Ref 4 PDF

Diunggah oleh

CoreyJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Ref 4 PDF

Diunggah oleh

CoreyHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Review article

Supported by a grant from Zeneca Pharmaceuticals

Clinical evaluation of asthma

James T C Li, MD* and Edward J OConnell, MD

Objective: The purpose of this article is to review the medical history and ing, shortness of breath, chest tight-

physical examination of the asthmatic patient. ness, and cough. What is the evidence

Data Sources: English references identified from relevant articles and book that these, indeed, are the most impor-

chapters, experts, and MEDLINE search, using asthma, physical diagnosis, and tant symptoms of asthma, and how of-

medical history. ten are these symptoms described by

Study Selection: Clinical studies of the medical history or physical examination individuals with asthma? It is very dif-

in subjects with respiratory disease were selected for review. ficult or impossible to offer an accurate

Results: Symptoms such as wheezing, chest tightness and difficulty in taking a answer to this question. However, pub-

deep breath suggest asthma, while symptoms such as gasping, smothering or air lished studies of symptoms of asthma

hunger suggest alternative diagnoses. Symptoms of asthma correlate poorly with can shed some light on this issue and

airway obstruction in one-third to one-half of asthmatic patients. Respiratory signs provide guidance for the differential

such as wheezing, breath sound intensity, forced expiratory time, accessory muscle diagnosis of asthma.

use, respiratory rate and pulsus paradoxus correlate roughly with airway obstruction. In one study, 53 patients with a va-

However, clinicians disagree on the presence or absence of respiratory signs 55% to riety of cardiopulmonary disorders in-

89% of the time. Furthermore, physicians correctly predict pulmonary function cluding asthma were asked to select

based on history and physical examination only about half the time, and correctly descriptions of their sensation of

diagnose asthma based on the clinical examination 63% to 74% of the time. breathlessness from a list of 19 de-

Conclusions: The medical history and physical examination are moderately scriptors.1 Analysis of the responses

effective in diagnosing asthma and estimating its severity. Objective measures of suggested that individuals with asthma

lung function are necessary for the accurate diagnosis of asthma. were more likely to select descriptors

Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1996;76:114. such as My breath does not go out all

the way, My chest feels tight, I

INTRODUCTION history and examination of the patient cannot take a deep breath, and My

The clinical evaluation of a new patient with asthma or possible asthma, an ex- breathing requires more concentra-

with asthma or possible asthma begins ample of which is shown in Table 1. tion. Individuals with asthma and in-

with a medical history, proceeds to a Rather, we will show how published dividuals with chronic obstructive pul-

physical examination of the patient, and clinical studies can guide the medical monary disease both selected the

often concludes with selected laboratory history and physical examination in descriptor My breathing requires ef-

studies. A careful and comprehensive asthma. We will point out where evi- fort or My breathing is heavy. On

medical history is essential for the diag- dence is lacking and when reliance on the other hand, individuals with

nosis and management of asthma. clinical judgement alone is required. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

In this review, we will draw from The four major issues we will address use descriptors such as I am gasping

clinical studies, experiences, and obser- are (1) What are the symptoms of for breath, I cannot get enough air,

vations to provide an evidentiary frame- asthma? (2) How do symptoms of and My breathing requires more

work for the clinical evaluation of asthma correlate with the degree of air- work while individuals with asthma

asthma. This review is not intended as a way obstruction? (3) How accurate is the did not. Similarly, individuals with

comprehensive exposition of the medical physical examination in asthma? and (4) congestive heart failure were more

How good are physicians at diagnosing likely to select descriptors such as I

asthma and estimating its severity? feel that my breath is rapid, I feel

Division of Allergic Diseases and Internal that I am smothering, My breathing

Medicine* and Pediatric Allergy and Immunol- WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS is heavy, and I feel a hunger for

ogy, Mayo Clinic and Foundation, Rochester, OF ASTHMA? more air while individuals with

Minnesota. Descriptors asthma did not. Thus, individuals with

Received for publication February 27, 1995.

Accepted for publication in revised form June Most clinicians would agree that the asthma use somewhat different terms

24, 1995. major symptoms of asthma are wheez- to describe their symptoms compared

VOLUME 76, JANUARY, 1996 1

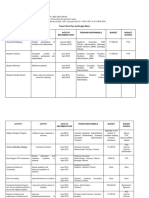

with individuals who have chronic ob- Table 1. The Medical History in Asthma

structive pulmonary disease or conges- I. Symptoms

tive heart failure. It is worth pointing A. Quality

out that wheezing and cough were not 1. Description

included on the dyspnea questionnaire. a. wheeze, breathlessness, cough, chest tightness, etc.

In a similar way, another study an- 2. Onset

alyzed a dyspnea questionnaire con- 3. Progression

B. Provoking or triggering factors

sisting of 45 descriptors of breathing

1. Exercise

discomfort from 169 patients with car- a. timing, duration, severity

diopulmonary disorders.2 Ninety-two b. effect on work, school, recreation

percent of asthmatic patients selected 2. Infection

the descriptor I feel wheezy, 83% a. frequency, severity

selected I feel short of breath or re- b. response to treatment

lated descriptors, and 81% selected 3. Allergens

My chest feels tight. The percentage a. season

of affirmative responses to these three b. animals, pets

descriptors were 76%, 82%, and 68%, c. occupational

d. risk factors for dust mite exposure

respectively, for chronic obstructive

e. related to hobbies, recreation

pulmonary disease and 28%, 54%, and f. associated rhinoconjunctivitis

41%, respectively, for cardiac disease. g. previous allergy testing

Thus, almost all patients with asthma 4. Irritant

include wheezing as one of their symp- a. fumes, dust, pollution

toms compared with about three out of b. smoking

four patients with chronic obstructive c. environmental smoke

pulmonary disease and about three out 5. Cold air

of ten patients with heart disease. It a. exercise in cold air

may be useful, then, for the physician 6. Medications

a. beta-adrenergic blocking agents

to elicit the description of respiratory

b. aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

symptoms from the patient in order to c. medications for co-morbid medical condition

form a differential diagnosis. Of 7. Emotional/stress

course, a detailed and comprehensive a. hyperventilation

medical history would include much b. panic attacks

more than simply a description of 8. Foods

symptoms, such as associated symp- a. sulfites

toms (eg, chest pain), and triggering or C. Alleviating factors

alleviating factors. 1. Rest, avoidance of physical activity

Interestingly, physiologic study of 2. Avoidance of allergens, irritants

3. Medications

dyspnea suggests that the descriptor

a. timing and duration (eg, beta-adrenergic agonists, corticosteroids)

My breath does not go out all the b. immunotherapy

way is associated with an increased II. Assessment of Severity

functional residual capacity (ie, pul- A. Severity of symptoms

monary hyperinflation) rather than air- 1. Frequency, number of episodes per day or week

way obstruction.35 Deliberate hyper- 2. Duration

ventilation is associated with the 3. Description of typical exacerbation

descriptor I feel hunger for more air 4. Response to treatment

or I cannot get enough air which B. Limitations of daily activity

might be helpful in differentiating 1. Walking, distance, pace

2. Stairs, number of flights

asthma from the hyperventilation syn-

3. Exercise, sports

drome.3 4. Sleep disturbance, early morning symptoms

Virtually all clinicians will recog- 5. Daily activity

nize that there is a wide variation in C. Hospitalizations

how patients perceive and describe 1. Number, frequency, length of stay

their symptoms of asthma. Studies an- 2. Intubation

alyzing the ability of individuals with 3. Intensive care

asthma to detect or describe resistive (continued on next page)

loading find significant variation

2 ANNALS OF ALLERGY, ASTHMA, & IMMUNOLOGY

Table 1. Continued among individuals.6 8 A few generali-

D. Emergency visits zations, however, can be made.

1. Number, frequency First, when the perception of exter-

2. Provoking factors nal resistive loading and induced bron-

3. Other unscheduled visits chospasm are compared, there is a

E. Days lost from work or school greater sense of dyspnea with broncho-

1. School or work performance spasm at any given level of resistance.6

F. Medication requirements

This suggests that airway resistance

1. Systemic coriticosteroid use

2. Beta-adrenergic agonist use

alone is not responsible for all asth-

a. number of puffs per day matic symptoms and that other physi-

b. number of canisters per month ologic derangements such as hyperin-

3. Inhaled corticosteroid, nedocromil, cromolyn use, theophylline, ipratropium flation or inflammation may be

4. Changes in medication requirements contributory.

G. Tests Second, psychologic status can af-

1. Previous or home peak flow measurements fect the description of respiratory

2. Previous spirometry symptoms. On one hand, individuals

III. Associated and Co-Morbid Medical Conditions with psychologic profiles of anxiety

A. Rhinitis

and dependency exhibit decreased per-

B. Sinusitis; nasal polyposis

C. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

ception of airway obstruction.8 On the

D. Gastroesophageal reflux other hand, respiratory symptoms such

E. Eczema as wheeze and dyspnea are correlated

F. Heart disease with anxiety, anger, and depression in

G. Hypertension patients without respiratory disease.9

H. Glaucoma Third, a study of 21 individuals with

I. Psychiatric disorder asthma showed that 19 subjects re-

IV. Current Medications ported increased inspiratory rather than

A. Asthma medications expiratory difficulty following metha-

B. All other medications

choline bronchoprovocation.5 Physio-

C. Non-prescription medications

D. Alternative medicine therapy

logic correlation suggested that the in-

V. Immunizations crease in inspiratory capacity (ie,

A. Childhood pulmonary hyperinflation) correlated

B. Influenza better with symptoms than the change

C. Pneumococcus in FEV1 (ie, airway obstruction). This

VI. Psychosocial sense of inspiratory dyspnea may be a

A. Residence result of increased inspiratory muscle

1. Slab construction, ventilation elastic loading caused by hyperinfla-

2. Humidity tion. A review of 119 patients experi-

3. Heating, cooling systems

encing acute asthma showed that 71%

4. Carpets, furnishings

5. Pets, hobbies

of patients found breathing air in more

6. Factors for dust mite, cockroach, rodents difficult compared with 19% who

7. Change in residence, previous residencies found breathing out more difficult.10

8. Other household members Interestingly, 78% of doctors surveys

B. Occupation thought that their asthmatic patients

1. Current and previous found expiration more difficult.10

a. building, location Fourth, a study of 28 asthmatic in-

b. daily activity dividuals undergoing allergen bron-

c. exposure to allergen and irritants choprovocation suggests that per-

C. School

ceived breathlessness is closely related

1. Performance

2. Phobia

to the rate of fall in FEV1 rather than

3. Physical education the absolute degree of airway obstruc-

4. Relationship with peers, teachers tion.11 Asthmatic individuals thus de-

D. Hobbies scribed a stronger sense of dyspnea

1. Animals during the rapid fall in FEV1 during the

2. Exposure early asthmatic response and lower de-

3. Hobbies of family members grees of dyspnea during the slower fall

(continued on next page) of FEV1 of the late asthmatic response.

VOLUME 76, JANUARY, 1996 3

Table 1. Continued

fectively ruled out the presence of

E. Education

1. Level of general education

asthma while a positive methacholine

2. Level of asthma education challenge indicated a 74% chance that

3. Need for additional asthma education the cough was caused by asthma. In

F. Financial this same study, 14 of 45 or 29% of

1. Health insurance patients presenting with chronic cough

2. Impact on patient and family finances were diagnosed as having cough

G. Patient perceptions caused by asthma. Importantly, this

1. Concerns, fears, current understanding of medical problem and other studies19,20 show that inter-

2. Concerns, fears, current understanding of family or significant others pretation of the medical history is not

3. Impact of medical problem on patient, life, family

very effective at predicting the pres-

H. Psychiatric and personality

1. Anxiety, dependence

ence or absence of bronchial hyperre-

2. Depression sponsiveness. For patients with

3. Rebelliousness chronic cough, a concomitant history

4. Marital or family discord of dyspnea increased the likelihood

5. Somatization that the cough was caused by asthma

6. Physical, psychologic, sexual abuse, current or previous by tenfold.15 A history of wheezing,

7. Major psychiatric disorder cough with respiratory tract infection,

VII. Family History and a previous diagnosis of asthma

A. Asthma were not significantly linked to asth-

B. Respiratory diseases

ma-induced cough in this study.

C. Allergy, rhinitis, eczema

D. Marital status

Cough, therefore, can be an impor-

E. Marital and family discord tant symptom of asthma. Cough in-

F. Impact of medical problem on family duced by respiratory infections, cold

air and exercise, along with nocturnal

cough, may be suggestive of asthma.

Although the presence of dyspnea in

Collectively, these observations Cough may be the primary or sole addition to cough is suggestive of

suggest that wheezing, shortness of presenting symptom of some chil- asthma, a previous diagnosis of

breath, and chest tightness are indeed dren or adults with asthma.13,14 A re- asthma, a history of wheezing, the du-

important symptoms of asthma. Fur- view of cough symptoms in 32 chil- ration of cough, and personal or family

thermore, an accurate medical history dren with asthma whose primary history of allergy are not helpful in

should include elicitation of the symp- symptom was chronic cough showed predicting whether or not chronic

tom descriptors, which may be helpful that cough was triggered by an upper cough is caused by asthma.15,17 A long-

in differentiating asthma from chronic respiratory tract infection in 100% of term follow-up study of 78 adults who

obstructive pulmonary disease, con- patients, the cough was exercise-in- underwent diagnostic methacholine

gestive heart failure, and hyperventila- duced in 78%, the cough was noctur- challenge suggests that individuals

tion. Symptoms of asthma are caused nal in 72%, and was induced by cold who had a positive methacholine chal-

by pulmonary hyperinflation as well as air in 44% of patients.13 lenge were more likely to develop

airway obstruction, and a high rate of The idea that cough can be the sole symptoms of chest tightness, wheez-

change in airway obstruction, charac- symptom of patients with asthma is ing, and dyspnea.18 Interestingly, de-

teristic of many asthmatic patients, closely linked to the demonstration of velopment of cough was not correlated

may result in heightened perception of nonspecific bronchial hyperrespon- with the results of the previous metha-

breathlessness. Finally, individuals siveness in these individuals.14 17 The choline bronchial challenge. These re-

with anxious and dependent personal- definitive diagnosis of the cause of a sults together suggest that a careful

ity traits may display a decreased sen- chronic cough, however, may take medical history will not be sufficient to

sation of airway obstruction. This lat- years to elucidate or may never be establish whether or not asthma is the

ter finding clearly has important fully understood in individual pa- major cause of chronic cough for many

clinical significance since patients with tients.18 Recognizing these limitations, patients. The methacholine bronchial

asthma who have decreased perception the authors of one study estimated that challenge is a useful test for many of

of airway obstruction or hypoxia are at the methacholine bronchial challenge these patients, although close fol-

risk for fatal and nearly fatal asthma.12 had a negative predictive value of low-up and assessing the response to

Chronic cough is an important 100% and a positive predictive value therapy are also very important.

symptom for many patients with of 74% for chronic cough caused by Asthma may cause other symptoms

asthma, although by convention is asthma.15 In other words, in this study such as chest pain, particularly in chil-

not considered a form of dyspnea. a negative methacholine challenge ef- dren. While most studies suggest that

4 ANNALS OF ALLERGY, ASTHMA, & IMMUNOLOGY

asthma is an important cause of chest HOW DO ASTHMATIC decreased 54% of the time and FEV1

pain in about 20% of children present- SYMPTOMS CORRELATE was decreased 36% of the time. When

ing with chest pain, one study demon- WITH AIRWAY patients recovering from acute asthma

strated exercise-induced airway ob- OBSTRUCTION? were studied, pulmonary function was

struction in 73% of such children.21 The preceding review shows that the only between 40% and 50% of pre-

symptoms of wheeze, shortness of dicted normal values when symptoms

Respiratory Questionnaires

breath, chest tightness, and cough are disappeared.34 Collectively, these ob-

Epidemiologic surveys have used re- servations clearly show that one-third

spiratory questionnaires to estimate the important in asthma. How well or how

poorly symptoms of asthma correlate to one-half of asthmatic patients under-

prevalence of respiratory symptoms estimate the severity of asthma when

and to correlate these symptoms with with asthma severity is a different

question entirely. This issue has great judged by symptoms alone. Appar-

cardiopulmonary disease states. In one ently, the perception of asthma cannot

such survey,22 59% of patients with a clinical significance since management

decisions in asthma are founded in be learned, inasmuch as home record-

new diagnosis of asthma reported ing of peak expiratory flow rates does

wheezing compared with 19% of con- large part on the physicians estimate

of the severity of asthma. With few not improve the subjective assessment

trol patients, and 31% of patients with of asthma severity.35 Nor does the use

a new diagnosis of asthma reported exceptions, the evidence to date clearly

indicates that asthmatic symptoms cor- of symptom questionnaires improve

shortness of breath with wheezing the perception of airway obstruction.36

compared with only 6% of controls. Of relate poorly with the degree of airway

obstruction for a significant proportion Perhaps one-third to one-half of asth-

interest, 69% of asthmatic patients re- matic patients can successfully esti-

ported symptoms of rhinitis compared of asthmatic patients; hence, objective

measurement of airway obstruction is mate their degree of airway obstruc-

with 39% of control patients. These tion. One study of ten asthmatic

same data showed that individuals who essential for these individuals.

subjects showed that a symptom diary

reported any wheeze or shortness of In one study, 255 individuals with

was superior to daily peak flow moni-

breath with wheezing were seven times asthma estimated the severity of symp-

toring in detecting exacerbations of

more likely to have asthma compared toms of asthma using a visual analog

asthma.37

with those who did not. Individuals scale while measurements of peak ex-

These findings together are impor-

who reported rhinitis were more than piratory flow rate were taken at the

tant because poor perception of asthma

three times more likely to have asthma same time.29 Sixty percent of patients may be a risk factor for fatal asthma.

compared with those who did not. A showed no significant correlation be- Patients with histories of nearly fatal

history of rhinitis may be moderately tween subjective asthma scores and asthma show reduced chemosensitivity

useful in the diagnosis of asthma. peak expiratory flow rate measure- and blunted perception of dyspnea.12

Reported wheezing is found in up to ments. Study of 82 patients with Psychiatric disease and psychologic

30% of survey populations22 and per- asthma undergoing methacholine bron- disturbances are also important risk

sistent wheezing is present in about chial challenge showed that 15% of factors for fatal asthma.38 Such patients

10% of children.23 Similar studies sug- patients were unable to subjectively may also have blunted perceptions of

gest that dyspnea is present in 5% to detect reverse airway obstruction (50% airway obstruction.7

25% of the general population.24 26 A predicted or lower).30 A similar study

study of 1,392 male workers using a of asthmatic patients undergoing bron- HOW ACCURATE IS THE

standardized respiratory questionnaire choprovocation showed that although PHYSICAL EXAMINATION IN

showed that individuals reporting symptoms of breathlessness were sta- ASTHMA?

wheezing or breathlessness, and espe- tistically correlated with FEV1 (r 5 If symptoms of asthma correlate

cially those with both symptoms, were .88),31 there was a large variation in the poorly with airway obstruction in a

more likely to show a low PC20 when severity of breathlessness for any par- significant proportion of asthmatic pa-

undergoing a methacholine bronchial ticular degree of airway obstruction. tients, is the physical examination an

challenge. The symptom of chest tight- Study of patients with nocturnal accurate and inexpensive way to eval-

ness was not independently correlated asthma shows that the increase in air- uate asthma severity? There is a rough

with bronchial hyperresponsiveness.27 way obstruction in the early morning correlation between the presence of

Another study showed that wheeze hours may go undetected in one-third wheezing on physical examination and

and attacks of shortness of breath of patients.32 the severity of airflow obstruction.39 41

with wheeze were independently pre- In another study, 20 children with Although loud wheezing is associated

dictive of asthma.28 Surveys using re- asthma were studied over a 16-week with greater airway obstruction, the

spiratory questionnaires confirm that period with symptom scores, peak ex- degree of correlation between wheez-

the symptom of wheezing or wheezing piratory flow readings, and measure- ing and airway obstruction is modest

combined with shortness of breath are ment of FEV1.33 During asymptomatic and there is great variability.39,40 These

highly suggestive of asthma. periods, peak expiratory flow rate was and other studies suggest that wheez-

VOLUME 76, JANUARY, 1996 5

ing during inspiration and expiration, way obstruction.49 51 Decreased breath The presence of pulsus paradoxus is

loudness of wheezing and prolonged sound intensity presumably is caused associated with severe obstructive lung

duration of wheezing during the respi- by a combination of decreased acoustic disease including asthma.59,60 A study

ratory cycle are associated with greater transmission through the lung and of 93 patients with asthma showed that

airway obstruction.39,40,42,43 Wheezing chest wall combined with decreased a pulsus paradoxus was associated

during forced exhalation apparently inspired and expired lung volumes and with a peak expiratory flow rate of

does not correlate with airway obstruc- flow rates. 33% of predicted values on average.59

tion or bronchial hyperresponsive- The forced expiratory time is mea- Similarly, the respiratory rate corre-

ness.40,44 sured by instructing the subject to in- lates modestly (r 5 .42) with peak

The stethoscope and human ear to- hale maximally and then exhale force- expiratory flow rates in patients with

gether limit the usefulness of wheezing fully through a completed forced vital acute asthma.61

as a measure of airway obstruction. capacity maneuver. The examiner Auscultation at the mouth or trachea

Analysis of recorded lung sounds times the exhalation maneuver and shows that wheezing may be transmit-

shows that there is a good correlation records a forced expiratory time. Com- ted much better through the airways

between the duration of wheezing dur- parison of forced expiratory time and than across the chest wall.62 Wheez-

ing the breath cycle and the FEV1 (r 5 FEV1 shows that a prolonged forced ing over the neck, particularly when

.89).42,43 Another computer-assisted expiratory time of six seconds or predominantly inspiratory, suggests

lung sound analysis showed that lung longer is associated with increased air- stridor and upper airway obstruction,

sound mapping correctly classified way obstruction.52,53 As a test for ob- rather than asthma.63

about 70% of subjects with a variety of structive airway disease, the forced ex- In summary, the presence of wheez-

cardiopulmonary disorders such as in- piratory time has a sensitivity of 74% ing, the duration of wheezing as a pro-

terstitial pulmonary fibrosis, chronic to 92% and a specificity of 43% to portion of the breath cycle, inspiratory

obstructive pulmonary disease, con- 75%.52,53 and expiratory wheezing, and the loud-

gestive heart failure, and pneumonia.45 Individuals with chronic obstructive ness of wheezing all correlate roughly

Lung sound analysis of asthmatic chil- pulmonary disease and emphysema with airway obstruction. The intensity

dren undergoing bronchoprovocation may exhibit a constellation of physical of breath sounds and the forced expi-

showed that wheezing detected by lung findings that is somewhat different ratory time both correlate reasonably

sound analysis was much more sensi- from asthma. Increased resonance to well with airway obstruction. Both

tive at detecting airway obstruction percussion, excavation of the supracla- pulsus paradoxus and a rapid respira-

than respiratory symptoms or wheez- vicular fossa, tracheal tug, and acces- tory rate are associated with severe

ing on auscultation.46 Auscultated sory muscle activity correlate signifi- airway obstruction. Despite the statis-

wheezes during bronchoprovocation cantly with airway obstruction in tically significant correlation of these

are not as sensitive as direct measure- patients with chronic obstructive lung respiratory signs with airflow obstruc-

ment of FEV1, however.47 disease.49,50,54,56 As described above, tion, it is nevertheless very difficult for

Since auscultation for wheezing in the forced expiratory time and breath clinicians to estimate airway obstruc-

the office and hospital setting is gen- sound intensity correlate reasonably tion accurately based on the physical

erally confined to auscultation with the well with objective measures of air- examination alone. One reason for this

stethoscope, we conclude that there is flow obstruction.49,51 A study of 31 pa- is the correlation of physical signs with

only a rough correlation between tients with chronic obstructive pulmo- measures of airflow obstruction is not

wheezing and airway obstruction. nary disease showed that of patients always close enough to be clinically

Most clinicians would agree that sig- with severe obstruction (FEV1 one liter important. Another important reason is

nificant airway obstruction can be or less), 100% used accessory muscles, the wide observer variability of skill in

present in the absence of wheezing on 70% had wheezing, 62% had dimin- the physical examination of the chest.

examination. ished breath sounds, and 44% had in- One study of interobserver variabil-

The respiratory signs of breath creased resonance to percussion.57 In ity in eliciting physical signs in exam-

sound intensity and forced expiratory contrast, among patients with milder ination of the chest showed that a

time have both been correlated with obstruction (FEV1 . 1.1 L) approxi- group of four physicians agreed with

airway obstruction. Examination of mately 39% showed accessory muscle the presence or absence of a physical

183 patients referred to a pulmonary use, 30% had wheezing, 21% had di- sign only 55% of the time.64 Fortu-

function laboratory showed that breath minished breath sounds, and 14% had nately, the presence or absence of

sound intensity correlated with mea- increased resonance to percussion.57 In wheezing seemed somewhat more re-

surements of FEV1.48 Other studies of asthmatic children, severe airway ob- liable than other respiratory signs since

physical findings in chronic obstruc- struction correlates with accessory physicians were in complete agree-

tive pulmonary disease support the ob- muscle use, although prolonged expi- ment 63% of the time. In a separate

servation that reduced intensity of ration and wheezing predicted airway study of intraobserver and interob-

breath sounds is associated with air- obstruction poorly.58 server variability, there was disagree-

6 ANNALS OF ALLERGY, ASTHMA, & IMMUNOLOGY

ment about physical findings of the accuracy of 66% based on the medical pulmonary function studies in pa-

chest 11% to 26% of the time.65 Fur- history, physical examination, and tients with asthma or other respira-

ther, medical students demonstrated chest radiograph.68 These patients were tory diseases. One study of hospital-

better self-consistency than pulmonary seen at a subspecialty clinic and were ized asthmatic patients showed that

specialists. Rhonchi (low pitched evaluated by board certified pulmo- physicians were able to estimate the

wheezes)66 and wheezes64 66 seem nologists. A similar study based in a peak expiratory flow rate to within

more reliably detected than other respi- general internal medicine clinic 20% of the measured value only 44%

ratory signs. These studies suggest that showed that internists were able to di- of the time based on physical exam-

physicians agree on the presence or agnose patients with dyspnea correctly ination alone. The correlation coeffi-

absence of physical signs of the respi- 74% of the time.69 cient was 0.66.76 In a similar study,

ratory system 55% to 89% of the Study of the medical history in physicians referring patients for pul-

time.57,64 66 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease monary function tests were asked to

Although physicians are moderately suggests that independent predictors of predict the nature of the ventilatory

successful in eliciting respiratory obstructive airway disease from the defect (eg, obstructive, restrictive,

signs, there is considerable disagree- clinical examination were patient re- normal) and estimate the severity of

ment among observers when the same ported wheezing, auscultated wheez- the abnormality.77 Physicians cor-

patients are examined, and even signif- ing, number of years the patient had rectly predicted airway obstruction in

icant variation when a single observer smoked cigarettes, forced expiratory 81% of cases. On the other hand,

examines the same patient on multiple time, and peak expiratory flow rate.70 61% of the tests gave a result that the

occasions. Nevertheless, most clini- A similar study suggested that a previ- physicians predicted as being un-

cians would agree that the pulmonary ous diagnosis of chronic obstructive likely, and physicians were unable to

examination is important for patients pulmonary disease, 70 pack year predict reversibility of airflow ob-

with asthma or possible asthma. For smoking history, and diminished struction in patients with obstructive

example, the presence of wheezing breath sounds on examination sug- lung disease. Similar conclusions

would suggest clinically important air- gested the diagnosis of chronic ob- were reached in a study of 71 chil-

way obstruction, although the absence structive pulmonary disease.71,72 A dren presenting to an emergency

of wheezing would not rule it out. study of patients admitted to the hos- room with acute asthma.78 Based on

In one clinical study, investigators pital for dyspnea showed that the re- the medical history and physical ex-

trained actresses to simulate a new pa- ferring physicians diagnoses were amination, physicians were moder-

tient with asthma.67 The chest was not correct only 66% of the time.73 ately successful in predicting FEV1

examined in 61% of 74 consultations. A study of 162 patients with pos- (correlation coefficient 0.47). On the

We suggest that all new patients with sible work related asthma suggests other hand, the addition of spirome-

asthma or possible asthma should un- that the type and timing of respira- try results in a pulmonary medicine

dergo a careful examination of the chest tory symptoms was modestly useful continuity clinic altered the clinical

and lungs. Although there is no direct in differentiating occupational management plan in only 5% of pa-

evidence to indicate that physical exam- asthma from asthma that was not tients.79 Patients with severe lung

ination of the chest results in improved work related.74 For example, symp- dysfunction or deteriorating clinical

patient outcomes, clinicians should be toms at work were reported by 91% status benefited most from spirome-

aware of the benefits and limitations of of patients with occupational asthma try.

the pulmonary examination. and 86% of patients without occupa- Physicians are also only moder-

tional asthma. Improvement of ately successful in predicting non-

HOW GOOD ARE PHYSICIANS symptoms on weekends or on holi- specific bronchial hyperresponsive-

AT DIAGNOSING ASTHMA AND days were reported by 77% and 88%, ness. In a study of 34 patients

ESTIMATING ITS SEVERITY? respectively, of patients with occupa- evaluated for unexplained wheezing,

While it may be useful or interesting to tional asthma and 56% and 76%, re- the clinical history was only moder-

understand the clinical implications of spectively, by patients without occu- ately successful in predicting the re-

symptoms of asthma and to appreciate pational asthma. The investigators sults of a methacholine bronchial

the limitations of the pulmonary exam- estimate that the predictive value of challenge.80 A previous diagnosis of

ination, physicians reach clinical im- a history suggesting occupational asthma predicted bronchial hyperre-

pressions based on the complete med- asthma was 63%. These findings are activity 62% of the time; a history of

ical history and physical examination. consistent with the observation that past wheezing, 35% of the time; and

There has been some study of the di- occupational asthma may be cor- expiratory wheezing on examination,

agnostic usefulness of the medical his- rectly diagnosed only 12% of the 43% of the time. A separate study of

tory in patients with asthma. One study time.75 51 patients with possible asthma and

prospectively evaluated 85 patients Physicians are only moderately normal spirometry showed that phy-

with dyspnea and found a diagnostic successful in predicting the results of sicians were able to predict the re-

VOLUME 76, JANUARY, 1996 7

sults of a methacholine challenge test examination, chest radiograph, and should have office spirometry per-

successfully only 39% of the time.81 spirometry demonstrated that 17% had formed, at minimum, for initial as-

When chest physicians were asked to undiagnosed asthma83; hence, asthma sessment.86 We support this recom-

predict the result of a histamine bron- is commonly unrecognized in both mendation. Some asthma experts

chial challenge in a group of patients adults and children. suggest that the peak expiratory flow

with possible asthma, there was no rate can substitute for measurement

correlation at all between physician pre- CONCLUDING COMMENTS of FEV1 for patients with asthma.

dictions (based on a medical history and Physicians should recognize the limi- Indeed, there is ample evidence to

physical examination) and bronchial tations of the medical history and show that the peak expiratory flow

hyperresponsiveness.19 Another study physical examination even when con- rate and FEV1 are closely correlated

showed that patient responses on a med- ducted by an expert. An unbiased de- in asthma.87,88 These studies also

ical history questionnaire could not pre- scription of symptoms of asthma may show that there is a significant vari-

dict bronchial responses to histamine.20 be more effectively elicited through ation in peak expiratory flow rate for

These studies together support the open-ended questions such as Please a given measurement of FEV1, typi-

notion that the medical history and describe your symptoms, rather than cally in the range of 620%.86 Fur-

physical examination are useful and directed questions such as Do you ther, the peak expiratory flow rate is

moderately successful in diagnosing have wheezing or shortness of breath? often misleading when chronic ob-

asthma and estimating its severity. To a limited extent, symptom descrip- structive pulmonary disease or re-

Chest specialists and internists can be tors such as wheezing and chest tight- strictive lung disease is present.

expected to diagnose asthma correctly ness may suggest asthma, although a Measurement of the peak expiratory

about two-thirds or three-quarters of full medical history should include flow rate with a peak flow meter is less

the time. At the same time, these pub- triggering and alleviating factors, re- expensive than measurement of FEV1

lished observations highlight the limi- sponse to treatment, and associated with spirometry; however, misdiagno-

tations of the clinical evaluation of symptoms. sis of asthma and underestimating se-

asthma, even by specialists. Measures Physical examination of the chest, verity of asthma are costly as well.

of lung function, in particular spirom- especially for the presence and quality Further studies are needed to deter-

etry with response to bronchodilator, of wheezing has moderate predictive mine whether measurement of pulmo-

are needed to confirm a diagnosis of value in diagnosing asthma and esti- nary function actually results in inter-

asthma. mating the degree of airway obstruc- vention that improves symptoms, lung

These limitations become apparent tion. Additional respiratory signs such function, frequency of hospitalizations,

in studies of undiagnosed asthma. A as breath sound intensity and forced or days missed from work or school.

survey of 14,127 patients showed that expiratory time may be useful. Physi- Further studies may elucidate the rela-

physician-diagnosed asthma was re- cians should be familiar with the phys- tive advantages of peak flow measure-

ported by 6.1% of patients, but that ical signs of other causes of dyspnea ment and spirometry.

undiagnosed asthma that was active such as chronic obstructive pulmonary We recommend that physicians car-

within the previous year was reported disease, congestive heart failure, hy- ing for patients with asthma continue

by 3.3% of patients.82 This suggests perventilation, and foreign body aspi- to develop their interviewing and phys-

that one-third of asthmatic patients ration. ical examination skills. At the same

have not been properly diagnosed. An- A detailed medical history and phys- time, the best care of the asthmatic

other report suggests that 17% of pa- ical examination of the patient with patient includes spirometry at the time

tients with unexplained dyspnea may possible asthma leads to the correct of initial diagnosis and monitoring of

have asthma.83 A study of 179 children diagnosis about three quarters of the pulmonary function through periodic

who reported at least one episode of time, even by asthma specialists. Be- spirometry and peak expiratory flow

wheezing showed that only 21 children cause it is impossible to identify mis- rate measurements.

had been diagnosed with asthma,84 in- diagnosed patients prospectively, addi-

cluding 11 of 31 children who experi- tional studies such as peak expiratory REFERENCES

enced more than 12 episodes of wheez- flow rate measurements, spirometry, or 1. Simon PM, Schwartzstein RM, Weiss

ing per year. When these latter the methacholine bronchial challenge JW, et al. Distinguishable types of dys-

children were treated for asthma, are needed. Furthermore, even when pnea in patients with shortness of

school absenteeism fell tenfold. Chil- asthma is diagnosed correctly, both pa- breath. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;142:

1009 14.

dren with asthma whose symptoms tients and physicians are only moder- 2. Elliott MW, Adams L, Cockcroft A, et

were a chronic cough rather than ately successful in estimating the de- al. The language of breathlessness.

wheezing often remained undiagnosed gree of airway obstruction. Use of verbal descriptors by patients

for years.85 Review of 72 physician- The National Asthma Education with cardiopulmonary disease. Am

referred adult patients with dyspnea Program recommends that all pa- Rev Respir Dis 1991;144:826 32.

unexplained by initial history, physical tients suspected of having asthma 3. Simon PM, Schwartzstein RM, Weiss

8 ANNALS OF ALLERGY, ASTHMA, & IMMUNOLOGY

JW, et al. Distinguishable sensations Allergy Clin Immunol 1987;79:3315. 31. Burdon JGW, Juniper EF, Killian KJ,

of breathlessness induced in normal 18. Muller BA, Leick CA, Suelzer M, et et al. The perception of breathlessness

volunteers. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989; al. Prognostic value of methacholine in asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis 1982;

140:10217. challenge in patients with respiratory 126:825 8.

4. McFadden ER Jr. Exertional dyspnea symptoms. J Allergy Clin Immunol 32. Bellia V, Visconti A, Insalaco G, et al.

and cough as preludes to acute attacks 1994;94:77 87. Validation of morning dip of peak ex-

of bronchial asthma. N Engl J Med 19. Desjardins A, De Luca S, Cartier A, et piratory flow as an indicator of the

1975;292:5559. al. Nonspecific bronchial hyperrespon- severity of nocturnal asthma. Chest

5. Lougheed MD, Lam M, Forkert L, et siveness to inhaled histamine and hy- 1988;94:108 10.

al. Breathlessness during acute bron- perventilation of cold dry air in sub- 33. Ferguson AC. Persisting airway ob-

choconstriction in asthma. Pathophys- jects with respiratory symptoms of struction in asymptomatic children

iologic mechanisms. Am Rev Respir uncertain etiology. Am Rev Respir Dis with asthma with normal peak expira-

Dis 1993;148:14529. 1988;137:1020 5. tory flow rates. J Allergy Clin Immu-

6. Kelsen SG, Prestel TF, Cherniack NS, 20. Dales RE, Nunes F, Partyka D, Ernst nol 1988;82:19 22.

et al. Comparison of the respiratory P. Clinical prediction of airways hy- 34. McFadden ER Jr, Kiser R, DeGroot

responses to external resistive loading perresponsiveness. Chest 1988;93: WJ. Acute bronchial asthma. Relations

and bronchoconstriction. J Clin Invest 984 6. between clinical and physiologic man-

1981;67:1761 8. 21. Wiens L, Sabath R, Ewing L, et al. ifestations. N Engl J Med 1973;288:

7. Hudgel DW, Cooperson DM, Kinsman Chest pain in otherwise healthy chil- 2215.

RA. Recognition of added resistive dren and adolescents is frequently 35. Sly PD, Landau LI, Weymouth R.

loads in asthma. The importance of caused by exercise-induced asthma. Home recording of peak expiratory

behavioral styles. Am Rev Respir Dis Pediatrics 1992;90:350 3. flow rates and perception of asthma.

1982;126:1215. 22. Dodge RR, Burrows B. The preva- Am J Dis Child 1985;139:479 82.

8. Burki NK, Mitchell K, Chaudhary BA, lence and incidence of asthma and 36. Mahler DA, Rosiello RA, Harver A, et

Zechman FW. The ability of asthmat- asthma-like symptoms in a general al. Comparison of clinical dyspnea rat-

ics to detect added resistive loads. Am population sample. Am Rev Respir ings and psychophysical measure-

Rev Respir Dis 1978;117:715. Dise 1980;122:56775. ments of respiratory sensation in ob-

9. Dales RE, Spitzer WO, Schechter MT, 23. Speizer FE. Asthma and persistent structive airway disease. Am Rev

Suissa S. The influence of psycholog- wheeze in the Harvard Six Cities Respir Dis 1987;135:1229 33.

ical status on respiratory symptom re- Study. Chest 1990;98:191S. 37. Gibson PG, Wong BJO, Hepperle

porting. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989;139: 24. Hammond EC. Some preliminary find- MJE, et al. A research method to in-

1459 63. ings on physical complaints from a duce and examine a mild exacerbation

10. Morris MJ. Asthma-expiratory dys- prospective study of 1,064,004 men of asthma by withdrawal of inhaled

pnoea? Br Med J 1981;283:838 9. and women. Am J Public Health 1964; corticosteroid. Clin Exp Allergy 1992;

11. Turcotte H, Boulet L-P. Perception of 54:123. 22:52532.

breathlessness during early and late 25. Higgins ITT. Respiratory symptoms, 38. Yellowlees PM, Ruffin RE. Psycho-

asthmatic responses. Am Rev Respir bronchitis and ventilatory capacity in a logical defenses and coping styles in

Dis 1993;148:514 8. random sample of an agricultural pop- patients following a life-threatening at-

12. Kikuchi Y, Okabe S, Tamura G, et al. ulation. Br Med J 1957;2:1198 203. tack of asthma. Chest 1989;95:

Chemosensitivity and perception of 26. Fedullo AL, Swinburne AJ, McGuire- 1298 303.

dyspnea in patients with a history of Dunn C. Complaints of breathlessness 39. Shim CS, Williams MH Jr. Relation-

near-fatal asthma. N Engl J Med 1994; in the emergency department. The ex- ship of wheezing to the severity of

330:1329 34. perience at a community hospital. NY obstruction in asthma. Arch Intern

13. Corrao WM, Braman SS, Irwin RS. State J Med 1986;86:4 6. Med 1983;143:890 2.

Chronic cough as the sole presenting 27. Enarson DA, Vedal S, Schulzer M, et 40. Marini JJ, Pierson DJ, Hudson LD,

manifestation of bronchial asthma. N al. Asthma, asthmalike symptoms, Lakshminarayan S. The significance of

Engl J Med 1979;300:6337. chronic bronchitis and the degree of wheezing in chronic airflow obstruc-

14. Hannaway PJ, Hopper DK. Cough bronchial hyperresponsiveness in epi- tion. Am Rev Respir Dis 1979;120:

variant asthma in children. JAMA demiologic surveys. Am Rev Respir 1069 72.

1982;247:206 8. Dis 1987;136:6137. 41. Holleman DR Jr, Simel DL. Does the

15. Pratter MR, Bartter T, Akers S, 28. Dodge R, Cline MG, Lebowitz MD, clinical examination predict airflow

DuBois J. An algorithmic approach to Burrows B. Findings before the diag- limitation? JAMA 1995;273:3139.

chronic cough. Ann Intern Med 1993; nosis of asthma in young adults. J Al- 42. Baughman RP, Loudon RG. Lung

119:977 83. lergy Clin Immunol 1994;94:8315. sound analysis for continuous evalua-

16. Cloutier MM, Loughlin GM. Chronic 29. Kendrick AH, Higgs CMB, Whitfield tion of airflow obstruction in asthma.

cough in children: a manifestation of MJ, Laszlo G. Accuracy of perception Chest 1985;88:364 8.

airway hyperreactivity. Pediatrics of severity of asthma: patients treated 43. Baughman RP, Loudon RG. Quantita-

1981;67:6 12. in general practice. Br Med J 1993; tion of wheezing in acute asthma.

17. Galvez RA, McLaughlin FJ, Levison 307:422 4. Chest 1984;86:718 22.

H. The role of the methacholine chal- 30. Rubinfeld AR, Pain MCF. Perception 44. King DK, Thompson BT, Johnson DC.

lenge in children with chronic cough. J of asthma. Lancet 1976;1:882 4. Wheezing on maximal forced exhala-

VOLUME 76, JANUARY, 1996 9

tion in the diagnosis of atypical Thorax 1970;25:2857. ing obstructive airways disease in

asthma. Ann Intern Med 1989;110: 57. Godfrey S, Edwards RHT, Campbell high-risk patients. Chest 1994;106:

4515. EJM, et al. Repeatability of physical 142731.

45. Bettencourt PE, Del Bono EA, signs in airways obstruction. Thorax 73. Wallace JI, Coral FS, Rimm IJ, et al.

Spiegelman D, et al. Clinical utility of 1969;24:4 9. Diagnosing the breathless patient. Lan-

chest auscultation in common pulmo- 58. Commey JOO, Levison H. Physical cet 1982;1:907 8.

nary diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care signs in childhood asthma. Pediatrics 74. Malo J-L, Ghezzo H, LArcheveque J,

Med 1994;150:12917. 1976;58:537 41. Lagier F, et al. Is the clinical history a

46. Beck R, Dickson U, Montgomery MD, 59. Shim C, Williams MH Jr. Pulsus para- satisfactory means of diagnosing occu-

Mitchell I. Histamine challenge in doxus in asthma. Lancet 1978;1: pational asthma? Am Rev Respir Dis

young children using computerized 530 1. 1991;143:528 32.

lung sounds analysis. Chest 1992;102: 60. Rebuck AS, Pengelly LD. Develop- 75. Burge PS. Problems in the diagnosis of

759 63. ment of pulsus paradoxus in the pres- occupational asthma. Br J Dis Chest

47. Noviski N, Cohen L, Springer C, et al. ence of airways obstruction. N Engl J 1987;81:10515.

Bronchial provocation determined by Med 1973;288:66 9. 76. Shim CS, Williams MH Jr. Evaluation

breath sounds compred with lung func- 61. Kesten S, Maleki-Yazdi R, Sanders of the severity of asthma: Patients ver-

tion. Arch Dis Child 1991;66:9525. BR, et al. Respiratory rate during acute sus physicians. Am J Med 1980;68:

48. Pardee NE, Martin CJ, Morgan EH. A asthma. Chest 1990;97:58 62. 113.

test of the practical value of estimating 62. Loudon R, Murphy RLH Jr. Lung 77. Russell NJ, Crichton NJ, Emerson PA,

breath sound intensity. Breath sounds sounds. Am Rev Respir Dis 1984;130: Morgan AD. Quantitative assessment

related to measured ventilatory func- 66373. of the value of spirometry. Thorax

tion. Chest 1976;70:341 4. 63. Baughman RP, Loudon RG. Stridor: 1986;41:360 3.

49. Bohadana AB, Peslin R, Uffholtz H. differentiation from asthma or upper 78. Kerem E, Canny G, Tibshirani R, et al.

Breath sounds in the clinical assess- airway noise. Am Rev Respir Dis Clinical-physiologic correlations in

ment of airflow obstruction. Thorax 1989;139:14079. acute asthma of childhood. Pediatrics

1978;33:34551. 64. Spiteri MA, Cook DG, Clarke SW. 1991;87:481 6.

50. Schneider IC, Anderson AE Jr. Corre- Reliability of eliciting physical signs 79. Owens MW, Anderson W McD,

lation of clinical signs with ventilatory in examination of the chest. Lancet George RB. Indications for spirometry

function in obstructive lung disease. 1988;1:8735. in outpatients with respiratory disease.

Ann Intern Med 1965;62:477 85. 65. Mulrow CD, Dolmatch BL, Delong Chest 1991;99:730 4.

51. van Schayck CP, van Weel C, Harbers ER, et al. Observer variability in the 80. Pratter MR, Hingston DM, Irwin RS.

HJM, van Herwaarden CLA. Do phys- pulmonary examination. J Gen Intern Diagnosis of bronchial asthma by clin-

ical signs reflect the degree of airflow Med 1986;1:364 7. ical evaluation. An unreliable method.

obstruction in patients with asthma or 66. Gjorup T, Bugge PM, Jensen AM. In- Chest 1983;84:427.

chronic obstructive pulmonary dis- terobserver variation in assessment of 81. Adelroth E, Hargreave FE, Ramsdale

ease? Scand J Prim Health Care 1991; respiratory signs. Acta Med Scand EH. Do physicians need objective

9:232 8. 1984;216:61 6. measurements to diagnose asthma?

52. Kern DG, Patel SR. Auscultated 67. OHagan JJ, Botting CH, Davies LJ. Am Rev Respir Dis 1986;134:704 7.

forced expiratory time as a clinical and The use of a simulated patient to assess 82. Hahn DL, Beasley JW, Wisconsin Re-

epidemiologic test of airway obstruc- clinical practice in the management of search Network (WReN) Asthma

tion. Chest 1991;100:636 9. a high risk asthmatic. N Z Med J 1989; Prevalence Study Group. Diagnosed

53. Schapira RM, Schapira MM, Funa- 102:252 4. and possible undiagnosed asthma: A

hashi A, et al. The value of the forced 68. Pratter MR, Curley FJ, Dubois J, Irwin Wisconsin Research Network (WReN)

expiratory time in the physical diagno- RS. Cause and evaluation of chronic Study. J Fam Pract 1994;38:3739.

sis of obstructive airways disease. dyspnea in a pulmonary disease center. 83. DePaso WJ, Winterbauer RH, Lusk

JAMA 1993;270:731 6. Arch Intern Med 1989;149:2277 82. JA, et al. Chronic dyspnea unexplained

54. Anderson CL, Shankar PS, Scott JH. 69. Schmitt BP, Kushner MS, Wiener SL. by history, physical examination, chest

Physiological significance of sterno- The diagnostic usefulness of the his- roentgenogram, and spirometry. Anal-

mastoid muscle contraction in chronic tory of the patient with dyspnea. J Gen ysis of a seven-year study. Chest 1991;

obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Intern Med 1986;1:386 93. 100:12939.

Care 1980;25:9379. 70. Holleman DR Jr, Simel DL, Goldberg 84. Speight ANP, Lee DA, Hey EN. Un-

55. Stubbing DG, Mathur PN, Roberts RS, JS. Diagnosis of obstructive airways derdiagnosis and undertreatment of

Campbell EJM. Some physical signs in disease from the clinical examination. asthma in childhood. Br Med J 1983;

patients with chronic airflow obstruc- J Gen Intern Med 1993;8:63 8. 286:1253 6.

tion. Am Rev Respir Dis 1982;125: 71. Badgett RG, Tanaka DJ, Hunt DK, et 85. Konig P. Hidden asthma in childhood.

549 52. al. Can moderate chronic obstructive Am J Dis Child 1981;135:10535.

56. Godfrey S, Edwards RHT, Campbell pulmonary disease be diagnosed by 86. National Asthma Education Program.

EJM, Newton-Howes J. Clinical and historical and physical findings alone? Expert Panel Report. Guidelines for

physiological associations of some Am J Med 1993;94:188 96. the Diagnosis and Management of

physical signs observed in patients 72. Badgett RG, Tanaka DJ, Hunt DK, et Asthma. U.S. Department of Health

with chronic airways obstruction. al. The clinical evaluation for diagnos- and Human Services. Public Health

10 ANNALS OF ALLERGY, ASTHMA, & IMMUNOLOGY

Service. National Institutes of Health. acute bronchial asthma. Ann Emerg Request for reprints should be addressed to:

Publication No. 91-3042. August Med 1982;11:64 9. James T C Li, MD

1991. 88. Connolly CK, Chan NS. Relationship Mayo Clinic & Foundation

87. Nowak RM, Pensler MI, Sarkar DD, et between different measurements of re- 200 First St, SW

al. Comparison of peak expiratory spiratory function in asthma. Respira- Rochester, MN 55905

flow and FEV1 admission criteria for tion 1987;52:2233.

CME Examination

Identification N 016-001

Questions 120, Li JTC and EJ OConnell. 1996;76:114.

CME Test Questions B. Only 5% of chest pain in 8. Which of the following lung

children is caused by sounds are called continuous

1. Which of the following chest asthma. adventitious sounds?

symptoms is most closely as- C. Chest pain is rarely de- A. Expiratory wheezes

sociated with congestive heart scribed in exercise-induced B. Inspiratory rales

failure? asthma. C. Expiratory rales

A. My breath does not go out D. Chest tightness is rarely de- D. Fine crackles

all the way. scribed in exercise-induced E. Coarse crackles

B. I cannot take a deep breath. asthma. 9. As a test of airway obstruc-

C. I feel wheezy. E. Lipid screening is recom- tion, a prolonged forced expi-

D. I feel that I am smothering. mended. ratory time has a sensitivity of

E. I cannot take a deep breath. 5. The prevalence of wheezing in about

2. What percentage of patients the general population is about A. 5% or less

with chronic obstructive pul- A. 5% or less B. 10% to 25%

monary disease admit to B. 10% to 25% C. 50% to 65%

wheezing? C. 50% to 65% D. 75% to 90%

A. 100% D. 75% to 90% E. 99%

B. 75% E. Prevalence studies of 10. Which of the following signs

C. 50% wheezing have not been is associated with obstructive

D. 25% conducted

lung disease?

E. 0% 6. Which of the following is as-

A. Decreased breath sound in-

3. Which of the following state- sociated with nearly fatal

tensity

ments about the symptom of asthma?

B. Tracheal tag

inspiratory dyspnea is true? A. Wheezing

B. Use of home peak flow di- C. Increased resonance to per-

A. Associated with increased cussion

ary

PEFR D. Pulsus paradoxus

C. Increased use of inhaled

B. Associated with decreased E. All of the above

nedocromil

RV/TLC ratio 11. When physicians evaluate pa-

D. Increased use of inhaled

C. Rarely described during a corticosteroids tients for unexplained dyspnea

positive methacholine E. Reduced chemosensitivity about what percentage of the

bronchial challenge to hypoxia time do they reach the correct

D. Rarely reported by patients 7. Which of the following char- diagnosis based on the medi-

experiencing acute asthma acteristics about wheezing is cal history and physical exam-

E. Reported by the majority of associated with increased air- ination?

patients experiencing acute way obstruction? A. 5% to 15%

asthma A. Wheezing during exercise B. 25% to 35%

4. Which of the following state- B. Low pitched wheezing C. 45% to 55%

ments about chest pain in chil- C. Low intensity wheezing D. 65% to 75%

dren is true? D. Wheezing during inspira- E. 95% to 100%

A. About 20% of chest pain in tion and expiration 12. Which of the following com-

children is caused by E. Wheezing with forced ex- ponents of the medical history

asthma. halation is an independent predictor of

VOLUME 76, JANUARY, 1996 13

obstructive lung disease in D. 60% to 70% of predicted lation (forced vital capacity

adults? normal values maneuver)

A. Fatigue E. 80% to 90% of predicted D. A drop in systolic blood

B. Exercise intolerance normal values pressure of 5 mm or greater

C. Significant smoking his- 16. Which of the following respi- during inspiration

tory ratory signs does not have a E. A drop in systolic blood

D. Chest pain statistically significant associ- pressure of 5 mm or greater

E. Family history of emphy- ation with FEV1 or PEFR? during a Valsalva maneu-

sema A. Breath sound intensity ver

13. Deliberate hyperventilation is B. Forced expiratory time 19. For adult patients with asthma

most likely to produce which C. Wheezing or suspected asthma, The Na-

of the following symptoms? D. Increased resonance to per- tional Asthma Education Pro-

A. I feel hunger for more air. cussion gram Expert Panel Report rec-

B. I cannot take a deep breath. E. Bibasilar fine crackles ommends spirometry

C. My chest feels tight. 17. All of the following have a A. For all patients, at initial

D. My breath does not go out statistically significant corre- assessment

all the way. lation with severe airway ob- B. For patients with moderate

E. My breathing requires or severe asthma only, at

struction except

more concentration. initial assessment

A. Wheezing throughout the

14. In children whose primary C. Every three months for pa-

respiratory cycle

symptom is chronic cough, tients with moderate or se-

B. Forced expiratory time

upper respiratory tract infec- vere asthma

tions trigger cough in what greater than two seconds D. Every six months for pa-

percentage of patients? C. Excavation of the supracla- tients with moderate or se-

A. 10% to 20% vicular fossa vere asthma

B. 30% to 40% D. Pulsus paradoxus E. Every six months for pa-

C. 50% to 60% E. Respiratory rate tients with severe asthma

D. 70% to 80% 18. The major finding in pulsus 20. For adult patients with known

E. 90% to 100% paradoxus is asthma, the National Asthma

15. When patients recovering A. A drop in systolic blood Education Program Expert

from acute asthma in the hos- pressure of 10 mm or Panel Report recommends

pital are studied, symptoms of greater during exhalation strong consideration of home

asthma disappear when pul- (normal tidal breathing) peak flow monitoring for

monary function is B. A drop in systolic blood A. All patients

A. 0% to 10% of predicted pressure of 10 mm or B. Patients with moderate and

normal values greater during inspiration severe asthma

B. 20% to 30% of predicted (normal tidal breathing) C. Patients with severe asthma

normal values C. A drop in systolic blood only

C. 40% to 50% of predicted pressure of 10 mm or D. Patients taking salmeterol

normal values greater during forced exha- E. Patients taking nedocromil

14 ANNALS OF ALLERGY, ASTHMA, & IMMUNOLOGY

Instructions for Category I CME Credit

Certification. As an organization Medical Education, which can be erase but do so completely in order to

accredited for continuing medical ed- found after the examination. prevent computer reading errors. Your

ucation, the American College of Please record your ACAAI identifi- ACAAI identification number and quiz

Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology cation number and the quiz identifica- identification number will be used to

(ACAAI) certifies that when the tion number in the spaces and scanning record your credit hours earned on the

CME material is used as directed it targets provided on the answer sheet. CME transcript system. No records of

meets the criteria for two hours Your ACAAI identification number individual performance will be main-

credit in Category I of the American can be found on your ACAAI mem- tained.

Tear out the perforated answer sheet

College of Allergy, Asthma, & Im- bership card, nonmembers of the Col-

and print your name and address in the

munology CME Award and the Phy- lege will be assigned an ACAAI iden- spaces provided. Return it within one

sicians Recognition Award of the tification number and this should be month after the Annals is received to

American Medical Association. left blank on the answer sheet. The the American College of Allergy,

Instructions. Category I credit can quiz identification number can be Asthma, & Immunology, 85 West Al-

be earned by reading the text material, found at the beginning of the CME gonquin Rd, Suite 550, Arlington

taking the CME examination and re- examination. Heights, IL 60005. Answers will be

cording the answers on the perforated Use a No. 2 or soft lead pencil for published in the next issue of the An-

answer sheet entitled, Continuing marking the answer sheet. You may nals of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology.

Answers to CME examinationAnnals of Allergy,

Asthma, & Immunology, December 1995 (Identification

No 015-012) Spector SL. Leukotriene inhibitors and an-

tagonists in asthma. Ann Allergy, Asthma, & Immunol

1995; 75:46374.

1. d 6. e 11. b 16. a

2. c 7. c 12. e 17. c

3. b 8. a 13. d 18. a

4. a 9. d 14. b 19. c

5. e 10. e 15. d 20. b

VOLUME 76, JANUARY, 1996 15

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Basic Reconnaissance Course Preparation GuideDokumen6 halamanBasic Reconnaissance Course Preparation GuideJohn Leclair100% (1)

- Psycho Dynamic Psychotherapy For Personality DisordersDokumen40 halamanPsycho Dynamic Psychotherapy For Personality DisorderslhasniaBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- All Other ClassificationsDokumen6 halamanAll Other ClassificationsCorey100% (1)

- School Threat AssessmentDokumen12 halamanSchool Threat AssessmentChelsea ElizabethBelum ada peringkat

- The Holy Grail of Curing DPDRDokumen12 halamanThe Holy Grail of Curing DPDRDany Mojica100% (1)

- Project WorkPlan Budget Matrix ENROLMENT RATE SAMPLEDokumen3 halamanProject WorkPlan Budget Matrix ENROLMENT RATE SAMPLEJon Graniada60% (5)

- CBLM-BEAUTY CARE - FinalDokumen75 halamanCBLM-BEAUTY CARE - FinalQuimby Quiano100% (3)

- TOFPA: A Surgical Approach To Tetralogy of Fallot With Pulmonary AtresiaDokumen24 halamanTOFPA: A Surgical Approach To Tetralogy of Fallot With Pulmonary AtresiaRedmond P. Burke MD100% (1)

- Calculating IV Fluid Volume and Drip RateDokumen3 halamanCalculating IV Fluid Volume and Drip RateCoreyBelum ada peringkat

- Rationale: This Will Assess Pain LevelDokumen7 halamanRationale: This Will Assess Pain LevelCoreyBelum ada peringkat

- Hypospadias and Epispadias 1Dokumen35 halamanHypospadias and Epispadias 1Corey100% (1)

- TtyygDokumen1 halamanTtyygCoreyBelum ada peringkat

- TtyygDokumen1 halamanTtyygCoreyBelum ada peringkat

- ENOXAPRINDokumen4 halamanENOXAPRINCoreyBelum ada peringkat

- Assessment 2Dokumen49 halamanAssessment 2CoreyBelum ada peringkat

- Acute Injury NewDokumen29 halamanAcute Injury NewCoreyBelum ada peringkat

- Explain 15 Guidelines For The Administration of Any Drug, Paying Special Attention To MCMH Drug PoliciesDokumen1 halamanExplain 15 Guidelines For The Administration of Any Drug, Paying Special Attention To MCMH Drug PoliciesCoreyBelum ada peringkat

- Course: Topic Audience Level Venue Date: Duration: Methodology Teaching AidsDokumen5 halamanCourse: Topic Audience Level Venue Date: Duration: Methodology Teaching AidsCoreyBelum ada peringkat

- Morissa Pharmacology AssignmentDokumen2 halamanMorissa Pharmacology AssignmentCoreyBelum ada peringkat

- SVG Nursing Lesson Plan on Bronchitis MedicationsDokumen4 halamanSVG Nursing Lesson Plan on Bronchitis MedicationsCoreyBelum ada peringkat

- My Country My PrideDokumen1 halamanMy Country My PrideCoreyBelum ada peringkat

- Name: Dondre Hillocks Subject: Mathematics Teacher: Date Due: 16 October, 2017Dokumen16 halamanName: Dondre Hillocks Subject: Mathematics Teacher: Date Due: 16 October, 2017CoreyBelum ada peringkat

- Physical Assessment - Page 1Dokumen4 halamanPhysical Assessment - Page 1CoreyBelum ada peringkat

- Morissa Pharmacology AssignmentDokumen2 halamanMorissa Pharmacology AssignmentCoreyBelum ada peringkat

- Lateral SMASectomy FaceliftDokumen8 halamanLateral SMASectomy FaceliftLê Minh KhôiBelum ada peringkat

- List of 220KV Grid Stations-NTDCDokumen7 halamanList of 220KV Grid Stations-NTDCImad Ullah0% (1)

- Antiparkinsonian Drugs Pathophysiology and TreatmentDokumen5 halamanAntiparkinsonian Drugs Pathophysiology and Treatmentkv 14Belum ada peringkat

- Setons in The Treatment of Anal Fistula Review of Variations in Materials and Techniques 2012Dokumen9 halamanSetons in The Treatment of Anal Fistula Review of Variations in Materials and Techniques 2012waldemar russellBelum ada peringkat

- Appointments Boards and Commissions 09-01-15Dokumen23 halamanAppointments Boards and Commissions 09-01-15L. A. PatersonBelum ada peringkat

- Overcoming The Pilot Shortage PDFDokumen16 halamanOvercoming The Pilot Shortage PDFTim ChongBelum ada peringkat

- Declaration of Erin EllisDokumen4 halamanDeclaration of Erin EllisElizabeth Nolan BrownBelum ada peringkat

- Assessmen Ttool - Student AssessmentDokumen5 halamanAssessmen Ttool - Student AssessmentsachiBelum ada peringkat

- Ekstrak Kulit Buah Naga Super Merah Sebagai Anti-Kanker PayudaraDokumen5 halamanEkstrak Kulit Buah Naga Super Merah Sebagai Anti-Kanker PayudaraWildatul Latifah IIBelum ada peringkat

- Nematode EggsDokumen5 halamanNematode EggsEmilia Antonia Salinas TapiaBelum ada peringkat

- Theoretical Models of Nursing Practice AssignmentDokumen6 halamanTheoretical Models of Nursing Practice Assignmentmunabibenard2Belum ada peringkat

- 15.1 - PH II - Leave Rules-2019Dokumen40 halaman15.1 - PH II - Leave Rules-2019Ranjeet SinghBelum ada peringkat

- 2022-03-15 Board of Supervisors - Full Agenda-2940Dokumen546 halaman2022-03-15 Board of Supervisors - Full Agenda-2940ShannanAdamsBelum ada peringkat

- Ethical Counselling and Defense MechanismsDokumen9 halamanEthical Counselling and Defense MechanismscklynnBelum ada peringkat

- English in Nursing 1: Novi Noverawati, M.PDDokumen11 halamanEnglish in Nursing 1: Novi Noverawati, M.PDTiara MahardikaBelum ada peringkat

- Work Authorization Permit.Dokumen1 halamanWork Authorization Permit.Gabriel TanBelum ada peringkat

- Challenges of Caring for Adult CF PatientsDokumen4 halamanChallenges of Caring for Adult CF PatientsjuniorebindaBelum ada peringkat

- Certification of Psychology Specialists Application Form: Cover PageDokumen3 halamanCertification of Psychology Specialists Application Form: Cover PageJona Mae MetroBelum ada peringkat

- Stok Benang Kamar OperasiDokumen5 halamanStok Benang Kamar OperasirendyBelum ada peringkat

- The Effectiveness of Community-Based Rehabilitation Programs For Person Who Use Drugs (PWUD) : Perspectives of Rehabilitation Care Workers in IloiloDokumen27 halamanThe Effectiveness of Community-Based Rehabilitation Programs For Person Who Use Drugs (PWUD) : Perspectives of Rehabilitation Care Workers in IloiloErikah Eirah BeloriaBelum ada peringkat

- BSc Medical Sociology Syllabus DetailsDokumen24 halamanBSc Medical Sociology Syllabus Detailsmchakra72100% (2)

- Drug Study Kalium DuruleDokumen2 halamanDrug Study Kalium DuruleGrant Kenneth Dumo AmigableBelum ada peringkat