanying clinical information should be provided by a physician or other appropriately

licensed health care provider familiar with the patients clinical problem or question and consistent with the state

scope of practice requirements. (ACR Resolution 35, adopted in 2006)

A. Patient Selection

For a routine esophagram, the patient should not have ingested anything by mouth for a minimum of 2 hours. For

upper GI examination, oral feeding should be withheld for a time period appropriate for the patients age:

approximately 2 to 3 hours for neonates and young infants and 4 hours for older infants and children. Adolescents

should fast for at least 6 to 8 hours. Emergency examinations may be performed with shorter fasting times as

determined by the radiologist in concert with the referring physician.

B. Examination Preliminaries

An appropriate medical history should be available, including results of laboratory tests and imaging, endoscopic,

and surgical procedures as applicable.

Use of a child life specialist and/or parent may be helpful in enabling young patients to cooperate for the

examination. Immobilization devices may be helpful in patient positioning. These devices may help limit repeat

radiographic exposures and unnecessary radiation dose to patients, parents, technologists, and other personnel.

A preliminary radiographic or fluoroscopic scout image of the chest and/or abdomen may be useful, depending

on the specific clinical concern. Image-hold or image-grab images should NOT be used as scout images since

they are of much lower resolution, and subtle findings such as calcifications, small amounts of free air or

pneumatosis, or bony abnormalities, etc, may be missed. Routine scout imaging in the outpatient setting, unless

specifically requested by the ordering physician, can be replaced by a brief, initial fluoroscopic assessment. A

scout image should be obtained with inpatients if there has been no recent radiograph. Preliminary images should

be assessed for calcifications, skeletal abnormalities, anomalies of situs, bowel gas pattern, pneumoperitoneum,

evidence of prior surgery, catheters, and monitoring devices. A scout image of the chest should be assessed for

pneumomediastinum and pleural effusion, especially in cases where an esophagram is performed. A horizontal

beam image should be performed if the patient has an underlying condition that might predispose to

gastrointestinal (GI) tract perforation. In the absence of preceding abdominal imaging, scout images are especially

helpful in the workup of neonatal bowel obstruction, since they may influence the choice of initial fluoroscopic

study and GI contrast (eg, upper GI for proximal bowel obstruction and contrast enema for distal small bowel or

colonic obstruction).

C. Examination Technique

The examination procedure should be tailored by the radiologist to the individual patient as warranted by clinical

circumstances and the condition of the patient, to produce a diagnostic-quality examination. Preliminary findings

during the examination may indicate a need to alter technique in subsequent portions of the examination.

The contrast medium should be delivered in a manner that is appropriate for the patients age. Flavoring agents

may be added in older patients. Neonates and infants may be fed contrast from a baby bottle with a nipple.

Alternatively, a device consisting of a feeding tube or orogastric tube passed through a nipple is sometimes used

to deliver the contrast into the mouth [3]; this should be done under careful fluoroscopic control to prevent

4 / Esophagrams Upper GI in Infants and Children PRACTICE PARAMETER

NOT FOR PUBLICATION, QUOTATION, OR CITATION

aspiration. Older infants able to bottle-feed themselves may be allowed to do so. The contrast may be given by

straw or taken directly from a cup by an older child. A nasogastric tube, gastrostomy tube, or jejunostomy tube

may be used as appropriate. In neonates or young infants with a history of bilious emesis, a nasogastric tube can

be placed with tip in the distal stomach to empty the stomach so that a controlled upper GI with a small amount of

contrast and air can effectively evaluate for malrotation and/or volvulus, using the least amount of contrast and

fluoroscopic time.

The amount and type of contrast material given are determined by the childs age and the indications for the

study. Barium is the preferred contrast medium for most studies [4]. Nonionic iodinated contrast media may be

given to assess the integrity of an esophageal anastomosis, diagnose duodenal obstruction or perforation, or

diagnose intestinal malrotation in selected critically ill patients. Iso-osmolar or near iso-osmolar solutions are

important in cases in which there is risk of aspiration [5]. Iso-osmolar contrast media are particularly important in

critically ill premature neonates and infants to avoid serum electrolyte shifts. Diatrizoic acid, a very highly

osmotically active water-soluble contrast agent, should not be administered orally in neonates and young infants

because this patient population has a higher risk of gastroesophageal reflux and aspiration, and aspirated

hyperosmolar contrast may result in pulmonary edema and a severe chemical pneumonitis.

Sufficient still images and/or fluoroscopic image clips should be recorded to adequately evaluate normal anatomy

and characterize any abnormalities present. In general, this includes at least anteroposterior and lateral projections

of all anatomy, and often oblique images, for adequate assessment. The use of fluoroscopic image store/last

image-hold can markedly reduce patient dose compared to spot images. Fluoroscopic stored images do not have

the same resolution as spot images but may be adequate for documentation depending upon the study

circumstances.

1. Single-contrast esophagram

a. The anatomic structure and motility of the entire esophagus should be evaluated fluoroscopically.

Appropriate images should be obtained to document normal and abnormal findings. The examination

is optimally performed in the lateral and anteroposterior projections, with visualization of the

nasopharynx to the gastric fundus [6].

b. Esophagrams performed in infants with suspected tracheoesophageal fistula are optimally performed

in a controlled manner, with full distension of the esophagus, which can be achieved with normal

drinking in patients who drink contrast readily. In patients who do not drink sufficient contrast to

distend the esophagus, the contrast can be administered in small amounts initially through a small

feeding tube placed in the upper esophagus near the thoracic inlet, with the infant in a right anterior

oblique or lateral position. This requires careful fluoroscopic monitoring of the contrast as it exits the

tube to prevent aspiration. If no fistula is identified on the early images, the study may be completed

with standard oral administration of contrast. Fluoroscopic observation from hypopharynx to carina in

the lateral view throughout contrast instillation usually will allow differentiation of contrast in the

trachea due to aspiration versus a fistula.

c. Imaging of the esophagus should include an assessment of swallowing in the lateral view, especially

if the patient has symptoms suggesting swallowing dysfunction such as coughing and choking and/or

gagging during feeding. This should include imaging from the base of the tongue through the upper

esophageal sphincter. Modified barium swallow is a more detailed evaluation of the oral, pharyngeal,

and upper esophageal phases of swallowing with variable consistency materials, usually performed in

conjunction with a speech pathologist or occupational therapist. Please refer to the ACR Practice

Parameter for the Performance of the Modified Barium Swallow [7] for additional information.

PRACTICE PARAMETER Esophagrams Upper GI in Infants and Children / 5

2. Double-contrast (biphasic) esophagram

Double-contrast esophagrams are seldom performed in pediatric patients, but they may help to evaluate

mucosal integrity in adolescents. (See the ACR Practice Parameter for the Performance of Esophagrams

and Upper Gastrointestinal Examinations in Adults [8], section IV.C.)

3. Single-contrast upper GI examination

a. Fluoroscopic assessment of swallowing and the anatomic structure and motility of the entire

esophagus, stomach, and duodenum should be performed, and appropriate images should be obtained

to document normal and abnormal findings. Suggested images include frontal and lateral views of the

barium-distended esophagus, stomach, and duodenum and images of the partially filled esophagus.

Initial passage of contrast through the duodenum should be observed directly with fluoroscopy to

confirm the position of the duodenojejunal junction (DJJ) [9]. This can be documented with serial

multiple fluorocapture images or fluoroscopy video capture, where available [10]. On the first upper

GI examination in an infant or child, the position of the DJJ should be documented on both frontal

and lateral positions to diagnose or exclude malrotation [9,11]. The lateral view is important to assure

the retroperitoneal position of the normally rotated duodenum and the normal height of the DJJ at the

level of the duodenal bulb; additionally, the frontal view assures the normal position of the DJJ, at or

to the left of the left pedicle of the vertebral bodies, and at a height approximately at the level of the

duodenal bulb [12-14].

b. Images of gastroesophageal reflux should be recorded by last image-hold if reflux occurs during the

examination. However, since reflux is a physiologic phenomenon and more sensitive tests exist,

neither provocation of reflux nor prolonged fluoroscopy monitoring for detection is recommended

[15].

c. A final image documenting gastric emptying and the progress of contrast through small-bowel loops

may be obtained at the conclusion of the examination.

4. Double-contrast (biphasic) upper GI examination

Double contrast upper GI examinations are seldom performed in pediatric patients, but they may help to

evaluate mucosal integrity in adolescents. (See the ACR Practice Parameter for the Performance of

Esophagrams and Upper Gastrointestinal Examinations in Adults [8], section IV.C.)

5. Quality control indicators

The following quality control indicators should be applied to all esophagram and upper GI examinations:

a. When examinations are completed, patients should be held in the fluoroscopic area until the physician

has reviewed the images.

b. An attempt should be made to resolve questionable radiologic findings before the patient leaves.

Repeat fluoroscopy should be performed as necessary.

c. Correlation of radiologic, endoscopic, surgical, and pathologic findings is valuable for quality

improvement, whenever feasible.

V. DOCUMENTATION

An official interpretation (final report) of the examination should be included in the patients medical record.

Reporting should be in accordance with the ACR Practice Parameter for Communication of Diagnostic Imaging

Findings [16].

6 / Esophagrams Upper GI in Infants and Children PRACTICE PARAMETER

NOT FOR PUBLICATION, QUOTATION, OR CITATION

VI. EQUIPMENT SPECIFICATIONS

Examinations must be performed with fluoroscopic and radiographic equipment meeting all applicable federal,

state, and local radiation standards. Fluoroscopy units with settings for pediatric technique are recommended. If

possible, a pulsed fluoroscopic technique and equipment should be used to reduce the radiation exposure. The

equipment should provide diagnostic fluoroscopic image quality and recording capability (radiographs, video, or

digital). The equipment should be capable of producing kilovoltage greater than 100 kVp. Equipment necessary to

compress and isolate accessible regions of the small bowel should be readily available. Digital equipment with

fluorohold and/or fluorocapture capability is desirable.

Facilities should have the ability to deliver supplemental oxygen to suction the oral cavity and the upper

respiratory tract, and to respond to life-threatening emergencies that may accompany aspiration, allergic reaction

to contrast agents, or reflux.

VII. RADIATION SAFETY IN IMAGING

Radiologists, medical physicists, registered radiologist assistants, radiologic technologists, and all supervising

physicians have a responsibility for safety in the workplace by keeping radiation exposure to staff, and to society

as a whole, as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA) and to assure that radiation doses to individual patients

are appropriate, taking into account the possible risk from radiation exposure and the diagnostic image quality

necessary to achieve the clinical objective. All personnel that work with ionizing radiation must understand the

key principles of occupational and public radiation protection (justification, optimization of protection and

application of dose limits) and the principles of proper management of radiation dose to patients (justification,

optimization and the use of dose reference levels) http://www-

pub.iaea.org/MTCD/Publications/PDF/Pub1578_web-57265295.pdf.

Nationally developed guidelines, such as the ACRs Appropriateness Criteria, should be used to help choose the

most appropriate imaging procedures to prevent unwarranted radiation exposure.

Facilities should have and adhere to policies and procedures that require varying ionizing radiation examination

protocols (plain radiography, fluoroscopy, interventional radiology, CT) to take into account patient body habitus

(such as patient dimensions, weight, or body mass index) to optimize the relationship between minimal radiation

dose and adequate image quality. Automated dose reduction technologies available on imaging equipment should

be used whenever appropriate. If such technology is not available, appropriate manual techniques should be used.

Additional information regarding patient radiation safety in imaging is available at the Image Gently for

children (www.imagegently.org) and Image Wisely for adults (www.imagewisely.org) websites. These

advocacy and awareness campaigns provide free educational materials for all stakeholders involved in imaging

(patients, technologists, referring providers, medical physicists, and radiologists).

Radiation exposures or other dose indices should be measured and patient radiation dose estimated for

representative examinations and types of patients by a Qualified Medical Physicist in accordance with the

applicable ACR Technical Standards. Regular auditing of patient dose indices should be performed by comparing

the facilitys dose information with national benchmarks, such as the ACR Dose Index Registry, the NCRP

Report No. 172, Reference Levels and Achievable Doses in Medical and Dental Imaging: Recommendations for

the United States or the Conference of Radiation Control Program Directors National Evaluation of X-ray

Trends. (ACR Resolution 17 adopted in 2006 revised in 2009, 2013, Resolution 52).

PRACTICE PARAMETER Esophagrams Upper GI in Infants and Children / 7

VIII. QUALITY CONTROL AND IMPROVEMENT, SAFETY, INFECTION CONTROL, AND

PATIENT EDUCATION

Policies and procedures related to quality, patient education, infection control, and safety should be developed and

implemented in accordance with the ACR Policy on Quality Control and Improvement, Safety, Infection Control,

and Patient Education appearing under the heading Position Statement on QC & Improvement, Safety, Infection

Control, and Patient Education on the ACR website (http://www.acr.org/guidelines).

The lowest possible radiation dose consistent with acceptable diagnostic image quality should be used. Radiation

doses should be determined periodically based on a reasonable sample of pediatric examinations. Technical

factors should be appropriate for the size and the age of the child and should be determined with consideration of

parameters such as characteristics of the imaging system, organs in the radiation field, lead shielding, etc.

Guidelines concerning effective pediatric technical factors are published in the radiologic literature and at

websites such as www.imagegently.org.

Equipment performance monitoring should be in accordance with the ACR Technical Standard for Diagnostic

Medical Physics Performance Monitoring of Radiographic and Fluoroscopic Equipment [17].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This practice parameter was revised according to the process described under the heading The Process for

Developing ACR Practice Parameters and Technical Standards on the ACR website

(http://www.acr.org/guidelines) by the Committee on Practice Parameters Pediatric Radiology of the

Commission on Pediatric Radiology, in collaboration with the SPR.

Collaborative Committee

Members represent their societies in the initial and final revision of this practice parameter.

ACR SPR

Brian D. Coley, MD, FACR, Chair Karen Blumberg, MD, FACR

David A. Bloom, MD, FACR Steven Jay Kraus MD, MS

Lynn A. Fordham, MD, FACR Martha M. Munden, MD

Committee on Practice Parameters Pediatric Radiology

(ACR Committee responsible for sponsoring the draft through the process)

Eric N. Faerber, MD, FACR, Chair

Richard M. Benator, MD, FACR

Lorna P. Browne, MB, BCh

Timothy J. Carmody, MD

Brian D. Coley, MD, FACR

Lee K. Collins, MD

Monica S. Epelman, MD

Lynn A. Fordham, MD, FACR

Kerri A. Highmore, MD

Tal Laor, MD

Marguerite T. Parisi, MD, MS

Sumit Pruthi, MBBS

Nancy K. Rollins, MD

Pallavi Sagar, MD

Manrita K. Sidhu, MD

8 / Esophagrams Upper GI in Infants and Children PRACTICE PARAMETER

NOT FOR PUBLICATION, QUOTATION, OR CITATION

Marta Hernanz-Schulman, MD, FACR, Chair, Commission on Pediatric Radiology

Debra L. Monticciolo, MD, FACR, Chair, Commission on Quality and Safety

Jacqueline Anne Bello, MD, FACR, Vice-Chair, Commission on Quality and Safety

Julie K. Timins, MD, FACR, Chair, Committee on Practice Parameters and Technical Standards

Matthew S. Pollack, MD, FACR, Vice Chair, Committee on Practice Parameters and Technical Standards

Comments Reconciliation Committee

Eric J. Stern, MD, Chair

Richard B. Gunderman, MD, PhD, FACR, Co-Chair

Kimberly E. Applegate, MD, MS, FACR

David A. Bloom, MD, FACR

Karen Blumberg, MD, FACR

Christopher I. Cassady, MD

Brian D. Coley, MD, FACR

Eric N. Faerber, MD, FACR

Lynn A. Fordham, MD, FACR

Marta Hernanz-Schulman, MD, FACR

William T. Herrington, MD, FACR

Steven J. Kraus, MD, MS

Paul A. Larson, MD, FACR

Debra L. Monticciolo, MD, FACR

Martha M. Munden, MD

Matthew S. Pollack, MD, FACR

Julie K. Timins, MD, FACR

REFERENCES

1. American College of Radiology. ACRSPR Practice Parameter for Imaging Pregnant or Potentially Pregnant

Adolescents and Women with Ionizing Radiation. 2014;

http://www.acr.org/~/media/9E2ED55531FC4B4FA53EF3B6D3B25DF8.pdf. Accessed October 13, 2014.

2. American College of Radiology. ACRSPR Practice Parameter for General Radiography. 2014;

http://www.acr.org/~/media/95AB63131AD64CC6BB54BFE008DBA30C.pdf. Accessed October 13, 2014.

3. Poznanski A. A simple device for administering barium to infants. Radiology. 1969;93(5):1106.

4. Cohen MD, Towbin R, Baker S, et al. Comparison of iohexol with barium in gastrointestinal studies of

infants and children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156(2):345-350.

5. Cohen MD. Choosing contrast media for the evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract of neonates and infants.

Radiology. 1987;162(2):447-456.

6. Fordham LA. Imaging of the esophagus in children. Radiol Clin North Am. 2005;43(2):283-302.

7. American College of Radiology. ACR Practice Parameter for the Performance of the Modified Barium

Swallow. 2014; http://www.acr.org/~/media/7D306289D61341DD9146466186A77DBE.pdf. Accessed

October 13, 2014.

8. American College of Radiology. ACR Practice Parameter for the Performance of Esophagrams and Upper

Gastrointestinal Examinations in Adults. 2014;

http://www.acr.org/~/media/5223A3FBC92E40378DF6E55FB8E6134B.pdf. Accessed October 13, 2014.

9. Applegate KE, Anderson JM, Klatte EC. Intestinal malrotation in children: a problem-solving approach to the

upper gastrointestinal series. Radiographics. 2006;26(5):1485-1500.

10. Hernandez RJ, Goodsitt MM. Reduction of radiation dose in pediatric patients using pulsed fluoroscopy. AJR

Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167(5):1247-1253.

11. Koplewitz BZ, Daneman A. The lateral view: a useful adjunct in the diagnosis of malrotation. Pediatr Radiol.

1999;29(2):144-145.

PRACTICE PARAMETER Esophagrams Upper GI in Infants and Children / 9

12. Berdon WE. The diagnosis of malrotation and volvulus in the older child and adult: a trap for radiologists.

Pediatr Radiol. 1995;25(2):101-103.

13. Jamieson D, Stringer D. Small Bowel. In: Babyn PS, Stringer DA, ed. Pediatric Gastrointestinal Imaging and

Intervention. 2nd ed. Hamilton, Ontario: Decker; 2000:311-332.

14. Katz ME, Siegel MJ, Shackelford GD, McAlister WH. The position and mobility of the duodenum in

children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148(5):947-951.

15. Simanovsky N, Buonomo C, Nurko S. The infant with chronic vomiting: the value of the upper GI series.

Pediatr Radiol. 2002;32(8):549-550; discussion 551.

16. American College of Radiology. ACR Practice Parameter for Communication of Diagnostic Imaging

Findings. 2014; http://www.acr.org/~/media/C5D1443C9EA4424AA12477D1AD1D927D.pdf. Accessed

October 13, 2014.

17. American College of Radiology. ACR Technical Standard for Diagnostic Medical Physics Performance

Monitoring of Radiographic and Fluoroscopic Equipment. 2014;

http://www.acr.org/~/media/B393698E23C44F74BB37FE3629B14200.pdf. Accessed October 13, 2014.

*Parameters and technical standards are published annually with an effective date of October 1 in the year in

which amended, revised, or approved by the ACR Council. For practice parameters and technical standards

published before 1999, the effective date was January 1 following the year in which the practice parameter or

technical standard was amended, revised, or approved by the ACR Council.

Development Chronology for this Practice Parameter

1997 (Resolution 25)

Revised 2001 (Resolution 29)

Revised 2006 (Resolution 43, 17, 34, 35)

Amended 2007 (Resolution 12m)

Revised 2010 (Resolution 42)

Amended 2014 (Resolution 39)

Revised 2015 (Resolution 36)

10 / Esophagrams Upper GI in Infants and Children PRACTICE PARAMETER

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Dysphagia: Diagnosis and Treatment of Esophageal Motility DisordersDari EverandDysphagia: Diagnosis and Treatment of Esophageal Motility DisordersMarco G. PattiBelum ada peringkat

- Esophagrams Upper GIDokumen11 halamanEsophagrams Upper GIMark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- Acr Practice Parameter For The Performance of Fluoroscopic Contrast Enema Examination in AdultsDokumen8 halamanAcr Practice Parameter For The Performance of Fluoroscopic Contrast Enema Examination in AdultsHercules RianiBelum ada peringkat

- Acr-Spr Practice Parameter For The Performance of Fluoroscopic and Sonographic Voiding Cystourethrography in ChildrenDokumen11 halamanAcr-Spr Practice Parameter For The Performance of Fluoroscopic and Sonographic Voiding Cystourethrography in ChildrenCentanarianBelum ada peringkat

- Acr Practice Parameter For The Performance of HysterosalpingographyDokumen9 halamanAcr Practice Parameter For The Performance of HysterosalpingographyAsif JielaniBelum ada peringkat

- ACR Recomendations On Exposure TimeDokumen9 halamanACR Recomendations On Exposure TimeMuhammad AreebBelum ada peringkat

- GI Scintigraphy 1382731852503 4 PDFDokumen10 halamanGI Scintigraphy 1382731852503 4 PDFMark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- US PelvisDokumen11 halamanUS PelvisDian Putri NingsihBelum ada peringkat

- Tugas GerdDokumen6 halamanTugas GerdMarc Chagall René MagritteBelum ada peringkat

- Acute Pancreatitis-AGA Institute Medical Position Statement.Dokumen7 halamanAcute Pancreatitis-AGA Institute Medical Position Statement.Nicole BiduaBelum ada peringkat

- Acr Practice Parameter For Breast UltrasoundDokumen7 halamanAcr Practice Parameter For Breast UltrasoundBereanBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical Diognosis ColorectalDokumen2 halamanClinical Diognosis ColorectalRizal Sven VollfiedBelum ada peringkat

- Acr-Spr Practice Parameter For The Performance and Interpretation of Skeletal Surveys in ChildrenDokumen9 halamanAcr-Spr Practice Parameter For The Performance and Interpretation of Skeletal Surveys in ChildrenPediatría grupoBelum ada peringkat

- Management of Acute Pancreatitis: Clinical GuidelinesDokumen19 halamanManagement of Acute Pancreatitis: Clinical GuidelinesInna MariaBelum ada peringkat

- Pi Is 0016508520300184Dokumen12 halamanPi Is 0016508520300184ntnquynhproBelum ada peringkat

- Us ObDokumen16 halamanUs ObWahyu RianiBelum ada peringkat

- DyspepsiaDokumen26 halamanDyspepsiaYaasin R NBelum ada peringkat

- Myelography PDFDokumen13 halamanMyelography PDFAhmad HaririBelum ada peringkat

- Chatoor Organising A Clinical Service For Patients With Pelvic Floor DisordersDokumen10 halamanChatoor Organising A Clinical Service For Patients With Pelvic Floor DisordersDavion StewartBelum ada peringkat

- Related LiteratureDokumen4 halamanRelated LiteratureJude FabellareBelum ada peringkat

- ERCP Indications ContraindicationsDokumen6 halamanERCP Indications ContraindicationsTran DuongBelum ada peringkat

- Dutch guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of rectal prolapseDokumen8 halamanDutch guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of rectal prolapsechairulBelum ada peringkat

- Overactive BladderDokumen50 halamanOveractive BladderYaneth AngelBelum ada peringkat

- STCDokumen73 halamanSTCFreddy RojasBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal GerdDokumen12 halamanJurnal Gerdaminullahh22Belum ada peringkat

- Quality Indicators For Esophagogastroduodenoscopy: ASGE/ACG Taskforce On Quality in EndosDokumen6 halamanQuality Indicators For Esophagogastroduodenoscopy: ASGE/ACG Taskforce On Quality in EndosMario A Herrera CortésBelum ada peringkat

- EBM of DyspepsiaDokumen228 halamanEBM of DyspepsiaxcalibursysBelum ada peringkat

- MR AbdDokumen14 halamanMR AbdKhairunNisaBelum ada peringkat

- DCR 2016 Constipation, Evaluation and Management ofDokumen14 halamanDCR 2016 Constipation, Evaluation and Management ofrisewfBelum ada peringkat

- Percutaneous NephrosDokumen17 halamanPercutaneous NephrosIan HuangBelum ada peringkat

- Practiceguidelines: Received: 4 May 2017 Accepted: 22 May 2017 DOI: 10.1002/hed.24866Dokumen7 halamanPracticeguidelines: Received: 4 May 2017 Accepted: 22 May 2017 DOI: 10.1002/hed.24866MdacBelum ada peringkat

- Bowel Prep Before ColonosDokumen14 halamanBowel Prep Before ColonosDan BobeicaBelum ada peringkat

- 10.1053@j.gastro DiverticulitisDokumen20 halaman10.1053@j.gastro DiverticulitisCarlos CaicedoBelum ada peringkat

- Diagnostic TestsDokumen11 halamanDiagnostic TestsMae GabrielBelum ada peringkat

- Disfagia PDFDokumen11 halamanDisfagia PDFRonald MoraBelum ada peringkat

- Dyspepsia: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines NetworkDokumen30 halamanDyspepsia: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines NetworkAna Cristina IssaBelum ada peringkat

- Dyspepsia Management Guidelines: PrefaceDokumen9 halamanDyspepsia Management Guidelines: PrefacecorsaruBelum ada peringkat

- Guidelines For Laparoscopic Peritoneal Dialysis Access SurgeryDokumen28 halamanGuidelines For Laparoscopic Peritoneal Dialysis Access SurgeryIgnatia Rosalia KiranaBelum ada peringkat

- Acr - SPR - Sru Practice Parameter For The Performing andDokumen6 halamanAcr - SPR - Sru Practice Parameter For The Performing andModou NianeBelum ada peringkat

- Neurosonog ACR Neonates 2019Dokumen8 halamanNeurosonog ACR Neonates 2019Modou NianeBelum ada peringkat

- Complications of Upper GI SDokumen30 halamanComplications of Upper GI SNavin ChandarBelum ada peringkat

- ERCP Procedure Guide SummaryDokumen7 halamanERCP Procedure Guide SummaryFachrur RodjiBelum ada peringkat

- RespDokumen2 halamanRespNicolaeDincaBelum ada peringkat

- Masonetal - alimentPharmacolTher20052191135 43Dokumen9 halamanMasonetal - alimentPharmacolTher20052191135 43Riefka Ananda ZulfaBelum ada peringkat

- BSG Guidelines For The Management of Oesophageal and Gastric CancerDokumen24 halamanBSG Guidelines For The Management of Oesophageal and Gastric CancergeorgeBelum ada peringkat

- DyspepsiaDokumen228 halamanDyspepsiaamal.fathullah100% (1)

- Gnur 405 SuzyDokumen6 halamanGnur 405 SuzySeth MensahBelum ada peringkat

- GA by Ultrasound SOGCDokumen11 halamanGA by Ultrasound SOGCBrendaBelum ada peringkat

- Guidelines For The Clinical Application of Laparoscopic Biliary Tract SurgeryDokumen37 halamanGuidelines For The Clinical Application of Laparoscopic Biliary Tract SurgeryTerence SalazarBelum ada peringkat

- Complications of ColonosDokumen19 halamanComplications of ColonosFanny PritaningrumBelum ada peringkat

- Acr-Spr-Ssr Practice Parameter For The Performance of Radiography of The ExtremitiesDokumen8 halamanAcr-Spr-Ssr Practice Parameter For The Performance of Radiography of The ExtremitiesEdiPtkBelum ada peringkat

- Acr-Spr-Ssr Practice Parameter For The Performance of Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry (Dxa)Dokumen15 halamanAcr-Spr-Ssr Practice Parameter For The Performance of Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry (Dxa)Pablo PinedaBelum ada peringkat

- SAGES guidelines for laparoscopy during pregnancyDokumen16 halamanSAGES guidelines for laparoscopy during pregnancymaryzka rahmadianitaBelum ada peringkat

- CPG Ulcer enDokumen24 halamanCPG Ulcer enAlina BotnarencoBelum ada peringkat

- ScoliosisDokumen10 halamanScoliosisSilma FarrahaBelum ada peringkat

- Guia Laparoscopía Diagnóstica SAGESDokumen45 halamanGuia Laparoscopía Diagnóstica SAGESMonik B. CspdsBelum ada peringkat

- Guidelines For Diagnostic Laparoscopy: PreambleDokumen8 halamanGuidelines For Diagnostic Laparoscopy: PreambleMilka DatuBelum ada peringkat

- Acr-Spr-Ssr Practice Parameter For The Performance of Musculoskeletal Quantitative Computed Tomography (QCT)Dokumen14 halamanAcr-Spr-Ssr Practice Parameter For The Performance of Musculoskeletal Quantitative Computed Tomography (QCT)Rahmanu ReztaputraBelum ada peringkat

- MRCP AcrDokumen8 halamanMRCP AcrgurudrarunBelum ada peringkat

- Volume 15, Number 3 March 2011Dokumen152 halamanVolume 15, Number 3 March 2011Nicolai BabaliciBelum ada peringkat

- Radiation Therapy: Khan BentelDokumen9 halamanRadiation Therapy: Khan BentelMark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- Radiation Physics LectureDokumen272 halamanRadiation Physics LectureMark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- Radiographic Pathology ReviewerDokumen479 halamanRadiographic Pathology ReviewerMark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- SkullDokumen19 halamanSkullMark M. Alipio100% (1)

- Air Embolism Diagnosed by Doppler Ultrasound .25Dokumen4 halamanAir Embolism Diagnosed by Doppler Ultrasound .25Mark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- ReferencesDokumen2 halamanReferencesMark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- Philosophy Statement " Aestimamus Vitam "Dokumen4 halamanPhilosophy Statement " Aestimamus Vitam "Mark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- Anaphysio ProfpquizDokumen9 halamanAnaphysio ProfpquizMark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- Radiation Therapy: Khan BentelDokumen9 halamanRadiation Therapy: Khan BentelMark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- Radiation Biology and PhysicsDokumen4 halamanRadiation Biology and PhysicsMark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- Research TopicsDokumen1 halamanResearch TopicsMark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- Goals: Principles of Imaging Science IDokumen13 halamanGoals: Principles of Imaging Science INeeraj JangidBelum ada peringkat

- Food DeliveryDokumen3 halamanFood DeliveryMark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- Nmat Answer Key-PhysicsDokumen5 halamanNmat Answer Key-PhysicsNina Charlyn AlbaBelum ada peringkat

- Review RadiotechDokumen587 halamanReview RadiotechMark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- 01 - Basic Physics 2011 PDFDokumen13 halaman01 - Basic Physics 2011 PDFMark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- Blaivas 2004Dokumen5 halamanBlaivas 2004Mark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- Radiographic TestingDokumen47 halamanRadiographic TestingsmrndrdasBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing Chapter 48 Skin Integrity and Wound Care FlashcardsDokumen6 halamanNursing Chapter 48 Skin Integrity and Wound Care FlashcardsMark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- Acing The Orthopedic Board ExamDokumen481 halamanAcing The Orthopedic Board ExamMark M. Alipio100% (9)

- Sustainability 09 01823Dokumen16 halamanSustainability 09 01823Mark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- Supp Hip OnlyDokumen20 halamanSupp Hip OnlyMark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- Final ThesisDokumen147 halamanFinal ThesisMark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- NCLEX Test ReviewDokumen7 halamanNCLEX Test ReviewPhuong Tran100% (1)

- 2014528175541Dokumen20 halaman2014528175541Mark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- Practice Quiz Answers Unit 1Dokumen5 halamanPractice Quiz Answers Unit 1Marvin BautistaBelum ada peringkat

- Survey Radiobiology 2012Dokumen11 halamanSurvey Radiobiology 2012Mark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- 203 AbDokumen39 halaman203 AbMark M. AlipioBelum ada peringkat

- Amundson Basic Biology PDFDokumen13 halamanAmundson Basic Biology PDFFernanda RibeiroBelum ada peringkat

- MEDICAL PREFIXES AND SUFFIXESDokumen3 halamanMEDICAL PREFIXES AND SUFFIXESRoberto Giorgio N. PachecoBelum ada peringkat

- Case DiscussionDokumen8 halamanCase DiscussionAishwarya BharathBelum ada peringkat

- Horticulture Therapy For Physically and Mentally Challenged ChildrenDokumen41 halamanHorticulture Therapy For Physically and Mentally Challenged ChildrenbelamanojBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing Care Plan - Acute Pain Assessment Diagnosis Scientific Rationale Planning Intervention Rationale EvaluationDokumen3 halamanNursing Care Plan - Acute Pain Assessment Diagnosis Scientific Rationale Planning Intervention Rationale EvaluationNicole cuencosBelum ada peringkat

- Skin, Soft Tissue & BreastDokumen10 halamanSkin, Soft Tissue & BreastFarhin100% (1)

- The Drug Interaction Probability ScaleDokumen2 halamanThe Drug Interaction Probability ScaleAta07Belum ada peringkat

- Psychoanalytic EssayDokumen7 halamanPsychoanalytic Essayapi-462360394Belum ada peringkat

- Proptosis UnilateralDokumen5 halamanProptosis UnilateralCarlos NiveloBelum ada peringkat

- Schema Focused TherapyDokumen34 halamanSchema Focused TherapyKen Murray100% (6)

- Caries Predication, Risk Assessment and Treatment PlanningDokumen74 halamanCaries Predication, Risk Assessment and Treatment PlanningmohammadBelum ada peringkat

- Mobility: How To Fix The 3 Most Common Mobility IssuesDokumen32 halamanMobility: How To Fix The 3 Most Common Mobility Issuespablo ito100% (4)

- NCP - Acute Pain Stomach CancerDokumen2 halamanNCP - Acute Pain Stomach CancerJohn Michael TaylanBelum ada peringkat

- ProposalDokumen45 halamanProposalJP firmBelum ada peringkat

- Every Business Is A Living Being! Pranic Healing Applied To BusinessesDokumen2 halamanEvery Business Is A Living Being! Pranic Healing Applied To BusinessesHitesh Parmar100% (8)

- 2018 DPRI Booklet As of February 2019Dokumen34 halaman2018 DPRI Booklet As of February 2019kkabness101 YULBelum ada peringkat

- Capnography - Self Study - GuideDokumen22 halamanCapnography - Self Study - GuideSuresh KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Healthy Narcissism and NPD, SperryDokumen8 halamanHealthy Narcissism and NPD, SperryjuaromerBelum ada peringkat

- Psych Turner SyndromeDokumen13 halamanPsych Turner SyndromeJerson CadigalBelum ada peringkat

- Traumatic Brain Injury and Cerebral ResuscitationDokumen56 halamanTraumatic Brain Injury and Cerebral ResuscitationsyahirBelum ada peringkat

- National Institute of Disaster ManagementDokumen32 halamanNational Institute of Disaster ManagementJainBelum ada peringkat

- III D2 - Hypothyroidism-Hyperthyroidism Diagnostic Test, Therapeutic & Educative InterventionsDokumen23 halamanIII D2 - Hypothyroidism-Hyperthyroidism Diagnostic Test, Therapeutic & Educative InterventionsJireh Yang-ed ArtiendaBelum ada peringkat

- Cognitive Rehabilitation Programs in Schizophrenia PDFDokumen26 halamanCognitive Rehabilitation Programs in Schizophrenia PDFMeindayaniBelum ada peringkat

- High Risk NewbornDokumen76 halamanHigh Risk NewbornVijith.V.kumar91% (22)

- CBT of DepressionDokumen15 halamanCBT of DepressionRidwan MuttaqinBelum ada peringkat

- The Gerson Therapy For Those Dying of CancerDokumen80 halamanThe Gerson Therapy For Those Dying of CancerElton Luz100% (1)

- DECS Form 178ORIGINALDokumen1 halamanDECS Form 178ORIGINALJhon FurioBelum ada peringkat

- Catalogue: ProductDokumen24 halamanCatalogue: ProductRavi KrishnanBelum ada peringkat

- Anal FissuresDokumen2 halamanAnal FissureskhadzxBelum ada peringkat

- Cerebrovascular DiseasesDokumen16 halamanCerebrovascular DiseasesSopna ZenithBelum ada peringkat

- Medsurg Cardio Ana&PhysioDokumen6 halamanMedsurg Cardio Ana&Physiorabsibala80% (10)

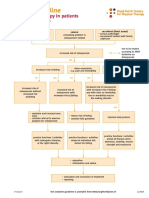

- Dutch Osteoporosis Physiotherapy FlowchartDokumen1 halamanDutch Osteoporosis Physiotherapy FlowchartyohanBelum ada peringkat