Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

Diunggah oleh

Mónica HurtadoHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

Diunggah oleh

Mónica HurtadoHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American

History

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

Robert M. Buffington

Subject: History of Mexico, 18891910, Cultural History, Social History, Gender and Sexuality

Online Publication Date: Apr 2016 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.19

Summary and Keywords

The Porfirian era (18761911) marked a watershed in social understandings of manhood.

New ideas about what it meant to be a man had appeared in Mexico by the middle of the

19th century in the form of self-help manuals intended primarily for middle-class and

bourgeois men who sought to distinguish themselves in a post-independence society that

had done away with legal distinctions, including aristocratic titles. Marks of distinction

included cleanliness, good grooming, moderation, affability, respectability, love of

country, and careful attentiveness to the needs and opinions of others, including women,

children, and social inferiorsan approach that artfully combined longstanding notions

of masculine responsibility and authority with modern ideas about self-mastery and

citizenship, especially the sublimation of volatile passions in all domains of social life.

Modern qualities also mapped onto traditional concerns about male honor predicated on

the fulfillment of patriarchal duties, especially the control of female dependents. The

socially validated, hegemonic masculinity produced by this amalgamation of modern

and traditional ideas proved burdensome for many middle-class men, who struggled to

maintain an always precarious sense of honor or who rejected the constraints it sought to

impose on their behavior. For men from less privileged classes, it represented an

impossible ideal that they sometimes rejected through the adoption of antisocial protest

masculinities and often satirized as delusional or unmanly, even as they too came to

define their masculinity in relation to a modern/traditional binary. The modern/traditional

binary that characterized ideas about masculinity for all sectors of Porfirian society has

persisted until the present day, despite the epochal 1910 social revolution that

inaugurated a new era in Mexican social relations.

Keywords: masculinity (in Mexico), machismo, Porfirian modernity, gender relations (in Mexico), homosexuality

(in Mexico), homophobia (in Mexico), Manual of Urbanity and Good Manners, Porfiriato

The protracted period of relative political stability in Mexico known to historians as the

Porfiriato (18761911) in recognition of the commanding presence of its major political

Page 1 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

figure, Porfirio Daz, had a profound impact on social relations, including how society

viewed manhood and how men understood and experienced themselves as men. Ideas

about modernity, especially what it meant to be modern, played a central role in

developing and fostering these new notions of masculinity. Although by most measures

everyday male behaviors probably changed very little and very slowly during this period,

the way that Mexicans from all walks of life made sense of those behaviors underwent

what was for many of them a radical transformation. Some men (and women) embraced

modern manhood, while others preferred to negotiate, contest, or reject it. But nearly

everyone came to understand and explain masculinity on a spectrum that ran from

modern to traditional. This new binary mapped onto older binariesmasculine/feminine,

moral/immoral, respectable/disreputable, normative/deviant, etc.and intersected with

longstanding social distinctions based on gender, race/ethnicity, and class in different

ways. These mappings and intersections produced a dizzying array of contradictory,

shifting, and flexible masculinities or masculine scripts that ranged from the manly

charro (cowboy), associated with tradition-bound rural men, to the effeminate catrn

(dandy), associated with modern bourgeois male self-indulgence; from the despised

pelado (bum), associated with allegedly lazy urban poor men, to the patriotic obrero

(worker), associated with modern productive male citizens; from the passive indio

(Indian), associated with generations of downtrodden colonial subjects, to the energetic

mestizo (person of mixed race), a masculine type that included Porfirio Daz himself, the

paragon of modern manhood.

A Conceptual Framework for Studying Men as

Men

Any attempt to explain how Mexicans in the Porfirian era made sense of masculinity

hombra or manhood is the word they would have usedmust begin with some basic

concepts. Perhaps the most important and most basic of these concepts is that

masculinity is a social construct rather than a natural condition. A social constructionist

view of masculinity insists that broadly accepted if often contradictory understandings of

what it means to be a man derive from social and cultural practices rather than from

predetermined behaviors produced by genital difference, genetic coding, and hormonal

secretionsalthough these may indeed have an influence on the way masculinity is

socially constructed. As a social construct, masculinity has a history and thus makes

sense only in historical context. It is also situational in that what it means to be a man is

understood differently in different social situations, in different places, by different

people, and even by the same person in different contexts.

Page 2 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

Another basic concept is hegemonic masculinity. Associated with the work of influential

masculinity studies theorist R. W. Connell, the concept of hegemonic masculinity seeks to

explain how normative notions of masculinity privilege some expressions of masculinity

over others and how privileging these normative masculinities ensures the patriarchal

dominance of some men over women, children, and other men (who are sometimes

feminized in the process). Connells use of the word hegemony highlights two important

things: the role that masculinity plays in maintaining social hierarchies and other unequal

power relations as well as the wide acceptance of these inequalities as the byproduct of

the natural superiority of normal men. Although some scholars have rightly noted

that the notion of a single hegemonic masculinity lends itself to ahistorical analysis and

overgeneralization, Connell and his colleague James Messerschmidt argue persuasively

for the concepts continued relevance. They note that fundamental features such as the

plurality of masculinities and the hierarchy of masculinities as well as the idea that the

hierarchy of masculinities is a pattern of hegemony, not a pattern of simple domination

based on force, have stood the test of time.1 As part of their reformulation of the

hegemonic masculinities concept, Connell and Messerschmidt add another caveat that

masculinity scholars do well to bear in mind: [although] hegemonic masculinities can be

constructed that do not correspond closely to the lives of any actual men . . . these

models do, in various ways, express widespread ideals, fantasies, and desires. They

provide models of relations with women and solutions to problems of gender relations.

Furthermore, they articulate loosely with the practical constitution of masculinities as

ways of living in everyday local circumstances.2 In other words, while hegemonic

masculinities invariably shape the way men understand themselves and are understood

by others as men, they rarely reflect the real life experiences of most men.

As the concept of hegemonic masculinity makes clear, whatever their form, masculinities

are constructed through difference and against a constitutive outside composed of

excluded traits and practices that mark the boundaries of any given masculinity. This

process invariably invokes some sort of binary opposition: masculine/feminine, active/

passive, heterosexual/homosexual, moral/immoral, respectable/disreputable, strong/

weak, brave/cowardly, productive/lazy, and so on. At one level, binary oppositions clarify

social categories by explaining what things are in relation to what they are not. At

another, they represent crude attempts to gloss over the complex issues of identity and

subjectivity that characterize individual experience. At yet another, they reflect the all-

too-human desire to create a stable sense of self and the selves of others in order to

understand our place in the world and theirs. Whatever its virtues or flaws, the human

propensity for making sense of things, including ourselves and each other, through binary

oppositions provides historians with a valuable window into the ways in which people in

the past have perceived their world. It may be impossible to discover the meaning of

subjective real-life experiences that even individuals caught up in them struggle to

Page 3 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

understand. Nonetheless, creative use of historical sources and theoretical insights into

the social construction of masculinities can help historians recover the cultural logics that

people in the past used to make sense of themselves, other people, and their social world.

A final concept essential to understanding Porfirian masculinities is modernity, a

notoriously slippery term that scholars in a range of disciplines use to distinguish

modern societies from their traditional predecessors. Different scholars have focused

on different aspects of modernitytechnological change, global capitalism, large-scale

labor migrations, industrialization, bureaucratization, democratic institutions, increased

social complexity, and so on. Still, most agree that the concept revolves around a so-

called modern perspective that stresses the contingent nature of knowledge and thus

generates an ongoing process of revision in the way people understand and experience

the world. Like other social constructs, modernity is produced through binary opposition.

Thus people, societies, and even civilizations are considered modern (seen as dynamic

and oriented toward the future) precisely because they are no longer held back by

tradition (seen as static and oriented toward the past). In this sense, Porfirian mottos

like Order and Progress and Less Politics, More Administration, reflect the regimes

recognition that the construction of a modern nation-state meant transcending a tradition

of political instability, economic insecurity, social stagnation, and cultural stasis. But if

Porfirian ideologues promoted modernity as a source of dynamism, for most Mexicans it

was also a source of social and cognitive instability that could be exhilarating or

terrifying or both at the same time.

The interplay of binary oppositions in producing and sustaining masculinities (and other

social constructs) renders them inherently unstable, even when supported by

longstanding tradition. For a society such as Porfirian Mexico, caught up in a perceived

transition from a static past to an uncertain future, the inherent instability of masculinity

became a subject of conscious concern rather than sublimated anxiety. Sometimes it rose

to the level of a full-fledged moral panic. More than at any previous time in Mexican

history, then, being a man in the Porfirian era meant engaging with new modern forms

of masculinity that were, by definition, susceptible to perpetual revision and disturbing

contradiction.

A Model for Modern Manhood

The 19th century in Europe and the Americas was a period of transition characterized by

the uneven but implacable rise of the middle classes, especially the elite bourgeoisie. In

order to consolidate bourgeois hegemony, ideologues relentlessly contrasted their

enlightened ideas of progress with the deliberate obscurantism of an ancien rgime (old

Page 4 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

order), which sought to bind the common people to traditional institutions such as the

Catholic Church, absolutist monarchy, and hereditary nobility through a combination of

ignorance, superstition, and repression. Attacking the legitimacy of these bastions of

institutional patriarchy was a risky proposition that threatened to undermine all social

hierarchies, as the more radical phases of the French Revolution had made all too

apparent. Bourgeois hegemony thus required, among other things, a reformulation of a

traditional patriarchy grounded in discredited institutions, inherited social status, and

religiously sanctioned gender roles. And the reformation of patriarchy meant reworking

traditional notions of masculinity. This was especially true for places like Mexico,

assumed even then to be suffering the pernicious effects of predatory masculine types

such as the ruthless caudillo (strongman), rapacious rural bandit, and urban ratero

(represented as a lower-class, mestizo man predisposed to begging, petty theft, and

violence).3

To instruct upwardly mobile middle-class men in the ways of modern masculinity, a new

generation of enlightened letrados (men of letters) turned to a tried and true method for

civilizing aristocratic courtiers and religious devotees: the self-improvement manual.

The most popular of these guides in Porfirian Mexico was the Manual de urbanidad y

buenas maneras (Manual of Urbanity and Good Manners), first published in 1854 by

Manuel Antonio Carreo, a prominent Venezuelan statesman, diplomat, and pedagogue,

and reprinted regularly throughout Latin America ever since.4 For the Porfirian

bourgeoisie, Carreos Manual de urbanidad provided essential and exhaustive

instruction in proper forms of comportment for men, women, and children at home and in

public. Although modeled on aristocratic self-help manuals, unabashed in its religious

moralizing, and unconcerned about entrenched social hierarchies, the Manual de

urbanidad nonetheless espoused a reformation of traditional manhood predicated on

cleanliness, good grooming, moderation, affability, respectability, love of country, and

careful attentiveness to the needs and opinions of others, including women, children, and

social inferiorsan approach that artfully combined longstanding notions of masculine

responsibility and authority with modern ideas about self-mastery and citizenship,

especially the sublimation of volatile passions in all domains of social life. According to

Carreo, the fate of civilization itself was at stake. As he explained in the introduction:

Without knowledge and practice of the laws prescribed by morality, there can be no

peace, nor order, nor happiness among men; and in vain would we seek to find in another

source the true constitutive and preservative principles of society that we propose to

study; and the rules that [these laws] teach us about how to conduct ourselves in

[society] with the decency and moderation that distinguish the civilized and cultured

man.5

Page 5 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

After decades of political turmoil in Mexico, Porfirian letrados found Carreos

prescription for civilizing unruly male behavior both compelling and useful. Bourgeois

parents went out of their way to socialize their sons according to these precepts.6 And

Education Secretary Justo Sierra, one of President Dazs most prominent and

progressive cientfico advisers, even incorporated a simplified version of Carreos

precepts into the elementary school curriculum, with each month of the year dedicated to

fostering a different aspect of urbanity.7 Nonetheless, the elaborate instructions laid out

in the Manual de urbanidad were beyond the capacity of most men to realize. And if their

behavior is any indication, many bourgeois men bridled at its severe constraints on their

private and public behaviorand the constant self-policing involvedalthough they may

have derived some comfort from its overt endorsement of a moral double standard that

weighed far more heavily on the women in their lives. For men with fewer resources and

less social status, adhering to Carreos exacting standards was next to impossible. As a

masculine ideal, this image of the civilized and cultured male had much to recommend

it, especially its meticulously crafted appearance of mental acuity (wit), emotional

equanimity (affability), and physical grace (health), which revealed the natural

superiority of the men who appeared to have achieved it.

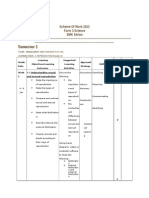

It is hardly surprising, then, that publicity photographs of prominent members of the Daz

administration, including of course the president himself, went to great lengths to

capture the studied urbanity of their subjects. For example, a period photograph of

Finance Secretary Jos Yves Limantour seated in a rattan chair on an outdoor patio,

looking self-assuredly at the camera, depicts him as a paragon of modern bourgeois

manhood: gracefully posed, impeccably groomed, and dressed in the height of continental

fashion.

Page 6 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

Another period

photograph, this one of

Porfirio Daz accompanied

by his wife, Carmen

Romero Rubio, at the

extravagant 1910

centenary celebration of

independence, adds a

feminine touch to the

public persona of the

indispensable caudillo,

hinting at a domestic

haven that provided him a

refuge from the trials and

Click to view larger tribulation of public life

Figure 1. Finance Secretary Jos Yves Limantour. an essential and formative

Library of Congress. female complement to

modern manhood as

described (and prescribed) by Carreo and other arbiters of taste.

These images suggest that

unrealistic as the

prescriptions of self-

improvement guides like

the Manual of Urbanity

undoubtedly were, they

nonetheless represented a

hegemonic masculine

ideal, consciously

embodied by influential

Click to view larger men who presented

Figure 2. President Porfirio Daz and his wife, themselves as role models

Carmen Romero Rubio, at the 1910 centenary for other men. And if

celebration of Mexican independence. Library of

Congress.

public opinion werent

incentive enough,

legislation, especially the 1871 Penal Code, provided legal sanctions for masculine (and

feminine) behavior that failed to live up to modern standards of proper comportment,

especially the need for self-control and moderation in public and private life.8

Page 7 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

Ghosts in the Machine

The modern masculine ideal prescribed by self-improvement manuals and referenced in

period photographs of influential public men was not the only hegemonic masculinity at

work in Porfirian Mexico. Indeed, the image of Porfirio Daz and his wife surrounded by

uniformed military officers also referenced the presidents past exploits as a ruthless man

of action capable of personal heroism, implacable judgment, and sudden outbursts of

anger at challenges to his authority. In this particular case, Dazs transformation into a

distinguished, even-tempered elder statesmanattributed by many to the civilizing

influence of Doa Carmensymbolized the maturation of Mexico into a modern nation.

But not all men had the prestige to withstand the unintended, albeit foreseeable,

consequences of modern manhood.

As happened with other traditional patriarchal ideas, longstanding links between notions

of manhood and concerns about masculine honor and reputation in Mexico (and

elsewhere) underwent significant revision over the course of the 19th and into the 20th

century. And the modern incarnation of those linkages, which based reputation on

precarious merit rather than preordained social position, was reiterated ad nauseam in

19th-century self-improvement manuals. The compulsive reiteration of new masculine

ideals had an anxious, defensive quality that reveals fundamental instabilities at the heart

of modern manhood derived directly from its efforts to soften the hard edges of

traditional hegemonic masculine types.

For proponents of the reformation of manhood, the struggle to supplant traditional

masculinities was serious business; less invested observers saw it as a rich source of

satire. For example, a popular broadside illustrated by master printmaker Jos Guadalupe

Posada, Nuevos y divertidos versos de un valiente del Bajo a sus valedores (New and

Entertaining Verses of a Brave Man of Bajo to his Buddies), depicts a stereotypical

charro (cowboy), dressed in traditional regalia with a horse whip in one hand and the

reins of a snorting stallion in the other, as he challenges a billiard hall full of bewildered

city boys with an offer to put their women in the family way and the assertion that Im

your papa, hotshots/The one you must respect/So dont muddy the water boys/Because

thats the way youll have to drink it.9

Page 8 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

The broadside derives its

humor from the binary

opposition between

modern masculinity in the

guise of hatless billiard

playing chulos (hotshots)

and its traditional

counterpart cast as a

boastful charro with a

bristly mustache and wide-

brimmed sombrero, the

classic symbol of manhood

and national identity.10

The binary opposition

Click to view larger

expressed in New and

Figure 3. Nuevos y divertidos versos de un valiente

del Bajo a sus valedores (New and Entertaining

Entertaining Verses

Verses of a Brave Man of Bajo to his Buddies), carried over into other

broadside printed by Jos Guadalupe Posada. masculine domains.

University of Hawaii, Jean Charlot Collection.

Porfirian modernizers

tended to see modern male

sports like baseball, boxing, bicycling, and billiards as civilized (regulated, hygienic,

healthy) and traditional male entertainments like rodeo, bullfighting, and cockfights as

savage (improvisational, bloody, inflammatory).11 But even hardcore bullfight fans

interpreted the distinctive styles of the dandified, clean-shaven Spanish-born matador,

Luis Mazzantini, and his hard-drinking, mustachioed Mexican-born colleague, Ponciano

Daz, in terms of competing masculinities along the modern/traditional binary and aligned

their sympathies accordingly.12 Although the billiard players in Posadas print might

construct themselves as modern men in opposition to rural masculine stereotypes like the

boastful charro from Bajo, the broadside also hints at a certain loss of manliness as they

sublimated natural male aggression in order to embrace a tame urban lifestyle

characterized by civilized games like billiards. A similar dynamic appears in the cultural

wars around the bullfighting styles of Mazzatini and Daz, with upper-class aficionados

more likely to favor the urbane Spaniard and the satiric penny press for workers

advocating for the earthy Mexican. New masculine types such as the lagatijo (literally

lizard) and the catrn (dandy) emerged as way to identify, satirize, and sometimes

feminize this new generation of cosmopolitan middle- and upper-class men.

These Porfirian culture wars around masculine style had quite a bit to do with changing

ideas about gender, consumption, and citizenship. For example, the central plot of liberal

Page 9 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

letrado Ignacio Altamiranos popular 1901 novel, El Zarco, revolves around a competition

between two distinct masculine typesthe flashy bandit El Zarco and the steady

blacksmith Nicolsfor the attentions of the beautiful Manuela. In addition to the

obvious psychological differences between the cruel, capricious El Zarco and the

considerate, constant Nicols, the two men are distinguished by distinct modes of

production and consumption. At one level, El Zarco and Nicols represent pre-modern

and modern masculine types, at another the two men embody two mutually exclusive

possibilities at the heart of the modern project . . . a future (desired) dominated by

production as the determining characteristic of masculine identity . . . face to face with a

future (exorcized) dominated by unproductive consumption and ostentation.13 In the eyes

of Altamirano and his fellow letrados, the key to Mexicos future lay in the triumph of

productive citizens like the upstanding mestizo Nicolswho ultimately rejects the

feckless gera (blonde) Manuela for the modest mestiza Pilarover the destructive gero

bandit El Zarco. The novel ends predictably enough with the deaths of El Zarco and

Manuela and the marriage of Nicols and Pilar, a symbol of the happy future promised to

and produced by modern masculine and feminine subjects (and their inevitably patriotic,

industrious offspring). At the same time, the novels pro-mestizo politics, not uncommon

among Mexican letrados, fly in the face of the scientific racism of the day and other

imported notions of modernity tainted by white supremacy. The racial politics of

nationalismexpressed in El Zarco and the Mazzatini/Daz split, and embodied by the

charro from Bajo and a mestizo president (despite efforts to whiten his public image)

would continue to haunt attempts to reform manhood by calling into question the virility

of civilized and cultured men, even for bourgeois men otherwise eager to distance

themselves from lower-middle-class and working-class men.

Complications related to the racial politics of nationalism were not the only source of

tension for Porfirian men as they sought to adapt to the modern world. Although

Altamirano sets his novel in rural Morelos, the centrality of consumption to modern

identity was probably felt most acutely in Mexicos rapidly growing urban centers,

especially by middle-class men. By the end of the 19th century, the proliferation of

upscale urban department stores such as Mexico Citys famous Palacio de Hierro (Iron

Palace) and the development of fashionable shopping and entertainment districts

provided the middle and upper classes with exposure and access to the latest

cosmopolitan stylesand helped them cultivate a new modern and intensely gendered

class identity grounded in their ability to acquire and deploy a material culture of

European provenance, even if at times it relied on cheap, domestically-produced copies

and brands.14 Conspicuous consumption of fashionable clothing, accessories, beauty

products, cigarettes, alcohol, and entertainment was expensive and often strained the

resources of the growing but still precarious middle class, the very group most desperate

to maintain its status as gente decente (decent folk). And the anxieties produced by new

Page 10 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

patterns of consumption proved especially troubling for middle-class men, who struggled

to live up to the financial demands of modern masculinity, including an obligation to meet

the consumption needs of their wives and children.

The conspicuous consumption essential to constructing and projecting a modern

masculine persona intersected in complicated ways with changing notions of male honor.

While bourgeois and aristocratic men from influential families inherited honor as a

birthrightalthough some managed to fall into disgrace nonethelessless established

middle-class men worked hard to acquire and maintain their reputations. No group felt

this pressure more acutely than a new generation of contentious combat journalists,

whose public reputations as men of honor were essential to their precarious social

position. This meant that, any doubt about their integrity prompted strong rebuttals,

often leading to verbal and printed insults or the threat of violence through a duel.15 Few

public disputes ended in formal duelsalthough future Education Secretary Justo

Sierras brother Santiago was killed in a duel by a rival newspaper editorbut the threat

of violence to avenge affronts to personal honor was a serious occupational hazard until

the late 1890s, when a combination of government subsidies, press censorship, and

outright repression put a severe damper on journalistic debate.16 Because of its

dependence on reputation and public opinion, the modern honor espoused by middle-

class men such as the combat journalistsalthough more democratic and meritocratic

than its traditional predecessorwould prove even more volatile and no less hegemonic,

despite its contradictory effects on other more civilized ways of being a man.

Variations on a Theme

Then as now, a mans ability to convincingly assume, perform, or embody hegemonic

masculinity required a sense (or at least credible pretense) of mastery of oneself and

other peoplewomen, children, and less powerful men. While men of means, however

modest, could at least aspire to some degree of mastery, this was not a realistic option for

many of their less well off brethren. Working-class Mexican men have long been cast as

prototypical machosa stereotype bolstered by the widespread use of the Spanish-

language term, which acquired its current meaning in Mexico sometime in the mid-20th

century.17 Whatever truth might lurk behind the stereotype, a close look at Porfirian-era

popular culture, especially the vibrant Mexico City satiric penny press for workers,

provides a more nuanced view of Mexican working-class masculinities. The satiric penny

press occasionally endorsed a gamut of traditional macho behaviors that ran from

patriarchal condescension to outright violence. A poem from El Diablito Rojo (The Little

Red Devil) advised readers that, every good woman sews, washes, irons, and cooks.18

Page 11 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

Another ominously warned men who had been betrayed by deceitful womena

reoccurring theme in penny press poetrythat when it has to do with love/he thats not

a fool, prefers/to the blow from which he dies/the blow with which he kills.19

At the same time, penny press editors understood the humor inherent in working mens

struggles with the particular (not to say peculiar) demands of modern manhood. A La

Guacamaya (The Squawking Parrot) story about a temporarily unemployed workerwho

turns out to be the editors alter egoculminates with a ghostly late-night visitor whom

he initially confuses with Don Gonzalo, the murdered father-in-law who comes to drag

Don Juan Tenorio off to hell in the popular play of the same name, traditionally performed

each year throughout Mexico as part of the Day of the Dead festivities. He confronts the

specter with Don Juans blustery lines: Dont think that you can scare with your

fearsome looks, with your remorseless face, never in death nor in life will you humiliate

my valor, only to discover that the figure is just his long-suffering wife come to beg a

ships ration of bread and water. And for all his posturing, he confesses to having

hidden his head under a sleeping mat the entire timea cowardly act that makes him a

sympathetic character but hardly a paragon of manly self-control or even an effective

breadwinner. Along with satirizing the trials and tribulations of non-elite men, penny

press editors sometimes represented working-class men as more modern than their

middle- and upper class counterparts, at least with regard to gender relations. A 1905

cover for El Chile Piqun (The Spicy Pepper), illustrated by Posada, depicts a scruffy

working-class man with sandals, rolled-up pants, straw hat, and the gear of a cargador

(hauler) slung over his back, talking with a frumpy woman with missing front teeth on her

way to market.

Page 12 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

The dialogue below the

image, written in street-

inflected Spanish, alerts

readers to a budding

romantic relationship:

Man: Where are you

going Doa Manuela?

Woman: Im going to

the plaza, Perfirio.

Youre just flirting with

me.

Man: Its that Im crazy

about you.

Click to view larger

Figure 4. El Chile Piqun (The Spicy Pepper), Woman: Dont be such

January 12, 1905. University of Texas at Austin,

Benson Latin American Collection. a flatterer.

Man: And you dont be

such a tease.

Woman: (How smooth this guy is.)

Man: (How ripe this honey seems.) Are you going with me my love?

Woman: Yes, Perfirio even into hell.

Man: Well now, I really am going to laugh at the harshness of winter.

The humor in this exchange derives from the cognitive dissonance created by their frank

expression of mutual desire (especially in the unspoken parenthetical thoughts) and their

decidedly unsexy appearance. Notable as well is the absence of any hint of male

dominance or female subordination, even with regard to the expression of sexual desire

in the final lines when Perfirio takes comfort in the prospect of bodily contact as

protection against the cold of winter. The promise of egalitarian or companionate

relationships between working-class men and women, relationships grounded in

emotional bonding and sexual attraction, puts them at the forefront of modern ideas

about love and marriage that anthropologists have argued would not occur among the

Mexican working classes until late in the 20th century.20 Nonetheless, as this fictional

encounter suggests, while working-class men might lack the means to purchase a modern

Page 13 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

persona or to pretend to self-mastery along the lines suggested by Carreos Manual of

Urbanity, they could aspire to be modern in other, more authentic ways.

One explanation for this counterintuitive view of working-class men as harbingers of

modernity is the expansion of literacy among the lower classes over the course of the

19th century. This expansion included access to literary culture even for men considered

illiterate by conventional standards. With it came a newfound ability to communicate

indirectly and discreetly with potential partners, sometimes despite the best efforts of

concerned parents to safeguard their daughters, as in this letter from a working-class

Guadalajara man to his sweetheart:

I dont want you to have any illusions about a man that you only know

superficially, and that you dont understand . . . because if Im a man I also know

that I have to suffer now to enjoy later, I dont want you to think I will make you

happy, when on the contrary you have to suffer a little until I change, which is to

say, until you make me change by the way you sweeten life, but this will be later,

for now I only want that you be with me because I know that I have a right to your

help and you will teach me to love you more so that you can live in tranquility

when youre older.21

Although the letter reflects a more traditional view of companionate relationships than is

implied by the El Chile Piqun cover, it nonetheless reveals that working-class men and

women used letters to foster and strengthen their emotional bonds through dialogue in a

way that they seem to have understoodjudging from frequent references to tradition-

bound parentsas modern.

Men in rural areas were also at a disadvantage when it came to a taking on a modern

masculine identity. Reasons varied: some rural men were as poor as their urban

counterparts, others lacked easy access to consumer goods, and still others found rural

communities less amenable to new cultural mores associated with modern urban

lifestyles. By the late 19th century, modern technologies like the railroad and telegraph

along with improved roads and a more reliable postal service had helped spread

consumer goods and modern ideas to all but the remotest corners of Mexico. In addition,

modernizing industries like mining and agriculture (in some areas more than others) had

begun to promote new forms of labor discipline among workers that soughtwith limited

successto rid men of traditional vices such as drinking, frequenting prostitutes, and

idleness and replace them with healthy modern habits, especially industriousness.22 As

happened in urban areas, rural men were more likely to construct themselves as modern

subjects through the circulation of letters than through the prescriptive literature of

bourgeois reformers. An impassioned letter from an absent mineworker to his novia, for

example, begins by telling her that you cant imagine what this poor heart has suffered

Page 14 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

for your love, before reassuring her with the, tranquility your passionate Pedro finds

when turning to write you with such growing and sweet love.23 Here again, the

passionate sentiments arent especially modernespecially considering the implication

here and in other places in the couples correspondence that suggests loss of self-control

on the part of both partiesbut the medium certainly is, at least for a working-class man.

So too is the notion that couples could work on their relationship through the exchange of

letters.

Historians know next to nothing about the intersections of manhood and modernity

among indigenous men. The letrado elite typically portrayed them in two very different

ways. Indian men living in settled areas, especially the central plateau, were frequently

represented as passive and weak to the point of possible extinction. An 1878 medical

study, for example, observed of the typical highland Indian: his constitution is generally

weak, his muscles little developed and his material work relatively minimal. His

complexion is pallid and yellowish, his face sullen, his air is sad and pensive, his step slow

and always with a reflection of melancholy vacillation.24 In contrast, Indian men who

actively resisted the encroachments of the Porfirian state were depicted as savages,

whose violent lack of masculine self-restraint stood in the way of national progress.

In both instances, they

were seen as stubbornly

attached to their

traditional way of life.

Justo Sierra may have

fretted about the difficulty

of harnessing the

destructive tendencies of

the energetic mestizo

(mixed race) men who

represented the nations

dynamic future, but when

it came to Indian men, his

favored solution was

Click to view larger

immigration, because only

race mixture with

Figure 5. Two Tarahumara Indian men,

photographed in Tuaripa, Chihuahua, Mexico, 1892. European whites could

Wikimedia Commons. prevent our nation from

sinking, which would mean

regression, not evolution.25 Men of other racial groups faced similar, if less relentless,

stereotyping and not just at the hands of letrado nation-builders. Images of Chinese men

Page 15 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

harassed by angry mobs in the popular press reveal the centrality of masculine normsas

reflected in an emphasis on the traditional physical appearance, dress, and demeanor of

Chinese menin discriminatory attitudes toward foreigners of other races.

Even the symbolic

embodiment of U.S.

power, Uncle Sam, was

often cast as a Semitic

villain in Mexican popular

culture, a traditional

masculine type associated

with blood libel and

usurious business

practices.26

Click to view larger

Figure 6. La Guacamaya (The Macaw) newspaper,

August 18, 1904. University of Texas at Austin,

Benson Latin American Collection.

Deviant Masculinities

The development of new forms of hegemonic masculinity also produced new forms of

deviant masculinity. In many cases, these deviant masculinities emerged as protests

against the constraints imposed on men by the normative demands of the dominant

culture. And as protest masculinitiesanother term developed by R. W. Connellthey

deliberately rejected the core values associated with hegemonic masculinities. This often

meant embracing some unsavory aspects of traditional masculinities (as caricatured by

progressive social reformers). For example, the flashy bandit, El Zarco, mentioned earlier

in relation to competing modes of masculine consumption, embodies a classic protest

masculinity grounded in arrogance, irresponsibility, cruelty, and a preference for easy

money attained through robbery and extortion rather than an honest living earned

through hard work. Indeed, the rejection of modern values like industriousness, thrift,

hygiene, self-restraint, and delayed gratification formed the basis of most protest

masculinities.

Page 16 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

Other examples include much-maligned pelados like the drunken Lazarus in a Posada

illustration for La Guacamaya roused by an annoyed policeman while sleeping off a drunk

in the street.

Urban masculine types like

the pelado and ratero

represented a blatant

refusal to adhere to the

disciplinary norms of an

aspiring industrial society

on the part of working-

class men, many of whom

experienced the wrenching

disruptions of modernity

but few of its benefits.

Sometimes penny press

Click to view larger

editors went so far as to

Figure 7. La Resurreccin de Lzaro (The

Resurrection of Lazarus), illustration from La suggest that working-class

Guacamaya (The Macaw) newspaper. University of male rowdiness, at least in

Texas at Austin, Benson Latin American Collection. the context of patriotic

celebrations like

Independence Day, was preferable to the passive propriety of bourgeois men who they

branded as catrines.

Page 17 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

On the other hand, self-

identified bohemios

(bohemians) from the

upper and middle classes

often labeled as catrines by

their working-class

brethrenshared some of

this deep distrust of

hegemonic masculine

ideals, which they

considered puritanical,

bland, and overly

materialistic.

Another protest

Click to view larger

masculinity, the tenorio del

Figure 8. La Guacamaya (The Macaw) newspaper,

barrio (neighborhood

September 12, 1907. University of Texas at Austin,

Benson Latin American Collection. lothario) appeared in all

sectors of Porfirian

society, following proudly in the footsteps the notorious Don Juan Tenorio, whose

obsession with masculine honor, the seduction of women, and the deliberate flouting of

convention, had allegedly inspired generations of men to disrespect authority, women,

and any man who might challenge them.

Page 18 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

Male sexual inversionthe

late19th-century term for

men who took on female

gender and sexual

personaswas probably

the most stigmatized of the

deviant masculinities to

emerge during the

Porfirian era in Mexico,

perhaps because it was

seen as a modern

perversion rather than a

traditional throwback.

Ascribing alleged female

traits such as passiveness,

Click to view larger

flightiness, pettiness,

Figure 9. Yo so Don Juan Tenorio y sin

Quimeras (I am Don Juan Tenorio without weakness, etc. to other

Chimeras). University of Hawaii, Jean Charlot men in order to demean,

Collection.

humiliate, undermine, or

dominate them was hardly

a 19th-century invention. Popular culture also had a centuries-old tradition of male cross-

dressing in the theater and circus and for special occasions like the carnival that marked

the coming of Lent. These longstanding theatrical traditions carried over into political

satire as when El Diablito Rojo ran a 1900 cover illustration, cross-dressing President

Porfirio Daz himself as a zarzuela (operetta) heroine being courted by his/her admirers.27

Page 19 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

That a lowly penny press

editor could cast Mexicos

powerful president as a

woman on the front page

of his newspaper without

landing in jail suggests

that the practice was

considered unremarkable.

Tolerance for these

traditional practices did

not carry over to men who

preferred sex with other

men, especially if they

Click to view larger

openly solicited sex from

Figure 10. El Diablito Rojo (The Little Red Devil)

other men or took the

newspaper, July 2, 1900. University of Texas at

Austin, Benson Latin American Collection. female (passive) role in sex

acts. Historians have

begun to uncover evidence of what would now be called a homosexual subculture in

Porfirian-era cities, especially with regard to the modern bathhouses that began to

appear during the 1890s in order to promote hygienic habits.28 Although an undeniable

aspect of urban life and an area of official concern, for the most part this hidden world of

sexual inversion and homosexual practices was very much in the closet. That changed on

November 17, 1901, when Mexico City police raided a private dance and arrested 41

participants, half of whom were dressed as women. News accounts of the raid quickly

generated a public scandal that grew so big that the number forty-one became and

remains a code for male homosexuality throughout Mexico. For many critics, including

the moralistic Catholic newspaper El Pas, the raid revealed the state of immorality to

which the execrable influx of impiety has led.29 Indeed, most newspaper editorials

applauded the governments decision to deport the men who had dressed as women (but

not the others) to Yucatn to work in military mess halls (as servers rather than as

soldiers). For the satiric penny press editors, the forty-one scandal provided the perfect

opportunity to further attack the manhood of bourgeois catrines as effeminate,

narcissistic, weak-willed, and thus unfit to lead the nation. For instance, a 1907 cover for

La Guacamaya with the provocative title Feminism imposes itself depicted feminized,

presumably middle-class men positioned around a huge number forty-one, dressed in

womens clothing and performing a range of household tasks.

Page 20 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

The caption underneath

read:

While the woman goes

off

To the workshop and the

office

And dresses in cashmere

And abandons the home

And enters freely into

bars,

The clean-shaven man

Stays at home making

breakfast,

He sews, irons, and

cares for the baby,

Click to view larger And all of them with

Figure 11. La Guacamaya (The Macaw) newspaper, great affection (?)

July 25, 1907. University of Texas at Austin, Benson We call forty one.

Latin American Collection.

While there is no hint of

homosexual acts here, the modern middle class men that it represents at home doing

womens work while their wives are off at the office and entering freely into bars are

nonetheless stigmatized as sexual inverts by their association with the notorious number

forty-one. But if the forty-one scandal helped to alert authorities and the public to the

homosexual problem and to shape a particularly Mexican brand of homophobia, it also

gave gay men a sense of identity and common cause that some scholars have seen as the

birth of homosexuality in Mexico.30 And from that birth sprang a powerful new binary

opposition against (or through) which men could understand themselves and other men

as menan opposition that came not from traditional masculinities but from within

modernity itself.

Discussion of the Literature

The historical literature on men and modernity in the Porfiriato is spotty: relatively well

developed in some areas and virtually nonexistent in others. Regardless, it owes a huge

debt to several decades of important work by feminist scholars whose pioneering

histories of women, gender, and sexuality during the Porfirian era laid the theoretical and

contextual groundwork for these more recent efforts to historicize masculinity. Although

Page 21 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

space constraints make it impossible to discuss this extensive bibliography here, any

serious scholar would be advised to read deeply in this literature and consult it often.

Given its provenance in women, gender, and sexuality studies, it is hardly surprising that

the earliest systematic attempts to analyze Porfirian masculinity would be undertaken by

historians interested in homosexuality and homophobia. The seminal work in this sub-

field is The Famous 41: Sexuality and Social Control in Mexico, c. 1901, edited by Irwin,

et al., which includes several primary sources along with a range of historical essays on

the scandal and on the links between the policing of deviant sexualities and other forms

of social control in the Porfirian era. Articles and books by some of authors in that volume

(Irwin, Macas-Gonzalez, Macas-Gonzlez and Rubenstein, and Buffington); the work of

other historians of sexuality, such as Cano and Barrn Gavito; and a new dissertation by

Jones have given historians a solid foundation for future work on the history of

homosexuality in Porfirian Mexico. Another relatively well-developed sub-field that

emerged from feminist gender and sexuality studies involves the social construction of

modern hegemonic masculinities, through the widespread use of self-help manuals,

especially among the Porfirian middle-classes (see the work of Macas-Gonzlez and of

Barcel) and through cultural wars that pitted traditional masculine types such as the

bandit and the charro against their modern counterparts, explored by Vazquez M.,

Palomar Verea, and Dabove and Hallstead. Recent work by Piccato on changing notions

of masculine honor has revealed some of the challenges of hegemonic masculinity for

middle class men.

Cultural and legal historians focused on the social construction of deviance have also

made solid contributions to the study of Porfirian masculinities, especially official

concerns about the criminality of lower-class men and the degeneration of middle- and

upper-class men; see the work of Piccato, Buffington, and Speckman Guerra. Labor

historians interested in working-class culture, such as Miranda Guerrero, Buffington,

French, and Lear, have taken this work a step further by looking at other aspects of

working-class masculinity, including working-class perspectives on manhood. A final

important subfield involves the study of rural masculinities as revealed in court records,

especially with regard to issues of courtship, seduction, honor, and violence against

women (see the work of French and of Sloan).

As this brief overview of the literature on Porfirian masculinities reveals, the field is still

in its infancy. Not only does much work remain to be done in the sub-fields noted but

many important aspects of the impact of modernity on men during the Porfirian era have

yet to be explored in any detail. These include: upper-, middle-, and lower-class mens

responses to new patterns of leisure and consumption; the sexual politics of modern

sports; the way elite men negotiated and performed hegemonic masculinity; the

implications of new forms of hegemonic masculinity for middle-class men; and the impact

Page 22 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

of new forms of hegemonic and protest masculinities on upper-, middle-, and lower class

women, to name only a few.

Primary Sources

Period newspapers, magazines, and broadsheets are essential sources for the study of

Porfirian-era masculinities. The two most comprehensive collections are in the

Hemeroteca Nacional Digital de Mxico, Mexico City and the Benson Latin American

Collection, University of Texas at Austin.

The work of master printmaker Jos Guadalupe Posada includes a wide spectrum of

masculine types, especially for the working classes. Important collections of Posadas

work can be found at the Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas at

Austin; the Jean Charlot Collection, University of Hawaii at Manoa; the Fernando

Gamboa Collection of Prints, University of New Mexico; Special Collections & University

Archives, Stanford University Libraries; and the Art Institute of Chicago.

The autobiographies, diaries, and other writings of elite men are another useful source.

These men include Porfirio Daz, Francisco Bulnes (journalist and politician), Salvador

Daz Mirn (poet and notorious duelist), Heriberto Fras (soldier, journalist, and novelist),

Federico Gamboa (novelist, diarist, and diplomat), Emilio Rabasa (writer, diplomat, and

politician), and Justo Sierra (writer, educator, and politician). See also: Manuel Antonio

Carreo, Manual de urbanidad y buenas maneras para el uso del juventud de ambos

sexos;31 Julio Guerrero, Gnesis del crmen en Mxico: Estudio de psiquiatra social;32 and

Carlos Roumagnac, Los criminales en Mxico: Ensayo de psicologa criminal.33

Further Reading

Agostoni, Claudia, and Elisa Speckman Guerra, eds. Modernidad, tradicin y alteridad: La

Ciudad de Mxico en el Cambio de Siglo (XIXXX). Mxico: Universidad Nacional

Autnoma de Mexico, 2001.

Barcel, Raquel. El muro del silencio: Los jvenes de la burguesa porfiriana. In

Historia de los jvenes en Mxico: Su presencia en el siglo XX. Edited by Jos Antonio

Prez Islas and Maritza Urteaga Castro-Pozo, 114150. Mxico: Instituto Mexicano de la

Juventud, 2004.

Barrn Gavito, Miguel Angel. El baile de los 41: La representacin de lo afeminado en la

prensa porfiriana. Historia y Grafa 34 (2010): 4776.

Page 23 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

Buffington, Robert M. Criminal and Citizen in Modern Mexico. Lincoln: University of

Nebraska Press, 2000.

Buffington, Robert M. A Sentimental Education for the Working Man: The Mexico City

Penny Press, 19001910. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015.

Cano, Gabriela. Unconcealable Realities of Desire: Amelio Robless (Transgender)

Masculinity in the Mexican Revolution. In Sex in Revolution: Gender, Power and Politics

in Modern Mexico. Edited by Jocelyn Olcott, Mary Kay Vaughan, and Gabriela Cano, 35

56. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006.

Dabove, Juan Pablo, and Susan Hallstead. Pasiones fatales: Consume, bandidaje y

gnero en El Zarco. A Contracorrientes 7.1 (Fall 2009): 168187.

Fernndez Aceves, Mara Teresa, Carmen Ramos Escandn, and Susie Porter, eds. Orden

social e identidad de gnero: Mxico, siglos XIX y XX. Mxico: CIESAS, 2006.

French, William E. A Peaceful and Working People: Manners, Morals, and Class

Formation in Northern Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996.

French, William E. The Heart in the Glass Jar: Love Letters, Bodies, and the Law in

Mexico. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015.

Irwin, Robert McKee. Mexican Masculinities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press,

2003.

Irwin, Robert McKee, Edward J. McCaughan, and Michelle Roco Nasser, eds. The

Famous 41: Sexuality and Social Control in Mexico, c. 1901. New York: Palgrave

Macmillan, 2003.

Jones, Ryan. Estamos en todas partes: Male Homosexuality, Nation, and Modernity in

Twentieth-Century Mexico. PhD Diss., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012.

Lear, John. Workers, Neighbors, and Citizens: The Revolution in Mexico City. Lincoln:

University of Nebraska Press, 2001.

Macas-Gonzlez, Vctor M. Apuntes sobre la construccin de la masculinidad a travs

de la iconografa artstica porfiriana, 18611914. In Hacia otra historia del arte en

Mxico: La amplitud del modernism y la modernidad (18611920). Edited by Stacie G.

Widdifield, 329350. Mxico: CONACULTA, 2004.

Macas-Gonzlez, Vctor M., and Anne Rubenstein, eds. Masculinity and Sexuality in

Modern Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2012.

Page 24 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

Miranda Guerrero, Roberto. Exploraciones histricas sobre la masculinidad. La Ventana

8 (1998): 207247.

Miranda Guerrero, Roberto. Gnero, masculinidad, familia y cultura escrita en

Guadalajara, 18001940. In Hombres y masculinidades en Guadalajara. Edited by

Roberto Miranda Guerrero and Luca Mantilla Gutirrez, 189249. Guadalajara:

Universidad de Guadalajara, 2006.

Palomar Verea, Cristina. El charro: Masculinidad y nacionalismo. In Hombres y

masculinidades en Guadalajara. Edited by Roberto Miranda Guerrero and Luca Mantilla

Gutirrez, 157188. Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara, 2006.

Piccato, Pablo. City of Suspects: Crime in Mexico City, 19001931. Durham, NC: Duke

University Press, 2001.

Piccato, Pablo. The Tyranny of Opinion: Honor in the Construction of the Mexican Public

Sphere. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010.

Sloan, Kathryn A. Runaway Daughters: Seduction, Elopement, and Honor in Nineteenth-

Century Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2008.

Speckman Guerra, Elisa. I Was a Man of Pleasure, I Cant Deny It: Histories of Jos de

Jess Negrete, a.k.a. The Tiger of Santa Julia. In True Stories of Crime in Modern

Mexico. Edited by Robert M. Buffington and Pablo Piccato, 57105. Albuquerque:

University of New Mexico Press, 2009.

Notes:

(1.) R.W. Connell and James W. Messerschmidt, Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the

Concept, Gender & Society 19 (2005): 846 (829859).

(2.) Ibid., 838 (829859).

(3.) On bandits as the constitutive outside of the modern nation-state see Juan Pablo

Dabove, Introduction, in Nightmares of the Lettered City: Banditry and Literature in

Latin America 18161929 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2007), pp. 140. On

elite concerns about urban rateros see Pablo Piccato, The Invention of Rateros, in City

of Suspects: Crime in Mexico City, 19001911 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2001),

pp. 163188.

Page 25 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

(4.) By 1992 Carreos Manual de urbanidad had gone through 47 editions. Elsa Muiz,

Cuerpo, representacin y poder: Mxico en los albores de la reconstruccin nacional,

19201934 (Mxico: Universidad Autnoma Metropolitana, 2002), p. 29. See also:Victor

M. Macas-Gonzlez, Hombres de mundo: la masculinidad, el consume, y los manuales

de urbanidad y buenas maneras, in Mara Teresa Fernndez Aceves, Carmen Ramos

Escandn, and Susie Porter, eds. Orden social e identitdad de gnero. Mxico, siglos XIX

y XX (Mxico: CIESAS/Universidad de Guadalajara, 2006), pp. 267297; and Valentina

Torres Septin, Manuales de conducta, urbanidad y buenas modales durante el

Porfiriato: Notas sobre el comportmento feminino, in Claudia Agostoni and Elisa

Speckman, eds. Modernidad, tradiccin y alteridad: La Ciudad de Mxico en el cambio

del siglo (Mxico: Universidad Nacional Autnoma de Mxico, 2001), pp. 271289.

(5.) Manuel Antonio Carreo, Manual de urbanidad y buenas maneras (Mxico: Librera

de la Vda. de Ch. Bouret, 1920), p. 5.

(6.) Raquel Barcel, El muro del silencio: Los jvenes de la burguesa porfiriana, in Jos

Antonio Prez Islas and Maritza Urteaga Castro-Pozo, eds. Historia de los jvenes en

Mxico: su presencia en el siglo XX (Mxico: Instituto Mexicano de la Juventud/Centro de

Investigacin y Estudios sobre Juventud/Archivo General de la Nacin, 2004), pp. 114

150.

(7.) Macas-Gonzlez, Hombres de mundo, pp. 280285.

(8.) Elisa Speckman Guerra, Las tablas de la ley en la era de la modernidad: normas y

valores en la legislacin porfiriana, in Claudia Agostoni and Elisa Speckman, eds.

Modernidad, tradiccin y alteridad: La Ciudad de Mxico en el cambio del siglo (Mxico:

Universidad Nacional Autnoma de Mxico, 2001), pp. 241270.

(9.) Author unknown/Jos Guadalupe Posada (illustrator), Nuevos y divertidos versos de

un valiente del Bajo a sus valedores (Mxico: Antonio Venegas Arroyo, 1902). Courtesy

of the Jean Charlot Collection, University of Hawaii (JCC.JGP:V47).

(10.) On the charro as national symbol see Cristina Palomar Verea, El charro:

masculinidad y nacionalismo, in Roberto Miranda Guerrero and Luca Mantilla

Gutirrez, eds. Hombres y masculinidades en Guadalajara (Guadalajara: Universidad de

Guadalajara, 20069, pp. 157188.

(11.) On the social meaning of sports in Porfirian Mexico see William H. Beezley, Judas at

the Jockey Club and Other Episodes of Porfirian Mexico (Lincoln: University of Nebraska

Press, 1987), pp. 1367.

Page 26 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

(12.) Although social reformers looked disparagingly on blood sports such as

cockfighting and bullfighting, the Daz regime lifted an earlier ban on bullfighting in

1886. On the competing masculine styles of Mexican matadors see Mara del Carmen

Vzquez M., Charros contra gentlemen: un episodio de identidad en la historia de la

tauromaquia mexicana moderna, 18861905, in Claudia Agostoni and Elisa Speckman

Guerra, eds. Modernidad, tradicin y alteridad: la Ciudad de Mxico en el Cambio de

Siglo (XIXXX) (Mxico: Universidad Nacional Autnoma de Mexico, 2001), pp. 161193;

and Patrick Frank, Posadas Broadsheets: Mexican Popular Imagery, 18901910

(Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998), pp. 129165.

(13.) Juan Pablo Dabove and Susan Hallstead, Pasiones fatales: consume, bandidaje y

gnero en El Zarco, A Contracorriente, 7.1 (Fall 2009): 174. The article also deals

centrally with unproductive female consumption in El Zarco.

(14.) Steven B. Bunker and Vctor M. Macas-Gonzlez, Consumption and Material

Culture from Pre-Contact through the Porfiriato, in William H. Beezley, ed., A

Companion to Mexican History and Culture (London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011), p. 72.

(15.) Pablo Piccato, The Tyranny of Opinion: Honor in the Construction of the Mexican

Public Sphere (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), p. 83.

(16.) Pablo Piccato, The Tyranny of Opinion: Honor in the Construction of the Mexican

Public Sphere (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), pp. 88 & 95.

(17.) For useful overviews of the history of the word macho, see Carlos Monsivis,

Escenas de pudor y liviandad (Mexico City: Editorial Grijalbo, 1981), pp. 103117; and

Matthew C. Gutmann, The Meanings of Macho: Being a Man in Mexico City (Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1996), pp. 221232.

(18.) Consecuencias, El Diablito Rojo, April 2, 1900. The original poem has an internal

rhyme scheme that gives it a charm lacking in translation. See Robert M. Buffington,

Towards a Modern Sacrificial Economy: Violence Against Women and Male Subjectivity

in Turn-of-the-Century Mexico City, in Vctor M. Macas-Gonzlez and Anne Rubenstein,

eds. Masculinity and Sexuality in Modern Mexico (Albuquerque: University of New

Mexico Press, 2012), p. 166.

(19.) Ego, Consejos, El Diablito Rojo, March 4, 1901. See Buffington, Towards a

Modern Sacrificial Economy, p. 179.

(20.) See especially Jennifer S. Hirsch, A Courtship after Marriage: Sexuality and Love in

Mexican Transnational Families (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003).

Page 27 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).

date: 19 February 2017

Men and Modernity in Porfirian Mexico

(21.) Cited in Roberto Miranda Guerrero, Gnero, masculinidad, familia y cultura escrita

en Guadalajara,18001940, in Roberto Miranda Guerrero and Luca Mantilla Gutirrez,

eds. Hombres y masculinidades en Guadalajara (Guadalajara: Universidad de

Guadalajara, 2006), pp. 213214.

(22.) See William E. French, A Peaceful and Working People: Manners, Morals, and Class

Formation in Northern Mexico (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996), pp.

6385.

(23.) Cited in William E. French, The Heart in the Glass Jar: Love Letters, Bodies, and the

Law in Mexico (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2015), p. 182.

(24.) Dr. de Belina, Influencia de altura sobre la vida y la salud del habitante de

Anahuac, Boletn de la Sociedad Mexicana de Geografa y Estadstica 4.45 (1878), p.

303. Cited in Robert M. Buffington, Criminal and Citizen in Modern Mexico (Lincoln:

University of Nebraska Press, 2000), p. 146.

(25.) Justo Sierra, The Political Evolution of the Mexican People, trans. Charles Ramsdell

(Austin: University of Texas, 1976), p. 368.

(26.) See for example, the Posada illustrations in Rafael Barajas Durn, Posada mita o

mitote (Mxico: Fondo de Cultura Econmica, 2009), pp. 216 & 242244.

(27.) Robert M. Buffington, Homophobia and the Mexican Working Class, 19001910, in

Robert McKee Irwin, Edward J. McCaughan, and Michelle Roco Nasser, eds. The Famous

41: Sexuality and Social Control in Mexico, c. 1901 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan,

2003), p. 202.

(28.) See especially Vctor M. Macas-Gonzlez, The Bathhouse and Male Homosexuality

in Porfirian Mexico, in Vctor M. Macas-Gonzlez and Anne Rubenstein, eds. Masculinity

and Sexuality in Modern Mexico (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press,

2012), pp. 2552.

(29.) The Nefarious Ball, El Pas, November 22, 1901, in Robert McKee Irwin, Edward J.

McCaughan, and Michelle Roco Nasser, eds. The Famous 41: Sexuality and Social

Control in Mexico, c. 1901 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), p. 23.

(30.) Carlos Monsivis, The 41 and the Gran Redada, in Robert McKee Irwin, Edward J.

McCaughan, and Michelle Roco Nasser, eds. The Famous 41: Sexuality and Social

Control in Mexico, c. 1901 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), pp. 139167.

(31.) Mexico: Librera de la Vda. de Ch. Bouret, 1920.

Page 28 of 29

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY

(latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only;

commercial use is strictly prohibited. Please see applicable Privacy Policy and Legal Notice (for details see Privacy Policy).