Slac-literacy-Decoding, Reading, and Reading Disability-Gough & Tunmer

Diunggah oleh

Mamadou Djiguimde0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

203 tayangan5 halamanliteracy-decoding

Judul Asli

Slac-literacy-Decoding, Reading, And Reading Disability-gough & Tunmer

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen Ini0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

203 tayangan5 halamanSlac-literacy-Decoding, Reading, and Reading Disability-Gough & Tunmer

Diunggah oleh

Mamadou DjiguimdeAnda di halaman 1dari 5

Decoding, Reading, and

Reading Disability

Philip B. Gough and William E. Tunmer

To clarify the role of decoding in reading and reading disability, a

simple model of reading is proposed, which holds that reading

equals the product of decoding and comprehension. It follows that

there must be three types of reading disability, resulting from an

inability to decode, an inability to comprehend, or both. It is argued

that the first is dyslexia, the second hyperlexia, and the third

common, or garden variety, reading disability.

T HE ROLE OF decoding in reading and reading dis-

ability has long been controversial. On the one hand,

some of us (e.g., Fries, 1962; Gough, 1972; Rozin & Gleit-

If decoding plays a central role in the reading process,

then it seems sensible to give it a comparable place in in-

struction, while if decoding skill is merely epiphenomenal,

man, 1977) have maintained that the ability to decode is at then it is hard to see why it should be stressed in the teach-

the core of reading ability, such that learning to decode is ing of reading. It is important to recognize, though, that

tantamount to learning to read. But others have argued the two questions are logically distinct. For example, if we

that decoding ability is at most an epiphenomenon, and were to learn that decoding plays no role at all in skilled

that instruction in decoding may distort, if not actually im- reading, it does not follow that we should ignore decoding

pede, the acquisition of literacy (e.g., Goodman, 1973; in reading instruction. It might well be that direct instruc-

Smith, 1982). tion in synthetic phonics is the fastest route to skilled read-

In this paper, we will not try to settle the debate. The ing. Or, to take another example, from the fact that read-

issue is surely an empirical one, and it should be settled by ing instruction with a code emphasis appears to be superior

experiment, not polemic. We believe that it has not been to instruction with a meaning emphasis (Chall, 1967), we

settled because of some persistent conceptual confusions. cannot conclude that decoding plays any role in skilled

Our intent here is to try to state our case more clearly, in reading.

the hope that its truth or falsity might be decisively settled The question of the role of decoding in reading and that

by future research. of its place in reading instruction are surely related, but

they are distina questions. We are here concerned only

with the first, the question of the connection between

Process versus Instruction decoding skill and reading ability.

We begin by noting that the issue we wish to discuss is

not that of the place of decoding in reading instruction. The Definition of Decoding Skill

The issue of whether and how to teach decoding (the great

debate of Chall, 1967) is certainly interconnected with the To consider this question, we must first say what we

issue of the role of decoding in skilled reading and reading mean by decoding, for we find that the term means dif-

disability, but it is not the same issue. ferent things to different people: Some equate it with

6 RASE 7(1), 6-10 (1986) 074l-9325/86/0071-0006$2.00©PRO-ED Inc.

Downloaded from rse.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 9, 2016

"sounding out," others with (context-free) word recogni- given lexical (i.e., word) information, sentences and dis-

tion. Our position is closer to the latter, for we believe that courses are interpreted.

sounding out is (at most) only a primitive form of decod- Proponents of decoding are quite willing to concede

ing (we doubt even this; see Gough & Hillinger, 1980), and that if there is no comprehension, then reading is not tak-

we believe that the skilled decoder is exactly the reader ing place; if R = D x C and C = 0, then R = 0. So the fact

who can read isolated words quickly, accurately, and si- that someone can decode but fail to read a language which

lently. Yet we are reluctant to equate decoding with word they do not know is far from an embarrassment to us;

recognition, for the term decoding surely connotes, if not rather, it is exactly what we would predict. Decoding is not

denotes, the use of letter-sound correspondence rules. We sufficient; comprehension is also necessary.

have argued (Gough, Juel, & Roper-Schneider, 1983) that At the same time, we argue that the converse holds as

beginning readers do not use such rules, and we must con- well: Comprehension is not sufficient, for decoding is also

cede that expert readers may not always do so (Gough, necessary. Knowing a language does not suffice to make

1984). But we firmly believe that word recognition skill (in one literate; the average 5-year old is living proof. Without

an alphabetic orthography) is fundamentally dependent the ability to decode, no amount of linguistic comprehen-

upon knowledge of letter-sound correspondence rules, or sion will make a reader; if R = D x C and D = 0, then

what we have called the orthographic cipher (Gough & R = 0, whatever the value of C.

Hillinger, 1980). It is this simple view, that R = D x C, which should be

As spelling reformers have long noted, knowledge of the focus of the debate over decoding. It offers consider-

this cipher is not sufficient for word recognition in En- able meat for debate, for it has a number of testable im-

glish, for it will not enable one to read irregular words like plications. For example, the simple view clearly asserts that

pint and yacht, or even orthographically ambiguous words reading ability should be predictable from a measure of

like bead and bread and steak and area. To concede that the decoding ability (e.g., the ability to pronounce pseudo-

knowledge of the cipher is not sufficient for word recogni- words) and a measure of listening comprehension.

tion, however, is not to concede that it is unnecessary; to There is abundant evidence that decoding and com-

the contrary, those of us who give allegiance to decoding prehension do make separate contributions to reading

hold that knowledge of English letter-sound correspon- ability. Using multiple regression, a number of inves-

dence rules is necessary to enable the reader to recognize tigators (e.g., Curtis, 1980; Stanovich, Cunningham, & Fee-

the majority of English words. man, 1984) have shown that pseudoword reading and

In what follows, then, we will assume that decoding listening comprehension make independent contributions

ability varies directly with knowledge of the spelling-sound to silent reading comprehension. But this shows only that

correspondence rules of English. The purest measure of some linear combination of the two is a better predictor

this is the ability to pronounce (or silently apprehend the than either alone. The simple view makes the much

pronunciation of) pseudowords like eland, otphim, or stenk, stronger claim that their product is superior to even this

and it is the role of this ability in reading which we hope to (i.e., that D + C + [D x C] will correlate with R better

pinpoint in the following discussion. than D +C). The difficulty one faces in testing this predic-

tion is that in most data sets (e.g., Stanovich, Cunningham,

& Feeman, 1984; Stanovich, personal communication), the

A Simple View of Reading linear combination of decoding and listening comprehen-

sion predicts reading so well that there is no room for im-

What, then, is claimed for decoding by its advocates? provement due to the product.

Our adversaries sometimes seem to think that the proposi-

tion we defend is that decoding is equivalent to reading,

which they then try to refute by saying "I can decode Implications for Reading Disability

Italian, but I can't read a word of it," or, "I've seen children

who can decode anything you put in front of them, but Perhaps the more interesting implication of the simple

they don't understand a word of what they're reading." view, though, concerns reading lability. According to the

simple view, reading ability can result only from the com-

No reasonable proponent of decoding has ever equated

bination of decoding and comprehension. But reading dis-

decoding and reading, for we recognize that what is

ability could result in three different ways: from an in-

decoded must also be understood. Decoding is clearly not

ability to decode, an inability to comprehend, or both.

sufficient for reading. But at the same time we argue that

decoding is necessary for reading, for if print cannot be We suggest that all three forms do exist. We propose

translated into language, then it cannot be understood. that the first is what is usually called dyslexia, the second

The simplest view of the relation between decoding and what is usually called hyperlexia, and the third we call garden

reading which anyone has ever seriously entertained is this: variety reading disability.

Reading equals the product of decoding and comprehension,

or R = D x C, where each variable ranges from 0 (nullity) Dyslexia

to 1 (perfection). We trust it is clear that by comprehen-

sion we mean, not reading comprehension, but rather The existence of a specific reading disability (that is, a

linguistic comprehension, that is, the process by which, seemingly inexplicable deficiency in reading alongside nor-

Remedial and Special Education Downloaded from rse.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 9, 2016

7

mal or superior achievement in other areas) has been noted ultimate cause of dyslexia; for this, one would have to push

for nearly a century. Once named congenital word blindness the question one step back and ask why they cannot

(Hinshelwood, 1900; Morgan, 1896) or strephosymbolia decode. We suspect that the answer to this is that they lack

(Orton, 1928), it has come to be called (developmental) phonemic awareness (Gough & Hillinger, 1980), but this

dyslexia. There has been spirited debate over whether only raises the further question of why that might be. The

dyslexia constitutes a medical disorder with a neurological ultimate answer to the question may well be biological, for

basis (Downing & Brown, 1967; Franklin, 1962). But in there is certainly evidence of both a genetic linkage (Smith,

current usage, dyslexia is defined solely by exclusion: The Kimberling, Pennington, & Lubs, 1983) and abnormal

dyslexic is an individual who has failed to learn to read de- cerebral anatomy (Galaburda & Kemper, 1979) in dyslexia.

spite normal intelligence and sensory function, adequate But we submit that the simple view of reading provides an

opportunity for learning, and an absence of severe adequate immediate answer to the question of why dys-

neurological or physical disability, emotional or social lexics cannot read: It is because they cannot decode.

problems, or socioeconomic disadvantage (Vellutino,

1979). There can be no doubt that such individuals exist. Hyperlexia

Literally hundreds of studies have been conducted in

pursuit of the cause of dyslexia (Benton & Pearl, 1978; Skill in decoding is usually accompanied by skill in com-

Vellutino, 1979). Many causes have been postulated, rang- prehension (Curtis, 1980; Perfetti & Hogaboam, 1975),

ing from incomplete cerebral lateralization (Orton, 1928) but exceptions to this rule have long been noted (Russell &

through dysfunction in intersensory integration (Birch & Goldsbury, 1845). In recent years, this condition (i.e., supe-

Belmont, 1964) or temporal sequencing (Bakker, 1972), to rior skill in decoding accompanied by average or even in-

verbal processing (Vellutino, 1979). Evidently in despair of ferior comprehension) has been labeled hyperlexia (Hut-

finding a unitary cause, a number of scholars are now tenlocher & Huttenlocher, 1973; Silberberg & Silberberg,

searching for subtypes (e.g., Doehring, Trites, Patel, & 1967, 1968, 1971). The existence of this condition is taken

Fiedorowicz, 1981). by some to show that since skill in decoding need not be

We take no position on whether there is one or more ul- accompanied by skill in reading, decoding cannot be crucial

timate causes of dyslexia. But we suggest that there is a to reading.

common denominator in every case of dyslexia, a deficit But as we have observed, even the simple view of read-

which could well stand as the proximal cause of the dis- ing does not claim that decoding is sufficient for reading,

order. This is an inability to decode. only that it is necessary. Decoding is only a step toward

What we propose is that every dyslexic is a poor comprehension, for after print is decoded, it must be un-

decoder. Obviously, we have not seen every dyslexic. But derstood. The simple view does not assert that perfection

two major studies have found dyslexic readers to have not in decoding will lead to perfection in reading. Rather, per-

merely weak, but almost nonexistent, decoding skills. In fection in decoding will make you read exactly as well as

the first of these, Firth (1972) asked large groups of you can listen: If R = D x C and D = 2, then R = C.

average and poor readers, all of average intelligence, to Happily, Healy s (1982) recent study of hyperlexia pre-

read a list of 170 nonsense words. His average readers sents the data necessary to test this prediction. Healy des-

"sailed through" the test, achieving an average of 118 cor- cribes 12 children, each of whom showed early and excep-

rect. In contrast, the poor readers averaged only 35, and tional skill in decoding accompanied by average or inferior

the worst of them "could not produce any pronunciation comprehension: Their mean chronological age was 8.2

at all for these nonsense words" (Firth, 1972, p. 123). years, while their mean age equivalent in reading com-

In a similar vein, Vellutino (1979) administered a test of prehension was only 6.3 years. Thus these superior

phonics skills to 20 dyslexic and 20 normal readers, decoders were inferior readers, and Healy takes this to sug-

matched in intelligence, in each grade from 2 through 6. gest that "advanced development of decoding skills may

The test consisted of 35 three- and four-letter mono- actually impede the acquisition of (reading) comprehension

syllabic pseudowords, like vox and nime and choo. Vellutino's abilities" (Healy, 1982, p. 337). Fortunately, Healy also

normal second graders correctly pronounced half (17.50) measured their age equivalent in listening comprehension;

of the pseudowords, and the normal readers' scores in- this was 6.0 years. Thus these hyperlexic children appeared

creased to 25.45 by the sixth grade. In contrast, his poor to read almost exactly as well as they listened, which is ex-

(dyslexic) readers averaged a mere 2.75 in the second actly what the simple view would predict.

grade, increasing to only 14.30 in the sixth. What this It would seem, then, that hyperlexia does not present a

means is that the sixth grade dyslexics (to say nothing of difficulty for the simple view of reading, but instead pro-

their younger counterparts) did not yet even know all of vides strong support for it.

the simplest letter-sound correspondences.

These studies (see also Seymour & Porpodas, 1980; Garden Variety Reading Disability

Snowling, 1980) provide clear evidence that dyslexics are

seriously deficient in decoding skill. We submit that one The existence of dyslexia, on the one hand, and

need look no further for the answer to why they cannot hyperlexia, on the other, shows that skill in comprehension

read. This is not to say that we claim to have identified the need not be accompanied by skill in decoding, and vice

8 Volume 7 Issue 1 January/February 1986

Downloaded from rse.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 9, 2016

versa. As we have noted, however, they usually do go decode and listen who cannot read, individuals who can do

together: The good decoder tends to be a good com- one but not the other and still read, or even individuals

prehender, and the poor decoder a poor one (Curtis, 1980; who can neither decode nor listen yet still read with un-

Perfetti & Hogoboam, 1975). Given this, the simple view derstanding. The existence of any such individuals will

yields the trivial prediction that most poor readers will be

deficient in both decoding and comprehension, and this is

surely confirmed by common experience. But it also yields

another prediction which is, we think, not so trivial.

In the general population, D and C are positively cor-

related. But note that if R = D x C, then within the read-

ing disabled population, decoding and comprehension

should be negatively correlated, for to achieve a low score

on reading, a skilled decoder must achieve a low score on

comprehension, and vice versa. It should be clear that

dyslexia and hyperlexia themselves offer instances of such a

negative correlation. These disorders are striking just

because they are exceptions to the rule that skill in decod-

ing and skill in comprehension go together. But note that

the dyslexic, a poor decoder, is a (relatively) skilled com- falsify the simple view. Thus, while it may seem trivial, the

prehender, while the hyperlexic, a skilled decoder, is a poor simple view makes a strong claim.

comprehender; as one factor goes up, the other must go Probably the safest prediction of the four is the last; we

down. doubt that even our fiercest adversaries would spend their

This, though, is mere hindsight; we already knew that time looking for skilled readers who could neither decode

dyslexia and hyperlexia existed. Much more importantly, nor listen. The other three categories, however, should not

the simple view predicts that if we were to examine a pop- be readily conceded. The existence of a skilled listener who

ulation of disabled readers (defined only as those deficient can read without knowing a single spelling-sound corres-

in reading achievement), we should find a correlation be- pondence rule seems to us quite imaginable if reading is

tween decoding and comprehension that is just the op- only a matter of psycholinguistic guessing (Goodman,

posite of that found in the general population. 1967); the existence of a skilled decoder who can read well

The only data we have found which bear on this predic- without good listening comprehension seems much less

tion are provided by Olson, Kliegl, Davidson, and Foltz likely. But the most vulnerable quadrant of the simple view

(1985), who asked 41 younger readers (age less than 11.5 may well be the first: that skilled decoding combined with

years) and 40 older ones (age greater than 14.5 years) to skilled listening must produce literacy.

decide which of two pseudowords (e.g., caik, dake) "sound- A number of writers (e.g., Rubin, 1980) have argued

ed like a common word." Responses were measured in that reading is fundamentally different from listening, that

terms of speed and accuracy. The authors called this reading requires a whole new repertoire of skills different

phonological skill; we take it to be an index of D. They also from those required for listening. At one level, even ad-

administered the WISC-R to each subject and obtained vocates of the simple view must agree (e.g., reading re-

from this a score on Kaufman's verbal factor (i.e., a single quires a sequence of eye movements presumably irrelevant

factor which Kaufman, 1975, found to underlie the to listening). The core of the simple view, though, is essen-

vocabulary, information, similarities, and comprehension tially the denial of this claim: The simple view presumes

subtests); we consider this a reasonable estimate of C. that, once the printed matter is decoded, the reader applies

Olson et al. (1975) reported that the correlation be- to the text exactly the same mechanisms which he or she

tween Kaufman's verbal factor and phonological skill (i.e., would bring to bear on its spoken equivalent. This is

C and D) was significantly negative (r = —.28) for the older clearly a claim that can be tested empirically: It would be

subjects, and negative ( r = —.18) though not significant for falsified if Rubin (or anyone else) would show us someone

the younger ones. Using a measure of accuracy alone for who could decode and listen, yet could not read.

the younger group (i.e., their ability simply to pronounce

the correct pseudoword), a significantly negative correla-

tion (r = —.28) was also obtained with this group. These Conclusion

correlations are not large. But they are significant and in

the opposite direction from what we know to obtain in the We conclude with the assertion that reading skill is ade-

general population. More data are clearly needed, but we quately described as the product of decoding and com-

take this to be striking, if tentative, confirmation of the prehension. We have tried to show that the evidence

simple view of reading. known to us is consistent with this simple view. We suspect

The simple view asserts only that both decoding and that the position we have proposed will appear obvious to

comprehension are essential to reading. This may be those who agree with us, but preposterous to our op-

wrong: It may be that there are individuals who can both ponents. If so, we hope the issue will be joined. J^

Remedial and Special Education 9

Downloaded from rse.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 9, 2016

Philip B. Gough, who received the PhD from the University Healy, J. (1982). The enigma of hyperlexia. Reading Research Quar-

of Minnesota in 1%1, is professor in the Department of terly, 17, 319-338.

Hinshelwood, J. (1900). Congenital word-blindness. Lancet, 1,

Curriculum and Instruction at the University of Texas at

1506-1508.

Austin. His research interest is in reading and spelling

Huttenlocher, R. R., & Huttenlocher, J. (1973). A study of

acquisition. William E. Tunmer received the PhD from the children with hyperlexia. Neurology, 23, 1107-1116.

University of Texas. He was a staff member of the Southwest Kaufman, A. S. (1975). Factor analysis of the WISC-R at eleven

Educational Development Laboratories before joining the faculty age levels between 6Vi and l6*/2 years. Journal of Consulting and

of the Department of Education at the University of Western Clinical Psychology, 43, 135-147.

Australia. His research concerns the psycholinguistics of early Morgan, W. P. (1896). A case of congenital word-blindness.

reading. British Medical Journal, 11, 378.

Olson, R., Kliegl, R., Davidson, B., & Foltz, G (1985). Individual

and developmental differences in reading disability. In G. E.

MacKinnon & T. G. Waller (Eds.), Reading research: Advances in

References theory and practice (pp. 1-64). New York: Academic Press.

Orton, S. T. (1928). Specific reading disability-strephosymbolia.

Bakker, D. J. (1972). Temporal order in disturbed reading. Rotter- Journal of the American Medical Association, 90, 1095-1099.

dam, The Netherlands: University Press. Perfetti, C , & Hogaboam, T. (1975). The relationship between

Benton, A. L., & Pearl, D. (Eds.). (1978). Dyslexia: An appraisal of single word decoding and reading comprehension skill. Journal

current knowledge. New York: Oxford. of Educational Psychology, 67, 461-469.

Birch, H. G., & Belmont, L. (1964). Auditory-visual integration Rozin, P., & Gleitman, L. R. (1977). The structure and acquisi-

in normal and retarded readers. American Journal of Ortho- tion of reading II: The reading process and the acquisition of

psychiatry, 34, 852-861. the alphabetic principle. In A. S. Reber & D. L. Scarborough

Chall, J. (1967). Learning to read: The great debate. New York: (Eds.), Toward a psychology of reading (pp. 55-142). Hillsdale,

McGraw-Hill. NJ: Erlbaum.

Curtis, M. E. (1980). Development of components of reading Rubin, A. (1980). A theoretical taxonomy of the differences be-

skill. Journal of Educational Psychology, 72, 656-669. tween oral and written language. In R. Spiro, B. Bruce, & W.

Doehring, D. G., Trites, R. L., Patel, P. G., & Fiedorowicz, C. A. Brewer (Eds.), Theoretical issues in reading comprehension. Hills-

M. (1981). Reading disabilities. New York: Academic Press. dale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Downing, J., & Brown, A. L. (Eds.). (1967). The Second Inter- Russell, W. & Goldsbury, S. (1845). Introduction to the American

national Reading Symposium. London: Cassell. common-school reader and speaker. Boston: Charles Pappan.

Firth, I. (1972). Components of reading disability. Unpublished doc- Seymour, P. H. K., & Porpodas, C. D. (1980). Lexical and non-

toral dissertation, University of New South Wales, Australia. lexical processing of spelling in developmental dyslexia. In U.

Franklin, A. W. (Ed.). (1962). Word blindness or specific developmen- Frith (Ed.), Cognitive processes in spelling (pp. 443-474). London:

tal dyslexia. London: Pitman. Academic Press.

Fries, C. C. (1962). Linguistics and reading. New York: Holt, Silberberg, N., & Silberberg, M. (1967). Hyperlexia: Specific

Rinehart & Winston. word recognition skills in young children. Exceptional Children,

Galaburda, A. M., & Kemper, T. L. (1979). Auditory cyto- 34, 41-42.

architectonic abnormalities in a case of familial developmental Silberberg, N., & Silberberg, M. (1968). Case histories in

dyslexia. Annals of Neurology, 6, 94-100. hyperlexia. Journal of School Psychology, 7, 3-7.

Goodman, K. S. (1967). Reading: A psycholinguistic guessing Silberberg, N., & Silberberg, M. (1971). Hyperlexia: The other

game. Journal of the Reading Specialist, 6, 126-135. end of the continuum. Journal of Special Education, ,5(3), 233-

Goodman, K. S. (1973). The 13th easy way to make learning to 242.

read difficult: A reaction to Gleitman and Rozin. Reading Smith, F. (1982). Understanding reading. New York: Holt,

Research Quarterly, 8, 484-493. Rinehart & Winston.

Gough, P. B. (1972). One second of reading. In J. F. Kavanagh & Smith, S. D., Kimberling, W. J., Pennington, B. F., & Lubs, M. A.

I. G Mattingly (Eds.), Language by ear and by eye (pp. 331-358). (1983). Specific reading disability: Identification of an in-

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. herited form through linkage analysis. Science, 219, 1345-

Gough, P. B. (1984). Word recognition. In P. D. Pearson (Ed.), 1347.

Handbook of reading research. New York: Longman. Snowling, M.J. (1980). The development of grapheme-phoneme

Gough, P. B., & Hillinger, M. L. (1980). Learning to read: An un- correspondence in normal and dyslexic readers. Journal of Ex-

natural act. Bulletin of the Orton Society, 30, 179-196. perimental Child Psychology, 29, 294-305.

Gough, P. B., Juel, C, & Roper-Schneider, D. (1983). Code and Stanovich, K. E., Cunningham, A. E., & Feeman, D.J. (1984). In-

cipher: A two-stage conception of initial reading acquisition. telligence, cognitive skills, and early reading progress. Reading

In J. A. Niles & L. A. Harris (Eds.), Searches for meaning in Research Quarterly, 19, 278-303.

Vellutino, F. R. (1979). Dyslexia: Theory and research. Cambridge,

reading/language processing and instruction. Thirty-secondyearbook of

the National Reading Conference, Rochester, NY. MA: MIT Press.

Volume 7 Issue 1 January/February 1986

10 Downloaded from rse.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 9, 2016

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Dyslexia Fact Sheet EngDokumen1 halamanDyslexia Fact Sheet Engapi-379317256Belum ada peringkat

- General Teaching Strategies ASDDokumen11 halamanGeneral Teaching Strategies ASDClaire ZahraBelum ada peringkat

- A Cognitive View of Reading Comprehension: Implications For Reading DifficultiesDokumen7 halamanA Cognitive View of Reading Comprehension: Implications For Reading DifficultiesAndrada-Doriana PoceanBelum ada peringkat

- Lord of The Flies Unit PlanDokumen28 halamanLord of The Flies Unit Planapi-312430378100% (2)

- Bhatt, Mehrotra - Buddhist Epistemology PDFDokumen149 halamanBhatt, Mehrotra - Buddhist Epistemology PDFNathalie67% (3)

- Module 3 - Article Review - Structured Literacy and Typical Literacy PracticesDokumen3 halamanModule 3 - Article Review - Structured Literacy and Typical Literacy Practicesapi-530797247Belum ada peringkat

- Creating Pathways for All Learners in the Middle YearsDari EverandCreating Pathways for All Learners in the Middle YearsBelum ada peringkat

- Water Stones Dyslexia Action GuideDokumen12 halamanWater Stones Dyslexia Action Guidetreazer_jetaimeBelum ada peringkat

- Literacy OverviewDokumen20 halamanLiteracy Overviewapi-459118418100% (1)

- Mississippi Best Practices Dyslexia Handbook 12 13 2010Dokumen44 halamanMississippi Best Practices Dyslexia Handbook 12 13 2010api-182083489Belum ada peringkat

- Dyslexia InfographicDokumen1 halamanDyslexia Infographicapi-510900825Belum ada peringkat

- Classroom TalkDokumen8 halamanClassroom Talkapi-340721646Belum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan NewspaperDokumen14 halamanLesson Plan NewspaperAiv Ylanan100% (1)

- Dyslexia and Specific Learning Disorders New International Diagnostic CriteriaDokumen6 halamanDyslexia and Specific Learning Disorders New International Diagnostic CriteriaTimothy Eduard A. SupitBelum ada peringkat

- Managing 15000 Network Devices With AnsibleDokumen23 halamanManaging 15000 Network Devices With AnsibleAshwini Kumar100% (1)

- The CRE Themes - Chapter Three - Rev - June2019 - EXCERPT PDFDokumen38 halamanThe CRE Themes - Chapter Three - Rev - June2019 - EXCERPT PDFSteve GarnerBelum ada peringkat

- Inclusion PDFDokumen9 halamanInclusion PDFSam ChumbasBelum ada peringkat

- Notes On Latin MaximsDokumen7 halamanNotes On Latin MaximsJr MateoBelum ada peringkat

- Developing Language and Literacy: Effective Intervention in the Early YearsDari EverandDeveloping Language and Literacy: Effective Intervention in the Early YearsPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (2)

- Writing A Literature ReviewDokumen9 halamanWriting A Literature ReviewSifu K100% (1)

- Learning DifficultiesDokumen212 halamanLearning DifficultiesNathália QueirózBelum ada peringkat

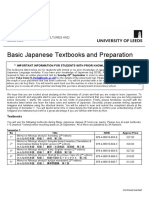

- Basic Japanese Textbooks and Preparation 2020Dokumen3 halamanBasic Japanese Textbooks and Preparation 2020Omar AshrafBelum ada peringkat

- Pre-16 Test List June 2022Dokumen26 halamanPre-16 Test List June 2022y normanBelum ada peringkat

- Self-Appraisal - Our Code Our StandardsDokumen10 halamanSelf-Appraisal - Our Code Our Standardsapi-596310133Belum ada peringkat

- Ac English Yr5 Unit OverviewDokumen7 halamanAc English Yr5 Unit OverviewLui Harris S. CatayaoBelum ada peringkat

- Kaufman Et Al. 2012 PDFDokumen16 halamanKaufman Et Al. 2012 PDFSlaven PranjicBelum ada peringkat

- Dispute of A Man With His Ba PDFDokumen25 halamanDispute of A Man With His Ba PDFmerlin66Belum ada peringkat

- Share Copy - High Frequency Words vs. Sight WordsDokumen15 halamanShare Copy - High Frequency Words vs. Sight WordsPhạm Bích HồngBelum ada peringkat

- The Science of Reading: A HandbookDari EverandThe Science of Reading: A HandbookPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- Quality Education For All LMIC Evidence Review CBM 2016 Full Report PDFDokumen39 halamanQuality Education For All LMIC Evidence Review CBM 2016 Full Report PDFJames Jemar Jimenez CastorBelum ada peringkat

- The Case For Dynamic Assessment in Speech and Language Therapy Hasson 2007Dokumen18 halamanThe Case For Dynamic Assessment in Speech and Language Therapy Hasson 2007Dayna DamianiBelum ada peringkat

- Britain's Geography, Politics and People in the British IslesDokumen31 halamanBritain's Geography, Politics and People in the British IslesThanhNhànDươngBelum ada peringkat

- Problems of Education in The 21st Century, Vol. 78, No. 6, 2020Dokumen183 halamanProblems of Education in The 21st Century, Vol. 78, No. 6, 2020Scientia Socialis, Ltd.0% (1)

- Slac-Literacy - Learning To ReadDokumen19 halamanSlac-Literacy - Learning To ReadMamadou DjiguimdeBelum ada peringkat

- Link L7 U1 Unit TestDDokumen2 halamanLink L7 U1 Unit TestDMal SwierBelum ada peringkat

- Executive Processes, Reading Comprehension and Academic AchievementDokumen8 halamanExecutive Processes, Reading Comprehension and Academic AchievementJaime JiménezBelum ada peringkat

- Phonics As InstructionDokumen3 halamanPhonics As InstructionDanellia Gudgurl DinnallBelum ada peringkat

- Inclusive Education Lived Experiences of 21st Century Teachers in The PhilippinesDokumen11 halamanInclusive Education Lived Experiences of 21st Century Teachers in The PhilippinesIJRASETPublications100% (1)

- Phonemic AwarenessDokumen8 halamanPhonemic AwarenessAli FaizanBelum ada peringkat

- Dyslexia and Foreign Language Learning-David Fulton Publishers (2004)Dokumen128 halamanDyslexia and Foreign Language Learning-David Fulton Publishers (2004)ashfaqamar100% (2)

- ESL Teachers Use of Corrective Feedback and Its Effect On Learners UptakeDokumen23 halamanESL Teachers Use of Corrective Feedback and Its Effect On Learners Uptakenguyenhoaianhthu100% (1)

- Definition of Shared ReadingDokumen2 halamanDefinition of Shared ReadinghidayahBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 4.inquiryDokumen12 halamanChapter 4.inquiryanon_473155463Belum ada peringkat

- IDA Knowledge and Practice Standards For Teaching of ReadingDokumen35 halamanIDA Knowledge and Practice Standards For Teaching of ReadingIris JordanBelum ada peringkat

- Non Word TestDokumen1 halamanNon Word TestdaroksayBelum ada peringkat

- ESF Reading Scope and SequenceDokumen6 halamanESF Reading Scope and SequenceStu LoweBelum ada peringkat

- Multiple IntelligencesDokumen3 halamanMultiple IntelligencesАлина ЛисицаBelum ada peringkat

- Te Pikinga Ki Runga - Principles 26 PracticeDokumen2 halamanTe Pikinga Ki Runga - Principles 26 PracticeHeleneBelum ada peringkat

- Rhyme Awareness AssessmentDokumen1 halamanRhyme Awareness Assessmentapi-346639341Belum ada peringkat

- Using An Interprofessional Lens With Assignment 2Dokumen9 halamanUsing An Interprofessional Lens With Assignment 2tracycwBelum ada peringkat

- The Simple View of Reading: (Hoover & Gough, 1990)Dokumen2 halamanThe Simple View of Reading: (Hoover & Gough, 1990)Cara CilentoBelum ada peringkat

- Phonological AwarenessDokumen11 halamanPhonological AwarenessJoy Lumamba TabiosBelum ada peringkat

- RealdingDokumen158 halamanRealdingArbil Avodroc NoliugaBelum ada peringkat

- The Dyslexic Reader 2005 - Issue 40Dokumen32 halamanThe Dyslexic Reader 2005 - Issue 40Davis Dyslexia Association International100% (9)

- Reading DifficultiesDokumen7 halamanReading DifficultiesFailan MendezBelum ada peringkat

- Social motivation theory of autism focuses on impaired reward processingDokumen10 halamanSocial motivation theory of autism focuses on impaired reward processingChrysoula Gkani100% (1)

- SeeingStars Lesson PlanDokumen11 halamanSeeingStars Lesson PlanMaria Maqsoudi-KarimiBelum ada peringkat

- Health Forward Planning DocumentDokumen7 halamanHealth Forward Planning Documentapi-373839745Belum ada peringkat

- DCSF Teaching Effective VocabularyDokumen16 halamanDCSF Teaching Effective VocabularyMatt GrantBelum ada peringkat

- Rhyme ProductionDokumen9 halamanRhyme Productionapi-217065852Belum ada peringkat

- s1 - Edla Unit JustificationDokumen8 halamans1 - Edla Unit Justificationapi-319280742Belum ada peringkat

- Teaching OralDokumen266 halamanTeaching OralMohammed Belmili100% (1)

- 7 Hinge QuestionsDokumen6 halaman7 Hinge QuestionsJenny TingBelum ada peringkat

- Fisher FreyDokumen6 halamanFisher Freyapi-392256982Belum ada peringkat

- Mtss Parent Explanation Letter 2015-16-Long VersionDokumen2 halamanMtss Parent Explanation Letter 2015-16-Long Versionapi-110894488Belum ada peringkat

- Mental Representations and PerkinsDokumen10 halamanMental Representations and Perkinsapi-350301135Belum ada peringkat

- Effective Word Reading Instruction What Does The Evidence Tell UsDokumen9 halamanEffective Word Reading Instruction What Does The Evidence Tell UsDaniel AlanBelum ada peringkat

- 12 Wfxoq HDJDokumen523 halaman12 Wfxoq HDJelabelatelaBelum ada peringkat

- MST Primary Integrated6 UnitDokumen25 halamanMST Primary Integrated6 Unitapi-248229122Belum ada peringkat

- The Fox and The Forest Fire Educator GuideDokumen3 halamanThe Fox and The Forest Fire Educator GuideChronicleBooksBelum ada peringkat

- Slac Literacy Issues in Second Language Reading NassajiDokumen13 halamanSlac Literacy Issues in Second Language Reading NassajiMamadou DjiguimdeBelum ada peringkat

- SHIELD Consulting 1: Real-Time Crime Prevention SystemDokumen13 halamanSHIELD Consulting 1: Real-Time Crime Prevention SystemMamadou DjiguimdeBelum ada peringkat

- Age and L2 Learning The Hazards of MatchDokumen20 halamanAge and L2 Learning The Hazards of MatchMamadou DjiguimdeBelum ada peringkat

- How Psych Sci Informs Teaching of Reading - Rayner Et Al.Dokumen44 halamanHow Psych Sci Informs Teaching of Reading - Rayner Et Al.Eder CabralBelum ada peringkat

- 2016 DartDokumen22 halaman2016 DartManuel MachadoBelum ada peringkat

- Age and AccentDokumen17 halamanAge and AccentMamadou DjiguimdeBelum ada peringkat

- Fact Sheet MercuryDokumen3 halamanFact Sheet MercuryFreddy FloresBelum ada peringkat

- Birectional Crosslinguistic Influence - Linguistic Aspects and BeyondDokumen12 halamanBirectional Crosslinguistic Influence - Linguistic Aspects and BeyondMamadou DjiguimdeBelum ada peringkat

- Techwrite Unit 1 - AssignmentDokumen1 halamanTechwrite Unit 1 - AssignmentMamadou DjiguimdeBelum ada peringkat

- Field Interview Transcription TemplateDokumen5 halamanField Interview Transcription TemplateMamadou DjiguimdeBelum ada peringkat

- Field Interview Transcription TemplateDokumen5 halamanField Interview Transcription TemplateMamadou DjiguimdeBelum ada peringkat

- Talking To Insi 31598882Dokumen1 halamanTalking To Insi 31598882Mamadou DjiguimdeBelum ada peringkat

- The Ethnographic EssayDokumen2 halamanThe Ethnographic EssayMamadou DjiguimdeBelum ada peringkat

- Ritassida Mamadou Djiguimde: Academic AppointmentDokumen6 halamanRitassida Mamadou Djiguimde: Academic AppointmentMamadou DjiguimdeBelum ada peringkat

- Ritassida Mamadou Djiguimde: Academic AppointmentDokumen6 halamanRitassida Mamadou Djiguimde: Academic AppointmentMamadou DjiguimdeBelum ada peringkat

- Eyes Are Not Here Q & ADokumen2 halamanEyes Are Not Here Q & AVipin Chaudhary75% (8)

- Form 3 Ar2 Speaking Exam PaperDokumen5 halamanForm 3 Ar2 Speaking Exam PaperGrace WongBelum ada peringkat

- Whole Language N Multiple IntelligencesDokumen22 halamanWhole Language N Multiple IntelligencesPuthut J. BoentoloBelum ada peringkat

- My Experiences Task 6Dokumen7 halamanMy Experiences Task 6Laura MorenoBelum ada peringkat

- PGFO Week 9 - Debugging in ScratchDokumen13 halamanPGFO Week 9 - Debugging in ScratchThe Mountain of SantaBelum ada peringkat

- Constructors & Destructors Review: CS 308 - Data StructuresDokumen21 halamanConstructors & Destructors Review: CS 308 - Data StructureshariprasathkBelum ada peringkat

- Problem Set 2Dokumen4 halamanProblem Set 2Thomas LimBelum ada peringkat

- Olevel English 1123 June 2017 Writing Paper BDokumen4 halamanOlevel English 1123 June 2017 Writing Paper BShoumy NJBelum ada peringkat

- 22MCA344-Software Testing-Module1Dokumen22 halaman22MCA344-Software Testing-Module1Ashok B PBelum ada peringkat

- Pas 62405Dokumen156 halamanPas 62405Nalex GeeBelum ada peringkat

- Models of CommunicationDokumen63 halamanModels of CommunicationChristille Grace Basa MuchuelasBelum ada peringkat

- IEO English Sample Paper 1 For Class 12Dokumen37 halamanIEO English Sample Paper 1 For Class 12Santpal KalraBelum ada peringkat

- PWX 861 Message ReferenceDokumen982 halamanPWX 861 Message Referencekomalhs100% (1)

- Bài Tập Về Đại Từ Nhân XưngDokumen46 halamanBài Tập Về Đại Từ Nhân XưngVuong PhanBelum ada peringkat

- Your Personal StatementDokumen2 halamanYour Personal Statemental561471Belum ada peringkat

- Translation Strategies GuideDokumen7 halamanTranslation Strategies GuideMuetya Permata DaraBelum ada peringkat

- Kisi-Kisi Soal - KD 3.1 - KD 4.1 - Kls XiiDokumen14 halamanKisi-Kisi Soal - KD 3.1 - KD 4.1 - Kls Xiisinyo201060% (5)

- C ProgrammingDokumen118 halamanC ProgrammingNimisha SinghBelum ada peringkat

- A Literary Study of Odovan, An Urhobo Art FormDokumen93 halamanA Literary Study of Odovan, An Urhobo Art Formaghoghookuneh75% (4)

- Intellispace ECG Ordering Guide - September 2020Dokumen5 halamanIntellispace ECG Ordering Guide - September 2020Hoàng Anh NguyễnBelum ada peringkat

- Zero Conditional New VersionDokumen12 halamanZero Conditional New VersionMehran RazaBelum ada peringkat