The Persian

Diunggah oleh

Mohit Anand0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

28 tayangan100 halamanPersian

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

PDF atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniPersian

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

28 tayangan100 halamanThe Persian

Diunggah oleh

Mohit AnandPersian

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 100

THE PERSIAN SUFIS

CYPRIAN RICE, O.P.

London

GEORGE ALLEN & UNWIN LTD

RUSKIN HOUSE MUSEUM STREET

First published m 1964

Tiss Book 1s copyright under the Berne Convention,

Apart from any far dealing for the purpose of

private study, research, oriticism or review, as

permitted under the Copynght Act, 1956, no

Portion may be reproduced by any process without

wniten permission Enguiry should be made to

the publisher

© George Allen & Ununn Ltd , 1964

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN,

in 10 on x1 pomnt Old Style type

BY C, TINLING AND CO. LTD

LIVERPOOL, LONDON AND PRESCOT

CONTENTS

——_

Introductory

The Siifi Movement

The Way and Its Goal

The Seven Stages

The Mystical States

Homesickness (Firdq)

Lost in God (Fana)

The Vision of God

Two Siifi Practices

page 9

19

3r

39

55

76

83

88

ONE

INTRODUCTORY

TuE Siifi phenomenon 1s not easy to sum up or define. The

Siifis never set out to found a new religion, a mazhab or deno-

mination They_were content to 9 hive _ and work within the

framework of the Moslem religion, using texts from the ¢ Qoran

much 48 Christian mystics have used the Buble to illustrate

their tenets. Their aim was to purify and spiritualize Islam

from within, to give 1t a deeper, mystical mterpretation, and

infuse into 1t a spirit of love and liberty. In the broader sense,

therefore, in which the word religion is used in our time, their

movement could well be called a religious one, one which did

not aim at tying men down with a new set of rules but rather

at settmg them free from external rules and open to the

movement of the spirit.

This religion was disseminated mainly by poetry, 1t breathed.

in an atmosphere of poetry and song. In it the place of great

dogmatic treatises is taken by mystical romances, such as

Yusuf and Zuleikha or Leila and Majniin. Its one dogma, an

interpretation of the Moslem witness. ‘There 1s no god but

God’, is that the human heart must turn always, unreservedly,

to the one, divine Beloved.

Who was the first Sifi? Who started this astonishing

flowering of spiritual love in lyrical poetry and dedicated lives?

No one knows.

Early in the history of Islam, Moslem ascetics appeared who,

from their habit of wearing coarse garments of_wool (séf),

‘became known as Siifis. But what we now know as Siifism

awned unheralded, mysteriously, in the ninth century of our

era and already in the tenth and eleventh had reached maturity.

Among all its exponents there is no single one who could be

claimed as the initiator or founder.

ro THE PERSIAN SUFIS

Siifism is like that great oak-tree, standing in the middle of

the meadow: no one witnessed its planting, no one beheld its

beginning, but now the flourishing tree speaks for itself, is true

to origins which it has forgotten, has taken for granted.

There is a Siifi way, a Siifi doctrine, a form of spiritual

knowledge known as ‘srfdén or ma’rifat, Arabic words which

correspond to the Greek gnosis.

Siifism has its great names, its poet-preachers, its ‘saints’,

im the broad, irenical sense in which the word can be used.

Names like Maulana Rumi, Ibn al Arabi, Jami, Mansur al

Hallaj are household words in the whole Islamic world and

even beyond it.

Has it a future? Perhaps we may say that if, in the past, its

function was to spiritualize Islam, its purpose in the future will

be rather to make possible a welding of religious thought

between East and West, a vital, oecumenical commingling and

understanding, which will prove ultimately to be, in the truest

sense, on both sides, a return to origins, to the original unity.

When one speaks of the Siifis as ‘mystics’, one does not

necessarily mean to approve all their teaching or all their

methods, nor, indeed, admit the genuineness of the mystical

experiences of this or that individual. But whatever one’s pre-

conceptions or reservations, it is difficult, after a careful study

of their lives and writings, not to recognize a kinship between

the Siifi spirit and vocabulary and those of the Christian saints

and mystics.

This book is concerned mainly with the Persian mystics,

Taken all in all, what goes by the name of ‘Islamic mysticism’

is a Persian product. The mystical firé, as it Spread rapidly

over the broad world of Islam, found tinder in the hearts of

many who were not Persians: Egyptians like Dhu’l Nun,

Andalucians like Ibn’ul Arabi, Arabs like Raby’a al ’Adawiyya.

But Persia itself is the homeland of mysticism in Islém, It is

true that many I: ic mystical writers, whether Persian or

not, wrote in Arabic, but this was because that language was

in common use throughout the Moslem world for the exposition

of religious and philosophical teaching. It could, indeed, be

said that the Persians themselves took up the Arabic language

and forged from it the magnificent instrument of precise philo-

sophical and scientific expression which 1t became, after having

been used by the Arabs themselves almost exclusively -for

poetry. This was Persia’s revenge for the humiliating defeat she

suffered at the hands of the Arabs and the consequent 1mposi-

tion of the Arabic language for all religious and juridical pur-

poses. We might go on to say that Persia’s revenge for the

imposition of Islam and of the Arabic Qoran was her bid for

the utter transformation of the religious outlook of all the

Islamic peoples by the dissemination of the Siifi creed and the

creation of a body of mystical poetry which 1s almost as widely

known as the Qoran itself. The combmation im Siifism of

mystical love and passion with a daring challenge to all forms

of rigid and hypocritical formalism has had a bewitchmg and

breath-taking effect on successive Moslem generations in all

countries, an effect repeated in all those non-Moslem mulieux,

European or Asiatic, where these doctrines, often interpreted by

the most ravishingly beautiful poetry, have been discovered.

In this way Persia has conquered a spiritual domain far more

extensive than any won by the arms of Cyrus and Dams, and

one which is still far from being a thing of the past. Indeed,

one might say that through this mystical lore, expressed in an

incomparable poetical medium, Persia found herself, dis-

covered something like her true spiritual vocation among the

peoples of the world, and that her voice has now only to make

itself heard to win the delighted approval of all those seekers

and connoisseurs whose souls are attuned to perceive the mes-

sage of the usidd i azdl (the eternal master), to use Khoja

Hafiz’s phrase.

In a sense, this bold transformation of Islam from within by

the mystical mind of Persia began already in the Prophet’s

hfe-time with the part played in the elaboration and interpre-

tation of Mahomet’s message by the strange but historic figure

of Salman Farsi—Salman the Persian—to whom M. Massignon

devoted an indispensable monograph. But a sumilar influence

revealed itself in the rapid spiritualization of the person of ‘Ali

and the parallel evolution of the mystical significance of

Mahomet, around the notion of the mir muhammad:—the

12 THE PERSIAN SUFIS

‘Mahomet-light’, which seems to amount to the introduction

of a Logos doctrine into the heart of Islam, viewed as an

esoteric system. The influences, as they worked themselves out,

Jed, on the other hand, to the formation of the Shi’a, involving

the spiritual-mystical significance accorded to the Imam. At

the same time, the teaching and outlook of Mahomet himself

was progressively brought into conformity with the Siifi model

by the accumulation of a large body of akddsth (traditional

sayings) fathered onto the Prophet by successive generations.

The vigour of the Persian spiritual genius, however, is not a

phenomenon which came suddenly to light at the outset of

Islam. It was there all the time, and there are Persians whom.

I have known who claim that the stream of pure Persian

mysticism has pursued 1ts course, now open, now hidden, nght

down the ages. This is a claim which springs, maybe, more

from the Persians’ own intuition than from any positive docu-

mentation, but the assumption comes out clearly in the

writings of Suhravardi and the Ishraqi school. In any case, one

cannot but be struck by the atttraction exerted and the pene-

tration achieved by Persian religions, such as Mithraism and

Manichaeism, as far afield as the farthest frontiers of the

Roman Empire, as well as in farthest Asia and who knows

where else. The Christian Church of Persia itself, which, as

Mgr Duchesne has pointed out, rivalled even the Church of

Rome in the number of its martyrs, sent its missionaries far

and wide throughout Asia, into India, China and Japan. As to

the exploits of Christian missionaries from Persia in Japan,

facts are only now coming to light through the investigations

of Prof. Sakae Ikeda. Japanese wnters have also traced deep

influences of Persian Christianity in the emergence of the

Mahayana type of Buddhism in China.

If these facts are recorded here, it is merely in order to make

it clear that the universal radiation of the Persian spirit was

not confined to the Islamic world.

Words like ma‘rifat or irfén used to designate Siifi teaching

might lead one to conclude that theirs was essentially a specu-

lative movement. But one must wee bear in mind that it is

fundamentally a practical scienée; the teaching of a way of _

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Cadence Tutorial EN1600Dokumen5 halamanCadence Tutorial EN1600Mohit AnandBelum ada peringkat

- Study - PCB Dimension (Length) : Evaluation Board VSWR & Efficiency (Simulation Results)Dokumen6 halamanStudy - PCB Dimension (Length) : Evaluation Board VSWR & Efficiency (Simulation Results)Mohit AnandBelum ada peringkat

- Tai-Saw Technology Co., LTD.: Approval Sheet For Product SpecificationDokumen6 halamanTai-Saw Technology Co., LTD.: Approval Sheet For Product SpecificationMohit AnandBelum ada peringkat

- Gnss Antennas: An Introduction To Bandwidth, Gain Pattern, Polarization, and All ThatDokumen6 halamanGnss Antennas: An Introduction To Bandwidth, Gain Pattern, Polarization, and All ThatMohit AnandBelum ada peringkat

- Antennas and Propagation: Chapter 5: Antenna ArraysDokumen35 halamanAntennas and Propagation: Chapter 5: Antenna ArraysMohit AnandBelum ada peringkat

- S-16-13-III (Music) PDFDokumen32 halamanS-16-13-III (Music) PDFMohit AnandBelum ada peringkat

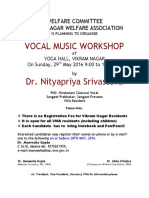

- Vocal WorkshopDokumen1 halamanVocal WorkshopMohit AnandBelum ada peringkat

- Wireless Charging of Mobile Phone Using Microwaves or Radio Frequency SignalsDokumen3 halamanWireless Charging of Mobile Phone Using Microwaves or Radio Frequency SignalsMohit AnandBelum ada peringkat

- ShriBramhaSamhitaPrayers SelectedDokumen2 halamanShriBramhaSamhitaPrayers SelectedMohit AnandBelum ada peringkat

- Bhabha Atomic Research Centre Ph.D. Programme in Basic Sciences-2015Dokumen1 halamanBhabha Atomic Research Centre Ph.D. Programme in Basic Sciences-2015Mohit AnandBelum ada peringkat

- Unicode SolutionDokumen4 halamanUnicode SolutionMohit AnandBelum ada peringkat

- Single-Chip Global Positioning System Receiver Front-End: General Description FeaturesDokumen9 halamanSingle-Chip Global Positioning System Receiver Front-End: General Description FeaturesMohit AnandBelum ada peringkat

- Academic QualificationDokumen16 halamanAcademic QualificationMohit AnandBelum ada peringkat

- The Mystical Women of The ApocalypseDokumen10 halamanThe Mystical Women of The ApocalypseMohit AnandBelum ada peringkat

- Web Revcache Review 9074Dokumen4 halamanWeb Revcache Review 9074Mohit AnandBelum ada peringkat

- Music Contexts: A Concise Dictionary of Hindustani Music: by Ashok Damodar RanadeDokumen2 halamanMusic Contexts: A Concise Dictionary of Hindustani Music: by Ashok Damodar RanadeMohit AnandBelum ada peringkat

- Nityapriya Srivastava: Hindustani Classical Vocal Recital byDokumen1 halamanNityapriya Srivastava: Hindustani Classical Vocal Recital byMohit AnandBelum ada peringkat

- The History of JugniDokumen2 halamanThe History of JugniMohit AnandBelum ada peringkat

- Index PDFDokumen3 halamanIndex PDFMohit AnandBelum ada peringkat

- Triveni & Sanskriti: A Film in Bengali (Dokumen1 halamanTriveni & Sanskriti: A Film in Bengali (Mohit AnandBelum ada peringkat