Best-Practice Care Pathway For Improving Management of Mastitis and Breast Abscess

Diunggah oleh

Egy SeptiansyahJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Best-Practice Care Pathway For Improving Management of Mastitis and Breast Abscess

Diunggah oleh

Egy SeptiansyahHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Original article

Best-practice care pathway for improving management of

mastitis and breast abscess

N. Patani1 , F. MacAskill1 , S. Eshelby1 , A. Omar1 , A. Kaura1 , K. Contractor1 , P. Thiruchelvam1,4 ,

S. Curtis2 , J. Main3 , D. Cunningham1 , K. Hogben1 , R. Al-Mufti1 , D. J. Hadjiminas1,4

and D. R. Leff1,4

1

Breast Unit, 2 Department of Microbiology and 3 Department of Infectious Diseases, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, and 4 Department of

Surgery and Cancer, Imperial College, London, UK

Correspondence to: Mr D. R. Leff, Department of Surgery and Cancer, BioSurgery and Surgical Technology, 10th Floor, QEQM Wing, St Mary’s Hospital,

London W2 1NY, UK (e-mail: d.leff@imperial.ac.uk)

Background: Surgical subspecialization has resulted in mastitis and breast abscesses being managed

with unnecessary admission to hospital, prolonged inpatient stay, variable antibiotic prescribing, incision

and drainage rather than percutaneous aspiration, and loss to specialist follow-up. The objective was

to evaluate a best-practice algorithm with the aim of improving management of mastitis and breast

abscesses across a multisite NHS Trust. The focus was on uniformity of antibiotic prescribing, ultrasound

assessment, admission rates, length of hospital stay, intervention by aspiration or incision and drainage,

and specialist follow-up.

Methods: Management was initially evaluated in a retrospective cohort (phase I) and subsequently

compared with that in two prospective cohorts after introduction of a breast abscess and mastitis pathway.

One prospective cohort was analysed immediately after introduction of the pathway (phase II), and the

second was used to assess the sustainability of the quality improvements (phase III). The overall impact

of the pathway was assessed by comparing data from phase I with combined data from phases II and III;

results from phases II and III were compared to judge sustainability.

Results: Fifty-three patients were included in phase I, 61 in phase II and 80 in phase III. The

management pathway and referral pro forma improved compliance with antibiotic guidelines from 34 per

cent to 58⋅2 per cent overall (phases II and III) after implementation (P = 0⋅003). The improvement was

maintained between phases II and III (54 and 61 per cent respectively; P = 0⋅684). Ultrasound assessment

increased from 38 to 77⋅3 per cent overall (P < 0⋅001), in a sustained manner (75 and 79 per cent in phases

II and III respectively; P = 0⋅894). Reductions in rates of incision and drainage (from 8 to 0⋅7 per cent

overall; P = 0⋅007) were maintained (0 per cent in phase II versus 1 per cent in phase III; P = 0⋅381).

Specialist follow-up improved consistently from 43 to 95⋅7 per cent overall (P < 0⋅001), 92 per cent in

phase II and 99 per cent in phase III (P = 0⋅120). Rates of hospital admission and median length of stay

were not significantly reduced after implementation of the pathway.

Conclusion: A standardized approach to mastitis and breast abscess reduced undesirable practice

variation, with sustained improvements in process and patient outcomes.

Presented to a meeting of the Association of Breast Surgery, Manchester, UK, May 2016, and a meeting of the

Association of Breast Surgery, Birmingham, UK, June 2018; published in abstract form as Eur J Surg Oncol 2016;

42(Suppl 5), S4 and Eur J Surg Oncol 2018; 44(6): 862–863.

Paper accepted 7 May 2018

Published online in Wiley Online Library (www.bjs.co.uk). DOI: 10.1002/bjs.10919

Introduction nipple trauma, which weakens the barrier function of the

skin and permits entry of bacteria1 . Non-lactating women

Mastitis refers to inflammation of the breast, the aetiology with other diagnoses such as duct ectasia can also develop

of which is most commonly infectious, but can occasionally periductal mastitis. This has been associated with squa-

be granulomatous. Infection of the breast typically affects mous metaplasia impeding clearance, resulting in obstruc-

lactating women and has been linked to milk stagnation and tive ductopathy2 . An abscess develops when the infected

© 2018 BJS Society Ltd BJS

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

N. Patani, F. MacAskill, S. Eshelby, A. Omar, A. Kaura, K. Contractor et al.

tissue is localized and purulent material becomes walled off. out of hours, may result in undesirable practice variation,

The pathogenesis most frequently involves bacterial infec- suboptimal management and unnecessary healthcare

tion following skin colonization with Staphylococcus aureus. costs23 . Against this background, the objective of this work

Less commonly, coagulase-negative staphylococci and/or was to evaluate practices in the management of breast

anaerobic organisms are isolated, particularly in smokers3 . sepsis across a four-site hospital network; to develop a

Lactational mastitis and periductal mastitis occur rela- best-practice care pathway algorithm for mastitis and

tively frequently, with reported rates of 5–10 per cent4 – 6 , breast abscess; and, finally, to monitor pathway implemen-

and a similar proportion of these progress to abscess for- tation and its impact on patient outcomes and key process

mation. This amounts to a considerable disease burden measures.

and healthcare costs4,5 . The magnitude of these remains

unknown, but will be informed by data from national qual-

Methods

ity improvement initiatives, such as the breast surgery work

stream Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT)7 . A retrospective audit (phase I) was undertaken between

Women with lactational or periductal mastitis, includ- January 2010 and December 2011 to evaluate the man-

ing those with abscess, without systemic symptoms, skin agement of patients diagnosed with mastitis and/or breast

necrosis or immunocompromise, can be discharged safely abscess presenting acutely to a multisite NHS Trust. The

on appropriate oral antibiotics. An expedited outpatient Trust’s database was searched using the terms ‘mastitis’

assessment in a breast clinic and image-guided interven- and/or ‘breast abscess’, to capture patients presenting with

tion where appropriate should follow1,8 – 11 . Admission to these diagnoses over a 2-year interval. Data were collected

hospital is best avoided in the postpartum period as it sep- by review of hospital records, focusing on the clerking case

arates mother and baby unnecessarily. Simple analgesia notes, imaging, pathology and microbiology reports, phar-

and systemic antibiotic therapy may be sufficient treatment macy records, and operation notes where applicable. The

for uncomplicated mastitis. Early ultrasound-guided ther- key information included adherence to antibiotic guide-

apeutic aspiration is recommended for abscesses to relieve lines, rates of hospital admission and length of inpatient

symptoms, effectively drain collections with minimal scar- stay. Use of breast ultrasound imaging and intervention by

ring and breast deformation, and provide microbiology aspiration, frequency of operative incision and drainage,

samples to allow rationalization of empirical antibiotics. involvement of breast surgeons and rates of specialist breast

Biopsies can also be taken for histology if granulomatous surgical follow-up were also monitored. Data were col-

inflammation or malignancy is suspected12 – 16 . Although lected using standard templates and entered into a secure

surgical incision and drainage represents the archetypal electronic database. The audit was registered with the Trust

treatment, in contemporary practice this is increasingly (identifier 047529) and the staged results presented at clin-

reserved for situations in which image-guided aspiration is ical governance meetings.

not available within an appropriate time frame, has been

ineffective for large abscesses, or there is necrotizing infec-

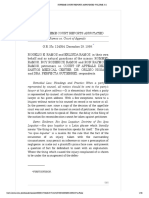

tion requiring formal debridement4,17 – 20 . The Guidelines Development of mastitis and breast abscess

and Audit Implementation Network21 and the National

protocol

Institute for Health and Care Excellence22 have published After evaluation of existing processes and key outcome

recommendations for the management of breast abscess measures for patients presenting with mastitis and/or

and mastitis, which include the timing and choice of antibi- breast abscess, a referral pro forma and best-practice

otic therapy, use of ultrasound-guided needle aspiration, management algorithm were developed. This involved

and the need for specialist referral and follow-up. consultation with surgeons, radiologists, microbiologists

Major barriers to optimal management of women with and emergency physicians, using the Delphi method to

mastitis include the potentially limited experience of reach consensus24 . The subject was ratified by the hospitals

frontline healthcare providers owing to subspecialization, antibiotic review group, and the Trust’s quality and safety

inadequate access to interventional radiology, and inability review board. Local ethics committee approval was not

to access breast specialists out of hours. Despite published required for this process. The resulting breast abscess and

guidelines4,21,22 , recent data suggest that many surgical mastitis pathway (Fig. 1) was thereafter introduced across

units in the UK do not have clear protocols for treating the multisite NHS Trust in 2014.

breast infections referred to secondary care19 . The com- The purpose of the management algorithm was to

bination of local organizational and logistical factors, in equip non-specialists with an evidence-based decision tool

addition to patients presenting acutely to non-specialists regarding the clinical indications for hospital admission

© 2018 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Management of mastitis and breast abscess

Breast pain/erythema/swelling/discharge

Clinically well Clinically unwell?

Severe infection/sepsis (tachycardia, temperature > 38°C,

respiratory rate >20 per min)

or immunocompromised (steroids, HIV, chemotherapy,

Clinically apparent abscess low WCC)

or adverse local signs (spreading erythema, necrotizing

fasciitis)

Yes No or poor response to oral antibiotics

Drain Admit for treatment

Consider drainge +/– ultrasound Inform

guidance by surgical SpR or ED consultant In hours: breast SpR

Send aspirate for microscopy, culture and sensitivity Out of hours: general SpR

Consider EMLA cream before aspiration Investigations

Bloods tests including blood cultures

Breast ultrasound imaging if abscess suspected

Further management

Analgesia: paracetamol, ibuprofen Further management

Antibiotics Analgesia: paracetamol, ibuprofen

First line: oral co-amoxiclav 625 mg TDS for 10–14 days Antibiotics: i.v. ≥ 3 days, then oral. Total course 14 days

Second line/penicillin allergy/non-lactational mastitis: oral First line: i.v. co-amoxiclav 1.2 g TDS

clindamycin 300 mg QDS for 10–14 days Penicillin allergy: i.v. clindamycin 600–1200 mg QDS

If breastfeeding, MRSA-positive or fungal, consult Second line/MRSA-positive: i.v. vancomycin 1 g BD

microbiology If breastfeeding, MRSA-positive or fungal, consult

Lactational mastitis: encourage patient to ‘express breast, microbiology

heat and rest’ Incision and drainage for

Discharge home: clinically well patients do not require Abscess with failed needle aspiration

admission Skin necrosis

Fig. 1Breast abscess and mastitis pathway. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; WCC, white cell count; SpR, specialist registrar; ED,

emergency department; TDS, three times daily; QDS, four times daily; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; BD, twice

daily

and Trust antibiotic guidelines to minimize practice vari- occasions to account for rotating junior trainees in breast

ation. Patients could be triaged effectively, appropriate surgery, general surgery and emergency departments, and

initial treatment started, and breast specialists alerted by repeated again before further audit phases.

completion of the referral pro forma (Fig. S1, supporting

information). The completed pro formas were faxed to

Further audit of pathway implementation

the breast services booking office, centralized at one of

the hospitals. Patients were then contacted to arrange an A loop-closing audit25 was conducted between January

appointment with a breast surgeon and to undergo special- 2015 and February 2016 to reassess practice and determine

ist ultrasound assessment with aspiration if appropriate, improvements in the quality of care. The prospective audit

typically on the next working day. comprised two consecutive time intervals (Fig. 2); the first

The management pathway was uploaded on to the Trust’s (phase II) was undertaken between January 2015 and July

intranet and the referral pro forma was made available 2015, and the second (phase III) between August 2015 and

online across four teaching hospitals of the Trust. At each February 2016. Data were collected from all four centres

site, education and training sessions were undertaken to for patients with mastitis and/or breast abscess referred to

ensure that relevant accident and emergency staff, general either the on-call surgical team or breast services. On a

surgery teams and the breast unit administrative team daily basis, all general surgical admissions from the pre-

had familiarized themselves with the best-practice pathway ceding day were screened to identify women admitted

and were notified of critical changes in practice. Pathway with mastitis and breast abscess. Accident and emergency

education and training sessions were repeated on several records were also reviewed to identify patients diagnosed

© 2018 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

N. Patani, F. MacAskill, S. Eshelby, A. Omar, A. Kaura, K. Contractor et al.

Pathway Education and

introduction staff engagement

2014

Phase I Phase II Phase III

Retrospective audit Prospective audit Prospective audit

Jan 2010 to Dec 2011 Jan 2015 to Jul 2015 Aug 2015 to Feb 2016

n = 53 n = 61 n = 80

Sustained

improvement

Before pathway introduction After pathway introduction

Improvement

Fig. 2 Study design and analytical strategy

with mastitis and/or breast abscess who were discharged drainage, and specialist follow-up, were expressed as fre-

pending outpatient review; and uptake of the pro forma was quencies and analysed using the χ2 test. Duration of hos-

recorded. Pro formas faxed to the breast unit were similarly pital stay, presented as median (range), was analysed using

reviewed, and cross-referenced against accident and emer- the Mann–Whitney U test. For all analyses, P < 0⋅050 was

gency (outpatient managed) and general surgical (inpa- deemed statistically significant. Analyses were conducted

tient managed) records. The following data were collected: using SPSS® version 24 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

uptake of the pro forma, rates of hospital admission, com-

pliance with antibiotic policy, use of ultrasound assessment,

frequency of interventions such as percutaneous aspiration

and surgical drainage, and rates of specialist follow-up after Results

the acute phase. Data were collected as described for the Fifty-three patients were included in phase I, before imple-

retrospective audit. mentation of the breast abscess and mastitis pathway, and

61 and 80 patients in phases II and III respectively, after

introduction of the pathway.

Statistical analysis

Data from each phase of the study were analysed across

five key domains: compliance with antibiotic guidelines;

Antibiotic compliance

ultrasound assessment and aspiration rates; hospital admis-

sion and length of stay; operative incision and drainage Overall compliance with the antibiotic prescribing pol-

rates; and specialist follow-up. The retrospective audit data icy improved significantly following pathway implemen-

collected before instigation of the pathway (phase I) were tation from 34 per cent (18 of 53) to 58⋅2 per cent (82

compared with combined data from the two prospective of 141) (P = 0⋅003). Unavailable data (10 patients before

audit cycles (phases II and III). Further comparisons were and 26 after introduction of the pathway) were assumed

undertaken to determine when the improvement occurred to reflect non-compliance. After pathway implementation,

(phase I versus II and phase I versus III). To determine there was greater uniformity and a reduction in the range of

whether improvements in practice were sustained, direct antibiotics prescribed (Fig. 3; Table S1 and Fig. S2, support-

comparisons were made between the two prospective audits ing information). Improvements in practice were evident

(phase II versus III) (Fig. 2). Unavailable data were assumed in both prospective cohorts: 34 per cent in phase I versus

to reflect non-compliance with the management pathway 54 per cent in phase II (P = 0⋅049) and 61 per cent in phase

and/or Trust guidelines. Outcome measures, such as rates III (P = 0⋅003). Compliance with antibiotic guidelines was

of antibiotic use, hospital admission, operative incision and maintained (phase II versus III; P = 0⋅684).

© 2018 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Management of mastitis and breast abscess

80 Other antibiotic combinations incision and drainage was maintained following pathway

Co-amoxiclav implementation (phase II versus III; P = 0⋅381).

Not prescribed or unknown

60 Hospital admission and length of stay

Rates of hospital admission were reduced from 30 per cent

No. of patients

(16 of 53) to 20⋅6 per cent (29 of 141) following pathway

40 implementation, although this did not reach statistical

significance (P = 0⋅247). There were no significant differ-

ences in rates of admission between any of the phases (30

per cent in phase II and 14 per cent in phase III) (Table S1,

20 supporting information). When patients with unknown

admission status were excluded from the analysis, a statis-

tically significant reduction in admission rate was observed

in phase III (P = 0⋅018 versus phase I; P = 0⋅027 versus

0

Phase I Phase II Phase III phase II). Similarly, there was no change in median length

Before pathway After pathway introduction of hospital stay for patients admitted following pathway

introduction adoption: 2 (range 1–5) and 1 (1–6) days in phases I and

Fig. 3Impact of best-practice management pathway on antibiotic

II–III respectively (P = 0⋅079).

prescribing. Number of patients receiving first-line antibiotic

(co-amoxiclav), other antibiotics and where antibiotic

prescriptions were unknown or no antibiotics prescribed Follow-up

Rates of follow-up with breast specialists were substantially

Ultrasound assessment improved after pathway implementation, from 43 per cent

(23 of 53) to 95⋅7 per cent (135 of 141) (P < 0⋅001) (Fig. 4).

The assessment of women with mastitis and/or breast

Significant improvement was demonstrated both in phase

abscess using ultrasound imaging was markedly increased

II (92 versus 43 per cent in phase I; P < 0⋅001) and phase III

overall following pathway implementation from 38 per

cent (20 of 53) to 77⋅3 per cent (109 of 141) (P < 0⋅001),

and maintained between phase II and phase III (75 per

80 No follow-up

cent (46 of 61) versus 79 per cent (63 of 80) respectively; Specialist

P = 0⋅894). Unavailable data were assumed to reflect lack Unknown

of imaging (phase I, 13 patients; phase II, 9; phase III, 10).

60

Aspiration versus surgical drainage

No. of patients

The greater use of ultrasound assessment after intro-

duction of the pathway provided an opportunity for

image-guided intervention when appropriate, but rates 40

of aspiration did not change significantly: 23 per cent (12

of 53) in phase I, 25 per cent (15 of 61) in phase II and

21 per cent (15 of 80) in phase III (Table S1, supporting

information). 20

Although similar proportions of patients underwent

aspiration, the overall rate of surgical incision and drainage

under general anaesthesia was significantly reduced fol-

lowing pathway implementation from 8 per cent (4 of 53) 0

Phase I Phase II Phase III

to 0⋅7 per cent (1 of 141) (P = 0⋅007). This improvement

Before pathway After pathway introduction

was significant in phase II (0 per cent versus 8 per cent in introduction

phase I; P = 0⋅029), but not in phase III (1 per cent versus

8 per cent in phase I; P = 0⋅062). Attenuation in rates of Fig. 4 Impact of best-practice management pathway on follow-up

© 2018 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

N. Patani, F. MacAskill, S. Eshelby, A. Omar, A. Kaura, K. Contractor et al.

(99 versus 43 per cent in phase I; P < 0⋅001). The improve- important issue for the sustainability of quality improve-

ment was sustained (phase II versus III; P = 0⋅120). This ment endeavours.

was attributable to a reduction in the number of women The high turnover of frontline staff in emergency

who received no follow-up, were lost to follow-up or with services, general surgery and the breast unit itself

unknown follow-up status (Fig. 4; Table S1, supporting poses a threat to securing sustainability after the ini-

information). tial intervention30,32 – 35 . Change leaders need to engage

with new practitioners for targeted education and training.

This is both labour-intensive and impractical. Ideally,

Discussion

innovative strategies should be sought to facilitate rapid

The objective of the pathway was to improve the man- familiarization of incoming staff with best-practice clinical

agement of patients presenting with mastitis and/or breast pathways. These include system-based opportunities, such

abscess to a multisite hospital NHS Trust. A retrospective as introducing standardized online induction modules

audit identified significant practice variation and subopti- for new employees24 , linking breast-specific clerking pro

mal management, leading to inappropriate antibiotic pre- formas to the best-practice pathway using the electronic

scriptions and unnecessary hospital admissions. Rates of patient record36,37 , facilitating direct peer-to-peer han-

ultrasound assessment were low, and rates of operative inci- dover of conditions for which integrated management

sion and drainage were high, with inadequate involvement pathways exist38 , and reinforcing mechanisms to provide

of breast specialists and inconsistent follow-up. positive feedback and discourage non-compliant practice34 .

Prompt management and early intervention for masti- Although the present data support a considerable reduc-

tis and/or breast abscess has important implications for tion in hospital admission rates and length of stay follow-

patient outcome. Refractory or recurrent infection may be ing pathway implementation, these changes did not reach

associated with delayed diagnosis, suboptimal treatment, statistical significance. The observed reduction in hospi-

and contributory patient factors such as poor breastfeed- tal admission rates from 30 per cent in phase I to 14 per

ing technique, diabetes and smoking26 – 28 . Although there cent in phase III following pathway introduction is mean-

were no patients with inflammatory breast cancer in this ingful, but the appropriateness of an admission rate of 14

study, failing to involve breast specialists and to consider per cent for mastitis still has to be questioned. Future ini-

this important diagnosis can have profound clinical and tiatives to curtail hospital admission rates for mastitis and

medicolegal implications29 . breast abscess may also couple pathway implementation to

One of the key barriers to optimal management is the fre- an independent case review.

quent presentation of patients to non-specialist emergency In addition to the integrated management pathway

services out of hours. Non-specialists did not report any improving key process measures and patient outcomes,

significant issues in following the management pathway there are potentially significant cost benefits of getting

and referral pro forma, and dissemination was facilitated management ‘right first time’7 . Such changes have down-

by the Trust’s intranet. The standardized approach to stream consequences, and an impact assessment would

managing women with mastitis and/or breast abscess led highlight the additional cost of outpatient appointments,

to measurable and non-transient improvements in key specialist ultrasound assessments and image-guided aspira-

process and outcome measures. tions. Interestingly, although access to ultrasound imaging

It is noteworthy that the improvement in some key per- improved, the aspiration rate did not change significantly.

formance indicators, such as reduction in hospital admis- The reasons for this are probably multifactorial, perhaps

sion rates, did not occur until phase III of the study. This indicating the availability of staff with appropriate skills

reflects the importance of ongoing education and train- in image-guided aspirations, or more likely reflecting the

ing sessions even after phase II implementation, in order relative proportions of inflammatory change (mastitis)

to hardwire best practice30 . It also highlights the need versus collection (abscess) observed sonographically. The

to maintain staff engagement with quality improvement latter may reflect scans being undertaken earlier in the

initiatives31 . The fact that pathway training was repeated natural history of mastitis before abscess development.

before further practice audit may account for the positive Limitations of this study include the retrospective nature

impact in eventually curtailing admission rates. Notwith- of the initial audit, which may have failed to capture

standing this, the uptake of pro forma use for referrals the total number of episodes and details of treatment.

was found to vary across hospital sites and during the Although every effort was made to ensure that all women

course of the audit. The management of change, partic- with mastitis and/or breast abscess were included dur-

ularly protocol awareness and compliance, represents an ing the study phases, patients in whom the pro forma

© 2018 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Management of mastitis and breast abscess

and pathway were not used may have been missed and 7 Getting it Right First Time. Breast Surgery. http://

the true denominator therefore remains unknown. Patient gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk/surgical-specialty/breast-

demographic data were not collected to determine the surgery/ [accessed 13 March 2018].

distribution of key confounding variables such as breast- 8 Jahanfar S, Ng CJ, Teng CL. Antibiotics for mastitis in

breastfeeding women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; (1):

feeding, smoking or diabetes. The number of patients

CD005458.

included in this study was modest and the unpredictable

9 Crepinsek MA, Crowe L, Michener K, Smart NA.

nature of mastitis/abscess presentation made it challenging

Interventions for preventing mastitis after childbirth.

to ensure parity in the number of patients between each Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; (8)CD007239.

phase of the study. The sample size may also have con- 10 Stern C. Interventions for preventing mastitis after

tributed to the observation of clinically important improve- childbirth. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2010; 8: 290.

ments that failed to reach statistical significance (type II 11 Jahanfar S, Ng CJ, Teng CL. Antibiotics for mastitis in

error with false-negative findings) such as hospital admis- breastfeeding women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;

sion rates and length of inpatient stay. (2)CD005458.

An integrated care pathway and referral pro forma, along 12 Hayes R, Michell M, Nunnerley HB. Acute inflammation of

with ongoing education and training of staff, achieved sig- the breast – the role of breast ultrasound in diagnosis and

nificant and sustained improvements in the management management. Clin Radiol 1991; 44: 253–256.

13 Crowe DJ, Helvie MA, Wilson TE. Breast infection.

of patients with mastitis and/or breast abscess presenting

Mammographic and sonographic findings with clinical

to this NHS Trust. These quality improvements may be

correlation. Invest Radiol 1995; 30: 582–587.

generalizable to other acute Trusts with similar organi-

14 Tan SM, Low SC. Non-operative treatment of breast

zational structures. Future work will explore options for abscesses. Aust N Z J Surg 1998; 68: 423–424.

national-level engagement on breast sepsis through collab- 15 Schwarz RJ, Shrestha R. Needle aspiration of breast

orations with the breast surgery work stream of the GIRFT abscesses. Am J Surg 2001; 182: 117–119.

quality improvement initiative7 . 16 Kang YD, Kim YM. Comparison of needle aspiration and

vacuum-assisted biopsy in the ultrasound-guided drainage of

lactational breast abscesses. Ultrasonography 2016; 35:

Acknowledgements

148–152.

This study was funded by the Breast Unit, Imperial College 17 Eryilmaz R, Sahin M, Hakan Tekelioglu M, Daldal E.

Healthcare NHS Trust and Imperial National Institute for Management of lactational breast abscesses. Breast 2005; 14:

375–379.

Health Research Biomedical Research Centre.

18 Strauss A, Middendorf K, Müller-Egloff S, Heer IM, Untch

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

M, Bauerfeind I. Sonographically guided percutaneous

needle aspiration of breast abscesses–a minimal-invasive

References alternative to surgical incision. Ultraschall Med 2003; 24:

1 Kataria K, Srivastava A, Dhar A. Management of lactational 393–398.

mastitis and breast abscesses: review of current knowledge 19 Thrush S, Iddon J, Dixon J. Current treatment of breast

and practice. Indian J Surg 2013; 75: 430–435. abscesses in the UK. Br J Surg 2004; 91(Suppl (1): 79.

2 Meguid M, Kort K, Numan P. Subareolar breast abscess: the 20 Chandika AB, Gakwaya AM, Kiguli-Malwadde E, Chalya

penultimate stage of the mammary duct-associated PL. Ultrasound guided needle aspiration versus surgical

inflammatory disease sequence. In The Breast (3rd edn), drainage in the management of breast abscesses: a Ugandan

Bland KI, Copeland EM III (eds). Saunders: St Louis, 2004; experience. BMC Res Notes 2012; 5: 12.

93–131. 21 Guidelines and Audit Implementation Network (GAIN).

3 Moazzez A, Kelso RL, Towfigh S, Sohn H, Berne TV, Guidelines on the Treatment, Management & Prevention of

Mason RJ. Breast abscess bacteriologic features in the era of Mastitis; 2009. https://rqia.org.uk/RQIA/files/68/681b5723-

community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus 6972-4e11-8a09-24cea893d430.pdf [accessed 31

aureus epidemics. Arch Surg 2007; 142: 881–884. May 2015].

4 Inch S, von-Xylander S. Mastitis: Causes and Management. 22 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

World Health Organization: Geneva, 2000. Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Mastitis and Breast Abscess.

5 Mason HS. Mastitis and Breast Abscess; 2016. https://cks.nice.org.uk/mastitis-and-breast-abscess [accessed

https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/1084 [accessed 13 13 March 2018].

March 2018]. 23 Eshelby S, MacAskill F, Contractor K, Asha O,

6 Thomsen AC, Espersen T, Maigaard S. Course and Thiruchelvam P, Curtis S et al. Development of a treatment

treatment of milk stasis, noninfectious inflammation of the pathway to improve quality of care in the management of

breast, and infectious mastitis in nursing women. Am J Obstet breast abscess and mastitis. Eur J Surg Oncol 2016;

Gynecol 1984; 149: 492–495. 42: S4.

© 2018 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

N. Patani, F. MacAskill, S. Eshelby, A. Omar, A. Kaura, K. Contractor et al.

24 Nathavitharana K. Online generic induction for doctors in 32 Wiltsey Stirman S, Kimberly J, Cook N, Calloway A, Castro

training: an end to repetition? Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2011; F, Charns M. The sustainability of new programs and

72: 586–589. innovations: a review of the empirical literature and

25 Russell JP, Regel T. After the Quality Audit: Closing the Loop recommendations for future research. Implement Sci 2012;

on the Audit Process (2nd edn). ASQC/Quality Press: 7: 17.

Milwaukee, 2000. 33 Stumbo SP, Ford JH II, Green CA. Factors influencing the

26 Bharat A, Gao F, Aft RL, Gillanders WE, Eberlein TJ, long-term sustainment of quality improvements made in

Margenthaler JA. Predictors of primary breast abscesses and addiction treatment facilities: a qualitative study. Addict Sci

recurrence. World J Surg 2009; 33: 2582–2586. Clin Pract 2017; 12: 26.

27 Rizzo M, Peng L, Frisch A, Jurado M, Umpierrez G. Breast 34 Dixon-Woods M, McNicol S, Martin G. Ten challenges in

abscesses in nonlactating women with diabetes: clinical improving quality in healthcare: lessons from the Health

features and outcome. Am J Med Sci 2009; 338: 123–126. Foundation’s programme evaluations and relevant literature.

28 Gollapalli V, Liao J, Dudakovic A, Sugg SL, Scott-Conner BMJ Qual Saf 2012; 21: 876–884.

CE, Weigel RJ. Risk factors for development and recurrence 35 Bray P, Cummings DM, Wolf M, Massing MW, Reaves J.

of primary breast abscesses. J Am Coll Surg 2010; 211: After the collaborative is over: what sustains quality

41–48. improvement initiatives in primary care practices? Jt Comm J

29 Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman. Hospital Fails Qual Patient Saf 2009; 35: 502–508.

to Diagnose Breast Cancer; 2014. https://www.ombudsman.org 36 Wang Y, Tian Y, Tian LL, Qian YM, Li JS. An electronic

.uk/sites/default/files/Hospital_fails_to_diagnose_breast_ medical record system with treatment recommendations

cancer_report.pdf [accessed 13 March 2018]. based on patient similarity. J Med Syst 2015; 39: 55.

30 Glasgow JM, Yano EM, Kaboli PJ. Impacts of organizational 37 Fowler SA, Yaeger LH, Yu F, Doerhoff D, Schoening P,

context on quality improvement. Am J Med Qual 2013; 28: Kelly B. Electronic health record: integrating evidence-based

196–205. information at the point of clinical decision making. J Med

31 Roueche A, Hewitt J. ‘Wading through treacle’: quality Libr Assoc 2014; 102: 52–55.

improvement lessons from the frontline. BMJ Qual Saf 38 Hayes L. Improving junior doctor handover between jobs.

2012; 21: 179–183. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2014; 3.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the

article.

© 2018 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Sumabong NCM109 JOURNALREADINGDokumen6 halamanSumabong NCM109 JOURNALREADINGMark VincentBelum ada peringkat

- Intl J Gynecology Obste - 2023 - Reyther - The Use of The Double Uterine Segment Tourniquet in Obstetric Hysterectomy ForDokumen5 halamanIntl J Gynecology Obste - 2023 - Reyther - The Use of The Double Uterine Segment Tourniquet in Obstetric Hysterectomy ForDrFeelgood WolfslandBelum ada peringkat

- s12884 019 2244 4 PDFDokumen7 halamans12884 019 2244 4 PDFAnitaBelum ada peringkat

- Treatment of Bbreast InfectionDokumen12 halamanTreatment of Bbreast InfectionThắng NguyễnBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal 1Dokumen10 halamanJurnal 1Ismail RasminBelum ada peringkat

- 6 - Benign Breast DiseaseDokumen10 halaman6 - Benign Breast DiseasebernijesiBelum ada peringkat

- Benign Breast Disease PDFDokumen10 halamanBenign Breast Disease PDFEmmanuel BarriosBelum ada peringkat

- Cesarean Delivery Technique Evidence or Tradition A Review of The Evidence-Based DeliveryDokumen12 halamanCesarean Delivery Technique Evidence or Tradition A Review of The Evidence-Based DeliveryKrizt Denisse LedezmaBelum ada peringkat

- Dominici 2010Dokumen5 halamanDominici 2010Lavonia Berlina AdzalikaBelum ada peringkat

- 1ajajajanabb393 14 195 1Dokumen14 halaman1ajajajanabb393 14 195 1indah ayu lestari100% (1)

- Paper AbdAllah RefaatDokumen13 halamanPaper AbdAllah RefaatAbdAllah A. RefaatBelum ada peringkat

- New Options for Managing Adherent PlacentaDokumen6 halamanNew Options for Managing Adherent PlacentaAngelique Ramos PascuaBelum ada peringkat

- Nejmoa 2303966Dokumen11 halamanNejmoa 2303966Raul ForjanBelum ada peringkat

- Sagesorg-Guidelines For The Use of Laparoscopy During PregnancyDokumen32 halamanSagesorg-Guidelines For The Use of Laparoscopy During PregnancyLuis Acosta CumberbatchBelum ada peringkat

- Journal of Surgical Oncology - 2013 - Fortunato - When Mastectomy Is Needed Is The Nipple Sparing Procedure A New StandardDokumen6 halamanJournal of Surgical Oncology - 2013 - Fortunato - When Mastectomy Is Needed Is The Nipple Sparing Procedure A New StandardJethro ConcepcionBelum ada peringkat

- Evidence of Self-Directed Learning: 1. Reflection On Ectopic Pregnancy RetrievedDokumen3 halamanEvidence of Self-Directed Learning: 1. Reflection On Ectopic Pregnancy RetrievedJasha MaeBelum ada peringkat

- Conservative Manangement v2.BS - LSDokumen27 halamanConservative Manangement v2.BS - LSOihane Manterola LasaBelum ada peringkat

- Manual Removal of The Placenta: Evaluation of Some Risk Factors and Management Outcome in A Tertiary Maternity Unit. A Case Controlled StudyDokumen6 halamanManual Removal of The Placenta: Evaluation of Some Risk Factors and Management Outcome in A Tertiary Maternity Unit. A Case Controlled StudylindasundaBelum ada peringkat

- Management of Cervical CancerDokumen29 halamanManagement of Cervical CancersangheetaBelum ada peringkat

- Nieto-Calvache. The Uterine Toruniquet, A Simple Maneuver That May Facilitate... IJGO 2023Dokumen3 halamanNieto-Calvache. The Uterine Toruniquet, A Simple Maneuver That May Facilitate... IJGO 2023Salomé HBelum ada peringkat

- Re: Laparoscopic Myomectomy: A Review of Alternatives, Techniques and ControversiesDokumen1 halamanRe: Laparoscopic Myomectomy: A Review of Alternatives, Techniques and ControversiesMayada OsmanBelum ada peringkat

- RCT Compares Caesarean Section Surgical TechniquesDokumen11 halamanRCT Compares Caesarean Section Surgical TechniquesWahab RopekBelum ada peringkat

- OncoplasticDokumen14 halamanOncoplasticYefry Onil Santana MarteBelum ada peringkat

- Pi Is 0020729214001040Dokumen5 halamanPi Is 0020729214001040Nurul AiniBelum ada peringkat

- Vesicovaginal FistulaDokumen6 halamanVesicovaginal FistulaMaiza TusiminBelum ada peringkat

- Tubalpregnancy DiagnosisandmanagementDokumen12 halamanTubalpregnancy DiagnosisandmanagementAndreaAlexandraBelum ada peringkat

- 10 11648 J Ejpm 20140203 11Dokumen4 halaman10 11648 J Ejpm 20140203 11intansarifnosaaBelum ada peringkat

- Nipple DischargeDokumen8 halamanNipple DischargeGabriela Zavaleta CamachoBelum ada peringkat

- A Case Analysis OnDokumen100 halamanA Case Analysis OnHannah Pearl MagallenBelum ada peringkat

- Effective Screening10Dokumen4 halamanEffective Screening10ponekBelum ada peringkat

- PIIS0015028219304844Dokumen2 halamanPIIS0015028219304844nighshift serialsleeperBelum ada peringkat

- Study of Management in Patient With Ectopic Pregnancy: Key WordsDokumen3 halamanStudy of Management in Patient With Ectopic Pregnancy: Key WordsparkfishyBelum ada peringkat

- Step-by-Step Diagnosis of Inflammatory Breast DisordersDokumen14 halamanStep-by-Step Diagnosis of Inflammatory Breast DisordersseruniallisaaslimBelum ada peringkat

- Revista CBC - 2017 InlgesDokumen8 halamanRevista CBC - 2017 InlgesAntonio Rodrigues Braga NetoBelum ada peringkat

- Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of laparoscopy during pregnancyDokumen13 halamanGuidelines for diagnosis and treatment of laparoscopy during pregnancyCecilia Quispe JaureguiBelum ada peringkat

- Fetal Intervetion - Abdelghaffarhelal2019Dokumen20 halamanFetal Intervetion - Abdelghaffarhelal2019Trần Ngọc BíchBelum ada peringkat

- Acta 90 405Dokumen6 halamanActa 90 405Eftychia GkikaBelum ada peringkat

- John Tidy: 21 The Role of Surgery in The Management of Gestational Trophoblastic DiseaseDokumen17 halamanJohn Tidy: 21 The Role of Surgery in The Management of Gestational Trophoblastic DiseaseRana RaydianBelum ada peringkat

- Endometriosis T&F Group Report Highlights Care Pathway and Outcome MeasuresDokumen81 halamanEndometriosis T&F Group Report Highlights Care Pathway and Outcome MeasuresMary De la HozBelum ada peringkat

- Fraser MajorbreastDokumen10 halamanFraser Majorbreastmissvi86Belum ada peringkat

- Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: Some Management OptionsDokumen4 halamanCesarean Scar Pregnancy: Some Management OptionsFerro PratamaBelum ada peringkat

- MRM ArticleDokumen5 halamanMRM ArticleRekha Tulsi KhatriBelum ada peringkat

- The Management of Second Trimester MiscarriageDokumen30 halamanThe Management of Second Trimester MiscarriagexxdrivexxBelum ada peringkat

- Randomized Comparison of SubcuDokumen11 halamanRandomized Comparison of SubcuRafael MarvinBelum ada peringkat

- Managment of Scar PregnancyDokumen43 halamanManagment of Scar Pregnancyvacha sardarBelum ada peringkat

- Cervical Cancer in The Pregnant PopulationDokumen15 halamanCervical Cancer in The Pregnant PopulationLohayne ReisBelum ada peringkat

- RCOG Guidelines - Gestational Trophoblastic DiseaseDokumen12 halamanRCOG Guidelines - Gestational Trophoblastic Diseasemob3100% (1)

- Accepted ManuscriptDokumen33 halamanAccepted ManuscriptFarhana AnuarBelum ada peringkat

- Palpable Nodules After Autologous Fat Grafting in Breast Cancer Patients: Incidence and Impact On Follow-UpDokumen9 halamanPalpable Nodules After Autologous Fat Grafting in Breast Cancer Patients: Incidence and Impact On Follow-UpMarcos LouroBelum ada peringkat

- Hysterectomy For Gynecological Indication in Six Medical Facilities in LubumbashiDRC Frequency, Indications, Early Operative ComplicationsDokumen11 halamanHysterectomy For Gynecological Indication in Six Medical Facilities in LubumbashiDRC Frequency, Indications, Early Operative ComplicationsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Management of Peritoneal Metastases- Cytoreductive Surgery, HIPEC and BeyondDari EverandManagement of Peritoneal Metastases- Cytoreductive Surgery, HIPEC and BeyondAditi BhattBelum ada peringkat

- Rosen's Breast Pathology IntroductionDokumen18 halamanRosen's Breast Pathology IntroductionyoussBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation, Prevention, and ManagementDokumen2 halamanEvaluation, Prevention, and Managementkelompok tutorBelum ada peringkat

- Sutura CesareasDokumen10 halamanSutura CesareasalexBelum ada peringkat

- Compliance With Thromboprophylaxis After Gynecology SurgeryDokumen10 halamanCompliance With Thromboprophylaxis After Gynecology SurgeryShahla AlalafBelum ada peringkat

- Placental accreta predictive and preventive treatment approachDokumen11 halamanPlacental accreta predictive and preventive treatment approachHeyzel FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- Uncomplicated Term Vaginal Delivery Following Magnetic Resonance-Guided Focused Ultrasound Surgery For Uterine FibroidsDokumen4 halamanUncomplicated Term Vaginal Delivery Following Magnetic Resonance-Guided Focused Ultrasound Surgery For Uterine FibroidsMangku Liong GuanBelum ada peringkat

- FIGO Statement Uterine Atony Uterotonics PPH ENDokumen5 halamanFIGO Statement Uterine Atony Uterotonics PPH ENSOFIA MORALESBelum ada peringkat

- 816-Article Text-5949-1-10-20230609Dokumen6 halaman816-Article Text-5949-1-10-20230609NikadekPramesti Dewi Puspita SariBelum ada peringkat

- Rita Alcaraz: Clinical Experience and SkillsDokumen1 halamanRita Alcaraz: Clinical Experience and Skillsapi-398600648Belum ada peringkat

- Visual Inspection With Acetic Acid (Via)Dokumen38 halamanVisual Inspection With Acetic Acid (Via)Princess Jeanne Roque GairanodBelum ada peringkat

- Francesco - Cranial, Craniofacial and Skull Base SurgeryDokumen367 halamanFrancesco - Cranial, Craniofacial and Skull Base SurgeryDrpriya Priya100% (3)

- Human sexuality: Sexual response cycle, orientation, expression & disordersDokumen28 halamanHuman sexuality: Sexual response cycle, orientation, expression & disordersAhmad Riva'i100% (1)

- Suture Size: SmallestDokumen2 halamanSuture Size: SmallestGeraldine BirowaBelum ada peringkat

- Disclosure To Promote The Right To InformationDokumen58 halamanDisclosure To Promote The Right To InformationAnamika TiwaryBelum ada peringkat

- Pedo Tooth AnomaliesDokumen5 halamanPedo Tooth Anomalieszuperzilch1676Belum ada peringkat

- Obstetric AnesthesiaDokumen440 halamanObstetric Anesthesiamonir61100% (1)

- Teratogenic Pregnancy RisksDokumen40 halamanTeratogenic Pregnancy RisksVonny RiskaBelum ada peringkat

- Philiphs HD7 Brochure - UltrasoundDokumen6 halamanPhiliphs HD7 Brochure - UltrasoundIvan CvasniucBelum ada peringkat

- JWHO 6 Week Heartbeat Ban LawsuitDokumen14 halamanJWHO 6 Week Heartbeat Ban LawsuitRuss LatinoBelum ada peringkat

- K19 - Pathology of OvaryDokumen26 halamanK19 - Pathology of OvaryMuhammad AbdillahBelum ada peringkat

- Sterling Hospital charges index guideDokumen112 halamanSterling Hospital charges index guideAnimesh JainBelum ada peringkat

- A&E ServicesDokumen38 halamanA&E ServiceskanikaBelum ada peringkat

- F623Dokumen8 halamanF623Gustavo Suarez100% (1)

- 12 Most Famous Medical Malpractice CasesDokumen9 halaman12 Most Famous Medical Malpractice Casesdivya kalraBelum ada peringkat

- Pediatric Surgery Diagnosis and TreatmentDokumen460 halamanPediatric Surgery Diagnosis and TreatmentPatricia Beznea100% (2)

- Ramos vs. Court of AppealsDokumen46 halamanRamos vs. Court of AppealsoliveBelum ada peringkat

- Omega-3 & PregnancyDokumen3 halamanOmega-3 & PregnancysolarwindBelum ada peringkat

- E W C O F: Arly Ound ARE IN PEN RacturesDokumen3 halamanE W C O F: Arly Ound ARE IN PEN RacturesMatheis Laskar PelangiBelum ada peringkat

- Ophthalmology at The Medical CityDokumen16 halamanOphthalmology at The Medical CityAnonymous ic2CDkFBelum ada peringkat

- Enciclopedia della Nutrizione clinica del caneDokumen3 halamanEnciclopedia della Nutrizione clinica del caneFrancesco NaniaBelum ada peringkat

- A Simple Approach To Shared Decision Making in Cancer ScreeningDokumen6 halamanA Simple Approach To Shared Decision Making in Cancer ScreeningariskaBelum ada peringkat

- Litrature & Case StudyDokumen74 halamanLitrature & Case Studynaol buloBelum ada peringkat

- Marie Kathleen R. Tuazon: Highlights of QualificationDokumen3 halamanMarie Kathleen R. Tuazon: Highlights of Qualificationjmrt12Belum ada peringkat

- PUGSOM Graduate-Entry Medical Curriculum 4-Year Schematic - Cohort 2021Dokumen1 halamanPUGSOM Graduate-Entry Medical Curriculum 4-Year Schematic - Cohort 2021Alvin YeeBelum ada peringkat

- MD Development PaediatrcsDokumen102 halamanMD Development PaediatrcsMuhammad Farooq SaeedBelum ada peringkat

- Cirugia Bucal Y Maxilofacial: Dr. Nicolas C. Rodriguez CapilloDokumen25 halamanCirugia Bucal Y Maxilofacial: Dr. Nicolas C. Rodriguez CapilloBrayan Daniel Rosas OrtizBelum ada peringkat

- ColposDokumen41 halamanColposjumgzb 10Belum ada peringkat

- New Hci ResumeDokumen2 halamanNew Hci Resumeapi-397532577Belum ada peringkat