Nest Chinese Name Pronunciation

Diunggah oleh

Hafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Nest Chinese Name Pronunciation

Diunggah oleh

Hafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

PRONUNCIATION GUIDE FOR NON-ENGLISH NAMES

In the Seattle-Tacoma area, almost 20% of the population speaks a language other than English at home. The number of

non-native English speakers increases even more at colleges and universities in the area, with the large number of

international students. Names in some languages, like Spanish and Japanese, are fairly easy for English speakers to

pronounce, owing to a general familiarity with those languages and the absence of many unfamiliar sounds. Others

have sounds not found in English, which English speakers either have to attempt to master or work around (Khalid with

a “kh” sound, like clearing your throat, becomes “Kalid”). Finally, still other languages have Latin letters or letter

combinations which have completely different pronunciations than we would expect (Vietnamese Nguyen is

pronounced “nwen”, like Gwen with an “n”).

In most Asian countries, last name (family name) comes first and first name comes last. Asians living in the US know

family names come last here, but visitors sometimes feel more comfortable using thefamily name first.

Most people with non-English names expect Americans to blow the pronunciation; some take on English first names to

avoid that indignity, or get used to it. You will make a big positive impression, however, if you at least come close to the

right pronunciation. Asking how to pronounce a name is always appreciated, particularly if you write down the

phonetics and remember how to pronounce it later (asking how to pronounce it again and again becomes tedious).

Here is a brief guide for pronouncing non-English names for the language groups we’re most likely to encounter (with

much thanks to Cal Poly Pomona’s website on foreign names).

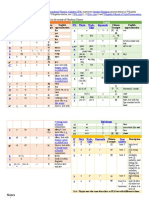

MANDARIN CHINESE (MAINLAND CHINA (PRC), TAIWAN, SINGAPORE)

Chinese is a close second behind English as the most widely spoken language in the world. Putonghua, or Mandarin

Chinese, was standardized from the Beijing dialect over the last century, given a simplified writing system in Chinese and

English (Pinyin) in the 1950s, and used exclusively as the language of education, government and culture in China.

Today, almost everyone in China can speak Mandarin, although often with an accent that reveals their home region.

There are two kinds of transliteration systems used, Wade-Giles (the old system, still used in Taiwan) and Pinyin. About

1.3 billion people use Pinyin and maybe 50 million (Taiwan and overseas Chinese) use Wade-Giles, so we’ll go with

Pinyin. Like Vietnamese and Thai, Chinese is a tonal language in which meaning is determined partly by tone or pitch

(giving Chinese a “sing-song” sound to English speakers). Forget tones. If you can master Chinese tones, you don’t

need this guide.

Main “problem” letters and English pronunciation:

X – sh Q – ch Zh – mix of j and ch; go with “ch” E – uh (uh-oh) C, Z – ts (cats) Yi – ee

Note: HS in Wade-Giles = X (sh) in Pinyin. Hsiao = xiao = shao

Zhang – chang Qianqian – chenchen Xi – shee Qingdao – chingdao (city)

He – huh Henan – huhnan (province) Xinzhu – sheenchu Yiming – Eeming

Zhao – chao Meng – muhng Cai – tsai Zeng – tsuhng

Xiao – shao Qisheng – cheeshuhng Zhu – chu Xi’an – sheean (city)

CANTONESE CHINESE

About 30% of the Chinese people speak a Chinese dialect other than Mandarin. The dialect with greatest status is

Cantonese, found in Hong Kong and Guangdong province in southern China. Cantonese is widespread in the US, owing

to the fact that most early Chinese immigrants came from Guangdong province and Hong Kong. Hong Kong students are

also well represented in US colleges and universities. Accordingly, it is useful to learn how to pronounce Cantonese

names.

Cantonese is more difficult for English speakers to pronounce than Mandarin, for several reasons. One, it has more

tones than Mandarin. Two, Cantonese has nasal sounds unlike anything in English (ng, mg). Three, the transliteration

system is not as logical as Pinyin. Like names using other national transliteration systems, some names can be

pronounced using standard English phonetics. Others can not. Here are some of the “nots”, first line last names and

second line first names:

Au – ngao Ho – haw Hui – hayoo Koo – goo Mok – mau Ng – mg Tang – doong

Ka-Ling – gahleeng Kok-Wing – kawweeng Sau-Ha – sowhan Shuk-Yee – suhyee Tak-Wah – duhwah

INDONESIAN

Indonesian is the largest member of the Malayo-Polynesian family of languages, which stretches from Hawaii to

Madagascar, off the coast of southern Africa. Indonesian and Malayan (the language of Malaysia) are mutually

intelligible. An “inclusive” language like English, Indonesian has also been influenced by Dutch, Javanese and now

English. As one would expect in an island nation 3,000 miles wide, there are many dialects, Javanese being the largest.

Like Mandarin Chinese, however, “Bahasa Indonesia” is the only language taught in school and is a major factor unifying

the country.

The vowels are somewhat similar to Japanese and Spanish, except for “a”, which has two variants. Other than that,

Indonesian names are pretty easy to pronounce for English speakers. A high proportion of Indonesian students in the US

are of Chinese origin. About 70% of them have English or European first names , 20% Indonesian, and 10% Chinese first

names. Government policy forced Chinese to take official Indonesian last names, but with more liberal policy some of

the Chinese names, never lost but just not officially used, are reappearing. The first line of names below are last names,

the second boys’ first names, the third girls’ first names, and the last two the most popular Indonesian first names.

A – ah or uh (father or up) E – ay (Abe) I – ee (eagle) O – oh (boy) U – oo (boo)

Darmadi – durmudee Gunawan – goonawan Irawan – eerawan Sanjaya – sunjaya Tedjo – tajo

Bambang – bumbung Hadi – hudee Hengki – hangkee Indra – eendra Ivan – eefun Yandi – yundee

Devi – dayvee Dewi – daywee Erlin – airleen Fanny – funny Widya – weedya Yanti – yuntee

Most popular Indonesian names: Budi (boodee), Siti (seetee), Trisno (treesno), Purwatini (purwateenee) and Susilo

(sooseelo).

JAPANESE

Rejoice, English speakers. Japanese names are pronounced pretty much as written in Latin letters. The vowels are

identical to Spanish, and the famous “l/r” confusion in English comes from the fact that one letter in Japanese is

pronounced as a kind of blend of the two. Penultimate “i” vowels are usually dropped in long words or names

(Yamashita becomes “yamashta”), and all syllables in Japanese have equal stress. Other than that, Japanese names

should be pretty easy for English speakers to handle.

A – ah (father) E – ay (wait) I – ee (feet) O – oh (hero) U – oo (Sue)

KOREAN

Most Korean names in Latin letters are fairly easy to pronounce for English speakers. Some Korean vowels are very

different from English vowels, but close is usually good enough. There is no standard Latin alphabet spelling system for

Korean, so the same names can be spelled several different ways. For example, “Lee”, one of the most common Korean

last names, can also be spelled Yi or Rhee. It is pronounced “ee” like the letter “e”, although Koreans with that last

name will expect to be called “Lee” outside of Korea.

Korean first names have two parts, like Eun Young and Min Ho. Sometimes they are spelled as one word, and

sometimes two. Koreans don’t use the first part as a name or nickname, but non-Koreans often do, so some Koreans go

by Eun or Min outside Korea to make things easy. The first line of the names below are family names, the second, first

names.

Main “problem” letters and English pronunciation:

SI – shee K – g as in “gas” P – usually “b” CH – j or ch

Kim – geem Park – bak Lee – ee Choi – choah Lim – eem Kang – gong

Eun-Young – unyoung Eun-A – una Hye-Su – hiesu Cho – jo Jung-Yeol – jungyul

VIETNAMESE

Like Chinese, Vietnamese is tonal, meaning different pitches (rising, like we use in asking a question, falling, etc.) change

the meaning of words. For this purpose, however, forget tones. The writing system was developed by Portuguese and

French priests in the 1600s and 1700s, and froze into place despite the later development of the language. This partly

explains why the script doesn’t match the actual pronunciation that well, much like the English spelling of words like

eight, through and knife. Some Vietnamese names are pronounced as they look to English speakers, while some are

quite different. Here are some of the latter (top line last names, bottom line first names):

Duong – yung Le – lay Ly – lee Ngo – nwo Nguyen – nwen Vo – vah

Diem – yeeyim Dung – young Tho – toy Thuy – twee Tuyet – tweeit Viet – wee-et Xuan – swuhn

Name Pronunciation Guides

X – sh Q – ch Zh – mix of j and ch; go with “ch” E – uh (uh-oh) C, Z – ts (cats) Yi – ee

Note: HS in Wade-Giles = X (sh) in Pinyin. Hsiao = xiao = shao

Zhang – chang Qianqian – chenchen Xi – shee Qingdao – chingdao (city)

He – huh Henan – huhnan (province) Xinzhu – sheenchu Yiming – Eeming

Zhao – chao Meng – muhng Cai – tsai Zeng – tsuhng

Xiao – shao Qisheng – cheeshuhng Zhu – chu Xi’an – sheean (city)

Two online guides—

http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~zhuxj/readpinyin.html

http://www.monash.edu.au/lls/China/teaching/names2.xml

Ross Jennings, January 2010

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Art of WarDokumen300 halamanThe Art of WarVu Harry86% (7)

- 1.classical Chinese For Everyone - Absolute Beginner PDFDokumen163 halaman1.classical Chinese For Everyone - Absolute Beginner PDFAtanu Datta100% (10)

- The Art of War - Tzu SunDokumen387 halamanThe Art of War - Tzu SunRaghava 030Belum ada peringkat

- Periplus Pocket Cantonese Dictionary: Cantonese-English English-Cantonese (Fully Revised & Expanded, Fully Romanized)Dari EverandPeriplus Pocket Cantonese Dictionary: Cantonese-English English-Cantonese (Fully Revised & Expanded, Fully Romanized)Belum ada peringkat

- Mandarin Chinese for Beginners: Mastering Conversational Chinese (Fully Romanized and Free Online Audio)Dari EverandMandarin Chinese for Beginners: Mastering Conversational Chinese (Fully Romanized and Free Online Audio)Penilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (2)

- Speakout Advanced Pronunciation Extra With Answer KeyDokumen34 halamanSpeakout Advanced Pronunciation Extra With Answer KeyHafid Tlemcen Rossignol Poète100% (1)

- Survival Chinese: How to Communicate without Fuss or Fear Instantly! (A Mandarin Chinese Language Phrasebook)Dari EverandSurvival Chinese: How to Communicate without Fuss or Fear Instantly! (A Mandarin Chinese Language Phrasebook)Penilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (7)

- PhoneticsDokumen68 halamanPhoneticsClaudita Mosquera75% (4)

- Thailanguagebook 1 090905082237 Phpapp01Dokumen52 halamanThailanguagebook 1 090905082237 Phpapp01Legner Ranises100% (1)

- 1 He Teachers, Tradl-Rlons, and Literature of Asian /F//1S0O1/1Dokumen486 halaman1 He Teachers, Tradl-Rlons, and Literature of Asian /F//1S0O1/1Denys Malta100% (1)

- HSK 1 in A NutshellDokumen192 halamanHSK 1 in A NutshellChanBelum ada peringkat

- Immanuel C.Y. Hsu-The Rise of Modern China-Oxford University Press (1995)Dokumen1.142 halamanImmanuel C.Y. Hsu-The Rise of Modern China-Oxford University Press (1995)Fernando Pureza100% (4)

- Yin & Yang and The I ChingDokumen24 halamanYin & Yang and The I ChingRahul Roy100% (2)

- Foreign Language MandarinDokumen12 halamanForeign Language MandarinFar Mie100% (1)

- Jyutping Pronunciation GuideDokumen3 halamanJyutping Pronunciation GuideKarelBRGBelum ada peringkat

- An Introduction To Chinese Language 10 2011Dokumen18 halamanAn Introduction To Chinese Language 10 2011reemas_94Belum ada peringkat

- CN Mandarin Language Lessons PDFDokumen26 halamanCN Mandarin Language Lessons PDFpanshanrenBelum ada peringkat

- Pimsleur Chinese I - A Pronunciation and Character GuideDokumen234 halamanPimsleur Chinese I - A Pronunciation and Character GuideDavid Kim100% (12)

- Chinese for Beginners: A Comprehensive Guide for Learning the Chinese Language QuicklyDari EverandChinese for Beginners: A Comprehensive Guide for Learning the Chinese Language QuicklyPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (32)

- Chinese Phrase A Day Practice Volume 1: Audio Recordings IncludedDari EverandChinese Phrase A Day Practice Volume 1: Audio Recordings IncludedPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (3)

- Chinese Elephant Rock WorkbookDokumen119 halamanChinese Elephant Rock WorkbookHahahaBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction To Chinese LanguagesDokumen42 halamanIntroduction To Chinese LanguagesSim Tze Wei100% (1)

- Vietnamese Picture Dictionary: Learn 1,500 Vietnamese Words and Expressions - The Perfect Resource for Visual Learners of All Ages (Includes Online Audio)Dari EverandVietnamese Picture Dictionary: Learn 1,500 Vietnamese Words and Expressions - The Perfect Resource for Visual Learners of All Ages (Includes Online Audio)Belum ada peringkat

- Guide To I Ching Master YuDokumen19 halamanGuide To I Ching Master Yupptmnlt100% (1)

- ChineseWithMike PDFDokumen198 halamanChineseWithMike PDFflo108100% (1)

- George Findlay Andrew - A Different DrumbeatDokumen164 halamanGeorge Findlay Andrew - A Different DrumbeatRay Moore100% (1)

- Periplus Pocket Mandarin Chinese Dictionary: Chinese-English English-Chinese (Fully Romanized)Dari EverandPeriplus Pocket Mandarin Chinese Dictionary: Chinese-English English-Chinese (Fully Romanized)Belum ada peringkat

- Tuttle Pocket Mandarin Chinese Dictionary: English-Chinese Chinese-English (Fully Romanized)Dari EverandTuttle Pocket Mandarin Chinese Dictionary: English-Chinese Chinese-English (Fully Romanized)Belum ada peringkat

- Speak and Read Chinese: Fun Mnemonic Devices for Remembering Chinese Words and Their TonesDari EverandSpeak and Read Chinese: Fun Mnemonic Devices for Remembering Chinese Words and Their TonesPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (4)

- Easy Chinese Phrase Book: Over 1500 Common Phrases For Everyday Use and TravelDari EverandEasy Chinese Phrase Book: Over 1500 Common Phrases For Everyday Use and TravelBelum ada peringkat

- PronunciationDokumen2 halamanPronunciationLuis Carlos Ojeda GarcíaBelum ada peringkat

- Speakout Advanced Pronunciation Extra With Answer Key PDFDokumen17 halamanSpeakout Advanced Pronunciation Extra With Answer Key PDFHafid Tlemcen Rossignol Poète100% (1)

- Chinese Language Guide and Phrase BookDokumen17 halamanChinese Language Guide and Phrase BookSaket ChandraBelum ada peringkat

- Hangul AlphabetDokumen7 halamanHangul AlphabetivcbeautyBelum ada peringkat

- Startup Chinese Textbook SampleDokumen85 halamanStartup Chinese Textbook SampleZeljkaKrpan0% (1)

- Korean Picture Dictionary: Learn 1,500 Korean Words and Phrases (Ideal for TOPIK Exam Prep; Includes Online Audio)Dari EverandKorean Picture Dictionary: Learn 1,500 Korean Words and Phrases (Ideal for TOPIK Exam Prep; Includes Online Audio)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (9)

- ASSIGNMENT - Phonology of CantoneseDokumen6 halamanASSIGNMENT - Phonology of CantoneseGerald Ordinado PanoBelum ada peringkat

- A Brief Introduction of Chinese LanguageDokumen40 halamanA Brief Introduction of Chinese LanguagesankyuuuuBelum ada peringkat

- ChineseDokumen19 halamanChineseNhuQuynhDo100% (1)

- Mini Vietnamese Dictionary: Vietnamese-English / English-Vietnamese DictionaryDari EverandMini Vietnamese Dictionary: Vietnamese-English / English-Vietnamese DictionaryBelum ada peringkat

- Mini Mandarin Chinese Dictionary: Chinese-English English-ChineseDari EverandMini Mandarin Chinese Dictionary: Chinese-English English-ChineseBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson 1 - Butuanon DialectDokumen8 halamanLesson 1 - Butuanon DialectCharina May Lagunde-Sabado100% (1)

- Ming History GuideDokumen460 halamanMing History GuideColaBelum ada peringkat

- Chinese Writing LessonDokumen29 halamanChinese Writing Lessonsky90% (10)

- An English Homophone DictionaryDokumen44 halamanAn English Homophone DictionaryErna JukićBelum ada peringkat

- An English Homophone DictionaryDokumen44 halamanAn English Homophone DictionaryErna JukićBelum ada peringkat

- (Blackwell Companions To Philosophy) Eliot Deutsch, Ron Bontekoe-A Companion To World Philosophies-Wiley-Blackwell (1999)Dokumen627 halaman(Blackwell Companions To Philosophy) Eliot Deutsch, Ron Bontekoe-A Companion To World Philosophies-Wiley-Blackwell (1999)PabloVicari100% (1)

- The Mandarin LanguageDokumen6 halamanThe Mandarin LanguageRicalyn FloresBelum ada peringkat

- Literature Review: 2.1 Review of Theoretical BackgroundDokumen9 halamanLiterature Review: 2.1 Review of Theoretical BackgroundTuanBelum ada peringkat

- A Typological Description of Modern Mandarin ChineseDokumen20 halamanA Typological Description of Modern Mandarin ChineseLamnguyentai100% (1)

- Foreign Language MandarinDokumen12 halamanForeign Language MandarinFar MieBelum ada peringkat

- Mastering The Basic ChineseDokumen4 halamanMastering The Basic ChineseMohamed Mouha YoussoufBelum ada peringkat

- Why Zhuyin?: Reason #1: English Spelling Is Confusing and RidiculousDokumen8 halamanWhy Zhuyin?: Reason #1: English Spelling Is Confusing and RidiculousOrva LnBelum ada peringkat

- Notes On A Course in Phonetics (Summary)Dokumen201 halamanNotes On A Course in Phonetics (Summary)Boshra HosseinpourBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson 1 Introduction About Chinese LanguageDokumen6 halamanLesson 1 Introduction About Chinese LanguagecchelloBelum ada peringkat

- Saturno, Jeafrylle Dave E. - Bped 3-1 - FL3 - Assignment 1Dokumen3 halamanSaturno, Jeafrylle Dave E. - Bped 3-1 - FL3 - Assignment 1dasij3880Belum ada peringkat

- Learn Philippine Hokkien Part I: Pe̍h-Ōe-Jī Lán-Lâng-ŌeDokumen4 halamanLearn Philippine Hokkien Part I: Pe̍h-Ōe-Jī Lán-Lâng-ŌeRizaBelum ada peringkat

- Adam RossDokumen10 halamanAdam RossStenlyIvanMamanuaBelum ada peringkat

- English Orthography PowerPoint 022322 Spring 2022Dokumen20 halamanEnglish Orthography PowerPoint 022322 Spring 2022Andres AzanaBelum ada peringkat

- 01 Introduction and Typological FeaturesDokumen5 halaman01 Introduction and Typological FeaturesglamroxxBelum ada peringkat

- Cantonese OmniglotDokumen8 halamanCantonese OmniglotKarelBRGBelum ada peringkat

- Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Language Basics: Una King Wooster City SchoolsDokumen13 halamanChinese, Japanese, and Korean Language Basics: Una King Wooster City Schoolsztanga7@yahoo.comBelum ada peringkat

- Linguistic AnalysisDokumen14 halamanLinguistic AnalysisHaizeeZhuBelum ada peringkat

- A Handbook On English Grammar and WritingDokumen36 halamanA Handbook On English Grammar and WritingSagar KathiriyaBelum ada peringkat

- Elcs Lab Manual (R13) by Raja Rao PagidipalliDokumen79 halamanElcs Lab Manual (R13) by Raja Rao PagidipalliRaja Rao PagidipalliBelum ada peringkat

- Základní Škola, Praha 9 - Satalice, K Cihelně 137: A Comparison of Languages: Chinese and EnglishDokumen10 halamanZákladní Škola, Praha 9 - Satalice, K Cihelně 137: A Comparison of Languages: Chinese and Englishqiang huangBelum ada peringkat

- Module 2 Application Researching Students' Mother TonguesDokumen8 halamanModule 2 Application Researching Students' Mother TonguesbrianBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson 1 - Butuanon DialectDokumen10 halamanLesson 1 - Butuanon DialectCharina May Lagunde-SabadoBelum ada peringkat

- ChineseDokumen21 halamanChineseKhuong LamBelum ada peringkat

- MA 15 LING6005 Assignment02part1 LaiThuyNgocHuyenDokumen6 halamanMA 15 LING6005 Assignment02part1 LaiThuyNgocHuyenNguyên ĐoànBelum ada peringkat

- Characteristics of The Japanese LanguageDokumen5 halamanCharacteristics of The Japanese LanguageJune CostalesBelum ada peringkat

- Latin SampleDokumen15 halamanLatin SamplejustinedrexelBelum ada peringkat

- Reading ReportDokumen6 halamanReading ReportElizabehReyesBelum ada peringkat

- EzE Ke Eqglix - IntroductionDokumen6 halamanEzE Ke Eqglix - IntroductionStephen WatsonBelum ada peringkat

- The English Alphabet Has 26 LetterDokumen4 halamanThe English Alphabet Has 26 LetteriammiguelsalacBelum ada peringkat

- Grammar of PonteDokumen16 halamanGrammar of PontemahnejrBelum ada peringkat

- Aqidah02248 شرح العقيدة الواسطية الهراس عفيفيDokumen173 halamanAqidah02248 شرح العقيدة الواسطية الهراس عفيفيHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat

- Word Stress in EnglishDokumen6 halamanWord Stress in EnglishHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat

- Methodology of Educational Research - EDCN-801C - English - 21072017 PDFDokumen196 halamanMethodology of Educational Research - EDCN-801C - English - 21072017 PDFvipul mishraBelum ada peringkat

- Légitimité Et Devenir en Situation Linguistique Minoritaire: Minorités Linguistiques Et SociétéDokumen27 halamanLégitimité Et Devenir en Situation Linguistique Minoritaire: Minorités Linguistiques Et SociétéHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat

- English PhoneticsDokumen18 halamanEnglish PhoneticsElena SimonaBelum ada peringkat

- P Final Part5 PDFDokumen46 halamanP Final Part5 PDFHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat

- Meetisga Book of This Kind, Admitting Its: 8. Eeweeri YDokumen2 halamanMeetisga Book of This Kind, Admitting Its: 8. Eeweeri YHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat

- Word Stress in English PDFDokumen99 halamanWord Stress in English PDFHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat

- English TodayDokumen6 halamanEnglish TodayHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat

- Meetisga Book of This Kind, Admitting Its: 8. Eeweeri YDokumen2 halamanMeetisga Book of This Kind, Admitting Its: 8. Eeweeri YHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat

- Guide Prononciation enDokumen99 halamanGuide Prononciation enHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat

- Kristo-Ch 7 PDFDokumen31 halamanKristo-Ch 7 PDFHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat

- Betty Cried As She Left in The PlaneDokumen1 halamanBetty Cried As She Left in The PlaneHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat

- Syllable Types: Phonics Grades 3-5 Lesson 8Dokumen2 halamanSyllable Types: Phonics Grades 3-5 Lesson 8Hafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat

- Computer-Assisted Programme For The Teaching of The English Syllable in RP Allophonic PronunciationDokumen25 halamanComputer-Assisted Programme For The Teaching of The English Syllable in RP Allophonic PronunciationHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat

- Learning English Syllabification RulesDokumen14 halamanLearning English Syllabification RulesBoubaker GMBelum ada peringkat

- FREN2020 Course OutlineDokumen3 halamanFREN2020 Course OutlineHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat

- E Book of Pronunciation Practice PDFDokumen40 halamanE Book of Pronunciation Practice PDFHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat

- Epi 04 PDFDokumen59 halamanEpi 04 PDFHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat

- Basics of English PhoneticsDokumen42 halamanBasics of English PhoneticsSusan ThomasBelum ada peringkat

- Words That Are Both Nouns and Verbs PronunciationDokumen124 halamanWords That Are Both Nouns and Verbs PronunciationHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat

- Nouns and Verbs With Changes in Pronun (2) ..Dokumen3 halamanNouns and Verbs With Changes in Pronun (2) ..anestesistaBelum ada peringkat

- Kristo-Ch 7 PDFDokumen31 halamanKristo-Ch 7 PDFHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat

- Preverjanje TP5 ResitevDokumen5 halamanPreverjanje TP5 ResitevHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat

- اللؤلؤة - جون شتاينبكDokumen99 halamanاللؤلؤة - جون شتاينبكjijimacBelum ada peringkat

- Ming History GuideDokumen460 halamanMing History GuideVictor ApolonioBelum ada peringkat

- The Oxford History of Modern China 2Nd Edition Jeffrey N Wasserstrom Full ChapterDokumen67 halamanThe Oxford History of Modern China 2Nd Edition Jeffrey N Wasserstrom Full Chaptermary.brown530100% (5)

- The Oxford Illustrated History of Modern China (Jeffrey N. Wasserstrom Ian Johnson) (Z-Library)Dokumen374 halamanThe Oxford Illustrated History of Modern China (Jeffrey N. Wasserstrom Ian Johnson) (Z-Library)FoxyBelum ada peringkat

- Can You Read Classical Chinese - Do You Know All 50,000 Characters - QuoraDokumen30 halamanCan You Read Classical Chinese - Do You Know All 50,000 Characters - QuoraAtanu DattaBelum ada peringkat

- China's Republican Revolution The Case of Kwang...Dokumen380 halamanChina's Republican Revolution The Case of Kwang...Wen LinBelum ada peringkat

- Mandarin IntroductionDokumen9 halamanMandarin IntroductionservantkemerutBelum ada peringkat

- Hinton, William - Shenfan - The Continuing Revolution in A Chinese Village.Dokumen541 halamanHinton, William - Shenfan - The Continuing Revolution in A Chinese Village.JoséArdichottiBelum ada peringkat

- Help:IPA/Mandarin: F J K L M N Ŋ P ADokumen3 halamanHelp:IPA/Mandarin: F J K L M N Ŋ P APhan THanh VanBelum ada peringkat

- Diccionario de Historia Militar China ContemporáneaDokumen372 halamanDiccionario de Historia Militar China ContemporáneaJosé Gregorio Maita RuizBelum ada peringkat

- The Romanization of Chinese Language: Huang Xing Xu FengDokumen13 halamanThe Romanization of Chinese Language: Huang Xing Xu FengElok MawarniBelum ada peringkat

- Nest Chinese Name PronunciationDokumen3 halamanNest Chinese Name PronunciationHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteBelum ada peringkat