Secondary Glaucoma 2

Diunggah oleh

astriHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Secondary Glaucoma 2

Diunggah oleh

astriHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

See

discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/11000311

Secondary glaucoma

Article in Clinical and Experimental Optometry February 2000

DOI: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2000.tb04914.x Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

6 23

1 author:

Anthony Hall

Alfred Hospital

53 PUBLICATIONS 764 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Anthony Hall on 06 October 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

C L I N I C A L A N D E X P E R I M E N T A L

OPTOMETRY

Secondary glaucoma

Anthony JH Hall MD FRACO FRACS Purpose: To review the common causes of secondary glaucoma.

Department of Ophthalmology, Methods: Review of current literature.

Royal Melbourne Hospital Results: Secondary open and closed angle glaucomas are an important cause of ocular

morbidity and vision loss in our community. Secondary glaucoma occurs with acquired

ocular diseases (pigment dispersion, pseudoexfoliation, intraocular infection,

intraocular inflammation and retinal vascular disease), blunt anterior segment injury,

intraocular surgery (especially corneal grafting and congenital cataract surgery) and

topical corticosteroid use. The medical treatment of secondary glaucoma is different

from that of primary open angle glaucoma and must be tailored for the individual

patient. Surgical treatment of secondary glaucoma carries a higher risk of complica-

tions and a lower rate of success than does surgical treatment of primary open angle

glaucoma.

Conclusions: Secondary glaucoma occurs with a variety of intraocular conditions and

after a variety of intraocular insults. Awareness of patients at high risk should enable

early detection and referral for appropriate management.

Accepted for publication: 22 June 2000 (Clin Exp Optom 2000; 83: 3: 190-194)

Key words: corticosteroid, glaucoma, pigment dispersion, pseudoexfoliation, traumatic glaucoma.

Secondary glaucoma is an important cause aetiology of the secondary glaucoma. Gen-

eral guidelines for treatment will be given

After blunt trauma

of ocular morbidity in our community,

occurring in around 0.2 per cent of Vic- for each type of secondary glaucoma. After prolonged or intermittent use of

torians over the age of 40 years,' and an This paper will not review secondary topical, inhaled or systemic steroids

even more common cause of glaucoma in glaucoma as a result of congenital malfor- In aphakic patients and after corneal

the developing world.' The secondary mations, that is, those associated with con- grafting

glaucomas are a heterogeneous group of genital cataracts, aniridia a n d o t h e r After an attack of inflammation or infection,

conditions with a wide range of causes and congenital anterior congenital malforma- especially herpes simplex or zoster

clinical manifestations requiring a variety tions. I will limit the scope of the paper to In patients who have had congenital

of treatment strategies. This article is not glaucoma associated with acquired ocular cataracts or any other congenital

intended to be a comprehensive review disorders (Table 1) and especially those anterior segment abnormality

but an introduction to the clinically im- likely to be of clinical relevance to prac-

portant secondary glaucomas. Treatment tising optometrists.

Table 1 . Important conditions in which

of secondary glaucoma is complicated and

secondary glaucoma may be forgotten

must be individualised for every patient,

and differs markedly according to the

Clinical and Experimental Optometry 83.3 May-June 2000

190

Secondary glaucoma Hull

PATHOLOGY detachment, abnormally thickened in iris-lens contact while the lens position

lens et cetera. remains constant. Future studies may

Different forms of secondary glaucoma The underlying final mechanism of show a t h e r a p e u t i c benefit of laser

are associated with different types of angle trabecular outflow obstruction is usually peripheral iridotomy in pigmentary

damage and different final pathways of obvious from the clinical situation and the glaucoma.

raised intra-ocular pressure.3 These examination findings.

changes can be condensed essentially into

PSEUDOEXFOLIATION

two basic types: secondary open angle

GLAUCOMA ASSOCIATED WITH

glaucoma and secondary angle closure Pseudoexfoliation is an important cause

OCULAR DISEASE

glaucoma. of secondary glaucoma and is covered

Secondary open angle glaucoma has a in another chapter in this issue of the

variety of underlying pathological causes. Pigmentary glaucoma journal.

They can be summarised as follows: Pigmentary glaucoma was initially de-

1 . Trabeculitis (inflammatory angle dam- scribed over 50 years ago as a rare clinical

NEOVASCULAR GLAUCOMA

age) with secondary mechanical block- entity. Since then, pigmentary glaucoma

age by plasma proteins, trabecular has become recognised as one of the most Neovascular (or rubeotic) glaucoma is

damage mediated by cytokines released common and important forms of second- characterised by the growth of new vessels

by inflammatory cells, mechanical ary open-angle glaucoma. As with other on the iris and particularly in the angle,

blockage to outflow by inflammatory secondary glaucomas, pigmentary glau- and a secondary increase in intraocular

cells o r sclerosis of the meshwork coma usually affects a much younger pressure. These new vessels may be obvi-

associated with hyaline membrane patient population than primary open- ous but often they are hard to discern

formation. angle glaucoma. It has a special predilec- clinically. There are only a few common

2. Obstruction of the intertrabecular tion for myopic males. The defining clini- clinically important causes of neovascular

spaces by cellular material, for exam- cal features of pigmentary glaucoma are glaucoma. Most neovascular glaucoma

ple, macrophages in phacolytic glau- midperipheral iris transillumination de- occurs as a complication of either ischae-

coma, blood-filled macrophages in fects, Krukenberg spindles (characteristic mic central retinal vein occlusion or pro-

hyphaema, erythroclastic or ghost cell pigment deposits on the central corneal liferative diabetic retinopathy. Occasion-

glaucoma, invasion by neoplastic cells endothelium in a vertical oval distribu- ally, neovascular glaucoma develops as a

etcetera. tion) and a heavily pigmented trabecular consequence of ocular ischaemia (oph-

3. Obstruction of the outflow system by meshwork. thalmic or internal carotid artery occlu-

abnormal extracellular materials, for The mechanism of pigment dispersion sion). Rubeotic glaucoma may uncom-

example, pigmentary glaucoma, appears to be a rubbing between iris monly develop following rubeosis caused

pseudoexfoliative glaucoma, silicon oil pigment epithelium and packets of lens by ocular inflammation or ocular tumours

glaucoma. zonules caused by a backwards concavity (retinoblastoma o r m e l a n o m a ) . In

4. Changes in the metabolic activity of the of the iris diaphragm, possibly associated rubeosis associated with retinal ischaemia

trabecular meshwork cells, for exam- with an i n h e r e n t abnormality of the (that is, diabetes, retinal vein occlusion

ple, steroid induced glaucoma. pigment epithelium. The mechanism of o r ophthalmic artery occlusion) the

5. Increases in episcleral venous pressure, aqueous outflow obstruction is believed to neovascular stimulus is probably vascular

for example, carotid-cavernous fistula. involve accumulation of the pigment gran- endothelial growth

Si m i 1arl y, second a r y a n g 1e c 1o su r e ules in the trabecular meshwork, followed In typical acute neovascular glaucoma

glaucoma has a variety of underlying by denudation, collapse, and sclerosis of the eye is painful and photophobic with a

pathological causes: the trabecular beams. There is evidence very high pressure, often in the 50s to 70s.

Synechial angle closure caused by to suggest that the presence of pigment There is marked conjunctival injection

abnormal new vessels, for example, granules alone in the trabecular mesh is and corneal oedema. The iris new vessels

rubeotic glaucoma. not enough to decrease aqueous outflow. are usually visible through the cloudy cor-

Synechial angle closure caused by Conventional management includes nea. After acute treatment and corneal

abnormal epithelial o r fibrous standard anti-glaucoma drugs, laser clearing the angle is visible and charac-

downgrowth. trabeculoplasty (which is particularly teristically the picture is of a smooth

Synechial angle closure caused by effective in pigmentary glaucoma) and fil- zipped-up line of iridocorneal adhesion.

inflammatory infiltrate, for example, tering surgery. Studies performed looking Prior to this end stage and prior to final

post uveitis. at anterior chamber morphology follow- angle closure, the new vessels may be vis-

Non-synechial angle closure caused by ing laser peripheral iridotomy in patients ible climbing up from the iris across the

abnormal lens/iris diaphram anatomy, with pigmentary glaucoma have demon- ciliary body and scleral spur to the trabecu-

for example, ciliary body swelling or strated flattening of the iris and a decrease lar mesh. It has long been taught that any

Clinical and Experimental Optometry 83.3 May-June 2000

191

Secondary glaucoma Hall

vessels crossing the scleral spur onto the controlling the inflammation alone is not

UVEITIC/INFLAMMATORY

trabecular mesh are ahnormaL7 enough to control the pressure, specific

GLAUCOMA

The differential diagnosis falls into two anti-glaucoma treatment will be needed.

stages. The first is the differential of Raised intraocular pressure is a common In general, in patients with uveitic glau-

abnormal-looking iris vessels. The second and frequently serious complication of all coma, treatments that worsen inflamma-

is the differential of an acute increase in forms of uveitis. There are several mecha- tion, exacerbate posterior synechia forma-

IOP with cloudy cornea. With regard to nisms at play in uveitic glaucoma." The tion or worsen macular oedema, are best

the first, the list is short: abnormal iris inflammatory c e 11s themselves , t h e avoided. This means that prostaglandin

vessels may be due to true ruheosis (from cytokines they release, the architectural analogues (for example, latanoprost),

any cause hut usually ischaemia), abnor- changes accompanying uveitis and the miotics and adrenaline are contraindi-

mal iris vessels also occur in Fuch's corticosteroid therapy used to treat the cated. The most commonly used topical

heterochromic iridocyclitis and pseudoex- inflammation all can lead to or exacerbate treatments for uveitis glaucoma are beta

foliation. Abnormally prominent iris ves- glaucoma. Inflammatory cells may clog blockers, alpha agonists (hut not adrena-

sels can occur with intraocular inflamma- t h e trabecular mesh o r a n active line) and topical carbonic anhydrase in-

tion of any cause-but these vessels do not trabeculitis may impede outflow. After hibitors. Oral carbonic anhydrase inhihi-

cross the scleral spur onto the trabecular prolonged inflammation p e r m a n e n t tors a r e used m o r e often in uveitic

meshwork. An acute presentation with changes may lead to irreversible mesh glaucoma than in general glaucoma

high IOP and cloudy cornea may he due damage, so-called trabecular sclerosis. practice because patients with uveitic glau-

to rubeotic glaucoma, ordinary acute Peripheral anterior synechiae may form coma tend to be younger and are worse

angle closure glaucoma, hypertensive and block outflow or posterior synechia candidates for glaucoma surgery.

iritis, phacolytic glaucoma or ghost cell may cause pupil block and iris bomb6. Those patients who fail medical treat-

glaucoma. Although secondary glaucoma may ment for their uveitic glaucoma may be

The treatment is aimed at diagnosing complicate any form of uveitis, it is much candidates for surgical therapy. In these

those eyes that are at risk of rubeotic glau- more common in and, indeed, almost patients, wherever possible, surgery

coma before rubeosis develops, or as soon characteristic of, several specific uveitic should he delayed until the inflammation

as rubeosis develops, and preventing the conditions. The important underlying has been quiet for at least three months.

development of full-blown neovascular uveitis diagnoses with uveitic glaucoma Oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors may

glaucoma. All patients with central reti- are: herpetic (simplex and zoster) kerato- he required to tide the patients over for

nal vein occlusion should be assessed to uveitis, Fuchs' heterochromic iridocycli- that period. Even with adequate control

determine the degree of ischaemia and tis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis associ- of inflammation, surgery in these eyes is

either treated with pan-retinal photoco- ated iridocyclitis, Posner-Schlossman difficult and conventional drainage sur-

agulation or followed closely to allow early syndrome, syphilitic uveitis, chorioretinal gery is at increased risk of failure. In some

detection of iris neovascularisation, and toxoplasmosis and sarcoidosis.'" cases of uveitic glaucoma, Molteno tubes

then treated. As there are several mechanisms at play may he the best surgical option." Laser

Treatment after the development of in uveitic glaucoma, careful examination traheculoplasty carries an increased risk

neovascular glaucoma, especially if the is critical to determine the underlying of causing anterior synechiae and is con-

angle is entirely closed, is much more dif- aetiology of the raised intraocular pres- traindicated in uveitic glaucoma.

ficult. In this situation, treatment is aimed sure in each case. It is important to assess

at lowering the pressure in the short term the level of inflammation, the degree of POST-TRAUMATIC GLAUCOMA

enough to clear the cornea and allow pan- angle damage o r synechial closure, the

retinal photocoagulation. After the reti- extent of posterior synechia a n d iris The incidence of significant angle dam-

nal ischaemia has been addressed, topi- bomb6 and importantly the evidence for age with rim microhyphaemas may he as

cal or oral glaucoma treatment may he disc damage. high as 20 per cent.12 The incidence of

successful. If not, glaucoma surgery may Diagnostic and therapeutic decisions secondary glaucoma after anterior seg-

be attempted. Even if the iris neovas- are guided by careful delineation of the ment injury is increased if there are other

cularisation has been addressed a n d pathophysiology of each individual case. signs of significant injury, such as trau-

treated, there is still a high rate of failure The goal of treatment is to minimise per- matic cataract (especially cataract severe

of conventional glaucoma surgery and manent structural alteration of aqueous enough to require surgerylg),iris damage,

Molteno tubes or cyclodestructive proce- outflow and to prevent damage to the angle recession of greater than 180 degrees

dures may be required. Surgical manage- optic nerve head. Treatment is first and o r posterior dislocation of the lens.14Even

ment of neovascular glaucoma carries a foremost aimed at effective control of the in these cases at high risk, secondary glau-

higher failure rate than surgical manage- inflammation and in the majority of cases coma may not develop for many years after

ment of other complicated secondary controlling the inflammation alone will the injury and patients at risk should be

glaucomas." control the pressure. In those cases, where followed life-long to detect glaucoma as

Clinical and Experimental Optometry 83.3 May-June 2000

192

Secondary glaucoma Hall

early as possible. The lifetime incidence of uveitic glaucoma, in many cases pros- plicated retinal detachment repair and

of glaucoma may be as high as eight per taglandin analogues, miotics and argon silicon oil is as high as 18.5 per cent.2ti

cent in those with significant angle laser trabeculoplasty may be contraindi- Silicon oil may lead to permanent angle

damage.I5 cated. Patients with post-operative glau- damage and many of these patients re-

In general, treatment of angle recession coma are at high risk of failure for con- quire long-term glaucoma management.

glaucoma is best achieved with modalities ventional drainage surgery a n d may

that reduce aqueous production (for ex- require adjunctive anti-metabolites.

GLAUCOMA ASSOCIATED WITH

ample, beta blockers) rather than improve Glaucoma after penetrating kerato-

SYSTEMIC DISEASE OR DRUGS

trabecular outflow (miotics or argon laser plasty is a significant clinical problem. It

trabeculoplasty) . The long-term success of may occur early after corneal grafting and

drainage surgery for angle recession glau- the incidence of early glaucoma may be Steroid-induced glaucoma

coma is not as high as for uncomplicated as high as 20 per cent in those patients There is much debate about the incidence

glaucoma.16 It may be that in medically having combined corneal grafting and of steroid induced-glaucoma, but it seems

uncontrolled post-traumatic angle reces- other intraocular surgery.?' The long-term clear that the incidence of a steroid-

sion glaucoma, trabeculectomy with anti- incidence of glaucoma after even uncom- induced pressure rise is higher in patients

metabolite therapy is the most effective plicated penetrating keratoplasty may be with glaucoma or a family history of glau-

primary surgical procedure.I7 as high as 21 per cent."' Post-corneal graft coma.2i In the normal population, even

glaucoma is more common in patients with short-term exposure, the incidence

who a r e also aphakic o r have had a of some pressure response may be as high

GLAUCOMA ASSOCIATED WITH

vitrectomy or complicated anterior seg- as 58 per cent. Around one-third of peo-

OCULAR SURGERY

ment reconstruction along with their ple will have a moderate or marked in-

Glaucoma used to be a common compli- corneal graft.2' There are a number of rea- crease in intraocular pressure after expo-

cation of cataract surgery but with mod- sons for glaucoma after even uncompli- sure to topical steroids.2xT h e r e are

ern techniques it has become much less cated penetrating keratoplasty. There may important differences in the incidence of

common. There is a high incidence of be underlying angle damage as part of the steroid-induced pressure rise and glau-

glaucoma after intracapsular cataract sur- reason that the cornea failed in the first coma between different topical steroids,

gery but the incidence is much lower after place; or there may be angle damage from but even low potency topical steroids can

modern phakoemulsification style cata- the graft surgery or some accompanying cause pressure rises." Systemic or inhaled

ract surgery. In fact many authors have surgery, the post-operative inflammation steroids are also implicated in producing

suggested that on average intra-ocular or the use of post-operative steroids; and a rise in IOP, but not as frequently or as

pressure falls (by up to 3 mmHg'') after all these may contribute to the pressure reliably as topical steroids. The exact

routine phakoemulsification surgery in rise. There is evidence that a reduction in aetiology of steroid-induced glaucoma

normal patients and those with ocular the use of post-operative steroids signifi- remains unclear, but it is possible to

hypertension and even in those with glau- cantly decreases the incidence of high IOP demonstrate an in vitro change in the

coma.Ig There are some forms of cataract post grafting, but unfortunately a reduc- metabolic a n d phagocytic activity of

surgery that especially predispose the tion in the use of post-operative steroids trabecular mesh cells in the presence of

patients to post-operative glaucoma. also increases the incidence of graft steroids. The onset of steroid-induced

Patients with anterior chamber lenses, rejection.24 pressure rise is variable but the pressure

patients having had intracapsular cataract It is critically important to follow for rise generally resolves within weeks after

extraction (and especially with vitreous in glaucoma for the rest of their lives, all pa- steroid withdrawal.'" In patients in whom

the anterior c h a m b e r ) , patients who tients who have had penetrating kerato- it is not possible to stop the topical ster-

develop epithelial downgrowth, and espe- plasty. In the medical treatment of post- oids, medical treatment of increased IOP

cially children who have cataract surgery corneal graft glaucoma any drugs that may may be necessary.

are all prone to post-operative glaucoma. initiate or exacerbate rejection (for exam- There are a huge number of other

Aphakic patients and especially aphakic ple, prostaglandin analogues) or lead to causes of secondary glaucoma that, while

o r pseudophakic children should be endothelial damage (for example, topical important, are less common and shall not

followed in the long term for glaucoma. carbonic anhydrase inhibitors) should be be discussed in detail. These include pri-

Acute glaucoma is very common with avoided. No surgical procedure is ideal for mary and secondary malignant disease,"

retained lens fragments after phakoemuls- the management of medically uncon- raised episcleral venous pressure, a

ification surgery ( u p to 36 per cent of trolled post-corneal graft glaucoma and all number of forms of lens-induced glau-

patients), but is usually effectively treated procedures are associated with late failure, coma and malignant glaucoma.

with vitrectomy." hypotony or visual loss in a proportion of

Treatment of post-cataract glaucoma patients.25

depends on the cause. As in the treatment The incidence of glaucoma after com-

Clinical and Experimental Optometry 83.3 May-June 2000

193

Secondary glaucoma Hall

terior chamber lens implantation in chil- Cooper MI,, Mattox C, FrangieJP, Wu HK.

CONCLUSION dren. J Cat Kgrnct Surg 1997; 23 Suppl 1: Zurakowski D. Comparison of mitornycin c

669-674. trabeculectomy, glaucoma drainage device

Secondary glaucoma is an i m p o r t a n t clini-

14. Sihota R, Sood NN, Agarwal HC. Traumatic implantation, and laser neodymium: YAG

cal and public h e a l t h problem. It t e n d s glaucoma. Arta Ophlhnlmol 1995: 73: 252- cyclophotocoagulation in the management

t o affect y o u n g e r patients t h a n primary 254. of intractable ghucoma after penetrating

g l a u c o m a and early d e t e c t i o n is impor- 15. Salmon JF, Mermoud A, Ivey A, Swanevelder keratoplasty. Ophthnlmology 1998; 105: 1550-

t a n t . Practising o p t o m e t r i s t s s h o u l d be SA, Hoffman M. The detection of post- 1556.

traumatic angle recession by gonioscopy in 26. Montanari P, Troiano P, Marangoni P, Pinotti

aware o f t h e patients w h o are a t risk of

a population-based glaucoma survey. Oph- D, Ratiglia R, Miglior M. Glaucoina after

secondary glaucoma a n d should screen thalmology 1994; 101: 18441850. vitreo-retinal surgery with silicone oil injcc-

appropriately. 16. Mrrmoud A, Salmon JF, Straker C, Murray tion: epidemiologic aspects. In1 Ophtholmol

AD. Post-traumatic angle recession glau- 1996; 20: 29-31.

REFERENCES coma: a risk factor for bleb failure after 27. Armaly MF. Effect of corticosteroids on

1. Mensor MD, McCarty CA, StanislavskyYL, trabeculectomy. Br J Ophtholmol 1993; 77: intraocular pressure and fluid dynamics 11.

Livingston PM, Taylor HR. The prevalence 631-634. The effect of dexamethasone in the glau-

of glaucoma in the Melbourne Visnal Im- 7. Mermoud A, Salmon JF, Barron A, Straker comatous eye. Arch Ophthalmol1963; 70: 492-

pairment Project. Ophthalmology 1998; 105: C, Murray AD. Surgical management of 499.

733-739. post-traumatic angle recession glaucoma. 28. Becker B, Mills DW. Corticosteroids and

2. Strohl A, Poui S, Wattiez R, Roesen B, Mino Ophthnlmology 1993: 100: 634-642. intraocular pressure. Arch Ophthalmol1963;

de Kaspar H, Klauss V. Secondary glaucoma 8. Kim DD, Doyle JW,Smith MF. Intraocular 70: 500-507.

in Paraguay. Aetiology a n d incidence. pressure reduction following phacoemuls- 29. Akingbehin AO. Comparative study of the

1999; 96: 359-363.

O/>hlh/d~~tology ification cataract extraction with posterior intraocular pressure effects of fluoro-

3. Lee WR. Doyne Lecture. The pathology of chamber lens iniplantation in glaucoma metholone 0.1 % versus dexamethasone

the outflow system in primary and second- patients. Ophthnl Surg I.asms 1999; 30: 37- 0.1%. Hr J Ophlhnlmol 1983; 67: 661-663.

ary glaucoma. Ey? 1995; 9: 1-23. 40. 30. Urban RC, Dreyer EB. Corticosteroid in-

4. Farrar SM, Shields MB. Cnrrent concepts 19. Shingleton BJ, Gamell LS, ODonoghue duced glaucoma. Int Ophthdmol Clin 1993;

in pigmentary glaucoma. Surv Ophthalmol. MW, Baylus SL, King R. Long-term changes 33: 135-139.

1993; 37: 233-252. in intraocular pressure after clear corneal 31. Lee V, Cree IA, Hungerford JL. Ring

5. Breingan PJ, Esaki K, Ishikawa H, Liebniann phacoemulsification: normal patients versus melanoma-a rare cause of refractory glatt

JM- Greenfield DS, Ritch R. Iridoleiiticular glancoma suspect and glaucoma patients. ,] coma. HrJ Ophthnlmol 1999; 83: 194198.

contact decreases following laser iridotomy Cal RPfrnct Surg 1999; 25: 885-890.

for pigment dispersion syndrome. Arch 20. Vilar NF, Flynn HWJr, Smiddy WE, Murray Authors Address:

Ophthalmol 1999; 117: 325-328. TG, Davis JL, Rubsamen PE. Removal of

Dr A n t h o n y JH Hall

6. Sone H. OkudaY, KawakamiY, Hanatani M. retained lens fragments after phacoemnls-

Suruki H, Kozawa T, Honmura S, ydmashita ification reverses secondary glaucoma and D e p a r t m e n t of Ophthalmology

K. Vascnlar endothelial growth factor level restores visual acuity. Ophthalmology 1997: Royal M e l b o u r n e Hospital

in aqueous humour of diabetic patients with 104: 787-791. Grattan Street

rubeotic glaucoma is markedly elevated. 21. Chien AM, Schmidt CM, Cohen EJ, Rajpal Parkville VIC 3052

Di&t~s Carp 1996; 19: 1306-1307. RK, Sperber LIT, Rapuano CJ, Moster M,

AUSTRALIA

7. Chandler PA, Grant WM. Lectures on glau- Smith M, Laibson PR. Glaucoma in the im-

coma. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger, 1965: mediate postoperative period after pen-

268. etrating keratoplasty. AmJO/~hthrslmollIl93;

8. Mills RP. Reynolds A. Emond MJ, Barlow 115: 71 1-714.

WE, Leen MM. Long-term survival of 22. I n g J , Ing HH, Nelson I.R, Hodge DO,

Molteno glaucoma drainage devices. Oph- Bourne WM. Ten-year postoperative results

thrrlmology 1996; 103: 299-305. of penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmoloa

9. Moorthy RS, Mermoud A. Baerveldt G , 1998; 105: 1855-1865.

Miiickler DS, Lee PP, Rao NA. Glaucoma 23. Sihota R, Sharma N, Panda A, Aggarwal HC,

associated with uveitis. Surv Ophthalmol Singh R. Post-penetrating keratoplasty glau-

1997; 41: 361-394. coma: risk factors, management and visual

10. Panek UC, Holland GN, Lee DA, outcome. Aust NZJOphthalmoll998; 26: 305-

Christensen RE. Glaucoma in patients with 309.

uveitis. BrJ Ophlhalmol 1990; 74: 223-227. 24. Perry HD, Dorinenfeld ED, Acheampong A,

11. Valimaki J , Airaksinen PJ, Tuulonen A. Kanellopoulos AJ, Sforza PD, DAversa G,

Molteno implantation for secondary glau- Wallerstein A, Stern M. Topical Cyclosporin

coma injuvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arch A in the management of postkeratoplasty

Ophlhnlmol 1997; 115: 1253-1256. glaucoma and corticosteroid-induced ocu-

12 Clarke WN, Noel LP. Outpatient treatment lar hypertension (CIOH) and the pentttra-

of microscopic and rim hyphernas in chil- tion of topical 0.5% Cyclosporin A into the

dren with tranexamic acid. CanJOphthalmol cornea and anterior chamber. CL4O,]our-

1999; 28: 82.5-327. nal1998; 24: 159-165.

13. Brady KM, Atkinson CS,Kilty 1-4, Hiles DA. 25. A y a h RS. Pieroth L. Vinals AF, Goldstein

Glaucoma after cataract extraction and pos- MH, Schnman JS, Netland PA, Dreyer EB,

Clinical and Expcrirnental Optornew). 83.3 May-Jirnr 2000

194

View publication stats

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- 5c3f1a8b262ec7a Ek PDFDokumen5 halaman5c3f1a8b262ec7a Ek PDFIsmet HizyoluBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Pavement Design1Dokumen57 halamanPavement Design1Mobin AhmadBelum ada peringkat

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- E0 UoE Unit 7Dokumen16 halamanE0 UoE Unit 7Patrick GutierrezBelum ada peringkat

- BMOM5203 Full Version Study GuideDokumen57 halamanBMOM5203 Full Version Study GuideZaid ChelseaBelum ada peringkat

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Technology Management 1Dokumen38 halamanTechnology Management 1Anu NileshBelum ada peringkat

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Review1 ScheduleDokumen3 halamanReview1 Schedulejayasuryam.ae18Belum ada peringkat

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Android Developer PDFDokumen2 halamanAndroid Developer PDFDarshan ChakrasaliBelum ada peringkat

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Existential ThreatsDokumen6 halamanExistential Threatslolab_4Belum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- DC 7 BrochureDokumen4 halamanDC 7 Brochures_a_r_r_yBelum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Appendix - Pcmc2Dokumen8 halamanAppendix - Pcmc2Siva PBelum ada peringkat

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- AnticyclonesDokumen5 halamanAnticyclonescicileanaBelum ada peringkat

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Service Manual: SV01-NHX40AX03-01E NHX4000 MSX-853 Axis Adjustment Procedure of Z-Axis Zero Return PositionDokumen5 halamanService Manual: SV01-NHX40AX03-01E NHX4000 MSX-853 Axis Adjustment Procedure of Z-Axis Zero Return Positionmahdi elmay100% (3)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Corrosion Fatigue Phenomena Learned From Failure AnalysisDokumen10 halamanCorrosion Fatigue Phenomena Learned From Failure AnalysisDavid Jose Velandia MunozBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- QP December 2006Dokumen10 halamanQP December 2006Simon ChawingaBelum ada peringkat

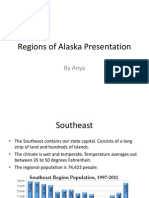

- Regions of Alaska PresentationDokumen15 halamanRegions of Alaska Presentationapi-260890532Belum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Unit 16 - Monitoring, Review and Audit by Allan WatsonDokumen29 halamanUnit 16 - Monitoring, Review and Audit by Allan WatsonLuqman OsmanBelum ada peringkat

- Mcom Sem 4 Project FinalDokumen70 halamanMcom Sem 4 Project Finallaxmi iyer75% (4)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Oracle Forms & Reports 12.2.1.2.0 - Create and Configure On The OEL 7Dokumen50 halamanOracle Forms & Reports 12.2.1.2.0 - Create and Configure On The OEL 7Mario Vilchis Esquivel100% (1)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Talking Art As The Spirit Moves UsDokumen7 halamanTalking Art As The Spirit Moves UsUCLA_SPARCBelum ada peringkat

- WL-80 FTCDokumen5 halamanWL-80 FTCMr.Thawatchai hansuwanBelum ada peringkat

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Lesson PlanDokumen2 halamanLesson Plannicole rigonBelum ada peringkat

- 13 Adsorption of Congo Red A Basic Dye by ZnFe-CO3Dokumen10 halaman13 Adsorption of Congo Red A Basic Dye by ZnFe-CO3Jorellie PetalverBelum ada peringkat

- 2009 2011 DS Manual - Club Car (001-061)Dokumen61 halaman2009 2011 DS Manual - Club Car (001-061)misaBelum ada peringkat

- DarcDokumen9 halamanDarcJunior BermudezBelum ada peringkat

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- AlpaGasus: How To Train LLMs With Less Data and More AccuracyDokumen6 halamanAlpaGasus: How To Train LLMs With Less Data and More AccuracyMy SocialBelum ada peringkat

- Elements of ArtDokumen1 halamanElements of Artsamson8cindy8louBelum ada peringkat

- How Drugs Work - Basic Pharmacology For Healthcare ProfessionalsDokumen19 halamanHow Drugs Work - Basic Pharmacology For Healthcare ProfessionalsSebastián Pérez GuerraBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 8 Data Collection InstrumentsDokumen19 halamanChapter 8 Data Collection InstrumentssharmabastolaBelum ada peringkat

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Rule 113 114Dokumen7 halamanRule 113 114Shaila GonzalesBelum ada peringkat

- Comparitive Study ICICI & HDFCDokumen22 halamanComparitive Study ICICI & HDFCshah faisal100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)