Mohd Noh - Int Journal of Nusantara Islam

Diunggah oleh

Alan MathewHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Mohd Noh - Int Journal of Nusantara Islam

Diunggah oleh

Alan MathewHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

The Roles of Malays in the Process of Islamization of the Malay World: A Preliminary Study

The Roles of Malays in the Process of Islamization of the Malay World:

A Preliminary Study

Mohd Noh Abdul Jalil1

1Department Usuluddin and Comparative Religion, International Islamic University Malaysia

Email: mohdnoh@iium.edu.my

Accepted Article: 20 August 2014

Published Article: 20 April 2015

Abstract

This paper will deal with problem concerning issues and theories of Islamization of the Malay

world, with particular reference to the absence of the important element in these theories, which is

the role and contribution of the Malay towards the process of Islamization in this region.

Furthermore, there will be a discussion of the problem of generalization of existing theories, as

well as issues concerning the limited amount of local evidence to support these theories. Sources

for this analysis will be taken from studies of inscriptions, as well as early Malay text, religious and

non-religious texts. Comparison between the existing theories and direct and indirect evidence

from sources will be used to ebolerate this matter. The ability of the early Malays to adopt and

adapt foreign practices suggest that they also contributed to the entire process of Islamization of

the Malay world one way or another.

Keywords: Islamization, Malays, Role, Contribution

A. INTRODUCTION

The formulation of comprehensive theories related of the coming of Islam to the Malay world has

attracted many scholars to come out with with arguments and counter arguments to validate various

approaches and interpretation. The generally peaceful penetration of Islam into the Malay world

which is not questioned, was in contrast to other areas such as the indian subcontinent, and the fact

that the gradual change of the religious adherence among the Malays at that time from hindu-

buddhist religions to Islam invited more interesting and yet unanswered questions to be explored.

Broadly speaking, one can discern two major approaches by their differing emphasis on faith or

facts. The former seems to be upholding a faith-based theory which requires less factual evidence to

support their claims.

B. METHODS

This article is a discussion on the existing theories of Islamization in the Malay world, as well as

issues concerning the limited amount of local evidence to support these theories. Sources for this

analysis will be taken from studies on texts, including the early Malay texts, either religious or non-

religious. Comparison between the existing theories and direct and indirect evidence from sources

will be used to ebolerate this matter.

International Journal of Nusantara Islam, Vol.02 No.02 2014; (1120) 11

The Roles of Malays in the Process of Islamization of the Malay World: A Preliminary Study

C. RESULT AND DISCUSSION

1. Theories of The Islamization of the Malay World

The best example of a faith-driven approach is the resolution which was formulated by Indonesian

Muslims, scholars and theologians at a seminar held in 1963 in Medan (North Sumatra), and

reaffirmed in Aceh in 1978 (Kratz, 1988). Among others, the declarations made in this seminar are

that Islam entered Indonesia for the first time in the 1st century of hijrah (7 8 C.E.) and came

directly from Arabia (Kratz, 1988). While there is perhaps evidence to support the claim that there

was a community of Muslims in the Malay world as early as the 1st century of hijrah (Groeneveldt,

1880), no conclusive hard evidence is available up to now to support this argument. A different

approach from a Muslim scholar in the Malay world is that of Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas.

Although he adopted a different approach in analizyng the issues of the coming of Islam to Malay

world from those of the above faith-driven theoreticians, he came to a similiar conclusion, namely

that Islam was brought to the Malay world from Arabia. He than added that is was brought largely,

by the sayids, mainly from Hadramawt (Al-Attas, 1969).

Others, mainly western scholars on Islam in the Malay world, advanced with more caitious

theories, restricted to search for and interpretation of hard evidence, limited and inconclusive as

much as of it is, such as tombstone or the adherence of the Malays to a certain school of Islamic

Jurisprudence (fiqh). Given the scarcity of hard evidence, various others theories relating to the

provenance of Islam in the Malay world have emerged, which in the end have to be taken with

equal caution, due to their tendency to overstate the general relevance of scattered evidences. we

shall be discussing all of these theories in this article.

As we have mentioned before, the debate on the theories of Islamization of the Malay world

evolves around three pertinent questions, namely when Islam was brought to the Malay world, by

whom and how. Despite many attempts by scholars to answer those questions, this issues is yet

to find conclusive answers. This is due to the absence of hard and convicing evidence to give

overall support to any of the theories put forward to date. One of the reasons could be because

some of the earliest written materials had been annihilated by the effect of tropical climate change

throughout these long periods (Wheatley, 1961). This could be true if we look at the existence of

the oldest known Malay manuscript, which was written in the second half of 14th century C.E. in

PalappoNusantaric script (Kozok, 2004). In the other words, no other textual evidence that has

so far survived was written before that period in the Malay world. This could include data on the

issues of Islamization of the Malay world.

However, before going into the discussion of the existing theories it is important to state the fact

that clearly, these theories did not include any suggestion of the possible roles and contributions of

the Malays themselves to the entire process of Islamization of their own land. This seems strange

and needs to be looked at further.

There is evidence to show that the Malays, as coastal dwellers and seamen, were travelling, and

probably also live outside the archipelago. Firstly, there is evidence written in the travalogue of Ibn

Batuta during his travel to Asia to Africa between 1325 C.E. 1354 C.E. Ibn Batuta documented in

his book his encounter with the Malays in Ormuz at the Malabar coast and also even as far far as

East Africa during his travels to these regions. Secondly, there is evidence as to the presence of

the Malays in Gujarat. Nuruddin al-Raniri was recorded as having studied the Malay language

during his early days in his hometown in Gujarat besides studying Islam, thanks to presence of a

significant number of Malays in Gujarat at that time (Battuta, 1983).

12 International Journal of Nusantara Islam, Vol.02 No.02 2014; (1120)

The Roles of Malays in the Process of Islamization of the Malay World: A Preliminary Study

Thus, the presence of these Malays in Malabar regions, as well as Gujarat, which were recorded

to have accepted Islam earlier than the Malay world and might be one of the places of origin of

Islam in the Malay world, suggests that these Malays were Muslims as well. As seamen or

probably merchants themselves, these Malays could possibly be involved together with other

Muslims preachers, in bringing Islam to their homeland. Other than five pillars of Islam, there is no

other important duty for a Muslims but to disseminate the message of Islam to those who are

closest to themselves, as this is one of the fundamental teachings of Islam.

To continue with the discussions of the existing theories of Islamization of the Malay world, the

earliest possible evidence on the presence of Muslims in the Malay world was documented by

Chinese records in 674 C.E (Iskandar, 1966). It has been noted that this settlement headed by a

chief, said to be an Arab, was found in East Sumatra. Another evidence on the early presence of

Muslims in the archipelago is a massive emigration of Muslims traders and merchant said to be

the Arabs and the Persians from Kanfu (Canton) to Kalah (Kedah) in 877 C.E. Al-Masudi recorded

that this large scale of emigration was due to the decision made by the Chinese emperor at that

time, Hi-Tsung to close the port in Canton to all foreign vessels, and to destroy foreign colonies in

that region in order to contain local rebellion and prevent the rebels from getting assistance from

outside the country (Groeneveldt, 1880).

Only after the 9th century C.E. more evidence on the presence of the Muslims in the archipelago

started to emerge in a different form. This is in the form of archacological evidence. One of the

earliest tombstones belongs to a Muslim woman under the name of Fatima bint Maimun was

found in Leran, Gresik, near Surabaya in East Java. The stone bears the date 1082 C.E (Al-Attas,

1969). Another tombstone was found in Samudra Pasai dated after conversion in 1297 C.E. This

grave stone commemorates the founder of that state, Malik al-Saleh. A stone inscription written in

arabic script, and constituting certain Islamics laws, was found in Kuala Berang, Trengganu on the

eastern coast of the Malaysian peninsula (Fatimi, 1963). However, the date written on this stone is

incomplete. As such, scholars have to use the incomplete information available on this stone to

estabilish when it was written. Some scholars have concluded that this stone was written either in

1303. C.E. or 1386 C.E (Fatimi, 1963). Blagden is more inclined towards the latest possible date,

which is on 2 February 1386 C.E (Peterson & C.O. Blagden, 1924)., while al- Attas ascertains that

this stone was written in 1303 C.E (Al-Attas, 1970). Thus, any interpretation given by these

scholars has to remain in doubt as the evidence is incloncusive.

The visits of foreign travelers, Marco Polo in 1292 C.E. to Perlak in North Sumatra (Yule, 1929),

Ibn Batuta in 1345 C.E. to Pasai (Battuta, 1983), and also Tome Piress visit to Perlak as recorded

in his book Suma Oriental in 1515 C.E (Cortesao, 1944) confirm that these areas were alredy

penetrated by Islam. It may be concluded that Islam was present in the Malay world as early as

the 7th century C.E. However, the accelerating mode of the Islamization process began only by the

end of the 13th century C.E. onwards, especially after the establishment of the first Muslim

kingdom in Samudra Pasai, according to the evidence we have today.

The discussion concerning the date of arrival of Islam in the Malay world did not attract much

debate from scholars, compared to the issues of the origin of Islam in the archipelago. Scholars

have shown their great interest in analyzing the question of the provenance of Islam, and put

forward their arguments by relying on limited archaeological and circumstantial evidence, as well

as local traditions, at hand.

Generally, these views are divided into three, namely that Islam came to the Malay world either

from the Indian subcontinent, or from the Arabian peninsula or from China. Beside these three

International Journal of Nusantara Islam, Vol.02 No.02 2014; (1120) 13

The Roles of Malays in the Process of Islamization of the Malay World: A Preliminary Study

main origins of Islam in the Malay world, there is also another theory which suggest that Islam

came from Egypt, but it has not gained much attention from scholars, probably because of the

weak nature of the evidence put forward by its proponents. Scholars came out with different views

after analyzing one or more of the following factors; the archaeological evidence, the adherence of

the Malays to certain school of Islamic Jurisprudence, and also based on their analysis of the local

customs and traditions, as well as relying on the history of trade and early relationship of the

Malays with foreigners.

It is interesting, and yet strange, to note that none of these theories highlight the roles and

contributions of the Malays themselves in the entire process of Islamization of their own land.

Nevertheless, before coming up with some possible suggestions as to the roles and contributions

of the Malays in this matter, it is worth reviewing the existing theories of the origin of Islam in the

Malay world.

The Gujaratis theory is possibly the earliest theory put forward by scholars on question of the

origin of Islam in the Malay world. This theory relies on the presence of archaeological evidence of

early Muslims tombstones found throughout the Malay world. Scholars such as Pijnappel quoted

by Drewes (Drewes, 1968) and Moquette quoted by Azra (1992) proposed that Islam be brought

to the Malay world by Muslims from Gujarat, the northen part of the Indian subcontinent. This

conclusion was made after making camparison between tombstones found in Pasai and Gresik

dated 1428 C.E. and 1219 C.E. respectively, and those found at Cambay, Gujarat at that time and

the result was they were identical. This similarity prompted scholars to suggest that Gujarat could

possibly be the place of origin of Islam in the Malay world.

This view is, however refuted by Marisson and later by Fatimi. Marisson argues that Gujarat

cannot be the provenance of Islam, due to the fact that is was not only until 1928 C.E. that Gujarat

was under the rule of Muslims ruler (Marrison, 1951). Thus, according to him, it was not possible

for Gujarat to have been an important base for Muslim missionaries to spread Islam to other

areas. Marisson compared the school of law adhered to by the people of Gujarat and Samudra

Pasai, which differed from one to the other. the former adopted either the Sunni Hanafiyyah

School of Islamic Jurisprudence or shiism, while the latter adhered to the Sunni Shafiyyah School

of Islamic Jurisprudence. Thus, he concluded that Muslims from southern India were actually

responsible for bringing Islam to the Malay world, since there were similarities in terms of the

school of law, as well as certain local traditions, which were portrayed in the Malay hikayats with

the practice of people from south India at that time (Marrison, 1951).

Fatimi, on the other hand, contended that the tombstone found in Pasai was not identical with

Gujarat but Bengal (Fatimi, 1963). He immediately concluded that Muslims from Bengal could be

responsible for bringing Islam to the Malay world, based on available archaeological evidence.

Fatimi also contested Marrisons view on the adherence of the Gujaratis as belonging to the

Hanafi School of Islamic Jurisprudence. He maintained that most of the areas in Gujarat were as

much Shafii Muslim as Coromandel and Malabar. This is evident with the background of one of the

most popular Gujarati ulema (scholar) in the Malay world, Nuruddin al-Raniri, who proudly

mentioned hid adherence to the Shafii school in his works (Fatimi, 1963).

Scholars who inclined towards the view of the South Asian origin came up with other supporting

evidence as well. For example, van Ronkel (1922) and Snouck Hurgronje cited in Drewes (1968),

and also Johns (1961) emphasized other circumstantial evidence such as the character of

mysticism, the form of many Arabic loan words. The roles of Deccan Muslims as intermediaries in

trade between the Arabian peninsula and the Malay world, who amongs them were the Sufis to

14 International Journal of Nusantara Islam, Vol.02 No.02 2014; (1120)

The Roles of Malays in the Process of Islamization of the Malay World: A Preliminary Study

support this theory. Therefore, Fatimis theory of the Bengal origin would be unnaceptable if

evaluated through this method, since the Bengaliss Muslims were known as adherents to the

Hanafi School of Islamic Jurisprudence, and not to the Shafiis.

The discussions on the adherence of these early propagators of Islam to certain schools of Islamic

jurisprudence brought the discussion to an origin in Arabia. For example, Niemman and Hollander,

as cited in Hooker (1983), relied on the adherence to the Shafii school of Islamic jurisprudence

among the population of the southern part of Arabian Peninsula as evidence to support this view.

However, the main proponent for this theories Syed Muhammad Naguib al-Attas. We will be

focusing more on his theory of the Islamization of the Malay world later. Since he came up with a

theory which not only deals with the questions of the provenence of Islam, but also of the

Islamization of the Malay world as dynamic process. Furthermore, he is the only scholar from the

Malay world who has come out with a comprehensive theory of Islamization in the Malay world.

The debates of the origin of Islam in the Malay world have been given a new direction, away from

ethnocentric theories to a boarder and wider perspective, focusing on the nature of Islam itself.

Johns has developed an argument regarding the role of the Sufis in propagating and

disseminating Islam to the entire Malay world, as the earliest group of Muslim preachers to do so

(Johns, 1961). They might be the Sufis from the Middle East, Indian subcontinent or from any

other part of Muslim world who had taken up this responsibility to spread Islam to the entire world.

They came together with merchants on ships, with a mission to spread the religion to the local

people. Interestingly, the ability of these Sufis to understand the local traditions made their efforts

fruitful in bringing more people to Islam. They were able to convince the local people to adopt the

Islamic teachings within the context of their existing traditional cultures dan practices. Johns

theory concludes that it was the Sufis who were responsible for the spread of Islam to the Malay

world.

Al-Attass theory of Islamization of the Malay world goes further in highlighting the dynamics of the

entire process of Islamization. While older scholars were focusing on what he termed external

characteristics of Islam in analyzing the entire process of Islamization of the archipelago, he

concentrates on the internal characteristics of Islam as a religion in which according to him only

Muslims understood best (Al-Attas, 1969). He started his theoretical propositions by saying that

the notion that Islam came to the Malay world from India and was conveyed by Indians as cannot

be accepted (Al-Attas, 1969). According to him, the suggetions that Islam came to the Malay

world from India have been formulated to fit into the autochthonous theory and have been based

upon observation of merely the external characteristics of Islam as revealed according to trade

patterns, according to past experiences with Hinduism and Buddhism (Al-Attas, 1969).

Furthermore, according to al-Attas, roughly from the 17th century C.E. onwards, there was no

evidence of a single South Asian author or work of South Asian origin found, and if there was any,

as claimed by Western scholars they turned out to be Arab or Persian origins. Even what was

most described as Persian has, in fact, been Arabian (Al-Attas, 1969). He then moved to say that

the early missionaries to the Malay world were Arab or Arab Persian, based on their name and

titles (Al-Attas, 1969). He admitted that some of these Arab missionaries came to the Malay world

via India or China, but there were also those who came directly from Arabia (Al-Attas, 1969). He

concluded his theory of origin of Islam in the Malay world from Arabia by emphasizing that most

of the early missionaries were sayyids, many from Hadramawt, and the later missionaries of Islam

in the archipelago were the Malays themselves and the Javanese and other indigenous people

(Al-Attas, 1969). Obviously, in his theory of origin of Islam in the Malay world the people from

South Asia did not have a significant contribution to make to the entire process of Islamization of

International Journal of Nusantara Islam, Vol.02 No.02 2014; (1120) 15

The Roles of Malays in the Process of Islamization of the Malay World: A Preliminary Study

the Malay world. According to him, the subject of the provenance of Islam in the Malay world has

been unduly magnified with the role of India and the people from South Asia (Al-Attas, 1969).

Returning to al-Attas theory on the inner process of Islamization of the Malay world, he has divided

this development into three phases, known as (i) the conversion of the body; (ii) the conversion of

the spirit; and (iii) the period of continuation of the conversion of the body and the consummation

of the conversion of the spirit (Al-Attas, 1969). The first phase, which occured approximately from

the 13th to 15th centuries C.E., the Malays were introduced and converted to Islam by the strength

of faith, and not necessarily accompanied by an understanding of the rational and intellectual

implications such conversion entailed (Al-Attas, 1969). He continued by saying that fundamental

concepts connected with the central Islamic concept of Unity of God (tawhid) were still vague in

the minds of the converts, the old concepts overlapping and clouding or confusing the new ones

(Al-Attas, 1969). In other words, al-Attas suggested that during these early periods of conversion

to Islam, the Malays were simply converted to Islam without really understanding what Islam was

all about. The Malays became Muslims, and were instructed to follow the religius laws (shariah) by

the ulama i.e. the Arabs at that time. Islam has yet not penetrated the inner realm of the Malay at

this stage.

It was only during the second phase of Islamization between the 15-18th centuries C.E. that the

Malays started to understand the inner meaning of Islam. According to al-Attas, Sufism and Sufi

writings as well as the writings of the Mutakallimun played a dominant role at this stage in order to

convert the spirit of the Malays (Al-Attas, 1969). The Malays began to understand the inner

meaning of Islam, with the help of philosophical mysticism and metaphysics (tasawuf), and other

rational and intellectual elements such as rational theology (kalam) (Al-Attas, 1969). Al-Attas

termed the Malays before Islam as living in the world of mythology whilst when they became

Muslims they were now living in the world of intelligence, reason and order (Al-Attas, 1969). Al-

Attas also stressed that Sufi metaphysics did not come to harmonize Islam with traditional beliefs

grounded in Hindu-Buddhist beliefs and other authochthonous traditions as it was generally held

even by some ulamas, but it came to clarify the difference between Islam and what the Malays

had known in the past (Al-Attas, 1969).

As for the third phase of Islamization, which started from the 18th century C.E. and continued until

today, al-Attas suggested that the Malays still continue the process of the first and the second

phase i.e. the process of understanding and internalizing Islam as their new religions (Al-Attas,

1969). During this phase, the Malays faced cultural influences coming of the West. According to

al-Attas, such influences were in fact laid earlier by Islam (Al-Attas, 1969).

2. Analysis

Several observations can be made. The hotly-debated issue on this matter among scholars

concerns the provenance of Islam, as well as the carrier of Islam to the Malay world. Based on

what we have highlighted before, theoreticians came from two main groups, based on the

approach they were using to prove their cases.

The first group, the fact-based theorecitians, came to a conclusion regarding the issue of the

provenance of Islam in the Malay world based on evidence gathered and interpreted from

archeological and circumstantial evidence such as tombstones as well as the school of Islamic

jurisprudence adhered to by local peoples found in the Malay world at that time. In general, they

linked the provenance of Islam to the Indian subcontinent. However, they were also divided in

terms of the exact location of the subcontinent either Gujarat, South India or Bengal. On the other

16 International Journal of Nusantara Islam, Vol.02 No.02 2014; (1120)

The Roles of Malays in the Process of Islamization of the Malay World: A Preliminary Study

hand, the South Arabian origin theory was only supported by the dominance of the Shafiis school

of Islamic jurisprudence adhered to by the peoples of the Malay world, which can also be found in

the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula. There are also views that the origins of Islam in the

Malay world are to be found in China and Egypt. Although the proponents of these views claim to

offer evidence for their theories, the nature of their evidence presented is puzzling and weak.

In order to avoid the complexities in substantiating such claims with hard and conclusive evidence,

another theory was presented. This time, it eliminates the linking of the issue of provenance of

Islam in the Malay world to any particular region or race, but goes beyond this by saying that it

was the Sufis who were responsible in bringing Islam there. These Sufis could be from all parts of

the Muslim world.

The second group, the faith-based theoreticians concluded that Islam was brought to the Malay

world from Arabia. However, they did not offer any real evidence. Al-Attas, who is also of the view

that Islam in the Malay world was brought directly from south Arabia, added further that it was a

particular group the sayids who were responsible for this effort, without offering evidence to this

either.

Furthermore, Al-Attas, as the only Muslim scholar who came out with views on how Islam was

spread and received by the local peoples in three phrases, represents new insights and interesting

to be discussed in the context of this study. His sole emphasis on the contribution of foreign

Muslims i.e. the Arabs in bringing and disseminating Islam in the Malay world denies the

contributions of local people in the entire process and especially at its early stages. Based on the

evidence mentioned in the travelogues of Ibn Battuta on the presence of the Malays in Ormuz at

the Malabar Coast and also even as far away as East Africa during his travels to these regions

(Battuta, 1983), as well as the experience of Nuruddin al-Raniri who studied the Malay language

with the Malays in Gujarat (Iskandar, 1966), there could be the possibility that these Malays were

also involved in the process of bringing Islam to their homeland, and assisting foreign ulama in

disseminating its teachings to the local peoples. Feener has also found evidence of elements of

Malay Muslim tradition which had influenced diverse aspects of culture in southern Arabia and

Wadi Hadramawt in particular as well as Arabic texts dating as far back as the fourteenth century

on the exchanges between scholars of the two regions (Feener, 2009).

Beside, the discussions on the existing theories of Islamization of the Malay world, it is also

important to highlight a study made by Russel Jones on the conversion of myths existing in the

archipelago (Jones, 1979). These views could be used to understand the entire process of

Islamization of the Malay world better. In his studies, Jones highlights that no identifiable author

can be found for such myths, and that they were created by Muslims scribes under Muslim

patronage, perhaps long after Islam had been accepted as a state religion (Jones, 1979). He

found a kind of uniformity about these myths which was characterized by miracles and other

striking features such as dream or prediction. These, according to Jones, would have helped to

soften the first impact of the change and to reconcile contradictions during the early transitional

period (Jones, 1979).

The above conclusion made by Jones after presenting various example of Islamization of the

Malay world does agree with Al-Attas top to bottom approach to the Islamization of the Malay

world. In other words, these myths were created by the courts for a specific purpose which is that

Islam was received by the rules directly from the descendants of the Prophet from Arabia. As

such, this notion will help to convince people to accept Islam brought to them by their rulers, as

this religion was perceived to be the most authentic form of Islam, because it was transmitted by

International Journal of Nusantara Islam, Vol.02 No.02 2014; (1120) 17

The Roles of Malays in the Process of Islamization of the Malay World: A Preliminary Study

the people who received it directly from the Prophet. Not only that, by doing so, the people would

indirectly accept the legitimacy of the ruler, as it was in the past, because Islam also recognizes

the authority of Muslim rulers as third in hierarchy after God and His Prophet, whom Muslims

should obey as long as they rule in accordance with the teachings of Islam. Such a notion of a top

to bottom approach of Islamization is also in line with the analysis made by Azra on what he

termed local histories, such as in Hikayat Raja-Raja Pasai, Sejarah Melayu, Hikayat Merong

Mahawangsa as well as the tarsilahs of the Muslim rulers of the Sulu Sultanante in the Philippines

(Azra, 2006). He concludes his analysis by saying there are four main points conveyed by such

local histories. First, Islam in the archipelago was brought directly from Arabia; second, it was

introduced by professional teachers or propagators ; third, the first converts were the rulers; and

fourth, the most of these professional preachers came to the archipelago in the twelfth and

thirteenth centuries (Azra, 2006).

Riddell, in his studies on Islam and the Malay Indonesian Worl, also put forward interesting findings

relating to the dynamics of Islamization in the Malay world from the 13th century C.E. up to the end of the

last century. His studies, which mainly concentrated on the developmentof ideas by Malay Islamics

writers, throughout these centuries, concluded that these ideas were originating from outside the Malay

world (Riddell, 2001). Interestingly, according to him this did not merely take form of borrowing and

imitation (Riddell, 2001). In other words, although ulama in the Malay world depended on foreign ideas

they did not simply take them as they were, without making necessary changes to suit the local context.

These ulama according to Riddell have been impressed by contextualizing it to Malay circumstances,

producing dynamics new result (Riddell, 2001).

He than gave an example of the ability of local ulamas to contextualize foreign ideas to match

them to local needs. This is related to the ancient debates in the Middle East on the relevation-

versus-reason between the more literalist group, the al-hadith, againts the approach adopted by

the Mutazilite (Riddell, 2001), the rationalist whom relies on reason instead of relevation in order

to understand theological issues in Islam such as creation, the world, and the nature of God

(Riddell, 2001). According to Riddell, in the Malay world the reverse order was the case (Riddell,

2001). He then continued by saying that the battle between speculative Sufis and the Sharia-

minded needed first to be resolved in the early centuries, and only then did the reason-versus-

revelation debate assume priority during the 20 century when modernistsand traditionalist came

face to face on centre stage (Riddell, 2001). These unique developments, according to Riddell,

show that not only the Malay Muslim in the Malay world owes much to other parts of Muslim

worlds, but they themselves also made a substantial creative contribution to the mosaic of world

Islam (Riddell, 2001). Unlike Jones, Riddells studies focus more on the ways Islam was received

by the Malays. His findings seem to be in line with what we have indicated before, relating to the

characteristics of the Malays as an advanced community, who are able to think for themselves for

their own benefits. Riddell has shown that these Malays were able to adopt and adapt foreign

influence to suit their own needs and interest.

D. CONCLUSION

The above discussions highlight one important finding which is the strong possibility of the

contributions of the early Malays in the process of Islamization of the Malay archipelago. The

abilities of these Malays to adopt and adapt foreign influences to suit their own needs and interest

rejected the views that they were merely accepted anything introduced to them from outside the

Malay world blindly. Thus, it would be interesting that the research on this issue is further

expanded to find more evidence on the contributions of the early Malay to the entire process of

Islamization of their own region.

18 International Journal of Nusantara Islam, Vol.02 No.02 2014; (1120)

The Roles of Malays in the Process of Islamization of the Malay World: A Preliminary Study

References

Al-Attas, S. M. N. (1969). Preliminary Statement on a General Theory of the Islamization of the

Malay-Indonesian Archipelago, Kuala Lumpur. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka.

Al-Attas, S. M. N. (1970). The Correct Date of the Trengganu Inscription: Friday, 4 Rajab, 702

A.H./Friday, 22 February, 1303 A.C. Kuala Lumpur: Muzium Negara.

Azra, A. (1992). The Transmission of Islamic Reformism to Indonesia: Networks of Middle Eastern

and Malay Indonesian Ulama in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. USA:

Columbia University.

Azra, A. (2006). Islam in the Indonesian World: An Account of Institutional Formation. Bandung:

Mizan Pustaka.

Battuta, I. (1983). Travels in Asia and Africa 1325-1354. (G. H.A.R., Trans.). London: Darf.

Cortesao, A. (1944). The SumaOriental of Tome Pires and The Book of Francisco Rodrigues.

London: The Hakluyt Society.

Drewes, G. W. J. (1968). New Light on the Coming of Islam to Indonesia. BKI, 124, 439440.

Fatimi, S. Q. (1963). Islam Comes to Malaysia. Singapore: MSRI.

Feener, R. M. (Ed.). (2009). Islamic Connections: Muslims Societies in South and Southeast Asia.

Singapore: ISEAS.

Groeneveldt, W. P. (1880). Notes on the Malay World and Malacca Compiled from Chinese

Sources. VBG, 39, 1314.

Hooker, M. B. (Ed.). (1983). Islam in South-East Asia. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Iskandar. (1966). Teuku, Nurud-din ar-Raniri Bustanus-Salatin. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa

dan Pustaka.

Johns, A. H. (1961). Sufism as a Category in Indonesian Literature and History. JSEAH, 2(2), 10

23.

Jones, R. (1979). Then Conversion Myths from Indonesia. In N. Levtzion (Ed.), Conversion to

Islam. London, New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers Inc.

Kozok, U. (2004). The Tanjung Tanah Code of Law: The Oldest Extant Malay Manuscript.

Cambridge: St Catharines College and University Press.

Kratz, E. U. (1988). A Bibliography of Indonesian Literature in Journals: Drama, Prose and Poetry.

Yogyakarta: Gadjah Madha University Press.

Marrison, G. E. (1951). The Coming of Islam to the East Indies. JMBRAS, 24(1), 32.

International Journal of Nusantara Islam, Vol.02 No.02 2014; (1120) 19

The Roles of Malays in the Process of Islamization of the Malay World: A Preliminary Study

Peterson, H. S., & C.O. Blagden. (1924). An Early Malay Inscription from 14th century

Terengganu. Journ. Mal. Br.R.A.S., 2, 258263.

Riddell, P. (2001). Islam and the Malay-Indonesian World: Transmission and Responses.

Singapore: Horizon Books Pte. Ltd.

Van Ronkel, P. S. (1922). A Tamil Malay Manuscript. JMBRAS, 85, 29.

Wheatley, P. (1961). The Golden Khersonese: Studies in the Historical Geography of the Malay

Peninsula before A.D. 1500. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Yule, S. H. (1929). The Book of Ser Marco Polo. London: John Murray.

20 International Journal of Nusantara Islam, Vol.02 No.02 2014; (1120)

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Church House of God Fr. Tadros MalatyDokumen354 halamanThe Church House of God Fr. Tadros MalatyIsa Almisry100% (3)

- Liberal Temper in Greek Politics - BWDokumen452 halamanLiberal Temper in Greek Politics - BWs78yl932qBelum ada peringkat

- The Truth About Satanic CultsDokumen7 halamanThe Truth About Satanic CultsJoe Jr. KEP100% (1)

- OsainDokumen5 halamanOsainGilbertoGarcésBelum ada peringkat

- Reformation of Islamic Thought PDFDokumen117 halamanReformation of Islamic Thought PDFZulqarnainHaiderMengalBelum ada peringkat

- NIEHOFF, Maren R. Homer and The Bible in The Eyes of Ancient Interpreters PDFDokumen383 halamanNIEHOFF, Maren R. Homer and The Bible in The Eyes of Ancient Interpreters PDFluyduarte100% (2)

- Nomos1 Catalogue WebDokumen148 halamanNomos1 Catalogue WebАлександр Васьковский100% (2)

- Pathways To An Inner IslamDokumen221 halamanPathways To An Inner Islamzoran-888100% (2)

- Timothy Leary - Think For Yourself, Question AuthorityDokumen99 halamanTimothy Leary - Think For Yourself, Question AuthorityEllie Nale100% (4)

- Why Does God Allow Evil and Injustice?Dokumen9 halamanWhy Does God Allow Evil and Injustice?Lola RicheyBelum ada peringkat

- Impact of Sufism in Islamization of ArchipelagoDokumen31 halamanImpact of Sufism in Islamization of ArchipelagoZoehelmy HusenBelum ada peringkat

- Novena To The Holy SpiritDokumen7 halamanNovena To The Holy SpiritmoseschelengaBelum ada peringkat

- Novena ST Padre PioDokumen2 halamanNovena ST Padre PioPadreRon AlquisadaBelum ada peringkat

- Sufism in Medieval Muslim SocietiesDokumen12 halamanSufism in Medieval Muslim SocietiesaydogankBelum ada peringkat

- Diogenes of BabylonDokumen22 halamanDiogenes of BabylonXristina BartzouBelum ada peringkat

- Payment Slip: Summary of Charges / Payments Current Bill AnalysisDokumen5 halamanPayment Slip: Summary of Charges / Payments Current Bill AnalysisAlan MathewBelum ada peringkat

- Debating Gender A Study On Status of Wom PDFDokumen65 halamanDebating Gender A Study On Status of Wom PDFJ. Carlos SegundoBelum ada peringkat

- Kryon - Perceptions of MasterhoodDokumen36 halamanKryon - Perceptions of Masterhoodgreenstar100% (4)

- Nose Profile Morphology and Accuracy Study of Nose Profile Estimation Method in Scottish Subadult and Indonesian Adult PopulationsDokumen9 halamanNose Profile Morphology and Accuracy Study of Nose Profile Estimation Method in Scottish Subadult and Indonesian Adult PopulationsAlan MathewBelum ada peringkat

- The End of Innocence?: Indonesian Islam and the Temptations of RadicalismDari EverandThe End of Innocence?: Indonesian Islam and the Temptations of RadicalismBelum ada peringkat

- Maenads and MenDokumen22 halamanMaenads and MenAllanMoraes100% (1)

- Muslim Philosophy and The Sciences - Alnoor Dhanani - Muslim Almanac - 1996Dokumen19 halamanMuslim Philosophy and The Sciences - Alnoor Dhanani - Muslim Almanac - 1996Yunis IshanzadehBelum ada peringkat

- Grigg, 1987Dokumen8 halamanGrigg, 1987vladbedrosBelum ada peringkat

- Watt's View On Muslim Heritage in The Study of Other Religions A Critical AnalysisDokumen22 halamanWatt's View On Muslim Heritage in The Study of Other Religions A Critical AnalysiswmfazrulBelum ada peringkat

- An Essay Outline On "Tabligh Movement in South East Asia"Dokumen12 halamanAn Essay Outline On "Tabligh Movement in South East Asia"Khalid Noor MohammedBelum ada peringkat

- Islam Religion Research PaperDokumen8 halamanIslam Religion Research Paperjioeuqznd100% (1)

- Conversion To Islam in The Indian Milieu: A Reconsideration of Dawah and Conversion Process During The Pre Mughal PeriodDokumen18 halamanConversion To Islam in The Indian Milieu: A Reconsideration of Dawah and Conversion Process During The Pre Mughal PeriodArchisha DainwalBelum ada peringkat

- Islam Research Paper TopicsDokumen4 halamanIslam Research Paper Topicsafmchbghz100% (1)

- The Tarlqat Al - 'Alawiyyah and The Emergence of The Shi'I School in Indonesia and MalaysiaDokumen17 halamanThe Tarlqat Al - 'Alawiyyah and The Emergence of The Shi'I School in Indonesia and Malaysiaaimi anisBelum ada peringkat

- Pre-Modern Islam: The Practice of Tasawwuf and Its Influence in The Spiritual and Literary CulturesDokumen5 halamanPre-Modern Islam: The Practice of Tasawwuf and Its Influence in The Spiritual and Literary CulturesIJELS Research JournalBelum ada peringkat

- Islamic - Reform - The - Family - and - Knowledge - Sejarah Haji Di MalakaDokumen24 halamanIslamic - Reform - The - Family - and - Knowledge - Sejarah Haji Di MalakaidrusgaramBelum ada peringkat

- 2011 - (Ismail Fajrie Alatas) Becoming Indonesian The Bā Alawī in The Interstices of The NationDokumen31 halaman2011 - (Ismail Fajrie Alatas) Becoming Indonesian The Bā Alawī in The Interstices of The NationEgi Tanadi TaufikBelum ada peringkat

- Kesultanan Nusantara Dan Faham Keagamaan Moderat Di IndonesiaDokumen22 halamanKesultanan Nusantara Dan Faham Keagamaan Moderat Di IndonesiaYosep SinagaBelum ada peringkat

- Abstract: The Discourse On The Process of Islamization inDokumen25 halamanAbstract: The Discourse On The Process of Islamization inashif fuadyBelum ada peringkat

- 752-Article Text-1302-1-10-20230402Dokumen14 halaman752-Article Text-1302-1-10-20230402jojoamrandBelum ada peringkat

- Wocihac2011 Islam EducationDokumen261 halamanWocihac2011 Islam Educationaisyah humairaBelum ada peringkat

- Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya in The "Lands Below The Wind": An Ideological Father of Radicalism or A Popular Sufi Master?Dokumen31 halamanIbn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya in The "Lands Below The Wind": An Ideological Father of Radicalism or A Popular Sufi Master?Achmad KusumahBelum ada peringkat

- A Historical Overview and Initiating Historiography of Islam in The PhilippinesDokumen29 halamanA Historical Overview and Initiating Historiography of Islam in The PhilippinesJanida AlamadaBelum ada peringkat

- 2007 - (Ismail Fajrie Alatas) The Upsurge of Memory in The Case of Haul A Problem of Islamic Historiography in IndonesiaDokumen13 halaman2007 - (Ismail Fajrie Alatas) The Upsurge of Memory in The Case of Haul A Problem of Islamic Historiography in IndonesiaEgi Tanadi TaufikBelum ada peringkat

- His101 ProjectDokumen13 halamanHis101 Projectমোঃ আসাদুজ্জামান শাওনBelum ada peringkat

- Ismail Fajrie AlatasDokumen41 halamanIsmail Fajrie AlatasTaufik Taufani SuhadakBelum ada peringkat

- Kesinambungan Dan Perubahan Dalam KajianDokumen20 halamanKesinambungan Dan Perubahan Dalam KajianJembatan SongakBelum ada peringkat

- Islamism and Social Reform in Kerala, South India: Filippoosella AndcarolineosellaDokumen30 halamanIslamism and Social Reform in Kerala, South India: Filippoosella AndcarolineosellakajkargroupBelum ada peringkat

- Nile Green Making Sense of Sufism' in The Indian Subcontinent: A Survey of TrendsDokumen18 halamanNile Green Making Sense of Sufism' in The Indian Subcontinent: A Survey of TrendsAbrvalg_1100% (1)

- The Survival of Liberal and Progressive PDFDokumen9 halamanThe Survival of Liberal and Progressive PDFDadang SetiawanBelum ada peringkat

- Contemporary Islamic Thought in Indonesian and Malay WorldDokumen39 halamanContemporary Islamic Thought in Indonesian and Malay WorldMehadi SakiBelum ada peringkat

- An Exploration of Naquib Al Attas Theory of Islamic Education As Ta D B As An Indigenous Educational Philosophy PDFDokumen10 halamanAn Exploration of Naquib Al Attas Theory of Islamic Education As Ta D B As An Indigenous Educational Philosophy PDFMahfuj RahmanBelum ada peringkat

- The Genealogy of Muslim Radicalism in Indonesia A Study of The Roots and Characteristics of The Padri MovementDokumen33 halamanThe Genealogy of Muslim Radicalism in Indonesia A Study of The Roots and Characteristics of The Padri MovementIvanciousBelum ada peringkat

- 118-Article Text-427-1-10-20160727Dokumen19 halaman118-Article Text-427-1-10-20160727Ravel FebriantoBelum ada peringkat

- Salafism in Malaysia: Historical Account On Its Emergence and MotivationsDokumen31 halamanSalafism in Malaysia: Historical Account On Its Emergence and Motivationsmuhamad aminBelum ada peringkat

- Tasawwuf - ImpactDokumen16 halamanTasawwuf - ImpactZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-Hadrami100% (1)

- Arab Migrants and Islamization in The Malay World During The Colonial PeriodDokumen17 halamanArab Migrants and Islamization in The Malay World During The Colonial PeriodRama PengembaraBelum ada peringkat

- Evolution - SumarahDokumen240 halamanEvolution - SumarahRosali Mee VaipulyaBelum ada peringkat

- Muslim-Christian Relation in Malaysia A Study On The Inter-Faith Dialogue From Muslim PerspectiveDokumen11 halamanMuslim-Christian Relation in Malaysia A Study On The Inter-Faith Dialogue From Muslim Perspectiveabdulrahman.2014Belum ada peringkat

- Jurnal Mayang Sari (Studi Islam)Dokumen12 halamanJurnal Mayang Sari (Studi Islam)jannatun ainiBelum ada peringkat

- Amber Psychology From Islamic Perspective AmberDokumen22 halamanAmber Psychology From Islamic Perspective AmberWardah KamaludinBelum ada peringkat

- Tradisi Ilmiah Dalam Peradaban Islam Melayu: AbstractDokumen13 halamanTradisi Ilmiah Dalam Peradaban Islam Melayu: AbstractYoga Andi PratamaBelum ada peringkat

- Religions: Between Tradition and Transition: An Islamic Seminary, or Dar Al-Uloom in Modern BritainDokumen14 halamanReligions: Between Tradition and Transition: An Islamic Seminary, or Dar Al-Uloom in Modern BritainKevin MoggBelum ada peringkat

- Topic Islamic Philosophy and Western Philosophy: SemesterDokumen6 halamanTopic Islamic Philosophy and Western Philosophy: SemesterMuhammad NadilBelum ada peringkat

- Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya in The "Lands Below The Wind" - Syamsudin ArifDokumen31 halamanIbn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya in The "Lands Below The Wind" - Syamsudin ArifDimas WichaksonoBelum ada peringkat

- Islam Dan Dialog Antar Kebudayaan (Studi Dinamika Islam Di Dunia Barat) Dedi Wahyudi Dan Rahayu Fitri ASDokumen24 halamanIslam Dan Dialog Antar Kebudayaan (Studi Dinamika Islam Di Dunia Barat) Dedi Wahyudi Dan Rahayu Fitri ASZona NyamanBelum ada peringkat

- Muslim Heritage in Religionswissenschaft: A Preliminary Study On The Purposiveness & The Non-Purposiveness of Muslim ScholarshipDokumen18 halamanMuslim Heritage in Religionswissenschaft: A Preliminary Study On The Purposiveness & The Non-Purposiveness of Muslim ScholarshipAvicena AlbiruniBelum ada peringkat

- Research Paper Topics IslamDokumen4 halamanResearch Paper Topics Islamjwuajdcnd100% (1)

- Final SummaryDokumen29 halamanFinal SummaryMuhammad HareesBelum ada peringkat

- Research Paper IslamDokumen9 halamanResearch Paper Islamfzfgkws3100% (1)

- Jurnal Nadira Dan Patricia, Kelas D Reg 21Dokumen13 halamanJurnal Nadira Dan Patricia, Kelas D Reg 21Nadira PutriBelum ada peringkat

- Contributions of Muslim Scholars To TheDokumen6 halamanContributions of Muslim Scholars To ThefirdousBelum ada peringkat

- Islamic Reform in Malaya: The Contribution of Shaykh Tahir JalaluddinDokumen24 halamanIslamic Reform in Malaya: The Contribution of Shaykh Tahir JalaluddinAsh AngelBelum ada peringkat

- Relevance of Mutazilah Thinking With The Ulama Intellectual MalayDokumen10 halamanRelevance of Mutazilah Thinking With The Ulama Intellectual MalayPikas PikasBelum ada peringkat

- 2 Spread of Islam Source 1Dokumen16 halaman2 Spread of Islam Source 1Rommel PancipaneBelum ada peringkat

- Outreach of Islam: English For Islamic StudiesDokumen10 halamanOutreach of Islam: English For Islamic Studiessherlyy anneBelum ada peringkat

- Islamiat PDFDokumen29 halamanIslamiat PDFHuzaifa AnwarBelum ada peringkat

- Prophetic Approach and Methodology Towards The Cultural and Civilizational Impact On EducationDokumen11 halamanProphetic Approach and Methodology Towards The Cultural and Civilizational Impact On EducationFirst LastBelum ada peringkat

- Project Muse 602596Dokumen4 halamanProject Muse 602596HerlleyBelum ada peringkat

- Post-Tradisionalisme Islam:: Wacana Intelektualisme Dalam Komunitas NU RumadiDokumen38 halamanPost-Tradisionalisme Islam:: Wacana Intelektualisme Dalam Komunitas NU RumadimalabaerBelum ada peringkat

- Scientific Tradition in Indonesia and India - M.mujabDokumen18 halamanScientific Tradition in Indonesia and India - M.mujabMujab MuhammadBelum ada peringkat

- Favourite 3rd Party Transfer: SuccessfulDokumen1 halamanFavourite 3rd Party Transfer: SuccessfulAhmad BakhtiarBelum ada peringkat

- Receipt PDFDokumen1 halamanReceipt PDFAlan MathewBelum ada peringkat

- Favourite 3rd Party Transfer: SuccessfulDokumen1 halamanFavourite 3rd Party Transfer: SuccessfulAhmad BakhtiarBelum ada peringkat

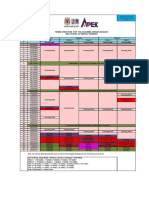

- KALENDAR AKADEMIK 20182019 PPSG Versi BI PDFDokumen1 halamanKALENDAR AKADEMIK 20182019 PPSG Versi BI PDFAlan MathewBelum ada peringkat

- Worth RM99: Capture The Perfect SelfieDokumen2 halamanWorth RM99: Capture The Perfect SelfieAlan MathewBelum ada peringkat

- Favourite 3rd Party Transfer: SuccessfulDokumen1 halamanFavourite 3rd Party Transfer: SuccessfulAlan MathewBelum ada peringkat

- KALENDAR AKADEMIK 20182019 PPSG Versi BI PDFDokumen1 halamanKALENDAR AKADEMIK 20182019 PPSG Versi BI PDFAlan MathewBelum ada peringkat

- Electronic Ticket Receipt, July 06 For MS ISABARIAH ISMAILDokumen2 halamanElectronic Ticket Receipt, July 06 For MS ISABARIAH ISMAILIsabariah IsmailBelum ada peringkat

- Morphological of Primary TeethDokumen88 halamanMorphological of Primary TeethDwi Riski SaputraBelum ada peringkat

- Mongoloid Dentition PDFDokumen7 halamanMongoloid Dentition PDFAlan MathewBelum ada peringkat

- Mahoney 2012 AJPADokumen16 halamanMahoney 2012 AJPAAlan MathewBelum ada peringkat

- Mongoloid Dentition PDFDokumen7 halamanMongoloid Dentition PDFAlan MathewBelum ada peringkat

- BashDokumen25 halamanBashGeorge BannermanBelum ada peringkat

- Jmcvay@andrews - Edu: of The Invisible God: Essays On The Influence of Jewish Mysticism On Early Christology, NovumDokumen18 halamanJmcvay@andrews - Edu: of The Invisible God: Essays On The Influence of Jewish Mysticism On Early Christology, NovumMitrache MariusBelum ada peringkat

- Paper English Class 9thDokumen3 halamanPaper English Class 9thQamar Zamans100% (1)

- ProverbsDokumen4 halamanProverbsMarietta Fragata RamiterreBelum ada peringkat

- Rodríguez Cuadros, J. (2018) - The Religious Shift in Latin America. Hérodote, 171, 119-134. - em Portugues OnlineDokumen18 halamanRodríguez Cuadros, J. (2018) - The Religious Shift in Latin America. Hérodote, 171, 119-134. - em Portugues OnlineValquiria AlmeidaBelum ada peringkat

- One in Christ Role of Women in MinistryDokumen6 halamanOne in Christ Role of Women in MinistryD. Boesuah DuobahBelum ada peringkat

- 925Dokumen40 halaman925B. MerkurBelum ada peringkat

- L1 - What Is ChristianityDokumen10 halamanL1 - What Is ChristianityMaryamBelum ada peringkat

- Jamb CRK Past QuestionsDokumen79 halamanJamb CRK Past Questionsabedidejoshua100% (1)

- Mark 7 The Audacity of FaithDokumen8 halamanMark 7 The Audacity of FaithScott BowermanBelum ada peringkat

- Test Bank For MGMT Principles of Management 3rd Canadian Edition Chuck Williams Ike Hall Terri Champion Isbn 0176703489 Isbn 9780176703486Dokumen36 halamanTest Bank For MGMT Principles of Management 3rd Canadian Edition Chuck Williams Ike Hall Terri Champion Isbn 0176703489 Isbn 9780176703486olivil.donorbipj100% (42)

- 070 The TWO PathsDokumen19 halaman070 The TWO PathsImtiaz MuhsinBelum ada peringkat

- Topics For Expansion of IdeaDokumen4 halamanTopics For Expansion of IdeaParkash SaranganiBelum ada peringkat

- Religious Extremism of Alexander DvorkinDokumen44 halamanReligious Extremism of Alexander DvorkinVarshavskyBelum ada peringkat

- History of The Church Didache Series: Chapter 1 - Jesus Christ Founds The ChurchDokumen31 halamanHistory of The Church Didache Series: Chapter 1 - Jesus Christ Founds The ChurchFr Samuel Medley SOLT100% (2)