Damming Afghanistan

Diunggah oleh

Asfandyar DurraniHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Damming Afghanistan

Diunggah oleh

Asfandyar DurraniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Damming Afghanistan: Modernization in a Buffer State

Author(s): Nick Cullather

Source: The Journal of American History, Vol. 89, No. 2, History and September 11: A Special

Issue (Sep., 2002), pp. 512-537

Published by: Organization of American Historians

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3092171 .

Accessed: 13/02/2014 05:25

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Organization of American Historians is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

The Journal of American History.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Damming Afghanistan:

Modernizationin a Buffer State

Nick Cullather

For suggestionson how to use this articlein the United Stateshistory surveycourse,

see our "Teaching the JAH" Web site supplement at <http://www.indiana.edu/

_jah/teaching>.

In May 1960, the historianArnoldJ. Toynbeeleft Kandaharand drove ninety miles

on freshlypaved roadsto LashkarGah, a modern planned city known locally as the

New Yorkof Afghanistan.At the confluence of the Helmand and Arghandabrivers,

close against the ancient ruins of Qala Bist, LashkarGah'seight thousand residents

lived in suburban-styletracthomes surroundedby broadlawns. The city boasted an

alabastermosque, one of the country'sbest hospitals, Afghanistan'sonly coeduca-

tional high school, and the headquartersof the Helmand ValleyAuthority,a multi-

purpose dam project funded by the United States.This unexpectedproliferationof

modernity led Toynbee to reflect on the warning of Sophocles: "the craft of his

engines surpassethhis dreams."In the areaaroundKandahar,traditionalAfghanistan

had vanished. "The domain of the Helmand Valley Authority,"he reported, "has

become a piece of Americainserted into the Afghan landscape.... The new world

they are conjuring up out of the desert at the Helmand River'sexpense is to be an

America-in-Asia."I

Toynbee'simage sits uneasilywith the visualsof the recentwar.In the granitebat-

tlescapescapturedby the camerasof the Al-Jazeeranetworkin the days afterSeptem-

ber 11, 2001, Afghanistanappearedas perhapsthe one spot on earth unmarkedby

the influence of American culture. When correspondentsreferredto Afghanistan's

Nick Cullatheris associateprofessorof history at Indiana University.

This essaywas researchedand written between the beginning of the bombing campaign in late Septemberand

the mopping up of Taliban resistancearound Tora Bora in early December 2001. Like many colleagues, I found

myself called upon, without benefit of expertise,to place the war in a historicalcontext. The lecture that became

this essaywas based on materialsfound in the Indiana University Libraryand online and in a few archivaldocu-

ments sent by friends. This is a preliminarystudy that I hope will inspire additional researchon the history of the

United States in Afghanistan. I am grateful to Lou Malcomb and the staff of the Government Publications

Department of the Indiana University Library,Melvyn Leffler,Andrew Rotter, and Michael Latham for helpful

comments; to David Ekbladhfor his contribution of documents; and to Alison Lefkovitzfor researchassistance.

Readersmay contact Cullatherat <ncullath@indiana.edu>.

1 Mildred Caudill, Helmand-ArghandabValley Yesterday,

Today,Tomorrow(LashkarGah, 1969), 55-59; Hafi-

zullah Emadi, State, Revolution,and Superpowersin Afghanistan (New York, 1990), 41. Sophocles quoted in

Arnold J. Toynbee, BetweenOxusandJumna (New York, 1961), 12; ibid., 67-68.

512 The Journalof AmericanHistory September2002

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DammingAfghanistan: in a BufferState

Modernization 513

history it was to the Soviet invasion of the 1980s or the earlier"greatgame" that

ended with the British Empire'sdeparturefrom South Asia in 1947. There was a

silence about the three decadesin between. During that time, Afghanistanwas aptly

called an "economicKorea,"divided between the Soviet Union in the north and the

United Statesin the south.2In the 1950s and 1960s, the United Statesmade south-

ern Afghanistana showcaseof nation building with a dazzlingproject to "reclaim"

and modernize a swath of territorycomprising roughly half the country. The Hel-

mand venture is worth rememberingtoday as a precedent for renewed efforts to

rebuildAfghanistan,but it was also part of a largerproject-alternately called devel-

opment, nation building, or modernization-that deployed science and expertiseto

reconstructthe entire postcolonialworld.

When PresidentHarryS. Trumanannounced Point IV, a "bold new program...

for the improvement . . . of underdeveloped areas," in January 1949, the global

responsewas startling.Truman "hit the jackpot of the world'spolitical emotions,"

Fortunenoted. National delegationslined up to receiveassistancethat a few yearsear-

lier would have been seen as a colonial intrusion.Development insertedinto interna-

tional relations a new problematic and a new concept of time, asserting that all

nations followed a common historicalpath and that those in the lead had a moral

duty to those who followed. "We must franklyrecognize,"a State Department offi-

cial observedin 1953, "thatthe hands of the clock of historyareset at differenthours

in different parts of the world." Leaders of newly independent states, such as

Mohammad Zahir Shah of Afghanistan and JawaharlalNehru of India, accepted

these terms, merging their own governmentalmandatesinto the stream of nations

moving toward modernity. Development was not simply the best but the only

course. "Thereis only one-way trafficin Time,"Nehru observed.3

Aided by social science theory,developmentcame into its own by the mid-1950s

both as a policy ideology in the United Statesand as a global discoursefor assigning

obligations and entitlements among rich and poor nations.4Nationalism and mod-

ernization held equal place in the postcolonial creed. As EdwardShils observed in

2

Louis Dupree, "Afghanistan,the Canny Neutral,"Nation, Sept. 21, 1964, p. 135.

3 Harry S. Truman,inauguraladdress,Jan. 20, 1949, in PublicPapersof the Presidents,HarryS. Truman,1949:

Containingthe PublicMessages,Speeches,and Statementsof the President,January1 to December31, 1949 (Washing-

ton, 1964), 114-15. "Point IV,"Fortune(Feb. 1950), 88. Henry A. Byroade,"The World'sColonies and Ex-Col-

onies: A Challenge to America,"Departmentof State Bulletin, Nov. 16, 1953, p. 655. JawaharlalNehru, The

DiscoveryofIndia (New York, 1960), 393.

4 On the history of development ideas, see H. W. Arndt, EconomicDevelopment:The Historyof an Idea (Chi-

cago, 1987); Gerald M. Meier and Dudley Seers, eds., Pioneersin Development(New York, 1984); M. P. Cowen

and R. W Shenton, Doctrinesof Development(New York, 1996); Nick Cullather, "Development Doctrine and

ModernizationTheory,"in EncyclopediaofAmericanForeignPolicy,ed. AlexanderDeConde, RichardDean Burns,

and FredrikLogevall (3 vols., New York, 2002), I, 477-91. On development as discourse, see Arturo Escobar,

EncounteringDevelopment:TheMaking and Unmakingof the Third World(Princeton, 1995); and Tim Mitchell,

"America'sEgypt: Discourse of the Development Industry,"Middle East Report,169 (March-April 1991), 18-34.

On the social sciences and modernization theory, see Robert A. Packenham,LiberalAmericaand the Third World:

Political DevelopmentIdeas in ForeignAid and Social Science(Princeton, 1973); Nils Gilman, "Pavingthe World

with Good Intentions: The Genesis of ModernizationTheory, 1945-1965" (Ph.D. diss., Universityof California,

Berkeley,2001); FrederickCooper and Randall Packard,eds., InternationalDevelopmentand the Social Sciences:

Essayson the Historyand Politics of Knowledge(Berkeley, 1997); and Christopher Simpson, ed., Universitiesand

Empire:Money,Politics,and the Social Sciencesduring the Cold War(New York, 1998).

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

514 The Journalof AmericanHistory September2002

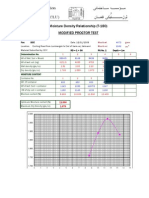

Pan American Airlines technician Richard Frisius instructs Afghan pilot candidates in

1960. U.S. development aid through the Helmand Authority helped establish the

national airline, Ariana, and build a modern airport at Kandahar.The airport is today

the U.S. Army'sforwardbase in Afghanistan. Reprintedfrom U.S. OperationsMission to

Afghanistan,AfghanistanBuilds on an Ancient Civilization, 1960.

1960, nearlyeverystate pressedfor policies "thatwill bring them well within the cir-

cle of modernity."But nation-buildingschemes,even successfulones, rarelyunfolded

quietly.The struggles,often subtle and indirect,over dam projects,land reforms,and

planned cities generallyconcernedthe meaningof development,the persons,author-

ities, and idealsthat would be associatedwith the spectacleof progress.To modernize

was to lay claim to the future and the past, to define identitiesand values that would

survive to guide the nation on its journey forward.It was this double sense of time,

according to Clifford Geertz, that gave "new-statenationalism its peculiar air of

being at once hell-bent toward modernity and morally outraged by its manifesta-

tions."5

Vulnerableto shifts in policy, funding, or theoreticalfashion, Cold War-eradevel-

opment schemes sufferedfrom deficienciesreasonablyattributedto their piecemeal

approachand shortagesof commitment, resources,or time. Such failures,JamesFer-

guson has observed,only reinforcedthe paradigm,as modernizationtheory supplied

the necessary explanations while new policy furnished solutions.6 The Helmand

5Edward Shils, "PoliticalDevelopment in the New States,"ComparativeStudiesin Societyand History,2 (April

1960), 265. Clifford Geertz, TheInterpretationof Cultures(New York, 1973), 243.

6 James Ferguson, The Anti-Politics Machine: Development,Depoliticization, and BureaucraticPower in the

Third World(New York, 1990), 254-56; see also Michael E. Latham, Modernizationas Ideology:AmericanSocial

Scienceand 'Nation Building"in the KennedyEra (Chapel Hill, 2000), 181.

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DammingAfghanistan: in a BufferState

Modernization 515

schemehad no suchexcuse.It cameunderAmericansupervisionin 1946 and con-

tinueduntil the departureof the last reclamation expertin 1979, outlastingall the

theoriesandrationaleson whichit wasbased.It waslavishlyfundedby U.S. foreign

aid,multilateral loans,andtheAfghangovernment, andit wasthe oppositeof piece-

meal.It wasan "integrated" developmentscheme,with education,industry,agricul-

ture,medicine,andmarketingundera singlecontrollingauthority.Nationbuilding

did not failin Afghanistanforwantof money,time,or imagination.In the Helmand

Valley,the enginesand dreamsof modernization rantheirfull course,spoolingout

acrossthe desertuntiltheyhit limitsof physics,culture,andhistory.

Plannerspresentedthe Helmandprojectas appliedscience,as a rationalization of

natureandsocialorder,buttheyalsotrafficked in dreams.Becauseof its scaleandlon-

gevity,the Helmandventureassumedrolesin a successionof modernizingmyths.

Modernization, MichaelLathamnotes,demandeda "projection of Americaniden-

ExportinganAmericanmodelof progress

tity."7 requiredcontinualredefinition of the

sourcesof Americangreatness andrenewedeffortsto plantits uniquecharacteristics in

foreignlandscapes. The New Deal,the New Look,andthe New Frontiereachrevised

thestakesandsymbolismof development, andeachhadto interlacethesefilamentsof

meaningwith the webs of significanceAfghanswove aroundthe project.Within

Afghanistan's government, the impulseto modernizewentbackto the earlytwentieth

centurywhentribalandethnicloyaltieswerereformedas a nationalidentity.Planting

a moderncitynextto the colossalruinsof QalaBistwasa calculated gestureasserting

an imaginedline of successionfrom the eleventh-and twelfth-century Ghaznavid

dynastyto the royalfamilypresidingin Kabul.The Helmandprojectsymbolizedthe

transformation of thenation,representingthelegitimacyof themonarchy, the expan-

sion of statepower,and the destinyof the Pashtunrace.Everydevelopmentscheme

involvesrepresentations of this kind,and a complexprojectcan accommodate over-

lappingsetsof symbolicmeaningsthatjustifyandsustainit, evenin failure.

The AccidentalNation

Afghanistan,at its origin,wasan emptyspaceon the mapthatwasnot Persian,not

Russian,not British,"apurelyaccidentalgeographic unit,"accordingto LordGeorge

N. Curzon,who put the finishingtoucheson its silhouette.Boththe monarchyand

the nationemergedfromstrategiesBritainusedto pacifythe Pashtunpeoplesalong

India'snorthwestfrontierin the last half of the nineteenthcentury.Consistingof

nomadic,seminomadic,and settled communitieswith no common languageor

ancestry,Pashtuns(Pathansin Hindustani)madeup for colonialofficialsa single

racialgrouping.8Theyoccupieda strategically vitalregionstretchingfromthesouth-

ernslopesof theHinduKushrangethroughthe northernIndusValleyinto Kashmir.

I Michael Latham, "Introduction:Modernization

Theory, InternationalHistory, and the Global Cold War,"in

StagingGrowth,ed. David Engermanet al. (Boston, forthcoming, 2002); Akhil Gupta, PostcolonialDevelopments:

Agriculturein the Making ofModern India (Durham, 1998), 40-42.

8 Lord George N. Curzon quoted in Cuthbert Collin Davies, The Problemof the North-WestFrontier,1890-

1908 (Cambridge, 1932), 153. Defining the Pashtun threat in the absence of reliable linguistic or pigmentary

markerswas a vital strategicand scientific undertaking.A summary of the early ethnographicwork is contained in

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

516 The Journalof AmericanHistory September2002

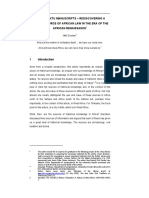

60 64 68 72 76

38

N U. S. S. R. 38

OMESHED N

( ~ ~~ ~~~~~~~ Tash

~~oTd.a~qn

h88 KaEGIIBDIOd /S ,

X

. ODoulVIGDd

rmoi-ba

j omn 0 869~~~~4

Pul-l

S~hIdnKhumri ILA R imw

%

B0l oh~b 4800 )I,

I 6 4 INA

A N 0 SHOWINGChbrikr

l4j i |

HERAT E R .'? 6@

34 1(7 A P

K3 KABUL 8F HEL N D A E F N R

TV t \^ Ls~~~~bo4;Pd~~~d g

0

o

i\o 1188

\

~ooIZa

ENGINRAN

Noel

NI

AFGE HANISTAN

I R AN ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ LORALAI~~~~~~~~AJKI EIEVI

r844 4Yse005/A T-OM PN

ACCOVM RPOTN

Stretching acoss he~~ souther hafo fhnsath emn alydvlopmeIYnt was

TUOREGIANEEINGOMANY

mand Valley,Afghanistan, 1956.~~~~~~~~~Gazn

IRAN SHOWING~.4WAHIGOND..NOEME 15

separatesAfghanistan

60 andPakistan.

64O68 Plt A K893 SsitfTrnir

n L72 the

AfNoDEVELOPMENTwOeINDAY AF

u dLnte120ml oa

split~~~~~~~~~~~40

it

in~I0.

hal

byINT Muvyn

h

onaytaP

artopongraphcridgeline

Strtchingracross thgeesothern haulfof be

sothatn could Afhedanitan

Afhedanitanstheongpoints

theHelmand balockingvkeypmontwain

Valeykidevelopmentwasn

passies. triba

Byabisectiangra

allies Pakbistantandgra fromahomietnlansende therseasona

Sovietnluesnce Rheprne migoration

fraoma Reporation reeoutestof

Deeopment tHreeml-

of

threeml-

Afghanistan

seonparates Pa

andlowed . lotd

Psian 1893athledsient o oloan ed

ferNteern

folowe herdsan

lionpasatorlstAghnstwho PoftPersianfa3t-tied "shepientfcfotween"lowlandwad

John Cowles Prichard,Researches into the PhysicalHistoryofMankind (4 vols., London, 1844), IV, 81-9 1; see also

H. G. Raverty,"The Independent Afghan or PatanTribes,"ImperialandAsiatic QuarterlyReviewand Orientaland

Colonial Review,7 (1894), 312-26; R. C. Temple, "Remarkson the Afghans Found along the Route of the Tal

Chotiali Field Force in the Spring of 1879,"Journalof theAsiatic Societyof Bengal,49 (no. 1, 1880), 91-106; and

H. W. Bellew, The Racesof Afghanistan:Being a BriefAccount of the Principal Nations Inhabiting That Country

(Calcutta, 1880). See also Conrad Schetter, "The Chimera of Ethnicity in Afghanistan,"Neue ZfircherZeitung,

Oct. 31, 2001 <http://www.nzz.ch/english/background/2001/10/31Lafghanistan.html>(Nov. 9, 2001). On the

importance of ethnology to the colonial mission, see Gyan Prakash,AnotherReason:Scienceand the Imaginationof

ModernIndia (Princeton, 1999), 26-30.

9 George McMunn, Afghanistanfrom Darius to Amanullah (London, 1929), 225-28; SultanaAfroz, "Afghani-

stan in U.S.-Pakistan Relations, 1947-1960," CentralAsian Survey,8 (no. 2, 1989), 133.

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DammingAfghanistan: in a BufferState

Modernization 517

uplandgrazingareas,the DurandLinerestrictedPashtunautonomyand facilitated

newformsof indirectinfluenceoverpeopleson bothsidesof it.10

Ratherthandemarcating the spatiallimit of Britishsovereignty,

the DurandLine

markeda divisionbetweentypesof imperialcontrol.On the Indiaside, a smaller

Pashtunpopulation,the "assured clans,"couldbe co-optedand deployedas a proxy

armyagainstPashtunson the Afghanside,precludingthe emergenceof a regimein

Kabulhostileto Britishinterests.The Mohammadzai-theclanof ZahirShah,ruler

of Afghanistan from1933 to 1973-was sucha subalternforce,benefitingfromBrit-

ish powerwithoutbeingfullyconstrainedby it."1Straddlingthe KhyberPass,they

usedsubsidiesandarmsto overwhelmtheirrivalson theAfghanside.Thisvarietyof

indirectrule,knownas the ForwardPolicy,keptAfghanistanfirmlyunderBritish

influenceforthe firsthalfof the twentiethcentury.'2

The DurandLinecomplementeda culturalstrategyof pacificationknownas the

Pathan(Pashtun)Renaissance,throughwhich colonialagentsalignedtheir own

interestswith thoseof theirtribalallies.Cultivatinga Pashtunidentityas a unitary

Cpure" racein contrastto the "mixed"Tajiks,Baluchis,Hazaras,and otherswith

whom theyweremingled,colonialofficialsinventedthe reputationof the Pashtuns

as a warriorcaste.They were"ourchaps,"naturalrulers,the equalsof the British.

"You're whitepeople,sons of Alexander,and not like common,blackMohammed-

ans,"the title characterof RudyardKipling'sTheMan WhoWouldBe King(1891)

explainedto theAfghans.Pashtunswereentitledto subsidies,to rankin the Indian

army,and to a directrelationshipto the Crown.Schoolinginternalizedthe racial

taxonomy,supplantingallegiancesto village,family,andclanwhilelinkingPashtun

identitywith modernization.Edwardesand Islamiacolleges,foundedin Peshawar

in the earlytwentiethcentury,inculcateda consciousnessof Pashtunnationhood

and suggested"theplacewhichthe Pathanmightfill in the developmentof a sub-

continent."An awareness of racedistinguishedthe literatefew fromthe vastmajor-

ity of uneducatedAfghans,who wereunableto discriminatebetweenethnographic

types.13

10 Davies, Problem of the North-WestFrontier, 162-63; C. L. Sulzberger,"Nomads Swarming over Khyber

Pass,"New YorkTimes,April 24, 1950, p. 6. On the British construction of "Afghanistan,"see Nigel J. R. Allan,

"Defining Place and People in Afghanistan,"Post-SovietGeographyand Economics,41 (no. 8, 2001), 545-60.

" W K. Fraser-Tytler,Afghanistan:A Study of Political Developmentsin Centraland SouthernAsia (London,

1953), 332. British officials located the Mohammadzai'shomeland in Hastnagar,now in Pakistan:India Army,

General Staff,A Dictionaryofthe Pathan Tribes(Calcutta, 1910), 34.

12 J. G. Elliott, TheFrontier,1839-1947 (London, 1968), 53. Afghan nationalistsbelieved Britain had secretly

annexed Afghanistanby supporting the Mohammadzai,leading the constitutionalistYoungAfghan movement to

assassinateboth the king, Nadir Shah, and his brother, Mohammad Aziz, who was ambassadorto Germany. In

1933 an attempt was also made on the British embassy. Hasan Kakar,"Trendsin Modern Afghan History,"in

Afghanistanin the 1970s, ed. Louis Dupree and Linette Albert (New York, 1974), 31; McMunn, Afghanistanfrom

Darius to Amanullah, 228.

13 Akbar S. Ahmend, "An Aspect of the Colonial Encounter in the North-West Frontier Province,"Asian

Affairs, 9 (Oct. 1978), 319-27. Rudyard Kipling, The Man Who WouldBe King (1891), in The One Volume

Kipling (New York, 1932), 735. Olaf Caroe, The Pathans,550 B.C.-A.D. 1957 (Karachi, 1958), 429-30. In 1962,

the anthropologist Louis Dupree tried a free association experiment on students at Kabul University using the

terms "Afghanistan,""United States,"etc. Students identified Afghanistan and the United States as "white"coun-

tries, Pakistanand India as "black-skinned."Louis Dupree, "LandlockedImages: Snap Responses to an Informal

Questionnaire,"AmericanUniversitiesField StaffReports,SouthAsia Series,6 (June 1962), 51-73.

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

518 TheJournalof AmericanHistory September

2002

As it was meant to, the sublimationof the Pashtunsreconfiguredpolitics on both

sides of the frontier.When Nadir Shah crossed the Durand Line and seized Kabul

from the Tajiksin 1929, he establisheda monarchy based on Pashtun nationalism

with overtonesof scientific racism.Comprisingless than half the Afghan population,

Pashtunsclaimed an entitlement based on their statusas an advancedrace, the bear-

ers of modernityand progress.14 PunitiveexpeditionsagainstTajiksin the north and

Hazarasin the south and west, in which German-madeaircraftsupportedmounted

troops, broke the autonomous power of these regions,opening them to Pashtunset-

tlement. Nadir Shah built a professionalarmy-new in Afghan tradition-of forty

thousandtroops,linked by kinship and personalloyaltyto the monarchyand trained

by Frenchand Germanadvisers.15 A systemof secularizedschools and a changeof the

national language from Dari, a Persian dialect, to Pashto demonstrated the new

regime'sdeterminationto bring Afghanistan'sungovernabletribes under the control

of a rationalized,centralstate.

For Nadir Shah and his son Zahir,who assumedthe throne afterhis father'sassas-

sination in 1933, political survivaldependedon enlargingand deepeningthe author-

ity of the state. To its new rulers, Afghanistanwas an unknown and dangerous

country.It had few roads,only six miles of rail (all of it in Kabul), and few internal

telegraphor phone lines. For most of the ten or twelve million Afghans (Afghanistan

has never completed a census), encountersof any kind with the centralgovernment

were rare and unpleasant.Laws were made and enforced in accordancewith local

custom and without referenceto the state; internaltaxes existed only on paper.Evi-

dence of royal authority-easily visible on Kabul streets patrolled by Prussian-hel-

meted palace guards-disappeared as rapidly as the pavement beneath a traveler

leavingthe city in any direction.There were no cadastralmaps, city plans, or housing

registries,an absencethat madeAfghanistanless legible,and thereforeless governable,

than countriesthat had been formallycolonized."6Modern states are able to govern

through manipulation of abstractions-unemployment, public opinion, literacy

rates,etc.-but in Afghanistaninterventionsof any kind, and the reactionsto them,

were brutally concrete. The prime minister, the king's uncle, on his infrequent

inspection tours of the countryside,traveledunderheavyguard.17

Zahir Shah sought help from Japanese,Italian, and German advisers,who laid

plans for a modern networkof communicationsand roads. In 1937 a German-built

radio tower in Kabul allowed instant links to remote villages and the outside world

14 Arnold Fletcher,Afghanistan:Highway of Conquest(Ithaca, 1965), 245. Alfred Janata, "Afghanistan:The

Ethnic Dimension," in The CulturalBasisofAfghanNationalism,ed. EwanW Anderson and Nancy Hatch Dupree

(New York, 1990), 62.

15 The campaign against the KuhestaniTajiksnorth of Kabul was particularlysevere. Prisonerswere executed

by being blown from the mouths of cannon. "ElevenAfghans Blown from Guns at Kabul,"New YorkTimes,April

6, 1930, p. 8; "AfghanRevolt Reported,"ibid., Nov. 21, 1932, p. 7; Vladimir Cervin, "Problemsin the Integra-

tion of the Afghan Nation," Middle EastJournal,6 (Autumn 1952), 407; BhalwantBhaneja,Afghanistan:Political

Modernizationof a Mountain Kingdom(New Delhi, 1973), 20.

16 Louis Dupree, "ANote on Afghanistan,"AmericanUniversities Field Staff Reports,SouthAsia Series,4 (Aug.

1960), 13. Afghanistan was the type of "illegible"state described by James C. Scott, Seeing like a State (New

Haven, 1998), 77-78.

17 Rosita Forbes,"AfghanDictator,"LiteraryDigest, Oct. 16, 1937, P. 29.

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DammingAfghanistan: in a BufferState

Modernization 519

for the firsttime.Througha nationalbankandstatecartels,the governmentsuper-

viseda cautiousand tightlycontrolledeconomicmodernization. Germanengineers

built textilemills, powerplants,and carpetand furniturefactoriesto be run by

monopoliesunderroyallicense.'8Taxcodesand statetradingfirmsbeganto bring

lawlesssectors,such as stock raisingand trading,within reachof accountantsand

assessors in Kabul.Theseeffortsmetwithsporadic-andoccasionally bloody-resis-

the in

tance,but regimepersisted slowly,firmly,laying "thebarren politicsof abstrac-

tion andprinciple" over"thewarm,cruelpoliticsof the heart."'9

DuringWorldWarII the UnitedStatesreplacedGermanyas the externalpartner

in the young king'splans.The Holocaustand submarinewarfarecausedAfghani-

stan'sexternaltradeto undergoa suddenandadvantageous reorientation.One of the

country'schiefexportswaskarakul,the peltof the Persianfat-tailedsheepconverted

in the handsof skilledfurriersinto the glossyblackfurknownas astrakhan, karacul,

or Persianlamb. The formercentersof fur making,Leipzig,London,and Paris,

closeddown duringthe waryears,and the industrymovedin its entiretyto New

York.From1942 throughthe 1970s,New Yorkfurriersconsumednearlythe entire

Afghanexport,two and a half millionskinsa year,which resoldas lustrousblack

coatsandhatsrangingin pricefrom$400 to $3,500.A tinyfractionof the retailrev-

enue went back to Afghanistan,but the fractionsadded up. The government

employedexchangeratemanipulations to exactan effectivetax rateof over50 per-

cent on karakul,makingit the country'smostlucrativesourceof exchangeaswellas

revenue.Afghanistan endedWorldWarII with $100 millionin reserves,and,in the

midst of the postwar"dollargap"crisisin internationalliquidity,Afghanistanwas

favoredwitha smallbutsteadysourceof dollarearnings.20

The collapseof the BritishEmpirecreateda chancefor Pashtunreunification and

lent new significanceto the modernization project.Fromthe vantageof Kabul,the

partitionof Indiain 1947 endedwhateverjustificationthe DurandLinehad once

had.A Pashtunseparatistmovementemergedin Peshawar and Kashmir,and,with

the encouragement of India,ZahirShahproposedthe creationof an ethnicstate-

Pushtunistan-consistingof most of northernPakistan,which would give the

assuredclansan option to mergewith Kabulat somefuturedate.It wasa hopeless

proposal-the frontierwas internationally recognized-but the king stuck to it

ratherthan allowPakistanto inheritthe decisiveinstrumentsand influenceof the

ForwardPolicy.The assuredclansrepresenteda continuingthreatto the Afghan

state.After 1947, membersof the royalfamilyspokeof buildingin Afghanistana

secure,prosperous baseforthe recoveryof Pashtunlands.21

18

Donald N. Wilber, ed., Afghanistan(New Haven, 1956), 238-43.

19LawrenceDurrell, ProsperosCell (New York, 1996), 72.

20

"KarakulSheep,"Life,July 16, 1945, pp. 65-68; Peter G. Franck, "Problemsof Economic Development in

Afghanistan,"Middle EastJournal, 3 (July 1949), 302. Abdul Haj Kayoumy, "Monopoly Pricing of Afghan Kara-

kul in International Markets,"Journal of Political Economy 77 (March-April 1969), 219-37; Ali Mohammed,

"Karakulas the Most ImportantArticle of Afghan Trade,"Afghanistan(Kabul), 4 (Dec. 1949), 48-53. The 'dollar

gap"was a global shortage of dollar reservesand dollar earnings that threatened to stifle economic recoveryand

internationaltrade. See William S. Borden, ThePacificAlliance: UnitedStatesForeignEconomicPolicyandJapanese

TradeRecovery,1947-1955 (Madison, 1984).

21

Najibullah Khan, "SpeechDelivered over the Radio,"Afghanistan(Kabul), 3 (April-June 1948), 13.

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

520 TheJournalof AmericanHistory September

2002

Over the next two decades the Pushtunistancontroversydrew Afghanistaninto

the Cold War. U.S. diplomats dismissed it as fantasy,but to the Afghan monarchy

Pushtunistanwas as solid as France.A visitor in 1954 found governmentoffices in

Kabul hung with maps on which the "narrow,wriggly object" plainly appeared,

"wedgedin betweenAfghanistanon one flank, and the remainsof West Pakistanon

the other."The dispute periodicallyturned hot, with reciprocalsackingof embassies

and border incidents that graduallyconverted the Durand Line into the kind of

politico-geographicfeaturethat typified the Cold War,an impassableboundary.The

movement of goods acrossthe frontierwas tightly restricted,and in 1962 Pakistan

closed the passes to migration, terminatingthe seasonal movement of the herds.22

From the mid-1950s until the end of the Soviet occupation, Afghan exports and

imports moved almost exclusively through the Soviet Union, which discounted

freightratesto encouragethe dependency.23

In the immediateaftermathof WorldWarII, however,the SovietUnion was preoc-

cupied with internalreconstruction,and Afghanistanlooked to the United Statesfor

help in consolidatinga centralizedstatethat could assumeresponsibilityfor the public

welfare.24Through its developmentprograms,the monarchyassumeda relationship

of trusteeshipover the nation, presentingthe king as retainingcustody of the state

duringa dangeroustransitionalperiod but readyto relinquishpoweronce modernity

was achieved.Official terminologycoupled underdevelopmentand Afghan identity.

"Afghanistanis a backwardcountry,"insistedMohammedDaoud, the king'sbrother-

in-law, cousin, and prime minister. "We must do something about it or die as a

nation."25Large-scaledevelopment projects,visible signs of national energy,would

stake a claim to the future for the Pashtunsand to the present for the royal family.

One such schemeparticularlyappealedto the king;he wanted to build a dam.

A TVAfor the Hindu Kush

Nothing becomes antiquatedfasterthan symbols of the future, and it is difficult, at

only fifty years remove, to envision the hold concrete dams once had on the global

imagination.In the mid-twentiethcentury,the austerelines of the Hoover Dam and

its radiatingspans of high-tension wire inscribed federal power on the American

landscape.Vladimir Lenin famously remarkedthat Communism was Soviet power

plus electrification,an equationcapturedby the David Lean film Dr. Zhivago(1965)

in the image of water surging, as a kind of redemption, from the spillway of an

immense Soviet dam. In 1954, standing at the Bhakra-Nangalcanal, Nehru

describeddams as the temples of modern India. "'Whichplace can be greaterthan

22

Ian Stephens, HornedMoon (Bloomington, 1955), 263. See the series of reports by Louis Dupree, "'Push-

tunistan':The Problem and Its LargerImplications,"American UniversitiesField Staff Reports,SouthAsia Series,5

(Nov.-Dec. 1961), 19-51.

23 S. M. M. Quereshi, "Pakhtunistan: The FrontierDispute between Afghanistanand Pakistan,"PacificAffairs,

39 (Spring-Summer 1966), 99-144; on the U.S. position, see Dennis Kux, The UnitedStatesand Pakistan,1947-

2000 (Baltimore,2000), 42-43, 78; and Afroz, "Afghanistanin U.S.-PakistanRelations,"138-40.

24

Paul Overby,Holy Blood:An Inside Viewof theAfghan War(Westport, 1993), 30.

25

Louis Dupree, "AnInformalTalk with Prime Minister Daoud," Sept. 13, 1959, American UniversitiesField

StaffReports,SouthAsia Series,3 (Sept. 1959), 18.

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Damming Afghanistan:Modernizationin a BufferState 521

Morrison Knudsen engineers surveyed and built the

Helmand Valley project's major works between 1946

and 1960. The Soviet pressdescribedthe company as "a

kind of training centre where young Afghans are

moulded to [an] American pattern. Reprintedfrom

Collier's,Aug. 2, 1952.

this,"he declared,"thisBhakra-Nangal,where thousandsof men have worked, have

shed their blood and sweat, and laid down their lives as well? . .. When we see big

works, our staturegrows with them, and our minds open out a little."2 For Nehru,

for Zahir Shah, for China today,the greatblankwall of a dam was a screenon which

they would projectthe future.

Dams also symbolized the sacrificeof the individual to the greatergood of the

state. A dam project allows, even requires,a state to appropriateand redistribute

land, plan factoriesand economies, tell people what to make and grow, design and

build new housing, roads,schools, and centersof commerce.Tour guides are fond of

telling about the worker (or workers)accidentallyentombed in dams, and construc-

tion of these vast works customarilyrequireshuge, unnamed sacrifices.To displace

thousands from ancestralhomes and farms, bulldoze graveyardsand mosques, and

eraseall traceof memory and historyfrom the land is a processfamiliarto us today as

ethnic cleansing. But when done in conjunction with dam construction, it is called

land reclamationand can be justified even in democraticsystems by the calculus of

development. India'sinterior minister,MorarjiDesai, told a public gatheringat the

unfinished Pong Dam in 1961 that "wewill requestyou to move from your houses

26JawaharlalNehru, "Speechat the Opening of the Nangal Canal,"July 8, 1954, in JawaharlalNehru'sSpeeches

(4 vols., Delhi, 1958), III, 353.

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

522 TheJournalof AmericanHistory 2002

September

afterthe dam comes up. If you move, it will be good. Otherwisewe shall releasethe

watersand drownyou all."27

A dam-building project would vastly expand and intensify the authority that

could be exercisedby the centralgovernmentat Kabul.Remakingand regulatingthe

physicalenvironmentof an entire regionwould, for the first time, translateAfghani-

stan into the legible inventoriesof materialand human resourcesin the manner of

modern states. In 1946, using its karakulrevenue,the Afghan governmenthired the

largestAmericanheavy engineeringfirm, Morrison Knudsen, Inc., of Boise, Idaho,

to build a dam. MorrisonKnudsen, builder of the Hoover Dam, the San Francisco

Bay Bridge,and later the launch complex at Cape Canaveral,specializedin symbols

of the future.The firm operatedall overthe world, boringtunnels throughthe Andes

in Peru, laying airfieldsin Turkey.Its engineers,who called themselvesEmkayans,

would be drawing up specifications for a complex of dams in the gorges of the

YangtzeRiver in 1949 when Mao Zedong's People'sLiberationArmy drove them

out.28The firm set up shop in an old Moghul palace outside Kandaharand began

surveyingthe Helmand Valley.

The Helmand and Arghandabriversconstitute Afghanistan'slargestriversystem,

draininga watershedcoveringhalf the country.Originatingin the Hindu Kush a few

miles from Kabul,the Helmand travelsthroughuplanddells thick with orchardsand

vineyards before merging with the Arghandabtwenty-five miles from Kandahar,

turning west acrossthe arid plain of Registanand emptying into the Sistan marshes

of Iran. The valley was reputedly the site of a vast irrigationworks destroyed by

Genghis Khan in the thirteenthcentury.The entire areais dry,catchingtwo to three

inches of rain a year.Consequently,riverflows fluctuateunpredictablywithin a wide

range,varyingfrom 2,000 to 60,000 cubic feet per second.29Beforebeginning, Mor-

rison Knudsenhad to createan infrastructureof roadsand bridgesto allow the move-

ment of equipment.Typically,they would also conduct extensivestudies on soils and

drainage,but the companyand the Afghangovernmentconvinced themselvesthat in

this case it was not necessary,that "evena 20 percent marginof error. .. could not

detractfrom the project'sintrinsicvalue."30

The promise of dams is that they are a renewableresource,furnishingpower and

waterindefinitelyand with little effortonce the projectis complete, but dam projects

aresubjectto ecologicalconstraintsthat are often more severeoutside of the temper-

ate zone. Siltation, which now threatensmany New Deal-era dams, advancesmore

quicklyin aridand tropicalclimates.Canalirrigationinvolvesa specialset of hazards.

ArundhatiRoy, the voice of India'santidammovement, explainsthat "perennialirri-

gation does to soil roughlywhat anabolicsteroidsdo to the human body,"stimulat-

27 On the political uses to which dams have been put, see Ann Danaiya Usher, Dams as Aid: A PoliticalAnat-

omy of NordicDevelopmentThinking(New York, 1997). MorarjiDesai quoted in Arundhati Roy, The Costof Liv-

ing (New York, 1999), 13.

28 Robert De Roos, "He Changes the Face of the Earth,"Colliers,Aug. 2, 1952, pp. 28-30.

29 A. H. H. Abidi, "Irano-AfghanDispute over the Helmand Waters,"InternationalStudies(New Delhi), 16

(July 1977), 358-59; Fraser-Tytler, Afghanistan,8.

30 Aloys Arthur Michel, The Kabul, Kunduz, and Helmand Valleys and the National EconomyofAfghanistan:A

Studyof RegionalResources and the ComparativeAdvantagesof Development(Washington, 1959), 153.

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DammingAfghanistan:

Modernization

in a BufferState 523

ing ordinaryearth to produce multiple crops in the firstyearswhile slowly rendering

the soil infertile.31Largereservoirsraise the water table in the surroundingarea, a

problem worsened by extensive irrigation.Waterloggingitself can destroy harvests,

but it producesmore permanentdamage, too. In waterloggedsoils, capillaryaction

pulls soluble salts and alkaliesto the surface,leading to desertification.Earlyreports

warnedthat the Helmand Valleywas vulnerable,that it had gravellysubsoilsand salt

deposits.The Emkayansknew Middle Easternriverswere often unsuited to extensive

irrigationschemes. But these apprehensions'"impactwas minimized by one or both

parties."32From the start, the Helmand projectwas primarilyabout nationalprestige

and only secondarilyabout the social benefitsof increasingagriculturalproductivity.

Signs of trouble appearedalmost immediately.Even when only half completed,

the first dam, a small diversion dam at the mouth of the Boghra canal, raised the

water table to within a few inches of the surfaceof the ground.A snowy crust of salt

could be seen in areasaround the reservoir.In 1949, the engineersand the govern-

ment faced a decision. Tearingdown the dam would have resultedin a loss of face for

the monarchy and Morrison Knudsen, but from an engineering standpoint the

projectcould no longer be justified.The necessaryreconsiderationnever took place,

however,becauseit was at this moment that the unlucky Boghraworkswas enfolded

into the global projectof development.

Truman'sPoint IV addressreconfiguredthe relationshipbetween the United States

and newly independentnations. The confrontationbetween colonizerand colonized,

rich and poor, was with a rhetoricalgesturereplacedby a world order in which all

nationswere either developedor developing.The presidentexplicitlylinked develop-

ment to Americanstrategicand economic objectives.Povertywas a threatnot just to

the poor but to their richerneighbors,he argued,and alleviatingmiserywould assure

a generalprosperity,lessening the chances of war.33But the "triumphantaction"of

development supersededthe merely ideological conflict of the Cold War:Commu-

nism and capitalismwere competing carriersbound for the same destination.Devel-

opment justified interventions on a grand scale and made obedience to foreign

technicians the duty of every responsible government. Afghanistan-solvent,

untouched by the recent war, and able to hire technicianswhen it needed them-

suddenly became "underdeveloped" and, owing to its position borderingthe Soviet

Union, the likely recipient of substantialassistance.Point IV's technical aid could

take many forms-clinics, schools, new livestock breeds, assays for minerals and

31 Scientists believe the ecological effects of large dams may include global climate change, seismic distur-

bances, and a quickening of the earth'srotation; for an inventory of environmental effects, see Egil Skofteland,

FreshwaterResources: EnvironmentalEducationModule (Paris, 1995); FranceBequette, "LargeDams," UNESCOCou-

rier,50 (March 1997), 44-46; Robert S. Divine, "The Troublewith Dams,"AtlanticMonthly(Aug. 1995), 64-74;

and PeterColes, "LargeDams-The End of an Era,"UNESCOCourier,53 (April2000), 10-11. Roy, Costof Living,

68.

32 VandanaShiva, The Violenceof the GreenRevolution(London, 1997), 121-39. Michel, Kabul, Kunduz, and

Helmand Valleysand the National EconomyofAfghanistan,152-53.

33 Gilbert Rist, TheHistoryof Development: From WesternOriginsto GlobalFaith, trans. PatrickCamiller (New

York, 1997), 70-75. Harry S. Truman, "Remarksto the American Society of Civil Engineers,"Nov. 2, 1949, Pub-

lic Papersof the Presidents,HarryS. Truman,1949, 547.

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

524 TheJournalof AmericanHistory September

2002

petroleum-but the uncompleted Boghra works was an invitation to something

grander,a reproductionof an Americandevelopmentaltriumph.

When Trumanthought of aid, he thought of dams, specificallyof the Tennessee

ValleyAuthority(WVA),the complexof dams on the TennesseeRiverthat transformed

the economy of the upper South. "ATVA in the YangtzeValleyand the Danube,"he

proposedto the TWAs director,David Lilienthal;"Thesethings can be done and don't

let anybodytell you different.When they happen,when millions and millions of peo-

ple are no longer hungryand pushed and harassed,then the causesof war will be less

by that much."Truman'sinternationalization of the TVA repositionedthe New Deal for

a McCarthyiteage. Dams were the Americanalternativeto Communist land reform,

ArthurM. Schlesingerarguedin The Vital Center.Insteadof a "cruderedistribution"

of land,Americanengineerscould create"wonderlandsof vegetationand power"from

the desert.The WVAwas "aweapon which, if properlyemployed,might outbid all the

socialruthlessnessof the Communistsfor the supportof the peoplesof Asia."34

The TVA had totemic significancefor Americanliberals,but in the diplomaticset-

ting it had the additionalfunction of redefiningpolitical conflict as a technicalprob-

lem. Britain'ssolution to Afghanistan'stribalwars had been to script feuds of blood,

honor, and faith within the linear logic of boundarycommissions, containing con-

flict within two-dimensionalspace. The United Statesset aside the maps and replot-

ted tribalenmities on hydrologiccharts.Resolutionbecamea matterof apportioning

cubic yardsof water and kilowatt-hoursof energy.Assurancesof inevitableprogress

furtherdisplacedconflict into the future;if all sides could be convinced that resource

flows would increase,problemswould vanish,in bureaucraticparlance,downstream.

Over the next two decadesthe United Stateswould propose riverauthorityschemes

as solutions to the most intractableinternationalconflicts: Palestine ("Waterfor

Peace")and the Kashmirdispute. In 1965, Lyndon B. Johnson famouslysuggesteda

Mekong RiverAuthorityas an alternativeto the Vietnam War.35

Afghanistanapplied for and receiveda $12 million Export-ImportBank loan for

the Helmand Valleyin 1950, the first of over $80 million over the next fifteen years.

Afghanistan'sloan requestcontaineda line for soil surveys,but the bank refusedit as

an unnecessaryexpense.Point IV supplied technicalsupport.36In 1952, the national

government created the Helmand Valley Authority-later the Helmand and

ArghandabValley Authority (HAvA)-removing 1,800 square miles of river valley

from local control and placing it under the jurisdiction of expert commissions in

34 Truman quoted in Alonzo L. Hamby, Liberalismand Its Challengers: FDR to Reagan(New York, 1985), 72-

73. Arthur M. Schlesinger, The Vital Center:ThePoliticsof Freedom(London, 1970), 233.

35 On the JordanValley project, see "PressConference:Statement by the Secretary,"

Departmentof State Bulle-

tin, Nov. 30, 1953, p. 750; and "EricJohnston Leaveson Mission to Near East,"ibid., Oct. 26, 1953, p. 553.

David Ekbladh, "AWorkshop for the World: Modernization as a Tool in U.S. Foreign Relations in Asia, 1914-

1974" (Ph.D. diss., Columbia University,2002); Lloyd C. Gardner,Pay Any Price:LyndonJohnsonand the Wars

for Vietnam(Chicago, 1995), 191.

36 C. L. Sulzberger,"AfghanShah Asks World Bank Loan,"New YorkTimes,April 20, 1950, p. 15; Cynthia

Clapp-Wincek and Emily Baldwin, The Helmand ValleyProjectin Afghanistan(Washington, 1983). On the soil

survey refusal,see Lloyd Baron, "SectorAnalysis-Helmand ArghandabValley Region: An Analysis,"typescript,

Feb. 1973, p. 15 (Libraryof Congress, Washington, D.C.). On Point IV, see Department of State, International

Cooperation Administration,Fact Sheet:Mutual Securityin Action,Afghanistan(Washington, 1959).

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Damming Afghanistan:Modernizationin a BufferState 525

The Arghandab Dam, 200 feethigh anda thirdof a milelong,washeraldedat its completionin

1952 as a majesticsymbolof technologicalprowess.Later,U.S. diplomatscomplainedthat the

Americanreputationhung on "astripof concrete."Reprintedfrom Missionto

U.S. Operations

Afghanistan

Afghanistan, Buildson anAncientCivilization,1960.

Kabul. The monarchypoured money into the project;a fifth of the centralgovern-

ment's total expenditureswent into HAVA in the 1950s and early 1960s. From 1946

on, the salariesof Morrison Knudsen'sadvisersand techniciansabsorbedan amount

equivalentto Afghanistan'stotal exports.Without adequatemechanismsfor tax col-

lection, the royal treasurypassedcosts on to agriculturalproducersthrough inflation

and the diversion of export revenue, offsetting any gains irrigation produced.37

Although it pulled in millions in internationalfunding, HAVA soaked up the small

reservesof individual farmersand may well have reduced the total national invest-

ment in agriculture.

HAVA supplemented the initial dam with a vast complex of dams. Two large

dams-the 200-foot-high ArghandabDam and the 320-foot-high KajakaiDam-

for storage and hydropowerwere supplementedby diversiondams, drainageworks,

and irrigationcanals. Reaching out from the reservoirswere three hundred miles of

concrete-linedcanals. Three of the longer canals, the Tarnak,Darweshan,and Sha-

malan, fed riparianlands alreadyintensivelycultivatedand irrigatedby an elaborate

system of tunnels, flumes, and canalsknown as juis. The new, wider canalsfurnished

an ampler and purportedlymore reliablewater source. The Zahir Shah Canal sup-

plied Kandaharwith water from the Arghandabreservoir,and two canals stretched

out into the desert to polders of reclaimeddesert:Marjaand Nad-i-Ali. Each exten-

sion of the project requiredmore land acquisition and displaced more people. To

remain flexible, the royal government and Morrison Knudsen kept the question of

who actuallyowned the land in abeyance.No system of titles was instituted, and the

bulk of the reclaimedland was farmedby tenants of MorrisonKnudsen, the govern-

ment, or contractorshired by the government.38

37Wilber, ed., Afghanistan,169. Emadi, State, Revolution,and Superpowersin Afghanistan,53. Nake M. Kam-

reny,Peacefil Competitionin Afghanistan:Americanand SovietModelsfor EconomicAid (Washington, 1969), 29.

38 Senate, U.S. Congress, Special Committee to Study the Foreign Aid Program, South Asia: Reporton U.S.

ForeignAssistancePrograms,85 Cong., 1 sess., March 1957, p. 23. Baron, "SectorAnalysis,"17, 31.

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

526 The Journalof AmericanHistory September2002

4~~~~~~~~~~~~~L

3 2~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~z

L

.1 L

1 ~~~~~

- ~~~~~i-4 Z

x 4-MO1C

C%

42 0

* 4~~~~~~C

Cr W~~~~

W UI

0 o ~~~~~~~~V)

0 I::$~~~~~~

UU

4~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~L

2 2~~~~~~~~WC

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DammingAfghanistan: in a BufferState

Modernization 527

The new systems magnified the problems encounteredat the Boghraworks and

added new ones. Waterloggingcreateda persistentweed problem.The storagedams

removed silt that once rejuvenatedfields downstream.Deposits of salt or gypsum

would erupt into long-distancecanalsand be carriedoff to deaden the soil of distant

fields. The Emkayanshad to contend with unpredictableflows triggeredby snow-

melt in the Hindu Kush. In 1957, floods nearly breacheddams in two places, and

water tables rose, salinating soils throughout the region. The reservoirsand large

canalsalso loweredthe watertemperature,makingplots that once held vineyardsand

orchardssuitableonly for growinggrain.39Aftera decadeof work, HAVAcould not set

a scheduleor a plan for completion. As its engineeringfailuresmounted, HAvA-s sym-

bolic weight in the Cold Warand in Afghanistan'sethnic politics steadilygrew.

Like the TvA, HAVAwas a multipurposeriverauthority.U.S. officialsdescribedit as

"a major social engineeringproject,"responsiblefor river development but also for

education, housing, health care, roads, communications, agriculturalresearchand

extension,and industrialdevelopmentin the valley.The U.S. ambassadorin Kabulin

1962 noted that, if successful,HAVAwould boost Afghanistan's"earningsof foreign

exchangeand, if properlydevised,could fosterthe growthof a strataof small holders

which would give the country more stability."This billiard-ballalignment of capital

accumulation,class formation, and political evolution was a core propositionof the

social science approachto modernizationthat was just making the leap from univer-

sity think tanks to centersof policy making.An uneasinessabout the massive,barely

understoodforces impelling two-thirdsof the world in simultaneousand irreversible

social movement-surging population growth, urbanization,the collapse of tradi-

tional authority-overshadowed policy toward "underdeveloped" areas.Moderniza-

tion theory offeredreassurancethat the techniquesof Point IV could disciplinethese

processesand turn them to the advantageof the United States. Development, the

economistsWaltW. Rostowand Max Millikanof the MassachusettsInstituteof Tech-

nology assuredthe cIA (CentralIntelligenceAgency) in 1954, could create"anenvi-

ronmentin which societieswhich directlyor indirectlymenaceourswill not evolve."40

A StrangeKind of Cold War

Following behavioralexplanationsof development, U.S. aid officials sought to ally

themselveswith tutelaryelites possessingthe transitionalpersonalitiesthat could gen-

erate nonviolent, nonrevolutionarychange. At first glance, the king and his retinue

appearedalmost ideallysuited. Educatedin Europeand the United States,royalgov-

ernment officials spoke in familiarterms of ways to engineer progress.Mohammed

Daoud presided as supreme technocrat. Educated (like the king) in Franceand at

39 Ira Moore Stevens and K. Tarzi,EconomicsofAgriculturalProductionin Helmand Valley, Afghanistan(Den-

ver, 1965), 30, 38.

40 Department of State, "Elements of U.S. Policy toward Afghanistan,"March 27, 1962, p. 17, Declassified

DocumentsReferenceSystem(microfiche, Carrollton Press, 1978), fiche 65B; see also Clapp-Wincekand Baldwin,

Helmand ValleyProject,5. Department of State, "Elementsof U.S. Policy towardAfghanistan,"17. Max Millikan

and Walt W. Rostow, "Notes on Foreign Economic Policy,"May 21, 1954, in Universitiesand Empire,ed. Simp-

son, 41.

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

528 TheJournalof AmericanHistory September

2002

English schools in Kabul, he became prime minister in 1953. "We membersof the

royalfamily,"he told the anthropologistLouis Dupree, "wereall trainedin the West

and have adopted Western ideas as our own.""4Since coming to power in 1953,

Daoud had acceleratedthe tempo of economic development,believing that without

rapidgrowthAfghanistanwould dissolveinto factionalismand be divided among its

neighbors.He was sure that U.S. and Soviet generositysprangfrom temporarycon-

ditions and that his governmenthad only a short time in which to take all it could.

To American officials, Afghan modernizersappearedtoo eager, too ready to jump

ahead without the necessary planning and information-gatheringsteps, and too

readyto take aid from any source. Daoud's receptivenessto Soviet and Chinese aid

was particularlytroubling.As Dupree put it, "Anation does not accept technology

without ideology.A machineor a dam is a productof a culture."42

Daoud's regime made no effort to disguise its chauvinism.Controlling positions

in government,the army,the police, and the educationalsystem were held by Pash-

tuns to such a degree that the appellationAfghan commonly referredonly to Pash-

tuns and not to the minorities who collectively constituted the majority.A U.S.

diplomat describedthe kingdom as a Soviet-style"policestate, where there is no free

press, no political parties,and where ruthlesssuppressionof minorities is the estab-

lished pattern."43But despite their favored status, Pashtuns revolted against the

Mohammadzaieight times between 1930 and 1960. Open violence betweenminori-

ties was less common than conflict that pitted clan autonomy againstcentralauthor-

ity. In 1956, Daoud welcomed Soviet military aid and advisers.His securityforces

kept orderwith a heavyhand, and, when mullahsin Kandaharagainled a movement

againstthe governmentin 1959, the army used tanks and MiGs to crush the rebel-

lion.44Daoud had broughtthe Cold War to Afghanistan.

To the Eisenhoweradministration,MorrisonKnudsen'soutpost in Kandaharwas

the scientific frontier of Americanpower in CentralAsia, guardingthe high passes

between risk and credibility.The company was "one of the chief influences which

maintainAfghan connections with the West,"Secretaryof StateJohn FosterDulles

believed."Itsdeparturewould createa vacuumwhich the Sovietswould be anxiousto

fill."He wanted to preserveAfghanistan'sbufferrole, but the perennialprovocations

along the Durand Line conjuredscenariosin Dulles'smind in which a Soviet-backed

Afghan army attacked U.S.-allied Pakistan-another Korea, this time beyond the

reachof U.S. air and navalpower.Daoud'sPashtunextremismled his governmentto

41 On the importance of psychology in modernization thinking, see Ellen Herman, The RomanceofAmerican

Psychology(Berkeley,1995), 136-48. Dupree, "InformalTalk with Prime Minister Daoud," 19.

42 Dupree, "Afghanistan, the Canny Neutral," 134-37. Dupree, "InformalTalk with Prime Minister Daoud,"

4; State Department, Bureauof Intelligence and Research,"BiographicReport:Visit of Afghanistan'sPrime Min-

ister SardarMohammad Daoud," June 13, 1958, DeclassifiedDocumentsReferenceSystem(microfiche, Carrollton

Press, 1996), fiche 11. National Security Council, "ProgressReport on South Asia,"July 24, 1957, ForeignRela-

tions of the UnitedStates,1955-1957 (25 vols., Washington, 1985-1990), XIII, 49.

43 Leon Poullada described it as "a government of, by, and for Pashtun":Leon Poullada, "The Search for

National Unity,"in Afghanistanin the 1970s, ed. Dupree and Albert, 40. Leon B. Poullada, ThePushtunRolein the

Afghan Political System(New York, 1970), 22. Angus C. Ward to Department of State, Dec. 14, 1955, Foreign

Relationsof the UnitedStates,1955-1957, VIII, 204.

4 Wilber, ed., Afghanistan,103. Poullada, "Searchfor National Unity,"44.

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

in a BufferState

Modernization

DammingAfghanistan: 529

welcome Soviet armswhile instigatingmob attackson Pakistaniconsulatesand bor-

der posts. In 1955, Dulles dissuadedPakistanfrom a plan to overthrowthe royalfam-

ily, while his brother,Allen, head of the cIA, suggestedusing againstDaoud the same

methods that had recentlyworked to depose Mohammed Mossadeq in Iran.45The

United Stateswanted to separatethe dual ambitionsof Pashtunnationalism,preserv-

ing Daoud'smodernizationdrivewhile disposingof the Pushtunistanissue.

The Helmand project offered a way to counter Soviet influence by giving Daoud

what he wanted, a Pashtunhomeland.As originallyenvisioned, HAVA would irrigate

enough new fertileland to settle eighteen to twenty thousandfamilieson fifteen-acre

farms.Workingwith Afghan officials,U.S. adviserslaunched a programto immobi-

lize the nomadic Pashtuns,whose migrationswere a source of friction with Paki-

stan.46To Americanand royal governmentofficials, this floating population and its

disregardfor laws, taxes,and borderssymbolizedthe country'sbackwardness.Settling

Pashtun nomads in a belt from Kabul to Kandaharwould create a secure political

base for the government and bring them within reach of modernizationprograms.

Diminishing the transborderflows would reduce smuggling and the periodic inci-

dents that inflamed the Pushtunistan issue. A complementarydam development

projectin the Indus Valley,also funded by the United States,settled Pashtunnomads

on the other side of the Durand Line.47

HAvAvs mandate included the social reconstructionof the region. Those seeking

land, as well as families alreadyoccupying ancestralplots, were requiredto apply to

HAVA for housing, water,and implements.In the late 1950s, HAVA began constructing

whole communities for transplantedpastoralistsin the Shamalan,Marja,and Nad-i-

Ali districts,while simultaneouslytryingto breakthe authorityof nomadic clan lead-

ers known as maliks. Maliks would lead their people, "Moses-like,to the promised

land,"accordingto a U.S. report. HAVA "alwaysinformed the new settlersthat they

could choose new village leaders,to be called wakil, if they so desired.None did."48

Resettled families would receive a pair of oxen, a grant of two thousand Afghanis,

and enough seed for the firstyear.To replacethe need for winter pastures,the United

Nations broughtin Swissexpertsto teach nomads to use long-handledscythesto cut

foragefor sheep from high plateaus.But even with the closing of the borderand the

attraction of subsidies and well-wateredhomesteads, it proved difficult to entice

Ghilzai Pashtun to become ordinaryfarmers.Freerand wealthierthan the peasants

whose lands they crossed,the nomads regardedtheir new Tajikand Hazaraneighbors

with contempt. This may have served Kabul's purposes, too. The government,

accordingto HafizullahEmadi, planned to "usethese new settlersas a death squadto

45 John Foster Dulles to U.S. Embassy in Pakistan,July 12, 1955, ForeignRelationsof the United States,1955-

1957, VIII, 189. Editorial note, ibid, VIII, 202.

46 For proposed settlement figures, see Franck, "Problemsof Economic Development in Afghanistan,"425.

Clapp-Wincek and Baldwin, Helmand ValleyProject,8; "Export-ImportBank Loan to Afghanistan,"Department

of State Bulletin, May 31, 1954, p. 836; Tudor Engineering Company, Reporton Developmentof Helmand Valley

Afghanistan(Washington, 1956), 16, 90; RichardTapper,"Nomadism in Modern Afghanistan,"in Afghanistanin

the 1970s, ed. Dupree and Albert, 126-43; Cervin, "Problemsin the Integrationof the Afghan Nation," 400-416.

47 JamesW Spain, The Wayof the Pathans(Karachi,1962), 126.

48 Baron, "SectorAnalysis,"18.

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

530 TheJournalof AmericanHistory 2002

September

crush the uprisingsof the non-Pashtunpeople of the west, southwest, and central

part of the country."49

The Helmand project symbolized Pashtun power, and the royal government

resistedeffortsto attachalternatemeaningsto it. U.S. advisersmade severalattempts

to imitate the "grassroots"inclusivityof the PVA. Aiming to dispel tribal feuds and

foster a common professionalidentity among farmers,they establishedlocal co-ops

and 4-H clubs, but Daoud's security forces broke them up. Courting the Muslim

clergywas also forbidden.Agriculturalexpertsfound the mullahs to be a progressive

force, "constantlylook[ing] for things to improve their communities, better seed,

new plants, improvedlivestock."50 Regardingreligionas an inoculationagainstCom-

munism, policy makers wanted to associate the Helmand project with Islam. In

1956, the U.S. InformationAgency produced "a 45-minute full color motion pic-

ture, which featured economic development, particularly the Helmand Valley

Project, and the religious heritage of Afghanistan."Daoud, however,regardingthe

mullahsas a subversiveelement, discouragedtheir contact with foreignadvisers,and

resented,accordingto U.S. intelligence,"anyreferencemade in his presenceto Islam

as a bulwarkagainstcommunism or as a unifying force."51

In 1955, Afghanistanbecamethe first targetof PremierNikita Khrushchev's"eco-

nomic offensive,"the Soviet Union's first venture in foreign aid. Over $100 million

in creditsto Afghanistanfinanceda fleet of taxis and buses and paid Soviet engineers

to construct airports, a cement factory, a mechanized bakery,a five-lane highway

from the Soviet borderto Kabul, and, of course, dams. The Soviets constructedthe

Jalalabaddam and canal and organized a river development scheme for the Amu

Darya River.By the 1960s, Afghanistanhad Soviet, Chinese, and West Germandam

projectsunderway.It was receivingone of the highest levels of developmentaid per

capita of any nation in the world. U.S. News and WorldReportdescribed it as a

"strangekind of cold war,"fought with money and techniciansinstead of spies and

bombs. The Atlantic called it a "showwindow for competitive coexistence."52 Pub-

licly, U.S. officialssaid this was the kind of Cold War they wanted, just a chance to

show what the differentsystemscould do in a neutralcontest.

Afghanistanhad become a new kind of buffer,a neutralarenafor a tournamentof

modernization.James A. Michener toured Afghanistan in 1955 and assessed the

49 Ritchie Calder,"Hope of Millions,"Nation, Aug. 1, 1953, pp. 87-89; Wilber, ed., Afghanistan,222. Emadi,

State,Revolution,and Superpowers in Afghanistan,41.

50 Dana Reynolds, "Utilizing Religious Principles and Leadershipin Rural Improvement,"[1962], box 125,

John H. Ohly Papers(Harry S. TrumanLibrary,Independence, Mo.).

51 National Security Council, "ProgressReport on NSC 5409," Nov. 28, 1956, ForeignRelationsof the United

States, 1955-1957, VIII, 15. State Department, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, "BiographicReport ...

Daoud."

52 Robert J. McMahon, "The Illusion of Vulnerability:American Reassessmentsof the Soviet Threat, 1955-

56," InternationalHistoryReview, 18 (Aug. 1996), 591-619. "Soviet-AfghanCommunique," Pravda, April 30,

1965, in CurrentDigest of the SovietPress,May 19, 1965, p. 26. Many of the other projectswere as poorly con-

ceived as the Helmand scheme. In the early 1970s, West Germany built a hydroelectric dam at Mahipar that,

becauseof low rainfall,held water only four months a year.A 1973 study concluded that it "mayneverbe produc-

tive."Marvin Brandt, "RecentEconomic Development,"in Afghanistanin the 1970s, ed. Dupree and Albert, 103.

Ibid., 99. "StrangeKind of Cold War,"U.S. News and WorldReport,Nov. 15, 1957, p. 160; "AtlanticReport:

Afghanistan,"Atlantic (Oct. 1962), 26.

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DammingAfghanistan: in a BufferState

Modernization 531

priceandthe stakesof the developmental contest.The turbulentHelmand"symbol-

ize[d]the wild freedomof Afghanistan," andhe regretted"thatsucha rivermustbe

broughtundercontrol."53 Historianshaveobservedthatnovels,films,andBroadway

musicalsvalidatedmodernization by associatingit withmythicconventionsin which

anAmericanovercomes Asianhostilityby a displayof competence.54

In Caravans,his

1963 novelof Afghanistan, Michenerinvitesreadersto choosebetweenfuturesimag-

inedby two characters: NurMohammed,religious,proud,andsuspiciousof change,

and Nazrullah,a foreign-educated expert,impatient,outspoken,and eagerfor help

fromthe Americansif possible,the Sovietsif necessary. Nazrullahwas an engineer,

dammingthe Helmandwith bouldersblastedfroma nearbymountain."Eachday

we mustthrowsimilarrocksinto the humanriverof Afghanistan," he tellstheAmer-

ican narrator."Herea school,therea road,down in the gorgea dam. So far,our

humanriverisn'tawarethat it's been touched.But we shallneverhalt until we've

modifiedit completely."55

Competitionalteredthe significance,but not the fortunes,of the Helmand

projectin the 1960s.Launchingthe "Development Decade,"JohnF.Kennedydeter-

mined not only to surpassSovietinitiativesbut to demonstratethe superiorityof

Americanmethodsof development.Since the superpowers were offeringsimilar

kindsof aid, distinctionswerenot easilymade,but catastrophic cropfailuresin the

SovietUnionandChinain 1959 and 1960 clarifiedthe difference."Wherever com-

munismgoes,hungerfollows,"Secretary of StateDeanRuskdeclaredin 1962. Fam-

ine in ChinaandNorthVietnamprovedthatthe "humaneandpragmaticmethods

of free men are not merelythe rightway,morally,to developan underdeveloped

country;theyaretechnicallythe efficientway."Kennedycharacteristically linkedthe

newpolicyto the rejuvenation of the UnitedStatesandthe world,callingfor a "sci-

entificrevolution"in agriculture

thatwouldengagetheenergiesof "anewgeneration

of youngpeople."Diplomatsand aid officialscarriedthe messagethatfreemen ate

better.The presidentialemissaryAverellHarriman,sent to Kabulin 1965, compli-

mentedAfghanofficialson the new Sovietfactoriesbut observedthatthe realmea-

sureof modernitywasthe abilityto growfood.The Sovietscouldnot, he explained,

"dueto character of farmworkwhichrequireshardworking withpersonal

individuals

stakein operation,ratherthanhourlypaidfactoryhandspacedby machine."56

53JamesA. Michener, Caravans(New York, 1963), 161; see also JamesA. Michener, "Afghanistan:Domain of

the Fierceand the Free,"Reader'sDigest (Nov. 1955), 161-72.

54 Richard Slotkin, GunfighterNation: The Myth of the Frontier in TwentiethCenturyAmerica (New York,

1992), 449; James T. Fisher,Dr. America:The Livesof ThomasA. Dooley,1927-1961 (Amherst, 1997); Christina

Klein, "Musicalsand Modernization:Rodgers and Hammerstein'sTheKing and I," in StagingGrowth,ed. Enger-

man et al.; and JonathanNashel, "The Road to Vietnam: ModernizationTheory in Fact and Fiction,"in Cold War

Constructions,ed. ChristianAppy (Amherst,2000), 132-54.

55 Michener, Caravans,161.

56 On John F. Kennedy'sforeign aid programs,see W W Rostow, Eisenhower, Kennedy,and ForeignAid (Aus-

tin, 1985); and Stephen G. Rabe, "Controlling Revolutions: Latin America, the Alliance for Progress,and Cold

WarAnti-Communism," in Kennedy'sQuestfor Victoryed. Thomas G. Paterson(New York, 1989), 105-22. Dean

Rusk, "The Tragedyof Cuba," Vital Speechesof the Day, Feb. 15, 1962, p. 259. J. F. Kennedy, "Statementat the

Opening Ceremony of the World Food Congress,"June 4, 1963, in PresidentJohn F Kennedy'sOfficeFiles, 1961-

1963, ed. Paul Kesarisand Robert E. Lester(microfilm, 103 reels, University Publicationsof America, 1989), Part

1, reel 11, frame 1018. Embassy Afghanistan to Department of State, March 3, 1965, ForeignRelationsof the

UnitedStates,1964-1968 (34 vols., Washington, 1992- ), XXV,1051.

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

532 TheJournalof AmericanHistory September

2002

Evidence for the efficiency of American techniques was scarce in the Helmand

Valley.The burden of American loans for the project and the absence of tangible

returnswas creating,accordingto the New YorkTimes,"adangerousstrain on both

the Afghan economy and the nation's morale"which "may have unwittingly and

indirectlycontributedto drivingAfghanistaninto Russianarms."57 Waterlogginghad

advancedin the Shamalanareato the point that structuralfoundationswere giving

way; mosques and houses were crumbling into the growing bog. In the artificial

oases, the problem was worse. An impermeablecrust of conglomerateunderlaythe

Marja and Nad-i-Ali tracts, intensifying both waterlogging and salinization. The

remedy-a system of dischargechannelsleadingto deep-boredrains-would remove

10 percent of the reclaimedland from cultivation.A 1965 study revealedthat crop

yields per acre had actually dropped since the dams were built, sharply in areas

alreadycultivatedbut evident even in areasreclaimedfrom the desert.Withdrawing

support from HAVAwas impossible."With this project,"the U.S. ambassadornoted,

"theAmericanreputationin Afghanistanis completelylinked."58For reasonsof cred-

ibility alone the United States kept pouring money in, even though by 1965 it was

clearthe projectwas failing. Diplomats complainedthat the reputationof the United

Stateshung on "astrip of concrete,"but therewas no going back.Afghanistanwas an

economic Korea, but Helmand was an economic Vietnam, a quagmire that con-

sumed money and resourceswithout the possibility of success, all to avoid making

failureobvious.

Revisions in modernization theory reinforcedthe new emphasis on agriculture

and the urgencyof changingstrategyin the Helmand. Dual economy theory,posit-

ing a division of each economy into a self-propellingmodern industrialsector and a

retrogradebut vitally important agriculturalsector, gained the attention of policy

makers in the early 1960s. "Agriculturaldevelopment is vastly more important in

modernizinga society than we used to think,"Rostow noted. Agriculturewas "asys-

tem"like industry,and modernizingit required"thatthe skills of organizationdevel-

oped in the modern urbansectorsof the society be broughtsystematicallyinto play

aroundthe life of a farmer."Development was still fundamentallya problemof scar-

city, but, while the Emkayanshad filled voids with waterand power,the U.S. Agency

for InternationalDevelopment (USAID) sought to build reservoirsof organization,tal-

ent, and mentality. RejuvenatingAfghan agriculture,aid officials believed, would

require"arevolutionin mental concepts."59

The Kennedy and Johnson administrationsrenewed the U.S. commitment to

HAVA with a fresh infusion of funds and initiatives,raising the annual aid disburse-

57 Peggy Streit and PierreStreit, "Lessonin ForeignAid Policy,"New YorkTimesMagazine, March 18, 1956, p.

56. The loan repaymentproblem was worsening by the 1960s; see Fletcher,Afghanistan,268.

58 Baron, "SectorAnalysis,"55. Stevens and Tarzi,EconomicsofAgriculturalProductionin Helmand Valley,29.

Department of State, "Elementsof U.S. Policy towardAfghanistan."

59 Gustav Ranis, "ATheory of Economic Development,"AmericanEconomicReview,51 (Sept. 1961), 533-65;

Dale W Jorgensen, "The Development of a Dual Economy,"EconomicJournal, 66 (June 1961), 309-34. W W

Rostow, "Some Lessonsof Economic Development since the War,"Departmentof StateBulletin,Nov. 9, 1964, pp.

664-65; see also W. W. Rostow, Viewfromthe SeventhFloor(New York, 1964), 124-31. Morrison Knudsen left in

1960, turning its operationsover to USAID; Baron, "SectorAnalysis,"52.

This content downloaded from 121.52.147.21 on Thu, 13 Feb 2014 05:25:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Damming Afghanistan:Modernizationin a BufferState 533

.~~~~~~~ ~ ~ ~ ~ I

Modernization meantcreatingorderlylandscapes

suchas the one picturedin the foreground,

over

which authoritycould be exercised.YetAfghanistan's

cultivatedexpansesproducedlesswealth

thanits unchartedmountainoushighlands,seen herein the distance,wherenomadicshepherds

fiercelyguardedtheirautonomy.ReprintedfromUS. Operations MissiontoAfghanistan, Afghani-

stanBuildson anAncientCivilization,1960.

ment from $16 million to $40 million annually.The "greenrevolution"approach

pioneered by the RockefellerFoundation would bring a new organizationalsystem

into play around the farmer.In 1967, USAIDand the royalgovernmentimported 170

tons of the experimentaldwarfwheat developedby Norman Borlaugin Mexico. The

high-yield seed, together with chemical fertilizersand tightly controlled irrigation,

were expected to produce grain surpluses that would be distributed through new

marketingand credit arrangements.Resettlementsubsidieshad paid off by the mid-

1960s, and the Helmand Valleywas beginning to have a lived-in look. The largecor-

porateand state farmshad vanished,and nearlyall of the land that could successfully

be farmed was privately held, much of it by smallholders. Legal titles were still

clouded by HAvAvsinattention to land surveys, but the settlers had nonetheless

sculpted wide tracts of empty land into irregularfifteen-acre parcels divided by

meandering juis, the tree-lined canals that served as boundary,water source, and

orchardfor each farm.60

Unfortunately, the juis system proved incompatible with the new plans. The

small, hilly, picturesquelymisshapenfields contributedto runoff and drainageprob-