The Politics of Ritual Secrecy

Diunggah oleh

thalassophiliaDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

The Politics of Ritual Secrecy

Diunggah oleh

thalassophiliaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.

ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

The Politics of Ritual Secrecy

Author(s): Abner Cohen

Source: Man, New Series, Vol. 6, No. 3 (Sep., 1971), pp. 427-448

Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2799030 .

Accessed: 19/09/2013 01:14

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve

and extend access to Man.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

THE POLITICS OF RITUAL SECRECY

ABNER COHEN

SchoolofOriental

andAfrican

Sttudies,

University

ofLondon

Thereare about six millionmen in theworldtodaywho are themembersof

whathas been describedas thelargestsecretsocietyon earth-Freemasonry. The

overwhelming majorityof thesemenlive in thehighlyindustrialised societiesof

westernEurope and Americaand almostall are membersof the wealthyand

professionalclasses.

In Britainalone thereare about three-quarters of a millionFreemasons(see

Dewar I966: 46-7). They are organisedwithinlocal lodges whichare ritually,

ideologicallyand bureaucratically supervisedby the grandlodges of England,

Scotlandand Ireland.Theymeetperiodically in theirlocal centresand,behindthe

locked and well-guardeddoors of theirtemples,theywear theircolourfuland

elaboratelyembroidered regalia,carrythejewels, swordsand otheremblemsof

office,

andperform their'ancient'secretrituals.

The bulkoftheseritualsis concernedwiththeinitiation ofnew membersor the

promotionof existingmembersto higherdegrees.Theseritesof passageinvolve

theenactment of lengthydramas,in thecourseof whichcandidatesgo through

phasesof deathand rebirth, are entrusted withnew secretsigns,passwordsand

hand-clasps, and are made to takeoaths,underthethreatofhorrifying sanctions,

notto betraythesesecretsto outsiders. Recurringwithintheseritesofpassageare

episodesfromthelifeand careerof a mythological hero,HiramAbiff, who is said

to have designedtheTemple of Solomon.In theface of continualcriticism and

oppositionfromtheChurch,Freemasonsgo out of theirway to emphasisetheir

faithin the SupremeBeing,to whom theyreferas 'The GreatArchitect of the

Universe'or, at times,'The GrandGeometrician', and prominently displaythe

Holy Book' in all theirmeetings.

Thereis a vastliterature on Freemasonry. A largepartof it is concernedwith

controversies about the originsof the cult or the sourcesof its mythologyand

rituals.The longessayin theEncyclopedia Britannicais purelyhistorical.Another

sectionof this literatureconsistsof attacks,particularly by Roman Catholic

clergymen, againstthemovement,or of apologeticreactionsby Masons against

theseattacks.A thirdsectionconsistsof speculationsor disclosuresabout the

secretritualsof thecraft.

Althougha greatdeal is now knownaboutitshistoryand rituals,verylittleis

known about its social significance, or its involvementin the systemof the

distributionand exerciseof power in our society.Our ignoranceis only partly

due to thesecrecyin whichthe movementis enveloped.Freemasonsrepeatedly

pointout thattheyarenota secretsocietybuta societywithsecretrituals.By this

theymeanthatit is onlytheirritualsthatare secret,but thatmembership is not

secret.But theanomaloussituationtodayis thatwhiletheseritualsare no longer

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

428 ABNER COHEN

secret,hardlyanythingis known about membership.Legally,everylodge is

obligedby law to submita listofitsmembersto thelocal Clerkof thePeace. But

neitherclerksofthepeace,northeMasonic- authoritiesareobligedto makepublic

thefulllistof members(seeDewar I967: 103-4). Some scantybitsofinformation

appearin thenewspapers everynow and thenaboutindividualMasonsand some

Masonsmay also in one way or anotherrevealto friends theirmembership, but

on thewhole themajoritydo not go out of theirway to maketheirmembership

known.

A greatdeal ofthisreluctance to disclosemembership is probablytheresult,not

of theteachingsof Freemasonry as such,but of thegeneraltendencyof members

of the middleand upperclasses,fromwhichMasonsare recruited, to be highly

individualistic and to value privacyin theirlives.This is indeedone of themain

reasonswhyso littlesociologicalresearch in generalhasbeencarriedoutin Britain

amongtheseclasses.

Added to thisdifficulty is theimmensity of thescaleof our socialgroupsand

settlements, withtheresultthatamidstour massiveand highlyimpersonalurban

milieux,it is too difficult

to identify and locatemembersor to be acquaintedwith

theircirclesor to know muchabouttheireconomic,politicalor othersocialroles.

Finally,it mustbe remembered thatsociologists are oftenso immersedin the

verycultureof whichFreemasonry is a part,thatsome of themarehardlyaware

evenofitsexistenceor of thesignificance of itsinformal symbolism.

Some of theseepistemological and methodological difficulties

can be overcome

if Freemasonry is studiedas it is practisedin a totallydifferent socialand cultural

contextfromthatof our own,withinrelatively small-scalesocieties.I believethat

we canlearna greatdealaboutour own culturegenerally whenwe studyitsforms

in foreignlands.Most anthropologists workingin preindustrial societieshave so

far,fora varietyofreasons,shiedawayfrominvestigating thefunctions ofWestern

culturalformsin thesesocieties.

Even a casuallook throughthepages of theyearbooks of theMasonicgrand

lodgeswill be sufficient to show thatrelatively largenumbersof Masoniclodges

existin nearlyall thenew statesof Africaand Asia. (Thereare 44 in Nigeria,43

in Ghana,and well over ioo in India,to takeonlyrandomexamples.)Thereis

practicallynothingwhateverknownaboutthesocialsignificance of theseMasonic

lodges.

I shalldiscussherethe organisation and functioning of Freemasonry in Sierra

Leone, west Africa.The interplaybetweenindividualmotivesand structural

constraints in thelocal development and functioning of thiscultwill be analysed.

In conclusionsome observations aboutthesocialsignificance and politicalpoten-

of Freemasonry

tialities withinindustrial societieswill be made.

The Creoles

Thereare todayseventeen Masoniclodgesin SierraLeone,all in Freetown,the

capital.Sevenof thesefollowtheEnglishConstitutionof Freemasonry. They are

organisedundera DistrictGrandLodge andareultimatelysupervised bytheGrand

Lodge ofEngland.The remaining tenlodgesfollowtheScottishConstitution of

Freemasonry, are organisedunder a separateDistrictGrand Lodge, and are

ultimately supervisedby the GrandLodge of Scotland(see table i). There are

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

THE POLITICS OF RITUAL SECRECY 429

no MasonicLodgesin SierraLeone whichfollowthethird'sister'Constitution of

Ireland.

I estimatethatthereareabout2,000 membersin theselodges.Only a handfulof

theseareEuropeans,mainlyBritish,althoughit was originally Britishofficials

in

thecolonialadministration who established Freemasonry in SierraLeone.2Most

oftheseEuropeansaretodayconcentrated in one particularlodge,alongwithother

Africans. SomeoftheBritishmembers havebeeninthemovement inBritainbefore

goingto SierraLeone and wantto continuetheirmembership throughaffiliation

withina Freetownlodge. A fewhavejoined in SierraLeone mainlyin orderto

become part of the movementin Britainwhen theyreturnhome. These find

joiningmucheasierin SierraLeone thanin Britain.My impression is thaton the

wholetheseEuropeanMasonsplayno significant rolein theactivities of thelocal

lodgesatpresent andatleastsomeofthemseemto be lukewarmin theirattendance

at theregularmeetings ofthemovement.

The bulkof theMasonsin Freetownare thusAfricans, and theGrandMasters

and theotherimportant office-bearers in bothdistrict grandlodgesareAfrican.

Withveryfewindividualexceptions, all theAfricans in theMasoniclodgesare

Creoles,the descendantsof the slaves who were emancipatedby the British

betweenthe I780's and the I85o's, and were duly settledin the 'Provinceof

Freedom',theFreetownPeninsula,whichwas boughtforthepurposefromthe

local Temne chiefs(see FyfeI962; PorterI963; PetersonI969). The Creolesare

predominantly highlyeducated,and occupationally

literate, differentiated.They

numbertoday41,783 in the whole of SierraLeone, with 37,560 of themcon-

centrated in the FreetownPeninsula,and 27,730 in the cityof Freetownitself.

The remaining4,223 are scatteredamong the provincialtownsand are mostly

civilservants and teacherswhose homesare in Freetown.(For censusdetails,see

CentralStatisticsOffice,I965.) The Creoles are thus essentially metropolitan.

AlthoughtheycompriseonlyI9 percent.of thetotalpopulation,theydominate

thecivil service,thejudiciaryand theothermajorprofessions of medicine,law,

engineering, university and highschoolteaching.A relatively substantialnumber

ofthemhavecompleteduniversity training in Britainor in theU.S.A.

Fromtheverybeginningoftheirsettlement in SierraLeone,theCreolesmadea

bid to havea new startin theirculturallife.TheyadoptedEnglishnames,English

stylesof dress,education,religion,etiquette, art,music,and a generalEnglishstyle

oflife.Even todaytheycantrulybe saidto be in manywaysmoreEnglishthanthe

English.I have indeedheardCreole men who have visited'swingingBritain'

recently expresspersonalshockand disillusionment at thedeparture oftheEnglish

fromtheir'proper' tradition which,in theCreoleideology,is synonymous with

civilisationand enlightenment. It is ccrtainly no exaggeration thathasled themso

oftento be called 'The Black Englishmen'.

Aftera period of interaction with the Creoles on the basis of equalityand

comradeship, theBritishadministrators turnedtheirbackson themand beganto

resenttheirattempts to be equal partners in Britishcivilisationand in thesharing

of politicalpower with them.The Britishadministrators graduallysegregated

themselves fromCreole companyand Britishwritersand travellers pouredscorn

and ridiculedtheir'rubbishy'Whitecultureand their'aping' ofEnglishcustoms

and waysoflife.But,as Banton(I957: 96-I20) pointsout,theircultureis veryfar

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

430 ABNER COHEN

frombeingmerelytheblindresultof any superficial apingof Englishways. On

the contrary, it represents a unique and highlysophisticated culturecombining

different traits,bothEnglishandnon-English, in a new way. Anyonewho hashad

close personalcontactswith the Creoleswould know thattheirstyleof lifeis

genuineand naturaland is deeplyrootedin theirpersonality structure and en-

trenchedin theirthinking and in theirway of life.It is a culturewell worthin-

vestigating in itsown right.

Althoughtheyoriginally hailedfromdifferent partsof westAfrica(principally

fromNigeria)and carrieddifferent culturaltraditions, theCreolesmanagedin the

courseofonlya fewdecadesto developa homogeneouscultureoftheirown andto

set themselvessharplyapart,both culturallyand socially,fromthe restof the

populationof SierraLeone,to whomtheyreferred derisively as the'Aboriginies'.

(Fora detailedaccount,seePetersonI969). Duringthesecondhalfofthenineteenth

century and theearlydecadesofthepresentcentury theyattempted to controlthe

Natives,3but theBritishcolonialadministration, fora varietyof considerations,

thwarted thatattempt (seeFyfeI962: 614-20). If it hadnotbeenforthisBritish

policy,theCreoleswouldhaveprobablysucceededin achievingthesamedegreeof

overall dominationthat has been accomplishedby the Americo-Liberians, a

similarminority witha similarorigin,inneighbouring Liberia(seeLibenowI969).

Until about the end of the firstworld war, the Creoleswere prominentin

business.But sincethena numberof factorshaveled to therapiddeclineof their

businesses andto thetransfer oftheirresourcesandoftheirenergies intothetraining

and recruitment of civil servantsand professionals (see PorterI963). Extensive

biographicalevidenceshowshow one successful businessman afteranotherspent

his fortune, not on the developmentof his business,but on givinghis children

highereducationin Britainor America.Almostinvariably thesucceedinggenera-

tionpreferred thehighlylucrative,stable,and sociallyesteemedpositionsof the

professions and government service,so Creole businessvirtuallydied out, to be

takenoverby Lebanese,British,and Indianbusinessfirmswho are stilldominant

today.

Creolepowertodaystemsfromtwo majorresources.The firstis theextensive

propertyin land and in housingin Freetownand in the restof theFreetown

Peninsulawhichtheycontrol.Thisproperty has greatlyappreciated in valuesince

the end of the secondworld war, more particularly so sinceindependence, be-

causeof an increasing demandby foreigndiplomaticmissions,by wealthySierra

Leoneansfromtheinterior of thecountry, and by therapidlyexpandinggovern-

mentadministration. This propertyis freehold,while all the land in the other

provincesof thecountry, in whatwas formerly referred to as theProtectorate,is

still'tribal' land which cannotbe sold. Their secondsourceof power is their

predominance in thecivilserviceand in theprofessions.

Both thesestrongholds are now beingseriously challengedby thetribesmen of

theprovinces, particularly by theMende(30.9 percent.of thepopulation)and the

Temne (29-8 per cent.of thepopulation;see CentralStatistical OfficeI965). By

theirsheervotingpower,thesenon-CreoleSierraLeoneanscompletelydominate

theexecutiveandthelegislature andtheirpoliticians havebeenfrequently harassing

theCreolesand denouncing themas foreigners.The Temnemaintainthatthevery

landon whichtheCreoleshavedevelopedtheirsocietyand culture,theFreetown

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

THE POLITICS OF RITUAL SECRECY 43I

Peninsula,is theirsand thattheirforefathers were trickedintosellingit to the

Britishfora trivialpriceforthepurposeof settlingthe Creoles(see FyfeI964:

II2-I3). It is significant

thatevennow, theCreolesare stilllegallyreferred to as

'Non-Native'. And, as rapidlyincreasingnumbersof 'Natives' are becoming

educatedand trained,Creole predominancein the civil serviceand in thepro-

fessions is becomingincreasingly moreprecarious.

The cleavagebetweentheCreolesand theNativeshas dominatedSierraLeone

politicsthroughout thiscentury.This cleavageis symbolically representedin the

very flag of the state.The committeewhich designedthe flag chose blue to

represent 'thosewho camefromacrosstheseas',namelytheCreoles,greenforthe

nativeinhabitants, and white,signifying peace-or rather,thewish forpeace-

separatingthem.But the cleavageis becomingdeeper,thoughits processesare

operatingbehindnew slogansand new identities. Many Creolestodayclaimthat

theyarefacingnotjust thethreatof losingtheirpropertyand theirpositions, but

virtualphysicalannihilation and theyquote in supportof thisclaimvariouspro-

nouncements by politiciansand others,particularly

in theprovinces.

From thefiguresquoted earlier,it shouldbe evidentthatnearlyone in every

threeCreolemenin Freetownis a Mason. CreoleMasonsdo nothidethefactthat

Masonryin SierraLeone is overwhelmingly Creole.But theyargueat lengththat

thisis not theresultof anykindof policyof exclusion.They invariablymention

some namesof non-CreoleSierraLeoneanswho are Masons.The name of one

man in particular was mentionedto me over and overagainby different Creole

Masons.A Creole Mason will eagerlytellyou thatthereare manynon-Creole

SierraLeoneansin themovement.But whenyou askspecifically whetherthereare

suchmembersin hisown lodge,theanswerwilloftenbe that:'It so happensthat

thereis no one in ourown lodge,buttherearemanyin theotherlodges'. Thereis

no doubtthattherearea fewNativesin thelodgesbuttheirnumberis insignificant

and fora varietyofreasonswhichwillbecomeclearlatertheirmembership is only

nominal.It is a factthatall the importantfiguresin the Masonic movement,

includingthe two GrandDistrictMasters,are Creole. No nativename is ever

mentioned inthenewspapers in connexionwithFreemasonry andall theannounce-

mentsoffunerals and obituaries of deceasedMasonswhichI have beenable to see

or hearincludeno Natives.

I do not myselfthinkthatthereis any consciouslyformulated policy of ex-

cludingnon-CreoleSierraLeoneansfrommembership. Many Masonsthinkthat

non-Creolesare rarein the movementeitherbecausetheyare not interested, or

becausetheyare Muslims,or becausetheycannotaffordthe expense,or simply

thattheyare not sufficiently educated.Many Creoleswould also add thatthe

Natives have theirown secretsociety,the 'Poro', to which they are always

afflliated.The Nativesdo not in factneed to become membersin the Masonic

movement.More thanthat,whilethereis a good deal ofpressure on Creole men

tojoin themovement,thereis a good deal ofpressureon Nativesnottojoin it.4

Theincidenceofmembership

As witheveryothercult,individualMasonsmentiona wide varietyof motives

forjoining the movementand remainingwithinit. Some join because they

personallywant to, but othersjoin becauseof pressure.Oftena man mayjoin

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

432 ABNER COHEN

initiallyfor one motive,but develop othersafterjoining. The same nlan may

emphasisedifferent motivesfor being a Mason at different times.A man who

joined as a resultofpressure maydevelopmotivesor sentiments thatareindividual

and personal.Ifwe considerthesentiments, motives,andcircumstances ofeachin-

dividualmembership, we willfindthateachis a uniquecaseand,whenquestioned,

Masonsoftenoffer consciousand rationalconsiderations fortheirmembership.

This,of course,is onlyone side of thestoryand it will failby itselfto tellus

anythingabout Freemasonry as an institution in its own rightor about the

structural circumstances whichkeep it alive as a going concern.The structural

consequences ofFreemasonic activity

arecertainly largelyunintended byindividual

Masons,as eachindividual'sfirstconcernis hisown interests. Thereis thusa dia-

lecticalrelationbetweentheindividualand thegroup.In otherwords,although

individualmembersseemto be actingfreelyand rationally, theiractionis never-

thelessconditioned largelyunconsciously bystructural factorswhichto someextent

constrain a manto behavein certainways.Thus,thecollectiveand theindividual

arecloselyrelated,thoughforanalytical purposestheyshouldbe keptapartifwe

are to understand thesocialsignificance of themovement.I wantto avoid at this

stage discussingthisproblemin the abstractand will thusproceedto consider

briefly themultiplicity and collmplexity of factorsunderlying membership.

Like many other ritualsystems,Freemasonry offersa body of beliefsand

practiceswhichhave intrinsic value.It providesa worldview whichincludesthe

place of manin theuniverse.The literature of speculativeFreemasonry containsa

largenumberof treatises on metaphysics and theologywrittenby men who are

passionatein theirsearchforwhattheybelieveto be thetruth.In FreetownI met

youngMasonswho spenta good dealoftheirsparetimereadingMasonicliterature

forsheerintellectual satisfaction.

Some menjoin the movementin the beliefthatthe secretswhichtheywill

acquirecontainvitalintellectual and mystical formulae.Thisbeliefis sustained for

long after joining as moreand moresecretsand ritualsareunfoldedto theMason

whenhe passesto higherdegreeswithintheorder.

Many of the Masons in Freetownwith whom I talkedstressedthe personal

satisfaction whichtheyderivedfromthe regular,frequentand extensiverituals

and ceremonies of thelodge. Some of theseMasonssaid,in explanation, thatafter

all theywere Africansand thusfondof the typeof dramathatthe movement

provided.A particularly powerfulsentiment in thisrespectis Freemnasonic cere-

monialconnectedwiththe deathof a 'brother'.The Creolesare intensely con-

cernedwithdeath,andfunerals aregreatpublicevents,oftenattendedbythousands

ofpeople,dependingonthestatusofthedeceased.Deathsandfunerals areregularly

announcedon thenationalradioin specialbulletins, and oftenthelodge or lodges

connectedwitha deceasedmanaresummonedto thefuneral bya specialannounce-

menton theradio.LodgesundertheEnglishMasonicconstitution areprohibited

by specialrulesoftheGrandLodge of Englandfromgoingoutin regaliato attend

a publicfuneral,althoughtheyare allowed by specialpermissionto appearin

regaliawithinthechurchforthefuneralserviceof a brother.But thisprohibition

does not existwithinthe Scottishconstitution to which the greaternumberof

Freetownlodgesbelong.ManyofthemembersofEnglishlodgesarehoweveralso

affiliatedwithinScottishlodges,so thattheirfunerals are oftenattendedformally

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

THE POLITICS OF RITUAL SECRECY 433

bytheirlodgesofaffiliation, inregalia.Thedeceased manis'laidout'inhisformal

blacksuit,withhisfullMasonicregaliadecorating him,forhoursbeforethe

funeralserviceandlargenumbers ofpeoplefilepast.Whenthecoffin is finally

covered, theregaliais takenoffthebodyandplacedon top.Masonsunderthe

Scottishconstitution proceedin theirregaliato theburialgroundandwhenthe

Christianburialservice is over,theMasonsperform a specialservice at thegrave

tosendtheirdeceased brother offtothe'Highest Lodge'.Itisindeedthedreamof

manyCreolemenwithwhomI talkedtobe buriedwithallthepompandcolour

oftheMasonicceremonial, andI haveno doubtthatthisisanimportant sourceof

satisfaction

formembers ofthemovement. Someoftheobituaries in thenews-

papersalsocarry photographs ofthedeceased intheirMasonicregalia.

A secondbodyofintrinsic valuesthatmenfindinFreemasonry isthe'system of

morality' thatit offers.A greatdealof theorganisation andceremonial of the

movement isconcerned withthedevelopment andmaintenance ofa truebrother-

hoodamongitsmembers. Members areaskedspecifically to 'fraternise' withone

another,anda gooddealofthetimeandresources ofthelodgesis devotedtothis

end.Theregular ritualsessionsofthelodgearefollowed byinstitutionalised, lavish

banqueting anddrinking. TheCreolesgenerally drinkheavily andmanycynics in

Freetown saythatmentaketo Masonry primarily for;'boozing'.The lodgeis

indeedverymuchan exclusive club.

Oneimportant aspectofFreemasonry asa brotherhood istheelaborate organisa-

tionofmutual helpwhichit develops, andthereisno doubtthatthewelfare and

socialsecurity benefits thatit offersattract someto themovement. Freemason

welfareservices inBritain areindeedamongthemostlavishandefficient. Manyof

theirbenevolent institutionsarepatronised bymembers oftheRoyalFamily.In

theUnitedStatesthisaspectofthemovement is evenmorepronounced. In Free-

town,noformal benevolent institutions

havebeenestablished yet.Suchinstitutions

taketimeto developandnearly allMasonshavea network ofkinwhoareunder

customary obligations to helpin thehourofneed.Nevertheless, thelodgeshave

provided helpin manyinstances andtheircareforagedmembers is particularly

pronounced. Everylodgehasanalmoner whoattends tocasesofneedandhasfor

thepurpose a specialwelfare fundtowhicheachmember contributes regularly at

a fixedrate.Thus,although a Creolemayexpecthelpinthetimeofneedfromhis

kin,hemaystill joininordertosecure forhimself andforhisfamily anadditional

measure ofsupport or securitywithout theburdenof kin obligations.

SomeMasonsmentioned alsotheimportance ofcontacting brothers inforeign

lands.The Creolestravelveryfrequently to Britain the

and U.S.A. in the course

of theireducational and professional in

careersand theysee Freemasonry an

organisation thatenablesthemtofindhelping andwelcoming brothers wherever

theygo. Thesebrothers abroadtendto be at thesametimepeopleofmeansand

influenceandtheirhelpcanbe substantial. I meta youngCreoleon hiswayto

Britainforthefirst timetostudy whotoldmethathewasa member ofa Scottish

lodgebutthatshortly before heleftheaffiliated himselfwithin oneoftheEnglish

Lodgesin orderto be abletomakecontacts withbrothers in bothEnglandand

Scotland.

Freemasons are required by specialrulesto harbourno enmity againstone

another andtosettle anymisunderstanding ortension between brothers promptly

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

434 ABNER COHEN

andamicably.Thismustbe particularly significantformanyCreoleMasonswho,

in ordinary secularlife,arecaughtby thetensions ofcompetition forappointments

and promotionsand by the estrangement resulting from involvement in the

hierarchical bureaucratic structuresof thecivilserviceor theprofessions.

One of the moralprinciplesof the Freemasonicbrotherhood whichis parti-

cularlystressedby Creole Masons in Freetownis thatno brothershouldflirt

or commitadulterywith the wife of anotherbrother.This 'private' piece of

morality is one ofthemechanisms meantto reducepotentialsourcesoftensionand

enmitybetweenmembers, and is widelyusedin theorganisation ofmanykindsof

fraternities.

Womenareseenin manycontexts as a sourceof tensionbetweenmen.

This is probablythe mainreasonwhy Freemasonry and othersecretsocietiesof

this kind are exclusivelymale organisations. Indeed one of the indirectconse-

quencesof Freemnasonic membership among the Creoles is thatit servesas a

mechanisminstitutionalising the weaningof men fromtheirwives. Wives and

femalerelativesare invitedonlyonce a yearto a Ladies' Nightwhicheachlodge

holds.Even ifa manbelongsto onlyone lodge,he can spendtwo or threenights

a week in ceremonialsessions,meetingsof committees, or visitingotherlodges,

awayfromhiswife.A substantial proportionofthemembersof a lodge areOffice

Bearersand theirvarious dutiesnecessitate frequentmeetings.And, as many

in

Creoles Freetownare not onlymembers one lodgebutareaffliated

in to one or

more otherlodges,theirabsencefromtheirwives is indeedfrequentand pro-

longed.MostMasonicmeetings in Freetownstartat about6-30p.m. and go on in

ceremonialand in banquetinguntilabout 2 a.m. While oftensharingwiththeir

husbands someofthebenefits ofFreemasonry, wivesareannoyedbyit.Manywives

thinkthattheirhusbandsuse lodge meetingsas an alibiforvisitingotherwomen.

The CreolesaredevoutChristians andpridethemselves on beingmonogamous.

Also, Creole marriageis governedby Britishlaw, so thatwhile a Mende or a

Temnecan marryaccordingto customary law morethanone wife,a Creoleman

wouldbe prosecuted forbigamyifhe marriedanotherwife.But itis an established

'customary'institution thatmost Creole men take 'outside women', support

them,andhavechildren bythem.One ofthepeculiarities ofthedemography ofthe

Creolesis thatwithinthe age group of twenty-five to forty-five,women sub-

stantiallyoutnumbermen. The effectof this numericalimbalancebetween

thesexesis aggravatedby thefactthatmen marrylate.As thereis a verystrong

pressureon Creolesto marryCreoles,theresultis thatthereare manymoreun-

marriedwomenthanmen,and hencetheinstitution of the'outsidewoman'. The

wealthierand themoreeminenta man is themoreoutsidewiveshe has. This is

trueevenof eminentclergymen withintheChurchhierarchy, and is certainlyan

integralpartofCreoleculture(seeFashole-LukeI968). Itsfunctioning hasrequired

a good deal of' distance'or avoidancebetweenmanand wifeandfrommyobser-

vationI can say thatFreemasonry servesindirectly as a mechanismforbringing

aboutthisavoidance.

Apart fromtheseritualand moral values,some individualCreoles find in

Freemasonry more 'practical'and mundaneadvantages.Non-Mason cynicsin

Freetownclaim thatmen join in orderto establishinformallinkswith their

superiorsin the civil serviceor the professions, as the case may be. It mustbe

remembered thatmanyof the mosteminentjudges, lawyers,permanentsecre-

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

THE POLITICS OF RITUAL SECRECY 435

taries,headsof departments, doctors, engineers and othersaremembers of the

Masoniclodgesin Freetown. In a society whererankand patronage countfora

greatdeal,thismustindeedbe an important factorattracting mentojoin. One

oftenhearsgossipin Freetown societyto theeffect thatall appointments and

promotions in certain establishments are'cooked'in thelodges.Similarcharges

havealsobeenmadeagainst Freemasonry inBritain, America andelsewhere. But

oneneednotassumethevalidity ofthesecharges in orderto appreciate thefact

thatmenshouldseekto establish primary relationswiththeirsuperiors, irres-

pective ofpossible material gain.ManyoftheMasonsareinvolved inbureaucratic

hierarchies, as superiors andsubordinates, outside themovement, anda greatdeal

oftension arises between themin varioussituations. It is natural thattheyshould

welcomean institution whichalleviates theeffects of thistension.

Association withthe'high-ups' through Masonry leadsmanynon-Masons in

Freetown to complain thatMasonsaresnobsandbehavein a superior manner.

Masonryis certainly synonymous withhighclassin Freetown forthesimple

reasonthata mancannotbecomea Masonifhe cannotafford to paythehigh

expenses ofmembership andoftheveryfrequent andlavishbanqueting. Theannual

costofmembership foraninitiate intotheEntered Apprentice degree isabout ?50o,

excluding thecostofa blacksuit,transport, andso on.Atpromotion to a second

degreethecostwillbe higher. Whenheiseventually 'raised'totheThirddegree,

thatofa Master Mason,thecostduring theyearwhenheis'reigning ' inthelodge

is between?4?? and ?5soo.Although bothkinandlodgebrothers contribute

towards thisexpense, thebulkofthecostwillbe bornebythemanhimself The

regular payments thatmembers makeannually includefeesforregistration, con-

tribution to benevolent funds, andsomeotherminoritems.The regaliaforthe

initiate costsover/25 andas theMasonrisesin degrees so doesthecostofhis

regalia. MostofthelodgesinFreetown include thebasiccostofbanqueting forthe

wholeyearintheirannualfees,so thatwhether a manattended a banquetornot

he wouldhavepaidthecosts.Quiteapartfromtheexpenses ofmembership, a

manmustalsohavetheright connexions ifhewantstojointheorder.Freemasons

do notproselytise andcandidates arenearly alwaysintroduced bykinandfriends

whoarealready members. Thereisaninitial periodofinvestigation bya Committee

ofMembership duringwhich inquiriesaremadeaboutthecandidate, andthecandi-

datehimself is interviewed and questioned at length. WhentheCommittee is

satisfied, thecandidate is proposed forelection ina general meeting ofthelodge.

Election isbysecret balloting. Ifmorethanoneblack-ball werecastthecandidate

wouldnotbe admitted. Thismeans thatonly'theright people',whoareacceptable

tonearly thewholelodgewillbeadmitted. Membership isthustakenasa privilege

andMasonsareto a greatextent proudofit.

Perhaps largely unconsciously, theCreolesgenerally seein Masonry a mechan-

ism forthe development and maintenance of a 'mystique'whichmarksand

enhances theirdistinctiveness and superiority vis-a-vis theNatives.Thisis be-

comingincreasingly necessary inrecent yearsasnativeSierra Leoneans, backedby

thepolitical poweroftheir sheernumbers, whichtheyhaveenjoyed sincetheearly

I950'S, arechallenging theCreolesontheir owngrounds ofclaimstosuperiority-

education. One mythwhichyouhearoverandoveragainin conversation with

Creoles isthatnomatter howhighly educated a Nativemaybe,hewillneverhave

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

436 ABNER COHEN

the same kind of 'mentality','civilisation',or culturalsophistication as the

Creoles.Theseelitequalities,theCreolesmaintain, aretheoutcomeofcenturies of

'civilisation'and can neverbe achievedby moneyor by formaleducation.There

are varioussymbolicmechanisms forthedevelopmentof this'mystique'among

the Creoles,and Freemasonry, throughits associationwithWesterncivilisation,

is seen as the hall-markof superiority,in contrastto the 'bush' secretsocieties

of the Mende, the Temne, and others.For the Creoles,Freemasonry is in this

respectan organisation withinwhich theyshareritualand moral values with

eminentEuropeanson the bases of equalityand 'brotherhood'.Freemasonry

requiresa good deal of literacyand educationand of sophistication in dressand

etiquette.Freemasonry probablyservesthe same kind of need in Britainand

Americaforthedevelopment of a mystiqueof superiority

whichis creatednotso

muchto convinceothersas to convincetheactorsthemselves.

Structural constraints

But by farthe mostimportantfactordrivingCreole men to Freemasonry is

pressurefromkin,fromfriends, and fromwidergroupings.Indeedmanyof the

benefits thatindividualMasonsaresaidto gainfrommembership areelaborations

or rationalisations

developedafterjoining. A greatdealofinsight intothestructural

forcesthatconstrain Creolementojoin Freemasonry can be gainedfromtalking

to menwho arenotyetMasons.

Some menjoinbecausetheirfathers areor wereMasons.A Masonregardsitas a

dutyand a sourceof prideto bringhis sonsinto membership, oftenwithinthe

samelodge.As sonsreachtheage of twenty-one theirfathers beginto pressthem

to join. I know of at leastone case wherea man who is eminentin both Free-

masonryand in the politicalorganisation of the statein SierraLeone, took the

troubleto ask the higherMasonic authorities in Britainfor specialpermission

to have his eighteen-year-old son admittedas a member.I talkedto menin their

twenties and a fewin theirthirties who toldme theyhad beenputtingoffjoining

themovementby tellingtheirfathers or otherrelatedMasonsthattheywerenot

old

yet'really enough' forit.Even whena father is dead,olderbrothers or other

relativesurgetheiryoungerbrothersthatit was theirfather'swish thatthe sons

shouldjoin. Pressurealso comes fromotherkin who are alreadywithinthe

movementor who arenot.

Mostimportant ofallisthepressure offriends.

Friendship tiesaresignificantamong

theCreoles.It mustbe remembered thatwe arediscussing herea fewthousandmen

who were born,broughtup, had theirschoolingand most of theiruniversity

educationwithina relatively smalltown.Men spendmostof theirleisuretimein

cliquesof friendsand when mostof a man's peersjoin Masonry,one afterthe

otherand becomeabsorbedwithinitsactivities, a greatdeal ofpressure is exerted

on himtojoin. Ifhe doesnot,he is likelyto losehisfriends. A youngengineer told

me thathis Masonicfriends would sometimesrequest'him to leave theroom so

thattheycould say something in theconfidence of Masonicbrothers. He was in

factnot sure,as he was tellingme this,thatthiswas not done deliberately by his

friendsin orderto inducehimtojoin.

Althoughonlyabout a thirdof Creole men are fullmembersof theMasonic

lodges,theothertwo-thirds are to a largeextentstructurally involvedwithinthe

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

THE POLITICS OF RITUAL SECRECY 437

movement. The Creoleson thewholearethehighestandthemostprivileged status

groupin SierraLeone. But theyare themselves internally stratified.A fewscores

of householdscommanda greatdeal of power derivedfrompropertyand from

professionalstanding andhighprestige whichtheyhaveheldformanygenerations.

Below theseare theotherprofessionals, and theseniorcivilservants. Below these

are the clerks,the salesmen,teachers.At the bottomare the relativelypoorer

householdswhosemembersare mainlyskilledand some unskilledworkers.Only

menfromthetwo top sectorstendto be in thelodges.But theCreolesareorgan-

ised in 'famnilies'

whosestructure combineskinshiprelationsand patronage.The

Creolesare bilateralin theirkinshiporganisation, and patrilateral,matrilateralas

well as affinal

kinand sometimes evenfriends, are includedwithinwhata Creole

would call his 'family'.Fromthisit is obviousthatall theCreolesarepotentially

relatedto one another,and thatwhata personwould call his 'family'tendsto be

an ego-centricentity.Nevertheless, a degreeof permanenceand discreteness is

givento a setofkinthroughthesystemofpatronage. Each eminentmanbecomes

thepatronofa largenumberofkinsmensomeofwhomwillevenadoptthename

of the patron,whethertheyare relatedto him patrilaterally, matrilaterallyor

affinally.Even a preliminary studyof thestructure of these'families'is sufficient

to show that each includesmen and women fromall classesof Creoldom.

Althoughthereis at thesametimea tendency forthewealthyand eminentto seek

closesocialrelations withtheirequalsin status, therearestrongeconomic,political,

moraland ritualforcesthatlinkthememberstogether.Thus althoughonlythe

relatively well-to-doarein thelodges,thesearein factthepatronsofthosewho are

notmembers.Patronageinvolvesbothprivileges and obligationsand it is difficult

fora manto remainin thispositionwithoutkeepingin closerelationship withthe

otherpatronswho occupystrategic positionsin thesociety.Masonicmembership

is an important featureof the styleof lifeof any Creole of importance.It is a

collectiverepresentation withoutwhicha man will not be able to partakein the

networkof privilege.A patronis indeedunderstrongpressure to join ifhe does

not wantto forfeit hisrole and hispower.

On deeperanalysis, it willbecomeevidentthatthispressure by relatives,friends,

and statusgroups,operatingon theindividual,is itselfa mechanismof constraint

whose sourceis the wide cleavagebetweenCreolesand non-Creoleswithinthe

SierraLeonepolity,To appreciatethenatureof thisstructural constraint,we must

view it developmentally. I have drawnforthispurposea listof theFreemasonic

lodgesinFreetown, eachbyname,yearofconsecration andconstitution. The estab-

lishment, consecration, and continuity of a lodge are supervised and administered

by the'mother' GrandLodge in Britain.No lodge can be formedunlessit gets

a specialcharterfromthe GrandLodge to certifythatthe lodge is formedin

accordancewithall theregulations of the movement.This chartermustbe dis-

playedin everylodge at everyone of itsmeetingsand withoutit themeetingis

invalid.The chartermustbe renewedannually.Each lodge has a specialserial

numberwithintheconstitution and itsname,addressandotherdetailsareformally

listedin the Year Book of theMotherConstitution (see table i).

The firstpointto be noticedfromthelistis thattheproliferation of thelodges

has not been a gradualprocessbut has occurredin bouts. We can divide the

developmentof Freemasonry in Freetowninto threemajor periods.The first

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

438 ABNER COHEN

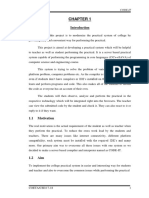

TABLE i. The Freemasonic

Lodgesin Freetownby name,yearofconsecration,

and constitution.

EnglishConstitution ScottishConstitution

Name Year of Name Year of

Consecration Constitution

Freetown I882*

St George I894*

Rokell I899* S. L. Highland I905*

Loyal I9I4 Academic I9I4*

Aboutthirty

yearswithno change

Progressive I947

Wilberforce I947

Tranquility I949

Harmony I950*

Travellers I950

Granville I952

Aboutthirteen

yearswithno change

MountAureol I949

Sapiens I966

Delco I966

Leona I968

Earl ofEglington

andWinton I968

* Lodgeswithasterisk

havebeengrantedRoyal ArchStatus.

phaseis fromI882 to I9I4, whensix lodgeswereformed,fourundertheEnglish

constitution andtwo undertheScottishconstitution. Mostofthemembersofthose

lodgeswere Britishofficials. I am not concernedin thisarticlewiththatperiod.

For thefollowingthreedecades,fromI9I4 to I946, no new lodgeswere estab-

lished.This was roughlytheperiodof indirectrulein BritishWestAfrica,which

came to an end in mostBritishcoloniesshortlyafterthesecondworldwar.

Theninthecourseoffourto fiveyears,fromI947 to 1952, thenumberoflodges

in Freetowndoubled,fromsix to twelve.Thiswas thebeginningofnew political

developments leadingto independence in I96I.

Therefolloweda standstill periodof about thirteen yearswhichroughlyco-

incidedwiththestablepremiership of SirMiltonMargai,endingin I964 withhis

death,and the successionto the premiership of his brother,Sir AlbertMargai.

Thisusheredin a turbulent timewhichcameto an endwiththecoupsd'e'tat of I967

and I968. In the courseof less thanthreeyearsthe numberof lodgesleapt by

nearly5o percent.fromtwelveto seventeen, withall theincreaseoccurringwithin

theScottishconstitution, thenumberof whosedaughterlodgesthusdoubled.

We thushave two phasesof concentrated andintensified'freemasonisation',the

I947-52 period,and thei965-68 period.What is significant in bothperiodsis that

eachinvolveda directand seriousthreatto Creoldom.This emergesclearlyfrom

the wealthof documentation of all sorts,and fromthe detailedstudiesof the

politicsof SierraLeone sincethesecondworldwar by politicalscientists and other

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

THE POLITICS OF RITUAL SECRECY 439

scholars(see particularly CartwrightI970; Kilsen I966; FisherI969). I can here

giveonlya briefoutlineof therelevantevents.

The developmentsof the I947-52 period still remainthe most traumatic

experience in thepsychologyof theCreoles.UntilthentheCreolesweresecurely

entrenched in the Colony-despite the Britishpolicy of restraining themfrom

dominating thenativesfromtheProtectorate. Theirascendancein thecivilservice

and in theprofessions was overwhelming. Even as lateas i950 therewereat least

seventyCreole doctorsas againstthreefromtheProtectorate (Cartwright I970:

24). In I953, 92 percent.of the civil servantswere Creoles.In I947 the British

government presented proposalsforconstitutional reformin SierraLeone aiming

at unifying theColony and theProtectorate and settingthewholecountryon the

pathto independence. The proposalsat thatstagewerenot revolutionary forthe

countryas a whole but theydramatically affected thebalanceof power between

Colony and Protectorate. Among otherthingstheystipulatedthatthe fourteen

Africanmenmbers of thenew LegislativeCouncilshouldbe electedby thepeople.

This virtuallymeantthebeginningof the end of Creole politicalinfluence even

withinwhattheyhad hitherto regardedas theirown home: theColony.

Their reactionwas frantic.In I948 all the major Creole politicalgroupings,

includingthe CombinedRate PayersAssociationand the SierraLeone Socialist

Partypresented a petitionto theSecretary of StatefortheColoniesattacking the

colonialgovernment forintending to givepowerto illiterate'foreigners';i.e. the

peopleof theProtectorate. The Creolesdemandedthatonlytheliterateshouldbe

giventherightto vote.

TherewerebitterexchangesacrossthedeepeningcleavagebetweentheCreoles

and theNatives.Dr H. C. Bankole-Bright, theCreolepoliticalleaderat thetime,

describedtheCreolesand theNativesas 'two mountains thatcan nevermeet'.In

a letterpublishedby the Creole SierraLeone WeeklyNews(26 August,Ig50) he

recalledthattheProtectorate had come intobeing'afterthemassacreof some of

our fathersand grandfathers ... in Mendelandbecausetheywere describedas

"Black Englishmen"'.For the othercamp, Milton Margai,who was soon to

becomethePrimeMinisterof SierraLeone,describedtheCreoles(seeProtectorate

Assemblyi950: 28-3 i) as a handfulof foreigners to whom 'our forefathers' had

given sheltcrand who imaginedthemselvesto be superiorbecause theyaped

Westernmodes of livingbut who had neverbreathedthe truespiritof inde-

pendence.

What is important to notehereis thatalthoughthemoreconservative Creole

elemnents a

fought desperate battlefora long timeandcontinueto do so stilltrying

toputtheclockback,mostof theCreolemoderates andintellectuals

recognised the

futilityof thisstandand triedto adjustto thetimesand makethemostout of the

new opportunities. They soon recognisedthatany attemptby the Creoles to

organisepoliticallyon formallineswould be disastrous becauseof theirhopeless

numerical weaknesses. It shouldbe emphasised thatin theirdeterminationto leave

SierraLeone,theBritishpursueda consistent policyin theAfricanisationof their

administration. Thisentailedthereplacement ofBritishofficials

by Africans,and as

fewNativeswereeducatedenoughto qualify,itwas inevitablethatthebulkofthe

new recruits shouldcome fromamongtheCreoles.The Britishdid theirbestto

educateAfricansparticularly fromthe Protectorate forthenew jobs, by giving

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

440 ABNER COHIIEN

themscholarships forstudyoverseas.But even so and despiteall pressure, 6o per

cent.of the holdersof thesescholarships betweeni9Si and i9S6 were Creoles

(Cartwright I970: 24). Also,as holdersoflandproperty in theColony,theCreoles

beganto reapthebenefits of theimpendingindependence by therisein thevalue

of theirproperty.All thismeantthatthe Creoleswould lose everything if they

stoodas a formalsolidpoliticalbloc withinthenew statestructure, while,ifthey

co-operatedin the maintenance of a liberalregimeon the basis of individual

equalitytheywould gain a greatdeal becauseof theirsuperioreducationand

culturalsophistication. The Creoleswho werethinking alongtheselines,eventually

co-operatedwith the Native-dominated Milton Margai government.Milton

Margai,who was a shrewdpolitician,recognisedthathe could not establisha

governmnent withouttheCreolesand he also recognised theimmensecontribution

thattheCreoleshad made and could stillmake to thecountry.He therefore in-

cludedmanyCreolesin hisParty'srepresentation and retainedCreole menin key

administrative positions.Thus,despitethegrumbling of some Creoleseverynow

and then,a period of co-operationand stability prevailedthroughout Milton

Margai'sregime,endingwithhisdeathin I964.

His brother,AlbertMargaiwho succeededhim,was different in character andin

styleof government. Withina shorttimehe madea seriousattemptto changethe

constitutionin orderto establishofficially a One-Partysystem.He could not do

thiswithoutthecloseco-operation of thecivilservice,thejudiciaryas well as the

But his attemptwas immediately

legislature. opposedby almostall the Creoles

who now shifted theirsupportto theoppositionparty.Oppositionpapersbegan

to agitateagainstAlbertand to exposehis allegedcorruption. The government

broughtthe agitatorsto court.But the courtswere presidedover by Creole

judges and verdictswerein thehandsofjurieswho, becauseof thedemandthat

theyshouldbe literate, werealso Creoleand mostof theaccusedwereacquitted.

This outragedAlbertMargaiwho began to attackominouslyin hisspeechesthe

'doctors,lawyers,and lecturers of Freetown'who were wilfullyrefusing to see

theblessingsof theone partysystem.

Eventsduringthefollowingone or two yearsshow what an influential small

minorityelite can do againstan establishedgovernmentsupportedby a large

sectionof the population.Creole heads of tradeunions,clergymen,lawyers,

doctors,teachers, and universitystudentsusedeveryshredofinfluence theyhad to

bringaboutthedownfallof AlbertMargai.An opportunity presented itselfin the

I967 generalelections whenthemajorityof Creolemen and womenthrewtheir

influenceand their organisationalweight behind the oppositionparty. The

governing party,theSLPP, was defeatedthoughby a narrowmajority(fordetails

see Cartwright I970; FisherI969).

Thus in boththeI947-52 and i965-68 periodstherewas a sharpdramaticturn

of eventswhichbroughtabouta seriousthreatto thecontinuity of Creolepower

andprivilege.The verymenwhosepowerwas mostthreatened in thisway,mainly

thecivilservants and membersof theprofessions, werethosewho filledtheFree-

masoniclodgesin Freetown.Unlesswe assumethatthesemenhad splitpersonali-

ties,we can easilyseethatthetwo processes ofchange,i.e. thedevelopingthreatto

Creole power and the increasein Freemasonicmembership, are significantly

interrelated.Nearlyall thenamesoftheCreoleswho wereinvolvedin thestruggle

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

THE POLITICS OF RITUAL SECRECY 44I

againstAlbertMargaiin I966 and I967 arethoseofwell-knownFreemasons.The

variedformsthatCreoleactiontookto bringaboutthedownfallofAlbertMargai

showeda remarkabledegreeof overallco-ordination whichno formalpolitical

partyor associationwas at thetimecapableof achieving.

An exclusiveorganisation

Largely withoutany consciouspolicy or design,Freemasonicritualsand

organisationhelped to articulatean informalorganisation, which helped the

Creolesto protecttheirpositionin thefaceofincreasing politicalthreat.It did this

in a numberofways,themostimportant beingin providingan effective mechan-

ism for regularcommunication,deliberation,decision-making, and for the

developmentof an authority structureand of an integrated ideology.Although

the membersare dividedinto two constitutions and further, withineach, into

severallodges,thereis a verygreatdeal ofintensive interaction betweenthewhole

membership. Thisis done throughthemanipulation of someof theinstitutions of

Freemasonic organisation.

A Mason can becomea Memberin only one lodge,his 'lodge of birth',into

whichhe is initiated.But he can seek 'affiliation' withinotherlodges,whether

fromhis own constitution or fromthe otherconstitution. Many Masons are

affiliated

to one or more lodges, dependingon theirabilityto meet the high

expensein bothtimeand money.Affiliation withina lodge costsonlyslightly less

thanmembership. When you are affiliated withina lodge you enjoy the same

privilegesand sharein thesameactivities as themembersof thatlodge.I know of

somemenwho are affiliated withinfivelodges.On theindividuallevel,menseek

affiliation

forthesamereasonsmentionedabove in connexionwithmembership.

They may want to associatewitheminentmen who are the membersof other

lodges,to interactsocially,to enjoyeatingand drinkingmorefrequently. Other

Masonsseekaffliation withinotherlodgeswheretheyhave betterprospectsfor

earlierpromotionto thedegreeof MasterMason.

Anotherinstitution, which is probablyeven more importantin establishing

channelsof communication betweenthelodgesis thatof visiting.A Mason can

visitotherlodges,wherehe may or may not have friends. All excepttheRoyal

Archlodgesareopento members fromall degrees.Royal Archlodgeshoweverare

open to onlyreigningor pastMasterMasons.I understood fromMasonsin Free-

town withwhom I talked,thaton averagenearlya quarterto a thirdof those

presentin anylodge meetingare visitors fromotherlodges.

Sociologically,

themostimportant featureoflodgeceremonials is nottheformal

ritualsof the orderbut the banquetingfollowingtheirperformance. It is here,

amidstheavy drinkingand eating,thatMasons are engagedin the processof

true'fraternising'.In my view thisinformalinstitution withinMasonry,whose

procedureis neitherplannednor consciouslypursued,is the mostfundamental

mechanismin weldingthemembersof all thelodgesintoa single,highlyinter-

relatedorganisation.It mustbe remembered thatwe are dealingherewitha small

and limitedcommunity of a fewthousandmenwho werebornand broughtup

withina relativelysmalltown.Indeedtheseventeen lodgesmeetwithinlessthan

one squaremile.In somecasesmanylodgeshavetheirtemplesin thesamebuilding

in thecentreofthetown.Thesearealso themenwho arerelatedto one anotheras

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

442 ABNER COHEN

relatives, affinesorfriends, andwhoattend oneanother's weddings, funerals,and

otherfamily occasions.

Itisobviousthatthewealthier a manis themoremobilehebecomes within the

lodges,andthisbrings usto a secondanda mostfundamental structuralfunction

ofMasonicorganisation. Thisis thatalthough thereis emphasis in Masonry on

equalityand truebrotherhood, Masonicorganisation provideseffective and

efficientmechanisms fortheestablishment ofa strong authoritystructure.Formally,

thisisachieved through theritual promotion within thethree degrees oftheCraft,

theEntered Apprentice, Fellowof theCraft, andMasterMason.Thesedegrees

are thesameunderboththeEnglishand theScottish Constitutions. But the

EnglishConstitution has further degreeswithinwhatis knownas the Royal

Arch.

InitiationintotheFirstDegree,andthenpromotion to theSecond,'raising'to

theThird,andfurther promotion intheRoyalArchDegrees, aremarked byvery

elaborate ritualdramas. Eachstageisalsomarked bynewregaliawithadditional

signsofoffice. Itisalsomarked bytheacquisition offurthersecrets,bynewduties

andnewprivileges. Apartfromtheseritualdegrees thereis alsoin eachlodgea

largenumber ofOffice Bearers ofall sorts, whoareconcerned withtherunning

andorganisation ofthelodge.Andatthetopofthelodgeswithin eachConstitution

there isa DistrictGrandLodge,headedbya District GrandMaster, hisDeputyand

Secretary. A Masteris alwaysaddressed as 'Worshipful Master'.A GrandMaster

is addressed as the'MostWorshipful Master'.The highera Mason'sdegreethe

greater hismobility within, andaccessto,thelodges.A MasterMasoncanenter,

without permission orinvitation, eventheRoyalArchLodges.

Allpromotions areformally onthebasisofattainment inFreemasonic theology

andritual andrequire devotion tothemovement inregular attendance. Butaseach

promotion toa higher degreenecessitates spending moremoneyinfees,inregalia

and,moreespecially inproviding banquets, onlythoseMasonswhocanmeetthese

expenses andwho havethenecessary backingin thelodgeswillseekor accept

promotion. Promotion usually takestimeandsometimes it cantakea manover

tenyearsto becomea MasterMason.Buttheprocess canbe greatly speededup,

andtherearecasesin Freetown ofmenbeingraisedto theThirdDegreewithin

threeyears.

In thisrespect, the Scottish Constitution is morehelpfulthantheEnglish.

Promotion canbe quicker. MasonsfromScottish lodgesinFreetown toldmethey

thought theScottish constitutionwasmoredemocratic thantheEnglish, whichthey

described as conservative.In a Scottish lodgeitis themembers ofthelodgewho

decideon whowillbe raisedto theposition ofMasterandhisDeputywhilein

Englishlodgesthedecision comesfromabove.On thewhole,theScottish con-

stitutionseemstobe moreeasilyadaptable tochanging situations thantheEnglish

one,andI believe thatthisisthemainreason why,asthetableaboveshows, itisnow

morepredominant amongtheCreolesthantheEnglish one.In a rapidly changing

situation itis important fora groupto havea moreflexible articulating ideology

andorganisation. FortheCreoles, thisisindeedcrucial.

Within thehierarchy ofdegrees andoffices intheFreemasonic organisation there

isthusa closerelationship between wealthandposition inthenon-Masonic sphere

ontheonehand,andritual authority within theorderontheother. Theprominent

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

THE POLITICS OF RITUAL SECRECY 443

men in the Masonic order are indeed the prolmiinent miienin SierraLeone in

general.Thereis a closerelationbetweenthetwo spheres.

IndividualMasons oftenmanipulatevarious factorsto gain authorityand

powerwithinthemovement.A man who hasjustjoined a lodge and who will

probablyhaveto takehisplacein thequeuebehindmanyother'brothers'in order

to be raisedto thecovetedstatusof MasterMason, will seekeitheraffiliation to

anotherlodge in whichmiiore opportunities exist,or will groupwithothermenm-

bers,who shouldincludeat leastsevenMasters,in orderto drivean application

throughforthefoundation of a new lodge.If he is a memberof an Englishlodge

he may discoverthathis chancesare betterin affiliation withina ScottishLodge.

And withinthe lodge he will tryto gain the affection and supportof various

cliquesof friends.

Even at thelevelof DistrictLodges,thetwo Masonicorganisations are closely

interrelated,and, takentogether,theyindeed mergein effectto articulateone

unifiedMasonic hierarchy.The presentDistrictGrand Masterof the Scottish

constitutionforexamplewas originally initiatedintoanEnglishconstitution lodge,

was thenaffiliatedto otherlodges from both constitutions,and became founding

Masterof a Scottish lodge.OthereminentMasonsin Freetownhad similarcareers

withintheorder.

Thisintegrated hierarchyof authority is ofimmensesignificance fortheCreoles

as a corporateinterest group.Likethemiddleclassesin manycountries, theCreoles

are in generalnotoriouslyindividualistic and no soonerdoes a leaderbegin to

assumeleadershipthana numberof othermen beginto contesthis claimin the

spiritof' whyhe,notme?'. It mustbe emphasised thatduringtheColonialperiod,

whiletheTemne,Mende,and theothertribesof SierraLeone had theirown local

andparamountchiefswhoseauthority was upheldby theColonialadministration,

theCreoleswerewithouttraditional leadership. Up to thepresent, theCreolesare

treatedlegallyas non-Nativesand theirfamilyand sociallifeis regulatedunder

Britishcivillaw, whiletheNativesaretreatedmainlyaccordingto customary law.

The Creoleshave forlong identified stronglywiththeBritishand do not have

anykindof tribalstructure.

The difficultyin developinga unifiedleadershipand a systemof authority was

further increasedby thefactthat,outsidetheformalpoliticalarena,the Creoles

had several,oftencompeting, hierarchies of authority withindifferent groupings.

One was the churchhierarchy, the otherswere withineach one of the major

professions,includingtheteachers, as wellas property holders.Furthermore, there

was intensive strifewithineachgroupingcharacterised by intensecompetition for

promotionintohigherpositionsand by perpetualtensionbetweensuperiorand

subordinate withinthebureaucratic structure. But whenthemembersof all these

groupingsbecame incorporated withinthe Masonic lodges,theybecame inte-

gratedwithinan all-encompassing authority structurein whichmembersfromthe

higherpositionsof the different non-Masonichierarchies were included.The

differenttypesand basesofpowerwithinthosegroupings wereexpressed in terms

ofthesymbolsandideologyofFreemasonry. A unifiedsystemoflegitimation fora

unifiedauthority structurewas thuscreated.This has been of course,not a once-

and-for-alldevelopment, buta continuing processofinteraction betweentheritual

authority withintheorderand thevariousauthority systems outsideit.

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

444 ABNER COHEN

Freemasonry has thusprovidedtheCreoleswithtllemeansforthearticulation

of the organisational functionsof a politicalgroup. The organisation thathas

emergedis efficient and effective and is thusin sharpcontrastwiththeloose and

feeblepoliticalorganisations in SierraLeone generally.As Cartwright(I970)

pointsout,thepoliticalpartiesof SierraLeone areloose alliancesbetweenvarious

groups,manyof whichshifttheirallegiancefromone partyto anotherunpre-

dictably.But Freemasonicorganisation is strictlysupervisedby the two Grand

Lodgesin Britainwho enforcethesamestrictstandards of organisation thathave

beenevolvedin an advancedand highlyindustrialised society.This is why,in my

view, Freemasonic organisation in SierraLeone todayis one of themostefficient

and effective organisations in thewhole country.It has thuspartlymade up for

Creole numericalweakness.A smallgroupcan indeedgreatlyenhanceitspower

throughrigorousorganisation.

In adoptingFreemasonry in thisway,theCreolesarenotmakinguse of a novel

kindofideologyandorganisation in SierraLeonepolitics.Foritis wellknownthat

SierraLeone and some of herneighbouring countriesconstitute an ethnographic

area whichis especiallycharacterised by thevarietyand multiplicity of itssecret

societies.The roleofthePoro secretsocietyoftheMendein organising andstaging

the so-calledHut Tax War againstthe Britishand the Creolesin I898 is well

documented(see ChalmersI899; Little i965; I966; Scott I960: 173-4). As

Kilsenpointsout (I966: 256-8) the Poro has ever sincebeen used in modern

politicalcontextsdown to the present.Its symbols,ideology,and organisation

have been usedby theSLPP, themajor,Mende-backedpartyof MiltonMargai,

to mobilisevotes and supportin elections.A similaruse of the symbolsand

organisation of secretsocietiesin themodern'politicsof neighbouring Liberiahas

also beenreported(see Libenow I969).

AlthoughI havebeendiscussing herethcpoliticalfunctions of a ritualorganisa-

tion,I am not implyingany kindof reductionism whichaims at explaining,or

ratherexplainingaway,theritualin termsofpoliticalor economicrelations. Nor

am I imputingconsciousand calculatedpoliticaldesignon thepartof men who

observethebeliefsandthesymboliccodesofsuchan organisation. Likemanyother

ritualsystems, Freemasonry is a phenomenon It is a sourceof valuesin

sui generis.

itsown right,and individuals oftenlook at it as an endin itselfand notas a means

to an end. A Creole Mason will be genuinelyoffendedif he is told thathe is

joiningthemovementforpoliticalconsiderations. More fundamentally, theFree-

masonicmovementis officially and formally opposedto thediscussion ofpolitical

issuesin the courseof its formalmeetings.Therc is certainlyno consciousand

deliberateuse of Frcemasonry in politicalmanoeuvring.

But all thisdoesnotmeanthatthemovementhasno politicalaspectsor political

consequences.Althoughman in contemporary societyplays different roles in

differentfieldsofsociallife,theserolesarenevertheless relatedtoone anotherwithin

one 'self','ego' or psyche.A normalmanhashisidentity, his'I', whichis devel-

oped onlythroughtheintegration of thedisparate rolesthathe plays.To achieve

selfhoodat all,a man'sroleas a Mason mustbe broughtintorelationwithhisrole

as a professional,a politician, a husband,a father.

The Creolesgenerally havebeenunderseverepressure andstrainduringthepast

tweity-five yearsor so. Duringthisperiodtheyhavehad to putup withthreats of

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

THE POLITICS OF RITUAL SECRECY 445

varioussorts, in thestreet, in thecourtroom, in parliament. Thesemenarecon-

sciousofandworried abouttheseproblems andtheytalkaboutthemallthetime.

Whentheymeetin theMasonictemples, theymeetto perform theprescribed

formal rituals.

Butwhentheyadjourn tobanqueting, orwhentheymeetinformally

altogether outside theframework ofFreemasonry, whatdo theydiscuss?

I addressed thisquestion to severalMasons.Almostinvariably thereplywas

thattheytalkabout'theusualordinary current problems', whichpeopleusually

talkabout.Thereis no doubtwhatsoever thatthisisso.Butitisnotunreasonable

to conjecturethatthesemendo talkabouttheircurrent problems andabouttheir

anxieties,hopes,andalsodeliberate aboutsolutions. Theydo notevenneedto

talkabouttheseproblems exclusively withinthelodgesor whilebanqueting.

Through thesharing ofthesamesignlanguage, thesamesystem ofbeliefs,

thesame

secretrituals,

andthesameorganisation, andthrough frequent banqueting, strong

moralbondsdevelopbetween themwhichoften transcend, becomestronger than,

manyotherbonds,so thatwhentheymeetoutside thelodgeframework theytalk

together moreconfidentially andmoreintimately thaniftheywerenotbrothers

within thesamemovement. Attend anyofthefrequent ceremonials stagedby the

Creolesintheir ordinary sociallife,suchas weddings, christenings,orgraduation,

andyouwillnotfailto seethatwhilethewomenarebusydancing on theirown

to thewildbeatof theGumbeband,themensitquietlyin cliqueson theside

drinking and talking. If you askthewomenwhattheirmenweredoingthey

will say 'theyare talkinglodge'.Indeedthephrase'talkinglodge' whichis

frequently heardin Freetown society,hastheconnotation of 'talkingpolitics'.

Through theseintimate andexclusive gatherings, within andoutside theframe-

workofthelodge,menpool theirproblems, deliberate aboutthem,tryto find

solutionsto themandeventually developformulae forappropriate action.It is

becauseof all thisdeliberation, communication, andco-ordination of decisional

formulations, thatthereisa remarkable unanimity ofopinionamongtheCreoles

overmajorcurrent problems. Talkaboutanypublicissueonanydaywitha number

ofCreolesin Freetown andyouwillmostprobably hearin comment thesame

statements,usingalmostthesamephrases andwords.Manyexpatriates in Sierra

Leonehaveremarked on thisuniformity ofresponse tomajorissuesonthepartof

theCreoles.In thecourseofa fewmonths I followed a number ofpublicissues,

concentratingparticularly ontwoofthem.Oneissuewasraisedbythreedifferent

menin different situations withintwoto fourdaysofeachother, including one

ina dailynewspaper.

article On enquiry allthreementurned outtobe members

of thesamelodge.In a fewdays'timethestatements aboutthatissuebecame

stereotyped,andtruly becamethe'collective representation', ofa wholegroupof

menand,later,oftheir women.

Freemasonry is, of course,not theonlycultural institution whichhelpsto

articulate

thecorporate organisation ofCreoleinterests. In myview,itis bestto

studyan interest groupin termsof two interconnected, thoughanalytically

separated,dimensions: thepolitical andthesymbolic. Thesymbolic consistsofall

thepatterns ofnormative behaviour withina number ofinstitutions suchas the

church,thefamily, friendship, artandliterature. Mostofthese patterns ofsymbolic

behaviour haveconsequences affectingtheorganisational functions ofthegroup,

although somewillhavemoredirect effectsin articulating certainfunctions than

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

446 ABNER COHEN

others.A singleinstitution,like Freemasonry,will contribute to thearticulation

of different

organisational

functions, suchas communication and decision-making.

On theotherhand,a numberof institutions will jointlyhelp in thearticulation

of a singlefunctionsuch as thatof distinctiveness (fordetails,see Cohen I969:

2oi-ii). To studyCreoldomin thisway would requirea completemlionograph.

What I have attemllpted

hereis simplyto isolatethe structural consequencesof

Freemasonry.

* * * * *

ThroughoutthisdiscussionI have referred to the Creoles as if theywere a

discreteethnicgroup.They indeedaresuch a group,havingtheirown distinct

cultureand theirown history.What is more,theyare stillregardedlegallyas

'non-Native'. They see themselves and are seen by othersas a distinctculture

group.But thisis to some extenta falsepicturebecauseit entails,among other

things,thestrictobservanceof a rigidprincipleof descent,and henceof recruit-

nment. But theCreolesare bilateraland a man will oftenincludewithinwhathe

regardsas his 'family'bothpatrilateral, matrilateral,and affinal

relativesas well

as friends.

Throughoutthehistory of theCreolesin SierraLeone nmen andwomen

of Native descentwere Creolisedthroughvariousprocesses(see Banton 1957;

PorterI963). By acquiringthesymbolsandstyleoflifeofCreoldomandby being

incorporated withinthe Creole social network,theseNativesbecame in effect

Creole.On theotherhand,thereis evidenceofan oppositeprocessgoingon all the

timewherebyCreolesbecameNativesandcametoidentify themselves withdifferent

ethnicgroups.More recently, somne CreoleshavepubliclyrenouncedtheirEnglish

namnes whichtheychangedintoAfrican namesandadvocatedcompleteintegration

with the Natives. Creole men today, and certainlyalmostall the Freemasons

amongthem,declarepubliclythattheyareopposedto 'tribalism',andplaydown

theirdistinctiveidentityas Creoles.

Creoldomn withinthe mnodern SierraLeone polityis essentiallya statusgroup

markedofffromothersocialgroupsby a specialstyleof lifeand by a densenet-

workofrelationships andco-operation. Althoughtheyareinternally stratified,

they

standas a groupon theirown withinthewidersociety.Thereis no doubtthat

Freemasonry has helpedthemto co-ordinatetheirstruggleto preservetheirhigh

status.It mustbe remembered thatthe Creolesare essentially professionals and

wage earners.Theyarenotexploiters. Theyhave beenthemainfactorin keeping

thecountry's institutions

liberal.UntilveryrecentlySierraLeone was one of the

few statesin theThirdWorld whichwas stilldemocratic.5 The Creoleswantthe

countrytoremainliberalnotonlybecauseoftheirideologicalzeal,butalsobecause

theyrealisethat,as long as thereis freecompetition forjobs in the civilservice

and theprofessions they,withtheiradvancedschoolingsystem, theirWesternstyle

oflife,and theadvantagestheyhavehad overothergroupsin thesefieldsforover

a centuryand a half,are likelyto win and to maintaintheirpresenthighsocial

status.

One of thesociologicallessonswe can learnfromthestudyof a grouplikethe

Creolesfortheunderstanding ofWesternindustrial societiesisthestudyofclasses-

particularlythehigherclasses-asgroupswhichareinformally organisedforaction

througha varietyof institutions like Freemasonry. The associationbetweenFree-

This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Thu, 19 Sep 2013 01:14:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Downloaded from http://iranpaper.ir

http://www.itrans24.com/landing1.html

THE POLITICS OF RITUAL SECRECY 447

masonry andthehighersocialclassesin Britainand theU.S.A. hasbeenknownfor

a longtimenow. What I havetriedto do in thisarticleis to indicatehow thiscult

operatesin articulating a corporateorganisation fora groupof highlyindividual-

isticpeople.An analysisof thistypecan perhapssupplement thatby forexample

LuptonandWilson(I959) in theirwell-knownstudyofdecision-makers in Britain.

Freemasonry offerstwo majorfunctions to itsmembers:an exclusiveorganisa-

tionand a mechanism forthecreationof a brotherhood. Throughupholdingthe

principleof secrecy,or ratherof themonopolyof secrets, Freemasons are able to

develop,maintain, andruna vast,intricate, andhighlycomplexorganisa-

efficient,

tion,withitssymbolsof distinctiveness, channelsof exclusivecommunication,

structure of authority, ideology,and frequentsocialisation throughceremonials.

Throughitsnetworksof lodges,itsritualdegreesand hierarchical structure, its

institutions of affiliation

andvisiting,and theexistenceof threedifferent constitu-

tions,it is particularlysuitedto operatein thehighlydifferentiated and complex

structure of ourindustrial society.Forit is capableofarticulating thegroupingsof

different occupationaland social categoriesof people, allowingboth unityand

diversity.

As menjoin theorganisation, theimpersonalcharacter of a socialcategorylike

classgivesway to therapiddevelopment of moralbondsthatlinkitsindividuals.

Throughthesharingofcommonsecretsand ofa commonlanguageofsigns,pass-

words,and hand-clasps,throughsharingthe humilitiesof the ceremonialsof

initiation,throughmutualaid,thefrequent communionin worshipping andeating

together,and the rulesto settledisputesamicablybetweenthem,the members

are transformed into a truebrotherhood. This combinationof strict,exclusive,

organisation, with the primarybonds of a brotherhood, makesFreemasonry a

powerfulorganisation in contemporary society.

Freemasonry has different structural

functions underdifferent socialconditions,

and in itshistoryin Europe it has servedto organiseconservative as well as pro-

gressivemovements. Itsfunctions aredetermined neitherby itsdoctrinenorby its

formalorganisation. But it is definitelyan organisation especiallysuitedforthe

well-to-do.What is more,becauseof itssecrecyand itsrulesof recruitment, it is

such thatonce it is capturedor dominatedby a stronginterest group,or by a

numberof relatedinterestgroups,it tendsto become the exclusivevehiclefor

promotingtheinterests of thatgroup.Throughsecretballotingand therequire-

mentof almostcompleteconsensusfor admittingnew members,it can easily