BEdCourseCode103 Unit3

Diunggah oleh

NihalSoni0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

36 tayangan20 halamanBed

Judul Asli

BEdCourseCode103_Unit3

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniBed

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

36 tayangan20 halamanBEdCourseCode103 Unit3

Diunggah oleh

NihalSoniBed

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 20

STUDY MATERIAL FOR B.Ed.

INSTITUTE OF ADVANCED STUDIES IN

EDUCATION (IASE),

Srinagar- India.

Re-Accredited by NAAC in 2011 Grade A

(Score 3.52 on 4 Point Scale).

First Semester Population and Gender Education

UNIT III: GENDER STUDIES

i. Concept, need and scope of gender studies

ii. Gender studies as an academic discipline

iii. Gender, economy and work participation

iv. Gender, globalization and education

1

i. Concept of gender studies

A gender study is a field of study that looks at the world from the perspective of gender. This

means that while studying something – the distribution of resources within a household, a social

unit like a caste group, a bill placed before Parliament, a development project, the classification

of different species – are done in a manner that takes into account the fact that different genders

exist in the world. These genders are differently placed within social reality such that various

processes impact them differently. Thus gender studies recognize that gender has to be taken

seriously. Gender studies exist as an important means of correcting imbalances. Gender has been

the subject of scientific scrutiny for over a century. Scientists have debated the similarities as

well as the differences. ‘Gender’ is the term widely used to refer to those ways in which a culture

reformulates what begins as a fact of nature. The biological sexes are redefined, represented,

valued, and channeled into different roles in various culturally dependent ways. Sex is the

concept that emerges from anatomical and physiological characteristics that differentiates males

and females biologically whereas gender can be seen as a social construct manifested by

masculine and feminine roles prevalent in a culture or a society. Thus gender can be seen as an

artifact of social, cultural and psychological factors which are attained during the process of

socialization of an individual. In talking about the social and cultural construction of masculinity

and femininity, gender allows us to see these dimensions of human roles and personalities as

based not on nature but on social factors. It then allows us to address issues like subordination

and discrimination as issues where change is possible. Therefore the meaning of sex and gender,

femininity and masculinity fluctuates within societies and cultures across the globe. Gender

Studies is a well established interdisciplinary field of study which draws on knowledge from the

humanities, the social sciences, medicine, and natural science. It engages critically with gender

realities, gender norms, gender relations and gender identities from intersectional perspective.

Intersectional perspective is required to focus on the ways in which gender inter-relates with

other social organizations such as ethnicity, class, sexuality, and nationality etc. Within gender

studies, there is a recognition that men and women do not exist in isolation from their other

social roles and positions. A women is not only a woman – within our society, she also has a

certain class position, caste position, religious identity, sexual identity, and many more. All of

these factors impact her life – therefore while studying her life, all these factors need to be taken

2

into consideration. Another feature of gender studies is that it examines how the world is

gendered. Some examples can explain this concept in more clear terms:

Think of the difference in girls’ and boys’ clothing. Skirts, saris are seen as feminine clothing,

and trousers, shirts etc. as masculine. There are other differences too – feminine clothing is often

more colourful than masculine clothing, more likely to be decorated with sparkles and shiny

material. Sometimes there is an overlap in men and women’s clothing. For example, both men

and women may wear denim jeans. But even here, it can be noted that there are differences – in

cuts, i.e. in how the jeans fits the wearer (tight or loose), in colours and embellishments

(embroidery, sequins, crystals etc.). Thus even in common items of clothing, there are

differences. Clothing is gendered. It differs for both genders, and in doing so; it allows

determining whether the wearer is male or female. Sometimes men and women do wear clothing

that is absolutely identical. For example, a school uniform may also consist of a tie that both girls

and boys have to wear. In this case, can it be said that the tie is also a gendered article of

clothing. From a gender studies perspective, it will be seen that clothing that is common to both

men and women is often men’s clothing that women have also adopted. Neckties would be an

example of this. Think of other examples. It may be noticed that both men and women go to

work in offices wearing business suits – trousers and jackets. These are masculine clothes that

have been adopted by women. It is much less common to find examples of women’s clothing

that have been adopted, on a large scale, by men. It is not usual to see men going to work

wearing saris. This example also indicates another area that gender studies focuses on – that of

power differences between genders. It is more common to see the powerless adopting the

characteristics of the powerful, than the powerful adopting the characteristics of the powerless.

Life in a Gendered World People may advise a young person on which subjects to take in school

or college by saying, “you should study this – it is a good subject for a girl” or “that is not the

right subject for a boy”. In this way, education is also gendered, as is the job market – different

opportunities are considered to be appropriate for girls and boys. Certain careers are gendered –

nursing, for example, is a profession that has more women than men and which is not deemed

appropriate for men.

3

Physical spaces may be gendered. Think of the roads of a city – can anyone be out on the street

at any time? There are no rules prohibiting anyone from going out onto the street. Yet it is found

that women do not stay out on the streets as late as men do. Women also do not spend time

hanging around on the streets – at a teashop, for instance, alone or chatting with friends. Men and

women thus have different kinds of access to streets, and have different experiences of being out

on the streets. In these ways, physical spaces are also gendered.

Thus various aspects of living world are gendered. They differ for different genders, the

experiences of them differ in ways that depending upon the gender. The study of the gendered

nature of the social and physical world is an important part of gender studies. The perspective of

gender studies can be applied to a variety of situations from different academic disciplines –

sociology, political science, biology, law, and economics. Thus gender studies encompass many

disciplines. It is multidisciplinary. This is an important dimension of gender studies because it

has also pointed out certain gaps in various disciplines.

You may have observed seats being reserved for women on public transport. What does this say

about public transport being gendered? The origins of gender studies lie in women’s studies.

Women’s studies came into being in order to address the gaps and imbalances in academic

knowledge that resulted from an inadequate incorporation of women into academics. Many

women’s studies scholars have pointed out that often, academic disciplines would not take

women into account when developing theories and concepts, or when doing research and

collecting data. Women’s unpaid housework is not calculated as part of our country’s GDP. If

the GDP is to reflect the total of the goods and services produced in the country, shouldn’t it then

include housework? A gender studies perspective can, in this way, indicate and correct

imbalances and inaccuracies in various disciplines. It can also ask the significant question – why

have these errors and imbalances come into being? Why have various disciplines not recognised

the contributions of women? Why have these contributions been devalued and/or ignored?

Gender studies have questioned the theories and underlying assumptions of many disciplines. In

doing so, it has also developed new tools and techniques for research. One of the most significant

dimensions of gender studies is that it is political. It raises questions about power in society, and

how and why power is differentially distributed between different genders. It asks questions

4

about who has power over whom, in which situations, how power is exercised, and how it is, and

can be, challenged. Different theories and perspectives within gender studies have different

approaches to these questions, and look for answers in different social processes.

In addition to its focus on the history and achievements of women, gender studies has inspired

research and curricula that address men’s lives, masculinity and the lives of people identified as

Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual or Transgender. (LGBT). Being LGBT is not just about physical

attraction, but rather, encompasses the same needs all people have, to love another person and be

loved in return. Regardless of sexual orientation, we all have the same basic emotional needs. At

times you may have heard LGBT people spoken of as if their entire existence was limited only to

their sexuality, but this is only one part of their being, and how they identify themselves.

Throughout history many of our great writers, poets, actors, scientists, artists, thinkers, sports

men and women, philosophers, musicians and politicians were, and are, LGBT.

Difference between Sex and Gender

Sex: Male and Female

Gender: Masculine and Feminine

In sociological terms ‘gender roles’ refers to the characteristics and behaviours that different

cultures attribute to the sexes. What it means to be a ‘real man’ in any culture requires male sex

plus whatever various cultures define as masculine characteristics and behaviours, likewise a

‘real woman’ needs female sex and feminine characteristics.

Consequently,

Male = Male sex + Masculine social role (A ‘real man’, ‘masculine’ or ‘manly’)

Woman = Female sex + Feminine social role (A ‘real woman’, ‘feminine’ or ‘womanly’)

Sex refers to biological differences; chromosomes, hormonal profiles, internal or external sex

organs. Hence, sex refers to a set of biological differences between women and men which is

genetically determined. Only a very small proportion of the differences in roles assigned to men

and women can be attributed to biological or physical differences based on sex. For example,

5

pregnancy, childbirth and differences in psychology can be attributed to sex-related

characteristics.

Gender describes the characteristics that a society or culture delineates as masculine or feminine.

Hence, gender refers to the socially determined differences between women and men, such as

roles, attitudes, behavior and values. Gender roles are learned and vary across cultures and over

time; they are thus amendable to change. Gender is a relational term that includes both women

and men. Gender equality focuses on changes for both men and women.

Sex Vs Gender

Sometimes it is hard to understand exactly what is meant by the term ‘gender’ and how it differs

from the closely related term ‘sex’. Understanding of the social construction of gender starts with

explaining the two concepts, i.e., gender and sex. Often these two terms are used

interchangeably: however, they bear different meanings as concepts. “Sex” refers to the

biological and physiological characteristics that define men and women. It is defined as the

anatomical and physiological characteristics that signify the biological maleness and femaleness

of an individual. “Gender” refers to the socially constructed roles, behaviours, activities, and

attributes that a given society considers appropriate for men and women. Gender emphasizes that

masculinity and femininity are products of social, cultural and psychological factors. In our

society men and women perform different roles and are assigned different responsibilities.

Importance of Gender Studies

Gender studies explores the ways that femininity and masculinity affect an individual’s thought

process. Let us understand this with the help of an example given below:

Case1: Saira is getting married in a few days. Her grandmother is instructing her on how to

behave during the wedding – she has to be calm and quiet in front of her relatives, and look shy

whenever someone mentions her fiancé. Saira wonders why she should act shy when she does not

feel shy.

6

Case2: Neetu’s cousin Aman has joined the Merchant Navy. His job sounds interesting and fun

– he travels all around the world, visiting so many different places. Neetu is also thinking of the

Merchant Navy as a career option after she finishes school. However her uncle discourages her.

“How will you manage your family life?” he asks. “You would be sailing for months at a time.

Who would look after your children?”

If we try to identify the differences between girls and boys, some of the following lines will be

heard: Girls are more sensitive and emotional – more likely to get upset, scared, more likely to

cry. They are also sensitive in another sense of the term – they are more aware of other people’s

feelings (have you ever heard the phrase ‘female intuition’?) and more caring towards others.

They may extend this to an ability to take care of others – in other words, to look after or

empathize with people. Conversely, boys are stronger (physically and mentally) and more

authoritative. They are physically less gentle, perhaps somewhat rough. They may be less

sensitive but they are bold and outgoing, rational and practical. They have to be – after all, they

have to go out into the world, earn their livings, and support their families.

These paragraphs give a sense of what is generally defined as by femininity and masculinity. As

stated earlier ‘gender’ refers to the characteristics that are culturally and socially imparted on the

basis of a person’s biological sex. ‘Femininity’ refers to those characteristics that are associated

with being female – with being a girl or woman. ‘Masculinity’ refers to those characteristics that

are associated with being male – a boy or man.

Look at the two paragraphs again. It can be noticed that when feminine features are described,

two things are talked about at the same time – traits and behaviour. In other words, what people

are like, and how they should behave. Thus if it is said that boys are rational and practical, they

are expected to be rational and practical, and to act rational and practical in concrete situations.

There is also a third facet of masculinity and femininity – it is expected that they will fit the

social roles that girls or boys are expected to perform later as adults in their lives. Those traits are

inculcated in girls and boys who are thought to be required by them as adults. It means that there

are certain expectations of what a person is going to do in his or her life, expectations that are

based on whether that person is male or female.

7

Gender studies explores power as it relates to gender and other forms of identity including

sexuality, masculinities and femininities, race, class, religion, nationality and gender systems in

the society. The degree of control exercised by certain people/institutions/organizations over

material, human, intellectual and financial resources can be defined as Power. The control of

these resources becomes the source of power. It is dynamic and relational and exercised in the

social, economic and political relation between individuals and groups. It is also distributed

unequally where some individuals or groups have greater control over the resources and others

have little or no control.

Male dominance can be expressed in various ways – for example, within the institution of the

family, in the greater rights given to men, through the ownership and control by men of resources

like land and other assets. Within gender studies, the term refers to a social system wherein men

dominate over women. In sociology this is termed as patriarchy that literally means the ‘rule of

the father’. Patriarchy takes different forms in different social and historical contexts. This is

because patriarchy is a system which interacts with other systems in society. It operates

differently in different communities, economic systems, countries, etc. A patriarchal society is a

society controlled, and run by men. Men devise the rules and hold dominating positions at home,

in community, in business and government. "A man's world", is a phrase that is used to talk

about this. They hold the privilege to listing out rules and dominate in all forums both inside and

outside the home. In such a societal setup a woman is seen more as supplementing and

supporting a man (behind every successful man is a woman), bearing children and taking care of

household chores. This is how it is and has been for ages in many of the cultures. Feminists used

the concept of patriarchy in early 20th century to expound the social arrangement of male

dominance over women. The underlying ideology of a patriarchal society is all about the men

possessing superior qualities or typical attitudes and traits like – virility, strong will power,

authority, dominance, bullying, shrewdness, maintaining confidentiality, social associations and

network, action oriented, having a free will, a sense of superiority over others (outlook, race,

gender), brute force, belligerence, carrier of family legacy so on and so forth. Thus in a

patriarchal social structure, the patriarch is an elder holding societal legitimate power over a

group in the community unit. Men acquires a dominant status not in terms of numbers or in

strength but by means of having a more prominent and powerful social position and having

almost absolute access to decision-making power. It is also related to economics as in patriarchal

8

societies men will have greater power and control over the economy. In such a scenario, because

men have higher income and greater hold on the economy, they are said and considered to be

dominant. There are a variety of ways in which patriarchy can be enforced. This may include

extortion through violence, physical and mental assault and other forms of harassment, and the

demeaning of their efforts to unify and resist. Authoritarian traits are typical of patriarchal

societies and they trust heavily on legal-rational approaches of association, show stronger martial

implication and also reliance on police suppression to impose authority. In such a setting it is a

general trend to hold contempt for women and for her attempts to liberate herself. In these

societies, women are presented with an interpretation of the world made by men, and a history of

the world defined by men's actions. For instance, in history when we read about war and

conquests, we read more about male warriors, whereas the stories of women are scarcely told.

This expurgation of women's lives distances women and fails to provide them with relevant role

models. In contrast, matriarchal societies honour women as key decision-makers and they hold

the privileged positions as community leaders, where they play a central role in the family,

community and in the society. In the few matriarchal societies that exist today women's rights

are central; women are given space to express their creativity and participate in society.

Analyze the case given below and come up with possible reasons behind the series of event

depicted and their best possible solutions according to you.

“Suhana and her husband were working in the same multinational organization where she was

paid lesser wages than her husband for the same profile. Still she always wanted to continue her

job after marriage as she was reasonably happy with it. But after few months her mother in law

started pressurizing her to stop going to work. She also forced her to bring more money from her

parents for the renovation of their house. “

Different degrees of power are sustained and perpetuated through social stratification like

gender, class, caste etc. Power can be understood as operating in a number of different ways:

• power over: This power involves an either/or relationship of domination/subordination.

Ultimately, it is based on socially sanctioned threats of violence and intimidation, it requires

constant vigilance to maintain, and it invites active and passive resistance;

9

• power to: This power relates to having decision-making authority, power to solve problems and

can be creative and enabling;

• power with: This power involves people organizing with a common purpose or common

understanding to achieve collective goals;

• power within: This power refers to self confidence, self awareness and assertiveness. It relates

to how individuals can recognize through analyzing their experience; how power operates in

their lives, and gain the confidence to act to influence and change this.

It also analyzes how gender plays out in politics, life, culture, workplace, athletics, technology,

health, science and in the production of knowledge. College is a key to success in life. In order to

achieve success in life with little or no struggles, one has to go to college to get an education that

will lead them later on to a career of their choice. College courses emphasize critical thinking

and analysis with social justice activism teaching interdisciplinary methods. The perspective of

gender studies can be applied to a variety of situations from different academic disciplines –

sociology, political science, biology, law, and economics. Thus gender studies encompass many

disciplines. It is multidisciplinary. This is an important dimension of gender studies because it

has also pointed out certain gaps in various disciplines. This helps us to explore intersections of

femininity studies, masculinity studies, and assists students with professional development.

Gender studies emphasis on relation between gender and society historically and cross-culturally,

and on the changes occurring in the roles of women and men, on the participation of women in

the major institutions of society and on women themselves. Gender roles can be defined as the

social roles that a person is expected to fulfill based upon his or her gender. These vary in

different social, cultural and historical contexts. They vary among different societies and

cultures, classes, ages and during different periods in history. Gender –specific roles and

responsibilities are often conditioned by household structure, access to resources, specific

impacts of the global economy, and other locally relevant factors such as ecological conditions.

Gender can be understood as a one that takes shape through its intersection with other relations

of power, including sexuality, race, class, nationality, religion. Gender relations are the ways in

which a culture or society defines rights, responsibilities, and the identities of men and women in

relation to one another. Men and women respond to different situations and conditions

differently, this is not because of their biological traits but because of their socially and culturally

10

endorsed roles; therefore they ascribe to acquire distinct and diverse sets of knowledge and

needs. Ever since human started living in societies, the differentiation between the male and the

female gender and implicated specific lifestyle, duties and functional areas for each of these

genders began. In many societies across the globe a differentiation is seen between the roles and

relations of men and women. The socio-cultural norms of a society are instrumental in

demarcating the gender relations. They indicate the way men and women relate to each other in a

socio-cultural setting and subsequently lead to the display of gender-based power. This develops

from the expected and gendered roles assumed by men and women and the impact of their

interactions. A good example for this can be ‘The family’. In this setting man assumes the

provider and decision maker’s roles and woman takes-up the familial and childcare roles. These

power relations are biased because the male has more power in making financially, legally and

socially influential decisions. Roles, assumed attributes and socio-cultural norms lead to the

design of behavioural blueprints. Those who do not conform to these roles are seen to be deviant

as per the societal standards. In most of the societies the family systems are based on the similar

structure of such gender roles and it is predesigned, these stringently structured roles that rein

members of the family to be in this institution with bound responsibilities. Gender roles are

societal, cultural and personal. They regulate how males and females should think, speak, dress,

and interact within the context of society. Learning reinforced through various societal

institutions plays a role in this process of shaping gender roles. While various socializing agents-

parents, teachers, peers, movies, television, music, religion- teach and strengthen gender roles

throughout the lifespan, parents probably exert the greatest influence. The way in which gender

roles are absorbed and assimilated by a group of people describes the influence of society. The

role of a man and a woman in society is influenced by a variety of factors. These factors vary

with the region, religion, culture, climate, historical beliefs, ideologies and experiences, across

the globe. It offers historical, contemporary and transnational analysis of how gender and sexual

formations arise in different contexts such as colonialism, nationalism and globalization. In

addition to its focus on history and achievements of women, gender scholarships has inspired

research and curricula that addresses men’s lives, masculinity, and lives of people identified as

Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual or Transgender. The modern life has very much changed the family

structure and the gender roles have been shifting from the traditional structures of responsibilities

and roles. These families can be seen taking decisions respecting each other’s views, expressing

opinions openly, critiquing and encouraging mutually and yet being independent and

11

responsible. The society- defined gender roles are changing with this societal change and many

families are experiencing yet trying to cope with the dilemma of the gender roles.

ii. Gender Studies as an academic discipline

Gender Studies is a well established interdisciplinary field of study which draws on knowledge

from the humanities, the social sciences, medicine, and natural science. The basis for the

academic field of Gender Studies was in many countries laid in the 1970s, when women in

Academia protested against the ways in which academic knowledge production made women

invisible and ignored gendered power relations in society. Interdisciplinary study environments

started to mushroom, among others in many European countries and in North America, where

so-called Women’s Studies Centres were set up, gathering critical teachers and students who

wanted to study gender relations, and women, in particular. The Women’s and Gender Studies

Program offers feminist perspectives on the human experience, analyzes the role of women in

history, challenges cultural assumptions about women, emphasizes the contributions of women

and discusses the larger, global disadvantages that are faced by women. It also recognizes that

there has never been just “one” experience for women; rather their experiences vary and are

significantly determined by race, class and national origin. Students benefit from a variety of

approaches to study women’s lives and gender expectations from a spectrum of disciplines.

Emphasis is placed on the concept that women have co-created knowledge with men from all

relevant academic areas. A common denominator for the development was strong links to

women’s movements, activism, feminist ideas and practices. The research agenda was

emancipatory, and the aim was to gather well founded scholarly arguments to further the

political work for change in society, science and culture.

The aim of Gender Studies was to generate a new field of knowledge production which could

gain impact on science and scholarly practices and theories. Against this background, a

critical and innovative approach to existing science and academic scholarship is one of the

characteristics of the subject area. The relationship between knowledge, power and gender

in interaction with other social divisions such as ethnicity, class, sexuality, nationality, age,

dis/ability, etc. is critically scrutinized in gender research.

12

Since the start in the 1970s, gender research has been inspired by and embedded in many

different and sometimes partly overlapping scholarly traditions, such as empiricism, marxism,

psychoanalysis, post structuralism, critical studies of men and masculinities, critical race theory,

critical studies of whiteness, inter sectionality and postcolonial theory, queer studies, lesbian,

gay, bi and trans studies (so-called LGBT studies), critical studies of sexualities, body theory,

sexual difference feminisms, black feminisms, ecological feminisms, animal studies,

feminist techno science studies, materialist feminisms. The field of study has grown and

expanded rapidly on a worldwide basis, and given rise to a diversity of specific national and

regional developments.

iii. Gender, economy and work participation

Think of the activities that take place in an average household during the course of a day. Food is

cooked; cleaning is done – sweeping, mopping, and dusting. Groceries and other household

items are purchased. Clothes are washed, dried, ironed. Sometimes household repairs are carried

out. Garbage is discarded. Also, the people who live in the house need to be looked after.

Sometimes they may have special needs – for example babies need constant supervision. These

are some of the things that are required to be done to keep homes functioning. These activities

take a lot of time, and many are to be done on a daily basis. The people who do them expend a

lot of energy and may be exhausted when they are finished. Most of the time, women perform

these tasks. Put together, these tasks are called housework. Given this name, it may be surprising

to learn that housework is not considered to be work in economic or social terms. It is seen as a

set of tasks that is naturally performed by the women of a household. It is not, for example,

calculated as part of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (the sum of all goods and services

produced in a country in a given period). This is in spite of the fact that if the women of the

house are unable or unwilling to do these tasks, other people will do them – but only if they are

paid to do so. Housework is not the only area in which women’s work is not recognized as work.

We would generally see two women rushing about the city, obviously very busy. But according

to the prevalent statistics, only a tiny fraction of women are in the workforce. The question that

is to be raised, then, is ‘why is the economic contribution of so many women seen as being

trivial?’ These examples reflect certain changes in viewpoint that are very significant from the

13

point of view of gender studies. They reflect a change in perspective – a change in the way

things are looked at.

Gender-smart jobs strategies need to identify and address multiple deprivations and constraints

that underlie gender inequality in the world of work. The constraints are most severe among

women who face other disadvantages, such as being a member of an ethnic minority, having a

disability, or being poor. Social norms are a key factor underlying deprivations and constraints

throughout the lifecycle. Norms affect women’s work by dictating the way they spend their time

and undervaluing their potential. Housework, child-rearing, and elderly care are often considered

primarily women’s responsibility. Further, nearly four in 10 people globally (close to one-half in

developing countries) agree that, when jobs are scarce, men should have more right to jobs than

women. Research shows that women are frequently disadvantaged by gender biases in

performance and hiring evaluations. Jobs can increase women’s agency, but a lack of agency

also restricts women’s job opportunities. In most developing countries, women have fewer

choices in fundamental areas of day-today life, including their own movements, sexual and

reproductive health decisions, ability to use household assets, and whether and when to go to

school, work, or participate in other economic-related activities. Further, a large proportion of

women in the world lack freedom from violence. The World Health Organization estimates that

more than 35 percent of women have experienced gender-based violence. Without addressing

these critical constraints on agency, women cannot take full advantage of potential economic

opportunities. In terms of wage employment, men tend to dominate manufacturing, construction,

transport and communications whereas women are concentrated in health, social work, and

education. Differences in education, training, preferences for job security, and the need for

flexible working hours help explain this segregation, alongside gender stereotyping. ILO analysis

shows that in both developed and developing economies women’s employment is most heavily

concentrated in occupations such as clerks and service and retail sales workers. In contrast,

men’s employment dominates in crafts, trades, plant and machine operations, and managerial

and legislative occupations. The informal economy is an important job source for women and

men in developing countries, and a major contributor to national economies. Estimates show that

informal employment comprises one-half to three-quarters of non-agricultural employment in

developing countries. Yet gender gaps in earnings and opportunities tend to be particularly stark

within the informal economy. Gender sorting into different types of work reinforces disparities in

14

earnings and vulnerability and responds to multiple constraints. For example, women’s lack of

access to property and financial services poses barriers to formal firm creation. Government

corruption, time-intensive bureaucracy, high tax rates, and lack of flexibility in the formal sector

can push women into the informal economy. Domestic responsibilities and restricted mobility

also limit women’s ability to participate in higher paying activities farther from home. Gender

differences in levels of literacy, education, skills, and aspirations further contribute to gaps.

Given women’s concentration into lower-paying and more vulnerable work, gender-sensitive

policies are often needed to extend social protection to those in the informal economy— both to

mitigate vulnerability and to ensure that safety nets, public works, and other social services

benefit vulnerable women. Collective action plays a particularly important role in filling voids in

voice, representation, and support where formal organizing structures and protections are

otherwise lacking.

Most of the pay gap in wage work is due to differing jobs and hours. Women and men earn

different wages primarily because of different types of work. The ILO, for example, documents

substantial earnings differences between male-dominated and female-dominated occupations.

The implication is that labour policies, such as minimum wages and anti-discrimination

regulations, may help in some cases but will not be enough to erase gaps, and longer-term

strategies are needed to reduce gender sorting into different types of jobs and firms. Nonetheless,

women earn less than men even when controlling for industry and occupation.

Female-owned businesses are generally smaller and employ fewer people. The Global

Entrepreneurship Monitor indicates that women are more likely than men to run single-person

businesses without any employees.

Jobs boost self-esteem and pull families out of poverty. Yet gender disparities persist in the

world of work. Closing these gaps, while working to stimulate job creation more broadly, is a

prerequisite for ending extreme poverty and boosting shared prosperity. Gender equality in the

world of work is a win-win on many fronts. It has been estimated that raising female

employment to male levels could have a direct impact on GDP of various countries taking into

account losses in economy-wide labor productivity that could occur as new workers entered the

labor force. Yet almost half of women’s productive potential globally is unutilized according to

the International Labour Organization. In places where women’s paid work has increased, as in

15

Latin America and the Caribbean, gains have made significant contributions to overall poverty

reduction. Gender equality in the world of work is multidimensional. Broadly, key dimensions

include labor force participation, employment, firm and farming characteristics, earnings, and

job quality. The last is the most difficult to measure and varies by context. However, full-time

wage employment is a strong predictor of subjective well-being, and jobs that provide higher

earnings, benefits, rights, and opportunities for skills development are more likely to expand

women’s agency.

On virtually every global measure, women are more economically excluded than men. Trends

suggest that women’s labor force participation (ages 15–64) worldwide over the last two decades

has stagnated, declining from 57 to 55 percent globally. Gender gaps are evident among farmers,

entrepreneurs, and employees alike. Because of gender-specific constraints, female farmers tend

to have lower output per unit of land and are less likely to be active in commercial farming than

men. Female entrepreneurs typically operate smaller firms and in less profitable sectors. Female

employees are more likely to work in temporary and part-time jobs, are less likely to be

promoted, and are concentrated in occupations and sectors with lower barriers to entry. Women

and girls also do the vast majority of unpaid care and housework. Women generally earn less

than men. ILO analysis of 83 countries shows that women in paid work earn on average between

10 and 30 percent less than men. Gender sorting into different jobs, industries, and firm types

explains much of the pay gap. Throughout the world, women are concentrated in less-productive

jobs and run enterprises in less-productive sectors, with fewer opportunities for business scale-up

or career advancement. The patterns that foster low labor force participation, earning gaps, and

occupational segregation begin early in life and accumulate over time. If girls marry early and

drop out of school, they will have a harder time catching up to their male counterparts in

adulthood, even with increased access to capital or progressive labour regulations. If social

norms and educational streaming limit girls’ opportunities and aspirations to become engineers,

doctors, or business executives early in life, then the female talent pool for these occupations will

automatically be smaller in the next generation of workers. Although framing gender equality in

the context of a lifecycle approach is not new. It merits renewed attention here in light of

findings related to norms and agency. Both the agency and lifecycle perspectives reinforce the

message that overcoming gender inequality will not result from specific, isolated programs, but

from a comprehensive approach that involves multiple sectors and stakeholders. Jobs tend to

16

improve with development, and gender inequality is sometimes seen as a symptom of low

development, it is sometimes assumed that policy makers should focus on economic growth and

gender equality in work will inevitably improve. Some theoretical arguments suggest that market

competition can drive out discrimination against women by firms as it is inefficient and hence

costly. As more women enter wage jobs that are more stable and higher paying, they can help to

fuel economic growth, while growth brings more urbanization and wage jobs that move women

out of unpaid and less productive work.

Two recent global reviews investigated directions of influence between economic growth and

gender equality. Duflo (2011) found that, although economic development and women’s

empowerment are closely correlated, the connections between the two are too weak to expect

that pulling one lever will automatically pull the other. Kabeer and Natali (2013) found that

increased gender equality, especially in education and employment status, contributes

significantly to economic growth, but that evidence on the effects of economic growth on gender

equality was less consistent. The type of growth matters, as do the policies (or lack thereof) for

more inclusive growth. In urbanizing countries, for instance, women tend to benefit more from

growth in light manufacturing. In East Asia, growth in the manufacturing sector—particularly in

textile and food services industries—has increased women’s wage work and improved female

and child health and education outcomes.

At the same time, the drive for global competitiveness reinforced occupational segregation and

downward pressure on women’s wages. Natural resource–driven growth has had few or mixed

results for gender equality. Education is critical for increasing girls’ opportunities. Schooling is

one of the most powerful determinants of young women’s avoidance of early marriage and

childrearing. Progress in school enrollment, particularly at the primary level, has helped advance

gender equality and women’s empowerment—though gaps persist.

iv. Gender, globalization and education

Globalization is an important development that changed deeply the world in modern history. It is

seen that a new era starts and nations face huge changes in their social, economic and cultural

ways, and it is obvious that it comes into our society new concepts and values and they carry

new problems and perspectives for the nations in the process of globalization. In global world,

17

information society is an important concept, it needs creative individuals, and governments

should only train in school the individuals to adopt the new values and developing student’s

ability to acquire, and use knowledge gains importance in the process of globalization. However,

learners can develop their critical thinking skills, obtain democratic values and ethics and apply

their knowledge independently in an effectively designed teaching-learning environment.

Additionally, future universities and other institutions are not thought only for the young, they

are expected to become more open to people of all ages who wish to further their education, this

is inevitable in the globalized world.

Globalization has a close relation with education. As education has an important place in shaping

a society, globalization has to be connected with education and the global activities have a deep

impact on it. Globalization of the world economies is leading to increase emphasis on

internationalization of the subjects included in a course of study in school. It also creates the

opportunities for new partnerships in research and teaching with agencies and institutions across

the world (Twiggs and Oblinger, 1996). Globalization is one of most powerful worldwide forces

that are transforming the basis of business competition, paradoxically harkening an era in which

small, local communities of practice may lead to a prominent structural form. New challenges

force social, economic and cultural values. In the field of education a lot of changes are expected

duties of schools is to ameliorate the individual’s appropriateness with the concept of

globalization that changes traditional structure of education, which is one of the main rapid

changes today in universities and other institutions that are redoubling their efforts to respond to

social change. Gordon outlines the importance of higher education in the learning society by

attributing the report of the National Committee of Inquiry into Higher Education as follows:

“Higher education is principal to the social, economic and cultural health of the nation. It will

contribute not only through the intellectual development of students and by preparing them for

work, but also by adding to the world’s store of knowledge and understanding,..” (Gordon,

1999). In this quotation, Gordon said that Higher Education is very important in different

domains and it contributes in the promotion of students’ knowledge; and helping them to

integrate in job fields. Students are both consumers of provided classes and partners in the

process of learning. They evaluate their experiences in higher education and may thought of its

quality simply in terms of what it was available of them. They might neglect the degree to which

they were obliged to study material that would later be of value, or the extent that they were

actually encouraged to take responsibility for their learning For the employer, the totality of

18

attributes of the higher education experience that were important to the students learning recede

to the background, and it is the totality of students attributes that are important to the satisfaction

of perceived needs. The focus of learning systems should be on both the local and global society.

To know the circumstances, consumers expect the learning system needs and opportunities in

both. Educators who accept their special responsibility for the future they are needed by

consumers to study and know about the future, while leading positive, proactive change by

modeling it. Preparation and practice are needed by education consumers for life-long learning

the skills for continuous, self-directed learning, a consciousness of learning opportunities;

methods for managing their own learning and awareness of their rights and responsibilities as

consumer of education and training services. Consumers want a system that is a system of

coherent, coordinated system resources, processes and outcomes for learning opportunities and

knowledge of all form of learning. New challenges are facing the consumers or the learners of

education, old or primitive ways of teaching and schooling changed deeply. In maintaining

learning activities, students have different choices.

Globalization must be considered because “it is the underlying structural dynamics that drives

social, political, economic, and cultural processes around the world” (Robinson, 2003). And

gender because it is constitutive of most social relations and a common ground on which to

construct power on a daily basis. Though gender might work as a contingent element of reality, it

is present in all spheres of society and most moments of social life. Gender and power go

together, with masculinity holding a steady advantage under most circumstances. Gender,

however, is proving to be an increasingly complex concept because it presents multiple forms as

it intersects with other powerful social markers. It is clear that we need to analyze with greater

specificity the linkages between gender and other forms of subordination such as ethnicity, race,

and social class. The importance of their crosscutting nature is being recognized under the frame

of intersectoral analysis or intersectionality, which was defined at the 2001 World Conference

Against Racism (in Durban, South Africa), as “compound discrimination, double or multiple

discrimination.” Intersectoral analysis becomes crucial in these times of globalization for it

enables us to see under what conditions the exclusion of women is deepened.

Globalization is a concept that everyone uses and, consequently and not surprisingly, it has

acquired multiple meanings. Some observers focus on the interconnectedness among people and

countries that is becoming ever wider, deeper, and faster. Through technologies such as DVDs,

19

laptop computers, storage media, Internet, satellite TV, cellular telephones, and

videoconferencing, globalization creates spectacular opportunities for increasing the

dissemination of information and dialogue. The increased communication contributes toward a

more interactive world, one in which communication and transactions can emerge between

people who may never meet. There is indeed a shift toward the compression of time and space

with today’s information and transportation technologies. The Internet, in particular, permits

instantaneous personal dialogue and communication. This inexpensive means of communication

has been particularly helpful to people of all gender who now are able to exchange ideas on a

regular basis with colleagues from both the South and the North. The considerable flow of

information, however, does not equate communication with knowledge or wisdom. The

information received through the Internet, for instance, must still be digested and put into an

analytical framework. Further, the world evinces inequality in the access to telecommunications

that may change over time. To call ourselves a ‘network society’ highlights the relevance of

technology and acknowledges the significant contributions of fast and inexpensive

communication to needed social action but implies a much more even distribution of knowledge

and access to technology than is the case at present. Globalization today is much more than

technology. The advances in technology have both facilitated and been affected by new

economic strategies – a position that strongly promotes market-led decision-making.

Globalization presumably gives everyone an equal chance if each individual just improves his or

her educational levels. Overall, levels of education have increased throughout the world. But we

are seeing that globalization is not eliminating the persistent oligarchic and patriarchal forces that

prevent women from moving into spheres of economic and political power. The schooling that

is provided in practically all countries addresses gender ideologies only marginally (if at all) and

is thus not able to counter them. The prevailing norms, practices, rules, regulations do not permit

serious efforts to use gender as a crosscutting theme and mechanism in public policy or in the

labour market to provide attention to the redressing of inequalities between women and men and

to the diminution of the femininity-masculinity polarity.

20

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Class 11th - Business StudiesDokumen4 halamanClass 11th - Business StudiesNihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

- Exam Slot Nursery GDokumen2 halamanExam Slot Nursery GNihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

- Class 9th Social Science. Final Examination 2023Dokumen4 halamanClass 9th Social Science. Final Examination 2023NihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

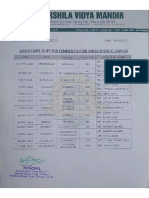

- Fro-Rat (Toto) 74Ht5/37 4Te4/Ifaat Frgfam/Fasr/2022-23: At5 FTT FahttDokumen9 halamanFro-Rat (Toto) 74Ht5/37 4Te4/Ifaat Frgfam/Fasr/2022-23: At5 FTT FahttNihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

- Document House CaptainDokumen3 halamanDocument House CaptainNihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

- Document (TrueScanner) 2022-3-25 10.6.5Dokumen1 halamanDocument (TrueScanner) 2022-3-25 10.6.5NihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

- Accounts Pre Board IiDokumen9 halamanAccounts Pre Board IiNihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

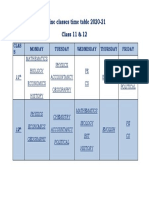

- Online Classes Time Table 2020-21 Class 9 & 10: Class Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday SaturdayDokumen1 halamanOnline Classes Time Table 2020-21 Class 9 & 10: Class Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday SaturdayNihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

- ONLINE TIME - TABLE (CLASS 1st - 12th)Dokumen6 halamanONLINE TIME - TABLE (CLASS 1st - 12th)NihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

- 10 - Term-II - Pre Board - II - 2021-22Dokumen4 halaman10 - Term-II - Pre Board - II - 2021-22NihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

- SDK LogDokumen432 halamanSDK LogNihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

- Online Classes Time Table 2020-21 Class 11 & 12: Clas S Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday FridayDokumen1 halamanOnline Classes Time Table 2020-21 Class 11 & 12: Clas S Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday FridayNihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

- PooyaTafsir Quran Surah41 45 PDFDokumen58 halamanPooyaTafsir Quran Surah41 45 PDFNihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

- Class 10th EconomicsDokumen4 halamanClass 10th EconomicsNihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

- Business Studies Home Assignment Class 11Dokumen1 halamanBusiness Studies Home Assignment Class 11NihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

- BST HW Class 12thDokumen1 halamanBST HW Class 12thNihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

- Online Classes Time Table 2020-21 Class 11: Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday SaturdayDokumen2 halamanOnline Classes Time Table 2020-21 Class 11: Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday SaturdayNihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

- PDF PDFDokumen13 halamanPDF PDFNihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

- SSTDokumen4 halamanSSTNihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

- Self Assessment ReportDokumen7 halamanSelf Assessment ReportNihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

- Self Assessment ReportDokumen10 halamanSelf Assessment ReportNihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

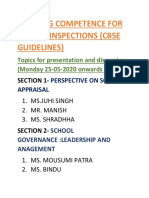

- Building Competence For School Inspection (Teachers Discussion)Dokumen4 halamanBuilding Competence For School Inspection (Teachers Discussion)NihalSoni100% (1)

- Material Downloaded From - 1 / 4Dokumen4 halamanMaterial Downloaded From - 1 / 4NihalSoniBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Regional LGBTI Survey For PublishingDokumen36 halamanRegional LGBTI Survey For PublishingAineBelum ada peringkat

- Intersecting The Academic Gender GapDokumen99 halamanIntersecting The Academic Gender GapAlia RamosBelum ada peringkat

- Mangagoy, Bislig City: Andres Soriano Colleges of BisligDokumen9 halamanMangagoy, Bislig City: Andres Soriano Colleges of BisligDarioz Basanez LuceroBelum ada peringkat

- Attachment Style and Sexual Permissiveness The Moderating Role of GenderDokumen5 halamanAttachment Style and Sexual Permissiveness The Moderating Role of GenderMohd Saifullah Md SabriBelum ada peringkat

- Full Download Book The Psychology of Women and Gender PDFDokumen41 halamanFull Download Book The Psychology of Women and Gender PDFmichael.gheen245100% (16)

- Article Homosexuality and Scientific Evidence: On Suspect Anecdotes, Antiquated Data, and Broad GeneralizationsDokumen27 halamanArticle Homosexuality and Scientific Evidence: On Suspect Anecdotes, Antiquated Data, and Broad GeneralizationsPhạm Ngọc Hoàng MinhBelum ada peringkat

- Riddle SCALES ExplanationDokumen2 halamanRiddle SCALES ExplanationSandro MacassiBelum ada peringkat

- A Content Analysis of LGBTQ QualitativeDokumen11 halamanA Content Analysis of LGBTQ Qualitativeprocrast3333Belum ada peringkat

- Definition of LGBTQDokumen9 halamanDefinition of LGBTQGerrel Lloyd DistrajoBelum ada peringkat

- Research Proposal First DraftDokumen2 halamanResearch Proposal First DraftRachelBelum ada peringkat

- Gender Criticism What Isn't GenderDokumen18 halamanGender Criticism What Isn't GenderLuis CaceresBelum ada peringkat

- Human Sexuality: Augusto "Jojo" Cruz JR, MD DPBP UERMMMC Department of PsychiatryDokumen53 halamanHuman Sexuality: Augusto "Jojo" Cruz JR, MD DPBP UERMMMC Department of Psychiatryhippiekatie100% (1)

- Deconstructing Sex and Gender - Thinking Outside The BoxDokumen32 halamanDeconstructing Sex and Gender - Thinking Outside The BoxViviane V CamargoBelum ada peringkat

- (Vicki L. Eaklor) Queer America A GLBT History of PDFDokumen308 halaman(Vicki L. Eaklor) Queer America A GLBT History of PDFHannah100% (1)

- The Sexual Self: Jeramel Ray Chester T. ManaloDokumen77 halamanThe Sexual Self: Jeramel Ray Chester T. ManaloJeramel Teofilo Manalo33% (3)

- The Rainbow ProjectDokumen13 halamanThe Rainbow ProjectAkemi Diana Sanchez ChoquepataBelum ada peringkat

- A1.4 - UcspDokumen2 halamanA1.4 - UcspGrenlee KhenBelum ada peringkat

- My Genes Made Me Do ItDokumen262 halamanMy Genes Made Me Do ItKlaus Von KonstantinBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding The Psychological Dynamics of Selected Filipino TransgendersDokumen14 halamanUnderstanding The Psychological Dynamics of Selected Filipino TransgendersAllen Ray LedesmaBelum ada peringkat

- Wah Shan2001Dokumen22 halamanWah Shan2001320283095Belum ada peringkat

- Sexuality and Responsible ParenthoodDokumen3 halamanSexuality and Responsible Parenthoodsarguss14Belum ada peringkat

- Body and Human SexualityDokumen17 halamanBody and Human SexualityTuangpu SukteBelum ada peringkat

- Sexuality NotesDokumen18 halamanSexuality NotesMj BrionesBelum ada peringkat

- Position Paper (Sogie Bill)Dokumen2 halamanPosition Paper (Sogie Bill)Judy Ann ArabaBelum ada peringkat

- Section OverviewDokumen19 halamanSection OverviewWill PageBelum ada peringkat

- Magalang Christian Ecuemenical School, IncDokumen5 halamanMagalang Christian Ecuemenical School, Increuben tanglaoBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 5 Audience AnalysisDokumen33 halamanChapter 5 Audience AnalysisJodieBowersBelum ada peringkat

- Gsa Handout PDFDokumen2 halamanGsa Handout PDFapi-267993711Belum ada peringkat

- GenderSociety Midterm ReviewerDokumen7 halamanGenderSociety Midterm ReviewerIrish MaeBelum ada peringkat