Improved Implementation of WHO Standard Tuberculosis Guidelines in Indian Health Care Facilities - A Prospective Multicenter Study

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

27 tayangan6 halamanBackground

Quality of TB care is the main aim of WHO TBIC

guidelines. But there is an aberration from these

standards in TB care resulting in delayed diagnosis,

treatment and decreased patient adherence to the

therapy. The objective of this study was to check the

applicability, identify non-compliance parameters to

that of TBIC guidelines and recommend the

improvements in health care facilities.

Method

This study was a prospective interventional study

held at 20 health care facilities offering

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniBackground

Quality of TB care is the main aim of WHO TBIC

guidelines. But there is an aberration from these

standards in TB care resulting in delayed diagnosis,

treatment and decreased patient adherence to the

therapy. The objective of this study was to check the

applicability, identify non-compliance parameters to

that of TBIC guidelines and recommend the

improvements in health care facilities.

Method

This study was a prospective interventional study

held at 20 health care facilities offering

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

27 tayangan6 halamanImproved Implementation of WHO Standard Tuberculosis Guidelines in Indian Health Care Facilities - A Prospective Multicenter Study

Background

Quality of TB care is the main aim of WHO TBIC

guidelines. But there is an aberration from these

standards in TB care resulting in delayed diagnosis,

treatment and decreased patient adherence to the

therapy. The objective of this study was to check the

applicability, identify non-compliance parameters to

that of TBIC guidelines and recommend the

improvements in health care facilities.

Method

This study was a prospective interventional study

held at 20 health care facilities offering

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Anda di halaman 1dari 6

Volume 4, Issue 3, March – 2019 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology

ISSN No:-2456-2165

Improved Implementation of WHO Standard

Tuberculosis Guidelines in Indian Health Care

Facilities - A Prospective Multicenter Study

Haripria Ramesh 1, Balakeshwa Ramaiah2, Hiranmai Chowdary3

1,2,3

Department of Pharmacy Practice, Karnataka College of Pharmacy,

#33/2, Tirumenahalli, Hegde Nagar Main Road, Bengaluru-560064, Karnataka, India

Abstract:- private sectors and weakened health care systems

[2,3,4].The TB epidemiology report of India 2017-

Background 18estimated that 27.9 lakh people suffered from TB and in

Quality of TB care is the main aim of WHO TBIC the same year 4.23 lakh people died from TB [5,6].Based

guidelines. But there is an aberration from these on WHO recommended strategy of Directly Observed

standards in TB care resulting in delayed diagnosis, Treatment Short Course (DOTS), Revised National

treatment and decreased patient adherence to the Tuberculosis Policy(RNTCP) was implemented in India in

therapy. The objective of this study was to check the 1997.The Government of India five-year TB National

applicability, identify non-compliance parameters to Strategic Plans (NSP) is carried out by RNTCP and serves

that of TBIC guidelines and recommend the over a billion people in 632districts. The treatment

improvements in health care facilities. management is carried out by the meticulous supervision at

various levels through a TB unit, at sub-district level [7].

Method

This study was a prospective interventional study The main epidemiological reasons behind TB in India

held at 20 health care facilities offering TB care in are poverty, urbanization and HIV epidemic. Quality TB

Bengaluru. A TBIC checklist was used as a tool to care is essential towards effective diagnosis and treatment

ensure the compliance in the centres towards TB care. of TB, which is also the main aim of the NSP 2012-

The reasons for non-compliance in centres were 2017[8]. But there is also an aberration from known quality

assessed and recommended for improvement. The standards in TB care resulting in delayed diagnosis,

centres were re-visited and post -interventional treatment with ineffective regimens, and decreased patient

assessment was done. adherence to the therapy due to the care providers.

Furthermore, published quality improvement projects in

Results resource limited settings tend to describe large scale

The managerial compliance was the most (97.5%). projects affecting multiple sites at the national or district

The overall compliance improvement of the level. Effectively, TB control measures are limited by the

administrative standards after intervention was quality of care provided at the primary health care

increased by 11.5% and reached 53.5%. The facilities. The current top down approach to improve TB

environmental standards were increased by 9% and care is through national policies, guidelines and through

reached 34%. Alarmingly, none of the centres had rigorous implementation of TB infection control (TBIC)

respiratory facilities and were completely non- and Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) as detailed in

complaint during pre and post intervention. the 2009 ‘WHO Policy on TB Infection Control in Health-

Care Facilities, Congregate Settings and Households’ [9-

Conclusion 17].

WHO TBIC guidelines are much needed in the

health care facilities aiding in the quality TB care and Countries may undertake a national assessment of

to strengthen the health care systems. WHO TBIC policy adaptation and implementation, and

thereafter on an annual basis to measure progress over

Keywords:- WHO TBIC, Tuberculosis, Compliance, DOT time. Standardized checklist-based assessment tools

Centre, India. facilitate efforts to track progress in TBIC implementation.

Healthcare facility-level assessment of TBIC checklist

I. INTRODUCTION should be incorporated into routine supervisory activities.

Periodic monitoring and evaluation are crucial for TB

Tuberculosis (TB) is among the ten deadliest disease program managers, general health services and other

globally [1]. The 2017-18WHO report showed 10.4 million relevant stakeholders to ensure WHO global policy on

morbidity and 1.7 million mortality estimates globally TBIC are adopted and that all health facilities have

accounting over 95% in middle and low-income countries. appropriate TBIC procedures in place [18,19]. Hence, the

Out of which India(25%), Indonesia (16%) and Nigeria main objective of this study is to check the applicability,

(8%) accounted for large gap between incidence of TB and identify the non-compliance parameters to that of WHO

reported cases which remains a challenge in unregulated

IJISRT19MA395 www.ijisrt.com 426

Volume 4, Issue 3, March – 2019 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology

ISSN No:-2456-2165

TBIC guidelines and recommend the improvements to the prevent droplet nuclei containing M. tuberculosis from

respective health care facilities. being spread in the facility, reducing exposure of staff and

patients to TB infection. However, it is not possible to

II. MATERIALS AND METHODS eliminate exposure; therefore, environmental measures are

required to reduce the concentration of droplet nuclei in the

A. Study Design and Site air. Unfortunately, even the combination of administrative

This study is a prospective multicentre study held at and environmental controls can never provide 100% safety;

20health care facilities recognized as DOTS centres from PPE is therefore needed in specific areas and during the

August 2017 to May 2018. The study sites selected were performance of specific tasks to create the desired level of

amongst the urban population of a metropolitan City safety. It is important to note that environmental and

Corporation, Bengaluru, India. A formal permission from personal respiratory controls will not work in the absence

The District Joint Director in-charge of TB activities was of solid administrative control measures. Each level

obtained. The study sites were picked in such a way that operates at a different point in enhancing quality TB care.

the centres represented from all geographical areas of the

city. Health care facilities providing any type of care for D. Assessment of Domain Compliance

people living TB with HIV, as well as those caring for The managerial assessment checklist standards from

other immunosuppressive conditions (e.g. diabetic clinics, Q1 to Q6 are self-explanatory, and evaluation of

transplant units) were prioritized, as such patients were at documentation (e.g. of an infection control plan or a

higher risk of TB disease if exposed and infected. The confidential occupational health record) was done. It was

centres were further divided into five sub sections which based on a simple interview to the facility staff responsible

include maternity care, dispensary, referral hospital, for TBIC. The administrative assessment checklist included

general hospital and health care. Under the sub-district standards from Q7 to Q16. The standards Q7 to Q11

level TB units, primary health care centres (PHC) primarily required observation in addition to asking staff

supervised centres were visited for the study. about practices. For standards Q12 to Q16 evaluation of a

random sample of records (at least 10 files were selected

B. Study Procedure and Data Collection randomly) were assessed for promptness in identification of

The overall study methodology has been depicted in presumed TB patients, TB investigation and treatment

Figure 1. The checklist was selected, and each centre was initiation, method of TB diagnosis and HIV testing. As

assessed to know the extent of compliance with four key extra pulmonary TB is seldom infectious and diagnostic

domains. The required data was obtained from programme evaluation can be lengthy, the focus of the sampling for

staffs in charge of IPC, TB and HIV in DOT centres. The standards Q13 and Q14 were on pulmonary TB. Patient

centres were analysed for the compliance with TBIC files from within the previous year and preferably within

checklist. The key four domains managerial, the previous six months (to assess recent practices) were

administrative, environmental and personal protective selected and evaluated. The environmental assessment

equipment (PPE) were primarily focused. The centres checklist focused primarily on health facilities which relied

which were non-compliant to the various standards were on natural ventilation (Q17 to Q21). The focus was based

assessed and the various reasons contributing for the non- on whether simple measures are being taken to reduce risk.

compliance were justified. These findings of the In settings where windows are closed or not present, (such

assessment were communicated to health facility staff and as health facilities in cold climates), this checklist was

other key stakeholders. After providing feedback, the modified to include an assessment of mechanical

centres were re-visited and checked. Post -interventional ventilation and ultraviolent germicidal irradiation. The PPE

assessment was done and the increases in compliance of the standards Q22 and Q23, check was done for appropriate

standards were evaluated. The non-compliant areas in particulate respirators (Certified N-95 or FFP2 [or higher])

terms of interventions were assessed and adequate were available for health-care workers, and that such

justification was provided after careful interpretation with respirators were being used where indicated.

the health care workers.

III. RESULTS

C. TBIC Checklist

Proper assessment of TBIC requires knowledge of A. Descriptive of Study Facilities

key interventions and strategies. A checklist based on the This study was primarily focussed on the healthcare

Health-Care Facilities, Congregate Settings and Household, facilities providing TB care, irrespective of speciality care

2009 WHO Policy on TB Infection Control in is structured providing such as dispensaries, maternity etc. Out of 77

around was served as standard tool. It is also aligned with active healthcare centres in the city, 20 centres were

the guidelines that address respiratory infections, 2014 enrolled into this study. The lab facilities were not

WHO’s Infection Prevention and Control (IPC). available in 5 centres among the enrolled sites, however

Managerial activities are essentially policy-level activities they had the privilege to get the samples analysed by the

and they need to be in place to facilitate the implementation nearest referral and general hospitals. These centres were

of all the other levels of TB-IC. Administrative controls subjected to assess the various standards of DOT centres as

should be prioritized in all facilities as they are more per WHO guideline checklist and with intent to provide

effective since they have the greatest impact on preventing feedback for the better-quality TB care. The distribution of

transmission of TB in health facilities. These measures these healthcare centres is presented in Table 1 along with

IJISRT19MA395 www.ijisrt.com 427

Volume 4, Issue 3, March – 2019 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology

ISSN No:-2456-2165

their geographic coordinates. The overall response rate for facilities and were completely non-complaint during pre

this study was 100%. and post intervention.

B. Study Facilities Compliance with TBIC WHO Standards IV. DISCUSSION

Checklist

The enrolled sites facilities were checked against A. Compliance of WHO Managerial Standards

TBIC WHO standard checklist. During the audit, the key Facility-level managerial activities include

four domains managerial, administrative, environmental identification and strengthening of local coordinating

and personal protective equipment (PPE) were primarily bodies and development of a facility plan (including human

focused. The data of all the domains has been represented resources) for implementation of TBIC. The plan should

in the supplemental data (Appendix 1). The managerial also include policies and procedures to ensure proper

domain consisted of six factors from Q1 to Q6 and its implementation of the administrative controls,

average compliance was 97.5%. Most of the factors were environmental controls and use of particulate respirators.

complied with the standards, out of which factors Q1, Q4, The decrease of compliance in Q3 which stated “being of

Q5 and Q6 were 100 %, Q2 was 95% and only one factor TB designated person availability at the DOT centre” was

(Q3) contributed to 85% compliance. Since most of the due to work shift to attend two centres on the alternative

factors were complaint there was no post interventional days of a week. The personnel may work in a referral

improvement in this domain. hospital or designated health centre on different days.

Rethinking the use of available spaces to optimize the

In administrative domain there were total of ten implementation of infection control measures is also

factors from Q7 to Q16 and pre-intervention average crucial. These findings indicate the need for improved

compliance was 42%. In this domain, a total of six factors isolation guidelines, better staff education and appropriate

including Q7, Q8, Q10, Q11, Q13, Q14were found to be documentation. As for Q2, one centre had no enough space

less than 50% of complaint and two factors (Q9, Q12) for establishment of the centre; the reason was not justified

being above 50% and two factors (Q15, Q16) being more aptly.

than 90% compliant to the TBIC WHO standards. The

compliance forQ7, which states “fast tracking of patients B. Compliance of WHO Administrative standards

and guidance on cough etiquette’ was 35% (n=7) and post Administrative standards play a vital role in reduction

interventional compliance was increased to 70% (n=14). of transmission of TB among the health care facilities. The

The compliance for Q8, which states “providence of health prompt identification of people with TB symptoms is of

education material” was 20% (n=4) that was increased to utmost importance depends upon the patient population in

45% (n=9)post intervention. The compliance for Q9, which the settings. The suspected patients at risk of TB to be

states “conductance of patient interviews and observation” separated from other patients and moved to well ventilated

the post interventional compliance was increased to 75% areas and adequate counselling on respiratory hygiene and

(n=15) from 55% (n=11). The compliance for Q10 which cough etiquette is of priority. Guiding the patients on

states “providence of supplies and proper garbage disposal” simple techniques, such as covering the nose or mouth with

was 15% (n=3) and post interventional compliance was bend of elbow while sneezing or coughing, which must be

increased to 50% (n=10). There were no significant cleaned immediately serves as a strong focus on behaviour

changes in the compliance from Q11 to Q16. The overall change TheQ7 factor serves as strong recommendation as

compliance improvement of the administrative standards per 2009 WHO infection control plan. The reason for non-

after intervening was increased to 11.5% and reached compliance for Q7were found to be ‘negligence’ 65%

53.5% (Table 2). (n=13),even after the post recommendation, the non-

compliance 30% was due to the continued negligence of

Five factors (Q17 to Q21) in environmental domain (Health care workers) HCWs.

were involved and pre-intervention average compliance

was 25%.In this domain, all the factors were less than 50% Adequate materials consisting of information about

compliance. Out of which Q17 and Q18 showed post the infection should be given to the patients. It helps the

interventional improvement accounting to 9% newly diagnosed patients to understand the disease better

interventional change. The compliance forQ17, which and serves as a helpful referral document. However, when

states “prompt facility design and triage system’ was 40% patients are not willing to read the education material or

(n=8) and post interventional compliance was increased to illiterates, counselling them on general aspects of the

50% (n=10). The compliance for Q18 which states “proper infection and instructing them on the medications, diet etc.,

ventilation and display of messages” was 25% (n=5) and helps them in the better understanding of the disease and

post interventional compliance was increased to 60% the stigma reduces. The outcomes, problems associated

(n=12).There were no significant changes in the with treatment and the quality of life of the patient should

compliance from Q19 to Q21. The overall compliance not only be evaluated by the periodic test results but also by

improvement of the environmental standards after conducting periodic interviews and observation of the

intervening reached 34%(Figure2). The PPE consisted of patients. The factors dealing with these aspects are Q8 and

two factors (Q22 to Q23) and no post intervention changes Q9. The non-compliance for (Q8) was found to be 80%

could be made. Alarmingly, none of the centres had these (n=16) where 45% (n=9) was due to non-availability of

education material and 35% (n=7) due to the negligence in

IJISRT19MA395 www.ijisrt.com 428

Volume 4, Issue 3, March – 2019 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology

ISSN No:-2456-2165

providing. Post-counselling compliance change was found Q13 and Q14, patients to be contacted and counselling to

to be 25% (n=5) and the non-compliance remained 55% be provided on the early sample collection and submission.

due to the frivolous attitude of the HCWs and the shortage Better co-ordination among the health care workers and the

of supplies provided. The non-compliance for Q9 was due laboratory personnel to decrease the turnover time and for

to ‘negligence’ 25% and ‘lack of communication’ 15% and rapid results. To seek management help for the deficient in

post-interventional compliance change was found to be the supply of stocks.HIV testing and periodic multidrug

20% (n=4)and the non-compliance remained to be 20% due resistant/ rifampicin resistant test in the mid of the

to non-cooperation. treatment is necessary for enhanced and prompt treatment

of the patients. The factors dealing with the above aspects

The usage of surgical masks in coughing patients are Q15 “Xpert MTB/RIF done for HIV patients with TB”

reduces transmission of droplet nuclei is of conditional and Q16 “HIV test provided for TB patients” .The

recommendation as it not clear whether they make a compliance for these factors were 90% (n=18) and the non-

significant difference and most of them feel stigmatized. compliant (10%) was due to the heavy workload of the

However, particularly in patients with serious grade of HCWs .The two centres were heavily populated with

infection and drug resistance, poor respiratory hygiene and patients and few patients were missed on including with

cough etiquette practices; usage of surgical masks serves as these above diagnostics (Table 3).

a strong recommendation according to the WHO

guidelines. Poor management of health care waste disposal C. Compliance of WHO Environmental Standards

in health care centres can cause serious contamination of Prompt identification of people with TB symptoms

the surrounding environment and harm public health along (i.e. triage, Q17) is crucial. People suspected of having TB

with serious threat of spreading infections among the must be separated from other patients must be fast-tracked.

HCW’S and patients. Hence, proper garbage disposal is of The non-compliance was found to be 60%, which after

high importance in avoiding transmission of the disease post-counselling recommendation reduced to 50%. This

and to maintain septic condition among the centres. As serves as strong recommendation. Adequate ventilation in

concerned to the compliance factor for Q10 “availability of health-care facilities is essential for preventing

the supplies and garbage disposal of waste”, the non- transmission of airborne infections and is strongly

compliance was found to be 85%. The reason for the non- recommended for controlling spread of TB. The choice of

compliance were found to be non-availability of stock ventilation system will be based on assessment of the

(50%)and being nonchalant in carrying out the facility and informed by local programmatic, climatic and

responsibility (35%).After intervening, post-counselling socioeconomic conditions. Any ventilation system (Q18)

adherence change was found to be to 35 %(n=7). must be monitored and maintained on a regular schedule.

Adequate resources (budget and staffing) for maintenance

There were some factors where there were no are critical. The mechanical ventilation and the ultra-

significant compliance changes concerned with providence germicidal ventilation are done based on the conditional

of (Q11A) HIV and (Q11B) TB prophylaxis for the health recommendations but natural ventilation being a strong

care officials. It is concerned with the managerial concern recommendation. The display of messages on cough

where the non-compliance was found to be 95%. But the etiquette (Q18) is also crucial providing guidance to the

guidelines suggest it as strong recommendation in centres patients. The noncompliance was 75%, which on post-

with high prevalence of TB and weak recommendations for counselling intervention decreased to 40% (Table 4).

centres with low HIV prevalence out of which one centres

(5%) comply with strong recommendation and failed to As concerned to the factor on providing guidance on

comply. It is important for the health care workers to sputum collection (Q20) where the compliance was only

undergo periodic testing and to take prophylactic shot when 25% due to the negligence as bottles were given to

risk is adequate, and they should be educated and respective patients to collect sample at homes (75%). The

encouraged to takes these steps. The additional isolation of the patients hospitalised (Q21) was not

administrative controls to be implemented along with the properly done in four referral and one general hospital

above standards include (Q13) rapid screening for TB involved in the study accounting for major non-

symptoms and diagnostics and (Q14) treatment initiation compliance. The non-compliance being cent percent, which

after the diagnostic not extending more than a day as per is a strong recommendation. There was no proper isolation

the guidelines. It minimizes the diagnostic delays, ensures due to administrative factors and negligence of the HCWs

rapid use of diagnostics, carrying out investigations and working with patients. A similar study [22] conducted

treatment simultaneously and reduces the turnaround time ascertains the delays involved in isolating subjects.

between screening, diagnosis and treatment.

D. Compliance of WHO Personal Protective Equipment’s

The non-compliance for Q13 was found to be 90% Use of particulate respirators was recommended for

(n=18) and Q14 was found to be 65% (n=13). No health workers when caring for patients or those suspected

significant interventional changes were made in these of having infection. HCWs should use particulate

factors. Similar studies [20,21]conducted showed the same respirators assuring less risk of TB transmission when

results indicating greatest delay in diagnosis and initiation providing care to infectious MDR-TB and XDR-TB

of treatment which again indicates insensitivity and non- patients or people suspected of having. A comprehensive

alertness of Medical officers and field staff. For factors programme for training health workers in the use of

IJISRT19MA395 www.ijisrt.com 429

Volume 4, Issue 3, March – 2019 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology

ISSN No:-2456-2165

particulate respirators should be implemented, because [4]. WorldHealth Organisation: Global Tuberculosis

correct and continuous use of respirators involves Report 2018.

significant behaviour change on the part of the health [5]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/2744

worker. It serves as a strong recommendation for centres 53/9789241565646-eng.pdf[accessed 10 October

with high MDR/XDR prevalence. Three such centres 2018]

(15%) were identified. The overall non-compliance was [6]. Regional Office for South-East Asia, World Health

found to be hundred percent. Organization. (2017). Bending the curve - ending TB:

Annual report 2017. WHO Regional Office for South-

E. Recommendations EastAsia. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10

The TBIC compliance standards of the four domains 665/254762/978929022584-eng.pdf[accessed 15

can be increased by regular auditing of the centres and November 2018].

continuous training of the healthcare workers in these [7]. Tuberculosis Indian annual report 2017, Central TB

standards. It was suggested facility level assessment of Division, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare.

TBIC standards to be incorporated into supervisory https://tbcindia.gov.in/WriteReadData/TB%20India%

activity. The regular standardized assessment serves as 202017.pdf [accessed on 10 November 2018]

tools to track the progress of the TBIC implementation. [8]. India TB report 2018: Revised National Tuberculosis

Certain areas require better flow of funds and Control Programme: annual status report

implementation by the managerial and administrative level. https://tbcindia.gov.in/showfile.php?lid=3314

It must be often revised with the growing needs of the [accessed on 20 November 2018].

patients and the centre improvements. Frequently, the [9]. Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme

findings of the assessment should be communicated with National Strategic Plan for Tuberculosis

the health care workers and other stakeholders. The Elimination.https://tbcindia.gov.in/WriteReadData/N

feedback from the auditing should be incorporated into SP%20Draft%2020.02.2017%201.pdf[accessed on 28

revision of the TBIC plan regularly to necessitate a more November 2018]

careful, better and tailored plan. [10]. Sandhu KG. Tuberculosis: Current Situation,

Challenges and Overview of its Control programs in

V. CONCLUSION India, J Glob Infect Dis. 2011; 3(2): 143–150.

DOI: 10.4103/0974-777X.81691.

TBIC is a national and sub-national managerial [11]. Chatterjee S, Poonawala H, Jain Y. Drug-resistant

framework which is crucial for the facility level TB care. tuberculosis: is India ready for the challenge? BMJ

Lack of TBIC measures will lead to the increased TB Global Health August 10, 2018;3: e000971.

transmission and impaired TB care and delayed time to doi:10.1136/ bmjgh-2018-000971

achieve “End TB Strategy”. The above recommendations [12]. UdwadiaF Z. TB epidemic looms large with Rs 2,000

should be implemented for better facility level controls in crore fund cut, erred policy. DNA, Tuberculosis in

health centres which play a basic package of interventions India;

towards the better TB quality care. The prompt BMJDOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1080 (Publish

implementation of WHO standards helps in aiding better ed 23 March 2015).

quality care of TB among the health care centres. It helps in [13]. Shringarpure KS, Isaakidis P, Sagili KD, Baxi RK,

minimizing the risks for nosocomial spread of infection Das M, et al. When Treatment is more Challenging

among the patients in the centres and improves cordial than the Disease: AQualitative Study of MDR-TB

relationship between the patients and the health care Patient Retention. Plos One 2016;11(3):

workers. Lastly, improves the standard of care provided to e0150849. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.01508

the patients along with broadening the gap between 49.

diagnosis and treatment. As clinical pharmacists, not only [14]. Dias HMY, Pai M, Raviglione MC. Ending

in the hospitals but their services are much needed in the tuberculosis in India: A political challenge & an

health care facilities aiding in the quality TB care and to opportunity. Indian J Med Res. 2018;147(3):217-220

strengthen the health care systems. [15]. Pai M, Bhaumik S, Bhuyan SS. India’s plan to

eliminate tuberculosis by 2025: converting rhetoric

REFERENCES into reality: Global Health 13March 2017;2: e000326.

doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2017- 000326.

[1]. Lange C, AbubakarI, Alffenaar JW, Bothamley G, [16]. Shewade DH, NairD, Klinton, SJ, Parmar M,

Caminero JA, Carvalho AC et al. Management of Lavanya J, MuraliL et al. Low pre-diagnosis attrition

patients with multidrug-resistant/extensively drug- but high pre-treatment attrition among patients with

resistant tuberculosis in Europe: a TBNET consensus MDR-TB: An operational research from Chennai,

statement. Eur Respir J. 2014;23-24. doi: India. Journal of Epidemiology and Global

10.1183/09031936.00188313. Health.2017-7(4)-227-233.

[2]. World Health Organisation: Global Tuberculosis 10.1016/j.jegh.2017.07.001.

Report 2017. [17]. Shewade HD, Shringarpure KS, Parmar M,Patel N,

[3]. https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/ma Kuriya S, ShihoraS, Ninama N et al. Delay and

intext_13Nov2017.pdf [accessed 25 September 2018] attrition before treatment initiation among MDR-TB

IJISRT19MA395 www.ijisrt.com 430

Volume 4, Issue 3, March – 2019 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology

ISSN No:-2456-2165

patients in five districts of Gujarat, India. Public

Health Action. 2018;8(2):59-65.

[18]. Udwadia Z, Gautam M. Multidrug-resistant-

tuberculosis treatment in the Indian private sector:

Results from a tertiary referral private hospital in

Mumbai.Lung India. 2014; 31 (4) 336-341. DOI:

10.4103/0970-2113.142101.

[19]. Bhargava A, Jain Y. The Revised National

Tuberculosis Control Programme in India: Time for

revision of treatment regimens and rapidupscaling of

DOTS-plus initiative Medicine and Society. Natl Med

J India. 2008; 21(4):187-91.

[20]. Infection prevention and control of epidemic-and

pandemic prone acute respiratory infections in health

care WHO guidelines; WHO, Publication date: April

2014.

https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/1126

56/9789241507134_eng.pdf[accessed on 10

December 2018].

[21]. 2009 WHO Policy on Infection Control of TB on

Congregate Settings, Households.; WHO publication

date 2009.

https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/4414

8/9789241598323_eng.pdf[accessed on 18 December

2018].

[22]. Sachadeva KS, Deshmukhab N, Seguyb SA, Nairb

BB, Rewariab R, Ramchandran M et al. Tuberculosis

infection control measures at health care facilities

offering HIV and tuberculosis services in India: A

baseline assess. Indian J Tuberc. 2017;65(1):87-90.

[23]. Sharma KA, Gupta N, ChandranVC.A study on

procedural delay in diagnosis and start of treatment in

drug resistant Tuberculosis under RNTC, Indian

JTuberc April 2018;30-

37.DOI: 10.1016/j.ijtb.2018.04.010.

[24]. Thiruvengadam S, Giudicatti L, MaghamiS,Farah

H,Waring J, Waterer G et al. Pulmonary

Tuberculosis: An Analysis of Isolation Practices and

Clinical Risk factors in a Tertiary Hospital, Indian

JTuberc. May 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijtb.2018.04.013.

IJISRT19MA395 www.ijisrt.com 431

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Study Assessing Viability of Installing 20kw Solar Power For The Electrical & Electronic Engineering Department Rufus Giwa Polytechnic OwoDokumen6 halamanStudy Assessing Viability of Installing 20kw Solar Power For The Electrical & Electronic Engineering Department Rufus Giwa Polytechnic OwoInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- An Industry That Capitalizes Off of Women's Insecurities?Dokumen8 halamanAn Industry That Capitalizes Off of Women's Insecurities?International Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Factors Influencing The Use of Improved Maize Seed and Participation in The Seed Demonstration Program by Smallholder Farmers in Kwali Area Council Abuja, NigeriaDokumen6 halamanFactors Influencing The Use of Improved Maize Seed and Participation in The Seed Demonstration Program by Smallholder Farmers in Kwali Area Council Abuja, NigeriaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Unmasking Phishing Threats Through Cutting-Edge Machine LearningDokumen8 halamanUnmasking Phishing Threats Through Cutting-Edge Machine LearningInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Blockchain Based Decentralized ApplicationDokumen7 halamanBlockchain Based Decentralized ApplicationInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Cyber Security Awareness and Educational Outcomes of Grade 4 LearnersDokumen33 halamanCyber Security Awareness and Educational Outcomes of Grade 4 LearnersInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Forensic Advantages and Disadvantages of Raman Spectroscopy Methods in Various Banknotes Analysis and The Observed Discordant ResultsDokumen12 halamanForensic Advantages and Disadvantages of Raman Spectroscopy Methods in Various Banknotes Analysis and The Observed Discordant ResultsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Smart Health Care SystemDokumen8 halamanSmart Health Care SystemInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Impact of Silver Nanoparticles Infused in Blood in A Stenosed Artery Under The Effect of Magnetic Field Imp. of Silver Nano. Inf. in Blood in A Sten. Art. Under The Eff. of Mag. FieldDokumen6 halamanImpact of Silver Nanoparticles Infused in Blood in A Stenosed Artery Under The Effect of Magnetic Field Imp. of Silver Nano. Inf. in Blood in A Sten. Art. Under The Eff. of Mag. FieldInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Compact and Wearable Ventilator System For Enhanced Patient CareDokumen4 halamanCompact and Wearable Ventilator System For Enhanced Patient CareInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Visual Water: An Integration of App and Web To Understand Chemical ElementsDokumen5 halamanVisual Water: An Integration of App and Web To Understand Chemical ElementsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Smart Cities: Boosting Economic Growth Through Innovation and EfficiencyDokumen19 halamanSmart Cities: Boosting Economic Growth Through Innovation and EfficiencyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Parastomal Hernia: A Case Report, Repaired by Modified Laparascopic Sugarbaker TechniqueDokumen2 halamanParastomal Hernia: A Case Report, Repaired by Modified Laparascopic Sugarbaker TechniqueInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Predict The Heart Attack Possibilities Using Machine LearningDokumen2 halamanPredict The Heart Attack Possibilities Using Machine LearningInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Keywords:-Ibadhy Chooranam, Cataract, Kann Kasam,: Siddha Medicine, Kann NoigalDokumen7 halamanKeywords:-Ibadhy Chooranam, Cataract, Kann Kasam,: Siddha Medicine, Kann NoigalInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Insights Into Nipah Virus: A Review of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Therapeutic AdvancesDokumen8 halamanInsights Into Nipah Virus: A Review of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Therapeutic AdvancesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Implications of Adnexal Invasions in Primary Extramammary Paget's Disease: A Systematic ReviewDokumen6 halamanImplications of Adnexal Invasions in Primary Extramammary Paget's Disease: A Systematic ReviewInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Parkinson's Detection Using Voice Features and Spiral DrawingsDokumen5 halamanParkinson's Detection Using Voice Features and Spiral DrawingsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- The Relationship Between Teacher Reflective Practice and Students Engagement in The Public Elementary SchoolDokumen31 halamanThe Relationship Between Teacher Reflective Practice and Students Engagement in The Public Elementary SchoolInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Air Quality Index Prediction Using Bi-LSTMDokumen8 halamanAir Quality Index Prediction Using Bi-LSTMInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Quantifying of Radioactive Elements in Soil, Water and Plant Samples Using Laser Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) TechniqueDokumen6 halamanQuantifying of Radioactive Elements in Soil, Water and Plant Samples Using Laser Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) TechniqueInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Investigating Factors Influencing Employee Absenteeism: A Case Study of Secondary Schools in MuscatDokumen16 halamanInvestigating Factors Influencing Employee Absenteeism: A Case Study of Secondary Schools in MuscatInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- An Analysis On Mental Health Issues Among IndividualsDokumen6 halamanAn Analysis On Mental Health Issues Among IndividualsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Harnessing Open Innovation For Translating Global Languages Into Indian LanuagesDokumen7 halamanHarnessing Open Innovation For Translating Global Languages Into Indian LanuagesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Diabetic Retinopathy Stage Detection Using CNN and Inception V3Dokumen9 halamanDiabetic Retinopathy Stage Detection Using CNN and Inception V3International Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Dense Wavelength Division Multiplexing (DWDM) in IT Networks: A Leap Beyond Synchronous Digital Hierarchy (SDH)Dokumen2 halamanDense Wavelength Division Multiplexing (DWDM) in IT Networks: A Leap Beyond Synchronous Digital Hierarchy (SDH)International Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Advancing Healthcare Predictions: Harnessing Machine Learning For Accurate Health Index PrognosisDokumen8 halamanAdvancing Healthcare Predictions: Harnessing Machine Learning For Accurate Health Index PrognosisInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- The Making of Object Recognition Eyeglasses For The Visually Impaired Using Image AIDokumen6 halamanThe Making of Object Recognition Eyeglasses For The Visually Impaired Using Image AIInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- The Utilization of Date Palm (Phoenix Dactylifera) Leaf Fiber As A Main Component in Making An Improvised Water FilterDokumen11 halamanThe Utilization of Date Palm (Phoenix Dactylifera) Leaf Fiber As A Main Component in Making An Improvised Water FilterInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Terracing As An Old-Style Scheme of Soil Water Preservation in Djingliya-Mandara Mountains - CameroonDokumen14 halamanTerracing As An Old-Style Scheme of Soil Water Preservation in Djingliya-Mandara Mountains - CameroonInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Internet Addiction INFODokumen3 halamanInternet Addiction INFOstuti jainBelum ada peringkat

- 1.7 Right Person, Right Place, Right Time PDFDokumen3 halaman1.7 Right Person, Right Place, Right Time PDFKaren Osorio GilardiBelum ada peringkat

- The Placebo EffectDokumen2 halamanThe Placebo EffectMeshack RutoBelum ada peringkat

- Case Presentation PBL 12 (Bipolar Disorder)Dokumen65 halamanCase Presentation PBL 12 (Bipolar Disorder)Rhomizal Mazali83% (6)

- Effects of Citicoline On Phospholipid and Glutathione Levels in Transient Cerebral IschemiaDokumen6 halamanEffects of Citicoline On Phospholipid and Glutathione Levels in Transient Cerebral IschemiaMuhammad Ilham FarizBelum ada peringkat

- Jaw Opening Exercises Head and Neck Cancer - Jun21Dokumen2 halamanJaw Opening Exercises Head and Neck Cancer - Jun21FalconBelum ada peringkat

- Medicines, 6th EdDokumen609 halamanMedicines, 6th EdNguyễn Sanh Luật50% (2)

- Contoh Brosur DiabetesDokumen2 halamanContoh Brosur DiabetesRianda FajriFahmiBelum ada peringkat

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Globalization of Health Care: - A Parkwayhealth'S PerspectiveDokumen36 halamanGlobalization of Health Care: - A Parkwayhealth'S Perspectivebrian steelBelum ada peringkat

- Respiratory Physiology: Control of The Upper Airway: Richard L. Horner University of TorontoDokumen8 halamanRespiratory Physiology: Control of The Upper Airway: Richard L. Horner University of TorontoDopamina PsicoactivaBelum ada peringkat

- Periodontal Infection Control: Current Clinical ConceptsDokumen10 halamanPeriodontal Infection Control: Current Clinical ConceptsNunoGonçalvesBelum ada peringkat

- Bioethics OutlineDokumen30 halamanBioethics OutlineJason KeithBelum ada peringkat

- Presentation 2017 ENGDokumen20 halamanPresentation 2017 ENGpabloBelum ada peringkat

- (Hari 8) Risk MatriksDokumen1 halaman(Hari 8) Risk MatrikslubangjarumBelum ada peringkat

- Opioid Induced Hyperalgesia in Patients With Chronic PainDokumen9 halamanOpioid Induced Hyperalgesia in Patients With Chronic PainAndres MahechaBelum ada peringkat

- Blanche GrubeDokumen21 halamanBlanche GrubesangroniscarlosBelum ada peringkat

- Case Study 2Dokumen6 halamanCase Study 2Gertie Mae CuicoBelum ada peringkat

- Schizo QuizDokumen4 halamanSchizo QuizmalindaBelum ada peringkat

- Medical Kit Components EandEDokumen54 halamanMedical Kit Components EandETroy Ashcraft100% (2)

- VOLUX 尖沙咀 chung parr hall 鍾伯豪醫生 PDFDokumen8 halamanVOLUX 尖沙咀 chung parr hall 鍾伯豪醫生 PDFAnonymous YT4f4ejNtH100% (1)

- NURSING CARE PLAN Impaired Transfer AbilityDokumen1 halamanNURSING CARE PLAN Impaired Transfer AbilityAce Dioso Tubasco100% (1)

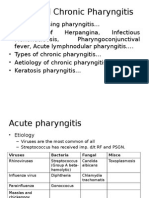

- Acute and Chronic PharyngitisDokumen10 halamanAcute and Chronic PharyngitisUjjawalShriwastavBelum ada peringkat

- Daivonex Cream PI - LPS-11-045Dokumen5 halamanDaivonex Cream PI - LPS-11-045Hesam AhmadianBelum ada peringkat

- SDJ 2020-06 Research-2Dokumen9 halamanSDJ 2020-06 Research-2Yeraldin EspañaBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical QigongDokumen5 halamanClinical QigongFlorin Iacob100% (1)

- Internal MedicineDokumen167 halamanInternal MedicineJason Steel86% (7)

- What Is BronchitisDokumen1 halamanWhat Is BronchitisMelvin Lopez SilvestreBelum ada peringkat

- Future PharmaDokumen40 halamanFuture Pharmaet43864Belum ada peringkat

- Perdev ReviewerDokumen9 halamanPerdev ReviewerPretut VillamorBelum ada peringkat

- The Health Effects of Cannabis and CannabinoidsDokumen487 halamanThe Health Effects of Cannabis and CannabinoidsMiguel Salas-GomezBelum ada peringkat

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsDari EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsBelum ada peringkat

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDari EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (42)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeDari EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BePenilaian: 2 dari 5 bintang2/5 (1)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsDari EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityDari EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (24)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedDari EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (80)