Seizures After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage A Systematic Review of Outcomes

Diunggah oleh

Joao FonsecaJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Seizures After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage A Systematic Review of Outcomes

Diunggah oleh

Joao FonsecaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Peer-Review Reports

CEREBROVASCULAR

Seizures After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Systematic Review of

Outcomes

Daniel M. S. Raper1, Robert M. Starke 2, Ricardo J. Komotar 3, Rodney Allan 4, E. Sander Connolly, Jr.5

Key words 䡲 OBJECTIVE: The risk for early and late seizures after aneurysmal subarachnoid

䡲 Aneurysm

hemorrhage (aSAH), as well as the effect of antiepileptic drug (AED) prophylaxis and

䡲 Endovascular

䡲 Intracranial the influence of treatment modality, remain unclear. We conducted a systematic

䡲 Microsurgery review of case series and randomized trials in the hope of furthering our under-

䡲 Seizure standing of the risk of seizures after aSAH and the effect of AED prophylaxis and

Abbreviations and Acronyms surgical clipping or endovascular coiling on this important adverse outcome.

ACA: Anterior cerebral artery

ACommA: Anterior communicating artery

䡲 METHODS: We performed a MEDLINE (1985–2011) search to identify random-

AED: Antiepileptic drug ized controlled trials and retrospective series of aSAH. Statistical analyses of

aSAH: Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage categorical variables such as presentation and early and late seizures were

HH: Hunt and Hess carried out using 2 and Fisher exact tests.

ISAT: International Subarachnoid Aneurysm trial

MCA: Middle cerebral artery 䡲 RESULTS: We included 25 studies involving 7002 patients. The rate of early

SAH: Subarachnoid hemorrhage

postoperative seizure was 2.3%. The rate of late postoperative seizure was 5.5%.

From the 1Royal North Shore The average time to late seizure was 7.45 months. Patients who experienced a

Hospital, Sydney, New South late seizure were more likely to have MCA aneurysms, be Hunt/Hess grade III,

Wales, Australia; 2Department of Neurological Surgery,

University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA;

and be repaired with microsurgical clipping than endovascular coiling.

3

Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Miami,

Miami, Florida, USA; 4Department of Neurosurgery, Royal

䡲 CONCLUSIONS: Despite improved microsurgical techniques and antiepileptic

Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, New South Wales, drug prophylaxis, a significant proportion of patients undergoing aneurysm

Australia; and 5Department of Neurological Surgery, clipping still experience seizures. Seizures may occur years after aneurysm

Columbia University, New York, New York, USA

repair, and careful monitoring for late complications remains important. Further-

To whom correspondence should be addressed:

Daniel M. S. Raper, M.B.B.S.

more, routine perioperative AED use does not seem to prevent seizures after SAH.

[E-mail: drap7157@uni.sydney.edu.au]

Citation: World Neurosurg. (2013) 79, 5/6:682-690.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2012.08.006 Subarachnoid Aneurysm trial (ISAT) and evidence of benefit (4). Furthermore pheny-

Journal homepage: www.WORLDNEUROSURGERY.org subsequent subgroup analyses, patients toin, which has traditionally been the most

Available online: www.sciencedirect.com treated with clipping had a significantly commonly used AED for aneurysm pa-

1878-8750/$ - see front matter © 2013 Elsevier Inc. higher risk of late seizure than those treated tients, has a variety of adverse effects and

All rights reserved. with coiling (32, 42, 49). Nevertheless, the has been correlated with poor functional

INTRODUCTION influence of treatment modality on either outcomes and cognitive status after sub-

early or late seizure outcomes has not been arachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) (33). Never-

Seizures are a well-recognized complica- assessed in a systematic review of the liter- theless, in a 2002 survey conducted by the

tion after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemor- ature. American Association of Neurological Sur-

rhage (aSAH), and have been correlated The administration of prophylactic anti- geons, 24% of neurosurgeons surveyed

with higher aneurysm grade, lower Glas- epileptic drugs (AEDs) has in the past been routinely prescribed AEDs for 3 months af-

gow Coma Scale score at presentation, ex- a standard protocol for patients undergoing ter SAH regardless of whether seizures oc-

tent of subarachnoid blood on computed many neurosurgical procedures. More re- curred at presentation, in hospital, or not at

tomography, and rebleeding (2, 18, 29, 40, cently, however, routine use of AEDs for all (3, 13, 17, 18). The use of AEDs as a

53). Early studies reported seizures in over aSAH patients has come under question primary prophylactic measure in aSAH pa-

10% of survivors of aSAH; these were more (45). Low seizure rates have been reported tients thus remains controversial.

likely in younger patients, those with mid- in series of patients with aSAH (9, 11). In In order to gain a better understanding of

dle cerebral artery (MCA) aneurysms, and reviewing these and other modern experi- the risk for early and late seizures after

those with coexisting intracerebral hemor- ences, the Stroke Council of America guide- aSAH, and to provide a quantitative supple-

rhage (11, 46). Seizures have been observed lines, published in 2009, recommended mentation to recent consensus statements

after both microsurgical clipping and endo- against routine perioperative AED use in on the topic (26), we believe it useful to

vascular coiling (9, 13). In the International ruptured aneurysms because of a paucity of survey the modern published literature. To

682 www.SCIENCEDIRECT.com WORLD NEUROSURGERY, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2012.08.006

PEER-REVIEW REPORTS

DANIEL M. S. RAPER ET AL. SEIZURES AFTER ANEURYSMAL SUBARACHNOID HEMORRHAGE

this end, we have performed a systematic tracted and divided into cohorts according zure outcomes, as well as seizure outcomes

CEREBROVASCULAR

review of the available published reports of to aneurysm location and treatment strat- between cohorts that received AED prophy-

outcomes following aneurysm repair after egy. Data for all patients were recorded laxis vs. those that received no AED prophy-

SAH in order to gain a more comprehensive when available, including mean age, sex, laxis, and between cohorts of aneurysms

assessment of the risk of seizure and the aneurysm location, presentation seizure, that were clipped vs. those that were coiled.

influence of AED prophylaxis and treatment and SAH grade. Presentation seizures were A total of 25 studies reported seizure out-

modality. defined as those occurring before the first comes after aSAH. Fourteen studies re-

intervention for SAH. Early seizures were ported outcomes among cohorts of aSAH

defined as those that occurred after inter- patients who received AED prophylaxis (3,

vention during the initial hospital stay. Late 10, 12, 13, 16, 19, 22, 23, 27, 34, 41, 44, 50,

MATERIALS AND METHODS seizures were defined as those that occurred 53), 3 studies reported outcomes in those

after discharge from hospital. Because the who did not receive AED prophylaxis (6, 7,

Study Selection

series in this review included randomized 39), and 3 studies compared cohorts treated

We performed a modern literature search

trials as well as prospective and retrospec- with AED or no AED prophylaxis (28, 38,

using the Ovid gateway of the MEDLINE

tive case series, an assessment of bias was 43). Fifteen studies reported outcomes

database between the years 1985 and 2010.

made only on the outcome level rather than among cohorts of aSAH patients who were

The following key words were queried sin-

at the individual study level. The interpreta- clipped (3, 6, 7, 10, 16, 19, 22, 23, 27, 30, 34,

gly and/or in combination: seizure, sub-

tion of these results is limited by this un- 39, 40, 53), 1 study reported outcomes in

arachnoid, hemorrhage, epilepsy, aneu-

quantified level of bias, and makes our those who were coiled (9), and 3 studies

rysm, antiepileptic, anticonvulsant, outcome,

systematic review a synthesis of level 3 evi- compared cohorts who were clipped and

surgery. The search was limited to studies

dence only. coiled, reporting seizure outcomes (28, 32,

published in English, and humans were

43). A total of 25 studies and 7002 patients

specified as the study category. No spe-

were included in this review.

cific review protocol was used for this sys-

Statistical Analysis and Systematic Characteristics and primary findings of

tematic review.

Analysis the 25 included studies of seizures in pa-

Eligibility criteria were limited by the na-

Data from the individual studies were com- tients with aneurysmal SAH are summa-

ture of existing literature on this topic,

bined by cohort and then compared. Statis- rized in Table 1. Regarding study design, 21

which consists largely of retrospective case

tical analyses of categorical variables were articles were retrospective (3, 7, 9, 10, 12, 16,

series. To gain a more accurate reflection

carried out using 2 and Fisher exact tests as 19, 22, 23, 27, 28, 34, 38-41, 43, 44, 50, 51,

of seizure incidence using modern micro-

appropriate. Because there were significant 53), 3 were prospective (13, 16, 30), and

surgical and endovascular techniques, only

differences between cohorts, analysis of there was 1 randomized controlled trial

reports published after 1985 were included

heterogeneity was not carried out. Values of (32).

in this review. All publications reporting

seizure outcomes after surgery or endovas- P ⱕ .05 were considered statistically signif-

cular intervention for ruptured intracranial icant.

Patient Characteristics

aneurysms were selected, whereas editori- Patient characteristics of the whole cohort,

als, commentaries, and review articles were as well as cohorts of clipped vs. coiled and

not, because they did not include original AED prophylaxis vs. no AED prophylaxis,

RESULTS

data. Series that included patients with un- are reported in Table 2. In total there were

ruptured aneurysms or patients with a past Study Selection and Study 7002 patients, mean age 51.3, mean fol-

history of epilepsy were also excluded from Characteristics low-up 46.6 months, 37.5% male. Aneu-

this analysis. To avoid duplication of pa- A total of 87 published studies since 1985 rysms were located most commonly in the

tients, in cases in which multiple articles were identified through our initial MED- anterior communicating artery (ACommA)

were published from the same authors or LINE database search. After removal of du- and MCA, and were evenly split between

the same institution, only the report with plicates, all records were screened by review Hunt and Hess (HH) grades I, II, and III. In

the largest relevant cohort was included. A of abstracts for suitability. The full text of all the clipped cohort there were 4378 patients,

manual search for manuscripts was also records with reference to aneurysm and sei- mean age 49.5, mean follow-up 50.9

conducted by scrutinizing references from zure was downloaded and filtered for men- months, 40.5% male. Aneurysms were lo-

identified manuscripts, major neurosurgi- tion of seizure outcomes using a combina- cated in the anterior circulation in 93.2%,

cal journals and texts, and personal files. tion of search terms (epilep*, seiz*, most commonly HH grade II. In the coiled

The date of the last search was March 2011. convul*, etc.) Applicable records were thor- cohort there were 1418 patients, mean age

oughly reviewed for final inclusion or exclu- 52.2, mean follow-up 43.0 months, 36.6%

sion. Altogether, 62 records were rejected male. Aneurysms were located in the ante-

Data Extraction from our review because they did not in- rior circulation in 71.1%; the HH grade was

Included studies were reviewed and care- clude original data, did not report seizure not reported in any reports of coiled aneu-

fully scrutinized for study design, method- outcomes, or did not differentiate between rysms. The 2 cohorts did not differ signifi-

ology, and patient characteristics. The total ruptured and unruptured aneurysms. Stud- cantly in any patient or aneurysm character-

number of patients for each study was ex- ies were analyzed with respect to overall sei- istics. In the AED cohort there were 3232

WORLD NEUROSURGERY 79 [5/6]: 682-690, MAY/JUNE 2013 www.WORLDNEUROSURGERY.org 683

PEER-REVIEW REPORTS

DANIEL M. S. RAPER ET AL. SEIZURES AFTER ANEURYSMAL SUBARACHNOID HEMORRHAGE

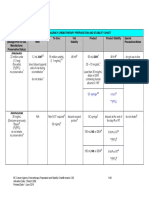

Table 1. Study Characteristics of Seizures After Aneurysmal SAH

CEREBROVASCULAR

Mean Hunt and Hess Grade

Study Patient Age AED Follow- Presentation Early Late

Author and Year Design Number Approach Male (years) I II III IV V Use Up Seizure Seizure Seizure

Ise et al., 1985 (22) Retro 192 Open 82 51.1 62 62 55 13 0 192 32.9 13 — 18

Keranen et al., 1985 (23) Retro 177 Open 82 43.8 81 54 42 177 — — — 25

Sundaram and Chow, Retro 104 — — — — — — — — — — 19 7 5

1986 (51)

Fabinyi and Artiola- Retro 265 Open — — — — — — — 199 — 0 4 5

Fortuny, 1980 (16)

Ohman, 1990 (39) Retro 307 Open — 45.2 77 109 56 25 11 0 — — — 29

Ukkola and Heikkinen, Retro 183 Open — — — — — — — — 43.2 — 1 13

1990 (53)

Bidzinski et al., 1992 (6) Pros 118 Open — — — — — — — 0 21 — — 8

Baker et al., 1995 (3) Retro 200 Open — — 70 46 60 21 3 200 28.8 — 3 6

Pinto et al., 1996 (41) Retro 253 — — — — — — — — 61 — 16 — 1

Ogden et al., 1997 (38) Retro 123 — 42 48.8 — — — — — 52 — 2 9 13

Hayashi et al., 1999 (19) Retro 116 Open — — 11 57 24 21 3 116 — — 4 4

Olafsson et al., 2000 (40) Retro 44 Open — — — — — — — — 277.2 10 — 11

Rhoney et al., 2000 (44) Retro 94 Open 29 47.9 — — — — — 94 — 17 5 8

Naso et al., 2001 (34) Retro 53 Open — — 42 11 53 — — 1 0

Buczacki et al., 2004 (7) Retro 472 Open 157 53 — — — — — 0 — — — 23

Byrne et al., 2003 (9) Retro 243 Endo 90 50.9 — — — — — — 21.1 26 — 4

Claassen et al., 2003 (13) Pros 219 — — — — — — — — 219 — — 8 27

Lin et al., 2003 (27) Retro 217 Open 85 49.3 — — — — — 217 78.7 22 4 21

Mitchell et al., 2005 (30) Pros 5 Open — — — — — — — — — — — 1

Molyneux et al., RCT 2143 O/E — — — — — — — — 48 14 49 109

2005 (32)

Chumnanvej et al., Retro 453 — 141 54.3 153 134 92 71 453 — — 8 15

2007 (12)

Lin et al., 2008 (28) Retro 137 O/E 44 55.8 — — — — — — — 5 8 1

Choi et al., 2009 (10) Retro 547 Open 228 — 128 96 4 547 — 51 6 30

Shah and Husain, Retro 176 — 63 58.2 111 51 14 176 — 5 0 0

2009 (50)

Raper et al., 2011 (43) Retro 161 O/E 59 54.6 — — — — — 92 — 27 4 9

SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; AED, antiepileptic drug; Retro, retrospective: Pros, prospective; RCT, randomized controlled trial; O/E, open and endoscopic.

patients, mean age 51.7, mean follow-up higher incidence of anterior communicat- ing artery, ACA, MCA, and posterior cere-

46.8 months, 39.2% male. Aneurysms were ing artery, MCA, and posterior communi- bral artery aneurysms, and a lower inci-

located in the anterior circulation in 90.9%, cating artery aneurysms and a lower inci- dence of posterior communicating, basilar

most commonly HH grade III. In the no dence of anterior cerebral artery (ACA), apex, and other posterior circulation aneu-

AED cohort there were 1165 patients, mean internal carotid artery, and posterior cere- rysms.

age 51.2, mean follow-up 21 months, 33.3% bral artery aneurysms. This group likewise

male. Aneurysms were located in the ante- had lower incidence of HH grades III to V,

rior circulation in 96.1%, most commonly but a higher incidence of grade II aneu- Antiepileptic Drug Characteristics

HH grade I. rysms. Between the clipped and coiled Overall, AED prophylaxis was used in 3244

There were a number of significant dif- groups, there were also a number of signif- of 4463 reported cases (72.7%). The aver-

ferences between the AED and no AED co- icant differences. The clipped cohort had a age time of AED use was 8.2 months (range:

horts. Those not receiving AEDs had a higher incidence of anterior communicat- 5 days to 25.8 months). Among the cohort

684 www.SCIENCEDIRECT.com WORLD NEUROSURGERY, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2012.08.006

PEER-REVIEW REPORTS

DANIEL M. S. RAPER ET AL. SEIZURES AFTER ANEURYSMAL SUBARACHNOID HEMORRHAGE

Table 2. Patient and Aneurysm Characteristics in Aneurysmal SAH Studies

CEREBROVASCULAR

AED Prophylaxis Treatment Modality

All Patients AED No AED P Value Clip Coil P Value

Patient characteristics

Total patients 7002 3232 1165 4378 1418

Mean age 51.3 51.7 51.2 49.5 52.2

Male (%) 1122/2992 (37.5) 766/1953 (39.2) 224/673 (33.3) .77 695/1714 (40.5) 108/295 (36.6) .08

Aneurysm location (%)

ACommA 879/2860 (30.7) 430/1452 (29.6) 290/811 (35.8) .002 620/1966 (31.5) 72/294 (24.5) .02

ACA 157/2860 (5.5) 109/1452 (7.5) 22/811 (2.7) ⬍.001 131/1966 (6.7) 11/294 (3.7) .05

MCA 663/2860 (23.2) 341/1452 (23.5) 219/811 (27.0) .006 512/1966 (26.0) 41/294 (13.9) ⬍.001

ICA 394/2860 (13.8) 246/1452 (16.9) 100/811 (12.3) ⬍.001 304/1966 (15.5) 19/294 (6.5) ⬍.001

PCommA 393/2860 (13.7) 156/1452 (10.7) 132/811 (16.3) ⬍.001 223/1966 (11.3) 55/294 (18.7) ⬍.001

Other anterior 76/2860 (2.7) 38/1452 (2.6) 16/811 (2.0) .22 42/1966 (2.1) 11/294 (3.7) .09

Basilar apex 142/2860 (5.0) 55/1452 (3.8) 23/811 (2.8) .21 52/1966 (2.6) 60/294 (20.4) ⬍.001

PCA 65/2860 (2.3) 53/1452 (3.7) 1/811 (0.1) ⬍.001 54/1966 (2.7) 2/294 (0.7) .04

Other posterior 91/2860 (3.2) 24/1452 (1.7) 8/811 (1.0) .18 28/1966 (1.4) 23/294 (7.8) ⬍.001

Hunt and Hess grade (%)

Grade I 301/1287 (23.4) 224/1009 (22.2) 77/278 (27.7) .06 239/809 (29.5) —

Grade II 328/1287 (25.5) 219/1009 (21.7) 109/278 (39.2) ⬍.001 274/809 (33.9) —

Grade III 329/1287 (25.6) 273/1009 (27.1) 56/278 (20.1) .02 195/809 (24.1) —

Grade IV 223/1287 (17.3) 198/1009 (19.6) 25/278 (9.0) ⬍.001 80/809 (9.9) —

Grade V 106/1287 (8.2) 95/1009 (9.4) 11/278 (4.0) .004 21/809 (2.6) —

Mean follow-up (months) 46.6 46.8 21.0 50.9 43.0

SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; AED, antiepileptic drug; ACommA, anterior communicating artery; ACA, anterior cerebral artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; ICA, internal carotid artery;

PCommA, posterior communicating artery; PCA, posterior cerebral artery.

of patients analyzable for the AED prophy- coiled and AED prophylaxis vs. no AED pro- For the whole cohort, late (after discharge)

laxis cohort, AEDs were used in all 3232 phylaxis, are reported in Tables 3– 6. seizures occurred in 386 patients (5.5%). The

cases, for a mean 4.1 months. The most mean time to seizures was 7.45 months. In

commonly used anticonvulsants were phe- Seizures. For the whole cohort, early (in- the AED cohort, late seizures were reported in

nytoin (82.6% of reported cases) and val- hospital) seizures occurred in 121 patients 17 studies and occurred in 5.9% of patients

proic acid (16.9% of reported cases). Ad- (2.3%). In the AED cohort, early seizures (190 of 3232) at a mean time to seizure of 5.6

verse events due to AED use were reported were reported in 14 studies and occurred in months. In the no AED cohort, late seizures

in only 7 articles, and occurred in 21.4% of 2.2% of patients (57 of 2610). In the no AED were reported in 6 studies and occurred in

cases (219 of 1025). The most common ad- cohort, early seizures were reported in 3 6.3% of patients (73 of 1165) at a mean time of

verse reactions were deranged liver func- studies and occurred in 3.0% of patients (8 6.5 months. In the clipped cohort, late sei-

tion test (69 of 268 cases, 25.7%), thrombo- of 268). In the clipped cohort, early seizures zures were reported in 10 studies and oc-

cytopenia (21 of 268 cases, 7.8%), and rash were reported in 10 studies and occurred in curred in 6.5% of patients (278 of 4281) at a

(5 of 362 cases, 7.8%). Stevens-Johnson 2.4% of patients (67 of 2781). In the coiled mean time of 5.9 months. In the coiled co-

syndrome has been reported in 5 of 754 cohort, early seizures were reported in 3 hort, late seizures were reported in 4 studies

cases (0.7%). Switching or discontinuation studies and occurred in 1.4% of patients (17 and occurred in 3.3% of patients (47 of 1418).

of AED was required in 112 of 815 reported of 1175). There was no significant differ- There was no significant difference in the

cases (13.7%).

ence in the incidence of early seizure in the rates of late seizure between the AED and no

AED compared with the no AED cohort AED cohorts (5.9% vs. 6.3%, P ⬎ .99).

Outcomes and Complications (3.0% vs. 2.2%, P ⬎ .99), or between the There was a higher rate of late seizure in the

Outcomes and complications of the whole clipped compared with the coiled cohort clipped cohort compared with the coiled

cohort, as well as cohorts of clipped vs. (2.4% vs. 1.4%, P ⫽ .16) (Figure 1). cohort (6.5% vs. 3.3%, P ⬍ .003) (Figure 2).

WORLD NEUROSURGERY 79 [5/6]: 682-690, MAY/JUNE 2013 www.WORLDNEUROSURGERY.org 685

PEER-REVIEW REPORTS

DANIEL M. S. RAPER ET AL. SEIZURES AFTER ANEURYSMAL SUBARACHNOID HEMORRHAGE

Table 3. Seizure Outcomes in AED and No AED Patients in Aneurysmal SAH Studies

CEREBROVASCULAR

Total Cohort AED Cohort No AED Cohort

Number Occurrence/ P Value Number Occurrence/ P Value Number Occurrence/ P Value

of Total (All vs. of Total (AED vs. of Total (No AED

Studies Patients % AED) Studies Patients % No AED) Studies Patients % vs. All)

Presentation 14 277/4699 4.8 ⬍.003 10 158/1831 8.6 ⬍.003 3 0/268 0 ⬍.003

seizure

AED use 20 3244/4463 72.7 ⬍.003 17 3232/3232 100 ⬍.003 6 0/1165 0 ⬍.003

Time of AED 8.2 4.1 NA

exposure (months)

Early seizure 16 121/5191 2.3 ⬎.99 14 57/2610 2.2 ⬎.99 3 8/268 3.0 ⬎.99

Late seizure 25 386/7002 5.5 ⬎.99 17 190/3232 5.9 ⬎.99 6 73/1165 6.3 .82

Time to late 7.45 5.6 6.5

seizure (months)

AED, antiepileptic drug; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; NA, not available.

Characteristics of Patients Who Experienced I. In the no AED group, 41.7% of patients coiled, AED prophylaxis, and no AED pro-

Seizures. Among patients who experienced had MCA aneurysms, whereas 29.8% had phylaxis groups.

seizures, aneurysms were located in the an- ACommA aneurysms; 34.5% of patients

terior communicating artery in 29.3%, were HH grade III, with 27.6% being grade

ACA in 6.5%, MCA in 39.0%, internal ca- II. In the clipped group, among patients

rotid artery in 13.8%, posterior communi- who experienced postprocedural seizures DISCUSSION

cating artery in 8.9%, and basilar apex in 47.9% of patients had MCA aneurysms, SAH has been associated with late seizures

2.4% of cases. Patients who experienced whereas 21.1% had ACommA aneurysms; both in studies of the condition’s natural

postoperative seizures had SAH grade I 48.4% of patients were HH grade III, and history and in series of treated patients

in 25.0%, grade II in 18.3%, grade III in 32.3% were grade I. In the coiled group, the (9, 30, 32). Population-based data from pa-

41.7%, grade IV in 11.7%, and grade V in location and SAH grade among patients tients treated in the 1950s and 1960s esti-

3.3%. In the AED group, 33.3% of pa- who experienced seizures was not reported. mated the 1- and 5-year incidence of epi-

tients with seizures had anterior commu- There were no significant differences in lepsy after SAH at 18% and 25%,

nicating artery aneurysms and 28.6% had the location or grade of aneurysms among respectively (40). In a Swedish review of ep-

MCA aneurysms; 48.4% of patients were patients experiencing postprocedural sei- ilepsy registry data, Adelow et al. found that

HH grade III, whereas 32.3% were grade zures after aSAH between the clipped, hospitalization for subarachnoid hemor-

Table 4. Seizure Outcomes in Clipped and Coiled Patients in Aneurysmal SAH Studies

Total Cohort Clipped Cohort Coiled Cohort

Number Occurrence/ P Value Number Occurrence/ P Value Number Occurrence/ P Value

of Total (All vs. of Total (Clip vs. of Total (Coil vs.

Studies Patients % Clip) Studies Patients % Coil) Studies Patients % All)

Presentation 14 277/4699 4.8 ⬎.99 9 140/2681 5.2 ⬍.003 4 39/1418 2.8 .003

seizure

AED use 20 3244/4463 72.7 .02 13 2020/2892 69.8 .006 1 26/52 50 ⬍.003

Time of AED 8.2 9.7 NR

exposure (months)

Early seizure 16 121/5191 2.3 ⬎.99 10 67/2781 2.4 .14 3 17/1175 1.4 .16

Late seizure 25 386/7002 5.5 .08 18 278/4281 6.5 ⬍.003 4 47/1418 3.3 ⬍.003

Time to late 7.45 5.9 NR

seizure (months)

SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; AED, antiepileptic drug; NR, not reported.

686 www.SCIENCEDIRECT.com WORLD NEUROSURGERY, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2012.08.006

PEER-REVIEW REPORTS

DANIEL M. S. RAPER ET AL. SEIZURES AFTER ANEURYSMAL SUBARACHNOID HEMORRHAGE

Table 5. Patient and Aneurysm Characteristics of Those Who Experienced Seizures with or without AED Prophylaxis

CEREBROVASCULAR

Total Cohort AED Cohort No AED Cohort

Number Occurrence/ P Value Number Occurrence/ P Value Number Occurrence/ P Value

of Total (All vs. of Total (AED vs. of Total (No AED

Studies Patients % AED) Studies Patients % No AED) Studies Patients % vs. All)

Aneurysm location

ACommA 8 36/123 29.3 ⬎.99 5 21/63 33.3 ⬎.99 5 25/84 29.8 ⬎.99

ACA 8 8/123 6.5 ⬎.99 5 5/63 7.9 ⬎.99 5 4/84 4.8 ⬎.99

MCA 8 48/123 39.0 .48 5 18/63 28.6 .31 5 35/84 41.7 ⬎.99

ICA 8 17/123 13.8 ⬎.99 5 10/63 15.9 ⬎.99 5 11/84 13.1 ⬎.99

PCommA 8 11/123 8.9 ⬎.99 5 7/63 11.1 ⬎.99 5 7/84 8.3 ⬎.99

Basilar apex 8 3/123 2.4 ⬎.99 5 2/63 3.2 ⬎.99 5 2/84 2.4 ⬎.99

SAH grade (Hunt and Hess)

Grade I 5 15/60 25.0 ⬎.99 4 10/31 32.3 .53 1 5/29 17.2 ⬎.99

Grade II 5 11/60 18.3 .84 4 3/31 9.7 .22 1 8/29 27.6 .95

Grade III 5 25/60 41.7 ⬎.99 4 15/31 48.4 .83 1 10/29 34.5 ⬎.99

Grade IV 5 7/60 11.7 ⬎.99 4 3/31 9.7 ⬎.99 1 4/29 13.8 ⬎.99

Grade V 5 2/60 3.3 .92 4 0/31 0 .41 1 2/29 6.9 ⬎.99

Intervention

Surgical clipping 12 283/347 81.6 9 151/154 98.1 5 67/70 95.7

Endovascular coiling 6 64/347 18.4 4 3/154 1.9 3 3/70 4.3

AED, antiepileptic drug; ACommA, anterior communicating artery; ACA, anterior cerebral artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; ICA, internal carotid artery; PCommA, posterior communicating

artery; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage.

rhage was associated with an odds ratio of patients at a mean latency of 8.4 months genders a lower risk of developing seizures

5.1 (95% confidence interval: 1.1 to 23.0) for (24). In our systematic analysis, late sei- and epilepsy over the long term. Further-

subsequent unprovoked seizure (1). Sei- zures occurred at a mean of 7.45 months more, the efficacy of prophylactic AEDs in

zures have been associated with younger from the time of initial hospitalization. Pa- the prevention of early and late seizures re-

age, MCA aneurysms, intracranial hemor- tients may continue to experience the onset mains unquantified, and recent reviews

rhage, and higher grade of SAH at presen- of seizures many years after the initial hos- have reiterated the need for level 1 evidence

tation (7, 10, 25, 27-29, 38, 39, 44, 46). Sub- pitalization (43), however, which may most on the topic (26, 45).

dural hematoma, cerebral infarction, commonly reflect rebleeding (46, 48). Late

vasospasm, and hydrocephalus at presenta- seizures may also be related to gliosis, or to

tion have been associated with risk of late the development of meningocerebral cica- The Effect of Clipping vs. Coiling on

seizure in a prospective analysis (13, 18). trix (17). Seizures

Seizure at presentation has not been found A recent survey of the Nationwide Inpa- Late seizure rates of up to 26% have been re-

to correlate with late seizures after aneu- tient Sample database identified a 10% to ported after aneurysmal SAH in patients treated

rysm repair in most studies (9, 18, 28, 54), 11% incidence of seizures or epilepsy after with surgical clipping (19). In coiled patients,

and these ictal events may be related to ab- clipping or coiling of ruptured intracranial few studies have evaluated the late seizure risk,

normal posturing (15), herniation, or raised aneurysms (21). In the overall literature, a butithasgenerallybeenfoundtobelower,inthe

intracranial pressure rather than true sei- number of studies utilizing different meth- range of 1.7% to 2.5% (9, 32). More recent stud-

zures (14, 17). odologies and patient populations have re- ies of both treatment modalities report rates to-

Previous work has suggested that most ported low seizure outcomes after aSAH (6, ward the lower end of this range, and modern

seizures occur within the first year after re- 7, 9, 16, 44). The publication of the ISAT neurosurgical strategies such as early surgery,

pair of ruptured intracranial aneurysms. In trial has resulted in significant shifts in endovascular coiling, and dedicated neurologi-

one prospective cohort, 11% of patients practice to incorporate greater numbers of cal critical care units may have contributed to

with SAH had at least 1 seizure within 12 coiled patients because of the potential this observed decrease (47). Notably, studies re-

months, with 7% experiencing 2 or more morbidity and mortality benefits associated porting low rates of seizure after coil emboliza-

seizures (13). In an older retrospective se- with a minimally invasive procedure (2, 32). tion have had short follow-up—12 months in

ries, late seizures were reported in 14% of Yet it is not clear whether coiling also en- the article by Claassen et al. (13), 12 months fol-

WORLD NEUROSURGERY 79 [5/6]: 682-690, MAY/JUNE 2013 www.WORLDNEUROSURGERY.org 687

PEER-REVIEW REPORTS

DANIEL M. S. RAPER ET AL. SEIZURES AFTER ANEURYSMAL SUBARACHNOID HEMORRHAGE

Table 6. Patient and Aneurysm Characteristics of Those Who Experienced Seizures After Clipping or Coiling

CEREBROVASCULAR

Total Cohort Clipped Cohort Coiled Cohort

Number of Occurrence/ P Value (All Number of Occurrence/ Number of Occurrence/

Studies Total Patients % vs. Clip) Studies Total Patients % Studies Total Patients %

Aneurysm location

ACommA 8 36/123 29.3 .21 5 15/71 21.1 NR

ACA 8 8/123 6.5 .39 5 7/71 9.9 NR

MCA 8 48/123 39.0 .22 5 34/71 47.9 NR

ICA 8 17/123 13.8 .83 5 9/71 12.7 NR

PCommA 8 11/123 8.9 .41 5 4/71 5.6 NR

Basilar apex 8 3/123 2.4 .87 5 2/71 2.8 NR

SAH grade (Hunt and Hess)

Grade I 5 15/60 25.0 .38 5 15/60 32.3 NR

Grade II 5 11/60 18.3 .28 5 3/31 9.7 NR

Grade III 5 25/60 41.7 .54 5 15/31 48.4 NR

Grade IV 5 7/60 11.7 .77 5 3/31 9.7 NR

Grade V 5 2/60 3.3 .31 5 0/31 0 NR

ACommA, anterior communicating artery; ACA, anterior cerebral artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; ICA, internal carotid artery; PCommA, posterior communicating artery; SAH, subarachnoid

hemorrhage; NR, not reported.

low-upforthecompletecohortinISAT(32),and group (relative risk 0.52) (32). In a more recent atedwithahigherrateofepilepsy,thedifference

22 months in the Byrne et al. series of coiled analysis of the ISAT trial data, Scott et al. (49) was not significant. These results are similar to

patients(9).Recentsurgicalseriesreportseizure described neuropsychological outcomes our own experience (43). However, in aggrega-

rates as low as 3% (11). It may be the case that, as among ISAT patients from the UK. There was tion of the available published data, the inci-

for other differences in outcomes between no correlation between seizure at presentation dence of late (3.3% vs. 6.5%, P ⬍ .003) seizure

clipped and coiled cohorts, as patients are fol- and cognitive impairment at 1 year, but there among coiled patients seems to be significantly

lowed up for longer periods of time postinter- was a higher incidence of late seizures in the lower than among clipped patients. There was a

vention for SAH, the significant differences be- neurosurgical group than in the endovascular lower incidence of early seizures among the

tween treatment modalities observed at 6 to 12 group both for patients with cognitive impair- coiledcohort(1.4%vs.2.4%),althoughthiswas

months diminish in size (31, 42). ment (12 vs. 3) and without cognitive impair- not significant. Some of the difference in late

Onlyalimitednumberofstudieshavedirectly ment (6 vs. 4). Claassen et al. (13) prospectively seizures may be caused by surgical factors that

compared clipping and coiling to evaluate late evaluated the rate of postoperative epilepsy in may contribute to a subsequent pro-seizure

seizurerisk.IntheISATtrial,endovasculartreat- 247 patients with SAH to define predictors and state, including rebleeding, hyponatremia, de-

ment was associated with a significantly lower clinical impact of postoperative epilepsy, find- layed ischemic insult, or hydrocephalus (9, 36).

risk of seizure compared with the neurosurgery ing that although surgical clipping was associ-

The Effect of AED Prophylaxis on

Seizures

Anticonvulsant drugs have been used to prevent

the incidence of postoperative seizures in aSAH

patients, but no clear consensus has been

reached regarding timing or efficacy of prophy-

lactic AEDs. AEDs have shown efficacy in pre-

venting seizures in traditional series of patients

undergoing craniotomy (14, 37). Most patients

who experienced late seizures in early studies

were not on AED prophylaxis at the time of their

seizure(46),implyingthatlong-termAEDsmay

Figure 1. Incidence of early seizure among Figure 2. Incidence of late seizure among have some beneficial effect. Two series have

patients treated for aneurysmal subarachnoid patients treated for aneurysmal subarachnoid demonstrated that restricting the timing of ad-

hemorrhage, by cohort. hemorrhage, by cohort.

ministration of prophylactic AEDs to the imme-

688 www.SCIENCEDIRECT.com WORLD NEUROSURGERY, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2012.08.006

PEER-REVIEW REPORTS

DANIEL M. S. RAPER ET AL. SEIZURES AFTER ANEURYSMAL SUBARACHNOID HEMORRHAGE

diate perioperative period does not increase the with a high risk of seizure, such as those with

REFERENCES

CEREBROVASCULAR

incidence of postoperative seizures (3, 12). For a significantcorticalinjury,focalpathology,hem-

population or subpopulation with a postopera- orrhage,orextensivesurgicalmanipulation(20, 1. Adelow C, Andersson T, Ahlbom A, Tomson T: Prior

tive seizure rate of 10% to 15%, AED prophylaxis 35). However, there is no direct evidence to sup- hospitalization for stroke, diabetes, myocardial in-

farction, and subsequent risk of unprovoked sei-

has been suggested as appropriate (14, 20). port this hypothesis. Despite the apparent in- zures. Epilepsia 52:301-307, 2011.

However, in the modern literature there is lit- creased safety of newer antiepileptic agents,

tle evidence that AED prophylaxis is effective. A even these drugs are associated with certain 2. Andaluz N,ZuccarelloM:Recenttrendsinthetreatment

number of retrospective series have demon- morbidities such as fever, anemia, or cardiac ar- of cerebral aneurysms: analysis of a nationwide inpatient

database. J Neurosurg 108:1163-1169, 2008.

strated no significant difference between rhythmias (52). It will be important for these

groups with or without prophylaxis in terms of newer AEDs to demonstrate efficacy in the pre- 3. Baker CJ, Prestigiacomo CJ, Solomon RA: Short-term

seizureoutcome(6,13,16,28,38).Inananalysis vention of seizures in the highest-risk patient perioperative anticonvulsant prophylaxis for the surgical

of 4 large drug trials, Rosengart et al. (47) found population to justify their use as prophylaxis. treatment of low-risk patients with intracranial aneu-

rysms. Neurosurgery 37:863-871, 1995.

that patients who received AEDs had an odds

ratio of 1.56 for worse outcome at 3 months, as Study limitations 4. Bederson JB, Connolly EJ, Jr., Batjer HH, Dacey RG,

well as increased risk for vasospasm, neurolog- The interpretation of our results is limited, in

Dion JE, Diringer MN, Duldner JE, Jr., Harbaugh

ical deterioration, cerebral infarction, and ele- RE, Patel AB, Rosenwasser RH: American Heart As-

part, by study heterogeneity, because investiga- sociation: Guidelines for the management of aneu-

vated temperature during hospitalization. AED tions from multiple centers presented varying rysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: a statement for

use in this study was, however, associated with study designs, methodologies, management healthcare professionals from a special writing

younger age, worse neurological grade, and group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Asso-

paradigms,adjuvanttherapies,andpatientpop- ciation. Stroke 40:994-1025, 2009.

lower systolic blood pressure at admission, ulations. A large proportion of the literature

which likely contributed to the observed out- evaluating surgical outcomes is subject to publi- 5. Bleck TP, Chang CWJ: Ten things we hate about

comes in the AED cohort. cation bias because it comprises single-center subarachnoid hemorrhage (or, the taming of the

The adverse effects of AEDs have not been aneurysm). Crit Care Med 34:571-574, 2006.

experience (56).There was a significantly higher

well characterized in aSAH patients, but have incidence of presentation seizure among pa- 6. Bidzinski J, Marchel A, Sherif A: Risk of epilepsy

likely been underestimated. Phenytoin has been tients in the AED and in the clipped groups, after aneurysm operations. Acta Neurochir (Wien)

associated with drug-induced fever and vaso- whichmayberelatedtoanincreasedriskofpoor 119:49-52, 1992.

spasm after aSAH (5), and adverse effects have outcome, rebleeding, and late seizure (8, 7. Buczacki SJ, Kirkpatrick PJ, Seeley HM, Hutchinson

been reported in up to 35% of treated patients 40).The lack of a standardized protocol for the PJ: Late epilepsy following open surgery for aneu-

(10, 22). In our review, among those receiving use of AEDs raises the possibility of selection rysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurol Neuro-

AED prophylaxis, adverse effects due to medica- surg Psychiatry 75:1620-1622, 2004.

bias. Indeed, use of AEDs varies by individual

tion were experienced in 21.4% of patients, re- neurosurgeons even within studies. Patients 8. Butzkueven H, Evans AH, Pitman A, Leopold C, Jolley

quiring switching in 13.7%, and included de- deemed to be most at risk of developing seizure DJ, Kaye AH, Kilpatrick CJ, Davis SM: Onset seizures in-

ranged liver function test, thrombocytopenia, may thus have preferentially been administered dependently predict poor outcome after subarachnoid

rash, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. In a pro- prophylactic AEDs. Considering these limita- hemorrhage. Neurology 55:1315-1320, 2000.

spective study of 527 patients with SAH, higher tions, the objective of this review was not to pro- 9. Byrne JV, Boardman P, Ioannidis I, Adcock J, Traill

phenytoin burden was associated with poor vide level 1 evidence for the purposes of guiding Z: Seizures after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemor-

functionaloutcomeat14days,andworsecogni- clinical practice, but to illustrate the usefulness rhage treated with coil embolization. Neurosurgery

tive score at 3 months (33). and limitations of AEDs as the evidence sup- 52:545-552, 2003.

The potential for newer antiepileptic drugs ports them in the modern literature. 10. Choi KS, Chun HJ, Yi HJ, Ko Y, Kim YS, Kim JM:

with reduced morbidity requires further investi- Seizures and epilepsy following aneurysmal sub-

gation. In 176 patients with aSAH initially arachnoid hemorrhage: Incidence and risk factors.

treated with phenytoin, 40% required replace- CONCLUSIONS J Korean Neurosurg Soc 46:93-98, 2009.

ment with levetiracetam due to adverse events, Among patients with aSAH, the incidence of 11. Choudhari KA: Seizures after aneurysmal subarach-

all of which resolved upon switching except early and late postoperative seizures is 2.3% and noid hemorrhage treated with coil embolization.

mental status and gastrointestinal disturbance 5.5%,respectively.Theincidenceoflateseizures Neurosurgery 54:1029-1030, 2004.

(50). In a recent prospective, randomized com- among patients treated with endovascular coil

12. Chumnanvej S, Dunn IF, Kim DH: Three-day pheny-

parative trial in patients with traumatic brain in- embolization seems to be lower than that toin prophylaxis is adequate after subarachnoid

dustry or SAH, levetiracetam was associated among patients treated with surgical clipping hemorrhage. Neurosurgery 60:99-103, 2007.

with better long-term outcomes and lower fre- (3.3% vs. 6.5%). Seizures after aneurysm oblit-

quency of worsened neurological status and eration may occur at a considerable time after 13. Claassen J, Peery S, Kreiter MA, Hirsch LJ, Du EY,

Connolly ES, Mayer SA: Predictors and clinical im-

gastrointestinal upset than phenytoin (52). initialhospitalizationandmanifestasavarietyof pact of epilepsy after subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Levetiracetam has been shown to be neuropro- seizuretypes.Nevertheless,thereseemstobeno Neurology 60:208-214, 2003.

tectiveinamousemodelofSAH(55),incontrast benefit to the administration of prophylactic

to phenytoin which was not associated with im- AEDs among aSAH patients. The routine use of 14. Deutschman CS, Haines SJ: Anticonvulsant prophylaxis

in neurological surgery. Neurosurgery 17:510-517, 1985.

proved functional or histological outcomes. these drugs in patients with aneurysmal SAH

The argument from proponents of AED pro- therefore cannot be supported by the available 15. Diringer MN: Management of aneurysmal subarach-

phylaxis is that it may be reasonable for patients evidence. noid hemorrhage. Crit Care Med 37:432-440, 2009.

WORLD NEUROSURGERY 79 [5/6]: 682-690, MAY/JUNE 2013 www.WORLDNEUROSURGERY.org 689

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Black Death, The Great Mortality of 1348-1350: A Brief History With DocumentsDokumen286 halamanThe Black Death, The Great Mortality of 1348-1350: A Brief History With DocumentsVaena Vulia100% (7)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Agarwal - Manual of Neuro OphthalmogyDokumen272 halamanAgarwal - Manual of Neuro Ophthalmogythycoon100% (4)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Advanced Handbook of Systemic Lupus ErythematosusDokumen179 halamanAdvanced Handbook of Systemic Lupus ErythematosusCésar CuadraBelum ada peringkat

- Cellular Aberration Acute Biologic Crisis 100 Items - EditedDokumen8 halamanCellular Aberration Acute Biologic Crisis 100 Items - EditedSherlyn PedidaBelum ada peringkat

- 22 Recent Advances in Pancreatic Cancer Surgery of Relevance To The Practicing PathologistDokumen7 halaman22 Recent Advances in Pancreatic Cancer Surgery of Relevance To The Practicing PathologistJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- Ectopia Lentis: Images in Clinical MedicineDokumen1 halamanEctopia Lentis: Images in Clinical MedicineJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- Shoulder-Pad Sign of Amyloidosis: Structure of An Ig Kappa III ProteinDokumen5 halamanShoulder-Pad Sign of Amyloidosis: Structure of An Ig Kappa III ProteinJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- Nej Mic M 1703542Dokumen1 halamanNej Mic M 1703542anggiBelum ada peringkat

- Practical Teaching Cases: A New Section For Trainees and Young GIsDokumen1 halamanPractical Teaching Cases: A New Section For Trainees and Young GIsJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- Cytoreductive Surgery and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy For The Treatment of Advanced Epithelial and Recurrent Ovarian Carcinoma A Single Center ExperienceDokumen7 halamanCytoreductive Surgery and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy For The Treatment of Advanced Epithelial and Recurrent Ovarian Carcinoma A Single Center ExperienceJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- 34 Intentional Injuries and Patient Survival of Burns A 10-Year Retrospective Cohort in Southern BrazilDokumen8 halaman34 Intentional Injuries and Patient Survival of Burns A 10-Year Retrospective Cohort in Southern BrazilJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- Amphetamine Years Diss.Dokumen397 halamanAmphetamine Years Diss.LeeKayeBelum ada peringkat

- 13 Laparoscopic Management For Acute Malignant Colonic ObstructionDokumen5 halaman13 Laparoscopic Management For Acute Malignant Colonic ObstructionJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- 17.1 Colonic Stenting Versus Emergency Surgery For Acute Left-Sided Malignant Colonic Obstruction A Multicentre Randomised TrialDokumen9 halaman17.1 Colonic Stenting Versus Emergency Surgery For Acute Left-Sided Malignant Colonic Obstruction A Multicentre Randomised TrialJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- Shoulder Pad Sign and Asymptomatic HypercalcemiaDokumen5 halamanShoulder Pad Sign and Asymptomatic HypercalcemiaJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- 33 Emergency Colorectal Resections in Asian Octogenarians Factors Impacting Surgical OutcomeDokumen5 halaman33 Emergency Colorectal Resections in Asian Octogenarians Factors Impacting Surgical OutcomeJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- 50 Postoperative Mortality and Morbidity in Older Patients Undergoing Emergency Right Hemicolectomy For Colon CancerDokumen6 halaman50 Postoperative Mortality and Morbidity in Older Patients Undergoing Emergency Right Hemicolectomy For Colon CancerJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- 42 Trends in Demographics and Management of Obstructing Colorectal CancerDokumen5 halaman42 Trends in Demographics and Management of Obstructing Colorectal CancerJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- 20 Differences Between Proximal and Distal Obstructing Colonic Cancer After Curative SurgeryDokumen7 halaman20 Differences Between Proximal and Distal Obstructing Colonic Cancer After Curative SurgeryJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- 18 Surgical Practices For Malignant Left Colonic Obstruction in GermanyDokumen7 halaman18 Surgical Practices For Malignant Left Colonic Obstruction in GermanyJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- 37 Colonic Stent Placement As A Bridge To Surgery in Patients With Left-Sided Malignant Large Bowel Obstruction. An Observational StudyDokumen7 halaman37 Colonic Stent Placement As A Bridge To Surgery in Patients With Left-Sided Malignant Large Bowel Obstruction. An Observational StudyJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- 17 Oncological Outcome of Malignant Colonic Obstruction in The Dutch Stent-In 2 TrialDokumen7 halaman17 Oncological Outcome of Malignant Colonic Obstruction in The Dutch Stent-In 2 TrialJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- 17 Oncological Outcome of Malignant Colonic Obstruction in The Dutch Stent-In 2 TrialDokumen7 halaman17 Oncological Outcome of Malignant Colonic Obstruction in The Dutch Stent-In 2 TrialJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- 44 Emergency First Presentation of Colorectal Cancer Predicts Significantly Poorer Outcomes A Review of 356 Consecutive Irish PatientsDokumen7 halaman44 Emergency First Presentation of Colorectal Cancer Predicts Significantly Poorer Outcomes A Review of 356 Consecutive Irish PatientsJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- 2 PDFDokumen7 halaman2 PDFTaufik Gumilar WahyudinBelum ada peringkat

- 10 Long-Term Outcome of Stenting As A Bridge To Surgery For Acute Left-Sided Malignant Colonic ObstructionDokumen6 halaman10 Long-Term Outcome of Stenting As A Bridge To Surgery For Acute Left-Sided Malignant Colonic ObstructionJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- 34 Self-Expandable Metal Stents For Relieving Malignant Colorectal Obstruction Short-Term Safety and Efficacy Within 30 Days of Stent Procedure in 447 PatientsDokumen9 halaman34 Self-Expandable Metal Stents For Relieving Malignant Colorectal Obstruction Short-Term Safety and Efficacy Within 30 Days of Stent Procedure in 447 PatientsJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- 26 Short-Term Outcomes Following The Use of Self-Expanding Metallic Stents in Acute Malignant Colonic Obstruction e A Single Centre ExperienceDokumen5 halaman26 Short-Term Outcomes Following The Use of Self-Expanding Metallic Stents in Acute Malignant Colonic Obstruction e A Single Centre ExperienceJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- 2emergency Neurological Life Support Subarachnoid HemorrhageDokumen6 halaman2emergency Neurological Life Support Subarachnoid HemorrhageJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- Current Practice Regarding Seizure Prophylaxis in Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Across Academic CentersDokumen3 halamanCurrent Practice Regarding Seizure Prophylaxis in Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Across Academic CentersJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- A Meta Analysis of Treating Subarachnoid Hemorrhage With Magnesium Sulfate.Dokumen3 halamanA Meta Analysis of Treating Subarachnoid Hemorrhage With Magnesium Sulfate.Joao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- A Randomized Trial of Brief Versus Extended Seizure Prophylaxis After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid HemorrhageDokumen6 halamanA Randomized Trial of Brief Versus Extended Seizure Prophylaxis After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid HemorrhageJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- Seizures and Epileptiform Patterns in SAH and Their Relation To OutcomesDokumen11 halamanSeizures and Epileptiform Patterns in SAH and Their Relation To OutcomesJoao FonsecaBelum ada peringkat

- Pumpkin TakoshiDokumen22 halamanPumpkin TakoshiSudhanshu NoddyBelum ada peringkat

- VLCC Case StudyDokumen3 halamanVLCC Case StudyAlok Mittal0% (1)

- Fertilization Reflection PaperDokumen2 halamanFertilization Reflection PaperCrisandro Allen Lazo100% (2)

- PowersDokumen14 halamanPowersIvan SokolovBelum ada peringkat

- Prioritization - FNCPDokumen10 halamanPrioritization - FNCPJeffer Dancel67% (3)

- Nursing Care Plan For Ineffective Cerebral Tissue PerfusionDokumen2 halamanNursing Care Plan For Ineffective Cerebral Tissue PerfusionKate CruzBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 1Dokumen63 halamanChapter 1Ashenafi TakelBelum ada peringkat

- Msds ChloroformDokumen9 halamanMsds ChloroformAhmad ArisandiBelum ada peringkat

- Blood Can Be Very BadDokumen37 halamanBlood Can Be Very BadPhil SingerBelum ada peringkat

- Cast and SplintsDokumen58 halamanCast and SplintsSulabh Shrestha100% (2)

- Aac-Augmentative and Alternative CommunicationDokumen35 halamanAac-Augmentative and Alternative Communicationrenuka aurangabadkerBelum ada peringkat

- International Rice Research Notes Vol.18 No.1Dokumen69 halamanInternational Rice Research Notes Vol.18 No.1ccquintosBelum ada peringkat

- GENERAL RISK ASSESSMENT Mechatronics LaboratoryDokumen2 halamanGENERAL RISK ASSESSMENT Mechatronics LaboratoryJason TravisBelum ada peringkat

- Resource Material - Day 1 Primary Register Activity - ANC Register - 0Dokumen3 halamanResource Material - Day 1 Primary Register Activity - ANC Register - 0Ranjeet Singh KatariaBelum ada peringkat

- The Effects of The Concept of Minimalism On Today S Architecture Expectations After Covid 19 PandemicDokumen19 halamanThe Effects of The Concept of Minimalism On Today S Architecture Expectations After Covid 19 PandemicYena ParkBelum ada peringkat

- Bedwetting in ChildrenDokumen41 halamanBedwetting in ChildrenAnkit ManglaBelum ada peringkat

- Program Implementation With The Health Team: Packages of Essential Services For Primary HealthcareDokumen1 halamanProgram Implementation With The Health Team: Packages of Essential Services For Primary Healthcare2A - Nicole Marrie HonradoBelum ada peringkat

- COPD CurrentDokumen9 halamanCOPD Currentmartha kurniaBelum ada peringkat

- Chemo Stability Chart AtoK 1jun2016Dokumen46 halamanChemo Stability Chart AtoK 1jun2016arfitaaaaBelum ada peringkat

- AUB - Microscopic Analysis of UrineDokumen4 halamanAUB - Microscopic Analysis of UrineJeanne Rodiño100% (1)

- Adr Enaline (Epinephrine) 1mg/ml (1:1000) : Paediatric Cardiac Arrest AlgorhytmDokumen13 halamanAdr Enaline (Epinephrine) 1mg/ml (1:1000) : Paediatric Cardiac Arrest AlgorhytmwawaBelum ada peringkat

- Calcium Hydroxide, Root ResorptionDokumen9 halamanCalcium Hydroxide, Root ResorptionLize Barnardo100% (1)

- Physiology of The Cell: H. Khorrami PH.DDokumen89 halamanPhysiology of The Cell: H. Khorrami PH.Dkhorrami4Belum ada peringkat

- Sample ReportDokumen3 halamanSample ReportRobeants Charles PierreBelum ada peringkat

- 3yc CrVlEemddAqBQMk Og 1.4 Six Artifacts From The Future of Food IFTF Coursera 2019Dokumen13 halaman3yc CrVlEemddAqBQMk Og 1.4 Six Artifacts From The Future of Food IFTF Coursera 2019Omar YussryBelum ada peringkat

- Punjab Municipal Corporation Act, 1976 PDFDokumen180 halamanPunjab Municipal Corporation Act, 1976 PDFSci UpscBelum ada peringkat