Cardiac Monitoring PDF

Diunggah oleh

Delia LopJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Cardiac Monitoring PDF

Diunggah oleh

Delia LopHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Originalien

Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed 2016 · 111:708–714 C. Krämer · R. Pfister · T. Boekels · G. Michels

DOI 10.1007/s00063-015-0107-y Department of Internal Medicine III, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

Received: 29 July 2015

Revised: 18 August 2015

Cardiac monitoring always

Accepted: 21 September 2015

Published online: 23 October 2015

© Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015

Redaktion required after electrical injuries?

M. Buerke, Siegen

Background Besides the thermic damages of the of electrical injuries are cardiopulmonary

body, diffuse destruction of the cell mem- arrest, transthoracic current, high-voltage

Electrical injuries can be classified by the brane and secondary detriments of the injury, pathological initial electrocardio-

underlying voltage as low-voltage (< 1000 microcirculation, cardiac arrhythmias gram (ECG)/ cardiac arrhythmias, loss of

alternating current or < 1500 direct cur- that are caused by the electrophysiolog- consciousness, history of cardiovascular

rent) and high-voltage (≥ 1000 alternat- ical impact of the current are a dreaded diseases, symptomatic patients (palpita-

ing current or ≥ 1500 direct current) in- complication. Electricity that transverse tions, chest pain, dyspnea, tetanic muscle

juries [13, 30]. Additional groups of “flash the myocardium is more likely to be fatal, contraction, neurologic problems), preg-

burns” (in which there is no electrical cur- especially if it has a transthoracic (hand- nancy, abnormal laboratory (elevated

rent flow through the body of the patient) to-hand) pathway [25]. Besides the more cardiac enzymes and/or troponin levels),

and lightning burns are used at times frequent change of polarity of the AC, the concomitant injuries, soft-tissue damage

[13, 17, 21]. point of the current impact at the cardiac and burns. Despite the guideline recom-

High-voltage injuries are common- cycle also seems to be relevant. If the cur- mendations unnecessary inpatient moni-

ly work-related injuries in young men, rent transverses the myocardium during a toring frequently happens due to the fear

whereas low-voltage injuries mainly occur vulnerable period, it may provoke ventric- of cardiac complications [23].

in a domestic environment. Most of all, ular fibrillation—analogous to an R-on-T The aim of the study was to evaluate

children and women are affected by these phenomenon [14]. Cardiac arrest is more cardiac complications of children and

more frequent low-voltage accidents [4]. often seen in high-voltage injuries [1]. adults emerging after low- and high-volt-

The injuries caused by electrical accidents Overall, electrical injury causes 0.54 age electrical injury.

can for instance affect the cardiovascular, deaths per 100,000 people/year and the

respiratory, musculoskeletal and nervous mortality ranges from 3–15 %, mainly Methods

systems, kidneys, and the skin [1]. Relat- based on cardiac arrhythmia and arrest

ed mortality and morbidity are affected by [1, 3, 17, 18, 25]. These detrimental car- We evaluated medical records of patients

the magnitude of voltage, resistance of the diac complications usually happen in di- admitted because of electrical trauma

body, exposure to either direct current or rect temporal relation to the initial injury (identified by the ICD-10 code T 75.0 and

alternating current (AC), duration of ex- [1]. The European Resuscitation Council T 75.4) to the University Hospital of Co-

posure, the pathway of the current inside (ERC) recommends to monitor patients logne from January 2000 to January 2014.

the body and the contact time [1, 12]. AC in hospital who have a history of cardiore- The data were obtained from the electron-

may lead to a tetanized state of skeletal spiratory problems [25]. Besides the ERC ic health record system ORBIS (AGFA

muscle that detains the release from the criteria, other risk factors should be men- Health Care, Bonn, Germany) and re-

source of electricity [26]. tioned. Important risk factors in victims viewed for the following details: age, sex,

Table 1 Patients characteristics

Collective group High-voltage Low-voltage

Patients char- All patients Children Adults All patients All patients Children Adults

acteristics (0–17 yrs) (≥ 18 yrs) (0–17 yrs) (≥ 18 yrs)

(Mean ± SD) (n)

Age (yrs) 17.5 ± 17.0 (169) 5.0 ± 4.3 (97) 34.3 ± 12.5 (72) 40.7 ± 19.4 (7) 16.9 ± 16.7 (162) 5.0 ± 4.3 (97) 34.3 ± 12.5 (72)

Male (n) 102 (60 %) 54 (56 %) 48 (67 %) 5 (71 %) 96 (59 %) 54 (56 %) 48 (67 %)

Height (cm) 132 ± 40 (64) 120 ± 29 (43) 177 ± 10 (21) 180 ± 13 (2) 131 ± 40 (61) 110 ± 30 (43) 177 ± 10 (21)

Weight (kg) 48.0 ± 31.4 (43) 21.5 ± 15.4 (22) 75.8 ± 15.3 (21) 83.5 ± 14.8 (2) 47.1 ± 31.0 (40) 21.5 ± 15.4 (22) 75.8 ± 15.3 (21)

BMI (kg/m2) 21.4 ± 5.0 (36) 17.5 ± 3.7 (15) 24.1 ± 3.8 (21) 25.8 ± 0.7 (2) 21.3 ± 5.0 (33) 17.5 ± 3.7 (15) 24.1 ± 3.8 (21)

SD standard deviation, yrs years, m meter, kg kilogram, BMI Body mass index.

708 | Medizinische Klinik – Intensivmedizin und Notfallmedizin 8 · 2016

Table 2 Initial symptoms

Collective group High-voltage Low-voltage

All patients Children Adults All patients All patients Children Adults

(0–17 yrs) (≥ 18 yrs) (0–17 yrs) (≥ 18 yrs)

(n = 132) (n = 84) (n = 48) (n = 4) (n = 128) (n = 84) (n = 44)

Initial symptoms

Pain 94 (45 %) 65 (50 %) 29 (38 %) 3 (30 %) 91 (46 %) 65 (49 %) 26 (35 %)

Cardiac arrhythmia 16 (8 %) 10 (7 %) 6 (8 %) 2 (20 %) 14 (7 %) 10 (7 %) 4 (5 %)

Dyspnea 2 (1 %) 1 (1 %) 1 (1 %) – 2 (1 %) 1 (1 %) 1 (1 %)

Shivering 5 (2 %) 4 (3 %) 1 (1 %) – 5 (3 %) 4 (3 %) 1 (1 %)

Short absence 7 (3 %) 3 (2 %) 4 (5 %) – 7 (4 %) 3 (2 %) 4 (5 %)

Vertigo 3 (1 %) 1 (1 %) 2 (3 %) – 3 (2 %) 1 (1 %) 2 (3 %)

Paraesthesia 18 (9 %) 13 (10 %) 5 (6 %) – 18 (9 %) 13 (10 %) 5 (7 %)

Others 25 (12 %) 15 (11 %) 10 (13 %) 4 (40 %) 24 (12 %) 18 (13 %) 9 (12 %)

None 38 (18 %) 19 (15 %) 19 (25 %) 1 (10 %) 37 (19 %) 19 (14 %) 18 (24 %)

yrs years.

Table 3 Cardiac monitoring results and length of inpatient stay

Collective Group High-voltage Low-voltage

[%] [%]

All patients Children Adults All patients All patients Children Adults

(0–17 yrs) (≥ 18 yrs) (0–17 yrs) (≥ 18 yrs)

(n = 129) (n = 72) (n = 52) (n = 7) (n = 122) (n = 72) (n = 50)

Electrocardiogram recordings

Normal 109 (85 %) 67 (93 %) 37 (71 %) 5 (71 %) 104 (85 %) 67 (93 %) 37 (74 %)

Abnormal 20 (16 %) 5 (7 %) 15 (29 %) 2 (29 %) 18 (15 %) 5 (7 %) 13 (26 %)

Cardiac arrest 1 (1 %) 0 1 (2 %) 1 (14 %) 0 0 0

Sinus tachycardia 6 (5 %) 1 (1 %) 5 (10 %) 1 (14 %) 5 (4 %) 1 (1 %) 4 (8 %)

Sinus arrhythmia 3 (2 %) 2 (3 %) 1 (2 %) 0 3 (2 %) 2 (3 %) 1 (2 %)

ST segment changes 6 (5 %) 2 (3 %) 4 (8 %) 0 6 (5 %) 2 (3 %) 4 (8 %)

PAC 3 (2 %) 1 (1 %) 2 (4 %) 0 3 (2 %) 1 (1 %) 2 (4 %)

PVC 1 (1 %) 1 (1 %) 0 0 1 (1 %) 1 (1 %) 0

AV-block I° 1 (1 %) 0 1 (2 %) 0 1 (1 %) 0 1 (2 %)

Delta wave 1 (1 %) 0 1 (2 %) 0 1 (1 %) 0 1 (2 %)

yrs years, PAC premature atrial contraction, PVC premature ventricular contraction, AV atrio-ventricular.

Table 4 Length of inpatient stay and total costs

Collective group High-voltage Low-voltage

[%] [%]

All patients Children Adults All patients All patients Children Adults

(0–17 yrs) (≥ 18 yrs) (0–17 years) (≥ 18 years)

Length of inpatient stay (days)

ICU/IMC 0.77 ± 0.79 0.78 ± 0.71 0.73 ± 0.89 1.71 ± 2.36 0.72 ± 0.63 0.78 ± 0.71 0.63 ± 0.49

General ward 0.71 ± 6.46 0.12 ± 0.45 1.28 ± 9.02 16.40 ± 32.29 0.10 ± 0.48 0.12 ± 0.45 0.08 ± 0.52

Total length of stay 1.50 ± 5.86 1.13 ± 0.58 1.99 ± 8.97 13.57 ± 27.59 0.96 ± 0.63 1.12 ± 0.58 0.74 ± 0.64

Total costs (€) Collective High-voltage Low-voltage – Low-voltage – –

Group [%] [%] [%]

All patients All patients All patients p-Valuea Children Adults (n = 40) p-Valuea

(n = 122) (n = 4) (n = 118) (n = 78)

723 ± 328 1246 ± 985 703 ± 266 0.255 735 ± 293 638 ± 191 0.024

IMC intermediate care unit, ICU intensive care unit.

aUnpaired T-test.

Medizinische Klinik – Intensivmedizin und Notfallmedizin 8 · 2016 | 709

Abstract · Zusammenfassung

height, weight, body mass index, occupa- Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed 2016 · 111:708–714 DOI 10.1007/s00063-015-0107-y

tion, body location of electricity entrance, © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015

voltage of electricity, initial symptoms,

C. Krämer · R. Pfister · T. Boekels · G. Michels

date of admission, admission ward, spe-

cialty consultations, laboratory param- Cardiac monitoring always required after electrical injuries?

eters, ECG recordings and the length of

Abstract

hospital stay. Background. Controversy still exists regard- six surviving patients five showed normal EC-

A standard descriptive analysis was ing inpatient monitoring of patients exposed Gs and one a sinus tachycardia. In the low-

performed. We used unpaired t-tests for to electrical injuries. voltage (< 1000 V) group (n = 162, 56 % male;

parametric variables and Mann–Whitney Materials and methods. In a monocentric 5.0 ± 4.3 years) the ECG findings were as fol-

U-test for nonparametric variables to per- retrospective study, we evaluated the med- lows: 104 normal, 5 sinus tachycardia, 3 sinus

ical records of 169 patients admitted to the arrhythmia, 6 ST segment changes, 3 prema-

form pair wise comparisons for the total

University Hospital of Cologne from January ture atrial contraction, 1 premature ventricu-

costs. All reported p-values are two-sid- 2000 to January 2014 because of electrical lar contraction, 1 atrio-ventricular (AV)-Block

ed and p-values < 0.05 were considered trauma. The electrocardiogram (ECG) data of and 1 delta wave. In all, one patient showed a

to be statistically significant. All analyses 40 patients were missing. self-limiting supraventricular tachycardia.

were performed using SPSS version 22.0® Results. Patients in our collective were pre- Conclusion. Asymptomatic and stable pa-

(SPSS, Inc., USA). dominantly young men (60 %) with an aver- tients without any risk factors and with a nor-

age age of 17.5 ± 17 years (1 year to 73 years). mal initial ECG need no inpatient cardiac

The electrical trauma occurred occupation- monitoring after an electrical injury.

Results al (20 %), domestic (65 %), and during leisure

time (15 %). In the high-voltage (≥ 1000 V) Keywords

A total of 258 patients from January 2000 group (n = 7; 71 % male; 40.0 ± 19.4 years) Electrical injury · Low-voltage injury ·

to January 2014 were admitted to the Uni- one death was reported, related to an open High-voltage injury · Cardiac monitoring ·

intracranial injury and cardiac arrest. Of the Cardiac arrhythmia

versity Hospital of Cologne because of

electrical trauma. In the analysis, the data

of 169 patients could be included, because EKG-Monitoring nach Stromunfällen immer notwendig?

in 89 cases the medical records were not

Zusammenfassung

complete.

Hintergrund. Bezüglich der kardiologischen, überlebenden Patienten zeigten normale

stationären Überwachung von Patienten EKGs und ein Patient eine Sinustachykardie.

Patient demographics and nach Stromunfällen existieren weiterhin kon- In der Niederspannungsgruppe (< 1000 V;

characteristics of electrical injuries troverse Meinungen. n = 162, 56 % männlich; 5,0 ± 4,3 Jahre) zeig-

Material und Methoden. In einer monozen- ten sich folgende EKG-Befunde: 104 Nor-

Patients were aged 1–73 years, with a me- trischen retrospektiven Studie erfolgte die malbefunde, 5 Sinustachykardien, 3 Sinusar-

Auswertung der Elektrokardiogramme (EKGs) rhythmien, 6 ST-Streckenveränderungen, 3

dian of 17.5 ± 17 years. A total of 60 % of

von 169 Patienten, welche im Zeitraum von supraventrikuläre Extrasystolen (SVES), 1 ven-

the patients were male. The anthropomet- Januar 2000 bis Januar 2014 aufgrund eines trikuläre Extrasystole (VES), 1 atrio-ventriku-

ric data of the patients divided into chil- elektrischen Stromschlages in das Universi- lärer (AV)-Block und 1 Deltawelle. Ein Patient

dren (0–17 years) and adults (≥ 18 years) tätsklinikum Köln aufgenommen wurden. Die präsentierte eine selbstlimitierende supra-

are shown in . Table 1. In all, 4 % (n = 7) EKGs von vierzig Patienten fehlten. ventrikuläre Tachykardie (SVT).

of the injuries were high-voltage inju- Ergebnisse. Das Durchschnittsalter der Schlussfolgerung. Bei asymptomatischen,

überwiegend männlichen (60 %) Patienten stabilen Patienten ohne jegliche Risikofakto-

ries and 96 % (n = 162) were low-voltage betrug 17,5 ± 17 Jahre (1 bis 73 Jahre). Die ren und mit einem normalen initialen EKG ist

trauma. Most of the accidents occurred Unfälle ereigneten sich bei der Arbeit (20 %), keine stationäre kardiale Überwachung not-

at home (65 %) and at work (19.5 %). The bei der Hausarbeit (65 %) und während des wendig.

cases were unevenly distributed through- Spielens zu Hause (15 %). In der Gruppe der

out the study period, but there is an in- Hochspannungsunfälle (≥ 1000 V; n = 7; 71 % Schlüsselwörter

männlich; 40,0 ± 19,4 Jahre) trat ein Todesfall Stromunfall · Niederspannungsunfall ·

creasing trend from 2006 (. Fig. 1). Dur- Hochspannungsunfall · Kardiologisches

aufgrund eines offenen Schädel-Hirn-Trau-

ing the course of the year, the highest rates mas und Herzstillstandes auf. Fünf der sechs Monitoring · Kardiale Arrhythmien

of electrical injuries were found in Janu-

ary, June, and November (. Fig. 2).

Location of the current entry in . Fig. 3. Most of the patients’ initial Admission ward and

and initial symptoms symptoms were pain (45 %). Other initial specialty consultations

symptoms were paresthesia (9 %), cardi-

In the majority of cases, the entry wound ac arrhythmia (8 %), short absence (3 %), Most of the patients were admitted to the

was located at the hands (high-voltage shivering (2 %), dyspnea (1 %), and verti- pediatric cardiology (38 %) and general

group: 57 %; low-voltage group: 77 %). go (1 %) (. Table 2). pediatric department (23 %). Other de-

The locations of the entry wounds for the partments were the emergency depart-

high- and low-voltage group are shown ment (22 %), the general internal medi-

710 | Medizinische Klinik – Intensivmedizin und Notfallmedizin 8 · 2016

30 Regarding the adults, 37 patients had

Collective group

normal ECGs. The 13 abnormal ECGs

Children included 4 sinus tachycardia, 1 sinus ar-

25 Adults rhythmia, 4 ST segment changes, 2 PAC,

1 first-degree AV block and 1 delta wave

(. Table 3). One of the patient developed

20

the sinus tachycardia at night.

Cases

15 Length of hospital stay

and total costs

10

The mean length-of-stay at the collec-

tive group was 1.5 ± 5.9 days. Patients with

5 high-voltage accidents stayed a mean of

13.6 ± 27.6 days, patients with low-voltage

1.0 ± 0.6 days (. Table 4). Children with

0 a low-voltage injury stayed at the hospital

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

for 1.12 ± 0.58 days, adults on average for

Fig. 1 8 Distribution of electrical injuries from 2000–2013

0.74 ± 0.64 days. The total costs based on

the Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) re-

muneration (including all discounts and

cine intermediate (IMC)/intensive care ventricular contraction (PVC), one atrio- surcharges) of the collective group were

unit (ICU) (6 %), the cardiovascular IMC/ ventricular (AV)-block, and one delta 723 ± 328 €. No difference was found be-

ICU (4 %), and the anesthesiological ICU wave (. Table 3), including two patients tween the total costs of the high-voltage

(1 %). The most frequent specialty depart- with combined ECG changes (ST seg- group (1246 ± 985 €) and the low-volt-

ments consulted were cardiology (22 %), ment changes in combination with sinus age group (703 ± 266 €; p = 0.255). In the

trauma surgery (13 %), ophthalmology arrhythmia or sinus tachycardia). In the low-voltage group, total costs of treat-

(2 %), psychiatry (2 %), and general inter- high-voltage group five patients showed ment differed between children and adults

nal medicine (1 %). normal ECGs. Cardiac arrest and sinus (735 ± 293 € vs. 638 ± 191 €; p = 0.024;

tachycardia were found in one patient . Table 4), which resulted from a differ-

Laboratory parameters each (. Table 3). In the low-voltage group ent length of stay.

122 ECGs were available. A total of 104 of

In all, 40 of the patients showed elevat- these patients showed normal ECGs. The Discussion

ed serum creatine kinase values. Elevat- abnormal ECGs (18) contained 5 sinus

ed cardiac enzymes were found in 31 pa- tachycardia, 3 sinus arrhythmia, 6 ST seg- The present study showed an increasing

tients (muscle-brain type creatine ki- ment changes, 3 PAC, 1 PVC, 1 first-degree number of patients taken to the Hospital

nase; CK-MB) and elevated levels for AV block and 1 delta wave (. Table 3), in- of Cologne after electrical accidents from

troponin T in 25 cases. In the high-volt- cluding 2 patients with combined ECG 2006 to 2013. Accordingly, Sun et al. [28]

age group the mean laboratory parame- changes (ST segment changes in com- noted an increasing trend from 2005, with

ters were as follows: 170.5 ± 64.5 U/l (se- bination with sinus arrhythmia or sinus an annual rate of 18.1 %.

rum creatine kinase; CK), 13.7 ± 6.6 U/l tachycardia). In this study, one patient died after a high-

(CK-MB) and 0.002 ± 0.002 µg/l (tropo- Stratified into children and adults, the voltage accident because of traumatic brain in-

nin T). In the low-tension group, the pa- ECG findings of the low-voltage group jury. The resulting mortality rate of 0.62 % was

tients showed CK, CK-MB, and troponin were as follows: 67 of the children had lower compared with those described in pre-

T values of 169 ± 97 U/l, 20.9 ± 12.6 U/l and normal ECGs, the abnormal ECGs (5) vious studies. Authors present various mortal-

0.001 ± 0.003 µg/l, respectively. consisted of 1 sinus tachycardia, 2 sinus ity rates of electric injuries ranging from 2 %

arrhythmia, 2 ST segment changes, 1 PAC in Iran [22] to 9.1 % in Turkey [2]. In the high-

ECG recording results and 1 PVC (. Table 3), including 2 chil- voltage groups the reported mortality rates

dren with combined ECG changes (ST are up to 15–17 % [17, 19]. We could only in-

ECGs of 129 patients were available for re- segment changes in combination with si- clude the data of the patients that were admit-

view. In all, 109 of these ECGs were nor- nus arrhythmia or sinus tachycardia). One ted to our hospital. No information is provid-

mal, 20 abnormal. The abnormal EC- of the children developed a secondary, ed about patients after electrical accidents who

Gs consisted of one cardiac arrest, six si- self-limiting sinus tachycardia, another did not reach the hospital. For that reason the

nus tachycardia, three sinus arrhythmia, children single PAC at night after an ini- actual number of electrical incidents as well as

six ST segment changes, three premature tial normal ECG. the number of electrical accidents with lethal

atrial contraction (PAC), one premature consequence may be even higher.

Medizinische Klinik – Intensivmedizin und Notfallmedizin 8 · 2016 | 711

Originalien

20

Collective group

Low voltage children

18 Low voltage adults

High voltage

16

14

12

Cases

10

0

January February March April May June July August September October November December

Fig. 2 8 Distribution of electrical injuries in the course of the year

Children and adolescents accounted for

8%

almost 20 %. The high percentage of chil-

14% 5%

dren (57 %) in this study could be respon-

2%

sible for the lack of differences by sex as

1%

the typical work-related injuries are not

5%

relevant in young ages. Children are in-

3% volved in electrical injuries that mostly oc-

cur in the course of playing at home. This

57% is supported by the fact that the percent-

29% 77% age of men at the present adult group is

even higher than in the collective group.

The high proportion of children is in ac-

cordance with the survey of Searle et al.

[23]. A total of 43 % of the 268 patients ad-

Hand Whole body

Hand mitted to their department after electric

Arm Unknown

Head accidents have been children aged 0–17

Head No note years. Also the percentage of 39 % female

Unknown

a b Trunk patients was similar to our findings.

The incidence of cardiac arrhythmia

Fig. 3 8 Body location of the entry wound at the high (a), and low-voltage (b) group after electrical accidents described in the

literature ranges from 15 to 40 % [5, 29].

Most of the cardiac arrhythmias that oc-

Compared with most of the recent scribed the percentage of men with 84– curred could be seen at the initial ECG.

studies, the percentage of women was 90 %. In the study of Sun et al. [28] the This is in accordance with most of the re-

fairly high with 40 % in the present sur- subjects were predominantly young men cent studies, where authors stated that the

vey. Akkas et al. [1] and Sun et al. [28] de- that injured in work-related incidents. cardiac arrhythmias can usually be record-

712 | Medizinische Klinik – Intensivmedizin und Notfallmedizin 8 · 2016

ed on 11 patients showing abnormal ECGs,

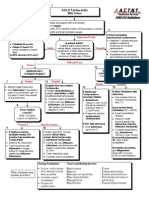

Electrical injury Electrical injury

especially consisting of sinus tachycardia.

Furthermore, they showed significant re-

Disturbed state of the Yes lationships between mortality and tachy-

Monitoring of vital functions

(emergency ward or intermediate care/intensive care unit)

vital functions?

cardia. Overall, it seems difficult to com-

No pare the findings of the ECG analysis as

Case history and physical Case history and physical there is no coherent definition of unspe-

examination examination, laboratory

cific ECG changes or abnormalities.

Concerning the necessity of ECG

Admission

Yes monitoring after electrical injuries not on-

ECG and laboratory *Risk factors?

ly primary arrhythmias but also second-

No ary arrhythmias, even arising after a nor-

Yes mal initial ECG, are appreciable. In the

Admission with ECG monitoring Symptomatic?

for 24 hours context of the present study, one adult pa-

No

tient showed a tachycardia at night after a

Yes

Abnormal ECG? normal initial ECG that was successfully

(12-lead ECG and rhythm strip)

Discharge or hospital stay treated with beta-blocker. There are sev-

No eral studies that examined the occurrence

a b Discharge of secondary arrhythmias after electrical

injuries so far. Blackwell et al. [9] moni-

Fig. 4 8 Management of patients after electrical injury before (a), and after the study (b). *Risk fac- tored 196 patients after electrical inju-

tors: high-voltage injury, loss of consciousness, history of cardiovascular diseases, pregnancy, abnor- ry and none of these 196 patients showed

mal laboratory (elevated cardiac enzymes and/or troponin levels), transthoracic current, concomitant delayed arrhythmias. As a result of their

injuries, soft-tissue damage and burns study the authors developed a new algo-

rithm for the treatment of patients after

electrical injury. The management proto-

ed directly after the injury [1, 16]. Our data cific ECG changes in 13 % and abnormal col recommends no ECG monitoring of

revealed initial abnormal ECGs in 15.5 % ECGs in 11 % of their patients. Even a to- asymptomatic patients with normal ini-

of the patients, which may have existed tal of 36 % ECG abnormalities was report- tial ECG after a low-voltage injury. Pa-

before the injury. These findings are in ac- ed in a study of Solem et al. [27], including tients with significant symptoms or ECG

cordance to recent studies in the way that the data of 64 patients after electrical inju- changes should be monitored for at least

the information about abnormal ECGs in ries. Similar values were found by Black- 6 h. Besides these studies, there are occa-

patients after electric injuries is ranging well and Haylar [9]. sional case reports describing cardiac ar-

from 3 to 37 % [4, 9, 27]. At their review Referred to the children with low-volt- rhythmias arising hours or days after the

about electrical injury and the frequen- age accidents, 6.9 % of the initial ECGs accident [6, 20].

cy of cardiac complications, Arrowsmith showed abnormalities. This is lower than Referred to the children at the present

et al. [4] evaluated ECG data of 104 pa- a current study of Searle et al. [23] ana- study, secondary arrhythmias were found

tients admitted during a 5-year period. In lyzing secondary data of survivors of elec- in two cases, including a self-limiting si-

all, 3 % of the ECGs were abnormal as they trical accidents to determine the frequen- nus tachycardia and single PAC at night.

showed self-limiting atrial and ventricu- cy of cardiac arrhythmia. The study re- None of the children developed fatal car-

lar ectopic beats and an atrial fibrillation vealed mild cardiac arrhythmias—includ- diac arrhythmias. On the contrary, no sec-

that was medicated with digoxin. The EC- ing sinus tachycardia, sinus bradycardia, ondary arrhythmias were found by Bailey

Gs did not show severe arrhythmias and and isolated extra beats—in 28.7 % of the at al. [8] and Gokdemir et al. [15] at their

it was discernable that cardiac complica- children. An antiarrhythmic therapy was studies, including 141 and 36 children, re-

tions were more frequent in those who not necessary. Also abnormal ECGs were spectively. Accordingly, none of the 38

had a loss of consciousness at the time of shown in a retrospective study of Claudet children, monitored at a study of Celik

injury or who suffered a high-voltage ac- et al. [11]. Of the 48 children, 8 showed et al. [10] at least for 24 h after electrical

cident. At a collective of 134 high-risk pa- abnormal ECGs, such as sinus tachycar- accidents, developed cardiac abnormali-

tients monitored after an electrical inju- dia, incomplete right bundle branch block ties. However, three of the children’s EC-

ry, 11 % had abnormal initial ECGs. None (RBBBs) and V1negative T-waves. The Gs showed nonspecific temporary ST seg-

of the patients developed potential late ar- ECGs normalized within 12 h and no de- ment changes. The CK and CK-MB values

rhythmia [7]. Similar findings of abnor- layed arrhythmias occurred. Contrary to were elevated in all of the 31 determined

mal ECG revealed a study of Sigmund et our study, the authors defined incomplete cases. Overall, four of these patients sus-

al. [24] where the authors examined the RBBBs as abnormal ECGs. This could be a tained low-voltage injuries.

ECGs of 320 patients after low-voltage reason for their higher rate (16.7 %) of ab-

electrical accidents. They found unspe- normal ECGs. Gokdemir et al. [15] report-

Medizinische Klinik – Intensivmedizin und Notfallmedizin 8 · 2016 | 713

Originalien

Limitations References 21. Luz D, Millan L, Alessi M, Uguetto W, Paggiaro A,

Gomez D, Ferreira M (2009) Electrical burns: a ret-

1. Akkas M, Hocagil H, Didem A, Bulent E, Mahir KM, rospective analysis across a 5-year period. Burns

The present study has some limitations. Mahir OM (2012) Cardiac monitorization in pa- 35(7):1015–1019

First, the data were evaluated retrospec- tients with electrocution injury. Ulus Travma Acil 22. Maghsoudi H, Adyani Y, Ahmadian N (2007) Elec-

Cerrahi Derg 18(4):301–305 trical and lightning injuries. J Burn Care Res

tively. For that reason no pre-ECGs were 28(2):255–261

2. Al B, Aldemir M, Güloğlu C, Kara IH, Girgin S (2006)

available and no information is given Elektrik çarpmasi sonucu acil servise başvuran has- 23. Searle J, Slagman A, Maaß W, Möckel M (2013) Car-

about arrhythmias existing before the in- talarin epidemiyolojik özellikleri. Ulus Travma Acil diac monitoring in patients with electrical injuries.

Cerrahi Derg 12(2):135–142 An analysis of 268 patients at the Charité Hospital.

jury. Second, the number of patients is in- Dtsch Arztebl Int 110(50):847–853

3. Arnoldo BD, Purdue GF, Kowalske K, Helm PA, Bur-

sufficient in relation to the incidence of ris A, Hunt JL (2004) Electrical injuries: a 20-Year re- 24. Sigmund M, Völker H, Effert S, Kieback D (1991)

cardiac arrhythmias in order to derive view. J Burn Care Rehabil 25(6):479–484 Herzschädigung nach Stromunfall. Versicherungs-

4. Arrowsmith J, Usgaocar RP, Dickson WA (1997) medizin 43(5):148–151

general recommendations for ECG mon- 25. Soar J, Perkins GD, Abbas G, Alfonzo A, Barelli A,

Electrical injury and the frequency of cardiac com-

itoring after electrical injuries. Thus, the plications. Burns 23(7–8):576–578 Bierens JJ., Brugger H, Deakin CD, Dunning J, Geor-

present study has to be seen in addition to 5. Arya KR, Taori GK, Khanna SS (1996) Electrocardio- giou M, Handley A J, Lockey DJ, Paal P, Sandro-

graphic manifestations following electric injury. Int ni C, Thies K-C, Zideman DA, Nolan JP (2010) Eu-

previous findings. One final limitation is ropean Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Re-

J Cardiol 57(1):100–101

that the present study is monocentric and 6. Bailey B, Forget S, Gaudreault P (2001) Prevalence suscitation 2010 Section 8. Cardiac arrest in spe-

therefore only data of the patients that of potential risk factors in victims of electrocution. cial circumstances: electrolyte abnormalities, poi-

Forensic Sci Int 123(1):58–62 soning, drowning, accidental hypothermia, hy-

were admitted to our hospital could be perthermia, asthma, anaphylaxis, cardiac surgery,

7. Bailey B, Gaudreault P, Thivierge RL (2007) Cardi-

included. Furthermore, no information is ac monitoring of high-risk patients after an electri- trauma, pregnancy, electrocution. Resuscitation

given about patients who died before the cal injury: a prospective multicentre study. Emerg 81(10):1400–1433

Med J 24(5):348–352 26. Soar J, Perkins G, Abbas G, Alfonzo A, Barelli A,

arrival of the emergency ambulance. That Bierens J, Brugger H, Deakin C, Dunning J, Geor-

8. Bailey B, Gaudreault P, Thivierge RL, Turgeon JP

is why the actual number of electrical ac- (1995) Cardiac monitoring of children with house- giou M, Handley A, Lockey D, Paal P, Sandroni C,

cidents cannot be stated. hold electrical injuries. Ann Emerg Med 25(5):612– Thies K-C, Zideman D, Nolan J (2010) Kreislaufstill-

617 stand unter besonderen Umständen: Elektrolyt-

9. Blackwell N, Hayllar J (2002) A three year prospec- störungen, Vergiftungen, Ertrinken, Unterkühlung,

Conclusion for clinical practice tive audit of 212 presentations to the emergency Hitzekrankheit, Asthma, Anaphylaxie, Herzchirur-

department after electrical injury with a manage- gie, Trauma, Schwangerschaft, Stromunfall. Notfall

ment protocol. Postgrad Med J 78(919):283–285 Rettungsmed 137:679–722

55Asymptomatic and stable patients 27. Solem L, Fischer RP, Strate RG (1977) The natural

10. Çelik A, Ergün O, Özok G (2004) Pediatric electrical

without any risk factors and with a injuries: a review of 38 consecutive patients. J Pe- history of electrical injury. J Trauma 17(7):487–492

normal initial ECG need no inpatient diatr Surg 39(8):1233–1237 28. Sun CF, Lv X-X, Li Y-J, Li W-Z, Jiang L, Li J, Feng J,

11. Claudet I, Maréchal C, Debuisson C, Salanne S Chen S-Z, Wu F, Li X-Y (2012) Epidemiological stud-

cardiac monitoring after electrical in- ies of electrical injuries in Shaanxi Province of Chi-

(2010) Risque de trouble du rythme et électri-

jury. sation par courant domestique. Arch Pediatr na: a retrospective report of 383 cases. Burns

55Victims of electrical injury with unsta- 17(4):343–349 38(4):568–572

12. Eisenacher-Abelein I, Reuchlein H (2009) Station- 29. Vierhapper MF, Lumenta DB, Beck H, Keck M, Ka-

ble vital functions and/or risk factors molz LP, Frey M (2011) Electrical injury: a long-

äre Überwachung nach Stromunfall? Arbeitsmed.

and/or clinical symptoms and/or an Sozialmed. Umweltmed 444:35–36 term analysis with review of regional differences.

abnormal ECG should be admitted to 13. Fish JS, Theman K, Gomez M (2012) Diagnosis of Ann Plast Surg 66(1):43–46

long-term sequelae after low-voltage electrical in- 30. Zschiesche W (2010) Stromunfälle am Arbeitsplatz.

an emergency ward or an intermedi- Gefährdungen, gesundheitliche Auswirkungen,

jury. J Burn Care Res 33(2):199–205

ate care/ intensive care unit (. Fig. 4). 14. Geddes LA, Bourland JD, Ford G (1986) The mecha- ärztliche Maßnahmen. Berufsgenossenschaft

nism underlying sudden death from electric shock. Energie Textil Elektro Medienerzeugnisse – BG

Med Instrum 20(6):303–315 ETEM, Köln. Arbeitsmed Sozialmed Umweltmed

Corresponding address 15. Gokdemir MT, Kaya H, Söğüt O, Cevik M (2013) Fac- 454:164–169

tors affecting the clinical outcome of low-voltage

PD Dr. G. Michels electrical injuries in children. Pediatr Emerg Care

Department of Internal Medicine III, 29(3):357–359

University of Cologne 16. Haberkern M, Martinolli L (2007) Notfallmanage-

ment bei Elektrounfällen. Schweiz Med Forum

Kerpener-Str. 62, 50937 Cologne

7:649–654

guido.michels@uk-koeln.de 17. Handschin AE, Jung FJ, Guggenheim M, Moser V,

Wedler V, Contaldo C, Kuenzi W, Giovanoli P (2007)

Die chirurgische Behandlung von Hochspan-

Compliance with nungsverletzungen. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir

Ethics Guidelines 39(5):345–349

18. Hussmann J, Kucan J, Russell R, Bradley T, Zamboni

W (1995) Electrical injuries—morbidity, outcome

Conflict of Interest. C. Krämer, R. Pfister, T. Boekels, and treatment rationale. Burns 21(7):530–535

and G. Michels state that there are no conflicts of 19. Kaloudová Y, Sín R, Rihová H, Brychta R, Suchánek

interest. I, Martincová A (2006) High voltage electrical inju-

ries. Acta Chir Plast 48(4):119–122

The study was approved by the institutional ethic

20. Kose S, Iyisoy A, Kursaklioglu H, Demirtas E (2003)

committee. No informed consent was necessary as

Electrical injury as a possible cause of sick sinus

the retrospective data were obtained within the stan-

syndrome. J Korean Med Sci 18(1):114–115

dard diagnostic flow chart (. Fig. 4) in all patients

with electrical injuries.

714 | Medizinische Klinik – Intensivmedizin und Notfallmedizin 8 · 2016

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Mercedes Benz M272 EngineDokumen28 halamanMercedes Benz M272 EngineJijo Mercy100% (2)

- GOLDEN DAWN 1 10 The Banishing Ritual of HexagramDokumen4 halamanGOLDEN DAWN 1 10 The Banishing Ritual of HexagramF_RC86% (7)

- Women's Prints & Graphics Forecast A/W 24/25: Future TerrainsDokumen15 halamanWomen's Prints & Graphics Forecast A/W 24/25: Future TerrainsPari Sajnani100% (1)

- Stress TestDokumen2 halamanStress TestDavid GonzalesBelum ada peringkat

- EKG Clep TestDokumen13 halamanEKG Clep TestElissa LafondBelum ada peringkat

- Dystolic Dysfunction Ppt. SalmanDokumen42 halamanDystolic Dysfunction Ppt. SalmanMustajab MujtabaBelum ada peringkat

- Real Estate QuizzerDokumen27 halamanReal Estate QuizzerRochelle Adajar-BacallaBelum ada peringkat

- 2020 Sustainabilty Report - ENDokumen29 halaman2020 Sustainabilty Report - ENGeraldBelum ada peringkat

- Approach To Ventricular ArrhythmiasDokumen18 halamanApproach To Ventricular ArrhythmiasDavid CruzBelum ada peringkat

- Dysrhythmias: Sinus Node Dysrhythmias Tachycardia, and Sinus ArrhythmiaDokumen5 halamanDysrhythmias: Sinus Node Dysrhythmias Tachycardia, and Sinus ArrhythmiaKayelyn-Rose Combate100% (1)

- DIT High Yield Questions PDFDokumen13 halamanDIT High Yield Questions PDFjoshBelum ada peringkat

- ACLS Precourse Self-AssessmentDokumen3 halamanACLS Precourse Self-AssessmentHollan GaliciaBelum ada peringkat

- Ekg Panum or OsceDokumen69 halamanEkg Panum or OsceGladish RindraBelum ada peringkat

- ECG Interpretation and Dysrhythmias: Karen L. O'Brien MSN, RN JAN 07Dokumen60 halamanECG Interpretation and Dysrhythmias: Karen L. O'Brien MSN, RN JAN 07ampogison08Belum ada peringkat

- Valvular Heart Disease. KulDokumen60 halamanValvular Heart Disease. KulIntan Kumalasari RambeBelum ada peringkat

- Hypertensive Crisis: Megat Mohd Azman Bin AdzmiDokumen34 halamanHypertensive Crisis: Megat Mohd Azman Bin AdzmiMegat Mohd Azman AdzmiBelum ada peringkat

- ACCA Cardiogenic and Septic ShockDokumen1 halamanACCA Cardiogenic and Septic Shockjose miguelBelum ada peringkat

- Defining Hemodynamic InstabilityDokumen9 halamanDefining Hemodynamic InstabilitynadyajondriBelum ada peringkat

- Cardiac II Study GuideDokumen6 halamanCardiac II Study GuiderunnermnBelum ada peringkat

- Braunwald Lecture Series #2Dokumen33 halamanBraunwald Lecture Series #2usfcards100% (2)

- GREY BOOK August 2017 66thDokumen146 halamanGREY BOOK August 2017 66thxedoyis969Belum ada peringkat

- Cardiac ElectrophysiologyDokumen40 halamanCardiac Electrophysiologyashwinagrawal1995Belum ada peringkat

- Life Threatening Arrhythmia and ManagementDokumen40 halamanLife Threatening Arrhythmia and ManagementRuki HartawanBelum ada peringkat

- 8 - DR. Khaled - Cardiac SurgeryDokumen26 halaman8 - DR. Khaled - Cardiac SurgeryMuhand.Belum ada peringkat

- ECG Workout Flashcards: Atrial ArrhythmiasDokumen27 halamanECG Workout Flashcards: Atrial ArrhythmiasDima HabanjarBelum ada peringkat

- Cardiac Pacemakers NewDokumen108 halamanCardiac Pacemakers NewAlif Fanharnita BrilianaBelum ada peringkat

- Acls TachiDokumen1 halamanAcls TachiratnawkBelum ada peringkat

- Acute Coronary Syndrome: Dr. Suhaemi, SPPD, FinasimDokumen65 halamanAcute Coronary Syndrome: Dr. Suhaemi, SPPD, FinasimshintadeviiBelum ada peringkat

- DR K Chan - Ecg For SVT Made EasyDokumen66 halamanDR K Chan - Ecg For SVT Made Easyapi-346486620Belum ada peringkat

- Lecture 2 Ischemic Heart DiseasesDokumen19 halamanLecture 2 Ischemic Heart DiseasesOsama MalikBelum ada peringkat

- Cardiac Case StudyDokumen44 halamanCardiac Case StudyNatalia Bernard100% (1)

- HUTTDokumen25 halamanHUTTdrdj14100% (1)

- The Cardiovascular SystemDokumen20 halamanThe Cardiovascular Systembuzz QBelum ada peringkat

- Cme Atrial FibrillationDokumen43 halamanCme Atrial FibrillationAlex Matthew100% (1)

- ElectrocardiogramDokumen169 halamanElectrocardiogramjitendra magarBelum ada peringkat

- Heart Sounds: Mitral Regurgitation Congestive Heart FailureDokumen6 halamanHeart Sounds: Mitral Regurgitation Congestive Heart FailurecindyBelum ada peringkat

- Basic Arrythmia AnalysisDokumen60 halamanBasic Arrythmia AnalysisZakky KurniawanBelum ada peringkat

- Spectrum of Acute Coronary Syndrome: Milagros Estrada-Yamamoto, MDDokumen62 halamanSpectrum of Acute Coronary Syndrome: Milagros Estrada-Yamamoto, MDAnonymous HH3c17osBelum ada peringkat

- EkgDokumen67 halamanEkgFendi Rafif Dad'sBelum ada peringkat

- Arterial LinesDokumen9 halamanArterial LinesRei IrincoBelum ada peringkat

- Sca ACLS 2015Dokumen1 halamanSca ACLS 2015Jhon100% (1)

- EGurukul Cardiology 2.0Dokumen287 halamanEGurukul Cardiology 2.0Merin Emanuel KBelum ada peringkat

- CPR ACLS Study GuideDokumen18 halamanCPR ACLS Study GuideJohn Phamacy100% (1)

- ECG Quiz Review and Practice Strip AnswersDokumen7 halamanECG Quiz Review and Practice Strip AnswersAABelum ada peringkat

- Approach To Heart MurmursDokumen57 halamanApproach To Heart MurmursRadley Jed PelagioBelum ada peringkat

- Cardio Lab MedsDokumen11 halamanCardio Lab MedsDianne Erika MeguinesBelum ada peringkat

- Learning Ecg ModulesDokumen150 halamanLearning Ecg ModulesdodiBelum ada peringkat

- Атлас ЭКГDokumen320 halamanАтлас ЭКГЕвгений КлимовBelum ada peringkat

- Dysrhythmia Instructor 2018 2 PDFDokumen105 halamanDysrhythmia Instructor 2018 2 PDFtvrossyBelum ada peringkat

- Temporary Pacemakers-SICU's 101 PrimerDokumen51 halamanTemporary Pacemakers-SICU's 101 Primerwaqas_xsBelum ada peringkat

- Ecg Interpretation: Gel PDokumen2 halamanEcg Interpretation: Gel PjuliperBelum ada peringkat

- Assessment of Valves': The 2nd Cambridge Advanced Emergency Ultrasound CourseDokumen48 halamanAssessment of Valves': The 2nd Cambridge Advanced Emergency Ultrasound Coursestoicea_katalinBelum ada peringkat

- Cardiac FailureDokumen63 halamanCardiac FailureNina OaipBelum ada peringkat

- SodaPDF-converted-Acute Coronary SyndromeDokumen33 halamanSodaPDF-converted-Acute Coronary SyndromeDeni Suryadi PratamaBelum ada peringkat

- Cardiac Pacing: Terms You Will Become Familiar With in This Section of TheDokumen21 halamanCardiac Pacing: Terms You Will Become Familiar With in This Section of TheClt Miskeen100% (1)

- Care of The Patient With A Cardiac Mechanical DisorderDokumen8 halamanCare of The Patient With A Cardiac Mechanical DisorderthubtendrolmaBelum ada peringkat

- Sepsis Update 2019Dokumen44 halamanSepsis Update 2019Yeshwanth Umapathi100% (1)

- PAC and Hemodynamic Monitoring 2-4-08Dokumen32 halamanPAC and Hemodynamic Monitoring 2-4-08anum786110Belum ada peringkat

- Aha Guidelines StemiDokumen94 halamanAha Guidelines StemiDika DekokBelum ada peringkat

- Ngaji Arrythmia Cordis 3Dokumen122 halamanNgaji Arrythmia Cordis 3Dhita Dwi NandaBelum ada peringkat

- EKG InterpretationDokumen63 halamanEKG InterpretationMiriam Cindy MathullaBelum ada peringkat

- Aortic Stenosis:: Updates in Diagnosis & ManagementDokumen48 halamanAortic Stenosis:: Updates in Diagnosis & ManagementCuca PcelaBelum ada peringkat

- A Simple Guide to Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsDari EverandA Simple Guide to Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsBelum ada peringkat

- Biochemistry - Syllabus Marks EtcDokumen8 halamanBiochemistry - Syllabus Marks EtcshahzebBelum ada peringkat

- Grade 8 MAPEH ReviewerDokumen4 halamanGrade 8 MAPEH ReviewerVictoria DelgadoBelum ada peringkat

- Bright Ideas 2 Unit 1 Test-Fusionado-Páginas-1-33Dokumen33 halamanBright Ideas 2 Unit 1 Test-Fusionado-Páginas-1-33Eleonora Graziano100% (1)

- Spining Mill in IndiaDokumen74 halamanSpining Mill in IndiaMahendra Shah100% (4)

- Types of Welding Defects PDFDokumen12 halamanTypes of Welding Defects PDFDhiab Mohamed AliBelum ada peringkat

- 1965 Elio R. Freni - Electrolytic Lead Refining in SardiniaDokumen9 halaman1965 Elio R. Freni - Electrolytic Lead Refining in SardiniaGeorgettaBelum ada peringkat

- REE0913ra LegazpiDokumen6 halamanREE0913ra LegazpiScoopBoyBelum ada peringkat

- Gunny PasteDokumen2 halamanGunny PastejpesBelum ada peringkat

- Evolution of Indian TolucaDokumen28 halamanEvolution of Indian TolucaAlberto Duran IniestraBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction On Photogrammetry Paul R WolfDokumen33 halamanIntroduction On Photogrammetry Paul R Wolfadnan yusufBelum ada peringkat

- Ficha Tecnica p501Dokumen4 halamanFicha Tecnica p501LizbethBelum ada peringkat

- Shaped House With Gablehip Roof 2020Dokumen11 halamanShaped House With Gablehip Roof 2020Marco CamposBelum ada peringkat

- Annual Report 2016Dokumen171 halamanAnnual Report 2016Angel GrilliBelum ada peringkat

- HSD Spindle Manual ES789 ES799 EnglishDokumen62 halamanHSD Spindle Manual ES789 ES799 EnglishCamilo Andrés Lara castilloBelum ada peringkat

- Enzymes MCQsDokumen2 halamanEnzymes MCQsNobody's PerfectBelum ada peringkat

- Metal-Tek Electric Contact Cleaner Spray - TDS (2021)Dokumen1 halamanMetal-Tek Electric Contact Cleaner Spray - TDS (2021)metal-tek asteBelum ada peringkat

- 10-Msds-Remove Oil (Liquid)Dokumen9 halaman10-Msds-Remove Oil (Liquid)saddamBelum ada peringkat

- 2 2 1 A Productanalysis 2Dokumen5 halaman2 2 1 A Productanalysis 2api-308131962Belum ada peringkat

- Penerapan Metode Sonikasi Terhadap Adsorpsi FeIIIDokumen6 halamanPenerapan Metode Sonikasi Terhadap Adsorpsi FeIIIappsBelum ada peringkat

- Proposed Revisions To Usp Sterile Product - Package Integrity EvaluationDokumen56 halamanProposed Revisions To Usp Sterile Product - Package Integrity EvaluationDarla Bala KishorBelum ada peringkat

- 49728393Dokumen17 halaman49728393MarcoBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction To Mass Transfer - Part 1Dokumen39 halamanIntroduction To Mass Transfer - Part 1Biniyam haile100% (1)

- Pictionary Unit 12 - IGMSDokumen4 halamanPictionary Unit 12 - IGMSNadia Jimenez HernandezBelum ada peringkat

- 1.8 CarderoDokumen29 halaman1.8 CarderoRodrigo Flores MdzBelum ada peringkat

- Ffu 0000034 01Dokumen8 halamanFfu 0000034 01Karunia LestariBelum ada peringkat