Transition of Acute To Hronic

Diunggah oleh

Amira RanicaJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Transition of Acute To Hronic

Diunggah oleh

Amira RanicaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Refresher Course: The transition from acute to chronic pain

The transition from acute to chronic pain

Lamacraft G

Associate Professor of Anaesthesia and Head of Pain Control Unit, Universitas Hospital, Bloemfontein

Correspondence to: Prof Gillian Lamacraft, e-mail: lamacraftg@ufs.ac.za

Introduction

Table I: Procedure-specific incidence of chronic post-surgical pain2

Why some patients develop chronic pain after an acutely painful

event remains an enigma. For example, over 90% of the population Type of surgery Incidence of chronic pain (%)

will experience acute back pain at some time in their lives. In most Amputation 30 - 85

cases this resolves but, in a few, it does not, even though these

Thoracotomy 5 - 67

patinets have radiologic pathology similar to those in whom the pain

does improve. Mastectomy 11 - 57

Inguinal hernia repair 0 - 63

Similarly, there are few people who escape the hands of the

surgeon. What is becoming increasingly apparent is that those who Sternotomy 28 - 56

do experience the sharp end of the scalpel frequently experience Cholecystectomy 3 - 56

persistent pain as a result of the damage caused by this instrument.

The reasons for this chronic post-surgical pain are discussed in this Knee arthroplasty 19 - 43

presentation, as are possible preventative strategies. Breast augmentation 13 - 38

Vasectomy 0 - 37

Definition of chronic post-surgical pain (CPSP)

Radical prostatectomy 35

From Macrae and Davies:1 Gynaecological laparotomy 32

Iliac crest bone harvest site 30

Pain developed after a surgical procedure;

Pain is of at least 2 months duration; Hip arthroplasty 28

Other causes for the pain should have been excluded (e.g. Saphenectomy 27

continuing malignancy or chronic infection);

Hysterectomy 25

The possibility that the pain is continuing from a pre-existing

problem must be explored and exclusion attempted. Craniotomy 6 - 23

Rectal amputation 12 - 18

Incidence

Caesarean section 12

There are frequently wide variations in the incidence of chronic Dental surgery 5 - 13

pain after specific operations. This is because studies that

have been performed, which directly investigate the incidence

operative nerve damage, resulting in neuropathic pain, and that it is

of chronic pain after an operation, find a far higher incidence

modified by psychosocial factors which may have been pre-existing

than those studies in which chronic pain incidence was only

or developed post-operatively as a consequence of the chronic pain

part of the study. Despite this, it is often startling to see how

experience.

high the incidence of chronic post-surgical pain is, and there

are suggestions that patients should be informed of this before

Following surgery, neuropathic pain can be caused by damage

consenting to surgery (Table I).

to peripheral nerves or central nervous system (CNS) sensory

transmission. Inflammatory pain due to persistence of the

Aetiology inflammatory response or chronic infection may also be a factor. It

is important to differentiate neuropathic from non-neuropathic pain,

Pain is subjective, but may be caused by various factors. Exactly what in order to effectively design strategies to prevent and to treat these

causes CPSP remains unclear but it appears that it is related to both entities.

S Afr J Anaesthesiol Analg 108 2010;16(1)

Refresher Course: The transition from acute to chronic pain

Neuropathic pain is diagnosed clinically, and there are no specific be because younger patients tend to have larger and more

diagnostic tests for this condition. Rasmussen et al have proposed aggressive tumours.10 Conversely, children seem to experience

the following criteria for the diagnosis of neuropathic pain:3 less CPSP than adults.11 This phenomenon has been attributed

to immaturity of the childs nervous system and/or enhanced

Pain in a neuroanatomically defined area, i.e, corresponding to neuronal plasticity.12

a peripheral or central innervation territory;

History of relevant disease or lesion in the nervous system, Gender: Women have a higher incidence of CPSP.13

which is temporally related to development of pain;

Partial or complete sensory loss in all or part of the painful area; Genetic susceptibility: There is a hereditary component to both

Confirmation of a lesion or disease by a specific test, e.g. the generation and experience of pain. Genetic polymorphisms

surgical evidence, imaging, clinical neurophysiology, biopsy. of catecholamine-O-methyltransferase have been linked to an

increased risk of chronic pain.14

Whilst studies based on self-reporting of symptoms by patients may

not identify neuropathic pain, other studies which have used more Pre-operative pain: A number of studies have linked the duration

refined investigative tools such as sensory threshold changes are and intensity of pre-operative pain to CPSP. For mastectomy

more sensitive and more likely to elucidate neuropathic pain.4,5 and amputation, experiencing pain for more than a month

before surgery is predictive of CPSP.15 Even experiencing pre-

The link between neuropathic pain and CPSP is complicated. Many operative pain that is not related to the surgical site increases

patients in whom there are clear signs of peri-operative nerve damage the risk of CPSP.16

(e.g. a numb area) do not experience CPSP.6 When comparing cases

where a sensory nerve was deliberately sacrificed during surgery Psychological problems; pre-operative anxiety is associated

with cases where efforts were made to preserve it, the incidence of with acute postoperative pain, as is catastrophising.17,18 It

CPSP appears to be similar.7,8 remains debatable whether anxiety and depression predispose

to CPSP, or are a result of the pain.19 However, as there is a

The mechanisms by which CPSP results from surgery have been link between acute postoperative pain and CPSP, it is likely that

suggested by Kehlet et al to be the following:9 there is a relationship between pre-operative anxiety and/or

depression and CPSP.

Surgical nerve injury results in the production of local and

systemic inflammatory mediators by denervated Schwann cells A multitude of other factors may play a role in CPSP. For example,

and infiltrating macrophages. These potentiate the transmission whether cancer patients have radiotherapy or chemotherapy

of pain by lowering the excitability threshold. may be relevant. Social issues such as work, physical activity

As nerves heal, the cut ends may develop into neuromata. and social environment also affect a persons response to pain.

These may exhibit ectopic spontaneous excitability which, in

sensory neurones, will result in pain.

Prevention of CPSP

Intense noxious peripheral stimuli (and inflammatory mediators

released from damaged tissue) act centrally. Activation of

It is become increasingly apparent that, in order to prevent CPSP,

intracellular kinases leads to alterations in pre-existing

one must prohibit noxious inputs from reaching the CNS for the

proteins in dorsal horn neurons. After several hours, altered

entire peri-operative period. Failing that, one has to prevent the CNS

gene transcription can be seen, which enhances the action

changes that result from painful stimuli starting. If, at any time during

of excitatory transmitters and reduces the action of inhibitory

the peri-operative period, there is an episode of breakthrough pain,

transmitters.

then irreversible CNS changes may be triggered and CPSP may

Death by apoptosis results in loss of inhibitory interneuron. In

result.

addition, microglial activation amplifies sensory flow.

Brainstem and cortical changes occur. Marked changes in

This explains why pre-emptive regional anaesthesia does not

functional topography occur in the cortex, and cortical grey

consistently reduce CPSP, whereas preventative regional anaesthesia

matter may be lost. Alterations in the connections between

may do. Here the difference is that, in the former, the block is

the spinal cord and brain result in an increase in descending

given before surgical incision but not continued whereas, in the

facilitatory influences and a reduction in inhibitory stimuli.

latter, the block is given before incision but continued well into the

postoperative period.

Risk factors for CPSP

Pre-emptive antineuropathic pain medication similarly shows

Surgery: Both major and minor procedures are associated with no effect on CPSP, whereas preventative antineuropathic pain

CPSP (see Table I). The incidence and severity of CPSP has not medication may be beneficial.20,21

been shown to be related to the extent of the surgery.

Multimodal analgesic techniques are being increasingly used to

Age: Older patients tend to have a lower incidence of CPSP provide maximal analgesia with minimal side-effects with the aim

than younger adults. For breast cancer surgery, this may of reducing CPSP.22 Whilst, in theory, these can be highly effective,

S Afr J Anaesthesiol Analg 109 2010;16(1)

Refresher Course: The transition from acute to chronic pain

more often than not the problem remains of ensuring that the 18. Pavlin DJ, Sullivan MJ, Freund PR, Roesen K. Catastrophizing: a risk factor for postsurgical pain.

Clin J Pain 2005;21:83-90.

patient actually receives the analgesic medication prescribed

19. Jess P, Jess T, Beck H,

and at the correct time. All too frequently the patent only receives

analgesia when pain has returned. Nursing staff must be educated 20. Clarke H, Pereira S, Kennedy D, et al. Adding Gabapentin to a multimodal regimen does not reduce

acute pain, opioid consumption or chronic pain after total hip arthroplasty. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand

to administer analgesia regularly in order to prevent pain. Surgeons

2009;53:1073-83.

need to understand the importance of maintaining epidural infusions

21. Arsenault A, Sawynok J. Perisurgical amitryptiline produces a preventive effect on afferent

well into the postoperative period and not to discontinue them hypersensitivity following spared nerve injury. Pain 2009;146:308-14.

prematurely.

22. Reuben SS, Buvanendran A. Preventing the development of chronic pain after orthopaedic surgery

with preventive multimodal analgesic techniques. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89:1343-58.

Conclusion

Over the last ten years, there has been a substantial increase in the

understanding of the problem of CPSP amongst anaesthesiologists.

This information needs to be more widely disseminated to other

healthcare professionals. Patients should be given information

regarding the likelihood of CPSP so that they can make more informed

decisions regarding whether to undergo certain operations and, if

they do proceed with surgery and develop CPSP, understand why

it has occurred and not attribute undeserved blame to the surgeon.

The patient would also then be more likely to have his or her pain

acknowledged and receive appropriate treatment.

References

1. Macrae WA, Davies HTO. Chronic postsurgical pain. In: Crombie IK, editor. Epidemiology of pain.

Seattle: IASP Press; 1999. p. 125-42.

2. Visser EJ. Chronic post-surgical pain: epidemiology and clinical implications for acute pain

management. Acute Pain 2006;8:73-81.

3. Rasmussen PV, Sindrup SH, Jensen TS, Bach FW. Symptoms and signs in patients with suspected

neuropathic pain. Pain 2004;110:461-9.

4. Steegers MAH, Snik DM, Verhagen AF, et al. Only half of the chronic pain after thoracic surgery

shows a neuropathic component. J Pain 2008;9:955-61.

5. Benedetti F, Vighetti S, Ricco C, et al. Neurophsiologic assessment of nerve impairment in

posterolateral and muscle-sparing thoracotomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998,115:841-7.

6. Ivens D, Hoe AL, Podd TJ, et al. Assessment of morbidity from complete axillary dissection. Br J

Cancer 1992;66:136-8.

7. Picchio M, Palimento D, Attanso U, et al. Randomised controlled trial of preservation or elective

division of ilioinguinal nerve on open inguinal hernia repair with polypropylene mesh. Arch Surg

2004;139:755-8.

8. Abdullah TI, Iddon J, Barr L, et al. Prospective randomized controlled trial of preservation of the

intercostobrachial nerve during axillary node clearance for breast cancer. Br J Surg 1998;85:1443-5.

9. Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf C. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet

2006;367:1618-25.

10. Tasmuth T, von Smitten K, Hietanen P, et al. Pain and other symptoms after different treatment

modalities of breast cancer. Ann Oncol 1995;6:453-9.

11. Kristensen AD, Pedersen TAL, Hjortdal VE, et al. Chronic pain after thoracotomy in childhood or

youth. BJA 2010;104:75-9.

12. Florence SL, Jain N, Pospichal MW, et al. Central reorganization of sensory pathways following

peripheral nerve regeneration in fetal monkeys. Nature 1996;381:69-71.

13. Caumo W, Schmidt AP, Schneider CN, et al. Preoperative predictors of moderate to intense

acute postoperative pain in patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand

2002;46:1265-71.

14. Diatchenko L, Slade GD, Nackley AG, et al. Genetic basis for individual variations in pain perception

and the development of a chronic pain disorder. Hum Mol Genet 2005;14:135-43.

15. Searle RD, Simpson KH. Chronic post-surgical pain. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical

Care & Pain 2009. doi:10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkp041.

16. Gerbershagen HJ, zgur E, Dagtekin O, et al. Preoperative pain as a risk factor for chronic post-

surgical pain Six month follow-up after radical prostatectomy. Eur J Pain 2009;13:1054-61.

17. Munafo MR, Stevenson J. Anxiety and surgical recovery. Reinterpreting the literature. J Psychosom

Res 2001;51:589-96.

S Afr J Anaesthesiol Analg 110 2010;16(1)

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Usg PidDokumen13 halamanUsg PidHisbulloh syarifBelum ada peringkat

- Bones Flash CardDokumen22 halamanBones Flash CardMiki AberaBelum ada peringkat

- Dr. Sourav Chakraborty (Kolkata, Durgapur)Dokumen5 halamanDr. Sourav Chakraborty (Kolkata, Durgapur)thadanikrishBelum ada peringkat

- Dental ImplantDokumen37 halamanDental ImplantrejipgBelum ada peringkat

- Quiz 3 MATERNAL BSN2 SFDokumen2 halamanQuiz 3 MATERNAL BSN2 SFElaiza Anne SanchezBelum ada peringkat

- Undetectable Hair Transplants by Dr. Ch. Krishna PriyaDokumen155 halamanUndetectable Hair Transplants by Dr. Ch. Krishna PriyaKrishna RayaluBelum ada peringkat

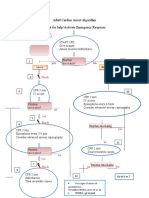

- Adult Cardiac Arrest Algorithm Shout For Help/activate Emergency ResponseDokumen1 halamanAdult Cardiac Arrest Algorithm Shout For Help/activate Emergency ResponseICU RSBMBelum ada peringkat

- Gingival Tissue ManagementDokumen144 halamanGingival Tissue ManagementMakkapati AmaniBelum ada peringkat

- EVALUATION Book Intern Medical-2023 Report 2Dokumen1 halamanEVALUATION Book Intern Medical-2023 Report 2Ahsif IsmailBelum ada peringkat

- Urine EliminationDokumen33 halamanUrine EliminationInnocent MuhumuzaBelum ada peringkat

- Menstrual - Disorders 2Dokumen24 halamanMenstrual - Disorders 2Abdibaset Mohamed AdenBelum ada peringkat

- AppendectomyDokumen51 halamanAppendectomymoqtadirBelum ada peringkat

- Paranasal Sinuses by DR SharakyDokumen21 halamanParanasal Sinuses by DR SharakyMobile AsdBelum ada peringkat

- Ob Clinical Worksheet - IntrapartumDokumen8 halamanOb Clinical Worksheet - Intrapartumcandice lavigneBelum ada peringkat

- Delorenzi 2017Dokumen3 halamanDelorenzi 2017Marilia RezendeBelum ada peringkat

- Periocular Hyaluronic Acid Fillers: Applications, Implications, ComplicationsDokumen6 halamanPeriocular Hyaluronic Acid Fillers: Applications, Implications, ComplicationsLuis Fernando WeffortBelum ada peringkat

- CPG - Management of Breast Cancer (2nd Edition)Dokumen100 halamanCPG - Management of Breast Cancer (2nd Edition)umiraihana1Belum ada peringkat

- Shock 2022 SeminarDokumen17 halamanShock 2022 Seminarrosie100% (2)

- Guide To Dental Treatment BandsDokumen2 halamanGuide To Dental Treatment BandsVikram Kapur100% (1)

- EG-580UT Operation ManualDokumen112 halamanEG-580UT Operation Manualkeng suttisangchanBelum ada peringkat

- Evidence Review 7Dokumen573 halamanEvidence Review 7Gracia Putra SecundaBelum ada peringkat

- CPT Coding Examples For Common Spine Procedures: CervicalDokumen5 halamanCPT Coding Examples For Common Spine Procedures: CervicalKrishna KumarBelum ada peringkat

- 3 High Risk PregnancyDokumen103 halaman3 High Risk PregnancyKaguraBelum ada peringkat

- 7.consent For Dental Implant SurgeryDokumen3 halaman7.consent For Dental Implant SurgeryPaul MathaiBelum ada peringkat

- Pancreatic Solid LeasionsDokumen24 halamanPancreatic Solid LeasionsEliza CrăciunBelum ada peringkat

- Special Leave Benefits For Women PDFDokumen2 halamanSpecial Leave Benefits For Women PDFJoan CarigaBelum ada peringkat

- Duodenal Injuries: E. Degiannis and K. BoffardDokumen7 halamanDuodenal Injuries: E. Degiannis and K. BoffardriftaBelum ada peringkat

- Dr. Yudha Mathan Sakti, Sp. OT (K) Limb Saving-Rahadyan Magetsari (2016)Dokumen56 halamanDr. Yudha Mathan Sakti, Sp. OT (K) Limb Saving-Rahadyan Magetsari (2016)dewiswahyuBelum ada peringkat

- Aortic Valve StenosisDokumen4 halamanAortic Valve StenosisYrag NoznipBelum ada peringkat

- Periodontology 2000 - 2023 - Liñares - Critical Review On Bone Grafting During Immediate Implant PlacementDokumen18 halamanPeriodontology 2000 - 2023 - Liñares - Critical Review On Bone Grafting During Immediate Implant Placementahmadalturaiki1Belum ada peringkat