The Recognition of Somaliland A Brief History PDF

Diunggah oleh

Mohamed AliJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

The Recognition of Somaliland A Brief History PDF

Diunggah oleh

Mohamed AliHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

The recognition of Somaliland

A brief history

Presidency, Hargeisa, Somaliland pogc@somalilandgov.com 1

After conclusion of treaties between Great Britain and the various Somaliland clans in the early

1880s, the Somaliland Protectorate was proclaimed in 1887. The international boundaries of the

Protectorate were delineated by treaties with France (Djibouti) to the west in 1888, Ethiopia to the

south in 1887 and Italy (Somalia) to the east in 1894. 1

On 26 June 1960, Somaliland became an independent, sovereign state, known as the State

of Somaliland. As in all the countries which were decolonised in 1960, the State of Somaliland

immediately received congratulatory telegrams 2 from 35 countries, including all five permanent

members of the UN Security Council welcoming its sovereignty. 3 This was the practice in which rec-

ognition4 was extended to new decolonised states. As an independent state, the State of Somalil-

and entered into various treaties with the UK.

Five days after independence, on 1 July 1960, Somaliland chose to unite with Somalia with the

aim of creating a Greater Somalia bringing together all the people of ethnic Somali origin in

five countries in the Horn of Africa including Northern Kenya, Italian Somalia, French Somaliland

and Eastern Ethiopia. 5

The agreed formalities of a treaty of union to be entered into by both Somaliland and Soma-

lia were not completed properly. The version passed as a Law by the legislature of the State

of Somaliland was not passed by the Somalia Legislature. A different single Act of Union was

later passed by the National Assembly in 1961. A legal expert commented that the legal validity of the

legislative instruments establishing the union were questionable. 6

The people of Somaliland had no say in the making of the constitution of the new Somali Re-

public. In the majority of the districts in Somaliland the referendum on the constitution held on 20

June 1961 was largely boycotted 7 and, in sharp contrast to the Somalia regions, in the vast majori-

ty of Somaliland regions, the constitution was rejected.

1. The Anglo-French Treaty of 1888; the Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1897 and the Anglo-Italian Protocol of 1894.

2. These included, for example telegrams from US Secretary of State Herter, which were addressed to their excellencies, Council of

Ministers, Hargeisa. A congratulatory message to a new state for obtaining sovereignty is tantamount to recognition.

3. There were three treaties between Great Britain and the State of Somaliland, which were deposited with the UN in line with the

practice of international treaties. The treaties were also referred to in the Somaliland/Somalia Act of Union of 1961.

4. A congratulatory message to a new state for obtaining sovereignty is tantamount to recognition (Yamali N What is meant by state

recognition International Law? available at http://www.justice.gov.tr/e-journal/pdf/LW7081.pdf)

5. Cotran E (1963). Legal Problems Arising Out of the Formation of the Somali Republic, International and Comparative Law

Quarterly, 12, pp 1010-1026

6. It was estimated that fewer than 17% of those eligible to vote took part - J. Drysdale, Somaliland: The Anatomy of Secession,

(London: Haan Associates, 1991)

7. United States Department of State Dispatch, 1990 Human Rights Report: Somalia, (1991); Africa Watch Committee, Somalia: A

government at war with its own people, (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1990), pp. 126-131

Presidency, Hargeisa, Somaliland pogc@somalilandgov.com 2

The early years of the union saw the steady political and economic isolation of former Somalil-

and and its main towns, with political and military positions being awarded disproportionately to

southern Somalis. The 1961 an attempted coup by a group of highly qualified Somaliland military

officers was an indication of the disenchantment with the union that Somaliland had entered into.

After assuming power in a military coup in October 1969, Mohamed Siad Barre led a brutal

military dictatorship, marked by widespread human right abuses. The growing discontent with

and oppression by Barres leadership led to the formation of an opposition group, the Somali

National Movement (SNM) in the North (Somaliland) in 1981.

In response to growing opposition, the Barre regime waged a targeted war on the north

(Somaliland), killing an estimated 50,000 civilians and displacing an estimated 500,000 people. 8

Northern towns such as Hargeisa and Burao were shelled and bombed. Government forces also laid

over a million unmarked land mines in the north. 9 Human Rights Watch described the Barre regime

as a government at war with its people. 10

With the formation of armed opposition groups in Mogadishu and its surrounding regions in

the late 1980s, the Barre regime finally collapsed and on 27 January 1991, Barre fled Mogadi-

shu. Groups in Mogadishu initially attempted to form their own governments without any consultation

and the country sank into a state of anarchy.

On 18 May 1991, the various Somaliland communities met at a Grand Conference and decid-

ed to re-assert Somalilands sovereignty and independence. Leaders of the SNM and elders of

northern (Somaliland) clans met at the Grand Conference of the Northern Peoples in Burao. The

Union with Somalia was revoked and the territory of the State of Somaliland (based on the borders of

the former British Somaliland Protectorate) became the Republic of Somaliland.

Somalilands withdrawal from the union and re-assertion of its sovereignty did not breach any

international law and at the time the UN Security Council saw no reason to interfere. 11 After

a long period of persecution of the majority of the Somaliland population the people of Somaliland

withdrew from the union their representatives had voluntarily entered in 1960.

Using indigenous peace-making procedures, the various Somaliland communities held a con-

siderable number of local meetings and national conferences to re-establish the peace be-

tween the different communities and lay the foundations for local security and

8. United States Department of State Dispatch, 1990 Human Rights Report: Somalia, (1991); Africa Watch Committee, Somalia: A

government at war with its own people, (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1990), pp. 126-131

9. Africa Watch Committee, Somalia: A government at war with its own people, (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1990), pp. 126-131

10. Ibid.

11. ndeed, the International Court of Justice decided in the Kosovo case that unilateral declarations of secession are not by themselves

unlawful under international law.

Presidency, Hargeisa, Somaliland pogc@somalilandgov.com 3

governance, in tandem with state building and national governance. 12 It is the understanding

arrived at in these meetings that have enabled Somaliland to establish peace and national gover-

nance. 13

The development of the Somaliland constitution started with National Charter in 1993, fol-

lowed by an Interim Constitution in 1997 and culminated in the adoption of a final constitu-

tion in 2001. On 31 May 2001, 97.9% of Somalilands population voted in favour of the new con-

stitution in a referendum endorsed by international observers as free and fair. 14

Somalilands constitution establishes the separation of power between the three arms of

government, balances representative democracy with traditional governance institutions, ensures

the existence of active opposition political parties, a free and pluralistic media and fundamental

human rights and freedoms.

Nation-wide local elections took place in 2002 and in 2012. Presidential elections took place

in 2003 and 2010, and parliamentary elections in 2005. International and local observers have

stated that all these elections were free and on the whole fair. In both cases the losing side accept-

ed the outcome gracefully.

Despite the lack of international recognition since 1991, in large part due to the international

communitys preoccupation with establishing peace in Somalia, Somalilanders are confident

that they will achieve their rightful place within the community of nations. Somaliland has not

been a party to the recent changes in Somalia and has agreed to enter into discussions with the

new Somalia government with a view to reaching amicable agreements on future co-operation be-

tween the two independent states and the settlement of all outstanding issues of joint concern.

Further reading:

1. Ahmed H Nur, A short briefing paper: Does Somaliland have a legal ground for seeking international recognition? (2011)

2. Jama Musse Jama (ed.), Somaliland: the way forward, (Pisa: Ponte Invisibile, 2011), including Recognising Somaliland:

Political, Legal and Historical Perspectives, Mohamed A Omar

3. Mark Bradbury, Becoming Somaliland, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008)

4. The Brenthurst Foundation, African Game Changer? The Consequences of Somalilands International (Non) Recognition

Discussion Paper 2011/05, (Johannesburg: The Brenthurst Foundation, 2011)

5. Peter Roethke, The Right to Secede Under International Law: The Case for Somaliland, The Journal of International

Service, (Fall 2011), pp. 35-47

6. Matt Bryden, Rebuilding Somaliland, Issues and Possibilities, (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2003)

12. In its final overall study of the peace initiatives in Somaliland, the Academy of Peace identified 39 peace conferences and meetings

between 1991 and 1997 Peace in Somalilnd: An indigenous Approach to State Building, APD, Interpeace, 2008. page 10. Available at:

http://www.interpeace.org/index.php/publications/cat_view/8-publications/12-somali-region?start=5

13. In contrast to Somalia where until 2012, numerous peace making conferences were held abroad with funding from the international

community, Somalilands peacemaking conferences, which were concluded by 1997, were all held in the country without the involvement

of the international community.

14. M.Bradbury, A.Abokor, H.Yusuf, Somaliland: Choosing Politics over Violence (Review of African Political Economy, Vol. 30, No. 97,

September 2003)

Presidency, Hargeisa, Somaliland pogc@somalilandgov.com 4

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Recognition of Somaliland A Brief HistoryDokumen4 halamanRecognition of Somaliland A Brief HistorykermitBelum ada peringkat

- Is It Unilateral SecessionDokumen3 halamanIs It Unilateral SecessionGuiled Yusuf IdaanBelum ada peringkat

- The Recognition of Somaliland: The Legal CaseDokumen3 halamanThe Recognition of Somaliland: The Legal CaseSomaliland Society BristolBelum ada peringkat

- AHNUR Regnition Briefing 042011Dokumen8 halamanAHNUR Regnition Briefing 042011Mohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- Unit Eight (Somali Independence and Reunion)Dokumen15 halamanUnit Eight (Somali Independence and Reunion)Ria fBelum ada peringkat

- Twisting Talks Between Somaliland and So PDFDokumen11 halamanTwisting Talks Between Somaliland and So PDFMo HirsiBelum ada peringkat

- Este EsDokumen24 halamanEste EsIsabellaBelum ada peringkat

- History Form Four (Summary)Dokumen35 halamanHistory Form Four (Summary)Mohamed AbdiBelum ada peringkat

- Somaliland Legal SystemDokumen10 halamanSomaliland Legal SystemGaryaqaan Muuse YuusufBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 1 History SummaryDokumen5 halamanChapter 1 History SummaryMuncim Ina MaxamuudBelum ada peringkat

- The Case For The Independent Statehood of SomalilandDokumen30 halamanThe Case For The Independent Statehood of SomalilandGaryaqaan Muuse YuusufBelum ada peringkat

- The Deep Rooted Conflict Between The Rep PDFDokumen10 halamanThe Deep Rooted Conflict Between The Rep PDFMo HirsiBelum ada peringkat

- Somaliland Visit Report FinalDokumen28 halamanSomaliland Visit Report FinalmubarikabdiBelum ada peringkat

- State Fragility Somaliland and SomaliaDokumen28 halamanState Fragility Somaliland and SomaliaANA100% (1)

- Scars and Revelations: My Journey from Sudan’s Brutality to Poland, Love and FamilyDari EverandScars and Revelations: My Journey from Sudan’s Brutality to Poland, Love and FamilyBelum ada peringkat

- Constitutional Developments in Nigeria - 101152Dokumen40 halamanConstitutional Developments in Nigeria - 101152Ibidun TobiBelum ada peringkat

- Introductions: History of SomalilandDokumen3 halamanIntroductions: History of SomalilandAmiin Hassan SheekhBelum ada peringkat

- 4 Pages of The Collapse of The Somali StateDokumen4 halaman4 Pages of The Collapse of The Somali Stateabadir.abdiBelum ada peringkat

- Somaliland 30th Anniversary 2021 PDF NewDokumen10 halamanSomaliland 30th Anniversary 2021 PDF NewOmar AwaleBelum ada peringkat

- A Nation in Search of A State (1885 - 1992)Dokumen42 halamanA Nation in Search of A State (1885 - 1992)Ibrahim Abdi GeeleBelum ada peringkat

- Pan Africanism and Pan Somalism By: I.M. LewisDokumen16 halamanPan Africanism and Pan Somalism By: I.M. LewisAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-Misri100% (1)

- Roles and Duties-Nam N Commonwealth-IR GROUPDokumen22 halamanRoles and Duties-Nam N Commonwealth-IR GROUPNur Sazela FahrudinBelum ada peringkat

- Internally Displaced Persons in SomaliaDokumen18 halamanInternally Displaced Persons in Somaliaapi-223092373Belum ada peringkat

- The Creation of South SudanDokumen30 halamanThe Creation of South SudanAnyak2014Belum ada peringkat

- A-Abdi, Somali Minorities Report, p64Dokumen64 halamanA-Abdi, Somali Minorities Report, p64Yooxanaa AliBelum ada peringkat

- Social Studies Quiz QuestionsDokumen5 halamanSocial Studies Quiz QuestionsMathews KalyepeBelum ada peringkat

- A Passage To Africa History and ContextDokumen11 halamanA Passage To Africa History and Contextalr25Belum ada peringkat

- Perspectives of The State Collapse in SomaliaDokumen31 halamanPerspectives of The State Collapse in SomaliaDr. Abdurahman M. Abdullahi ( baadiyow)100% (1)

- Proposition For Memorial Drafting MNLUADokumen7 halamanProposition For Memorial Drafting MNLUARICHA KUMARI 20213088Belum ada peringkat

- Somaliland Foreign Policy Analysis in PerspectiveDokumen14 halamanSomaliland Foreign Policy Analysis in PerspectiveAbdiqani Muse EngsaabirBelum ada peringkat

- Commonwealth of Nations: OriginsDokumen2 halamanCommonwealth of Nations: OriginsAndaVacarBelum ada peringkat

- Conception of Transitional Justice in SomaliaDokumen32 halamanConception of Transitional Justice in SomaliaDr. Abdurahman M. Abdullahi ( baadiyow)Belum ada peringkat

- Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na'im - The Islamic Law of Apostasy and Its Modern Applicability - A Case From The SudanDokumen28 halamanAbdullahi Ahmed An-Na'im - The Islamic Law of Apostasy and Its Modern Applicability - A Case From The SudanzostriBelum ada peringkat

- Sudan’s People and the Country of ‘South Sudan’ from Civil War to Independence, 1955–2011Dari EverandSudan’s People and the Country of ‘South Sudan’ from Civil War to Independence, 1955–2011Belum ada peringkat

- State-Building in The Horn of Africa: The Pan-Somali Project and Cold War Politics During The 1960sDokumen10 halamanState-Building in The Horn of Africa: The Pan-Somali Project and Cold War Politics During The 1960salexBelum ada peringkat

- The CommonwealthDokumen8 halamanThe Commonwealthmisslala1Belum ada peringkat

- Massa Day Done: The Republican Constitution of Trinidad and Tobago: Origins and IssuesDari EverandMassa Day Done: The Republican Constitution of Trinidad and Tobago: Origins and IssuesBelum ada peringkat

- Axdiga Qaranka 2Dokumen11 halamanAxdiga Qaranka 2dgacanlibaaxBelum ada peringkat

- Commonwealth PDFDokumen21 halamanCommonwealth PDFDiego CoradoBelum ada peringkat

- PLSC 420 Term Paper FinalDokumen21 halamanPLSC 420 Term Paper Finalapi-456889674Belum ada peringkat

- ??????? ???? 4 ??????? ??????????? ?? ??????????Dokumen85 halaman??????? ???? 4 ??????? ??????????? ?? ??????????MAslah Kader BoonBelum ada peringkat

- PIL by SyedbilalhdrzvDokumen23 halamanPIL by SyedbilalhdrzvShivam Mani TripathiBelum ada peringkat

- Making of The South African ConstitutionDokumen5 halamanMaking of The South African ConstitutionAchilles HussainBelum ada peringkat

- Somalia: An Overview of The Historical and Current SituationDokumen51 halamanSomalia: An Overview of The Historical and Current SituationIQ Option TricksBelum ada peringkat

- Apostasy HK 2Dokumen28 halamanApostasy HK 2Samsul Hidayat100% (1)

- CLASS IX Politics Chapter 3 Constitutional DesignDokumen7 halamanCLASS IX Politics Chapter 3 Constitutional DesignAksa Merlin ThomasBelum ada peringkat

- MalawiDokumen142 halamanMalawiJohn L KankhuniBelum ada peringkat

- HSC The Situation in RhodesiaDokumen14 halamanHSC The Situation in RhodesiaPanayiotis VoyiatzisBelum ada peringkat

- Opening Speech by Abdurahman AbdullahiDokumen7 halamanOpening Speech by Abdurahman AbdullahiDr. Abdurahman M. Abdullahi ( baadiyow)Belum ada peringkat

- CONSTITUTIONAL DESIGN - Class Notes - SprintDokumen73 halamanCONSTITUTIONAL DESIGN - Class Notes - SprintArav AroraBelum ada peringkat

- SomaliaDokumen19 halamanSomaliaEdward Essau Fyitta100% (1)

- Do It as Wilson Says: The Wilsonian Approach Concerning US Foreign PolicyDari EverandDo It as Wilson Says: The Wilsonian Approach Concerning US Foreign PolicyBelum ada peringkat

- Lucknow PactDokumen38 halamanLucknow PactAamir MehmoodBelum ada peringkat

- Somaliland African Best Kept SecretDokumen6 halamanSomaliland African Best Kept SecretshimbirBelum ada peringkat

- Africa TelecomDokumen26 halamanAfrica TelecomMohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- Somali Lake AsalDokumen27 halamanSomali Lake AsalMohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- KenyaDokumen16 halamanKenyaMohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- Budget Brief 2020 Final - SomalilandDokumen16 halamanBudget Brief 2020 Final - SomalilandMohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- SheekoyinDokumen2 halamanSheekoyinMohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- Hadimadii Gumeysiga & Halgankii UmmaddaDokumen45 halamanHadimadii Gumeysiga & Halgankii UmmaddaMohamed Ali100% (3)

- Ela Glossary SomaliDokumen11 halamanEla Glossary SomaliMohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- 2018IdeaCollection Examples SomalilandDokumen2 halaman2018IdeaCollection Examples SomalilandMohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- Gabay Hayir A Somali Mock Said SamatarDokumen30 halamanGabay Hayir A Somali Mock Said SamatarMohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- 16 Prolapse SomaliDokumen5 halaman16 Prolapse SomaliMohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- 2015 1 5 Nabad AhDokumen72 halaman2015 1 5 Nabad AhMohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- Tusmooyinka Ka Hortagidda:: Waad Ka Hortagi Kartaa La Kulanka Kaarboonka Hal Ogsijiinlaha (Carbon Monoxide)Dokumen1 halamanTusmooyinka Ka Hortagidda:: Waad Ka Hortagi Kartaa La Kulanka Kaarboonka Hal Ogsijiinlaha (Carbon Monoxide)Mohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- President 2013 Speech Somali1Dokumen20 halamanPresident 2013 Speech Somali1Mohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- Gupea 2077 30596 1 PDFDokumen240 halamanGupea 2077 30596 1 PDFMohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- 21 SomaliVersionDokumen139 halaman21 SomaliVersionMohamed Ali100% (1)

- Somaliland Oo Ku Celisay Meeshii Ay Ka Taagneyd SomaliaDokumen1 halamanSomaliland Oo Ku Celisay Meeshii Ay Ka Taagneyd SomaliaMohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- Somaliland Citizenship Law 22-02-2002Dokumen16 halamanSomaliland Citizenship Law 22-02-2002Mohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- Somalia - Gundel - The Role of Traditional StructuresDokumen85 halamanSomalia - Gundel - The Role of Traditional StructuresAleksander PruittBelum ada peringkat

- Somaliland Vision 2030Dokumen20 halamanSomaliland Vision 2030Mohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- SalalDokumen1 halamanSalalMohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- Somaliland Food and Water Security StrategyDokumen58 halamanSomaliland Food and Water Security StrategyMohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- ProgramBooklet SIFHargeisa2017 FINALDokumen38 halamanProgramBooklet SIFHargeisa2017 FINALMohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- ( (Fullname) ) ( (Jobtitle) ) ( (Company) ) ( (Fullname) ) ( (Jobtitle) ) ( (Company) )Dokumen1 halaman( (Fullname) ) ( (Jobtitle) ) ( (Company) ) ( (Fullname) ) ( (Jobtitle) ) ( (Company) )Mohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- P200 PDFDokumen20 halamanP200 PDFMohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- JPLG Human Resources - SomalilandDokumen4 halamanJPLG Human Resources - SomalilandMohamed Ali100% (1)

- Somaliland Food and Water Security StrategyDokumen58 halamanSomaliland Food and Water Security StrategyMohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- Saxil Region Report Constituency ConsultationDokumen8 halamanSaxil Region Report Constituency ConsultationMohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- The Publics RecordsDokumen10 halamanThe Publics RecordsemojiBelum ada peringkat

- Jim Crow PassiveDokumen5 halamanJim Crow PassiveAngel Angeleri-priftis.Belum ada peringkat

- Inter-State River Water Disputes in India Is It Time For A New Mechanism Rather Than TribunalsDokumen6 halamanInter-State River Water Disputes in India Is It Time For A New Mechanism Rather Than TribunalsNarendra GBelum ada peringkat

- The Battle of BuxarDokumen2 halamanThe Battle of Buxarhajrah978Belum ada peringkat

- Henry Sy, A Hero of Philippine CapitalismDokumen1 halamanHenry Sy, A Hero of Philippine CapitalismRea ManalangBelum ada peringkat

- Rwandan Genocide EssayDokumen5 halamanRwandan Genocide Essayapi-318662800Belum ada peringkat

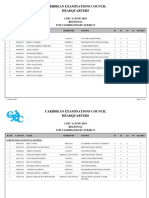

- Regionalmeritlistbysubject2019 Csec 191031164645 PDFDokumen39 halamanRegionalmeritlistbysubject2019 Csec 191031164645 PDFBradlee Singh100% (1)

- GNS 111/103 Prof. C.A Onifade and S.N AtataDokumen60 halamanGNS 111/103 Prof. C.A Onifade and S.N AtataImokhai AbdullahBelum ada peringkat

- 1.b. Conflict of LawsDokumen17 halaman1.b. Conflict of LawskdescallarBelum ada peringkat

- Defining Relative Clause Non-Defining Relative Clause: ReminderDokumen1 halamanDefining Relative Clause Non-Defining Relative Clause: ReminderFouad BoudraaBelum ada peringkat

- All Articles Listed Below by Week Are Available at UCSD Electronic ReservesDokumen4 halamanAll Articles Listed Below by Week Are Available at UCSD Electronic ReservesvictorvienBelum ada peringkat

- Dokumen - Pub The Impossibility of Motherhood Feminism Individualism and The Problem of Mothering 0415910234 9780415910231Dokumen296 halamanDokumen - Pub The Impossibility of Motherhood Feminism Individualism and The Problem of Mothering 0415910234 9780415910231rebecahurtadoacostaBelum ada peringkat

- Slavoj Zizek - A Permanent State of EmergencyDokumen5 halamanSlavoj Zizek - A Permanent State of EmergencyknalltueteBelum ada peringkat

- Law Thesis MaltaDokumen4 halamanLaw Thesis MaltaEssayHelperWashington100% (2)

- The Geopolitical Economy of Resource WarsDokumen23 halamanThe Geopolitical Economy of Resource WarsLucivânia Nascimento dos Santos FuserBelum ada peringkat

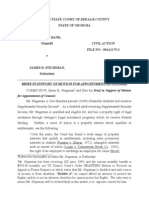

- Brief in Support of Motion To Appoint CounselDokumen11 halamanBrief in Support of Motion To Appoint CounselJanet and James100% (1)

- TNPSC Group 4 Govt Notes - Indian National Movement - EnglishDokumen68 halamanTNPSC Group 4 Govt Notes - Indian National Movement - Englishdeebanmegam2Belum ada peringkat

- Seminario de Investigación 2991-2016n01Dokumen4 halamanSeminario de Investigación 2991-2016n01ramonlamedaBelum ada peringkat

- Wickham. The Other Transition. From The Ancient World To FeudalismDokumen34 halamanWickham. The Other Transition. From The Ancient World To FeudalismMariano SchlezBelum ada peringkat

- Yamaguchi Yoshiko and Fujiwara Sakuya - Fragrant Orchid - The Story of My Early LifeDokumen418 halamanYamaguchi Yoshiko and Fujiwara Sakuya - Fragrant Orchid - The Story of My Early LifeJp Vieyra Rdz100% (1)

- Glossary SociologyDokumen10 halamanGlossary SociologydigitalfaniBelum ada peringkat

- Law and Justice in Globalized World Manish Confirm PDFDokumen33 halamanLaw and Justice in Globalized World Manish Confirm PDFKamlesh RojBelum ada peringkat

- Global Governance: Rhea Mae Amit & Pamela PenaredondaDokumen28 halamanGlobal Governance: Rhea Mae Amit & Pamela PenaredondaRhea Mae AmitBelum ada peringkat

- Cambodia Food Safety FrameworkDokumen3 halamanCambodia Food Safety FrameworkRupali Pratap SinghBelum ada peringkat

- BGR ApplicationFormDokumen4 halamanBGR ApplicationFormRajaSekarBelum ada peringkat

- Nigeria Stability and Reconciliation Programme Volume 1Dokumen99 halamanNigeria Stability and Reconciliation Programme Volume 1Muhammad NaseerBelum ada peringkat

- Part of Maria Bartiromo's DepositionDokumen4 halamanPart of Maria Bartiromo's DepositionMedia Matters for AmericaBelum ada peringkat

- Paul DurcanDokumen15 halamanPaul Durcanapi-285498423100% (3)

- Davao Norte Police Provincial Office: Original SignedDokumen4 halamanDavao Norte Police Provincial Office: Original SignedCarol JacintoBelum ada peringkat

- (2018) Alterity PDFDokumen2 halaman(2018) Alterity PDFBruno BartelBelum ada peringkat