Artikel Jurnal B PDF

Diunggah oleh

Maya MudaJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Artikel Jurnal B PDF

Diunggah oleh

Maya MudaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Affilia

http://aff.sagepub.com/

The Social Construction of Concealment Among Chinese Women in Abusive Marriages in Hong Kong

Angelina Yuen-Tsang and Pauline Sung

Affilia 2005 20: 284

DOI: 10.1177/0886109905277614

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://aff.sagepub.com/content/20/3/284

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Affilia can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://aff.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://aff.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://aff.sagepub.com/content/20/3/284.refs.html

>> Version of Record - Jun 27, 2005

What is This?

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by Ferdinand Prawiro on August 21, 2013

10.1177/0886109905277614

Affilia Fall 2005 Yuen-Tsang, Sung

The Social Construction of Concealment

Among Chinese Women in Abusive

Marriages in Hong Kong

Angelina Yuen-Tsang and Pauline Sung

This article presents the findings of a qualitative study of 15 Chinese women in

Hong Kong who experienced marital conflict and family violence. Adopting a nar-

rative approach, the authors found that the women had gradually developed a cul-

ture of concealment through a process of social construction. Individual, environ-

mental, and cultural factors had combined to develop and reinforce their tendency to

conceal their situation and to remain silent. This culture of concealment was highly

oppressive and had a negative impact on the womens personal, interpersonal, and

social well-being. Social work strategies to break this pattern of behavior and to lib-

erate the women from the culture of concealment are explored.

Keywords: abusive marriage; concealment; disclosure; face; social

construction

In Chinese culture, face, or ones image in the public eye, is a central factor

in the determination of human behavior and social interactions (Bond, 1993;

Yang, 1992). The obsessive concern with face has had a significant impact on

the way in which the Chinese handle their private affairs. Because marital

conflict and family violence are often regarded as shameful and disgraceful

to both the victims and their family members, the victims tend to conceal

these occurrences and avoid the public eye.

We conducted in-depth interviews with 15 Chinese women in Hong

Kong who experienced marital conflicts and family violence. Using the nar-

rative approach (Cronon, 1992; Dainte & Lightfoot, 2004; Josselson &

Lieblich, 1993; Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, & Zilber, 1998; Mishler, 1986;

Riessman, 1993; Rosenwald & Ochberg, 1992), we found that these women

had suffered from prolonged emotional abuse and that they had gradually

developed a culture of concealment through a process of social construc-

tion (Gergen, 1999, 2001; Gergen & Davis, 1985; Raskin & Bridges, 2002).

AFFILIA, Vol. 20 No. 3, Fall 2005 284-299

DOI: 10.1177/0886109905277614

2005 Sage Publications

284

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by Ferdinand Prawiro on August 21, 2013

Yuen-Tsang, Sung 285

Individual, environmental, and cultural factors had combined to develop

and reinforce their tendency to conceal their situation and to remain silent.

This culture of concealment was highly oppressive and had a negative

impact on the personal, interpersonal, and social well-being of these

women.

In this article, we discuss the development of the culture of concealment

throughout the life course (Elder, 1992; Hareven, 2000; Hockey, 2003; Pratt &

Fiese, 2004; Riley, 1988; Yuen-Tsang, 1999) of the Chinese women who were

undergoing marital conflicts, using a social constructionist perspective. The

individual, family, peer group, and contextual forces that were instrumental

in facilitating the development of the culture of concealment are delineated.

We also describe the social work strategies that may be effective in breaking

this pattern of behavior and liberating women from its tyranny.

METHOD

We are social work educators and consultants with local social service

agencies who have had a great deal of experience counseling married

women in Hong Kong and on the Chinese mainland. Given the significant

impact of cultural values on human behavior, we decided to conduct a qual-

itative study to understand the cultural meanings that women have

attached to their experiences in marital crises. The objective was to develop

approaches to social work practice that are sensitive to the cultural back-

ground of those who are undergoing marital conflict.

We adopted a narrative approach, encouraging the participants to nar-

rate their personal accounts of their traumatic experiences. Narrative theory

provided us with a framework for understanding how the women inter-

preted their lived experiences and constructed their narrative identities.

Gergen (2001) suggested that a life-course perspective will shed light on the

social, cultural, and historical milieu in which individuals have developed

their self-identities and ways of coping with the challenges of life through-

out time. In our study, we adopted this theoretical perspective to guide our

development of a deeper understanding of how the women struggled

through their marital problems and the reasons why they played a passive

role in dealing with unjust treatment in their marital relationships.

We took the participants into their past worlds and facilitated their nar-

ration of their stories from their own perspectives, using these stories as

texts that were organized around critical events in their lives. The approach

was based on the understanding that

how individuals recount their historieswhat they emphasize and omit, their

stance as protagonists or victims, the relationship [that] the story establishes

between teller and audienceall shape what individuals can claim of their

own lives. Personal stories are not merely a way of telling someone about

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by Ferdinand Prawiro on August 21, 2013

286 Affilia Fall 2005

ones life; they are the means by which identities may be fashioned.

(Rosenwald & Ochberg, 1992, p. 1)

We chose to use the narrative approach in the interviews because per-

sonal narratives are essential meaning-making structures that can be used

to reconstruct the cultural meaning that participants have attached to their

experiences. By preserving, appreciating, and analyzing these narratives,

we were able to understand the process of creation. We did not set guide-

lines for the interviews so as to provide enough room for the women to

speak for themselves. This kind of first-person perspective enhanced our

understanding of the construction of the womens identities and the dilem-

mas that the women encountered in their relational networks and enabled

us to evolve conceptions that were grounded in the womens voices (Yuen-

Tsang, 2002). Together with the historical backgrounds provided by the

women, narrative analysis illuminated the interaction between the

womens experiences and their social and historical contexts, because the

experiences of the respondents are much more important than the objective

facts (Riessman, 1993, p. 3).

Fifteen Chinese women who experienced marital crises were identified

and referred by social workers from three social service agencies in Hong

Kong. These women were either divorced or separated, had children living

with them, and had received the help of social workers at some stage in their

ordeals. Of the 15 women, 4 were aged 25 to 35, 8 were aged 36 to 45, and 3

were aged 46 to 55. Four women were new immigrants from the Chinese

mainland who migrated to Hong Kong after they married, and the rest were

born and raised locally. Six women, including the four new immigrants, had

completed some primary education; four had completed lower secondary

education; and five had completed high school. Those who had received a

lower secondary or primary education tended to work as semiskilled fac-

tory workers or low-paid service workers prior to their marriage, and those

who had completed high school had worked mostly as clerical workers.

Although these women tended to stay in their jobs after they married, at

least half quit their jobs after giving birth to their children, because their rel-

atively low salaries could not compensate for the high cost of babysitters or

nurseries. As a result, the majority of women were economically dependent

on their husbands. The economic recession in Hong Kong in recent years

had further aggravated the employment situation and had deprived these

women of opportunities to seek economic independence even if they

wanted to.

Having identified the women with the help of the three social service

agencies and having obtained their consent to participate in the study, we

conducted the interviews either at the participants homes or in the agen-

cies interview rooms. Most of the interviews took 2 to 3 hr to complete, and

the women agreed to have the interviews tape-recorded. Verbatim tran-

scriptions were made afterward, and we analyzed the narratives as a team.

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by Ferdinand Prawiro on August 21, 2013

Yuen-Tsang, Sung 287

We did not have any preconceptions of or prior hypotheses about the mean-

ing and impact of the participants experiences and preferred to let the

stories speak for themselves.

During the interviews and data analysis, we realized that many women,

especially those who were in their mid-30s or older, had a strong tendency

to conceal their prolonged emotional abuse in their marriages for extended

periods. In contrast, those who were younger were less constrained by tra-

ditional practices and patriarchal values, probably because of the relatively

more progressive social climate in which they were embedded during their

formative years. But even the younger ones were subject to the influence of

patriarchal values and practices that are deeply entrenched in the Chinese

culture, although the intensity of such influences had been weakened by the

impact of social change and modernization. The womens levels of educa-

tion did not have a significant impact on the womens disclosure or conceal-

ment behaviors. Indeed, Madam Bai, the silent sufferer quoted in this arti-

cle, had received a high school education and was considered relatively

more educated than the other women in her age cohort. We discovered that

many of the participants were strongly influenced by the traditional familial

and cultural teachings that they experienced in their early years, irrespec-

tive of their social and educational backgrounds, and that these values and

conceptions had been gradually internalized and had shaped their percep-

tions of, as well as their approaches to addressing, their abusive marriages.

Through a rigorous process of data analysis, we gradually discovered that a

culture of concealment existed among these women and that this culture

was socially constructed through the interplay of individual, familial, social,

and cultural forces. We found that this culture of concealment was highly

oppressive and had a negative impact on the womens personal, interper-

sonal, and social well-being.

THE CONCEPT AND SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF CONCEALMENT

The concept of concealment is not unique to Chinese culture. In recent

years, there has been a keen interest among social psychologists in the West

in the practices of concealment and disclosure and their relationship to pro-

fessional help-seeking behavior (Cepeda, Benito, & Short, 1998; Dunham &

Senn, 2000; Gordon & Paci, 1997; Kelly & Achter, 1995; Larson & Chastain,

1990). Kelly and Achter (1995) used the term self-concealment, which they

defined as a predisposition to hide distressing and potentially embarrassing

personal information. They studied the association between self-concealment

and the likelihood of seeking professional psychological help. Gordon

and Paci (1997) used a narrative approach to understand concealment and

disclosure practices. They found that nondisclosure, which is commonly

practiced by physicians in Tuscany in dealing with cancer patients, was

deeply entrenched in a larger cultural narrative, which they termed social

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by Ferdinand Prawiro on August 21, 2013

288 Affilia Fall 2005

embeddedness. Although the practice of nondisclosure has been fiercely chal-

lenged by physicians in the United States for its lack of openness and its dis-

respect of patients right to be informed, the social embeddedness was

regarded by residents of Tuscany as a demonstration of social unity and

hierarchy and as a means of adapting to the inevitable necessities of life by

using a narrative to construct a sense of group protection. Dunham and

Senn (2000), who studied the tendency of abused women to withhold infor-

mation and to conceal domestic violence, discovered that the majority of

women who disclosed abuse to friends and relatives omitted information to

limit and manage their confidantes reactions to their disclosure and to

enhance the likelihood of receiving social support.

Concealment practices are historically and culturally specific and are

strongly influenced by the orientations of societies in which they arise. The

self of the key actors who are involved in the process is constantly recon-

structed, depending on the social milieu. According to the traditional

understanding of self, there is a real and objective self that is one dimen-

sional and consistent. However, from a postmodern perspective, the self is

fluid, mobile, and constantly changing. Gergen (1991), a key proponent of

social construction theory, postulated that the original concept of self was

eroded in modern society because of social saturation and that a new con-

cept of self, as a public creation, emerged. According to Gergen, the self does

not exist objectively and independently; rather, it is brought into being and

shaped by relational networks. Individuals are created within relationships

and are constantly reconstructed in accordance with the historical, cultural,

and social milieu in which these relationships are embedded. Hence, rela-

tionships are central to the understanding of self. The individual is not

viewed as an autonomous agent; the construction of self is largely deter-

mined by others, particularly peer groups and significant others. It is

through interaction with these people that the self is established and consol-

idated. Thus, the self changes in response to different situations and times.

Gergen (1991) observed that ones identity is continuously emergent, re-

formed, and redirected as one moves through the sea of ever-changing rela-

tionships (p. 139). This view is similar to the sociological concept of the

looking-glass self, proposed by Cooley (1993). Cooley maintained that the

self can be identified only if we use others as mirrors. Similarly, Goffman

(1973) argued that daily life is a drama in which individuals construct a suit-

able self that is appropriate to their role expectations and perform their

scripts accordingly.

THE CULTURE OF CONCEALMENT AMONG THE PARTICIPANTS

Almost all the 15 women in our study concealed their marital conflict,

even from their closest relatives, especially during the early stage. Numer-

ous strategies were adopted to create the pretence that they were still

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by Ferdinand Prawiro on August 21, 2013

Yuen-Tsang, Sung 289

enjoying a stable family life. The tendency to conceal family conflicts among

Chinese women is so intense and prevalent that it has developed into a cul-

ture of its own. The prevalence of the culture of concealment among these

women was evident, and the womens determination to hide their situation

from their relatives was taken to extraordinary lengths. The following are

striking examples of these womens resolve to conceal their experiences and

their underlying fears and concerns.

Madam Fei: The Disillusioned Dreamer

Madam Fei, aged 35, became a factory worker after she completed junior

high school. She was the eldest daughter of her parents, who longed to have

a son but ended up having three daughters. Her mother wanted her to

marry a good man and to find a good refuge that [she] could depend on for

the rest of her life. However, Madam Fei fell in love with an immigrant

from China who was hired as a casual laborer at her factory. She accepted his

courtship despite severe opposition from her family, especially her mother,

who thought that he was too poor and could never provide a comfortable

home for her daughter. After 2 years of secret courtship, Madam Fei was

married in the registry, and none of her relatives attended the ceremony. She

and her husband moved into a partitioned room in a shabby apartment near

the factory and worked with extreme diligence to save enough money to

establish a dream house of [their] own. Madam Fei wanted to prove to her

mother that she had made the right choice, so that her mother could have

face in front of relatives. During this period, Madam Fei had two abortions,

because she wanted to concentrate on earning money. After 5 years, she and

her husband had saved enough money that he was able to start a small busi-

ness trading clothing in Guangzhou, China. Madam Fei was proud of her

husbands achievements; she felt that she was finally able to stand up in

front of her relatives by realizing her dreams of having a stable home and a

small business.

Madam Feis dreams were shattered when her husband told her, in their

8th year of marriage, that he had a woman outside and that he was divorc-

ing Madam Fei because the woman was already pregnant. Despite her

repeated pleas, her husband moved away and never returned. Madam Fei

did not tell any of her friends, workmates, or relatives about her marital cri-

sis. At the end of the workday, she would stay at home with the door locked.

She thought of attempting suicide several times, but she restrained herself

because her mother had high blood pressure, and she knew that her

mothers health would deteriorate if she committed suicide. For 2 years,

during the Chinese New Year, she stayed home, switched off all the lights,

ate only biscuits and canned food, and pretended to others that she was on

vacation with her husband. She said that she felt like a dead person with-

out a soul while she moved around in the darkness of her home. She felt

that she had no choice because

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by Ferdinand Prawiro on August 21, 2013

290 Affilia Fall 2005

I felt so ashamed and guilty that my marriage had failed. Everyone thought

that my marriage would fail in the beginning, and I hoped that I could prove to

them, especially my mother, that I had chosen the right person. But, in the end,

I had failed them and had brought shame to the whole family. I dare not face

my family because I do not want them to be disappointed and to lose face in

front of their friends and relatives.

Madam Fei also pretended to her workmates that she had a good relation-

ship with her husband but that he had to stay in Guangzhou because of his

business. She was worried that her workmates would, as she put it, look

down upon me and laugh behind my back if they knew that her husband

had deserted her. She was finally persuaded to reveal her secret to a social

worker whom she accidentally contacted through a womens hot-line

service.

Madam Bai: The Silent Sufferer

Madam Bai, aged 55, had concealed her abusive marriage for 25 years

before she finally disclosed the long-kept secret. She was the only daughter

of a rich landlord in Guangdong, China, and had a happy childhood. Her

family was purged during the anti-Rightist Movement and later during the

Cultural Revolution. Her parents arranged for her to escape to Hong Kong

when she was 16 and entrusted her to the guardianship of her aunt. Her par-

ents later died during the Cultural Revolution. Her aunt, who was well off,

treated her as well as she treated her own children, although Madam Bai

regarded herself as not one of them and always longed for her parents.

She managed to finish high school, but could not continue her education

because of her low marks in English. She worked as an office clerk for a few

years before a distant relative introduced her to her husband, who was

working as a supervisor in her relatives factory; the relative found him to be

reliable and hardworking. Mr. and Madam Bai decided to get married after

2 years of courtship. All her relatives approved of the marriage and were

relieved that Madam Bai had finally found a trustworthy man on whom

she could depend for the rest of her life. Madam Bai was also happy

because, as she said, I would finally have a home of my own after so many

years of drifting around.

As soon as they were married, Madam Bai decided to give all the money

and jewelry that she brought from China, as well as the dowry she received

from her aunt, to her husband so that he could open a small printing factory.

She hoped that her husband would become financially independent and

would not be looked down on by her relatives. Madam Bai did not keep any

money in her own name, because she believed that a married woman

should be a follower of her husband and that a womans pride rests with

her husband. At the beginning of her marriage, Madam Bai helped her

husband with the factorys accounts, but she decided to stay at home after

she gave birth to their first son one year later. Madam Bai quickly became

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by Ferdinand Prawiro on August 21, 2013

Yuen-Tsang, Sung 291

pregnant again. One night, when she turned up unexpectedly at the factory,

she discovered that her husband was having an affair with a female factory

worker, who was actually her distant cousin. Madam Bai was so shocked

and furious with her husband that she nearly lost her baby. After that night,

she said that her husband changed to another person; he shouted at her

and beat her for no reason. Her husband usually stayed at the factory with

the cousin and seldom returned home.

Instead of telling her aunt and relatives about her husbands affair,

Madam Bai decided to conceal the truth and keep silent because

I felt ashamed that I could not keep my husband. . . . I did not want to disap-

point my aunt and my relatives because they had high hopes for me and my

marriage. My aunt wanted me to have a good marriage, so she could be

answerable to my parents. If she found out that I was being mistreated by my

husband, she would feel very guilty and would feel that she could not face my

parents who have passed away.

As a result, Madam Bai continued to meet regularly with her aunt and rel-

atives, but she did not reveal the secret about her marital conflict to them or

anyone else. When her husband realized that she was afraid to admit her sit-

uation to her relatives, he blackmailed her by threatening to reveal the

secret to the whole world whenever she fought back. They even had an

agreement that in return for leaving her husband alone and not interfering

with his affairs, Madam Bai would receive financial aid, and her husband

would pretend to be a dutiful spouse in the presence of her family.

Madam Bai kept her secret from her relatives for 25 years. Her two sons

were the only ones who knew her real situation, but they were forced to con-

ceal the truth because they were financially dependent on their father.

Madam Bai had to beg her husband to pay for their sons school fees, and

once her husband hit her with an iron stool when she asked him for money.

She decided to keep silent, partly because of her fear of disappointing her

relatives and partly because of her financial dependence on her husband.

Her secret was finally disclosed 2 years earlier when she was fiercely beaten

by her husband, and her wounds were accidentally discovered by her

cousin, who is a physician. Her cousin was shocked to find that Madam Bai

had endured such a prolonged period of silent suffering. Because, at the

time of her cousins discovery, Madam Bais aunt had died and her sons

were adults, Madam Bai was persuaded to share her secret with her close

relatives and to seek a formal divorce from her husband.

These two cases clearly illustrate the complexity of the feelings experi-

enced by Chinese women in unhappy relationships, the reasons why they

conceal their situation, and the strategies they adopt to deceive others. The

other 13 participants expressed similar fears and concerns and were also

anxious to conceal their marital discord. The culture of concealment was

also evident in the stories of all the other women interviewed. Madam Chiu,

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by Ferdinand Prawiro on August 21, 2013

292 Affilia Fall 2005

for instance, did not dare to let her parents and relatives know that her hus-

band had actually left her behind and was cohabiting with another woman

on the Chinese mainland. She decided to conceal the matter by keeping a

distance with friends and relatives and moved to live alone in the new

town, pretending that she had found a job there. Madam Yu did not have

money to buy milk and food for her children, because her husband spent all

his income on gambling. However, instead of seeking help from relatives

and friends, she preferred to borrow money from loan sharks and later got

into debt because of her failure to return the money and the accumulated

interest on time. Similarly, Madam Fong, a clerical worker and mother of

two, decided to conceal from her children the fact that her husband had

abandoned the family and was cohabiting with another woman. She told

her children that her husband was working as a seaman and had to stay

away from home for long periods. She believed that her children would be

emotionally hurt and would be looked down on by their classmates if

they knew of their father s departure.

In summary, the culture of concealment is a common pattern found

among all the 15 Chinese women whom we have interviewed. The womens

common reasons for concealment included the fear of losing face in front of

their friends, neighbors, and relatives; the fear of disappointing their parents

and relatives; the fear that their children might be viewed with contempt by

their peers; the fear of losing the financial support of their husbands; and the

fear that there would be no chance in the future for reconciliation if their

marital conflict was made public. Most participants were willing to disclose

their secrets only to outsiders, such as social workers, physicians and

nurses, and volunteers of hot-line services, because they did not have a rela-

tionship with these strangers and could conceal their identities from these

strangers even while seeking help.

DISCUSSION

Social construction theory was extremely useful in helping us to under-

stand the evolution and prevalence of the culture of concealment among

Chinese women who experience marital conflict. The identity and values of

the participants were shaped by their peer groups and significant others.

The culture of concealment is not an objective construct that applies to all

Chinese women. Rather, this culture was created, maintained, and succes-

sively reinforced by a process of co-construction among the participants,

their significant others, and the social environment in which they were

embedded. In this section, we use the cases of Madam Bai, Madam Fei, and

other participants to illustrate the processes by which the culture of conceal-

ment was being socially constructed through successive internal and

external reinforcements during the womens lives.

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by Ferdinand Prawiro on August 21, 2013

Yuen-Tsang, Sung 293

Internalization of Patriarchal Beliefs and Practices

Most of the participants were brought up in traditional Chinese families

that emphasized womens submission to their elders, parents, and hus-

bands. From childhood, they all were educated to believe that womens

place is in the family; that the happiness of women rests within the fam-

ily; and that women should obey their fathers before marriage, obey their

husbands after marriage, and obey their sons when old. These patriarchal

beliefs and practices were entrenched in these women, who assumed that

they would be happy and fulfilled if they could find good husbands and

establish harmonious homes.

Madam Bais yearning for fulfillment in marriage was even more intense

because she had lost her own family during the Cultural Revolution and

longed to find a substitute. Her only aspirations were to have a family of her

own and to become a loyal wife and a loving mother. Her image of the per-

fect wife was reinforced by her relatives in Hong Kong, who also believed

that a womans ultimate destiny is in the home and that finding a good

husband is the solution to all previous unhappiness. The relatives deter-

mination to help Madam Bai find a suitable husband and their view of mar-

riage as a panacea heightened her expectations of marriage.

Thus, the normative gender-role expectations of Madam Bai and Madam

Fei were socially constructed during their childhood and youth. Their per-

sonal values were molded by their immediate and extended families in a

highly patriarchal social milieu. As they grew up, these women gradually

internalized the belief that a womans worth is measured by her perfor-

mance of certain roles. Traditional values, which were originally external to

them, gradually became inscribed as integral and inseparable aspects of

their self.

External Reinforcement of Patriarchal Beliefs

Madam Feis courtship did not proceed smoothly, because her fianc was

viewed with disfavor by her family members, including her mother with

whom she was close. However, Madam Fei married her husband despite

her familys opposition. She felt torn between the traditional values of filial

piety and obedience to her parents and elderly relatives and her love for her

husband. After her marriage, she tried to regain her familys acceptance by

demonstrating her husbands worth. Her struggle to earn money and to

help her husband establish his own small business was her way of gaining

reentry to her family network. The two abortions that she had, despite her

love of children, were indicative of her determination to prove to her family

that she had made the right choice of a partner. Her efforts finally resulted in

her reconciliation with her family and the acceptance of her husband by her

mother. Madam Fei treasured the hard-won approval of her family and her

reconciliation with her extended family members. Her rebellious self was

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by Ferdinand Prawiro on August 21, 2013

294 Affilia Fall 2005

resubjugated to the dominance of her traditional self, and she finally

reclaimed her lost role as an obedient daughter and a submissive wife.

Madam Bais concealment practice was also reinforced by family and

peer pressure. After the tragic loss of her parents in the Cultural Revolution,

her relatives were keen to help Madam Bai find a loving husband and a

happy home. Their deep concern added to the pressure on Madam Bai; she

was determined to have an ideal home. Because Madam Bais husband was

hand picked by her relatives and her marriage was regarded as a happy

ending, both sides were determined to keep the marriage intact. Madam

Bais heightened expectations of marriage were therefore the result of the

co-construction between herself and her extended family members. Madam

Bai happily adopted her new identity as a submissive and caring wife and a

loving mother to fulfill her socially constructed role expectations. She was

content with this newly created self as a submissive wife and a loving

mother and was determined to perform her roles to the best of her abilities.

The Co-construction of the Culture of Concealment

The culture of concealment was co-constructed by the participants and

their significant others through a process of dynamic interaction. Madam

Fei and Madam Bai were totally unprepared for the marital conflict that

emerged in their marriages. Their discovery of their husbands unfaithful-

ness shattered their dreams of having loving husbands and harmonious

families. They had been prepared since childhood to assume the roles of

loyal wife and loving mother, and they had internalized the belief that mar-

riage is for life and must be kept intact against all odds. To admit that ones

marriage had failed would entail the loss of the self that they had nurtured

for years. Because marriage was perceived as their ultimate goal in life, they

had developed no other resources to fall back on should they become sepa-

rated or divorced. It is, therefore, understandable that Madam Fei and

Madam Bai would conceal their unhappy marital situations because of their

inability to accept the failure of their marriages.

The culture of concealment was sustained and perpetuated by the inter-

play of individual, group, environmental, and cultural factors. Madam Fei

did not have the confidence to break her silence because of her entrenched

patriarchal belief that women should be blamed for broken marriages

because of their inability to keep their husbands satisfied. She believed that

her relatives, especially her mother, would be greatly disappointed if they

learned that her marriage had failed. Moreover, she assumed that disclosure

would lead to ridicule from her friends and workmates. Her intense concern

to save face and to regain the respect of her family members exacerbated

her fear of disclosure. The fact that her relatives seemed to have finally

accepted her husband and were proud of his success forced Madam Fei to

perpetuate the lie. In fact, she had to work hard to sustain the false image

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by Ferdinand Prawiro on August 21, 2013

Yuen-Tsang, Sung 295

among her relatives, and this deception, in itself, made it more difficult to

escape the culture of concealment.

Madam Bai was similarly trapped by this culture of concealment as a

result of the interplay of personal, familial, environmental, and cultural fac-

tors. Her deeply entrenched patriarchal beliefs, together with her intense

love for her children and her fear of losing the financial support of her hus-

band, prevented her from revealing the truth. Moreover, she had forced her

children to collaborate in her concealment because of her intense fear that

her children would become the objects of ridicule or pity.

In all our 15 cases, the culture of concealment had gradually evolved

through a process of social construction. Individual, environmental, and

cultural factors intertwined to develop and reinforce these womens patriar-

chal beliefs and their tendency to conceal their marital conflict and to remain

silent. The culture of concealment was highly oppressive; it undermined the

personal, interpersonal, and social well-being of Madam Fei, Madam Bai,

and all our interviewees for a long time.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SOCIAL WORK PRACTICE

From the foregoing analysis, it is evident that the culture of concealment

is highly oppressive and negatively affects womens personal, interper-

sonal, and social well-being. To help Chinese women who are undergoing

marital conflicts break away from their habitual pattern of concealing their

marital discord and be liberated from the tyranny of this culture of conceal-

ment, social work interventions have to be developed or further enhanced

to serve the womens needs at different levels.

Personal Level

The central factor that contributed to the development and maintenance

of the culture of concealment among the participants was the womens

entrenched patriarchal beliefs. The belief that womens place is in the fam-

ily; that the happiness of women rests within the family; and that

women should obey their fathers before marriage, obey their husbands

after marriage, and obey their sons when old had become so entrenched

that they were unable to accept any deviation from the norm. Their fear of

being ridiculed and isolated if they disclosed their marital discord was a

self-constructed fear that had been steadily reinforced by their significant

others and by external forces in the social-cultural milieu in which they were

embedded.

To help Chinese women who are undergoing marital conflicts to disclose

their problems and to seek help during crises, it is therefore crucial that the

women should be emancipated from their own patriarchal beliefs. In fact,

many social workers in Hong Kong are keenly aware of the need to help

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by Ferdinand Prawiro on August 21, 2013

296 Affilia Fall 2005

their female clients be released from the bondage of their patriarchal orien-

tations and are actively using the empowerment model in their practice

(Wong, 1999; Yip, 2004). Many social workers are using the empowerment

model in their daily practice with the elderly, families and children, persons

with mental problems, and women with the aim of facilitating their clients

to be emancipated from oppressive cultural beliefs and practices (Wong,

1999). However, it has been observed that direct borrowing of the empower-

ment model from the West may not be appropriate in the Chinese context

and that a culturally sensitive empowerment model that is grounded in Chi-

nese cultural orientations has to be developed (Yip, 2004).

In view of the analysis presented here, it is essential that social workers

are sensitized to the need for gender-sensitive and culturally sensitive prac-

tice. A gender-sensitive and culturally sensitive approach should be

adopted in the intervention process, taking into consideration the social and

cultural orientations of these women and their fears and inhibitions. Social

workers need to be able to listen to the inner voices of Chinese women who

are undergoing marital conflicts and to empathize with the fear and ten-

sions that these women are experiencing. It is only when they are able to

appreciate the personal stories of these women from their own perspectives

that they will be able to move closer to helping the women be liberated from

the tyranny of deeply entrenched patriarchal beliefs. With such an orienta-

tion, social workers could then help these women to analyze the negative

impact of their patriarchal beliefs, to demystify their ungrounded fears, and

to disentangle themselves from the bondage of these beliefs in ways that

these women consider to be appropriate.

One of the major problems encountered in the process of helping Chinese

women in abusive marriages, however, is the difficulty in reaching out to

them. Given the womens fear of disclosing their marital discord and their

tendency to conceal their secrets, it is obvious that they will not be easily

approachable by social workers. Thus, efforts have to be made to reach out

to them in an unthreatening manner and to minimize their fear of disclo-

sure. Services that allow these women to remain anonymous and give them

the freedom to ventilate their fears and problems in a safe environment will

be preferred. We accidentally found that at least half the women whom we

interviewed were initially identified through telephone hot lines provided

by service organizations in Hong Kong. The use of telephone hot lines

seems to be a useful approach, especially for women who are still

entrenched in the culture of concealment and are not comfortable revealing

their identities to their helpers. The use of unknown but empathic outsiders

and strangers as helpers during the beginning stage of the help-seeking pro-

cess seems to be more acceptable than the use of insiders who are close to the

women. This fact explains the extreme popularity of telephone hot lines for

women in Hong Kong and in many major cities on the Chinese mainland

that provide counseling services for women. After they break the ice and

reveal their secrets to strangers in the hot lines or through other anonymous

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by Ferdinand Prawiro on August 21, 2013

Yuen-Tsang, Sung 297

means, these women could be gradually encouraged to approach social

workers openly for help.

Interpersonal Level

Chinese women in abusive marriages are fearful of disclosing their

secrets to others because they do not want to bring shame to themselves,

their children, and their family members. But this culture of concealment is

highly oppressive and has created much anxiety, fear, and tension among

women who are involved in it. The prolonged suppression of emotions and

feelings that are associated with their marital discord is detrimental to their

well-being and to their mental health. Social work intervention with Chi-

nese women in abusive marriages must therefore take into consideration

the feelings of these women and respect their obsessive concern for conceal-

ment. Hence, social workers should not attempt to force these women to

disclose their secrets to unsuitable persons and under inappropriate

circumstances.

In our experience, mutual support groups that endeavor to provide sup-

port for women who are undergoing similar marital conflicts are desirable.

Because these women are highly sensitive and do not want to lose face in

front of their friends and relatives, they would not easily reveal their marital

problems to people who are close to them. However, they would feel much

more at ease when they share their problems with those who are experienc-

ing similar problems. Revealing marital conflicts to those who are in the

same boat would provide an excellent opportunity for ventilation, sharing,

and support in a safe environment in which the women could interact and

share without the fear of being ridiculed or their secrets being exposed.

Community Level

Because the culture of concealment is embedded in the social milieu and

is intertwined with the social and cultural beliefs of the society, it is essential

that efforts are made to educate the public so as to reduce the stigma on those

whose marriages have failed. Public education programs that are aimed at

raising the gender awareness of the public and gradually eradicating patri-

archal beliefs in society in the long term have to be developed. Because

beliefs and conceptions are usually developed and gradually evolve in the

formative stages of life, the need to integrate gender-sensitive perspectives

into the primary and secondary curricula is critical. It is only when the soci-

ety has developed a culture that respects the dignity of women and provides

opportunities for womens self-actualization and free expression of feelings

that the tyranny of the culture of concealment will be overcome.

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by Ferdinand Prawiro on August 21, 2013

298 Affilia Fall 2005

REFERENCES

Bond, M. H. (1993). Beyond the Chinese face: Insights from psychology. Hong Kong: Oxford Uni-

versity Press.

Cepeda, B. A., Benito, A., & Short, P. (1998). Self-concealment, avoidance of psychological ser-

vices, and perceived likelihood of seeking professional help. Journal of Counseling Psychol-

ogy, 45(1), 58-64.

Cooley, C. H. (1993). The looking-glass self. In C. Lemert (Ed.), Social theory: The multicultural

and classic readings. (pp. 204-206). Boulder, CO: Westview.

Cronon, W. (1992). A place for stories: Nature, history, and narrative. Journal of American His-

tory, 78, 1347-1376.

Dainte, C., & Lightfoot, C. (Eds.). (2004). Narrative analysis: Studying the development of individ-

uals in society. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dunham, K., & Senn, C. Y. (2000). Minimizing negative experiences: Womens disclosure of

partner abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15, 251-261.

Elder, G. H., Jr. (1992). Models of the life course. Contemporary Sociology, 21, 632-635.

Gergen, K. J. (1991). The saturated self: Dilemmas of identity in contemporary life. New York: Basic

Books.

Gergen, K. J. (1999). An invitation to social construction. London: Sage.

Gergen, K. J. (2001). Social construction in context. London: Sage.

Gergen, K. J., & Davis, K. E. (1985). The social construction of the person. New York: Springer-

Verlag.

Goffman, E. (1973). The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Overlook.

Gordon, D. R. & Paci, E. (1997). Disclosure practices and cultural narratives: Understanding

concealment and silence around cancer in Tuscany, Italy. Social Sciences and Medicine, 44,

1433-1452.

Hareven, T. K. (2000). Families, history and social change: Life course and cross-cultural perspec-

tives. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Hockey, J. C. (2003). Social identities across the life course. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Josselson, R., & Lieblich, A. (Eds.). (1993). The narrative study of lives (Vol. 1). Newbury Park,

CA: Sage.

Kelly, A. E., & Achter, J. A. (1995). Self-concealment and attitudes toward counseling in uni-

versity students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42, 40-46.

Larson, D. G., & Chastain, R. L. (1990). Self-concealment: Conceptualization, measurement,

and health implications. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9, 439-455.

Lieblich, A., Tuval-Mashiach, R., & Zilber, T. (1998). Narrative research: Reading, analysis and

interpretation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mishler, E. G. (1986). Research interviewing: Context and narrative. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Pratt, M. W., & Fiese, B. H. (Eds.). (2004). Family stories and the life course across live and genera-

tions. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Raskin, L. D., & Bridges, S. K. (2002). Studies in meaning: Explaining constructivist psychology.

New York: Pace University Press.

Riessman, C. K. (1993). Narrative analysis. Newbury Park: CA: Sage.

Riley, M. W. (1988). Social change and the life course. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Rosenwald, G. C., & Ochberg, R. (1992). Storied lives: The cultural politics of self-understanding.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Wong, M. F. (1999). Problem of women in Hong Kong: A feminist perspective and a social

work response. In K. W. Ho & A. W. K. Yuen-Tsang (Eds.), Towards the new millennium: The

new trend of social work theories and practice (pp. 172-179). River Edge, NJ: Global.

Yang, Z. F. (1992). A preliminary discussion on how to study the personality of the Chinese. In

K. S. Yang & A. B. Yu (Eds.), The psychology of the Chinese: Concepts and methods. Taipei: Kwei

Kuan.

Yip, K. S. (2004). The empowerment model: A critical reflection of empowerment in Chinese

culture. Social Work, 49, 479-487.

Yuen-Tsang, A. W. K. (1999). Chinese communal support networks. International Social Work,

42, 359-372.

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by Ferdinand Prawiro on August 21, 2013

Yuen-Tsang, Sung 299

Yuen-Tsang, A. W. K. (2002). Generating a theory of Chinese communal networks: The

grounded theory method in action. Grounded Theory Review, 3, 13-20.

Angelina Yuen-Tsang, Ph.D., is a professor and head of the Department of Applied Social

Sciences, Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Pauline Sung, Ph.D., is an associate professor in the Department of Applied Social Sciences,

Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by Ferdinand Prawiro on August 21, 2013

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Audience Centered Approach BeebeDokumen15 halamanAudience Centered Approach BeebeluiscopaconaBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 7 Clients Response To IllnessDokumen7 halamanChapter 7 Clients Response To IllnessCatia FernandesBelum ada peringkat

- "Be The Best You Can Be": Things You Can Do To Improve Performance and Maximize PotentialDokumen54 halaman"Be The Best You Can Be": Things You Can Do To Improve Performance and Maximize PotentialJoseph MyersBelum ada peringkat

- Sample Reaction PaperDokumen3 halamanSample Reaction PaperAnonymous Gi063kBelum ada peringkat

- Sas 1 Module 1Dokumen2 halamanSas 1 Module 1Joshua Romea88% (8)

- VisionDokumen9 halamanVisionapi-2699066890% (1)

- Aspen HYSYS Dynamics: Dynamic Modeling: Former Course Title/Number Who Should AttendDokumen2 halamanAspen HYSYS Dynamics: Dynamic Modeling: Former Course Title/Number Who Should AttendCHANADASBelum ada peringkat

- Intervensi Perilaku Sadar Bahaya Rokok Melalui HumDokumen20 halamanIntervensi Perilaku Sadar Bahaya Rokok Melalui HumMaya MudaBelum ada peringkat

- Surat Lamaran Kantor HukumDokumen1 halamanSurat Lamaran Kantor HukumMaya MudaBelum ada peringkat

- F - Keterampilan - Kimia - XI IPS 1 (KIMIA)Dokumen12 halamanF - Keterampilan - Kimia - XI IPS 1 (KIMIA)Maya MudaBelum ada peringkat

- F Keterampilan Kimia XI IPS 2 (KIMIA)Dokumen16 halamanF Keterampilan Kimia XI IPS 2 (KIMIA)Maya MudaBelum ada peringkat

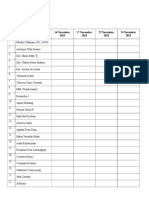

- Daftar Hadir Guru Panitia AnstcupDokumen2 halamanDaftar Hadir Guru Panitia AnstcupMaya MudaBelum ada peringkat

- Termodinamika Kimia: See Discussions, Stats, and Author Profiles For This Publication atDokumen2 halamanTermodinamika Kimia: See Discussions, Stats, and Author Profiles For This Publication atMaya MudaBelum ada peringkat

- Wa0030Dokumen11 halamanWa0030Maya MudaBelum ada peringkat

- Termodinamika Kimia: See Discussions, Stats, and Author Profiles For This Publication atDokumen2 halamanTermodinamika Kimia: See Discussions, Stats, and Author Profiles For This Publication atMaya MudaBelum ada peringkat

- Pengembangan Pangan Tradisional Berbasis Jagung Mendukung Diversifikasi PanganDokumen9 halamanPengembangan Pangan Tradisional Berbasis Jagung Mendukung Diversifikasi PanganAnastasia BillinBelum ada peringkat

- 2146 6135 2 SM PDFDokumen12 halaman2146 6135 2 SM PDFkawanramaBelum ada peringkat

- Pablo PunkDokumen1 halamanPablo PunkMaya MudaBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction PDFDokumen7 halamanIntroduction PDFMaya MudaBelum ada peringkat

- Representasi SosialDokumen24 halamanRepresentasi SosialMaya Muda100% (1)

- Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology 2007 Van de Vliert 156 721Dokumen18 halamanJournal of Cross Cultural Psychology 2007 Van de Vliert 156 721Maya MudaBelum ada peringkat

- Curiculum Vitae Personal DataDokumen1 halamanCuriculum Vitae Personal DataMaya MudaBelum ada peringkat

- Helena Prisca Nobo Mario David Lela Muda: Together With Their FamiliesDokumen2 halamanHelena Prisca Nobo Mario David Lela Muda: Together With Their FamiliesMaya MudaBelum ada peringkat

- ApplyDokumen1 halamanApplyMaya MudaBelum ada peringkat

- What Is Leading?: (Also CalledDokumen3 halamanWhat Is Leading?: (Also CalledYukimura SasakiBelum ada peringkat

- Dewan 1995. St. Thomas and Pre-Conceptual IntellectionDokumen8 halamanDewan 1995. St. Thomas and Pre-Conceptual IntellectionUmberto MartiniBelum ada peringkat

- Early Child Development and CareDokumen18 halamanEarly Child Development and CareRicardo NarváezBelum ada peringkat

- Basic Schools of ManagementDokumen12 halamanBasic Schools of ManagementM GBelum ada peringkat

- Patterns of FunctioningDokumen5 halamanPatterns of FunctioningMhia Mhi-mhi FloresBelum ada peringkat

- PDF Self Evaluation Grid Fe3Dokumen12 halamanPDF Self Evaluation Grid Fe3api-438611508Belum ada peringkat

- PID Tuning Assignment: Sir Dr. Ali MughalDokumen7 halamanPID Tuning Assignment: Sir Dr. Ali MughalHaseeb TariqBelum ada peringkat

- Training E-Brochure For Senior ManagementDokumen4 halamanTraining E-Brochure For Senior ManagementdineshdivekarBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 1 Learning Environment and Chapter 2Dokumen5 halamanChapter 1 Learning Environment and Chapter 2lolaingBelum ada peringkat

- Risk Assesment MethodDokumen4 halamanRisk Assesment MethodRIANA3411Belum ada peringkat

- Exploring w02 Grader h1Dokumen5 halamanExploring w02 Grader h1AnkitPatelBelum ada peringkat

- Research 2018Dokumen93 halamanResearch 2018Sueang Suicram Azotal AreliugaBelum ada peringkat

- Informatics - It's Scope and Met - A - I. Mikhailov PDFDokumen15 halamanInformatics - It's Scope and Met - A - I. Mikhailov PDFMaria Cristina MartinezBelum ada peringkat

- Michael P. Henry Dissertation (2017), Curriculum and Instruction, Northern Illinois UniversityDokumen510 halamanMichael P. Henry Dissertation (2017), Curriculum and Instruction, Northern Illinois UniversityDr. Michael HenryBelum ada peringkat

- Values Education: Self DevelopmentDokumen80 halamanValues Education: Self DevelopmentJaynard Mahalin ArponBelum ada peringkat

- Wehner Thies - Role Theory, Narratives, and Interpretation: The Domestic Contestation of RolesDokumen26 halamanWehner Thies - Role Theory, Narratives, and Interpretation: The Domestic Contestation of RolesFrancisca Javiera Villablanca MartínezBelum ada peringkat

- Theory of Cognitive Development - HardDokumen12 halamanTheory of Cognitive Development - HardkyzeahBelum ada peringkat

- Transactional Analysis Journal: Therapeutic CoachingDokumen4 halamanTransactional Analysis Journal: Therapeutic CoachingNarcis NagyBelum ada peringkat

- Elaborated and Restricted CodesDokumen9 halamanElaborated and Restricted CodesB KKBelum ada peringkat

- Sliding Mode Control HandoutDokumen42 halamanSliding Mode Control HandoutGabriel MejiaBelum ada peringkat

- Lec# 1 - Introduction To ANNDokumen8 halamanLec# 1 - Introduction To ANNSamer KamelBelum ada peringkat

- Marital Quality, Individualism/Collectivism and Divorce Attitude in TurkeyDokumen8 halamanMarital Quality, Individualism/Collectivism and Divorce Attitude in TurkeyAnonymous izrFWiQBelum ada peringkat

- EntropyDokumen40 halamanEntropyDude MBelum ada peringkat