MENOpausia IMAGENES (2) y Prevalencia y Fisoología de La Misma Monteleone2018

Diunggah oleh

Felipe Torreblanca CoronaHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

MENOpausia IMAGENES (2) y Prevalencia y Fisoología de La Misma Monteleone2018

Diunggah oleh

Felipe Torreblanca CoronaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

REVIEWS

Symptoms of menopause —

global prevalence, physiology

and implications

Patrizia Monteleone, Giulia Mascagni, Andrea Giannini, Andrea R. Genazzani

and Tommaso Simoncini

Abstract | The symptoms of menopause can be distressing, particularly as they occur at a time

when women have important roles in society, within the family and at the workplace. Hormonal

changes that begin during the menopausal transition affect many biological systems.

Accordingly, the signs and symptoms of menopause include central nervous system-related

disorders; metabolic, weight, cardiovascular and musculoskeletal changes; urogenital and skin

atrophy; and sexual dysfunction. The physiological basis of these manifestations is emerging as

complex and related, but not limited to, oestrogen deprivation. Findings generated mainly

from longitudinal population studies have shown that ethnic, geographical and individual

factors affect symptom prevalence and severity. Moreover, and of great importance to clinical

practice, the latest research has highlighted how certain menopausal symptoms can be

associated with the onset of other disorders and might therefore serve as predictors of future

health risks in postmenopausal women. The goal of this Review is to describe in a timely

manner new research findings on the global prevalence and physiology of menopausal

symptoms and their impact on future health.

Hot flashes

In common belief, the symptoms of menopause arise neurochemical changes within the central nervous sys-

A sudden wave of body heat from the permanent cessation of menstrual periods, tem (CNS)2. In postmenopause, long-term manifesta-

accompanied by reddening of which defines this condition1. However, hot flashes and tions of definite oestrogen deprivation ensue, such as

the face and neck and profuse night sweats, insomnia and mood instability might urogenital atrophy and ageing of the skin, and osteopo-

sweating, sometimes

actually begin before the cessation of menses and are rosis might develop during this time. In addition, a shift

followed by a feeling of cold

and shivering.

the manifestation of incipient ovarian failure1. The tran- towards central body fat distribution and the consequent

sition from the reproductive period to the first year metabolic alterations might occur as a result of increases

Ovarian failure of postmenopause, termed perimenopause, occurs over in the androgen:oestrogen ratio3, which is also driven by

The definite loss of function of several years and is characterized by substantial bio- increased insulin resistance4.

the ovaries.

logical change. According to the widely accepted Stages The symptoms of menopause can be very distress-

of Reproductive Ageing Workshop (STRAW) staging ing and can considerably affect the personal, social

system, perimenopause encompasses three stages: early and work lives of women. Owing to the heterogeneous

menopausal transition (also known as early perimen- nature of menopausal symptoms, a firm understanding

opause), characterized by persistent irregularity of the of their physiological basis has been established only

Division of Obstetrics and menstrual cycle; late menopausal transition (also known following many years of investigation. The development

Gynecology, Department of as late perimenopause), characterized by an interval of of the STRAW staging system1 (TABLE 1), which is based

Clinical and Experimental amenorrhoea of ≥60 days in the prior 12 months; and on the menstrual patterns of women, has allowed inves-

Medicine, University of Pisa,

early postmenopause, which is the first year following tigators to generate more uniform scientific data regard-

Via Savi 10, Pisa 56126,

Italy. the final menstrual period (FMP)1. Perimenopause is ing events correlated with menopause and has prompted

Correspondence to A.R.G.

characterized by marked fluctuations in levels of sex research on the assessment of trajectories of hormonal

andrea.genazzani@med. hormones, which are greater than those that occur changes and their clinical correlates1. Moreover, over

unipi.it during the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual the past decade, data from epidemiological studies

doi:10.1038/nrendo.2017.180 cycle during premenopause, and is associated with involving many women have been made available to

Published online 2 Feb 2018 the worst menopausal symptom burden, arising from investigators in the field of menopause. These large

NATURE REVIEWS | ENDOCRINOLOGY ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION | 1

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

Key points Central nervous system-related symptoms

CNS-related symptoms are those arising as a conse-

• Menopausal symptoms have a substantial effect on the quality of life of women and quence of the neurobiochemical changes that occur after

on performance at the workplace; increased awareness of symptoms and acquisition ovarian failure, such as vasomotor symptoms, sleep dis-

of coping strategies might help turbances, anxiety and depression, migraine and changes

• Certain menopausal symptoms might serve as markers for future health; severe in cognitive performance.

vasomotor symptoms and sleep disorders might increase cardiovascular risk,

whereas severe vasomotor symptoms and depression might affect cognitive Vasomotor symptoms. Approximately 75% of women

function

experience vasomotor symptoms during menopause2.

• The nature of menopausal symptoms is common to all women; however, geographical Vasomotor symptoms are the hallmark of menopause

location and ethnicity influence the prevalence of certain symptoms

and are defined as hot flashes and sweating, sometimes

• Individual factors such as personal history, current health status (particularly followed by trembling and a feeling of coldness (FIG. 1).

obesity) and socioeconomic status considerably worsen a woman’s experience

These are typically the most frequent and bothersome

of menopause

symptoms associated with menopause due to their sud-

• Health-care providers should offer education to women on improving modifiable den and seemingly random onset during the day and

lifestyle factors to reduce the risk of future illness

even at night. Vasomotor symptoms can begin as early

• Menopause seems to accelerate the ageing process; therefore, the manifestation of as 2 years before the FMP, peak 1 year after the FMP and

menopausal symptoms might be in part due to ageing

continue for 4 years after the FMP in approximately half

of women6. Approximately 12% of women will continue

reporting symptoms as far as 11–12 years after the FMP6,7.

population studies have not only increased the robust- In fact, one study reported that approximately one-third

ness of research conclusions but have also incorporated of women aged 65–79 years still report vasomotor symp-

different ethnicities, allowing between-group obser- toms8. It seems that women who begin to experience

vations. Importantly, in contrast to the cross-sectional vasomotor symptoms earlier with respect to the FMP

studies that were performed in the past, new data have will experience these symptoms for longer periods in

been generated from longitudinal studies and therefore postmenopause, with a median time of 7.4 years9.

provide important insight into the temporal pattern Although vasomotor symptoms influence the quality

of the development of menopausal symptoms and the of life of women during daytime, they also greatly alter

associated hormonal changes. the quality of sleep. Indeed, women with nocturnal vaso-

The scope of this Review is to describe symptoms of motor symptoms have greater motor restlessness in bed,

menopause in light of new findings generated from the less efficient sleep and a reduced feeling of restedness in

study of ethnicity and geographical location, personal the morning compared to women without night-time

history and individual characteristics as factors influ- symptoms10. Nocturnal hot flashes are more common

encing a woman’s experience of menopause and the during the first 4 hours of sleep and are associated with

impact of these symptoms on her social and personal a greater number of episodes of waking after the onset

life. Up‑to‑date evidence on the complex physiology of sleep, whereas later rapid-eye-movement (REM)

of menopausal symptoms is provided. Moreover, as an sleep suppresses hot flashes, arousals and awakenings11.

important contribution to modern clinical practice, this Furthermore, following pharmacological induction of

Review offers insight into the associations between cer- temporary menopause using gonadotropin-releasing

tain menopausal symptoms and other disorders and the hormone (GnRH)-analogue administration in pre-

implications of these associations for future health in menopausal volunteers, vasomotor symptoms arise

postmenopausal women5. most commonly during the first stage of sleep and wake,

typically preceding or occurring simultaneously with

Menopause and its symptoms wake episodes12.

Menopause, with its signs and symptoms, occurs at a

time in a woman’s life when she is often actively engaged Sleep disruption. Sleep difficulties, particularly nocturnal

in family upbringing and/or handling a full-time job, awakenings, are major complaints and are reported by

Postmenopause during which time she might also have the responsibil- 40–60% of menopausal women13,14 (FIG. 1). The increased

The period of a woman’s life ity of caring for ageing parents. Women are often puz- occurrence of sleep disruptions has been clearly demon-

that follows the final menstrual

period.

zled by the remarkable changes in mood, sleep patterns, strated among perimenopausal and postmenopau-

memory and body shape that occur, as well as the onset sal women compared with premenopausal women in

Perimenopause of vasomotor and urogenital symptoms. As menopau- the multiethnic, community-based Study of Women’s

The period of a woman’s life sal symptoms can be very distressing and considerably Health Across the Nation (SWAN)15,16. Data from the

that encompasses the

affect a woman’s personal and social life, health-care Penn Ovarian Ageing Study collected over an 8‑year

menopausal transition and the

first year following the final providers caring for women at all levels of the health- period have suggested that the decline of sleep quality in

menstrual period. care system must be well prepared to guide patients menopausal women might be due to menopause-related

through this transition and provide advice to improve symptoms, namely, hot flashes and depressive symp-

Amenorrhoea quality of life. In this section, a detailed description of toms17. Moreover, a recent polysomnography study found

The absence of menstrual

periods for 3 or more

the wide range of symptoms experienced by women at that self-reported and physiological hot flashes are more

consecutive months in a menopause, in relation to the affected biological system, common in menopausal women with insomnia than in

woman of reproductive age. is provided (FIG. 1). women who do not develop clinical insomnia and that

2 | ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION www.nature.com/nrendo

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

Table 1 | The Stages of Reproductive Ageing Workshop staging system

Stage Duration Terminology Menstrual cycle characteristics

Menarche

−5 Variable Reproductive: early Variable to regular

−4 Variable Reproductive: peak Regular

−3b Variable Reproductive: late Regular

−3a Variable Reproductive: late Subtle changes in flow length

−2 Variable Menopausal transition: early Variable length: persistent ≥7 day difference

in length of consecutive cycles

−1 1–3 years Menopausal transition: late Interval of amenorrhea of ≥60 days

Final menstrual period

+1a 2 years Postmenopause: early –

+1b 3–6 years Postmenopause: early –

+1c 3–6 years Postmenopause: early –

+2 Remaining Postmenopause: late –

lifespan

Adapted with permission from REF. 208, Elsevier.

the presence of objective hot flashes predicts the num- and twice that in men28. Women with a personal history

ber of awakenings, indicating a clear contribution for of major depression are at risk of relapse during peri-

hot flashes in sleep disturbance18. Sleep electroenceph- menopause23,25,29 and in the first 2 years of postmeno-

alography has demonstrated that the underlying cause pause but not beyond30. However, it is unclear whether

of impaired sleep quality in late perimenopausal and women who have never experienced major depression in

postmenopausal women might be related to a change in their premenopausal years are at increased risk during or

arousal levels during both REM and non-REM sleep19. after menopausal transition31,32. Regarding anxiety, data

Sleep disruption in menopause might be exacerbated from the SWAN cohort have indicated that women with

by disordered breathing due to obstructive sleep apnoea, high levels of anxiety premenopausally continue to expe-

independent of body weight and age 20. Moreover, rience such anxiety through the menopausal transition,

obstructive sleep apnoea affects more women in post- whereas women with low anxiety premenopausally are at

menopause than in premenopause20. Data have emerged increased risk of developing high levels of anxiety during

in the literature linking sleep disorders with an increased and after the menopausal transition32. Thus, the meno-

risk of cognitive decline in menopausal women, particu- pausal transition might be a critical time for women who

larly with respect to attention, episodic memory and are susceptible to anxiety disorders32.

executive function21. Furthermore, cognitive function

was found to be worse in early postmenopausal women Cognitive changes. Perimenopausal women often report

at high risk of obstructive sleep apnoea compared to a decline in memory and concentration (FIG. 1), which

those at low risk of sleep apnoea22. might be distressing and is clinically relevant 33. Data

from the SWAN cohort analysing cognitive function

Depression and anxiety. The menopausal transition is longitudinally over a 4‑year period have demonstrated

a vulnerable period for the onset of depressive symp- that there is a reduction in cognitive performance, spe-

toms (FIG. 1). Longitudinal studies and meta-analyses cifically a lack of learning, but that it is isolated to the

have shown that women in the menopausal transition perimenopausal stage of the transition34. More specif-

and early postmenopausal years are more likely to report ically, a lack of improvement in verbal memory was

a depressed mood than premenopausal women23–26. In reported in the early and late perimenopausal stages, and

the SWAN cohort, data collected from the Center for deficits in processing speed with repeated testing were

Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES‑D) ques- seen in the late perimenopausal stage compared with

tionnaire — which evaluated sadness, loss of interest, the premenopausal and postmenopausal stages34. These

appetite, sleep, concentration, feelings of guilt, tiredness, data suggest that the detrimental effect of menopause

agitation and suicidal ideation24 — showed that across on cognitive performance is transient and limited to the

5 years, women were substantially more likely to report perimenopausal stage. In addition, other longitudinal

Obstructive sleep apnoea

A sleeping disorder caused by a high symptom score during early perimenopause, late studies examining women in the menopausal transi-

repetitive upper airway perimenopause and postmenopause compared with tion have indicated modest declines in processing speed

collapse during sleep, leading premenopause, and also during late perimenopause and verbal episodic memory (delayed recall)24,35,36. In a

to intermittent hypoxia and compared with early perimenopause25. Extended lon- study published in 2017, the estimated rates of cognitive

characterized by loud snoring,

apnoea during sleep, insomnia,

gitudinal data from this same cohort confirmed these decline over a 10 year period were reported as 4.9% of

excessive daytime sleepiness, observations27. With respect to major depression, the the mean baseline score for processing speed and 2%

morning headache and fatigue. lifetime prevalence of this disorder is >20% in women of the mean baseline score for delayed recall37.

NATURE REVIEWS | ENDOCRINOLOGY ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION | 3

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

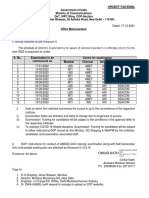

Central nervous system Skin, mucosal and hair changes Moreover, the presence of moderate to severe vasomotor

• Vasomotor symptoms • Reduced skin thickness symptoms has been associated with a greater number of

• Sleep disruption • Reduced elasticity complaints of poor memory function41. Finally, as sleep

• Depression and anxiety • Reduced hydration

• Cognitive changes • Increased wrinkling is important for learning and memory consolidation42,

• Migraine • Hair loss it is very plausible that disordered sleeping, particularly

sleep apnoea22, contributes substantially to the memory

lapses reported by many perimenopausal women.

Migraine. The prevalence of migraine during meno-

pause ranges from 10% to 29%43 (FIG. 1). It seems that

women who are susceptible, particularly those with

Weight and metabolic changes

premenstrual migraine during fertile years, have more

• Weight gain migraine headaches as they transition through meno-

• Increased visceral adiposity pause44. In community-based studies, the prevalence

• Increased waist circumference

Sexual function of migraine headache in women migraineurs has been

• Decreased sexual desire reported to increase in perimenopause and decrease in

• Dyspareunia

postmenopause44. Importantly, a study that enrolled a

large number of women reported that the risk of high fre-

quency headache was markedly increased in women dur-

Urogenital system ing perimenopause compared with premenopause34,45;

• Vaginal dryness high frequency headaches affected 8% of premenopau-

• Vulvar itching and burning

• Dysuria sal women, compared with 12.2% of perimenopausal

• Urinary frequency women and 12% of postmenopausal women.

• Urgency

• Recurrent lower urinary Musculoskeletal system

tract infections • Joint pain Weight and metabolic changes

• Sarcopenia

One of the main complaints from women at midlife

is increased weight 46 (FIG. 1). Indeed, the prevalence of

obesity is higher in postmenopausal women than in pre-

menopausal women46. Absolute weight gain in women

at midlife seems to be fundamentally related to age-

ing rather than to menopause itself 46. In women aged

40–55 years, the average weight gain was reported by

one study to be 2.1 kilograms over 3 years47. What seems

to be menopause-dependent is a redistribution of body

Nature Reviews | Endocrinology fat 47,48 characterized by accumulation of mostly visceral

Figure 1 | Overview of menopausal symptoms. Symptoms of menopause include

central nervous system (CNS)-related disorders, bodily alterations related to adiposity at the trunk, leading to an increase in waist cir-

cardio-metabolic changes, musculoskeletal alterations, urogenital and skin atrophy and cumference and an obvious change in body shape47. In

sexual dysfunction. Perimenopause is associated with the worst menopausal symptom addition, studies using techniques such as dual-energy

burden, arising from neurochemical changes within the CNS leading to severe X‑ray absorptiometry (DXA), CT and MRI have docu-

vasomotor symptoms, sleep disorders and depression, which might affect cognitive mented the increase in visceral abdominal fat deposi-

function. Long-term manifestations of definite oestrogen decline result in urogenital tion in postmenopause compared with premenopause48.

atrophy and ageing of the skin, whereas osteoporosis and sarcopenia might develop

Visceral adipose tissue poses a greater health risk than

during the postmenopausal period.

subcutaneous fat and, in general, is an independent

cause of cardiovascular disease (CVD), primarily due to

Surgical menopause has more severe consequences the increase in insulin resistance and the consequent risk

on cognitive functions than natural menopause and is of developing diabetes mellitus and the metabolic syn-

associated with an increased risk of cognitive impair- drome36. Furthermore, evidence that ovarian failure is

ment or dementia in later life38. One study reported that causative of visceral fat accumulation during menopause

surgical menopause after 45 years of age was associated has come from cross-sectional49,50 and longitudinal stud-

with lower performance in verbal learning and a decline ies51,52. In support of this hypothesis, surgically induced

in visual memory compared with natural menopause, menopause seems to accelerate weight gain in the years

whereas a decrease in semantic memory was observed in following surgery compared with ovarian-sparing

women who underwent oophorectomy before 45 years hysterectomy or natural menopause53.

of age39. Interestingly, oophorectomy after natural meno

Surgical menopause pause is not associated with alterations in cognitive Cardiovascular changes

Menopause induced by the performance39. Atherosclerosis and the risk of cardiovascular adverse

surgical removal of the ovaries. In the SWAN cohort, although the cognitive deficits events increase in women after menopause, which might

observed during perimenopause are independent of be due in part to the production of pro-inflammatory

Visceral adiposity

Accumulation of adipose tissue

mood symptoms, women with more depressive symp- cytokines and adipokines in visceral adipose tissue54,55.

in the abdomen and around toms displayed a worse processing speed, and those with Increased deposition of visceral fat in postmenopau-

internal organs. higher degrees of anxiety had a poorer verbal memory 40. sal women might be associated with fat accumulation

4 | ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION www.nature.com/nrendo

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

in other visceral tissues such as the heart 56. Indeed, it Urogenital symptoms

has been reported that late perimenopausal and post Although they are not frequently reported, urogenital

menopausal women have markedly greater volumes symptoms are often present after menopause63 (FIG. 1)

of heart fat than premenopausal women independ- and include vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, vulvar

ent of age, race, obesity or other covariates57. Notably, itching and burning, dysuria, urinary frequency and

blood lipid profiles tend to become atherogenic in urgency and recurrent lower urinary tract infections64.

women within the year following the FMP, with major The US Real Women’s Views of Treatment Options for

increases in total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol and apo- Menopausal Vaginal Changes (REVIVE) survey high-

lipoprotein B (APOB), independent of ethnicity, age or lighted a reluctance among postmenopausal women to

weight 58. Moreover, the anti-atherogenic effect of HDL address these symptoms with their health-care provid-

cholesterol seems to be abolished as women transition ers, causing a delay in their management 65. The inter-

through menopause; increases in HDL cholesterol levels national Vaginal Health: Insights, Views and Attitudes

are, at this stage, independently associated with greater (VIVA) study reported the prevalence of individual

progression of carotid intima–media thickness59. The urogenital symptoms in a large cohort of women with

markedly reduced exposure to oestrogen during meno vaginal discomfort as 83% for vaginal dryness, 42% for

pause might have a negative effect on endothelial cell pain during intercourse, 30% for involuntary urination,

growth and reduce the inhibitory effect of female sex 27% for soreness, 26% for itching, 14% for burning and

hormones on the growth and proliferation of vascular 11% for pain when touching the vagina66. In the same

smooth muscle cells60. Moreover, although blood pres- study, 62% of women with vaginal discomfort reported

sure levels seem to be lower on average in premeno- the severity of these symptoms as moderate or severe66.

pausal women than in their male counterparts, this The recent European REVIVE survey — which included

advantage is lost around the time of menopause, and the largest cohort of postmenopausal women studied

blood pressure levels start to rise in women, reaching to date — confirmed that vulvovaginal atrophy is still

levels similar to those of men of the same age group61. underdiagnosed and undertreated67. It is widely accepted

The prevalence of salt sensitivity also increases in post- that this group of symptoms — now termed genitouri-

menopausal women and doubles as early as 4 months nary syndrome68 (BOX 1) — typically manifests 4–5 years

after surgical menopause, therefore contributing to after menopause in the presence of stably low levels of

their increased risk of developing hypertension 61. oestrogen. Longitudinal studies have also reported an

Taken together, these negative changes in cardiovascu- increase in urinary incontinence symptoms with meno

lar features increase the risk of adverse cardiovascular pause69,70; however, it is unclear whether this change

events, a risk that is even greater in women younger is attributable to the menopausal transition itself or to

than 45 years who experience premature or early-onset the concomitant weight gain that typically occurs dur-

menopause62 (FIG. 1). ing this time69. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that

an increase in body weight of 1 kg is associated with a

higher incidence of urinary incontinence in women at

Box 1 | Origin and clinical characteristics of genitourinary syndrome

midlife70. Furthermore, cross-sectional studies have also

affirmed that menopausal status per se is not a determi-

Oestrogen receptors (ERα, ERβ) are present in the vagina, vestibule of the vulva, nant of urinary incontinence71; the risk of developing

urethra and trigone of the bladder; in different myofascial structures and ligaments stress incontinence increases with obesity and parity,

such as utero-sacral ligaments, levator ani muscles and pubo-cervical fascia; and also whereas the risk of urge urinary incontinence increases

on autonomic and sensory neurons in the vagina and vulva68,162. The highest

with age. Moreover, mixed incontinence is positively

concentration of ERs is in the vagina, with ERα being the only active form

after menopause.

correlated with higher BMI and hysterectomy 71.

Genitourinary syndrome symptoms are manifestations of the changes that occur at

menopause due to oestrogen withdrawal. Loss of lubrication, burning, dryness, Sexual dysfunction

itching and entry dyspareunia with fissuring are some of the vulvovaginal Longitudinal and cross-sectional studies have reported

symptoms64,68. Urinary symptoms include recurrent urinary tract infections, urgency that the menopausal transition is associated with a

and urge incontinence, stress incontinence, dysuria and voiding issues67,68. These decrease in sexual desire, independent of ageing 72 (FIG. 1).

might enhance loss of libido and sexual dysfunction in terms of arousal and orgasm. Specifically, the menopausal transition is characterized

Signs of genitourinary syndrome are numerous and heterogeneous and consist of by a change in hormone-driven sexual desire73. The

decreased elasticity and moisture, labia minora resorption, pallor, erythema, decline in sexual function in perimenopausal women is

loss of vaginal rugae, tissue fragility, loss of hymenal remnants, introital retraction,

greatest between 20 months before the FMP and 1 year

urethral eversion or prolapse, prominence of urethral meatus and recurrent urinary

tract infections64,68,160.

after the FMP74, and women seem to exhibit a decrease

The aim of management and treatment of genitourinary syndrome is to provide in sexual desire and an increase in painful intercourse

symptom relief. However, counselling for genitourinary syndrome symptoms is also beginning in late perimenopause72. Curiously, masturba-

an appropriate time to discuss lifestyle, diet and exercise, smoking cessation and tion — a behaviour that is not dependent on partner sta-

appropriate alcohol consumption. Treatment will depend on the signs and symptoms tus — increases temporarily in early perimenopause and

and degree of severity. Nonhormonal therapies include personal lubricants, vaginal declines thereafter in postmenopause72. Sexual activity

moisturizers and vaginal laser treatment (of which the long-term safety and continues to decrease, but at a slower rate, throughout

effectiveness have not been established). Hormonal therapies include vaginal oestriol the 5 years following the FMP, independently of vaginal

cream or pessaries, vaginal oestradiol tablets or systemic hormone therapy dryness, lubricant use or mood disorders74. Further on,

(menopause hormone therapy).

vulvovaginal symptoms can add to sexual dysfunction

NATURE REVIEWS | ENDOCRINOLOGY ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION | 5

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

and interfere with social, interpersonal and psycho there is a loss of collagen-producing dermal fibroblasts

logical well-being as the consequent dyspareunia can and reduced elastin proteoglycan content and water

lead to avoidance of sexual intimacy with a partner 73. retention87. Moreover, similar changes occur in the

Indeed, the European REVIVE study reported that pain mucosa of the orogastrointestinal and urinary tracts,

during intercourse has a substantially negative influence which also become more fragile. Moreover, menopause

on sexual satisfaction67. In addition, a decline in general seems to increase susceptibility to mucosal injury and

self-esteem and well-being after menopause might also delay mucosal healing owing to a less robust humoral

contribute to the loss in sexual intimacy with a partner 75. and cellular immune response and to increased per-

Nonetheless, being in a long-lasting relationship seems meability of the mucosa to pathogens in the presence

to preserve a satisfying sexual life, even in older late of oestrogen deficiency 88. Changes in hair distribution

menopausal women73. might also occur at menopause with the appearance of

facial terminal hairs and a decrease in body and scalp

Musculoskeletal symptoms hair 89 (FIG. 1). Hair loss in perimenopausal women usu-

A major concern in menopausal women is a decline in ally appears as a dispersed thinning of hair, primarily in

bone health. Postmenopausal osteoporosis is a degen- the central and forehead region, and can also occur

erative bone disorder characterized by reduced BMD in parietal and occipital regions89.

(FIG. 1) and altered bone structure, such as thinning and

increased porosity of the cortex and decreased connec- Personal and social impact

tivity of trabeculae76. Osteoporosis increases the risk Midlife is a time of profound personal and social change

of fractures76 — which occur most frequently in the for women. The perception and interpretation of meno-

spine, hip and wrist in postmenopausal women with pausal symptoms, and therefore their interference with

osteoporosis77 — and might lead to long-term disability. day‑to‑day life, are influenced by social and cultural

Although there are minimal changes in BMD during beliefs90. On an international level, ~20% of women

premenopause or early perimenopause, BMD sharply perceive menopause as a disease, even if they are not

declines during late perimenopause78. The annual rates necessarily fully aware of its symptoms and health

of bone loss after the FMP are estimated to be 1.8–2.3% implications90,91. Depending on personal and working

in the spine and 1.0–1.4% in the hip78. Epidemiological characteristics, even mild menopausal symptoms can be

studies have shown that the incidence of wrist and spine distressing for some women, and most women with per-

fractures in postmenopausal women rises before hip frac- vasive menopausal symptoms will experience profound

tures77; this observation seems to be related to the rapid trouble in coping with daily life.

bone loss that occurs in the first 3–5 years after meno The personal experience of menopausal symptoms,

pause, which primarily affects trabecular bone tissue, particularly bodily changes that occur related to ageing

whereas that which occurs in the following 10–20 years and the awareness of the loss of fertility, can alter self-

involves both trabecular and cortical bone76. image. Life events might produce a change of role and/or

Changes in body composition that occur in women identity around the time of the menopausal transition.

at midlife also affect lean muscle mass (FIG. 1), which, The empty nest syndrome, retirement from work, hav-

as opposed to fat mass, seems to decrease79. Although ing frail or ill parents and the loss of a parent or partner

sarcopenia cannot be currently attributed to meno- are all conditions that frequently occur at midlife. These

pause, this degenerative process is more evident in age- new conditions imply a depletion of personal and social

ing women than ageing men and seems to occur more networks, a repositioning towards a less prestigious sta-

rapidly after menopause80,81. Resistance exercise82 and tus, an increase in caregiving activities, with an overall

adequate dietary protein intake70 are important lifestyle decline in quality of life91. Thus, midlife and the meno-

factors that help to maintain lean muscle mass and pausal transition are often perceived as a time of crisis

consequently preserve mobility and postural stability, by women, and the presence of distressing menopausal

reducing the risk of falls and bone fractures. symptoms adds to the perception of deteriorating mental

In addition, the prevalence of osteoarthritis increases and physical well-being with indirect consequences on

greatly after the FMP83, and pain specifically affecting health92. Nonetheless, many women perceive menopause

the distal interphalangeal joints of the fingers and as a natural phase of life without negative implications93.

base of the thumb due to osteoarthritis of the hand is The reasons for this interpersonal variability in the per-

a commonly reported symptom in the perimenopau- ception of menopause might be attributable to the rela-

sal period73. Although osteoarthritis of the hand dur- tive intensity of symptoms but might also depend on how

ing perimenopause usually subsides within 2–3 years, women interpret and manage these symtoms94 according

it is predictive of successive joint disease in the knee to their social position and cultural inclination95,96.

and spine84. With respect to knee osteoarthritis, most Approximately 30–40% of women report that men-

affected women report the onset of symptoms during opausal symptoms reduce performance in the work-

perimenopause or within 5 years of the FMP85. place94, and the most disruptive symptoms are hot

flashes, insomnia, a feeling of tiredness and poor concen-

Skin, mucosal and hair changes tration96. Even in women who are not heavily burdened

Menopause reduces skin thickness, elasticity and by menopausal symptoms, the cost is often paid in terms

hydration and leads to an increase in wrinkling 86 (FIG. 1). of perception of worsened social desirability and feel-

Structural changes occur mainly in the dermis where ings of shame or embarrassment, which are sometimes

6 | ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION www.nature.com/nrendo

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

due to unwelcome comments from colleagues94,97–99. was associated with higher climate temperatures, and

Targeted strategies to make the menopausal transition these symptoms were more frequent and problematic

and its symptoms recognized socially and accepted for women living in higher temperature and lower alti-

in the workplace94,95,100 — such as promoting self-help tudes112. However, the frequency and severity of these

readings, specific training, flexible working hours or symptoms were not influenced by seasonal variation in

shift changes and reviews of workplace ventilation and temperature112, an observation that was confirmed

temperature — have proved valuable in helping women in studies involving women from other continents109,110.

to share their experiences with peers and together seek As previously stated, menopausal women have an

solutions and develop coping strategies. increased risk of cardiovascular events65,66; however, this

elevated risk seems to be higher in black postmenopau-

Incidence and prevalence of symptoms sal women with obesity than in white postmenopausal

International and interethnic epidemiological studies women with obesity, even in the absence of the metabolic

have shown that the incidence and prevalence of men- syndrome113.

opausal symptoms might vary according to the study Skin ageing at menopause also varies according to

population. Individual characteristics and comorbidi- skin colour. In a study that enrolled menopausal women

ties also have a role in the manifestation of menopausal within 36 months of the FMP, black women were shown

symptoms. to have lower skin wrinkling scores over a period of

4 years than white women, possibly due to the lower sus-

Ethnic differences ceptibility of black women to photoageing 114. Skin rigid-

Differences in the age of natural menopause have been ity, a measure of collagen and water content in skin that

reported on a global level. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis changes rapidly in response to oestrogen deprivation, was

of 36 international studies evaluating age at natural also positively correlated with the time since menopause,

menopause reported an overall mean of 48.78 years, with but only in the white subpopulation of the study 114.

a range of 46 to 52 years101. The age at menopause was Regarding sexual functioning, African-American

reported to be generally lower in women from African, women transitioning through menopause report a

Latin American, Asian and Middle Eastern countries higher frequency of sexual intercourse than other ethnic

and was the highest in Europe and Australia, followed groups83. Moreover, North American women of Chinese

by the USA101. and Japanese descent have been reported to be less sex-

Disparities in reported symptoms of menopause ually active and attribute less importance to this aspect

have been described among women of different eth- than Western women83. However, data from the pan-

nicities and/or geographical regions. Although the Asian REVIVE survey have revealed that genitourinary

nature of menopausal symptoms is common to women syndrome is underdiagnosed and undertreated in Asian

of all geographical regions and ethnicities, the preva- women and that, when present, vaginal dryness and

lence of certain symptoms varies considerably. Women irritation have the greatest negative influence on sexual

of European and Latin American ethnicity predom- enjoyment and intimacy in this demographic115.

inantly have CNS-related symptoms, including hot The prevalence of osteoporotic fracture in postmeno

flashes, sleeplessness, mood changes, irritability and pausal women, mostly involving the hip, varies consid-

reduced sex drive102–104. In North America, where the erably across the world, with the highest prevalence in

population is multiethnic and comprises women of Scandinavia and lowest prevalence in Africa116. Within

African-American, Asian and Hispanic descent as well the European continent, the highest rates of osteoporotic

as white women, the SWAN study reported that vaso- fracture are recorded in northern countries compared

motor symptoms were more prevalent among African- with the more southern Mediterranean countries,

American and Hispanic women and less prevalent presumably owing to differences in sun exposure and

among Japanese-American and Chinese-American therefore endogenous production of vitamin D, which

women than among white women105. However, emerg- is essential for calcium absorption and bone mineral-

ing analyses of studies performed in Thailand, China ization117. Interestingly, the rate of hip fractures has

and Singapore report that the prevalence of hot flashes increased threefold in China over the past 25 years,

and/or night sweats in Asian women is similar to those which might be attributable to westernization and a shift

of Western countries106,107. The prevalence of vasomotor towards a more sedentary lifestyle118.

symptoms was also reported to be lower in India and

in Middle Eastern countries, such as the United Arab Individual differences

Emirates and Saudi Arabia, with respect to Western A woman’s experience of menopause is extremely per-

countries108–110. African-American women tend to have sonal, and therefore the incidence and prevalence of

vasomotor symptoms that are particularly persistent symptoms, particularly CNS-related symptoms, are

compared with the average 7.4 years20, with a median influenced by personal characteristics, personal history

total duration of 10.1 years20; however, this might be and environmental factors.

due to the higher rate of obesity in African-American

women than in other ethnicities in North America111. Personal history. A strong predictive association has

In addition, a multicentre study involving Spain and been described between somatic anxiety and the risk

Spanish-speaking Latin American countries revealed of menopausal hot flashes119. Anxiety, perceived stress

that the prevalence of hot flashes and night sweats and depressive symptoms also seem to lead to persistent

NATURE REVIEWS | ENDOCRINOLOGY ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION | 7

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

vasomotor symptoms20. Interestingly, one study120 reported household incomes and social support, poor educa-

that women who have experienced one or more form of tion, fair or poor general health and a history of surgical

abuse over the previous year, mostly verbal and/or emo- menopause and stressful life events132.

tional abuse, have higher scores for menopausal symp-

toms such as sleep disturbances, decline in cognitive Physiology of menopausal symptoms

function, bowel and bladder dysfunction, lower sexual Menopausal symptoms arise from the failure of ovar-

activity and decline in general health but not for hot ian function owing to the depletion of ovarian folli-

flashes and night sweats. In addition, women who have cles5 (FIG. 2). This process involves a series of hormonal

experienced moderate to severe premenstrual syndrome alterations over a period of years, a period known as

have an increased risk of developing depression, poor menopausal transition, beginning with the decline in

quality of sleep, feeling less attractive and, in particu- levels of inhibin B, resulting in a decline in their nega-

lar, memory and concentration problems after meno- tive feedback action on the follicle-stimulating hormone

pause121. Conversely, a history of hypertensive diseases (FSH) release from the pituitary 1,5. Increases in FSH

during pregnancy seems to predispose women to more levels of follow, promoting erratic increases in oestra-

severe and persistent hot flashes and night sweats122. diol secretion. This has been demonstrated in a study

of women classified according to the STRAW staging

Obesity. Excess adiposity is a major factor that influ- system as mid-reproductive age, late-reproductive age,

ences a woman’s quality of life during the menopausal early menopausal transition and late menopausal tran-

transition. Obesity is associated with a longer meno- sition133; in 37% of the ovulatory cycles during men-

pausal transition duration49 and a higher prevalence of strual transition, a second rise and fall in oestradiol

vasomotor symptoms123. In fact, gains in body fat over levels was observed during the mid-luteal and late-

time are predictive of risk and frequency of vasomo- luteal phase, resembling that of the follicular phase but

tor symptoms124. Moreover, concurrent BMI and waist superimposed on the luteal phase, as well as decreases

circumference measurements are positively related to in progesterone secretion. This luteal out‑of‑phase

incident vasomotor symptoms in early menopause125; increase in oestradiol levels seemed to be triggered by a

on the basis of these data, the SWAN investigators have long-term elevation of FSH levels in the follicular phase

suggested that maintaining a healthy weight during early and lower inhibin B levels early in the cycles. Moreover,

menopause might help prevent vasomotor symptoms. the unopposed oestradiol production that is associated

A SWAN substudy found that a pro-inflammatory adi- with stimulation of follicular development is exacer-

pokine profile is associated with an increased incidence bated by increases in FSH and luteinizing hormone

of vasomotor symptoms, particularly at early stages (LH) levels in response to diminished negative feedback

in the menopausal transition, suggesting that a pro- on the FSH–LH release from the pituitary due to loss

inflammatory milieu produced by adipose tissue neg- of inhibin B and progesterone1,5. Eventually, the ovary

atively affects thermoregulatory activity in the CNS126. is less responsive to gonadotropin stimulation during

Overweight also seems to be linked with a twofold to perimenopause, leading to reduced oestradiol produc-

fourfold higher incidence of urogenital symptoms in tion1. In turn, LH stimulation is blunted and insufficient

women with normal weight, including vaginal dis- to elicit ovulation.

charge, itching and irritation127, and increases the risk Anovulation leads to the loss of progesterone produc-

of developing urinary incontinence128. Body weight and tion1,5. Conversely, the postmenopausal ovary continues

body composition are also relevant to the incidence of to contribute substantially to the circulating levels of tes-

osteoporotic fractures. Weight loss in older women is tosterone for years134. Moreover, serum concentrations of

associated with a general increased risk of fracture129, adrenal androgens in midlife women might variably and

whereas weight gain is associated with a reduced risk of transiently increase in the late menopausal transition135.

hip fractures but an increased risk of other peripheral In particular, a rise in mean serum concentrations of

fractures, such as wrist fractures130. dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) occurs in

most women between the early menopausal transition

HIV infection. HIV infection in menopausal women is and early postmenopause stages135. This changing hor-

associated with more severe hot flashes compared with monal environment produces a cascade of CNS-related

women who are not infected with HIV, independent of and peripheral symptoms of variable severity for an

CD4+ T cell count or duration of HIV positivity, and unpredictable amount of time.

leads to interference with daily activities and a lower

quality of life131. More support should be provided for Vasomotor symptoms and sleep disruption

Premenstrual syndrome women who are HIV positive in coping with meno- Alterations in thermoregulation are the leading hypo

A heterogeneous group of

pausal symptoms, as a reduction in quality of life might thesized mechanisms underlying vasomotor symp-

emotional symptoms, such as

irritability and food cravings, reduce adherence to anti-retroviral therapy 131. toms136. Menopause is associated with a reduction in

and physical symptoms, such the thermoneutral zone of the body, meaning that

as bloating, breast tenderness Socioeconomic status. Approximately 5% of perimen- minor increases in core body temperature can trigger

and abdominal pain, that opausal women experience symptoms in clusters132. In an excessive thermoregulatory reaction and promote

precede the menstrual period.

particular, symptoms related to mood, sleep and sexual heat dissipation by peripheral vasodilation and sweat-

Anovulation activity arise simultaneously, and factors that favour the ing 137. The thermoregulatory circuit is composed of

The absence of ovulation. emergence of these clustered symptoms include low functional elements that are under catecholaminergic

8 | ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION www.nature.com/nrendo

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

and/or serotonergic control138, and the hypothalamus is role in stabilizing the thermoneutral zone. Indeed, vas-

ascribed a key role in the integration of thermal informa- omotor phenomena are more common in periods of

tion and in the control of thermoregulatory reactions138. amenorrhoea, which are characterized by fluctuations

During perimenopause, hormonal cycles desynchronize, in oestrogen levels139. The slow progression, reduction

leading to erratic levels of sex hormones, which often peak and final disappearance of vasomotor symptoms dur-

and plummet133. Thermoregulatory dysfunction might be ing menopausal transition suggest a readjustment of the

a result of a maladaptation of the brain to this acyclicity, brain to the different concentrations of hormones and

with alterations in the function of noradrenergic and sero- neurotransmitters, a process that might require a variable

toninergic pathways137 (FIG. 2) that normally have a decisive amount of time, depending on the individual.

b

a

Mood and cognitive functions:

Vasomotor symptoms neuroendocrine activity

and sleep disruption ↑ Noradrenaline ↓ GABA-ergic function

↑ Noradrenaline ↓ Dopamine ↓ β-endorphin

↓ Dopamine

↓ Serotonin

↓ Serotonin ↓ Allopregnanolone c

↓ Androstenedione ↓ DHEA Urogenital symptoms,

↑ Neurokinin B ↓ Testosterone ↓ DHEAS

↑ Kisspeptin libido and sexual arousal

↓ E2 ↑ Cortisol ↓ E1

↑ Dynorphin ↑ Amyloid-β ↑ Cortisol:DHEA ratio

↑ Cortisol ↓ E2

↓ Androstenedione

g ↓ Testosterone

↓ Inhibin B ↓ DHEA

Skin ageing ↓ DHEAS

and hair changes ↑ FSH

↓ Oestrogen:androgen ratio ↑ LH

↓ Testosterone ↓ E2

↓ Dihydrotestosterone ↓ Progesterone

d

f Metabolic and cardiovascular changes

Bone remodelling ↑ LDL cholesterol ↓ HDL cholesterol

↓ E2 ↑ IL-1 e ↑ FFA ↓ SHBG

↑ N-telopeptide ↑ IL-6 Muscle changes ↑ Triglycerides ↓ GH

of type 1 collagen ↑ TNFα ↓ GH ↑ Cortisol ↓ IGF1

↑ C-terminal telopeptide ↓ TGFβ ↓ IGF1 ↑ Testosterone ↓ GH:IGF1 ratio

of type 1 collagen ↑ T-cell activation ↓ IGFBP3 ↑ Leptin ↓ Adiponectin

↑ Pyridinoline crosslinks ↓ Testosterone ↑ Renin–angiotensin ↓ NO

system

Figure 2 | Endocrine implications of menopausal symptoms and changes. After menopause, NaturetheReviews | Endocrinology

ovaries are depleted of

follicles, oestradiol (E2) and inhibin B production falls and ovulation and menstruation no longer occur. The loss of ovarian

sensitivity to follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) and the loss of negative feedback of E2 and

inhibin B on the hypothalamic–pituitary unit result in increased production and release of gonadotropin release hormone

(GnRH), FSH and LH. Increased FSH levels are particularly specific to postmenopause. a | Modifications of gonadotropins, E2,

alterations in the function of noradrenergic and serotoninergic pathways, and opioid tone in the hypothalamus cause the

onset of vasomotor symptoms and consequent sleep disruption. Thermoregulatory dysfunction might be a result of a

maladaptation of the brain to kisspeptin, neurokinin B and dynorphin (KNDy) neuron hypertrophy, which project to the

preoptic thermoregulatory area. b | Mood, cognitive functions and neuroendocrine activity, which are closely related to

the impairment of GABAergic, opioid and neurosteroid neurotransmitter milieu in the central nervous system (CNS), occur

with ageing. Failure of the main target of neurosteroids, the GABA‑A receptor, to adapt to changes in levels of

allopregnanolone over the course of the menopausal transition might lead to depressive symptoms, mood and cognitive

dysfunctions. c | Peripheral levels of oestrogen (oestrone (E1), and E2) withdrawal affects all the tissue expressing oestrogen

receptors (ERs), such as the epithelial tissues of the bladder trigone, urethra, vaginal mucosa, pelvic muscles, and fascia and

gastrointestinal mucosa, leading to vulvovaginal atrophy and urogenital symptoms, the so-called genitourinary syndrome.

The menopausal condition induces reductions in oestrogens and ovarian and adrenal steroids (testosterone,

androstenedione, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS)), which might contribute

to the onset of sexual dysfunction. d | Increased levels of LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, free fatty acids (FFA), cortisol and

testosterone, together with the decreased levels of HDL cholesterol, sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), growth

hormone (GH), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) and the GH:IGF1 ratio, facilitate the onset of menopausal metabolic

syndrome, which is characterized by an altered lipid profile, hyperinsulinaemia, increased gluconeogenesis, abdominal

obesity and overweight with a consequent rise in cardiovascular risk. e | Loss of oestrogen exposure leads to a progressive

decline in levels of GH and IGF1 and their binding protein insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 (IGFBP3), which

reduces muscle mass. The associated decline in androgen production is responsible for the onset of sarcopenia.

f | Circulating E2 levels decline after menopause, and bone resorption exceeds bone formation. Loss in bone mass is

demonstrated by the rise in circulating levels of bone resorption markers, such as N‑telopeptide of type 1 collagen,

C‑terminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen and pyridinoline crosslinks. In bone, oestrogen deficiency also leads to immune

cell activation, resulting in increased pro-inflammatory cytokine levels. g | Dihydrotestosterone, the peripherally active

form of testosterone, is responsible for the gradual involution of scalp hair follicles in androgenic alopecia and hair

changes. NO, nitric oxide; TGFβ, transforming growth factor-β; TNFα, tumour necrosis factor-α.

NATURE REVIEWS | ENDOCRINOLOGY ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION | 9

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

Although initial studies reported that LH pulses occur neuropeptides (such as β‑endorphin and neurosteroids,

during hot flashes in postmenopausal women, a causative namely, allopregnanolone and dehydroepiandrosterone

link was never found139. The emerging hypothesis link- (DHEA)) (FIG. 2) and can also influence the electrical

ing these two events temporally involves the discovery excitability, function and morphological features of the

that kisspeptin, neurokinin B and dynorphin (KNDy) synapses148. Thus, unstable levels of oestrogen during

neurons, which project to the preoptic thermoregula- perimenopause might cause the transient cognitive defi-

tory area, also regulate the hypothalamic GnRH pulse cits that are observed clinically at this time148. However,

generator, most likely by mediating oestrogen-dependent the link between circulating levels of oestradiol and cog-

negative feedback of LH secretion140. At postmenopause, nitive impairment is not well established, and clinical

KNDy neurons undergo hypertrophy, and the expres- trials evaluating hormone therapy in women at midlife

sion of the genes encoding neurokinin B and kisspeptin have not shown improvements in cognition45. It has been

increases as a result of oestrogen withdrawal, leading to shown that the concomitant rise in LH levels that occur

increased signalling to heat dissipation effectors in the with ovarian failure might drive both cognitive dysfunc-

CNS and to GnRH neurons140 (FIG. 2). tion and loss of spine density in an independent man-

There is also evidence in the literature that severe ner 149. Indeed, animal studies have shown that lowering

vasomotor symptoms are associated with activation of the peripheral levels of LH using leuprolide acetate, a

the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis, as increased GnRH agonist, improved cognition and spatial memory

urinary cortisol secretion has been reported during the and increased spine density 149. Persistently high levels

late menopausal transition stage in women with severe of FSH and LH have been linked to Alzheimer disease in

vasomotor symptoms compared with women who have postmenopausal women, and it is hypothesized that these

mild complaints141, and higher salivary cortisol levels hormones might be responsible for increased production

have also been associated with more frequent, severe of amyloid‑β, a main constituent of senile plaques150.

and bothersome daily self-reported hot flashes142. Higher Indeed, pharmacological suppression of LH and FSH

circulating concentrations of cortisol and noradrenaline using leuprolide acetate reduced plaque formation in

were also reported in women at the menopausal tran- animal models of Alzheimer disease151.

sition or the early postmenopausal stages who experi- According to the oestradiol withdrawal hypothesis,

enced vasomotor symptoms143. Increased cortisol might migraine in women are triggered by the sudden decline

activate a stress response with a consequent increase in in oestrogen levels that occurs immediately before

catecholamines, adrenaline and noradrenaline, which, menses, during the menopausal transition or in the

in turn, induce vasodilation141. early postmenopausal period152. There is accumulat-

The biological mechanisms underlying the sleep dif- ing evidence that changes in oestradiol levels in the

ficulties that develop during menopausal transition are brain might precipitate a kind of neurogenic inflam-

still unclear. Lower levels of inhibin B, a marker of the mation that is characterized by vasodilation, release

early menopausal transition, have been found to strongly of pro-inflammatory mediators and plasma extra

predict poor sleep quality 39,144 in women at late meno- vasation153, leading to the typically reported throbbing

pausal transition and at postmenopause, whereas higher and pulsing pain.

mean urinary FSH levels, the hallmark of ovarian failure,

have been associated with poor sleep quality in premen- Mood changes

opausal and perimenopausal women50,145. In addition, a The most accredited likely biological hypothesis under-

faster rate of increase in FSH levels has been associated lying changes in mood is that fluctuations in levels of

with longer sleep duration, indicative of less restful sleep steroid hormones, more than their decline, might trigger

and more non-REM sleep24. Postmenopausal women also perimenopausal depression154. It seems that the longer

show an advanced onset of melatonin release compared the duration of the menopausal transition, and there-

with premenopausal women146; therefore, advanced cir- fore the longer the exposure to fluctuating hormones,

cadian phase might contribute to early morning awak- the greater the risk of perimenopausal depression155.

ening, a common complaint in menopausal women35. In the Penn Ovarian Ageing Study 156, it was found that

Furthermore, obstructive sleep apnoea might exacerbate a more rapid rise in FSH levels before the FMP was pre-

these sleep difficulties in menopausal women. Reduced dictive of a lower risk of depressive symptoms after the

levels of progesterone, a respiratory stimulant, in peri- FMP, suggesting that a shorter menopausal transition

menopausal woman might be the underlying cause of protects against perimenopausal depression. A subset

this nocturnal breathing disorder 147. of perimenopausal women might have an increased

sensitivity to changes in gonadal steroids, specifically

Cognitive changes and migraine oestrogens and progesterone, which in turn modulate

Oestradiol is believed to have a major role in cognitive neuroregulatory systems associated with mood and

performance as anatomical studies have demonstrated behaviour 154. In particular, fluctuating oestrogen levels

that the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, which medi- might lead to dysregulation of serotonin and noradren-

ate episodic and working memory, express high levels of aline pathways in the CNS as oestrogen facilitates a

oestrogen receptors (ERs)148. In these areas of the CNS, number of actions of serotonin and noradrenaline, spe-

oestradiol-dependent activation of ERs can modulate the cifically by modulating receptor binding and the avail-

synthesis, release and metabolism of neurotransmitters ability of these neurohormones at the synaptic level154.

(such as serotonin, dopamine and acetylcholine) and In an interesting theoretical model157, fluctuations in

10 | ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION www.nature.com/nrendo

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

progesterone-derived neurosteroids, particularly allo- partner are negatively associated with FSH levels163, the

pregnanolone, caused by changes in oestradiol and pro- summiting of which marks ovarian failure. Moreover,

gesterone levels might underlie menopause-associated waning oestrogen levels in the late menopausal transi-

depressive symptoms. In particular, failure of the tion lead to decreased vascular congestion and lubrica-

GABA-A receptor — the main target of neurosteroids — tion of the vagina, resulting in unsatisfactory or painful

to adapt to changes in levels of allopregnanolone (FIG. 2) intercourse165.

over the course of the menopausal transition might lead

to depressive symptoms in vulnerable women, such as Metabolic and cardiovascular changes

those with a history of premenstrual dysphoric disorder From an endocrinological perspective, longitudinal

and/or postpartum depression157. The inability to main- studies have revealed that the menopausal transition is

tain GABAergic homeostatic control might exacerbate characterized by a shift from a predominately oestro-

the response of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal genic hormonal state to an androgenic state owing to

axis to stress. Indeed, there is increasing evidence that an increase in bioavailable testosterone levels3,62,166. The

dysregulation of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal menopausal ovary continues to produce high amounts

axis, which is correlated with oestradiol fluctuation, of androgen for years after menopause, and the increase

might be implicated in the pathophysiology of peri- in gonadotropin levels drives ovarian androgen secretion

menopausal depression158. Moreover, very stressful life despite the substantial decline in oestrogen levels123. Sex

events seem to contribute greatly to the onset of depres- hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) levels decrease with

sive symptoms during the menopausal transition in the decreasing oestrogen concentrations, thereby increas-

presence of oestradiol variability 159 (FIG. 2). ing the free androgen index and enhancing the imbal-

ance between oestrogens and androgens3 (FIG. 2). The

Urogenital symptoms and sexual function increase in bioavailable testosterone can stimulate fat

The lower genital and lower urinary tracts share a com- accumulation in preadipocytes of visceral fat 64. Visceral

mon embryonic origin in the female and express high fat adipocytes express high levels of androgen receptors

numbers of ERs during the reproductive years160; as a that are downregulated by oestrogens167; therefore, when

result, both of these tissues are affected by long-term oestrogen levels decline, visceral fat might become more

hypoestrogenism during menopause. From a histological sensitive to the negative effects of androgens. Indeed, it

point of view, after menopause, these tissues exhibit seems that the change in the bioavailability of androgens

reduced collagen content and hyalinization, decreased can predict accumulation of visceral fat over a period

elastin content, thinning of the epithelium, altered mor- of 5 years168. Moreover, menopausal women with more

phology and function of smooth muscle cells, increased rapidly increasing levels of bioavailable testosterone

density of connective tissue and fewer blood vessels160,161. undergo larger increases in adiposity than women with

Vaginal blood flow is reduced, as well as the lubrication more stable levels, whereas women with slowly increas-

and elasticity of the vagina, leading to shortening and ing levels of bioavailable testosterone experience smaller

narrowing of the vagina and, consequently, dyspareunia increases in adipose tissue168. Rising FSH levels might

and easy fissuring of the vaginal walls160. Approximately also contribute to this phenomenon, as the FSH receptor

20% of postmenopausal women develop urge inconti- (FSHR) is expressed in visceral fat adipocytes169, and ani-

nence, and ~50% develop stress incontinence75; however, mal studies have indicated that FSHR signalling might

only the incidence of urge incontinence is affected by increase adipocyte lipid synthesis and lead to elevated

long-term oestrogen depletion. It is hypothesized that levels of leptin and decreased levels of adiponectin in

the lack of oestrogenic activity in the trigone of the blad- serum, therefore promoting fat accumulation169.

der and the urethra might decrease the sensory thresh- In postmenopausal women, increasing levels of bio-

old and lower the urethral closure pressure and Valsalva available testosterone and decreasing SHBG levels are

leak-point pressure, therefore contributing to urinary exacerbated by insulin resistance, and low SHBG lev-

urgency 162 (BOX 1). els are predictive of incident type 2 diabetes mellitus in

Pinpointing a biological cause for sexual dysfunction postmenopausal women170. Insulin resistance and central

in menopausal women is extremely difficult due to the obesity, the hallmarks of the metabolic syndrome, occur

complexity of this domain; changes in sexual activity in many postmenopausal women171. Furthermore, the

depend on changes in sexual desire and partner satis- lack of oestrogens per se seems to favour accumulation

Urethral closure pressure

faction, dyspareunia due to vaginal dryness and general and a central distribution of adipose tissue172. Studies

The fluid pressure needed to health. Important associations between endogenous performed in human and animals have shown that

open a closed urethra. levels of reproductive hormones and sexual function oestrogens regulate food intake negatively and energy

in women going through the menopausal transition expenditure positively, promote free fatty acid (FFA)

Valsalva leak-point pressure

have been reported. Masturbation, desire and arousal uptake and triacylglyceride synthesis in gluteofemoral

The lowest abdominal pressure

required during a stress activity were positively associated with levels of testosterone adipose tissue (rather than in abdominal subcutaneous

that causes the urethra to open and DHEAS, supporting a role for androgens in female adipose tissue) and inhibit adipose tissue depot-specific

and leak. sexual function163,164 (FIG. 2). Indeed, with the exception pathophysiological processes that lead to morbidity 172.

of surgical menopause, after which testosterone lev- In addition, lower concentrations of oestradiol were

Free androgen index

An index that represents the

els tend to decrease abruptly, androgen levels do not found to be markedly associated with greater volumes

ratio of bioactive circulating decline immediately following natural menopause134. of paracardial adipose tissue in women at midlife, while

testosterone. Masturbation, arousal and the ability to climax with a the free androgen index was found to correlate positively

NATURE REVIEWS | ENDOCRINOLOGY ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION | 11

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

with fat around the aorta, and SHBG levels were found of bone resorption markers — such as N‑telopeptide of

to correlate negatively with fat in all evaluated cardio- type 1 collagen, C‑terminal telopeptide of type 1 col-

vascular depots70. Negative changes in endothelial cell lagen and pyridinoline crosslinks — increase by 90%

function might also influence the increased risk of CVD after menopause, whereas markers of bone formation

that is observed in postmenopausal women. Oestrogen increase by only 45%185 (FIG. 2). Oestrogens are known

deficiency leads to activation of the renin–angiotensin to stimulate osteoblast proliferation and differentiation,

system, as well as upregulation of endothelin, a potent therefore promoting deposition and mineralization of

vasoconstrictor 173. Conversely, oestrogen deficiency leads bone matrix, and can also induce apoptosis in osteo-

to impaired oestradiol-induced signalling, resulting in clasts. Their effect on osteoblasts, osteoclasts and oste-

the reduced release of cardioprotective nitric oxide174. ocytes occurs through activation of high affinity ERs,

Together, these changes accelerate atherogenesis in per- including the ERα and ERβ isoforms186. In bone, oestro-

imenopausal women, increasing their susceptibility to gen deficiency also leads to immune cell activation and

ischaemic heart disease and CVD. the resulting pro-inflammatory cytokine milieu further

enhances bone resorption186.

Muscle loss and bone remodelling The loss of ovarian function might also be associated