Quan L. Do Parents Value Drowning Prevention Information at Discharge From The Emergency Department

Diunggah oleh

VictoriaMuroJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Quan L. Do Parents Value Drowning Prevention Information at Discharge From The Emergency Department

Diunggah oleh

VictoriaMuroHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

PEDIATRICS/BRIEF REPORT

Do Parents Value Drowning Prevention

Information at Discharge From the Emergency

Department?

From the Department of Pediatrics, Linda Quan, MD*‡ Study objective: We determined parent recall and perceived

University of Washington School of Elizabeth Bennett, MPH, CHES‡ usefulness of drowning prevention messages included in routine

Medicine,* Children’s Hospital and Peter Cummings, MD, MPH‡§ computer-generated discharge instructions.

Regional Medical Center,‡ Harbor-

Peter Henderson

view Injury Prevention and Research

Center and the Department of Mark A. Del Beccaro, MD*‡ Methods: All pediatric emergency department patients’ com-

Epidemiology, School of Public Health puterized discharge instructions included 3 prevention messages:

and Community Medicine,§ University wear a life vest, swim in safe areas, and do not drink alcohol

of Washington, Seattle, WA.

while swimming or boating. Parents were telephoned 1 to 2

Received for publication

August 14, 2000. Revision received

weeks after the visit and asked to recall the prevention messages

December 22, 2000. Accepted for and rate the usefulness of the instructions. Responses were

publication January 8, 2001. linked with patient characteristics and ED visit variables (day

Supported in part by grant No. MCH- and time of visit, duration of ED visit, severity of condition, diag-

534003-01-0 from the Department of

nostic category, number of tests, and treatments).

Health and Human Services, Health

Resources and Services Administration, Results: Of 914 parents who were contacted, 795 were eligi-

Maternal and Child Health Bureau,

Emergency Medical Services for ble. Of those, 619 (78%) completed the interview. Fifty percent

Children, and by a gift from the of parents recalled receiving drowning prevention information;

Norcliffe Fund. of these, 41% recalled unaided the life vest messages and

Reprints not available from the 35% of 155 parents who did not own a life vest stated they

authors.

would subsequently consider buying their child a life vest. Most

Address for correspondence: Linda

(88%) rated the prevention information useful or very useful.

Quan, MD, Emergency Services

CH04, Children’s Hospital and No patient or visit variables were associated with usefulness

Regional Medical Center, 4800 Sand ratings.

Point Way NE, Seattle, WA 98105;

206-526-2599, fax 206-729-3070; Conclusion: Written injury prevention messages with dis-

E-mail lquan@chmc.org charge instructions were well received by parents of children in

Copyright © 2001 by the American a pediatric ED. The ED may be a setting where families could

College of Emergency Physicians.

receive injury prevention education.

0196-0644/2001/$35.00 + 0

47/1/114091 [Quan L, Bennett E, Cummings P, Henderson P, Del Beccaro MA.

doi:10.1067/mem.2001.114091 Do parents value drowning prevention information at discharge

from the emergency department? Ann Emerg Med. April

2001;37:382-385.]

3 8 2 ANNALS OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE 37:4 APRIL 2001

DROWNING PREVENTION AND CHILDREN

Quan et al

INTRODUCTION patients received computer-generated, printed discharge

instructions (Echart version 4.10; Spacelabs Medical,

Emergency departments could be fertile sites for dissemi- Inc., Redmond, WA). A nurse or physician reviewed the

nation of injury prevention education and materials. In discharge instructions with the patient’s family.

1998, a total of 100,350,000 patients visited EDs; 25% Between May 14 and July 6, 1999, all discharge in-

were children younger than 15 years. Potentially, the structions included 3 brief messages: wear a life vest

majority of the 25 million children/families seen in EDs around water, swim in safe areas, and do not drink alco-

represented an educational opportunity. Moreover, ED hol while swimming or boating (Figure). These messages

patients and their families may be in need of injury pre- were at a sixth-grade reading level in English and Spanish

vention education; only 45% of ED parents believed that and without illustrations. ED staff were aware of the water

most injuries could be prevented.1 safety messages but were not asked to review them with

Many ED care plans are based on the belief that patients patients.

in crisis recognize their vulnerability and are more open The interviews were conducted through Market Trends

to interventions. Limited data support this concept; the (Seattle, WA), a market research firm that conducts quali-

caretakers of pediatric patients with mental health crises tative and quantitative research. Telephone interviewers

had increased likelihood of limiting access to potentially used by the company were specially trained for this pro-

lethal weapons if they received injury prevention educa- ject and had their calls monitored.

tion in the ED.2 Yet, most ED patients with ingestions did An interviewer made up to 4 attempts to telephone eli-

not receive poisoning prevention instructions.3 gible parents between 1 and 2 weeks after their children’s

The process of providing patient information in the ED ED visit. Parents or caregivers were eligible if they had

is plagued with logistical problems. Procuring, storing, accompanied the patient to the ED. They were not eligible

updating, and distributing handouts of written instruc- if the discharge diagnosis was suspected abuse or the visit

tions are cumbersome tasks in a busy ED. Their use is left was a repeat ED visit during the study period. Interview

to the memory, time, and motivation of individual ED information was not collected if the call was not made

staff. If provided, injury prevention education is probably within the 2-week interval, if the eligible parent was not

most often given as verbal advice, which is not standard-

ized for correctness of content or delivery of the message.

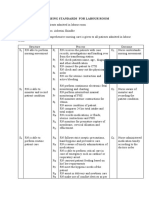

Many EDs now have discharge instruction software pro- Figure.

grams that generate patient visit information and discharge Discharge instructions included 3 brief messages.

instructions. These systems allow the development of a

model whereby standardized injury prevention educational SUMMER SAFETY ALERT

messages can be included in ED discharge instructions. Drowning happens quickly and quietly. The risk of drowning is greater during

An important first step in developing a strategy for the summer months. Take time now to be prepared. Here are three things you

can do that will help keep you, your family, and friends safe when you are out

educational interventions would be to determine whether on the water.

parents value this education. We elected to use drowning 1. Wear a life vest.

prevention as a model for injury prevention education in Check that everyone in your family has a life vest. Make sure it fits. There

are many styles of life vests to buy at marine supply or sporting goods

the ED setting. The goal of this study was to distribute stores. Many life vests are low-cost and look good. Or you can ask someone

standardized injury prevention information to ED parents to give your child a life vest as a gift.

and to determine whether they recalled the information Tips on when to wear a life vest:

• Young children need to wear life vests when they play in or near the

and perceived the advice as useful in the context of an ED water, on docks, and in inner tubes, rafts, or boats.

visit for another problem. • Teens and adults need to wear life vests in inner tubes, rafts, or boats,

especially small boats.

2. Swim in lifeguarded areas.

M AT E R I A L S A N D M E T H O D S No matter how well you can swim, cold, deep, or moving water is

dangerous. It is easy to be fooled by the water. So swim in a lifeguarded

The setting was the ED at a large, pediatric tertiary referral area or wear a life vest when swimming in a lake, river, or salt water.

3. Don’t drink alcohol when you are out on the water.

and teaching hospital with 23,978 ED visits in 1999; the Never allow or use alcohol while swimming or when out in a boat. It’s just

admission rate was 24%. Sponsor mix for the patient pop- like drinking and driving, but the effects of alcohol are even worse when you

ulation was 36% Medicaid, less than 1% Medicare, 5% are on or in the water.

self-pay, and 13% health maintenance organization/pre- To get your free water safety packet and children’s “tattoos,” call Children’s

Resource Line at 206-526-2500, extension 4.

ferred provider organization (HMO/PPO). All discharged

APRIL 2001 37:4 ANNALS OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE 3 8 3

DROWNING PREVENTION AND CHILDREN

Quan et al

home or could not come to the telephone, if the number versus 84%), median child age (3.6 versus 4.0 years), diag-

given in the ED did not reach the correct family, or if the nostic category (15% infection, 31% other medical, 32%

parents could not speak sufficient English. There was no trauma, 22% other versus 16% infection, 32% other medi-

inducement for participation. cal, 28% trauma, 24% other), proportion male (57% versus

The telephone survey had 27 structured questions; 9 56%), proportion that had a laboratory test (24% versus

of these evaluated the injury prevention messages. The 24%), proportion that had no intramuscular medications

survey took approximately 5 minutes to complete. The (98% versus 98%), no intravenous medications (90% ver-

protocol for this study was approved by the state’s and sus 92%), or no oral medications (85% versus 87%).

hospital’s institutional review boards. Nearly all parents (599/619, [97%]) recalled receiving

We determined the patient and visit characteristics for written discharge instructions, and another 20 recalled

patients discharged from the ED during the study period. the instructions when they were reminded what they

For each patient we determined the following: sex, age, looked like. Of the 619 parents who recalled receiving

visit date, day of the week, duration of ED visit, severity of written discharge instructions, 309 (50%) recalled re-

ED visit, diagnosis category, and whether or not the ceiving a water safety alert with the discharge instructions.

patient received any laboratory tests, radiologic tests, intra- When asked without prompting what the message was

venous medications, intramuscular medications, or oral about, 41% recalled a message about life vests, 25% re-

medications. called a message about drowning risks, and 13% recalled

We compared the patient and visit characteristics of (1) a message about swimming. Many parents (253/619 [41%])

parents who were surveyed with those not surveyed, and reported that they already owned a life vest for a child. Of

(2) parents who rated the prevention materials useful with 155 parents who did not own a life vest and recalled in-

those who did not. Comparisons were made using t tests structions about life vests, 35% said they were considering

for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical vari- buying a life vest as a result of the information they re-

ables. We used Stata Statistical software (release 6.0, 1999; ceived. Most parents reported that receiving drowning

Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). prevention information in the ED was very useful (373/619

[60%]) or somewhat useful (171/619 [28%]).

R E S U LT S The 544 (88%) parents who rated the drowning pre-

vention messages as very or somewhat useful were com-

During the study period, 2,291 eligible patients younger pared with the 75 (12%) who rated them as little or no

than 20 years were discharged from the ED. Of these use. Using 13 variables (age, sex, date of visit, time of

patients, 1,785 families were telephoned, and 506 could visit, duration of visit, weekend visit, condition severity,

not be telephoned within the 2-week time constraint and diagnosis category, and whether or not the patient received

thus were never called. Of those called, 871 were not con- a radiologic test, laboratory test, or oral, intramuscular, or

tacted because of wrong numbers or no answer. Of the intravenous medication), forward stepwise logistic regres-

914 eligible parents/caregivers who were contacted, 115 sion identified no statistically significant associations

refused to participate, 119 had communication barriers, between any variable and parent rating of usefulness.

24 did not recall receiving instructions, 37 terminated the When asked for suggestions on how to best distribute

call partway through the conversation, and 619 completed water safety information to families, the ideas mentioned

the interview (response rate 35% [619/1,785] and com- most often by 391 parents were mailings (24%), television/

pletion rate 67.7% [619/914]).4 radio/newspapers (23%), physician’s office (19%), ED

The children of the 619 interviewed parents were com- waiting room (13%), school presentations (12%), and

pared with those of the 1,672 parents who were eligible swimming lessons (8%).

but not interviewed. Median date of ED visit was 4 days

later for those interviewed (P<.001), the interviewed DISCUSSION

parents were less likely to have visited on a weekend

(30% versus 37%, P=.001), and the interviewed parents This study showed that parents perceived injury preven-

were more likely to have had a radiologic procedure (26% tion education in the ED as useful. Parent rating of useful-

versus 21%, P=.02). The interviewed and not interviewed ness was unrelated to any visit factors, including the time of

parents did not differ significantly (P>.05) in regard to day, day of week, diagnostic category, number of laboratory

median hour of arrival (5 PM versus 6 PM), median duration or radiologic tests, number of therapeutic interventions, or

of visit (103 versus 103 minutes), low visit severity (80% length or patient severity for the ED visit. Moreover, nearly

3 8 4 ANNALS OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE 37:4 APRIL 2001

DROWNING PREVENTION AND CHILDREN

Quan et al

half of the parents who recalled receiving the water safety there was no reason to believe that their responses would

information were able to state 1 to 2 weeks later that the differ. We did not assess receptivity to the prevention in-

primary prevention message was about life vests. formation among non–English-speaking families, and

Parent recall and valuing of the drowning prevention thus these results may not apply to non–English-speaking

information does not necessarily ensure that change will families.

occur. A limitation of this study is that it measured ex- Injury prevention should be provided to families from

pressed opinions about advice but did not measure any multiple sources.8 Reliance on primary care providers for

action. However, parents who recalled the water safety injury prevention education is problematic; many patients

information contemplated changing their behaviors based and families do not regularly visit their primary care pro-

on the prevention message; 35% of those who did not own a viders, especially once children reach school age. In addi-

life vest reported that they would consider buying a life vest. tion, many primary care providers have not been trained

Further studies should determine whether ED-based pre- in injury prevention, and increasing numbers of injury

vention advice can change behavior and prevent injuries. prevention issues compete for practioners’ limited patient

A large proportion of ED adult patients are functionally time. Even in the high-risk drowning region of Los Angeles,

illiterate, and therefore our written instructions may have CA, only a third of pediatricians provide drowning pre-

been useless to some parents.5 The illiteracy rate in our vention counseling.9 The ED represents an important

population is unknown but may explain some refusals additional setting for health care providers to provide

and reported lack of recall and usefulness. Our prevention prevention information to families.

materials were written at the recommended sixth-grade The role of the ED in injury prevention has been

reading level. Austin et al6 demonstrated that illustrations envisioned as a surveillance tool but this role can be

increased patient understanding of discharge instructions. expanded.8,10 This study showed that families find injury

When questioned about how to improve the instructions, prevention information useful and can recall the informa-

many surveyed parents in our study suggested including tion even when provided in the context of an unrelated

illustrations. ED visit. New technologies coupled with patient interest

We specifically did not ask ED staff to review the water in health information allow us to develop, without adding

safety messages with the families because we sought to burden to ED staff, the ED as an injury prevention resource

deliver them in a realistic ED setting where staff members and educational setting for large numbers of patients.

would inconsistently review them with parents depending

on time constraints and other demands. Isaacman et al7 We thank Kathy Williams, Washington State Department of Health, Jacque Jacobs, Jill

Baullinger, the physicians, nurses, and registrars of Children’s Emergency Services for

found that giving both verbal and computerized instruc- their help with this study.

tions led to better patient recall than giving only comput-

erized instructions. Further studies should identify ways

REFERENCES

to increase patient/parent recall and follow-through on

1. Coffman S, Martin V, Prill N, et al. Perceptions, safety behaviors, and learning needs of par-

injury prevention messages given in the ED. ents of children brought to an emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 1998;24:133-139.

The recall of our study population may be high because 2. Kruesi MJ, Grossman J, Pennington JM, et al. Suicide and violence prevention: parent edu-

parents were surveyed within 2 weeks of their ED visit. cation in the emergency department. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:250-255.

However, the interval between visit and survey was longer 3. Dunn KA, Cline DM, Grant T, et al. Injury prevention instruction in the emergency depart-

than other studies of ED discharge instruction recall.5-7 ment [see comments]. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:1280-1285.

Parent recall of the water safety messages was elicited 4. Lehman DR. Market Research and Analysis. Homewood, IL: Irwin; 1989.

without prompting. It is possible, however, that parents 5. Jolly BT, Scott JL, Sanford SM. Simplification of emergency department discharge instruc-

tions improves patient comprehension. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;26:443-446.

remembered these water safety messages from ongoing

6. Austin PE, Matlack R II, Dunn KA, et al. Discharge instructions: do illustrations help our

drowning prevention activities in the region. pateints understand them? Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25:317-320.

The failure to interview the majority of eligible parents 7. Isaacman DJ, Purvis K, Gyuro J, et al. Standardized instructions: do they improve communi-

is a limitation of this study. However, exclusion of Spanish- cation of discharge information from the emergency department? Pediatrics. 1992;89(6 Pt

speaking families excluded only a small percentage of our 2):1204-1208.

patients; in 1998, the ED used Spanish interpreters for 8. Bonnie R, Fulco C, Liverman C. Reducing the Burden of Injury. Washington, DC: National

Academy Press; 1999.

688 families. Although not all families of discharged

9. Barkin S, Gelberg L. Sink or swim—clinicians don’t often counsel on drowning prevention.

patients were surveyed, the analyses of patient age, gen- Pediatrics. 1999;104(5 Pt 2):1217-1219.

der, visit, diagnostic, and therapeutic variables showed 10. Hargarten SW, Karlson T. Injury control. A crucial aspect of emergency medicine. Emerg

the surveyed and unsurveyed groups were similar; thus, Med Clin North Am. 1993;11:255-262.

APRIL 2001 37:4 ANNALS OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE 3 8 5

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Common Problems in the Newborn Nursery: An Evidence and Case-based GuideDari EverandCommon Problems in the Newborn Nursery: An Evidence and Case-based GuideGilbert I. MartinBelum ada peringkat

- Ongoing Pediatric Health Care For The Child Who Has Been MaltreatedDokumen18 halamanOngoing Pediatric Health Care For The Child Who Has Been MaltreatedJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- The Pool Safety Resource: The Commonsense Approach to Keeping Children Safe Around WaterDari EverandThe Pool Safety Resource: The Commonsense Approach to Keeping Children Safe Around WaterBelum ada peringkat

- Pediatric Disaster Preparedness: Unique Needs of ChildrenDokumen16 halamanPediatric Disaster Preparedness: Unique Needs of ChildrenCris TobalBelum ada peringkat

- Management of Pediatric Trauma: PediatricsDokumen8 halamanManagement of Pediatric Trauma: PediatricsRIGMENBelum ada peringkat

- Child Life ArticleDokumen10 halamanChild Life ArticleGlody VuangaBelum ada peringkat

- Review Research Paper Medico-Legal Aspect of Pregnancy and Delivery: A Critical Case ReviewDokumen7 halamanReview Research Paper Medico-Legal Aspect of Pregnancy and Delivery: A Critical Case ReviewVlynBelum ada peringkat

- Principles of Disaster Planning for the Pediatric PopulationDokumen14 halamanPrinciples of Disaster Planning for the Pediatric PopulationCris TobalBelum ada peringkat

- 2015 Management of Ingested Foreign Bodies in Children - A Clinical Report of The NASPGHAN Endoscopy CommitteeDokumen13 halaman2015 Management of Ingested Foreign Bodies in Children - A Clinical Report of The NASPGHAN Endoscopy CommitteeCarlos CuadrosBelum ada peringkat

- Health Maintenance in School-Aged Children: Part I. History, Physical Examination, Screening, and ImmunizationsDokumen6 halamanHealth Maintenance in School-Aged Children: Part I. History, Physical Examination, Screening, and ImmunizationsPhilippe Ceasar C. BascoBelum ada peringkat

- Peds 2022057010Dokumen23 halamanPeds 2022057010hb75289kyvBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding Vaccination: Benefits, Risks and PrejudicesDokumen17 halamanUnderstanding Vaccination: Benefits, Risks and PrejudicesJoshua ValledorBelum ada peringkat

- Jr. Pediatrics 2021Dokumen31 halamanJr. Pediatrics 2021cdsaludBelum ada peringkat

- Peds 2022057010Dokumen24 halamanPeds 2022057010aulia lubisBelum ada peringkat

- 2012 IDF Guide For Nurses FINALDokumen60 halaman2012 IDF Guide For Nurses FINALkitsilcBelum ada peringkat

- Freedom Vs ControlDokumen25 halamanFreedom Vs Controlapi-315145911100% (1)

- Pediatric Healthcare ToolkitDokumen48 halamanPediatric Healthcare ToolkitJesse M. Massie100% (1)

- PediatricsDokumen10 halamanPediatricsapi-253312159Belum ada peringkat

- 7.delirium Knowledge, Self-Confidence, and Attitude in Pediatric IntensiveDokumen6 halaman7.delirium Knowledge, Self-Confidence, and Attitude in Pediatric IntensivemarieBelum ada peringkat

- Pediatric Trauma Life Support 3e Update 2017 FINALDokumen21 halamanPediatric Trauma Life Support 3e Update 2017 FINALAnita MacdanielBelum ada peringkat

- Education For Parents Regarding Choking Prevention and Handling On Children: A Scoping ReviewDokumen8 halamanEducation For Parents Regarding Choking Prevention and Handling On Children: A Scoping ReviewIJPHSBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing Care of a Patient with Epidural HematomaDokumen88 halamanNursing Care of a Patient with Epidural HematomaRyanAgootBelum ada peringkat

- Talking with Parents about Vaccines for Infants: Strategies for Health Care ProfessionalsDokumen4 halamanTalking with Parents about Vaccines for Infants: Strategies for Health Care ProfessionalslocusBelum ada peringkat

- Has 302255Dokumen2 halamanHas 302255api-197110397Belum ada peringkat

- Ar 12814Dokumen131 halamanAr 12814Residencia PediatriaBelum ada peringkat

- Salud Oral en NiñosDokumen8 halamanSalud Oral en NiñosNayra Nieves Sanchez AyalaBelum ada peringkat

- Pre-hospital Management of Febrile Seizures in ChildrenDokumen5 halamanPre-hospital Management of Febrile Seizures in Childrenchaz5727xBelum ada peringkat

- Nonaccidental Pediatric Trauma - Which Traditional Clues Predict AbuseDokumen5 halamanNonaccidental Pediatric Trauma - Which Traditional Clues Predict AbuseolivierdomengeBelum ada peringkat

- Geriatric Preoperative Optimization: A ReviewDokumen10 halamanGeriatric Preoperative Optimization: A Reviewalejandro montesBelum ada peringkat

- Children: Delivering Pediatric Palliative Care: From Denial, Palliphobia, Pallilalia To PalliactiveDokumen13 halamanChildren: Delivering Pediatric Palliative Care: From Denial, Palliphobia, Pallilalia To PalliactiveKostas LiqBelum ada peringkat

- Adverse Events in The Neonatal Intensive Care UnitDokumen12 halamanAdverse Events in The Neonatal Intensive Care UnitevangelinasBelum ada peringkat

- Nelson 20th MCQDokumen593 halamanNelson 20th MCQcharlesy T89% (19)

- Pediatrics questions and answers - The field of pediatricsDokumen433 halamanPediatrics questions and answers - The field of pediatricsShashank MisraBelum ada peringkat

- PlyometriaDokumen9 halamanPlyometriafrancovet27Belum ada peringkat

- Maltreatment of Children With DisabilitiesDokumen13 halamanMaltreatment of Children With DisabilitiesCatarina GrandeBelum ada peringkat

- Test Bank For Lemone and Burkes Medical Surgical Nursing 7th by BauldoffDokumen48 halamanTest Bank For Lemone and Burkes Medical Surgical Nursing 7th by Bauldoffrobertrichardsonjxacntmdqf100% (25)

- 1 CombineDokumen52 halaman1 Combineasal bakhtyariBelum ada peringkat

- 361 FullDokumen7 halaman361 FullnissashiblyBelum ada peringkat

- AHOGAMIENTODokumen13 halamanAHOGAMIENTOKim RamirezBelum ada peringkat

- Baker 2022Dokumen11 halamanBaker 2022ahmad azhar marzuqiBelum ada peringkat

- Pedpallcare ResidentsoverviewDokumen54 halamanPedpallcare ResidentsoverviewSvitlana YastremskaBelum ada peringkat

- Approach To Emergency PatientDokumen18 halamanApproach To Emergency PatientJuan Pablo Gallardo ContrerasBelum ada peringkat

- 1 s2.0 S0190740915000870 Main PDFDokumen7 halaman1 s2.0 S0190740915000870 Main PDFYusranBelum ada peringkat

- Blueprints Pediatrics 6ed 2013 PDFDokumen406 halamanBlueprints Pediatrics 6ed 2013 PDFGiorgos Gritzelas90% (10)

- Vanantwerp 1995Dokumen5 halamanVanantwerp 1995SIRIUS RTBelum ada peringkat

- 1377 FullDokumen23 halaman1377 FullPutri Wahyuni AllfazmyBelum ada peringkat

- The Educational Intervention GRIEV - INGDokumen7 halamanThe Educational Intervention GRIEV - INGJESSICA ORTEGABelum ada peringkat

- Teaching Treatment of MildDokumen4 halamanTeaching Treatment of MildAldy Setiawan PutraBelum ada peringkat

- Parental Attitudes Toward Child Vaccination in Erbil, IraqDokumen10 halamanParental Attitudes Toward Child Vaccination in Erbil, IraqkrishnasreeBelum ada peringkat

- Prenatal Consultation Practices at The Border of Viability: A Regional SurveyDokumen9 halamanPrenatal Consultation Practices at The Border of Viability: A Regional SurveyAnnitaCristalBelum ada peringkat

- Pediatric Septic ShockDokumen24 halamanPediatric Septic ShockBRENDA AMAROBelum ada peringkat

- Nast - Pages From P.S. Ocampo Handbook of Well Child Care - 132Dokumen11 halamanNast - Pages From P.S. Ocampo Handbook of Well Child Care - 132einjohnmBelum ada peringkat

- 2019 Unique Needs of The AdolescentDokumen14 halaman2019 Unique Needs of The AdolescentAlexis Ormeño JulcaBelum ada peringkat

- The Battered Baby: I - GrifithsDokumen3 halamanThe Battered Baby: I - GrifithsMuhammad Zaid SahakBelum ada peringkat

- 5th Annual Pediatric Palliative Oncology SymposiumDokumen5 halaman5th Annual Pediatric Palliative Oncology SymposiumGerardo CastellanosBelum ada peringkat

- Dieckmann Et Al The PAT 1 PDFDokumen4 halamanDieckmann Et Al The PAT 1 PDFLydia ElimBelum ada peringkat

- Pediatric Care Recommendations For Freestanding Urgent Care FacilitiesDokumen6 halamanPediatric Care Recommendations For Freestanding Urgent Care FacilitiesadrianBelum ada peringkat

- Children With Medical ComplexityDokumen10 halamanChildren With Medical ComplexityAlmiro Cruz FilhoBelum ada peringkat

- CEE-154/NUTR-204: Fall 2012: Case Reports, Case Series and Cross-Sectional StudiesDokumen35 halamanCEE-154/NUTR-204: Fall 2012: Case Reports, Case Series and Cross-Sectional StudiesJoachim NiiBelum ada peringkat

- 3 TceDokumen11 halaman3 TceRosalía PattyBelum ada peringkat

- Four Humors Theory in Unani MedicineDokumen4 halamanFour Humors Theory in Unani MedicineJoko RinantoBelum ada peringkat

- A History of Prostate Cancer Cancer, Men and Medicine First Edition PDFDokumen248 halamanA History of Prostate Cancer Cancer, Men and Medicine First Edition PDFMarcela Osorio DugandBelum ada peringkat

- Screening For Breast CancerDokumen20 halamanScreening For Breast CancerqalbiBelum ada peringkat

- 2018 Conference AbstractsDokumen155 halaman2018 Conference AbstractsBanin AbadiBelum ada peringkat

- Curs DR PellegrinoDokumen1 halamanCurs DR PellegrinorfandreiBelum ada peringkat

- Patient Care Assistant ResumeDokumen8 halamanPatient Care Assistant Resumeafazakemb100% (2)

- Organization of NICU ServicesDokumen45 halamanOrganization of NICU ServicesMonika Bagchi84% (64)

- Postterm Pregnancy - UpToDateDokumen16 halamanPostterm Pregnancy - UpToDateCarlos Jeiner Díaz SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- Immediate Dental Implant Placement Into Infected vs. Non-Infected Sockets: A Meta-AnalysisDokumen7 halamanImmediate Dental Implant Placement Into Infected vs. Non-Infected Sockets: A Meta-Analysismarlene tamayoBelum ada peringkat

- Surgical Site InfectionDokumen7 halamanSurgical Site InfectionCaxton ThumbiBelum ada peringkat

- Prescribing Information: 1. Name of The Medicinal ProductDokumen5 halamanPrescribing Information: 1. Name of The Medicinal Productddandan_20% (1)

- Malnutrition in Critical Illness and Beyond A Narrative Review PDFDokumen9 halamanMalnutrition in Critical Illness and Beyond A Narrative Review PDFEsteban DavidBelum ada peringkat

- Autism AssessmentDokumen37 halamanAutism AssessmentRafael Martins94% (16)

- Terjemahan Refarat AyuDokumen4 halamanTerjemahan Refarat Ayu'itii DiahBelum ada peringkat

- CentralVenousCatheters PDFDokumen77 halamanCentralVenousCatheters PDFHarold De Leon Malang100% (1)

- Business Plan Analysis - 08 1: SFHN/SJ&G Oxalepsy (Oxcarbazipine300 & 600 MG)Dokumen63 halamanBusiness Plan Analysis - 08 1: SFHN/SJ&G Oxalepsy (Oxcarbazipine300 & 600 MG)Muhammad SalmanBelum ada peringkat

- Complications After CXLDokumen3 halamanComplications After CXLDr. Jérôme C. VryghemBelum ada peringkat

- Insights Into Veterinary Endocrinology - Diagnostic Approach To PU - PD - Urine Specific GravityDokumen4 halamanInsights Into Veterinary Endocrinology - Diagnostic Approach To PU - PD - Urine Specific GravityHusnat hussainBelum ada peringkat

- Agni Dagdha. Group-T Patients Were Treated With Indigenous Drugs and Group-C PatientsDokumen14 halamanAgni Dagdha. Group-T Patients Were Treated With Indigenous Drugs and Group-C PatientsKrishnaBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing Standards for Labour RoomDokumen3 halamanNursing Standards for Labour RoomRenita ChrisBelum ada peringkat

- TOPIC 3.A Bag TechniqueDokumen38 halamanTOPIC 3.A Bag TechniqueJayrelle D. Safran100% (1)

- Geriatric Medicine Certification Examination Blueprint - ABIMDokumen7 halamanGeriatric Medicine Certification Examination Blueprint - ABIMabimorgBelum ada peringkat

- Barge Clinic Visit Report SummaryDokumen42 halamanBarge Clinic Visit Report SummaryNicoMichaelBelum ada peringkat

- Changes in Central Corneal Thickness in Healthy Pregnant Women-A Clinical StudyDokumen3 halamanChanges in Central Corneal Thickness in Healthy Pregnant Women-A Clinical StudyIJAR JOURNALBelum ada peringkat

- NP 5 Set BBBBBDokumen31 halamanNP 5 Set BBBBBGo IdeasBelum ada peringkat

- German Gov't Bombshell - Alarming Number of Vaccinated Are Developing AIDS' - News PunchDokumen8 halamanGerman Gov't Bombshell - Alarming Number of Vaccinated Are Developing AIDS' - News PunchKarla VegaBelum ada peringkat

- Green White Minimalist Modern Real Estate PresentationDokumen8 halamanGreen White Minimalist Modern Real Estate Presentationapi-639518867Belum ada peringkat

- Kuisioner Nutrisi Mini Nutritional AssessmentDokumen1 halamanKuisioner Nutrisi Mini Nutritional AssessmentNaufal AhmadBelum ada peringkat

- AssociationBetweenBRAFV600EMutationand MortalityDokumen9 halamanAssociationBetweenBRAFV600EMutationand MortalityMade RusmanaBelum ada peringkat

- 4-5TH JANUARY 2023: Organized byDokumen3 halaman4-5TH JANUARY 2023: Organized byvivien kate perixBelum ada peringkat

- Summary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDari EverandSummary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (9)

- Rapid Weight Loss Hypnosis: How to Lose Weight with Self-Hypnosis, Positive Affirmations, Guided Meditations, and Hypnotherapy to Stop Emotional Eating, Food Addiction, Binge Eating and MoreDari EverandRapid Weight Loss Hypnosis: How to Lose Weight with Self-Hypnosis, Positive Affirmations, Guided Meditations, and Hypnotherapy to Stop Emotional Eating, Food Addiction, Binge Eating and MorePenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (17)

- Rewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and WorryDari EverandRewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and WorryPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (157)

- The Somatic Psychotherapy Toolbox: A Comprehensive Guide to Healing Trauma and StressDari EverandThe Somatic Psychotherapy Toolbox: A Comprehensive Guide to Healing Trauma and StressBelum ada peringkat

- Summary of The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk MDDari EverandSummary of The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk MDPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (167)

- The Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingDari EverandThe Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- EVERYTHING/NOTHING/SOMEONE: A MemoirDari EverandEVERYTHING/NOTHING/SOMEONE: A MemoirPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (45)

- The Upward Spiral: Using Neuroscience to Reverse the Course of Depression, One Small Change at a TimeDari EverandThe Upward Spiral: Using Neuroscience to Reverse the Course of Depression, One Small Change at a TimePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (140)

- Critical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsDari EverandCritical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (38)

- Overcoming Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts: A CBT-Based Guide to Getting Over Frightening, Obsessive, or Disturbing ThoughtsDari EverandOvercoming Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts: A CBT-Based Guide to Getting Over Frightening, Obsessive, or Disturbing ThoughtsPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (48)

- Feel the Fear… and Do It Anyway: Dynamic Techniques for Turning Fear, Indecision, and Anger into Power, Action, and LoveDari EverandFeel the Fear… and Do It Anyway: Dynamic Techniques for Turning Fear, Indecision, and Anger into Power, Action, and LovePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (249)

- An Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyDari EverandAn Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1)

- BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER: Help Yourself and Help Others. Articulate Guide to BPD. Tools and Techniques to Control Emotions, Anger, and Mood Swings. Save All Your Relationships and Yourself. NEW VERSIONDari EverandBORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER: Help Yourself and Help Others. Articulate Guide to BPD. Tools and Techniques to Control Emotions, Anger, and Mood Swings. Save All Your Relationships and Yourself. NEW VERSIONPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (24)

- My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesDari EverandMy Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (70)

- Somatic Therapy Workbook: A Step-by-Step Guide to Experiencing Greater Mind-Body ConnectionDari EverandSomatic Therapy Workbook: A Step-by-Step Guide to Experiencing Greater Mind-Body ConnectionBelum ada peringkat

- Heal the Body, Heal the Mind: A Somatic Approach to Moving Beyond TraumaDari EverandHeal the Body, Heal the Mind: A Somatic Approach to Moving Beyond TraumaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (56)

- The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDari EverandThe Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (2)

- Triggers: How We Can Stop Reacting and Start HealingDari EverandTriggers: How We Can Stop Reacting and Start HealingPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (58)

- Binaural Beats: Activation of pineal gland – Stress reduction – Meditation – Brainwave entrainment – Deep relaxationDari EverandBinaural Beats: Activation of pineal gland – Stress reduction – Meditation – Brainwave entrainment – Deep relaxationPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (9)

- Emotional Detox for Anxiety: 7 Steps to Release Anxiety and Energize JoyDari EverandEmotional Detox for Anxiety: 7 Steps to Release Anxiety and Energize JoyPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (6)

- The Anatomy of Loneliness: How to Find Your Way Back to ConnectionDari EverandThe Anatomy of Loneliness: How to Find Your Way Back to ConnectionPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (162)

- Winning the War in Your Mind: Change Your Thinking, Change Your LifeDari EverandWinning the War in Your Mind: Change Your Thinking, Change Your LifePenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (558)

- The Complex PTSD Workbook: A Mind-Body Approach to Regaining Emotional Control & Becoming WholeDari EverandThe Complex PTSD Workbook: A Mind-Body Approach to Regaining Emotional Control & Becoming WholePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (49)

- Fighting Words Devotional: 100 Days of Speaking Truth into the DarknessDari EverandFighting Words Devotional: 100 Days of Speaking Truth into the DarknessPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (6)

- Anxious for Nothing: Finding Calm in a Chaotic WorldDari EverandAnxious for Nothing: Finding Calm in a Chaotic WorldPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (1242)