Chalmers 2016

Diunggah oleh

Jaya Semara PutraHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Chalmers 2016

Diunggah oleh

Jaya Semara PutraHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

876

The Modern Diagnostic Approach to

Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults

James D. Chalmers, MBChB, PhD, FRCPE1

1 Scottish Centre for Respiratory Research, University of Dundee, Address for correspondence James D. Chalmers, MBChB, PhD, FRCPE,

Dundee, United Kingdom Scottish Centre for Respiratory Research, University of Dundee,

Dundee DD1 9SY, United Kingdom (e-mail: j.chalmers@dundee.ac.uk).

Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2016;37:876885.

Abstract Respiratory tract infections, the majority of which are community acquired, are among

the leading causes of death worldwide and a leading indication for hospital admission.

The burden of disease demonstrates a U-shaped distribution, primarily affecting

Downloaded by: State University of New York at Stony Brook. Copyrighted material.

young children as the immune system matures, and older adults as the process of

immunosenescence and accumulation of comorbidities leads to increased susceptibility

to infection. Diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is traditionally based

on demonstration of a new inltrate on a chest radiograph in a patient presenting with

an acute respiratory illness or sepsis. Advances in diagnosis have been slow, and

although there are increasing data on the value of computed tomography or lung

ultrasound as more sensitive diagnostic methodologies, they are not widely used as

Keywords initial diagnostic tests. There are a wide range of differential diagnoses and pneumonia

chest radiograph mimics which should be considered in patients presenting with CAP. Once the

community-acquired diagnosis of CAP has been made, identifying the causative microorganism is the next

pneumonia stage in the diagnostic process. Traditional culture-based approaches are relatively

epidemiology insensitive and achieve a positive diagnosis in only 30 to 70% of cases, even when

microbiology rigorously applied. Urinary antigen tests, polymerase chain reaction assays, and even

polymerase chain next-generation sequencing technologies have become available and are increasing the

reaction rates of positive diagnosis. In an era of increasing antimicrobial resistance, the accurate

risk factors diagnosis of CAP and determining the causative pathogen are ever more important.

Streptococcus Getting these both right is key in reducing both morbidity and mortality from CAP, and

pneumoniae appropriate antimicrobial stewardship which is now an international healthcare priority.

Acute respiratory tract infections are the leading cause of Determining the precise impact of community-acquired

death in developing countries, while remaining a leading pneumonia (CAP) worldwide is made more difcult by the

cause of death in developed nations.1,2 The Global Burden of use of a denition that relies on chest radiographic evidence

Disease study revealed that the number of deaths from acute of consolidation.35 It is estimated that up to 80% of episodes

respiratory tract infections has fallen over the past two of CAP in developed countries are treated without the patient

decades. Nevertheless, respiratory infections will continue ever receiving a chest X-ray. In developing nations, this

to have a profound impact worldwide.1,2 The exact preva- proportion will be higher still.57

lence of acute respiratory tract infections worldwide is nearly Whether in primary care or in the hospital setting, CAP

impossible to calculate, but there are an estimated 4 million must be quickly recognized and treated, as severe CAP can be

deaths per year, with up to three-fourths of those deaths life threatening.8 In the emergency setting, prompt resusci-

being in children younger than 5 years. tation and administration of intravenous antibiotics are

Issue Theme Community-Acquired Copyright 2016 by Thieme Medical DOI http://dx.doi.org/

Pneumonia: A Global Perspective; Guest Publishers, Inc., 333 Seventh Avenue, 10.1055/s-0036-1592125.

Editors: Charles Feldman, MBBCh, DSc, New York, NY 10001, USA. ISSN 1069-3424.

PhD, FRCP, FCP (SA), and James D. Tel: +1(212) 584-4662.

Chalmers, MBChB, PhD, FRCPE

Modern Diagnostic Approach to CAP in Adults Chalmers 877

essential steps in reducing the morbidity and mortality from identied bacterial pathogen or in those without an identi-

CAP which stands at 5 to 15% for hospitalized patients and ed bacteria.22 Fungi are not, thus far, identied as a common

often >25% for patients requiring admission to an intensive cause of CAP in immunocompetent adults.

care unit.810 In this context, CAP must be differentiated from In contrast, the causative pathogens in HAP are most

other conditions causing acute respiratory failure and septic frequently organisms such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus,

shock. In the less acute setting, in outpatients or in primary P. aeruginosa, and Enterobacteriaceae with atypical patho-

care, the challenge is more to differentiate patients with CAP gens being rare.17,19

who may benet from antibiotic therapy from that much This classical dichotomy hides a much greater degree of

larger group of patients with acute cough who will not benet complexity. Among patients with CAP, there are patients with

from antibiotic therapy.5,7,11,12 few comorbidities who are at very low risk of antibiotic-

Once the diagnosis of CAP has been made, antibiotic resistant pathogens and are most likely to have pneumococcal

treatment is commenced according to the severity of disease or atypical pneumonia.16,17 In contrast, among elderly

and to cover the most likely causative pathogens.13,14 Testing patients and those with comorbidities, atypical pathogens

to determine the possible causative pathogen serves several are uncommon, but the incidence of Enterobacteriaceae and

important functions which include (1) to deescalate initial P. aeruginosa increases sharply.23,24 Other groups deserve

broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment if a pathogen is identi- special mention. Patients with human immunodeciency

ed that can be treated with narrower spectrum therapy,15 virus (HIV) and those with other forms of immunosuppres-

Downloaded by: State University of New York at Stony Brook. Copyrighted material.

(2) to identify unusual or drug-resistant pathogens that will sion may be at risk of opportunistic pathogens not typically

not be covered by the initial empirical regime,16 and (3) to considered in CAP therapy.25 This leads many authors to

provide local data on the frequency of different causative suggest that CAP with immunosuppression should be

pathogens and antibiotic resistance rates that can be used to regarded as a separate clinical entity.26 Patients with HIV

guide future empirical treatment guidelines.17 are at signicantly increased risk of CAP, but in the era of

The goal of this review is to discuss the diagnostic highly active antiretroviral therapy, the most frequent

approach in CAP, with a focus on how to make the initial etiological agent is S. pneumoniae, as with CAP not associated

diagnosis and the emerging methods for determining the with HIV. Pneumocystis jirovecii is the most frequent etiology

underlying pathogen. in patients with a CD4 count <200/mm3.25,27

Similarly, the lines between community and hospital are

increasingly blurred, as the population ages and health care is

What Is Community-Acquired Pneumonia?

delivered increasingly in the community. Nursing-homeac-

By convention, pneumonia is an acute respiratory illness quired pneumonia (NHAP) has been proposed as a separate

associated with a new inltrate on the chest radiograph.13 entity, but at least in Europe there is little evidence that they

In practice, pneumonia is an extremely heterogeneous clini- require different empirical therapy.28 A study from Germany

cal disorder. While many patients present with classic symp- compared 518 patients with NHAP and 2,569 CAP patients and

toms of a combination of cough, sputum production, found only minor differences in etiologywith more S. aureus

breathlessness, fever, and pleuritic chest pain, many patients and less atypical pathogens in the NHAP group. Differences in

do not. Particularly in the elderly, fever may be absent, and outcome were due to worse functional status and comorbidities

pneumonia may present with episodes of decreased mobility, in NHAP rather than differences in bacteriology.28,29 Similar

delirium, acute cardiac disorders (such as new-onset atrial results have been reported from Spain and elsewhere.28,29

brillation), or abdominal pain without obvious respiratory The concept of healthcare-associated pneumonia was pro-

symptoms.18 Pneumonia is the most common cause of com- posed in 2005 by the IDSA/ATS HAP/VAP guidelines as a means of

munity-acquired sepsis along with urinary tract infections dealing with this increasing complexity.17,19 Their proposal to

and should be considered in all patients presenting with the treat patients from nursing homes, those with prior hospitaliza-

clinical syndrome of sepsis. tion or prior antibiotic treatment, and other risk factors as HAP

Pneumonia is divided into community and hospital patients led to 20 to 30% of those previously regarded as CAP

acquired.17 Arbitrarily, hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) being treated with broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy.19,30,31

is considered to be present if pneumonia developed >48 Recent data from the United States suggests that approximately

hours after admission to a hospital or healthcare environ- 30% of CAP is now being treated with anti-MRSAdirected

ment, with all other cases of pneumonia being considered therapy, despite the prevalence of MRSA being approximately

community acquired.19 The causative pathogens in CAP are 1% in this group.19,30,31 There is a consensus that while the

typically upper respiratory tract commensals and include healthcare associated pneumonia (HCAP) criteria represent risk

Gram-positive organisms (most frequently Streptococcus factors for a different spectrum of pathogens, they did not

pneumoniae, and also Staphylococcus aureus), gram-negative function as a method of selecting empirical antibiotic treatment,

organisms (most frequently Haemophilus inuenzae, and less leading to overtreatment.19,23,26,32 Revision of this guidance is

frequently Moraxella catarrhalis and the Enterobacteriaceae currently underway.

or Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and the atypical pathogens Thus, the classication of pneumonia remains into CAP and

(including Legionella pneumophila, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, HAP, but recognizes that within CAP there are subgroups of

and others).20,21 Viruses are increasingly recognized as the patients who will require additional investigation and consider-

cause of CAP, and may be detected in patients with an ation of a different spectrum of causative pathogens (Fig. 1).

Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine Vol. 37 No. 6/2016

878 Modern Diagnostic Approach to CAP in Adults Chalmers

A systematic review of the use of lung ultrasound for

diagnosis of CAP in adults concluded it has a sensitivity of 95%

and specicity of 90%, and that based on a nal discharge

diagnosis of CAP, it therefore had a superior sensitivity and

similar specicity to chest X-ray.42 A multicenter study by

Reissig et al studied 229 patients with CAP. They found a

sensitivity of 93% and specicity of 98% but crucially found

that approximately 8% of pneumonic lesions were not visible

on ultrasound, indicating that lung ultrasound cannot be

considered to exclude CAP.43

A further recent systematic review and meta-analysis of

1,172 patients investigated with ultrasound suggested the pro-

cedure took approximately 13 minutes to perform and had a

Fig. 1 Classication of pneumonia. CAP, community-acquired pneu- sensitivity of 94% and specicity of 96%, therefore comparing

monia; HAP, hospital acquired pneumonia; MDR, multidrug resistant; favorably with alternative tests.44 Studies were performed by

NHAP, nursing-homeacquired pneumonia. highly skilled and trained sonographers, therefore limiting the

applicability of this data beyond expert settings.

Downloaded by: State University of New York at Stony Brook. Copyrighted material.

Therefore in future, the diagnostic pathway for CAP may

The risk factors for multidrug-resistant pathogens are include chest CT and/or thoracic ultrasound.

dealt with more extensively in another review in this series Several common and uncommon disorders can present

but are strongly linked to age; multimorbidity; comorbidities initially with suspected CAP and an awareness of these

such as respiratory disease, dementia, and renal failure; and possible alternative diagnoses is essential. These are summa-

antibiotic use.3335 rized in Table 1.

The possibility of lung malignancy should be particularly

considered in all patients presenting with CAP. Up to 10% of

Diagnosis of CAP in the Hospital Setting

CAP patients admitted to hospital will be ultimately diag-

As described previously, in practical terms CAP should be nosed with pulmonary malignancy.52,61,62 In a cohort study

diagnosed in patients with acute respiratory symptoms and a in Canada of 3,398 patients, lung cancer was diagnosed in 1%

new consolidation on the chest radiograph. In practice, of patients at 12 months.62 Lung cancer was most frequent in

diagnosis is challenging and misdiagnosis is common.3 The patients older than 50 years, male patients, and smokers.62 In

gold standard is the detection of microorganisms in lung a cohort study of 40,744 patients with CAP, Mortensen and

tissue, which is not practical and not available in the emer- colleagues demonstrated that the most important risk factors

gency department. were a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

When accuracy of chest radiographs for diagnosis of (COPD), prior malignancy, white race, and tobacco use.62

pneumonia has been evaluated, the agreement between The diagnosis should be considered in all patients, but

clinicians and radiologists, or between two radiologists, is particularly in those older than 50 years and with a history

often poor.36,37 A recent study by Claessens et al has claried of cigarette smoking.

these difculties in diagnosis.38 The French study examined

319 patients with suspected CAP by chest radiograph and

Diagnosis of CAP in Primary Care

chest computed tomography (CT).38 The results revealed a

remarkable level of disagreement between X-ray, CT, and In the community, diagnosis is even more challenging where

clinical evaluation. In summary one-third of patients with a the majority of acute respiratory infections are not investi-

normal chest X-ray had an inltrate on CT, and excluded gated by chest X-ray.63 Even where chest X-rays are per-

CAP in 30% of patients with an apparent chest X-ray inl- formed, diagnosis may be missed. In a study of 12 European

trate.38 Using CT as the gold standard, the diagnostic decision countries, 3% of 1,885 patients with lower respiratory tract

was changed in nearly 60% of cases. infection (LRTI) not thought to be pneumonia had chest X-ray

Unfortunately, routine use of CT for the diagnosis of evidence of pneumonia on independent radiology review.5

pneumonia is unlikely to be widely available in the near Biomarkers can assist in the diagnostic pathway. In a study

future. Chest X-ray will remain the standard investigation. in 12 European countries of 2,820 patients with LRTIs, where

Nevertheless, as a result of this and other studies, it is X-rays were performed, 140 (5%) had pneumonia. Clinical

important to question the diagnosis of CAP, particularly features had a moderate ability to identify pneumonia, where

when X-ray is equivocal, and to reevaluate the accuracy of pneumonia was more frequent with the absence of a runny

the diagnosis if patients do not respond to treatment as nose, the presence of breathlessness, crackles, diminished

expected.39 breath sounds on auscultation, tachycardia, and fever. Addi-

Lung ultrasound has been proposed as an alternative, and tion of C-reactive protein (CRP) > 30 mg/L to this model

is attractive because ultrasound has become a routine skill for greatly improved the diagnostic accuracy (from area under

respiratory physicians in the management of pleural the curve 0.70 to 0.77).64 Procalcitonin (PCT) did not help in

disease.4042 the diagnosis in this model.64

Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine Vol. 37 No. 6/2016

Modern Diagnostic Approach to CAP in Adults Chalmers 879

Table 1 Differential diagnoses of community-acquired pneumonia in patients presenting to hospital or the emergency department

Diagnosis Radiological features Clinical features

Common

Acute bronchitis47 No X-ray changes Acute cough, without evidence of sepsis. May be

a viral prodrome or accompanying viral

symptoms

Exacerbation Hyperination and chronic changes but no History of COPD, cough, sputum, and breath-

of COPD48 consolidation lessness with wheeze on examination

Exacerbation May be hyperination, but no consolidation History of asthma, cough, breathlessness,

of asthma49 wheeze. May be accompanied by viral prodrome

Exacerbation of Often normal, mucus plugging may lead to Cough, sputum, breathlessness, chest pain,

bronchiectasis50 opacities suggesting pneumonia fever, and malaise. Past history of bronchiectasis

Cardiac failure and Cardiomegaly, pleural effusions, alveolar Orthopnea, Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea,

pulmonary edema51 opacities (classically perihilar) upper lobe ankle edema, absence of sepsis. Response to

venous diversion diuretics and nitrates. Often a past history of

cardiac failure or cardiac disease. Elevated

Downloaded by: State University of New York at Stony Brook. Copyrighted material.

cardiac biomarkers but low inammatory

markers

Lung cancer/malignancy Multiple possible imaging features Lack of inammatory response, chronic

including lymphoma52 symptoms, associated red ag symptoms

(weight loss/hemoptysis)

Nonrespiratory Severe sepsis from any source, e.g., UTI, intra- Initial history lacking in respiratory symptoms,

sepsis53 abdominal, pancreatitis can be associated with clinical indicators of sepsis outside the respira-

consolidation (often bilateral) tory tract. Isolation of pathogens not usually

associated with CAP

Pulmonary embolism54 Atelectasis, pleural effusion, elevated Difcult to differentiate clinically. Prominent

diaphragm, Westermark sign, unilateral or hypoxemia, pleuritic chest pain, collapse/syn-

bilateral opacities cope. Clinical evidence of DVT usually absent

Uncommon

Acute interstitial Appearances similar to ARDS Short history (often 12 wk) cough, sputum,

pneumonia55 fever and progressive breathlessness

Cryptogenic organizing Reversed halo sign, itting shadows over Relatively chronic course (usually >1 mo)

pneumonia56 time, concave opacities

Chronic eosinophilic Bilateral nonsegmental consolidation with Subacute or chronic presentation. Peripheral

pneumonia57 peripheral predominance pulmonary inltrates. Eosinophilia (peripheral or

on BAL). More common in females than in males

Acute eosinophilic Diffuse radiographic inltrates Often occurs in young adults. Peripheral blood

pneumonia58 eosinophilia

Lipoid pneumonia59 Presence of fat within consolidation on CT Nonspecic presentationDyspnea and cough

60

Tuberculosis Upper lobe changes, cavitation Chronic course, absence of sepsis, hemoptysis,

weight loss, night sweats

Abbreviations: ARDS, adult respiratory distress syndrome; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Note: The list is no exhaustive but gives examples of differential diagnoses.

Patients with radiologically proven pneumonia appear to Since X-ray is impractical in terms of detecting pneumonia

derive benet from antibiotic treatment. In a 12-country in primary care on a routine basis, alternatives are needed.

randomized controlled trial of amoxicillin for LRTI in primary Current guidance recommends the use of point-of-care CRP

care (n 1,038 Amocillin, n 1,023 placebo), there was no testing as an alternative.66 Randomized controlled trials show

impact of antibiotics on duration of symptoms or symptom that use of CRP can reduce antibiotic use for LRTI without

severity with the antibiotic treatment.65 Nevertheless, in a adverse effects.67,68 A cluster randomized controlled trial in

post hoc analysis of patients subsequently found to have the Netherlands showed that CRP could reduce to half with

radiological pneumonia, patients with X-ray changes treated rate of antibiotic prescription. Recommended cutoffs vary,

with antibiotics had a more rapid resolution of symptoms and but studies suggest a cutoff of 30 mg/L is most accurate to

lower severity of symptoms.5 predict pneumonia.6770

Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine Vol. 37 No. 6/2016

880 Modern Diagnostic Approach to CAP in Adults Chalmers

Thus, in primary care a combination of clinical history, A total of 2,488 patients were enrolled of which 2,320 had

markers of severity such as the CRB65 scoring system,71,72 radiographic pneumonia. The study enrolled predominantly

and the use of point-of-care CRP testing where available is milder CAP patients, with an average age of 57 and 65% of

most effective in identifying those patients requiring antibi- patients being in pneumonia severity index risk classes 1 to 3,

otic treatment. where patients would normally be treated as outpatients.83

Extensive etiological testing revealed a pathogen in 38%, with

viruses being more frequent than bacteria. Rhinovirus was

CAP Pathogens and Diagnostic Tests

most frequently detected in 9% of patients, inuenza in 6% and

Once a diagnosis of CAP is made and empirical therapy is S. pneumoniae in 5%.75 Other pathogens were infrequent

being considered or has been administered, the diagnostic (Fig. 2). These data suggest that viral infections may be

process moves toward determining the underlying causative more frequent than bacteria in mild CAP in the United States.75

pathogen. Routine use of microbiological investigations in Coinfection is common across several studies.84 The pres-

primary care is generally not recommended due to the low ence of a viral infection does not imply the absence of

rate of true pneumonia among such patients. Nevertheless, it bacterial infection in patients with CAP.

is known that the spectrum of pathogens in outpatients is Most empirical regimes cover both typical and atypical

very similar to those in inpatients.7274 pathogens and this is appropriate because studies suggest

There is some variation globally in the proportions of that atypical organisms are common throughout the

Downloaded by: State University of New York at Stony Brook. Copyrighted material.

different pathogens reported as the causes of CAP, but in world.17,66 A study by Arnold et al identied rates of atypical

general the list of pathogens is remarkably consistent.16,7578 pathogens to be 22% in North America, 28% in Europe, 21% in

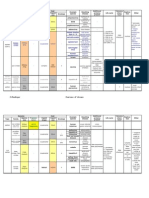

In Fig. 2, we select representative cohort studies from North Latin America, and 20% in Africa, justifying the universal use

America, South America, Northern Europe, Southern Europe, of atypical coverage.85 Even in outpatients or patients in

Asia, and Australasia, and demonstrate that the predominant primary care, it is common to identify atypical organisms

pathogens are broadly similar.7578 S. pneumoniae remains and particularly M. pneumoniae.86 Consistent observational

the most frequently isolated bacterial pathogen in CAP across data suggest that the addition of macrolide to -lactam

the world which is why it is a focus of vaccination efforts.79,80 therapy provides benets in terms of reduced time to clinical

Approximately one-third of patients with pneumococcal stability and reduced mortality compared with -lactam

pneumonia will have bacteremia.81 It is controversial alone.87,88 These data are the basis of international guideline

whether bacteremia is associated with worse outcomes, recommendations to use atypical coverage in all inpatients,

and recent data suggest that bacteremic infection may have and particularly in patients with severe pneumonia.17,66

different clinical characteristics but similar outcomes.81,82 In some geographical regions, the distinction between

The recent Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community typical bacterial pneumonia and Mycobacterium tuberculosis

(EPIC) study supported by the Centers for Disease Control (MTb) infection can be difcult, leading to MTb being listed as a

and Prevention in the United States has provided a clearer cause of CAP. The CDC has listed 22 risk factors that can identify

view of the etiology of CAP in North America.75 The study was patients at high risk of MTb infection, and in patients with

conducted at ve hospitals in Nashville, TN, and Chicago, IL.75 suspected CAP, the 5 strongest risk factors were night sweats,

weight loss, hemoptysis, prior exposure to MTb, and upper

lobe inltrates, all these being classical of TB infection.89

Diagnostic testing for the underlying cause is directed

against a range of pathogens most likely to be identied, or

less common pathogens that would nevertheless change

treatment such as the atypical organisms or multidrug-

resistant organisms.90,91

Standard Cultures and Urinary Antigen Testing

Conventional culture-based microbiology is still the mainstay

of microbiological diagnosis. Most international CAP guide-

lines recommend blood cultures for patients on admission to

hospital, ideally prior to antibiotic treatment.17,66 Sputum

culture is recommended in expectorating patients. Some

guidelines such as the British Thoracic Society guidelines in

the United Kingdom and subsequent NICE update recommend

omitting microbiological investigations in patients with mild

pneumonia.66 This has potential advantages in terms of reduc-

ing costs, but has limitations in terms of identifying local

microbiology patterns and also initial assessment of severity

Fig. 2 Representative frequency of pathogens across global CAP

of disease is often unreliable. Most guidelines internationally

cohorts. 12,7578 Cohort were selected as being prospectively enrolled suggest blood and sputum cultures in those patients to be

with standardized testing for organisms. treated as inpatients and this is the authors practice as well.

Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine Vol. 37 No. 6/2016

Modern Diagnostic Approach to CAP in Adults Chalmers 881

Sputum cultures are most likely to be positive in patients Rello et al evaluated DNA load, based on quantitative PCR,

with chronic respiratory diseases such as COPD, bronchiecta- in blood from patients with pneumococcal pneumonia and

sis, and asthma.92,93 Studies based largely on sputum cultures demonstrated a clear relationship between DNA load and

will report high frequencies of H. inuenzae, M. catarrhalis, and septic shock, a nding that has been conrmed in two other

P. aeruginosa for this reason, while studies based on alternative studies where DNA load correlated with severity markers in

diagnostic tests will report these organisms less frequently as pneumonia.109

they are less commonly identied in the blood.9295 Therefore, PCR assays targeting S. pneumoniae are more

Urinary antigen testing for S. pneumoniae and L. pneumo- sensitive than culture and are not limited by the requirement

phila has become standard care in many hospitals in the for organisms to be viable and therefore for samples to be

United States, Europe, and internationally.17,66 taken prior to antibiotic treatment, and preliminary evidence

Urinary antigen testing for L. pneumophila is well estab- suggests quantication could provide valuable prognostic

lished and has a sensitivity of 75 to 80% and a specicity information. This has not yet entered clinical practice but

approaching 100%. The limitation is that existing tests iden- holds some promise.

tify only L. pneumophila serogroup 1.96

Emerging Technologies

Detection of Viruses and Atypical Organisms

Atypical pathogens have characteristic clinical features, for Although microbiome sequencing has been successfully applied

Downloaded by: State University of New York at Stony Brook. Copyrighted material.

example, hyponatremia, abnormal liver function tests, diarrhea, to chronic respiratory diseases using sputum and bronchoalveo-

and very high levels of CRP in L. pneumophila infection.97,98 None lar lavage, there are limited data in CAP patients.112114 This

of the clinical prediction tools or individual clinical character- technology that sequences all of the bacterial species present in a

istics are sufciently sensitive or specic to be used to guide sample has potential, but is unlikely to reach routine clinical

antibiotic treatment. Therefore, all patients should be considered practice due to the bioinformatics challenges associated with

for testing for atypical pathogens. Detection of rising IgM anti- analysis of the huge datasets.

body titers to M. pneumoniae, L. pneumophila, and other atypical

pathogens has been long recommended in guidelines, but

Biomarkers to Guide Diagnosis and

reported sensitivity is only 30 to 60% and can only be determined

Antibiotic Treatment

retrospectively.97,98 It is therefore not useful to guide treatment.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is now the treatment of choice Biomarkers have a limited role in the diagnosis of CAP as none

for detection of all atypical pathogens in throat or lower of them are specic for pneumonia, as they are raised in other

respiratory tract samples.99,100 causes of systemic bacterial infection.115 Nevertheless, CRP is

Viral diagnostics are increasingly used. Their value is in raised in the majority of patients with CAP.45 White blood cell

identifying patients who may benet from antiviral treat- count is unhelpful, asalthough it is often raisedit is

ment such as neuraminidase inhibitors (while recognizing nonspecic.

the current controversy over the effectiveness or otherwise of PCT has been the most intensively studied as a marker that

these drugs) and for isolation of potential infectious is rapidly upregulated in the presence of bacterial infection or

patients.101103 Diagnostic immunoassays are available for inammatory cytokines including interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6,

use in throat swabs, sputum, and bronchoalveolar lavage. and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-.115 Viral infections do not

Reported sensitivity ranges from 40 to 70%, indicating that a generate a strong PCT response leading to the suggestion that

negative assay cannot rule out the presence of inuenza. PCR PCT can be used to identify infections likely to respond to

is the test of choice with a higher sensitivity and specicity, antibacterial treatment. Several trials have been conducted

and multiplex assays are available covering the majority of comparing biomarker-guided treatment with standard care.

clinically important respiratory viruses. Differential inuenza In the largest of these, the ProHOSP study conducted in

virokinetics across the respiratory tract means that samples Switzerland, an algorithm comparing PCT with standard

can be negative in nasopharyngeal or throat swabs but may care (N 1,381) resulted in a reduction in antibiotic use of

be subsequently positive on sputum or bronchoalveolar 35% while being noninferior in terms of clinical outcomes.116

lavage samples. As a result, lower respiratory tract samples The study included patients with a range of respiratory tract

should be preferred.104106 infections. The impact in the subgroup with CAP (N 460

randomized to PCT and 465 randomized to standard care)

PCR for Streptococcus pneumoniae, Including was that 10% of CAP patients could be managed without

Assessment of Bacterial Load antibiotics, with a reduction in duration of therapy in a total

Studies have shown a higher sensitivity of PCR for detection of of 3.5 days.116

S. pneumoniae in sputum compared with conventional Limitations include that the duration of antibiotic treat-

culture.107 Studies have generally used primers directed at ment reported in the control arm was long (10 days on

the specic pneumolysin or LytA genes.107110 Reasons for average) and might have been reduced with a simple antibi-

improved sensitivity likely relate to the poor survival of otic stewardship program rather than a biomarker interven-

S. pneumoniae in sputum samples and the fact that PCR can tion, and second that the greatest value of PCT was in early

detect nonviable S. pneumoniae and other bacteria and so is discontinuing of antibiotics rather than the initial diagnostic

not affected by prior antibiotic treatment.107111 decision.117,118

Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine Vol. 37 No. 6/2016

882 Modern Diagnostic Approach to CAP in Adults Chalmers

A real-life intervention based on PCT in Switzerland and References

also in France and the United States recruited 1,759 patients, 1 Drijkoningen JJ, Rohde GG. Pneumococcal infection in adults:

and demonstrated that implementation of PCT reduced anti- burden of disease. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014;20(Suppl 5):4551

biotic treatment by 1.5 days with no increase in adverse 2 Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional

events.119 mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990

A large number of other biomarkers have been evaluated to and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease

Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380(9859):20952128

aid the diagnostic and prognostic decision-making process in

3 Kanwar M, Brar N, Khatib R, Fakih MG. Misdiagnosis of commu-

CAP. The most frequently evaluated biomarkers have been nity-acquired pneumonia and inappropriate utilization of anti-

CRP, PCT, Proadrenomedullin (ProADM), and copeptin.115 biotics: side effects of the 4-h antibiotic administration rule.

CRP has little value in the initial diagnosis in secondary Chest 2007;131(6):18651869

care, as levels as low as <10 mg/L can be detected in patients 4 Taylor JK, Fleming GB, Singanayagam A, Hill AT, Chalmers JD. Risk

with CAP.45 There is only a weak relationship between CRP factors for aspiration in community-acquired pneumonia: analysis

of a hospitalized UK cohort. Am J Med 2013;126(11):9951001

and severity of disease, but little added value of CRP over and

5 Teepe J, Little P, Elshof N, et al; GRACE consortium. Amoxicillin for

above severity scoring systems.45 Nevertheless, CRP is highly clinically unsuspected pneumonia in primary care: subgroup

effective as a means of assessing treatment response. Mortal- analysis. Eur Respir J 2016;47(1):327330

ity is less than 1% in patients where CRP has fallen by 50% or 6 Macfarlane J. Lower respiratory tract infection and pneumonia in

more at day 3 or 4.120,121 the community. Semin Respir Infect 1999;14(2):151162

Downloaded by: State University of New York at Stony Brook. Copyrighted material.

Akram AR, Chalmers JD, Hill AT. Predicting mortality with

Similarly, ProADM has been extensively studied.122 In a 7

severity assessment tools in out-patients with community-ac-

German study of 728 patients, it was the most accurate in

quired pneumonia. QJM 2011;104(10):871879

evaluating prognosis (patients with the highest levels had a 8 Lim HF, Phua J, Mukhopadhyay A, et al. IDSA/ATS minor criteria

3.7 times increased risk of death) with an area under the aid pre-intensive care unit resuscitation in severe community-

curve of 0.81, which was better than the CRB65 score.122 acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2014;43(3):852862

Independent studies have conrmed the prognostic accuracy 9 Salih W, Schembri S, Chalmers JD. Simplication of the IDSA/ATS

criteria for severe CAP using meta-analysis and observational

of this biomarker. A study by Albrich et al found that adding

data. Eur Respir J 2014;43(3):842851

ProADM to CURB65 enhanced outcome prediction, but there 10 Liapikou A, Cillniz C, Gabarrs A, et al. Multilobar bilateral and

are no studies to date showing that implementation of unilateral chest radiograph involvement: implications for prog-

ProADM improves outcome in clinical practice.123 nosis in hospitalised community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Re-

spir J 2016;48(1):257261

11 Sterrantino C, Trir G, Lapi F, et al. Burden of community-

Clinical Utility of Diagnostic Testing: acquired pneumonia in Italian general practice. Eur Respir J

Improving Outcomes and Antimicrobial 2013;42(6):17391742

Stewardship 12 Chalmers JD, Hill AT. Investigation of non-responding pre-

sumed lower respiratory tract infection in primary care. BMJ

An accurate diagnosis of CAP is important to reduce inappro- 2011;343:d5840

priate antibiotic use in the context of both primary care and in 13 Singanayagam A, Chalmers JD. Severity assessment scores to

guide empirical use of antibiotics in community acquired pneu-

secondary care. Inaccurate diagnosis of pneumonia and

monia. Lancet Respir Med 2013;1(8):653662

therefore inappropriate antibiotic treatment contribute to

14 Postma DF, van Werkhoven CH, van Elden LJ, et al; CAP-START Study

antibiotic resistance and to hospital-acquired infections such Group. Antibiotic treatment strategies for community-acquired

as Clostridium difcile, a major problem in Western coun- pneumonia in adults. N Engl J Med 2015;372(14):13121323

tries.124,125 Once the diagnosis is made, identication of the 15 Carugati M, Franzetti F, Wiemken T, et al. De-escalation therapy

causative pathogen allows deescalation of treatment.15 Van among bacteraemic patients with community-acquired pneu-

monia. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015;21(10):936.e11936.e18

der Eerden demonstrated that pathogen-directed therapy,

16 Aliberti S, Cilloniz C, Chalmers JD, et al. Multidrug-resistant patho-

using a combination of Gram stain and clinical features, gens in hospitalised patients coming from the community with

allowed deescalation of treatment without compromising pneumonia: a European perspective. Thorax 2013;68(11):997999

clinical outcomes.126 17 Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al; Infectious Diseases

Society of America; American Thoracic Society. Infectious Dis-

eases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus

Summary guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumo-

nia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27S72

Despite its limitations, chest X-ray remains the essential 18 Mandal P, Chalmers JD, Choudhury G, Akram AR, Hill AT. Vascular

diagnostic test to identify CAP in secondary care. In primary complications are associated with poor outcome in community-

care, the diagnosis remains clinical, but CRP measurement at acquired pneumonia. QJM 2011;104(6):489495

point of care can be valuable to identify those patients 19 American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of Amer-

requiring antibiotic treatment. Patients in secondary care ica. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-

acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneu-

should have a full battery of available microbiological tests,

monia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171(4):388416

including sputum and blood cultures, PCR for atypical organ- 20 Chalmers JD, Taylor JK, Singanayagam A, et al. Epidemiology,

isms, viruses, and urinary antigen testing. Developments in antibiotic therapy, and clinical outcomes in health care-associ-

PCR technology promise to improve diagnostic and prognos- ated pneumonia: a UK cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53(2):

tic assessment in CAP in the future. 107113

Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine Vol. 37 No. 6/2016

Modern Diagnostic Approach to CAP in Adults Chalmers 883

21 Aliberti S, Di Pasquale M, Zanaboni AM, et al. Stratifying risk 40 Bhatnagar R, Corcoran JP, Maldonado F, et al. Advanced medical

factors for multidrug-resistant pathogens in hospitalized interventions in pleural disease. Eur Respir Rev 2016;25(140):

patients coming from the community with pneumonia. Clin 199213

Infect Dis 2012;54(4):470478 41 Reali F, Sferrazza Papa GF, Carlucci P, et al. Can lung ultrasound

22 Welte T, Torres A, Nathwani D. Clinical and economic burden of replace chest radiography for the diagnosis of pneumonia in

community-acquired pneumonia among adults in Europe. Tho- hospitalized children? Respiration 2014;88(2):112115

rax 2012;67(1):7179 42 Ye X, Xiao H, Chen B, Zhang S. Accuracy of lung ultrasonography

23 Chalmers JD, Rother C, Salih W, Ewig S. Healthcare-associated versus chest radiography for the diagnosis of adult community-

pneumonia does not accurately identify potentially resistant acquired pneumonia: review of the literature and meta-analysis.

pathogens: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect PLoS ONE 2015;10(6):e0130066

Dis 2014;58(3):330339 43 Reissig A, Copetti R, Mathis G, et al. Lung ultrasound in the

24 Kollef MH, Shorr A, Tabak YP, Gupta V, Liu LZ, Johannes RS. diagnosis and follow-up of community-acquired pneumonia: a

Epidemiology and outcomes of health-care-associated pneumo- prospective, multicenter, diagnostic accuracy study. Chest 2012;

nia: results from a large US database of culture-positive pneu- 142(4):965972

monia. Chest 2005;128(6):38543862 44 Chavez MA, Shams N, Ellington LE, et al. Lung ultrasound for the

25 Cilloniz C, Torres A, Polverino E, et al. Community-acquired lung diagnosis of pneumonia in adults: a systematic review and meta-

respiratory infections in HIV-infected patients: microbial aetiol- analysis. Respir Res 2014;15:50

ogy and outcome. Eur Respir J 2014;43(6):16981708 45 Chalmers JD, Singanayagam A, Hill AT. C-reactive protein is an

26 Ewig S, Welte T, Chastre J, Torres A. Rethinking the concepts of independent predictor of severity in community-acquired pneu-

Downloaded by: State University of New York at Stony Brook. Copyrighted material.

community-acquired and health-care-associated pneumonia. monia. Am J Med 2008;121(3):219225

Lancet Infect Dis 2010;10(4):279287 46 Chalmers JD, Singanayagam A, Scally C, Hill AT. Admission D-

27 Rossouw TM, Anderson R, Feldman C. Impact of HIV infection and dimer can identify low-risk patients with community-acquired

smoking on lung immunity and related disorders. Eur Respir J pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med 2009;53(5):633638

2015;46(6):17811795 47 Llor C, Bjerrum L. Antibiotic prescribing for acute bronchitis.

28 Ewig S, Klapdor B, Pletz MW, et al; CAPNETZ Study Group. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2016;14(7):633642

Nursing-home-acquired pneumonia in Germany: an 8-year pro- 48 Singanayagam A, Schembri S, Chalmers JD. Predictors of mortal-

spective multicentre study. Thorax 2012;67(2):132138 ity in hospitalized adults with acute exacerbation of chronic

29 Polverino E, Dambrava P, Cillniz C, et al. Nursing home-acquired obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2013;

pneumonia: a 10 year single-centre experience. Thorax 2010; 10(2):8189

65(4):354359 49 Mao B, Yang JW, Lu HW, Xu JF. Asthma and bronchiectasis

30 Self WH, Wunderink RG, Williams DJ, et al. Staphylococcus aureus exacerbation. Eur Respir J 2016;47(6):16801686

community-acquired pneumonia. Prevalence, clinical character- 50 Chalmers JD, Aliberti S, Blasi F. Management of bronchiectasis in

istics and outcomes. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63(3):300309 adults. Eur Respir J 2015;45(5):14461462

31 Jones BE, Jones MM, Huttner B, et al. Trends in antibiotic use and 51 Kapoor JR, Kapoor R, Ju C, et al. Precipitating clinical features,

nosocomial pathogens in hospitalized veterans with pneumonia heart failure characterisation and outcomes in patients hospital-

at 128 Medical Centers, 20062010. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61(9): ized with heart failure with reduced borderline and preserved

14031410 ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail 2016;4(6):464472

32 Dobler CC, Waterer G. Healthcare-associated pneumonia: a US 52 Shepshelovich D, Goldvaser H, Edel Y, Shochat T, Lahav M. High

disease or relevant to the Asia Pacic, too? Respirology 2013; lung cancer incidence in heavy smokers following hospitalization

18(6):923932 due to pneumonia. Am J Med 2016;129(3):332338

33 Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD, Micek ST, Kollef MH. Prediction of 53 Aliberti S, Brambilla AM, Chalmers JD, et al. Phenotyping com-

infection due to antibiotic-resistant bacteria by select risk factors munity-acquired pneumonia according to the presence of acute

for health care-associated pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 2008; respiratory failure and severe sepsis. Respir Res 2014;15:27

168(20):22052210 54 Alves dos Santos JW, Torres A, Michel GT, et al. Non-infectious and

34 Prina E, Ranzani OT, Polverino E, et al. Risk factors associated with unusual infectious mimics of community-acquired pneumonia.

potentially antibiotic-resistant pathogens in community-ac- Respir Med 2004;98(6):488494

quired pneumonia. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015;12(2):153160 55 Bonaccorsi A, Cancellieri A, Chilosi M, et al. Acute interstitial

35 Jeong BH, Koh WJ, Yoo H, et al. Risk factors for acquiring pneumonia: report of a series. Eur Respir J 2003;21(1):187191

potentially drug-resistant pathogens in immunocompetent 56 Kastelik JA, Greenstone M, McGivern DV, Morice AH. Cryptogenic

patients with pneumonia developed out of hospital. Respiration organising pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2006;28(6):1291

2014;88(3):190198 57 Oyama Y, Fujisawa T, Hashimoto D, et al. Efcacy of short-term

36 Campbell SG, Murray DD, Hawass A, Urquhart D, Ackroyd-Stolarz prednisolone treatment in patients with chronic eosinophilic

S, Maxwell D. Agreement between emergency physician diagno- pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2015;45(6):16241631

sis and radiologist reports in patients discharged from an emer- 58 Rhee CK, Min KH, Yim NY, et al. Clinical characteristics and

gency department with community-acquired pneumonia. Emerg corticosteroid treatment of acute eosinophilic pneumonia. Eur

Radiol 2005;11(4):242246 Respir J 2013;41(2):402409

37 Chandra A, Nicks B, Maniago E, Nouh A, Limkakeng A. A multi- 59 Kuroyama M, Kagawa H, Kitada S, Maekura R, Mori M, Hirano H.

center analysis of the ED diagnosis of pneumonia. Am J Emerg Exogenous lipoid pneumonia caused by repeated sesame oil

Med 2010;28(8):862865 pulling: a report of two cases. BMC Pulm Med 2015;15:135

38 Claessens YE, Debray MP, Tubach F, et al. Early chest computed 60 Wang JY, Lee CH, Yu MC, Lee MC, Lee LN, Wang JT. Fluoroquino-

tomography scan to assist diagnosis and guide treatment deci- lone use delays tuberculosis treatment despite immediate

sion for suspected community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir mycobacteriology study. Eur Respir J 2015;46(2):567570

Crit Care Med 2015;192(8):974982 61 Tang KL, Eurich DT, Minhas-Sandhu JK, Marrie TJ, Majumdar SR.

39 Gonalves-Pereira J, Conceio C, Pvoa P. Community-acquired Incidence, correlates, and chest radiographic yield of new lung

pneumonia: identication and evaluation of nonresponders. cancer diagnosis in 3398 patients with pneumonia. Arch Intern

Ther Adv Infect Dis 2013;1(1):517 Med 2011;171(13):11931198

Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine Vol. 37 No. 6/2016

884 Modern Diagnostic Approach to CAP in Adults Chalmers

62 Mortensen EM, Copeland LA, Pugh MJ, et al. Diagnosis of pulmo- 81 Amaro R, Liapikou A, Cilloniz C, et al. Predictive and prognostic

nary malignancy after hospitalization for pneumonia. Am J Med factors in patients with blood-culture-positive community-ac-

2010;123(1):6671 quired pneumococcal pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2016;: 10.1183/

63 Goossens H, Little P. Community acquired pneumonia in primary 13993003.00039-2016 [Epub ahead of print]

care. BMJ 2006;332(7549):10451046 82 Torres A, Cillniz C, Ferrer M, et al. Bacteraemia and antibiotic-

64 van Vugt SF, Broekhuizen BD, Lammens C, et al; GRACE consor- resistant pathogens in community acquired pneumonia: risk and

tium. Use of serum C reactive protein and procalcitonin concen- prognosis. Eur Respir J 2015;45(5):13531363

trations in addition to symptoms and signs to predict pneumonia 83 Chalmers JD, Akram AR, Hill AT. Increasing outpatient treatment

in patients presenting to primary care with acute cough: diag- of mild community-acquired pneumonia: systematic review and

nostic study. BMJ 2013;346:f2450 meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2011;37(4):858864

65 Little P, Stuart B, Moore M, et al; GRACE consortium. Amoxicillin 84 Cillniz C, Civljak R, Nicolini A, Torres A. Polymicrobial commu-

for acute lower-respiratory-tract infection in primary care when nity-acquired pneumonia: An emerging entity. Respirology

pneumonia is not suspected: a 12-country, randomised, placebo- 2016;21(1):6575

controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2013;13(2):123129 85 Arnold FW, Summersgill JT, Lajoie AS, et al; Community-Acquired

66 Eccles S, Pincus C, Higgins B, Woodhead M; Guideline Develop- Pneumonia Organization (CAPO) Investigators. A worldwide

ment Group. Diagnosis and management of community and perspective of atypical pathogens in community-acquired pneu-

hospital acquired pneumonia in adults: summary of NICE guid- monia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175(10):10861093

ance. BMJ 2014;349:g6722 86 Yuan X, Liu Y, Bai C, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection is

67 Little P, Stuart B, Francis N, et al; GRACE consortium. Effects of associated with subacute cough. Eur Respir J 2014;43(4):

Downloaded by: State University of New York at Stony Brook. Copyrighted material.

internet-based training on antibiotic prescribing rates for acute 11781181

respiratory-tract infections: a multinational, cluster, random- 87 Sligl WI, Asadi L, Eurich DT, Tjosvold L, Marrie TJ, Majumdar SR.

ised, factorial, controlled trial. Lancet 2013;382(9899): Macrolides and mortality in critically ill patients with communi-

11751182 ty-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

68 Cals JW, Butler CC, Hopstaken RM, Hood K, Dinant GJ. Effect of Crit Care Med 2014;42(2):420432

point of care testing for C reactive protein and training in 88 Asadi L, Sligl WI, Eurich DT, et al. Macrolide-based regimens and

communication skills on antibiotic use in lower respiratory tract mortality in hospitalized patients with community-acquired

infections: cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2009;338:b1374 pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect

69 Minnaard MC, van de Pol AC, Hopstaken RM, et al. C-reactive Dis 2012;55(3):371380

protein point-of-care testing and associated antibiotic prescrib- 89 Cavallazzi R, Wiemken T, Christensen D, et al; Community-

ing. Fam Pract 2016;33(4):408413 Acquired Pneumonia Organization (CAPO) Investigators. Predict-

70 Huang Y, Chen R, Wu T, Wei X, Guo A. Association between point- ing Mycobacterium tuberculosis in patients with community-

of-care CRP testing and antibiotic prescribing in respiratory tract acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2014;43(1):178184

infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis of primary care 90 Burgos J, Lujn M, Larrosa MN, et al. The problem of early

studies. Br J Gen Pract 2013;63(616):e787e794 mortality in pneumococcal pneumonia: a study of risk factors.

71 Singanayagam A, Chalmers JD, Hill AT. Severity assessment in Eur Respir J 2015;46(2):561564

community-acquired pneumonia: a review. QJM 2009;102(6): 91 Browall S, Backhaus E, Naucler P, et al. Clinical manifestations of

379388 invasive pneumococcal disease by vaccine and non-vaccine types.

72 Choudhury G, Chalmers JD, Mandal P, et al. Physician judgement Eur Respir J 2014;44(6):16461657

is a crucial adjunct to pneumonia severity scores in low-risk 92 Finch S, McDonnell MJ, Abo-Leyah H, Aliberti S, Chalmers JD.

patients. Eur Respir J 2011;38(3):643648 A comprehensive analysis of the impact of Pseudomonas aerugi-

73 Cillniz C, Ewig S, Polverino E, et al. Community-acquired pneu- nosa colonisation on prognosis in adult bronchiectasis. Ann Am

monia in outpatients: aetiology and outcomes. Eur Respir J 2012; Thorac Soc 2015;12(11):16021611

40(4):931938 93 Rodrigo-Troyano A, Suarez-Cuartin G, Peir M, et al. Pseudomonas

74 Cillniz C, Gabarrs A, Almirall J, et al. Bacteraemia in outpatients aeruginosa resistance patterns and clinical outcomes in hospital-

with community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2016;47(2): ized exacerbations of COPD. Respirology 2016. doi: 10.1111/

654657 resp.12825

75 Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al; CDC EPIC Study Team. 94 Chalmers JD, Smith MP, McHugh BJ, Doherty C, Govan JR, Hill AT.

Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization Short- and long-term antibiotic treatment reduces airway and

among US adults. N Engl J Med 2015;373(5):415427 systemic inammation in non-cystic brosis bronchiectasis. Am J

76 Charles PG, Whitby M, Fuller AJ, et al; Australian CAP Study Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186(7):657665

Collaboration. The etiology of community-acquired pneumonia 95 Sibila O, Garcia-Bellmunt L, Giner J, et al. Airway mucin 2 is

in Australia: why penicillin plus doxycycline or a macrolide is the decreased in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary

most appropriate therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46(10): disease with bacterial colonization. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016;

15131521 13(5):636642

77 Takaki M, Nakama T, Ishida M, et al. High incidence of communi- 96 Botelho-Nevers E, Grattard F, Viallon A, et al. Prospective evalua-

ty-acquired pneumonia among rapidly aging population in tion of RT-PCR on sputum versus culture, urinary antigens and

Japan: a prospective hospital-based surveillance. Jpn J Infect serology for Legionnaires disease diagnosis. J Infect 2016;73(2):

Dis 2014;67(4):269275 123128

78 Luna CM, Famiglietti A, Absi R, et al. Community-acquired 97 Phin N, Parry-Ford F, Harrison T, et al. Epidemiology and clinical

pneumonia: etiology, epidemiology, and outcome at a teaching management of Legionnaires disease. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;

hospital in Argentina. Chest 2000;118(5):13441354 14(10):10111021

79 Galanis I, Lindstrand A, Darenberg J, et al. Effects of PCV7 and 98 Murdoch DR, Podmore RG, Anderson TP, et al. Impact of routine

PCV13 on invasive pneumococcal disease and carriage in Stock- systematic polymerase chain reaction testing on case nding for

holm, Sweden. Eur Respir J 2016;47(4):12081218 Legionnaires disease: a pre-post comparison study. Clin Infect

80 Mangen MJ, Rozenbaum MH, Huijts SM, et al. Cost-effectiveness Dis 2013;57(9):12751281

of adult pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in the Netherlands. 99 Thurman KA, Walter ND, Schwartz SB, et al. Comparison of

Eur Respir J 2015;46(5):14071416 laboratory diagnostic procedures for detection of Mycoplasma

Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine Vol. 37 No. 6/2016

Modern Diagnostic Approach to CAP in Adults Chalmers 885

pneumoniae in community outbreaks. Clin Infect Dis 2009;48(9): 115 Viasus D, Del Rio-Pertuz G, Simonetti AF, et al. Biomarkers for

12441249 predicting short-term mortality in community-acquired pneumonia:

100 Kumar S, Hammerschlag MR. Acute respiratory infection due to A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect 2016;72(3):273282

Chlamydia pneumoniae: current status of diagnostic methods. 116 Schuetz P, Christ-Crain M, Thomann R, et al; ProHOSP Study

Clin Infect Dis 2007;44(4):568576 Group. Effect of procalcitonin-based guidelines vs standard

101 Lee N, Leo YS, Cao B, et al. Neuraminidase inhibitors, superinfec- guidelines on antibiotic use in lower respiratory tract infections:

tion and corticosteroids affect survival of inuenza patients. Eur the ProHOSP randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;302(10):

Respir J 2015;45(6):16421652 10591066

102 Ho PL, Sin WC, Chan JF, Cheng VC, Chan KH. Severe inuenza A 117 Choudhury G, Mandal P, Singanayagam A, Akram AR, Chalmers

H7N9 pneumonia with rapid virological response to intravenous JD, Hill AT. Seven-day antibiotic courses have similar efcacy to

zanamivir. Eur Respir J 2014;44(2):535537 prolonged courses in severe community-acquired pneumoniaa

103 Jefferson T, Jones M, Doshi P, Del Mar C. Neuraminidase inhibitors propensity-adjusted analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011;17(12):

for preventing and treating inuenza in healthy adults: system- 18521858

atic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2009;339:b5106 118 Murray C, Shaw A, Lloyd M, et al. A multidisciplinary intervention

104 Chan MC, Lee N, Ngai KL, Leung TF, Chan PK. Clinical and virologic to reduce antibiotic duration in lower respiratory tract infections.

factors associated with reduced sensitivity of rapid inuenza J Antimicrob Chemother 2014;69(2):515518

diagnostic tests in hospitalized elderly patients and young chil- 119 Albrich WC, Dusemund F, Bucher B, et al; ProREAL Study Team.

dren. J Clin Microbiol 2014;52(2):497501 Effectiveness and safety of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic ther-

105 Chartrand C, Leeang MM, Minion J, Brewer T, Pai M. Accuracy of apy in lower respiratory tract infections in real life: an interna-

Downloaded by: State University of New York at Stony Brook. Copyrighted material.

rapid inuenza diagnostic tests: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med tional, multicenter poststudy survey (ProREAL). Arch Intern Med

2012;156(7):500511 2012;172(9):715722

106 Lee N, Lui GC, Wong KT, et al. High morbidity and mortality in 120 Akram AR, Chalmers JD, Taylor JK, Rutherford J, Singanayagam A,

adults hospitalized for respiratory syncytial virus infections. Clin Hill AT. An evaluation of clinical stability criteria to predict

Infect Dis 2013;57(8):10691077 hospital course in community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Micro-

107 Lorente ML, Falguera M, Nogus A, Gonzlez AR, Merino MT, biol Infect 2013;19(12):11741180

Caballero MR. Diagnosis of pneumococcal pneumonia by poly- 121 Menndez R, Martinez R, Reyes S, et al. Stability in community-

merase chain reaction (PCR) in whole blood: a prospective acquired pneumonia: one step forward with markers? Thorax

clinical study. Thorax 2000;55(2):133137 2009;64(11):987992

108 Peters RP, de Boer RF, Schuurman T, et al. Streptococcus pneumo- 122 Krger S, Ewig S, Giersdorf S, Hartmann O, Suttorp N, Welte T;

niae DNA load in blood as a marker of infection in patients with German Competence Network for the Study of Community

community-acquired pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol 2009;47(10): Acquired Pneumonia (CAPNETZ) Study Group. Cardiovascular

33083312 and inammatory biomarkers to predict short- and long-term

109 Rello J, Lisboa T, Lujan M, et al; DNA-Neumococo Study Group. survival in community-acquired pneumonia: results from the

Severity of pneumococcal pneumonia associated with genomic German Competence Network, CAPNETZ. Am J Respir Crit Care

bacterial load. Chest 2009;136(3):832840 Med 2010;182(11):14261434

110 Cremers AJ, Hagen F, Hermans PW, Meis JF, Ferwerda G. Diagnos- 123 Albrich WC, Dusemund F, Regger K, et al. Enhancement of

tic value of serum pneumococcal DNA load during invasive CURB65 score with proadrenomedullin (CURB65-A) for outcome

pneumococcal infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2014; prediction in lower respiratory tract infections: derivation of a

33(7):11191124 clinical algorithm. BMC Infect Dis 2011;11:112

111 Resti M, Moriondo M, Cortimiglia M, et al; Italian Group for the 124 Chalmers JD, Al-Khairalla M, Short PM, Fardon TC, Winter JH.

Study of Invasive Pneumococcal Disease. Communityacquired Proposed changes to management of lower respiratory tract

bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia in children: diagnosis and infections in response to the Clostridium difcile epidemic.

serotyping by realtime polymerase chain reaction using blood J Antimicrob Chemother 2010;65(4):608618

samples. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51(9):10421049 125 Chalmers JD, Akram AR, Singanayagam A, Wilcox MH, Hill AT.

112 Simpson JL, Daly J, Baines KJ, et al. Airway dysbiosis: Haemophilus Risk factors for Clostridium difcile infection in hospitalized

inuenzae and Tropheryma in poorly controlled asthma. Eur patients with community-acquired pneumonia. J Infect 2016;

Respir J 2016;47(3):792800 73(1):4553

113 Smith DJ, Badrick AC, Zakrzewski M, et al. Pyrosequencing reveals 126 van der Eerden MM, Vlaspolder F, de Graaff CS, et al. Comparison

transient cystic brosis lung microbiome changes with intrave- between pathogen directed antibiotic treatment and empirical

nous antibiotics. Eur Respir J 2014;44(4):922930 broad spectrum antibiotic treatment in patients with community

114 Wang Z, Bafadhel M, Haldar K, et al. Lung microbiome dynamics acquired pneumonia: a prospective randomised study. Thorax

in COPD exacerbations. Eur Respir J 2016;47(4):10821092 2005;60(8):672678

Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine Vol. 37 No. 6/2016

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- CommunityDokumen11 halamanCommunityJaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Distress Syndrome (ARDS) : Penggunaan Ventilasi Mekanis Invasif Pada Acute RespiratoryDokumen9 halamanDistress Syndrome (ARDS) : Penggunaan Ventilasi Mekanis Invasif Pada Acute Respiratorydoktermuda91Belum ada peringkat

- All 13496Dokumen15 halamanAll 13496Jaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Treatment of Fungal Infections in Adult Pulmonary Critical Care and Sleep MedicineDokumen33 halamanTreatment of Fungal Infections in Adult Pulmonary Critical Care and Sleep MedicineIsabel Suni Jimenez CasaverdeBelum ada peringkat

- Post-Tuberculous Bronchiectasis Indications for Surgical TreatmentDokumen2 halamanPost-Tuberculous Bronchiectasis Indications for Surgical TreatmentJaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- PE GuidelinesDokumen12 halamanPE GuidelinesJaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Lung Hyperinflation in COPD: Applying Physiology To Clinical PracticeDokumen12 halamanLung Hyperinflation in COPD: Applying Physiology To Clinical PracticeJaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- LastDokumen3 halamanLastJaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- DC in Priming T CellDokumen8 halamanDC in Priming T CellJaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Aztreonam: Antibiotic ClassDokumen2 halamanAztreonam: Antibiotic ClassJaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Recurrent Pleural Effusion from Unknown CauseDokumen3 halamanRecurrent Pleural Effusion from Unknown CauseJaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Zhan El 2004Dokumen7 halamanZhan El 2004Jaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Chylothorax Diagnosis Review 2010Dokumen7 halamanChylothorax Diagnosis Review 2010adriantiariBelum ada peringkat

- Aquickreferenceon Respiratoryacidosis: Rebecca A. JohnsonDokumen5 halamanAquickreferenceon Respiratoryacidosis: Rebecca A. JohnsonJaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Unilateral Post TB Destroy LungDokumen3 halamanUnilateral Post TB Destroy LungJaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Page 1Dokumen9 halamanPage 1Jaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Streptococcus Suis Serotype 2-Induced Meningoencephalitis: Cerebral Abscesses in A Pig: Atypical Manifestations ofDokumen5 halamanStreptococcus Suis Serotype 2-Induced Meningoencephalitis: Cerebral Abscesses in A Pig: Atypical Manifestations ofJaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Bubble Trouble A Review of Diving Physiology andDokumen9 halamanBubble Trouble A Review of Diving Physiology andJaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Respiratory Failure Mechanical VentilationDokumen37 halamanRespiratory Failure Mechanical Ventilationawakepull312Belum ada peringkat

- Necrotizing Pneumonia 1Dokumen7 halamanNecrotizing Pneumonia 1Jaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Mehl Horn 2007Dokumen8 halamanMehl Horn 2007Jaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Time vs Concentration Dependent Antibiotic KillingDokumen4 halamanTime vs Concentration Dependent Antibiotic KillingMaddy AlbuletBelum ada peringkat

- Respiratory Medicine Case ReportsDokumen3 halamanRespiratory Medicine Case ReportsJaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Thoraxjnl 2015 208188Dokumen6 halamanThoraxjnl 2015 208188Jaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- 2.BE PathogenesisDokumen7 halaman2.BE PathogenesisJaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Bubble Trouble A Review of Diving Physiology andDokumen9 halamanBubble Trouble A Review of Diving Physiology andJaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- 1.BE Airway DefenseDokumen11 halaman1.BE Airway DefenseJaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Distress Syndrome (ARDS) : Penggunaan Ventilasi Mekanis Invasif Pada Acute RespiratoryDokumen9 halamanDistress Syndrome (ARDS) : Penggunaan Ventilasi Mekanis Invasif Pada Acute Respiratorydoktermuda91Belum ada peringkat

- Algrythm HypercalcemiaDokumen7 halamanAlgrythm HypercalcemiaJaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Lung Abscess Diagnosis, Etio, Treatment OptionDokumen12 halamanLung Abscess Diagnosis, Etio, Treatment OptionJaya Semara PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Yasser Al Kadri and Zaid Al AzemDokumen14 halamanYasser Al Kadri and Zaid Al Azemalsakar26Belum ada peringkat

- Survival in Long CaseDokumen7 halamanSurvival in Long CaseRapid MedicineBelum ada peringkat

- Study Guide To GattacaDokumen6 halamanStudy Guide To Gattacathe_wise_one100% (1)

- DifcoBBLManual 2ndedDokumen700 halamanDifcoBBLManual 2ndedEl CapitanBelum ada peringkat

- International Student Application Form: Privacy Statement Privacy NoticeDokumen6 halamanInternational Student Application Form: Privacy Statement Privacy NoticeStella mariz DelarnaBelum ada peringkat

- Virus TableDokumen3 halamanVirus TableFrozenManBelum ada peringkat

- Daily Test 1 Science Grade 9Dokumen2 halamanDaily Test 1 Science Grade 9luckybrightstar_27Belum ada peringkat

- Tools of BioinformaticsDokumen29 halamanTools of BioinformaticsM HaroonBelum ada peringkat

- The Evolution of Whales Essay 1Dokumen3 halamanThe Evolution of Whales Essay 1api-243322010100% (1)

- @medicinejournal American Journal of Perinatology September 2017Dokumen128 halaman@medicinejournal American Journal of Perinatology September 2017angsukriBelum ada peringkat

- Lecture On Blood Groups, Transfusion, RH Incompatibility by Dr. RoomiDokumen41 halamanLecture On Blood Groups, Transfusion, RH Incompatibility by Dr. RoomiMudassar Roomi100% (1)

- Big Data in Health Care Sector: Department of Computer ApplicationsDokumen9 halamanBig Data in Health Care Sector: Department of Computer ApplicationsReshma K.PBelum ada peringkat

- Dissocial Personality DisorderDokumen52 halamanDissocial Personality DisorderSam InvincibleBelum ada peringkat

- NBME CompDokumen7 halamanNBME CompWinter Ohio100% (4)

- Eucerin - Nobel Prize Revolutionises Skin Care - Cells' Water Channels Specifically StimulatedDokumen2 halamanEucerin - Nobel Prize Revolutionises Skin Care - Cells' Water Channels Specifically StimulatedFelpnilBelum ada peringkat

- Incredible Italian Brand-New Ocean LinerDokumen1 halamanIncredible Italian Brand-New Ocean LinerTrisha Park100% (1)

- Morgellons Disease Related To Black Magic Rituals PDFDokumen30 halamanMorgellons Disease Related To Black Magic Rituals PDFadu66680% (5)

- Borrador Writing 3Dokumen3 halamanBorrador Writing 3Carlos LazoBelum ada peringkat

- Components of BloodDokumen13 halamanComponents of BloodMichael LiongBelum ada peringkat

- Antigen Processing and Presentation 09Dokumen34 halamanAntigen Processing and Presentation 09Khairul Ikhwan100% (2)

- Pathophysiology Respiratory SystemDokumen63 halamanPathophysiology Respiratory SystemAli Basha QudahBelum ada peringkat

- 2402 CH 17 Endocrine System (Part 1) PDFDokumen23 halaman2402 CH 17 Endocrine System (Part 1) PDFHarry RussellBelum ada peringkat

- Human Amyloid Imaging 2015 Book DraftDokumen151 halamanHuman Amyloid Imaging 2015 Book DraftWorldEventsForumBelum ada peringkat

- Methemoglobinemia Diagnosis & Treatment GuideDokumen11 halamanMethemoglobinemia Diagnosis & Treatment GuideAranaya DevBelum ada peringkat

- Pharmacology Lecture 6th WeekDokumen55 halamanPharmacology Lecture 6th WeekDayledaniel SorvetoBelum ada peringkat

- Inquisitor Character Creation and AdvancementDokumen10 halamanInquisitor Character Creation and AdvancementMichael MonchampBelum ada peringkat

- The Enigma of Death ExplainedDokumen19 halamanThe Enigma of Death Explainedsorrisodevoltaire0% (1)

- Definition and Nature of ResearchDokumen20 halamanDefinition and Nature of ResearchJiggs LimBelum ada peringkat

- Antibiotics Libro PDFDokumen490 halamanAntibiotics Libro PDFMarianaBelum ada peringkat

- Poodle Papers Summer 2012Dokumen33 halamanPoodle Papers Summer 2012PCA_websiteBelum ada peringkat