ACOG Committee Opinion No694

Diunggah oleh

Marco DiestraHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

ACOG Committee Opinion No694

Diunggah oleh

Marco DiestraHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

COMMITTEE OPINION

Number 694 • April 2017

Committee on Gynecologic Practice

American Urogynecologic Society

This Committee Opinion was developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Gynecologic

Practice and the American Urogynecologic Society.

This document reflects emerging clinical and scientific advances as of the date issued and is subject to change. The information

should not be construed as dictating an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed.

Management of Mesh and Graft Complications in

Gynecologic Surgery

ABSTRACT: This document focuses on the management of complications related to mesh used to correct

stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse. Persistent vaginal bleeding, vaginal discharge, or recur-

rent urinary tract infections after mesh placement should prompt an examination and possible further evalua-

tion for exposure or erosion. A careful history and physical examination is essential in the diagnosis of mesh

and graft complications. A clear understanding of the location and extent of mesh placement, as well as the

patient’s symptoms and therapy goals, are necessary to plan treatment approaches. It is important that a treating

obstetrician–gynecologist or other gynecologic care provider who seeks to revise or remove implanted mesh be

aware of the details of the index procedure. Diagnostic testing for a suspected mesh complication can include

cystoscopy, proctoscopy, colonoscopy, or radiologic imaging. These tests should be pursued to answer specific

questions related to management. Given the diverse nature of complications related to mesh-augmented pelvic

floor surgery, there are no universal recommendations regarding minimum testing. Approaches to management

of mesh-related complications in pelvic floor surgery include observation, physical therapy, medications, and

surgery. Obstetrician–gynecologists should counsel women who are considering surgical revision or removal of

mesh about the complex exchanges that can occur between positive and adverse pelvic floor functions across

each additional procedure starting with the device implant. Detailed counseling regarding the risks and benefits

of mesh revision or removal surgery is essential and can be conducted most thoroughly by a clinician who has

experience performing these procedures. For women who are not symptomatic, there is no role for intervention.

Recommendations • A trial of vaginal estrogen can be attempted for small

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (eg, less than 0.5-cm) mesh exposures.

and the American Urogynecologic Society make the fol- • Persistent vaginal bleeding, vaginal discharge, or

lowing recommendations: recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs) after mesh

placement should prompt an examination and pos-

• Short-term voiding dysfunction after placement of sible further evaluation for exposure or erosion.

a synthetic midurethral sling is common and, if • Pelvic pain (including dyspareunia), possibly related

improving, can be managed expectantly for up to to nonexposed mesh, is complex, may not respond

6 weeks. However, retention (inability to empty the to mesh removal, and should prompt referral to a

bladder) or small-volume voids with large post- clinician with appropriate training and experience,

void bladder residual volume should receive earlier such as a female pelvic medicine and reconstructive

intervention. surgery specialist.

• Asymptomatic exposures of monofilament macro- • Mesh removal surgery should not be performed

porous meshes can be managed expectantly. unless there is a specific therapeutic indication.

The purpose of this document is to provide obstetrician– ways. The surface area of implanted mesh material also

gynecologists with guidance on how to manage simple varies across surgical approaches and devices. Although

mesh complications. This document also suggests when each device is designed to secure the supporting mesh to

referral to a clinician with appropriate training and specific pelvic structures, the result can be variable. Some

experience, such as a female pelvic medicine and recon- pelvic structures that have been used to secure mesh

structive surgery specialist, is indicated for mesh compli- include the sacrospinous ligament, sacrotuberous liga-

cations related to vaginal prolapse surgery. ment, obturator membrane, and adductor compartment

muscles, as well as the anterior longitudinal ligament.

Background and General Principles Pelvic structures can be injured during or after surgeries

In gynecologic surgery, grafts or mesh may be used when in which mesh is used. Examples of these structures are

the surgical procedure requires the use of bridging mate- the sacrum (1), bladder (2), and rectum (3). Diagnostic

rial to reinforce native structures. The term “graft” refers testing for a suspected mesh complication can include

to a biological material that comes from either a human cystoscopy, proctoscopy, colonoscopy, or radiologic

or an animal (xenograft). Autologous grafts can be har- imaging. These tests should be pursued to answer spe-

vested from the same person, whereas allografts come cific questions related to management. Given the diverse

from human donors or cadavers. In gynecologic surgery, nature of complications related to mesh-augmented

mesh refers to synthetic material (usually polypropylene). pelvic floor surgery, there are no universal recommenda-

Because of complications attributed to multifilament and tions regarding minimum testing.

small-pore-size synthetic mesh, type 1 synthetic meshes

General Principles of Management of

(monofilament with large pore size) currently are used

in the United States. This document focuses on the Mesh and Graft Complications

management of complications related to mesh used to Approaches to management of mesh-related complica-

correct stress urinary incontinence (SUI) or pelvic organ tions in pelvic floor surgery include observation, physical

prolapse (POP). therapy, medications, and surgery. Table 1 presents an

overview of specific mesh and graft complications and

Clinical Presentations of management options. There may be settings in which

Complications observation of exposed mesh is reasonable (4). Surgical

intervention or referral is not always necessary for type

Vaginal mesh exposure may be entirely asymptom- 1 (monofilament and macroporous) mesh exposures

atic. Alternatively, vaginal mesh exposure can produce into the vagina. Asymptomatic exposures of monofila-

symptoms such as spotting or bleeding, discharge, pain, ment macroporous meshes can be managed expectantly.

or pain with sex (for the patient or partner). Persistent For women with symptoms, a trial of vaginal estrogen

vaginal bleeding, vaginal discharge, or recurrent UTIs can be attempted for small (eg, less than 0.5 cm) mesh

after mesh placement should prompt an examination and exposures. Topical estrogen may improve or resolve the

possible further evaluation for exposure or erosion. Pain mesh exposure, though there is little prospective, com-

can be constant or associated only with activity (eg, sex). parative evidence supporting this approach. A period of

Furthermore, pain often is complex and multifactorial 6–12 weeks is a reasonable period to try topical estrogen.

and may require a multidisciplinary approach. One multicenter study of mesh complications after

reconstructive surgery found that 60% of women required

Diagnostic Evaluation for Mesh and two or more interventions and that the first intervention

Graft Complications was surgical in approximately one half of cases (5). These

A careful history and physical examination is essential procedures are complex and should be approached with

in the diagnosis of mesh and graft complications. In the caution. Surgeons who are unfamiliar with the original

context of POP, grafts and mesh can be placed abdomi- index procedure or the management issues that follow

nally (eg, sacrocolpopexy) or transvaginally (eg, mesh- should refer the patient to a surgeon who is familiar with

augmented apical, anterior and, rarely, posterior repairs). these types of repairs.

A clear understanding of the location and extent of mesh

placement, as well as the patient’s symptoms and therapy Informed Consent

goals, are necessary to plan treatment approaches. It is The obstetrician–gynecologist should counsel women

important that a treating obstetrician–gynecologist or who are considering surgical revision or removal of mesh

gynecologic care provider who seeks to revise or remove about the complex exchanges that can occur between

implanted mesh be aware of the details of the index pro- positive and adverse pelvic floor functions across each

cedure. Prior operative reports are often the best source additional procedure starting with the device implant.

for obtaining this information. Operative reports from Detailed counseling regarding the risks and benefits of

prior attempts to revise or remove the implanted mate- mesh revision or removal surgery is essential and can be

rial also should be reviewed. Mesh may be implanted conducted most thoroughly by a clinician who has expe-

into pelvic anatomical structures in a number of different rience performing these procedures.

2 Committee Opinion No. 694

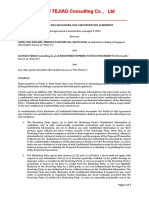

Table 1. Overview of Mesh and Graft Complications After Gynecologic Surgery and Suggested Management

Procedure Most Commonly

Complication Associated With Complication Suggested Management

Urinary retention or prolonged voiding disorder MUS or pubovaginal sling • Place urethral catheter

or obstructive symptoms • Teach intermittent catheterization

• Consider sling release

Vaginal mesh exposure MUS, TVM, or ASC • Observation

(asymptomatic and type 1 mesh) • Topical estrogen

• If the mesh is multifilament, then referral to

a clinician with appropriate training and

experience*

Vaginal mesh exposure (symptomatic) MUS, TVM, or ASC • Topical estrogen

• If topical estrogen fails, referral to a clinician

with appropriate training and experience*

Organ erosion (bladder, rectum) MUS, TVM, or ASC Referral to a clinician with appropriate training

and experience*

Pain MUS, TVM, or ASC Referral to a clinician with appropriate training

and experience*

Dyspareunia MUS, TVM, or ASC Referral to a clinician with appropriate training

and experience*

Bowel dysfunction TVM or ASC Referral to a clinician with appropriate training

and experience*

Sacral osteomyelitis or discitis ASC Referral to a clinician with appropriate training

and experience*

Abbreviations: ASC, abdominal sacral colpopexy; MUS; midurethral sling; TVM, transvaginal mesh.

*Such as a female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery specialist

Complications: Midurethral Sling edema, anesthetic effects, opiates, pain, or outlet obstruc-

Substantial safety and efficacy data support the role of tion. Most incomplete bladder emptying after midure-

synthetic mesh midurethral slings as a primary surgical thral sling placement is self-limited and resolves with

treatment option for female SUI (6). However, mesh- expectant management. In a prospective, randomized

related complications can occur. surgical trial of 600 women undergoing midurethral sling

surgery, the frequency of incomplete bladder emptying

Voiding Disorders was 20% on postoperative day 1, 6% at 2 weeks, and 2% at

Management of incomplete voiding after midurethral 6 weeks (7). Very few women in this trial underwent sling

sling placement is dependent on the underlying etiology. release surgery. In women with normal baseline voiding,

In general, prompt treatment of incomplete voiding is most voiding dysfunction after midurethral sling surgery

important to relieve patient discomfort and to prevent will resolve spontaneously.

complications related to increased bladder pressures. A trial of void before discharge from the hospital

Voiding dysfunction can occur after any type of proce- can help determine early in the postoperative course if

dure to address incontinence. This document will focus a patient is at risk of overdistention. If a patient is found

on treatment with a midurethral sling. to have postoperative voiding difficulty, she should be

treated conservatively with indwelling catheterization or

Short-Term Voiding Dysfunction clean intermittent self-catheterization to prevent overdis-

Short-term voiding dysfunction after placement of a tention. Bladder overdistention can cause stretch injury,

synthetic midurethral sling is common and, if improv- prolonging the time needed for catheterization. Clean

ing, can be managed expectantly for up to 6 weeks. intermittent self-catheterization is preferred for patient

However, retention (inability to empty the bladder) or convenience (and often comfort) and a lower overall

small-volume voids with large postvoid bladder residual infection risk (8). However, for women who are unable

volume should receive earlier intervention. New onset to perform clean intermittent self-catheterization, a

voiding difficulty after midurethral sling surgery often is temporary indwelling catheter is an option. Suppressive

transient, and etiologies may include periurethral tissue antibiotics are not indicated during this time (8, 9).

Committee Opinion No. 694 3

Urinary tract infection can be triaged and treated per uted to the midurethral sling, the most important factor

routine recommendations. being the temporal relationship. If a patient is voiding

Among women performing clean intermittent self- normally before an incontinence sling placement and

catheterization, once postvoid bladder residual volume afterward is having voiding difficulty, the etiology is likely

measures less than 150 mL on three consecutive occa- the sling.

sions, assisted bladder drainage can stop. Patients who At a minimum, diagnostic testing should include

require indwelling catheters for assisted bladder drain- obtaining a postvoid residual volume. Noninvasive uro-

age should have continuous drainage with voiding tri- flow testing can assess voiding pattern and maximum

als weekly until the residual volume measures less than flow rates. Filling cystometry can assess detrusor function

150 mL. If the patient demonstrates continuous improve- during filling, and pressure-flow studies assess detrusor

ment (a decrease) in residual volume over time, it is pressures during voiding. Low flow rates with high detru-

reasonable to monitor her progress for up to 6 weeks; sor pressures are suggestive of bladder outlet obstruction.

however, if the residual volume remains persistently high Voiding diagnoses that are based on multichannel uro-

(greater than 150 mL) at 6 weeks, sling release should be dynamic studies lack precision, so interpretation of these

considered. In a patient with significant voiding dysfunc- studies must be considered cautiously (12). Cystoscopy

tion (eg, retention [unable to void at all], or if the patient may be considered if there is any suspicion of mesh

is only voiding 50 mL or 100 mL with high postvoid erosion.

bladder residual volume) who has not experienced a The treatment for long-term voiding dysfunction

distention injury, the obstetrician–gynecologist or other due to outlet obstruction after a midurethral sling proce-

gynecologic care provider should consider a sling loosen- dure is a sling release. A small incision is made in the pre-

ing or sling release after approximately 2 weeks. vious incision site or an anterior vaginal sulcus, the full

Recurrent SUI after sling release for obstruction width of the sling is isolated completely, an instrument

occurs in approximately 40% of women (10). In one case is placed beneath the sling, and the sling is transected.

series of 23 women undergoing tension-free vaginal tape Notably, sling release may not resolve the voiding dys-

release for voiding dysfunction, 61% of women remained function completely if the patient has baseline impaired

continent 6 weeks after the release procedure, 26% detrusor function.

reported improvement in SUI symptoms from baseline,

and 13% had recurrence of their SUI (10). In another Vaginal Mesh Exposure

series that included 107 women, 49% of women reported Mesh exposure after a midurethral sling procedure occurs

recurrent SUI and 14% underwent repeat surgery for SUI in 1–2% of cases (13). Expectant management of exposed

after sling release (11). It remains unclear whether timing vaginal mesh, with or without topical estrogen, can be

of the sling release (early versus late) has an effect on SUI appropriate in asymptomatic patients who have type 1

outcomes. mesh. Small case reports document that spontaneous reep-

ithelialization can occur (14). If topical estrogen therapy

Long-Term Voiding Dysfunction is not successful, consideration can be given to surgically

Referral to a clinician with appropriate training and expe- excising the edges of the vaginal incision and reapproxi-

rience, such as a female pelvic medicine and reconstruc- mating the fresh incision edges. Care should be taken

tive surgery specialist, is recommended for suspected to ensure a tension-free closure and everting of the vag-

long-term voiding dysfunction (typically 3 months or inal edges. There are few published success rates for

longer) after a midurethral sling placement. Bladder primary reclosure; however, it is considered to be a low-

outlet obstruction from a midurethral sling can result risk procedure.

in high-pressure voiding that leads to ureteral reflux, If expectant management with estrogen therapy and

upper tract dilation, deterioration of renal function, primary reclosure is unsuccessful and preservation of the

and detrusor decompensation. Evaluation includes a sling remains the patient’s preference, there are few data

complete history about the prior procedures and obtain- to guide patient decision making. Approaches described

ing data about the type of anti-incontinence procedure in case reports for preserving a functioning but exposed

performed. Baseline voiding patterns or studies and any midurethral sling include full thickness autologous graft

subsequent multichannel urodynamic testing results, transposition and Martius graft transposition (15, 16).

including emptying studies, also should be reviewed. If approaches for sling preservation are unsuccessful

It is important to inquire about general health issues and the patient is still symptomatic, sling excision can

that can affect voiding function, such as diabetes, con- be performed; however, there is a risk of recurrent SUI.

stipation, or neurologic disease. The physical examina- Excision of the entire mesh usually is not necessary.

tion should include a pelvic examination to assess for

pelvic floor muscle dysfunction or POP. Neurologic Bladder and Urethral Erosion of

etiologies also should be considered. It is important to Midurethral Sling

try to distinguish the underlying etiology of the voiding In the event of mesh erosion into the bladder or ure-

dysfunction and determine how much of it can be attrib- thra, referral to a specialist familiar with reconstructive

4 Committee Opinion No. 694

techniques is warranted. Intravesical mesh erosion can be experience, such as a female pelvic medicine and recon-

associated with adherent calculi, making extraction of the structive surgery specialist, is recommended.

mesh through minimally invasive approaches difficult.

The specialist may consider the following techniques: Vaginal Mesh Exposure

combined laparoscopic and cystoscopic excision of the Although management of mesh exposure for transvagi-

portion of eroded mesh in the bladder (17); combined nally placed mesh for POP is similar to that for midure-

vaginal and laparoscopic approaches (18); or using assis- thral sling, the involved anatomy and volume of mesh

tance from ear, nose, and throat instruments to avoid the varies. Given these differences, among symptomatic

need for urethrotomy (19). patients (those reporting pain, bleeding, or partner dys-

pareunia), referral to an obstetrician–gynecologist with

Pain appropriate training and experience, such as a female

Pain after a midurethral sling procedure requires a pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery specialist

focused and systematic examination of the pelvic skeletal who is familiar with managing these complications, is

and muscular anatomy to localize the specific structures recommended.

associated with the patient’s pain. It is important to

determine levator tone and tenderness as a potential con- Pain

tributing factor to the patient’s pain. Conservative man- Similar to when pain is associated with a midurethral

agement of mesh-associated pain can include physical sling, a detailed and systematic examination should be

therapy and trigger-point injections. When conservative performed to localize the anatomy involved in the pain

options are unsuccessful, sling excision may be an option. (including contributing anatomy, such as the levator

Excision can include all or part of the mesh, but it is not muscles) and determine how it relates to the mesh pro-

uncommon for the mesh to be implanted into struc- cedure. Pain-related reports are complicated and often

tures that are difficult to access surgically. For example, multifactorial. These issues may require multidisciplinary

mesh implanted into the adductor compartment of the management and are not always entirely responsive

lower extremity can be hard to identify and remove (20). to treatment. Prolonged pain can become centralized

Notably, incomplete removal can make future surgical (eg, pain that is not localized to peripheral anatomy

attempts, if required, more complicated; thus, the first or trauma). Pelvic pain (including dyspareunia), pos-

attempt should be well planned. sibly related to nonexposed mesh, is complex, may not

respond to mesh removal, and should prompt referral

Pubovaginal Slings With Autologous to a clinician with appropriate training and experience,

or Other Biologic Grafts such as a female pelvic medicine and reconstructive

Voiding disorders may be more common after pubovagi- surgery specialist. Poor understanding of chronic pain

nal sling procedures than after midurethral sling proce- management complicates pain control that is attributed

dures, although management is similar. Vaginal exposure to transvaginal mesh (22). Pelvic floor physical therapy,

and erosion are less common with autologous or biologic trigger-point injections, and medications designed to

grafts than with synthetic mesh. disrupt or alter peripheral or central pain transmission

are potentially helpful conservative options.

Complications: Transvaginal Mesh for Surgery may be an option, but patients should be

Prolapse counseled that successful pain and dyspareunia outcomes

Pelvic organ prolapse vaginal mesh repair should be lim- after surgery are not uniform. The ideal timing of surgery

ited to high-risk individuals in whom the benefit of mesh cannot be estimated from the available data, although

placement may justify the risk. This includes individuals there are hypothetical and experiential reasons to favor

with recurrent prolapse (particularly of the anterior or earlier intervention (23). Surgery may involve extensive

apical compartments) or with medical comorbidities that dissection and collaboration with other medical special-

preclude more invasive and lengthier open and endo- ties, such as urology, colorectal surgery, or pain manage-

scopic procedures (21). ment. Outcomes of mesh revision surgery are variable

(24–26). Many short-term case series describe positive

Wound Complications: Noninfectious and functional outcomes (24, 25, 27–29), though recurrent

Infectious prolapse or urinary incontinence can occur in up to one

Noninfectious wound complications after transvaginal third of cases (30). However, in contrast, one series of

mesh procedures may include granulation tissue and 111 women treated for mesh complications with and

sinus tract formation. A detailed examination to rule without reoperation found that after at least 2 years, 29%

out underlying mesh or suture exposure should be per- reported the same or worse symptoms than those that

formed. A conservative approach, including observation occurred at presentation (31). Other series reported that

or chemical cautery of granulation tissue, may be tried. 50% of cases had persistent pain or dyspareunia after revi-

If a wound complication is persistent, referral to an sion surgery (26, 32). It should be noted that these data are

obstetrician–gynecologist with appropriate training and limited by study design and mixed outcome assessments.

Committee Opinion No. 694 5

There are risks to dissecting into the ischiorectal Mesh Erosion Into Viscera

fossa to access the sacrospinous ligament or adductor Erosion of mesh into organs, including the bladder,

compartment for access to the obturator membrane. rectum, or bowel, is a rare complication. A patient who

These include neurologic and vessel injury as well as experiences this type of erosion should be referred to a

significant blood loss. Likewise, coincident with the mesh specialist for management.

revision or removal surgery, the vaginal length or caliber

can be altered, contributing to dyspareunia and making Asymptomatic Patients Who Request

it difficult to differentiate the sequelae of the revision Removal of Mesh

procedure from those of the antecedent mesh procedure. Some asymptomatic women without any adverse effects

after mesh-augmented pelvic surgery may request mesh

Complications: Abdominally Placed removal. This request may come from a belief that the

Mesh (Sacrocolpopexy) mesh is harmful, has been recalled, or that their medi-

Vaginal Mesh Exposure colegal claim will be stronger if they have mesh removal

Like transvaginal mesh exposure, transabdominal mesh surgery. For women who are not symptomatic, there

exposure, if asymptomatic and due to a monofilament is no role for intervention. Indeed, the removal of the

mesh, may be managed conservatively with observa- mesh is more likely to cause adverse symptoms than to

tion and topical estrogen. If the patient is symptomatic, prevent future problems. Mesh removal surgery should

the exposure is persistent, or a multifilament mesh was not be performed unless there is a specific therapeutic

used, referral to a clinician with appropriate training and indication.

experience (such as a female pelvic medicine and recon- References

structive surgery specialist who is familiar with manag-

1. Nosseir SB, Kim YH, Lind LR, Winkler HA. Sacral osteo-

ing this complication) should be considered. Vaginal myelitis after robotically assisted laparoscopic sacral colpo-

mesh excision of visualized mesh can be performed. If pexy. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116 Suppl 2:513–5. [PubMed]

this approach fails, it is possible that a more complicated [Obstetrics & Gynecology]

revision or excision of the mesh using an abdominal or 2. Daneshgari F, Kong W, Swartz M. Complications of mid

laparoscopic approach may be necessary. urethral slings: important outcomes for future clinical tri-

als. J Urol 2008;180:1890–7. [PubMed]

Pain

3. Paine M, Harnsberger JR, Whiteside JL. Transrectal mesh

De novo vaginal apical pain has been reported after sacro- erosion remote from sacrocolpopexy: management and

colpopexy. This complication is uncommon but may comment. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;203:e11–3. [PubMed]

require complete excision of the mesh to relieve symp- [Full Text]

toms (33). A referral to a specialist should be considered. 4. Deffieux X, Thubert T, de Tayrac R, Fernandez H, Letouzey

Sacral Osteomyelitis or Discitis V. Long-term follow-up of persistent vaginal polypropyl-

ene mesh exposure for transvaginally placed mesh proce-

Osteomyelitis and discitis are serious and increasingly dures. Int Urogynecol J 2012;23:1387–90. [PubMed]

reported complications of sacrocolpopexy. They should

5. Abbott S, Unger CA, Evans JM, Jallad K, Mishra K, Karram

be considered in women who have back pain after this MM, et al. Evaluation and management of complications

procedure. At the time of surgery, the most prominent from synthetic mesh after pelvic reconstructive surgery:

landmark (often thought to be the sacral promon- a multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;210:163.

tory) is actually the L5-S1 disc, and ideal placement e1–8. [PubMed]

of sacral sutures to prevent discitis is caudad to this 6. American Urogynecologic Society, Society for Uro-

prominence. These infections can present remote from dynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital

surgery with significant morbidity and are diagnosed Reconstruction. Mesh midurethral slings for stress urinary

with imaging. Noncontrast magnetic resonance imaging incontinence. Position Statement. Silver Spring (MD):

is typically the most appropriate diagnostic approach. AUGS; Schaumburg (IL): SUFU; 2016. Available at:

A patient with this condition should be referred to an http://www.augs.org/index.php?mo=cm&op=ld&fid=814.

obstetrician–gynecologist with appropriate training and Retrieved December 12, 2016.

experience, such as a female pelvic medicine and recon- 7. Ferrante KL, Kim HY, Brubaker L, Wai CY, Norton PA,

structive surgery specialist. Often, a multidisciplinary Kraus SR, et al. Repeat post-op voiding trials: an incon-

venient correlate with success. Urinary Incontinence

approach, including working with specialists in orthope-

Treatment Network. Neurourol Urodyn 2014;33:1225–8.

dic surgery, neurosurgery, infectious disease, and female [PubMed] [Full Text]

pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery, is required to

8. Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, Colgan R, Geerlings

manage this complication. Conservative approaches may SE, Rice JC, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment

start with antibiotics; however, if there is an abscess, sur- of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults:

gical drainage; removing the graft; and possible debride- 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the

ment with reconstruction of the sacrum, lumbar vertebra, Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis

or disc spaces may be required. 2010;50:625–63. [PubMed]

6 Committee Opinion No. 694

9. Dieter AA, Amundsen CL, Edenfield AL, Kawasaki A, mesh excision for adverse outcomes after transvaginal

Levin PJ, Visco AG, et al. Oral antibiotics to prevent mesh placement using prolapse kits. Am J Obstet Gynecol

postoperative urinary tract infection: a randomized con- 2008;199:703.e1–7. [PubMed]

trolled trial[published erratum appears in Obstet Gynecol 25. Margulies RU, Lewicky-Gaupp C, Fenner DE, McGuire EJ,

2014;123:669]. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:96–103. [PubMed] Clemens JQ, Delancey JO. Complications requiring reop-

[Obstetrics & Gynecology] eration following vaginal mesh kit procedures for prolapse.

10. Rardin CR, Rosenblatt PL, Kohli N, Miklos JR, Heit M, Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;199:678.e1–4. [PubMed] [Full

Lucente VR. Release of tension-free vaginal tape for the Text]

treatment of refractory postoperative voiding dysfunction. 26. Blandon RE, Gebhart JB, Trabuco EC, Klingele CJ.

Obstet Gynecol 2002;100:898–902. [PubMed] Complications from vaginally placed mesh in pelvic recon-

11. Abraham N, Makovey I, King A, Goldman HB, Vasavada S. structive surgery. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct

The effect of time to release of an obstructing synthetic 2009;20:523–31. [PubMed]

mid-urethral sling on repeat surgery for stress urinary 27. Firoozi F, Ingber MS, Moore CK, Vasavada SP, Rackley RR,

incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 2015; DOI: 10.1002/ Goldman HB. Purely transvaginal/perineal management of

nau.22927. [PubMed] complications from commercial prolapse kits using a new

12. Whiteside JL, Hijaz A, Imrey PB, Barber MD, Paraiso MF, prostheses/grafts complication classification system. J Urol

Rackley RR, et al. Reliability and agreement of urodynam- 2012;187:1674–9. [PubMed]

ics interpretations in a female pelvic medicine center. 28. George A, Mattingly M, Woodman P, Hale D. Recurrence

Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:315–23. [PubMed] [Obstetrics & of prolapse after transvaginal mesh excision. Female Pelvic

Gynecology] Med Reconstr Surg 2013;19:202–5. [PubMed]

13. Richter HE, Albo ME, Zyczynski HM, Kenton K, Norton 29. Hurtado EA, Appell RA. Management of complications

PA, Sirls LT, et al. Retropubic versus transobturator midure- arising from transvaginal mesh kit procedures: a tertiary

thral slings for stress incontinence. Urinary Incontinence referral center’s experience. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor

Treatment Network. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2066–76. Dysfunct 2009;20:11–7. [PubMed]

[PubMed] [Full Text]

30. Tijdink MM, Vierhout ME, Heesakkers JP, Withagen MI.

14. Kobashi KC, Govier FE. Management of vaginal erosion Surgical management of mesh-related complications after

of polypropylene mesh slings. J Urol 2003;169:2242–3. prior pelvic floor reconstructive surgery with mesh. Int

[PubMed] Urogynecol J 2011;22:1395–404. [PubMed] [Full Text]

15. Jeppson PC, Sung VW. Autologous graft for treatment 31. Hansen BL, Dunn GE, Norton P, Hsu Y, Nygaard I. Long-

of midurethral sling exposure without mesh excision. term follow-up of treatment for synthetic mesh complica-

Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:437–9. [PubMed] [Obstetrics &

tions. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2014;20:126–30.

Gynecology]

[PubMed]

16. Al-Wadi K, Al-Badr A. Martius graft for the management

32. Crosby EC, Abernethy M, Berger MB, DeLancey JO,

of tension-free vaginal tape vaginal erosion. Obstet Gynecol

Fenner DE, Morgan DM. Symptom resolution after opera-

2009;114:489–91. [PubMed] [Obstetrics & Gynecology]

tive management of complications from transvaginal mesh.

17. Yoshizawa T, Yamaguchi K, Obinata D, Sato K, Mochida J, Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:134–9. [PubMed] [Obstetrics &

Takahashi S. Laparoscopic transvesical removal of ero- Gynecology]

sive mesh after transobturator tape procedure. Int J Urol

33. Buechel M, Tarr ME, Walters MD. Vaginal apical pain after

2011;18:861–3. [PubMed] [Full Text]

sacrocolpopexy in absence of vaginal mesh erosion: a case

18. Pikaart DP, Miklos JR, Moore RD. Laparoscopic removal series. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2016;22:e8–10.

of pubovaginal polypropylene tension-free tape slings. JSLS [PubMed]

2006;10:220–5. [PubMed] [Full Text]

19. Solomon ER, Jelovsek JE. Removing a misplaced retropu-

bic midurethral sling from the urethra and bladder neck

using ear, nose, and throat instruments. Obstet Gynecol Full-text document published concurrently in the April 2017 issue of

2015;125:58–61. [PubMed] [Obstetrics & Gynecology] Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery.

20. Wolter CE, Starkman JS, Scarpero HM, Dmochowski RR. Copyright April 2017 by the American College of Obstetricians and

Removal of transobturator midurethral sling for refractory Gynecologists. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may

thigh pain. Urology 2008;72:461.e1–3. [PubMed] be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, posted on the Internet,

or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

21. Pelvic organ prolapse. Practice Bulletin No. 176. American photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permis-

College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol sion from the publisher.

2017;129:e56–72.

Requests for authorization to make photocopies should be directed

22. Steege JF, Siedhoff MT. Chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol to Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA

2014;124:616–29. [PubMed] [Obstetrics & Gynecology] 01923, (978) 750-8400.

23. Marcus-Braun N, Bourret A, von Theobald P. Persistent ISSN 1074-861X

pelvic pain following transvaginal mesh surgery: a cause

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

for mesh removal. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2012; 409 12th Street, SW, PO Box 96920, Washington, DC 20090-6920

162:224–8. [PubMed]

Management of mesh and graft complications in gynecologic surgery.

24. Ridgeway B, Walters MD, Paraiso MF, Barber MD, Committee Opinion No. 694. American College of Obstetricians and

McAchran SE, Goldman HB, et al. Early experience with Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:e102–8.

Committee Opinion No. 694 7

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No163Dokumen15 halamanACOG Practice Bulletin No163Marco DiestraBelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Acne Treatment Strategies and TherapiesDokumen32 halamanAcne Treatment Strategies and TherapiesdokterasadBelum ada peringkat

- Acog 194Dokumen15 halamanAcog 194Marco DiestraBelum ada peringkat

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No093 PDFDokumen11 halamanACOG Practice Bulletin No093 PDFMarco DiestraBelum ada peringkat

- Acog Practice Bulletin PDFDokumen12 halamanAcog Practice Bulletin PDFVìctorQuesquen100% (1)

- Obstetric Care Consensus No2Dokumen14 halamanObstetric Care Consensus No2Marco DiestraBelum ada peringkat

- ACOG Diagnosis and Treatment 042315Dokumen14 halamanACOG Diagnosis and Treatment 042315Kristina MadjidBelum ada peringkat

- Obstetric Care Consensus 5Dokumen7 halamanObstetric Care Consensus 5Marco DiestraBelum ada peringkat

- Acog Practice Bulletin PDFDokumen12 halamanAcog Practice Bulletin PDFVìctorQuesquen100% (1)

- Corticoides para Maduracion Pulmonar ACOG 2017Dokumen8 halamanCorticoides para Maduracion Pulmonar ACOG 2017Renzo Cruz CaldasBelum ada peringkat

- Criteria For Admission: ABC of Intensive CareDokumen4 halamanCriteria For Admission: ABC of Intensive Caretuti utamaBelum ada peringkat

- Admission Critieria For ICUDokumen10 halamanAdmission Critieria For ICUMarco DiestraBelum ada peringkat

- Ancient Greek Divination by Birthmarks and MolesDokumen8 halamanAncient Greek Divination by Birthmarks and MolessheaniBelum ada peringkat

- On The Behavior of Gravitational Force at Small ScalesDokumen6 halamanOn The Behavior of Gravitational Force at Small ScalesMassimiliano VellaBelum ada peringkat

- Audit Acq Pay Cycle & InventoryDokumen39 halamanAudit Acq Pay Cycle & InventoryVianney Claire RabeBelum ada peringkat

- Udaan: Under The Guidance of Prof - Viswanathan Venkateswaran Submitted By, Benila PaulDokumen22 halamanUdaan: Under The Guidance of Prof - Viswanathan Venkateswaran Submitted By, Benila PaulBenila Paul100% (2)

- Case 5Dokumen1 halamanCase 5Czan ShakyaBelum ada peringkat

- Non Circumvention Non Disclosure Agreement (TERENCE) SGDokumen7 halamanNon Circumvention Non Disclosure Agreement (TERENCE) SGLin ChrisBelum ada peringkat

- DMDW Mod3@AzDOCUMENTS - inDokumen56 halamanDMDW Mod3@AzDOCUMENTS - inRakesh JainBelum ada peringkat

- Books of AccountsDokumen18 halamanBooks of AccountsFrances Marie TemporalBelum ada peringkat

- Maj. Terry McBurney IndictedDokumen8 halamanMaj. Terry McBurney IndictedUSA TODAY NetworkBelum ada peringkat

- Portfolio Artifact Entry Form - Ostp Standard 3Dokumen1 halamanPortfolio Artifact Entry Form - Ostp Standard 3api-253007574Belum ada peringkat

- Artist Biography: Igor Stravinsky Was One of Music's Truly Epochal Innovators No Other Composer of TheDokumen2 halamanArtist Biography: Igor Stravinsky Was One of Music's Truly Epochal Innovators No Other Composer of TheUy YuiBelum ada peringkat

- Column Array Loudspeaker: Product HighlightsDokumen2 halamanColumn Array Loudspeaker: Product HighlightsTricolor GameplayBelum ada peringkat

- Level 3 Repair PBA Parts LayoutDokumen32 halamanLevel 3 Repair PBA Parts LayoutabivecueBelum ada peringkat

- ITU SURVEY ON RADIO SPECTRUM MANAGEMENT 17 01 07 Final PDFDokumen280 halamanITU SURVEY ON RADIO SPECTRUM MANAGEMENT 17 01 07 Final PDFMohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- House Rules For Jforce: Penalties (First Offence/Minor Offense) Penalties (First Offence/Major Offence)Dokumen4 halamanHouse Rules For Jforce: Penalties (First Offence/Minor Offense) Penalties (First Offence/Major Offence)Raphael Eyitayor TyBelum ada peringkat

- CR Vs MarubeniDokumen15 halamanCR Vs MarubeniSudan TambiacBelum ada peringkat

- Wi FiDokumen22 halamanWi FiDaljeet Singh MottonBelum ada peringkat

- Math5 Q4 Mod10 DescribingAndComparingPropertiesOfRegularAndIrregularPolygons v1Dokumen19 halamanMath5 Q4 Mod10 DescribingAndComparingPropertiesOfRegularAndIrregularPolygons v1ronaldBelum ada peringkat

- Towards A Human Resource Development Ontology Combining Competence Management and Technology-Enhanced Workplace LearningDokumen21 halamanTowards A Human Resource Development Ontology Combining Competence Management and Technology-Enhanced Workplace LearningTommy SiddiqBelum ada peringkat

- QuickTransit SSLI Release Notes 1.1Dokumen12 halamanQuickTransit SSLI Release Notes 1.1subhrajitm47Belum ada peringkat

- IDokumen2 halamanIsometoiajeBelum ada peringkat

- 1.each of The Solids Shown in The Diagram Has The Same MassDokumen12 halaman1.each of The Solids Shown in The Diagram Has The Same MassrehanBelum ada peringkat

- Customer Perceptions of Service: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinDokumen27 halamanCustomer Perceptions of Service: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinKoshiha LalBelum ada peringkat

- BIBLIO Eric SwyngedowDokumen34 halamanBIBLIO Eric Swyngedowadriank1975291Belum ada peringkat

- Steam Turbine Theory and Practice by Kearton PDF 35Dokumen4 halamanSteam Turbine Theory and Practice by Kearton PDF 35KKDhBelum ada peringkat

- Innovation Through Passion: Waterjet Cutting SystemsDokumen7 halamanInnovation Through Passion: Waterjet Cutting SystemsRomly MechBelum ada peringkat

- GMWIN SoftwareDokumen1 halamanGMWIN SoftwareĐào Đình NamBelum ada peringkat

- Mercedes BenzDokumen56 halamanMercedes BenzRoland Joldis100% (1)

- 15142800Dokumen16 halaman15142800Sanjeev PradhanBelum ada peringkat