Carpio v. Guevara

Diunggah oleh

Nico Nuñez0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

12 tayangan4 halamanThis document is a Supreme Court decision dismissing a petition for writ of habeas corpus filed by two individuals who were detained under warrants for violation of anti-subversion laws. The petitioners had been temporarily released from military custody by order of the President during the habeas corpus proceedings. As the petitioners were no longer detained, the Supreme Court resolved to dismiss the petition as moot and academic. In its decision, the Court emphasized the importance of respecting constitutional rights to peaceable assembly following the lifting of martial law.

Deskripsi Asli:

Human Rights

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniThis document is a Supreme Court decision dismissing a petition for writ of habeas corpus filed by two individuals who were detained under warrants for violation of anti-subversion laws. The petitioners had been temporarily released from military custody by order of the President during the habeas corpus proceedings. As the petitioners were no longer detained, the Supreme Court resolved to dismiss the petition as moot and academic. In its decision, the Court emphasized the importance of respecting constitutional rights to peaceable assembly following the lifting of martial law.

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

12 tayangan4 halamanCarpio v. Guevara

Diunggah oleh

Nico NuñezThis document is a Supreme Court decision dismissing a petition for writ of habeas corpus filed by two individuals who were detained under warrants for violation of anti-subversion laws. The petitioners had been temporarily released from military custody by order of the President during the habeas corpus proceedings. As the petitioners were no longer detained, the Supreme Court resolved to dismiss the petition as moot and academic. In its decision, the Court emphasized the importance of respecting constitutional rights to peaceable assembly following the lifting of martial law.

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 4

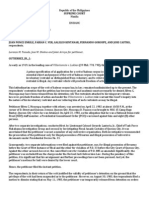

EN BANC

[G.R. No. L-57439. August 27, 1981.]

J. ANTONIO M. CARPIO and GRACE VINZONS-MAGANA , petitioners,

vs. LT. COL. EDGAR GUEVARA, as Camp Commandant, Camp

Bagong Ibalon, Regional Command V , respondent.

Lorenzo M. Tañada, Joker P. Arroyo and Jose W. Diokno for petitioners.

Solicitor General Estelito P. Mendoza, Assistant Solicitor General Roberto

E. Soberano and Solicitor Roberto A. Abad for respondent.

SYNOPSIS

Petitioners, detained at Camp Bagong Ibalon, Legaspi City, assailed the

validity of the warrants of arrest issued against them for violation of Article 138

of the Revised Penal Code dealing with incitement to rebellion, P.D. No. 885, the

amended Anti-Subversion Law, and P.D. No. 33 on the possession and

distribution of subversive materials.

The Supreme Court issued a writ. of habeas corpus and set the case for

hearing. In the return of the writ, the validity of the commitment order was

invoked but the Solicitor General manifested that the President had ordered the

petitioners' temporary release. Thereafter, the Constabulary Judge Advocate

wrote that petitioners have been released from military custody. In view of this

development, the Supreme Court resolved to dismiss the petition, for being moot

and academic.

SYLLABUS

1. CONSTITUTIONAL LAW; RIGHT TO PEACEABLE ASSEMBLY; NO ADVERSE

CONSEQUENCES ON THE EXERCISE THEREOF WITH THE LIFTING OF MARTIAL LAW. —

With the lifting of martial law, the people have a right to expect that reliance on the

constitutional right to peaceable assembly would not be visited with adverse

consequences. It should be safeguarded and respected not only by courts but by other

public officials, especially those entrusted with the task of maintaining peace and order.

The danger to public security that could conceivably arise by people gathering en masse is

certainly much less. It is quite true that turbulence may mark such an event. One who is

responsible certainly can be held accountable if the assembly is utilized for illegal

purposes. The guilty parties can be duly proceeded against. In the absence of such a

showing, it is of the essence in a constitutional government that no encroachment on the

rights of an individual is permissible.

2. ID.; ID.; PARTICIPATION IN A PEACEABLE ASSEMBLY CANNOT BE PROSCRIBED. —

What was said by Chief Justice Hughes with force and eloquence in De Jonge v. Oregon,

299 U.S. 353 (1936) possesses relevance: ". . . The holding of meetings for peaceable

political action cannot be proscribed. Those who assist in the conduct of such meetings

cannot be branded as criminals on that score. The question, if the rights of free speech

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. 2016 cdasiaonline.com

and peaceable assembly are to be preserved, is not as to the auspices under which the

meeting is held but as to its purpose; not as to the relations of the speakers, but whether

their utterances transcend the bounds of the freedom of speech which the Constitution

protects. If the persons assembling have committed crimes elsewhere, if they have

formed or are engaged in a conspiracy against the public peace and order they may be

prosecuted for their conspiracy or other violation of valid laws. But it is a different matter

when the State instead of prosecuting them for such offenses seizes upon mere

participation in a peaceable assembly and a lawful public discussion as the basis for a

criminal charge."

3. ID.; ID.; PETITION FOR WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS; DISMISSAL THEREOF WHERE

THERE IS NO LONGER ANY DETENTION. — Where, as in the case at bar, the petitioners

have been released from military custody the petition is dismissed for being moot and

academic.

DECISION

FERNANDO , C.J. : p

It is the claim of petitioners J. Antonio M. Carpio and Grace Vinzons-

Magana in this application for the writ of habeas corpus led on July 20, 1981,

that their detention at Camp Bagong Ibalon, Legaspi City is illegal, there being no

valid authority for the warrants of arrest respectively issued against them on July

2 and 3, 1981. The Presidential Order of Arrest was allegedly signed on June 26,

1981 for the violation of Art. 138 of the Revised Penal Code dealing with

incitement to rebellion, Presidential Decree No. 885, the amended Anti-Subversion

Law, and Presidential Decree No. 33 on the possession and distribution of

subversive materials. It was further alleged that petitioners were only shown a

copy of what appeared to be a radiogram, no signed copy of the order having

been furnished them. It was then alleged that there was no justi cation for their

detention, that martial law having been terminated on January 17, 1981 and

President Marcos himself having "banned the use of military processes of arrest

and issued a letter of instruction ordering that, thenceforth, all arrests, even for

alleged crimes involving national security, must undergo normal judicial

processes." 1

The next day, on July 21, 1981, this Court issued a writ of habeas corpus

requiring respondent to make a return not later than Tuesday, July 28, 1981 and

setting the case for hearing on July 30, 1981. In the return of the writ, the

detention of petitioners was characterized as "lawful and valid, having been done

by virtue of a presidential commitment order, issued pursuant to the reservation

of power under Presidential Proclamation 2045, exercised by the President on

the strength of the evidence before him." 2 Nonetheless, at the hearing on July 30,

1981, to quote from the language of the resolution of this Court of that date: "The

Solicitor General manifested that President Ferdinand E. Marcos issued an order

yesterday directing the temporary release of detainees-petitioners J. Antonio M.

Carpio and Grace Vinzons-Magana on recognizance of Assemblyman Marcial

Pimentel. On his part, Senator Diokno (a) manifested that yesterday morning,

after he met the petitioners at the airport, they all reported to the military

authorities and in such conference, Deputy Minister Carmelo Barbero turned over

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. 2016 cdasiaonline.com

the custody of petitioners-detainees to Senator Diokno for which he signed a

receipt to produce them in today's hearing, and (b) requested that the hearing of

this case be postponed until further orders of the Court, with the petitioners-

detainees in the meantime to stay in his custody." 3

The Court then resolved to: "(1) postpone the hearing of this case until

further notice; (2) declare that pending the full implementation of the order of

release and on the authority of this Court, aforesaid detainees-petitioners shall

remain in the custody of Senator Diokno on his recognizance; and (3) grant the

Solicitor General until 4:00 o'clock in the afternoon of Monday, August 3, 1981

within which to submit a manifestation as to whether or not said release has been

implemented, with the certi cate of release therein included." 4 Thereafter, on

August 3, 1981 this manifestation and motion was led by Solicitor General

Estelito P. Mendoza: 6

His prayer is for the dismissal of the case on the ground of its moot and

academic character.

The plea is impressed with merit. With the release of petitioners, the prayer

is justi ed. No further action need be taken on the application for the writ of

habeas corpus except to dismiss it for having become moot and academic. It is

reassuring to note that the President upon being informed of the circumstances

of the case decided to set petitioners at liberty. With the lifting of martial law, the

people have a right to expect that reliance on the constitutional right to peaceable

assembly would not be visited with adverse consequences. It should be

safeguarded and respected not only by courts but by other public of cials,

especially those entrusted with the task of maintaining peace and order. The

danger to public security that could conceivably arise by people gathering en

masse is certainly much less. It is quite true that turbulence may mark such an

event. One who is responsible certainly can be held accountable if the assembly is

utilized for illegal purposes. The guilty parties can be duly proceeded against. In

the absence of such a showing, it is of the essence in a constitutional government

that no encroachment on the rights of an individual is permissible.

What was said by Chief Justice Hughes with force and eloquence in De

Jonge v. Oregon, 7 possesses relevance: "These rights may be abused by using

speech or press or assembly in order to incite to violence and crime. The people

through their legislatures may protect themselves against that abuse. But the

legislative intervention can nd constitutional justi cation only by dealing with the

abuse. The rights themselves must not be curtailed. The greater the importance

of safeguarding the community from incitements to the overthrow of our

institutions by force and violence, the more imperative is the need to preserve

inviolate the constitutional rights of free speech, free press and free assembly in

order to maintain the opportunity for free political discussion, to the end that

government may be responsive to the will of the people and that changes, if

desired, may be obtained by peaceful means. Therein lies the security of the

Republic, the very foundation of constitutional government. It follows from these

considerations that, consistently with the Federal Constitution, peaceable

assembly for lawful discussion cannot be made a crime. The holding of meetings

for peaceable political action cannot be proscribed. Those who assist in the

conduct of such meetings cannot be branded as criminals on that score. The

question, if the rights of free speech and peaceable assembly are to be

preserved, is not as to the auspices under which the meeting is held but as to its

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. 2016 cdasiaonline.com

purpose; not as to the relations of the speakers, but whether their utterances

transcend the bounds of the freedom of speech which the Constitution protects.

If the persons assembling have committed crimes elsewhere, if they have formed

or are engaged in a conspiracy against the public peace and order, they may be

prosecuted for their conspiracy or other violation of valid laws. But it is a different

matter when the State, instead of prosecuting them for such offenses, seizes

upon mere participation in a peaceable assembly and a lawful public discussion

as the basis for a criminal charge." 8

It is understandable for the members of the Armed Forces, duty bound to

maintain public peace, to display a certain degree of apprehension under

conditions that could lead to the disruption of public order on a big scale. At the

same time, zeal in the performance of their duties cannot justify any erosion in the

respect that must be accorded the liberties of a citizen. At any rate, with the

President ordering the release of petitioners, an untenable situation has been

resolved and the grant of the petition rendered unnecessary.

WHEREFORE, the petition is dismissed for being moot and academic.

Teehankee, Makasiar, Aquino, Concepcion Jr., Fernandez, Guerrero, De

Castro and Melencio-Herrera, JJ., concur.

Barredo and Abad Santos, JJ., are on leave.

Footnotes

1. Petition, par. 4.02.

2. Return to the Writ, par. 11.

3. Resolution dated July 30, 1981.

4. Ibid.

5. He was assisted by Assistant Solicitor General Roberto E. Soberano and Solicitor

Roberto A. Abad.

6. Manifestation and Motion, 1-2.

7. 299 U.S. 353 (1936).

8. Ibid, 364-365.

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. 2016 cdasiaonline.com

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Nestle' Phils. vs. Sanchez, 154 SCRA 542 - Picketing Outside SC Building Contempt of CourtDokumen33 halamanNestle' Phils. vs. Sanchez, 154 SCRA 542 - Picketing Outside SC Building Contempt of CourtRollyn Dee De Marco PiocosBelum ada peringkat

- HR Digests DraftDokumen10 halamanHR Digests DraftJustin RavagoBelum ada peringkat

- Lacson vs. PerezDokumen3 halamanLacson vs. PerezNina CastilloBelum ada peringkat

- 14 Carpio Vs GuevaraDokumen3 halaman14 Carpio Vs GuevaraFaye Jennifer Pascua PerezBelum ada peringkat

- SC upholds Marcos suspension of writ of habeas corpusDokumen3 halamanSC upholds Marcos suspension of writ of habeas corpusSimeon Dela CruzBelum ada peringkat

- HR BQsDokumen6 halamanHR BQsNoel SernaBelum ada peringkat

- Session 2 Consti IIDokumen71 halamanSession 2 Consti IImaushi.abinalBelum ada peringkat

- Supreme Court Rules on Peremptory Challenges in Military Court MartialDokumen13 halamanSupreme Court Rules on Peremptory Challenges in Military Court Martialleojay24Belum ada peringkat

- G.R. No. 14772323Dokumen21 halamanG.R. No. 14772323Johndale de los SantosBelum ada peringkat

- Fair Trial Challenges in Military CourtDokumen11 halamanFair Trial Challenges in Military CourtJoanna RosemaryBelum ada peringkat

- David vs. MacapagalDokumen3 halamanDavid vs. MacapagalShira Mae GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- Philippines Supreme Court upholds rights of arrested anti-govt rebelsDokumen7 halamanPhilippines Supreme Court upholds rights of arrested anti-govt rebelsBion Henrik PrioloBelum ada peringkat

- Lacson v. PerezDokumen4 halamanLacson v. PerezJNMGBelum ada peringkat

- Due Process - Impartial and Competent CourtDokumen23 halamanDue Process - Impartial and Competent CourtEmBelum ada peringkat

- Due Process - Impartial and Competent CourtDokumen8 halamanDue Process - Impartial and Competent CourtEmBelum ada peringkat

- Excessive Bail Ruling OverturnedDokumen18 halamanExcessive Bail Ruling OverturnedCaleb Josh PacanaBelum ada peringkat

- David vs. Macapagal-Arroyo DigestDokumen7 halamanDavid vs. Macapagal-Arroyo DigestMafgen Jamisola CapangpanganBelum ada peringkat

- 04-16.martelino v. AlejandroDokumen12 halaman04-16.martelino v. AlejandroOdette JumaoasBelum ada peringkat

- Writ of Habeas Corpus, Data Cases - SPECIAL PROCEEDINGSDokumen69 halamanWrit of Habeas Corpus, Data Cases - SPECIAL PROCEEDINGSCalagui Tejano Glenda JaygeeBelum ada peringkat

- G.R. No. L-1352 April 30 J 1947 MONTEBON vs. THE DIRECTOR OF PRISONSDokumen3 halamanG.R. No. L-1352 April 30 J 1947 MONTEBON vs. THE DIRECTOR OF PRISONSDat Doria PalerBelum ada peringkat

- Moncupa v. EnrileDokumen4 halamanMoncupa v. EnrileAlexandra KhadkaBelum ada peringkat

- Aquino v. Enrile Ruling on Martial Law DetentionsDokumen4 halamanAquino v. Enrile Ruling on Martial Law DetentionsMA. TERESA DADIVAS100% (1)

- David V Macapagal-ArroyoDokumen2 halamanDavid V Macapagal-ArroyoChap ChoyBelum ada peringkat

- G.R. No. 193459Dokumen97 halamanG.R. No. 193459Marie ReloxBelum ada peringkat

- Constitutional Limits of Presidential Power During States of EmergencyDokumen4 halamanConstitutional Limits of Presidential Power During States of EmergencyAntonio Ines Jr.Belum ada peringkat

- Aquino v. Enrile Case SummaryDokumen8 halamanAquino v. Enrile Case SummaryNia Julian100% (1)

- Moncupa Vs EnrileDokumen4 halamanMoncupa Vs EnrileTina TinsBelum ada peringkat

- Spouses Santiago v. Tulfo, GR No. 205039, 21 October 2015 - ESCRADokumen13 halamanSpouses Santiago v. Tulfo, GR No. 205039, 21 October 2015 - ESCRAmheritzlynBelum ada peringkat

- CH 1 Aquino Vs Enrile 59 Scra 183 1974Dokumen558 halamanCH 1 Aquino Vs Enrile 59 Scra 183 1974Gieann BustamanteBelum ada peringkat

- Julio Lagmay To Southwing Heavy IndustriesDokumen12 halamanJulio Lagmay To Southwing Heavy IndustriesJean Ben Go SingsonBelum ada peringkat

- G.R. No. 193459 February 15, 2011 GUTIERREZ vs. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON JUSTICE. Et AlDokumen86 halamanG.R. No. 193459 February 15, 2011 GUTIERREZ vs. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON JUSTICE. Et AlDat Doria PalerBelum ada peringkat

- Consti DigestsDokumen12 halamanConsti DigestsLouieze Gerald GerolinBelum ada peringkat

- Mejoff vs. Director of Prisons Habeas Corpus Case for Russian Spy's ReleaseDokumen19 halamanMejoff vs. Director of Prisons Habeas Corpus Case for Russian Spy's ReleaseD Del SalBelum ada peringkat

- Habeas Habeas Corpus Corpus Petitioners vs. VS.: en BancDokumen24 halamanHabeas Habeas Corpus Corpus Petitioners vs. VS.: en BancGerard TinampayBelum ada peringkat

- Case Digests Political Law: LabelsDokumen55 halamanCase Digests Political Law: LabelsJacqueline Pulido DaguiaoBelum ada peringkat

- Senate Blue Ribbon Committee powers examinedDokumen21 halamanSenate Blue Ribbon Committee powers examinedJoanna EBelum ada peringkat

- Suspension of Writ of Habeas Corpus UpheldDokumen6 halamanSuspension of Writ of Habeas Corpus UpheldNathalie Jean YapBelum ada peringkat

- 2011 Gutierrez v. House of Representatives20210424 14 W02eh4Dokumen88 halaman2011 Gutierrez v. House of Representatives20210424 14 W02eh4Juan Dela CruzBelum ada peringkat

- Constitution Statutes Executive Issuances Judicial Issuances Other Issuances Jurisprudence International Legal Resources AUSL ExclusiveDokumen8 halamanConstitution Statutes Executive Issuances Judicial Issuances Other Issuances Jurisprudence International Legal Resources AUSL ExclusiveAnonymous Qk4vkC8HBelum ada peringkat

- House Committee Resolution on Ombudsman Impeachment CaseDokumen39 halamanHouse Committee Resolution on Ombudsman Impeachment CaseAshura ShitsukeBelum ada peringkat

- 35-Reyes v. Bagatsing G.R. No. L-65366 November 9, 1983Dokumen9 halaman35-Reyes v. Bagatsing G.R. No. L-65366 November 9, 1983Jopan SJBelum ada peringkat

- Gutierrez vs. House of Representatives Committee On Justice, Et - Al.Dokumen87 halamanGutierrez vs. House of Representatives Committee On Justice, Et - Al.Chriscelle Ann PimentelBelum ada peringkat

- President's Power to Suspend Writ of Habeas Corpus UpheldDokumen3 halamanPresident's Power to Suspend Writ of Habeas Corpus Upheld上原クリスBelum ada peringkat

- Gutierrez vs. The House of Representatives Committee On Justice, G.R. No. 193459, February 15, 2011Dokumen38 halamanGutierrez vs. The House of Representatives Committee On Justice, G.R. No. 193459, February 15, 2011Jaime PinuguBelum ada peringkat

- Political Law: Discussion of Political CasesDokumen43 halamanPolitical Law: Discussion of Political Casesjanelle_12Belum ada peringkat

- Lacson Vs PerezDokumen4 halamanLacson Vs PerezririrojoBelum ada peringkat

- Digest Cases On Constitutional LawDokumen12 halamanDigest Cases On Constitutional LawJunDagzBelum ada peringkat

- Lacson Vs PerezDokumen33 halamanLacson Vs PerezJbMesinaBelum ada peringkat

- Gutierrez v. The House of Representatives Committee On Justice, G.R. No. 193459, 15 Feb 2011 PDFDokumen91 halamanGutierrez v. The House of Representatives Committee On Justice, G.R. No. 193459, 15 Feb 2011 PDFGab EstiadaBelum ada peringkat

- Lacson V PerezDokumen26 halamanLacson V PerezSheina GeeBelum ada peringkat

- David v. ArroyoDokumen2 halamanDavid v. ArroyoadeeBelum ada peringkat

- Martelino Vs AlejandroDokumen8 halamanMartelino Vs AlejandromanilatabajondaBelum ada peringkat

- David v. Arroyo, G.R. No. 171390, May 3, 2006Dokumen101 halamanDavid v. Arroyo, G.R. No. 171390, May 3, 2006Reginald Dwight FloridoBelum ada peringkat

- Secretary of Defense v. ManaloDokumen4 halamanSecretary of Defense v. ManaloCourtney TirolBelum ada peringkat

- Supreme Court: Lorenzo M. Tanada, Jose W. Diokno and Joker Arroyo For PetitionerDokumen3 halamanSupreme Court: Lorenzo M. Tanada, Jose W. Diokno and Joker Arroyo For PetitionerJosef elvin CamposBelum ada peringkat

- David Vs Gma Locus StandiDokumen3 halamanDavid Vs Gma Locus Standianon_360675804Belum ada peringkat

- Consti - Art 2 Case DigestsDokumen18 halamanConsti - Art 2 Case DigestsSSBelum ada peringkat

- The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll, Volume 11 (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): MiscellanyDari EverandThe Works of Robert G. Ingersoll, Volume 11 (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): MiscellanyBelum ada peringkat

- People v. JumawanDokumen2 halamanPeople v. JumawanNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- People V BonaaguaDokumen2 halamanPeople V BonaaguaNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- People v. JalosjosDokumen2 halamanPeople v. JalosjosNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- Francisco v. Court of AppealsDokumen2 halamanFrancisco v. Court of AppealsNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- Colinares vs. PeopleDokumen2 halamanColinares vs. PeopleNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- People v. CaoiliDokumen1 halamanPeople v. CaoiliNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- Ricalde V PeopleDokumen1 halamanRicalde V PeopleNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- Lagrosa v. PeopleDokumen2 halamanLagrosa v. PeopleNico Nuñez100% (1)

- People V SaleyDokumen2 halamanPeople V SaleyNico Nuñez50% (2)

- People VS DuclosinDokumen2 halamanPeople VS DuclosinNico Nuñez100% (3)

- CA Denies Probation for Dimakuta Despite Lower PenaltyDokumen2 halamanCA Denies Probation for Dimakuta Despite Lower PenaltyNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- People V PangilinanDokumen2 halamanPeople V PangilinanNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- Suspended Sentence for Minors Under Juvenile Justice ActDokumen2 halamanSuspended Sentence for Minors Under Juvenile Justice ActNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- Vicoy V. People GR NO. 138203 July, 2002 FactsDokumen1 halamanVicoy V. People GR NO. 138203 July, 2002 FactsNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- Madali V PeopleDokumen2 halamanMadali V PeopleNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- Padilla V DizonDokumen2 halamanPadilla V DizonNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- BOC 2015 Civil Law Reviewer (Final)Dokumen602 halamanBOC 2015 Civil Law Reviewer (Final)Joshua Laygo Sengco88% (17)

- Expertravel V CADokumen2 halamanExpertravel V CANico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- Juvenile Justice Act benefits OrtegaDokumen1 halamanJuvenile Justice Act benefits OrtegaNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- Us Vs Parrone ISSUE: Should Art. 22 of The Penal Code Apply, Allowing The AmendmentsDokumen2 halamanUs Vs Parrone ISSUE: Should Art. 22 of The Penal Code Apply, Allowing The AmendmentsNico Nuñez100% (1)

- Ferrer V CollectorDokumen3 halamanFerrer V CollectorNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- Merger Exempted Shareholders from Capital Gains TaxDokumen2 halamanMerger Exempted Shareholders from Capital Gains TaxNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- Persons, Family, Relations ReviewerDokumen47 halamanPersons, Family, Relations ReviewerNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- Us Vs Parrone ISSUE: Should Art. 22 of The Penal Code Apply, Allowing The AmendmentsDokumen2 halamanUs Vs Parrone ISSUE: Should Art. 22 of The Penal Code Apply, Allowing The AmendmentsNico Nuñez100% (1)

- Tuason V LingadDokumen2 halamanTuason V LingadNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- Persons-Atty. Legarda Reviewer (MLSG) PDFDokumen45 halamanPersons-Atty. Legarda Reviewer (MLSG) PDFJc IsidroBelum ada peringkat

- Lung Center V Quezon CityDokumen2 halamanLung Center V Quezon CityNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- CIR V JohnsonDokumen6 halamanCIR V JohnsonNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- ACP Vs CPG Comparison Table D2020Dokumen3 halamanACP Vs CPG Comparison Table D2020Karlo KapunanBelum ada peringkat

- Naguiat held jointly liable for taxi company's obligationsDokumen1 halamanNaguiat held jointly liable for taxi company's obligationsNico NuñezBelum ada peringkat

- 14312/BHUJ BE EXP Sleeper Class (SL)Dokumen2 halaman14312/BHUJ BE EXP Sleeper Class (SL)AnnuBelum ada peringkat

- 07 Making Disciples 2020 (For Study Purposes)Dokumen72 halaman07 Making Disciples 2020 (For Study Purposes)Kathleen Marcial100% (6)

- WR CSM 20 NameList 24032021 EngliDokumen68 halamanWR CSM 20 NameList 24032021 EnglivijaygnluBelum ada peringkat

- CH 12 Fraud and ErrorDokumen28 halamanCH 12 Fraud and ErrorJoyce Anne GarduqueBelum ada peringkat

- ACCT5001 2022 S2 - Module 3 - Lecture Slides StudentDokumen33 halamanACCT5001 2022 S2 - Module 3 - Lecture Slides Studentwuzhen102110Belum ada peringkat

- ManualDokumen108 halamanManualSaid Abu khaulaBelum ada peringkat

- UPCAT Application Form GuideDokumen2 halamanUPCAT Application Form GuideJM TSR0% (1)

- Ethics in Organizational Communication: Muhammad Alfikri, S.Sos, M.SiDokumen6 halamanEthics in Organizational Communication: Muhammad Alfikri, S.Sos, M.SixrivaldyxBelum ada peringkat

- 2022 062 120822 FullDokumen100 halaman2022 062 120822 FullDaniel T. WarrenBelum ada peringkat

- Compromise AgreementDokumen2 halamanCompromise AgreementPevi Mae JalipaBelum ada peringkat

- Model articles of association for limited companies - GOV.UKDokumen7 halamanModel articles of association for limited companies - GOV.UK45pfzfsx7bBelum ada peringkat

- Caterpillar Cat 301.8C Mini Hydraulic Excavator (Prefix JBB) Service Repair Manual (JBB00001 and Up) PDFDokumen22 halamanCaterpillar Cat 301.8C Mini Hydraulic Excavator (Prefix JBB) Service Repair Manual (JBB00001 and Up) PDFfkdmma33% (3)

- Final Merit List of KU For LaptopDokumen31 halamanFinal Merit List of KU For LaptopAli Raza ShahBelum ada peringkat

- 1.1 Simple Interest: StarterDokumen37 halaman1.1 Simple Interest: Starterzhu qingBelum ada peringkat

- Capital Budget Project OverviewDokumen2 halamanCapital Budget Project OverviewddBelum ada peringkat

- AML Compliance Among FATF States (2018)Dokumen18 halamanAML Compliance Among FATF States (2018)ruzainisarifBelum ada peringkat

- New General Ledger IntroductionDokumen3 halamanNew General Ledger IntroductionManohar GoudBelum ada peringkat

- BISU COMELEC Requests Permission for Upcoming SSG ElectionDokumen2 halamanBISU COMELEC Requests Permission for Upcoming SSG ElectionDanes GuhitingBelum ada peringkat

- Dr. M. Kochar vs. Ispita SealDokumen2 halamanDr. M. Kochar vs. Ispita SealSipun SahooBelum ada peringkat

- Expert Opinion Under Indian Evidence ActDokumen11 halamanExpert Opinion Under Indian Evidence ActmysticblissBelum ada peringkat

- V32LN SpanishDokumen340 halamanV32LN SpanishEDDIN1960100% (4)

- Kenya Methodist University Tax Exam QuestionsDokumen6 halamanKenya Methodist University Tax Exam QuestionsJoe 254Belum ada peringkat

- Got - Hindi S04 480pDokumen49 halamanGot - Hindi S04 480pT ShrinathBelum ada peringkat

- New Key Figures For BPMon & Analytics - New Controlling & SAP TM Content & Changes Key Figures - SAP BlogsDokumen8 halamanNew Key Figures For BPMon & Analytics - New Controlling & SAP TM Content & Changes Key Figures - SAP BlogsSrinivas MsrBelum ada peringkat

- Chem Office Enterprise 2006Dokumen402 halamanChem Office Enterprise 2006HalimatulJulkapliBelum ada peringkat

- Brochure - Ratan K Singh Essay Writing Competition On International Arbitration - 2.0 PDFDokumen8 halamanBrochure - Ratan K Singh Essay Writing Competition On International Arbitration - 2.0 PDFArihant RoyBelum ada peringkat

- The Universities and Their Function - Alfred N Whitehead (1929)Dokumen3 halamanThe Universities and Their Function - Alfred N Whitehead (1929)carmo-neto100% (1)

- Au Dit TinhDokumen75 halamanAu Dit TinhTRINH DUC DIEPBelum ada peringkat

- ISLAWDokumen18 halamanISLAWengg100% (6)

- Modules For Online Learning Management System: Computer Communication Development InstituteDokumen26 halamanModules For Online Learning Management System: Computer Communication Development InstituteAngeline AsejoBelum ada peringkat